Abstract

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) remains a common and potentially life-threatening complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT). The 2-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD requiring systemic treatment is ∼30% to 40% by National Institutes of Health criteria. The risk of chronic GVHD is higher and the duration of treatment is longer after HCT with mobilized blood cells than with marrow cells. Clinical manifestations can impair activities of daily living and often linger for years. Hematology and oncology specialists who refer patients to centers for HCT are often subsequently involved in the management of chronic GVHD when patients return to their care after HCT. Treatment of these patients can be optimized under shared care arrangements that enable referring physicians to manage long-term administration of immunosuppressive medications and supportive care with guidance from transplant center experts. Keys to successful collaborative management include early recognition in making the diagnosis of chronic GVHD, comprehensive evaluation at the onset and periodically during the course of the disease, prompt institution of systemic and topical treatment, appropriate monitoring of the response, calibration of treatment intensity over time in order to avoid overtreatment or undertreatment, and the use of supportive care to prevent complications and disability.

Introduction

The prevalence and severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) have increased during the past 2 decades in association with the increasing use of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) for treatment of older age patients, the widespread use of mobilized blood cells instead of marrow for grafting, and improvements in survival during the first several months after allogeneic HCT.1-6

Pathophysiological understanding of chronic GVHD is emerging,7,8 but the long-standing reliance on prednisone described as the mainstay of treatment in Vogelsang’s “How I Treat” review in 2001 has persisted to the present.9 The 2005 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Conference developed a framework for characterizing the pleomorphic manifestations of chronic GVHD. The consensus project defined minimal criteria for the clinical diagnosis, emphasized differences in the clinical manifestations of chronic and acute GVHD, established criteria for scoring the severity of clinical manifestations in affected organs, and proposed new categories for describing overall disease severity and indications for treatment.10 The consensus project also proposed measures for monitoring disease progression and response to therapy and provided other information for purposes of clinical trials.11-13 In 2014, the NIH Conference was reconvened, and revisions are under consideration to update the recommendations based on available evidence and insights from clinical application of the original recommendations.14-33

Chronic GVHD has a wide range of pleomorphic manifestations, and many complications can emerge from both the disease and its treatment. A dedicated multidisciplinary team approach with relevant expertise is necessary in order to provide the best care for patients with a chronic illness that can have devastating effects on quality of life. Our approach to treatment emphasizes the importance of early recognition in the management of chronic GVHD, with respect to making the initial diagnosis, monitoring the response to initial treatment, and preventing complications and disability. Nuances applicable only to children are not addressed in this review.

Case summary

A 45-year-old man received growth factor–mobilized blood cells from an HLA-matched unrelated male donor after conditioning with 12 Gy total body irradiation and cyclophosphamide for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia with persistent disease. He received methotrexate and tacrolimus for immunosuppression after HCT. He developed acute GVHD of the skin and gut, which resolved after treatment with steroid cream and oral beclomethasone and budesonide. Because malignant cells persisted after HCT, treatment was administered with azacytidine, and immunosuppression with tacrolimus was withdrawn by day 100, 3 months earlier than originally planned.

Malignant cells disappeared, but 7 months after HCT and 2 months after the third cycle of azacytidine, he was diagnosed with severe chronic GVHD (NIH global score). Affected sites included the skin (erythematous rash involving >50% body surface area [BSA]), mouth (ulcers and lichenoid features), fasciae (wrist tightness and leg edema), liver (alanine aminotransferase twice the normal upper limit with normal total serum bilirubin concentration), and eosinophilia (1800 per μL). Forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) was 79% of predicted, and the ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FVC) was 78% of predicted, representing an absolute 8% decline from the baseline before HCT.

Treatment was started with prednisone at 1 mg/kg per day, and antibiotic prophylaxis was administered to prevent Pneumocystis pneumonia and infection with encapsulated bacteria. Antiviral prophylaxis was continued with acyclovir. Daily intake of vitamin D 1000 IU and calcium 1500 mg was recommended. After 2 weeks, improvement was noted in wrist discomfort, leg edema, and the extent of rash, with resolution of eosinophilia and liver function abnormalities. The dose of prednisone was tapered to reach 80 mg every other day, with continued clinical monitoring and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) at monthly intervals.

During the next 3 months, PFTs improved, but other manifestations showed progressive worsening, with cutaneous sclerosis involving ∼28% of the BSA with a Rodnan modified total score34 of 8, oral ulceration, and decreased wrist mobility. The patient enrolled in a randomized clinical trial comparing imatinib vs rituximab for steroid-refractory sclerotic GVHD. He was randomized to treatment with imatinib (200 mg daily) while continuing treatment with prednisone 80 mg every other day. Dexamethasone oral rinses and clobetasol ointment were used to control oral ulceration.13

The extent and severity of sclerosis remained stable for 3 months. Sclerosis then began to progress, involving ∼50% of BSA with a Rodnan score of 28 after 6 months of treatment with imatinib. The patient met the criteria for crossover according to the study design, and he was treated with 2 cycles of rituximab, 375 mg/m2 per week for 4 weeks per cycle. Due to hypertension and hyperglycemia, the dose of prednisone was gradually tapered to 40 mg every other day within 6 months. The patient subsequently reported improved flexibility, and after 7 months, sclerosis remained stable with a Rodnan score of 26.

Eleven months after the last dose of rituximab, fasciitis progressed with further decrease in range of motion while continuing treatment with prednisone at 40 mg every other day. Extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP)35 (reviewed in Inamoto and Flowers36), low-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2),37 and sirolimus were considered as possible further treatment. The patient opted for daily low-dose IL-2, but he had significant local reactions, low-grade fever, and no appreciable improvement in GVHD. Three months after treatment with IL-2 was discontinued, he developed a new erythematous maculopapular rash affecting 50% of BSA. The dose of prednisone was increased to 40 mg per day, and sirolimus was added. The rash subsequently improved, but sclerosis and fasciitis continued to worsen, prompting treatment with ECP for the past 3 months. Efficacy cannot yet be assessed because improvement is often not observed until treatment with ECP has been continued for at least 6 months.35,38

Pathophysiology

Recent laboratory studies have yielded some insights into the pathophysiology of chronic GVHD, and candidate biomarkers that could be used for diagnosis or monitoring have been identified.7,8 The disease likely represents a syndrome in which the respective contributions of inflammation, innate and adaptive cell-mediated immunity, humoral immunity, abnormal immune regulation, and fibrosis vary considerably from 1 patient to the next. The risk of chronic GVHD can be substantially decreased by administration of rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin or alemtuzumab in the conditioning regimen before HCT,39-43 or by administration of high-dose cyclophosphamide on days 3 and 4 after HCT.44,45 These results demonstrate that the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to development of chronic GVHD are set in motion at the time of HCT, even though the manifestations of the disease typically do not become apparent until several months later.

