In this analysis of a phase III trial in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases, treatment with denosumab reduced the risk of skeletal complications vs zoledronic acid regardless of whether the end point was defined as SSE or SRE. Both SSEs and SREs were associated with development of moderate/severe pain among patients with no/mild pain at baseline.

Keywords: denosumab, zoledronic acid, symptomatic skeletal events, skeletal-related events, prostate cancer, phase III

Abstract

Background

In a phase III trial in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and bone metastases, denosumab was superior to zoledronic acid in reducing skeletal-related events (SREs; radiation to bone, pathologic fracture, surgery to bone, or spinal cord compression). This study reassessed the efficacy of denosumab using symptomatic skeletal events (SSEs) as a prespecified exploratory end point.

Patients and methods

Patients with CRPC, no previous bisphosphonate exposure, and radiographic evidence of bone metastasis were randomized to subcutaneous denosumab 120 mg plus i.v. placebo every 4 weeks (Q4W), or i.v. zoledronic acid 4 mg plus subcutaneous placebo Q4W during the blinded treatment phase. SSEs were defined as radiation to bone, symptomatic pathologic fracture, surgery to bone, or symptomatic spinal cord compression. The relationship between SSE or SRE and time to moderate/severe pain was assessed using the Brief Pain Inventory Short Form.

Results

Treatment with denosumab significantly reduced the risk of developing first SSE [HR, 0.78; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66–0.93; P = 0.005] and first and subsequent SSEs (rate ratio, 0.78; 95% CI 0.65–0.92; P = 0.004) compared with zoledronic acid. The treatment differences in the number of patients with SSEs or SREs were similar (n = 48 and n = 45, respectively). Among patients with no/mild pain at baseline, both SSEs and SREs were associated with moderate/severe pain development (P < 0.0001). Fewer patients had skeletal complications, particularly fractures, when defined as SSE versus SRE.

Conclusion

In patients with CRPC and bone metastases, denosumab reduced the risk of skeletal complications versus zoledronic acid regardless of whether the end point was defined as SSE or SRE.

introduction

Skeletal-related events (SREs) are an objective, clinically relevant end point for the evaluation of disease-related complications in patients with bone metastases [1]. In most clinical trials, SREs have been defined as radiation to bone, pathologic fracture, surgery to bone, or spinal cord compression [2–4]. Among patients with prostate cancer and bone metastases, SREs are associated with a significant decrease in patient function and health-related quality of life [5]. The regulatory approval of several bone-targeted agents, including pamidronate, zoledronic acid, and denosumab, has been supported by their ability to reduce SREs [6–10].

Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody against RANK ligand. In a phase III trial in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer, treatment with denosumab was associated with a significant delay in the time to first on-study SRE (defined as radiation to bone, pathologic fracture assessed either clinically or through routine radiographic scans, surgery to bone, or spinal cord compression) compared with zoledronic acid (median, 20.7 versus 17.1 months) [11]. In that trial, first on-study pathologic fractures accounted for ∼15% of first SREs; most pathologic fractures were identified by scheduled skeletal surveys (at baseline and every 12 weeks on study) and did not require the presence of symptoms.

Recent phase III trials in patients with metastatic prostate cancer have used a new end point termed symptomatic skeletal events (SSEs), defined as radiation to bone, symptomatic pathologic fracture, surgery to bone, or symptomatic spinal cord compression [12–14]. In contrast with SREs, ascertainment of SSEs does not include scheduled radiographic assessments. SSE-based primary end points will be used in a phase III trial of radium-223 combined with abiraterone acetate in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02043678). The relationship between SREs and SSEs as measures of skeletal complications is undefined. The objective of this analysis was to assess SSEs as a prespecified exploratory end point in the pivotal phase III trial of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases.

patients and methods

patients

This is an analysis of patients from a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00321620) [11]. Eligible patients were men (aged ≥18 years) with histologically confirmed prostate cancer, serum testosterone <50 ng/dl following chemical/surgical castration, prior hormonal therapy, radiographic evidence of bone metastasis, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≤2, and adequate renal and hepatic function. Patients were excluded if they had any prior denosumab or bisphosphonate treatment, investigational product exposure or participated in another clinical trial within the previous 30 days; planned radiotherapy or surgery to bone; brain metastasis; osteonecrosis or osteomyelitis of the jaw or jaw condition requiring oral surgery; nonhealed or planned dental/oral surgery; or life expectancy <6 months. Patients provided written informed consent; the study protocol was approved by each site's ethics committee.

