Summary

Aims

Rasmussen encephalitis (RE) is a rare but devastating condition, mainly in children, characterized by sustained brain inflammation, atrophy of one cerebral hemisphere, epilepsy, and progressive cognitive deterioration. The etiology of RE‐induced seizures associated with the inflammatory process remains unknown.

Methods

Cortical tissue samples from children undergoing surgical resections for the treatment of RE (n = 16) and non‐RE (n = 12) were compared using electrophysiological, morphological, and immunohistochemical techniques to examine neuronal properties and the relationship with microglial activation using the specific microglia/macrophage calcium‐binding protein, IBA1 in conjunction with connexins and pannexin expression.

Results

Compared with non‐RE cases, pyramidal neurons from RE cases displayed increased cell capacitance and reduced input resistance. However, neuronal somatic areas were not increased in size. Instead, intracellular injection of biocytin led to increased dye coupling between neurons from RE cases. By Western blot, expression of IBA1 and pannexin was increased while connexin 32 was decreased in RE cases compared with non‐RE cases. IBA1 immunostaining overlapped with pannexin and connexin 36 in RE cases.

Conclusions

In RE, these results support the notion that a possible mechanism for cellular hyperexcitability may be related to increased intercellular coupling from pannexin linked to increased microglial activation. Such findings suggest that a possible antiseizure treatment for RE may involve the use of gap junction blockers.

Keywords: Gap junctions, Hyperexcitability, Pannexin, Rasmussen encephalitis

Introduction

Rasmussen encephalitis (RE) is a rare but devastating condition involving severe unihemispheric brain inflammation and epileptic seizures generally unresponsive to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) 1, 2. RE is usually a childhood disease with an age of onset around 2–10 years 3, 4 and is associated with epilepsia partialis continua (EPC) in about 50% of patients 5. Over time, patients develop hemiparesis, visual loss, and speech and mental disabilities associated with cerebral hemiatrophy. In most cases, complete hemispherectomy represents the only option to control epileptic activity and progression of the disease 6. Histopathological findings demonstrate the presence of inflammation dominated by CD8+ T‐cells, widespread microglial activation, perivascular lymphoid cells, and glial scarring sometimes with cystic cavitation 7, 8, 9.

The cause(s) of RE and why or how the brain inflammation produces severe seizures and EPC remain unknown. Studies have failed to demonstrate a causal association between any specific virus and RE 6, 10, 11. Further, although it was initially proposed that autoantibodies against the GluA3 ionotropic glutamate receptor subunit or against the N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor subtype may play a role in producing seizures 12, 13, 14, 15, more recent studies have shown that the presence of autoantibodies against GluA3 or NMDA receptors is not exclusive for RE, but also occurs in other epileptic manifestations 16, 17, 18, 19.

Due to the relative rarity of RE, approximately 2.7% of pediatric epilepsy surgery patients 20, virtually nothing is known about the basic electrophysiological mechanisms that cause seizures in these patients. Our laboratory has pioneered the use of surgical tissue resected for the treatment of pharmacoresistant pediatric epilepsy to study electrophysiological mechanisms of epileptogenesis. In the past years, we have assembled a critical number of RE cases to perform an analysis compared with other brain pathologies, particularly cortical dysplasias (CD) 21. The present study was designed to investigate electrophysiological membrane and synaptic properties of pyramidal neurons from RE compared with non‐RE cases. In the course of these studies, we discovered that cell membrane properties in RE cases might be altered as a consequence of increased electrotonic coupling between pyramidal neurons related to microglial activation and increased pannexin protein expression forming hemichannels.

Subjects and Methods

The research protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Human Research Protection Committee at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). Informed consent to use the surgically resected tissue for research was obtained from parents or legal guardians. This was not a clinical trial and is not registered in any public registry.

Patient Cohorts and Evaluation

Consecutive surgical patients with RE (n = 16) from 2001 to 2012 were included. All patients had neuroimaging features of RE including progressive unilateral hemispheric atrophy and histopathological findings consistent with RE. For this study, RE cases were compared with as normal tissue as possible from non‐RE cases (n = 12) mostly from subjects with cerebral infarcts (n = 6), tumors (n = 4), and mild CD (ILAE classification CD type Ib; n = 2) 22 matched for age at surgery. The clinical protocols to evaluate patients have been described in detail 23, 24. In brief, the standardized evaluation included medical history and neurological examinations, as well as interictal and ictal scalp EEG video recordings. Neuroimaging studies included 1.5T MRI and FDG‐PET 25. Clinical data were abstracted from the medical records and included the following: age at seizure onset, age at surgery, type of operation (hemispherectomy, multilobar, lobar/focal), side of operation, gender, seizure freedom after surgery, and duration of follow‐up 24. Epilepsy duration was calculated as the interval in years from age at seizure onset to age at surgery.

Sample Selection for Electrophysiology

Neocortical sample sites were excised for in vitro electrophysiological evaluation based on abnormal neuroimaging and electrocorticography (ECoG) assessments. Tissue samples were classified as most abnormal (MA) and least abnormal (LA) according to published criteria 21. Sample sites (about 2 cm3) were removed microsurgically and directly placed in ice‐cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing the following (in mM): NaCl 130, NaHCO3 26, KCl 3, MgCl2 5, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 1.0, glucose 10 (pH 7.2–7.4). Within 5‐10 min, slices (350 μm) were cut (Microslicer, DSK Model 1500E or Leica VT1000S) and placed in ACSF for at least 1 h (in this solution, CaCl2 was increased to 2 mM and MgCl2 was decreased to 2 mM). Slices were constantly oxygenated with 95% O2–5% CO2 (pH 7.2–7.4, osmolality 290–300 mOsm, at room temperature). After incubation, tissue slices were transferred to a custom‐designed chamber attached to the fixed stage of an upright microscope. Slices were held down with thin nylon threads glued to a platinum wire and submerged in continuously flowing oxygenated ACSF (25 °C) at 3–4 ml/min. Individual cells were visualized with a 40× water immersion objective using infrared illumination and differential interference contrast optics 21. Cells were sampled in layers II‐VI. The patch electrodes (3–6 MΩ impedance) were filled with an internal solution containing (in mM) the following: Cs‐methanesulfonate 125, NaCl 4, KCl 3, MgCl2 1, MgATP 5, ethylene glycol‐bis (β‐aminoethyl ether)‐N,N,N′,N′‐tetraacetic acid (EGTA) 9, HEPES 8, GTP 1, phosphocreatine 10, and leupeptin 0.1 (pH 7.25–7.3, osmolality 280–290 mOsm). Electrodes also contained 0.2% biocytin in the internal solution to label recorded cells. Glutamate receptor agonists, NMDA and α‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), were applied in the bath or iontophoretically. 4‐aminopyridine (4‐AP), a proconvulsant drug that increases neurotransmitter release, and mefloquine (MFQ), a gap junction blocker, were bath‐applied.

