Abstract

Objective

Bullying has been identified as a potential contributing factor in youth suicide. This issue has been highlighted in recent widely publicized media reports, worldwide, in which deceased youth were bullied. We report on an observational study conducted to determine the frequency of bullying as a contributing factor to youth suicide.

Method:

Coroner records were reviewed for all suicide deaths in youth aged between 10 and 19 in the city of Toronto from 1998 to 2011. Data abstracted were recent stressors (including bullying), clinical variables, such as the presence of mental illness, demographics, and methods of suicide.

Results:

Ninety-four youth suicides were included in the study. The mean age was 16.8 years, and 70.2% were male. Bullying was present in 6 deaths (6.4%), and there were no deaths where online or cyberbullying was detected. Bullying was the only identified contributing factor in fewer than 5 deaths. The most common stressors identified were conflict with parents (21.3%), romantic partner problems (17.0%), academic problems (10.6%), and criminal and (or) legal problems (10.6%). Any stressor or mental and (or) physical illness was detected in 78.7% of cases. Depression was detected in 40.4% of cases.

Conclusions:

Our study highlights the need to view suicide in youth as arising from a complex interplay of various biological, psychological, and social factors of which bullying is only one. It challenges simple cause-and-effect models that may suggest that suicide arises from any one factor, such as bullying.

Keywords: suicide, youth, stressors, depression, bullying

Abstract

Objectif :

L’intimidation a été identifiée comme étant un facteur contributif potentiel du suicide chez les adolescents. Cette question a été mise en évidence dans de récents reportages des médias largement publicisés, dans le monde entier, dans lesquels des jeunes décédés avaient été intimidés. Nous rendons compte d’une étude d’observation menée afin de déterminer la fréquence de l’intimidation comme facteur contributif du suicide chez les adolescents

Méthode :

Les dossiers du coroner ont été examinés pour tous les décès par suicide chez les adolescents entre 10 et 19 ans dans la ville de Toronto, de 1998 à 2011. Les données extraites étaient des stresseurs récents (dont l’intimidation), des variables cliniques, comme la présence de maladie mentale, des données démographiques, et les méthodes de suicide.

Résultats :

Quatre-vingt-quatorze suicides d’adolescents ont été inclus dans l’étude. L’âge moyen était de 16,8 ans et 70,2 % étaient des garçons. L’intimidation était présente dans 6 décès (6,4 %), et il n’y avait pas de décès où la cyber-intimidation ou l’intimidation en ligne était détectée. L’intimidation était le seul facteur contributif identifié dans moins de 5 décès. Les stresseurs les plus communs identifiés étaient le conflit avec les parents (21,3 %), les problèmes avec un partenaire sexuel (17,0%), les problèmes scolaires (10,6 %), et les problèmes criminels et (ou) juridiques (10,6 %). Un stresseur ou une maladie mentale et (ou) physique était détecté dans 78,7 % des cas. La dépression a été détectée dans 40,4% des cas.

Conclusions :

Notre étude fait ressortir le besoin de voir que le suicide chez les adolescents découle d’une interaction complexe entre divers facteurs biologiques, psychologiques et sociaux, et l’intimidation n’est qu’un de ceux-là. Cela remet en question les modèles simples de cause à effet qui peuvent suggérer que le suicide est attribuable à un facteur unique, comme l’intimidation.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among youth aged 15 to 24 in Canada after accidental death1 and the third leading cause of death in US youth after accidental death and homicide.2 Suicide death in all age groups, and in youth specifically, is thought to arise as a result of complex interactions between biological, psychiatric, and social factors.3 The stress–diathesis model proposes that negative life events interact with biological and cognitive predispositions, including mental illness, to confer a heightened risk of engaging in suicidal behaviour.3–5 Therefore, numerous variables must be considered when attempting to understand suicidal behaviour and death.