study design and treatment

Patients were randomly assigned to receive either subcutaneous denosumab 120 mg plus i.v. placebo every 4 weeks or subcutaneous placebo plus i.v. zoledronic acid 4 mg every 4 weeks. Zoledronic acid doses were adjusted for renal function per the label using the Cockcroft-Gault formula and withheld for significant renal deterioration during the study. Denosumab doses were not adjusted. Daily supplementation with calcium (≥500 mg) and vitamin D (≥400 IU) was recommended unless hypercalcemia developed. Randomization was stratified by previous SRE (yes versus no), prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level (<10 ng/ml versus ≥10 ng/ml), and current (within 6 weeks before randomization) chemotherapy for prostate cancer (yes versus no).

statistical analysis

The primary end point of the phase III study was time to first on-study SRE (assessed as noninferiority), defined as radiation therapy to bone (including radioisotopes), pathologic fracture (excluding trauma), surgery to bone, or spinal cord compression as previously reported [11]. Radiographic skeletal surveys of the skull, spine, chest, pelvis, arm (from shoulder to elbow), and leg (from hip to knee) were performed within 4 weeks before randomization, every 12 weeks thereafter, and at the end-of-study visit. Fractures and spinal cord compression were confirmed radiologically by a central reader. The analyses were based on the data up to the primary analysis cutoff (when ∼745 patients experienced an on-study SRE).

In this analysis, SSEs as a preplanned exploratory end point were defined as a subset of SREs considered symptomatic by the investigators at the time the event was first noted. Events that became symptomatic at a later date were not recorded in the database; therefore, they were not able to be included in the analyses of SSE. SSEs were defined as radiation to bone, symptomatic pathologic fractures, surgery to bone, or symptomatic spinal cord compression. Time to first SSE, defined as the time from randomization to first occurrence of SSE as noted by the investigators, was assessed using a Cox proportional hazards model stratified by the randomization stratification factors, with treatment groups as the independent variable. Patients without a known SSE were censored at the last date on study or at the primary analysis cutoff date, whichever came first. Time to a subsequent SSE was defined as the time from randomization to the subsequent SSE occurring ≥21 days after the previous SSE. The multiple event analysis (time to first and subsequent SSE) was assessed using an Andersen-Gill model stratified by the randomization stratification factors. There was no adjustment for multiplicity in the analyses.

SSEs and SREs by type (radiation to bone, fracture, surgery to bone, spinal cord compression) were also summarized. For first skeletal events, data for each type of SRE/SSE were assessed without considering when the other event types occurred. For first and subsequent events, if multiple event types occurred on the same day, only one was selected because they were typically related (e.g. surgery to bone following symptomatic pathologic fracture); the following hierarchical order was used: (i) spinal cord compression, (ii) surgery to bone, (iii) fracture, and (iv) radiation to bone. For these reasons, some first and subsequent event types may not have been counted, resulting in a lower incidence than for first skeletal events (see Table 1). The data for the first SSE/SRE by type of first SSE/SRE were also presented with consideration of when the other event types occurred (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Confirmed on-study skeletal events: comparison of SSEs and SREs

| Event | SRE | SSE | Difference (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First skeletal event,a n | 937 | 641 | 296 |

| Spinal cord compressionb | 82 | 78 | 4 |

| Surgery to bone | 24 | 24 | 0 |

| Fracturec | 328 | 36 | 292 |

| Radiation to bone | 503 | 503 | 0 |

| First and subsequent skeletal event,c n | 1078 | 738 | 340 |

| Spinal cord compressionb | 81 | 78 | 3 |

| Surgery to bone | 12 | 15 | −3 |

| Fractureb | 391 | 32 | 359 |

| Radiation to bone | 594 | 613 | −19 |

Data shown are the first of each SRE/SSE event type (radiation to bone, fracture, or surgery to bone, or spinal cord compression) without considering when the other event types first occurred.

