Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to determine which visitation policy was the most predominant in Brazilian intensive care units and what amenities were provided to visitors.

Methods

Eight hundred invitations were sent to the e-mail addresses of intensivist physicians and nurses who were listed in the research groups of the Brazilian Association of Intensive Care Network and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network. The e-mail contained a link to a 33-item questionnaire about the profile of their intensive care unit.

Results

One hundred sixty-two questionnaires from intensive care units located in all regions of the country, but predominantly in the Southeast and South (58% and 16%), were included in the study. Only 2.6% of the intensive care units reported having liberal visitation policies, while 45.1% of the intensive care units allowed 2 visitation periods and 69.1% allowed 31-60 minutes of visitation per period. In special situations, such as end-of-life cases, 98.7% of them allowed flexible visitation. About half of them (50.8%) did not offer any bedside amenities for visitors. Only 46.9% of the intensive care units had a family meeting room, and 37% did not have a waiting room.

Conclusion

Restrictive visitation policies are predominant in Brazilian intensive care units, with most of them allowing just two periods of visitation per day. There is also a lack of amenities for visitors.

Keywords: Visitors to patients, Patient-centered-care/standards, Professional-family relations, Professional-patient relations, Intensive care units/standards, Questionnaires

Abstract

Objetivo

Este estudo teve como objetivo determinar a política de visitação predominante nas unidades de terapia intensiva e quais comodidades proporcionadas aos visitantes.

Métodos

Foram enviados 800 convites a endereços de e-mail de médicos e enfermeiros intensivistas listados nos grupos de pesquisa da Rede da Associação de Medicina Intensiva Brasileira e da Rede Brasileira de Pesquisa em Terapia Intensiva. A mensagem por e-mail continha um link para um questionário de 33 itens a respeito do perfil de suas respectivas unidades de terapia intensiva.

Resultados

Foram incluídos no estudo os questionários de 162 unidades de terapia intensiva localizadas em todas as regiões do país, mas foram predominantes as das Regiões Sudeste (58%) e Sul (16%). Apenas 2,6% das unidades de terapia intensiva relataram ter políticas liberais de visitação, enquanto 45,1% das unidades de terapia intensiva possibilitavam dois períodos diários de visitação e 69,1% permitiam de 31 a 60 minutos de visita por período. Em situações especiais, como casos de fim de vida, 98,7% delas permitiam visitas em horários flexíveis. Cerca de metade das unidades de terapia intensiva (50,8%) não oferecia qualquer comodidade aos visitantes. Apenas 46,9% das unidades de terapia intensiva tinham uma sala de reunião com familiares, e 37% não dispunham de uma sala de espera.

Conclusão

Nas unidades de terapia intensiva do Brasil, houve predominância de políticas restritivas de visitação, sendo que a maioria delas só permite dois períodos diários de visitação. Também há uma ausência de comodidades para os visitantes.

INTRODUCTION

An admission into the intensive care unit (ICU) is a stressful event for both patients and their families. Many studies have shown symptoms including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress among family members of ICU patients.(1-3) The need to stay close to the patient and to receive adequate information, as noted since Molter’s(4) study in 1979, is still relevant. Recent studies show that the need to be close to patients and the anxiety of leaving them alone causes family members to choose to sleep in the waiting room.(5) Moreover, incomplete or misunderstood information are risk factors for cases of post-traumatic stress disorder in patients’ families.(3) Therefore, family conferences, where a family has an opportunity to express their feelings and receive answers to their questions, not only increases their satisfaction but also can decrease their symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress.(6) The lack of a waiting room close to the patient, inaccessible doctors and incomplete information are also risk factors for dissatisfaction.(7,8)

In recent years, the pursuit of improved care for critically ill patients with a holistic approach has been evident. Patient- and family-centered care has increased and is aimed at improving treatment quality, as well as patient and family satisfaction. One of the proposals is to provide an open visitation policy for families of critically ill patients.(9,10)

In general, the visitation periods in many ICUs have been described as restrictive or open/liberal. ICUs with restrictive policies are those that allow family visits during certain periods of the day, with a restricted number of visitors per period. Those with open visitation policies allow the family access to the patient 24 hours a day, with or without a restriction on the number of visitors.(11-13) In the last decade, intensive care has evolved all around the world, but there are still no specific rules or a consensus about visitation policies. Open visitation is common in pediatric ICUs; however, it is still rare in adult ICUs.(11) Many studies from Europe(13-17) and the USA(18) have shown that most ICUs still have restrictive policies to this day.

