Abstract

Soluble amyloid β-protein (Aβ) oligomers, the main neurotoxic species, are predominantly formed from monomers through a fibril-catalyzed secondary nucleation. Herein, we virtually screened an in-house library of natural compounds and discovered brazilin as a dual functional compound in both Aβ42 fibrillogenesis inhibition and mature fibril remodeling, leading to significant reduction in Aβ42 cytotoxicity. The potent inhibitory effect of brazilin was proven by an IC50 of 1.5 ± 0.3 μM, which was smaller than that of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate in Phase III clinical trials and about one order of magnitude smaller than those of curcumin and resveratrol. Most importantly, it was found that brazilin redirected Aβ42 monomers and its mature fibrils into unstructured Aβ aggregates with some β-sheet structures, which could prevent both the primary nucleation and the fibril-catalyzed secondary nucleation. Molecular simulations demonstrated that brazilin inhibited Aβ42 fibrillogenesis by directly binding to Aβ42 species via hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding and remodeled mature fibrils by disrupting the intermolecular salt bridge Asp23-Lys28 via hydrogen bonding. Both experimental and computational studies revealed a different working mechanism of brazilin from that of known inhibitors. These findings indicate that brazilin is of great potential as a neuroprotective and therapeutic agent for Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, is characterized by cerebral extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles1. It is estimated that there were 36 million people living with the dementia worldwide in 2010, increasing to 115 million by 2050 as a result of an increasing human lifespan. Although the precise aetiology of AD is still not fully understood owing to its complexity, recent advances have demonstrated that amyloid β-protein (Aβ) aggregation is a crucial event in the pathogenesis of AD2. Early reports indicated that amyloid fibrils were the cause of AD, but recent studies found that soluble Aβ oligomers are the main neurotoxic agents3,4,5. It has been suggested that Aβ monomers aggregate into oligomers, protofibrils and fibrils in sequence via a primary nucleation mechanism. Thus, the particular attention has been devoted to seeking inhibitors to prevent Aβ aggregation. Recent experimental evidence showed that the toxic oligomeric species are predominantly formed from monomers through a fibril-catalyzed secondary nucleation after a critical concentration of amyloid fibril has been exceeded6,7. Furthermore, it has been known that amyloid plaques including fibrils begin to form before symptoms developing8. Therefore, an attractive therapeutic strategy for AD is to find difunctional agents that can prevent the aggregation of Aβ and remodel the preformed fibrils at the same time, leading to the suppression of both the primary nucleation pathway and the fibril-catalyzed secondary nucleation pathway.

Up to now, many substances have been reported to prevent Aβ aggregation and reduce its associated cytotoxicity, such as organic molecules9,10, peptides11,12, antibodies13,14, and nanoparticles15. Of them, organic molecules have received special interest16. The organic molecules are categorized into three groups according to their working mechanisms: stabilizing Aβ monomers, accelerating Aβ fibrogenesis and modulating Aβ aggregation pathway. For example, (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) binds Aβ species and redirects them into off-pathway and nontoxic oligomers17. In contrast, the orcein-related molecule O4 promotes the conversion of toxic oligomers into nontoxic β-sheet-rich amyloid fibrils18.

Recently, particular attention has been paid to natural compounds due to the ease of structural modification, druggability features, and low cytotoxicity. Some organic molecules extracted from herbs have been found to prevent the aggregation of Aβ and alleviate its associated cytotoxicity19. For example, tanshinones, extracted from Chinese herb Danshen, was found to inhibit the aggregation of Aβ, disaggregate fibrils and reduce Aβ-induced cytotoxicity20. Although a number of organic compounds have been found to be effective inhibitors, none of them has been used for the clinical treatment of AD. More effective small molecular inhibitors are urgently needed.

In this work, brazilin, a natural compound extracted from Caesalpinia sappan, was virtually screened from our in-house library using docking simulation methods. Then, its inhibitory effect on the fibrillogenesis and cytotoxicity of Aβ42, remodeling effect on mature Aβ42 fibrils and molecular interactions with Aβ were studied systematically using biochemical, biophysical, cell biological and molecular simulation methods.

Results

Virtual screening of Aβ aggregation inhibitors

In order to find effective inhibitors of Aβ aggregation, an in-house library containing over 600 natural compounds was first constructed in our laboratory. Then, a virtual screening method was performed to screen the library using the docking program FlexX/SYBYL. Currently, there are five scoring functions (i.e., F_score, G_score, PMF_score, D_score and Chemscore) to rank the affinity between ligands and the target protein in SYBYL. We firstly validated which scoring functions could be used as the criterion to select potential inhibitors from the library. A widely accepted method, enrichment curve21, was used to identify the appropriate scoring functions. Thirty-six Aβ aggregation inhibitors reported in literature (Table S1) and all of the compounds in the library were docked to fibrillar Aβ17–42 pentamer. Figure S1 shows that the enrichment curves of the five scoring functions and the diagonal line represents a random classification. It is clear that the three scoring functions of F_score, Chemscore and D_score could effectively enrich the known inhibitors from the library when top 10% of the compounds were selected as inhibitors using these scoring functions. Therefore, ranking top 10% using the three scoring functions was used to screen effective inhibitors from the library and seven compounds were selected (Table S2). It is known that central nervous system drugs should typically have certain physicochemical and structural features in their molecular weights, hydrophobicity, etc. For example, Pajouhesh et al.22 have found that the central nervous drugs with logP less than 3 penetrated easily through blood-brain barrier (BBB) and showed good intestinal permeability. Therefore, two compounds (i.e., bicuculline and brazilin) with logP less than 3 were chosen to be the candidate inhibitors of Aβ aggregation (see Table S3).

Brazilin inhibits Aβ42 fibrillogenesis and reduces Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity

