Abstract

Eps8 controls actin dynamics directly through its barbed end capping and actin-bundling activity, and indirectly by regulating Rac-activation when engaged into a trimeric complex with Eps8- Abi1-Sos1. Recently, Eps8 has been associated with promotion of various solid malignancies, but neither its mechanisms of action nor its regulation in cancer cells have been elucidated. Here, we report a novel association of Eps8 with the late endosomal/lysosomal compartment, which is independent from actin polymerization and specifically occurs in cancer cells. Endogenous Eps8 localized to large vesicular lysosomal structures in metastatic pancreatic cancer cell lines, such as AsPC-1 and Capan-1 that display high Eps8 levels. Additionally, ectopic expression of Eps8 increased the size of lysosomes. Structure–function analysis revealed that the region encompassing the amino acids 184–535 of Eps8 was sufficient to mediate lysosomal recruitment. Notably, this fragment harbors two KFERQ-like motifs required for chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). Furthermore, Eps8 co-immunoprecipitated with Hsc70 and LAMP-2, which are key elements for the CMA degradative pathway. Consistently, in vitro, a significant fraction of Eps8 bound to (11.9± 5.1%) and was incorporated into (5.3± 6.5%) lysosomes. Additionally, Eps8 binding to lysosomes was competed by other known CMA-substrates. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching revealed that Eps8 recruitment to the lysosomal membrane was highly dynamic. Collectively, these results indicate that Eps8 in certain human cancer cells specifically localizes to lysosomes, and is directed to CMA. These results open a new field for the investigation of how Eps8 is regulated and contributes to tumor promotion in human cancers

Keywords: Eps8, lysosome, autophagy, pancreatic cancer, actin, lamp

Introduction

The epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8) is a 97 kDa protein that was originally indentified as a substrate for the kinase activity of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Early results demonstrated that Eps8 increased epidermal growth factor (EGF) responsiveness, thus contributed to malignant transformation in tumor cells [1, 2]. There is now growing evidence that Eps8 plays an important role in promotion of various solid malignancies, including colon, squamous cell, thyroid and cervical cancer [3–7]. We recently reported that Eps8 expression is enhanced in metastatic pancreatic cancer cells when compared to cells from the primary tumor [8]. Moreover, high Eps8 expression in metastatic cells was associated with increased cell motility and accumulation of Eps8 at actin dynamic sites, e.g. the leading edge of the cells.

The Eps8 molecule controls actin remodeling through multiple interactions. The C-terminal “effector region” directly binds F-actin and caps actin barbed ends [9]. In addition, Eps8 participates in the activation of the small GTPase Rac in a tri-protein complex with Abi1 and Sos1, and synergizes with IRSp53 to bundle actin filaments [10]. A number of recent evidence indicates that actin dynamics and endocytic machineries are intimately related. This notion appears to apply also in the case of Eps8. Rac-signaling through Eps8 can be hampered by binding of RN-tre, a GTPase activating protein (GAP) for Rab5, to the src homology-3 (SH3) domain of Eps8, leading to disruption of the Eps8-Abi1-Sos-1 complex and to the deactivation of Rab5, which in turns regulates the internalization of EGFR [11]. Intriguingly, Rab5-dependent endocytosis and early endosome trafficking have recently been shown to be required for Rac-mediated, spatially restricted actin remodeling at the cell periphery [12].

Within this context, Eps8 has all the features to predict that it might be an important regulatory element mediating the cross talk between membrane and actin dynamics, which utlimately is required to generate propulsive force at the leading cell edge upon motogenic stimuli. However, whether Eps8 directly participates in membrane internalization and/or endomembrane trafficking remains unclear. Since there is little known about the degradation of Eps8 [13], it might be possible that the regulatory function of Eps8 is controlled through its expression levels.

Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is a lysosomal for the selective degradation of cytosolic proteins [14]. Unlike other forms of autophagy, CMA is a cellular process that mediates the direct translocation of individual proteins across the lysosome membrane for their degradation in the lysosome [15]. CMA activity decreases with age and has shown to be altered in different human pathologies. Malfunctioning autophagy has been closely linked to oncogenic signaling [16].

Here, we investigate a novel association of Eps8 to the lysosomal compartment in human cancer cells and describe its degradation through CMA.

Material and Methods

Expression vectors, antibodies, reagents and siRNA

Vectors encoding for GFP fusion proteins were engineered in the pEGFP C1 plasmid (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) by cloning the appropriate fragments, obtained by recombinant PCR, in frame with the GFP moiety as described recently [17]. All constructs were sequence verified. Details are available upon request. Cell transfection was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The antibodies used were: mouse monoclonal anti-Eps8 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), rabbit polyclonal anti-Eps8 [1], mouse anti-EEA1 (clone 14, BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-EGFR (sc-03, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany), mouse anti-LAMP-1 and mouse anti-LAMP-2 (clones H4A3 and H4B4, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, IA), mouse anti-Hsc70 (clone 13D3, Novus Biologicals, Inc., Littleton, CO). The monoclonal anti-Abi1 and anti-IRSp53 antibodies were generated as previously described [9, 10].

