Abstract

Objectives

To describe key findings relating to the natural history and heterogeneity of bipolar disorder (BD) relevant to the development of a unitary clinical staging model. Currently proposed staging models are briefly discussed, highlighting complementary findings, and a comprehensive staging model of BD is proposed integrating the relevant evidence.

Method:

A selective review of key published findings addressing the natural history, heterogeneity, and clinical staging models of BD are discussed.

Results:

The concept of BD has broadened, resulting in an increased spectrum of disorders subsumed under this diagnostic category. Different staging models for BD have been proposed based on the early psychosis literature, studies of patients with established BD, and prospective studies of the offspring of parents with BD. The overarching finding is that there are identifiable sequential clinical phases in the development of BD that differ in important ways between classical episodic and psychotic spectrum subtypes. In addition, in the context of familial risk, early risk syndromes add important predictive value and inform the staging model for BD.

Conclusions:

A comprehensive clinical staging model of BD can be derived from the available evidence and should consider the natural history of BD and the heterogeneity of subtypes. This model will advance both early intervention efforts and neurobiological research.

Keywords: clinical staging, bipolar disorder, high-risk, natural history, heterogeneity, clinical course, developmental course

Abstract

Objectifs :

Décrire les principaux résultats concernant l’histoire naturelle et l’hétérogénéité du trouble bipolaire (TB) qui se rapportent à l’élaboration d’un modèle unitaire de stades cliniques. Les modèles de staification présentement proposés sont brièvement présentés, de même que les résultats complémentaires, et un modèle complet de staification du TB est proposé qui intègre les données probantes pertinentes.

Méthode :

Est présentée une revue sélective des principaux résultats publiés sur l’histoire naturelle, l’hétérogénéité, et les modèles de staification clinique du TB.

Résultats :

Le concept du TB s’est élargi, ce qui a donné un spectre accru de troubles classés dans cette catégorie diagnostique. Différents modèles de staification du TB ont été proposés d’après la littérature sur la psychose précoce, les études de patients souffrant d’un TB établi, et les études prospectives des enfants de parents souffrant de TB. Le résultat déterminant est qu’il y a des phases cliniques séquentielles identifiables dans le développement du TB qui diffèrent de manière importante entre les sous-types épisodiques classiques et ceux du spectre psychotique. En outre, dans le contexte du risque familial, les syndromes de risque précoce ajoutent une valeur prédictive importante et éclairent le modèle de stadification du TB.

Conclusions :

Un modèle complet de stadification clinique du TB peut être déduit des données probantes disponibles et devrait tenir compte de l’histoire naturelle du TB et de l’hétérogénéité des sous-types. Ce modèle fera progresser les initiatives d’intervention précoce et la recherche neurobiologique.

Over the past 25 years, advances in psychiatric research that have translated into real differences in outcomes for patients have not been realized. This disappointing reality is in part the result of our diagnostic approach. Current diagnostic systems emphasize presenting symptoms without considering the context, important risk factors, and neglecting what we know about the natural history of illness development. As of 2010, acknowledging these significant limitations, the National Institute of Mental Health has sought alternative strategies to diagnosis.1 Further, the current approach is counter to other areas of medicine in which diagnosis is anchored in a solid understanding of the natural history of illness development and refined by the use of valid illness subtypes and individual risk factors to derive patient-specific predictions of illness risk, progression, treatment response, and overall prognosis.

Hope of progress in the psychiatry discovery landscape comes from the increasing recognition that clinical staging is a useful conceptual framework to refine the phenotype of illness along developmental lines. This approach supports the identification of markers of illness risk and progression, as well as stage-specific treatment targets.2–6 As pointed out by Scott et al,7 staging presupposes that illness evolves in an identifiable temporal progression of phases, that early intervention will be more effective, aiming to significantly prevent or delay illness progression and that treatments for the earlier phases of illness will be more acceptable to patients and have a higher benefit-to-risk ratio. The staging approach has been highly beneficial in the prevention and early identification of other complex (Gene × Environment) disorders, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and various forms of cancer.

In this paper, I summarize key findings about the natural history and heterogeneity of bipolar disorder (BD) relevant to clinical staging and discuss the currently debated approaches to staging, highlighting complementary aspects. I aim to help the reader understand the similarities and origins of the differences in published staging models of BD and propose a comprehensive staging framework based on the evidence to advance clinical and research outcomes.

