Abstract

Combining positron emission tomography (PET) and MRI necessarily involves an engineering tradeoff as the equipment needed for the two modalities vies for the space closest to the region where the signals originate. In one recently described scanner configuration for simultaneous positron emission tomography–MRI, the positron emission tomography detection scintillating crystals reside in an 80-mm gap between the 2 halves of a 1-T split-magnet cryostat. A novel set of gradient and shim coils has been specially designed for this split MRI scanner to include an 110-mm gap from which wires are excluded so as not to interfere with positron detection. An inverse boundary element method was necessarily employed to design the three orthogonal, shielded gradient coils and shielded Z0 shim coil. The coils have been constructed and tested in the hybrid positron emission tomography-MRI system and successfully used in simultaneous positron emission tomography-MRI experiments.

INTRODUCTION

The combination of positron emission tomography (PET) and MRI is highly desirable since the two techniques produce complementary data; PET allows the distribution of minute concentrations of positron-emitting radionuclide tracers to be mapped, while MRI can provide anatomical data with myriad soft tissue contrasts. MRI and PET data can be coregistered to provide valuable diagnostic information. A hybrid PET-MRI system would make the coregistration process more simple, and simultaneous acquisition of the PET and MRI data decreases the duration of scanning.

Both PET and MRI require detectors to be placed optimally around the region of interest to maximize performance. MRI needs uniform excitation over the whole sample, and hence larger transmitter coils, but close coupling of the receiver to maximize signal to noise. The PET detector measures γ rays emanating from the sample and requires minimum attenuating or scattering material in the line of sight. The detector ring aperture is a compromise between close coupling to maximize sensitivity and a larger field of view to maintain spatial resolution at larger radial distances. There is therefore an inherent competition for space around the central region of the scanner, and compromises must be made in the performance of both systems. The principal challenge of combining PET with MRI is the reduction of the effects of these compromises on data quality while also minimizing the interaction between the two modalities. In the approach adopted by the group at Cambridge University, the lutetium oxyorthosilicate crystal γ-ray detectors (from a Siemens microPET Focus 120 system; Siemens Molecular Imaging Preclinical Solutions, Knoxville, TN) of the PET system are positioned in the 80-mm-wide gap of a specially designed, split, 1-T superconducting magnet (Magnex Scientific Ltd. Yarnton, Oxon., UK) (1). Fiber optic bundles 110-mm-long transfer the light generated by the lutetium oxyorthosilicate crystals to photomultiplier tubes (Hamamatsu H7546MOD; Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Hamamatsu City, Japan) for amplification of the optical signal and subsequent coincidence analysis. This experimental setup and the testing of its performance have been discussed in prior publications (1–3).

It should be noted that alternative approaches to combining PET and MRI data have also been described in the literature. Nonsimultaneous PET data may be acquired outside the MRI scanner in regions where the intense magnetic field necessary for MRI does not affect the photomultiplier tubes. Of the simultaneous PET-MRI acquisition methods, the most developed is the PET “insert” approach, in which a conventional MRI scanner is fitted with a PET system employing avalanche photodiodes that are used to detect the light emitted from lutetium oxyorthosilicate crystals (4, 5). PET with field-cycled MRI (6) is also currently being developed, in which PET acquisition is performed while the MR polarizing field is temporarily switched off to avoid interference with the photomultiplier tubes.

In the split-magnet hybrid PET-MRI scanner configuration, the gradient and shim coils must not occupy the central gap because they would cause significant scattering and attenuation of the γrays produced by positron annihilation in the sample. This precludes the use of conventional cylindrical gradient and shim coils. To solve this problem, a gradient coil design method that can be used to design coils wound on arbitrarily shaped surfaces (7) was used to generate a set of three orthogonal, shielded, split gradient coils. A shielded Z0 shim coil was also designed to provide a means of compensating any B0 components of eddy-current–induced magnetic fields. The X- and Y-gradient coil designs additionally incorporated an annular linking surface between the cylindrical primary and shield surfaces, without which they would have very poor performance. The inverse boundary element method that was employed (8, 9) involves discretizing the gradient coil surface into a series of boundary elements and then solving the inverse problem of finding a surface current density that will produce the desired magnetic field. Conventional second-order shim coils (as well as a Z3 shim coil) were also included by arranging multi-turn loops and arcs of wire at locations to cancel unwanted spherical harmonics (10). This approach was adequate since the windings of these coils did not impinge on the gap.