Bullying fits under the umbrella of negative life events or stressors that could possibly precipitate suicidal ideation, which, in turn, can lead to suicide attempts. While empirical research has demonstrated associations between bullying and suicidal ideation and (or) attempts,6–14 most authors have identified numerous variables that mediate or moderate the relation, such as internalizing symptoms (for example, worry, fear, and somatic complaints),6 mental health problems,13 depression,7,11,12 substance use, violent or impulsive behaviour,11,13 and being the victim of domestic abuse or violence.13 For instance, recent data identify an attenuation of the relation between bullying and suicidal ideation and (or) behaviours when depression and delinquency are controlled.15 Karch et al16 examined 1046 suicide deaths among youth aged 10 to 17 in the United States and found that mental illness and (or) substance abuse, intimate partner or other relationship problems, and school problems were the most common precipitating circumstances, with bullying accounting for 12.4% of school problems, translating into 3.2% of all cases.

Since October 2012, there have been several widely reported suicide deaths in youth in Canada, the United States, and worldwide that were presented in the media as resulting from bullying and, often in particular, online or cyberbullying.17–24 Following one of the deaths, vigils were held in 40 cities around the world to “remember bullying victims.”25, p 1 While media reports often explicitly or implicitly argue for a direct causal relation between bullying and suicide, no study has systematically examined the frequency of bullying among suicide deaths in a large metropolitan sample, an important consideration given that most of these widely reported cases occurred in youth living in small towns and (or) communities,18–22,24 whereas more than 80% of Canadians and Americans live in urban areas.26,27 Research examining data prior to 2012, such as our study, will be an important precursor for determining whether bullying as a frequent contributing factor in youth suicide deaths predates these reports or whether the increased media attention itself may be eliciting the well-described copycat phenomenon seen with sensationalized media reporting about suicide.28 To that end, our study aims to describe all youth suicides in Toronto from 1998 to 2011, with an emphasis on reporting contributing and (or) precipitating stressors, in particular the presence of bullying. The a priori hypothesis was that bullying would be identified in a minority of suicide deaths but that many other previously identified factors, such as mental illness, relationship problems, and academic problems, would be more prevalent.

Clinical Implications

Numerous stressors, including bullying, can put youth at risk for suicide.

Mental illness is also a crucial contributor to youth suicide, both alone and in combination with psychosocial stressors.

Clinically, suicide is treated as a complex problem arising from the interplay of multiple biological and psychosocial factors. Broader population health strategies and media reporting related to suicide should have a similar emphasis.

Limitations

Reporting of stressors, including bullying, may be incomplete.

Our study examined bullying as a proximate risk to suicide, but bullying in the more distant past could also have had an influence.

The lack of a living control group means that our study could not rigorously measure the strength of association between bullying and suicide deaths.

Method

Our study is a part of the larger Toronto Analysis of Suicide for Knowledge and Prevention (commonly referred to as TASK-P) study; details of the methodology were previously published.29 Data were systematically extracted from charts of the Office of the Chief Coroner (OCC) of Ontario for all suicide deaths in the city of Toronto from 1998 to 2011, and our paper focuses exclusively on youth aged 19 and younger. The OCC does not rule suicide as the cause of death in children under the age of 10; therefore, the sample comprised everyone who died from suicide between the ages of 10 and 19. Information about suicide deaths that occurred after 2011 were not part of the study, as it takes about 2 years for all OCC investigations to be completed. Each chart contained a coroner’s investigation report and pathology report, with extensive information gathered by the OCC as part of the determination of the cause and particulars of the death. Additional information was collected by the OCC from transcripts of interviews with family, acquaintances, and physicians, letters from family members, police reports, hospital records, and copies of suicide notes when available. A standardized data extraction procedure was used to collect data on the following:

- Interpersonal stressors within the past year, including:

- Bullying (defined as any indication from the coroner’s investigation that the youth had experienced peer intimidation and (or) victimization by being, for example, teased, ridiculed, tormented, assaulted, or otherwise harassed by a peer or peers), including whether the bullying was noted to have occurred online.

