Abstract

Purpose

We investigated how treatment-induced neuropathic symptoms are associated with patients’ quality of life (QOL) and clinician-reported difficulty in caring for patients.

Methods

Data were obtained from 3106 outpatients with colorectal, breast, lung, or prostate cancer on numbness/tingling (N/T), neuropathic pain, and QOL. Clinicians reported the degree of difficulty in caring for patients’ physical and psychological symptoms.

Results

For all patients, moderate to severe N/T was associated with poor QOL (OR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.47–2.26, P < 0.001) but neuropathic pain was not (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 0.94–1.83, P = 0.114). Moderate to severe N/T and neuropathic pain were associated with increased care difficulty (OR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.27–1.74, P < 0.001 for N/T, and OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.15–1.84, P = 0.002 for neuropathic pain). The association of neuropathic pain with care difficulty was most significant in patients with CRC (OR = 2.32, 95% CI: 1.41–3.83, P = 0.001). Baseline neuropathic pain was associated with declining QOL in CRC patients (OR = 2.08, 95% CI: 2.21–3.58, P = 0.008).

Conclusions

Clinicians may experience increased care difficulty for patients of all cancer types with moderate to severe N/T or neuropathic pain; care difficulty due to neuropathic pain may be higher for CRC patients. Nearly half the patients of all cancer types with moderate to severe N/T may expect poor short-term QOL; CRC- but not other- patients with baseline neuropathic pain are likely to experience declining QOL.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

About half of patients with moderate to severe N/T (any cancer type) may expect poor QOL in the short-term; CRC patients with baseline neuropathic pain in particular may experience declining QOL.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, neuropathy, neuropathic pain, numbness/tingling, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

With 142,000 reported new cases in 2013, colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the most common solid tumor types in the United States [1], and is the third most common cause of cancer in the Western nations [1]. Advancements in therapies have increased the duration of post-diagnosis survivorship; however, patients frequently live with the long-term adverse effects emergent both from the cancer itself, and from its treatment. The chemotherapeutic agent, oxaliplatin, in combination with fluorouracil or an oral analog is currently the treatment of choice for adjuvant treatment of patients with node-positive CRC [2,3]. Several studies indicate that oxaliplatin, despite its efficacy, is highly toxic to the peripheral nervous system and may cause neurotoxicity in up to 50% of patients [4,5]. Oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy is primarily sensory in nature and may be related to a dose-dependent accumulation of platinum compounds in the dorsal root ganglia causing neuronal atrophy and apoptosis [6]. Oxaliplatin can cause the development of both acute and chronic neuropathy, which may frequently be dose-limiting and may compromise patients’ quality of life [7–9]. In the initial cohort of the landmark Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin/5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin (MOSAIC) for the adjuvant treatment of colon cancer, a 92% incidence of acute and chronic neurosensory symptoms was reported in patients receiving oxaliplatin; at 6 months follow-up, 41% of patients continued to report some degree of neurosensory symptoms with nearly 30% and 25% reporting persistent symptoms at 12 and 18 months, respectively [2]. It is critical to note however that the measured prevalence of neuropathic pain and N/T symptoms may vary significantly between studies due to variability in measurement instruments, limitations of current grading scales, and the absence of a consensus on the gold standard for symptom assessment [10], the type of chemotherapy and its cumulative received dose [11].

Patients with cancers such as breast, lung, or prostate who are treated with other platinum-containing drugs (taxanes, for example) are similarly exposed to the risk of potential sensory neurotoxicity [12,13]. In a recent study regarding the impact of taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy on the treatment delivery, 50 out of 488 women with non-metastatic breast cancer receiving paclitaxel or docetaxel experienced a total of 56 dose-modification events (dose delay, dose reduction or treatment discontinuation) attributed to chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), and accounted for more than one-third (37.3%) of the dose-modification decisions [13]. These data indicate a substantial risk of clinically important CIPN. The impact of receiving less cumulative chemotherapy than planned has not yet been quantified. Additionally, patients may experience non-cancer therapy related causes of peripheral neuropathy from co-morbid conditions, ancillary medications, or from the malignancy itself which could interfere with receipt of anti-cancer treatment.

The treatment delivery-related problems outlined above, coupled with patients’ neuropathic symptoms and the potential for a diminished quality of life raise complex difficulties and challenges for clinicians and patients alike in cancer treatment and symptom management. Our parent study which evaluated data (unpublished) from a large multi-center trial of 3106 medical oncology outpatients concluded that patients with CRC experience significantly higher rates of numbness/tingling (N/T) but comparable neuropathic pain relative to patients with other cancers [14]. It further concluded that the risk factors predisposing patients to worse neuropathic outcomes include: having CRC (vs. another cancer type), longer duration of cancer, prior therapy, being on current therapy, and being older, or of African-American origin.