Cells were initially held at −70 mV in voltage clamp mode. Passive membrane properties were determined by applying a depolarizing step voltage command (10 mV) and using the membrane test function integrated in the pClamp8 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). This function reports membrane capacitance (Cm, in pF), input resistance (Rm, in MΩ), and decay time constant (Tau, in ms). The time constant is obtained from a single exponential fit to the decay of the capacitive transients, and the cell capacitance is obtained by dividing the total charge under the capacitive transient by the membrane potential change. Spontaneous excitatory (E) and inhibitory (I) postsynaptic currents (PSCs) were recorded for 3 min. Spontaneous EPSCs were isolated by holding the membrane at −70 mV, and IPSCs were isolated by holding the membrane at +10 mV in the presence of appropriate antagonists [6‐cyano‐7‐nitroquinoxaline‐2,3‐dione (CNQX) and APV]. Frequency of spontaneous PSCs and kinetic analyses were performed using the Mini Analysis program (Justin Lee, Synaptosoft, version 6.0) and subsequently checked manually for accuracy. The threshold amplitude for the detection of an event (5 pA for sEPSCs; 10 pA for sIPSCs) was set above the root mean square noise (< 2 pA at VHold = −70 mV and < 4 pA at VHold = + 10 mV). sEPSCs and IPSCs with peak amplitudes between 5 and 50 pA and 10–100 pA, respectively, were grouped, aligned by half‐rise time, and normalized by peak amplitude to calculate event kinetics and average amplitude. For each cell, grouped events were averaged to calculate amplitude, rise time, half‐amplitude duration, and decay time.

Western Blots and Immunocytochemistry

Additional cortical samples were collected from the larger surgical resection for Western blots and immunocytochemistry. Fresh‐frozen neocortical samples were homogenized in buffer (50 mM Hepes, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM benzamide, 100 ng/ml leupeptin, 100 ng/ml aprotinin, 0.08 M sodium molybdate, 2 mM sodium P‐pyrophosphate, 0.01% Triton) at a 1:1 ratio. The supernatant was clarified by centrifugation and proteins separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate at 100 V, 0.04 A, 300 W overnight at room temperature. Transfer to nitrocellulose membranes (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) or PVDF membrane (Bio‐Rad, Irvine, CA, USA) was performed at 100 V, 1 A, 100 W for 2 h at room temperature. The nitrocellulose/PVDF membranes were blocked with 3% dry milk in TBS‐T buffer (0.1% Tween‐20, 4% BSA) at 4 °C overnight with constant shaking. Membranes were then incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature and constant shaking in incubation buffer (0.1% Tween‐20, 5% BSA) with the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti‐IBA1 (WAKO, Cat: 016‐20001) at a 1:1000 dilution, rabbit polyclonal anti‐pannexin 1 (Ab60098; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) at a 1:1000 dilution, mouse monoclonal anti‐connexin 32 (SC59948; Santa Cruz International, Dallas, TX, USA) at 1:200 dilution, rabbit polyclonal anti‐connexin 36 (Santa Cruz International, SC14904), and monoclonal anti‐G3PDH (EMD Millipore MAB374) at a 1:5000 dilution. After 3 × 10 min (30 min total) of washing in a 1X TBS and 0.1% Tween solution, blots were incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature with constant shaking and the following horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies: anti‐mouse IgG (Sigma A9044) at a 1:2500 dilution, anti‐mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at 1:2500, and anti‐rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) at 1:2500. Following another 3 × 10‐min (30 min total) wash in a 1X TBS and 0.1% Tween solution, proteins were visualized using a chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) X‐ray film developed with a Fischer Autotank processor (Fischer Industries, Inc. Geneva, IL, USA). Quantification of signals was carried out using densitometric scanning (TotalLab Quant, TotalLab Life Science Analysis Essentials, TotalLab Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 2JE). Detailed immunocytochemical methods for CD3, a T‐cell marker, and CD68, a microglial/macrophage marker, have been described elsewhere 9, 26.

Data Analysis

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Statistical differences between RE and non‐RE cases were examined using Student's t‐test or Mann–Whitney rank sum test, chi‐square, and appropriate one‐ or two‐way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests using the Sigmastat or Statview (SAS, Cary, NC) software.

Results

Clinical Cohort

The clinical characteristics of the RE (n = 16) and non‐RE cohorts (n = 12) were generally similar (Table 1). RE cases were operated on from September 2001 to December 2012, while the non‐RE cases had surgery from September 2005 to December 2012. By design, the non‐RE cases were selected to roughly match the RE cases for age at surgery. The etiologies for the non‐RE cases consisted of relatively normal cortex associated with large cerebral infarcts (n = 6), low‐grade glial tumors (glioma, n = 2; DNET, n = 2), and mild CD (ILAE CD type Ib; n = 2) 22. With the exception of age at seizure onset and duration of follow‐up postsurgery, there were no major differences comparing clinical features of RE versus non‐RE patients (Table 1). As not all cortical tissue samples resected from RE cases were optimal for electrophysiological recordings, because of either age or degree of pathology, only a subset of patients was studied. For electrophysiology, we examined 10 of the 16 RE cases (average age 7.03 ± 0.8 years) compared with 9 non‐RE cases (average age 6.4 ± 1.3 years) that included cerebral infarct (n = 5), heterotopia (n = 2), CD type Ib (n = 1), and one case with unremarkable pathology. Tumor cases were not used for electrophysiology.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical features for Rasmussen encephalitis (RE) and non‐RE cases

| Clinical variable | RE (n = 16) | Non‐RE (n = 12) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (years) | 10.2 ± 3.5 | 9.0 ± 3.6 | 0.354 |

| Epilepsy duration (years) | 3.4 ± 3.2 | 5.8 ± 3.0 | 0.054 |

| Age at seizure onset (years) | 6.9 ± 3.9 | 3.2 ± 2.8 | 0.010 |

| Gender (Female) | 44% (7/16) | 33% (4/12) | 0.576 |

| Side of resection (Left) | 37% (6/16) | 58% (7/12) | 0.274 |

| Surgical procedure | |||

| Hemispherectomy | 100% (n = 16) | 66% (n = 8) | 0.050 |

| Multilobar resection | 0 | 17% (n = 2) | |

| Lobar resection | 0 | 17% (n = 2) | |

| Seizure‐free last follow‐up | 94% (15/16) | 83% (10/12) | 0.378 |

| Duration of follow‐up (years) | 3.9 ± 2.9 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.007 |

Data are presented as mean (±SD) or percentages. P‐values from t‐tests or chi‐square. Statistically significant values (P < 0.05) indicated in Bold type.