LysoTracker (DND-99, Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) was applied at 100 nM and added to the cell medium for 2 h before further processing. Rhodamine-EGF (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) was used at 30 ng/ml for the indicated time periods under serum-free conditions. To inhibit actin polymerisation, cytochalasin D (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) was added to the cells at 1 μg/ml for 30 min. Inhibition of lysosomal acidification and protein degradation was achieved using bafilomycin A1 (Sigma) at 100 nM for 60 min. The effect of bafilomycin was proved by absence of LysoTracker uptake into the lysosomes.

Cell lines

Human pancreatic cancer cell lines (AsPC-1, Capan-1, PANC-1) and HeLa cells were purchased from ATCC (Rockville, MD). Cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 (PAA Laboratrories GmbH, Cölbe, Germany) without antibiotics and supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. For immunofluorescence analysis, cells were grown on collagen A-coated (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) glas coverslips for at least 2 days.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal laser scanning microscopy

Briefly, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 5 min, and blocked in blocking solution (2% FBS, 2% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% gelatin in PBS) followed by incubation with the primary antibody for 60 min. Colocalization analysis with F-actin was performed using fluorochrome (Alexa488)-conjugated phalloidin. Antigen-antibody complexes were visualized with Cy3 (1:200)- or fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC, 1:25)-conjugated secondary antibodies from sheep (Sigma). As negative controls, the primary antibodies were replaced with rabbit or mouse IgG, respectively, and absence of immunoreactivity was confirmed. Confocal imaging was performed on a TCS-SP laser-scanning microscope using the 40x or 63x oil-immersion objectives (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany).

For living cell confocal imaging, cells were grown on 25 mm glas cover slips and transfected with Eps8-GFP and incubated with LysoTracker dye for 2 h. The cover slips were then placed in an Attofluor® cell chamber (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) which was mounted on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope and kept at 37°C during imaging.

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP)

FRAP analysis was performed on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope using the 63x oil immersion objective. Cells were grown in in 35-mm Petri dishes containing a coverslip insert (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA) and transfected with Eps8-GFP plasmid. After three frames (12% laser intensity), a boxed region of interest (ROI) containing a lysosome with Eps8-GFP was bleached using 100% laser power at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. Repetitve images were acquired every 6 s (and later every 10 s) as the fluorescence recovered using 12% laser intensity. Fluorescence recovery was analyzed using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). First, for each frame of a timelapse series, the fluorescence intensity of a ROI containing the area of the cell that was photobleached was determined (F1). Next, the fluorescence intensity of a ROI containing a non-bleached cytoplasmic region was determined for each frame (F2). A normalized fluorescence intensity value (Fn) was then obtained using F1/F2 = Fn. The background fluorescence intensity (Fb) was set as Fn of the first frame after photobleaching, and this value was subtracted from all frames such that the fluorescence intensity value for the ROI in a given frame equals Fn – Fb, and this value is zero for the first frame after photobleaching. The amount of fluorescence recovery was then calculated as the fluorescence intensity value of a given frame divided by the fluorescence intensity value of the frame immediately before photobleaching and was expressed as a percentage.

Cell lysis, co-immunoprecipitation and immunoblot

AsPC-1 or HeLa ells were briefly rinsed with PBS and scraped into a lysis buffer containing 50 mM Hepes (pH 7,5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors (complete Mini EDTA free, Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 13200 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The protein concentration of the lysates was determined using the BCA-Kit (BCA Protein Assay, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). For immunoprecipitation, 1 μl of the primary antibody (polyclonal anti-Eps8) was added to lysates containing 1000 μg protein, and precipitated over night at 4°C by adding 25μl of protein A Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare Bio-Science GmbH, Munich, Germany). The beads were then centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, washed with lysis buffer for three times, and then analyzed by immunoblot.

For immunoblot, protein samples were heated to 99°C for 3 min and were separated in a 4–12% gel (NuPAGE, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After blotting on a nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad), membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk or Slim Fast powder (Slim Fast, Allpharm Vertiebs-GmbH, Germany) diluted in TBS-Buffer (Amresco, MoBiTec, Goettingen, Germany) at pH 7.5 with 0.05% Tween for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were then incubated with the primary antibody (mouse anti-Lamp2 1:1000, mouse anti-eps8 1:5000, mouse anti-Hsc70 IgM 1:1000) in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C, rinsed for 1 h with washing buffer and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After additional washes, the blots were incubated in chemiluminescence solution (ECL; Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany) for 2 min and exposed to an X-ray film. Before further primary antibody incubations, the membrane was exposed to stripping buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 45 min at 37°C.

Protein purification and uptake of substrate proteins by isolated lysosomes

His–Eps8 FL was purified from Sf9 insect cells. Briefly, Sf9 cells infected with the appropriate virus were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5% glycerol, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), 1 mM NaF and 1 mM NaVO4. His–Eps8 was purified using Ni–NTA-agarose (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) following standard procedures. The purified proteins were dialized against MOPS buffer (10 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) pH 7.3, 0.3 M sucrose) before use for lysosomal uptake assays.

