SUMMARY

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) regulate critical events during development. In complex tissues, such as the mammalian central nervous system (CNS), networks likely provide the complex regulatory interactions needed to direct the specification of the many CNS cell types. Here we dissect a GRN that regulates a binary fate decision between two siblings in the murine retina, the rod photoreceptor and bipolar interneuron. The GRN centers on Blimp1, one of the transcription factors (TFs) that regulates the rod versus bipolar cell fate decision. We identified a cis-regulatory module (CRM), B108, which mimics Blimp1 expression. Deletion of genomic B108 by CRISPR/Cas9 in vivo using electroporation abolished the function of Blimp1. Otx2 and RORβ were found to regulate Blimp1 expression via B108, and Blimp1 and Otx2 were shown to form a negative feedback loop that regulates the level of Otx2, which regulates the production of the correct ratio of rods and bipolar cells.

INTRODUCTION

Many studies have been carried out wherein individual genes are manipulated, and their effects on cell types characterized. In most instances, these are transcription factors or elements of a signaling pathway (Afelik and Jensen, 2013; Lee and Pfaff, 2001; Nakajima, 2011). The expression patterns of many of these genes, and their effects, are often spread across many cell types. Nevertheless, they are able to play specific roles in different times and places. The consensus is that specific outcomes are due to different contexts in different cells (Kamachi and Kondoh, 2013). Chromatin structure, microRNAs, and other transcripts and proteins undoubtedly create such contexts. However, studies that define a particular context are difficult, and, for the most part, have not been carried out. To dissect such complexities, it is useful to have a system where one can manipulate gene expression, ideally in vivo. In addition, a system in which one can readily discover the cis-regulatory sequences required for gene regulation is advantageous. The murine retina offers such a system (Kim et al., 2008a; Matsuda and Cepko, 2004, 2007). We have exploited this system to address a binary fate decision in the mammalian retina.

The retina is a highly evolved sense organ, which uses photoreceptors to capture light and create neural signals that are transmitted to other retinal neurons. Parallel processing of these visual signals is carried out by more than 60 retinal cell types to extract selected features from the visual scene (Masland and Raviola, 2000; Meister, 1996). There are a large number of inherited diseases of the retina, with most due to dysfunction and loss of photoreceptor cells (Boucherie et al., 2011). An understanding of the specification of retinal neurons can greatly inform the development of therapies to treat such diseases, e.g. the production of photoreceptor cells from stem cells (Ong and da Cruz, 2012).

During retinal development, retinal cell types are specified from a pool of multipotent retinal progenitor cells (RPCs) in a temporal order (Livesey and Cepko, 2001). RPCs can produce two very different cell types in a terminal division. One such division produces a rod photoreceptor cell and an interneuron, the bipolar cell (Turner and Cepko, 1987). There have been several studies that have identified TFs that impact these two fates (Brzezinski et al., 2010; Jia et al., 2009; Katoh et al., 2010; Koike et al., 2007; Ohsawa and Kageyama, 2008; Sato et al., 2007). Many of these genes impact more retinal cell types than just the rods and bipolar cells. We wished to understand the GRN operating within the RPCs and their newly postmitotic progeny at the time when this rod versus bipolar cell binary decision is being made. Binary cell fate decisions have been well studied in invertebrates, and in vertebrate haematopoiesis (Graf and Enver, 2009; Jukam and Desplan, 2010). However, in the mammalian CNS, including the retina, the TFs that control cell fate decisions have been mainly studied by gain and loss of function manipulations of individual TFs. The participation of TFs within a GRN, and the cis-regulatory modules (CRMs) that they utilize, have not been systematically addressed. Here we have identified interactions of key TFs that regulate the final ratio of rods versus bipolar cells within the rod-bipolar GRN, based on the identification of a new CRM for Blimp1, a gene that is important in this GRN. We also used in vivo electroporation to interrogate the necessity of this CRM, after first testing CRISPR/Cas9 (Cong et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013; Sternberg et al., 2014) in a reporter strain of mice to determine the effectiveness of this new method to create genomic alterations in tissues. We found that CRISPR/Cas9 created homozygous and heterozygous alterations in >50% of the electroporated retinal cells. This method was then employed for deletion of the Blimp1 CRM, where it led to the loss of Blimp1 function. Together, all of these experiments led to the identification of the GRN that regulates the rod vs. the bipolar fate. The GRN regulates the level of Otx2, a gene that is required for the production of both rods and bipolar cells, whose level determines whether a cell becomes a rod or a bipolar cell.

RESULTS

Identification of retinal enhancers of Blimp1 gene

Blimp1, a zinc finger transcription factor (also known as Prdm1), has been shown to be required for the production of the proper ratio of rods and bipolar cells, as its loss leads to an increase in bipolar cells and a reduction in rods (Brzezinski et al., 2010; Brzezinski et al., 2013; Katoh et al., 2010). As the first step in the dissection of the rod-bipolar GRN, we sought to identify the critical CRMs that control Blimp1 expression in the retina. DNA fragments upstream of the Blimp1 transcription start site (TSS) were tested for their ability to activate expression of reporter genes in developing mouse retinas, using electroporation into retinal explants. A ~12kb mouse genomic fragment (B12kb) was able to drive expression in retinas, and thus a series of deletions were tested to determine the minimal sequence for this activity (Figure 1). A 108bp fragment (B108) was found to be sufficient to drive reporter expression in retinas (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 1). B108 was also necessary for the activity of B12kb, as deletion of this fragment dramatically reduced EGFP expression driven by B12kb (Figure 2A-D).

Figure 1. Identification of enhancers for the Blimp1 gene.

(A) The Blimp1 locus viewed by the ECR Browser Program. The mouse reference genomic sequence is aligned with that of other species. The transcript of mouse Blimp1 gene is shown on the top. Blue: coding sequences; Yellow: untranslated regions; Red: conserved regions upstream of Blimp1; Light brown: introns. (B) A ~12kb fragment (B12kb) upstream of the Blimp1 gene and a variety of deletion variants were inserted upstream of the EGFP gene in a reporter plasmid and electroporated into mouse retinas, with assessment of EGFP levels indicated on the left. A 1kb fragment (Chr10: 44464199-44465247; GRCm38/mm10) is critical for activity. (C) A series of truncations of the 1kb fragment were generated based on sequence conservation. These fragments were cloned into the Stagia3 reporter plasmid individually and tested for activity, as summarized on the left. See also Figure S1.

Figure 2. Characterization of the B108 enhancer in mouse retinas.

