The Deriving Induced Stem Cells Using Stored Specimens (DISCUSS) project is a consensus-building initiative designed to consider how human somatic cells obtained under general biomedical research protocols can be used in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derivation. This report presents a revised list of points to consider for the use of previously collected specimens in iPSC research, as well as a summary of published feedback of the previous version.

Summary

Human somatic cell reprogramming is a leading technology for accelerating disease modeling and drug discovery. The Deriving Induced Stem Cells Using Stored Specimens (DISCUSS) project is a consensus-building initiative designed to consider how human somatic cells obtained under general biomedical research protocols can be used in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derivation. We previously published a draft list of points to consider for the use of previously collected specimens in iPSC research and then initiated a structured feedback and comment process. Here, we present a summary of this feedback and revised list of points to consider.

Introduction

The Deriving Induced Stem Cells Using Stored Specimens (DISCUSS) Project is a collaboration designed to develop consensus for the use of previously collected human research specimens (typically stored blood samples or cultured cell lines) for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derivation, research, and distribution. In August 2013, the project published preliminary points to consider [1]. The purpose of this publication was to elicit discussion and comment on nine statements intended to support the evaluation of protocols for the use of previously collected research specimens obtained from human adult donors in iPSC research. Following this publication, the DISCUSS project convened a series of fora to elicit feedback on the published points. The process culminated with a workshop in March 2014, during which international participants directly involved in human specimen research and banking reviewed the points to consider along with a summary of comments received [2]. In this publication, we summarize the major themes that emerged from the feedback process and present a revised list of points to consider.

The DISCUSS Context

For the DISCUSS project, we focused our points to consider on collections of human specimens that were obtained with consent for biomedical research use. Our questions centered on whether the original consent was sufficient to permit the derivation of iPSCs and their subsequent banking and distribution for use in future biomedical research studies. With this approach, we aim to bridge the issues of the appropriate use of previously banked human specimens for future research studies involving derived iPSCs. This emphasis was driven, in part, by the recognition that existing specimen collections have intrinsic scientific value because they may be well-characterized, cover rare diseases, encompass phenotypic progression within a defined cohort, or possess special population characteristics that cannot be easily replicated. In addition, we were aware of cases where repository administrators (and other governance bodies) had rejected applications from newly derived iPSCs from well-characterized disease collections over the adequacy of the original consent supporting original specimen collection.

Major Themes From Comments, Forums, and the Workshop

The feedback process included discussion of the nine statements contained in the original publication, as well as consideration of broader issues in stem cell research and biobanking. A number of recurrent themes emerged in the context of these discussions. We have grouped these themes into six categories represented by the statements below.

Cellular Reprogramming Is a Frontier of Science

Participants noted the remarkable potential for stem cell science to advance both individual and population health. This potential underscored the importance of considering how existing and future specimen collections can be used ethically in stem cell research. The DISCUSS workshop included presentations describing the use of human-derived iPSCs to prevent infectious disease and reduce chronic disease burden [3, 4]. This potential for stem cell science to advance public health and regenerative medicine creates an imperative to use established specimens effectively. Further, a best-science approach supports beneficence by seeking to maximize possible health benefits from specimen donation (see statement 2).

Procedural Mechanisms Should Guide the Use of Secondary Specimens

Comprehensive national and international policy governing the collection of human donor specimens for stem cell derivation and banking have been established. However, these policies are commonly directed to address prospective collection of research specimens. Across jurisdictions, existing guidelines for the use of secondary specimens tend to emphasize legalistic evaluation standards; as such, compliance determination is based on strict conformity (or compatibility) with policy requirements [5, 6]. For example, the 2010 National Academy of Sciences (NAS) Guidelines state, “new derivation of stem cell lines from banked tissue obtained prior to the adoption of these [the NAS] guidelines are permissible provided that the original donations were made in accordance with the legal requirements in force at the place and time of donation” [7].

