Abstract

Objectives:

A cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the knowledge and practiced behaviors of gynecologists regarding oral health care during pregnancy and the association of periodontal disease with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Materials and Methods:

A questionnaire consisting of 16 questions was designed and pilot tested. One hundred and fifty gynecologists practicing in the private sector of United Arab Emirates (UAE) were approached to voluntarily participate and fill up the questionnaire during February–March 2014. Data retrieved were entered into Excel database and analyzed using SPSS.

Results:

Of the 150 gynecologists approached, 108 filled the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 72%. The majority (95.4%) acknowledged a connection between oral health and pregnancy and 75.9% agreed that periodontal disease can affect the outcome of pregnancy. Moreover, most of the gynecologists (85.2%) advised their pregnant patients to visit the dentist during pregnancy. Almost three-quarter of the participants (73%) regarded dental radiographs to be unsafe during pregnancy and more than half (59.3%) considered administration of local anesthesia to be unsafe during pregnancy.

Conclusion:

The present study demonstrated that gynecologists have a relatively high degree of knowledge with respect to the relationship of periodontal disease to pregnancy outcome. However, there clearly exist misconceptions regarding the provision of dental treatment during pregnancy. To provide better oral health care, more knowledge needs to be made available to the pregnant women and the medical community, and misconceptions regarding the types of dental treatments during pregnancy should be clarified.

Keywords: Adverse pregnancy outcomes, gynecologists, oral health, periodontal disease

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy involves complex physical and hormonal changes that have a significant impact on almost every organ system, including the oral cavity. Oral problems associated with pregnancy primarily include gingivitis and periodontal infection.[1] Pregnancy gingivitis and periodontitis is by far the most common oral disease observed amongst pregnant patients. During pregnancy, there is an increase in the hormones estrogen and progesterone. These hormones have been found to affect periodontal disease progress and wound healing.[2] Both these hormones lead to increased gingival vascularization and decreased immune response.[3] Moreover, studies[4,5] reveal that during pregnancy, there is increase in some types of microorganisms (Provetella species) which tend to utilize the steroidal hormones of pregnancy for their growth. These microorganisms increase the tendency of the gums to bleed and worsen gingival inflammation. As a result, pregnant patients have severe gingival inflammation even with reasonably low plaque levels.

Studies done in this field identified maternal periodontitis as a potential risk factor for preterm birth and low birth weight.[5,6,7,8,9,10] This potential association between maternal periodontitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes becomes an important concern because preterm birth and low birth weight are a major cause of infant mortality.[5,7]

However, what needs to be realized is the crucial role of medical health professionals in this entire issue. In order to deliver adequate and standard prenatal care to any pregnant woman, dental and medical practitioners should recognize oral health care as an integral part of the overall prenatal care. A pregnant woman is first seen by a medical health professional and she may only come to a dentist if advised to do so by her doctor. Hence, it becomes important to evaluate the knowledge of medical health professionals about periodontitis and its association with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Meanwhile, systematic data to evaluate the knowledge, awareness, and opinions of gynecologists regarding oral health care during pregnancy and the effect of maternal oral health on the pregnancy outcomes are very limited.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] To our knowledge, no study has been published that assessed the extent of healthcare providers’ knowledge regarding the association between oral health and pregnancy outcomes in the UAE. The aim of this study was to evaluate the knowledge, awareness, and opinions of gynecologists regarding oral health care during pregnancy in the UAE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this cross-sectional survey, half of the gynecologists practicing in the private sector (150 gynecologists) of three emirates, namely Dubai, Sharjah, and Ajman, of the UAE were randomly selected for inclusion, using a computer program for generation of random numbers and lists obtained from the Ministry of Health.