(A) Schematics of reporter plasmids. The B108 and B12kb fragment were used to drive EGFP expression. In B12kbD-EGFP plasmid, B108 was deleted from B12k. (B) The constructs shown in panel A were individually electroporated into the P0 retinas in vivo with the CAG-LacZ plasmid as an electroporation efficiency control. Tissue was examined at P3. For detailed procedures, please see Article+ supplementary file. (C) Electroporated retinas were stained with anti-βgal (blue, label all electroporated cells), anti-GFP (green) and anti-Blimp1 (red) antibodies. (D) The percentage of Blimp1+GFP+LacZ+ retinal cells was calculated over different retinal cell populations. Blimp1+GFP+LacZ+: electroporated retinal cells that turned on reporter EGFP and expressed Blimp1 protein. GFP+LacZ+: electroporated GFP+ cells. Blimp1+LacZ+: electroporated cells that expressed Blimp1 protein. LacZ+: all electroporated cells. Error bars: SD. (E-G) Schematics of plasmids are shown on top. CAG-loxP-STOP-loxP-EGFP: Cre activity reporter. CAG-H2bRFP: electroporation efficiency control, which constitutively expressed H2bRFP in all electroporated cells. Vector-Cre: negative control for background signals. CAG-Cre: positive control for Cre activity. B108-Cre: Cre expression was driven by B108. The indicated combinations of plasmids were electroporated into P0 retinas in vivo. Retinas were harvested at P14 and stained with anti-GFP (green), anti-Chx10 (blue), anti-Pax6 (blue), or anti-Sox9 (blue) antibodies. (H-K) Quantification of the fate-mapping experiment. The percentage of electroporated retinal cells of each type that turned on the Cre reporter was quantified. Electroporated rods: H2bRFP+ cells in the outer nuclear layer. Electroporated bipolar cells (BP): H2bRFP+Chx10+. Electroporated amacrine cells (AC): H2bRFP+Pax6+. Electroporated Müller glial cells (MG): H2bRFP+Sox9+. Vector: plasmid combinations in panel E. CAG: plasmid combination in panel F. B108: plasmid combination in panel G. Error Bars: SEM. Two-tailed student's TTEST (*P<0.01; **P<0.001). N≥3. Scale bar: 10μm. See also Figure S2.

Expression driven by the B108 enhancer was analyzed for fidelity of expression by comparing it with that of the native Blimp1, which is transiently expressed. From postnatal day 0 (P0) to P3, Blimp1 is broadly expressed in many retinal cells. Later, its expression is down regulated, becoming undetectable by antibody staining and northern blot assay after P7 (Brzezinski et al., 2010; Katoh et al., 2010). The expression pattern of EGFP driven by B108 was examined relative to immunohistochemistry (IHC) for Blimp1 at different developmental stages. When the B108 reporter was electroporated into retinas in vivo at P0, ~90% of EGFP+ cells were positive for Blimp1 IHC signals by P3 (Figure 2A-D). Consistent with endogenous Blimp1 expression pattern, EGFP expression driven by B108 was down regulated beginning at P7 (Supplemental Figure 2A). We could detect low EGFP expression in rods after P7 if anti-GFP antibody was used to amplify the signal, possibly due to the greater stability of EGFP proteins/mRNAs relative to Blimp1, and/or missing elements that are responsible for down regulation of Blimp1 within B108 (Supplemental Figure 2B). To investigate one possible element for down-regulation, we tested whether the addition of the Blimp1 3’ UTR to the B12kb construct would lead to a reduction in expression (Supplemental Figure 7A). Indeed, a significant reduction was seen, in keeping with previous studies of Blimp1 regulation in other tissues, which showed that microRNAs down regulate Blimp1 through a 3’ UTR site (Nie et al., 2008; West et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011). In addition, as Blimp1 has been shown to negatively regulate its own expression, we co-electroporated CAG-Blimp1 with the B12kb reporter plasmid, and again observed evidence of negative regulation (Supplemental Figure 7B). Overall, the onset of expression and the cells that activated the B108 enhancer recapitulated the endogenous expression of Blimp1 during early postnatal retina development, and additional elements within a larger regulatory region of Blimp1 are responsible for fine tuning the down-regulation.

Blimp1 has been reported to be expressed predominantly in postmitotic cells in the developing retina (Brzezinski et al., 2010; Katoh et al., 2010). We thus investigated whether B108 activated EGFP expression in postmitotic cells by using EdU, a thymidine analogue, to mark cells in S phase. EGFP+ cells were rarely found to be EdU+ one hour after EdU administration, demonstrating that B108 was not active in S-phase retinal cells (Supplemental Figure 2D). We further addressed whether B108 would be active in G2 or M phase by an EdU pulse-chase assay. In the postnatal developing retina, the cell cycle length of mitotic progenitors is roughly 30 hours (S phase: 16 hours; G2 phase: 3 hours; M phase: 2 hours; G1 phase: 8 hours) (Young, 1985b). Following a short pulse of EdU and a 20-hour chase, the majority of EdU+ cells should be in G1/G0 phase (Supplemental Figure 2C). Analysis of cells after a 20-hour chase showed that most EdU+ cells (in G1/G0 phase) had not turned on EGFP expression, suggesting that they needed more time to activate B108 (Figure S2D). These experiments further validate the B108 enhancer, as it predominantly drives expression in postmitotic cells of the postnatal retina, consistent with the timing of Blimp1 activation.

Lastly, a recent study used the Blimp1-Cre BAC-transgenic mouse to trace cells with a Blimp1 expression history. Nearly all photoreceptors, about 30% of bipolar and amacrine cells, roughly half of horizontal cells, and very few Müller glial cells showed a history of Blimp1 expression (Brzezinski et al., 2013). We were interested in the fate of the cells that activated the B108 enhancer. Since B108 activity was down regulated as the cells matured, we needed to use a history assay to determine which cell fates were marked by the transiently active B108 enhancer. To this end, we used B108 to drive Cre expression. A control construct with no enhancer led to very few cells with Cre history (Figure 2E). Cells that activated B108 primarily became rods, with a few becoming amacrine and Muller glial cells, but almost no bipolar cells (Figure 2E-K). This demonstrated that B108 preferentially tracked the postnatal Blimp1-expressing cells that adopted the rod photoreceptor fate.

These results demonstrate that the B108 enhancer drives expression in a manner that substantially mimics the endogenous Blimp1 expression in the developing postnatal mouse retina, during the period when rod photoreceptors and bipolar cells are born.

CRISPR/Cas9-based genome engineering demonstrates that B108 is necessary for endogenous Blimp1 expression

To gain a better understanding of the regulation of the endogenous Blimp1 gene, we investigated whether B108 was required for endogenous Blimp1 expression. With the recent advance of the RNA-guided genome engineering technique, using CRISPR/Cas9, targeted engineering of genomic DNA has the potential to allow a rapid assessment of CRMs within the genome (Cong et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013; Sternberg et al., 2014). We thus tested whether CRISPR/Cas9 could effectively allow engineering of the mouse genome in vivo in the retina.

The general efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 in mouse retinas was examined using the RosamTmG/mTmG mouse strain, which is a Cre reporter knock-in line that utilizes both GFP and tdtomato reporters (Muzumdar et al., 2007). This line expresses membrane GFP (mGFP) in tissues following the Cre-mediated excision of the membrane Tdtomato (mTdtomato) cassette (Supplemental Figure 3A). We constructed a CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid CRISPRmTmG to specifically generate DNA double stranded breaks near both LoxP sites, by inserting ~20bp targeting sequences into the CRISPR/Cas9 vector plasmid (Px330), which expresses both Cas9 and guide RNAs in one plasmid (For detailed procedures, please see Article+ supplementary file). Upon successful cleavage, the ends of the cleaved DNA are predicted to ligate to each other via the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway, resulting in the deletion of the mTdtomato cassette and the switching on of the mGFP expression. The CRISPRmTmG plasmid was introduced into retinas of RosamTmG/mTmG mouse pups in vivo at P0 by electroporation. After 21 days, in the electroporated region, a significant number of retinal cells turned on mGFP expression, suggesting that CRISPRmTmG successfully deleted the mTdtomato cassette from the genome (Supplemental Figure 3B). Roughly 80% of rods, 30% of bipolar cells, 70% of Muller glial cells and 40% of amacrine cells, which received the CRISPRmTmG plasmid, turned on mGFP expression.

