Abstract

In this study, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) monotherapy with combination therapies utilizing UDCA and budesonide was performed. We found that combination therapy with UDCA and budesonide was more effective than UDCA monotherapy for primary biliary cirrhosis–autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome. Moreover, compared to prednisone, budesonide has fewer side effects.

Keywords: meta-analysis, UDCA, budesonide, combination therapy, PBC–AIH overlap syndrome

Introduction

Autoimmune liver disease (ALD) is a group of diseases of unknown etiology, and is immune-mediated, including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis.1 Some patients display the characteristics of two diseases based on clinical, biochemical, immunological, or histological features, at different stages during the course of their disease. This is called ‘overlap syndrome’, among which primary biliary cirrhosis–autoimmune hepatitis (PBC–AIH) is the most common.2 However, because of its low incidence and the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria, the exact pathogenesis of PBC–AIH remains unclear. The incidence of PBC–AIH is reported to be between 2% and 20%, based on different diagnostic criteria.3–5 Because there have been few mechanized large-scale randomized double-blinded controlled clinical trials or prospective controlled studies of PBC–AIH, progress in the treatment of this disease has been relatively slow. Budesonide has had positive effects on AIH6 and ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) effectively improves PBC-associated cholestasis, prolonging survival and delaying histologic progression.7,8 In some studies of PBC–AIH, the results of combination therapy utilizing UDCA and budesonide were encouraging;9–10 however, there have been few local studies.11 Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis to explore the efficacy and safety of UDCA combined with budesonide therapy for PBC–AIH, hoping to provide strong supporting evidence for the use of this treatment in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Determining research standards

Study objective

PBC–AIH was strictly defined as the association of PBC and AIH. The presence of at least two of the three accepted criteria was required for the diagnosis of each disease.12 The criteria for PBC were: 1) alkaline phosphatase (AP) levels at least two times higher than the upper limit of normal (ULN) or γ-glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT) levels at least five times higher than the ULN; 2) a positive test for anti-mitochondrial antibodies; and 3) a liver biopsy specimen showing florid bile duct lesions. The criteria for AIH were: 1) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels at least five times higher than the ULN; 2) serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels at least two times higher than the ULN or a positive test for anti-smooth muscle antibodies; and 3) a liver biopsy showing moderate or severe periportal or periseptal piecemeal lymphocytic necrosis. Other liver diseases were excluded, including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcoholic cirrhosis, cryptogenic cirrhosis, and primary biliary sclerosis.

Inclusion criteria

1) A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of UDCA monotherapy and UDCA combined with budesonide, whether or not it was blinded in design, and any type of publication; 2) the diagnostic criteria for PBC–AIH in the study met those in the literature; 3) the establishment of a parallel-designed RCT; 4) none of the test subjects received prior treatment with other drugs; and 5) UDCA and budesonide dose ranges were not limited.

Exclusion criteria

1) Any uncontrolled trials, non-RCTs, and quasi-RCTs; 2) RCTs of UDCA combined with any other drugs; 3) RCTs of UDCA versus placebo; and 4) animal experiments and studies of cells or tissues.

Study criteria

The relevant studies were identified and selected by searching the PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Science Citation Index (updated to July 2014) databases13 with the search terms ‘ursodeoxycholic acid’, ‘budesonide’, ‘combination therapy’, ‘PBC–AIH’, ‘overlap syndrome’, ‘randomized controlled trial’, and ‘meta-analysis’. We also performed a full manual search of all review articles and retrieved original studies and abstracts.

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted from each study by two researchers (Huawei Zhang and Jing Yang) and any disagreement was resolved by consensus. The following data were extracted from each article: first author name, publication year, number of patients, daily dose of oral therapy, duration of treatment, method used to deal with missing data, liver biochemistry (AP, ALT, aspartate aminotransferase, GGT, IgG, IgM), symptoms, liver histology, death, liver transplantation, death and/or transplantation, and adverse events.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis was scored with the Jadad composite scale (Table 1).14,15 This is a five-point quality scale, with low-quality studies having a score of ≤2 and high-quality studies a score of ≥3. Methodological quality was independently assessed by two study authors. Each study was given an overall quality score based on the criteria described above, which was then used to rank the studies. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Table 1.

