Abstract

Background

It has been hypothesized that placebo periods may increase long-term morbidity for patients with schizophrenia. In this study, the long-term effect of a placebo period was evaluated in a group of relatively treatment-refractory patients with chronic schizophrenia.

Methods

This retrospective study examined behavioral rating scores for 127 patients with chronic schizophrenia who were placed in a double-blind placebo study on the inpatient units of the National Institute of Mental Health Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital. Patients were rated daily with the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale (PSAS), an extended and anchored version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). At the end of the placebo phase, most patients were placed on haloperidol. Pre-placebo baseline PSAS ratings were compared with, first, discharge ratings and second, post-placebo ratings. To determine expected variability in the course of illness, patients in the placebo group were compared with patients hospitalized during the same time period, but who did not enter the placebo study.

Results

By discharge, ratings for placebo patients had returned to baseline. Post-placebo ratings were quite variable. Although many of the placebo patients had returned to baseline by day 3 of the post-placebo phase, others had not returned to baseline by post-placebo day 42. PSAS Total Scores for patients who left the study early were no different at baseline, placebo, or through post-placebo day 35 compared with patients who completed the study.

Conclusions

The results indicate that given a sufficiently lengthy recovery period, patients with chronic schizophrenia who go through a placebo phase return to baseline, but that the speed with which they attain that recovery is highly variable.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, placebo, antipsychotic medications

Introduction

In the last few years, increasing evidence has accrued that patients with schizophrenia treated early in their illness with antipsychotic medications may have a better long-term course than those for whom treatment is delayed (Power et al 1998; Wyatt 1995, 1991). With a population of more chronic patients, however, it is unclear whether the discontinuation of medications and the usual subsequent relapse cause greater long-term morbidity. Evidence exists that some patients become increasingly difficult to treat following successive relapses (Johnson et al 1983; Szymanski et al 1995), and that such relapses often occur after antipsychotic medications have been discontinued. Furthermore, although not necessarily associated with the discontinuation of antipsychotic medications, several longitudinal studies of patients with schizophrenia have noted that there is a step-like loss of function following each relapse (Bleuler 1978; Ciompi 1980; Harrow et al 1997; Kraepelin 1971; Watt et al 1983). Both the finding that early treatment and the less substantiated view that sustained treatment with antipsychotic medications improves the long-term course of schizophrenia are subject to a variety of interpretations (DeLisi et al 1997; Wyatt and Henter 1998).

Understanding these issues not only has implications for patient care, but also for the research community, where medication-free trials have long been considered important (Carpenter 1997; Carpenter et al 1997; Wyatt 1997). A number of ethical concerns are raised by such research, including the patient’s capacity to give informed consent to such studies, the length of time patients should be monitored after a medication-free phase to ensure their safe return to baseline, and how to best provide care for patients who decide to leave such medication-free periods early. The long-term risks of medication discontinuation for research purposes in patients with chronic schizophrenia are largely unknown; however, many studies suggest that progression of the illness and development of residual and deficit states occurs early, often precedes psychosis, and typically does not progress after the initial five years (Angst 1988; Bleuler 1978; McGlashan 1988).

For many years at what was formerly the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital, patients with schizophrenia were studied during medication-free periods. The program was not a randomized control trial; all patients who had a medication-free period knew that they would have one, but they were blind to the timing of the placebo portion of their inpatient stay. It was felt that examining patients at times when they were not taking antipsychotic medications would clarify whether putative research findings were related to the state of a patient—including the direct effects of medication—or were intrinsic to the illness.

The individuals studied were almost invariably patients who had responded to conventional treatments, but poorly; participation in the program meant a thorough assessment of their illness as well as the opportunity to receive new and appropriate medications in a carefully monitored inpatient setting. Furthermore, most of the patients had at some previous time themselves discontinued antipsychotic medications, and discontinuing them again in a controlled environment therefore seemed to hold little risk. Throughout most of the time this research was being conducted, the prevailing view held by the psychiatric community was that patients would accrue no long-term adversities from such medication-free periods; because patients with treatment-refractory chronic schizophrenia could not be expected to deteriorate indefinitely, by the time they entered a medication-free protocol such as the one described here, no further long-term effects were considered likely. In addition, because they could be closely monitored and treatment could be restored whenever deemed appropriate, immediate risks were felt to be reasonable and manageable.

One hundred and twenty seven patients at the NIMH Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital were placed on placebo for varying periods of time. The nature of the research program also made it possible to compare the outcome of patients placed on placebo with a reference group of similar patients who were admitted contemporaneously but who were not placed on placebo.

The present study attempts to answer three major questions related to the safety of placebo periods:

Do placebo periods have long-term effects on the course of illness in patients with chronic schizophrenia?

How long does it take patients with schizophrenia to recover after antipsychotic medications have been restored?

How is the course of illness affected for patients who choose to leave organized medication-free periods early, before they have had a chance to restabilize on antipsychotic medications?

Methods and Materials

All patient volunteers (hereafter referred to as patients) who had been admitted to the NIMH Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital at Saint Elizabeths Hospital in the 12-year period from April 1982 to April 1994 with a probable diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were candidates for this retrospective study. The patients were almost always referred because they were relatively refractory to conventional treatments, meaning that they required frequent or lengthy hospitalizations, and were usually unable to live independently. Patients were not admitted because of an acute exacerbation of their illness, but rather because they wished to participate in the research program. Prior to admission, patients were told that their agreement to join the research project meant they would be asked to participate in a medication-free phase—conducted for both evaluation and research purposes—lasting at least 6 weeks. All patients, and usually a family member, signed an informed consent form that had been approved by the NIMH Institutional Review Board (IRB). Only patients who were judged capable of giving their own informed consent to research participation entered the program. A patient’s capacity was determined by the patient’s referring physician and the Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital psychiatrists, applying standard clinical methods.

Diagnosis was established after a 1- to 2-month evaluation period by a senior psychiatrist and a psychiatric social worker, using DSM-III and DSM-III-R criteria (American Psychiatric Association 1980; American Psychiatric Association 1987). Diagnosis was again reviewed prior to discharge, in part based on data collected during the medication-free phase.

Phases of Hospitalization and Selection of Patients

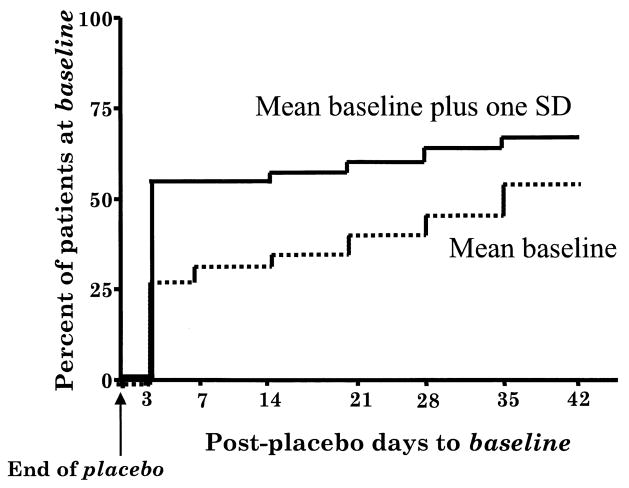

As Figure 1 illustrates, the hospital stay for patients who underwent a medication-free period was separated into the evaluation, baseline, placebo, post-placebo, and discharge phases. During the evaluation phase, which comprised the first few weeks of the hospitalization, patients’ medical and psychiatric problems were assessed, and, if necessary, their symptoms were stabilized. During this time, medications thought to be unnecessary (for example, if patients were receiving several antipsychotic medications at once) were discontinued. At the close of the evaluation phase, a final judgement was made as to the advisability of a placebo phase, based on conversations with the patient, his or her family, and the staff about the potential risks to the patient and others.