A determination of compliance at the time of donation, as suggested by NAS, is an important prerequisite. In many international jurisdictions, policies allowing for the deidentification of specimens results in wide research use without being subject to further ethics review or consent. Feedback obtained during our consultation process, however, cautioned against the use of specimen deidentification or anonymization as a means of achieving compliance for specimens that were otherwise not collected with consent adequate to address iPSC derivation. Commenters noted that internationally, there is increasing emphasis on having procedures in place to examine the acceptability of new uses of banked specimens in relation to the original donor consent [5, 6, 8]. For example, the U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections suggests:

Institutions should establish mechanisms to determine whether secondary uses are compatible with the original informed consent; this could involve consultation with the IRB that approved the original research, or review by some other body designated for these purposes. Coding should not be used as a means to circumvent the original terms of consent. This is ethically problematic, even if the original project is over and the secondary use is no longer considered to be research involving human subjects [9].

Taking steps to ensure that iPSC derivation is compatible with the original consent is all the more important when the intention is to deposit the line to a repository for subsequent redistribution and use. Therefore, emerging national and international guidelines for the secondary use of specimens are emphasizing the need for procedural or governance mechanisms to determine whether secondary uses are compatible with the original donor consent [10].

Repositories Should Conform to International Standards for Biobanking

Commenters emphasized that any repository receiving derived iPSC lines with the intention to redistribute them should meet a minimum of core competencies. Guidelines and standards exist for all aspects of collection, storage, retrieval, usage, and distribution of specimens [11]. To enhance trust among research participants and the public, it is essential that the repository receiving iPSC lines conform to internationally accepted ethical principles, as well as best-practice guidelines and standards.

Operationally, the repository should have mechanisms in place to support the responsible use of specimens. To support responsible use, requests for specimens should undergo scientific and/or administrative review to ensure appropriate use by qualified researchers. Material transfer agreements should be used to document and enforce conditions for use. Further, repositories should consider developing reporting mechanisms to better enable donors to understand how specimen collections are used.

Effective Biorepository Systems Enhance Trustworthiness

Biomedical research increasingly depends upon the development of systems to facilitate the exchange of materials and data. Systems exist for managing cells and tissue, gene sequencing and other “omics” data, images, and molecular tools among others. Collectively, these systems support research discovery, validation, and knowledge dissemination. Stem cell science is a leading example in which numerous projects have been initiated internationally to derive, characterize, register, bank, and distribute cell lines and associated data, such as the European Bank for Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (Babraham, U.K., http://www.ebisc.org), the Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Initiative (Cambridge, U.K., http://www.hipsci.org), and the Riken Bioresource Center Cell Bank (Ibaraki, Japan, http://www.brc.riken.jp/lab/cell/english).

Repositories play a central role in mediating the exchange of materials and data. For repository systems, there are established procedures and protocols for the collection, storage, retrieval, and distribution of specimens along with data for research [6]. Commenters emphasized how effective repository systems serve to build trustworthiness among research participants and the public. In this context, trustworthiness emanates from a system of operations and governance that performs the following functions:

Advances the effective and responsible use of donor specimens

Supports research integrity

Responds to societal and/or participant needs and concerns

Maintains feedback mechanisms to validate the effectives of operations and governance systems

Established biobanking procedures and protocols typically include governance structures and operational mechanisms to address the points above, such as informed consent, procedures to allow withdraw from research, materials transfer agreements, and independent ethics and scientific oversight. Workshop participants suggested operations and governance systems must be “robust and proportionate” according to variation in risk, societal values, and scientific needs. Proportionality suggests there may be variation in specific rules governing banking and distribution procedures depending on the jurisdiction. Thus, the overall goal is to design systems for material and data exchange that can accommodate such variance.

