Abstract

Most of the squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) of the skin and head and neck contain p53 mutations. The presence of p53 mutations in premalignant lesions suggests that they represent early events during tumor progression and additional alterations may be required for SCC development. Here we show that co-deletion of the p53 and αv integrin genes in mouse stratified epithelia induced SCCs in 100% of the mice, more frequently and with much shorter latency than deletion of either gene alone. The SCCs that lacked p53 and αv in the epithelial tumor cells exhibited high Akt activity, lacked multiple types of infiltrating immune cells, contained a defective vasculature, and grew slower than tumors that expressed p53 or αv. These results reveal that loss of αv in epithelial cells that lack p53 promotes SCC development, but also prevents remodeling of the tumor microenvironment and delays tumor growth. We observed that Akt inactivation in SCC cells that lack p53 and αv promoted anoikis. Thus, tumors may arise in these mice as a result of the increased cell survival induced by Akt activation triggered by loss of αv and p53, and by the defective recruitment of immune cells to these tumors, which may allow immune evasion. However, the defective vasculature and lack of a supportive stroma create a restrictive microenvironment in these SCCs that slows their growth. These mechanisms may underlie the rapid onset and slow growth of SCCs that lack p53 and αv.

Keywords: p53, squamous cell carcinoma, mouse model, integrins, tumor microenvironment

INTRODUCTION

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are malignant tumors that arise from the keratinocytes that form the stratified epithelial lining of the body, including the skin and the oral mucosa. Although SCCs represent less than one third of non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) diagnosed, they are responsible for most NMSC–related deaths 1. Also, SCC is the most common skin cancer in immunosuppressed organ transplant recipients, and the SCC risk is 65–250 times higher in this population than in the general population, suggesting that immune surveillance mechanisms protect against SCC development 2;3.

The p53 gene is the most frequently mutated gene in skin and head and neck SCCs, with p53 mutations present in over 50% of the human SCCs diagnosed 4-6. Mutations in p53 are also found in premalignant lesions that are considered SCC precursors, suggesting that p53 mutation is an early event that precedes progression to carcinoma 7;8. Indeed, patches of epidermal cells with p53 mutations have been observed in sun-exposed skin, although SCCs usually appear decades after p53 mutations are detected 9;10. Similarly, mice with conditional deletion of p53 in the skin developed SCCs after very long latency periods, indicating that additional molecular or cellular alterations are needed to promote SCC development 11-13.

The epithelial organization in the epidermis is maintained largely by the molecular adhesions that connect keratinocytes with adjacent cells and the underlying basement membrane. The integrin family plays a critical role in mediating cell adhesion and facilitating communication between keratinocytes and surrounding cells, and with components of the stroma 14; and they are also involved in cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, migration and in cytoskeletal organization 15. Integrins are a family of heterodimeric adhesion, transmembrane proteins, each composed of an α and a β subunit. The most highly expressed integrins in human and murine epidermis are α6β4, which is a component of the hemidesmosomes that mediate adhesion to laminin-332 in the basement membrane, and β1 integrins (primarily α2β1 and α3β1), which are expressed in cell clusters in epidermal basal cells and hair follicles 16;17; αv integrins are detected at lower levels in the skin. The αv subunit forms heterodimeric complexes with β1, β3, β5, β6, and β8. In the skin and oral mucosa, the primary integrins containing αv units are αvβ5, which is expressed at low levels, and αvβ6, which is not detected in the intact skin but is induced in the skin during wound healing 18;19.

The expression of integrins such as αv is altered in human SCCs, resulting in complex, dynamic expression patterns 20. A switch from αvβ5 expression to αvβ6 is frequently observed in human SCCs, and αv expression tends to be higher in the less differentiated areas of these tumors 21-23. In mice, conditional deletion of the αv integrin using a transgene expressing Cre under the control of the glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) promoter induced epithelial tumors arising from the conjunctiva 24, suggesting that αv has a tumor suppressor role in the periorbital epithelium. However, the GFAP-Cre line used in these studies was expressed only in the developing epithelium of the eyelid, raising the question of whether the eyelid epithelium is highly susceptible to cancer in the setting of αv deletion or whether αv has a general tumor suppressor role in stratified epithelia.

To investigate how loss of αv affects the development of SCCs of the skin and head and neck area, we deleted the αv gene in stratified epithelia, including the epidermis and oral mucosa. Because most of the human SCCs carry mutations in p53, we examined the potential tumor suppressor role of αv in epithelial cells in which the p53 gene was also deleted.

RESULTS

Loss of p53 and αv Integrin Cooperate to Induce Skin and Oral SCCs

To determine the consequences of deleting the αv integrin gene (Itgav) in stratified epithelia, we crossed mice carrying floxed alleles for αv (αvf) with K14.CrePR1 transgenic mice, which express a Cre recombinase that can be activated in stratified epithelia upon exposure to RU486 25;26. Leaky Cre activity in K14.CrePR1 mice also allows activation of conditional alleles in a subset of cells in the epidermis and in the mucosa of the oral and anorectal epithelia 26. As p53 is the major tumor suppressor gene in human cutaneous and oral SCCs, we were interested in assessing whether loss of αv modulates the tumor suppressor function of p53 in the epidermis and oral mucosa. Thus, we crossed the αvf mice with floxed p53 mice (p53f) 11 and generated mice carrying homozygous or heterozygous combinations of αvf and p53f alleles in the presence of K14.CrePR1. To maximize Cre activation in the epidermis, newborn mice received a daily topical application of RU486 (1 mg/ml) for 3 days.