Transport of purified proteins into isolated lysosomes was analyzed using a previously described in vitro system [18–20]. Eps8 was incubated with freshly isolated intact rat liver lysosomes in MOPS buffer for 20 min at 37°C. Where indicated, lysosomes were pre-incubated with a cocktail of proteinase inhibitors for 10 min at 0°C [18]. Any additional protein added to the incubation medium was dissolved in MOPS buffer and when necessary pH was adjusted again to 7.3. At the end of the incubation, lysosomes were collected by centrifugation, washed with MOPS buffer and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblot with an antibody specific for Eps8. Transport was calculated by subtracting the protein associated to lysosomes in the presence (protein bound to the lysosomal membrane and taken up by lysosomes) and absence (protein bound to the lysosomal membrane) of inhibitors of lysosomal proteases, as described [21, 22]. In the absence of protease inhibitors, the substrate that reaches the lysosomal lumen is rapidly degraded and the only substrate remaining is that bound to the lysosomal membrane. If lysosomal proteases are blocked, both the membrane-bound protein and that translocated into the lumen can be detected. Uptake was calculated as the difference between the amount of substrate associated with protease inhibitor-treated lysosomes and that bound to the lysosomal membrane without protease inhibitors.

Results

We recently described that Eps8 localizes to dynamic actin structures, i.e. to the tips of F-actin filaments and filopodia, and to the leading edge of pancreatic cancer cells, and that various pancreatic cancer cell lines expressed different mRNA and protein levels of Eps8 according to the following order: PANC-1<Capan1<AsPC-1 [8].

In addition to the spot-like, F-actin-associated pattern of Eps8 in the cells (PANC-1, Fig. 1A, B), endogenous Eps8 strikingly localized also to large vesicular structures in other pancreatic cancer cells. This staining pattern was particular prominent in cells derived from metastasis (Capan-1, Fig. 1C, D), or from malignant ascites (AsPC-1, Fig. 1E, F) that express relatively high levels of Eps8 [8]. In these cells, Eps8 was present on the total circumference of vesicular structures that were predominantly located at the perinuclear region (Fig. 1 G, H). The average diameter of the vesicular structures, such as the one indicated by the arrow in Fig. 1H, was 0.77 μm.

Figure 1. Endogenous Eps8 localized to vesicular structures in the human pancreatic cancer cells AsPC-1 and Capan-1.

(A, B) In the pancreatic cancer cell line PANC-1, Eps8 showed a spot-like pattern associated with F-actin structures (merged insert in B). (C, D) In Capan-1 cells, endogenous Eps8 strongly localizes to large vesicular structures. These vesicular structures were negative for F-actin. (E, F) Likewise, Eps8 localizes to vesicular structures in AsPC-1 cells. (G) Representative antibody staining of endogenous Eps8 in an AsPC-1 cell. Eps8 stained the lamellipodium (arrow), and large vesicles, that are mostly located at the perinuclear region. (H) Higher magnification (insert in G) clearly demonstrates Eps8 positivity at the vesicular membrane. The diameter of the indicated vesicle (arrow) was 0.77 μm. Image widths represent: (A, B) 80 μm, (C–F) 50 μm, (G) 60 μm, (H) 29 μm.

To identify the nature of these vesicular compartments, we analyzed the colocalization of Eps8-GFP with specific markers of different endocytic organelles (Fig. 2). Eps8-positive vesicles were devoid of the early endosome marker 1 (EEA1, Fig. 2D) and Rab5 (not shown), but enriched in the lysosome marker LAMP-1. Moreover, the vesicular lumen was strongly enriched with the LysoTracker dye, thus defining Eps8-positive vesicular structures as bona fide lysosomes. Confocal time-lapse imaging of Eps8-GFP in AsPC-1 and HeLa cells revealed that the lysosomes were mostly stationary (see Supplementary information, Fig. S1–2). Inhibition of actin polymerisation with cytochalasin D did not change the lysosomal association of Eps8 (see Supplementary information, Fig. S3), indicating that actin dynamics is required neither for the formation of these structures nor for the recruitment of Eps8. Interestingly, Eps8 recruitment to lysosomal membranes persisted also after inhibition of lysosomal acidification with bafilomycin A1 (see Supplementary information, Fig. S4).

Figure 2. Eps8-positive vesicular structures were identified as lysosomes.

AsPC-1 cells were transfected with full-length Eps8-GFP and then stained for markers of the early and late endocytic compartment (A–C) As proof-of-principle, Eps8 antibody staining revealed a full overlap with the GFP-fluorescence. (D–F) Endosomes positive for the early endosome marker 1 (EEA1) were disctinct from Eps8-positive vesicles. (G–I) Eps8 colocalized with the lysosome membrane marker LAMP-1 to lysosomes. (J–L) Moreover, the lumen of the Eps8-positive vesicles was enriched with the LysoTracker dye. The same results were yielded with antibody staining of endogenous Eps8 and in HeLa cells. Together, these data strongly suggest, that the Eps8-positive vesicles are lysosomes. Image widths represent: (A–C) 69 μm, (D–F) 49 μm, (G–I) 65 μm, (J–L) 39 μm.

