Abstract

The Rap G protein signal regulates Notch activation in early thymic progenitor cells, and deregulated Rap activation (Raphigh) results in the development of Notch-dependent T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). We demonstrate that the Rap signal is required for the proliferation and leukemogenesis of established Notch-dependent T-ALL cell lines. Attenuation of the Rap signal by the expression of a dominant-negative Rap1A17 or Rap1GAP, Sipa1, in a T-ALL cell line resulted in the reduced Notch processing at site 2 due to impaired maturation of Adam10. Inhibition of the Rap1 prenylation with a geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor abrogated its membrane-anchoring to Golgi-network and caused reduced proprotein convertase activity required for Adam10 maturation. Exogenous expression of a mature form of Adam10 overcame the Sipa1-induced inhibition of T-ALL cell proliferation. T-ALL cell lines expressed Notch ligands in a Notch-signal dependent manner, which contributed to the cell-autonomous Notch activation. Although the initial thymic blast cells barely expressed Notch ligands during the T-ALL development from Raphigh hematopoietic progenitors in vivo, the ligands were clearly expressed in the T-ALL cells invading extrathymic vital organs. These results reveal a crucial role of the Rap signal in the Notch-dependent T-ALL development and the progression.

The Notch signal is essential for thymic T-cell development1,2. Notch protein is synthesized as a large single peptide, which is later cleaved intracellularly at a heterodimerization (HD) domain (S1 cleavage) to generate the heterodimeric Notch receptor3. Upon engagement with specific ligands, the Notch receptor is activated through successive proteolytic cleavages at a juxtamembrane site (S2) followed by an intramembranous site (S3) mediated by Adam10 and γ-secretase complex, respectively, resulting in the release and nuclear translocation of Notch intracellular domain (NICD)4. In early T-cell progenitors (ETPs), Notch receptor is activated via Delta-like 4 (Dll4), which is expressed on thymic epithelial cells5. The Notch signal also plays a key role in the development of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL)6. More than 50% of human T-ALL cell lines show “activating” Notch1 mutations7, although more recent studies suggest that these mutations may not alone suffice for T-ALL development8,9,10.

We have reported that the Rap G protein signal also plays an important part in thymic T-cell development as well as T-ALL genesis11,12,13. The signal switch function of Rap is regulated positively by specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors such as C3G and negatively by GTPase-activating proteins represented by Sipa112. Impaired Rap activation in ETPs results in arrested thymic T-cell development, whereas deregulated Rap activation (Raphigh) remarkably enhances the Notch-dependent proliferation of ETPs11. Moreover, bone marrow transplantation (BMT) of Raphigh hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) results in the development of T-ALL13. Intriguingly, such T-ALL cells were dependent on the Notch signal and often showed characteristic Notch1 mutations similar to human T-ALL13, suggesting a functional crosstalk between the Rap and Notch signals.

In current study, we demonstrate that the Rap signal controls Notch activation in T-ALL cells by regulating proprotein convertase activity required for the maturation of Adam10 mediating the Notch processing. We further indicate that the sustained Notch activation in thymic Raphigh blast cells eventually results in the expression of Notch ligands, leading to the cell-autonomous Notch activation and systemic T-ALL progression.