In the current analysis using the same multi-center trial, we sought to further examine how neuropathic symptoms are associated with patients’ quality of life (QOL) and clinicians’ perceived difficulty in caring for cancer patients. While previous studies have characterized QOL outcomes and treatment-related challenges in patients with CRC [9,10], few studies have been conducted in other cancer types, and it is not known yet whether the association of neuropathic symptoms with patients’ self-assessment of QOL varies by disease site. Similarly, few studies have investigated the impact of treatment-induced neuropathy on the oncologist’s experience of difficulty in caring for patients, and whether this impact varies by cancer type. Answers to these questions are critical not only with respect to the experience clinicians and patients may anticipate from neuropathy-inducing treatment, but also with respect to the management of sensory neuropathy of any etiology. The specific objectives of the current study were to analyze: 1) how N/T and neuropathic pain are associated with patients’ QOL at the study’s initial assessment, and change in QOL between initial and follow-up assessments for patients of all cancer types; 2) whether presence of N/T and neuropathic pain at the initial assessment are associated with increased clinician difficulty in caring for patients, and 3) whether the association of N/T and neuropathic pain with patients’ QOL and clinicians’ perceived difficulty in caring for patients varies by disease site (CRC vs. other cancers). Additionally, we also characterized trends for the treatment of nerve pain for all patients by cancer type and severity of neuropathic symptoms.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study sample

From March 3, 2006 to May 19, 2008, outpatients with any stage colorectal, breast, lung, or prostate cancer and at any point in their cancer trajectory were enrolled from Eastern Oncology Cooperative Group (ECOG)-affiliated institutions, including 6 academic centers and 32 community clinics. All patients were enrolled in Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns (SOAPP), a multi-center study of disease and treatment related symptoms experienced by cancer patients being followed on an outpatient basis (www.ecogsoapp.org). The current study is a secondary analysis derived from the SOAPP data. Eligible patients were 18 years or older, recipients of care at an ECOG-affiliated institution, willing to complete the follow-up survey, and cognitively competent to complete surveys. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating institution. All participants provided written informed consent.

Patients were recruited when they checked in for their clinic appointments, and completed the required assessments at the initial visit and at a follow-up visit 28–35 days later. Patients reported all items according to their experience during the preceding 24 hours. Reasons for incomplete forms were documented on an Assessment Compliance Form. Patients who were too ill to complete the follow-up questionnaire were given the option to mail the forms to the treating clinic by day 42 after the initial visit.

Assessments

N/T and Neuropathic Pain

Symptom data on patient-reported N/T were obtained using the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) [15], a widely used valid and reliable instrument, and have been presented in a report on the parent study (unpublished data; under review) [14]. Symptoms were rated “at their worst” in the previous 24 hours on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 representing “not present” and 10 representing “as bad as you can imagine.” The parent study also presents data on clinician-reported “mechanism of pain.” This question is part of the Revised Edmonton Staging System [16] for classifying cancer pain and required the clinician to assess patients’ type of pain from among 4 choices: 1) no pain syndrome, 2) any nociceptive combination of visceral and/or bone or soft tissue pain, 3) neuropathic pain syndrome with or without any combination of nociceptive pain, and 4) insufficient information to classify. The above data, derived from our previous analyses (unpublished) [14], were utilized for the current study.

QOL

Patients reported their overall QOL at the initial assessment by responding to a global QOL question: In general, would you say your overall quality of life is: 1 = Excellent, 2 = Good, 3 = Fair, 4 = Poor, 5 = Very poor? At the follow-up assessment, patients reported the change in their QOL by responding to another global item: Compared to your previous visit, would you say your overall quality of life is: 1 = Much better, 2 = Better, 3 = Nearly the same, 4 = Worse, 5 = Much worse?

Difficulty in caring for patients

At the initial assessment, clinicians reported how they would categorize the degree of difficulty in caring for each patient’s physical/psychological symptoms relative to other patients with the same stage of disease using a 5-point scale: 1 = Very difficult, 2 = Difficult, 3 = Average, 4 = Easier than average, 5 = Much easier than average.

Treatment for Nerve Pain and Other variables

Information about prescription of medications for nerve pain was collected via the Medication Form at the initial visit. Data on patient demographics and other clinical characteristics such as ECOG performance status, disease stage and status, previous treatment(s), etc. were collected at the initial assessment.