A structured, anonymous questionnaire was designed by the authors in English and pilot tested at Ajman University of Science and Technology (AUST), College of Dentistry. The questionnaire was pre-tested before use in the field, in order to examine the extent to which gynecologists could easily understand its content. Ten employees in AUST dental college were asked to read the cover letter, complete the questionnaires, and discuss their impressions of the questionnaire. As the questionnaires appeared to be easily understood, no changes were made. No formal examination of the validity and reliability of questionnaire responses was undertaken. The questionnaire used for survey consisted of 16 close-ended questions. The first set of questions was related to participants’ demographic characteristics like gender, age, and practice type. The other part of the questionnaire contained questions that aimed to evaluate the knowledge and practiced behaviors of the gynecologists toward oral health care of pregnant patients. The study was approved by the ethical committee of AUST. The questionnaire distribution was conducted 5 days per week from Sunday to Thursday, since Friday and Saturday are official holidays, from the beginning of February to the end of March 2014. The approached doctors were provided with an information sheet explaining the nature and purpose of the study, and were requested to sign an informed consent prior to participation. All gynecologists entered the study voluntarily. It took the majority of the participants 5–10 min to complete the questionnaires before they handed it to the researcher (MA).

Statistical analysis

All returned questionnaires were coded and analyzed. Results were expressed as the number and percentage of respondents for each question and were analyzed using SPSS statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 17.0. Chi-square test was used to evaluate the differences between the different variables, and the level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

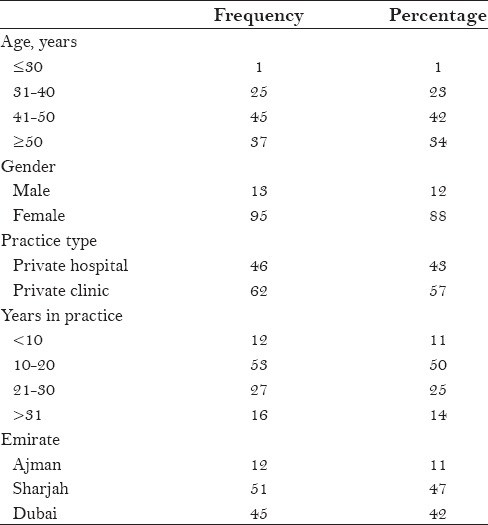

Of the 150 eligible gynecologists, only 108 agreed to participate in this study and returned completely filled questionnaires, yielding a response rate of 72%. Forty-two percent of the participants were aged between 41 and 50 years, and the majority of the participants were females (88%). More than half of them practiced in private clinics (57%), and half of them had an experience of 10–20 years (50%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data of the study participants

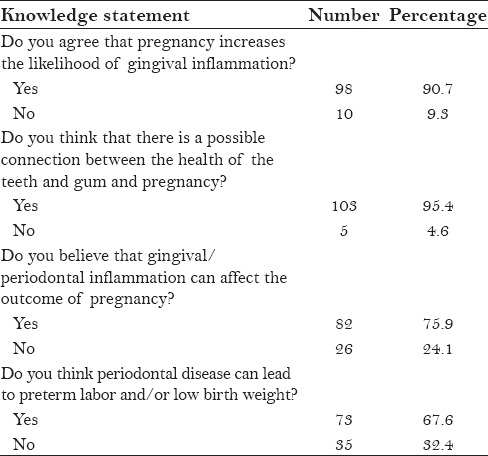

Table 2 displays the responses of the gynecologists to the questions aimed to evaluate their knowledge regarding the association between oral health and pregnancy. More than 90% of the participants agreed that pregnancy increases the likelihood of gingival inflammation. Similarly, a high percentage (95.4%) of the gynecologists acknowledged a positive association between oral health and pregnancy. In addition, 75.9% believed that gingival/periodontal inflammation can affect the outcome of pregnancy and 67.6% agreed that periodontal disease can lead to preterm labor and/or low birth weight.

Table 2.