Results

The Rap signal is required for Notch activation in T-ALL cell lines

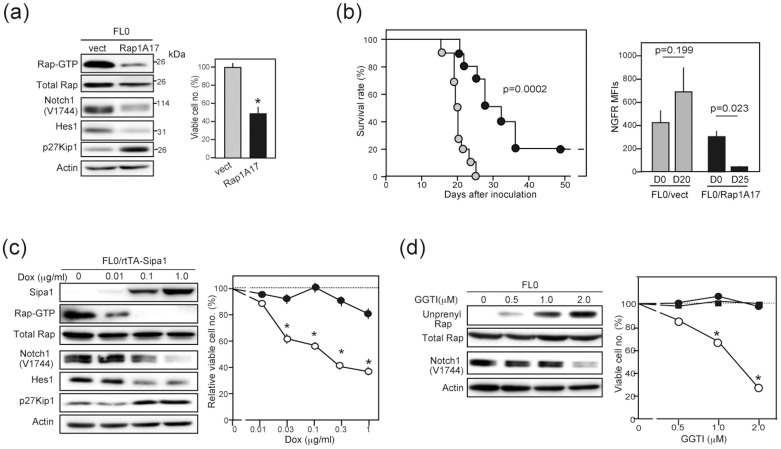

FL0 cell line derived from T-ALL by BMT of Raphigh HPCs expressed intact Notch receptors with no detectable Notch1 mutation and showed Notch-dependent proliferation (Figure S1). Retroviral transduction of dominant-negative Rap1 (Rap1A17) in FL0 cells causing a decrease of the Rap1-GTP resulted in a reduced expression of NICD and its target Hes1 (Figure 1a). Accordingly, the expression of p27Kip1, a target of Hes1-mediated repression14 was increased, and the proliferation was significantly reduced (Figure 1a). The FL0/Rap1A17 cells showed significantly compromised leukemogenic activity in scid mice, and 20% of the recipients remained free of leukemia, whereas all recipients of control FL0/vect cells died within 25 days (Figure 1b, left). Moreover, the leukemia cells developed in the recipients of FL0/Rap1A17 cells revealed significantly reduced expression of the retrovirus-driven NGFR (Figure 1b, right). Such an effect was not observed in the recipients of FL0/vect cells, suggesting a counter selection against FL0/Rap1A17high cells in vivo. We then transduced Rap1-specific GAP, Sipa1, in FL0 cells with a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible system. Induction of Sipa1 expression also resulted in the decreased NICD expression and cell proliferation in concordance with reduced Rap1-GTP levels in a Dox-dose dependent manner (Figure 1c). Furthermore, treatment of the FL0 cells with a geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor (GGTI)15, which inhibited the Rap prenylation required for membrane anchoring, also suppressed the NICD generation and cell proliferation at a dose-range that did not affect the proliferation of irrelevant leukemia cells (Figure 1d). Other T-ALL cell lines of mice and humans similarly showed significantly higher susceptibility to GGTI than leukemia cells of non-T-ALL types (Figure S2). The results suggest that the Rap signal plays an important role in sustaining Notch activation and proliferation of established T-ALL cell lines.

Figure 1. Attenuation of the Rap signal inhibits Notch activation and the proliferation of T-ALL cell lines.

(a) FL0/Rap1A17 and control FL0/vect cells were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. These cells were cultured at 3 × 104 cells/mL in triplicate, and the viable cell numbers were assessed on day 3. *; p < 0.01. (b) Survival rates of scid mice transplanted with FL0/vect (grey symbols) or FL0/Rap1A17 (solid symbols) cells (10 mice per group). Expression levels of the retrovirus-derived hNGFR in the BM of FL0/vect- and FL0/Rap1A17-recipients were analyzed at 20 and 25 days after the transplantation, respectively, in comparison with the original inoculants. The means of mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) in 3 recipients are indicated. (c) FL0/rtTA-Sipa1 cells were cultured for 3 days in the absence or presence of varying doses of Dox and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. FL0/rtTA-Sipa1 (open circles) and control FL0/rtTA (solid circles) cells were cultured in triplicate for 3 days in the absence or presence of Dox, and the viable cell numbers were assessed. *; p < 0.01. (d) FL0 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of GGTI for 2 days and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. FL0 (open circles), EL4 (closed circles), and P3U1 (closed squares) cells were cultured in triplicate with or without GGTI for 3 days, and the viable cell numbers were assessed. *; p < 0.01. Relevant parts of immunoblot images in (a), (c), and (d) were cropped from full-length blots shown in Figure S7.

The Rap signal controls Notch S2 processing by regulating intracellular Adam10 maturation

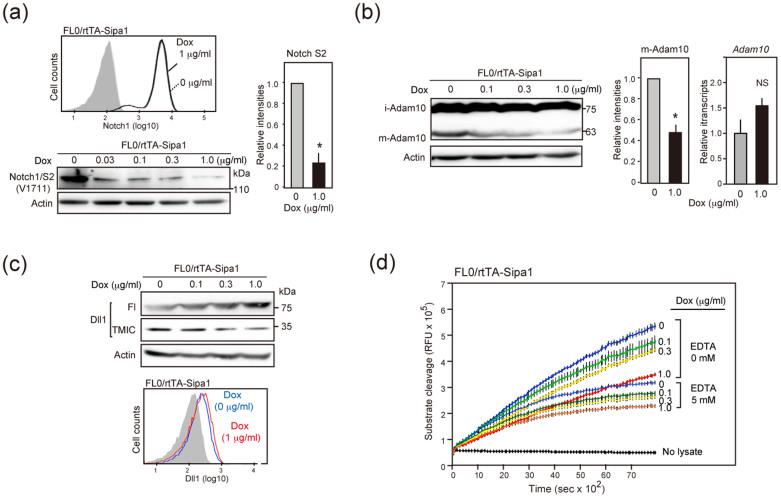

The conditional expression of Sipa1 in FL0 cells did not affect the cell surface expression of Notch1 (Figure 2a). However, analysis with Notch1-immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting with S2 (V1711)-specific antibody revealed that the Notch S2 product precedent to the NICD generation was also decreased by Sipa1 expression (Figure 2a). In T-ALL cells, Notch cleavage at S2 site is mediated by Adam1016, which maturates intracellularly via prodomain-cleavage of the immature form17. Sipa1 expression in FL0 cells caused a decrease of the mature form of Adam10 (m-Adam10) with barely affecting the immature form (i-Adam10) or the transcripts (Figure 2b). Because it is reported that membrane Dll1 is constitutively cleaved extracellularly by Adam1018, we also examined the effect of Sipa1 expression on Dll1. Induction of Sipa1 expression in FL0 cells resulted in the accumulation of unprocessed, full-length (Fl) Dll1 (85 kDa) with a concomitant decrease of the cleaved transmembrane and intracellular (TMIC) form (29 kDa); FACS analysis confirmed a slight yet clear increase in the cell surface Dll1 expression (Figure 2c). We next examined the proprotein convertase activity required for the Adam10 maturation19, with the use of a fluorescence-labeled synthetic substrate (Pyr-Arg-Thr-Lys-Arg-AMC)20. Although proprotein convertase activity requires Ca2+ 21,22, early-phase cleavage activity in the cell lysate tended to be resistant to EDTA and was probably attributed to other trypsin-like proteases. Sipa1 expression in FL0 cells rather preferentially inhibited the EDTA-sensitive late-phase activity (Figure 2d). The results suggest that the Rap signal regulates the activation of proprotein convertase activity required for the maturation of Adam10 mediating Notch S2 processing.