Statistical Analysis

Patient-reported N/T was considered moderate to severe at a score of ≥5 on the MDASI [17]. Chi square test was used for significance test of association between categorical and binary variables. Ordinal logistic models were constructed to examine how N/T and neuropathic pain were associated with patients’ QOL at the initial assessment (dependent variable coded as: good/excellent=0, fair=1, poor/very poor=2) and its change between the initial and follow-up assessments (dependent variable coded as: much better/better=0, nearly the same=1, worse/much worse=2) after adjusting for relevant covariates. Ordinal logistic models were also fit to examine whether the presence of N/T and neuropathic pain at the initial assessment were associated with increased difficulty in caring for patients (dependent variable coded as: much easier/easier=0, average=1, difficult/very difficult=2) after adjusting for other covariates. Interaction between disease site, N/T and neuropathic pain was tested via the likelihood ratio test to examine whether the association of N/T and neuropathic pain on QOL and difficulty in caring for patients varies by disease site. In addition to the key independent variables (ie, N/T, neuropathic pain disease site), a set of 14 variables were included as covariates in these models as they were considered potentially associated with the dependent variables based on previous studies or biological knowledge (age, years since diagnosis, race/ethnicity, disease status, advanced disease, ECOG performance status, weight loss in the past 6 months, prior systemic treatment, prior radiotherapy, current treatment, any counseling service, any support group, and current medications). For QOL change regression, baseline QOL level was also included as a covariate. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was used to check multicollinearity among these variables and the largest VIF value was <3. A separate category for missing data was generated for categorical covariates if the proportion of data missing was no less than 5 percent. Patients with missing data on covariates were excluded from the logistic models. Clustered sandwich estimators of standard errors were used in the logistic models to account for the clustering effect of institutions.

No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. All reported P-values are two-sided and were considered significant if lower than 0.05. STATA 11•2 software was used for all data analysis [18].

RESULTS

Three thousand one hundred six patients were enrolled in the study (718 with CRC; 1544 with breast cancer; 320 with prostate cancer, and 524 with lung cancer). Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients (n=3106)

| Variables | Colorectal (n=718) | Others (n=2388) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| No. of patients | % | No. of patients | % | ||

| Age at study entry (mean, sd) | 61.6 (12.7) | 61.1 (12.3) | 0.372 | ||

| Years since diagnosis (mean, sd) | 1.9 (2.2) | 3.3 (4.5) | <0.001 | ||

| Race | 0.184 | ||||

| White | 599 | 84.3 | 2049 | 86.9 | |

| Black | 98 | 13.8 | 266 | 11.3 | |

| Others | 14 | 2.0 | 43 | 1.8 | |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 583 | 81.2 | 1989 | 83.3 | |

| Hispanic | 93 | 13.0 | 192 | 8.0 | |

| Unknown | 42 | 5.9 | 207 | 8.7 | |

| Disease status | 0.038 | ||||

| CR | 243 | 34.0 | 914 | 38.5 | |

| PR | 28 | 3.9 | 119 | 5.0 | |

| SD | 324 | 45.4 | 1012 | 42.7 | |

| PD | 119 | 16.7 | 327 | 13.8 | |

| Disease stage | <0.001 | ||||

| Non-advanced | 377 | 52.7 | 1544 | 64.9 | |

| Advanced | 339 | 47.4 | 835 | 35.1 | |

| ECOG PS | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 375 | 52.3 | 1380 | 58.1 | |

| 1 | 299 | 41.7 | 806 | 34.0 | |

| 2–4 | 43 | 6.0 | 188 | 7.9 | |

| Weight loss in the prior 6 months | <0.001 | ||||

| <5 | 565 | 79.4 | 2066 | 87.6 | |

| >=5% | 147 | 20.7 | 292 | 12.4 | |

| Prior systemic therapy | 0.122 | ||||

| No | 294 | 41.0 | 901 | 37.8 | |

| Yes | 424 | 59.1 | 1486 | 62.3 | |

| Prior radiation therapy | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 550 | 77.1 | 1232 | 52.1 | |

| Yes | 163 | 22.9 | 1134 | 47.9 | |

| Currently receiving any cancer therapy | 0.110 | ||||

| No | 203 | 28.3 | 604 | 25.3 | |

| Yes | 515 | 71.7 | 1784 | 74.7 | |

| Any individual counseling service | 0.655 | ||||

| No | 649 | 90.8 | 2146 | 90.2 | |

| Yes | 66 | 9.2 | 233 | 9.8 | |

| Participate in any support group | 0.162 | ||||

| No | 676 | 94.6 | 2214 | 93.1 | |

| Yes | 39 | 5.5 | 165 | 6.9 | |

| # of medicines currently taken | 0.002 | ||||

| 0–4 | 242 | 33.7 | 658 | 27.6 | |

| 5–9 | 268 | 37.3 | 940 | 39.4 | |

| >=10 | 131 | 18.3 | 556 | 23.3 | |

| Unknown | 77 | 10.7 | 234 | 9.8 | |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, CR: complete response, PR: partial response, SD: stable disease, PD: progressive disease

In the overall sample, the mean score for N/T was 2.0 (SD=2.8) with a median score of 1 (Q1:0 and Q3: 3), 19.1% of patients had moderate to severe N/T, and 9.2% of patients had neuropathic pain. Previous analyses from these data (unpublished) have indicated that moderate to severe N/T was higher in patients with CRC relative to other cancer types (25.8% vs. 17.1%, P < 0.001); 25% versus 10.5% of clinicians rated N/T as a top 3 symptom for patients with CRC relative to other cancers (P <.001), and that the prevalence of neuropathic pain was comparable between patients with CRC and other cancers (8.7% vs. 9.3%, P = 0.654) [14].