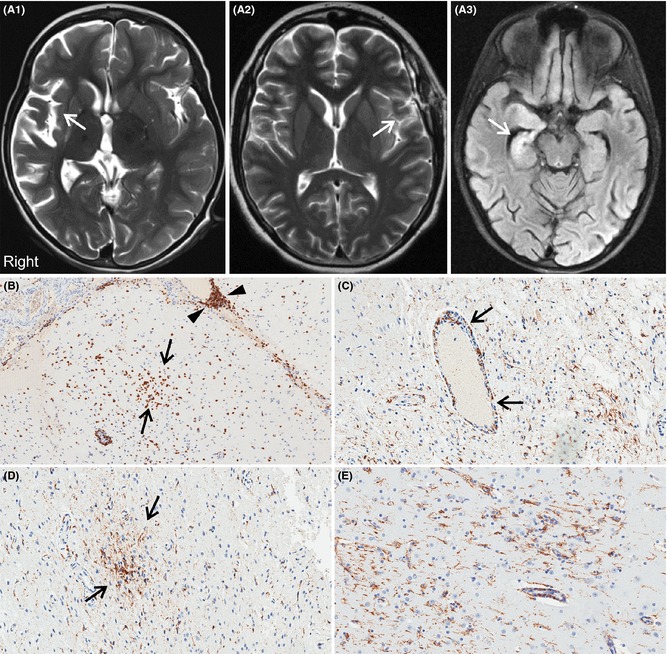

MRI and Histopathological Findings

Most MRI scans of patients with RE showed different degrees of cerebral atrophy, mostly localized around the sylvian fissure (Figure 1A1, A2). Only one case (8 year old with status epilepticus) had a slightly unusual presentation showing MRI changes in the hippocampus (Figure 1A3). MRI scans from non‐RE cases did not show significant atrophy. Histopathological examination revealed that all RE cortical tissue samples displayed inflammatory processes and moderate‐to‐severe gliosis. Focal loss of neurons, astrocytosis, microglial proliferation, formation of microglial nodules, as well as perivascular/leptomeningeal lymphocytic infiltrates, also were commonly observed. The presence of T‐cells and microglia was particularly evident using CD3 and CD68 antibodies, respectively (Figure 1B–E. See also Figure S1). None of the non‐RE cases showed inflammatory infiltrates or microglial nodules. However, mild‐to‐moderate Chaslin's gliosis was observed in all cases.

Figure 1.

Representative axial FLAIR MRI scans of patients with RE all of whom underwent cerebral hemispherectomy. (A1) Typical case showing diffuse right cerebral atrophy centered on the sylvian fissure (arrow). This child was 6 years old with a 2‐year history of progressively worsening right hemispheric seizures. (A2) A 14‐year‐old case with less severe atrophy in the left sylvian fissure (arrow). His seizures began at age 12 years. (A3) Slightly unusual RE presentation with acute status epilepticus and FLAIR signal change in the right hippocampus (arrow) in an 8 year old with a 4‐month history of epilepsy. (B–E) Immunohistochemical features of RE using anti‐CD3 (panel B), a T‐cell marker, and anti‐CD68 (panels C–E), a microglial/macrophage marker. (B) Arrows indicate a cluster of T‐lymphocytes in the brain parenchyma, while arrowheads indicate prominent T‐cells cuffing a meningeal blood vessel. (C) CD68‐immunoreactive macrophages centered on a parenchymal blood vessel (arrows) and low‐grade microglial proliferation throughout adjacent brain parenchyma. Panel D shows a microglial nodule highlighted by anti‐CD68 immunostain. Panel E shows activated microglia throughout the cortex.

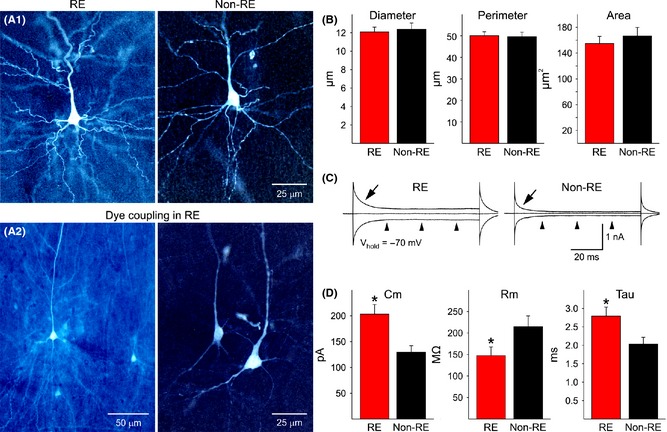

Pyramidal Cell Membrane Properties and Morphology

Cortical pyramidal neurons from RE (n = 44) and non‐RE cases (n = 48) were compared for passive membrane properties, including cell capacitance, input resistance, and decay time constant. Cell capacitance was significantly larger in pyramidal neurons from RE compared with non‐RE cases, while input resistance was lower and the time constant was longer (Figure 2C, D). Increased cell capacitance is usually an indication of larger membrane area. Therefore, we measured morphological properties of recorded cells that were successfully labeled with biocytin (n = 29 from RE and n = 46 from non‐RE cases). The vast majority of pyramidal neurons from RE cases were normal‐appearing, and the somatic areas were similar to pyramidal neurons from non‐RE cases (Figure 2A1, B). In addition, the number of visible primary dendrites also was similar (about 4–5 in pyramidal neurons from RE and non‐RE cases).

Figure 2.

(A1) Panels show representative examples of normal‐appearing pyramidal neurons from RE and non‐RE cases. Cells were recorded and filled with biocytin. They appear similar in terms of somatic area and dendritic elaboration. (A2) Examples of dye coupling in two different RE cases. Only one cell was injected with biocytin, but multiple neurons were labeled, indicating the presence of gap junctions. (B) Graphs show morphological measurements of biocytin‐injected neurons from RE and non‐RE cases, including average somatic diameter, perimeter, and area. (C) Example voltage clamp traces illustrating differences in biophysical membrane properties in a pyramidal neuron from a RE compared with a non‐RE case. Arrows indicate the decay time constant after a depolarizing step voltage command (10 mV) from a holding potential (Vhold) of −70 mV. Notice that the decay time is much slower in the RE neuron compared with the non‐RE neuron, also indicating a much larger cell membrane capacitance. Arrowheads show that the input resistance in the RE neuron is lower than in the non‐RE neuron, that is, the closer the inward or outward current to the midline the higher the input resistance. The cell from the RE case was dye‐coupled. (D) Graphs show average basic membrane properties of pyramidal neurons from RE and non‐RE cases. Cm = cell membrane capacitance, Rm = membrane input resistance, and Tau = decay time constant. Statistically significant differences (indicated by asterisks) were found.