- Parent conflict: conflict about school grades and (or) attendance; verbal, physical, and (or) sexual abuse by a parent; other (conflict about friends, habits, or behaviour).

- Intimate partner problems: relationship breakup; conflict with current boyfriend or girlfriend (not identified as involving bullying as defined above).

- Other (other interpersonal losses and [or] difficulties or a fight with peer[s] not involving bullying).

Other stressors: police and (or) legal (defined as being wanted, arrested, or charged by police, currently in jail or in the midst of court proceedings, or recently placed on probation or parole); Children’s Aid Society involvement; immigration (defined as difficulties related to immigration, such as problems adjusting to life in Canada); employment and (or) financial; medical and (or) health; bereavement.

Demographics: age; sex; living circumstances (whether the youth was living with family or friends, alone, or in a shelter, group home, jail, or long-term inpatient setting).

Clinical variables: mental health diagnoses (depression; substance abuse, including alcohol, drugs, or both; psychotic disorder; other mental illness, including all other disorders, such as bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, disruptive behaviour disorders, personality disorders, and eating disorders); known past suicide attempts; current and (or) recent hospitalization (defined as being currently admitted to a psychiatry ward or having been discharged in the past week); comorbid medical conditions.

Details of suicide: method (hanging, other asphyxia, drowning and [or] hypothermia, self-poisoning, jump and [or] fall from height, or subway, train, and [or] motor vehicle collision, cutting and [or] stabbing, or shooting); location of death; presence of a suicide note.

Two of our study investigators provided onsite training to 2 research assistants who independently coded each chart for the presence or absence of each of the variables listed above, including interpersonal stressors. One research assistant then reviewed each case where an interpersonal stressor had been identified to determine the type of stressor, including bullying. The investigators and research assistants were in contact on a weekly basis to address any questions and reach consensus regarding coding for more complex charts. Demographic data and details of the suicide were available in 100% of OCC charts. Stressor and clinical variables were only included in the OCC charts if they were positive. That is, it is possible, for example, that a youth was experiencing bullying, conflict with parents, or legal difficulties that were not captured in OCC records; although, for this to have occurred, the deceased’s next of kin would have had to be unaware or to have withheld this information from the OCC during the investigation into the cause of death. Nevertheless, all stressor and clinical variables should be considered estimates, with possible underreporting.

The OCC granted approval for our study and provided full access to their records for the purposes of completing our study. Our study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto. We fully adhered to the strict privacy procedures used by the OCC, with all extracted data maintained in an encrypted and de-identified format. To protect the privacy of specific suicide victims, we suppressed data involving fewer than 5 deaths.

Results

There were 94 youth who died from suicide in Toronto during the 14-year study period (6.7 deaths/year). The mean age was 16.8 years (14 deaths in youth aged 10 to 14 years; 35 deaths in those aged 15 to 17 years; 45 deaths in those aged 18 to 19 years). More than two-thirds (70.2%) of suicide victims were male, and 79 (84.0%) were living with their family or a friend at the time of their death. Twenty-eight (29.8%) left a suicide note.