Association of N/T and Neuropathic Pain with Patients’ QOL at the Initial Assessment

Figure 1A displays patients’ QOL status by N/T and neuropathic pain in all patients. Patients with moderate to severe N/T had significantly higher proportion of reporting poor QOL compared to patients with less severe N/T (10% vs. 5% and P<0.001). The proportion of poor QOL was not different by presence or lack of neuropathic pain (7% vs. 6% and P=0.658). The multivariable regression analysis showed similar results after adjusting for other covariates (Table 2). Patients with moderate to severe N/T had an 82% increase in the odds of having poor QOL compared to patients with no/mild N/T (OR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.47–2.26, P < 0.001), and patients with neuropathic pain had a 31% increase in the odds of having poor QOL compared to patients without neuropathic pain, but it did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 0.94–1.83, P = 0.114). Interaction test showed no significant difference in the association of neuropathic symptoms with QOL by disease site (P values >0.05 for both N/T-by-disease site interaction and neuropathic pain-by-disease site interaction).

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Distribution of QOL by Severity of N/T and Presence of Neuropathic Pain at the Initial Assessment

Figure 1B. QOL Change by Presence of Neuropathic Pain at the Initial Assessment by Disease Site

Figure 1C. Distribution of Difficulty in Caring for Patients by Severity of N/T and Presence of Neuropathic Pain at the Initial Assessment

Table 2.

Ordinal Logistic Regression for Association of N/T and Neuropathic Pain with Difficulty Caring for Patients and QOL at the Initial Assessment

| Variables | Difficulty in caring patients

|

QOL

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | ||||

| Numbness/tingling | 5–10 v 0–4 | 1.49 | 1.27 | 1.74 | <0.001 | 1.82 | 1.47 | 2.26 | <0.001 |

| Neuropathic pain | Yes v No | 1.46 | 1.15 | 1.84 | 0.002 | 1.31 | 0.94 | 1.83 | 0.114 |

| Disease site | Colorectal vs. others | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.91 | 0.007 | 1.11 | 0.84 | 1.46 | 0.463 |

| Age | Years, continuous | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.004 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.003 |

| Years since diagnosis | Continuous | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.01 | 0.206 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 0.448 |

| Race | |||||||||

| Black v White | 1.15 | 0.82 | 1.60 | 0.427 | 1.21 | 0.92 | 1.61 | 0.176 | |

| Other v White | 1.62 | 0.61 | 4.28 | 0.334 | 1.49 | 0.67 | 3.29 | 0.325 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hispanic v Non-Hisp | 1.99 | 1.47 | 2.69 | <0.001 | 2.70 | 1.74 | 4.20 | <0.001 | |

| Unknown v Non-Hisp | 1.55 | 1.26 | 1.91 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 0.79 | 1.44 | 0.683 | |

| Disease status | |||||||||

| PR v CR | 1.68 | 1.11 | 2.54 | 0.015 | 1.59 | 0.96 | 2.65 | 0.073 | |

| SD v CR | 1.47 | 1.15 | 1.87 | 0.002 | 1.79 | 1.29 | 2.50 | 0.001 | |

| PD v CR | 1.92 | 1.39 | 2.66 | <0.001 | 1.98 | 1.28 | 3.05 | 0.002 | |

| Advanced disease | Yes v No | 1.07 | 0.88 | 1.30 | 0.511 | 1.01 | 0.74 | 1.37 | 0.964 |

| ECOG PS | |||||||||

| 1 v 0 | 1.60 | 1.28 | 2.00 | <0.001 | 2.42 | 1.87 | 3.14 | <0.001 | |

| 2–4 v 0 | 3.64 | 2.42 | 5.45 | <0.001 | 4.49 | 3.17 | 6.37 | <0.001 | |

| Weight loss | >5% v <=5% | 1.09 | 0.88 | 1.34 | 0.430 | 1.35 | 1.06 | 1.71 | 0.014 |

| Prior systemic treatment | Yes v No | 0.84 | 0.68 | 1.04 | 0.112 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 1.18 | 0.672 |

| Prior radiotherapy | Yes v No | 1.15 | 0.96 | 1.38 | 0.133 | 1.06 | 0.86 | 1.31 | 0.603 |

| Current treatment | Yes v No | 0.91 | 0.75 | 1.11 | 0.348 | 0.96 | 0.75 | 1.22 | 0.721 |