Since Eps8 is a substrate of the EGFR kinase activity, we next analyzed whether Eps8 is directed to lysosomes through its direct association with EGFR or via receptor-mediated internalization. To this end, rhodamine-labeled EGF (rhEGF) ligand was used to induce EGFR internalization and to track its cognate receptor along the endocytic route (see Supplementary information, Fig. S5). In the case of the EGFR, ligand remains bound and signalling from the complex remains active until receptors can be sequestered in multivesicular bodies for subsequent degradation in the lysosome [23]. Only few vesicles, however, were focally positive for both EGF or EGFR and Eps8, while the vast majority of them display only Eps8 along the whole lysosome membrane (Fig. S5: E, F), arguing that EGFR binding is presumably not responsible for the recruitment of Eps8 to lysosomes. Consistently, most rhEGF was not found in colocalization with late endosomes/lysosomes as indicated by the LAMP-1 co-staining (Fig. S5, G–I).

Likewise, the Eps8 binding partners Abi1 and the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase substrate of 53 kDa (IRSp53) did not localize to Eps8 at lysosomes (not shown).

Our previously published data showed that AsPC-1 and Capan-1 cells express relatively high levels of the Eps8 protein compared to other pancreatic cancer cell lines, e.g. BxPC-3 or PANC-1 [8]. In the former cells, endogenous Eps8 displayed a vesicular-lysosomal distribution, but we did not know whether this was specific for some pancreatic cancer cells, or a general effect of high Eps8 expression. We therefore examined the effect of ectopic expression of the Eps8 full-length protein in HeLa cells, and its effect on lysosomal localization and morphology. In HeLa cells, endogenous Eps8 was not observed at lysosomes, but overexpressed Eps8-GFP extensively localized to lysosomes (Fig. 3 A–C). In AsPC-1 or Capan-1 cells, Eps8 expression also led to a slight, but significant increase in lysosome size (Fig. 3 D–F). This could be quantified analyzing lysosomal size in AsPC-1 cells overexpressing either full-length Eps8-GFP (Fig. 3G, H) or the empty pEGFP C1 vector as control (Fig. 3I).

Figure 3. Increased expression of Eps8 promotes Eps8 recruitment to lysosomes and influences lysosomal morphology.

Different cancer cell lines overexpressing full-length Eps8-GFP were co-stained with the lysosome membrane marker LAMP-1. (A–C) Endogenous Eps8 did not localize to lysosomes in untransfected HeLa cells. After overexpression, Eps8-GFP was observed at lysosomes in HeLa cells. (D–F) Endogenous Eps8 was present at lysosomes in Capan-1 cells. In cells overexpressing Eps8-GFP, the lysosomes appeared larger. (G–I) To quantify whether Eps8 overexpression increases lysosome size, AsPC-1 cells were incubated with LysoTracker dye and either transfected with full-length Eps8-GFP (G), or with the empty EGFP C1 vector. Lysosome sizes (according to LysoTracker fluorescence) were measured with the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) in >200 lysosomes each, and were significantly larger in Eps8-GFP transfected cells (p<0.03, Student t-Test, I). Image widths represent: (A–C) 36 μm, (D–F) 89 μm, (G, H) 60 μm.

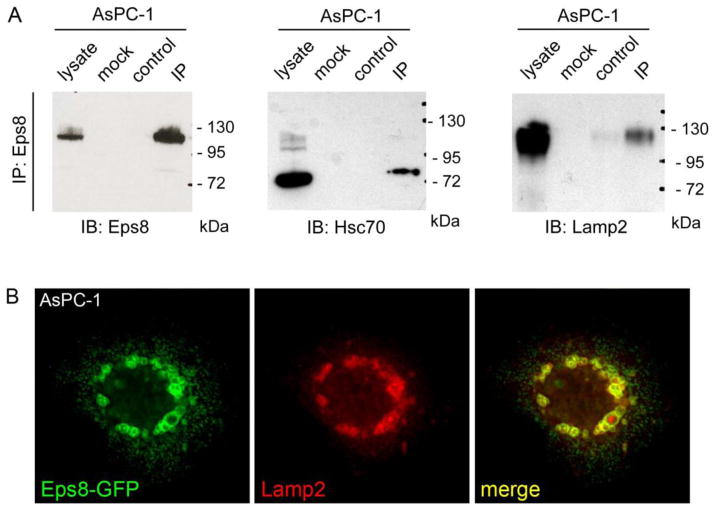

To identify the protein region that mediates lysosomal binding of Eps8, AsPC-1 cells were transfected with various fragments of Eps8 fused to GFP, and their colocalization with the lysosome marker LAMP-1 was examined (Fig. 4). This analysis revealed that the first 1-535 amino acids were sufficient for lysosomal recruitment. This fragment lacks both, the SH3 and the “effector region” that are responsible for F-actin and Abi1 binding, respectively. We concluded that the “effector region” and the SH3 domain are not required for Eps8-trafficking to lysosomes. The use of additional fragments of Eps8 permitted to restrict the minimal region required for lysosomal targeting to amino acids 184 and 535 (Fig. 5). Notably, this latter region of Eps8, in addition to include the putative EGFR binding region [13], also contains two KFERQ-like pentapeptide motifs, which are commonly required for chaparone-mediated autophagy (CMA) [14]: QVDVR (amino acids 226-230) and QEIKR (amino acids 470-474). These motifs are characteristic for cytosolic proteins that undergo lysosomal degradation through the CMA pathway, and are recognized by the heat shock cognate protein of 73 kDa (Hsc70) [14]. The interaction with Hsc70 targets the substrate to the lysosomal membrane, where it interacts with one LAMP-2 isoform (LAMP-2A) before being translocated across the lysosomal membrane into the lumen [14]. Thus, we predicted that if Eps8 were a substrate for CMA, it should interact with Hsc70 and LAMP-2. Consistently, Hsc70 and LAMP-2 co-immunoprecipitated with Eps8 in AsPC-1 cells (Fig. 6). Additionally, LAMP-2 colocalized with Eps8 at lysosomes in AsPC-1 cells.