This paper describes the engineering constraints and the resulting surface geometry used in the inverse boundary element method design process. The construction and testing of the coil are also described. Results of the tests performed on the split gradient and shim coil set are presented with simultaneously acquired PET/MRI data. Finally, the most important aspects of the coil designs and the results obtained using the coil system are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inverse Boundary Element Method

In the inverse boundary element method (7, 8, 11, 12) the magnetostatic coil design problem is specified by defining the desired axial magnetic field distribution, Bz (r), at a point r in a region of uniformity (ROU) and a region of shielding (ROS) in terms of a series of magnetic field values at K points, Bz (rk) (k = 1,2,…,K). The magnetic shielding condition is imposed by requiring that the field falls to zero at the points in the ROS. The current-carrying surface of the coil is discretized into a series of flat, triangular boundary elements, although it is possible to use rectangular or axisymmetric conic sections as boundary elements (13, 14). In the work described here, 3D Studio MAX (Autodesk, San Rafael, CA) was used to generate the meshed current-carrying surfaces and to define the target field points. A discretized version of the stream function, ψ(r), was used to represent the current density J(r) via the expression, J(r) = ∇ × [ψ(r) (r)], where the surface is defined by its normal vector,

(r)], where the surface is defined by its normal vector,  (r). The axial magnetic field, Bz (rk), torque, M, inductance, L, and resistance, R, are parameterized in terms of the values of the stream function, ψn, at the nodes of the boundary element mesh. The form of ψ(r) within each mesh-triangle is linearly dependent on the values of ψn at the corners of the triangle. These parameterized coil properties can be traded off against each other by weighting their relative importance in a functional, Φ, to be minimized:

(r). The axial magnetic field, Bz (rk), torque, M, inductance, L, and resistance, R, are parameterized in terms of the values of the stream function, ψn, at the nodes of the boundary element mesh. The form of ψ(r) within each mesh-triangle is linearly dependent on the values of ψn at the corners of the triangle. These parameterized coil properties can be traded off against each other by weighting their relative importance in a functional, Φ, to be minimized:

| (1) |

Here is the target field value at position, rk, W (rk) is a weighting factor used to modify the accuracy of the field generated at position rk, α and β are parameters that give weight to the values of inductance, L, and resistance, R, of the coil, and the λs are Lagrange multipliers that can take any value to annul the Cartesian components (Mx, My, and Mz) of the net torque generated when the coil is energized in a static, uniform axial magnetic field. In this work, W (rk) was used only to weight the importance of the accuracy of the field in the ROS with respect to that of the field in the ROU. This was achieved by setting W (rk) = 1 if rk ∈ ROU and W (rk) = γ if rk ∈ ROS.

A matrix representing the differential of Φ with respect to ψn, λx, λy, and λz is inverted to find the optimal ψn values. ψ(r) Is then generated from ψn and contoured at equally spaced contour levels to generate the wire pattern of the coil (8).