| Any counseling service | Yes v No | 1.51 | 1.11 | 2.05 | 0.008 | 1.37 | 1.04 | 1.81 | 0.026 |

| Any support group | Yes v No | 0.99 | 0.70 | 1.38 | 0.935 | 0.76 | 0.50 | 1.17 | 0.215 |

| Medicine currently taken | |||||||||

| 5–9 v 0–4 | 1.32 | 1.03 | 1.69 | 0.027 | 1.46 | 1.13 | 1.90 | 0.004 | |

| >=10 v 0–4 | 1.78 | 1.32 | 2.41 | <0.001 | 1.99 | 1.57 | 2.51 | <0.001 | |

| Unknown v 0–4 | 1.32 | 0.93 | 1.86 | 0.123 | 1.29 | 0.91 | 1.83 | 0.156 | |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, CR: complete response, PR: partial response, SD: stable disease, PD: progressive disease

While patients with CRC were more likely to experience worse QOL, this association did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 0.84–1.46; P = 0.463, Table 2). However, statistically significant variables associated with poor QOL included younger age, Hispanic ethnicity, having stable or progressive disease (relative to complete remission), having an ECOG performance status worse than 0, having > 5% weight loss in the last 6 months, being on a higher number of concurrent medications, and receiving counseling service.

Association of N/T and Neuropathic Pain with Change in Patients’ QOL between the Initial and Follow-up Assessments

No statistically significant association emerged between levels of N/T at the initial assessment and QOL change between patients’ initial and follow-up visits for all patients and by disease site (data not shown). Baseline neuropathic pain was significantly associated with declining QOL in CRC patients (OR = 2.08, 95% CI: 2.21–3.58, P = 0.008), but not in patients with other cancers (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 0.77–1.59, P > 0.05). Twenty five percent of CRC patients who had neuropathic pain at the initial assessment reported worsened QOL at follow-up. Among CRC patients who reported no neuropathic pain at the initial assessment, 11.5% reported declining QOL at follow-up (P = 0.005, Figure 1B).

Association of N/T and Neuropathic Pain with Difficulty in Caring for Patients at the Initial Assessment

Figure 1C displays the distribution of difficulty in caring for patients by N/T and neuropathic pain in all patients. About 17% of patients with moderate to severe N/T were reported by their clinicians to be more difficult to take care of relative to average patients; this percentage was 8.2 for patients with less severe N/T (P < 0.001). With regard to neuropathic pain, about 16% and 10% of patients with or without neuropathic pain were reported by their clinicians to be more difficult to take care of relative to average patients (P=0.002). These significant associations remained in the multivariable regression models after adjusting for other covariates (OR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.27–1.74, P < 0.001 for N/T, and OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.15–1.84, P = 0.002 for neuropathic pain, Table 2). Interaction test showed that the association of neuropathic pain with difficulty in caring for patients is most significant in CRC patients (OR = 2.32, 95% CI: 1.41–3.83, P = 0.001) and less so in patients with other cancers (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 0.90–1.74, P = 0.174); while the association of N/T on care difficulty did not vary by disease site.

Overall, CRC was significantly associated with decreased difficulty in caring for patients (OR =0.72, 95% CI: 0.57–0.91, P = 0.007, Table 2). Other statistically significant factors associated with increased difficulty in caring for patients included: younger age, Hispanic ethnicity, disease status (being in partial remission or in stable or progressive disease vs. in complete remission), having an ECOG performance status worse than 0, being on a higher number of concurrent medications, and receiving counseling service.

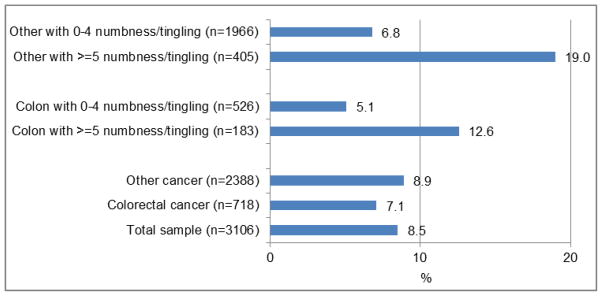

Treatment Patterns for Nerve Pain

The percentage of patients who were prescribed some type of treatment for nerve pain at the initial assessment is shown in Figure 2 by cancer type (CRC versus others) and by severity of N/T. From among all patients (n = 3106), 264 or 8.5% were prescribed some type of therapy for nerve pain at the initial assessment (nerve block referral for 2 patients, anticonvulsive treatment for 198 for patients, antidepressant treatment for 17 patients, and topical therapy for 58 patients; data not shown). There was a marginally significant difference in the percentage of nerve pain prescriptions dispensed for patients with CRC versus other cancers for moderate to severe N/T (12.6% vs. 19.0%, P = 0.054; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of Patients Prescribed Some Type of Treatment for Nerve Pain at the Initial Assessments (all patients) by Cancer Type and Severity of N/T