Animal models that replicate many features of the disease have been established, but mechanisms linking inflammation with abnormal immune regulation and mechanisms linking immune-mediated injury with fibrosis have not been well defined. In the absence of a definitive understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms or clear explanation accounting for the considerable variability of disease manifestations among patients, efforts to develop new treatment have relied on empirical testing of agents approved for other indications where inflammation, abnormal immune regulation, or fibrosis have been implicated as pathogenic mechanisms.

Diagnosis and evaluation

Manifestations of chronic GVHD can resemble autoimmune or other immune-mediated disorders such as scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, primary biliary cirrhosis, bronchiolitis obliterans, immune cytopenias, and chronic immunodeficiency. Manifestations typically appear within the first year after HCT, most often when doses of immunosuppressive medications are weaned. The disease can begin as early as 2 months and as late as 7 years after HCT, although onset at >1 year from HCT occurs in <10% of cases.46 Chronic GVHD should be suspected at the onset of any perturbation in laboratory tests, symptoms, or signs, especially during the first year after HCT. Conversely, not every problem after allogeneic HCT represents chronic GVHD. Other conditions such as eczema, iron overload, hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, infections, or drug effect can be misdiagnosed as chronic GVHD.47

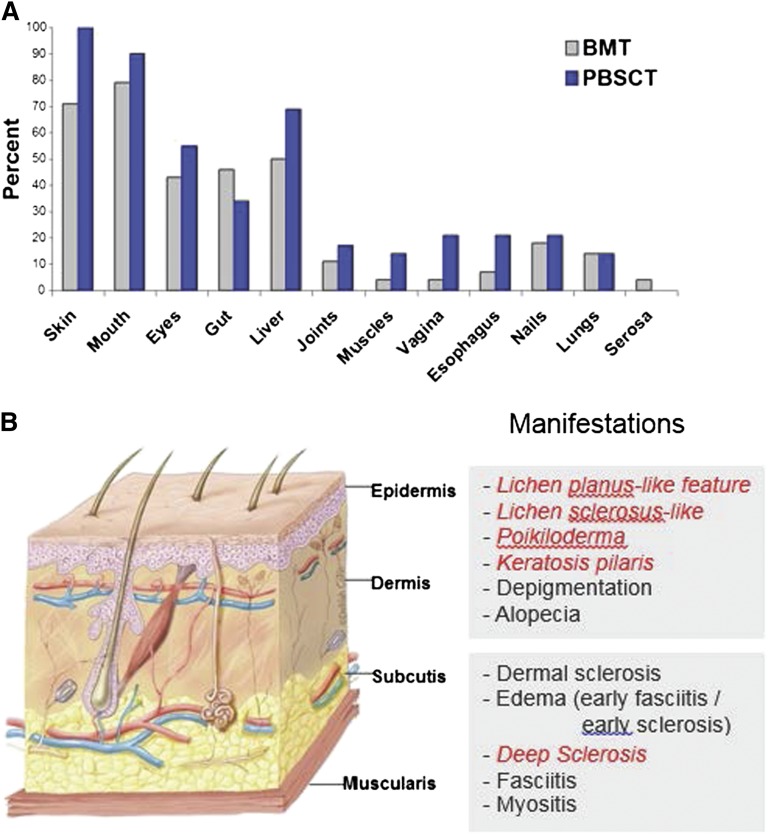

Chronic GVHD generally involves several organs or sites, although manifestations are sometimes restricted to a single organ or site. The disease is characterized by features that differ from the typical dermatitis, enteritis, and cholestatic liver manifestations of acute GVHD (Table 1).10 Patients frequently have erythematous rash, enteritis, or hepatic involvement characterized by transaminase elevation or hyperbilirubinemia at initial presentation and intermittently afterward during the course of the disease. The term “overlap syndrome” has been used to indicate that manifestations typical of acute GVHD are present in a patient with chronic GVHD. These inflammatory manifestations are often transient, disappearing when the intensity of immunosuppression is increased and reappearing when the intensity of immunosuppression is tapered. According to NIH criteria, the diagnosis of chronic GVHD requires at least 1 diagnostic sign or at least 1 distinctive sign confirmed by biopsy, other tests, or by radiography in the same or another organ, and exclusion of other diagnoses (Table 1).10 Manifestations of chronic GVHD have a wide range of severity and impact on quality of life after HCT. Certain manifestations are particularly difficult to manage and require prolonged treatment. These include fasciitis or cutaneous sclerosis, severe ocular sicca, and BOS, occurring in ∼20%,48 12%,3 and about 10%3 of patients, respectively. The most common organs and sites affected by chronic GVHD include the skin, mouth, eyes, gastrointestinal tract, and liver (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Clinical manifestations of chronic GVHD

| Organ or site | Diagnostic (sufficient for diagnosis) | Distinctive (insufficient alone for diagnosis) | Other | Features seen in both acute and chronic GVHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Poikiloderma | Depigmentation | Erythema | |

| Lichen planus-like | Papulosquamous | Maculopapular | ||

| Sclerosis | Pruritus | |||

| Morphea-like | ||||

| Lichen sclerosis-like | ||||

| Nails | Dystrophy | |||

| Onycholysis | ||||

| Nail loss | ||||

| Pterygium unguis | ||||

| Scalp and body hair | Alopecia (scarring or nonscarring) | |||

| Scaling | ||||

| Mouth | Lichen planus-like | Xerostomia | Gingivitis | |

| Mucoceles | Mucositis | |||

| Mucosal atrophy | Erythema | |||

| Pseudomembranes or ulcers* | Pain | |||

| Eyes | New dry, gritty, or painful eyes (sicca) | |||

| Keratoconjunctivitis sicca | ||||

| Punctate keratopathy | ||||

| Genitalia | Lichen planus-like | Erosions* | ||

| Lichen sclerosis-like | Fissures* | |||

| Female: | Ulcers* | |||

| Vagina scarring or stenosis | ||||

| Clitoral or labial agglutination | ||||

| Male: | ||||

| Phimosis | ||||

| Urethral scarring or stenosis | ||||

| GI tract | Esophageal web | Diarrhea | ||

| Esophageal stricture | Anorexia | |||

| Nausea or emesis | ||||

| Failure to thrive | ||||

| Weight loss | ||||

| Liver | Total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase or ALT >2× ULN | |||