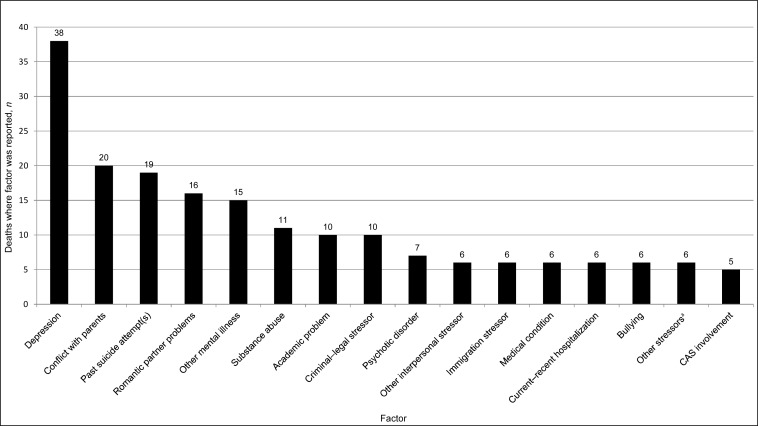

Factors that the coroner identified as preceding the suicide are shown in Figure 1. The most common factors were depression (51.3%) and conflict with parents (27.0%). Bullying was present in 6 deaths (8.1%) and it was the only identified contributing factor in fewer than 5 deaths. All bullying-related deaths involved in-person bullying or bullying by phone. That is, there were no deaths where online or cyberbullying was detected. Immigration-related stressors and a medical condition were each present at the same rate as bullying (8.1% each). Stressors that were more common than bullying included criminal and (or) legal issues, academic problems, and romantic partner problems.

Figure 1.

Potential contributing factors identified in 74 youth suicide deaths in Toronto

a Stressors identified in fewer than 5 cases combined into Other stressors

CAS = Children’s Aid Society

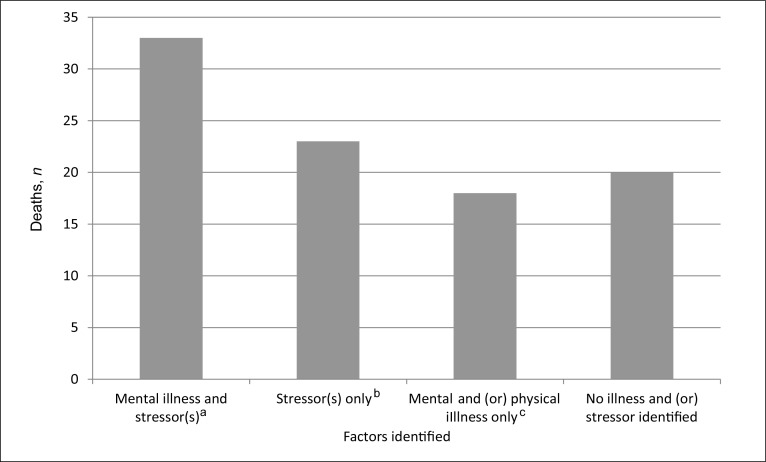

Coroner records detected any stressor or mental and (or) physical illness in 74 of 94 (78.7%) cases. The pattern of stressors, and (or) illness identified, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Pattern of illness and stressor(s) identified in 94 youth suicide deaths in Toronto

a 1 mental illness and 1 stressor (n = 13); 1 mental illness and multiple stressors (n = 9); multiple mental illnesses and 1 stressor (n = 5); multiple mental illnesses and multiple stressors (n = 6)

b 1 stressor (n = 16); multiple stressors (n = 9)

c 1 mental and (or) physical illness (n = 10); multiple mental and (or) physical illnesses (n = 8)

Hanging and jumping from a height were the most common methods, accounting for 70% of deaths (36% and 34%, respectively).

Discussion

Our study confirms findings from 16 US states16 that bullying precipitates or is a proximate contributor to a relatively small proportion of all youth suicide deaths, with mental illness along with substance abuse, conflict with parents, and intimate partner, school, and legal problems all being more frequent precipitating factors. These findings underscore the need to understand suicide as arising from a complex interplay between psychiatric, social, and biological factors rather than from a simple cause-and-effect relation. As described in a recent editorial, “Conveying that bullying alone causes suicide at best minimizes, and at worst ignores, the other factors that may contribute to death by suicide.”30, p S2

Bullying is a ubiquitous phenomenon. A study of 25 countries found that involvement in bullying at least twice in the current school term as the bully, victim, or both occurred in 9% to 54% of students overall, with Canada having an intermediate rate of 20% to 30%.31 According to the 2006 Canadian Census, there were 287 245 youth between the ages of 10 and 19 living in Toronto.32 Using the conservative estimate of 10% of youth being bullied in a given year, we would expect more than 28 000 youth in Toronto to have experienced bullying in 2006 alone. This is in contrast to 6 suicide deaths during 14 years where bullying was detected as a precipitating factor, and it underscores that suicide death is thought to be a rare outcome in victims of bullying.9 Nevertheless, it should also be noted that our study cannot specifically address the issue of bullying severity given that there are no data on the percentage of youth in Toronto who experience more severe forms of bullying or whether these 6 youth fall into that category.