Figure 1.

Phases for placebo patients.

During the baseline phase, patients scheduled to have a placebo phase were placed on a standardized coded medication, at a dose deemed optimal based on their past history and current medication dose (with few exceptions, this medication was liquid haloperidol given in orange juice). This medication was identical in appearance to the placebo medication they would receive during the placebo phase. The coded medication was also identical to the medication they would receive during the post-placebo phase. For most patients, the baseline phase lasted about 4 weeks. At the end of the baseline phase, patients were switched in a double-blind fashion to placebo and entered the placebo phase. For about half the patients, the baseline phase was extended another 6 weeks on a randomly assigned basis in order to prevent the sequence from being predictable. During the placebo phase, as during the entirety of their hospitalization, hospital staff were in contact with patients’ families. Patients remained in the placebo phase for 6 or more weeks if their condition, as determined by the medical staff, did not seriously deteriorate, and if they, their families, or often a pastoral counselor who spent considerable time on the ward, did not express concern about their condition.

The post-placebo phase lasted for 6 weeks after medications were restored, although 14 of the 127 patients left the hospital before the end of that time. All patients, however, were receiving antipsychotic medications when they left the hospital (see Analysis 3). Ratings were analyzed from days 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 of the post-placebo phase. When patients seemed to be responding poorly to the active medication they received during this time, it was usually changed after the post-placebo phase.

Finally, with few exceptions, ratings for the discharge phase comprise weeks 2 and 3 before a patient left the hospital. It was felt that these 2 weeks would probably best reflect the patient’s final level of functioning, because impending discharge might have been unusually stressful for patients during their last week in the hospital. Also, ratings were more difficult to obtain in the final week before a patient’s departure.

One hundred twenty-six of the 127 patients in the placebo group were diagnosed with schizophrenia, and one was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder. The actual number of patients available for each analysis varied and is described in the “Results” section.

In order to assess whether any changes found in the placebo group’s ratings were related to some aspect of hospitalization, such as the way patients were rated over time, we also studied baseline and discharge ratings for a group of patients hospitalized at the NIMH Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital during the same time period, but who were not placed on placebo (the reference group). Of all patients admitted to the NIMH Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder between 1982 and 1994, about 35 percent were not placed on placebo, and were thus potential reference subjects. Possible reasons for exclusion were assessed during the evaluation phase, and included the presence of unrecognized medical problems, a previous history of significant violence to themselves and to others when medication-free that had not been recognized at admission, the withdrawal of patient or family consent, or the recognition that a patient was too ill to participate. In addition, patients admitted to participate in different research protocols specifically for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia were included in this group; these protocols did not involve a medication-free period. This does not mean that patients with tardive dyskinesia were excluded from the placebo group. Indeed, Table 1 shows that roughly the same proportion of patients (over half) in both the placebo and reference groups suffered from tardive dyskinesia. To increase the comparability between the placebo and reference groups, only patients who were hospitalized for 134 or more days were included in the reference group. One hundred thirty-four days was chosen because no patient who had a medication-free period and completed the post-placebo phase was hospitalized for less time. Thirty-two patients (30 with schizophrenia and two with schizo-affective disorder) met these criteria and comprise this reference group.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Variables for 65 Placebo Patients and 27 Patients in the Reference Group Discharged on Typical Antipsychotic Medications (Analysis 1)

| Placebo group (n = 65) | Reference group (n = 27) | t/Z | p≤ | Mean difference | 95% CI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Age (years) at admission (SD) | 31.2 (7.94) | 30.8 (7.68) | −0.20 | 0.84 | −0.4 | −3.94 | 3.21 |

| Duration (years) of illness (SD) | 11.5 (7.87) | 12.5 (8.05) | 0.59 | 0.56 | 1.1 | −2.54 | 4.67 |

| Years of education (SD) | 12.9 (2.04) | 12.7 (1.94) | −0.51 | 0.61 | −0.2 | −1.15 | 0.68 |

| Gender (F/M) | 23/42 | 10/17 | 0.99b | ||||

| Diagnosis (schizophrenia/schizoaffective) | 64/1 | 25/2 | |||||

| Race (white/nonwhite) | 54/11 | 22/5 | 0.99b | ||||

| Married (yes/no) | 8/57 | 5/22 | 0.51b | ||||

| Tardive dyskinesia (yes/no) | 24/41 | 11/16 | 0.81b | ||||

| Smoker (yes/no) | 43/22 | 21/6 | 0.33b | ||||

| Verbal IQ (SD) | 91.3 (15.2) | 86.1 (13.4) | −1.41 | 0.16 | −5.2 | −12.4 | 2.12 |

| Performance IQ (SD) | 85.0 (10.4) | 80.3 (12.0) | −1.77 | 0.08 | −4.8 | −10.1 | 0.58 |

| Full scale IQ (SD) | 87.3 (12.5) | 82.9 (12.3) | −1.48 | 0.14 | −4.5 | −10.5 | 1.54 |

| CPZ equivalents | |||||||

| Baseline (SD) | 1219 (1,304) | 6417 (16,223) | 2.77a | 0.006 | |||

| Discharge (SD) | 1568 (1,922) | 2373 (2,583) | 1.96a | 0.051 | |||

| Days admission to discharge | 487 (243) | 321 (208) | −3.10 | 0.003 | −166 | −272 | −59.8 |

Mann–Whitney Z.

F = Fisher’s Exact.

CI, confidence interval.

Rating Scale

While hospitalized, patients were rated twice a day—on the day and evening shifts—by two nurse raters. Because there was generally more opportunity to rate patients on the day rather than the evening shift, mean ratings for the day shift were used unless they were unavailable, in which case mean evening shift ratings were substituted. The rating instrument used was the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale (PSAS) (Bigelow and Berthot 1989), which was developed at the NIMH Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital and is an extended version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall and Gorham 1962). The PSAS is a 7-point (0–6) rating scale, with zero indicating the symptom or behavior was not present; thus, lower scores indicate better functioning. The PSAS has 22 individual sign and symptom questions that, when summed, yield a Total Score having a possible range of 0 to 132. Total Score was used in these analyses. When the PSAS was developed, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; Bartko and Carpenter 1976) for our nursing staff was 0.927 (Bigelow and Berthot 1989). Because training remained the same from the time the PSAS was developed throughout the study, it is likely that the reliability remained close to this value over the 12-year period.