| Lung | Bronchiolitis obliterans diagnosed by biopsy BOS§ | Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia† | ||

| Restrictive lung disease† | ||||

| Muscles, fascia, joints | Fasciitis | Myositis | ||

| Joint stiffness or contractures due to sclerosis | Polymyositis | |||

| Hematopoietic and Immune | Thrombocytopenia | |||

| Eosinophilia | ||||

| Hypo- or hypergammaglobulinemia | ||||

| Autoantibodies | ||||

| Raynaud phenomenon | ||||

| Others | Effusions‡ | |||

| Nephrotic syndrome | ||||

| Myasthenia gravis | ||||

| Peripheral neuropathy |

Modified from Stem Cell Trialists’ Collaborative Group.6

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal; ULN, upper limit of normal.

In all cases infection, drug effect, malignancy, endocrine causes must be excluded as applicable.

These pulmonary manifestations are under investigation or unclassified.

Pericardium, pleural, or ascites.

BOS can be diagnostic for lung chronic GVHD only, if distinctive feature present in another site.

Figure 1.

The frequency of involvement by chronic GVHD varies across organs and sites and is higher after HCT with mobilized blood cells as compared with marrow. (A) The most frequently involved organs and sites are the skin, mouth, eyes, gastrointestinal tract, and liver.3 (B) Chronic GVHD can affect all layers of the skin. Photographs of each manifestation in italic may be found in the supplemental Data, available on the Blood Web site. Artwork by Delilah Cohn, MFA, CMI, used with permission.

Systematic and comprehensive assessment of organs and sites possibly affected by chronic GVHD is essential for early diagnosis, early recognition of manifestations associated with high morbidity and disability, and assessment of disease progression and response during treatment (Tables 2-3). Once the clinical diagnosis of chronic GVHD is made, the extent and severity of each affected organ must be ascertained using the NIH chronic GVHD diagnosis and scoring consensus criteria.10 Recommended methods for conducting a chronic GVHD-focused evaluation have been published49 (they can be viewed at http://www.fhcrc.org/en/labs/clinical/projects/gvhd.html).50 Comprehensive evaluations should be done at the time of initial diagnosis, at 3- to 6-month intervals thereafter, and at any time when a major change in therapy is made. Evaluations should continue until at least 12 months after systemic treatment has ended.

Table 2.

Evaluation and frequency of monitoring according symptoms or affected organs

| Evaluation | Frequency of evaluation/monitoring | |

|---|---|---|

| Manifestations present | Manifestations absent | |

| Review of systems (see Table 3 for chronic GVHD-specific questions) | Every clinic visit | Every clinic visit |

| Physical examination | ||

| Complete skin examination (look, touch, pinch) | Every clinic visit | Every clinic visit |

| Oral examination | Every clinic visit | Every clinic visit |

| Range of motion assessment | Every clinic visit | Every clinic visit |

| Performance score | Every clinic visit | Every clinic visit |

| Nurse assessment | ||

| Weight | Every clinic visit | Every clinic visit |

| Height/adults | Yearly | Yearly |

| Height/children | Every 3-12 mo | Every 3-12 mo |

| Medical photographs | ∼100 d after HCT (baseline), at initial diagnosis of chronic GVHD, every 6 mo if skin or joints are involved and during treatment until at least 1 y after discontinuation of treatment | ∼100 d after HCT (baseline) |

| Other evaluations | ||

| PFTs | ∼100 d after HCT (baseline); see also Table 4 | ∼100 d after HCT and every 3 mo for the first year, then yearly if previous PFTs were abnormal or if continuing systemic treatment; reassess at onset of new symptoms |

| Nutritional assessment | As clinically indicated and yearly if receiving corticosteroids | As clinically indicated |

| Physiotherapy with assessment of range of motion | Every 3 mo if sclerotic features affecting range of motion until resolution | As clinically indicated |

| Dental or oral medicine consultation with comprehensive soft and hard tissue examination, culture, biopsy, or photographs of lesions, as clinically indicated | Every 3-6 mo or more often as indicated | Yearly |

| Ophthalmology consultation with Schirmer test, slit-lamp examination, and intraocular pressure | At initial diagnosis and every 3-6 mo or more often as indicated | ∼100 d after HCT (baseline) and yearly |

| Gynecology examination for vulvar or vaginal involvement | Every 6 mo or more often as indicated | Yearly |

| Dermatology consultation with assessment of extent and type of skin involvement, biopsy, or photographs | As clinically indicated | |

| Neuropsychological testing | As clinically indicated | |

| Bone mineral assessment (DEXA) scan | Yearly during corticosteroid treatment or if prior test was abnormal | ∼100 d after HCT if continuing corticosteroid treatment (baseline) |

Modified from Flowers and Vogelsang.69

Table 3.

Chronic GVHD review of systems

| No. | System/others | Inquire/description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Skin | Skin feels tight or hard, increased dryness, pruritus, or looks different (ie, new rash, papules, discoloration, shining scar-like, scaly)? |

| 2 | Sweat glands | Inability to sweat or to keep body warm? |

| 3 | Skin appendages | Loss of hair (scalp or body including bows or lashes), or nail changes (ridges or brittle, loss)? |

| 4 | Fasciae/joints | Stiffness or pain in the wrists, fingers, or other joints? |

| 5 | Eyes | Eye dryness, sensitivity to wind or dry environments (air conditioning), pain? |

| 6 | Mouth | Oral dryness, taste alterations, sensitivities (spicy/carbonate drinks, toothpaste), ulcers/sores, pain? |

| 7 | Esophagus | Foods or pills gets stuck upon swallowing? |

| 8 | Lungs | Cough, dyspnea (on exertion or rest) or wheezes? |

| 9 | Genital tract | Vaginal dryness, pain, dyspareunia (female); pain or dysuria due to stenosis of urethra (male)? |

| 10 | Weight loss | Unexplained weight loss or inability to gain weight (pancreatic insufficiency or hypercatabolism)? |

Close serial monitoring of all organ systems is essential in order to ensure early detection, recognition, and intervention directed toward reversing or preventing progression of chronic GVHD manifestations and treatment-associated toxicities. In particular, periodic pulmonary function tests are essential for early detection of lung involvement manifested as BOS because this complication has an insidious onset, and patients may remain asymptomatic until considerable lung function has been lost. We recommend complete pulmonary function testing in all patients before HCT and at ∼3 months after HCT as a baseline for future comparisons (Table 4).10 Follow-up testing should be done at the onset of chronic GVHD and at 3- to 6-month intervals for the first year or more often if testing shows any significant new airflow obstruction or decline in the percent of predicted FEV1. Patient and physician-directed tools to support chronic GVHD monitoring can be found online (http://www.fhcrc.org/en/treatment/long-term-follow-up/information-for-physicians.html).