Given the relatively high efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 in the retina in vivo, we next investigated whether we could delete the B108 enhancer from the genomic locus. CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids were constructed to generate double strand breaks 5’ and 3’ to B108 in the mouse genome, and PCR primers were designed to detect the deletion (Figure 3A). To assay whether the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids could delete B108, retinal cells were electroporated in vivo with CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids and an EGFP co-electroporation marker (Figure 3B). Genomic DNA was prepared from FACS sorted EGFP+ retinal cells and was subjected to PCR. A smaller PCR fragment, the size predicted for the B108 deletion, was observed only when this locus was targeted (The L band in Figure 3B). Sequencing of the L band PCR fragments as a population revealed that the majority of the cleavage events directed by the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids, B51 and B33, were at positions 3 bp 5’ to the PAM sequence, as predicted for CRISPR/Cas9 activity (Figure 3C) (Cong et al., 2013). To further investigate the distribution and types of sequence changes in the targeted region, both the H band, which corresponded to the WT size, and the L band, were cloned and individual clones were sequenced (Figure 3B and Supplemental Figure 3C-D). The majority of products in the L band were as seen in the bulk population sequence analysis, that is, the same result shown in Figure 3C. In addition, there were single cleavage events recorded in the products from the H band, and a few other insertions and deletions were seen in a minority of the products cloned from the H and L bands (Supplemental Figure 3C-D). These results demonstrated that CRISPR/Cas9 could be used to assess the requirement for B108 in regulation of Blimp1 in vivo.

Figure 3. Deletion of B108 from the genome by CRISPR/Cas9 in retinal tissue.

(A) Schematics of CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids targeting the B108 genomic region. B51, B53, B31 and B33: CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids. pF and pR: primers for the amplification of the targeted region. (B) B51 and B33 or B53 and B31 were co-electroporated into P0 retinas ex vivo with the CAG-EGFP plasmid which labels all the electroporated cells. Retinas were cultured as explants for 5 days, harvested and dissociated. Genomic DNA was extracted from FACS sorted EGFP+ retinal cells and subjected to PCR. L (white arrow): a lower molecular weight band created by CRISPR/Cas9. H: the band predicted to be the size of a WT or once-cut PCR product. Control: no CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids were introduced. (C) The sequence of the L band from panel B. PAM (red) sequences and CRISPR targeting sites (purple and blue) are highlighted. (D) Schematics of the Chx10BP-LCL-EGFP reporter. (E) Experimental design to test the necessity of the genomic B108. CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids, B108-Cre and Chx10BP-LCL-EGFP were co-electroporated into P0 retinas in vivo. Retinas were harvested and examined at P14. (F) Retina sections were stained with anti-GFP antibody (green) and DAPI (blue). (G) The percentage of EGFP+ cells over all labeled bipolar cells. Error bars: SEM. Two-tailed student's TTEST (*P<0.015). N=3. Scale Bar: 10μm. For detailed procedures, please see Article+ supplementary file. See also Figure S3.

Blimp1 conditional knockout (CKO) mice have been shown to have an increase in bipolar cells and a decrease in rod photoreceptors (Brzezinski et al., 2010; Katoh et al., 2010). If the B108 enhancer is required for Blimp1 expression, then the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of B108 should recapitulate the CKO phenotype. The lack of molecular markers that label cells with successful CRISPR deletion, and the fact that the loss-of-function phenotype is apparent only after Blimp1 expression is down regulated, made it difficult to assess the phenotype of cells that had lost the B108 enhancer. Thus, we used the Cre recombinase based fate-mapping strategy and examined whether the production of bipolar cells was increased upon B108 deletion. We were able to follow cells that took on the bipolar fate following CRISPR/Cas9 action using a reporter plasmid for bipolar cells.

To report bipolar cell identity, the Cre-sensitive reporter plasmid, Chx10BP-LCL-EGFP, was constructed (Figure 3D). This reporter plasmid not only labels bipolar cells specifically, it also can switch expression of fluorescent reporter genes following Cre-mediated excision. A previously identified Chx10 enhancer that is only active in bipolar cells was used to drive fluorescent protein expression (Emerson and Cepko, 2011; Kim et al., 2008a). Without Cre, bipolar cells are labeled with mCherry (Figure 3D). Following Cre-mediated excision of mCherry, EGFP would be expressed. To test this construct as a reporter of B108-Cre activity, the B108-Cre plasmid was delivered into P0 retinas in vivo along with the Chx10BP-LCL-EGFP reporter. Consistent with our previous experiment, most bipolar cells were labeled by mCherry, i.e. they did not have a history of activating B108-Cre (Figure 2G and 3F-G). To determine if deletion of the endogenous B108 element from the endogenous Blimp1 gene would result in a phenotype consistent with the Blimp1 CKO phenotype, the Blimp1 B108 CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids (B51+B33 or B53+B31), along with the B108-Cre and Chx10BP-LCL-EGFP plasmids were electroporated into P0 retinas in vivo, and the expression of the Chx10BP-LCL-EGFP reporter was assessed at P14 (Figure 3E. For detailed procedures, please see Article+ supplementary file). The B108-Cre plasmid does not encode the PAM sequence or the CRISPR/Cas9 target sites, so would be unaffected by the CRISPR activity. In contrast to a no CRISPR/Cas9 control, a significant number of EGFP+ bipolar cells were observed when the endogenous B108 was targeted (Figure 3F-G). This result phenocopies the Blimp1 CKO result, wherein more bipolar cells are generated in the absence of Blimp1, demonstrating the necessity of the B108 enhancer for proper Blimp1 regulation in the retina. This result also demonstrates that the cell fate change seen following loss of Blimp1 is a cell autonomous effect.

Identification of critical transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) in the B108 enhancer

In order to understand the transcriptional regulation of Blimp1, the B108 enhancer was subjected to a series of analyses to identify TFBSs and their cognate TFs. We first examined the B108 sequence for sequence conservation, and then searched for putative TFBSs within the conserved sequences. B108 showed high sequence conservation among several species ranging from zebrafish to human, with some stretches of nucleotides showing 100% conservation (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 4). These highly conserved stretches appeared in clusters, which further suggested they might be functional regulatory regions (Arnone and Davidson, 1997; Berman et al., 2002; Wasserman and Fickett, 1998). To test for function, selected clusters were mutated individually and these mutated reporters were electroporated into retinas to assess reporter activity. Two of these mutations significantly decreased enhancer activity compared with the wild type B108 (RORm and Otxm, Supplemental Figure 4). These two clusters were each deleted, and the deletion constructs also showed a loss of enhancer activity (ΔROR and ΔOtx2, Supplemental Figure 4). Analysis of these two sequences for TFBSs by the rVista program and TRANSFAC algorithms, suggested that these two sites corresponded to the binding sites of RORβ and Otx2/Crx (Loots and Ovcharenko, 2004; Matys et al., 2006). To test the sufficiency of the RORβ and Otx2/Crx binding sites, they were tested for their ability to drive EGFP in retinas in the absence of other B108 sequences. These two TFBSs were able to drive strong EGFP expression in the retina (ROx2, Supplemental Figure 4).

RORβ and Otx2 regulate Blimp1 expression via the B108 enhancer

We examined whether RORβ and Otx2/Crx were indeed upstream regulatory TFs of Blimp1 by addressing whether RORβ and Otx2/Crx were necessary for the activation of B108, as well as the endogenous Blimp1 gene. We generated plasmids with shRNAs that could efficiently knock down RORβ, Otx2, Crx or control LacZ expression (Supplemental Figure 5). These shRNA constructs were designed based on microRNA structures that allowed for the use of PolII promoters such as the CAG promoter, and were located within the 3’UTR of mCherry, which allowed for the tracking of shRNA expression via expression of mCherry (Supplemental Figure 5A) (Qiu et al., 2008).