Figure 4. Identification of the protein region of Eps8, that is sufficient to mediate lysosomal binding.

Various Eps8 fragments, all engenineered as GFP fusion proteins were checked for colocalization with the lysosomal markers LAMP-1 or LysoTracker (not shown) after transfection of AsPC-1 cells or HeLa cells (not shown). (A–C) The N-terminal fragment 1-535 localized to lysosomes that were positive for LAMP-1 (insert). Since this fragment lacks the SH3 and the “effector region” domain, it did not localize to actin-associated structures as the endogenous Eps8. (D–F) The N-terminal 1-184 fragment did not localize to lysosomes. (G–I) The fragment 180-821 localized to lysosomes and actin-associated structures, e.g. the lamellipodium. (J–L) The fragment 535-821 only localized to actin-associated structures. Image widths represent 40 μm.

Figure 5. Domain organization of Eps8 and schematic of the various Eps fragments with their binding capability to lysosomes.

Human Eps8 is 821 amino acids (aa) long. The domains, predicted by analysis of the primary sequence, are indicated: a phophotyrosine binding protein domain (PTB, aa: 60-197), the putative epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) binding region (aa: 296-362), the src-homology 3 (SH3) domain (aa: 535-586) mediating the interaction with Abi1 and RN-tre, and the C-terminal “effector region” (aa: 648-821) responsible with the interaction with Sos1 and F-actin.

Binding of the various Eps8 fragments (amino acid boundaries are given on the left of the fragments) to lysosome is indicated on the right. Lysosmal binding was mediated by the amino acids 184-535. In this region, we identified two KFERQ-like motifs (aa: 226, QVDVR; aa: 470: QEIKR).

Figure 6. Eps8 binds Hsc70 and Lamp2.

(A) Endogenous Eps8 was precipitated in AsPC-1 cells and coimmunoprecipitated Hsc70 and LAMP-2. Lysate was total AsPC-1 cell lysate (40 μg), mock control was lysis buffer without cells, control was cell lysate (1 mg) with beads only, and IP was cell lysate (1 mg) with precipitating antibody (polyclonal rabbit anti-Eps8) and beads. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of full-length Eps8-GFP and LAMP-2 in AsPC-1 cells. Eps8 and LAMP-2 colocalized at lysosomes (image width represents 58 μm).

Next, we assessed whether the association and relocalization of Eps8 to lysosomes could be reconstituted in a cell-free system. To this end, we examined lysomal binding and uptake of purified Eps8 into isolated rat liver lysosomes (Fig. 7). The amount of lysosomal binding and uptake of Eps8 was 11.9±5.1% and 5.3±6.5% of the total amount of protein added, respectively, and are comparable to those of other known CMA substrates (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, the lysosomal binding of Eps8 was specific since it could be readily competed by the well-characterized CMA substrates glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrongenase (GAPDH) and RNase A in a concentration dependent manner, but not by ovalbumin (a protein that does not contain a CMA-targeting motif) (Fig. 7C, D).

Figure 7. Chaperone-mediated autophagy of Eps8.

Freshly isolated rat liver lysosomes treated or not with protease inhibitors (+PI) as indicated, were incubated with purified Eps8 for 20 min at 37C in an isotonic media. Lysosomes collected at the end of the incubation by centrifugation were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot for Eps8. Where indicated well-characterized CMA substrate proteins (GAPDH and RNase A) or nonCMA substrate proteins (ovalbumin) were added simultaneously to the reaction. (A) Representative immunoblot. (B) The amount of EPS8 associated to lysosomes was calculated by densitometric quantification of the immunoblots. Values are expressed as percentage of the total EPS8 added to the reaction and are mean + S.E. of 8 independent reactions. Uptake was calculated as the amount of Eps8 associated to lysosomes treated with protease inhibitors (association) after discounting the amount associated to untreated lysosomes (binding). (C) Effect of the addition of increasing concentrations of different proteins on the binding of EPS8 to lysosomes calculated by densitometric quantification of immunoblots as the one shown in the insert. Values are expressed as percentage of protein added and are mean + S.E. of 4–8 independent reactions. (D) Percentage of inhibition on the binding of Eps8 to lysosomes after addition of the indicated concentrations of proteins, calculated from the experiments described in C.