Table 4.

General guidelines for monitoring and management of new airflow obstruction

| Guidelines |

|---|

| A. Significant new airflow obstruction with a % predicted FEV1 ≥70% |

| 1. Initiate inhaled corticosteroid therapy |

| • Fluticasone (Flovent) 440 mcg BID, or |

| • Advair 500/50 mcg BID (if symptoms of airway obstruction are present) |

| • Treatment should continue until either % FEV1 becomes <70% (see below), or until GVHD resolves (ie, resolution of all reversible manifestations of GVHD without exacerbation after at least 6 mo after discontinuation of all systemic immunosuppressive treatment) |

| 2. Other immunosuppressive treatment as indicated to control GVHD in other organs |

| • Treatment should continue until either % FEV1 becomes <70% (see below), or until GVHD resolves (ie, resolution of all reversible manifestation of GVHD without exacerbation after at least 12 mo after discontinuation of all systemic treatments) |

| 3. Monitor PFTs or spirometry monthly for at least 3 mo |

| • If % FEV1 stabilizes, PFTs or spirometry every 3 mo for 1 y, then if stable continue at 6-mo intervals for 1 y and at 6-12 mo intervals thereafter |

| • If % FEV1 continues to decrease, go to B below |

| B. Significant airflow obstruction with a % FEV1 <70% with/without significant air-trapping by high resolution chest CT |

| 1. Consider bronchoscopy to rule out an undetected infectious etiology for airflow obstruction, even if no infiltrate is apparent |

| 2. After infection has been ruled out, evaluate the patient eligibility for clinical trial for treatment of BOS and initiate (or increase) prednisone dose to 1 mg/kg/d |

| • Start standard chronic GVHD taper at 2 wk (Table 5) |

| • Consider continuing inhaled corticosteroids throughout prednisone therapy |

| 3. If % FEV1 decreases further to <70% during treatment, discuss changes of immunosuppressive treatment with transplant physician |

| 4. CMV monitoring in blood per standard practice |

| 5. Monitor PFTs or spirometry monthly for at least 3 mo |

| • If % FEV1 stabilizes, continue PFTs or spirometry every 3 mo for 1 y |

| • If % FEV1 continues to decrease, go to C below |

| C. Corticosteroid-resistant airflow obstruction defined as progressive decline of FEV1 by ≥10% despite treatment with 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone (or similar corticosteroids) |

| 1. May consider increasing the dose of prednisone to 2 mg/kg/d for a maximum of 2 wk, followed by a taper to reach a dose of 1 mg/kg/d by 2-4 wk |

| 2. Another treatment must be considered and discussed with the transplant team |

| 3. Monitor CMV in blood per standard practice |

| 4. Monitor PFTs monthly for at least 3 mo |

| • If % FEV1 stabilizes, monitor PFTs every 3 mo for 1 y |

| D. Additional considerations |

| 1. Consider changing prophylaxis for encapsulated bacterial infection to azithromycin 250 mg on Mondays-Wednesdays-Fridays |

| • Assure patient is receiving adequate prophylaxis for Pneumocystis, varicella virus, and herpes simplex virus infections |

| • Fungal prophylaxis per standard practice |

| 2. Monitor CMV in blood per standard practice |

| 3. May continue inhaled corticosteroids throughout prednisone therapy |

| 4. Discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroid treatment can be considered 12 mo after treatment with prednisone has been discontinued |

Before considering treatment, all potential infectious etiologies of airflow obstruction must be investigated and treated if present. Investigations that should be considered (directed by clinical symptoms), include sinus CT scan, nasal washes, sinus aspiration, high-resolution chest CT scan, sputum culture, bronchoalveolar lavage, and lung biopsy.

BID, twice daily; CT, computed tomography scan.

Treatment

Treatment of chronic GVHD is intended to produce a sustained benefit by reducing symptom burden, controlling objective manifestations of disease activity, and preventing damage and disability, without causing disproportionate toxicity or harms related to the treatments themselves. The long-term goal of GVHD treatment is the development of immunologic tolerance, indicated by successful withdrawal of all immunosuppressive treatment without recurrence or clinically significant exacerbation of disease manifestations. The current therapeutic approach functions primarily to prevent immune-mediated damage, while awaiting the development of tolerance. Evidence to suggest that current treatments accelerate the development of immunologic tolerance is lacking. Optimal treatment of chronic GVHD requires a multidisciplinary team approach that includes transplantation specialists, a primary health care provider, organ-specific consultants, nurses, and ancillary services such as social services, vocational specialists, patient and family support groups, and systems.

Systemic therapy for at least 1 year is generally indicated for patients who meet criteria for moderate-to-severe disease according to the NIH consensus criteria: involvement of 3 or more organs, moderate or severe organ involvement in any organ, or any lung involvement.10,51 Systemic treatment is also generally indicated for patients with less severe disease if high-risk features such as thrombocytopenia, hyperbilirubinemia, or onset during corticosteroid treatment are present.2,10,52-54 Symptomatic mild chronic GVHD is often treated with topical therapies alone.13,52 Topical agents may also be used as adjuncts to systemic therapy to improve and accelerate local response. Comprehensive reviews of topical therapies have been published previously.2,13,52 Considerations affecting the choice of treatment include the affected organs or sites, the severity of disease manifestations, the presence of health problems that might be exacerbated by the treatment, possible drug interactions, the intensity of the monitoring needed, and factors that affect access to the treatment such as travel, distance, and cost.