In the absence of gross differences in somatic cell area, larger cell capacitance and decreased input resistance in RE neurons have to be explained by other mechanisms, such as increased gap junction permeability via intercellular connexin (Cx) or pannexin hemichannels. To determine the presence of gap junctions, we examined biocytin‐labeled cells and looked for other cells labeled in the vicinity of the recorded cell. In our experience, dye transfer or dye coupling between cortical pyramidal neurons is negligible (about 10%) in pediatric patients older than 2 years 27. In our cohort, no dye coupling was observed in the non‐RE cohort (n = 9 cases), whereas in RE cases we found that dye coupling occurred in 5 of 10 cases (50%; chi‐square, P = 0.013). Coupling was observed only between pyramidal neurons and appeared to occur by close apposition of dendrites (Figure 2A2). Of 29 successful injections of biocytin, 15 resulted in dye coupling (52%; chi‐square, P = 0.0001). In most cases (n = 12), injections resulted in >3 neurons labeled. From these observations, we can suggest that increased cell capacitance and reduced input resistance could be linked to increased coupling between pyramidal neurons.

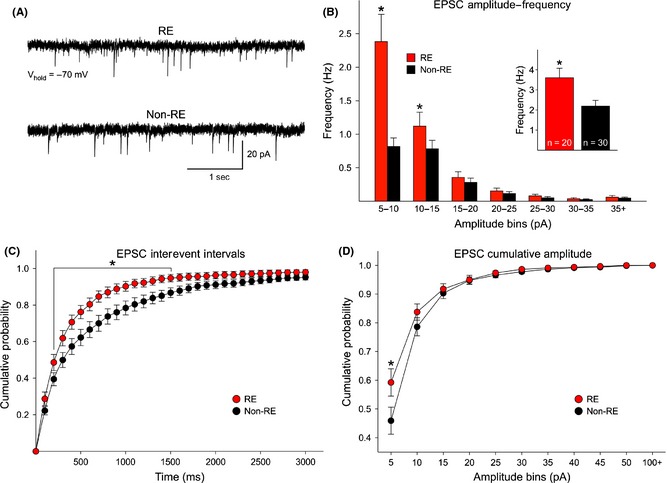

Synaptic and Intrinsic Electrophysiology of Pyramidal Neurons in RE

The frequency and kinetics of sEPSCs and IPSCs were examined in cortical pyramidal neurons from RE and non‐RE cases. At a holding potential of ‐70 mV, the frequency of sEPSCs was significantly higher (t‐test, P = 0.007) in cells from RE compared with cells from non‐RE cases (Figure 3A, B inset). An amplitude–frequency histogram revealed higher sEPSC frequencies in cells from RE cases in practically every amplitude bin. Pairwise multiple comparisons (Bonferroni t‐test) revealed differences in frequency were statistically significant in the 5–10 pA and 10–15 pA amplitude bins (Figure 3B). A cumulative interevent interval histogram also demonstrated a shift to the left (more short intervals) in cells from RE cases (Figure 3C), supporting the finding that in RE, the frequency of sEPSCs is increased and could be a source of hyperexcitability. In contrast, a cumulative amplitude histogram demonstrated no statistically significant difference in overall amplitude distributions (P = 0.189). Only the 5–10 pA bin was different, due to the fact that more events in this amplitude range were observed in cells from RE cases (Figure 3D). Interestingly, the average amplitude of grouped sEPSCs (5–50 pA) was significantly increased in RE compared with non‐RE cases (Table 2). In addition, average rise time, decay time, and half‐amplitude duration were significantly faster in pyramidal neurons from RE compared with non‐RE cases, supporting the idea that changes in glutamate neurotransmission occur at both pre‐ and postsynaptic levels.

Figure 3.

(A) Traces are examples of spontaneous glutamatergic synaptic activity recorded in voltage clamp mode (voltage held at −70 mV). The frequency of spontaneous currents was higher in pyramidal neurons from RE compared with non‐RE cases. (B) The average frequency of spontaneous EPSCs was significantly increased in pyramidal neurons from RE compared with non‐RE cases (inset). In addition, the amplitude–frequency histogram of sEPSCs indicates that the increased frequency was due to more low‐amplitude (5–10 and 10–15 pA) synaptic events. (C) Cumulative probability distributions of interevent intervals (IEIs, a reciprocal of the frequency) demonstrate a significant leftward shift in the probability of IEIs in cells from RE patients, indicating increased frequency of spontaneous synaptic currents. (D) The overall cumulative amplitude probability distributions did not reveal statistically significant differences in cells from RE and non‐RE patients (P = 0.189, two‐way repeated‐measures ANOVA). However, pairwise multiple comparisons (Bonferroni t‐test) revealed a significant difference in the 5–10 pA amplitude range, due to the fact that more events in this amplitude bin occurred in cells from RE cases.

Table 2.

Average amplitude and kinetics of sEPSCs

| Rise time (ms) | Decay time (ms) | Half width (ms) | Amplitude (pA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE (n = 22) | 1.5 ± 0.1* | 5.3 ± 0.4** | 7.1 ± 0.5* | 12.3 ± 0.7** |

| Non‐RE (n = 30) | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | 10.5 ± 0.4 |

Data are presented as mean (±SE). *Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) and **( P < 0.01).

In contrast, the frequency (RE 9.1 ± 2 Hz, n = 9 cells and non‐RE 9.6 ± 1.1 Hz, n = 18 cells), average amplitude (RE 22.9 ± 2.5 pA and non‐RE 25.8 ± 2.0 pA), and kinetics (rise time RE 2.5 ± 0.4 ms and non‐RE 1.9 ± 0.2 ms; decay time RE 10.9 ± 1.4 ms and non‐RE 10.2 ± 0.8 ms; half‐amplitude duration RE 14.5 ± 1.6 ms and non‐RE 12.7 ± 0.7 ms) of sIPSCs were similar, indicating that reduced inhibition is probably not the main cause of cortical hyperexcitability in RE.

In addition to increased glutamatergic input, intrinsic conductances could be responsible for hyperexcitability. A number of pyramidal neurons (n = 6, 14%) from RE cases displayed signs of intrinsic cellular hyperexcitability. For example, most normal‐appearing neurons from RE and non‐RE cases showed small inward calcium currents induced by a depolarizing ramp. In contrast, hyperexcitable RE neurons displayed repetitive Na+ and slowly inactivating Ca2+ spikes. This type of hyperexcitability is exemplified by the trace shown in Figure 4B and recorded from an abnormal‐appearing pyramidal neuron (Figure 4A). In addition, seizure‐like activity was observed in three additional neurons from different RE cases (Figure 4C). However, for the most part, pyramidal neurons from RE cases did not display spontaneous epileptiform activity.

Figure 4.