Societal Concerns Exist and Should Be Addressed

Anecdotal and empirical evidence was presented indicating that cell and tissue donors express concerns over how materials may be used. For example, at the DISCUSS workshop, findings from a U.S.-based focus group study that elicited patients’ attitudes toward the donation of cells for iPSC research were presented [12]. The study suggests that concerns exist regarding the following:

Reidentification of the donor, privacy infringements, and the potential for this information to be used in an unfair or discriminatory manner

Inability to control the downstream use of cells and prevent their inappropriate use

Commercial aspects of cell use

Using cell reprogramming to create gametes or to perform human cloning

Somatic cell nuclear transfer studies without explicit donor consent

The study also found that mitigating factors could serve to address stated concerns. Specific actions include the following:

Robust informed consent procedures

Transparency in disclosing information relating to how materials are and will be used and their commercial potential

The study’s authors suggest that effectively addressing stated concerns could serve to build trust in research. Additionally, a representative from the H3Africa initiative identified broader social concerns about the use of cultured tissue [3, 13]. Specifically, in the African context, there are deeply rooted social and cultural beliefs regarding the appropriate use of human tissue and the resulting knowledge gained from its use in research. For example, historical experience with exploitative human trafficking raises concerns over specimens being distributed internationally for research. In response, the H3Africa project is considering a number mitigating procedures and policies designed to ensure benefits to African donors and researchers [4]. This illustrates how responsive governance mechanisms can serve to address donors’ and communities’ concerns.

The Points Above Are Broadly Applicable

The DISCUSS Project was ostensibly designed to address a specific research context: the derivation of iPSC lines from previously collected research specimens from an adult donor, for subsequent deposit to a repository for distribution and use in biomedical research. Commenters recognized the utility of an iPSC focused effort, given that the DISCUSS Project team was directly involved in supporting stem cell science. However, there was also consensus that the points to consider are generally applicable to the context of cultured human tissue research as well, because of the potential to transform and distribute these specimens. For example, in the DISCUSS Workshop, scientists described how human cord blood could be readily transformed into pluripotent, multipotent, and differentiated cells. Transformed cells are being applied in a variety of in vitro and in vivo applications, including disease modeling and therapy development [14].

A Priori Considerations

We have revised our list of points to consider and retained our focus on general biomedical research protocols designed to derive and distribute iPSC lines from previously collected adult research specimens. The revised framework includes both specific evaluative criterion and the broader repository research system in which they should be applied. In addition, we eliminated our original ninth statement because commenters indicated the suggested scenario was not applicable. The framework is designed to assist researchers, cell repositories, and oversight and review bodies, as well as funding agencies, in the design of programs and policies to support secondary use of specimens.

Commenters felt it was important to emphasize the need to ensure that the original specimen, at a minimum, conformed to core ethical standards of (a) voluntary informed consent and (b) oversight by an independent ethics review board (e.g., institutional review board (IRB) or equivalent). In the U.S. context, for example, compliance with the Common Rule satisfies these conditions for determining ethical provenance. If such a determination cannot be made, derived cell lines may have limited utility, because national and international biobanking guidelines increasingly require a determination that there was appropriate consent and oversight [15]. Also, it was noted that not all specimens collected under IRB approval could be used for all types of research, so consent evaluation is a necessary step.