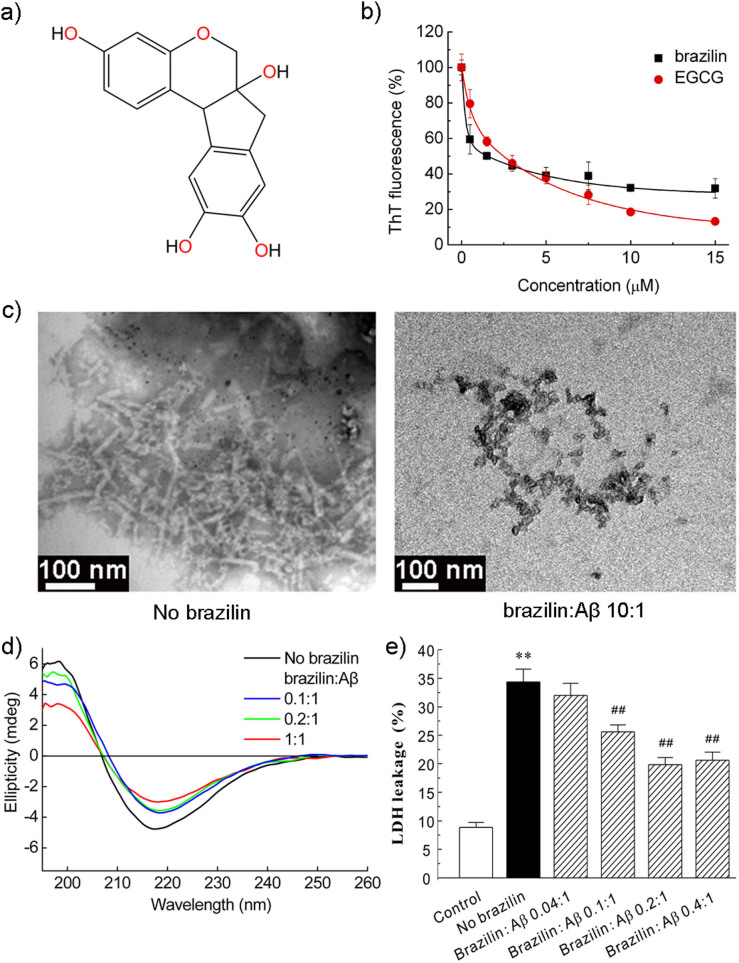

To examine the inhibitory effects of the two candidate compounds on Aβ42 fibrillogenesis, Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay was carried out. The ThT fluorescence signals of Aβ42 species after incubation with the two compounds for 30 h were monitored and shown in Figure S2. The inhibition efficiencies of the two compounds were monitored by measuring the fluorescence signal with respect to that of pure Aβ42 aggregates without inhibitors (100%). From Figure S2, it was observed that both the compounds were capable of inhibiting Aβ42 fibrillogenesis, while brazilin had stronger inhibitory potency than bicuculline. Therefore, brazilin was selected as a potent inhibitor against Aβ self-assembly for further study (see chemical structure in Figure 1a). To better quantify the inhibitory effect of brazilin on Aβ42 aggregation, the dose-dependent inhibitory effect of brazilin on Aβ42 fibrillogenesis was determined and shown in Figures 1b and S3. The well-known powerful inhibitor, EGCG, which is in Phase III clinical trial for treating AD (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov), was chosen to compare with brazilin for their inhibitory capacities. It was evident that brazilin had a marked inhibitory potency on Aβ42 fibrillogenesis with an IC50 of 1.5 ± 0.3 μM, which was smaller than that of EGCG (IC50 ~ 2.4 ± 0.4 μM). Although the inhibitory potency of EGCG at high concentrations was stronger than brazilin (Figure 1b), the stronger inhibition effect of brazilin at lower concentrations was considered more favorable because it would be difficult for the compounds to reach very high concentrations in brain.

Figure 1. Inhibition of Aβ42 fibrillogenesis and reduction of Aβ42 cytotoxicity by brazilin.

(a) Structural formula of brazilin. (b) ThT fluorescence of Aβ42 (25 μM) aggregates after incubation with various concentrations of brazilin or EGCG for 24 h. See method section for more details. The ThT fluorescence of Aβ42 aggregates without an inhibitor was defined as 100%. The inhibitory potency of brazilin represents a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 1.5 ± 0.3 μM, comparing with 2.4 ± 0.4 μM of EGCG. (c) TEM images of Aβ42 in the absence (left) and presence (right) of brazilin (brazilin to Aβ42 ratio, 10:1) after 10 h incubation. (d) The far-UV circular dichroism spectra of Aβ42 incubated for 24 h in the absence and presence of different concentrations of brazilin. (e) Inhibitory effect of brazilin on the cytotoxicity induced by Aβ42 aggregation. Aβ42 monomer (25 μM) was co-incubated at 37°C for 24 h with or without brazilin, and then added to SH-SY5Y cells. After 48 h treatment, cytotoxicity was evaluated using LDH leakage assay. All values represent means ± s.d. (n = 3). ** p < 0.01, compared to control group. ## p < 0.01, compared to Aβ42-treated group.

Then, we investigated the effect of brazilin on the ultrastructure of Aβ42 aggregates by TEM. In the absence of brazilin, the formation of predominant fibrillar structures was observed, but brazilin at a molar ratio of 10:1 to Aβ obviously inhibited fibril formation in favor of granular aggregates (Figure 1c and S4). Therefore, brazilin effectively inhibited Aβ42 fibril formation, supporting the results of the preceding ThT assays. Then, we analyzed the brazilin-induced aggregates using size exclusion chromatography (SEC). It was found that there were two elution peaks (Figure S5a). The first peak eluted at ~7.5 mL was relatively large soluble aggregates with molecular weight of above 70 kDa, and the second peak at ~15 mL was corresponding to monomeric Aβ, consistent with the previous study23. Moreover, the first peak was enriched with increasing brazilin (Figure S5b), indicating that the brazilin-induced aggregates were some species with molecular weights above 70 kDa.

Previous studies have proven that the formation of β-sheet-rich structure is a crucial early step in amyloidogenesis and on-pathway Aβ fibrils have a characteristic cross-β-sheet conformation24. In order to probe the effect of brazilin on the conformational conversion of Aβ42, time-dependent circular dichroism (CD) spectra of the protein in the presence and absence of brazilin were analyzed (Figures 1d and S6). It was found that the initial secondary structure of Aβ42 was random coil with a major negative peak between 200 and 210 nm (Figure S6a). Upon protein aggregation, this peak diminished gradually and a strong positive peak around 195 nm and a negative band around 216 nm appeared (Figure 1d). It indicates that Aβ42 converted from its initial random coil to a β-sheet structure, consistent with the previous study25. However, the typical CD spectrogram of β-sheet conformation was also observed in the presence of brazilin, although the values of the peak and valley had slightly changed with increasing brazilin (Figure 1d).

Previous studies have demonstrated that toxic on-pathway Aβ oligomers can be specifically detected with a conformation-specific antibody A1126. In order to examine whether the formation of such amyloid oligomers was inhibited by brazilin, the time-dependent dot blot assays using antibodies A11 and 6E10 were carried out and shown in Figure S7. It was evidenced that A11-immunoreactive oligomers were observed during the whole aggregation process in the absence of brazilin. However, the formation of on-pathway oligomers was efficiently suppressed by brazilin (Figure S7a), demonstrating that brazilin-induced Aβ42 aggregates were structurally different from the toxic amyloid oligomers described previously. Using the control antibody 6E10, which recognizes Aβ independently of its conformations, both brazilin-treated and untreated Aβ42 were detected (Figure S7b). These results demonstrated that Aβ42 aggregates modulated by brazilin were structurally distinct from the toxic oligomers, despite the presence of some β-sheet structures.