Some neurons from RE cases displayed signs of hyperexcitability. (A) Biocytin‐filled neuron with bizarre morphology. (B) A slow depolarizing ramp voltage command (−70 to +50 mV) induced repetitive spikes and bursts. (C) In another pyramidal neuron from a RE case, spontaneous ictal‐like activity was observed (holding voltage = −70 mV).

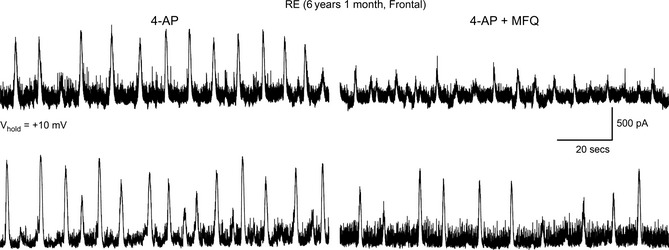

Previous studies have demonstrated that human tissue samples from CD patients are very sensitive to 4‐AP, a K+ channel blocker that augments neurotransmitter release 28, 29. 4‐AP induces interictal and ictal‐like discharges in CD tissue, and gap junctions play an important role as gap junctional blockers reduce 4‐AP oscillations 30. After demonstrating increased coupling between pyramidal neurons, we decided to test the effects of a gap junction blocker, MFQ on 4‐AP oscillations in a RE case. In all cells (n = 3), 4‐AP (100 μM) induced membrane oscillations reminiscent of interictal discharges. Addition of MFQ (25 μM) reduced the amplitude and frequency of 4‐AP oscillations (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Bath application of 4‐aminopyridine (4‐AP, 100 μM) induced membrane oscillations and an increase in spontaneous synaptic activity. At this holding potential (+10 mV), epileptiform activity is mainly mediated by GABAA receptors but also contributed by activation of glutamate receptors. Addition of the gap junctional blocker mefloquine (MFQ, 25 μM) decreased the amplitude and frequency of 4‐AP oscillations in two different cells from an RE case.

Finally, as autoimmunity for specific AMPA receptor subunits and NMDA receptors has been implicated in RE, we also examined responses to exogenous application of excitatory amino acids in a number of pyramidal neurons from 4 RE cases (Figure S2). In the presence of TTX (1 μM) and CdCl2 (100 μM) to prevent activation of Na+ and Ca2+ channels, respectively, iontophoretic application of AMPA, kainic acid (KA), or NMDA (Vhold = −70 mV) consistently produced inward currents in pyramidal neurons from RE cases. The average peak amplitude of the AMPA current was −143 ± 49 pA (n = 6), for the KA current it was −274 ± 88 pA (n = 3), and for the NMDA current, −155 ± 21 pA (n = 6). For NMDA currents, changing the holding potential to more depolarized potentials led to an increase in peak current amplitude due to removal of Mg2+ block of NMDA receptor/channels. The maximum currents were observed at ~−20 mV, and the reversal potential occurred at ~+10 mV (not shown). Bath application of AMPA and NMDA was examined in pyramidal neurons from 3 RE cases. The average peak amplitude of the AMPA current was −1182 ± 308 pA (n = 5) and that of the NMDA current was −1301 ± 310 pA (n = 4). For comparison, we were able to test the responses to iontophoretic or bath application of NMDA in a group of non‐RE cases (n = 4). The average peak current amplitude evoked by iontophoretic (−133 ± 19 pA, n = 6) or bath (−1288 ± 478 pA, n = 3) application of NMDA in non‐RE cells was similar to that induced in RE cells (P = 0.45 and P = 0.98, respectively). We also tested the effects of iontophoretic application of AMPA in a small number of pyramidal neurons (n = 4) from 2 non‐RE cases. The amplitude of the responses (‐72 ± 14 pA) was generally smaller than the amplitude of responses from RE cases. This trend did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.28) due to the great variability of responses in cells from RE cases. Based on these observations, we can conclude that AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptors in RE are functional. However, AMPA response amplitude tends to be higher in neurons from RE cases. This, in conjunction with statistically significant increases in average sEPSC amplitude, suggests upregulation of AMPA receptor function in RE.

Western Blots and Immunohistochemistry

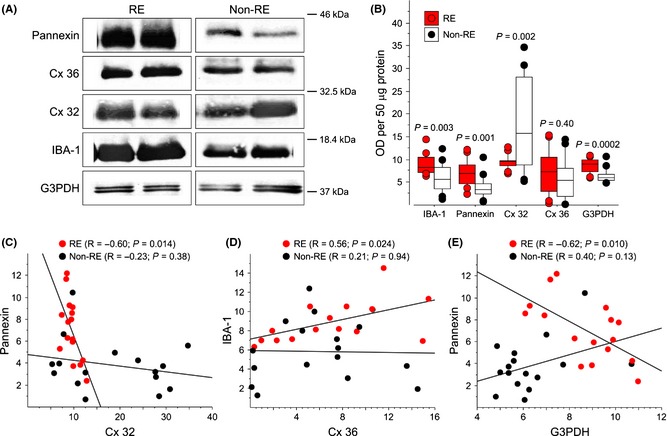

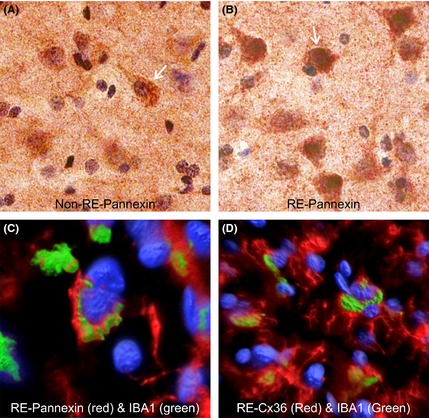

To further determine whether RE cases showed signs of increased gap junction permeability associated with inflammation, we performed Western blots and immunocytochemistry for IBA1 (microglia), pannexin, Cx32, Cx36, and G3PDH as a loading control (Figure 6). Compared with non‐RE cases, brain tissue from RE patients showed increased expression of IBA1, pannexin, and G3PDH, decreased expression of Cx32, and no difference in Cx36 (Figure 6A, B). The increase in pannexin staining was seen within neuronal‐like cell bodies of RE compared with non‐RE cases (Figure 7A,B). Double labeling of pannexin and Cx36 with IBA1 showed areas where these proteins were strongly linked with activated microglia (Figure 7C and D).

Figure 6.