Knowledge of gynecologists about gingival/periodontal infection during pregnancy

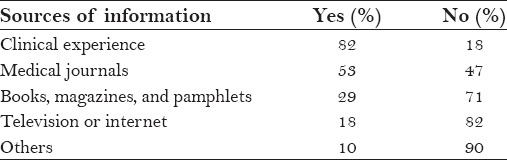

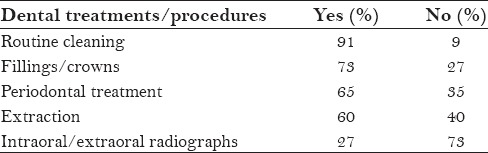

When the participants were asked about their source of information regarding oral health and pregnancy, a high percentage (82%) considered their clinical experience as the main source of information, while more than half mentioned medical journals as their source of information [Table 3]. This study revealed that the main types of treatment the gynecologists thought that their pregnant patient could receive safely were routine cleaning and fillings/crowns (91% and 73%, respectively), whereas intraoral/extraoral radiograph was considered safe to be delivered to the pregnant patients by only 27% of the gynecologists [Table 4].

Table 3.

Sources of information regarding association between oral health and pregnancy

Table 4.

Dental treatments/procedures considered safe by gynecologists during pregnancy

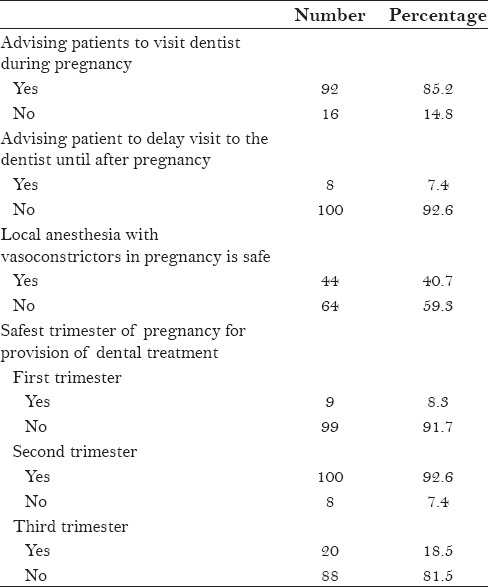

This study showed that majority of the gynecologists (85.2%) advised their pregnant patients to visit the dentist. Most of them (92.6%) regarded second trimester as the safest trimester to receive dental treatment. However, 59.3% considered administration of local anesthesia containing vasoconstrictor to be unsafe during pregnancy [Table 5]. A very high percentage (93.5%) of the gynecologists reported that their patients mentioned bleeding gums or tooth mobility during pregnancy. In addition, the majority (85.2%) of the participants felt they needed additional information about the association between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes (data not presented).

Table 5.