DISCUSSION

Our previous analysis of the SOAPP database (unpublished data) indicated that moderate to severe N/T was significantly higher in patients with CRC relative to other cancers, and that a significantly higher percentage of clinicians rated N/T as a top 3 symptom for patients with CRC relative to other cancers[14]. More patients with CRC are living with both the short- and long-term adverse effects of this cancer as well as its treatment [9,10] especially with oxaliplatin, which most likely accounts for the majority of neuropathy in these patients. Clinicians’ management of the cancer can be challenged by need for dose modifications [13] and managing difficult neuropathic symptoms. In the current analysis, we evaluated how treatment-induced neuropathic symptoms are associated with patients’ quality of life (QOL) and clinician-reported difficulty in caring for patients with different cancer types.

Our data indicate that at the initial assessment, moderate to severe N/T was significantly associated with poor QOL for patients of all cancer types but neuropathic pain was not (after adjusting for relevant covariates), and there was no significant difference in the effect of neuropathic symptoms (either N/T or neuropathic pain) on QOL by disease site. However, baseline neuropathic pain was associated with more than twice the odds of significantly declining QOL in CRC patients but not in those with other cancer types. While comparison data on QOL outcomes (CRC vs. other cancers) is not available, literature in general supports that patients with CRC, and particularly those treated with oxaliplatin, may be prone to especially deleterious effects on their QOL such as reduced sleep quality, increased depressive symptoms, poor performance status, cytopenias, and peripheral neuropathy [6–10]. In the current study, 25% of CRC patients with neuropathic pain at the initial assessment reported significantly worse QOL at follow-up, and nearly 12% of those with no neuropathic pain at baseline reported the same. Our data thus indicate that CRC patients with baseline neuropathic pain, but not other patient types, are likely to experience declining QOL. As 59% of the CRC patients had received prior systemic therapy, including possibly oxaliplatin before their initial assessment, it is conceivable that some of these patients may have experienced progression of their neuropathic symptoms during the interval between assessments.

Across all patient types, our results indicated that moderate to severe N/T and presence of neuropathic pain was associated with significantly increased clinician-reported difficulty in caring for patients’ physical and psychological symptoms. The impact of neuropathic pain, presumably due to anti-cancer therapy, was most significant for clinicians when caring for patients with CRC. In addition to oxaliplatin, neuropathic symptoms occur with other malignancies and anti-cancer therapies, requiring clinician attention (7,8). In a recent study on the impact of CIPN on treatment delivery, 50 out of 488 women with non-metastatic breast cancer receiving paclitaxel or docetaxel experienced a total of 56 dose-modification events attributable to CIPN, and accounted for more than one-third of the dose-modification decisions [13]. These data indicate a substantial risk of clinically important CIPN in conditions other than CRC. Recent studies indicate that paclitaxel may result in an acute form of neuropathy similar to oxaliplatin [11,12,19], although oxaliplatin neurotoxicity appears to be more prevalent than that seen with other agents. Perhaps our CRC patients also had higher rates of co-morbid conditions or additional medications that predisposed them to neuropathy compared to others. Notwithstanding the influence of neuropathic pain as a unique variable on clinician-reported care difficulty, it is interesting to note that overall, data indicated that CRC was associated with less care difficulty relative to other cancers, although certain patient characteristics such as younger age, Hispanic ethnicity, and disease status (partial remission and stable/progressive disease vs. complete remission) were significantly associated with increased care difficulty. Perhaps these subpopulations had higher rates of neuropathy symptoms. We are unable to compare this result with existing literature as to our knowledge, there is no previous data on neuropathy-related relative care difficulty between different cancer types.

With respect to treatment patterns for nerve pain, our data indicated that there was a marginally significant difference in the percentage of nerve pain prescriptions dispensed for patients with CRC relative to other cancers for moderate to severe N/T, with a lower overall percentage of prescriptions for patients with CRC compared to other cancers. We were unable to find literature on comparative nerve pain prescription levels for moderate to severe N/T between CRC and other cancers. Very few patients in our database received prescriptions for neuropathy; this may most likely be related to lack of FDA-approved medications for CIPN. Gabapentin, pregabalin [20] and duloxetine [21] have been approved for painful diabetic neuropathy, and duloxetine was found in one study to statistically improve neuropathic pain in patients with CIPN [21]. Several pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions are presently being researched.