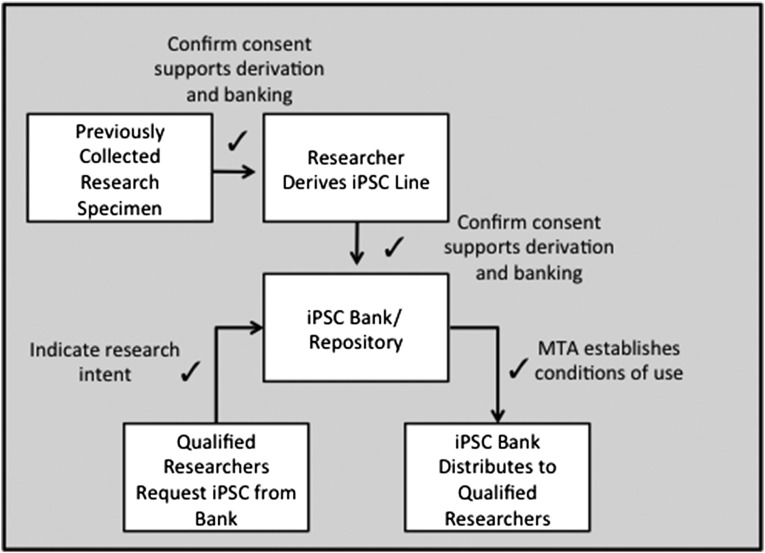

Figure 1 illustrates two points in the derivation and banking cycle where consent evaluation may be performed. Ideally, the researcher will use specimens with the knowledge that appropriate consent was obtained at the time of collection. In the case where a previous collected specimen resides in a cell or tissue repository, the researcher proposing iPSC derivation should describe such use a priori. Often a statement of research intent is submitted when requesting a specimen. An appropriately constituted neutral third party such as a tissue use committee or an IRB should review the research request and consider any restrictions against uses for which there is not appropriate consent.

Figure 1.

Opportunities to confirm consent. There may be specimens that are appropriate for iPSC derivation and research use within a confined context, such as a particular laboratory or institution, but not suitable for broad distribution, as for instance in a commercial repository. A common example is a case in which a researcher may obtain consent from donors to derive iPSC lines with the stipulation that the researcher will retain control of the cell lines. Such lines would not be appropriate for distribution by a third party. A number of commenters pointed out that it is standard practice for a banking entity to have a governance system in place to perform provenance review as suggested by internationally recognized best-practice guidelines. The review is intended to determine (a) that the initial collection was conducted with voluntary donor consent and independent oversight and (b) whether the informed consent protocol would allow for the deposit and distribution of cell lines. Typically, the repository requires evidence of human subject oversight and the donor consent associated with a particular cell line. This review by the banking entity serves to ensure appropriate (e.g., ethical, scientific) use of research specimens. Abbreviation: iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell.

Revised Points to Consider

Statement 1

A review should be performed to ensure that iPSC derivation and distribution are not specifically precluded by, or otherwise in conflict with, the original informed consent. Common examples of where conflicts may arise include language indicating the following:

The original principal researcher and/or the primary research team will manage the distribution of specimens or their products.

The specimen will only be used to study a particular disease or condition.

The specimen or resulting information will not be used for commercial purposes.

The specimen will be used or distributed only within a certain jurisdiction.

iPSC lines containing limitations on use should only be deposited in a repository if transfer agreements address such restricted uses in conformity with the scope of the donor’s consent. Moreover, subsequent transfer agreements for secondary or tertiary research should comply with any restrictions stipulated in the original donor’s consent.

Statement 2

If the consent protocol indicated that the specimen would be used in disease research, iPSC derivation and use should be considered compatible with this purpose. iPSCs have become a standard tool for modeling disease and testing potential therapies. The consent review should consider whether it is reasonable to conclude that donors were informed that a best-science approach would be used to perform disease research. In this context, iPSCs serve as a research tool in contemporary disease research. A best-science approach supports beneficence by seeking to maximize possible societal benefits of specimen donation.

If the consent protocol indicated that biospecimens would only be used to study a particular disease or condition, the use of biospecimens to derive iPSCs to study the specified disease condition should be considered consistent with the intended purpose (i.e., even if iPSCs were not mentioned explicitly in the previous consent protocol). Material transfer agreements accompanying distributed biospecimens and iPSC lines should reflect any limitations related to the disease or condition that may be studied.

Statement 3

A reference to the sharing of biospecimens with other researchers in the original consent form is sufficient for distributing material via an iPSC repository. Indicating that the specimens will be used broadly in research may also be sufficient, provided wide distribution is not precluded (see statement 1).