Surprisingly, only 2 of 26 mice with homozygous deletion of αv (αvf/f-p53wt/wt mice) developed SCCs by 24 months of age. This low tumor incidence may be explained by the induction of p53 in emerging tumors that lost αv (Supplementary Figure S1). The incidence of SCC in these mice was significantly lower than that observed in mice with homozygous deletion of p53 alone (αvwt/wt-p53f/f), half of which developed SCCs by 20 months of age. Nevertheless, SCCs developed with long latencies in both αvf/f-p53wt/wt and αvwt/wt-p53f/f mice, suggesting that although deletion of either αv or p53 predispose to SCC, additional genetic and/or molecular barriers prevent SCC development. Remarkably, mice in which both copies of the p53 and αv genes were co-deleted (αvf/f-p53f/f) developed SCCs with an average latency of only 6–7 months and 100% penetrance (Figure 1a). The tumor latency increased in the presence of a wild-type (wt) allele for either αv or p53, and tumors appeared slightly faster in αvf/f-p53f/wt mice (14–15 months) than in αvf/wt-p53f/f mice (16–7 months). Notably, only 5 of the mice studied developed metastasis (1 αvf/f-p53f/f mouse, 2 αvf/f-p53f/wt mice, and 2 αvf/wt-p53f/f mice). Overall, these findings indicate that loss of p53 and αv cooperate to induce SCC development. Because p53 mutations are found in most of the human SCCs, these observations suggest that loss of αv facilitates SCC development from epithelial cells that accumulate mutations in p53.

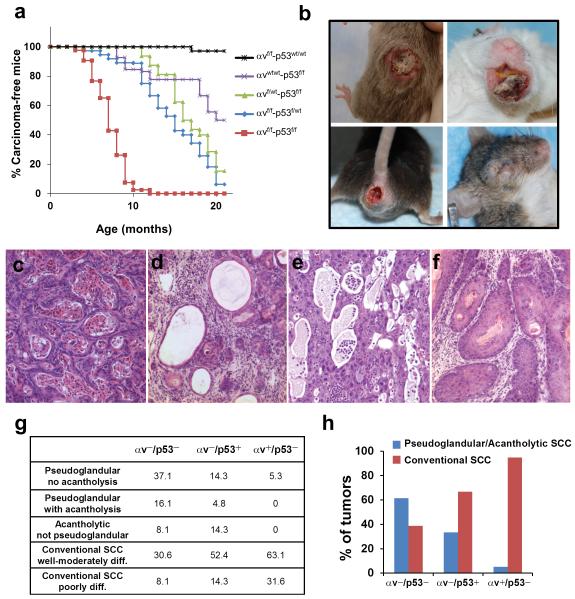

Figure 1. Cooperation of loss of p53 and αv integrin during SCC development.

(a) Kinetics of SCC development induced by deletion of p53 and αv in stratified epithelia. Percentage of carcinoma-free mice are represented over time in mice with the following genotypes: αvf/f-p53wt/wt (black line; n = 26), αvwt/wt-p53f/f (purple line; n = 16), αvf/wt-p53f/f (green line; n = 20), αvf/f-p53f/wt (blue line; n = 34), αvf/f-p53f/f (red line; n = 39). p< 0.05 for the following comparisons: αvf/f-p53f/f with each of the other groups; αvf/f-p53f/wt with αvf/f-p53wt/wt and αvwt/wt-p53f/f; αvf/wt-p53f/f with αvf/f-p53wt/wt. (b) Gross appearance of tumors that developed in the skin, mouth, anal epithelium and eyelid of αvf/f-p53f/f mice. (c–f) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the primary phenotypes observed in SCCs that developed in αvf/f-p53f/f mice. (g) Quantification of the main phenotypic variants observed in SCCs that lacked both αv and p53 (αv−/p53−), only αv (αv−/p53+), or only p53 (αv+/p53−). (h) Graphical representation of the relative proportion of pseudoglandular/acantholytic SCCs and conventional SCCs in αv−/p53−, αv−/p53+, and αv+/p53− tumors.

Distinct Phenotypic Variants in SCCs Induced by Co-deletion of p53 and αv

Most of the αvf/f-p53f/f mice (92%) developed skin tumors, and a significant number of these mice also developed tumors in the head and neck (17%), the anorectal epithelia (14%), and the periorbital area (6%) (Figure 1b and Supplementary Table S1). This distribution of tumor locations was similar to that in mice with other genotypes analyzed in this study, although the incidence of oral tumors was slightly higher in αvf/f-p53f/wt mice (28%).

Histologically, most of the tumors that developed in the αvf/f-p53f/f mice (hereafter referred to as αv−/p53− tumors) were invasive SCCs, with a spectrum of phenotypic variants. Over one third of the αv−/p53− SCCs comprised nests of tumor cells organized in pseudoglandular formations enclosing terminally differentiated keratinocytes (Figure 1c). In some tumors, these intraluminal cells were lost as a result of acantholysis (Figure 1d), and other tumors exhibited extensive areas devoid of cells, with no apparent pseudoglandular formations surrounding the empty spaces, suggesting complete degeneration (Figure 1e). Collectively, these phenotypes represent histologic variants of pseudoglandular or acantholytic SCCs 27. Of the αv−/p53− tumors, approximately 30% were conventional, well- to moderately differentiated SCCs (Figure 1f), whereas less than 10% of the tumors were poorly differentiated SCCs that occasionally exhibited areas with marked epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (not shown).