The open visitation policy, which allows family to support the patient, has been demonstrated to improve communication between family and ICU staff, as well as their satisfaction with the treatment.(8,19) A randomized study correlated open visitation policies with a decrease in patient anxiety, improvements to their hormonal profiles and a decrease in cardiovascular complications.(20)

The interaction between families and doctors is very important in the ICU. An inaccessible staff and inefficient communication have strong impacts on satisfaction.(7) Although communication is necessary and important, communication failures between family and staff occur approximately 50% of the time, with the prognosis being the most difficult message to understand.(21,22) However, a lack of staff training on interacting with families was revealed in a recent study regarding perceptions of a 24-hour visitation policy. According to that study, there is a need for training in communication.(23) In addition, there are other barriers to the adoption of open visitation policies, such as lack of space, communication issues, conflicts and workloads.(11,12,19) There is also concern that an open visitation policy can increase stress for family members, who may feel obligated to stay in the ICU.(11,12,19) Regarding the staff, although they feel that the presence of families disrupts their work, they believe that the benefits are worth the trouble, especially for the patients.(9,20,23,24)

In 2007, the American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCCM) published guidelines in support of families, in the context of patient-centered care, supporting an open visitation policy with the recommendation that the visitation policy be established on a case-by-case according to the patient’s best interest.(10)

The European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), through their Working Group of Quality Improvement (WGQI), published their basic recommendations for structural and organizational aspects of ICU in 2008.(25) In that document, the ESICM recommended that the reception areas of ICU have at least 10m² of space per eight beds, with 1.5 to 2 chairs per bed, and also suggested rooms for resting be available to the families, along with other amenities, such as restrooms, telephones, radios and televisions. The document does not mention a minimum time allowance for family members to stay in the ICU.

In Brazil, laws on that matter are not clear. Resolution-RDC number 7 from February 24, 2010, in Section V and Article 25, declares that the presence of visitors in the ICU must be regulated by the institution’s policy and based on the law. Law 10741 from October 1, 2003, which dictates the Statute of the Elderly, allows that elderly patients have a companion present throughout the entirety of their hospital stay. However, there are no studies or data on the characteristics of the visitation policies in Brazilian adult ICU.

The aim of this study is to determine which visitation policy is predominant in Brazilian ICU and what facilities and amenities are offered to ICU visitors.

METHODS

This study was a descriptive, multicenter survey in which intensivist physicians and nurses with e-mail addresses listed in the Associação de Medicina Intensiva Brasileira network (AMIBNet) and Brazilian Research in Intensive Care network (BRICNet) were invited to participate. The invitation e-mail gave both the survey link (https://www.surveymonkey.com/politicadevisitaUTI) and the access password. After agreeing with the participation terms, the participants were directed to a questionnaire (available in the electronic supplementary materials) with 33 questions on the following regarding their facility: (1) ICU structure (specialty, funding source, number of beds, separation between beds); (2) visitation policy (number of visitation periods and length of the periods); (3) visitors (number of visitors allowed, relation to the patient, age limit); (4) infection control measures; and (5) amenities for visitors (waiting room, chairs, food, brochures with information about the ICU). The exclusion criteria included the ICU and/or city not being identified or more than 50% of questions not being answered.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Instituto de Ensino e Pesquisa of the Hospital Sírio Libanês with registration number HSL 2012/29.

Statistical analysis

According to the AMIB 2010 census,(26) there were approximately 2400 ICU eligible for inclusion in this study. The estimate of the percentage of ICU with open visitation policies was 10%, thus, considering a confidence interval of 95%, it would be necessary to sample 131 ICU.

The data analysis was performed using STATA® 12 (StataCorp LP, USA). Categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Quantitative variables are expressed as central trend (mean and median) and dispersion measures. Nominal data were compared with the Chi-squared test for trends.

RESULTS

A total of 800 invitations were sent via e-mail to intensivist physicians and nurses. Of those, 191 accessed the electronic questionnaire; however, 29 were excluded due to incomplete and duplicate questionnaires. Thus, 162 surveys were included in the analysis. There were 154 questionnaires (95.1%) completed by physicians and the remainder were completed by nurses.