Criteria used to grade the quality of randomized controlled trials: the Jadad scores

| Each study was given 1 point for each ‘yes’ and 0 points for each ‘no’ in response to each of the following questions |

|---|

| 1) Was the study described as randomized using the words ‘randomly’, ‘random’, or ‘randomization’? |

| a) An additional point was given if the method of randomization was described and was appropriate (eg, table of random numbers, computer-generated). |

| b) A point was deducted if the method of randomization was inappropriate (eg, patients allocated alternately, by birth date, or by hospital number). |

| 2) Was the study described as ‘double blinded’? |

| a) A point was given if the method of blinding was described and it was appropriate (eg, identical placebo). |

| b) An additional point was deducted if the method of blinding was inappropriate (eg, comparing placebo tablet with injection). |

| 3) Was there a description of the patients who withdrew or dropped out? |

Note: The maximum number of points was 5.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed with RevMan software (v5.2; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). The odds ratio (OR) for each clinical event was presented with its 95% confidence interval (CI). We tested heterogeneity using the χ2 test and the I2 test; a P-value <0.10 or an I2 value >50% was considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity. A fixed-effects model was used when the heterogeneity test had a P-value >0.10 or an I2 value <50%; otherwise, a random-effects model was used. We also constructed funnel plots to evaluate the presence of publication bias.

Results

Descriptive and qualitative assessments

After we excluded reviews, case reports, repeated studies, and research whose purpose was unrelated to the evaluation system or inconsistent with the literature, we finally selected eight RCTs from 1,578 studies.16–23 These studies involved 214 patients: 97 were randomized to the UDCA monotherapy groups and 117 to the combination therapy (UDCA and budesonide) groups. The mean age of patients ranged from 41–54 years and the mean follow-up periods ranged from 10–90 months. The daily dose of UDCA ranged from 10–15 mg/kg, and the daily dose of budesonide was 6 mg/day. The baseline characteristics of the eight trials are listed in Table 2. The descriptive results are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the trials included in the meta-analysis

| Authors | Mean age (years) | Monotherapy (n) | Combination therapy (n) | UDCA dose (mg/kg/day) | Budesonide dose (mg/kg/day) | Duration of treatment (months) | Publication type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chazouillères et al16 | 50 | 5 | 6 | 13–15 | 0.5 | 23 | Full text |

| Gunsar et al17 | 44 | 13 | 7 | 13 | 0.5 | 28 | Full text |

| Chazouillères et al18 | 41 | 11 | 6 | 13–15 | 0.5 | 90 | Full text |

| Heurgué et al19 | 44 | 9 | 4 | 11–14.7 | 0.5–1 | 60 | Full text |

| Ozaslan et al20 | 44 | 3 | 9 | 13–15 | 0.5 | 31 | Full text |

| Tanaka et al21 | 54 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 0.5 | 73 | Full text |

| Zhu et al22 | 50 | 11 | 8 | 13–15 | 0.5–1 | 10 | Full text |

| Ozaslan et al23 | 48 | 30 | 67 | 13–15 | 30–60 (mg/day) | 66 | Full text |

Abbreviation: UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

Table 3.

Study or subgroup: the selected eight RCTs

| Authors | Symptoms improved

|

Liver biochemistry improved

|

Histology progression

|

Death

|

Death or liver transplantation

|

Adverse events

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UDCA* | COM# | UDCA* | COM# | UDCA* | COM# | UDCA* | COM# | UDCA* | COM# | UDCA* | COM# | |

| Chazouillères et al16 | 2/5 | 3/6 | 2/5 | 6/6 | 3/5 | 0/2 | 1/5 | 0/6 | 1/5 | 0/6 | 1/5 | 2/6 |

| Gunsar et al17 | 1/16 | 0/7 | 8/16 | 7/7 | 5/8 | 1/7 | 0/16 | 1/7 | 0/16 | 1/7 | 1/16 | 0/7 |

| Chazouillères et al18 | 3/11 | 0/6 | 4/11 | 6/6 | 4/8 | 0/4 | NR | NR | 0/11 | 1/6 | NR | NR |

| Heurgué et al19 | 1/6 | 1/4 | 3/6 | 3/4 | 3/6 | 1/4 | NR | NR | 0/6 | 0/4 | NR | NR |

| Ozaslan et al20 | 3/3 | 3/9 | 3/3 | 3/9 | 0/3 | 6/9 | 0/3 | 2/9 | 0/3 | 3/9 | NR | NR |

| Tanaka et al21 | 3/15 | 1/10 | 8/15 | 10/10 | 7/15 | 0/10 | 0/15 | 1/10 | 0/15 | 1/10 | NR | NR |

| Zhu et al22 | 0/11 | 0/8 | 6/11 | 8/8 | 3/3 | 0/3 | NR | NR | 0/11 | 0/8 | 2/11 | 1/8 |

| Ozaslan et al23 | 0/30 | 0/67 | 19/30 | 56/67 | 18/23 | 12/14 | 0/30 | 5/67 | 0/30 | 9/67 | NR | NR |

Notes:

monotherapy with UDCA

combination therapy with UDCA and budesonide.