Interestingly, the distribution of the phenotypic variants observed in the αv−/p53− tumors differed from that of tumors that developed in mice carrying wt alleles for either αv (αvf/wt-p53f/f or αvwt/wt-p53f/f, hereafter referred to as αv+/p53− SCCs) or p53 (αvf/f-p53f/wt or αvf/f-p53wt/wt, hereafter referred to as αv−/p53+ SCCs) (Figure 1g). Overall, pseudoglandular or acantholytic phenotypes were observed in over 60% of the αv−/p53− tumors, less than 35% of the αv−/p53+ tumors, and 5% of the αv+/p53− tumors (Figure 1h). Conversely, over 90% of αv+/p53− tumors and 60% of the αv−/p53+ tumors were conventional SCCs, compared with less than 40% of the αv−/p53− tumors exhibiting such phenotype. Together, these results indicate that loss of both p53 and αv integrin induced the development of SCCs that tend to display pseudoglandular or acantholytic features, a phenotype promoted primarily by the loss of αv. To assess potential changes in the expression of other alpha integrins after deletion of αv, we analyzed the expression of α6 in SCCs (Supplementary Figure S2). As expected, α6 localized to the basal surface of the basal cells in the epithelial component of αv+/p53− conventional SCCs. A similar expression pattern was observed in psudoglandular/acantholytic αv−/p53− SCCs, indicating that the loss of αv did not impair the expression and localization of α6. The other two alpha integrins expressed in stratified epithelia (α2 and α3) showed much lower expression and a diffuse pattern in both αv+/p53− and αv−/p53− SCCs (not shown).

Activation of Akt and Erk Pathways in SCCs that Lack p53 and αv

In addition to their fundamental role in mediating cell-cell and cell-substrate adhesion, integrins can regulate signaling pathways that contribute to their pleiotropic effects during tissue homeostasis and disease 15. Specifically, αv integrins can bind to and modulate the activity of cell surface receptors, including growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases 28. Notably, analysis of the phosphorylation levels of Akt and Erk revealed little to no activation of these pathways in αv+/p53− SCCs, moderate activation in αv−/p53+ SCCs and a much stronger activation in αv−/p53− SCCs (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figure S3). Phosphorylation of Akt and Erk in the epithelial cells of the αv−/p53− tumors was confirmed by immunohistochemical analysis (Figures 2b and c). Thus, the loss of both p53 and αv promoted the synergistic activation of Akt and Erk in SCCs. Interestingly, Akt was shown to protect human SCC cells from detachment-induced cell death (anoikis) 29. We also found that Akt activity prevents anoikis in cells derived from an αv−/p53− SCC (Supplementary Figure S4), suggesting that activation of Akt induced by the loss of p53 and αv promotes cell survival during SCC development.

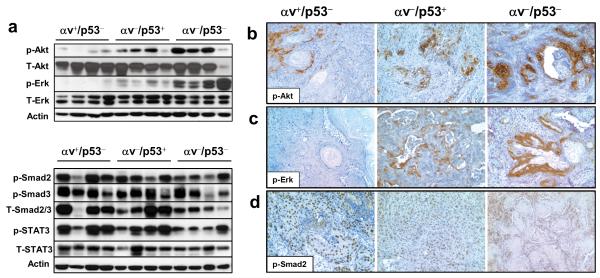

Figure 2. Activation of Akt and Erk in SCCs that lack both p53 and αv.

(a) The top panel shows a western blot analysis with specific antibodies for phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt) and phosphorylated Erk (p-Erk) and the corresponding total proteins (T-Akt and T-Erk, respectively) in representative αv+/p53−, αv−/p53+, and αv−/p53− tumors. The bottom panel shows a western blot for phosphorylated Smad2 (p-Smad2), phosphorylated Smad3 (p-Smad3), and phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3), and the corresponding total proteins (T-Smad2/3 and T-STAT3) using total protein lysates from representative αv+/p53−, αv−/p53+ and αv−/p53− tumors. Actin was used as a loading control. (b-d) Immunohistochemical staining for p-Akt (b), p-Erk (c), and p-Smad2 (d) in the indicated tumors. Note the strong staining for p-Akt and p-Erk in the epithelial component of the αv−/p53− tumors, and p-Smad2 in the nuclei of epithelial cells.

αv integrins can also promote transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling by inducing the dissociation of the latency-associated peptide (LAP) from the LAP-TGF-β complex that maintains TGF-β in an inactive form 30. Because TGF-β inhibits keratinocyte growth, it was speculated that αv integrins may protect against squamous tumorigenesis by promoting TGF-β activation. 24. To evaluate the activation status of the TGF-β pathway in αv−/p53− tumors, we analyzed phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3, the primary mediators of TGF-β signaling. We detected phosphorylated Smad2 and/or Smad3 in most of the SCCs analyzed, including αv−/p53− tumors, with slight variation between tumors of all genotypes (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figure S3). Because TGF-β can also induce proliferation of stromal fibroblasts, we decided to identify the tumor cell types that showed activated Smad. Immunohistochemical analysis of the SCCs revealed strong nuclear staining for p-Smad2 primarily in the epithelial tumor cells (Figure 2d). These findings suggest that inactivation of the TGF-β pathway is not a major mechanism that accelerates the development of αv−/p53− SCCs. Similarly, activation of STAT3, which can be mediated by a wide variety of cytokines commonly found in tumors, was observed in most of the tumors we studied.