Figure 2. The Rap signal is involved in Notch S2 processing by sustaining Adam10 maturation via proprotein convertase activity.

(a) FL0/rtTA-Sipa1 cells were cultured in the absence (fine line) or presence (solid line) of Dox (1 μg/mL), and the surface expression of Notch1 was analyzed with flow cytometry. These cells were cultured with or without varying dosed of Dox for 3 days, and the lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Notch1 antibody followed by immunoblotting with S2-specific (V1711) antibody. The mean signal intensities of Notch S2 in 3 independent experiments are shown. *; p < 0.01. (b) FL0/rtTA-Sipa1 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of Dox for 3 days, and the lysates were immunoblotted with anti-Adam10 antibody. Adam10 transcripts were assessed with qRT-PCR in the aliquots of cells. The mean signal intensities of mature (m)-Adam10 and the relative transcripts in 3 independent experiments are shown. *; p < 0.01. NS; not significant. (c) The cells in (b) were immunoblotted and FACS analyzed with anti-Dll1 antibody. (d) FL0/rtTA-Sipa1 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of Dox for 3 days, and proprotein convertase activity of the cell lysates was assessed with the use of a fluorescence-labeled synthetic substrate in the presence or absence of EDTA. In (a), (b), and (c), relevant parts of immunoblot images were cropped from full-length blots shown in Figure S8.

Prenylation-mediated anchoring of the Rap1 at the Golgi-network is crucial for proprotain convertase activation

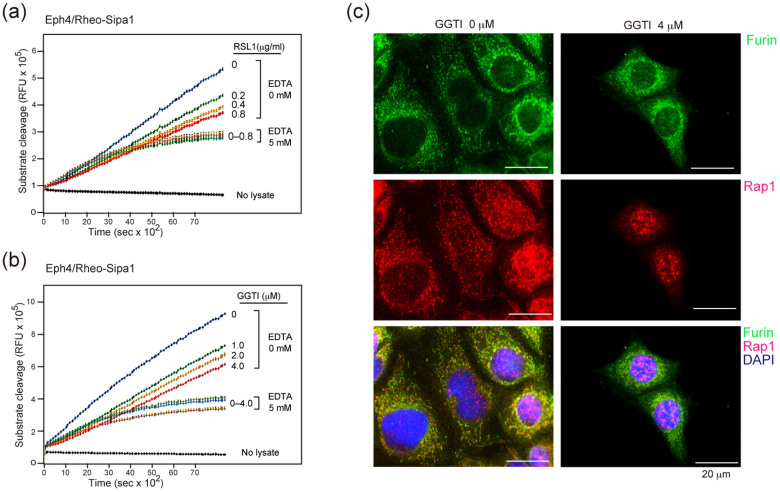

We then investigated the intracellular localization of the Rap1 and Furin, a main proprotein convertase. Because the analysis was rather difficult in small T-ALL cells with minimal cytoplasm, we made use of an epithelial Eph4 cell line to this end, whose Sipa1 expression could be conditionally induced with a Rheo-switch system (Eph4/Rheo-Sipa1) (Figure S3a). It was confirmed that the induction of Sipa1 expression in Eph4/Rheo-Sipa1 cells resulted in the decrease of late-phase, EDTA-sensitive proprotein convertase activity (Figure 3a). Treatment of Eph4/Rheo-Sipa1 cells with GGTI inhibiting the prenylation of Rap1 also caused a reduction of the proprotein convertase activity dose-dependently (Figure 3b, Figure S3b). In agreement with previous reports21,22, Furin was detected in the cytosol as small clusters enriched at the perinuclear region corresponding to the Golgi-network, and the Rap1 was distributed at the same regions to Furin, with additional localization in the nuclei in some cells (Figure 3c, left). After GGTI treatment, however, unprenylated Rap1 was barely detected in the cytosol any more and was localized mostly in the nuclei, whereas Furin localization was hardly affected (Figure 3c, right). The results suggest that the Rap1 anchoring at the Golgi-network membrane is crucial for the activation of proprotein convertases.

Figure 3. Prenylation-mediated anchoring of Rap1 to Golgi-network is required for the proprotein convertase activation.

(a, b) Eph4/Rheo-Sipa1 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of RSL1 (a) or GGTI (b) for 3 days, and the intracellular proprotein convertase activity was assessed with or without EDTA. (c) Eph/Rheo-Sipa1 cells were cultured in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 4 μM GGTI for 24 h and multi-color immunostained with the indicated antibodies.