Timing of Ratings

The ratings used were timed to provide the best estimate of behavior during each phase. Because the behavior and symptoms of the patients were constantly changing due to the conditions of the study, long rating periods would not represent the phase of interest. For those patients who had a medication-free period, the baseline was the mean of ratings from days 7, 6, and 5 before the patients entered the placebo phase. The ratings from the last 4 days of that week were not used, because this was a time when active medications were being tapered. If a patient was taking an anticholinergic agent in addition to the antipsychotic medication, the anticholinergic medication was tapered (also to placebo) at a much slower rate than the antipsychotic medication—usually for a week into the placebo phase.

For the reference group, the baseline phase rating was the mean of 7 days beginning 28 days after they were admitted to the hospital. Following the first 35 days of hospitalization, many of these patients went into active medication protocols; ratings obtained during that time would thus be less representative of patients’ baseline.

For the placebo group, ratings during the placebo phase comprised the mean of the last week the patients were on placebo. No patients received placebo for less than seven days, although, in one case, the placebo rating comprised the entirety of that patient’s placebo phase. Post-placebo phase ratings were obtained for days 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 after medications were restored.

Discharge phase ratings for both placebo and reference groups were the mean ratings from weeks 2 and 3 before the patients left the hospital. Five patients who otherwise met the above criteria had no ratings within weeks to months of their date of discharge and are therefore not included in this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The most frequently conducted analysis used the discharge minus baseline change in PSAS Total Score, subsequently referred to as delta.

Nonparametric analyses were used for categorical variables and when variances were unequal. For continuous variables, t tests and repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used. Continuous data are expressed as means and SDs, and comparisons are presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). When significant, the repeated measures ANOVAs were followed with Bonferroni t post hoc tests (Bailey 1977) and t tests. Survival analyses were carried out in Analysis 2 using the Kaplan–Meier method. As described in Analysis 2, two separate sets of criteria were used to define sustained recovery. All tests were two tailed and α was <0.05. Analyses were conducted using StatView for Windows (Version 5.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC), NCSS 2000 (NCSS Statistical Software, Kaysville, UT), and BMDP 1990 (BMDP Statistical Software, Inc., Los Angeles, CA).

Results

Analysis 1. Do Placebo Periods Have Long-Term Effects on the Course of Illness in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia? Part A: Placebo Patients at Baseline and at Discharge

PLACEBO PATIENTS

Of the 127 patients who had at least one placebo phase, discharge ratings were available for 107. A subgroup of 28 patients went through two placebo phases, and data were available for 26 of them. Because experiencing two placebo phases might have affected these patients differently, they were examined independently. It was found that by discharge, scores for patients who went through two placebo phases were very similar to their rating at baseline (25.9 vs. 23.3) (mean difference = −2.60; 95% CI = −10.11, 4.91; paired t(25) = −0.71; p = .48).

At discharge, an additional 14 of these 107 patients were receiving clozapine. Because clozapine has previously been found to be a more effective antipsychotic medication in patients with chronic schizophrenia (Kane et al 1988), ratings for these patients were also analyzed separately. It was found that placebo patients discharged on clozapine did not differ from the placebo patients taking typical antipsychotic medications at discharge on any demographic variables (data not shown), including their baseline Total Score. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference in delta for those patients taking clozapine at discharge (mean difference = 5.65; 95% CI = − 1.80, 13.10; paired t[13] = 1.64; p = .12).

PLACEBO PATIENTS DISCHARGED ON TYPICAL AN-TIPSYCHOTIC MEDICATIONS

Of the 107 initial patients in Analysis 1, 65 had undergone one placebo phase and been discharged on typical antipsychotic medications. The placebo phase lasted a mean of 62.0 days (SD = 44.5; median = 48; range =7–237), and the mean time from resuming antipsychotic medications to discharge for the placebo group was 338.2 (SD = 231.8) days (median = 289 days, range = 65–1197 days). When delta was analyzed, no statistically significant change in ratings was found. For the 65 placebo patients, Total Scores were 22.0 (SD = 11.3) at baseline, and 22.8 (SD = 12.8) at discharge (mean difference = −0.74; 95% CI = −3.81, 2.33; paired t[64] = 0.48; p = .63).

Analysis 1, Part B: Determining Expected Variability in Ratings at Discharge

PLACEBO VERSUS REFERENCE PATIENTS

Results from a reference group were analyzed to assess whether there were factors specific to the hospitalization rather than to being medication-free that affected the placebo patients’ ratings. No difference in demographic variables was found between these 65 placebo patients and the 27 patients in the reference group also discharged on typical antipsychotic medications (five patients in the reference group were discharged on clozapine) (see Table 1). At baseline, however, the patients in the reference group were taking significantly more antipsychotic medications in chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalents (Jeste and Wyatt 1982) than those patients who had a placebo phase; there was no difference in the amount of CPZ equivalents the groups were receiving at discharge. The decrease in CPZ equivalents at discharge was due to ward psychiatrists reducing what were often exceptionally high admission doses. The total time placebo patients were in the hospital was significantly longer (487 days [SD = 243]) than the time patients in the reference group spent there (320 days [SD = 208]; mean difference = 166 days; 95% CI = 272, 59.8; t[90] = 3.10; p = .003).

Patients in the reference group also had significantly higher (mean difference = 9.30; 95% CI = 3.90, 14.70; t(90) = 3.42; p = .0009) baseline ratings (31.3 [SD = 13.2]), as well as significantly higher (mean difference = 7.54; 95% CI = 1.63, 13.44; t(90) = 2.53; p = .01) discharge ratings (30.3 [SD = 13.4]) than the placebo patients. When delta was analyzed for the patients in the reference group, however, their scores were also found not to have changed significantly over the course of their hospitalization (mean difference = 1.02; 95% CI = − 4.25, 6.30; paired t(26) = 0.40; p = .69).

Finally, when delta was compared between the two groups, no significant difference was found (mean difference = −1.76; 95%CI = −7.53, 4.00; t(90) = 0.61; p = .54).

DETERMINING WHETHER ANY FACTORS PRE-DICTED A POOR RESPONSE, AND WHETHER SOME PLA-CEBO PATIENTS DID NOT RETURN TO BASELINE BY DISCHARGE

Although mean ratings did not differ between baseline and discharge for the placebo group, it seemed possible that individual patients might have responded particularly well to the care they were receiving in the research setting, whereas other patients might have fared more poorly. The results of these two subgroups might thus have cancelled each other out when observed as a group mean.