Our study is important because it is the first to systematically examine stressors, in particular bullying, that precede suicide death in Canadian youth and in a large metropolitan sample. However, it has several important limitations. Our study relied on coroner records and did not include our own interviews with the deceased’s next of kin. While the OCC conducts detailed investigations into the cause of death, not all details of mental illness or recent stressors may be known or reported by informants, meaning that rates of these factors may be underestimates. For example, one previous study assessing the interrater agreement between secondary school children and their mothers found that bullying was reported by 60% of mothers whose children endorsed bullying.33 Notably, the same study also found that mothers may overreport bullying, with only 45% of children agreeing with their mother’s assessment that they had been bullied.31 Nevertheless, it should be noted that, using the 60% figure as an estimate, the results and conclusions of our study would not differ if it had been 10 rather than 6 youth who were reported to have been bullied. It should also be assumed that nonbullying stressors may be underdetected and (or) -reported. Future studies involving more rigorous psychological autopsy methodologies, including interviews with relatives, may help to mitigate possible underdetection by the coroner. However, the modest agreement between child and parent and (or) teacher reporting of bullying in particular33–35 may reflect that youth can be reluctant to report bullying, even to those closest to them. Therefore, only a large prospective study involving reports from multiple sources, including the youth themselves, could truly address this limitation.

More severe forms of both bullying and other stressors may confer a greater risk of suicide. However, it is also likely that more severe bullying and (or) stressors would be better known to deceased’s next of kin, which may partially mitigate the limitation of using informants. Bullying also remains a risk factor for depression and suicidal behaviour months or years after it occurs.6,7,36 Therefore, while our study demonstrates only a small number of youth who experience bullying as a proximate risk factor for suicide, it was not designed to detect those for whom bullying was a problem in the more distant past. For example, it may be that bullying in the past contributed to the depression that was present and considered a contributing factor to death in 38 of the suicide victims. Equally, unidentified past parental conflict or academic problems could also have contributed to depression in these youth. This highlights perhaps the greatest limitation of our study: the lack of a living control group. To rigorously characterize differences in associations between stressors, such as bullying or parental conflict and suicide, one would need to compare rates of these stressors in suicide victims and in youth who do not die from suicide. A crude comparison yields a rate of about 6% (6/94) of suicide victims who were recently bullied, which is lower than overall population estimate (20% to 30%). Although this does not account for bullying severity, these results are in keeping with the only other large study of stressors in youth preceding suicide.16 Ultimately, further research is needed to more fully characterize the association. Regardless, it is important to contextualize these findings in relation to those for depression. The prevalence of depressive disorders in Canadian youth has been reported as 2.1%.37 This rate is in contrast to the 40% (38/94) of suicide cases where depression was detected. That is, depression is a relatively low-frequency event in youth that is significantly overrepresented in youth suicide victims. While more research is needed, it seems clear that this cannot be said for bullying. Finally, these results apply to a large metropolitan area, but it is unclear to what degree they are generalizable to other cities or communities. It is notable that most of the widely publicized youth suicide victims who were bullied came from small towns and (or) communities18–22,24 and, therefore, whether bullying is a more important factor in youth suicide in exurban and rural areas remains to be studied. It may be that bullying victims in large cities such as Toronto are less isolated, have more options in their social sphere, and better access to mental health treatment, all of which may be protective.