Exogenous expression of mature Adam10 overcomes the Sipa1-induced growth inhibition of T-ALL cells

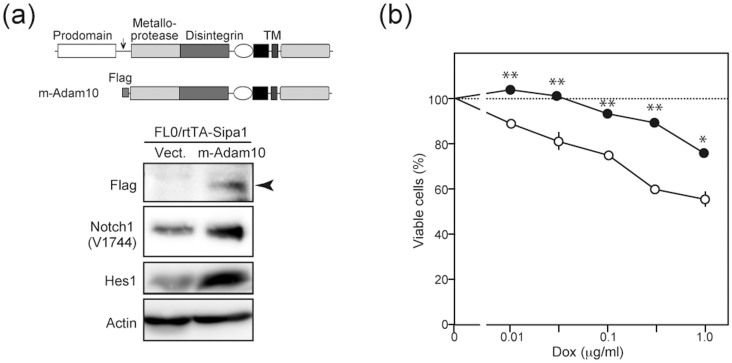

To confirm the role of Rap signal in Adam10 maturation, we expressed a mature form of Adam10 in FL0/rtTA-Sipa1 cells using pMSCV-hNGFR (MIN) retroviral vector (Figure 4a). The FL0/rtTA-Sipa1/m-Adam10 cells showed increased NICD and Hes1 expression compared with control FL0/rtTA-Sipa1/vect cells as anticipated (Figure 4a). We then cultured the cells in the absence or presence of Dox. The FL0/rtTA-Sipa1/m-Adam10 cells showed no or significantly less inhibition of the proliferation in the presence of Dox than FL0/rtTA-Sipa1/vect cells (Figure 4b). The results are consistent with the notion that the Rap signal is required for the Notch-dependent proliferation of T-ALL cells by promoting endogenous Adam10 maturation.

Figure 4. Exogenous expression of mature Adam10 overcomes Sipa1-induced growth inhibition of T-ALL cells.

(a) FL0/rtTA-Sipa1 cells were transduced with a MIN vector containing Flag-tagged m-Adam10 cDNA as illustrated or empry vector. Arrow indicates a cleavage site. The cells were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. (b) The FL0/rtTA-Sipa1/m-Adam10 (solid circles) and control (open circles) cells were cultured in the absence or presence of varying concentrations of Dox at 105 cells/mL for 3 days, and the viable cell numbers were assessed with Cell Titer Glo assay. The means and SEs of triplicate culture are indicated. *; p < 0.005, **; p < 0.001. The experiments were repeated three times with essentially similar results. In (a), relevant parts of immunoblot images were cropped from full-length blots shown in Figure S9.

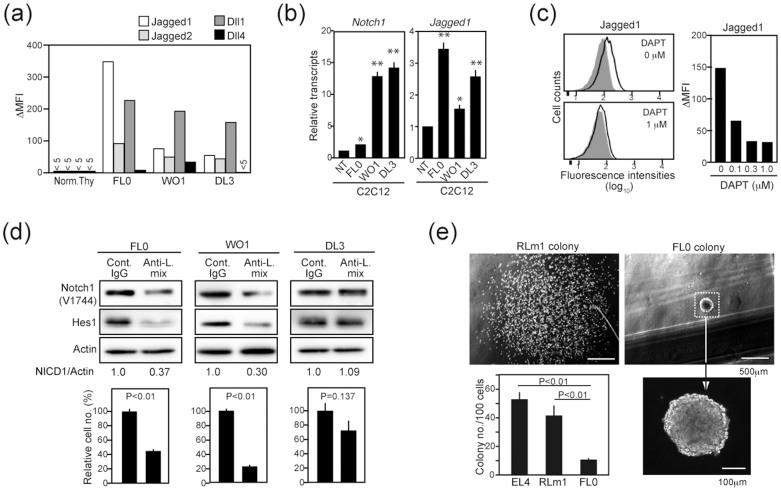

Expression of Notch ligands and their involvement in the cell-autonomous Notch activation of T-ALL cell lines

Because Notch1 receptor in FL0 cell line showed no mutation, the initiation of Notch processing might be expected to depend on the ligand engagement. We therefore examined the expression of Notch ligands on T-ALL cell lines. FACS analysis revealed that Notch-dependent T-ALL cell lines including FL0 variably expressed Jagged1, Jagged2 and Dll1, but rarely Dll4, although normal thymocytes expressed none of them (Figure 5a). Moreover, co-culture of these T-ALL cell lines with Notch ligand–responsive C2C12 myoblast cells induced significant expression of Notch1 and Jagged1 in the C2C12 cells (Figure 5b), indicating that the ligands were functional. The expression of Jagged1 was abrogated in the presence of a γ-secretase inhibitor (DAPT) and was suggested to be dependent on the Notch signal (Figure 5c). To examine the possible involvement of ligands in cell-autonomous Notch activation, we cultured the T-ALL cell lines in the presence of the mixture of monoclonal antibodies against Jagged1, Jagged2 and Dll1. The Notch activation and proliferation of FL0 and WO1 cell lines bearing intact ligand-binding Notch1 were significantly inhibited in the presence of the antibody mixture, anti-Dll1 antibody being the most effective among them for FL0 cells (Figure 5d, Figure S1, Figure S4). In contrast, the antibody mixture showed no significant effect on the Notch activation and proliferation of DL3 cell line that lacked the ligand-binding region of Notch1 (Figure 5d, Figure S1). Moreover, despite the robust proliferation in liquid culture, the FL0 cells showed a remarkably poor clonogenic growth in semisolid culture compared with other leukemia cell lines, and infrequently developed small colonies were tightly packed (Figure 5e), suggesting the requirement for intimate cell–cell contact for the optimal proliferation. The results suggest that the Notch ligands expressed on T-ALL cells contribute to the cell-autonomous Notch activation.

Figure 5. Expression and function of Notch ligands in T-ALL cell lines.