We examined this issue in two ways. First, we compared the 20% of the placebo patients who had the greatest change in Total Score at discharge from their baseline in either direction (the 13 patients doing comparatively the best, and the 13 patients doing comparatively the worst; see Table 2). No differences were found for any demographic variables between these two groups. This is consistent with, but by no means proves, that the apparent change at discharge was random.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Variables for the 20% of Placebo Patients Whose PSAS Total Score Had the Greatest Improvement or Decrement at Discharge When Compared with Baseline (Restricted to Patients with One Placebo Phase Who Were Taking Typical Antipsychotic Medications at Discharge (Analysis 1))

| Improved (n = 13) | Worsened (n = 13) | t | p≤ | Mean difference | 95% CI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Age (years) at admission (SD) | 30.1 (7.9) | 32.8 (9.4) | 0.83 | 0.50 | 2.81 | −9.84 | 4.22 |

| Duration (years) of illness (SD) | 11.9 (7.2) | 12.5 (10.1) | 0.17 | 0.87 | −0.58 | −7.70 | 6.53 |

| Years of education (SD) | 12.2 (2.4) | 12.8 (1.9) | 0.71 | 0.48 | 0.60 | −2.41 | 1.17 |

| Gender (F/M) | 5/8 | 4/9 | 0.99b | ||||

| Race (white/nonwhite) | 10/3 | 13/0 | 0.22b | ||||

| Married (yes/no) | 1/12 | 4/9 | 0.32b | ||||

| Tardive dyskinesia (yes/no) | 6/7 | 4/9 | 0.69b | ||||

| Smoker (yes/no) | 10/3 | 10/3 | 0.99b | ||||

| Verbal IQ (SD) | 90.0 (13.7) | 88.3 (16.0) | 0.27 | 0.79 | 1.66 | −10.97 | 14.30 |

| Performance IQ (SD) | 85.8 (11.3) | 83.3 (7.67) | 0.66 | 0.52 | 2.52 | −5.90 | 10.46 |

| Full scale IQ (SD) | 87.0 (11.6) | 84.6 (11.4) | 0.52 | 0.61 | 2.38 | −7.11 | 11.87 |

| CPZ equivalents | |||||||

| Baseline (SD) | 1998 (2571) | 1185 (662) | 0.59a | 0.55 | |||

| Discharge (SD) | 1425 (1223) | 1914 (2179) | 0.36a | 0.72 | |||

| Days on placebo | 64.3 (51.8) | 49.7 (33.7) | 0.85 | 0.40 | 14.61 | −20.8 | 50.0 |

| Days from end of placebo phase to discharge | 331 (178) | 252 (197) | 1.07 | 0.29 | 79.10 | −73.0 | 231 |

Mann Whitney Z

Fisher’s Exact.

CI, confidence interval.

To examine this further, we reasoned that the patients in the reference group—who were continuously treated with antipsychotic medications—would not be expected to be worse at discharge than at baseline. While in the hospital, their medication was being optimized in a way consistent with their behavior. Thus, if the patients in the placebo group who did not seem to return to baseline were comparatively worse at discharge than similar patients in the reference group, this might be attributable to their having been on placebo. To examine this, the 20% of patients with a single placebo phase, who were discharged on typical antipsychotic medications, and who had the highest delta (n = 13) (i.e., who were doing the worst at discharge) were compared with the 20% of patients in the reference group chosen using the same criteria (n = 5). The two groups of patients did not differ on any demographic variables, nor on delta (mean difference = 0.78; 95% CI = −12.6, 14.2; t(16) = 0.12; p = .90).

Analysis 2. How Long Does It Take Patients with Schizophrenia to Recover after Antipsychotic Medications Have Been Restored?

One hundred thirteen patients had at least one placebo phase, 106 of them had complete post-placebo ratings, and 103 are included in this analysis; three patients were excluded because they were placed on lithium and no antipsychotic medication during the post-placebo phase. When the patients treated with lithium during the post-placebo phase were included in the analysis, however, the outcome did not differ. A repeated (time) measures ANOVA (Table 3) for the 103 patients who had ratings for the baseline, placebo, and days 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 of the post-placebo phases was statistically significant (Greenhouse–Geisser df and ε are [6.30, 642.4] and 0.787, respectively; F = 12.41; p < .0001). Using Bonferroni t tests, all comparisons against baseline (the only comparison performed) were significant (critical difference = 4.48), except that for day 42. Table 3, however, also shows the results of paired t tests comparing all time periods with baseline. Using this statistically less conservative test, it was found that for the patients as a group, at no time during the 6-week post-placebo phase did the Total Score rating return to baseline (meaning that all post-placebo ratings remained statistically greater than baseline).

Table 3.

Baseline, Placebo and Post-Placebo PSAS Total Scores (Mean ± SD) for 103 Patients in Analysis 2

| Baseline | Placebo |

Post-placebo day

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 7 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 35 | 42 | |||

| Mean | 23.54 | 38.29a* | 32.42a* | 30.73a* | 31.22a* | 32.31b* | 27.96c* | 29.89b* | 27.71d |

| SD | 12.10 | 15.82 | 18.02 | 18.03 | 19.36 | 19.58 | 16.97 | 17.59 | 17.91 |

| Mean difference | 14.81 | 8.94 | 7.25 | 7.74 | 8.82 | 4.47 | 6.41 | 4.23 | |

| 95% CI | 12.67 11.79 | 12.67 5.21 | 10.61 3.88 | 11.17 4.31 | 12.28 5.37 | 7.84 1.11 | 9.76 3.06 | 7.66 0.81 | |

| Percent of patients returned to baseline plus 1SD | 53 | 53 | 56 | 59 | 63 | 66 | 66 | ||

Paired t tests compared with baseline

p ≤.0001,

p ≤.001,

p ≤.01,

p ≤.05.

Repeated measure ANOVA, (Greenhouse-Geisser), df and ε [6.30, 642.4] and 0.79, respectively; F = 12.41; p < .0001,

Bonferroni t p = .05, compared with baseline only.

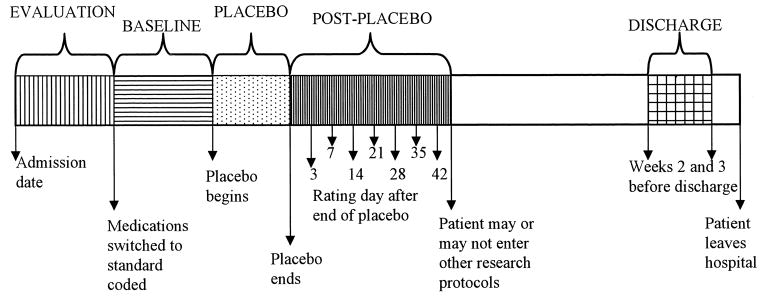

In order to assess how individual patients, rather than the group, responded, survival analyses were conducted (see Figure 2). The results indicated that, by post-placebo day 42, 50% of the patients had recovered to baseline, and 66% had recovered to their baseline mean plus one standard deviation. Recovery to baseline was defined as occurring any time the Total Score returned to baseline, and the mean of that day and all subsequent rating days did not go above baseline. Recovery to baseline plus one standard deviation above baseline was similarly defined. When ratings for post-placebo day 3 were analyzed, it was found that 25% of patients had returned to their mean baseline rating by day 3, and that 53% had returned to their baseline mean plus one standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the proportion of 103 patients returning to or below baseline, as well as those within baseline plus one standard deviation.

Analysis 3. How Is the Course of Illness Affected for Patients Who Choose to Leave Organized Medication-Free Periods Early?