(A) Western blots of IBA1, pannexin, Cx32, Cx36, and G3PDH expression in RE and non‐RE cases. RE patients show an increase in pannexin (45 kDa), IBA1 (17 kDa), and G3PDH (37 kDa) expression. In contrast, there is a decrease in Cx32 (32 kDa) and no change in Cx36 (42 kDa) expression. Box plots (B) and scatterplots (C–E) comparing optical densities for IBA1, pannexin, Cx32, Cx36, and G3PDH for RE and non‐RE cases [axes values represent arbitrary optical densitometry (OD) units multiplied by 105]. Statistical tests provided within each panel. Compared with non‐RE cases, patients with RE had increased protein for IBA1, pannexin, and G3DPH, and decreased protein for Cx32. (C) There was a negative correlation between pannexin and Cx32 for RE, but not for non‐RE cases. (D) There was a positive correlation between IBA1 and Cx36 for RE, but not for non‐RE cases. (E) There was a negative correlation between pannexin and G3PDH for RE, but not for non‐RE cases.

Figure 7.

Immunostaining for pannexin in representative non‐RE (A) and RE (B) cortical specimens, and double labeling for pannexin and IBA1 (C) and Cx36 and IBA1 (D) in RE tissue. (A and B) Staining against pannexin was localized to the cell bodies of pyramidal‐shaped cells and was denser in RE compared with the non‐RE case. (C) Double labeling of pannexin (red) and IBA1 (green; microglia) showed overlap supporting that areas of microglial activation were associated with pannexin expression in RE. Blue fluorescence is from DAPI staining. (D) Double labeling of Cx36 with IBA1 showed similar overlap as with pannexin.

Further analysis showed several positive as well as negative correlations in RE, but not in non‐RE cases (Figure 6C–E). In RE cases, optical densities for pannexin negatively correlated with densities for Cx32 (Figure 6C) and G3PDH (Figure 6E). Furthermore, IBA1 positively correlated with Cx36 (Figure 6D). Similar correlations were not found for non‐RE cases (Figure 6C–E).

Discussion

This study found differences in basic membrane properties of pyramidal neurons, increased dye coupling, signs of cellular hyperexcitability, and increased pannexin expression associated with microglia activation when comparing RE with non‐RE cases. We noted an increase in cell capacitance and lower input resistance that was not due to changes in cell size or dendritic number but more likely due to increased neuronal coupling linked to increased pannexin expression. In addition, microglial IBA1 expression also was linked to increased pannexin hemichannels, which could explain changes in pyramidal neuron membrane properties and possibly hyperexcitability. Blocking hemichannels pharmacologically reduced epileptiform activity induced by 4‐AP, suggesting that novel treatments for RE might include interrupting neuronal electrotonic coupling by changing hemichannel permeability.

The hallmark of RE is the presence of inflammatory processes and highly activated microglia in one hemisphere 31. Mounting evidence suggests that inflammation per se can contribute to development of epileptic seizures 32, 33. Although it is not known whether microglia activation is the cause or consequence of seizures, in a previous study our group showed that greater activation of microglia in RE is not just a consequence of seizure duration or frequency as epileptic patients with CD or tuberous sclerosis complex showed much less microglia activation than RE patients 26. The causes of inflammation and pathology in RE are still unknown. A purely viral or autoimmune etiology seems unlikely, and although it was suggested that several viruses or GluA3 autoantibodies can be toxic, these findings remain controversial 6, 9, 10, 11, 34.

Regardless of the etiology, inflammation is known to cause changes in hemichannel expression and function 35, which in turn could alter interneuronal transmission and favor network synchronization 36. In addition, studies have shown that inflammatory stimuli facilitate opening of glial hemichannels 37 and also can summate to cause opening of Cx and pannexin hemichannels 38. Although pannexins rarely form gap junctions 39, 40, it is possible that in disease conditions where there is inflammation they do. For example, pannexins can be activated by P2X7 receptors, which are involved in inflammation 41. Alternatively, pannexin expression could alter or induce Cx expression and facilitate gap junctional communication. Multiple Cxs are involved in CNS disease 42, and studies have shown that in human CD and temporal lobe epilepsy, Cx expression is altered 43, 44.

The present data demonstrate increased pyramidal neuron coupling and increased pannexin expression associated with microglia activation in RE patients. Both pannexins and Cx can form hemichannels, which in turn can form gap junctions 45. Further, activated microglia can develop the formation of gap junctions 46, and coupling between neuronal and microglial populations through Cx36 gap junctions has been demonstrated 47. Interestingly, a close association between pyramidal neurons and microglia, as well as alignment of microglial rod cells along apical dendrites, has been observed 26. It is tempting to speculate that this close association could facilitate the formation of hemichannels between pyramidal neurons. We also found that MFQ, a Cx channel blocker, reduced 4‐AP oscillations. At present, it is impossible to determine whether this effect was due to Cx or pannexin hemichannel blockade, as in general drugs that block gap junctions formed by Cx also block pannexin channels, for example, carbenoxolone 41. Additional studies using specific pannexin blockers, for example the small peptide inhibitor 10panx, could help sort this out.

Signs of hyperexcitability occurred rarely, but were seen in a number of neurons from RE cases and never in non‐RE cases. These signs consisted of spontaneous paroxysmal‐like discharges or repetitive Na+ and Ca2+ spikes reminiscent of those seen in cytomegalic pyramidal neurons from CD type IIb cases 21. It is possible that the increased cell membrane capacitance of coupled RE pyramidal neurons, as well as a concomitant decrease in input resistance, facilitates the occurrence of these spikes. Hyperexcitability in some RE neurons could be explained by changes in voltage‐gated Na+ or Ca2+ channels. For example, a mutation in SCN1A was observed in one RE case 48. In this study, heterologous expression of the SCN1 mutation in HEK293 cells demonstrated increased persistent Na+ current and channel availability compared with wild‐type channels. Another study using cortical astrocytes from an RE patient demonstrated the occurrence of large spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations 49. Similar oscillations were not observed in normal rat cortical astrocytes. This study highlights possible changes in Ca2+ buffering in RE tissue.

Spontaneous glutamate synaptic activity was increased in RE cases while GABA synaptic activity was similar between RE and non‐RE cases. Interestingly, although the frequency of sEPSCs was increased, the kinetics of averaged synaptic currents, including both rise and decay times, were faster. This probably indicates compensatory mechanisms. We also demonstrated that the average amplitude of sEPSCs was significantly increased in neurons from RE cases. This, in conjunction with a trend for increased amplitude of AMPA currents evoked by iontophoresis in RE pyramidal neurons, supports the idea that AMPA receptors are probably upregulated, which could contribute to hyperexcitability and neuronal vulnerability in RE. Interestingly, it has been reported that binding to glutamate receptors is comparable between RE and patients with partial epilepsy 50. In the present study, we did not observe changes in frequency or kinetics of spontaneous GABAA‐receptor‐mediated synaptic activity. However, an electrophysiological study in dissociated neurons from one RE case suggested the presence of deficits in postsynaptic GABAA receptor function 51.