Primary systemic treatment

Management of chronic GVHD has relied on corticosteroids as the mainstay of treatment of >3 decades. Systemic treatment typically begins with prednisone at 0.5 to 1 mg/kg per day, followed by a taper to reach an alternate-day regimen, with or without cyclosporine or tacrolimus. The efficacy of alternate-day vs daily administration of corticosteroids has been reported in pediatric renal transplantation but has not been tested in HCT.55 Prolonged systemic corticosteroid treatment causes significant toxicity, including weight gain, bone loss, myopathy, diabetes, hypertension, mood swings, cataract formation, and increased risk of infection. Many of these toxicities can be mitigated by alternate-day administration of corticosteroids. Alternate-day administration also has an important role in facilitating adrenal recovery long before the end of treatment. In a recent prospective study, the average dose of prednisone was tapered to 0.20 to 0.25 mg/kg per day or 0.4 to 0.5 mg/kg every other day within 3 months after starting treatment.56 Medications used for treatment of chronic GVHD should be withdrawn gradually one at a time after the disease has resolved. As a general principle, withdrawal of systemic treatment should begin with the medication that is most likely to cause long-term toxicity. Withdrawal of prednisone should generally precede withdrawal of a calcineurin inhibitor, unless continued treatment with the calcineurin inhibitor threatens to cause intolerable or irreversible toxicity.

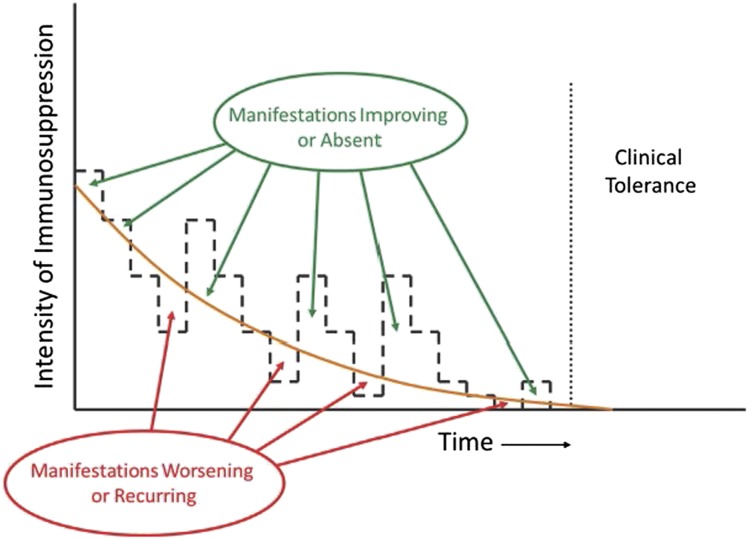

Strategies for tapering the dose of prednisone vary considerably, but as a general principle, efforts should be made to use the minimum dose that is sufficient to control GVHD manifestations (Figure 2). In practice, this means that prednisone doses should be decreased progressively in patients who have had a complete response or a very-good-partial response, and tapering should continue until manifestations begin to recur or show evidence of exacerbation. A prototypic taper schedule (Table 5) is designed to approximate a 20% to 30% dose reduction every 2 weeks, with smaller absolute decrements toward the end of the taper schedule. Toxicity associated with the administration of prednisone may require dose adjustments.

Figure 2.

Appropriate management of chronic GVHD requires continuous recalibration of immunosuppressive treatment in order to avoid overtreatment or undertreatment. The intensity of treatment required to control the disease decreases across time. Manifestations of chronic GVHD improve or are absent when the intensity of treatment is above the threshold shown as the orange curve, and they worsen or recur when the intensity of treatment is below the threshold. The slope of the threshold varies among patients and can be determined only by serial attempts to decrease the intensity of treatment. Clinical tolerance is defined by the ability to withdraw all systemic treatment without recurrence of chronic GVHD.

Table 5.

Prednisone taper schedule

| Week | Dose, mg/kg body weight |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 |

| 2 | 1.0/0.5* (to begin within 2 wk after objective improvement) |

| 4 | 1.0/0.25* |

| 6 | 1.0 qod (continued until resolution of all clinical manifestations) |

| 8 | 0.70 qod (to begin after resolution of all clinical manifestations) |

| 10 | 0.55 qod |

| 12 | 0.45 qod |

| 14 | 0.35 qod |

| 16 | 0.25 qod |

| 18 | 0.20 qod |

| 20 | 0.15 qod |

| 22 | 0.10 qod |

qod, every other day.

Alternate-day administration.

A physician or advanced practitioner should examine the patient before each reduction of the prednisone dose. If exacerbation or recurrence of chronic GVHD is evident at any step of the taper, the dose of prednisone should be increased promptly by 2 levels, with daily administration for 2 to 4 weeks, followed by resumption of alternate-day administration. Treatment should then be continued for at least 3 months before attempting to resume the taper. Cycles of attempted tapering and dose escalation should be repeated as needed until the dose reaches 0.10 mg/kg per day, which equates to adrenal replacement therapy. Administration of prednisone may be discontinued after a minimum of at least 4 weeks of treatment at a dose of 0.10 mg/kg every other day. Some patients have recurrent symptoms with doses at or below 0.10 mg/kg every other day, and in this situation, treatment with very low prednisone doses may be required for a year or more.

Combination therapy with other immunosuppressive agents is often considered in hopes of minimizing toxicity caused by prolonged corticosteroid treatment.54 Randomized trials, however, showed no benefit from adding azathioprine,57 thalidomide,58 mycophenolate mofetil,56 or hydroxychloroquine59 to initial treatment of chronic GVHD. A trial comparing cyclosporine plus prednisone vs prednisone alone showed no statistically significant differences in survival or the duration of treatment.60 The incidence of avascular necrosis was lower in the cyclosporine plus prednisone arm, suggesting that cyclosporine could have had a steroid-sparing effect, but steroid doses across time were not measured in this study. Results are pending from a recent randomized, multicenter phase 2 to 3 clinical trial comparing prednisone and sirolimus with or without a calcineurin inhibitor for initial treatment of chronic GVHD. Premature closure of this trial at the end of phase 2 suggests that the expected benefit of omitting the calcineurin inhibitor was not observed. Wherever possible, clinical trials should be considered as the first option for initial systemic treatment of chronic GVHD.

Secondary systemic treatment

Approximately 50% to 60% of patients with chronic GVHD require secondary treatment within 2 years after initial systemic treatment.61,62 Indications for secondary treatment include worsening manifestations of chronic GVHD in a previously affected organ, development of signs and symptoms of chronic GVHD in a previously unaffected organ, absence of improvement after 1 month of standard primary treatment, inability to decrease prednisone below 1 mg/kg per day within 2 months, or significant treatment-related toxicity. Numerous clinical trials have been carried out to evaluate approaches for secondary treatment of chronic GVHD. Reports from retrospective and prospective studies often indicate high response rates, but results are difficult to interpret because of deficiencies in study design.54

No consensus has been reached regarding the optimal choice of agents for secondary treatment of chronic GVHD, and the published literature provides little useful guidance. Therefore, clinical management requires an empirical approach, as illustrated in “Case summary.” Treatment choices are based on physician experience, ease of use, need for monitoring, risk of toxicity, and potential exacerbation of preexisting comorbidity.63,64 Options for secondary treatment have been recently reviewed and are summarized in Table 6.36

Table 6.