For SSE, the incidence of symptomatic pathologic fractures and symptomatic spinal cord compression is shown. For SRE, the incidence of pathologic fractures and spinal cord compression is shown.

For first and subsequent skeletal events, regardless of whether assessed as SRE or SSE, only events occurring ≥21 days after the previous event were counted, and if multiple event types occurred on the same day, only one event was counted based on the following priority order (based on severity): (i) spinal cord compression, (ii) surgery to bone, (iii) fracture, and (iv) radiation to bone. For these reasons, some first and subsequent events may not have been counted, resulting in a lower incidence than first skeletal events (e.g. 15 versus 24 surgery to bone events assessed as SSE).

Table 2.

Confirmed on-study SSEs and SREs by treatment arm

| Event | Zoledronic acid (n = 951) | Denosumab (n = 950) | Difference (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First SSE,a n | 289 | 241 | 48 |

| Symptomatic spinal cord compression | 38 | 26 | 12 |

| Surgery to bone | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Symptomatic pathologic fracture | 13 | 9 | 4 |

| Radiation to bone | 233 | 203 | 30 |

| First SRE,a n | 386 | 341 | 45 |

| Spinal cord compression | 36 | 26 | 10 |

| Surgery to bone | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Pathologic fracture | 143 | 137 | 6 |

| Radiation to bone | 203 | 177 | 26 |

| First and subsequent SSEs, n | 409 | 329 | 80 |

| Symptomatic spinal cord compression | 43 | 35 | 8 |

| Surgery to bone | 8 | 7 | 1 |

| Symptomatic pathologic fracture | 17 | 15 | 2 |

| Radiation to bone | 341 | 272 | 69 |

| First and subsequent SREs, n | 584 | 494 | 90 |

| Spinal cord compression | 44 | 37 | 7 |

| Surgery to bone | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| Pathologic fracture | 203 | 188 | 15 |

| Radiation to bone | 330 | 264 | 66 |

Data shown are for the first of any event type (radiation to bone, fracture, surgery to bone, or spinal cord compression) in the first SRE/SSE, with consideration of when the other event types occurred.

Among patients with no/mild pain at baseline, the association between first on-study SSE or SRE and time to moderate or severe pain (>4-point worst pain score per the Brief Pain Inventory Short Form) [15] was assessed using a Cox proportional hazards model with the first on-study SSE or SRE (as a time-dependent covariate), respectively, and with the baseline covariates (including number of baseline bone metastases, baseline analgesic score, baseline worst pain score, region, ethnic group/race), and stratified by treatment and the randomized stratification factors. Patients' first on-study SSE/SRE was assessed beginning 28 days before the SSE/SRE occurrence.

results

patients

Overall, 951 patients randomized to zoledronic acid and 950 patients randomized to denosumab in the phase III study were evaluable for efficacy in the primary analysis. As reported previously [11], age, ECOG performance status, and the randomization stratification factors (baseline PSA ≥10 ng/ml, chemotherapy ≤6 weeks before randomization, and previous SRE) were balanced between treatment arms.

incidence of symptomatic skeletal events and skeletal-related events

In a comparison of SSE and SRE as end points, there were 296 fewer first on-study SSEs than first on-study SREs (641 versus 937, respectively), and there were 340 fewer first and subsequent on-study SSEs than first and subsequent on-study SREs (738 versus 1078; Table 1). As anticipated, first on-study pathologic fractures were less numerous when defined as SSE than when defined as SRE (36 versus 328), as were first and subsequent on-study fractures (32 versus 391). In addition, the numbers of first on-study surgery to bone, first radiation to bone, and first spinal cord compression were similar when defined as SSE or SRE.

symptomatic skeletal events and skeletal-related events by treatment group

The numbers of patients with first on-study SSE were fewer in the denosumab arm (n = 241) versus the zoledronic acid arm (n = 289; Table 2); similar results were observed for patients with a first on-study SRE. Among the patients with a confirmed first on-study SSE, the numbers of patients in the denosumab and zoledronic acid arms with each event type (radiation to bone, symptomatic pathologic fracture, surgery to bone, and symptomatic spinal cord compression) were similar except for radiation to bone, which was less frequent in the denosumab arm than in the zoledronic acid arm (203 versus 233); similar results were observed for patients with a first on-study SRE.