Opinions of gynecologists regarding dental treatment during pregnancy

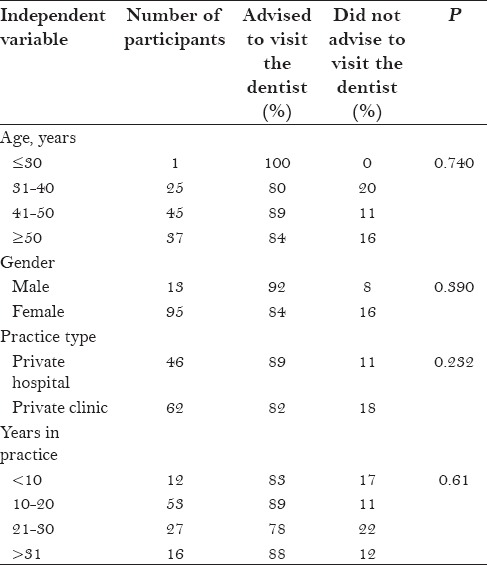

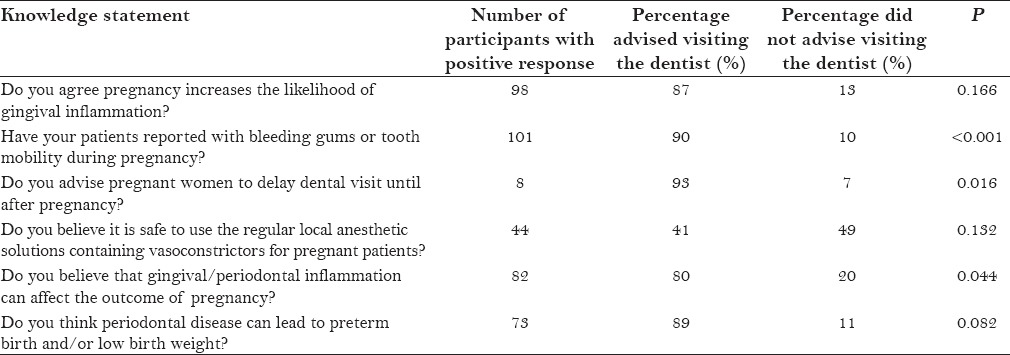

Table 6 displays the outcome of the bivariate analysis in relation to the demographic characteristics and advising pregnant patients to visit the dentist. The results did not yield any significant association between the demographic characteristics of the gynecologists and advising the patients to visit the dentist. In addition, Table 7 displays the bivariate results for the knowledge-related questions and advising dental visits during pregnancy. The results showed that there is a significant association between advising to visit the dentist and the following variables: Patients reporting bleeding gums and tooth mobility, those who were advised not to delay dental visit, and those who acknowledged an association between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Table 6.

Advising dental visits and demographic characteristics of the participants

Table 7.

Advising dental visit during pregnancy and gynecologists’ knowledge about oral health

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first published study conducted in the UAE to assess the level of knowledge of the gynecologists in relation to the association of periodontal disease and pregnancy outcomes. Overall, the level of knowledge in the present survey reflected gynecologists’ familiarity with various pregnancy-related oral health topics, which is in accordance with previous studies.[13,14,15,16] Although the overall knowledge level of the gynecologists was satisfactory in this study, however, there still exist minor misconceptions amongst gynecologists regarding provision of dental treatments during pregnancy. This is of importance to the dentists as it acts as a barrier for them in providing the most appropriate treatment to their pregnant patients. Such misconceptions should be clarified in order to stop compromising on the quality of dental care due to unnecessary fears developed among patients.

Certain limitations exist in this study. The sample size was small to make definite conclusions on the issue. In addition, the responses obtained did not necessarily reflect the actual opinions of the participating gynecologists owing to bias on their part. Also, the actual oral health status of the pregnant women who visited these gynecologists could not be assessed and was based purely on the memory of the participating gynecologists. Moreover, no data were collected from non-respondents to allow for comparison of characteristics of respondents and non-respondents. However, this study might provide baseline information for continuing education programs in future that are provided to gynecologists working in the UAE.

This study demonstrated that a high percentage (90.7%) of the gynecologists was aware of the association between oral health and pregnancy and that pregnancy increases the likelihood of gingival inflammation. Almost two-thirds (67.6%) of the surveyed gynecologists agreed that periodontal disease can lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Provision of adequate oral health care during the course of pregnancy has always been a challenge for the dental health care worker due to the potential risks to the fetus associated with the commonly prescribed drugs in dentistry and dental treatments. With the advances in the field of health, pregnancy is no longer regarded as a contraindication to the provision of quality dental care. Rather, implementing necessary dental treatment during pregnancy will lead to better pregnancy outcomes and a stress-free period of pregnancy for the expecting mother. The majority of the gynecologists (91%) considered that routine cleaning can be safely carried out during the course of pregnancy. Periodontal treatment is rather necessary during pregnancy, owing to the fact that hormonal changes taking place during pregnancy render the women more susceptible to plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation.[19] Any acute periodontal infection should likewise be treated as soon as possible to avoid any harm to the mother and the developing fetus.[20,21]

Pregnant women may experience higher incidence of dental caries due to the several physiological changes they are undergoing and the resultant changes in their eating habits and oral hygiene practices. Furthermore, increased tooth erosion is also observed among pregnant women as a result of the frequent vomiting and nausea they experience during pregnancy.[19,22] Provision of restorative therapy during pregnancy, therefore, becomes important to help women maintain their oral health during this crucial period. Restoring the decayed teeth helps to stop the progress of dental decay and prevents the transmission of the bacteria responsible for dental decay from the expecting mother to the developing fetus.