Coil Design

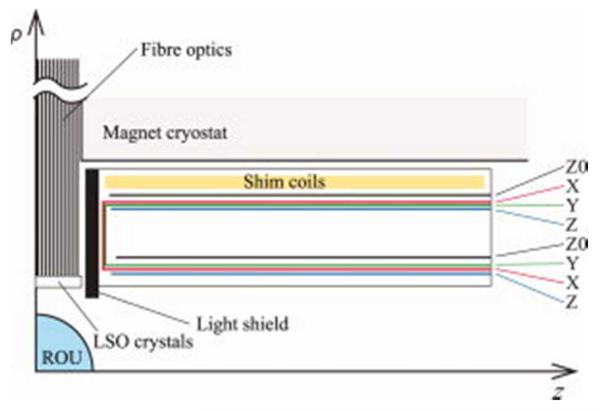

Figure 1 shows the geometry of one quadrant of the central section of the combined coil system that is symmetric about z = 0 and rotationally symmetric about the z-axis. The region provided for the gradient and shim coil set was defined by 75 mm < ρ < 177.5 mm and 55 mm < |z| < 400 mm. The resulting cylindrical surfaces on which current was allowed to flow for the Z-gradient and Z0 shim coils was therefore an arrangement of four cylindrical surfaces each (comprising a primary and shield surface either side of z = 0). An additional annular surface that connects the primary to the shield surfaces at the edges of the cylinders closest to z = 0 was added for the X- and Y-gradient coils. A nested arrangement of coils with the Y-gradient coil inside the X-gradient coil, as shown in Fig. 1, was therefore devised to optimize the performance of the gradient coils. The ROU over which for each coil was specified as a 100-mm-diameter spherical volume and the ROS was an 800-mm-long cylinder with a 200-mm radius, representing the first cold conducting surface of the cryostat. Each coil was designed by adjusting the values of α and/or β in Eq. 1 until the maximum deviation, max(ΔBz), of the axial magnetic field, Bz (rk), from the target field, , was 5%. In addition, γ was adjusted to ensure that the maximum field leakage onto the ROS, , was also low. The minimum wire spacing, Δwmin, of the coils was another engineering constraint that had to be satisfied because of the method of construction used and was set at 3.6, 3.6, 3.2, and 2.0 mm for the X, Y, Z, and Z0 coils, respectively.

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional diagram of the principal structures of the combined PET-MRI scanner, including the surfaces of the gradient coils and Z0-shim coil shown.

Construction

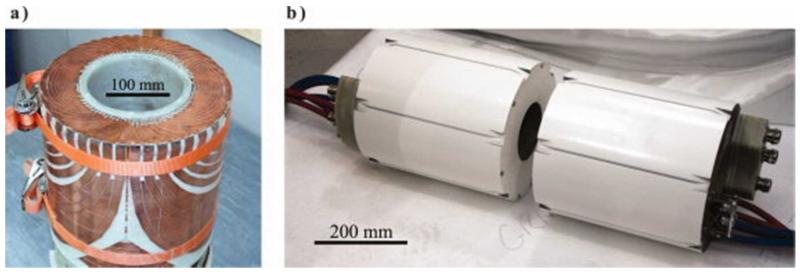

The Z-gradient coil was made using 2 mm × 3 mm (primary) and 4 mm × 3 mm (shield) insulated copper wire of rectangular cross-section that was wound into grooves machined at the appropriate positions into the cylindrical fiberglass formers. Each of the X- (shown in Fig. 3a) and Y-gradient coils was constructed from ten separate plates: two primary, two shield, and one annular plate for each half. The wire paths for each plate were formed by precision machining 2.5-mm-thick copper sheets, which were then bonded to a thin fiberglass substrate before the primary and shield plates were rolled to their correct radius. A soldered joint was required for each wire that crossed the boundaries between plates; 432 such joints were required in total for the two transverse gradient coils. Insulated copper pipe was interleaved with the gradient coil layers to provide water cooling. Each half of the coil was placed into a mould and vacuum impregnated with a bisphenol-A epoxy resin (Grilonit; Ems-Primid, Domat/Ems, Switzerland) to complete the coil set, shown in Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Photographs of the split gradient coil set (a) during construction after the addition of the outer X-gradient layer and (b) the completed gradient set. Approximate scale bars have been added to both images.

Evaluation

After the inversion of the coil properties matrix to produce the stream function values, ψn, the forward problem was solved by Biot-Savart summation over the wire paths. This yields values of the coil efficiency, η, and inductance, L, as well as field leakage onto the cryostat and field error in the ROU. FastHenry (15), a multipole-accelerated impedance extraction tool, was then used to predict values for the inductance, L, and resistance, R, of the wire pattern for a constant cross-sectional area of 2.25π mm2.