Natural History and Heterogeneity of Bipolar Disorder

There is a wealth of evidence supporting that a recurrent episodic illness course is the hallmark of the classical form of BD (Kraepelinean manic depressive illness).8 The quality of remission and the frequency of recurrences are known to vary substantially between patients; however, over time, there is no systematic change in cycle length (time from the onset of one episode to the onset of the next episode) and the previous course is the best predictor of recurrence risk for individual patients.9,10 While progressive worsening of the course is often assumed,11 Oepen et al12 discussed the statistical artifact that led to this erroneous conclusion. This episodic recurrent form of BD is known to be associated with an increased rate of recurrent mood disorders, but not schizophrenia in relatives, and a high response rate to long-term lithium, estimated at 80%.13,14 A recent large prospective study15 of patients with classical BD reported that the morbidity index in lithium-treated patients remained stable for up to 20 years. Moreover, lithium response was found to cluster in affected members.16 Recent imaging studies have shown that long-term lithium treatment in these patients is neuroprotective.17–19

Clinical Implications

A developmental clinical staging approach represents an important advance supporting earlier and more accurate psychiatric diagnosis.

Clinical staging of BD must consider both the natural history of the disorder and the heterogeneity of the diagnosis.

A comprehensive evidence-based staging model of BD is important to advance early detection and intervention, as well as research aimed at identifying markers of illness predisposition and progression.

Limitations

The proposed staging model is an aggregate view derived from research studies and will not apply to all high-risk offspring or patients with BD.

The staging model will need to be refined and informed by future research advances.

Reflecting the broadening of the diagnostic criteria (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised, and beyond) and the preference to diagnose BD instead of psychotic disorders,20 there has been increased debate about progressively shortened cycle lengths and recasting BD as typically a progressive deteriorating illness.21 For example, using current diagnostic criteria, it has been estimated that the classical episodic lithium responsive subtype accounts for only 30% of patients in a typical Canadian subspecialty outpatient program.22

These observations underscore the importance of considering heterogeneity and the need to identify valid subtypes of BD to advance research and clinical practice outcomes.23 The classical episodic lithium responsive subtype now forms part of a much broader spectrum of BD. Evidence supports that subtypes defined by either prophylactic response or nonresponse to lithium differ in clinical course, family history, and neurobiological correlates.21,24,25 Lithium nonresponsive subtypes are more chronic disorders that preferentially respond to either atypical neuroleptics (psychotic spectrum) or to lamotrigine (BD II, comorbid anxiety disorders).10,26 Psychotic spectrum BD has overlapping neurobiological findings with psychotic disorders23 and a higher risk of chronic nonepisodic illnesses in family members, including schizophrenia.23,27 Further, imaging and genetic studies have shown reliable differences between lithium-responsive and lithium-nonresponsive BD.10,13,28,29

Clinical Staging: Clinical At Risk and Patient Studies

Research led by those in the early psychosis field has provided the initial support for the use of clinical staging in psychiatry. This research has provided important evidence in help seeking, ultra–high-risk youth of delayed or decreased rates of illness progression (transition to psychosis), as well as earlier diagnosis and effectiveness of more benign early stage treatments.30,31 In a recent prospective follow-up report, predictors of transition to psychosis included longer duration of symptoms, disorders of thought content and negative symptoms, consistent with a wealth of previous reports.32 Negative symptoms include affective flattening, anhedonia, apathy, and alogia, which overlap clinically with depressive spectrum presentations. A recent meta-analysis confirmed that youth at clinical or familial high-risk for psychosis show moderate cognitive deficits relative to control subjects and that these cognitive deficits predict transition to psychosis.33 The highest rate of cognitive deficits were reported in subjects at both clinical and familial risk for psychosis.

The extension of the early psychosis staging approach to BD is an area of intensive current interest.34 The possibility of pluripotential (shared) early stages across different disorders has been proposed based on a degree of overlap in nonspecific early risk syndromes.7,30,35 However, this proposal is problematic in many ways. It ignores the well-documented and striking differences in developmental history, early illness trajectories, and family history between prototypical schizophrenia and classical recurrent BD. The natural history of typical psychotic illness starts with neurodevelopmental disorders, including cognitive and motor deficits,36–38 academic decline,38–40 negative symptoms, and attenuated psychotic symptoms41,42; a positive family history in this model informs the risk status as an optional aspect only of the ultra–high-risk prodrome.