When either the RORβ-shRNA or Otx2-shRNA plasmids were introduced into retinas, the activity of the B108-EGFP reporter was dramatically decreased compared with controls within 24 hours (Figure 4A-B). In contrast, knock down of Crx did not affect the activity of B108. These results suggested that RORβ and Otx2 were required for the activation of B108. To further investigate the requirement of Otx2, an Otx2Flox/Flox conditional mouse strain was used. Electroporation of this strain with B108-EGFP reporter and Cre showed a significant reduction in the activity of B108 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. RORβ and Otx2 regulate B108.

(A) Knock down of RORβ and Otx2 reduced B108 activity. Plasmids that contained different shRNA cassettes were electroporated into P0 retinas ex vivo with B108-EGFP (2:1 ratio), and the electroporation efficiency control CAG-mCherry. Two different shRNA constructs were used for knocking down RORβ or Otx2. Retinas were cultured as explants for 24 hours and examined. Scale Bar: 1mm. (B) Quantification of B108 activity. The ratio of total EGFP intensity over mCherry intensity was calculated (Fiji software), and normalized to LacZ-shRNA controls. Error bars: SEM. Two-tailed student's TTEST (*P<0.01). N≥4. (C) The experimental design to test whether Otx2 is required for the activation of B108. Indicated combinations of plasmids were electroporated into P0 Otx2Flox/Flox retinas ex vivo. Retinas were cultured as explants for 24 hours and examined. Scale bars: 500um. (D-E) EMSA assays. Probe sequences are shown. CAG-LacZ, CAG-Otx2 or CAG-RORβ lysates: nuclear extracts of 293T cells that were transfected with CAG-LacZ, CAG-Otx2 or CAG-RORβ plasmid. P3 retina lysate: nuclear extracts of P3 mouse retinas. Anti-GFP antibody was used as a negative control. Anti-RORβ and anti-Otx2 antibodies were included as indicated. See also Figure S4 and S5.

To explore whether RORβ and Otx2 could directly bind to B108, we performed EMSA assays (Figure 4D-E). The fragments within B108 that contained RORβ or Otx2 binding sites were used as DNA probes. Strong electrophoretic mobility bands were detected when the wild type RORβ probe was mixed with RORβ-enriched nuclear extracts from 293T cells or wild type P3 retina nuclear extracts. When RORβ antibody was incubated with EMSA probes and retina nuclear extracts, the primary EMSA band disappeared, suggesting that the RORβ antibody prevented the binding of RORβ proteins to labeled DNA probes. Furthermore, when the RORβ binding site was mutated in the EMSA DNA probe, no shifted band was detected, which demonstrated the specificity of the binding (Figure 4D-E). Similar results were observed for Otx2, demonstrating that the regulation of B108 is likely through direct binding of Otx2 and RORβ.

We further examined whether RORβ or Otx2 were required for the activation of the endogenous Blimp1 gene. As loss of function of either Otx2 or RORβ leads to changes in retinal cell types, we wished to assay whether reduction in the expression of these TFs would affect Blimp1 expression, without the confound of changes in retinal cell types. In addition, as electroporation does not target a large number of cells, and there is a great deal of heterogeneity in the population of cells that are electroporated, we preferred a method that could be applied to individual cells to measure mRNA levels. To this end, we used single molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (Single Molecule FISH) (Raj and van Oudenaarden, 2009). This technique uses numerous DNA probes (each probe is ~20bp long, conjugated directly with fluorophores) to detect a single mRNA molecule in situ. The hybridized probes produce a single fluorescent dot on a single mRNA molecule (Figure 5A and 5D). Quantification of the number of dots per cell provides a measure of the relative mRNA levels for the target gene. We utilized this technique to detect Blimp1 mRNA levels after shRNA knock down of RORβ or Otx2. Otx2-shRNA, RORβ-shRNA or LacZ-shRNA were placed 3’ to the EGFP gene and only EGFP+ retinal cells were quantified. Single molecule FISH probes for RORβ mRNA, Otx2 mRNA or Blimp1 mRNA levels were utilized (Figure 5). Twenty-four hours after shRNA plasmids were electroporated into retinas, when many retinal cells would still be in the same cell cycle (retinal cell cycle length: ~30h), the FISH was performed for all 3 genes in individual EGFP+ retinal cells.

Figure 5. RORβ and Otx2 regulate endogenous Blimp1 gene expression.

(A and E) Representative images of retinal cells detected by single molecule FISH. Otx2-shRNA1, RORβ-shRNA1 or LacZ-shRNA cassette was placed behind an EGFP gene driven by the CAG promoter. Each plasmid was electroporated into P0 retinas ex vivo. Retinas were cultured for 24 hours before dissociation. The expression levels of RORβ, Otx2 or Blimp1 were detected by Cy3 labeled RORβ probes, Cy3 labeled Otx2 probes and Cy5 labeled Blimp1 probes. Individual EGFP+ retinal cells that expressed the shRNA are circled. DAPI marks the nuclei. RORβ probes and Blimp1 probes were co-applied in panel A. Otx2 probes and Blimp1 probes were co-applied in panel E. Scale bar: 10um (B) Quantification of RORβ mRNA levels. LacZ-shRNA (blue): EGFP+ cells treated with control LacZ-shRNA. RORβ-shRNA (green): EGFP+ cells treated with RORβ-shRNA. (C and G) Quantification of Blimp1 mRNA levels. (F) Quantification of Otx2 mRNA levels. Otx2-shRNA (Red): EGFP+ cells treated with Otx2-shRNA. X-axis: the number of dots in each EGFP+ cell. Y-axis: the percentage of cells that have the indicated number of dots. Error bars: SEM. Two-tailed student's TTEST (*P<0.05; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). N=4 (For each N, more than 200 EGFP+ cells were counted). See also Figure S5.

In the presence of RORβ-shRNA, significantly fewer retinal cells had a high number of RORβ signals compared with the LacZ-shRNA control, demonstrating the RORβ-shRNA could successfully knock down endogenous RORβ levels within 24 hours (Figure 5A-B). More importantly, significantly fewer retinal cells had a high number of Blimp1 signals when RORβ expression was targeted (Figure 5A and 5C). Similar experiments were performed with the Otx2-shRNA. Compared with controls, significantly fewer retinal cells contained a high number of Otx2 signals and Blimp1 signals, when the Otx2-shRNA was introduced (Figure 5D-F). These data demonstrate that RORβ and Otx2 are positive regulators of endogenous Blimp1 expression.

Blimp1 and Otx2 form a negative feedback loop to ensure proper rod photoreceptor formation

When examining the relationship between Otx2 and Blimp1, we discovered two Blimp1 binding sites (AGNGAAAG) in a 5’ region of a 600bp Otx2 enhancer element, ECR2, which we previously showed to be active in developing photoreceptors (Supplemental Figure 6A) (Emerson and Cepko, 2011; Katoh et al., 2010). Given that Blimp1 predominantly functions as a transcriptional repressor (John and Garrett-Sinha, 2009), we investigated whether Blimp1 could repress the activity of the Otx2ECR2 enhancer. Electroporation of the Otx2ECR2 reporter and a Blimp1 expression plasmid revealed that the activity of ECR2 was significantly inhibited by Blimp1 overexpression (Supplemental Figure 6B-C). Disruption of one of the Blimp1 binding sites released the repression of Blimp1 on ECR2 (Supplemental Figure 6C-D). EMSA assays further showed that Blimp1 could directly bind to the Otx2ECR2 enhancer (Supplemental Figure 6E). These data demonstrated that Blimp1 and Otx2 can form a negative feedback loop, which might be required for the genesis of the proper ratio of rod and bipolar cells at postnatal stages.