The kinetics of Eps8 at the lysosomal membrane was further characterized by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis. Fluorescence recovery asymptotically approached 80% after 120 s (mobile fraction), demonstrating that the bulk of Eps8 is recruited to the lysosome membrane in a dynamic fashion (Fig. 8). The diffusion rate τD was 27 s.

Discussion

Here, we describe a novel and unexpected association of endogenous Eps8 with the lysosomal compartment in human cancer cell lines. This localization was never reported before. Eps8 has only been associated with dynamic actin sites and the early endocytic compartment [1, 9–11, 17, 24, 25]. These interactions are mediated by either the SH3-domain (Abi1 and RN-tre binding), or by the C-terminal “effector region” (Sos1 and F-actin binding), respectively. The protein region that was responsible for the lysosomal localization of Eps8 (amino acids 184-535, target region) lacked these domains, suggesting that Eps8 recruitment does not require a functional SH3 domain and is independent of dynamic F-actin processes. Indeed, inhibition of F-actin polymerisation with cytochalasin D did not affect Eps8 recruitment to lysosomes. It was known, that the putative EGF receptor binding site resides within the target region. However, only a small fraction of Eps8-positive lysosomes also contained EGFR after ligand induced internalization, arguing that the EGFR-binding region does not mediate Eps8 recruitment to lysosomes.

Interestingly, we could identify two KFERQ-like motifs within the target region. These pentapeptide sequences are recognized by the heat shock protein of 70 kDa (Hsc70) and other cochaperones, and initiate chaparone-mediated autophagy (CMA). This protein complex binds to the multisubunit form of the LAMP-2A isoform in the lysosomal membrane. After unfolding, the substrate protein is translocated across the lysosomal membrane, and subjected to degradation [14, 26, 27]. About 30% of cytosolic proteins undergo this specific lysosomal degradation pathway that seems to be restricted to certain tissues, such as liver, kidney, and heart [26]. In the present study we provided evidence that Eps8 binds to isolated lysosomes, translocates into the lysosomal lumen, and that lysosomal membrane binding can be competed by known CMA substrates, suggesting that Eps8 itself is a CMA substrate. The present data further showed that high expression of Eps8 promotes Eps8 recruitment to lysosomes, although we did not investigate whether a high Eps8 expression level alone, or other additional molecular interactions are required for this lysosomal recruitment. However, these results indicate that human cancer cells may utilize CMA for the regulation of important cytosolic proteins. We recently published that human pancreatic cancer cells with high Eps8 expression (and endogenous Eps8 recruitment to lysosomes) were generated from advanced tumor stages, i.e. from pancreatic cancer metastases (Capan-1) or from malignant ascites (AsPC-1) [8]. We do not exactly know whether Eps8 is responsible for the metastatic nature of Capan-1 or AsPC-1 cells, but these cells obviously appear to have an enhanced turnover of the Eps8 molecule.

Although we showed that the “effector region” of Eps8 is not required for lysosomal binding, it is possible that Eps8 under certain circumstances may link actin with lysosomal membranes. Under this hypothetical scenario, CMA can be seen as a way to regulate lysosomal membrane and actin dynamics through changes in levels of resident Eps8. This in turn may affect some key lysosomal functions, such as actin-based facilitation of fusion events of the late endosomal/lysosomal compartment, as previously reported [28]. Indeed, stimulation of late endosomal fusion events through Eps8 may account for the enlargement of lysosome vesicle in cells with elevated endogenous Eps8, and after ectopic Eps8 expression, suggesting that Eps8 may not only be routed to these structures for its degradation, but also promotes the lysosomal targeting of yet to be identified cargos. Consistent with this, Goebeler et al. recently reported that the actin-interacting annexin A8 governs late endosomal organization and function in HeLa cells. Annexin A8 expression resulted in enlarged late endosomes, while its depletion caused delayed degradation of endosomal cargos, such as the EGF receptor [29].

In conclusion, the finding that Eps8 localizes and binds to lysosomes in human cancer cells, and is degraded through CMA provides novel molecular interactions to study. Although it remains unclear how Eps8 and the regulation of CMA are connected in cancer cells, the present data indicate that Eps8 may play a more versatile role in cancer progression than expected. Future experiments have to analyze if Eps8 physiologically regulates CMA, controls fusion of late endosomes, and thus can impair e.g. EGF receptor degradation in cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Confocal time-lapse in vivo microscopy of AsPC-1 cells transfected with full-length Eps8-GFP. Lysosomes were labeled with the LysoTracker Dye (red). Images were taken every 10s over 8 min. Image width represents 52 μm.

Figure S2. Confocal time-lapse in vivo microscopy of HeLa cells transfected with full-length Eps8-GFP. Lysosomes are labeled with the LysoTracker Dye (red). Images were taken every 10s over 8 min. Image width represents 80 μm.

Figure S3. Eps8 localization after inhibition of actin polymerisation. AsPC-1 cells were treated with cytochalasin D at 1 μg/ml (A–C), or mock treated (D–F) for 30 min before fixation and staining with Alexa488-Phalloidin and Eps8 (red). The lysosomal localization of Eps8 remained unchanged after inhibition of actin polymerisation. Image width represents 54 μm.