To examine the ability of brazilin to inhibit Aβ42-induced cell death, the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assay was carried out using SH-SY5Y cell line. SH-SY5Y is a human derived neuroblastoma cell line and presents many of the biochemical and functional features of human neurons27. Therefore, it has been widely used as a human neuronal cell model in the cytotoxicity studies of AD20,28. As shown in Figure 1e, treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with aged Aβ42 for 48 h significantly increased LDH leakage suggesting Aβ42 aggregates induced massive cell death. However, co-incubation Aβ42 monomers and brazilin substantially decreased the Aβ42-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner, as evidenced by the decrease of LDH release (Figure 1e). At a molar ratio of brazilin to Aβ42 at 0.2 or 0.4, the cell death was about 40% decreased. Visual inspection of cellular morphology by phase-contrast microscopy and observation of the nuclear changes by Hoechst 33342 staining were carried out to monitor cell apoptosis induced by various Aβ42 species treated and untreated by brazilin (Figure S8a). The normal SH-SY5Y cells exhibited elongated neurites and seldom stained by Hoechst 33342 (Figure S8a). After incubation with 25 μM Aβ42 fibrils for 48 h, the cells displayed obvious morphological changes, such as cell body shrinkage, aggregation and condensation of nuclear chromatin, revealing the neuronal apoptosis induced by Aβ42 aggregates (Figure S8a). Co-incubation of Aβ42 monomers with brazilin significantly alleviated the morphological deterioration of cells and nuclear condensation in contrast to that of Aβ42-treated group. The counts of apoptotic bodies stained by Hoechst 33342 also suggested that brazilin significantly reduced the apoptosis induced by Aβ42 (Figure S8b). The above results indicate that brazilin can protect SH-SY5Y cells against the Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity. The cytotoxicity of brazilin towards SH-SY5Y cells was also evaluated using MTT assay (Figure S9). It is clear that almost no cytotoxicity was observed at lower brazilin concentrations (≤10 μM). When the SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 30 μM brazilin, however, ~35% cytotoxicity was observed.

Molecular insight into the effect of brazilin on Aβ42 fibrillogenesis

The above experimental results have confirmed that brazilin can inhibit the fibrillogenesis of Aβ42 and greatly reduce its cytotoxicity. To explore the molecular details of the interactions between brazilin and Aβ42, all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed. Due to the very low stability and the transient and highly dynamic nature of Aβ oligomers, it is difficult to obtain their atomic-level models using X-ray crystallography and NMR experiments. Instead, several Aβ fibril structures have been proposed based on the solid-state NMR data, including the fibrillar Aβ17–42 pentamer24 and the Aβ1–40 fibrils29,30. Moreover, several studies proved that the secondary structures of Aβ oligomers were mainly β-sheet31,32. So, the NMR-based fibrillar Aβ17–42 pentamer has been often used as an Aβ oligomer in literature33,34,35,36. Hence, we also used the fibrillar Aβ17–42 pentamer as a starting state to probe the interactions between brazilin and Aβ. The atomic contacts between brazilin and fibrillar Aβ17–42 pentamer were calculated to represent the interactions between brazilin and Aβ. The averaged probabilities of atomic contacts between brazilin and each residue of fibrillar Aβ17–42 pentamer are shown in Figure S10. The simulation results suggest that brazilin interacted preferentially with some of the residues, most notably residues Leu17, Phe19, Phe20 and Lys28 over others, although brazilin molecules made contacts with almost all residues of Aβ17–42.

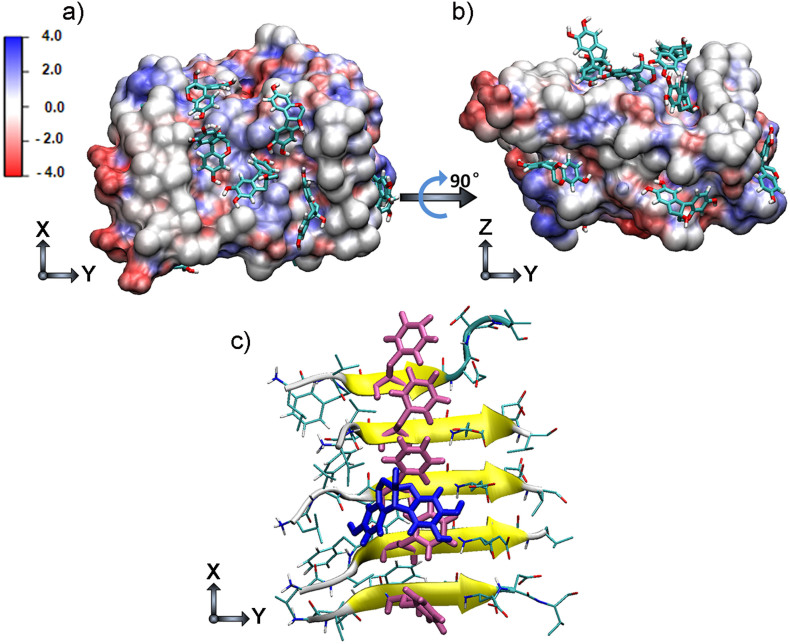

Figures 2a and 2b show the snapshots of brazilin molecules binding to the fibrillar Aβ17–42 pentamer. It can be seen that brazilin had more than one binding site on Aβ17–42 pentamer, consistent with the previous contact analysis. A detailed analysis revealed that the phenyl ring of brazilin bound directly with the phenyl ring of Phe20 (Figure 2c). This suggests that there were strong hydrophobic interactions between brazilin and Aβ42. In addition, there are four hydroxyl groups within one brazilin molecule (see Figure 1a). Thus, brazilin could also interact with Aβ through hydrogen bonding. The number of hydrogen bonds between brazilin and Aβ17–42 pentamer was calculated (Figure S11). It reveals that there were more than 10 hydrogen bonds between Aβ17–42 pentamer and brazilin molecules. Therefore, brazilin molecules interact with Aβ principally through hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding. The results suggest that these direct interactions lead to the formation of unstructured aggregates, and ultimately give brazilin the inhibitory effects on Aβ fibrillogenesis and cytotoxicity.

Figure 2. Representative brazilin-Aβ17–42 pentamer binding complexes derived from molecular dynamics simulations.

The top (a) and side (b) views of the complex structure of Aβ17–42 pentamer and brazilin molecules obtained from molecular dynamics simulation trajectories. The surface of Aβ17–42 pentamer is colored according to the charges of the atoms. Negatively and positively charged zones are depicted in red and blue, respectively. (c) Interactions between the phenyl ring in brazilin and the phenyl ring in Phe20 of Aβ17–42 pentamer. The main chain of Aβ17–42 is shown by a yellow NewCartoon model and its side chains are represented by a line. Phe20 is colored pink, and the brazilin is colored blue. The snapshot is plotted by visual molecular dynamics (VMD) software (http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/).

Brazilin remodels Aβ fibrils

The removal or remodeling of amyloid fibrils is another central therapeutic strategy in AD. Especially, recent studies found that the toxic oligomers were predominantly formed through a fibril-catalyzed secondary nucleation mechanism6. Therefore, the ability of eliminating mature fibrils is an essential feature of a potential drug for AD. Hence, the effect of brazilin on mature Aβ42 fibrils was investigated. The amyloid fibrils were produced by incubating Aβ42 monomers at 37°C for 24 h, a proper condition that allows Aβ to grow into mature fibrils. It was also confirmed that Aβ fibrils with β-sheet-rich structure were generated after 24 h incubation (Figure S12).