During construction, the L and R values of all the coils were measured using an inductance, capacitance, resistance (LCR)-meter and the axial magnetic field was also recorded at points over the surface of a central 100-mm-diameter spherical volume using a fluxgate magnetometer (Bartington Instruments, Witney, Oxon., UK) while the coils carried a known electric current.

Once the coils had been connected and calibrated in the hybrid PET-MRI system, a simultaneous PET-MRI experiment was carried out on a micro-Derenzo “hot cell” phantom (Data Spectrum Corporation, Hillsborough, NC) containing water mixed with 18F. The amplitude of static field was shimmed using the FASTMAP procedure (16), with a 10-cm-long, 8-cm-diameter cylindrical water phantom, and the gradient waveforms were not pre-emphasized for eddy-current compensation. The water and 18F were confined to 74 rods that had diameters of 1.2, 1.6, 2.4, 3.2, 4.0, and 4.8-mm and a length of 33-mm, as well as a surrounding tube with an inner diameter of 43 mm and a 1-mm thickness and a central tube with an inner diameter of 54 mm and a thickness of 0.5 mm. Each rod is separated from its neighboring rod by a distance equal to its diameter. The PET data were acquired using a standard 350–650 keV energy window and a 6 ns coincidence window with a total scan time of 40 min. Three-dimensional filtered back-projection reconstruction with normalization but no attenuation or scatter correction was used to produce the PET images. The MRI data were acquired in 15 min on a Bruker (Bruker BioSpin MRI GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany) console using the “GEFI” protocol and an eight-strut, transmit/receive birdcage coil. This coil and its supporting structure were designed to minimize material in the PET field of view. The GEFI sequence was repeated throughout the duration of the PET data acquisition. Finally, PET and MRI image data were coregistered using only rigid translation.

RESULTS

The inverse boundary element method required a total time of 16 h 20 min (with an Advanced Micro Devices Opteron 2.2-GHz processor, Sunnyvale, CA) to compute the system of equations for the set of four coils considered here. These data were saved and could then be repeatedly inverted with different α, β, and γ input parameters in 7 s. Calculation of the wire paths of a new coil design, along with the coils’ associated properties, typically required 1 min. The limiting factor in the design process was found to be the minimum wire spacing. Since coils of this size are naturally of low inductance, L< 100 μH, only the resistance was minimized; this is because resistance minimization is more effective at increasing the minimum wire spacing than inductance minimization for the same field error. The total calculation time could have been cut to 7 h if the inductance matrix, which was not used, had been omitted from the calculation.