This study had several limitations. It sought to investigate only a subjective and global comparison of patients’ own assessment of QOL and clinicians’ perceptions of the relative difficulty in caring for patients with CRC and other cancers. Thus, rather than a standard or lengthy QOL questionnaire (such as the EORTC QLQ), it utilized only a single QOL item to assess patients’ self-perception of their QOL at the initial and follow-up visits. The change in QOL assessed at the 1-month follow-up required patients to recall their QOL experience at the initial assessment, and then assess and report perceived change. The methodological limitations of such a measure may include significant reporting bias and some reduction in the reliability and validity of our findings. Additional limitations include the utilization of a measure for N/T that may not have captured patients’ typical experience (as it required the reporting of their worst symptomatology in the last 24 hours prior to assessment), as well as the use of clinician-rated measure of neuropathic pain, which may be subject to some error, given that pain is a subjective experience. Notwithstanding these limitations, results from this large, prospective, multicenter study provide a view of the subjective patient experience and clinician-perceived difficulty in patient-care across different cancer types, and may thus, to a large extent, be generalizable. Our data with respect to clinicians’ management of nerve pain similarly provide simply an overview of treatment patterns for all patients by cancer type and severity of neuropathic symptoms. Another limitation of our analyses is that the SOAPP study was not specifically designed for the investigation of neuropathic symptoms in CRC patients as a primary outcome. Thus, detailed information on specific chemotherapeutic regimens was not collected in our study; however, we presume that after the publication of the MOSAIC trial [2], and the standard adoption of the FOLFOX regimen by practitioners, most CRC patients in our study would have been exposed to oxaliplatin, although receipt of oxaliplatin would be dependent on patients’ tumor status at the initial assessment, and whether they were diagnosed before the approval of this drug. Finally, our study evaluated patients only twice: at the initial visit and at a follow-up visit 28–35 days later; future studies of longer duration are required to gain greater insight particularly into the patients’ QOL experience.

Treatment and prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced as well as other types of peripheral neuropathy remains difficult [6,22–24], As we have demonstrated here, identifying patients with neuropathy symptoms and less than good QOL, and the clinicians who are challenged by treating peripheral neuropathy, is critical to develop appropriate education and management strategies for both clinicians and patients. Results from our data lead to some key assumptions and hypotheses. Approximately half of patients with common cancer types and moderate to severe N/T may experience poor QOL. As well, CRC patients, but not other patient types, with neuropathic pain may see their QOL decline in the short term. While this decrease may be due to the fluctuating nature of neuropathic pain, priority next steps could include correlating the statistically significant factors associated with poor QOL in CRC patients (younger age, Hispanic ethnicity, and disease status) within our database population and then engage in prospective methods to understand how these factors lead to poor QOL. Additionally, clinicians reported difficulty in caring for patients of all types with moderate to severe N/T or neuropathic pain, which was most significant for the CRC patients. Now with identification of this clinician perspective for a substantial number of patients and some with notation of potential co-factors identified in our research, further studies are required to understand the exact nature of the problem, the interaction of the other factors identified in this report, which factors meaningfully compound the complexity of patient care, and whether clinician difficulty with care is perceived by the patient and thus contributes further to poor QOL.