Abbreviations: COM, combination; NR, not reported; RCT, randomized controlled trial; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

Quality assessment of the studies included

Methodological quality scores ranged from 3–5 (Table 4). Six of the eight randomized studies adequately described the way in which they were randomized. All studies used a double-blinded method, and five provided specific descriptions of the blinding used. Six studies described withdrawals and lost cases. Three studies described allocation concealment, whereas five had no such description. Overall, the Jadad scores of all the RCTs were ≥3 points, and were thus considered high-quality research.

Table 4.

Jada quality scores for the trials included in the meta-analysis

Meta-analysis

Pruritus and jaundice

Eight trials16–23 including 214 patients reported data regarding the endpoints of pruritus and jaundice. Symptoms improved in 13 of 97 patients in the monotherapy groups and in eight of 117 patients in the combination therapy groups. There was no significant heterogeneity (P=0.68, I2=0%) and no significant differences between groups (OR: 2.12, 95% CI: 0.72–6.18, P=0.17; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of monotherapy versus combination therapy on pruritus and jaundice in patients with PBC–AIH overlap syndrome.

Notes: *monotherapy with UDCA; #combination therapy with UDCA and budesonide.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COM, combination; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel test; NR, not reported; PBC-AIH, primary biliary cirrhosis–autoimmune hepatitis; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

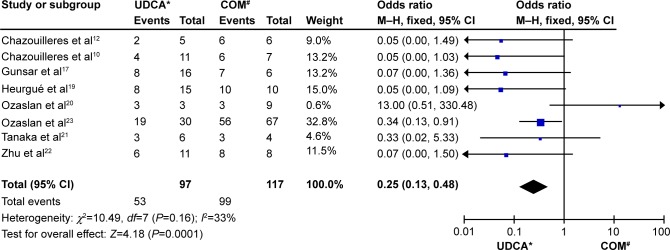

ALT and AP levels

Eight trials including 214 patients reported data regarding the endpoints of ALT and AP levels. Symptoms improved in 53 of 97 patients in the monotherapy groups and in 99 of 117 patients in the combination therapy groups. There was no significant heterogeneity (P=0.16, I2=33%) but there were significant differences between the groups (OR: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.13–0.48, P<0.0001; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Biochemical parameters of patients treated with monotherapy versus combination therapy for PBC–AIH overlap syndrome.

Notes: *monotherapy with UDCA; #combination therapy with UDCA and budesonide.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COM, combination; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel test; NR, not reported; PBC-AIH, primary biliary cirrhosis–autoimmune hepatitis; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

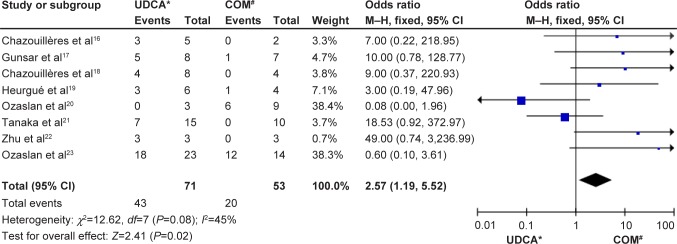

Histologic progression

Of the 214 patients (eight trials) who underwent second biopsies, the histology declined in 43 of 71 patients in the monotherapy groups and in 20 of 53 patients in the combination therapy groups. There was no significant heterogeneity (P=0.08, I2=45%) but there were significant differences between the groups (OR: 2.57, 95% CI: 1.19–5.52, P=0.02; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Histological progression in patients treated with monotherapy or combination therapy for PBC–AIH overlap syndrome.