(a) Expression of Notch ligands was analyzed with FACS in normal thymocytes and T-ALL cell lines. The ΔMFIs are shown. (b) Normal thymocytes (NT) (1 × 107) or T-ALL cells (1 × 106) were co-cultured with C2C12 cell monolayers in triplicate for 2 days, and the transcripts of Notch1 and Jagged1 in C2C12 cells were determined with qRT-PCR. *; p < 0.05; **; p < 0.01. (c) FL0 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of DAPT and analyzed for the expression of Jagged1 with FACS. Shaded areas indicate the staining with control antibody. ΔMFIs at varying concentrations of DAPT are indicated. (d) T-ALL cell lines were cultured in the presence of control IgG or mixtures of monoclonal antibodies against Jagged1, Jagged2 and Dll1 (60 μg/mL each) for 1 day and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Relative intensities of NICD to actin are indicated. Aliquots of the cells were cultured for 5 days, and the viable cell numbers were determined in triplicate culture. (e) FL0 and T-lymphoma (EL4, RLm1) cell lines were cultured in methylcellulose medium (100 cells/dish) in triplicate for 7 days, and the colony numbers were counted. Images of typical colonies of RLm1 and FL0 cells are shown. In (a), relevant parts of immunoblot images were cropped from full-length blots shown in Figure S10.

Notch ligand expression in primary T-ALL cells correlates with the systemic leukemia invasion in vivo

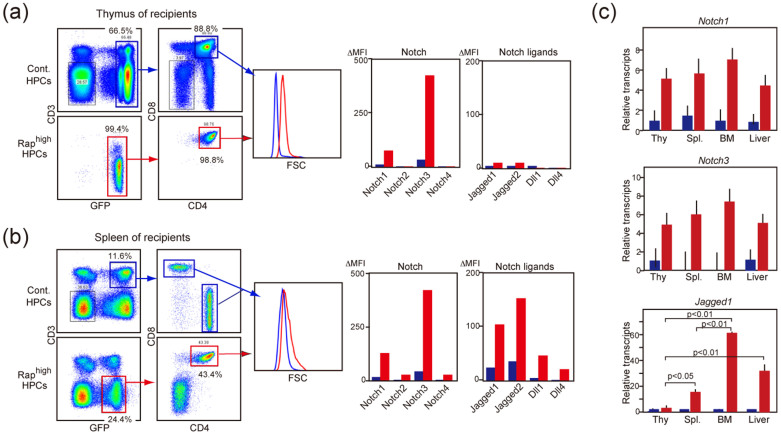

To validate the significance of Notch-dependent ligand expression during T-ALL development in vivo, we performed BMT of Raphigh HPCs. As reported previously13, the Raphigh HPCs caused highly aggressive T-ALL eventually involving most vital organs in the BMT recipients. The thymi of Raphigh HPC-recipients were remarkably enlarged in 15 weeks after BMT, mostly consisting of blastic immature (CD3− CD4+ CD8+) T cells, whereas control HPCs repopulated the thymi with normal T cell differentiation (Figure 6a). The thymic Raphigh blast cells showed no detectable expression of any Notch ligand on the surface, although these cells exhibited markedly enhanced expression of Notch1 and Notch3 compared with control repopulating thymocytes (Figure 6a). In contrast, the CD3− CD4+ CD8+ blast cells that invaded the spleen significantly expressed cell-surface Notch ligands in addition to the enhanced Notch1/3, whereas the T cells derived from control HPCs barely did so (Figure 6b). Moreover, the T-ALL cells that invaded other vital organs such as BM and liver showed even more Jagged1 transcripts than those in the spleen, although the increase in Notch1/3 transcripts was comparable (Figure 6c). These results suggest that the expression of Notch ligands in the T-ALL cells coincides with their extrathymic spreading and invasion to peripheral vital organs in vivo.

Figure 6. Expression of Notch ligands in primary T-ALL cells invading extrathymic organs.

(a, b) Sipa1−/− BM HPCs infected with empty (blue lines and columns) or C3G-F-containing retrovirus (red lines and columns) were transplanted into 8.5 Gy γ-ray-irradiated mice. After 15 weeks, the cells from the thymus (a) and the spleen (b) were multicolor-analyzed with the indicated antibodies. The cell sizes (FSC) and expression of Notch and ligands (ΔMFIs) in GFP+ T cells are shown. Essentially similar results were obtained in 3 independent recipients. (c) GFP+ T cells were sorted from the indicated organs of Raphigh HPC (red columns) and control HPC (blue columns) recipients, and the transcripts of indicated genes were determined with qRT-PCR. The means and SEs of 3 recipients are shown.

Discussion

In humans, meta-analyses of gene expression (NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus, http://lifesciencedb.jp/geo/) show that the negative Rap regulator SIPA1 is one of the most prominently under-expressed genes in T-ALL (Figure S5). Chromosomal translocation causing a fusion of NUP98 and RAP1GDS1 encoding Rap1 guanine nucleotide dissociation factor was also reported in a case of human T-ALL23. In mice, we reported that BMT of Sipa1−/− C3G-F+ (Raphigh) HPCs invariably resulted in the development of Notch-dependent T-ALL in a cell-autonomous manner13. Although these results suggest the involvement of the Rap signal in T-ALL, the mechanistic basis remained unknown.