Sharing biospecimens with other researchers has become common practice and is consistent with broad data-sharing goals that have been articulated to support beneficence and maximize the societal benefits of publicly funded research. Repositories are a primary means of distributing iPSC lines. Therefore, deposit in a repository can be deemed to be consistent with a reference to sharing biospecimens with other researchers and/or broad research use, provided the repository conforms to international standards for biobanking [11].

Statement 4

Before individual-level genotypic sequence data are deposited into a repository or a research database (e.g., one that is publicly accessible), researchers should determine that the original consent included a reference to genetic research and the risks thereof. In addition, a determination should be made to ascertain whether the deposit results in substantial new risks to the donor about which they have not been informed and whether there are any legal restrictions on deposition.

The reporting of individual genotypic data affects the privacy interests of the donor (see, for example, [6]), regardless of whether the data have been deidentified. Such reporting should not take place unless the donor has been informed of and has consented to genetic studies or genomic sequencing. In addition, the repository receiving the data should maintain a level of administrative control sufficient to determine who has accessed specific sequence data.

However, the absence of such a disclosure does not necessarily mean that genomic analysis and characterization is inappropriate in the context of a specific study or that population-level genomic data cannot be shared. For example, genotypic analysis may be integral to research intended to elucidate a disease mechanism. This statement pertains only to the conditions under which individual genotypic sequencing data may be placed in the broadly accessible databases [16].

Statement 5

Researchers should determine whether the original donor consent included a reference to commercial use prior to the use of donated specimens in the development of cell lines or derivatives (e.g., proteins or nucleic acids) as commercial products. The donor should be informed that materials may be used for commercial purposes and that the donor will not have legal or financial interest in any resulting commercial development or patents.

Statement 6

Researchers should determine whether the donor was informed of the possibility of using his or her specimens in the creation of human transplantation products, prior to the derivation of a cell line or cell product intended for human transplantation. Although we expect it to be rare that a biospecimen previously collected for research purposes will be redirected to create cell lines/products for human transplantation or clinical use, there might be a particularly valuable cell line amenable to this purpose. Donors should consent explicitly to the use of their specimens in human transplantation.

Statement 7

Reference to unspecified or unforeseen future studies or research in the consent document should be interpreted to refer to activities designed to develop or contribute to generalizable scientific knowledge. However, such a reference to unspecified or unforeseen studies or research should not be interpreted to include developing the resulting cells lines or derivatives (e.g., proteins or nucleic acids) into commercial or human transplantation products.

Statement 8

iPSCs should not be used for studies intended to generate gametes or embryos without a specific consent. In addition to ensuring that applicable law, policy, and material transfer agreements are followed, the development of gametes from somatic cells should only take place with specific consent from the original donor. We are hesitant to suggest exceptional conditions be placed on the use of iPSCs but also believe, especially in the context of previously collected specimens, that such use would be outside of what a donor could have reasonably contemplated during the consent process. For example, we have previously recommended that gamete creation and embryogenesis be specifically highlighted and addressed in the prospective consent context [17]. Given the sensitivity of this line of research, researchers have a responsibility to be transparent with donors regarding the use of their specimens in this research.

Discussion

Commenters indicated that the circumstances requiring the most in-depth consideration were research activities not specifically addressed in the original consent form. Oversight bodies and ethics review boards typically spend considerable effort to address instances when the consent was silent with regard to iPSC derivation and banking, but such research could be construed as consistent with the research purpose. In the original publication, statement 2 proposed that iPSC derivation should be considered as a standard method for disease modeling and therapy development. Similarly, other basic research tools and technologies, like genetic sequencing and characterization, represent contemporary methods for performing biomedical research. Using them would constitute a best-science approach for accomplishing the intended purpose of the research.