Profiles of the units

The profiles of the participating ICU are presented in tables 1 and 2. The questionnaires came from all regions of the country; however, seven states were not represented (Acre, Amapá, Alagoas, Mato Grosso, Paraíba, Roraima and Tocantins). The Southeast region contributed most of the data, at a total of 59% of the questionnaires, followed by the South (15.6%). The results showed that 46.3% of the ICU were publicly funded, 75.3% had a clinical-surgical specialty, and 49.1% had six to ten beds. Furthermore, 92% of the ICU had intensivist physicians present on a daily basis.

Table 1.

Profile of the intensive care units according to location

| Region | Number of cities | Number of ICU | Public ICU |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) | N (%) | |

| North | 6 | 7 (4.3) | 6 (85.7) |

| Northeast | 9 | 21 (13) | 9 (43) |

| Center-west | 5 | 14 (8.7) | 5 (35.7) |

| Southeast | 29 | 94 (58) | 43 (45.7) |

| South | 15 | 26 (16) | 14 (53.9) |

ICU - intensive care units.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the intensive care units

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Funding source | |

| Public | 75 (46.3) |

| Private | 69 (42.6) |

| Philanthropic | 18 (11.1) |

| Specialty | |

| Clinical | 19 (11.7) |

| Surgical | 7 (4.3) |

| Clinical-surgical | 122 (75.3) |

| Other | 14 (8.7) |

| Number of beds | |

| Up to 10 | 81 (52) |

| 11-20 | 57 (35.8) |

| 21 and greater | 21 (13.2) |

| Number of annual admissions | |

| Up to 400 | 54 (34.4) |

| 401-800 | 59 (37.6) |

| >800 | 44 (28) |

| Daily presence of an intensivist | |

| Yes | 149 (92) |

| No | 13 (8) |

Family visitation policies and general conditions

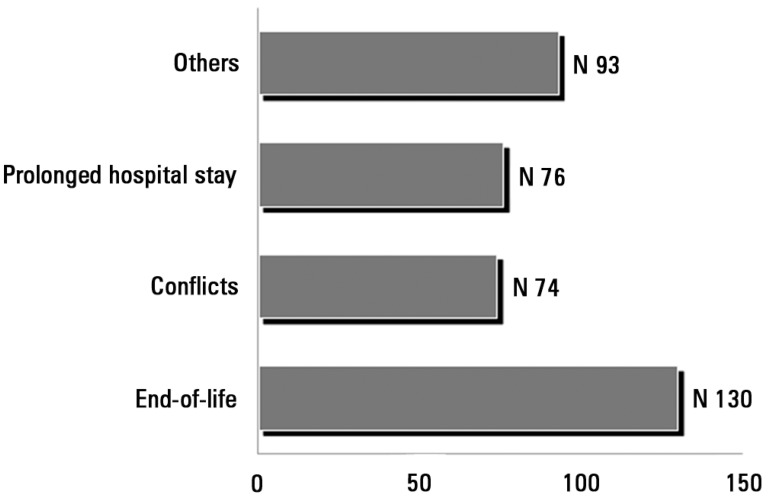

Only 2.6% of the ICU had liberal visitation policies (24 hours), while 45.1% of the ICU had 2 visitation periods and 69.1% allowed 31-60 minutes of visitation per period. However, 98.7% of the ICU allowed for flexible visitation times in special situations, mainly for end-of-life cases (Figure 1). Table 3 displays the main characteristics of visitation policies in Brazilian ICU.

Figure 1.

Main reason for flexibility of the visitation policy.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the visitation policy of the participant intensive care units

| Visitation policy characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Visiting periods | |

| None | 0 |

| 1 | 52 (32.1) |

| 2 | 73 (45.1) |

| 3 | 26 (16) |

| >3 | 11 (6.8) |

| Time per visiting period | |

| <30 min | 12 (7.4) |

| 31-60 min | 112 (69.1) |

| 61-360 min | 31 (19.1) |

| 6-12 hours | 3 (1.8) |

| 24 hours | 4 (2.6) |

| Visitors per period | |

| 1 | 35 (21.9) |

| 2 | 108 (67.5) |

| 3 | 10 (6.2) |

| 4 | 7 (4.4) |

| Only family members allowed | |

| Yes | 8 (5) |

| No | 151 (95) |

| Restriction to the visitor's age | |

| None | 20 (12.5) |

| >12 years old | 123 (76.9) |

| >16 years old | 17 (10.6) |

| Visitation flexibility in special cases | |

| Yes | 158 (98.7) |

| No | 2 (1.2) |

Regarding infection control measures, 96.9% of the ICU recommended hand washing. Only 2.4% recommended the use of protective coverings, such as gowns, surgical caps, shoe covers and masks, for all visitors.