In mature retinas, rod photoreceptors express low levels of Otx2, while bipolar cells express high levels of Otx2 (Fossat et al., 2007). In addition, the majority of Blimp1+ cells in the postnatal retina develop into rod photoreceptors (Figure 2G-H) (Brzezinski et al., 2013). These two observations, and that described above of Blimp1-mediated repression of Otx2, suggested that the expression level of Otx2 might be repressed by Blimp1, and that the level of Otx2 might play a role in the specification of these two cell types. To test this hypothesis, B108 was used to drive constant high levels of Otx2 expression in Blimp1 expressing cells, whose fates were then traced.

As used previously in the experiment described in Figure 3, the Cre-sensitive bipolar reporter plasmid, Chx10BP-LCL-EGFP, was used to report bipolar cells (Figure 3D). When Cre-expressing cells become bipolar cells, they turn on EGFP expression, while bipolar cells with no history of Cre are marked by mCherry (Figure 3F and 6A-B). In controls, B108 was used to drive only Cre expression. Consistent with our previous observation, very few EGFP+ bipolar cells were observed, demonstrating that cells that activated B108-Cre do not usually adopt bipolar cell fates (Figure 2G-K, 3F and 6C). To drive sustained ectopic Otx2 expression only in Blimp1+ cells, the B108-Otx2-IRES-Cre plasmid was constructed, to express Otx2 and Cre at the same time under the control of B108. Cre could delete the mCherry cassette within the Chx10BP-LCL-EGFP reporter, leading to EGFP+ bipolar cells. Following introduction of B108-Otx2-IRES-Cre along with the bipolar Chx10BP-LCL-EGFP reporter in vivo into P0 retinas, a significant number of EGFP+ bipolar cells were observed at P14 (Figure 6D-E). This result illustrated that high levels of Otx2 significantly increased the probability that Blimp1+ cells, which normally adopt the rod fate, now adopt the bipolar cell fate. To further investigate the Otx2 dose-sensitivity for the rod vs bipolar fate decision, Otx2 levels were reduced by shRNA in vivo. This led to the formation of more rods and fewer bipolar cells (Figure 6F). In contrast, when retroviruses that expressed Otx2 and a marker gene, human placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), were used to infect retinas at P0 in vivo, the number of bipolar cells was significantly increased compared with controls (Figure 6G). A retrovirus construct designed to overexpress Otx2 was previously used for a similar experiment in the retina, with the result that bipolar cells were reduced (Nishida et al., 2003). We obtained this retroviral construct, but were unable to repeat Nishida et al.'s result with their retrovirus construct.

Figure 6. Dosage of Otx2 controls the rod:bipolar ratio.

(A-D) Schematics of plasmid combinations are shown on top of each panel. Different plasmid combinations were electroporated into P0 retinas in vivo. Retinas were harvested at P21. Representative images of retina sections are shown for each condition. Red: mCherry. Green: EGFP. Scale Bar: 20um. (E) Quantification of the phenotype. The ratios of EGFP+ cells over all labeled bipolar cells were calculated. Error bars: SEM. Two-tailed student's TTEST (**P<0.01). N=3. (F) Knock-down of Otx2 increases the number of rods and reduces the number of bipolar cells. The CAG-EGFP-LacZ-shRNA or CAG-EGFP-Otx2-shRNA plasmid (LacZ-shRNA or Otx2-shRNA1 was placed in the 3’UTR of the EGFP gene) was electroporated into P0 retinas in vivo. Retinas were harvested at P14. The distribution of EGFP+ cells among different retinal cell types was examined. LacZ-shRNA: control shRNA plasmid. BP: bipolar cells. AC: amacrine cells. MG: Müller glial cells. N=3. (G) Retroviral mediated over-expression of Otx2. Schematics of retroviral constructs are shown on top. AP: human placental alkaline phosphate (PLAP). pLIA or pLIA-Otx2 retroviruses (titer: 10^7) were injected into P0 retinas in vivo. Tissue was harvested, and processed for AP detection at P21. The percentage of AP+ cells that were rod, bipolar (BP), amacrine (AC) or Müller glial cells (MG) was calculated. Error bars: SEM. Two-tailed student's TTEST (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). N≥3. See also Figure S6.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to understand the GRN that regulates one of the binary cell fate specification events in the postnatal retina. We focused specifically on the decision to become a rod or a bipolar cell within a particular time window, P0-P3, when this decision is being made in siblings of a terminal division (Turner and Cepko, 1987). The study was initially focused on Blimp1, a node in the rod-bipolar GRN. Identification of a small element, B108, allowed for the discovery of the regulators of this gene, as well as provided a starting point for the interrelationships among other elements in this GRN.