Our current study indicated that specific attenuation of the Rap signal in a Notch-dependent T-ALL cell line by the expression of Rap1A17 or Sipa1 caused significantly compromised Notch activation and proliferation. Current results revealed that the Rap signal attenuation resulted in the decrease of an intracellular mature form of Adam10 and accordingly the reduced Notch S2 processing precedent to the NICD generation16. Adam10 has multiple targets in various cell types19, and Adam10-mediated extracellular cleavage of Dll1 was also reduced by Sipa1 expression in T-ALL cells. Maturation of Adam10 is achieved by proprotein convertases such as Furin that proteolytically remove a prodomain of Adam10 in the Golgi-network before a mature form is transported to the plasma membrane17, and artificial inhibition of the proprotein convertase activity may result in the surface expression of the immature form of Adam1024.

The majority of Rap1 is localized at the perinuclear Golgi-network25, and our current results indicated that the inhibition of the Rap1 prenylation with GGTI caused a dislodgement of the Rap1 from the Golgi-network to the nuclei. Nuclear Rap1 sporadically detected in untreated Eph4 cells may represent unprenylated Rap1. The Rap1 dislodgement with GGTI was associated with the significant decrease of proprotein convertase activity. The convertase activity is activated by auto-cleavage of a prodomain and is regulated by various factors such as H+ and Ca2+ concentrations in the Golgi-network21,22. Thus, it is suggested that the Rap signal at the Golgi-network membrane regulates the activation of proprotein convertases inside the Golgi-network. Although Furin also mediates intracellular Notch S1 processing, cell surface Notch expression was scarcely affected by the Rap signal inhibition, probably due to the expression of unprocessed Notch26. The effects of GGTI can be broad in various cell types, however Notch-dependent T-ALL cell lines of humans and mice commonly showed much higher susceptibility to GGTI than other types of leukemia cells, suggesting that the Rap signal-mediated regulation of Adam10 maturation is crucially important in T-ALL cells. To support the notion, the exogenous expression of a mature form of Adam10 significantly overcame the Sipa-1-induced proliferation inhibition of FL0 T-ALL cells. It is also noted that T-cell conditional deletion of Adam10 causes arrested thymic T-cell development, similar to T-cell conditional Sipa1 overexpression13,27.

Although deregulated Rap activation in normal ETPs induces remarkably enhanced Notch-mediated proliferation, the effect is dependent on the Notch ligands provided by stroma cells, and thus the enhanced Rap signal alone is incapable of bypassing the ligand requirement11. How Notch activation occurs cell-autonomously in T-ALL cells without other ligand-donor cells has been an open question, and several mechanisms have been reported. Activating Notch1 mutations, particularly at an HD region, may result in an intrinsic increase of spontaneous S2 cleavage28. It was also reported that unique Notch isoforms with spontaneous S2 cleavage are generated via cryptic Notch1 promoters in murine T-ALL models29. Our current results indicated that T-ALL cell lines express functional Notch ligands, and that the Notch activation and proliferation of those expressing intact Notch1 are significantly inhibited by the mixture of antibodies against the ligands. As expected, those of a T-ALL cell line with Notch1 receptor lacking the ligand-binding region were unaffected by the antibodies despite the ligand expression. The expression of Jagged1 in the T-ALL cells was dependent on the Notch signal, apparently forming an auto-amplification circuit as reported in human macrophages30. The results provide another mechanism for cell-autonomous Notch activation in T-ALL cells, in which Notch receptor engagement is achieved via a paracrine manner among the T-ALL cells, being reminiscent of “lateral” Notch activation31. Requirement of the intimate cell-cell contacts for the optimal proliferation of T-ALL cells is consistent with the notion.

Using a T-ALL model by the BMT of Rap1high HPCs13, we also investigated the Notch ligand expression in the primary T-ALL cells in vivo. The results indicated that the initial intrathymic blast cells showed remarkably enhanced Notch expression but barely expressed Notch ligands. In contrast, the leukemic cells that spread and invaded into peripheral organs such as spleen, BM and liver significantly expressed the ligands on the cell surface with a remarkable increase of the transcripts. The possible mechanisms leading to the ligand expression under sustained Notch signaling in T-ALL cells remain to be investigated. A recent report indicates that a Toll-like receptor signal induces Notch ligand expression in collaboration with the Notch signal in macrophages26. We reported that, unlike Sipa1−/− C3G-F+ HPCs, WT C3G-F+ HPCs caused a remarkable increase in the oligoclonal thymic blast cells with little systemic leukemia, implying that the Rap signal strength might influence the leukemic spread of blast cells12. In any case, it may be suggested that the subclones of thymic balst cells expressing Notch ligands have an apparent advantage for the survival and proliferation outside the thymic tissues, owing to the liberation from the requirement of other ligand-donor cells. We thus propose that the Notch ligand expression may represent one of the early steps toward systemic T-ALL progression (Figure S6). It remains to be seen when and where the characteristic Notch mutations take place in the T-ALL-genic process, however Notch mutations leading to the Notch activation bypassing the ligand requirement28 as well as other secondary genetic changes bypassing the Notch signaling per se32 may further aggravate the disease (Figure S6).