In contrast, the natural history of classical BD does not include cognitive and motor deficits nor academic decline through childhood.36,37,43 In fact, people who develop classical BD have normal or gifted premorbid academic and social functioning. Further, the family history typically includes recurrent mood disorders, not chronic psychotic illnesses.10,44,45 Granted there are intermediate clinical presentations and reports of overlapping genetic and neurobiological findings; however, in part this reflects the broadening of the BD concept20,46 and assortative mating.47,48

Another challenge to the proposal of simply generalizing the early psychosis model to mood disorders is that BD is not diagnosed until the manifestation of the first-activated (hypomanic or manic) episode; however, the classical disorder almost always starts with depressive episodes.49 Moreover, depressive episodes typically antecede the first diagnosable activated episode by many years.9,50,51 Therefore, by analogy with the first-episode psychosis approach, focusing the effort in BD on describing the prodrome to first-episode mania would be too little too late and would ignore the characteristic differences in the natural history of BD. That is, we would be focusing too far down the illness course; years after the impact of debilitating melancholic depressive episodes, often associated with a substantial risk of suicide.52,53 Moreover, there is a significant risk of addiction contiguous with the index depressive episodes, worsening the prognosis.54

Other proponents of clinical staging for BD have focused on differentiating earlier- from later-stage illness in adult patients meeting full diagnostic criteria for BD.55–57 However, these studies consider neither the evidence of early antecedent risk syndromes nor the developmental illness trajectory leading up to the full-blown diagnosis of BD, as reported in several large prospective studies of the offspring of parents with BD.51,58–60 Specifically, cross-sectional studies comparing patients with full-threshold BD, subdivided as being in the earlier or later stage of illness based on various definitions of duration, have shown evidence of a progression toward a pro-inflammatory state, increased oxidative stress, and a reduction in neurotrophic factors and neuroplasticity.57,61,62 These biological candidate marker studies have been supported by evidence of a decline in cognitive functioning and an increase in burden of illness effects in cohorts of broadly defined adult patients with BD.49

Kapczinski et al63 have discussed the evidence of neuroprogression in patients with BD in the context of MacEwen’s model of stress-related allostatic load theory of disease.64 Specifically, they have postulated that the genetic diathesis for disease interacts with the burden of illness, including duration of illness, comorbidities (substance use and inflammatory diseases), and perhaps treatment effects to culminate in persistent structural and functional changes in the brain. These neuroanatomical and functional changes are associated with increased treatment refractoriness, worsening morbidity (quality of remission and shortened cycle length), and declining cognition, global functioning, and quality of life. Recently, they proposed to stage patients with BD using quantitative cut-off scores of important clinical variables (global functioning, number of episodes [≤7], age of onset [≤62 years], and time elapsed since first episode [≤128 months]), and associated biochemical markers.55 The problem with this proposal is that it focuses solely on progression of end-stage established BD, rather than developing a staging model based on the full natural history of illness development. It equates to studying full-blown illness, compared with full-blown illness for a longer period, and neglects early risk syndromes.

Largely based on cross-sectional studies of adults with established illness, Conus et al65 have modified a clinical staging model derived from high-risk psychosis research. This model attempts to describe the extent of disease onset and progression starting from well but at identifiable risk (stage 0) through to mild nonspecific symptoms (stage 1), first-episode mania (BD) (stage 2), persistent depressive or manic relapse or recurrences (stage 3), followed by chronic progressive BD (stage 4). While this is a more comprehensive approach than focusing on stages of full-blown (end-stage disorder), the problem with adapting this model to the evidence is several-fold. First, it collapses numerous discrete early clinical stages of illness development, as identified through longitudinal prospective high-risk studies, into a single very heterogeneous stage 1.66 Second, it does not incorporate family history as a way to identify stage 0 high-risk, although a positive family history is the most robust risk factor predicting for at least classical BD67,68; without the context of positive family history, the early stages are too nonspecific and would yield a very high rate of false positives. That is, hypomanic, depressive, and anxiety symptoms are common in adolescent epidemiologic samples and do not predict for BD.69 However, there are specific predictive early risk syndromes in youth with a confirmed family history that should be incorporated.70,71 Third, the first episode of BD is typically a depressive episode, occurring years on average before any diagnosable activated episode.50 Therefore, the evidence strongly suggests that we need to substantially modify the staging model derived from studies in the psychosis field to align with the natural history and consider the heterogeneity of evolving BD.

Clinical Staging: Prospective High-Risk Studies

Given the very high heritability of classical BD, offspring of parents with confirmed illness are an important identifiable and informative high-risk group. During the last 20 years, there have been numerous independent prospective longitudinal studies of offspring of parents with BD assessed during the risk period, providing essential information to inform a clinical staging model of BD.