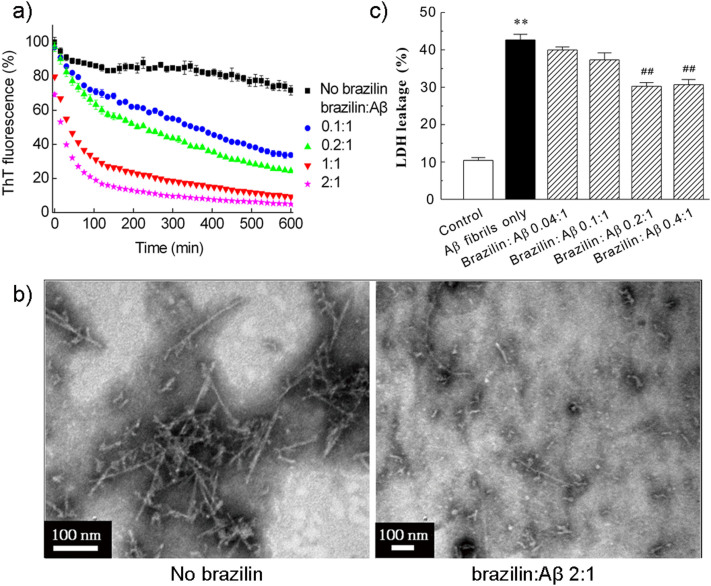

The effect of brazilin on the mature Aβ42 fibrils was first monitored by ThT fluorescence measurement (Figure 3a). By adding brazilin into Aβ42 fibrils, a remarkable dose-dependent reduction of ThT fluorescence was observed as compared with the control sample. When Aβ42 fibrils were treated with an equimolar concentration of brazilin, the ThT fluorescence intensity decreased by above 90% in 10 h. This indicates that the preformed fibrils were converted into some other species that did not bind ThT molecules to generate an observable ThT fluorescence. The ThT assays confirmed that brazilin is capable of not only inhibiting the formation of new fibrils, but also remodeling the preformed fibrils.

Figure 3. Remodeling effect of brazilin on Aβ42 fibrils.

Aβ42 fibrils were incubated with different concentrations of brazilin. (a) Loss of ThT fluorescence of Aβ42 fibrils measured in the absence and presence of different concentrations of brazilin in in situ real-time assays. See method section for more details. The ThT fluorescence of Aβ42 fibrils was defined as 100%. (b) Brazilin-induced remodeling of Aβ42 mature fibrils into granular aggregates was monitored by TEM after 24 h incubation. (c) Brazilin alleviated the cytotoxicity of Aβ42 fibrils. Mature Aβ42 fibrils were co-incubated at 37°C for 24 h in the absence and presence of brazilin, and then added into SH-SY5Y cells at a final Aβ42 concentration of 25 μM. After 48 h treatment, cytotoxicity was evaluated using LDH leakage assay. ** p < 0.01, compared to control groups. ## p < 0.01, compared to Aβ42-treated group.

We then directly observed the morphologies of brazilin-induced Aβ42 species from fibrils with TEM (Figures 3b and S13). It is clear that the fibrils were reduced markedly and converted into some granular aggregates after incubation with brazilin for 24 h, whereas untreated Aβ42 fibrils kept the well-developed fibrillar morphology. This indicates that brazilin alters significantly the morphology of Aβ42 fibrils due to its remodeling effects, correlating well with the ThT fluorescence data. The remodeling product was centrifuged and the supernatant was analyzed by SEC (Figure S14a). Similar to the inhibition experiments, the first peak area increased with increasing brazilin concentration (Figure S14b), whereas the peak area of the monomer did not exhibit distinct differences. It is noted that the majority of unstructured aggregates remodeled by brazilin were removed by centrifugation. Therefore, the monomeric peak was the major peak in the remodeling experiments. This implies that brazilin could convert Aβ42 fibrils into unstructured aggregates of molecular weights >70 kDa, rather than monomers, similar to the case of curcumin37.

Next, CD spectroscopy was used to probe the secondary structure of these remodeled Aβ42 species (Figure S15). It shows that brazilin did not obviously affect the β-sheet structure of the protein although it could remodel the fibrillar morphology. That is, brazilin-treated Aβ42 species still had some β-sheet structure, consistent with the previous results. We also tested whether these brazilin-treated fibril products were recognized by antibody A11 using dot blot assays (Figure S16). The amount of A11-immunoreactive oligomers decreased with increasing brazilin concentration. However, both brazilin-treated and untreated Aβ42 were detected by antibody 6E10. This demonstrates that brazilin-remodeled fibril species were similar with those aggregates formed in the co-incubation of Aβ42 monomers with brazilin, which were structurally distinct from the well-described toxic oligomers.

Cytotoxicity of the brazilin-remodeled Aβ fibril species was also examined using LDH leakage assays. Brazilin-treated and untreated Aβ42 fibrils were introduced to SH-SY5Y cells, and the LDH release was measured after 48 h incubation (Figure 3c). The untreated Aβ42 fibrils gave rise to a significant increase of LDH release, indicating massive cell death induced by Aβ42 fibrils. However, the co-incubation of Aβ42 fibrils and brazilin significantly alleviated Aβ42 fibril-induced cell death (Figure 3c). At a molar ratio of brazilin to Aβ42 at 0.2 or 0.4, the cell death was about 30% decreased. The observation of cellular morphology and nuclear condensation also further validated that the remodeling effect of brazilin reduced the cytotoxicity of Aβ42 fibrils (Figure S8). The decrease of cell death and apoptosis due to remodeling effects of brazilin was less than the inhibitory effects (Figures 1e and S8), but statistically significant. The main reason for the less inhibitory effects might be that some of the aggregates resulting from the remodeling reaction still maintained some degree of amyloid structures and cytotoxicity.