First and subsequent on-study SSEs occurred in fewer patients in the denosumab arm (n = 329; 0.35 mean events per patient) versus the zoledronic acid arm (n = 409; 0.43 mean events per patient; Table 2); similar results were observed for patients with first and subsequent on-study SREs. Among the patients with first and subsequent on-study SSEs, the numbers of patients in the zoledronic acid and denosumab arms with each event type were similar except for radiation to bone, which was less frequent in the denosumab arm than in the zoledronic acid arm (272 versus 341); similar results were observed for patients with first and subsequent on-study SREs.

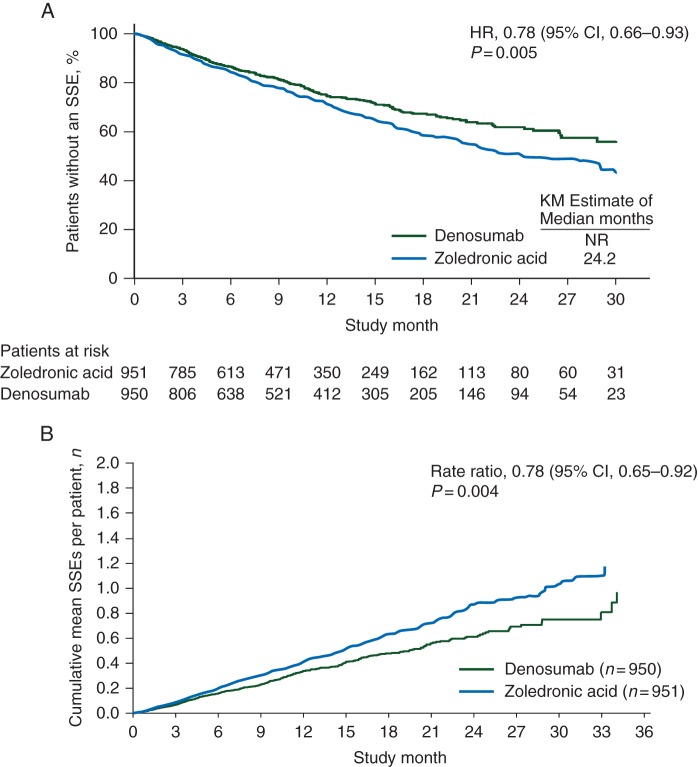

risk of symptomatic skeletal events and skeletal-related events

Compared with zoledronic acid, denosumab reduced the risk of first on-study SSE by 22% [HR, 0.78; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66–0.93; P = 0.005; Figure 1A]. Similarly, denosumab reduced the risk of first and subsequent on-study SSE by 22% versus zoledronic acid (rate ratio, 0.78; 95% CI 0.65–0.92; P = 0.004; Figure 1B). The median time to first on-study SSE was not reached in the denosumab arm and was 24.2 months in the zoledronic acid arm. As previously reported [11], denosumab reduced the risk of first on-study SRE, as well as the risk of first and subsequent SRE, by 18% versus zoledronic acid.

Figure 1.

(A) Time to first on-study SSE and (B) first and subsequent on-study SSE. KM, Kaplan-Meier; NR, not yet reached.

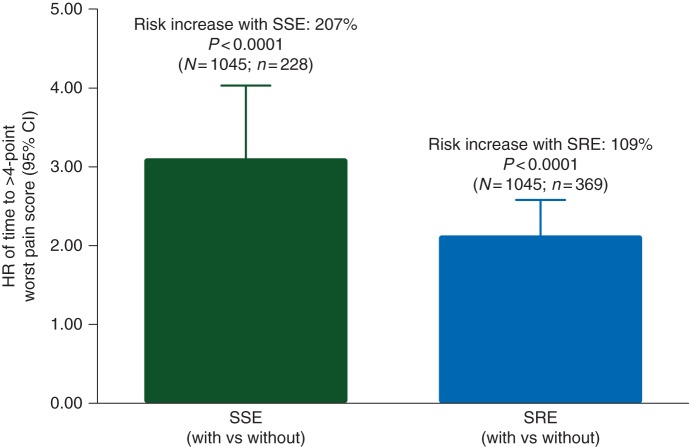

effect of first skeletal-related event and symptomatic skeletal event on time to moderate or severe pain (>4-point worst pain score)