In a series of publications from our research group, summarizing prospective systematic observations of a cohort of offspring of well-characterized parents with BD, we reported important differences in early childhood antecedents and in the course of mood disorders between high-risk subgroups.50,58,72–74 Specifically, children of parents with BD with an excellent response to long-term lithium (lithium responders) had a completely normal or gifted early developmental course. In contrast, the children of parents who failed to respond to lithium prophylaxis (lithium nonresponders) manifest childhood problems with cognition, emotional regulation, socialization, and neurodevelopmental disorders. Among high-risk offspring who developed major mood disorders, the offspring of lithium responders had an episodic remitting course and responded to lithium prophylaxis, while the offspring of lithium nonresponders had non-fully remitting mood disorders and responded preferentially to either prophylaxis with an anticonvulsant or an atypical antipsychotic.75,76 Moreover, the spectrum of end-stage disorders among the affected offspring of lithium responders was limited to mood disorders, while the offspring of lithium nonresponders manifested both mood and psychotic spectrum illnesses. In both high-risk cohorts, early childhood antecedents predicting the development of mood disorders included anxiety and sleep disorders.66 However, in the offspring of lithium nonresponders, attention deficit, learning disabilities, and cluster A traits were also frequent childhood risk antecedents.77

Findings regarding the evolution of psychopathology from this Canadian longitudinal high-risk study have been replicated in other independent longitudinal high-risk studies.41,60,71 These collective observations were recently distilled into a clinical staging model that was tested using multi-state models.4,54,66 The analysis, based on up to 17 years of prospective clinical research observation, supported that BD develops in a sequence of predictable clinical phases; not all offspring manifest all stages, but once they enter the model they proceed in a forward sequence. The clinical staging model is an aggregate overview, and it should be remembered that not all high-risk offspring follow the model or proceed to end-stage illness.

Preliminary evidence for subtle differences in immunological (pro-inflammatory)78,79 neurotrophic and neuroendocrine markers80,81 have been reported in high-risk offspring, compared with control subjects, and in high-risk offspring in the earlier, compared with the later phases of illness development. These findings lend support for the validity and use of the proposed clinical staging model.82

The early clinical manifestations are nonspecific, in that they are seen in other illness trajectories, including psychotic disorders, internalizing and externalizing disorders, and substance use disorders. They can also be self-limited presentations in some children (not progressing to major psychiatric illness). However, it is the nature of the family history that brings important meaning to these otherwise nonspecific clinical presentations. The history of psychopathology in other family members and their response to specific treatments are important predictive factors aiding in the early differentiation of illness trajectories and in predicting treatment response in help-seeking symptomatic youth. For example, stimulants and antidepressants should either be avoided or, if used, kept to low doses, short duration, and closely monitored in symptomatic youth (attention problems, anxiety, and depressive symptoms) with a confirmed family history of BD.83–86

Other clinical implications pertain to the organization of youth mental health services. That is, it is now clear that psychiatric diagnoses are in flux in young people and cannot be taken as end-stage or stable–static disorders; rather early syndromes should be viewed as potential stops on the way to different-end destinations.84,87–89 Regarding research, this staging model considers heterogeneity of BD, based on the evidence that there may be both overlapping as well as important differences in the pathophysiology, course, treatment response, and prognosis between illness subtypes. Further, the developmentally sensitive phenotypic trajectory of the proposed staging model is well suited to studying markers of illness predisposition and progression, separating the primary disease process from burden of illness effects.82 This model also allows for the testing of interactive hypotheses at critical stages, including the role of early adversity and important mediating or moderating psychosocial and biological (puberty) influences.90–92

An Integrative Staging Model for Bipolar Disorder

As championed by McGorry and colleagues (see McGorry et al3 and McGorry6,93), clinical staging models, describing the development and progression of major psychiatric illnesses, can be very helpful in advancing both clinical practice and research efforts. Clinical staging should advance our ability to identify evolving serious psychiatric illness earlier on, place an individual patient on a continuum of illness development, and advance our search for markers of illness predisposition and progression. These findings will undoubtedly lead to the development of novel, specific treatments targeting earlier stages of illness development that may be more effective, acceptable, and less harmful, compared with later-stage treatments. However, the use of clinical staging for BD will depend on whether it is based on the totality of the evidence. Finally, clinical staging represents an important step toward reducing stigma by legitimizing these illnesses as heritable complex brain diseases and aligning the approach to treatment and research with the way we approach other medical disorders, while always being mindful of the importance to balance early identification against overdiagnosis of normative, transient, or self-resolving emotional symptoms in youth.69,84