One important question is, will there be any negative effects of recent media reports that emphasize a cause-and-effect model for bullying and suicide and that they present as increasingly common? The commonly held social learning theory of suicide contagion38,39 posits that media reporting may increase suicide by making it seem more culturally acceptable or even glamorous. This concept is supported by a recent study showing that high school students exposed to a schoolmate’s suicide were at substantially higher risk of suicidal ideation and attempts (OR ranging from 1.83 [95% CI 1.04 to 3.21] to 6.46 [95% CI 3.56 to 11.72] depending on the specific age and whether examining ideation or attempts).40 Importantly, the effect held regardless of whether they personally knew the student who had died. Recent evidence has also demonstrated that media reporting on rare and (or) novel methods of suicide can contribute to a rapid increase in suicide deaths by that method and overall.41 Whether the same is true regarding wide dissemination of relatively rare motivations for suicide, such as being bullied, remains to be determined. Nevertheless, the moment of silence to remember one of the widely publicized Canadian victims of bullying observed by 250 000 students of the Toronto District School Board represents a potentially risky natural experiment.25 This goes beyond the scope of what our study can demonstrate; however, it would be important for future research to explore whether exposure to media reports, emphasizing the connection between bullying and suicide, may possibly confer a greater risk of suicide death than the actual bullying itself.

Conclusions

Our study confirms previous research that bullying is a relatively rare precipitating factor in suicide in youth, compared with other psychiatric and psychosocial stressors, and indeed that there are many factors that may proximately influence suicide death. The results support the notion that suicide prevention programs in this age group must be comprehensive to address as many of these factors as possible. Proposed approaches to suicide prevention in youth include school-based programs aimed at psychological well-being, encouraging help seeking behaviour, training teachers to detect at-risk students, improved screening programs, public awareness campaigns, decreasing stigma, helplines and (or) Internet resources, and restricting access to means.42 Regarding this last approach, the findings of this study, that hanging and, in an urban setting, jumping from a height are the most common methods of suicide in this age group, generally agree with previous findings in Canada and elsewhere,43–46 except in the United States where firearms account for the largest proportion of suicide deaths.47 They further underscore the difficulty in means restriction for suicide prevention in youth as the means of hanging and jumping are difficult to restrict at a population level. Given that depression has been shown to be an important mediator of suicide risk overall and specifically in bullying victims,15 programs targeting depression in victimized youth as well as those with other psychosocial stressors would be an important component of a suicide prevention program, both in terms of acute and long-term risk. One last approach that has been identified is to improve media reporting on suicide.40 Our study adds to a body of literature showing that youth suicide is often in response to various, different kinds of stressors. Population strategies that encourage psychological coping skills and resilience in response to stress in general have been identified as important components of suicide prevention efforts. Media reports emphasizing that bullying often leads directly to suicide are misleading, inaccurate, and run counter to that principle. Therefore, we suggest that the media ought to separate important public discussions of bullying from those about suicide and encourage a more nuanced and evidence-based discourse on this important topic.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr James Edwards, June Lindsell, Andrew Stephen, and the staff at the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario for their support in making this research possible. We also thank the Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation for their generous grant support for this project. We further thank Ms Catherine Reis, Ms Sophia Rinaldis, and Ms Michelle Messner for their efforts to make this work possible.

This study was part of a larger study of all suicides in Toronto that received funding from the Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation. The researchers were completely independent of the funding agency who had no input into the design, results or manuscript.

Dr Sinyor, Dr Schaffer, and Dr Cheung have no nonfinancial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work. Dr Cheung has acted as a consultant for Lundbeck, Sunovion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments. Dr Schaffer has also received grant funding from AstraZeneca Canada and Pfizer, has received payment for lectures, presentations, and speakers bureau honoraria from Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb and AstraZeneca Canada. Dr Sinyor and Dr Schaffer had support from the Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation for the submitted work.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (ID# 021–2011), Toronto.