Our current results disclose a mechanistic link between the Rap signal and Notch activation in T-ALL cells and may provide a novel strategic clue for therapeutic control of human T-ALL.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6) and scid mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan) and CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan), respectively; Sipa1−/− mice were described previously33. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions at the Institute of Laboratory Animals, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, according to the University's guidelines for the treatment of animals. All protocols were approved by the committee on the ethics of animal experiments of Kyoto University (Permit Number: MedKyo14049). All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Cell lines

Murine T-ALL cell lines were reported previously13,34, and human T-ALL cell lines were obtained from RIKEN BRC, Saitama, Japan. FL0/rtTA-Sipa1 and FL0/RapA17 cells were established by the transduction of FL0 cells with pRetroX-Tight-Sipa1 plus pRetroX-Tet-On Advanst vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) and pMSCV- hNGFR (MIN)-RapA1711, respectively. Because the addition of tag to RapA17 cDNA abrogated the dominant negative effect, untagged RapA17 cDNA was used. Mature form (m-) of Adam10 cDNA truncated at the 7 residue-upstream Metalloprotease/Distintegrin domain was cloned from FL0 cells with Flag-tagged at the 5′-terminus, and was integrated into a MIN retrovirus vector. FL0/rtTA-Sipa1 cells were infected with the MIN/m-Adam10. The mammary epithelial Eph4 cell line was transduced with pNEBRX1-Hygro-fSpa-1Thr and pNEBR-R1 (New England BioLabs Inc., Beverly, MA) (Eph4/Rheo-Sipa1). The myoblastic cell line (C2C12) was provided by Dr. R. Kageyama, Institute for Virus Research, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan. Cell viability was assessed with Cell Titer Glo assay (Promega, Madison, WI).

Reagents

The γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) (DAPT, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), the geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor (GGTI) (GGTI298, Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK), and the Rheo-switch ligand (RSL1, New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, MA) were obtained commercially.

Flow cytometry

Multicolor flow cytometry analysis was performed with FACSCalibur flow cytometers (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Antibodies included biotin-conjugated anti-Notch1, anti-Notch2, anti-Notch3, anti-Notch4, anti-Jagged1, anti-Jagged2, anti-Dll1, anti-Dll435, PE-conjugated anti-mouse Adam10 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and biotin-conjugated anti-human nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR) antibodies (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). PE/Cy7-conjugated and APC-conjugated streptavidin (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) served as second reagents.

Immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation, and pull-down assay

Cells were lysed with lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 0.5% Triton X-100, protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and subjected to immunoblotting. Antibodies included anti-Notch1 (C-20), anti-actin (I-19), anti-unprenylated Rap1 (C-17), anti-Dll1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-Hes1, anti-p27Kip1 (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA), anti-Sipa133, anti-Adam10 (ab39180) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and anti-Notch1/Val1744 (D3B3) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) antibodies. For detection of the S2 product of Notch1, the lysate was immunoprecipitated with anti-Notch1 (C-20) and protein A–conjugated beads and then immunoblotted with S2-cleavage (V1711) specific antibody as reported previously16. Rap1GTP was assessed by a pull-down assay.

Immunostaining

Cells grown on cover glasses were fixed with chilled 100% methanol, blocked in PBS containing 1% BSA (w/v), and then incubated with primary antibodies, followed by fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. The primary antibodies used were mouse anti-mouse Furin (Enzo Life Science, Farmingdale, NY) and rabbit anti-Rap1A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Second antibodies were Alexa-Fluor-488- or Cy3-conjugated antibodies. Nuclei were stained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Cover glasses were mounted on slides and examined by Axiovert 200M inverted fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss, New York, NY).

Notch ligand assay

Notch ligand activity was assessed as reported by Luo et al.36. Briefly, normal thymocytes or T-ALL cells were cultured with C2C12 cell monolayers. Two days later, C2C12 cells were recovered by depleting CD45+ cells with rat anti-CD45 magnetic beads (Daynabeads, Life Technologies, Oslo, Norway), and Notch1 and Jagged1 transcripts were assessed with qRT-PCR.

Proprotein convertase assay

Cells were lysed with reaction buffer (500 mM HEPES, pH 7.0 2.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol), and the lysates were incubated in black opaque 96-well plates (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA) containing 0.1 mM Furin fluorogenic substrate (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) in the absence or presence of 5 mM EDTA. Fluorogenic intensity was measured with excitation at 355 nm and emission at 450 nm, 1 sec in every 1.5 min.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNAs were isolated with TRIzol Reagent and treated with DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and cDNAs were synthesized with SuperScript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) on a LightCycler480 instrument (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The relative transcripts levels were normalized to those of Gapdh. Primers were as follows; Notch1, sense; gcagatgctcagggtgtctt, antisense; agttgtgccatcatgcattc, Notch3, sense; catcaaccgttatgactgtgtct, antisense; ctcattgaatctccacgttgc, Jagged1, sense; agtggctgggtctgttgct-, antisense; cattgttggtggtgttgtcctc, Gapdh, sense; tgttcctacccccaatgtgt, antisense; tgtgagggagatgctcagtg-3′, Adam10, sense; gggaagaaatgcaagctgaa, antisense; ctgtacagcagggtccttgac.

Retroviral infection and BMT

Isolation of BM Lin− HPCs and retroviral expression of C3G-F were performed as described before13. GFP+ cells were sorted with a FACSAria II (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and injected into 8.5 Gy γ-ray–irradiated B6 mice together with normal rescue BM cells.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test.

Author Contributions

K.D., T.I., C.K. and J.I. performed experiments and collected data; H.Y. and M.V. developed and provided antibodies; Y.A. and Y.H. helped gene construction and immunostaining, respectively; and N.M. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. A. Sekine and Dr. E. Nakamura for help with genomic sequencing and database analysis. We also thank Dr. K. Nakayama for helpful discussion on proprotein convertases and Dr. M. Hikita for helping cDNA cloning. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports and Technology of Japan to N.M. and ERC-St grant 208259 to M.V.