Agents used for secondary treatment of chronic GVHD*

| Treatment | % Overall response* | Survival |

|---|---|---|

| ECP | 65-70 | 70%-78% at 1 y |

| Rituximab | 66-86 | 72% at 1 y |

| Imatinib | 22-79 | 75%-84% at 1.5 y |

| Pentostatin | 53-56 | 34%-60% at 1-3 y |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | 50-74 | 78% at 2 y |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 26-64 | 67%-96% at 1 y |

| mTOR inhibitor | 76 | 72% at 3 y |

| Interleukin-2 | 52 | Not reported |

| Other therapies summarized in other reviews** | ||

| Calcineurin inhibitor | ||

| High-dose methylprednisolone | ||

| Methotrexate | ||

| Thalidomide | ||

| Hydroxychloroquine | ||

| Clofazimine | ||

| Thoracoabdominal irradiation | ||

| Alefacept | ||

| Infliximab | ||

| Etanercept70 | ||

Ancillary and supportive care

Ancillary and supportive care therapies are commonly used in addition to systemic treatment of GVHD, although in some cases, their use may circumvent the need for systemic treatment or allow doses of systemic agents to be reduced. A detailed list of site-specific therapies has been reported elsewhere.2,13 Specific dispensary information for topical therapies is available online (http://asbmt.affiniscape.com/associations/11741/files/DispensaryGuidelines.pdf).

Symptoms caused by ocular sicca can be relieved by the frequent application of artificial lubricant tears or by plugging or ligation of the tear ducts. Symptoms can be relieved by using specialized moisture-chamber eyewear available from several vendors. Permanent punctal ligation is usually necessary in more severe cases of ocular sicca. Many patients with severe sicca keratitis have reported significant relief of symptoms with prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem (PROSE), which refers to a gas-permeable scleral lens.65 Involvement of an ophthalmologist with expertise in the management of dry eye and corneal and conjunctival disease is strongly recommended for patients with ocular manifestations of chronic GVHD.

Oral cavity erythema, ulceration, and gingivitis are often treated with topical steroid rinses or ointments. Vaginal GVHD may respond to topical steroids and dilator therapy, but management should also address any coexisting estrogen deficiency or coexisting yeast or bacterial infection. Sialogogue therapy (to increase the flow rate of saliva) with agents such as cevimeline or pilocarpine may improve symptoms of oral,66 ocular, and vaginal dryness.

Consistent weight-bearing exercise for 30 minutes daily at least 5 days per week and daily stretching are particularly important for preserving bone health, muscle strength, and mobility. Physical therapy to maintain strength and joint mobility can prevent the development of disability during immunosuppressive treatment of chronic GVHD. Deep tissue massage is a helpful adjunct to preserve or improve range of motion in patients with fasciitis or scleroderma.

Close attention must be paid to complications of glucocorticoid treatment through management of hyperglycemia, hypertension, and bone loss. A balanced, healthy diet low in sodium and free sugars and high in calcium with adequate fluid intake is essential. Calcium (1500 mg per day) and vitamin D (1000 IU per day) intake between food and supplements is recommended to retard the development of osteoporosis during glucocorticoid treatment. Clinical trials have not yet been carried out to determine whether bisphosphonates are effective for prevention of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, but some experts recommend the use of these agents for patients with osteopenia.

Both the disease and its treatment with immunosuppressive agents increase the risk of infection in patients with chronic GVHD.2,51 Antibiotic prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia and encapsulated bacterial infections should be given until 6 months after discontinuation of all systemic treatment. IV administration of γ globulin may help prevent infection in patients who have serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentrations <400 mg/dL or IgG2 or IgG4 subclass deficiencies. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection poses risks of CMV disease in patients with a history of viral reactivation and in those with low CD4 counts or cord blood donors. All patients with chronic GVHD who are at risk of CMV infection should have regular blood tests for surveillance of viral reactivation. Preemptive antiviral therapy should be instituted whenever surveillance tests show viral reactivation, before the onset of overt CMV disease. CMV-seronegative recipients with CMV-seronegative donors should receive screened or filtered leukocyte-depleted blood products. In addition, long-term administration of valacyclovir or acyclovir is recommended to prevent reactivation of varicella-zoster virus in patients previously infected with this virus.

Prognosis and outcomes

Duration of treatment

Approximately 50% of patients are cured within 7 years after starting systemic treatment, as indicated by resolution of disease manifestations and permanent withdrawal of systemic treatment. Approximately 10% require continued systemic treatment of an indefinite period beyond 7 years, and the remaining 40% have recurrent malignancy or die within 7 years during treatment of chronic GVHD.30

Growth factor–mobilized apheresis products have replaced marrow as the most frequent source of cells for allogeneic HCT with both related and unrelated donors. The use of mobilized blood cells has been associated with 3 detrimental outcomes with respect to chronic GVHD: a higher incidence, a higher risk of fasciitis and development of fibrotic manifestations affecting the skin and joints, and a longer time to resolution of the disease, development of immunologic tolerance, and withdrawal of systemic treatment.48 The median duration of systemic treatment of chronic GVHD is ∼2 years in patients who had HCT with marrow cells and ∼3.5 years in those who had HCT with mobilized blood cells.

Graft-versus-leukemia associated with chronic GVHD

Chronic GVHD is associated with a reduced risk of recurrent malignancy after hematopoietic cell transplantation, raising the question of whether the intensity of immunosuppression should be attenuated when patients at high risk of recurrent malignancy develop chronic GVHD. This question has not been addressed directly in clinical trials, but several observations are pertinent. First, chronic GVHD increases the risk of nonrelapse mortality, thereby offsetting any benefit gained through the effects on malignant cells in the recipient. The tradeoff between risks of nonrelapse mortality and recurrent malignancy is balanced, such that mortality rates are not affected by the presence or absence of chronic GVHD.67,68 Second, a single-institution study showed that withdrawal of immunosuppression decreased the subsequent risk of recurrent malignancy in patients without prior GVHD but not in those with prior GVHD.67

These results suggest that attenuation of immunosuppression in patients with active manifestations of chronic GVHD might likewise not decrease the risk of recurrent malignancy. Nonetheless, unnecessary immunosuppressive treatment could increase the risk of recurrent malignancy, as suggested by trends in a prospective study evaluating the use of mycophenolate mofetil added to first-line treatment of chronic GVHD.56 Therefore, the intensity of treatment should be calibrated periodically by lowering the dose of immunosuppressive medications to levels that allow disease manifestations to begin emerging before increasing the dose, as described in Figure 2.