Figure S4. Eps8 localization after inhibition of lysosomal acidification. Inhibition of lysosomal acidification and protein degradation in AsPC-1 cells was achieved using bafilomycin A1 at 100 nM (or DMSO as control) for 60 min. Cells were then incubated with LysoTracker dye for 60 min, and the cells finally fixed for 20 min. After permeabilizing the cells briefly for 60 s, they were stained for Eps8. (A–C) Eps8 localized to lysosomes, and LysoTracker uptake indicated functional lysosomes in control treated cells. (D–F) Eps8 persisted at lysosomal membranes after lysosomes were functionally inhibitied through bafilomycin A1 (note that there is no uptake of LysoTracker dye). Image widths represent 73 μm.

Figure S5. Tracking of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor internalization in AsPC-1 cells. (A–C) AsPC-1 cells were transfected with full-length Eps-GFP, serum starved for 24 h, stimulated with EGF for 0–60 min, and then fixed and stained for the EGF receptor. Images show EGF receptor localization (red) after 20 min. There was no overlap with Eps8-positive lysosomes. (D–F) AsPC-1 cells were tranfected with full-length Eps-GFP, serum starved for 24 h, and stimulated for 0–60 min with rhodamine-EGF (rhEGF) before fixation and analysis. After 20 min, some rhEGF was observed at the membrane of Eps8-postive vesicles, but there was no complete overlap, advocating that binding to EGF receptors is not responsible for Eps8 recruitment to lysosomes. (G–I) AsPC-1 cells were serum starved, stimulated with rhEGF for 60 min, and stained for the late endosome/lysosome marker Lamp1. Most rhEGF spots did not colocalize with Lamp1-positive vesicles. Image widths represent: (A–C) 54 μm, (D–F) 40 μm, (G, H) 78 μm.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sonja Bauer for her excellent technical assistance. This work was partly supported by the NIH Grant AG021904 (to AMC).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- 1.Fazioli F, Minichiello L, Matoska V, Castagnino P, Miki T, Wong WT, Di Fiore PP. Eps8, a substrate for the epidermal growth factor receptor kinase, enhances EGF-dependent mitogenic signals. Embo J. 1993;12:3799–3808. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matoskova B, Wong WT, Salcini AE, Pelicci PG, Di Fiore PP. Constitutive phosphorylation of eps8 in tumor cell lines: relevance to malignant transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3805–3812. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YJ, Shen MR, Chen YJ, Maa MC, Leu TH. Eps8 decreases chemosensitivity and affects survival of cervical cancer patients. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1376–1385. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffith OL, Melck A, Jones SJ, Wiseman SM. Meta-analysis and meta-review of thyroid cancer gene expression profiling studies identifies important diagnostic biomarkers. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5043–5051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maa MC, Lee JC, Chen YJ, Chen YJ, Lee YC, Wang ST, Huang CC, Chow NH, Leu TH. Eps8 facilitates cellular growth and motility of colon cancer cells by increasing the expression and activity of focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19399–19409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Patel V, Miyazaki H, Gutkind JS, Yeudall WA. Role for EPS8 in squamous carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:165–174. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao J, Weremowicz S, Feng B, Gentleman RC, Marks JR, Gelman R, Brennan C, Polyak K. Combined cDNA array comparative genomic hybridization and serial analysis of gene expression analysis of breast tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4065–4078. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welsch T, Endlich K, Giese T, Buchler MW, Schmidt J. Eps8 is increased in pancreatic cancer and required for dynamic actin-based cell protrusions and intercellular cytoskeletal organization. Cancer Lett. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disanza A, Carlier MF, Stradal TE, Didry D, Frittoli E, Confalonieri S, Croce A, Wehland J, Di Fiore PP, Scita G. Eps8 controls actin-based motility by capping the barbed ends of actin filaments. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1180–1188. doi: 10.1038/ncb1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Disanza A, Mantoani S, Hertzog M, Gerboth S, Frittoli E, Steffen A, Berhoerster K, Kreienkamp HJ, Milanesi F, Di Fiore PP, et al. Regulation of cell shape by Cdc42 is mediated by the synergic actin-bundling activity of the Eps8-IRSp53 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1337–1347. doi: 10.1038/ncb1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanzetti L, Rybin V, Malabarba MG, Christoforidis S, Scita G, Zerial M, Di Fiore PP. The Eps8 protein coordinates EGF receptor signalling through Rac and trafficking through Rab5. Nature. 2000;408:374–377. doi: 10.1038/35042605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palamidessi A, Frittoli E, Garre M, Faretta M, Mione M, Testa I, Diaspro A, Lanzetti L, Scita G, Di Fiore PP. Endocytic trafficking of Rac is required for the spatial restriction of signaling in cell migration. Cell. 2008;134:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Fiore PP, Scita G. Eps8 in the midst of GTPases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:1178–1183. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dice JF. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy. 2007;3:295–299. doi: 10.4161/auto.4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang C, Cuervo AM. Restoration of chaperone-mediated autophagy in aging liver improves cellular maintenance and hepatic function. Nat Med. 2008;14:959–965. doi: 10.1038/nm.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scita G, Tenca P, Areces LB, Tocchetti A, Frittoli E, Giardina G, Ponzanelli I, Sini P, Innocenti M, Di Fiore PP. An effector region in Eps8 is responsible for the activation of the Rac-specific GEF activity of Sos-1 and for the proper localization of the Rac-based actin-polymerizing machine. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:1031–1044. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuervo AM, Dice JF, Knecht E. A population of rat liver lysosomes responsible for the selective uptake and degradation of cytosolic proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5606–5615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D. Impaired degradation of mutant alpha-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science. 2004;305:1292–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.1101738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terlecky SR, Dice JF. Polypeptide import and degradation by isolated lysosomes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23490–23495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Croce A, Cassata G, Disanza A, Gagliani MC, Tacchetti C, Malabarba MG, Carlier MF, Scita G, Baumeister R, Di Fiore PP. A novel actin barbed-end-capping activity in EPS-8 regulates apical morphogenesis in intestinal cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/ncb1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salvador N, Aguado C, Horst M, Knecht E. Import of a cytosolic protein into lysosomes by chaperone-mediated autophagy depends on its folding state. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27447–27456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Futter CE, Pearse A, Hewlett LJ, Hopkins CR. Multivesicular endosomes containing internalized EGF-EGF receptor complexes mature and then fuse directly with lysosomes. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:1011–1023. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.6.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goicoechea S, Arneman D, Disanza A, Garcia-Mata R, Scita G, Otey CA. Palladin binds to Eps8 and enhances the formation of dorsal ruffles and podosomes in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3316–3324. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Provenzano C, Gallo R, Carbone R, Di Fiore PP, Falcone G, Castellani L, Alema S. Eps8, a tyrosine kinase substrate, is recruited to the cell cortex and dynamic F-actin upon cytoskeleton remodeling. Exp Cell Res. 1998;242:186–200. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. Lysosomes, a meeting point of proteins, chaperones, and proteases. J Mol Med. 1998;76:6–12. doi: 10.1007/s001090050185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. Unique properties of lamp2a compared to other lamp2 isoforms. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 24):4441–4450. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.24.4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjeken R, Egeberg M, Habermann A, Kuehnel M, Peyron P, Floetenmeyer M, Walther P, Jahraus A, Defacque H, Kuznetsov SA, et al. Fusion between phagosomes, early and late endosomes: a role for actin in fusion between late, but not early endocytic organelles. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:345–358. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goebeler V, Poeter M, Zeuschner D, Gerke V, Rescher U. Annexin A8 regulates late endosome organization and function. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5267–5278. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Confocal time-lapse in vivo microscopy of AsPC-1 cells transfected with full-length Eps8-GFP. Lysosomes were labeled with the LysoTracker Dye (red). Images were taken every 10s over 8 min. Image width represents 52 μm.