Despite the high awareness of gynecologists regarding the association between oral health and pregnancy, their responses to questions aimed to evaluate their knowledge about the different types of dental treatments that can be safely administered to pregnant patients were not satisfactory. In response to the question whether it is safe to take intraoral/extraoral radiographs for a pregnant patient, most of the gynecologists (73%) answered “No.” Dental radiographs play an important role in diagnosis and treatment of many dental conditions. Studies[22,23] have reported that it is safe to take necessary intraoral and extraoral dental radiographs of pregnant women, and they do not pose any risk to the developing fetus. However, it is recommended to use protective lead aprons and thyroid collar to shield the sensitive areas. Moreover, the radiation dose should be lowered as much as possible, yet sufficient enough to yield a standard radiograph, in order to minimize the exposure of the pregnant patient to X-ray radiations.[24]

Another frequent misconception in relation to dental treatment of pregnant women is avoiding the use of local anesthetic agents containing vasoconstrictors. Vasoconstrictors prolong the duration of anesthesia and ensure efficient pain control during the course of dental treatment. It is essential to provide pain-free dental treatment as pain increases the stress levels and also leads to hormonal changes which can be harmful for pregnant patients. The majority (59.3%) did not believe that local anesthesia containing vasoconstrictor is safe for the pregnant woman and her baby. Research[25] has shown that the use of regular dental anesthetics containing vasoconstrictors during pregnancy is safe, provided intravascular injections are avoided. The vasoconstrictors are present in a very small amount in the anesthetic solution and, therefore, pose no risk to the fetus or the pregnancy itself.

In this study, majority of the gynecologists considered the second trimester of pregnancy as the safest for provision of dental treatment. However, owing to the various physiological changes occurring during pregnancy, the dental treatments and procedures need slight modifications and considerations to prevent any harm to the mother and fetus. Research has constantly verified that dental treatment can be safely administered during any of the three trimesters of pregnancy, but due to the morning sickness experienced by most pregnant women during the first trimester and the great deal of risk of postural hypotension during the third trimester, second trimester of pregnancy is the ideal period of delivering efficient dental care.[23,24]

The majority of the gynecologists were interested to have additional information regarding periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Therefore, training gynecologists on how to provide a visual screening for oral health problems is also recommended. For practicing gynecologists, continuing education courses on periodontal disease and systemic conditions could be developed by the dental community in the UAE. Also, having oral health referral sources available for gynecologists so that they can easily refer pregnant women for oral health care needs might facilitate the process and promote better oral health care for pregnant women in the UAE.

In agreement with the finding of Al Habashneh and coworkers,[12] the present study found no association between advising dental visits during pregnancy and gynecologists’ age and gender. This further showed that even in the older age group and among female doctors, no significant increase in advising dental visit during pregnancy was observed. Majority of the gynecologists who advised their patients to visit the dentist were those to whom the patients presented with bleeding gums and tooth mobility and those who believed that periodontitis can affect the outcome of the pregnancy.