Despite limitations, the current data have revealed the prevalence of neuropathic symptoms in a large number of CRC patients, who have a high rate of less than good QOL. Assuming that many of the patients had or were going to receive neuropathy-inducing agents, the ultimate goal is to educate and counsel patients and clinicians about CIPN and QOL changes with these agents in light of the CRC diagnosis. Several recent reviews and reports provide an overview of potential therapeutic treatment strategies (such as use of neuro-modulatory agents, and stop-and-go treatment), and other pharmacological and non-pharmacological options currently under study for the treatment and prevention of CIPN [22,25–29,6,30,23], Additional research on the clinicians’ care of neuropathic symptoms and how this affects patient QOL would be beneficial.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Public Health Service Grants CA37604, CA17145, and grants from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services. Drs. Fisch and Zhao had full access to the data.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES/CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors reported no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63 (1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Zaninelli M, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, Tabah-Fisch I, de Gramont A Investigators MISoO-FLitAToCC. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350 (23):2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.André T, Boni C, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Bonetti A, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, Rivera F, de Gramont A. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27 (19):3109–3116. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Friedlander M, Kiernan MC. Oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity and the development of neuropathy. Muscle & nerve. 2005;32 (1):51–60. doi: 10.1002/mus.20340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tofthagen C. Surviving chemotherapy for colon cancer and living with the consequences. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010;13 (11):1389–1391. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weickhardt A, Wells K, Messersmith W. Oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy in colorectal cancer. J Oncol. 2011;2011:201593. doi: 10.1155/2011/201593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Argyriou AA, Cavaletti G, Briani C, Velasco R, Bruna J, Campagnolo M, Alberti P, Bergamo F, Cortinovis D, Cazzaniga M, Santos C, Papadimitriou K, Kalofonos HP. Clinical pattern and associations of oxaliplatin acute neurotoxicity: a prospective study in 170 patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2013;119 (2):438–444. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett BK, Park SB, Lin CS, Friedlander ML, Kiernan MC, Goldstein D. Impact of oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy: a patient perspective. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20 (11):2959–2967. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tofthagen C, Donovan KA, Morgan MA, Shibata D, Yeh Y. Oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy’s effects on health-related quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21 (12):3307–3313. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1905-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mols F, Beijers T, Lemmens V, van den Hurk CJ, Vreugdenhil G, van de Poll-Franse LV. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and its association with quality of life among 2- to 11-year colorectal cancer survivors: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31 (21):2699–2707. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.49.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeves BN, Dakhil SR, Sloan JA, Wolf SL, Burger KN, Kamal A, Le-Lindqwister NA, Soori GS, Jaslowski AJ, Kelaghan J, Novotny PJ, Lachance DH, Loprinzi CL. Further data supporting that paclitaxel-associated acute pain syndrome is associated with development of peripheral neuropathy: North Central Cancer Treatment Group trial N08C1. Cancer. 2012;118 (20):5171–5178. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loprinzi CL, Reeves BN, Dakhil SR, Sloan JA, Wolf SL, Burger KN, Kamal A, Le-Lindqwister NA, Soori GS, Jaslowski AJ, Novotny PJ, Lachance DH. Natural history of paclitaxel-associated acute pain syndrome: prospective cohort study NCCTG N08C1. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29 (11):1472–1478. doi: 10.1200/jco.2010.33.0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speck RM, Sammel MD, Farrar JT, Hennessy S, Mao JJ, Stineman MG, DeMichele A. Impact of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy on Treatment Delivery in Nonmetastatic Breast Cancer. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2013 doi: 10.1200/jop.2012.000863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis MA, Zhao F, Jones D, Loprinzi C, Brell JM, Weiss M, Fisch MJ. Neuropathic Symptoms and their Risk Factors in Medical Oncology Outpatients with Colorectal versus Breast, Lung or Prostate Cancer - Results from a Prospective Mulitcenter Study. Support Care Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.300. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Chou C, Harle MT, Morrissey M, Engstrom MC. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89 (7):1634–1646. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fainsinger RL, Nekolaichuk CL, Lawlor PG, Neumann CM, Hanson J, Vigano A. A multicenter study of the revised Edmonton Staging System for classifying cancer pain in advanced cancer patients. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2005;29 (3):224–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain. 1995;61 (2):277–284. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00178-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stata Statistical Software. Release 11. StataCorp; College Station, TX: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loprinzi CL, Maddocks-Christianson K, Wolf SL, Rao RD, Dyck PJ, Mantyh P, Dyck PJ. The Paclitaxel acute pain syndrome: sensitization of nociceptors as the putative mechanism. Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass) 2007;13 (6):399–403. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31815a999b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lesser H, Sharma U, LaMoreaux L, Poole RM. Pregabalin relieves symptoms of painful diabetic neuropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2004;63 (11):2104–2110. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145767.36287.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith EM, Pang H, Cirrincione C, Fleishman S, Paskett ED, Ahles T, Bressler LR, Fadul CE, Knox C, Le-Lindqwister N, Gilman PB, Shapiro CL. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309 (13):1359–1367. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schloss JM, Colosimo M, Airey C, Masci PP, Linnane AW, Vitetta L. Nutraceuticals and chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): a systematic review. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2013;32 (6):888–893. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loprinzi CL, Qin R, Dakhil SR, Fehrenbacher L, Flynn KA, Atherton P, Seisler D, Qamar R, Lewis GC, Grothey A. Phase III Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study of Intravenous Calcium and Magnesium to Prevent Oxaliplatin-Induced Sensory Neurotoxicity (N08CB/Alliance) Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013 doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.52.0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beijers AJ, Jongen JL, Vreugdenhil G. Chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity: the value of neuroprotective strategies. The Netherlands journal of medicine. 2012;70 (1):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroder S, Beckmann K, Franconi G, Meyer-Hamme G, Friedemann T, Greten HJ, Rostock M, Efferth T. Can medical herbs stimulate regeneration or neuroprotection and treat neuropathic pain in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy? Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. 2013;2013:423713. doi: 10.1155/2013/423713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seretny M, Colvin L, Fallon M. Therapy for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310 (5):537–538. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith EM, Pang H. Therapy for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy--in reply. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310 (5):538. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postma TJ, Reijneveld JC, Heimans JJ. Prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a matter of personalized treatment? Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2013;24 (6):1424–1426. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroeder S, Meyer-Hamme G, Epplée S. Acupuncture for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): a pilot study using neurography. Acupunct Med. 2012;30 (1):4–7. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2011-010034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Y, Jones D, Palmer JL, Forman A, Dakhil SR, Velasco MR, Weiss M, Gilman P, Mills GM, Noga SJ, Eng C, Overman MJ, Fisch MJ. Oral alpha-lipoic acid to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]