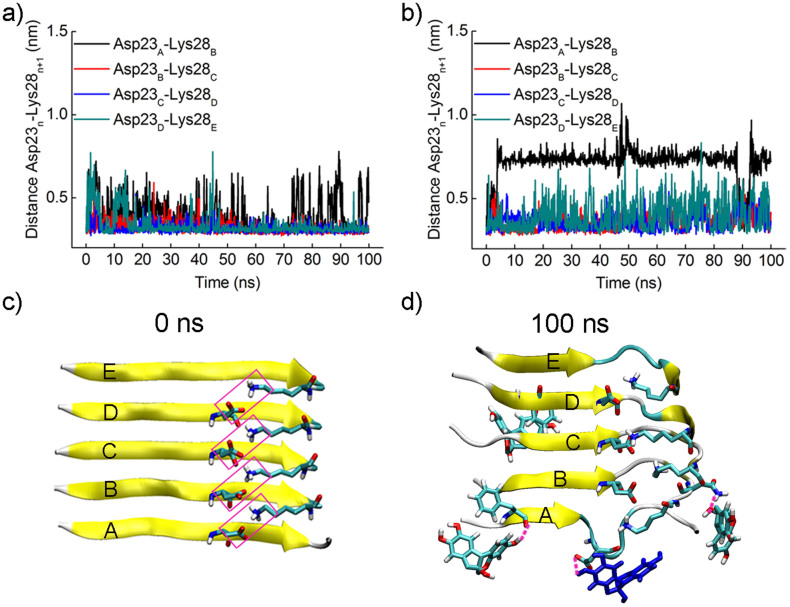

MD simulations were also performed to probe the molecular mechanism of the mature fibril remodeling by brazilin. Previous studies have proposed that the intermolecular salt bridge Asp23-Lys28 plays an important role in the stability of mature fibrils24. Thus, the distance between Asp23 of chain A and Lys28 of chain B was studied in the absence and presence of brazilin (Figure 4). Figure 4a shows that the distance between Asp23 and Lys28 kept stable around 0.3 nm in the absence of brazilin, except for some transient increases. That is, the salt bridge Asp23-Lys28 kept stable in water. In the presence of brazilin, however, the distance between Asp23 of chain A and Lys28 of chain B became greater than 0.7 nm after approximately 5 ns (Figure 4b). From the snapshot in Figure 4d, it is clear that three brazilin molecules interacted with chains A and B via three hydrogen bonds. Of them, one brazilin molecule interacted with Asp23 of chain A by hydrogen bonding, disrupting the native salt bridge Asp23-Lys28 (Figure 4c). Thus, the backbone hydrogen bonds were interfered and finally the marginal chain was gradually disarranged and tended to participate in the formation of other unstructured aggregates. As a result, the number of backbone hydrogen bonds between chains A and B decreased rapidly from the initial value of 22 to 12 in the first 10 ns (Figure S17). The above simulation data indicate that brazilin interacted preferentially with the intermolecular salt bridge Asp23-Lys28 via hydrogen bonding, which partly perturbed the backbone hydrogen bonds of Aβ fibrils, thus leading to the fibril remodeling.

Figure 4. Brazilin disrupts the salt bridge Asp23-Lys28.

The distances between the mass center of the carboxyl group of Asp23 and the amino group of Lys28 in two adjacent chains were monitored as a function of simulation time (a) in the absence and (b) presence of brazilin. (c) The salt bridges between each chain and its adjacent chain within the initial Aβ17–42 pentamer. The salt bridges are framed in pink. (d) The snapshot of the salt bridge between chains A and B disrupted by brazilin molecules at 100 ns. The three hydrogen bonds observed between brazilin and Aβ17–42 pentamer are represented using pink dash lines. The brazilin molecules interacting with Asp23 via hydrogen bonding are colored in blue. The main chain of Aβ17–42 is shown by a yellow NewCartoon model. Atoms of brazilin and the side chains of some residues are colored red for oxygen, white for hydrogen, and green for carbon. The snapshots are plotted by visual molecular dynamics (VMD) software (http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/).

A mechanistic model

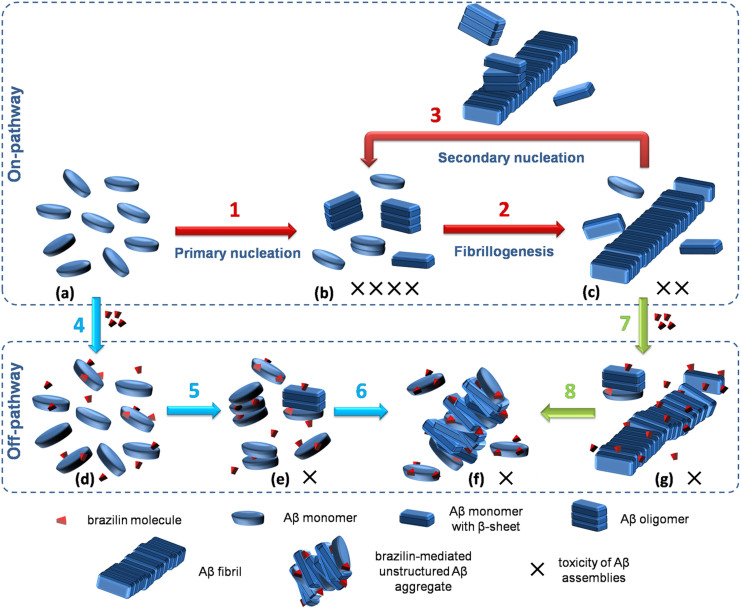

Based on the experimental and computational results, we have proposed a model to interpret the working mechanism of brazilin effects on Aβ aggregation (Figure 5). Aβ aggregation is a highly complex process that involves sequential formations of various Aβ aggregation species, including oligomers, protofibrils and fibrils. Recently, the primary and secondary nucleation mechanisms were proposed to characterize the Aβ aggregation pathway. According to the comprehensive study38, it is considered that in the primary nucleation pathway, Aβ monomers with initial α-helix or coil structure self-assemble into β-sheet-rich oligomers (step 1 in Figure 5), which are the most toxic form (b state in Figure 5). Then, the oligomers and monomers can aggregate further into protofibrils and low-toxic fibrils (step 2 in Figure 5). When a critical concentration of fibrils has been reached, the secondary nucleation pathway is triggered and plays a dominant role in the generation of toxic oligomers (step 3 in Figure 5).

Figure 5. Schematic representation for the working mechanism of brazilin on its inhibition of Aβ42 fibrillogenesis and fibril remodeling.

Steps 1 to 3 represent the on-pathway Aβ aggregation (red arrows), including the primary nucleation pathway (step 1), fibrillogenesis pathway (step 2) and the fibril-catalyzed secondary nucleation pathway (step 3); steps 4 to 6 show that brazilin redirects the on-pathway Aβ aggregation into off-pathway unstructured aggregates, inhibiting the primary nucleation (blue arrows); steps 7 and 8 indicate that brazilin remodels Aβ fibrils into off-pathway aggregates, blocking the secondary nucleation (green arrows). a to g represent the different states of Aβ aggregation with or without brazilin. More details are discussed in the text. The number of “X” indicates the toxic level of Aβ aggregation species.

In the presence of brazilin, however, it can bind to Aβ monomers and oligomers via hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding, which prevents the formation of on-pathway intermediates of Aβ and goes off-pathway aggregation instead (steps 4 to 6 in Figure 5). Although the brazilin-induced Aβ species (f state in Figure 5) still contain some β-sheet structure, the structures of the aggregates are different from those on-pathway Aβ oligomers, exhibiting lower cytotoxicity. Furthermore, brazilin can remodel the mature fibrils into unstructured and less toxic species (f state in Figure 5) by disrupting the salt bridge Asp23-Lys28 via hydrogen bonding (steps 7 and 8 in Figure 5). Most importantly, remodeling of the mature fibrils can make them lose the catalytic activity of secondary nucleation (i.e., blocking step 3 in the on-pathway aggregation)6. This is of great significance in the treatment of AD because toxic oligomers are mainly formed through the secondary nucleation in a fibril-dependent manner6,7. Thus, due to its dual functions, brazilin is able to redirect the pathway of Aβ aggregation into less toxic species and to block the secondary nucleation mainly responsible for the formation of toxic oligomers.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that Aβ monomers self-assemble into high toxic oligomers and low toxic amyloid fibrils by a primary nucleation mechanism38. Thus, most of previous therapeutic strategies for AD were only aimed at blocking the formation of neurotoxic oligomers28. Despite extensive studies, the inhibiting efficiencies of those agents reported in the literature were still not high enough to meet the requirements for AD treatment. Moreover, mature fibril remodeling was seldom studied and the mechanism is poorly understood. Recent studies emphasized that the toxic oligomeric species are produced from the monomeric peptides through a fibril-catalyzed secondary nucleation reaction once the critical concentration of fibrils is exceeded6,7. In addition, some studies have revealed that when the symptoms of AD patients are found there have been some amyloid plaques in their brains8. So, most of toxic oligomers should be produced by the surface catalysis via amyloid fibrils before a definite diagnosis of AD. That is, a major approach for completely curing AD should focus on destroying the secondary nucleation pathway. Therefore, considering both the preventive and curative aspects, intensive efforts to develop therapeutic agents capable of targeting both Aβ fibrillogenesis and the preformed fibrils are essential.