Increased intrinsic and synaptic excitation could eventually lead to neuronal death in RE. However, it appears that astrocytes, not neurons, are the main target of excitotoxicity in RE 52, 53. ATP and glutamate released via astroglial Cx43 hemichannels lead to neuronal death via activation of pannexin 1 hemichannels 54. We can speculate that increased expression and activation of pannexin hemichannels could contribute, by as yet unknown mechanisms, to neuronal and astrocytic cell death 55. If this is the case, reducing hemichannel expression and permeability could be protective. Indeed, knockout of pannexin 1 protects retinal neurons against ischemic injury 56, and knockout of Cx36 reduces gamma oscillations and epileptic activity induced by 4‐AP 57, 58. Further, during seizure activity, pannexin 1 hemichannels in hippocampal pyramidal neurons are activated by NMDA receptors and blocking these channels reduces epileptiform activity 59.

In conclusion, the present findings underline the importance of using in vitro slice preparations from human tissue to discern possible and selective new therapies in pediatric RE patients. It can be proposed that drugs that reduce gap junction permeability can be used to treat some of the symptoms of RE, as increased electrotonic coupling can lead to cortical hyperexcitability and seizure activity.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1. H&E‐stained sections of resected cerebral tissue from RE subjects (panels A‐C are representative micrographs from one patient, panel D is from another patient). Panel A shows relatively normal/uninvolved neocortex with modest astrocytic proliferation (pia and meninges are at lower right). Panel B shows extensive cystic cavitation throughout much of the cortex (pia and leptomeninges are at right). Panel C shows extensive microvascular proliferation and astrocytic gliosis, but many preserved neurons. Panel D shows extensive perivascular cuffing by mononuclear cells surrounding a parenchymal vessel (arrow).

Figure S2. Iontophoretic (A) or bath (B) application of AMPA or NMDA induced robust inward currents in pyramidal neurons from RE cases. These responses were similar to those induced in neurons from non‐RE cases (not shown).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and their parents for allowing use of resected specimens for experimentation. We also thank the UCLA Hospital Pediatric Neurology staff for their assistance. Fitore Vlashi helped with data analysis and Donna Crandall helped with the illustrations. This study was supported by NIH Grant NS 38992 and in part by the RE Children's Project.