Figure S2. Confocal time-lapse in vivo microscopy of HeLa cells transfected with full-length Eps8-GFP. Lysosomes are labeled with the LysoTracker Dye (red). Images were taken every 10s over 8 min. Image width represents 80 μm.

Figure S3. Eps8 localization after inhibition of actin polymerisation. AsPC-1 cells were treated with cytochalasin D at 1 μg/ml (A–C), or mock treated (D–F) for 30 min before fixation and staining with Alexa488-Phalloidin and Eps8 (red). The lysosomal localization of Eps8 remained unchanged after inhibition of actin polymerisation. Image width represents 54 μm.

Figure S4. Eps8 localization after inhibition of lysosomal acidification. Inhibition of lysosomal acidification and protein degradation in AsPC-1 cells was achieved using bafilomycin A1 at 100 nM (or DMSO as control) for 60 min. Cells were then incubated with LysoTracker dye for 60 min, and the cells finally fixed for 20 min. After permeabilizing the cells briefly for 60 s, they were stained for Eps8. (A–C) Eps8 localized to lysosomes, and LysoTracker uptake indicated functional lysosomes in control treated cells. (D–F) Eps8 persisted at lysosomal membranes after lysosomes were functionally inhibitied through bafilomycin A1 (note that there is no uptake of LysoTracker dye). Image widths represent 73 μm.

Figure S5. Tracking of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor internalization in AsPC-1 cells. (A–C) AsPC-1 cells were transfected with full-length Eps-GFP, serum starved for 24 h, stimulated with EGF for 0–60 min, and then fixed and stained for the EGF receptor. Images show EGF receptor localization (red) after 20 min. There was no overlap with Eps8-positive lysosomes. (D–F) AsPC-1 cells were tranfected with full-length Eps-GFP, serum starved for 24 h, and stimulated for 0–60 min with rhodamine-EGF (rhEGF) before fixation and analysis. After 20 min, some rhEGF was observed at the membrane of Eps8-postive vesicles, but there was no complete overlap, advocating that binding to EGF receptors is not responsible for Eps8 recruitment to lysosomes. (G–I) AsPC-1 cells were serum starved, stimulated with rhEGF for 60 min, and stained for the late endosome/lysosome marker Lamp1. Most rhEGF spots did not colocalize with Lamp1-positive vesicles. Image widths represent: (A–C) 54 μm, (D–F) 40 μm, (G, H) 78 μm.