Brazilin is mainly extracted from Caesalpinia sappan, with various biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory39 and anti-platelet aggregation activities40. In this study, we identified brazilin as an effective inhibitor of Aβ fibrillogenesis by extensive biophysical, biochemical, cell biological and computational methods. The results confirmed that brazilin could efficiently inhibit amyloid fibrillogenesis and protect cultured cells from Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity (Figure 1). As compared with EGCG, the drug under Phase III clinical trials for AD, the value of IC50 of brazilin was smaller than those of EGCG (Figure 1b). Moreover, the IC50 of brazilin was about one order of magnitude smaller than those of curcumin (IC50 ~ 13.3 μM)41 and reveratrol (IC50 ~ 15.1 μM)42 reported previously, at the same Aβ42 concentration (25 μM) (Table S4). The small IC50 value of brazilin represented its powerful inhibitory potency on Aβ fibrillogenesis even at a very low concentration. This is of importance for the central nervous system (CNS) drugs, because the concentrations of CNS drugs in the brain is usually very low after eluding various metabolism and crossing BBB22.

It is known that Aβ aggregation is driven mainly by hydrophobic forces including aromatic packing and electrostatic interactions including hydrogen bonding43. Our simulation data have demonstrated that brazilin directly bound with Aβ via hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding (Figures 2, S10 and S11). These interactions may interfere with the intermolecular interactions of Aβ and ultimately lead to the formation of unstructured aggregates with molecular weights of above 70 kDa (Figure S5). It is interesting to note that although brazilin could efficiently inhibit the formation of toxic Aβ aggregates and the brazilin-induced aggregates could not be recognized by antibody A11 (Figure S7), it did not completely inhibit the conformational transition of Aβ from its initial random coil to β-sheet structure (Figures 1d and S6). This is possible because brazilin just inhibited the intermolecular interactions of Aβ species and blocked the on-pathway aggregation, but could not markedly inhibit the conformational transition of the protein. The similar phenomenon was also found for some small molecular inhibitors44,45,46. However, it is distinctly different from some other potent inhibitors, such as EGCG17 and resveratrol47, which have been demonstrated to inhibit the conformational transition of Aβ. This finding implies that suppressing the conformational transition of Aβ is not indispensable to inhibit Aβ fibrillogenesis and to remove the cytotoxicity of the Aβ species.

When brazilin was incubated with preformed Aβ42 fibrils, brazilin could interact preferentially with the intermolecular salt bridge Asp23-Lys28 via hydrogen bonding (Figure 4). This interaction could partly perturb the backbone hydrogen bonds of Aβ fibrils, and ultimately result in the remodeling of Aβ fibrils into unstructured and less toxic aggregates. Similar results were reported with EGCG48,49 and tanshinones20, which remodel large amyloid fibrils into smaller, off-pathway unstructured forms with relatively low cytotoxicity. It is noted that the brazilin-remodeled Aβ species had lost the structural and topological characteristics of amyloid fibrils, as shown in Figures 3a and 3b, which are necessary for catalyzing the secondary nucleation50. This means that the surface of these Aβ species remodeled by brazilin can no longer catalyze the secondary nucleation reaction, which is known to be the predominant way of oligomer formation6. Thus, remodeling of preformed fibrils by brazilin would be significant in the treatment of AD because the removal of Aβ fibrils can block the second nucleation pathway and significantly reduce the formation of toxic oligomers.

Moreover, the pharmacokinetics studies of brazilin in vivo have been performed in literature51,52,53. After a single oral dose or intravenous injection dose of 100 mg/kg brazilin in rats, the maximum brazilin concentrations in plasma were 3.4 or 82.2 μg/mL with a relatively long elimination half-life (4.5 or 6.2 h), respectively51,53. This indicates that brazilin is sufficiently stable in vivo. Furthermore, brazilin could be detected in the brain after intravenous injection administration of brazilin at 50.0 mg/kg to rats52. This means that brazilin may come through BBB and target to the Aβ location in a patient's brain. These characteristics enable brazilin to be an appropriate CNS drug. Based on these findings and discussions, it is convinced that brazilin offers a promising lead compound with dual protective roles (i.e., amyloid fibrillogenesis inhibition and mature fibril remodeling) in the treatment of AD. Chemical modifications and development of specific drug delivery systems would further enhance its inhibitory capacity and druggability.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Aβ42 (>95%) was purchased from GL Biochem (Shanghai, China) as lyophilized powder. 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP), ThT and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were attained from GIBCO (Grand Island, NY, USA). Antibodies A11 and 6E10 were obtained from Invitrogen (Frederick, MD, USA) and Covance (Dedham, MA, USA), respectively. All other chemicals were the highest purity available from local sources.

Aβ42 preparation

Aβ42 was prepared as described in literature54. In brief, lyophilized Aβ42 was stored at −80°C. The protein was first unfreezed at room temperature for 30 min before use, and then dissolved in HFIP to 1.0 mg/mL. The solution was in quiescence at least 2 h, and then sonicated for 30 min to destroy the pre-existing aggregates. Thereafter, the solution was lyophilized by vacuum freeze-drying overnight. Finally, the protein was stored at −20°C immediately.

Aβ42 aggregation and its fibril treatment with brazilin

Immediately prior to use, the HFIP-treated Aβ42 was redissolved in 20 mM NaOH, sonicated for 20 min, and then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove the existing aggregates. For inhibition experiments, about top 75% of the supernatant was collected and diluted with phosphate buffer solution (100 mM sodium phosphate, 10 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing various concentrations of brazilin, leading to the final protein concentration of 25 μM. The samples were then incubated at 37°C at constant shaking rate. For the treatment of Aβ42 fibrils, the monomeric Aβ42 was first incubated by the procedure described above for 24 h. Then different concentrations of brazilin stock solutions in PBS (pH 7.4) were added into the Aβ fibril solution and incubated at 37°C.

ThT fluorescence assay

The assay samples (200 μL) were mixed in a 96-well plate, containing 25 μM Aβ monomers (in aggregation experiments) or Aβ fibrils (in fibril remodeling experiments), 20 μM ThT and different concentrations of brazilin in PBS buffer (pH 7.4). The ThT fluorescence kinetics was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (SpectraMax M2e, Molecular Devices, USA) at 15 min reading intervals and 5 s shaking before each read. Aβ42 samples with different concentrations of brazilin were incubated firstly for 24 h. Then ThT was added and detected immediately. The excitation and emission wavelengths were 440 and 480 nm, respectively. The fluorescence intensity of solution without Aβ42 was subtracted as background from each read with Aβ42. The measurements were performed in triplicate and all reported values represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Aβ42 samples were deposited onto carbon-coated copper grids (300-mesh) and were air-dried. The samples were negatively stained using 2% (w/v in water) phosphotungstic acid. The stained samples were examined and photographed using a JEM-100CXII transmission electron microscope system (JEOL Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 100 kV.