Future perspectives

Participation in a clinical trial represents the first option to consider for eligible patients with chronic GVHD. Novel strategies directed toward depleting or modulating B cells, expanding T or B regulatory cells, and targeting the processes implicated in fibrosis are under active investigation and could lead to future advances in treatment of chronic GVHD. Progress toward decreasing the impact of chronic GVHD after HCT will be made not only through improved treatment but also through development of prevention strategies that do not impair the immunological activity of donor cells against malignant cells in the recipient. In the absence of specific interventions to decrease the risk of chronic GVHD, marrow should be preferred over mobilized blood as a source of stem cells for HCT with myeloablative conditioning regimens.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Thompson for assistance with preparing the manuscript and Kevin Bray for assistance with hyperlinks.

This work was supported in part by grant CA18029 from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Contribution: M.E.D.F. and P.J.M. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mary E. D. Flowers, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave N, D5-290, PO Box 19024, Seattle, WA 98109-1024; e-mail: mflowers@fredhutch.org.

References

- 1.Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. CIBMTR 2014. http://www.cibmtr.org. Accessed August 5, 2014.

- 2.Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9(4):215–233. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flowers ME, Parker PM, Johnston LJ, et al. Comparison of chronic graft-versus-host disease after transplantation of peripheral blood stem cells versus bone marrow in allogeneic recipients: long-term follow-up of a randomized trial. Blood. 2002;100(2):415–419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1487–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, et al. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2091–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stem Cell Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Allogeneic peripheral blood stem-cell compared with bone marrow transplantation in the management of hematologic malignancies: an individual patient data meta-analysis of nine randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5074–5087. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroeder MA, DiPersio JF. Mouse models of graft-versus-host disease: advances and limitations. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4(3):318–333. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Socié G, Ritz J. Current issues in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2014;124(3):374–384. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-514752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogelsang GB. How I treat chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2001;97(5):1196–1201. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(12):945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavletic S, Martin P, Lee SJ, et al. Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: IV. Response Criteria Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(3):252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin PJ, Weisdorf D, Przepiorka D, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: VI. Design of Clinical Trials Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(5):491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Couriel D, Carpenter PA, Cutler C, et al. Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(4):375–396. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer JM, Lee SJ, Chai X, et al. Poor agreement between clinician response ratings and calculated response measures in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(11):1649–1655. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inamoto Y, Martin PJ, Storer BE, et al. Association of severity of organ involvement with mortality and recurrent malignancy in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Haematologica. 2014;99(10):1618–1623. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.109611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inamoto Y, Jagasia M, Wood WA, et al. Investigator feedback about the 2005 NIH diagnostic and scoring criteria for chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(4):532–538. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arora M, Pidala J, Cutler CS, et al. Impact of prior acute GVHD on chronic GVHD outcomes: a chronic graft versus host disease consortium study. Leukemia. 2013;27(5):1196–1201. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baird K, Steinberg SM, Grkovic L, et al. National Institutes of Health chronic graft-versus-host disease staging in severely affected patients: organ and global scoring correlate with established indicators of disease severity and prognosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(4):632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pidala J, Chai X, Kurland BF, et al. Analysis of gastrointestinal and hepatic chronic graft-versus-host disease manifestations on major outcomes: a Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease Consortium study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(5):784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuzmina Z, Eder S, Bohm A, et al. Significantly worse survival of patients with NIH-defined chronic graft-versus-host disease and thrombocytopenia or progressive onset type: results of a prospective study. Leukemia. 2012;26(4):746–756. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobsohn DA, Kurland BF, Pidala J, et al. Correlation between NIH composite skin score, patient reported skin score, and outcome: results from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 2012;120(13):2545–2552. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-424135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pidala J, Vogelsang G, Martin P, et al. Overlap subtype of chronic graft-versus-host disease is associated with an adverse prognosis, functional impairment, and inferior patient-reported outcomes: a Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Consortium study. Haematologica. 2012;97(3):451–458. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.055186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pidala J, Kurland B, Chai X, et al. Patient-reported quality of life is associated with severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease as measured by NIH criteria: report on baseline data from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 2011;117(17):4651–4657. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-319509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arai S, Jagasia M, Storer B, et al. Global and organ-specific chronic graft-versus-host disease severity according to the 2005 NIH Consensus Criteria. Blood. 2011;118(15):4242–4249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pidala J, Kurland BF, Chai X, et al. Sensitivity of changes in chronic graft-versus-host disease activity to changes in patient-reported quality of life: results from the Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Consortium. Haematologica. 2011;96(10):1528–1535. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.046367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grkovic L, Baird K, Steinberg SM, et al. Clinical laboratory markers of inflammation as determinants of chronic graft-versus-host disease activity and NIH global severity. Leukemia. 2012;26(4):633–643. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greinix HT, Loddenkemper C, Pavletic SZ, et al. Diagnosis and staging of chronic graft-versus-host disease in the clinical practice. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(2):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herzberg PY, Heussner P, Mumm FH, et al. Validation of the human activity profile questionnaire in patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(12):1707–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho B-S, Min C-K, Eom K-S, et al. Feasibility of NIH consensus criteria for chronic graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia. 2009;23(1):78–84. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vigorito AC, Campregher PV, Storer BE, et al. Evaluation of NIH consensus criteria for classification of late acute and chronic GVHD. Blood. 2009;114(3):702–708. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jagasia M, Giglia J, Chinratanalab W, et al. Incidence and outcome of chronic graft-versus-host disease using National Institutes of Health consensus criteria. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(10):1207–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arora M, Nagaraj S, Witte J, et al. New classification of chronic GVHD: added clarity from the consensus diagnoses. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43(2):149–153. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pérez-Simón JA, Encinas C, Silva F, et al. Prognostic factors of chronic graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: the National Institutes Health Scale plus the type of onset can predict survival rates and the duration of immunosuppressive therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(10):1163–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clements PJ, Lachenbruch PA, Seibold JR, et al. Skin thickness score in systemic sclerosis: an assessment of interobserver variability in 3 independent studies. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(11):1892–1896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flowers ME, Apperley JF, van Besien K, et al. A multicenter prospective phase II randomized study of extracorporeal photopheresis for treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008;112(7):2667–2674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-141481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inamoto Y, Flowers ME. Treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease in 2011. Curr Opin Hematol. 2011;18(6):414–420. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32834ba87d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koreth J, Matsuoka K, Kim HT, et al. Interleukin-2 and regulatory T cells in graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2055–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greinix HT, van Besien K, Elmaagacli AH, et al. Progressive improvement in cutaneous and extracutaneous chronic graft-versus-host disease after a 24-week course of extracorporeal photopheresis-results of a crossover randomized study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(12):1775–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bacigalupo A, Lamparelli T, Bruzzi P, et al. Antithymocyte globulin for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in transplants from unrelated donors: 2 randomized studies from Gruppo Italiano Trapianti Midollo Osseo (GITMO). Blood. 2001;98(10):2942–2947. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finke J, Bethge WA, Schmoor C, et al. Standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin in haematopoietic cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors: a randomised, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):855–864. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Socie G, Schmoor C, Bethge WA, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease: long-term results from a randomized trial on graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin ATG-Fresenius. Blood. 2011;117(23):6375–6382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soiffer RJ, Lerademacher J, Ho V, et al. Impact of immune modulation with anti-T-cell antibodies on the outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2011;117(25):6963–6970. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Devine SM, Carter S, Soiffer RJ, et al. Low risk of chronic graft-versus-host disease and relapse associated with T cell-depleted peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia in first remission: results of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network protocol 0303. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(9):1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luznik L, Bolanos-Meade J, Zahurak M, et al. High-dose cyclophosphamide as single-agent, short-course prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2010;115(16):3224–3230. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raj K, Pagliuca A, Bradstock K, et al. Peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation of hematological diseases from related, haploidentical donors after reduced-intensity conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(6):890–895. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flowers ME, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA, et al. Comparative analysis of risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease and for chronic graft-versus-host disease according to National Institutes of Health consensus criteria. Blood. 2011;117(11):3214–3219. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee SJ, Flowers MED. Recognizing and managing chronic graft-versus-host disease. In: Gewirtz AM, Muchmore EA, Burns LJ, editors. Hematology 2008: American Society of Hematology Education Program Book. Washington, DC: American Society of Hematology; 2008. pp. 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inamoto Y, Storer BE, Petersdorf EW, et al. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of sclerosis in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2013;121(25):5098–5103. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-464198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carpenter PA. How I conduct a comprehensive chronic graft-versus-host disease assessment. Blood. 2011;118(10):2679–2687. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-314815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carpenter PA. GVHD Assessment Video: How to Conduct a Comprehensive Chronic GVHD Assessment. http://www.fhcrc.org/en/labs/clinical/projects/gvhd.html. Accessed July 31, 2014.