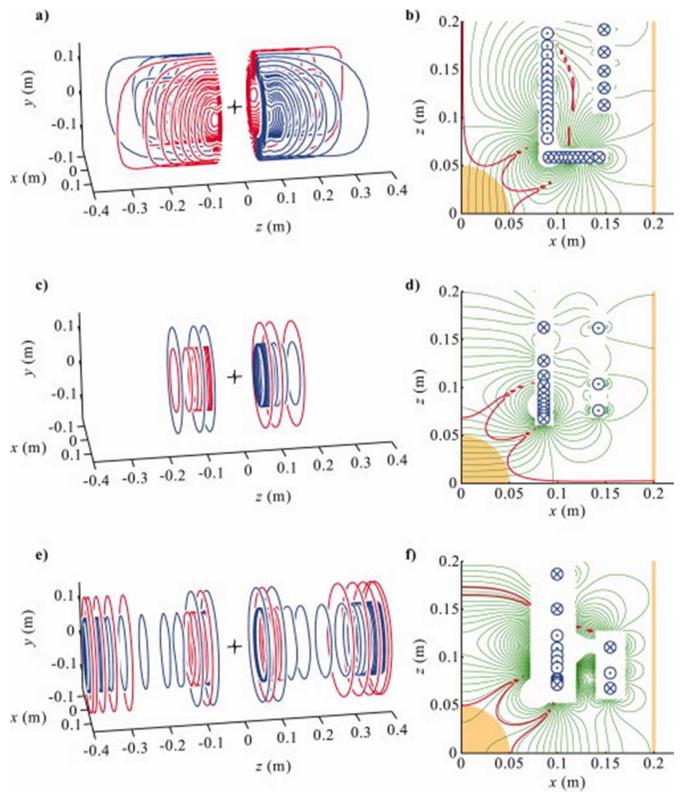

Figure 2 shows the wire paths obtained from equally spaced contours of ψ(r) for the X- and Z-gradient and Z0 shim coils. The Y-gradient coil, which is not shown here, is very similar to the X-gradient coil but rotated by 90° about the z-axis. On the right-hand side of the figure are the magnetic field maps, generated by applying the Biot-Savart expression to the digitized wire paths. In each case, these are overlaid with a contour (red) marking the position where the field deviates by 5% from the desired value (i.e., ΔBz = 5%). Photographs of the partially finished (a) and fully finished (b) coil set are shown in Fig. 3, with the X-gradient wires visible in Fig. 3a.

Figure 2.

Wires of the (a)X, (c) Z gradient, and (e) Z0 shim coils. Red wires indicate reversed current flow with respect to blue. Contour maps of the axial magnetic field generated by the coils are shown in (b),(d) and (f) with 5μTA−1 contour spacing (thin green) overlaid with the 5% field error contour (thick red), ROU (orange region), ROS (orange line), and wire positions (into, ⊗, and out of, ⊙, the contour plane).

Table 1 presents the input parameters and coil properties of the gradient and shim coils. When connected to a single 350-V, 300-A power amplifier, a 200 mTm−1 transverse magnetic field gradient could be generated, with a rise time of less than 130 μs. Efficiencies of 8.3, 6.6, 6.4, 1.1, and 1.2 mTm−2A−1 were measured for the Z2, ZX, ZY, XY, and X2-Y2 shim coils, respectively; the Z3 shim coil had an efficiency of 63 mTm−3A−1.

Table 1. Coil performance properties.

| Property | Coil | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Coil type | X-Gradient | Y-Gradient | Z-Gradient | Z0-Shim |

| IR (mm) | 89.45 | 92.95 | 85.6 | 99.55 |

| OR (mm) | 148.5 | 145.9 | 142.6 | 154.65 |

| Gap (mm) | 118 | 122 | 132 | 141a, 129b |

| β | 1.0 × 10−7 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 2.0 × 10−6 | 8.0 × 10−9 |

| γ | 0.5 | 1 | 5 | 0.7 |

| N cont | 36 | 40 | 14 | 38 |

| η, (mTm−nA−1) | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.015 |

| max(ΔBz) (%) | 4.3 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.1 |

| 2.8 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 4.7 | |

| Gmax (mTm−1) | 198 | 186 | 234 | – |

| SR (Tm−1s−1) | 2139 | 1793 | 6825 | – |

| τ (μs) | 92 | 104 | 34 | – |

| L (μH) | 108 | 121 | 40 | 159 |

| R (mΩ) | 117 | 128 | 42 | 126 |

| min(Δw) (mm) | 4.2 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| η2/L (T2m−2nA−2H−1) | 4.0 × 10−3 | 3.2 × 10−3 | 1.5 × 10−2 | 1.4 × 10−6 |

(Inner gap.)

(Outer gap.)

(Input parameters β, γ and numbers of contours of the stream function, Ncont, and coil properties including efficiency, η, maximum field error in the ROU, max(ΔBz), maximum field at the ROS, , maximum gradient strength (assuming 350-V, 300-A amplifier), Gmax, slew rate, SR, rise time, τ, inductance, L, resistance, R, minimum wire spacing, min(Δw) and a common figure-of-merit value, η2/L (n = 1 for gradient coils and n = 0 for Z0 shim coil).)