Fourteen of the patients who had a placebo phase did not remain in the NIMH Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital for at least 42 days post-placebo. For a variety of personal reasons, some patients requested a discharge while still on placebo. At our request, however, all patients agreed to stay in the hospital for at least 3 days following the restoration of active medications (post-placebo day 3). Although post-placebo phase ratings are available for only 12 patients, the length of time these 14 patients spent in the hospital after medications were resumed ranged from 3 to 37 days (median = 22).

Table 4 shows that those 14 patients who did not complete the study had a significantly higher level of education than those who stayed in the hospital for at least 42 days post-placebo (mean difference = 1.32 years; 95% CI = 0.10, 2.56; t(115) = 2.15; p = .03). Also, the patients who did not complete the study had a shorter placebo phase (mean = 46.71 days; SD = 75.86; median = 24) than the patients who completed the post-placebo phase (mean = 61.48 days; SD = 45.71; median = 48) (Mann–Whitney Z = 3.11; p = .002). A comparison of Total Scores between the completers and noncompleters at baseline, placebo, and through post-placebo day 35 revealed no significant differences between the two groups (see Table 5).

Table 4.

Sociodemographic Variables for Patients Who Did and Did Not Complete at Least 42 Days of the Post-Placebo Phase (Analysis 3)

| Completers (n = 103) | Noncompleters (n = 14) | t/Z | P ≤ | Mean difference | 95% CI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Age (years) at admission (SD) | 31.6 (8.17) | 31.8 (4.95) | 0.10a | 0.92 | |||

| Duration (years) of illness (SD) | 11.8 (7.55) | 11.9 (5.11) | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.1 | −3.99 | 4.26 |

| Years of education (SD) | 12.7 (2.13) | 14.0 (2.42) | 2.15 | 0.03 | 1.3 | 0.10 | 2.55 |

| Gender (F/M) | 34/69 | 2/12 | 0.22b | ||||

| Race (white/nonwhite) | 83/20 | 10/4 | 0.48b | ||||

| Married (yes/no) | 15/88 | 1/13 | 0.69b | ||||

| Tardive dyskinesia (yes/no) | 37/66 | 3/11 | 0.38b | ||||

| Smoker (yes/no) | 67/36 | 8/6 | 0.57b | ||||

| Verbal IQ (SD) | 90.5 (14.2) | 96.3 (16.3) | 1.32 | 0.19 | 5.9 | −2.92 | 14.7 |

| Performance IQ (SD) | 84.0 (10.2) | 88.6 (9.2) | 1.46 | 0.15 | 4.5 | −1.62 | 10.7 |

| Full scale IQ (SD) | 86.6 (11.8) | 92.1 (12.9) | 1.51 | 0.13 | 5.5 | −1.72 | 12.8 |

| CPZ equivalents | |||||||

| Baseline (SD) | 1385 (1354) | 1219 (726) | 0.29a | 0.78 | |||

| Days on placebo | 61.5 (45.7) | 46.7 (75.9) | 3.11a | 0.0019 | |||

| Days post-placebo to discharge | 431.2 (356) | 19.8 (10.9) | 6.05a | 0.0001 | |||

Mann–Whitney Z.

Fisher’s Exact.

CI, confidence interval.

Table 5.

PSAS Total Scores (Mean ± SD) for 14 Patients Who Did Not Complete 42 Days of Post-Placebo Phase (Analysis 3). Comparison with 103 Patients Who Completed 42 Post-Placebo Days (Data in Table 3)

| Baseline | Placebo |

Post-placebo day

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 7 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 35 | |||

| n | 14 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Mean | 22.11 | 35.85a | 29.58 | 29.27b | 26.54 | 28.00 | 32.0 | 20.0 |

| SD | 13.00 | 14.92 | 13.13 | 11.85 | 13.49 | 18.07 | 8.49 | 14.14 |

| Mean Differencec | −1.43 | −2.45 | −2.84 | −1.46 | −4.68 | −4.30 | 4.04 | −9.89 |

| 95% CIc | −8.30 5.46 | −11.32 6.42 | −13.48 7.80 | −12.50 9.56 | −16.56 7.21 | −19.41 10.80 | −19.90 27.98 | −34.8 15.0 |

| t = c | 0.41 | −0.55 | −0.53 | −0.26 | −0.78 | −0.57 | 0.34 | −0.79 |

| p = c | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.74 | 0.43 |

Within subject comparison by paired t tests against baseline

p ≤.0005;

p ≤.005.

Between subject (completers [Table 3] vs. noncompleters [this table]) comparison with independent t tests.

Discussion

Many studies have looked at the discontinuation of anti-psychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia, but only a few have examined what changes occur beyond the immediate problems associated with exacerbation of the illness (Johnson et al 1983; Lieberman 1993). The major reason for conducting this retrospective analysis was to evaluate whether discontinuing antipsychotic medications in this group of chronic patients increased their long-term morbidity.

There are two principal findings from this study:

As measured by the PSAS, a group of relatively treatment-refractory patients with chronic schizophrenia who went through a medication-free period had no statistically significant changes in their behavioral ratings at discharge from baseline. As expected, individual patient response was variable, with some patients improving beyond baseline or staying the same, and others worsening. When we looked at issues of variance (Analysis 1, Part B), however, we found that, at discharge, there was the same degree of worsening for patients in the placebo and reference groups. Because patients in the reference group were treated continuously with antipsychotic medications and thus not expected to worsen, this finding suggests that the placebo patients’ ratings were affected by variability associated with the natural course of illness rather than by their participation in a medication-free trial.

The time it took for these patients to return to baseline was quite variable, but as a group required longer than 6 weeks after the restoration of medications.

Below, we discuss the salient findings from each of the three analyses, as well as some of the bioethical considerations and limitations associated with the study.

Analysis 1. Do Placebo Periods Have Long-Term Effects on the Course of Illness in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia?

Sixty-five patients had one placebo phase and were discharged on typical antipsychotic medications. Twenty-seven patients who had not undergone a placebo phase were also discharged on typical anti-psychotic medications. No statistically significant change between baseline and discharge ratings was found for either of the two groups.

The most direct method for determining the long-term consequences of medication discontinuation is to compare ratings of behavior before and at the greatest possible interval after a medication-free period, which, in our study, was just before discharge. For this group of 65 patients, discharge occurred about 340 days after the end of the placebo phase.

In the ideal study, patients would be randomly assigned to a placebo group or to a group continuously receiving antipsychotic medications in order to ensure that some form of bias did not affect the results. For several reasons, we believe it is unlikely bias could have entered this study. First, the staff performing the ratings was not being asked to compare the two groups. Other than the staff’s natural desire to see patients under their care improve, there was no particular reason for the raters to bias their rating towards one group, as they might do in a comparison study. Furthermore, at no time during the study did the patients, the staff, or the authors know that we would ultimately analyze these data in this way. In fact, if anything, our bias might have been to view the placebo patients as worse at discharge (Wyatt 1991, 1997; Wyatt and Henter 1998). Second, the discharge ratings were performed on average more than a year after the baseline ratings, and the raters did not have access to their past ratings; it is improbable that they would have remembered this information. Finally, patient admissions were staggered over 12 years, making it unlikely that a consistent bias would be maintained.