There was no correlation between funding sources and visiting periods (p=0.15) or between funding sources and the flexibility of visiting hours (p=0.95).

Amenities offered to visitors

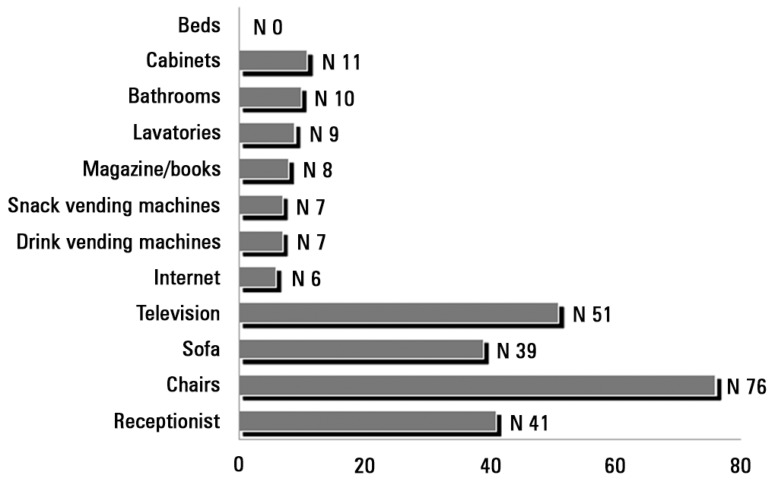

Regarding conveniences for visitors, 50.8% of the ICU did not offer any accommodations. Only 46.9% had family meeting rooms. However, 63% of the ICU had waiting rooms. Regarding informational materials, 55.6% of the ICUs offered some type of informational material about the unit, primarily brochures (Table 4). Figure 2 shows the amenities that were available to visitors in ICU waiting rooms.

Table 4.

Amenities for visitors

| Amenities for visitors | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Separation between beds | |

| None | 14 (8.6) |

| Curtain | 63 (38.9) |

| Panel screen | 8 (4.9) |

| Room divider | 51 (31.5) |

| Individual room | 26 (16.1) |

| Bedside amenities | |

| None | 89 (50.8) |

| Chair | 40 (23) |

| Armchair | 41 (23.4) |

| Sofa | 5 (2.8) |

| Bed | 0 |

| Family meeting room | |

| Yes | 76 (46.9) |

| No | 86 (53.1) |

| Information over the phone | |

| Yes | 112 (69.1) |

| No | 50 (30.8) |

| Informational material | |

| Yes | 90 (55.6) |

| No | 72 (44.4) |

| Family satisfaction evaluation | |

| Yes | 60 (37) |

| No | 102 (63) |

| ICU waiting room | |

| Yes | 102 (63) |

| No | 60 (37) |

ICU - intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

Amenities offered to the visitors in intensive care unit waiting rooms.

Participant’s opinions of intensive care unit visitation policies

When asked about their personal opinions regarding their institution’s visitation policies, 38.6% responded that they believed that the policy was adequate, 58.1% believed that the policy should be more liberal in terms of the time and number of visitors allowed, and 3.2% believed that it should be more restrictive. Furthermore, 98.8% of the participants considered the presence of a visitor to be very important or important to the patient. Of those surveyed, 100% believed that the ability to visit the patient is important or very important to the visitor. Additionally, 39.7% believed that the presence of visitors made the staff’s work easier, while 34% did not see any difference and 26.3% felt that it disrupted their work.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate ICU visitation policies in a Latin American country. The sample, although small, represents the distribution of the ICU in Brazil’s regions very well, with the majority being from the Southeast.