Based on our findings, it is highly recommended that gynecologists in the UAE should inform expectant mothers about the link between gum disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes. The most recent finding of Hashim[26] says that a large proportion of the pregnant women in the UAE reported oral health problems; yet, more than 40% of those women had not visited a dentist during their pregnancy and a majority of them utilized dental services when they had dental pain only. Therefore, gynecologists need to refer every pregnant patient to an oral health care provider if she has not already seen one. More investigations are still needed to evaluate the impact of dental education intervention on the utilization of dental services during pregnancy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge all the gynecologists who participated in this study. This study was not supported or funded by any research grant.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with respect to the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gajendra S, Kumar JV. Oral health and pregnancy: A review. NY State Dent J. 2004;70:40–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Page RC, Kornmen KS. The pathogenesis of human periodontitis: An introduction. Periodontal 2000. 1997;14:9–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apoorva SM, Suchetha A. Effect of sex hormones on the periodontium. Indian J Dent Sci. 2010;2:36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alchalabi HA, Al Habashneh R, Jabali OA, Khader YS. Association between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes in a cohort of pregnant women in Jordan. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;40:399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baskaradoss JK, Geeverghese A, Al Dosari AA. Causes of adverse pregnancy outcomes and the role of maternal periodontal status-a review of the literature. Open Dent J. 2012;56:79–84. doi: 10.2174/1874210601206010079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin C, Segura-Egea JJ, Martínez-Sahuquillo A, Bullón P. Correlation between infant birth weight and mother's periodontal status. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han YW. Oral health and adverse pregnancy outcomes - what's next? J Dent Res. 2011;90:289–93. doi: 10.1177/0022034510381905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saddaki N, Bachok N, Hussain NH, Zainudin SL, Sosroseno W. The association between maternal periodontitis and low birth weight infants among Malay women. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:296–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy BV, Tanneeru S, Chava VK. The effect of phase-I periodontal therapy on pregnancy outcome in chronic periodontitis patients. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34:29–32. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.829029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S, Kumar A, Kumar N, Verma S, Soni N, Ahuja R. Periodontal Disease and adverse pregnancy outcome-A study. Pak Oral Dent J. 2011;31:163–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilder R, Robinson C, Jared HL, Lieff S, Boggess K. Obstetricians’ knowledge and practice behaviors concerning periodontal health and preterm delivery and low birth weight. J Dent Hyg. 2007;81:81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Habashneh R, Aljundi SH, Alwaeli HA. Survey of medical doctors’ attitudes and knowledge of the association between oral health and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:214–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muwazi L, Rwenyonyi CM, Nkamba M, Kutesa A, Kagawa M, Mugyenyi G, et al. Periodontal conditions, low birth weight and preterm birth among postpartum mothers in two tertiary health facilities in Uganda. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:42. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nutalapati R, Ramisetti A, Mutthineni RB, Jampani ND, Kasagani SK. Awareness of association between periodontitis and PLBW among selected population of practising gynecologists in Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:735. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.93474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wooten KT, Lee J, Jared H, Boggess K, Wilder RS. Nurse practitioner's and certified nurse midwives’ knowledge, opinions and practice behaviors regarding periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Dent Hyg. 2011;85:122–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocha JM, Chaves VR, Urbanetz AA, Baldissera Rdos S, Rösing CK. Obstetricians knowledge of periodontal disease as a potential risk factor for preterm delivery and low birth weight. Braz Oral Res. 2011;25:248–54. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242011000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laslowski P, Politano GT, Raggio DP, Silva SR, Imparato JC. Physician's knowledge about dental treatment during pregnancy. RGO-Rev Gaúcha Odontol Porto Alegre. 2012;60:297–303. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patil S, Thakur R, Madhu KM, Paul ST, Gadicherla P. Oral health coalition: Knowledge, attitude, practice behaviours among gynecologists and dental practitioners. J Int Oral Health. 2013;5:8–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singla N, Singla R. Oral Health Care during pregnancy. Guident. 2013;6:64–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.López R. Periodontal treatment in pregnant women improves periodontal disease but does not alter rates of preterm birth. Evid Based Dent. 2007;8:38. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weidlich P, Moreira C, Fiorini T, Musskopf ML, da Rocha JM, Oppermann ML, et al. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy and strict plaque control on preterm/low-birth weight: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral investig. 2013;17:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0679-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rainchuso L. Improving oral Health outcomes from pregnancy through infancy. J Dent Hyg. 2013;87:330–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar J, Samelson R. Oral health care during pregnancy recommendations for oral health professionals. NY State Dent J. 2009;75:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Originating Council. Guideline on Oral Health Care for the Pregnant Adolescent. Am Acad Pediatr Dent. 2007;33:137–41. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendia J, Cuddy MA, Moore PA. Drug therapy for the pregnant dental patient. (574-6).Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2012;33:568–70, 572. passim; quiz 579, 596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashim R. Self-reported oral health, oral hygiene habits and dental service utilization among pregnant women in United Arab Emirates. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10:142–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2011.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]