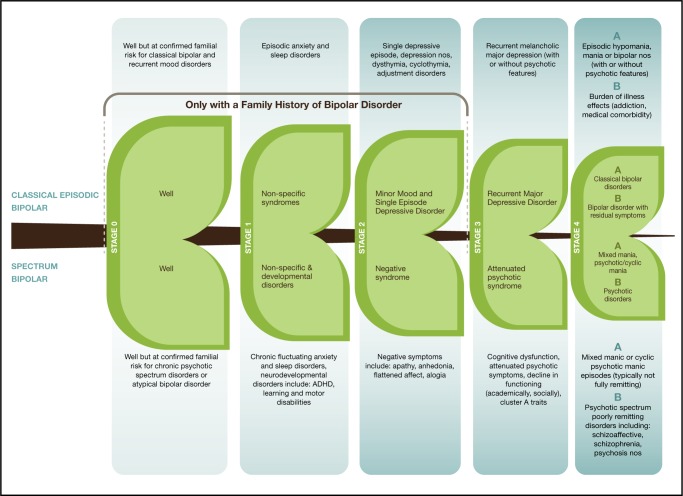

We are at a vital crossroads in our efforts to advance psychiatric research, particularly regarding understanding and recognizing the development of mood disorders. A major leap forward would come through integrating the evidence from various perspectives into a unified comprehensive staging model. Essentially, the proposed integrative model (Figure 1) considers the very high heritability of classical BD, the ability of a confirmed family history to bring context to early, otherwise nonspecific risk syndromes, the replicated evidence that childhood risk syndromes (anxiety and sleep) predict subsequent mood disorders in high-risk youth, that neurodevelopmental disorders predict for more psychotic spectrum disorders, and the overwhelming evidence that BD typically onsets as major depressive disorder years prior to the first-activated episode.

Figure 1.

Integrative clinical staging model for bipolar disorder

ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; nos = not otherwise specified

The limitations of any proposal must be discussed. There are sporadic cases of even the classical form of BD in people with no identified family history.94 However, in the case of classical disorder, this would be the exception rather than the rule. Further, the proposed model would allow for the appropriate level of conservatism when identifying a person as at risk or in the early stages of BD, if the predictive weight of a confirmed family history is not present—that is, in the proposed model, stages 0 to 3 are reserved for people with a confirmed familial risk. Further, the proposed model incorporates evidence from what we know of the early course of classical, familial BD; however, it also applies to those people on the trajectory to psychotic spectrum disorders. In this way, the model would support research focused on predicting the first-activated episode, as well as research focused on understanding the progression of end-stage illness phenotypes (stage 4A to stage 4B).

Conclusion

Adopting a comprehensive evidence-based model of BD would mean that developmental and adult psychiatry researchers would need to collaborate more intensively toward achieving their common and important end goals. This would also necessitate developing new measures that apply across the developmental course from childhood through adolescence and into adulthood. However, it can be argued that to a certain extent expediency and reticence to change (that is, sending out squadrons of trained raters rather than making diagnoses in the context of a comprehensive clinical assessment; maintaining the solitudes between child and adult psychiatry) have prevailed and contributed substantially to the lack of research advancement95—going forward we should abandon approaches that have not paid off and run counter to the evidence.

Even a century later, we can still learn from the wisdom of Kraepelin, who recognized that major psychiatric illnesses were familial brain diseases. Further, he recognized that, despite some overlap, there were fundamental differences between classical mood and psychotic disorders, as evidenced in divergent clinical phases of illness development, prognosis, and family history.96,97 He based hypotheses on careful longitudinal direct observation of patients, incorporating relevant knowledge of other medical diseases available at the time. Let us hope that we move on from here, learning from our own more recent history and from other medical advances, to translate research into important clinical gains for patients and their families.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr Paul Grof and Sarah Doucette for their helpful comments and suggestions that improved this manuscript. I also express sincere thanks to the research families and patients who continue to inspire and inform, and to our dedicated research team and collaborators who embody the spirit of joy through discovery.

Research discussed in this manuscript is funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP 102761).