The main finding of this study was that a small number of ICU have open visitation policies. It is certain that in other countries, restrictive visitation policies are predominant; however, there is growing recognition of more liberal visitation policies, with some countries already changing their policies. Furthermore, the time allowed per visit is longer in other countries, with more restrictive visits than we found in our study. For instance, a French multicentric study showed that 97% of the participating ICU had a restrictive visitation policy, but the average time per visit was 168 minutes.(14) Studies show a large variation in visitation policies.(13-18) Areas with the greatest percentage of liberal ICU visitation policies are the New England region of the USA (32%)(18) and the United Kingdom (19.9%).(16)

We found that a significant number of Brazilian ICU do not have a waiting room. Having a waiting room in the ICU and the ability to see patients frequently are among the greatest needs of the families of ICU patients and are factors associated with the greatest family satisfaction. When compared to European studies,(13-18) where most of the ICU have waiting rooms and some include a sleeping area,(17) we still have a long way to go to comply with ESICM recommendations.(25) Of the amenities offered to visitors in the waiting room, the most common are chairs and televisions.

Furthermore, almost half of the ICU do not have a family meeting room. Based on previous studies,(6,27,28) in which the relevance of family conferences was demonstrated, these data also require attention. Family conferences, especially in end-of-life situations, can help to reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress. In these difficult moments, a family conference, with the physician actively listening to the family’s doubts and feelings, can significantly increase the family’s satisfaction.(6,29,30)

Our study showed that there is an acknowledgment that the presence of families at the bedside of patients in end-of-life situations is important and must be continued. Most of the participants in this study (98.7%) reported that visitation policies are flexible in the face of conflicts, primarily end-of-life situations, which is a common practice in other countries with restrictive visitation policies.

Regardless of that acknowledgement, interestingly, we found that half of the ICUs do not provide any amenities to visitors. The lack of appropriate space for visitors at bedsides is, without a doubt, one of the impediments to liberal visitation policies. According to this study, in most cases, divider curtains and screens separate beds in ICU, and only 16.1% of the units have individual patient rooms.

The presence of the family in the ICU is still controversial. In 2001, the American College of Critical Care published their guidelines regarding patient-centered care in the ICU and recommended that the open visitation policy be decided individually, respecting the wishes of the patient, the family and the nursing staff.(10) An open visitation policy ensures that some of the family’s needs are addressed, such as being with the patient more often, as well as regularly receiving information about the patient’s condition.

According to health care professionals, particularly ones who work in ICU, although open visitation policies are beneficial to patients and their families, they are associated with an increased workload and may cause work disruptions.(11,12,23,24)

A recent study conducted in the ICU of a private hospital in Brazil showed that physicians, nurses and physical therapists realize that open visitation policies are beneficial, especially for patients, but not as much for families and ICU staff.(23) Although the length of the visit is not related to mortality and the length of hospitalization,(27) it is related to a reduction in patient anxiety, an improvement in their hormonal profiles and a decrease in cardiovascular complications.(20) On the other hand, patients may prefer to have visitors for a shorter period of time, to have greater constraints on the number of visitors, and to have privacy during intimate hygiene procedures.(28) In other words, the flexibility of visiting hours may be more important than their length.

The present study has some limitations: first, the relatively small numbers of responses, and second, the preponderance of responses from the Southeast region.

CONCLUSION

Despite the growing international and national recognition of the importance of an open visitation policy in intensive care units, this study shows that, in Brazil, policy may be too difficult to implement in reality, mainly due to hurdles caused by the lack of adequate structures for accommodating visitors. We found that half of the intensive care units surveyed do not have any amenities for visitors, not even chairs. Additionally, most of them do not have waiting rooms. However, almost all of them allow flexible visiting hours in end-of-life situations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care network (BRICnet) and Associação de Medicina Intensiva Brasileira network (AMIBnet) for their collaboration in the study. The authors thank Dr Ivany Schettino for her contribution in the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