Defective Remodeling of the Tumor Microenvironment in SCCs that Lack Epithelial p53 and αv

Tumor-associated integrins are essential mediators of the interactions between epithelial tumor cells and the different components of the stroma, including the extracellular matrix, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and immune cells. Therefore, integrins may affect the dynamic evolution of epithelial tumors from the early stages to malignant progression. Interestingly, αv integrins promote homing of immune cells to emerging tumors 31, but it is presently unknown whether the integrins expressed in epithelial tumor cells participate in this process. To determine the impact of the loss of epithelial αv and p53 on leukocyte infiltration in SCCs, we stained tumors with a specific antibody for CD45, a general leukocyte marker. Remarkably, while αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ tumors contained extensive leukocyte infiltration, CD45 was largely undetected in αv−/p53− SCCs. Indeed, quantification indicated an over a 100-fold reduction in CD45+ cells (Figures 3a and b).

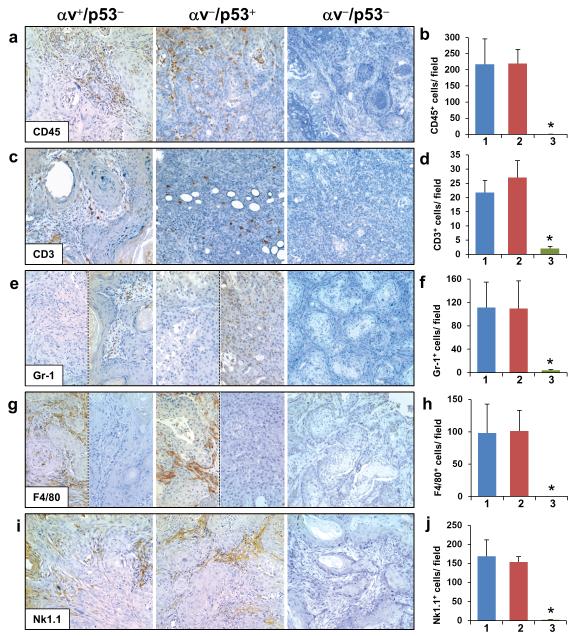

Figure 3. Lack of immune cell infiltration in αv−/p53− SCCs.

Immunohistochemical analysis and quantification of the staining for CD45 (a,b), CD3 (c,d), Gr-1 (e,f), F4/80 (g,h), and Nk1.1 (i,j) in histologic sections from αv+/p53−, αv−/p53+, and αv−/p53− SCCs. Note that sections from the same tumors are shown in e and g for αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ tumors to illustrate the inverse correlation frequently observed between Gr-1 and F4/80 staining. Quantification of the staining in αv+/p53− SCCs (1, blue columns), αv−/p53+ (2, red columns) and αv−/p53− SCCs (3, green columns) is represented as the average number of cells per field in 5 tumors per genotype. *p< 0.05 for comparisons with each of the other two groups.

We analyzed in more detail the nature of the infiltrating cells in SCCs by staining the tumors with antibodies for molecular markers of lymphocytes (CD3), neutrophils (Gr-1), macrophages (F4/80), and natural killer cells (Nk1.1). The numbers of CD3+ cells in αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ tumors were similar and both significantly higher than those in αv−/p53− SCCs (Figures 3c and d). Staining for Gr-1 revealed high levels of neutrophils in αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ tumors, but not in αv−/p53− SCCs (Figures 3e and f); the number of Gr-1+ cells varied among αv+/p53− tumors and among αv−/p53+ tumors, with an elevated number of neutrophils in some tumors and almost none detected in others. Similarly, macrophages were detected in variable amounts in both αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ SCCs but were not found in αv−/p53− SCCs (Figures 3g and h). Notably, the presence of neutrophils and macrophages was inversely correlated in most αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ SCCs; tumors with high levels of neutrophils tended to have few macrophages, and vice versa. Finally, we observed a lack of natural killer cells in αv−/p53− SCCs but not in tumors that expressed either αv or p53 (Figures 3i and j).

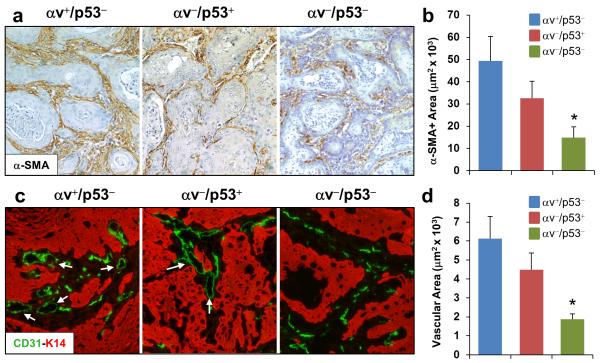

These findings prompted us to analyze other components of the stroma. This analysis revealed that CAFs, identified by the expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α–SMA), were present in tumors of all genotypes, although at significantly lower levels in αv−/p53− tumors than in αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ tumors (Figures 4a and b). In addition, a detailed examination of the tumor vasculature identified the presence of endothelial cells in tumors of all genotypes. However, whereas αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ SCCs contained well-organized microvessels with defined lumens, the vasculature of αv−/p53− tumors consisted primarily of endothelial cells that lacked defined luminal formations (Figure 4c). Indeed, quantification of the area encompassed by vascular cells revealed that microvessels in the αv−/p53− tumors covered a significantly smaller area of the tumor than those in αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ tumors (Figure 4d). These observations indicate that SCCs that lack epithelial αv and p53 contain a distinctive tumor microenvironment characterized by reduced levels of CAFs, a defective tumor vasculature, and a nearly complete absence of infiltrating immune cells.