References

- 1. Hart YM, Cortez M, Andermann F, et al. Medical treatment of Rasmussen's syndrome (chronic encephalitis and epilepsy): effect of high‐dose steroids or immunoglobulins in 19 patients. Neurology 1994;44:1030–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Granata T. Rasmussen's syndrome. Neurol Sci 2003;24(Suppl 4):S239–S243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andrews PI, McNamara JO. Rasmussen's encephalitis: an autoimmune disorder? Curr Opin Neurol 1996;9:141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bien CG, Bauer J. T‐cells in human encephalitis. Neuromolecular Med 2005;7:243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oguni H, Andermann F, Rasmussen T. The Natural History of the Syndrome of Chronic Encephalitis and Epilepsy: A Study of the MNI Series of Forty‐eight Cases In: Andermann F, editor. Chronic Encephalitis and Epilepsy Rasmussen's Syndrome. USA: Butterworth‐Heinemann, 1991;7–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Varadkar S, Bien CG, Kruse CA, et al. Rasmussen's encephalitis: clinical features, pathobiology, and treatment advances. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bien CG, Urbach H, Deckert M, et al. Diagnosis and staging of Rasmussen's encephalitis by serial MRI and histopathology. Neurology 2002;58:250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nabbout R. Autoimmune and inflammatory epilepsies. Epilepsia 2012;53(Suppl 4):58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farrell MA, Droogan O, Secor DL, Poukens V, Quinn B, Vinters HV. Chronic encephalitis associated with epilepsy: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Acta Neuropathol 1995;89:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farrell MA, Cheng L, Cornford ME, Grody WW, Vinters HV. Cytomegalovirus and Rasmussen's encephalitis. Lancet 1991;337:1551–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vinters HV, Wang R, Wiley CA. Herpesviruses in chronic encephalitis associated with intractable childhood epilepsy. Hum Pathol 1993;24:871–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rogers SW, Andrews PI, Gahring LC, et al. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluR3 in Rasmussen's encephalitis. Science 1994;265:648–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Takahashi Y, Mori H, Mishina M, et al. Autoantibodies and cell‐mediated autoimmunity to NMDA‐type GluRepsilon2 in patients with Rasmussen's encephalitis and chronic progressive epilepsia partialis continua. Epilepsia 2005;46(Suppl 5):152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. He XP, Patel M, Whitney KD, Janumpalli S, Tenner A, McNamara JO. Glutamate receptor GluR3 antibodies and death of cortical cells. Neuron 1998;20:153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Twyman RE, Gahring LC, Spiess J, Rogers SW. Glutamate receptor antibodies activate a subset of receptors and reveal an agonist binding site. Neuron 1995;14:755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mantegazza R, Bernasconi P, Baggi F, et al. Antibodies against GluR3 peptides are not specific for Rasmussen's encephalitis but are also present in epilepsy patients with severe, early onset disease and intractable seizures. J Neuroimmunol 2002;131:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watson R, Jiang Y, Bermudez I, et al. Absence of antibodies to glutamate receptor type 3 (GluR3) in Rasmussen encephalitis. Neurology 2004;63:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wiendl H, Bien CG, Bernasconi P, et al. GluR3 antibodies: prevalence in focal epilepsy but no specificity for Rasmussen's encephalitis. Neurology 2001;57:1511–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trippe J, Steinke K, Orth A, Faustmann PM, Hollmann M, Haase CG. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor antigens in multiple sclerosis and Rasmussen's encephalitis. NeuroImmunoModulation 2014;21:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harvey AS, Cross JH, Shinnar S, Mathern GW, Taskforce IPESS. Defining the spectrum of international practice in pediatric epilepsy surgery patients. Epilepsia 2008;49:146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cepeda C, Hurst RS, Flores‐Hernandez J, et al. Morphological and electrophysiological characterization of abnormal cell types in pediatric cortical dysplasia. J Neurosci Res 2003;72:472–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blumcke I, Thom M, Aronica E, et al. The clinicopathologic spectrum of focal cortical dysplasias: a consensus classification proposed by an ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Diagnostic Methods Commission. Epilepsia 2011;52:158–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cepeda C, Andre VM, Levine MS, et al. Epileptogenesis in pediatric cortical dysplasia: the dysmature cerebral developmental hypothesis. Epilepsy Behav 2006;9:219–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hemb M, Velasco TR, Parnes MS, et al. Improved outcomes in pediatric epilepsy surgery: the UCLA experience, 1986‐2008. Neurology 2010;74:1768–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salamon N, Kung J, Shaw SJ, et al. FDG‐PET/MRI coregistration improves detection of cortical dysplasia in patients with epilepsy. Neurology 2008;71:1594–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wirenfeldt M, Clare R, Tung S, Bottini A, Mathern GW, Vinters HV. Increased activation of Iba1 + microglia in pediatric epilepsy patients with Rasmussen's encephalitis compared with cortical dysplasia and tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurobiol Dis 2009;34:432–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cepeda C, Walsh JP, Peacock W, Buchwald NA, Levine MS. Dye‐coupling in human neocortical tissue resected from children with intractable epilepsy. Cereb Cortex 1993;3:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Avoli M, Mattia D, Olivier A. A window on the physiopathogenesis of seizures in patients with cortical dysplasia. Adv Exp Med Biol 2002;497:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mattia D, Olivier A, Avoli M. Seizure‐like discharges recorded in human dysplastic neocortex maintained in vitro . Neurology 1995;45:1391–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gigout S, Louvel J, Kawasaki H, et al. Effects of gap junction blockers on human neocortical synchronization. Neurobiol Dis 2006;22:496–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Devinsky O, Vezzani A, Najjar S, De Lanerolle NC, Rogawski MA. Glia and epilepsy: excitability and inflammation. Trends Neurosci 2013;36:174–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aronica E, Crino PB. Inflammation in epilepsy: clinical observations. Epilepsia 2011;52(Suppl 3):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vezzani A, Friedman A, Dingledine RJ. The role of inflammation in epileptogenesis. Neuropharmacology 2013;69:16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Levite M, Fleidervish IA, Schwarz A, Pelled D, Futerman AH. Autoantibodies to the glutamate receptor kill neurons via activation of the receptor ion channel. J Autoimmun 1999;13:61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kielian T. Glial connexins and gap junctions in CNS inflammation and disease. J Neurochem 2008;106:1000–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carlen PL. Curious and contradictory roles of glial connexins and pannexins in epilepsy. Brain Res 2012;1487:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Retamal MA, Froger N, Palacios‐Prado N, et al. Cx43 hemichannels and gap junction channels in astrocytes are regulated oppositely by proinflammatory cytokines released from activated microglia. J Neurosci 2007;27:13781–13792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bennett MV, Garre JM, Orellana JA, Bukauskas FF, Nedergaard M, Saez JC. Connexin and pannexin hemichannels in inflammatory responses of glia and neurons. Brain Res 2012;1487:3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ma W, Hui H, Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Pharmacological characterization of pannexin‐1 currents expressed in mammalian cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009;328:409–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. MacVicar BA, Thompson RJ. Non‐junction functions of pannexin‐1 channels. Trends Neurosci 2010;33:93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dahl G, Harris AL. Pannexins or Connexins? In: Harris AL, Locke D, editors. Connexins: A Guide. New York, USA: Humana Press, 2009;287–301. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Eugenin EA, Basilio D, Saez JC, et al. The role of gap junction channels during physiologic and pathologic conditions of the human central nervous system. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2012;7:499–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Collignon F, Wetjen NM, Cohen‐Gadol AA, et al. Altered expression of connexin subtypes in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy in humans. J Neurosurg 2006;105:77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Garbelli R, Frassoni C, Condorelli DF, et al. Expression of connexin 43 in the human epileptic and drug‐resistant cerebral cortex. Neurology 2011;76:895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shestopalov VI, Panchin Y. Pannexins and gap junction protein diversity. Cell Mol Life Sci 2008;65:376–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eugenin EA, Eckardt D, Theis M, Willecke K, Bennett MV, Saez JC. Microglia at brain stab wounds express connexin 43 and in vitro form functional gap junctions after treatment with interferon‐gamma and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:4190–4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dobrenis K, Chang HY, Pina‐Benabou MH, et al. Human and mouse microglia express connexin36, and functional gap junctions are formed between rodent microglia and neurons. J Neurosci Res 2005;82:306–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ohmori I, Ouchida M, Kobayashi K, et al. Rasmussen encephalitis associated with SCN 1 A mutation. Epilepsia 2008;49:521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Manning TJ Jr, Sontheimer H. Spontaneous intracellular calcium oscillations in cortical astrocytes from a patient with intractable childhood epilepsy (Rasmussen's encephalitis). Glia 1997;21:332–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bernasconi P, Cipelletti B, Passerini L, et al. Similar binding to glutamate receptors by Rasmussen and partial epilepsy patients’ sera. Neurology 2002;59:1998–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gibbs JW 3rd, Morton LD, Amaker B, Ward JD, Holloway KL, Coulter DA. Physiological analysis of Rasmussen's encephalitis: patch clamp recordings of altered inhibitory neurotransmitter function in resected frontal cortical tissue. Epilepsy Res 1998;31:13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Whitney KD, McNamara JO. GluR3 autoantibodies destroy neural cells in a complement‐dependent manner modulated by complement regulatory proteins. J Neurosci 2000;20:7307–7316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bauer J, Elger CE, Hans VH, et al. Astrocytes are a specific immunological target in Rasmussen's encephalitis. Ann Neurol 2007;62:67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Orellana JA, Froger N, Ezan P, et al. ATP and glutamate released via astroglial connexin 43 hemichannels mediate neuronal death through activation of pannexin 1 hemichannels. J Neurochem 2011;118:826–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Thompson RJ, Macvicar BA. Connexin and pannexin hemichannels of neurons and astrocytes. Channels (Austin) 2008;2:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dvoriantchikova G, Ivanov D, Barakat D, et al. Genetic ablation of Pannexin1 protects retinal neurons from ischemic injury. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e31991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hormuzdi SG, Pais I, LeBeau FE, et al. Impaired electrical signaling disrupts gamma frequency oscillations in connexin 36‐deficient mice. Neuron 2001;31:487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maier N, Guldenagel M, Sohl G, Siegmund H, Willecke K, Draguhn A. Reduction of high‐frequency network oscillations (ripples) and pathological network discharges in hippocampal slices from connexin 36‐deficient mice. J Physiol 2002;541:521–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thompson RJ, Jackson MF, Olah ME, et al. Activation of pannexin‐1 hemichannels augments aberrant bursting in the hippocampus. Science 2008;322:1555–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. H&E‐stained sections of resected cerebral tissue from RE subjects (panels A‐C are representative micrographs from one patient, panel D is from another patient). Panel A shows relatively normal/uninvolved neocortex with modest astrocytic proliferation (pia and meninges are at lower right). Panel B shows extensive cystic cavitation throughout much of the cortex (pia and leptomeninges are at right). Panel C shows extensive microvascular proliferation and astrocytic gliosis, but many preserved neurons. Panel D shows extensive perivascular cuffing by mononuclear cells surrounding a parenchymal vessel (arrow).

Figure S2. Iontophoretic (A) or bath (B) application of AMPA or NMDA induced robust inward currents in pyramidal neurons from RE cases. These responses were similar to those induced in neurons from non‐RE cases (not shown).