In spite of these protections, one could probably conceive of ways in which bias might have become an issue. For this reason, as well as to determine what variance in ratings might be expected over time, we introduced a reference group. In many, but not all ways, the patients in the reference group were similar to the patients in the placebo group. Thus, if the patients in the reference group had the same changes, or absence of changes in delta over the course of the hospitalization, it would suggest bias did not exist. Indeed, the variability in delta for the two groups was quite similar. Furthermore, those placebo patients who did appear worse at discharge were not worse than patients in the reference group at discharge.

Analysis 2. How Long Does It Take Patients with Schizophrenia to Recover after Antipsychotic Medications Have Been Restored?

As a group, the patients had not returned to baseline 6 weeks after medications were restored. Individually, however, 25% of the patients had recovered to baseline, and 53% had recovered to their baseline mean plus one standard deviation by day 3 after medications were restored. Similarly, 50% of the patients had recovered to baseline, and 66% had recovered to their baseline mean plus one standard deviation by day 42 of the post-placebo phase.

One important question for medication-free research is how soon after the restoration of medications patients with a chronic form of schizophrenia recover to their baseline. The post-placebo phase in this study lasted 6 weeks, which, for many patients, was too brief to fully evaluate this question; however, a longer evaluation period was not possible because after 6 weeks, some patients entered other research protocols. At least one study of first-episode patients with schizophrenia suggests that the time to remission from a first episode is 35.7 weeks (median, 11 weeks; Lieberman et al 1993). Using a variety of definitions of remission, other time periods have been observed (Garver et al 1988; May and Goldberg 1978). Our results suggest that, during the post-placebo phase, patient response to the restoration of antipsychotic medications was mixed with regard to time, an observation consistent with previous studies of chronic schizophrenic subjects (Glovinsky et al 1992; Keck et al 1989; May and Goldberg 1978; Nedopil and Ruther 1981; Sautter et al 1993; Stern et al 1993).

As would be expected, the patients’ elevated ratings during the placebo phase clearly show they became worse—for the group, the PSAS rating rose by 62%—during the placebo phase. Two statistical analyses were used to determine if and when patients as a group returned to baseline. The first analysis was a repeated measures ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni t tests comparing each post-placebo day rating with the baseline. The second analysis involved t tests, also comparing each post-placebo day rating with the baseline. A statistically significant p value on either of the two tests indicated that the patients’ Total Score did not return to baseline. At post-placebo day 42, the Bonferroni t test was not significant, indicating that there was no longer a statistically significant elevation above baseline; in contrast, the t test for the same day was significant, indicating that the Total Score remained statistically elevated.

It is important to note, however, that the results from Analysis 1 suggest that by discharge, this same group of patients had returned to baseline. This also held true for a subgroup of patients who, for a variety of reasons, had two placebo phases; as a group, these patients probably had not returned to baseline by post-placebo day 42 following either their first or second placebo phase (data not shown), but as a group, their ratings had returned to baseline by discharge. Furthermore, those patients who had two placebo phases showed no difference in the speed with which they returned toward baseline between the first and second post-placebo phases, suggesting that after so many years of being ill, further placebo phases did not increase long-term morbidity.

This finding clearly has implications for how medication-free research trials might be conducted in the future because it suggests that, although most of these patients will eventually return to baseline, a significant portion of them will take longer than six weeks to do so. Therefore it also implies that some patients will have to be followed more closely than others. Participants in this study were inpatients throughout the duration of the study, and our findings do not directly address the issue of how long inpatient care might be necessary.

Analysis 3. How Is the Course of Illness Affected for Patients Who Choose to Leave Organized Medication-Free Periods Early?

When PSAS scores were compared for patients who did and did not complete the study, no differences were found at baseline, placebo, or through post-placebo day 35, suggesting that these patients recovered at the same rate as those who remained in the hospital.

With all research projects involving medication-free periods, there is the risk that patients may refuse further participation, either while they are on placebo or after their antipsychotic medications are restored but before they have returned to baseline. Because periods of increased psychosis are likely to be the time when patients’ negativity and loss of insight are at a maximum, this issue is of concern. In this study, patients did withdraw from the study during the placebo and post-placebo phases. Fortunately, these patients allowed us to restart their antipsychotic medications; all patients received, at the very least, 3 days of antipsychotic medications prior to leaving the hospital. To the extent we were able to monitor these patients during their post-placebo phase, they appeared to improve at the same rate as the patients who completed the post-placebo phase, suggesting that many of them (between 25% and 53%) had returned to baseline functioning by day 3 after medications had been restored. There is no indication that these patients were unusually poorly responsive compared with the patients who completed the post-placebo phase.

BIOETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The risks associated with being medication free can be considerable, and include suicide (Palmer et al 1999), other forms of violence, and self-neglect. A number of ethical concerns are associated with medication-free periods. These include, but are not limited to, the patient’s capacity to give informed consent to such studies, the length of time patients should be monitored after a medication-free phase to ensure their safe return to baseline, and how to best provide care for patients who decide to leave such medication-free periods early.

All patients in this study signed an informed consent form that had been approved by the NIMH IRB, and were judged capable of giving their own consent by their referring physician and our staff. In retrospect, we would feel more comfortable if a validated method of judging capacity to give consent had been available and used. Formalized processes for assessing a subject’s capacity to give his or her own consent are now being widely discussed (Applebaum 1997; DeRenzo et al 1998; Grisso and Applebaum 1998; National Bioethics Advisory Commission 1998). Although it is important to ensure that patients entering such studies understand both the risks and potential benefits associated with their involvement, the imposition of overly restrictive criteria could further disenfranchise many patients from directly or indirectly receiving the potential benefits that might accompany research participation.

Analysis 2 suggests that it takes longer than 6 weeks for many patients with chronic schizophrenia to return to baseline following the restoration of antipsychotic medications. Thus, one issue requiring further consideration is how to better manage patients who decide to discontinue their study participation and refuse to resume their medications, but who have decreased decision-making abilities. A variety of novel mechanisms are currently being considered. One strategy adds an advance planning component to any protocol that includes a medication-free phase. This advance planning process could include any of a wide variety of well-established human subjects protection mechanisms such as, for instance, proxy consent (Applebaum 1996; Berg and Applebaum 1999; Fletcher and Wichman 1987; Flynn and Honberg 1998). Or, conversely, an arrangement similar to the one we had with patient families might be more formalized through the execution of a Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care.

Whichever approach is preferred and meets local legal standards, the issue of how to manage such situations is crucial because it provides a foundation of trust between patients, their families, and the researchers (Hall and Flynn 1999). During the course of this study, the staff were in contact with family members to answer questions, address concerns about the well-being of the patient, and provide some education about the disorder. The extent of the interaction between family and staff varied over the term of the study, and depended in part on the perceived needs of the family and their availability. It is possible, however, that a more consistent pattern of interaction (including the use of standardized educational materials for both the families and patients) would have been beneficial.