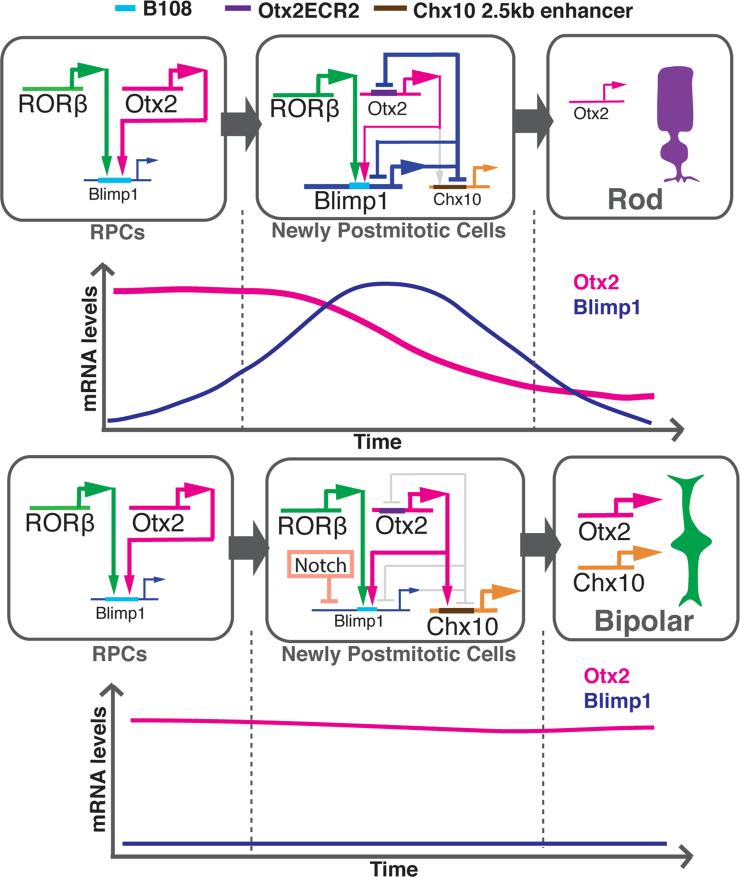

The model shown in Figure 7 summarizes our current understanding of the rod-bipolar GRN. At postnatal stages, RORβ and Otx2 initiate Blimp1 expression in RPCs that are about to produce postmitotic daughter cells. As the level of Blimp1 rises, there is direct negative feedback on Otx2, and Blimp1 negatively regulates its own expression (Supplemental Figure 7B), as has been shown in other systems (Magnúsdóttir et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2007). Cells that experience the drop in Otx2 levels enter into the rod pathway. An additional arm of the GRN ensures that the cells with a high Blimp1 level do not enter into the bipolar pathway. Previous studies showed that Blimp1 also represses Chx10, a TF that is essential for bipolar cell genesis (Burmeister et al., 1996; Katoh et al., 2010). As a result of these repressive activities of Blimp1, the expression level of Otx2 and Chx10 are reduced, which favors the rod fate. Additional support for this model comes from misexpression of Otx2, which results in over-production of bipolar cells, likely at the expense of rod photoreceptors (Figure 6G), and previous work showed the same result when Chx10 was overexpressed (Livne-Bar et al., 2006). Similarly, reduction of Blimp1 expression leads to overproduction of bipolar cells (Brzezinski et al., 2010; Katoh et al., 2010), most likely through the resulting up regulation of Chx10 and Otx2. In cells that will adopt the bipolar fate, it is possible that Blimp1 expression is also initiated by RORβ and Otx2, as these two genes are expressed in bipolar cells (Chow et al., 1998; Fossat et al., 2007). However, as Blimp1 would is not expressed at detectable levels in bipolar cells, it may not be activated in these cells, or it is quickly repressed following activation, by as yet undefined repressive effects in bipolar cells. An additional element of this GRN involves Notch1. We and others previously found that Notch1 inhibits photoreceptor formation and is required for bipolar formation (Jadhav et al., 2006; Mizeracka et al., 2013a; Yaron et al., 2006). Analysis of mRNA levels in single cells from which Notch1 was deleted showed a strong up regulation of Blimp1 (Mizeracka et al., 2013b). Constitutive activation of the Notch signaling pathway significantly suppressed endogenous Blimp1 expression in the retina (Supplemental Figure 7C). These results suggest that the Notch signaling pathway, at least in part, promotes bipolar formation and inhibits rod formation via repression of Blimp1. Further studies on the relationships among bHLH genes downstream of Notch, as well as the Notch-regulated TFs, such as Hes1, Ids, and Blimp1, will help to elucidate the complete GRN that governs the rod vs bipolar cell fate specifications (Bramblett et al., 2004; Cherry et al., 2011; Mizeracka et al., 2013b; Morrow et al., 1999; Ohsawa and Kageyama, 2008). One other regulatory mechanism that controls the level of Blimp1 is microRNA regulation via the 3’ UTR. Previous work in other tissues showed that the microRNAs, Let7a, miR9 and miR125b, are relevant microRNAs for this negative regulation (Nie et al., 2008; West et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011). Interestingly, these same microRNAs are present in the retina, and likely play a role in the temporal progression of retinal cell fate specification (La Torre et al., 2013), perhaps in part through regulation of Blimp1.

Figure 7. Model of the GRN that regulates rod and bipolar cell fate specification.

Otx2 and RORβ up-regulate Blimp1 expression in newly postmitotic cells produced by postnatal RPCs. As its level increases, Blimp1 represses the expression of Otx2, Chx10 and Blimp1. As a result, retinal cells with low levels of Otx2 adopt the rod fate. An additional regulator in this GRN is Notch, which is transcribed in the newly postmitotic cells, and inhibits Blimp1. As a result, these retinal cells obtain high levels of Otx2 and Chx10, and adopt bipolar cell fates. Otx2 might also be a critical positive regulator of Chx10 in bipolar cells via a distal enhancer, the Chx10 2.5kb enhancer (Kim et al., 2008a). CRMs/enhancers of the GRN are highlighted bars within each gene's horizontal representation. See also Figure S7.

The importance of TF dosage in cell fate decisions has been demonstrated in several cases (Sigvardsson, 2012; Struhl et al., 1992; Taranova et al., 2006). For example, the dosage of PU.1 regulates the B lymphocyte versus macrophage cell fates in the haematopoietic system (DeKoter, 2000) and Ngn3 dictates endocrine differentiation in a dosage-dependent manner (Wang et al., 2010). However, the mechanisms that regulate the levels of these TFs have not been well defined. Here, we show that the level of Otx2 is important for regulating the rod versus bipolar fates. A low level of Otx2 promotes the rod fate, whereas a high level of Otx2 induces the bipolar cell fate, and the level of Otx2 is regulated by Blimp1 in a negative feedback loop. These findings have several implications. First, the rod and bipolar fate decision is not fixed until after the terminal mitosis, as Blimp1 protein expression is largely undetected until cell cycle exit. Consistent with this, previous studies showed that newly postmitotic cells relied upon new transcription and translation of the Notch1 gene in order to take on a non-rod fate (Mizeracka et al., 2013a). The data reported here show that at least a subset of newly postmitotic cells are sensitive to the levels of Otx2 for their fate decision. Second, it has been suggested that Otx2 might be a critical positive regulator of Chx10 in bipolar cells via a distal enhancer (Kim et al., 2008a). Thus, high Otx2 levels may promote bipolar cell formation via the activation of Chx10 (Figure 7). This may provide an explanation for the lag in bipolar cell differentiation relative to bipolar cell birthdays. Classical [3H]-thymidine birth-dating studies showed that some retinal cells born as early as P0 take on the bipolar fate, with the peak of bipolar birthdays at P4-P5 (Young, 1985a). However, bipolar cell markers do not start to appear until P6 (Kim et al., 2008b). This lag may be due, at least in part, to the time that is required for the interactions among Otx2, Chx10 and other TFs to occur in the rod-bipolar GRN to fix the bipolar fate.

Expression profiling studies demonstrated that there is a great amount of molecular heterogeneity among RPCs (Trimarchi et al., 2008). Early clonal lineage analyses showed that RPCs at the same developmental stage could give rise to various clonal compositions (Turner and Cepko, 1987). More recently, lineage studies that examined the clonal progeny of specific RPCs showed that there are distinctive types of RPCs, which are biased to produce different types of retinal cells. Olig2, a bHLH gene, was found to be expressed in the RPCs that do not make bipolar cells and rods (Hafler et al., 2012). It will thus be of interest to determine whether Blimp1, Otx2, and Chx10 regulation might occur differently in Olig2+ and Olig2− RPCs.

In addition to the findings regarding the rod and bipolar GRN, we report the use of two relatively new techniques. Single molecule RNA FISH was shown to be able to detect gene expression levels in individual cells in a sensitive and quantitative manner. Since the levels of TFs can be important for developmental events, the quantitative nature of single molecule RNA FISH makes it a valuable method for evaluating transcript levels. In addition, we showed that CRISPR/Cas9 could successfully delete targeted regions of the genome following electroporation in vivo. Deletion at the Rosa locus was very efficient, with the rates varying somewhat with the cell type. It is not clear if the lower rate seen in e.g. bipolar cells relative to rods, might be due to the relatively lower expression of CRISPR/Cas9 in bipolar cells, as we have noted lower levels of expression in bipolar cells from the CAG promoter. Chromatin structure might be another factor that varies among cell types. Enhancer regions, often associated with low nucleosome occupancy, may make these regions relatively sensitive to CRISPR/Cas9 engineering (Buecker and Wysocka, 2012), an asset when studying the role of such sequences.