Figure 4. Defective angiogenesis in SCCs induced by co-deletion of epithelial αv and p53.

(a) Immunohistochemical staining for α-SMA in αv+/p53−, αv−/p53+, and αv−/p53− SCCs. (b) Quantification of the staining shown in panel a. (c) Double immunofluorescence for CD31 (endothelial cells, in green) and K14 (epithelial tumor cells, in red) in the indicated tumors. Arrows point to vessels that contain well-defined lumens. (d) Quantification of the area covered by endothelial cells in the tumors. *p< 0.05 for comparisons with each of the other two groups.

Lack p53 and αv in Epithelial Tumor Cells Delays Tumor Growth

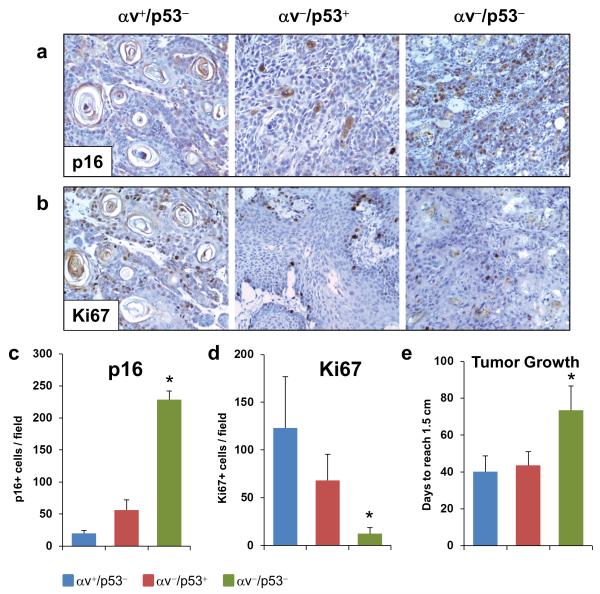

The cellular content and architecture of the stroma of αv−/p53− SCCs suggest that these tumors contain a restrictive microenvironment, most evidenced by the defective organization of the tumor vasculature, which may compromise the nutrient supply in these tumors. Indeed, we found that p16, a tumor suppressor induced under multiple stress conditions including nutrient deprivation, was highly expressed in the epithelial cells of the αv−/p53− tumors, but not in αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ tumors (Figures 5a and c). Remarkably, the elevated expression of p16 in αv−/p53− tumors was accompanied by a significant reduction in expression of the proliferation marker Ki67, suggesting a slower cell growth in tumors induced by deletion of the αv and p53 genes in epithelial cells (Figures 5b and d). These observations prompted us to perform an exhaustive review of the rates of tumor growth in the mice generated in this study. Notably, we found that the αv−/p53− tumors took almost twice as long as the αv+/p53− and αv−/p53+ tumors to reach 1.5 cm in diameter since they were first identified (Figure 5e), indicating that despite the more rapid SCC development induced by co-deletion of p53 and αv in keratinocytes, subsequent tumor growth was compromised in the absence of both p53 and αv.

Figure 5. Lack of p53 and αv in epithelial tumor cells impairs tumor growth.

(a-b) Immunohistochemical analysis for p16 (a) and Ki67 (b) in αv+/p53−, αv−/p53+, and αv−/p53− SCCs. (c-d) Quantification of the p16 (c) and Ki67 (d) staining in panels a and b. (e) Tumor growth rates determined by the number of days elapsed between the date of the initial detection of the tumors and the date when they reached 1.5 cm in diameter. *p< 0.05 for comparisons with each of the other two groups.

Overall, these observations indicate that loss of αv expression in epithelial cells that acquire p53 mutations allows the rapid development of SCCs. However, as the tumors progress, loss of αv hinders tumor growth. This may explain why mutations in αv are not found in human SCCs; a transient loss of αv may suffice to allow SCC development and, as the tumor grow, reactivation of αv may promote tumor growth. This analysis was consistent with the decreased expression of αv observed in papillomas that were induced in the mouse skin by activation of oncogenic K-ras and mutant p53 in a previously generated mouse model for skin cancer progression 12;32 (Supplementary Figure S5). Interestingly, the expression of αv increased in SCCs that developed in those mice and was highest in spindle cell carcinomas (SpCCs), the most aggressive tumors that developed in this model.

DISCUSSION

In this study we generated mouse models that allowed us to demonstrate that loss of p53 and αv integrin cooperate during the development of SCCs of the skin and the head and neck area. The high Akt activity observed in tumors that lack p53 and αv suggests that resistance to anoikis promoted by Akt allows survival of keratinocytes that detach from their natural substrate and facilitate their growth into emerging tumors. Unlike SCCs that contained wt alleles for either p53 or αv, the tumor microenvironment of SCCs induced by co-deletion of p53 and αv in keratinocytes was characterized by a defective vasculature and lack of both infiltrating immune cells and CAFs. The impaired recruitment of anti-tumor immune cells may facilitate immune evasion of emerging tumor, which contributes to the accelerated tumor formation. The defective vasculature and lack of tumor-promoting stromal cells may be responsible for the slow growth of tumors that lacked p53 and αv. Thus, these mouse models represent an in vivo system in which genetic changes that accumulate in the epithelial cells determine not only the cell-autonomous mechanisms that allow expansion of tumor cells, but also the organization of the surrounding stroma, with a profound impact in tumor development and progression.