Among patients with no/mild pain at baseline, the risk of developing moderate to severe pain on study was increased for patients with a first on-study occurrence of either an SSE (HR, 3.07; 95% CI 2.34–4.03; P < 0.0001) or an SRE (HR, 2.09; 95% CI 1.69–2.58; P < 0.0001; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of first on-study SSE and SRE (versus no SSE or SRE, respectively) on the risk of time to >4-point worst pain score (moderate or severe pain) in patients with no/mild pain at baseline. N designates the number of patients with baseline worst pain score ≤4 points; n designates the number of patients with a first on-study SSE/SRE, beginning 28 days before the SSE/SRE occurrence.

discussion

In this analysis of a phase III trial in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases, treatment with denosumab was associated with a reduced risk of skeletal complications compared with zoledronic acid regardless of whether the end point evaluated was SSE or SRE. The observed treatment effect for denosumab was similar whether skeletal complications were defined as SSE (22% risk reduction) or SRE (18% risk reduction) [11]. Both SSEs and SREs were associated with an onset of moderate or severe pain among patients with no/mild pain at baseline.

Our observation that denosumab reduced the risk of skeletal complications similarly whether defined as SSE or SRE is consistent with the results of other studies of bone-targeted agents. In phase III studies of zoledronic acid in patients with metastatic prostate cancer, the extent of the reduction in skeletal complications by zoledronic acid versus placebo appears to be similar whether defined as SSE (12% reduction) [14] or SRE (9% reduction) [16].

SSEs include symptomatic pathologic fractures but not asymptomatic, radiographically identified fractures, and it has therefore been argued that SSEs may be a more clinically relevant end point. However, evidence from an analysis of a multicenter, randomized trial of zoledronic acid in patients with prostate cancer and bone metastases suggested that any SRE (radiation to bone, pathologic fracture, spinal cord compression, surgery to bone, or change in antineoplastic therapy to treat bone pain) ultimately has the potential to decrease patient-reported quality of life [5]. In this population of patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases, we have shown that both SSEs and SREs overall were associated with an increased risk of moderate or severe pain among patients with no/mild pain at baseline.

Several studies have shown evidence of benefit from bone-targeted therapy in patients with bone metastases [17]. In an analysis of phase III trials in patients with bone metastases from solid tumors (other than breast or prostate cancer), treatment with denosumab was associated with a reduced risk of SREs, as well as delayed time to moderate or severe pain, worsened pain, and increased pain interference versus zoledronic acid among patients without pain at baseline [18]. Similarly, in a combined analysis of three phase III trials in patients with bone metastases from breast cancer, castration-resistant prostate cancer, or other solid tumors, treatment with denosumab was associated with delayed time to moderate or severe pain and pain interference among patients without pain at baseline, and a reduced risk of worsened health-related quality of life versus zoledronic acid [15]. Treatment with denosumab was associated with delayed time to increased pain interference, as well as greater cancer-specific quality of life versus zoledronic acid [19]. The benefit of denosumab has also been demonstrated in patients previously treated with a bisphosphonate [20, 21].

Our analyses of SSEs excluded asymptomatic fractures and asymptomatic spinal cord compression identified by study-specified scheduled radiographic assessments. The required radiographic assessments, however, may have resulted in increased ascertainment of symptomatic events prompted by more intense clinical evaluation following an abnormal imaging study. Any study that requires scheduled radiographic assessment shares this potential limitation of ascertainment bias for determination of ‘symptomatic’ skeletal events. Alternatively, because any skeletal event has the potential to become symptomatic over time, this study may have underestimated the number of symptomatic fractures for some patients.