References

- Zuniga-Pflucker J. C. T-cell development made simple. Nature Rev. Immunol. 4, 67–72 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard I., Fang T. & Pear W. S. Regulation of lymphoid development, differentiation, and function by the Notch pathway. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23, 945–974 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logeat F. et al. The Notch1 receptor is cleaved constitutively by a furin-like convertase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 95, 8108–8112 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R. & Ilagan M. X. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell 137, 216–233 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozumi K. et al. Delta-like 4 is indispensable in thymic environment specific for T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 205, 2507–2513 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vlierberghe P. & Ferrando A. The molecular basis of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 3398–3406 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng A. P. et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science 306, 269–271 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang M. Y. et al. Leukemia-associated NOTCH1 alleles are weak tumor initiators but accelerate K-ras-initiated leukemia. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3181–3194 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch U. & Radtke F. Notch in T-ALL: new players in a complex disease. Trends Immunol. 32, 434–442 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobry C., Oh P. & Aifantis I. Oncogenic and tumor suppressor functions of Notch in cancer: it's NOTCH what you think. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1931–1935 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kometani K. et al. Essential role of Rap signal in pre-TCR-mediated beta-selection checkpoint in alphabeta T-cell development. Blood 112, 4565–4573 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minato N. & Hattori M. Spa-1 (Sipa1) and Rap signaling in leukemia and cancer metastasis. Cancer Sci. 100, 17–23 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. F. et al. Development of Notch-dependent T-cell leukemia by deregulated Rap1 signaling. Blood 111, 2878–2886 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K. et al. Hes1 directly controls cell proliferation through the transcriptional repression of p27Kip1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4262–4271 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzat A. C., Brady D. C., Fiordalisi J. J. & Cox A. D. Using inhibitors of prenylation to block localization and transforming activity. Methods Enzym. 407, 575–597 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tetering G. et al. Metalloprotease ADAM10 is required for Notch1 site 2 cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 31018–31027 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders A., Gilbert S., Garten W., Postina R. & Fahrenholz F. Regulation of the alpha-secretase ADAM10 by its prodomain and proprotein convertases. FASEB J. 15, 1837–1839 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Six E. et al. The Notch ligand Delta1 is sequentially cleaved by an ADAM protease and gamma-secretase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 100, 7638–7643 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards D. R., Handsley M. M. & Pennington C. J. The ADAM metalloproteinases. Mol. Aspects Med. 29, 258–289 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne G. L. & Grainger D. J. Development and characterisation of an assay for furin activity. J. immunol. Meth. 364, 101–108 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G. Furin at the cutting edge: from protein traffic to embryogenesis and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 753–766 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. D., VanSlyke J. K., Thulin C. D., Jean F. & Thomas G. Activation of the furin endoprotease is a multiple-step process: requirements for acidification and internal propeptide cleavage. EMBO J. 16, 1508–1518 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey D. J., Nicola M., Moore S., Peters G. B. & Dobrovic A. The (4; 11) (q21; p15) translocation fuses the NUP98 and RAP1GDS1 genes and is recurrent in T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 94, 2072–2079 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey R. M., Blusztajn J. K. & Slack B. E. Surface expression and limited proteolysis of ADAM10 are increased by a dominant negative inhibitor of dynamin. BMC Cell Biol. 12, 20 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K., Kanemura H., Satoh T. & Kataoka T. Identification of a novel domain of Ras and Rap1 that directs their differential subcellular localizations. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22664–22673 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J. T. et al. DSL ligand endocytosis physically dissociates Notch1 heterodimers before activating proteolysis can occur. J. Cell Biol. 176, 445–458 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L. et al. ADAM10 is essential for proteolytic activation of Notch during thymocyte development. Int. Immunol. 20, 1181–1187 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki M. J. et al. Leukemia-associated mutations within the NOTCH1 heterodimerization domain fall into at least two distinct mechanistic classes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 4642–4651 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-del Arco P. et al. Alternative promoter usage at the Notch1 locus supports ligand-independent signaling in T cell development and leukemogenesis. Immunity 33, 685–698 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldi J. et al. Autoamplification of Notch signaling in macrophages by TLR-induced and RBP-J-dependent induction of Jagged1. J. Immunol. 185, 5023–5031 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas S., Matsuno K. & Fortini M. E. Notch signaling. Science 268, 225–232 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomero T. et al. Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia. Nature Med. 13, 1203–1210 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida D. et al. Myeloproliferative stem cell disorders by deregulated Rap1 activation in SPA-1-deficient mice. Cancer cell 4, 55–65 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. S., Ishimoto A., Honjo T. & Yanagawa S. Murine leukemia provirus-mediated activation of the Notch1 gene leads to induction of HES-1 in a mouse T lymphoma cell line, DL-3. FEBS Lett. 455, 276–280 (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi A., Sekine C. & Yagita H. Expression of Notch receptors and ligands on immature and mature T cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 418, 799–805 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B., Aster J. C., Hasserjian R. P., Kuo F. & Sklar J. Isolation and functional analysis of a cDNA for human Jagged2, a gene encoding a ligand for the Notch1 receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 6057–6067 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information