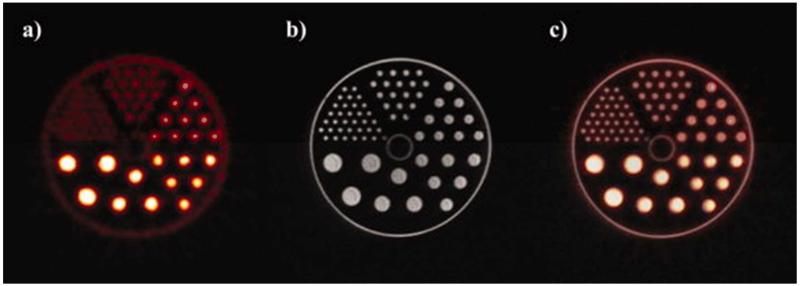

Figure 4(a–c) show the simultaneously acquired PET, MRI, and combined images of one slice through the micro-Derenzo hot cell phantom. Using the FASTMAP shimming routine, a water peak line width of ±6 Hz was obtained.

Figure 4.

One slice of the image data of the micro-Derenzo hot rod phantom with (a) the PET data, (b) the MRI data and combined image using rigid translation registration only.

DISCUSSION

The performance of a cylindrical shim or gradient coil is necessarily reduced by the inclusion of a central gap by an amount dependent on the size and shape of the gap, as well as the form of magnetic field that is to be produced. To quantify this reduction, conventional cylindrical gradient coils with the same diameter, length, and field characteristics as the equivalent split coils were also designed (data not shown). The number of turns in these coils was chosen to produce coil inductances that fell within 10% of the inductance values of the split coils presented here. The efficiencies of the split X-, Y-, and Z-gradient coils were then found to be 39, 40, and 11% lower than standard cylindrical coil equivalents. The Z-gradient coil suffers less from the presence of the gap because it naturally has a low density of wires in the central region. The efficiency of the split Z0 shim coil is, however, 87% lower than a standard cylindrical equivalent, which illustrates the particular difficulty posed by designing the split Z0 shim. Indeed, the split Z0 coil possesses many reversed turns, as shown in Fig. 2d, resulting in a low efficiency, although the homogeneity and shielding are satisfactory.

Inclusion of the annular current-carrying surfaces was essential for the successful design of X- and Y-gradient coils; it is only possible to achieve an efficiency of 118 and 132 μTm−1A−1, respectively, for coils with approximately the same inductances without the annuli. Thus, the inclusion of the annuli, which allows the wire paths on the inner cylindrical portion of the coil surface to link smoothly with those on the outer cylindrical surface, improves the achievable efficiency of these transverse gradient coils by more than a factor of 4. For the Z-gradient coil, however, windings on this surface would have increased the efficiency to just 941 μTm−1A−1 at fixed inductance, a 21% increase. The Z0 coil would have benefitted greatly in terms of performance (approximately 4-fold increase in efficiency) through inclusion of annular surfaces, but such construction was considered too complex, considering the already adequate performance of the coil designed without the annuli. A surface linking the primary coil cylinder to the shield coil cylinder has been used before in the form of annuli (17) and conical sections (18). These examples are, however, different from the coils designed here in that the linking surfaces are at the ends of the cylinders farthest away from the coil center.

The coil efficiencies calculated from the magnetometer measurements match to within 6% those predicted by Biot-Savart summation, and all the inductance measurements are within 20% of the predicted values, with most being well within 10%.

The PET data acquired from the micro-Derenzo hot rod phantom showed relatively poor spatial resolution compared to the MR data, as expected. The rigid translational registration technique was simple and assumed no geometric distortions between data sets, yet when the PET data were overlaid on the MR image, an excellent degree of overlap was observed. Further tests of the performance of the gradient set have also been performed, and no significant interaction of the PET and MRI systems has been observed.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that it is possible to design a set of gradient coils with reasonable performance for a hybrid PET-MRI system that incorporates a large central gap. This was made possible by the use of an inverse boundary element method, which allowed for the design of coils on surfaces of complex shape. The inevitable reduction in performance associated with inclusion of a central gap was mitigated by the inclusion of annular connecting surfaces between the primary and shield surfaces in the transverse gradient coils. Z-gradient coils naturally have a low current density in the central region, and therefore the Z-gradient coils performance was not so significantly reduced by the inclusion of the central gap. However, the design of the shielded Z0 shim coil was particularly difficult because the gap lay where many wires would normally reside in a conventional solenoidal coil. Adequate performance and field homogeneity were, however, achieved in the shielded Z0 shim coil.