In summary, denosumab reduced the risk of skeletal complications compared with zoledronic acid in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases regardless of whether the end point was defined as SSE or SRE. Both SREs and SSEs were associated with development of moderate/severe pain among patients with no/mild pain at baseline. These analyses provide further evidence for the superior ability of denosumab to prevent skeletal complications versus zoledronic acid.

funding

This work was supported by Amgen Inc.

disclosure

MRS has served as a consultant for Amgen Inc. REC has received honoraria from Amgen Inc. and Bayer and has provided expert testimony for Novartis. LK has received honoraria from Amgen Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, Ferring, Janssen, Dendreon, Merck, and Profound; has participated in advisory boards for Amgen Inc., Dendreon, Janssen, Ferring, GlaxoSmithKline, and Profound; and has received research funding from Bayer/Algeta, Ferring, Abbott, GlaxoSmithKline, and EMD Serono. KP has served on advisory boards and as a speaker for Amgen Inc. and Novartis. SN has served on advisory boards for Amgen Inc., Sanofi, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Astellas, and Pfizer. KNC has served on advisory boards for Amgen Inc. and Novartis. KF has served on advisory boards and as a speaker for Amgen Inc. and Novartis. AB, RW, HW, and AB are employees of and stockholders in Amgen Inc. PM declares no conflict of interest.

acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Ben Scott (whose work was funded by Amgen Inc.) and Lori (Gorton) Smette (Amgen Inc.) for assistance in writing this manuscript.

references

- 1.Saylor PJ, Armstrong AJ, Fizazi K, et al. New and emerging therapies for bone metastases in genitourinary cancers. Eur Urol. 2013;63:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bubendorf L, Schopfer A, Wagner U, et al. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:578–583. doi: 10.1053/hp.2000.6698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman RE. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer. 1997;80:1588–1594. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1588::aid-cncr9>3.3.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6243s–6249s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinfurt KP, Li Y, Castel LD, et al. The significance of skeletal-related events for the health-related quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:579–584. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aredia® (pamidronate disodium) Full Prescribing Information. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zometa® (zoledronic acid) Full Prescribing Information. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceutical Corp; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.XGEVA® (denosumab) Full Prescribing Information. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Medicines Agency (EMA) Summary of Product Characteristics. West Sussex, UK: Novartis Europharm Limited; 2014. Zometa® (zoledronic acid) [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Medicines Agency (EMA) Summary of Product Characteristics. Breda, The Netherlands: Amgen Europe B.V.; 2014. XGEVA® (denosumab) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fizazi K, Carducci M, Smith M, et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet. 2011;377:813–822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sartor O, Coleman R, Nilsson S, et al. Effect of radium-223 dichloride on symptomatic skeletal events in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases: results from a phase 3, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:738–746. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James ND, Pirrie S, Brown JE, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with castrate-refractory prostate cancer (CRPC) metastatic to bone randomized in the factorial TRAPEZE trial to docetaxel (D) with strontium-89 (Sr89), zoledronic acid (ZA), neither, or both (ISRCTN 12808747) J Clin Oncol. 2013;31 abstr LBA5000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Moos R, Body JJ, Egerdie B, et al. Pain and health-related quality of life in patients with advanced solid tumours and bone metastases: integrated results from three randomized, double-blind studies of denosumab and zoledronic acid. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:3497–3507. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1932-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1458–1468. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.19.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipton A, Fizazi K, Stopeck AT, et al. Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of 3 pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3082–3092. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry D, Vadhan-Raj S, Hirsh V, et al. Delaying skeletal-related events in a randomized phase 3 study of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in patients with advanced cancer: an analysis of data from patients with solid tumors. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:679–687. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrick D, Cleeland C, Fallowfield L, et al. Denosumab or zoledronic acid (ZA) therapy on pain interference and cancer-specific quality of life (CSQoL) in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and bone metastases (BM) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32 abstr 12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Body JJ, Lipton A, Gralow J, et al. Effects of denosumab in patients with bone metastases with and without previous bisphosphonate exposure. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:440–446. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fizazi K, Bosserman L, Gao G, et al. Denosumab treatment of prostate cancer with bone metastases and increased urine N-telopeptide levels after therapy with intravenous bisphosphonates: results of a randomized phase II trial. J Urol. 2009;182:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.023. discussion 515–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]