Notes: *monotherapy with UDCA; #combination therapy with UDCA and budesonide.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COM, combination; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel test; NR, not reported; PBC-AIH, primary biliary cirrhosis–autoimmune hepatitis; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

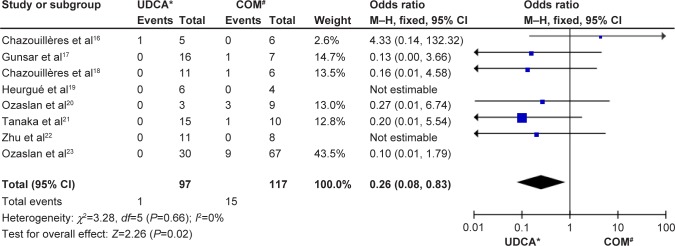

Death or liver transplantation

Eight trials including 214 patients reported data for the endpoint of death or liver transplantation. Death or liver transplantation occurred in one of 97 patients in the monotherapy groups and in 15 of 117 patients in the combination therapy groups. There was no significant heterogeneity (P=0.66, I2=0%) but there were significant differences between the groups (OR: 0.26, 95% CI: 0.08–0.83, P=0.02; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Death or liver transplantation in patients treated with monotherapy versus combination therapy for PBC–AIH overlap syndrome.

Notes: *monotherapy with UDCA; #combination therapy with UDCA and budesonide.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COM, combination; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel test; NR, not reported; PBC-AIH, primary biliary cirrhosis–autoimmune hepatitis; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

Adverse events

Three trials including 53 patients reported data regarding the endpoint of adverse events. Adverse events were recorded in four of 32 patients in the monotherapy groups and in three of 21 patients in the combination therapy groups. There was no significant heterogeneity (P=0.82, I2=0%) and there were no significant differences between the groups (OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.21–5.01, P=0.97; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Adverse events in patients treated with monotherapy versus combination therapy for PBC–AIH overlap syndrome.

Notes: *monotherapy with UDCA; #combination therapy with UDCA and budesonide.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COM, combination; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel test; NR, not reported; PBC-AIH, primary biliary cirrhosis–autoimmune hepatitis; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

Sensitivity analysis

Jadad scores were used in this study to assess research quality. All eight studies had scores of ≥3 points, and were thus considered high-quality research. Therefore, there was no need for further sensitivity analysis.

Publication bias

Figure 6 shows the funnel plots of the meta-analysis. The funnel plots for clinical events show slight asymmetry, suggesting possible publication bias (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Funnel plots of the meta-analysis.

Notes: (A) Symptoms of fatigue and jaundice. (B) Liver biochemical parameters (ALT and AP). (C) Histopathological assessment. (D) Death or liver transplantation. (E) Adverse events.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AP, alkaline phosphatase; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard of error.

Discussion

In ALD, AIH is treated with corticosteroids, commonly with prednisone or prednisolone. In some nonresponders, the dose may be adjusted or the following drugs may be used as optional replacement therapy: cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, budesonide, among others.24,25 Budesonide is a nonhalogenated glucocorticoid absorbed in the small intestine. Ninety percent of the oral dose is metabolized during the first pass effect in healthy individuals. After hepatic uptake, budesonide is metabolized to two major metabolites: 16-hydroxy-prednisolone and 6-hydroxy-budesonide. Compared with prednisolone, the glucocorticoid receptor–binding activity of budesonide is 15–20 times higher; but as such, the risk of fractures and bleeding are significantly lower than with prednisolone. The treatment for PBC is UDCA, which not only improves cholestasis, but also significantly reduces transaminase levels.26 UDCA is also commonly used to treat patients with AIH. Because overlap syndrome displays characteristics of both AIH and PBC, most patients tend to receive combination therapy, which appears to induce better biochemical and histologic responses in patients with this disease.

We showed that combination therapy did not differ significantly from monotherapy in improving fatigue, jaundice, mortality, death or the need for liver transplantation, or adverse events, but was significantly superior to monotherapy in reducing serum AP, ALT, and other biochemical liver markers. The literature evaluated was biased because too few studies were included, so more high-quality studies are required to confirm the conclusions drawn here. Three of the included RCTs reported adverse events, whereas the other five did not. From the perspective of drug safety, the differences in the rates of adverse events between combination therapy and monotherapy were insignificant. It has been suggested that combination therapy is a relatively safe treatment. In clinical trials, treatment efficacy and adverse reactions should be given equal value.