For those patients who left this study early, we were fortunately usually able to maintain a good relationship with the patients’ families, and often with the patients themselves once their insight improved. Because of our relationship with the families, we were able to follow these patients at a distance after they left our care, and know that their treatment was almost always continued by the referring physician; we have no evidence that there were any significant adverse events for these patients. We suspect, however, that our experience may not be typical of all research endeavors where patients undergo a medication-free phase, particularly when such research is done on an outpatient basis. Without a strongly established family relationship—both between the patient and his or her family and between the patient’s family and the researchers—it might be best not to consider a particular patient for participation in studies such as these (Larsen et al 1998). Or if the medical team’s relationship with a patient or that patient’s family member(s) sours during such studies, it might be prudent to consider placing the patient back on antipsychotic medications as quickly as possible.

Another important issue is the length of time patients enrolled in these studies should be monitored to ensure their safe return to baseline. The results of this study clearly indicate that chronic patients with schizophrenia may not have increased long-term morbidity due to a medication-free period, but they also show that more than 6 weeks are necessary for some patients to return to baseline. Patients in this study remained as inpatients for roughly 340 days after the end of the placebo phase, a time frame which is both unrealistic and unnecessary following most medication-free periods. But as the variable response of these patients highlights, the amount of time they are monitored may have to be decided on a case-by-case basis. In some cases, monitoring time may be shorter than previously anticipated; Analysis 2 showed that, even using the most conservative criteria, 25% of patients had returned to baseline by post-placebo day 3. It is not known whether more sensitive rating measures would have yielded the same conclusion.

The results of this study provide valuable information for those patients who are considering participating in a research study. But its findings would be negated if realistic and responsible safety measures, such as the ones highlighted here and elsewhere, were not in place.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Three types of limitations are associated with this study: those inherent in its design, those associated with the patient population, and those associated with the nature of schizophrenia. Some of these have been discussed previously.

Design Limitations

One important distinction between these patients and placebo patients in similar medication-free trials is that as a group, these patients remained on placebo for much longer (average length of placebo phase was 61.5 days). This distinction may be important for studies in which similar patients are deliberately taken off antipsychotic medications for research purposes. In those studies, we would expect the shorter placebo phase to cause the patients no greater long-term effects than were found in this study. Furthermore, patients with shorter placebo phases might return to baseline faster than some of the patients in our study; the present study was not designed to answer that question. For the patients in this study, there was no relationship between the length of time on placebo and the time it took patients to return to baseline, but that may be due to our having restored antipsychotic medications when patients’ behavior reached a subjective threshold, rather than keeping every patient on placebo for a set time.

Although this was not the case in our study, another difference is that, in large studies where a new antipsychotic medication is being compared with a standard antipsychotic medication, patients often become involved in the study because they are having an exacerbation of their symptoms, and one reason for an exacerbation may be that patients have discontinued their antipsychotic medications. Patients who discontinue their antipsychotic medications on their own rarely do so in a controlled, protective hospital setting such as the one in this study; and by the time such patients’ symptoms become severe, the patients may no longer have the insight needed to restart their medications. In such situations, the amount of stress these patients undergo is likely to exceed that experienced by our patients. For this reason, generalizations from the current study to patients whose medications are stopped in nonclinical settings may not be warranted.

Another aspect of these findings that requires consideration is that in the last few years, atypical antipsychotic medications that were not widely available during some years of this study are now being used in the treatment of schizophrenia. The atypical medications have generally been shown to be as effective or more effective (Kane et al 1988) than haloperidol and other conventional antipsychotic medications for positive symptoms, and for the most part they have a more benign side effect profile; furthermore, at least some studies have found that atypical antipsychotic medications may be superior in treating negative symptoms (Fleish-hacker 1999; Iskedjian et al 1998). It is possible that if those patients who were seemingly receiving limited benefit from the typical antipsychotic medications in this study had received one of the newer atypical antipsychotic medications, they might have improved. There is some evidence to support this notion. Although neither the placebo patients nor those in the reference group discharged on clozapine showed a statistically significant improvement in delta, when the two groups of patients were analyzed together, there did appear to be improvement (mean difference = 5.25; 95% CI = −0.49, 10.98; t = 1.92; p = .07). This result highlights the potential importance of these newer medications for treating patients with chronic schizophrenia and the benefits that such research trials serve if they enable patients to receive them.

Finally, another potentially important limitation is that the rating instrument used in this study (the PSAS) is probably not sensitive to relatively subtle changes. It also does not take into account the number of potentially detrimental events, such as suicide attempts or other acts of violence, that might have occurred during the course of the hospitalization (although no suicides occurred in this study group). A subsequent analysis of these data will address the number and kind of adverse events (for example, hitting another patient) that occurred and when in the course of a patient’s hospitalization these events were noted. We do not know whether more sensitive instruments, such as more formal measures of cognition, might have found long-lasting changes that were not apparent through observation with the PSAS. Nevertheless, previous studies of cognition over time in similar patients have shown little change, at least after the illness has been present for some time, even in the presence of considerable symptom variability (Hyde et al 1994).

Patient Population Limitations

To the degree that the current data can be generalized, they may apply only to fairly chronic, largely treatment-refractory patients. A substantial portion of patients with schizophrenia fit this description, however, and many patients in research trials such as this one also fit this description. Despite being treatment refractory, these patients did worsen when their antipsychotic medications were discontinued; nevertheless, while in treatment they remained severely impaired. Although no change was noted for the patient group ratings from baseline to discharge, given the chronicity of the patients, improvement might not be expected unless novel and more effective interventions had been used.

Limitations Associated with the Nature of Schizophrenia

Another important issue is the one of variability in the course of schizophrenia itself, best highlighted by the variable response time it took patients to respond to medications in the post-placebo phase. By the time patients have been severely ill 11.8 years (the average for patients in our study) and are considered relatively treatment refractory, as was the case for these patients, it is assumed that a relapse is inevitable when antipsychotic medications are discontinued. Yet in the present study, ratings for four patients who had two placebo phases appeared no different when their antipsychotic medications were discontinued, and these four patients remained at their baseline for a year or more. The ability of these patients to function without antipsychotic medications for such a long time highlights the benefits that can be associated with carefully monitored medication-free research. Such benefits include sparing patients further risk of tardive dyskinesia and the discomfort that many experience from traditional antipsychotic medications. Unfortunately, it was not obvious ahead of time which patients apparently did not need to remain on antipsychotic medications, and no predictors emerged from this analysis.

Conclusions

Taken together, the findings from these analyses have serious, and somewhat contradictory, implications for research involving medication-free periods. First, the results suggest that, when given sufficient time, patients with chronic, relatively treatment-refractory, but actively symptomatic schizophrenia who undergo a medication-free trial in a carefully monitored research setting should experience no long-term morbidity as a result of being medication-free. With the exception of those patients who left the study early, by discharge the placebo group had returned to baseline.

On the other hand, many of the patients had not returned to baseline at the end of the 6-week post-placebo phase. This time frame might be considered relatively lengthy, especially in placebo trials where long hospitalizations cannot be provided. This suggests that longer, and perhaps more closely monitored, post-placebo periods will be necessary for an as yet undefined subgroup of patients.