The low incidence of SCCs observed upon deletion of αv by K14.CrePR1 suggested that epithelial cells targeted by GFAP-Cre and K14.CrePR1 are differently predisposed to SCC induced by deletion of αv. As we found that the additional loss of p53 increased dramatically the SCC rates, the higher tumor incidence observed when αv was deleted by GFAP-Cre may result from the GFAP expression in precursor cells of the eyelid epithelium that have lower p53 activity, as has been observed in embryonic stem cells 33;34. Moreover, αv can inactivate the p53 function in certain cell types, including human melanoma cells 35;36, suggesting that the p53 and αv interaction may affect a broader spectrum of tumor types.

Mutations in p53 are found in most of the human SCCs. However, αv mutations have not been reported in human SCCs. We propose that the transient or epigenetic inactivation of αv in keratinocytes that accumulate p53 mutations facilitates SCC formation, which may have profound implications for the dynamics of SCC development because p53 mutations are frequently found in sun-exposed skin 7;8. However, tumors rarely develop from those cells. Our findings suggest that the loss of αv expression in p53-mutant keratinocytes may trigger SCC development. However, as tumors grow, the lack of p53 and αv in the epithelial tumor cells blocks the remodeling of the tumor microenvironment that promotes tumor growth. Thus, a reactivation of αv in established tumors would facilitate tumor growth, in agreement with the elevated levels of αv found in advanced SCCs in mice (Supplementary Figure S5) and in humans, where high levels of αv were found in the leading front of SCCs 23. Notably, a switch from αvβ5 to αvβ6 occurs during SCC development 20;29, as αvβ5 is expressed in the normal epidermis, but is lost during SCC progression; conversely, αvβ6 is not detected in the epidermis, but is upregulated in SCCs. In light of these dynamic changes in the expression of αv integrins, the contrasting phenotypes that we observed after deletion of αv in the skin (promoting SCC development, but suppressing tumor growth) may result from the opposing functions of αvβ5 and αvβ6, as αvβ5 may function as a tumor suppressor, whereas αvβ6 may be oncogenic. Because αv deletion eliminates both αvβ5 and αvβ6, loss of αvβ5 may facilitate SCC formation, whereas the lack of αvβ6 in these tumors may prevent tumor growth. These mechanisms are compatible with changes in the expression of αv during SCC progression discussed above, and it is possible that they operate together during SCC development.

It has been reported that the human SCC cells H357, which lack αv and contain a p53 mutation, were resistant to anoikis 37. Restoring αv in these cells blocked Akt activation and induced anoikis, and expression of a constitutively active Akt suppressed anoikis, suggesting that αv induced anoikis by blocking Akt activation; however, the role of p53 in this model was not tested 29. Our data indicate that Akt activity was much higher in αv−/p53− SCCs than in tumors that expressed either p53 or αv, and that blockade of Akt activity in αv−/p53− SCC cells promotes anoikis. Collectively, these observations suggest that the loss of αv facilitates survival of p53-mutant epithelial cells that detach from the epithelial basement membrane, due to the high Akt activity promoted by the loss of αv in the absence of p53. Thus, inhibition of anoikis seems to be an early step of SCC development in our model. Importantly, our data suggest that blockade of the Akt pathway in combination with αv integrin inhibitors may be used to treat patients with SCCs that carry p53 mutations and to prevent tumor growth.

The evolution of solid tumors is not only determined by the genetic component of the epithelial tumor cells, but also by the dynamic interaction of these cells with the surrounding stroma 38. Notably, our studies demonstrate that the genetic content of the epithelial tumor cells modulates the architecture of the tumor microenvironment. The impact that these changes in the stroma had on tumor development will require further systematic analysis. We propose that the defective recruitment of immune cells may allow emerging tumors that lack p53 and αv to evade immune surveillance. This mechanism may have important clinical implications because the well-documented high risk of SCCs in immunosuppressed patients implies that immune surveillance is a primary mechanism of defense against SCC development 2;3. Our findings suggest that epithelial cells that lack αv and p53 expression evade the anti-cancer immune response by limiting the presence of immune cells in the environment of nascent tumors. The defective angiogenesis observed in these tumors is likely to play a significant role in this process.

However, as SCCs increase in size, a deficient vasculature may restrain tumor growth by limiting their supply of nutrients. In addition, although the immune system protects against SCC development, infiltrating immune cells can also promote tumor progression, and so do CAFs 38;39. We speculate that deficits in vasculature and cellular components of the stroma in αv−/p53− SCCs pose a barrier to tumor growth that may explain why αv−/p53− tumors grew significantly slower than tumors that expressed αv or p53. The lack of a supportive stroma may also be why the αv−/p53− tumors did not metastasize, despite how rapidly they formed. However, metastasis rates were also low for tumors that expressed either αv or p53, which contained a more robust stroma than αv−/p53− SCCs. How the changes in the microenvironment induced by epithelial αv and p53 contribute to metastasis will have to be determined in mouse models prone to metastasis 12.