In summary, we recommend that patients diagnosed with overlap syndrome undergo early treatment that combines UDCA with corticosteroids; budesonide used to be the first choice. This therapy is effective for these patients and can improve their liver biochemical profile. Although combination therapy is relatively safe, adverse effects should be closely monitored when the recommended dose is used. Compared to prednisolone, budesonide is safer, although the risk of portal vein thrombosis remains a concern.27 Cheng et al28 report that H2S attenuates concanavalin-A–induced acute hepatitis by inhibiting apoptosis and autophagy, but its exact mechanism is still unclear, and the guiding value for clinical is also limited. PBC–AIH patients require efficient and safe treatment regimens.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81270515), the Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau Foundation (grant numbers 2011287, 2012107), and the Chinese Foundation for Hepatitis Prevention and Control (grant numbers WBN20100021, CFHPC20131011).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- 1.Czaja AJ. Frequency and nature of the variant syndromes of autoimmune liver disease. Hepatology. 1998;28(2):360–365. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rust C, Beuers U. Overlap syndromes among autoimmune liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(21):3368–3373. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshl S, Cauch-Dudek K, Wanless IR, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis with additional features of autoimmune hepatitis: response to therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid. Hepatology. 2002;35(2):409–413. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talwalkar JA, Keach JC, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Overlap of autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: an evaluation of a modified scoring system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(5):1191–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuhauser M, Bjornsson E, Treeprasertsuk S, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis-PBC overlap syndrome: a simplified scoring system may assist in the diagnosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(2):345–353. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csepregi A, Röcken C, Treiber G, Malfertheiner P. Budesonide induces complete remission in autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(9):1362–1366. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i9.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakker GJ, Haan YC, Maillette de Buy Wenniger LJ, Beuers U. Sarcoidosis of the liver: to treat or not to treat? Neth J Med. 2012;70(8):349–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delgado JS, Vodonos A, Delgado B, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis in Southern Israel: a 20 year follow up study. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(8):e193–e198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muratori P, Granito A, Pappas G, et al. The serological profile of the autoimmune hepatitis/primary biliary cirrhosis overlap syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1420–1425. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Efe C, Ozaslan E, Purnak T, et al. Liver fibrosis may reduce the efficacy of budesonide in the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis and overlap syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11(5):330–334. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu CH, Wang QH, Tian GS, Xu XY, Yu YY, Wang GQ. Clinical features of the overlap syndrome of autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: retrospective study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2006;119(3):238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2009;51(2):237–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu D, Wu SM, Lu J, Zhou YQ, Xu L, Guo CY. Rifaximin versus nonabsorbable disaccharides for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:236963. doi: 10.1155/2013/236963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodologic quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(11):982–989. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chazouillères O, Wendum D, Serfaty L, Montembault S, Rosmorduc O, Poupon R. Primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome: clinical features and response to therapy. Hepatology. 1998;28(2):296–301. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunsar F, Akarca US, Ersöz G, Karasu Z, Yüce G, Batur Y. Clinical and biochemical features and therapy responses in primary biliary cirrhosis and primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49(47):1195–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chazouillères O, Wendum D, Serfaty L, Rosmorduc O, Poupon R. Long term outcome and response to therapy of primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome. J Hepatol. 2006;44(2):400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heurgué A, Vitry F, Diebold MD, et al. Overlap syndrome of primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis: a retrospective study of 115 cases of autoimmune liver disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2007;31(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(07)89323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozaslan E, Efe C, Akbulut S, et al. Therapy response and outcome of overlap syndromes: autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis compared to autoimmune hepatitis and autoimmune cholangitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57(99–100):441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka A, Harada K, Ebinuma H, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis – autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome: a rationale for corticosteroids use based on a nation-wide retrospective study in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2011;41(9):877–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu JY, Shi YQ, Han ZY, et al. Observation on therapeutic alliance with UDCA and glucocorticoids in AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2011;19(5):334–339. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2011.05.006. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozaslan E, Efe C, Heurgué-Berlot A, et al. Factors associated with response to therapy and outcome of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis with features of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):863–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, et al. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(6):2193–2213. doi: 10.1002/hep.23584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luxon BA. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Gastro-enterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(2):461–478. vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poupon R, Poupon RE. Treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;14(4):615–628. doi: 10.1053/bega.2000.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yokokawa J, Saito H, Kanno Y, et al. Overlap of primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis: characteristics, therapy, and long term outcomes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(2):376–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng P, Chen K, Xia Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide, a potential novel drug, attenuates concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:1277–1286. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S66573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]