It is possible, or even likely, that the patients in this study experienced psychological pain beyond what was “normal for them” during the course of their placebo participation. And it may simply be this probability that is at the heart of the ethical controversies that surround the conduct of some psychiatric research involving human subjects. There is no controversy, however, that psychiatric illnesses are a terrible burden on patients, their families, and society, and there is widespread acceptance, at least in a general sense, that research is required to make progress toward the prevention, treatment, and cure of psychiatric disorders. Finding the correct balance between improving patient well-being and decreasing patient discomfort requires both knowledge and sensitivity. As we progress toward this goal, and complex ethical discussions continue, we hope the knowledge gleaned from this study can be provided to patients and families to help them decide whether or not to enter research studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Llewelyn Bigelow, William Carpenter, Evan DeRenzo, Mike Egan, Irv Gottesman, Joel Kleinman, and Daniel Weinberger for their helpful suggestions. Debra Heath provided technical assistance, and Joyce Williams patiently provided medical charts. This study would not have been possible without the help of medical staff at the NIMH Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital, or the participation of the patients and their families, to whom we will always be grateful.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-III. 3. Washington, D.C: The American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-III-R. 3. Washington, D.C: The American Psychiatric Association; 1987. revised. [Google Scholar]

- Angst J. European long-term followup studies of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14:501–513. doi: 10.1093/schbul/14.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum P. Rethinking the conduct of psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:117–120. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830140025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum PS. Drug-free research in schizophrenia: an overview of the controversy. IRB. 1996;18:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey BJR. Tables of the Bonferroni t statistic. J Am Statistical Assoc. 1977;72:469–478. [Google Scholar]

- Bartko J, Carpenter W. On methods and theory of reliability. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1976;163:307–317. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197611000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JW, Applebaum PS. Subjects’ capacity to consent to neurobiological research. In: Pincus HA, Lieberman JA, Ferris S, editors. Ethics in Psychiatric Research: A Resource Manual for Human Subjects Protection. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1999. pp. 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow LB, Berthot BD. The Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale (PSAS) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1989;25:168–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleuler M. In: The Schizophrenic Disorders: Long-Term Patient and Family Studies. Clemens SM, translator. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WTJ. The risk of medication-free research. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:11–18. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WTJ, Schooler NR, Kane JM. The rationale and ethics of medication-free research in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:401–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830170015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciompi L. The natural history of schizophrenia in the long term. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:420–423. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi LE, Sakuma M, Tew W, Kushner M, Hoff AL, Grimson R. Schizophrenia as a chronic active brain process: A study of progressive brain structural change subsequent to the onset of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1997;74:129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(97)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRenzo EG, Conley R, Love R. Assessment of capacity to give consent to research participation: State of the art and beyond. J Health Care Law Policy. 1998;1:66–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J, Wichman A. A new consent policy for research with impaired human subjects. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1987;23:382–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhacker WW. Clozapine: a comparison with other novel antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 12):30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn L, Honberg R. Achieving proper balance in research with decisionally-incapacitated subjects: NAMI’s perspective on the working group’s proposal. J Health Care Law Policy. 1998;1:174–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garver DL, Kelly K, Fried KA, Magnusson M, Hirschowitz J. Drug response patterns as a basis of nosology for the mood-incongruent psychoses (the schizophrenias) Psychol Med. 1988;18:873–885. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700009818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glovinsky D, Kirch DG, Wyatt RJ, et al. Early antipsychotic response to resumption of neuroleptics in drug-free chronic schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31:968–970. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90124-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T, Applebaum PS. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hall LL, Flynn L. Consumer and family concerns about research involving human subjects. In: Pincus HA, Lieberman JA, Ferris S, editors. Ethics in Psychiatric Research: A Resource Manual for Human Subjects Protection. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1999. pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Sands JR, Silverstein ML, Goldberg JF. Course and outcome for schizophrenia versus other psychotic patients: a longitudinal study. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:287–303. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde TM, Nawroz S, Goldberg TE, et al. Is there cognitive decline in schizophrenia? A cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:494–500. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskedjian M, Hux M, Remington GJ. The Canadian experience with risperidone for the treatment of schizophrenia: an overview. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1998;23:229–239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Wyatt RJ. Understanding and Treating Tardive Dyskinesia. New York: Guilford Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DAW, Pasterski G, Ludlow JM, Street K, Taylor RDW. The discontinuance of maintenance neuroleptic therapy in chronic schizophrenic patients: Drug and social consequences. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:339–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J, Honigfeld G, SInger J. Clozapine for the treatment-resistent schizophrenic: A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE, Cohen BM, Baldessarini RJ, McElroy SL. Time course of antipsychotic effects of neuroleptic drugs. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:1289–1292. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.10.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraepelin E. In: Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia (1919) Barclay RM, translator. Huntington, NY: Robert E. Krieger; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen TK, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S. First-episode schizophrenia with long duration of untreated psychosis: pathways to care. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(Suppl 33):45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman J, Jody D, Geisler S, et al. Time course and biological correlates of treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:369–376. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820170047006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA. Prediction of outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PRA, Goldberg SC. Prediction of schizophrenic patients’ response to pharmacotherapy. In: Lipton MA, Di-Mascio A, Killam KF, editors. Psychopharmacology: A Generation of Progress. New York: Raven Press; 1978. pp. 1139–1153. [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH. A selective review of recent North American long-term followup studies of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14:515–542. doi: 10.1093/schbul/14.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bioethics Advisory Commission. Research involving persons with mental disorders that may affect decision making capacity, Volume 1. Report and recommendations of the National Bioethics Advisory Commission. Washington DC: National Bioethics Advisory Commission; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nedopil N, Ruther E. Initial improvement as predictor of outcome of neuroleptic treatment. Pharmacopsychiatria. 1981;14:205–207. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1019599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Res. 1962;25:168–179. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer D, Henter I, Wyatt RJ. Do antipsychotic medications decrease the risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia? J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 2):100–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power P, Elkins K, Adlard S, Curry C, McGorry P, Harrigan S. Analysis of the initial treatment phase in first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(Suppl 33):71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautter F, McDermott B, Garver D. Familial differences between rapid neuroleptic response psychosis and delayed neuroleptic response psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;33:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90273-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern RG, Kahn RS, Davidson M. Predictors of response to neuroleptic treatment in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1993;16:313–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski S, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, et al. Gender differences in onset of illness, treatment response, course, and biologic indexes in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:698–703. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.5.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt DC, Katz K, Shepherd M. The natural history of schizophrenia: A 5-year prospective follow-up of a representative sample of schizophrenics by means of standardized clinical and social assessment. Psychol Med. 1983;13:663–670. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700048091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt RJ. Antipsychotic medication and the long-term course of schizophrenia: therapeutic and theoretical implications. In: Shriqui C, Nasrallah H, editors. Contemporary Issues in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. pp. 385–410. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt RJ. Research in schizophrenia and the discontinuation of antipsychotic medications. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:3–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt RJ. Neuroleptics and the natural course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:325–351. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt RJ, Henter I. The effects of sustained intervention on the long-term morbidity of schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00014-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]