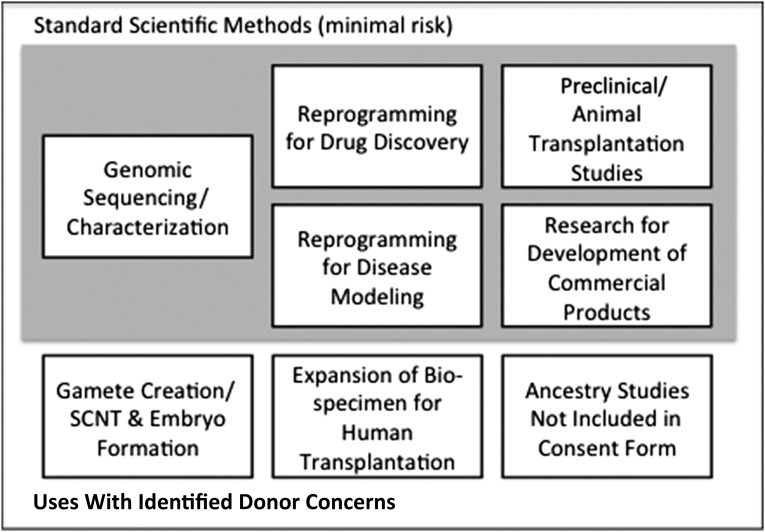

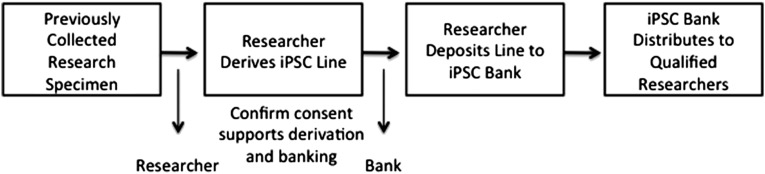

Evidence presented at the workshop also suggests that societal concerns can emerge from the subsequent use of cell lines or associated genetic information, for example, to create gametes or embryos or to discriminate or otherwise disadvantage donors. Expanding cells for human transplantation is another use where specific consent should be obtained. Studies seeking to characterize the ancestry of research participants were specifically highlighted because their results have the potential to effect nonparticipants who are also members of groups with shared ancestry [18]. Therefore, it is important to focus on how data or resulting iPSC lines are used. Figure 2 illustrates certain activities (gray shading) that appear consistent with research consent aimed at disease research and therapy development. There are also uses for where particular donor concerns have been identified (no shading). Figure 3 illustrates points where researchers and repository administrators can act to ensure that specimens are used appropriately.

Figure 2.

Standard methods and special considerations. Workshop participants highlighted a variety of mechanisms routinely used in repository systems to support the responsible use of data and materials. For example, researchers requesting cells from a repository should describe the intended use of the materials. The repository distributing the cell lines should consider whether such use is consistent with the original consent. Further, repositories distributing lines can use materials transfer agreements to define the appropriate conditions for use of materials or data. Abbreviation: SCNT, somatic cell nuclear transfer.

Figure 3.

Checkpoints in repository systems. Abbreviations: iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cells; MTA, materials transfer agreement.

Conclusion

A major goal of the DISCUSS project is to develop consensus on the responsible use of previous collected specimens in stem cell research specifically and biomedical research generally. This topic is one of international interest because research programs are being initiated to apply cellular reprogramming toward public health and regenerative medicine.

The development of scientific programs generally includes deliberation concerning governance and research ethics. Numerous participants in the DISCUSS project deliberations indicated that the guidance provided by the DISCUSS Project: Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines From Previously Collected Research Biospecimens and Informed Consent: Points to Consider was useful for supporting program development.

The engagement process suggested that there is utility to the points to consider, with considerable focus on a systems approach to supporting responsible and trustworthy research. We have attempted to capture this focus in the report by highlighting the relationship between operational aspect of repository systems and the application of the points to consider. Thus, we aim to highlight the role of researchers, oversight bodies, and repositories in supporting the responsible conduct of research.