References

- 1.Statistics Canada. CANSIM table 102–0561 [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2009. Ten leading causes of death by selected age groups, by sex, Canada—15 to 24 years, 2009. [cited 2013 Aug 29]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/84-215-x/2012001/tbl/T003-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Mortality among teenagers aged 12–19 years: United States, 1999–2006 [Internet] Hyattsville (MD): CDC; 2010. [cited 2014 Feb 6]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db37.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1–53. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1372–1381. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Heeringen K. Stress–diathesis model of suicidal behavior. In: Dwivedi Y, editor. The neurobiological basis of suicide. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2012. Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winsper C, Lereya T, Zanarini M, et al. Involvement in bullying and suicide-related behavior at 11 years: a prospective birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(3):271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meltzer H, Vostanis P, Ford T, et al. Victims of bullying in childhood and suicide attempts in adulthood. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(8):498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litwiller BJ, Brausch AM. Cyber bullying and physical bullying in adolescent suicide: the role of violent behavior and substance use. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42(5):675–684. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9925-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herba CM, Ferdinand RF, Stijnen T, et al. Victimization and suicide ideation in the TRAILS study: specific vulnerabilities of victims. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(8):867–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim Y, Leventhal BL, Koh Y, et al. School bullying and youth violence: causes or consequences of psychopathologic behavior? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(9):1035–1041. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher HL, Moffitt TE, Houts RM, et al. Bullying victimisation and risk of self harm in early adolescence: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2012;26:344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauman S, Toomey RB, Walker JL. Associations among bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide in high school students. J Adolesc. 2013;36(2):341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borowsky IW, Taliaferro LA, McMorris BJ. Suicidal thinking and behavior among youth involved in verbal and social bullying: risk and protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(1):S4–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hepburn L, Azrael D, Molnar B, et al. Bullying and suicidal behaviors among urban high school youth. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(1):93–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espelage DL, Holt MK. Suicidal ideation and school bullying experiences after controlling for depression and delinquency. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(1 Suppl):S27–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karch DL, Logan J, McDaniel DD, et al. Precipitating circumstances of suicide among youth aged 10–17 years by sex: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 states, 2005–2008. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(1 Suppl):S51–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyette C. NY police probe possible cyberbullying after girl found hanged [Internet] New York (NY): cnn.com; 2013. May 26, [cited 2013 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.cnn.com/2013/05/23/us/new-york-girl-death/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.FoxNews.com. Sheriff says Fla 12-year-old committed suicide after being bullied online by over a dozen girls [Internet] Lakeland (FL): FoxNews.com; 2013. Sep 12, [cited 2013 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.foxnews.com/us/2013/09/13/sheriff-says-fla12-year-old-committed-suicide-after-being-bullied-online-by. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golgowski N. Connecticut teen who committed suicide after first day of school underwent years of bullying say friends [Internet] New York (NY): New York Daily News; 2013. Sep 3, [cited 2013 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/connecticut-teen-committed-suicide-bullied-years-friends-article-1.1444213. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visser J. The justice system failed her: Nova Scotia teenager commits suicide after being raped, bullied: mother [Internet] Toronto (ON): The National Post; 2013. Apr 9, [cited 2013 Oct 3]. Available from: http://news.nationalpost.com/2013/04/09/the-justice-system-failed-her-nova-scotia-teenager-commits-suicide-after-being-raped-bullied-mother/. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung W, Bascaramurty D. Amanda Todd tragedy highlights how social media makes bullying inescapable [Internet] Toronto (ON): The Globe and Mail; 2012. Oct, [cited 2013 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/amanda-todd-tragedy-highlights-how-social-media-makes-bullying-inescapable/article4611068. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toronto Star. Bullying possible spark for suicide of Saskatchewan teen [Internet] Toronto (ON): Toronto Star; 2013. Sep 25, [cited 2013 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2013/09/25/bullying_possible_spark_for_suicide_of_saskatchewan_teen.html. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cramb A. Teenager committed suicide ‘after being blackmailed on skype’ [Internet] London (GB): The Telegraph; 2013. Aug 15, [cited 2013 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/10245809/Teenager-commited-suicide-after-being-blackmailed-on-Skype.html. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staff/Agency. 14-year-old girl commits suicide after bullying on question-and-answer website [Internet] London Evening Standard (Online Ed); 2013. Aug 7, [cited 2013 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/14yearold-girl-commits-suicide-after-bullying-on-questionandanswer-website-8747592.html. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bullying victims remembered in vigils worldwide [Internet] CBC News. 2012 Oct 19; [cited 2013 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/story/2012/10/18/toronto-bullying-silence.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26.United States Census Bureau. Census urban and rural classification and urban area criteria [Internet] Washington, (DC): United States Census Bureau; 2010. 2010. [cited 2014 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/ua/urban-rural-2010.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Statistics Canada. Population, urban and rural, by province and territory [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2011. [cited 2014 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/101/cst01/dem062a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pirkis J, Blood RW. Suicide and the media. Part I: Reportage in nonfictional media. Crisis. 2001;22(4):146–154. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.22.4.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Streiner D. Characterizing suicide in Toronto: an observational study and cluster analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(1):26–33. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hertz MF, Donato I, Wright J. Bullying and suicide: a public health approach. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(1 Suppl):S1–S3. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nansel TR, Craig W, Overpeck MD, et al. Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:730e6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Statistics Canada. Toronto, Ontario (Code3520005) (table). 2006 community profiles. 2006 Census. Statistics Canada catalogue no 92–591-XWE. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2007. Mar 13, [cited 2013 Oct 4]. Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/prof/92-591/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Code1=3520005&Geo2=PR&Code2=35&Data=Count&SearchText=toronto&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&Custom=. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shakoor S, Jaffee SR, Andreou P, et al. Mothers and children as informants of bullying victimization: results from an epidemiological cohort of children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011;39(3):379–387. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9463-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Løhre A, Lydersen S, Paulsen B, et al. Peer victimization as reported by children, teachers, and parents in relation to children’s health symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:278. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rønning JA, Sourander A, Kumpulainen K, et al. Cross-informant agreement about bullying and victimization among eight-year-olds: whose information best predicts psychiatric caseness 10–15 years later? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(1):15–22. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klomek AB, Kleinman M, Altschuler E, et al. Suicidal adolescents’ experiences with bullying perpetration and victimization during high school as risk factors for later depression and suicidality. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(1 Suppl):S37–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirby MJL, Keon WJ. Interim report of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. Report 1. Ottawa (ON): Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; 2004. Mental health, mental illness and addiction: overview of policies and programs in Canada. Chapter 5: prevalence and costs. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: towards a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirkis JE, Burgess PM, Francis C, et al. The relationship between media reporting of suicide and actual suicide in Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(11):2874–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swanson SA, Colman I. Association between exposure to suicide and suicidality outcomes in youth. CMAJ. 2013;185(10):870–877. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen YY, Chen F, Gunnell D, et al. The impact of media reporting on the emergence of charcoal burning suicide in Taiwan. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hepp U, Stulz N, Unger-Köppel J, et al. Methods of suicide used by children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(2):67–73. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0232-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pompili M, Vichi M, De Leo D, et al. A longitudinal epidemiological comparison of suicide and other causes of death in Italian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(2):111–121. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skinner R, McFaull S. Suicide among children and adolescents in Canada: trends and sex differences, 1980–2008. CMAJ. 2012;184(9):1029–1034. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Värnik A, Kõlves K, Allik J, et al. Gender issues in suicide rates, trends and methods among youths aged 15–24 in 15 European countries. J Affect Disord. 2009;113(3):216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Sheftall AH, et al. Changes in suicide rates by hanging and/or suffocation and firearms among young persons aged 10–24 years in the United States: 1992–2006. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(5):503–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]