Overall, we explored the GRN operating within late RPCs and their newly postmitotic progeny at the time when rod and bipolar cell fate decisions are being made, and identified how TFs inputs are integrated via CRMs to control the binary cell fate specification event. As more and more TFs and CRMs are analyzed in the context of GRNs, it should be possible to assemble relatively complete GRNs and study their precise and complex regulation by establishing computational models.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Wild type neonatal mice were obtained from timed pregnant CD1 mice (Charles River Laboratories). Otx2flox/flox mice were obtained from S. Aizawa (RIKEN Center for Departmental Biology, Kobe, Japan). RosamTmG/mTmG mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Stock number: 007576). All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Harvard University.

Plasmids

The CAG-EGFP, CAG-LNL-EGFP, CAG-Cre, CAG-mCherry, CAG-LacZ plasmids were from Matsuda and Cepko (Matsuda and Cepko, 2007). The CAG-H2bRFP was a gift from Dr. S. Tajbakhsh. The Stagia3 vector was from Emerson and Cepko (Billings et al., 2010; Emerson and Cepko, 2011). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Article+ supplementary file for details about the construction of all other plasmids.

In vivo and ex vivo plasmid electroporation

Ex vivo and in vivo retina electroporation was carried out as described (Cherry et al., 2011; Matsuda and Cepko, 2007). All ex vivo and in vivo electroporation experiments were repeated with at least three biological replicates. Plasmids were mixed in equal mass ratios and electroporated at a concentration of 500ng/μl to 1μg/μl per plasmid. For additional details, see Article+ supplementary file.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Dissected mouse retinas were prepared as previously described (Cherry et al., 2011). A Leica CM3050S cryostat (Leica Microsystems) was used to prepare 20μm cryosections. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for detailed antibody sources and dilutions. EdU detection was performed with a Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 594 imaging kit (C10339, Invitrogen).

Dissociation of retina tissues and single molecule FISH

Retinal tissues were dissociated as described previously (Trimarchi et al., 2008). Dissociated retinal cells were left on poly-D-lysine (0.1mg/ml, Millipore) treated slides for 1 hour at 37°C, and fixed on slides in 4% PFA (DEPC, pH7.4) for 15min at room temperature. Single molecule FISH probes were designed and ordered from Biosearch Technologies and their protocol was followed. Slides were imaged immediately after single molecule FISH by Nikon Ti Inverted Fluorescence Microscope with Perfect Focus (Nikon Imaging center @ Harvard Medical School). Images were then analyzed by Imaris software (Bitplane).

EMSA assay

EMSA assays were performed as described previously (Kim et al., 2008a). Roughly 1X106 293T cells were transfected with 1 μg of CAG-LacZ, CAG-Otx2 or CAG-RORβ plasmid. Nuclear extracts were prepared from these cells or P3 wild type mouse retinas using NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagent kit (Pierce). Complementary oligonucleotides (Figure 4D) were ordered, annealed and labeled by DNA 3’ End Biotinylation kit (Pierce). Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Pierce) was used to detect biotin-labeled probes after EMSA assay.

Image analysis

All images of retinal sections were acquired by the Zeiss LSM780 inverted confocal microscope. Retina explants were imaged by Nikon Eclipse E1000 microscope. 293T cells were imaged by Leica DMI3000B inverted microscope. Images in Figure 2, 3F and 6 were maximum projections of 5μm tissues, and were quantified by the Imaris software (Bitplane). Images in Figure 4 were quantified by calculating total fluorescent intensities of EGFP or mCherry via Fiji software.

Statistical Methods

Two-tailed student's T-TEST was used to compare differences between control and experimental values.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Arjun Raj for valuable suggestions on single molecule FISH and Dr. Le Cong for advice about CRISPR/Cas9. Dr. Jianming Jiang and Dr. Jonathan Seidman kindly provided the shRNA backbone plasmids (unpublished). We thank Takahisa Furukawa for supplying a retroviral plasmid construct for Otx2. Support was provided by HHMI (to C.L.C. and S.W.) and The Foundation Fighting Blindness (to M.E.). The members of the Cepko, Tabin and Dymecki laboratories provided valuable discussion and support for this project.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information contains seven supplemental figures and Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