CD spectroscopy

CD spectra of 25 μM Aβ42 monomer or fibril solutions in the absence and presence of brazilin were measured using a J-810 spectrometer (Jasco, Japan) at room temperature. A quartz cell with 1 mm path length was used for far-UV (195–260 nm) measurements with 1 nm bandwidth at a scan speed of 100 nm/min. The CD spectra of solutions without Aβ42 were subtracted as background from the CD signals with Aβ42 to isolate the Aβ-specific changes. All spectra were the average of three consecutive scans for each sample.

Cell viability assay

SH-SY5Y cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA) and maintained in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 U/mL streptomycin at 37°C under an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Cell death was quantitatively assessed by measuring the release of LDH as previously reported55. Briefly, 24 h after seeding, the culture medium was replaced with FBS-free medium, and then Aβ42 and brazilin-modified Aβ42 (brazilin was co-incubated with Aβ42 monomers or fibrils at 37°C for 24 h) were added into SH-SY5Y cells. After treatment for 48 h, the LDH leakage assay was performed. Prior to assay, the cells were incubated with 1% (V/V) Triton X-100 in FBS-free medium at 37°C for 1 h to obtain a representative maximal LDH release as the positive control with 100% cytotoxicity. Extracellular LDH leakage was evaluated by using the assay kit (Roche Diagnostics, IN, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells in 96-well plates were centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min, 50 μL culture supernatants were collected from each well, 50 μL reaction buffer supplied in the kit was then added. The leakage of LDH was assessed at a test wavelength of 490 nm with 655 nm as a reference wavelength 30 min after mixing at room temperature. The LDH release data, representative of at least three independent experiments carried out with different cell culture preparations, were presented as mean ± S.E.M. Analysis of variance was carried out for statistical comparisons using t-test, and p < 0.05 or less was considered to be statistically significant.

Molecular simulation system

Fibrillar Aβ17–42 pentamer was used as the target to probe the binding sites of brazilin and to underlie its inhibitory and fibril remodeling mechanisms. The coordinates of fibrillar Aβ17–42 pentamer were obtained from Protein Data Bank (PDB code: 2BEG). The initial structure of brazilin was taken from the PubChem Compound Database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pccompound). The atomic charge and charge groups of brazilin were generated based on the GROMOS96 force field parameters56.

Aβ17–42 pentamer was first put in the center of a cubic box of dimensions 80 Å × 80 Å × 80 Å, and periodic boundary conditions was applied. Then, 10 brazilin molecules were randomly located and oriented around the Aβ17–42 pentamer. After that, explicit water molecules non-overlapping with brazilin and Aβ17–42 pentamer were added in the system. Finally, five positive ions (Na+) were added by replacing water molecules to neutralize the whole system. After the simulation system was minimized for 1000 steps, it was equilibrated for 100 ps under an isothermal–isobaric ensemble and isochoric-isothermal ensemble, respectively. Then, three MD simulations of 100 ns were carried out under different initial conditions by assigning different initial velocities on each atom of the simulation systems.

Molecular dynamics simulation

All of MD simulations were performed using the GROMACS 4.0.5 software package together with the GROMOS96 force field56. Water was described using the simple point charge (SPC) water model. The pair list of non-bond interaction was updated every 4 steps with a cut-off of 9 Å, and electrostatic interactions were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method with a grid-spacing of 0.12 nm57. Temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 atm) were controlled by the V-rescale thermostat and Berendsen barostat, respectively58,59. The Newton's motion equations were integrated by leapfrog algorithm with a 2 fs time step. LINCS algorithm was employed to constrain all bond lengths60. Initial velocities were assigned according to a Maxwell distribution. The atomic coordinates were saved every 0.5 ps. MD simulations were run on a 160-CPU Dawning TC2600 blade server (Dawning, Tianjin, China).

Simulation data analyses

The auxiliary programs provided with GROMACS 4.0.5 package were used to analyze the simulation trajectories. The program g_minidist was used to calculate the contact number between brazilin and Aβ17–42 pentamer and the distance between residues Asp23 and Lys28 of the adjacent chain. The g_hbond was used to compute the number of hydrogen bonds between brazilin and Aβ17–42 pentamer, as well as the intermolecular hydrogen bonds of Aβ17–42 pentamer. The snapshots of simulation trajectories were visualized using visual molecular dynamics (VMD) software (http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/)61.

Author Contributions

W.J.D., J.J.G. and M.T.G. contributed equally to this work. X.Y.D., F.F.L. and Y.S. designed and supervised the study. W.J.D., J.J.G. and M.T.G. performed the biophysical and biochemical experiments. S.Q.H. and Y.F.H. performed the cell biological experiment. W.J.D. did the computational studies. F.F.L., S.J. and Y.S. wrote the paper with contributions from M.T.G. and X.Y.D. All authors reviewed, revised and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

SI

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21376172, 21236005 and 21376173), the High-Tech Research and Development Program of China from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. 2012AA020206), and the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin from Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Commission (Contract No. 13JCZDJC27700). We thank Dr. Wei Cui for helpful discussions about cytotoxicity assay.