In summary, we have shown that co-deletion of the p53 and αv genes in stratified epithelia promoted the rapid development of SCCs, which were characterized by slow growth and a markedly defective microenvironment. The accelerated tumor development induced by loss of epithelial p53 and αv may be promoted by both Akt activation, which blocks anoikis, and the defective recruitment of immune cells, which allows epithelial tumor cells to escape from immune surveillance. The slow growth of αv−/p53− SCCs is also consistent with a primary contribution of the stroma to the tumor development because the defective angiogenesis may limit the nutrient supply required to sustain tumor growth, and the lack of pro-tumorigenic stromal cells may prevent tumor progression. Finally, our findings may help improve therapies to treat SCC carcinomas that carry p53 mutations using a combination of inhibitors of αv integrin and Akt.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse Models

Mice carrying the K14.CrePR1 transgene and conditional alleles for αv and p53 have been previously described 11;26;40. Mouse genotyping and analysis of the activation of conditional alleles (Supplementary Figure S6) was performed by PCR as previously described 11;25;40;41. Mice with excessive tumor burden per The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines were euthanized, their tumors were harvested, and their thoracic and abdominal cavities were assessed for evidence of metastasis. Tumor development was represented using Kaplan-Meier curves, and the log-rank test was used to assess differences between groups. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All comparative studies were conducted using littermates with the indicated genotypes. Overall, research involving mice was performed in compliance with the IACUC guidelines.

Histologic and Immunohistochemical Analysis

Tumors were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Samples were then transferred to 75% ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Histologic sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or processed for immunohistochemical analysis. Tissue sections used for immunohistochemical analysis were deparaffinized and then rehydrated following xylene and alcohol series. Antigen retrieval was performed in 100 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0), and endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 1% hydrogen peroxide. Then, tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies for p-Akt (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA); p-Erk and p-Smad2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); CD45, Gr-1, F4/80 and Nk1 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA); CD3, α–SMA and Ki67 (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL); p16 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Primary antibodies were detected using the ImmPRESS system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Slides were visualized on a Leica DMLA microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL), and images were captured with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera (Shizuoka, Japan).

Western Blotting Analysis

Total lysates were generated by solubilizing tumors in Laemmli protein loading buffer and heating at 100°C for 10 min. An equal amount of proteins from each sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and gels were transferred onto Hybond-P membranes (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). Membranes were incubated with the antibodies for p-Smad2, Smad2/3, p-Akt, total-Akt, p-Erk, total-Erk, p-STAT3 and total-STAT3 from Cell Signaling Technology; phospho-Smad3 (Epitomics) and actin (Santa Cruz). Signal was detected by incubating the membranes with secondary antibodies labeled with horseradish peroxidase and revealed with the ECL Plus detection system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Analysis of the Tumor Vasculature

Tumors were double-stained with CD31 (BioLegend) and K14 (Covance, Princeton, NJ) antibodies. Briefly, harvested tumors were embedded in OCT, frozen on dry ice, sectioned, and stored at −80°C until used. Tumor sections were fixed in 75% acetone/25% ethanol at −20°C for 15 min, blocked with 5% BSA for 30 min, and incubated with primary antibodies. The slides were then washed 2 times with PBS-0.1% Tween, 2 times with PBS and finally rinsed 3 times with dH2O. Then, tumor sections were incubated with 1 mg/ml BSA in PBS for 15 min followed by secondary antibodies labeled with Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 1 h. Slides were then washed as indicated above, rinsed with 100% ethanol, and mounted with VECTASHIELD (Vector Laboratories).

The immunofluorescence signal was visualized on an Olympus IX71 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA), and images were captured using a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera (Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan) and processed with Photoshop CS5 (Adobe, San Jose, CA). The microvessel area was determined in representative images of the different tumors in which the number of pixels occupied by vessels was computed in Photoshop and transformed into the surface area. At least 4 images per tumor were analyzed in all studies.

Statistical Analysis

All groups were compared using the 2-tailed Student t-test. Error bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dennis Roop for the K14.CrePR1 mice, Anton Berns for the floxed p53 mice, and Sarah Bronson and Dawn Chalaire for editorial assistance.