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed above are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of the NIH, the U.S. Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The points to consider do not form policy of a U.S. federal agency or the International Stem Cell Forum. We acknowledge the International Stem Cell Forum and the Stem Cell Network of Canada for funding support and Justin Lowenthal, Mahendra Rao, and the DISCUSS Workshop participants for their intellectual contribution to this work.

Author Contributions

G.P.L.: conception and design, assembly of data, financial support, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; S.C.I. and R.I.: financial support, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

R.I. has compensated research funding from a grant from the Stem Cell Network and the International Stem Cell Forum. The other authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lomax GP, Hull SC, Lowenthal J, et al. The DISCUSS Project: Induced pluripotent stem cell lines from previously collected research biospecimens and informed consent: Points to consider. Stem Cells Translational Medicine. 2013;2:727–730. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DISCUSS Project. Deriving iPS Cells from Previously Collected Research Biospecimens: The DISCUSS Workshop Report. Available at http://www.cirm.ca.gov/sites/default/files/files/about_cirm/Final_DISCUSS_Workshop_Report_7_3_14.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- 3.Abayomi A, Christoffels A, Grewal R, et al. Challenges of biobanking in South Africa to facilitate indigenous research in an environment burdened with human immunodeficiency virus, tuberculosis, and emerging noncommunicable diseases. Biopreserv Biobank. 2013;11:347–354. doi: 10.1089/bio.2013.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vries J, Abayomi A, Brandful J, et al. A perpetual source of DNA or something really different: Ethical issues in the creation of cell lines for African genomics research. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:60. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-15-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Australia, National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated December 2013). The National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and the Australian Vice-Chancellors’ Committee. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

- 6. Canada, Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS 2, 2010). Panel on Research Ethics: Proposed changes to the TCP2, 2013.

- 7. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2010. Final Report of the National Academies’ Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research Advisory Committee and 2010 Amendments to the National Academies’ Guidelines for Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Available at http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12923/final-report-of-the-national-academies-human-embryonic-stem-cell-research-advisory-committee-and-2010-amendments-to-the-national-academies-guidelines-for-human-embryonic-stem-cell-research. Accessed August 29, 2014.

- 8. Spain, Royal Decree. Law No.7065 No. 9/2014, of July 4, 2014.

- 9. FAQs, Terms and Recommendations on Informed Consent and Research Use of Biospecimens. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP), July 20, 2011. Available at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp/commsec/attachmentdfaq%27stermsandrecommendations.pdf.pdf Accessed December 1, 2014.

- 10. Bunn, S. Biobanks: POST Note. 2014. Available at http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/POST-PN-473/biobanks. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- 11. 2012 best practices for repositories: Collection, storage, retrieval and distribution of biological materials for research. Biopreserv Biobank 2012;10:79–161. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Dasgupta I, Bollinger J, Mathews DJ, et al. Patients’ attitudes toward the donation of biological materials for the derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. H3Africa: Human Heredity & Health in Africa Initiative. Available at http://www.h3africa.org/. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- 14. Summary and Recommendations of the CIRM Human iPS Cell Banking Workshop, San Francisco, November 17–18, 2010. San Francisco, CA: California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Available at http://www.cirm.ca.gov/sites/default/files/files/about_cirm/iPSC_Banking_Report.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- 15.Medical Research Council. Code of Practice for the Use of Human Stem Cell Lines. 1–45 (2010). Available at http://www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/code-of-practice-for-the-use-of-human-stem-cell-lines/. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- 16.Isasi R, Andrews PW, Baltz JM, et al. Identifiability and privacy in pluripotent stem cell research. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shineha R, Kawakami M, Kawakami K, et al. Familiarity and prudence of the Japanese public with research into induced pluripotent stem cells, and their desire for its proper regulation. Stem Cell Rev. 2010;6:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12015-009-9111-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gymrek M, McGuire AL, Golan D, et al. Identifying personal genomes by surname inference. Science. 2013;339:321–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1229566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]