References

- Jakob-Roetne R. & Jacobsen H. Alzheimer's disease: from pathology to therapeutic approaches. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 48, 3030–3059 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker-Mill C., Mayes J., Allsop D. & Kolosov O. V. Ultrasonic force microscopy for nanomechanical characterization of early and late-stage amyloid-beta peptide aggregation. Sci. Rep. 4, 4004 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S. et al. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature 440, 352–357 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G. M. et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 14, 837–842 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. J. et al. Neurotoxic amyloid beta oligomeric assemblies recreated in microfluidic platform with interstitial level of slow flow. Sci. Rep. 3, 1921 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. I. et al. Proliferation of amyloid-beta42 aggregates occurs through a secondary nucleation mechanism. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 9758–9763 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisl G. et al. Differences in nucleation behavior underlie the contrasting aggregation kinetics of the A beta 40 and A beta 42 peptides. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9384–9389 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin R. J., Fagan A. M. & Holtzman D. M. Multimodal techniques for diagnosis and prognosis of Alzheimer's disease. Nature 461, 916–922 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P., Sorribas A. & Howes M. J. R. Natural products as a source of Alzheimer's drug leads. Nat. Prod. Rep. 28, 48–77 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L. et al. Structure-based discovery of fiber-binding compounds that reduce the cytotoxicity of amyloid beta. Elife 2, e00857 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciarretta K. L., Gordon D. J. & Meredith S. C. Peptide-based inhibitors of amyloid assembly. Method. Enzymol. 413, 273–312 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopping G. et al. Designed alpha-sheet peptides inhibit amyloid formation by targeting toxic oligomers. Elife 3, e01681 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgado I. et al. Molecular basis of beta-amyloid oligomer recognition with a conformational antibody fragment. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12503–12508 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles L. A., Crespi G. A. N., Doughty L. & Parker M. W. Bapineuzumab captures the N-terminus of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta peptide in a helical conformation. Sci. Rep. 3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. et al. Nanomaterials for Reducing Amyloid Cytotoxicity. Adv. Mater. 25, 3780–3801 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. & Bitan G. Modulating self-assembly of amyloidogenic proteins as a therapeutic approach for neurodegenerative diseases: strategies and mechanisms. ChemMedChem 7, 359–374 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrnhoefer D. E. et al. EGCG redirects amyloidogenic polypeptides into unstructured, off-pathway oligomers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 558–566 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M. et al. Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-beta(1–42) oligomers to fibrils. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 561–567 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yang Y. & Zhang Y. Isobavachalcone and bavachinin from Psoraleae Fructus modulate Abeta42 aggregation process through different mechanisms in vitro. FEBS Lett. 587, 2930–2935 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. et al. Tanshinones Inhibit Amyloid Aggregation by Amyloid-beta Peptide, Disaggregate Amyloid Fibrils, and Protect Cultured Cells. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 4, 1004–1015 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi A. & Fioni A. Virtual screening using PLS discriminant analysis and ROC curve approach: An application study on PDE4 inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 48, 1686–1692 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajouhesh H. & Lenz G. R. Medicinal chemical properties of successful central nervous system drugs. NeuroRx 2, 541–553 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan A., Hartley D. M. & Lashuel H. A. Preparation and characterization of toxic A beta aggregates for structural and functional studies in Alzheimer's disease research. Nat. Protoc. 5, 1186–1209 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhrs T. et al. 3D structure of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta(1–42) fibrils. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17342–17347 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellarin R. & Caflisch A. Interpreting the aggregation kinetics of amyloid peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 360, 882–892 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R. et al. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 300, 486–489 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agholme L. et al. An In Vitro Model for Neuroscience: Differentiation of SH-SY5Y Cells into Cells with Morphological and Biochemical Characteristics of Mature Neurons. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 20, 1069–1082 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieschke J. et al. Small-molecule conversion of toxic oligomers to nontoxic beta-sheet-rich amyloid fibrils. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 93–101 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkova A. T., Yau W. M. & Tycko R. Experimental constraints on quaternary structure in Alzheimer's beta-amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry 45, 498–512 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. X. et al. Molecular structure of beta-amyloid fibrils in Alzheimer's disease brain tissue. Cell 154, 1257–1268 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. P. et al. Structural Characterization of a Soluble Amyloid beta-Peptide Oligomer. Biochemistry 48, 1870–1877 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham J. D., Spencer R. K., Chen K. H. & Nowick J. S. A Fibril-Like Assembly of Oligomers of a Peptide Derived from beta-Amyloid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12682–12690 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassler K., Horn A. H. C. & Sticht H. Effect of pathogenic mutations on the structure and dynamics of Alzheimer's A beta(42)-amyloid oligomers. J. Mol. Model. 16, 1011–1020 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochdorffer K. et al. Rational design of beta-sheet ligands against Abeta42-induced toxicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 4348–4358 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X. et al. Molecular interactions of Alzheimer amyloid-beta oligomers with neutral and negatively charged lipid bilayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 8878–8889 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blinov N., Dorosh L., Wishart D. & Kovalenko A. Association Thermodynamics and Conformational Stability of beta-Sheet Amyloid beta(17–42) Oligomers: Effects of E22Q (Dutch) Mutation and Charge Neutralization. Biophys. J. 98, 282–296 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K., Hasegawa K., Naiki H. & Yamada M. Curcumin has potent anti-amyloidogenic effects for Alzheimer's beta-amyloid fibrils in vitro. J. Neurosci. Res. 75, 742–750 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer S., Ricchiuto P. & Kashchiev D. Two-Step Nucleation of Amyloid Fibrils: Omnipresent or Not? J. Mol. Biol. 422, 723–730 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae I. K. et al. Suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase by brazilin in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 513, 237–242 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang G. S. et al. Effects of Brazilin on the phospholipase A2 activity and changes of intracellular free calcium concentration in rat platelets. Arch. Pharm. Res. 21, 774–778 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shytle R. D. et al. Optimized turmeric extracts have potent anti-amyloidogenic effects. Curr. Alzheimer. Res. 6, 564–571 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C. J. et al. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Multitarget-Directed Resveratrol Derivatives for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. J. Med. Chem. 56, 5843–5859 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall K. E. et al. Hydrophobic, aromatic, and electrostatic interactions play a central role in amyloid fibril formation and stability. Biochemistry 50, 2061–2071 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio F. et al. Carnosine Inhibits A beta 42 Aggregation by Perturbing the H-Bond Network in and around the Central Hydrophobic Cluster. Chembiochem 14, 583–592 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaurin J. et al. Inositol stereoisomers stabilize an oligomeric aggregate of Alzheimer amyloid beta peptide and inhibit A beta-induced toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18495–18502 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D. S. et al. Manipulating the amyloid-beta aggregation pathway with chemical chaperones. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32970–32974 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladiwala A. R. A. et al. Resveratrol Selectively Remodels Soluble Oligomers and Fibrils of Amyloid A beta into Off-pathway Conformers. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24228–24237 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieschke J. et al. EGCG remodels mature alpha-synuclein and amyloid-beta fibrils and reduces cellular toxicity. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7710–7715 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palhano F. L., Lee J., Grimster N. P. & Kelly J. W. Toward the molecular mechanism(s) by which EGCG treatment remodels mature amyloid fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 7503–7510 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J. S. et al. Novel mechanistic insight into the molecular basis of amyloid polymorphism and secondary nucleation during amyloid formation. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 1765–1781 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z. et al. A validated LC-MS/MS method for rapid determination of brazilin in rat plasma and its application to a pharmacokinetic study. Biomed. Chromatogr. 27, 802–806 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y. Y. et al. Application of a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method to the pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and excretion studies of brazilin in rats. J. Chromatogr. B 931, 61–67 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y. Y. et al. A simple high-performance liquid chromatographic method for the determination of brazilin and its application to a pharmacokinetic study in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 151, 108–113 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. et al. Structural, morphological, and kinetic studies of beta-amyloid peptide aggregation on self-assembled monolayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 15200–15210 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S. Q. et al. Bis(propyl)-cognitin protects against glutamate-induced neuro-excitotoxicity via concurrent regulation of NO, MAPK/ERK and PI3-K/Akt/GSK3 beta pathways. Neurochem. Int. 62, 468–477 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gunsteren W. F., Billeter S. R., Eising A. A., Hünenberger P. H., Krüger P., Mark A. E., Scott W. R. P. & Tironi I. G. Biomolecular Simulation: The GROMOS96 Manual and User Guide [vdf Hochschulverlag AG (ed.)] [1–1044] (Zürich, Switzerland, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Darden T., York D. & Pedersen L. Particle Mesh Ewald - an N.Log(N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Bussi G., Donadio D. & Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H. J. C. et al. Molecular-Dynamics with Coupling to an External Bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H. J. C. & Fraaije J. G. E. M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463–1472 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W., Dalke A. & Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 14, 33–38 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SI