Funding Source: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health through grant DE015344 (C. Caulin) and a Pilot Project grant from the American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant Program (J. McCarty). Veterinary services and core facilities at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center were supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through Cancer Center Support Grant CA16672.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Brantsch KD, Meisner C, Schonfisch B, Trilling B, Wehner-Caroli J, Rocken M, et al. Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:713–720. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindelof B, Sigurgeirsson B, Gabel H, Stern RS. Incidence of skin cancer in 5356 patients following organ transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:513–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1681–1691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brash DE, Rudolph JA, Simon JA, Lin A, McKenna GJ, Baden HP, et al. A role for sunlight in skin cancer: UV-induced p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10124–10128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolshakov S, Walker CM, Strom SS, Selvan MS, Clayman GL, El Naggar A, et al. p53 mutations in human aggressive and nonaggressive basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, Bettegowda C, Chang K, Li RJ, et al. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333:1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell C, Quinn AG, Ro YS, Angus B, Rees JL. p53 mutations are common and early events that precede tumor invasion in squamous cell neoplasia of the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:746–748. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12475717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziegler A, Jonason AS, Leffell DJ, Simon JA, Sharma HW, Kimmelman J, et al. Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature. 1994;372:773–776. doi: 10.1038/372773a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakazawa H, English D, Randell PL, Nakazawa K, Martel N, Armstrong B, et al. UV and skin cancer: specific p53 gene mutation in normal skin as a biologically relevant exposure measurement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:360–364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonason AS, Kunala S, Price GJ, Restifo RJ, Spinelli HM, Persing JA, et al. Frequent clones of p53-mutated keratinocytes in normal human skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14025–14029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonkers J, Meuwissen R, van der GH, Peterse H, van d, V, Berns A. Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2001;29:418–425. doi: 10.1038/ng747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caulin C, Nguyen T, Lang GA, Goepfert TM, Brinkley BR, Cai WW, et al. An inducible mouse model for skin cancer reveals distinct roles for gain- and loss-of-function p53 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1893–1901. doi: 10.1172/JCI31721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Cruz AB, Santos M, Lara MF, Segrelles C, Ruiz S, Moral M, et al. Spontaneous squamous cell carcinoma induced by the somatic inactivation of retinoblastoma and Trp53 tumor suppressors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:683–692. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watt FM. Role of integrins in regulating epidermal adhesion, growth and differentiation. EMBO J. 2002;21:3919–3926. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De LM, Tamura RN, Kajiji S, Bondanza S, Rossino P, Cancedda R, et al. Polarized integrin mediates human keratinocyte adhesion to basal lamina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:6888–6892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peltonen J, Larjava H, Jaakkola S, Gralnick H, Akiyama SK, Yamada SS, et al. Localization of integrin receptors for fibronectin, collagen, and laminin in human skin. Variable expression in basal and squamous cell carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1916–1923. doi: 10.1172/JCI114379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hertle MD, Kubler MD, Leigh IM, Watt FM. Aberrant integrin expression during epidermal wound healing and in psoriatic epidermis. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1892–1901. doi: 10.1172/JCI115794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haapasalmi K, Zhang K, Tonnesen M, Olerud J, Sheppard D, Salo T, et al. Keratinocytes in human wounds express alpha v beta 6 integrin. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:42–48. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12327199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janes SM, Watt FM. New roles for integrins in squamous-cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:175–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breuss JM, Gallo J, DeLisser HM, Klimanskaya IV, Folkesson HG, Pittet JF, et al. Expression of the beta 6 integrin subunit in development, neoplasia and tissue repair suggests a role in epithelial remodeling. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 6):2241–2251. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones J, Watt FM, Speight PM. Changes in the expression of alpha v integrins in oral squamous cell carcinomas. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26:63–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1997.tb00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu A, Esmaeli B, Hayek B, Hossain MG, Shinder R, Lazar AJ, et al. Analysis of alphav integrin protein expression in human eyelid and periorbital squamous cell carcinomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:570–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarty JH, Barry M, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Lacy-Hulbert A, Hynes RO. Genetic ablation of alphav integrins in epithelial cells of the eyelid skin and conjunctiva leads to squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1740–1747. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarty JH, Lacy-Hulbert A, Charest A, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Housman D, et al. Selective ablation of alphav integrins in the central nervous system leads to cerebral hemorrhage, seizures, axonal degeneration and premature death. Development. 2005;132:165–176. doi: 10.1242/dev.01551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caulin C, Nguyen T, Longley MA, Zhou Z, Wang XJ, Roop DR. Inducible activation of oncogenic K-ras results in tumor formation in the oral cavity. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5054–5058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1989.tb00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streuli CH, Akhtar N. Signal co-operation between integrins and other receptor systems. Biochem J. 2009;418:491–506. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janes SM, Watt FM. Switch from alphavbeta5 to alphavbeta6 integrin expression protects squamous cell carcinomas from anoikis. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:419–431. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJ, Dalton SL, Wu J, et al. The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell. 1999;96:319–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin H, Su J, Garmy-Susini B, Kleeman J, Varner J. Integrin alpha4beta1 promotes monocyte trafficking and angiogenesis in tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2146–2152. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torchia EC, Caulin C, Acin S, Terzian T, Kubick BJ, Box NF, et al. Myc, Aurora Kinase A, and mutant p53(R172H) co-operate in a mouse model of metastatic skin carcinoma. Oncogene. 2011;31:2680–2690. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spike BT, Wahl GM. p53, Stem Cells, and Reprogramming: Tumor Suppression beyond Guarding the Genome. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:404–419. doi: 10.1177/1947601911410224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aladjem MI, Spike BT, Rodewald LW, Hope TJ, Klemm M, Jaenisch R, et al. ES cells do not activate p53-dependent stress responses and undergo p53-independent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Curr Biol. 1998;8:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stromblad S, Fotedar A, Brickner H, et al. Loss of p53 compensates for alpha v-integrin function in retinal neovascularization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13371–13374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao W, Stromblad S. Integrin alphav-mediated inactivation of p53 controls a MEK1-dependent melanoma cell survival pathway in three-dimensional collagen. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:745–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones J, Sugiyama M, Speight PM, Watt FM. Restoration of alpha v beta 5 integrin expression in neoplastic keratinocytes results in increased capacity for terminal differentiation and suppression of anchorage-independent growth. Oncogene. 1996;12:119–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lacy-Hulbert A, Smith AM, Tissire H, Barry M, Crowley D, Bronson RT, et al. Ulcerative colitis and autoimmunity induced by loss of myeloid alphav integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15823–15828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acin S, Li Z, Mejia O, Roop DR, El-Naggar AK, Caulin C. Gain-of-function mutant p53 but not p53 deletion promotes head and neck cancer progression in response to oncogenic K-ras. J Pathol. 2011;225:479–489. doi: 10.1002/path.2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.