References

- 1.Cuthbert B, Insel T. The data of diagnosis: new approaches to psychiatric classification. Psychiatry. 2010;73(4):311–314. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2010.73.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGorry PD, Purcell R, Hickie IB, et al. Clinical staging: a heuristic model for psychiatry and youth mental health. Med J Aust. 2007;187(7 Suppl):S40–S42. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGorry PD, Nelson B, Goldstone S, et al. Clinical staging: a heuristic and practical strategy for new research and better health and social outcomes for psychotic and related mood disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(8):486–497. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffy A, Alda M, Hajek T, et al. Early stages in the development of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;121(1–2):127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGorry P. Early clinical phenotypes and risk for serious mental disorders in young people: need for care precedes traditional diagnoses in mood and psychotic disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(1):19–21. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGorry PD. The next stage for diagnosis: validity through utility. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(3):213–215. doi: 10.1002/wps.20080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott J, Leboyer M, Hickie I, et al. Clinical staging in psychiatry: a cross-cutting model of diagnosis with heuristic and practical value. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(4):243–245. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.110858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angst J, Gamma A. Diagnosis and course of affective psychoses: was Kraepelin right? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258(Suppl 2):107–110. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-2013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angst J, Sellaro R. Historical perspectives and natural history of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(6):445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grof P. Sixty years of lithium responders. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):8–16. doi: 10.1159/000314305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Post RM. Sensitization and kindling perspectives for the course of affective illness: toward a new treatment with the anticonvulsant carbamazepine. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1990;23(1):3–17. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oepen G, Baldessarini RJ, Salvatore P, et al. On the periodicity of manic-depressive insanity, by Eliot Slater (1938): translated excerpts and commentary. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grof P, Muller-Oerlinghausen B. A critical appraisal of lithium’s efficacy and effectiveness: the last 60 years. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(Suppl 2):10–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berghofer A, Alda M, Adli M, et al. Long-term effectiveness of lithium in bipolar disorder: a multicenter investigation of patients with typical and atypical features. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1860–1868. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berghofer A, Alda M, Adli M, et al. Stability of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder—long-term follow-up of 346 patients. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2013;1:2–8. doi: 10.1186/2194-7511-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grof P, Duffy A, Cavazzoni P, et al. Is response to prophylactic lithium a familial trait? J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:942–947. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajek T, Cullis J, Novak T, et al. Hippocampal volumes in bipolar disorders: opposing effects of illness burden and lithium treatment. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(3):261–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajek T, Bauer M, Simhandl C, et al. Neuroprotective effect of lithium on hippocampal volumes in bipolar disorder independent of long-term treatment response. Psychol Med. 2014;44(3):507–517. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hajek T, Cullis J, Novak T, et al. Brain structural signature of familial predisposition for bipolar disorder: replicable evidence for involvement of the right inferior frontal gyrus. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(2):144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoll AL, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Shifts in diagnostic frequencies of schizophrenia and major affective disorders at six North American psychiatric hospitals, 1972–1988. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(11):1668–1673. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.11.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grof P, Alda M, Ahrens B. Clinical course of affective disorders: were Emil Kraepelin and Jules Angst wrong? Psychopathology. 1995;28(Suppl 1):73–80. doi: 10.1159/000284960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garnham J, Munro A, Slaney C, et al. Prophylactic treatment response in bipolar disorder: results of a naturalistic observation study. J Affect Disord. 2007;104(1–3):185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alda M. The phenotypic spectra of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grof P, Duffy A, Alda M, et al. Lithium response across generations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(5):378–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duffy A, Grof P. Psychiatric diagnoses in the context of genetic studies of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3(6):270–275. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.30602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Passmore MJ, Garnham J, Duffy A, et al. Phenotypic spectra of bipolar disorder in responders to lithium versus lamotrigine. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5(2):110–114. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grof P, Alda M, Grof E, et al. Lithium response and genetics of affective disorders. J Affect Disord. 1994;32(2):85–95. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruger S, Alda M, Young LT, et al. Risk and resilience markers in bipolar disorder: brain responses to emotional challenge in bipolar patients and their healthy siblings. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):257–264. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turecki G, Grof P, Grof E, et al. Mapping susceptibility genes for bipolar disorder: a pharmacogenetic approach based on excellent response to lithium. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6(5):570–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conus P, Macneil C, McGorry PD. Public health significance of bipolar disorder: implications for early intervention and prevention. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(5):548–556. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiltink S, Velthorst E, Nelson B, et al. Declining transition rates to psychosis: the contribution of potential changes in referral pathways to an ultra-high-risk service. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013 Nov 14; doi: 10.1111/eip.12105. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson B, Yuen HP, Wood SJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of a group at ultra high risk (“prodromal”) for psychosis: the PACE 400 study. JAMA. 2013;70(8):793–802. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bora E, Lin A, Wood SJ, et al. Cognitive deficits in youth with familial and clinical high risk to psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/acps.12261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fusar-Poli P, Yung AR, McGorry P, et al. Lessons learned from the psychosis high-risk state: towards a general staging model of prodromal intervention. Psychol Med. 2014;44(1):17–24. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hickie IB, Scott J, McGorry PD. Clinical staging for mental disorders: a new development in diagnostic practice in mental health. Med J Aust. 2013;198(9):461–462. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cannon M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, et al. Evidence for early-childhood, pan-developmental impairment specific to schizophreniform disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(5):449–456. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.5.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray RM, Sham P, Van Os J, et al. A developmental model for similarities and dissimilarities between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2004;71(2–3):405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacCabe JH, Murray RM. Intellectual functioning in schizophrenia: a marker of neurodevelopmental damage? J Intellect Disabil Res. 2004;48(Pt 6):519–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, et al. Etiological and clinical features of childhood psychotic symptoms: results from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):328–338. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke MC, Kelleher I, Clancy M, et al. Predicting risk and the emergence of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(3):585–612. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2–3):131–142. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacCabe JH, Lambe MP, Cnattingius S, et al. Excellent school performance at age 16 and risk of adult bipolar disorder: national cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(2):109–115. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.060368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rice J, Reich T, Andreasen NC, et al. The familial transmission of bipolar illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(5):441–447. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800170063009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farmer A, Elkin A, McGuffin P. The genetics of bipolar affective disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(1):8–12. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280117722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell PB. Bipolar disorder: the shift to overdiagnosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(11):659–665. doi: 10.1177/070674371205701103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maziade M, Gingras N, Rouleau N, et al. Clinical diagnoses in young offspring from eastern Quebec multigenerational families densely affected by schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(2):118–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maziade M, Rouleau N, Cellard C, et al. Young offspring at genetic risk of adult psychoses: the form of the trajectory of IQ or memory may orient to the right dysfunction at the right time. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e19153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berk M, Berk L, Dodd S, et al. Stage managing bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(5):471–477. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duffy A, Alda M, Hajek T, et al. Early course of bipolar disorder in high-risk offspring: prospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(5):457–458. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.062810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mesman E, Nolen WA, Reichart CG, et al. The Dutch bipolar offspring study: 12-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(5):542–549. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baethge C, Cassidy F. Fighting on the side of life: a special issue on suicide in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(5):453–456. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGuffin P, Perroud N, Uher R, et al. The genetics of affective disorder and suicide. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(5):275–277. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duffy A, Horrocks J, Milin R, et al. Adolescent substance use disorder during the early stages of bipolar disorder: a prospective high-risk study. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(1–3):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grande I, Magalhaes PV, Chendo I, et al. Staging bipolar disorder: clinical, biochemical, and functional correlates. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129(6):437–444. doi: 10.1111/acps.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kapczinski F, Dias VV, Kauer-Sant’Anna M, et al. Clinical implications of a staging model for bipolar disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(7):957–966. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kauer-Sant’Anna M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and inflammatory markers in patients with early- vs late-stage bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(4):447–458. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duffy A. The early natural history of bipolar disorder: what we have learned from longitudinal high-risk research. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(8):477–485. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.DelBello MP, Geller B. Review of studies of child and adolescent offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3(6):325–334. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.30607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shaw JA, Egeland JA, Endicott J, et al. A 10-year prospective study of prodromal patterns for bipolar disorder among Amish youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:1104–1111. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000177052.26476.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frey BN, Andreazza AC, Houenou J, et al. Biomarkers in bipolar disorder: a positional paper from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Biomarkers Task Force. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47(4):321–332. doi: 10.1177/0004867413478217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):804–817. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kapczinski F, Vieta E, Andreazza AC, et al. Allostatic load in bipolar disorder: implications for pathophysiology and treatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(4):675–692. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vieta E, Popovic D, Rosa AR, et al. The clinical implications of cognitive impairment and allostatic load in bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Conus P, Berk M, McGorry PD. Pharmacological treatment in the early phase of bipolar disorders: what stage are we at? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(3):199–207. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duffy A, Horrocks J, Doucette S, et al. The developmental trajectory of bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:122–128. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.126706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gottesman II, Laursen TM, Bertelsen A, et al. Severe mental disorders in offspring with 2 psychiatrically ill parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):252–257. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bienvenu OJ, Davydow DS, Kendler KS. Psychiatric ‘diseases’ versus behavioral disorders and degree of genetic influence. Psychol Med. 2011;41(1):33–40. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000084X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tijssen MJ, van Os J, Wittchen HU, et al. Evidence that bipolar disorder is the poor outcome fraction of a common developmental phenotype: an 8-year cohort study in young people. Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):289–299. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709006138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duffy A, Horrocks J, Doucette S, et al. Childhood anxiety: an early predictor of mood disorders in offspring of bipolar parents. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nurnberger JI, Jr, McInnis M, Reich W, et al. A high-risk study of bipolar disorder. Childhood clinical phenotypes as precursors of major mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1012–1020. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duffy A, Alda M, Kutcher S, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and syndromes among adolescent children of parents with lithium-responsive or lithium-nonresponsive bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:431–433. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Duffy A, Alda M, Kutcher S, et al. A prospective study of the offspring of bipolar parents responsive and nonresponsive to lithium treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1171–1178. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Duffy A, Alda M, Crawford L, et al. The early manifestations of bipolar disorder: a longitudinal prospective study of the offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(8):828–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Duffy A, Alda M, Milin R, et al. A consecutive series of treated affected offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: is response associated with the clinical profile? Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(6):369–376. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duffy A, Milin R, Grof P. Maintenance treatment of adolescent bipolar disorder: open study of the effectiveness and tolerability of quetiapine. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Duffy A. The nature of the association between childhood ADHD and the development of bipolar disorder: a review of prospective high-risk studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1247–1255. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11111725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Padmos RC, Hillegers MH, Knijff EM, et al. A discriminating messenger RNA signature for bipolar disorder formed by an aberrant expression of inflammatory genes in monocytes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(4):395–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Duffy A, Horrocks J, Doucette S, et al. Immunological and neurotrophic markers of risk status and illness development in high-risk youth: understanding the neurological underpinnings of bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2014;2(4):2–9. doi: 10.1186/2194-7511-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deshauer D, Duffy A, Meaney M, et al. Salivary cortisol secretion in remitted bipolar patients and offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(4):345–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ellenbogen MA, Hodgins S, Linnen AM, et al. Elevated daytime cortisol levels: a biomarker of subsequent major affective disorder? J Affect Disord. 2011;132(1–2):265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Duffy A, Lewitzka U, Doucette S, et al. Biological indicators of illness risk in offspring of bipolar parents: targeting the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and immune system. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6(2):128–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Duffy A. Interventions for youth at risk of bipolar disorder [Internet] Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):37–47. doi: 10.1007/S40501-013-0006-x. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40501-013-0006-x#page-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duffy A, Carlson GA. How does a developmental perspective inform us about the early natural history of bipolar disorder? J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22(1):6–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reichart CG, Nolen WA. Earlier onset of bipolar disorder in children by antidepressants or stimulants? An hypothesis. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(1):81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.DelBello MP, Soutullo CA, Hendricks W, et al. Prior stimulant treatment in adolescents with bipolar disorder: association with age at onset. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3(2):53–57. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ruggero CJ, Kotov R, Carlson GA, et al. Diagnostic consistency of major depression with psychosis across 10 years. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1207–1213. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carlson GA. Diagnostic stability and bipolar disorder in youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(12):1202–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bromet EJ, Kotov R, Fochtmann LJ, et al. Diagnostic shifts during the decade following first admission for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(11):1186–1194. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Doucette S, Horrocks J, Grof P, et al. Attachment and temperament profiles among the offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kendler K. “A gene for . . .”: The nature of gene action in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1243–1252. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Doucette S, Levy A, Flowerdew G, et al. Early parent-child relationships and risk of mood disorder in a Canadian sample of offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder: findings from a 16-year prospective cohort study. Early Interv Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/eip.12195. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McGorry PD. Early clinical phenotypes, clinical staging, and strategic biomarker research: building blocks for personalized psychiatry. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):394–395. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Duffy A, Grof P, Robertson C, et al. The implications of genetics studies of major mood disorders for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(9):630–637. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Duffy A, Doucette S, Lewitzka U, et al. Findings from bipolar offspring studies: methodology matters. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5(3):181–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Trede K, Salvatore P, Baethge C, et al. Manic-depressive illness: evolution in Kraepelin’s textbook, 1883–1926. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13(3):155–178. doi: 10.1080/10673220500174833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kendler KS. Kraepelin and the differential diagnosis of dementia praecox and manic-depressive insanity. Compr Psychiatry. 1986;27(6):549–558. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(86)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]