Gradient and shim coils with a central gap of the type described here may also find use in other hybrid MRI systems, including those in which image-guided radiotherapy treatment is applied inside the scanner via an external source sited in the gap of a split magnet.

The coil set was successfully constructed and tested by measuring the magnetic field with a magnetometer and by generating simultaneous PET and MRI images of a micro-Derenzo water and 18F phantom using this unique hybrid system. Standard acquisition and reconstruction techniques were used to generate images that showed excellent correspondence between PET data and MRI data.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steve Harris, Malcolm Fairbairn, Steve Hall, and Barrie Williams for manufacturing the coil set.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaw NR, Ansorge RE, Carpenter TA. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. Vol. 13. Miami Beach, Florida: 2005. Commissioning and testing of split coil MRI system for combined PET-MR; p. 407. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucas AJ, Hawkes RC, Ansorge RE, Williams GB, Nutt RE, Clark JC, Fryer TD, Carpenter TA. Development of a Combined microPET-MR System. Technol Cancer Res Treatment. 2006;5:826–830. doi: 10.1177/153303460600500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkes RC, Fryer TD, Lucas AJ, Siegel SB, Ansorge RE, Clark JC, Carpenter TA. Initial performance assessment of a combined microPET® focus-F120 and MR split magnet system. Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record. 2008:3673–3678. NSS ’08. IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grazioso R, Ladebeck R, Schmand M, Krieg R. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. Vol. 13. Miami Beach, Florida: 2005. APD-based PET for combined MR-PET imaging; p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pichler BJ, Judenhofer MS, Catana C, Walton JH, Kneilling M, Nutt RE, Siegel SB, Claussen CD, Cherry SR. Performance Test of an LSO-APD Detector in a 7-T MRI Scanner for Simultaneous PET/MRI. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:639–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert KM, Handler WB, Scholl TJ, Odegaard JW, Chronik BA. Design of field-cycled magnetic resonance systems for small animal imaging. Physics Med and Biol. 2006;51:2825–2841. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/11/010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pissanetzky S. Minimum Energy MRI Gradient Coils of General Geometry. Measure Sci Technol. 1992;3:667–673. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poole M, Bowtell R. Novel Gradient Coils Designed Using a Boundary Element Method. Concepts Magn Reson B Magn Reson Eng. 2007;31B:162–175. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poole M. Improved Equipment and Techniques for Dynamic Shimming in High Field MRI. PhD thesis. The University of Nottingham; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roméo F, Hoult DI. Magnet Field Profiling: Analysis and Correcting Coil Design. Magn Reson Med. 1984;1:44–65. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910010107. Direct Link: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peeren GN. Stream Function Approach For Determining Optimal Surface Currents. J Comput Phys. 2003;191:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemdiasov RA, Ludwig R. A Stream Function Method For Gradient Coil Design. Concepts Magn Reson B Magn Reson Eng. 2005;26B:67–80. Direct Link: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peeren GN. Stream Function Approach For Determining Optimal Surface Currents. PhD thesis. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole M, Bowtell R. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. Vol. 16. Toronto, Canada: 2008. Azimuthally Symmetric IBEM Gradient and Shim Coil Design; p. 345. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamon M, Tsuk MJ, White JK. FASTHENRY: a Multipole-Accelerated 3-D Inductance Extraction Program. IEEE Transactions Microwave Theory Techniques. 1994;42:1750–1758. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruetter R, Boesch C. Fast, Noniterative Shimming of Spatially Localized Signals. In Vivo Analysis of the Magnetic Field along Axes. J Magn Reson. 1992;96:323–334. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimmlingen R, Gebhardt M, Schuster J, Brand M, Schmitt F, Haase A. Gradient System Providing Continuously Variable Field Characteristics. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:800–808. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10129. Direct Link: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shvartsman S, Morich M, Demeester G, Zhai Z. Ultrashort Shielded Gradient Coil Design with 3D Geometry. Concepts Magn Reson B Magn Reson Eng. 2005;26B:1–15. [Google Scholar]