REFERENCES

- Afelik S, Jensen J. Notch signaling in the pancreas: patterning and cell fate specification. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Developmental biology. 2013;2:531–544. doi: 10.1002/wdev.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone MI, Davidson EH. The hardwiring of development: organization and function of genomic regulatory systems. Development (Cambridge, England) 1997;124:1851–1864. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.10.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman BP, Nibu Y, Pfeiffer BD, Tomancak P, Celniker SE, Levine M, Rubin GM, Eisen MB. Exploiting transcription factor binding site clustering to identify cis-regulatory modules involved in pattern formation in the Drosophila genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:757–762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231608898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings N, Emerson M, Cepko C. Analysis of thyroid response element activity during retinal development. PloS one. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucherie C, Sowden J, Ali R. Induced pluripotent stem cell technology for generating photoreceptors. Regenerative medicine. 2011;6:469–479. doi: 10.2217/rme.11.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramblett D, Pennesi M, Wu S, Tsai M-J. The transcription factor Bhlhb4 is required for rod bipolar cell maturation. Neuron. 2004;43:779–793. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski J, Lamba D, Reh T. Blimp1 controls photoreceptor versus bipolar cell fate choice during retinal development. Development (Cambridge, England) 2010;137:619–629. doi: 10.1242/dev.043968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski J, Uoon Park K, Reh T. Blimp1 (Prdm1) prevents re-specification of photoreceptors into retinal bipolar cells by restricting competence. Developmental biology. 2013;384:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buecker C, Wysocka J. Enhancers as information integration hubs in development: lessons from genomics. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2012;28:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister M, Novak J, Liang M, Basu S, Ploder L, Hawes N, Vidgen D, Hoover F, Goldman D, Kalnins V, et al. Ocular retardation mouse caused by Chx10 homeobox null allele: impaired retinal progenitor proliferation and bipolar cell differentiation. Nature genetics. 1996;12:376–384. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry T, Wang S, Bormuth I, Schwab M, Olson J, Cepko C. NeuroD factors regulate cell fate and neurite stratification in the developing retina. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31:7365–7379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2555-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow L, Levine E, Reh T. The nuclear receptor transcription factor, retinoid-related orphan receptor< i> β</i>, regulates retinal progenitor proliferation. Mechanisms of development. 1998 doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran F, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu P, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKoter RP. Regulation of B Lymphocyte and Macrophage Development by Graded Expression of PU.1. Science. 2000;288 doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson M, Cepko C. Identification of a retina-specific Otx2 enhancer element active in immature developing photoreceptors. Developmental biology. 2011;360:241–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossat N, Le Greneur C, Béby F, Vincent S, Godement P, Chatelain G, Lamonerie T. A new GFP-tagged line reveals unexpected Otx2 protein localization in retinal photoreceptors. BMC developmental biology. 2007;7:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf T, Enver T. Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature. 2009;462:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nature08533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafler B, Surzenko N, Beier K, Punzo C, Trimarchi J, Kong J, Cepko C. Transcription factor Olig2 defines subpopulations of retinal progenitor cells biased toward specific cell fates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:7882–7887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203138109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav A, Mason H, Cepko C. Notch 1 inhibits photoreceptor production in the developing mammalian retina. Development (Cambridge, England) 2006;133:913–923. doi: 10.1242/dev.02245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Oh E, Ng L, Srinivas M, Brooks M, Swaroop A, Forrest D. Retinoid-related orphan nuclear receptor RORbeta is an early-acting factor in rod photoreceptor development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:17534–17539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902425106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John S, Garrett-Sinha L. Blimp1: a conserved transcriptional repressor critical for differentiation of many tissues. Experimental cell research. 2009;315:1077–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukam D, Desplan C. Binary fate decisions in differentiating neurons. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2010;20:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamachi Y, Kondoh H. Sox proteins: regulators of cell fate specification and differentiation. Development (Cambridge, England) 2013;140:4129–4144. doi: 10.1242/dev.091793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Omori Y, Onishi A, Sato S, Kondo M, Furukawa T. Blimp1 suppresses Chx10 expression in differentiating retinal photoreceptor precursors to ensure proper photoreceptor development. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:6515–6526. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0771-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Matsuda T, Cepko C. A core paired-type and POU homeodomain-containing transcription factor program drives retinal bipolar cell gene expression. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008a;28:7748–7764. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0397-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Ross S, Trimarchi J, Aach J, Greenberg M, Cepko C. Identification of molecular markers of bipolar cells in the murine retina. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2008b;507:1795–1810. doi: 10.1002/cne.21639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike C, Nishida A, Ueno S, Saito H, Sanuki R, Sato S, Furukawa A, Aizawa S, Matsuo I, Suzuki N, et al. Functional roles of Otx2 transcription factor in postnatal mouse retinal development. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:8318–8329. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01209-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Torre A, Georgi S, Reh TA. Conserved microRNA pathway regulates developmental timing of retinal neurogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301837110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Pfaff S. Transcriptional networks regulating neuronal identity in the developing spinal cord. Nature neuroscience. 2001;4(Suppl):1183–1191. doi: 10.1038/nn750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey F, Cepko C. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: lessons from the retina. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2001;2:109–118. doi: 10.1038/35053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livne-Bar I, Pacal M, Cheung M, Hankin M, Trogadis J, Chen D, Dorval K, Bremner R. Chx10 is required to block photoreceptor differentiation but is dispensable for progenitor proliferation in the postnatal retina. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:4988–4993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600083103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots G, Ovcharenko I. rVISTA 2.0: evolutionary analysis of transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnúsdóttir E, Kalachikov S, Mizukoshi K, Savitsky D, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Panteleyev A, Calame K. Epidermal terminal differentiation depends on B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:14988–14993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707323104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt K, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo J, Norville J, Church G. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masland R, Raviola E. Confronting complexity: strategies for understanding the microcircuitry of the retina. Annual review of neuroscience. 2000;23:249–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Cepko C. Electroporation and RNA interference in the rodent retina in vivo and in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:16–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235688100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Cepko C. Controlled expression of transgenes introduced by in vivo electroporation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:1027–1032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610155104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matys V, Kel-Margoulis O, Fricke E, Liebich I, Land S, Barre-Dirrie A, Reuter I, Chekmenev D, Krull M, Hornischer K, et al. TRANSFAC and its module TRANSCompel: transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34:10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister M. Multineuronal codes in retinal signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:609–614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizeracka K, DeMaso C, Cepko C. Notch1 is required in newly postmitotic cells to inhibit the rod photoreceptor fate. Development (Cambridge, England) 2013a;140:3188–3197. doi: 10.1242/dev.090696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizeracka K, Trimarchi J, Stadler M, Cepko C. Analysis of gene expression in wild-type and Notch1 mutant retinal cells by single cell profiling. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2013b;242:1147–1159. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow E, Furukawa T, Lee J, Cepko C. NeuroD regulates multiple functions in the developing neural retina in rodent. Development (Cambridge, England) 1999;126:23–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar M, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis (New York, N.Y. : 2000) 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H. Role of transcription factors in differentiation and reprogramming of hematopoietic cells. The Keio journal of medicine. 2011;60:47–55. doi: 10.2302/kjm.60.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie K, Gomez M, Landgraf P, Garcia J-FF, Liu Y, Tan LH, Chadburn A, Tuschl T, Knowles DM, Tam W. MicroRNA-mediated down-regulation of PRDM1/Blimp-1 in Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells: a potential pathogenetic lesion in Hodgkin lymphomas. The American journal of pathology. 2008;173:242–252. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida A, Furukawa A, Koike C, Tano Y, Aizawa S, Matsuo I, Furukawa T. Otx2 homeobox gene controls retinal photoreceptor cell fate and pineal gland development. Nature neuroscience. 2003;6:1255–1263. doi: 10.1038/nn1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa R, Kageyama R. Regulation of retinal cell fate specification by multiple transcription factors. Brain research. 2008;1192:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J, da Cruz L. A review and update on the current status of stem cell therapy and the retina. British medical bulletin. 2012;102:133–146. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L, Wang H, Xia X, Zhou H, Xu Z. A construct with fluorescent indicators for conditional expression of miRNA. BMC biotechnology. 2008;8:77. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, van Oudenaarden A. Single-molecule approaches to stochastic gene expression. Annual review of biophysics. 2009;38:255–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Inoue T, Terada K, Matsuo I, Aizawa S, Tano Y, Fujikado T, Furukawa T. Dkk3-Cre BAC transgenic mouse line: a tool for highly efficient gene deletion in retinal progenitor cells. Genesis (New York, N.Y. : 2000) 2007;45:502–507. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigvardsson M. Transcription factor dose links development to disease. Blood. 2012;120:3630–3631. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-455113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Theodoris C, Davidson E. A gene regulatory network subcircuit drives a dynamic pattern of gene expression. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2007;318:794–797. doi: 10.1126/science.1146524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg SH, Redding S, Jinek M, Greene EC, Doudna JA. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature. 2014;507:62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature13011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl G, Johnston P, Lawrence P. Control of Drosophila body pattern by the hunchback morphogen gradient. Cell. 1992;69:237–249. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taranova O, Magness S, Fagan B, Wu Y, Surzenko N, Hutton S, Pevny L. SOX2 is a dose-dependent regulator of retinal neural progenitor competence. Genes & development. 2006;20:1187–1202. doi: 10.1101/gad.1407906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi J, Stadler M, Cepko C. Individual retinal progenitor cells display extensive heterogeneity of gene expression. PloS one. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D, Cepko C. A common progenitor for neurons and glia persists in rat retina late in development. Nature. 1987;328:131–136. doi: 10.1038/328131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Yan J, Anderson D, Xu Y, Kanal M, Cao Z, Wright C, Gu G. Neurog3 gene dosage regulates allocation of endocrine and exocrine cell fates in the developing mouse pancreas. Developmental biology. 2010;339:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman WW, Fickett JW. Identification of regulatory regions which confer muscle-specific gene expression. Journal of molecular biology. 1998;278:167–181. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JA, Viswanathan SR, Yabuuchi A, Cunniff K, Takeuchi A, Park I-HH, Sero JE, Zhu H, Perez-Atayde A, Frazier AL, et al. A role for Lin28 in primordial germ-cell development and germ-cell malignancy. Nature. 2009;460:909–913. doi: 10.1038/nature08210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaron O, Farhy C, Marquardt T, Applebury M, Ashery-Padan R. Notch1 functions to suppress cone-photoreceptor fate specification in the developing mouse retina. Development (Cambridge, England) 2006;133:1367–1378. doi: 10.1242/dev.02311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. Cell differentiation in the retina of the mouse. The Anatomical record. 1985a;212:199–205. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092120215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. Cell proliferation during postnatal development of the retina in the mouse. Brain research. 1985b;353:229–239. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Stokes N, Polak L, Fuchs E. Specific microRNAs are preferentially expressed by skin stem cells to balance self-renewal and early lineage commitment. Cell stem cell. 2011;8:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.