- 51.Flowers MED. Emerging strategies in the treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease: traditional treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease (symposium report).; Blood Marrow Transplant Rev; 2002. pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolff D, Gerbitz A, Ayuk F, et al. Consensus conference on clinical practice in chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD): first-line and topical treatment of chronic GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(12):1611–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin PJ, Gilman AL. Front line treatment of chronic graft versus host disease. In: Vogelsang GB, Pavletic SZ, editors. Chronic Graft Versus Host Disease: Interdisciplianry Management. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin PJ, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA, Lee SJ, Flowers ME. Treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease: past, present and future. Korean J Hematol. 2011;46(3):153–163. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2011.46.3.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jabs K, Sullivan EK, Avner ED, Harmon WE. Alternate-day steroid dosing improves growth without adversely affecting graft survival or long-term graft function. A report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study. Transplantation. 1996;61(1):31–36. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199601150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martin PJ, Storer BE, Rowley SD, et al. Evaluation of mycophenolate mofetil for initial treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113(21):5074–5082. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-202937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sullivan KM, Witherspoon RP, Storb R, et al. Prednisone and azathioprine compared with prednisone and placebo for treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease: prognostic influence of prolonged thrombocytopenia after allogeneic marrow transplantation. Blood. 1988;72(2):546–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flowers ME, Martin PJ. Evaluation of thalidomide for treatment or prevention of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44(7):1141–1146. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000079096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilman AL, Schultz KR, Goldman FD, et al. Randomized trial of hydroxychloroquine for newly diagnosed chronic graft-versus-host disease in children: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koc S, Leisenring W, Flowers ME, et al. Therapy for chronic graft-versus-host disease: a randomized trial comparing cyclosporine plus prednisone versus prednisone alone. Blood. 2002;100(1):48–51. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flowers ME, Storer B, Carpenter P, et al. Treatment change as a predictor of outcome among patients with classic chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(12):1380–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Inamoto Y, Flowers ME, Sandmaier BM, et al. Failure-free survival after initial systemic treatment of chronic graft-versus host disease. Blood. 2014;124(8):1363–1371. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-563544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolff D, Schleuning M, von Harsdorf S, et al. Consensus Conference on Clinical Practice in Chronic GVHD: second-line treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flowers MED, Deeg HJ. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. In: Treleaven J, Barrett AJ, editors. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Clinical Practice. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier Ltd; 2009. pp. 401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takahide K, Parker PM, Wu M, et al. Use of fluid-ventilated, gas-permeable scleral lens for management of severe keratoconjunctivitis sicca secondary to chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(9):1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carpenter PA, Schubert MM, Flowers ME. Cevimeline reduced mouth dryness and increased salivary flow in patients with xerotomia complicating chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(7):792–794. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Inamoto Y, Flowers ME, Lee SJ, et al. Influence of immunosuppressive treatment on risk of recurrent malignancy after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;118(2):456–463. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gyurkocza B, Storb R, Storer BE, et al. Nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(17):2859–2867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Flowers MED, Vogelsang GB. Clinical manifestations and natural history. In: Vogelsang GB, Pavletic SZ, editors. Chronic Graft Versus Host Disease: Interdisciplinary Management. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yanik GA, Mineishi S, Levine JE, et al. Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor: enbrel (etanercept) for subacute pulmonary dysfunction following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(7):1044–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]