Responsible editor: Gilberto Friedman

Author’s contributions

Fernando José da Silva Ramos and Renata Rego Lins Fumis: designed the study, collected data and prepared the manuscript; Luciano Cesar Pontes de Azevedo and Guilherme Schettino designed the study and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Hubert P, Canoui P, Grassin M, Zittoun R, le Gall JR, Dhainaut JF, Schlemmer B, French FAMIREA Group Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(10):1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fumis RR, Deheinzelin D. Family members of critically ill cancer patients: assessing the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(5):899–902. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, Fassier T, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goulenok C, Goldgran-Toledano D, Hayon J, Jourdain M, Kaidomar M, Laplace C, Larché J, Liotier J, Papazian L, Poisson C, Reignier J, Saidi F, Schlemmer B, FAMIREA Study Group Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molter NC. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: a descriptive study. Heart Lung. 1979;8(2):332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day A, Haj-Bakri S, Lubchansky S, Mehta S. Sleep, anxiety and fatigue in family members of patients admitted to the intensive care unit: a questionnaire study. Crit Care. 2013;17(3):R91. doi: 10.1186/cc12736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. Erratum in N Engl J Med. 2007;357(2):203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fumis RR, Nishimoto IN, Deheinzelin D. Families’ interactions with physicians in the intensive care unit: the impact on family’s satisfaction. J Crit Care. 2008;23(3):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Mokhtari M, Le Gall JR, Dhainaut JF, Schlemmer B, French FAMIREA Group Meeting the needs of intensive care unit patient families: a multicenter study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):135–139. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berwick DM, Kotagal M. Restricted visiting hours in ICUs: time to change. JAMA. 2004;292(6):736–737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, Spuhler V, Todres ID, Levy M, Barr J, Ghandi R, Hirsch G, Armstrong D, American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005, Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slota M, Shearn D, Potersnak K, Haas L. Perspectives on family-centered, flexible visitation in the intensive care unit setting. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5) Suppl:S362–S366. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000065276.61814.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berti D, Ferdinande P, Moons P. Beliefs and attitudes of intensive care nurses toward visits and open visiting policy. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(6):1060–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0599-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandijck DM, Labeau SO, Geerinckx CE, De Puydt E, Bolders AC, Claes B, Blot SI, Executive Board of the Flemish Society for Critical Care Nurses, Ghent and Edegem, Belgium An evaluation of family-centered care services and organization of visiting policies in Belgian intensive care units: a multicenter survey. Heart Lung. 2010;39(2):137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinio P, Savry C, Deghelt A, Guilloux M, Catineau J, de Tinténiac A. A multicenter survey of visiting policies in French intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(10):1389–1394. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giannini A, Miccinesi G, Leoncino S. Visiting policies in Italian intensive care units: a nationwide survey. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(7):1256–1262. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter JD, Goddard C, Rothwell M, Ketharaju S, Cooper H. A survey of intensive care unit visiting policies in the United Kingdom. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(11):1101–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spreen AE, Schuurmans MJ. Visiting policies in the adult intensive care units: a complete survey of Dutch ICUs. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2011;27(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MD, Friedenberg AS, Mukpo DH, Conray K, Palmisciano A, Levy MM. Visiting hours policies in New England intensive care units: strategies for improvement. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):497–501. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254338.87182.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Philippart F, Timsit JF, Diaw F, Willems V, Tabah A, et al. Perceptions of a 24-hour visiting policy in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(1):30–35. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000295310.29099.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fumagalli S, Boncinelli L, Lo Nostro A, Valoti P, Baldereschi G, Di Bari M, et al. Reduced cardiocirculatory complications with unrestrictive visiting policy in an intensive care unit: results from a pilot, randomized trial. Circulation. 2006;113(7):946–952. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.572537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fumis RR, Nishimoto IN, Deheinzelin D. Measuring satisfaction in family members of critically ill cancer patients in Brazil. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(1):124–128. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2857-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(8):3044–3049. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.da Silva Ramos FJ, Fumis RR, Azevedo LC, Schettino G. Perceptions of an open visitation policy by intensive care unit workers. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3(1):34. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-3-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biancofiore G, Bindi LM, Barsotti E, Menichini S, Baldini S. Open intensive care units: a regional survey about the beliefs and attitudes of healthcare professionals. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76(2):93–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valentin A, Ferdinande P, ESICM Working Group on Quality Improvement Recommendations on basic requirements for intensive care units: structural and organizational aspects. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(10):1575–1587. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Associação de Medicina Intensiva Brasileira - AMIB Censo AMIB. [Accessed in 02/20/2013]. http://www.amib.org.br/fileadmin/CensoAMIB2010.pdf

- 27.Eriksson T, Bergbom I. Visits to intensive care unit patients-frequency, duration and impact on outcome. Nurs Crit Care. 2007;12(1):20–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2006.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez CE, Carroll DL, Elliott JS, Fitzgerald PA, Vallent HJ. Visiting preferences of patients in the intensive care unit and in a complex care medical unit. Am J Crit Care. 2004;13(13):194–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Shannon SE, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1484–1488. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Rubenfeld GD. The family conference as a focus to improve communication about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: opportunities for improvement. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2) Suppl:N26–N33. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]