Abstract

Distressed parents (N = 85) with a substance-abusing adolescent not receiving treatment were randomized to 12 weeks of coping skill training (CST), 12-step facilitation (TSF), or delayed treatment control (DTC). At the end of treatment/delay, CST showed greater coping skillfulness than TSF, and both CST and TSF were more skillful than DTC. The percentage of parent problem days (PPD)—days when the adolescent’s substance use caused a problem—also was reduced in CST and TSF, relative to DTC. Both CST and TSF reported significantly reduced monthly PPD by the end of a 12-month follow-up. Skill training and TSF interventions appear equally effective for this underserved parent population.

Keywords: substance-abusing adolescents, parents, parenting, coping skill training, drug abuse

1. Introduction

Poor communication skills, excessive conflict, and low parental monitoring are often present in families affected by adolescent substance abuse (e.g., Barnes, Reifman, Farrell, & Dintcheff, 2000; Dishion, Patterson, & Reid, 1988; Tobler & Komro, 2010; van der Vorst, Engels, Meeus, Dekovic, & Vermulst, 2006; Walden, McGue, Iocano, Burt, & Elkins, 2004). Although parenting deficits may lead to adolescent substance use (e.g., Steinglass, Bennett, Wolin, & Reiss, 1987), poor parenting can also be the result of stress brought on by the adolescent’s use, itself (e.g., Hobfoll & Spielberger, 1992; Kerr & Stattin, 2002; McGillicuddy, Rychtarik, & Morsheimer, 2004; Stice & Barrera, 1995). Parent skills training to deal more effectively with teen substance use may help reduce parental distress, and improve parenting.

Few studies have examined the impact of teaching new skills to parents of substance-abusing adolescents; the typical focus of this research has been to teach them skills to support teen abstinence during and following treatment (e.g., Toumbourou, 1994; Williams & Chang, 2000). These efforts have helped reduce relapse (e.g., Bry, 1988; Stanton & Shadish, 1997; Williams & Chang, 2000), with adolescents citing family support as instrumental in their success at abstaining (e.g., Brown, Monti, Myers, Waldron, & Wagner, 1999). However, there has been little emphasis on teaching skills to improve the parents’ own functioning, or to assess parent outcomes (e.g., Joaning, Quinn, Thomas, & Mullen, 1992; Smith, Sells, Rodman, & Reynolds, 2006). In addition, few studies monitor parent behavior change from pretreatment to posttreatment, or utilize a comparison or control group (e.g., Schmidt, Liddle, & Dakof, 1996). Overall, these studies have been limited with regard to the precise skills parents are learning, the measurement of these skills, and how they are incorporated into parent training programs.

Even fewer studies have focused on parents of substance-abusing teens not in treatment, an important group as fewer than 10% of teens in need of substance abuse treatment receive it (SAMHSA, 2013). Toumbourou, Blyth, Bamberg, and Forer (2001) in a small, unrandomized study, developed and examined a parent-only intervention, designed to increase parenting assertiveness, and to reduce focus on the adolescent. Compared to those on a waitlist, recipients of the intervention demonstrated improved mental health, and increased use of assertive parenting. McGillicuddy, Rychtarik, Duquette, & Morsheimer (2001) conducted a pilot (n=22) examining the efficacy of coping skill training (CST) for parents of a substance-abusing adolescent not receiving treatment. At pretreatment assessment, parents were administered the Parent Situation Inventory (PSI; see McGillicuddy et al., 2004), a roleplay measure of coping in parents of adolescent substance abusers, and randomly assigned to CST or delayed treatment. At the end of the 8-week treatment/delay, participants were administered the alternate PSI form. Parents receiving CST improved significantly from pretreatment to posttreatment on PSI skill relative to parents whose treatment was delayed. In addition, moderate-to-large between group effects favoring CST were found on measures of parent functioning and teen marijuana use. Though results of these interventions appear promising, additional research is needed to compare them with alternate treatment models, and to addresses methodological limitations noted above.

1.1 Study Goals

The current study begins to address the above needs by comparing the CST developed in McGillicuddy et al. (2001), with a conceptually distinct Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) condition, and a Delayed Treatment Control (DTC). Both CST and TSF were group-based, and had the common goals of improving the parent’s adolescent-related stress, and reducing the frequency of problems experienced by the parents due to the adolescent’s substance use. The study addressed the following specific questions: (a) what is the relative efficacy of the treatment conditions on parental coping skills, parent treatment/self-help meeting attendance, parental stress, and adolescent substance abuse-related problems experienced by the parent at the end of a 12-week treatment/delay period?; and (b) what is the relative effectiveness of CST and TSF on parental stress and adolescent substance abuse-related problems across a 12-month posttreatment followup?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

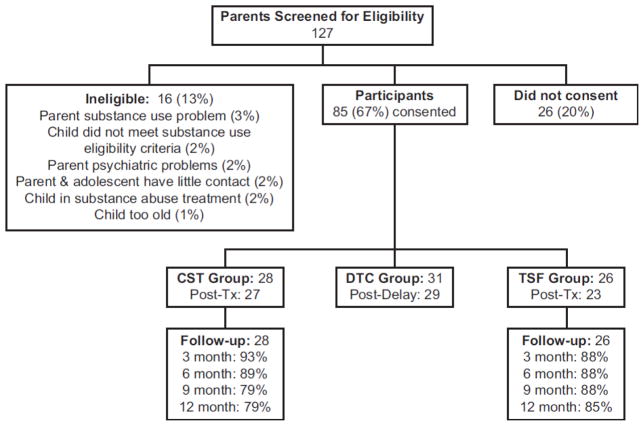

Participants were 85 parents of substance-abusing adolescents recruited over a 32-month period in response to media advertisements offering a free program for parents experiencing stress due to their adolescent’s use of alcohol and/or illicit drugs. To be eligible, individuals had to (a) be a parent or guardian of a substance-abusing adolescent (ages 12–21), (b) have lived with the adolescent for at least 28 of the previous 90 days, (c) be free of a substance use disorder of their own as defined by a score < 8 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, De la Fuente, Saunders, & Grant, 1989) and < 4 on the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Skinner, 1982), (d) report that the adolescent had used alcohol or illicit drugs within the past three months, and had not attended formal treatment, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), or Narcotics Anonymous (NA) within the past month, and (f) report that the adolescent had used substances ten or more times in the past year, scored ≥ 30 on a parent-administered version of the problem severity subscale of the Personal Experience Screen Questionnaire (PESQ; Winters, 1992), or scored ≥ 7 on the substance abuse subscale of the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Parents (POSIP; Rahdert, 1991)1. See Figure 1 for participant flow and followup. In 66 (78%) families, one parent participated; two parents participated in the remainder of families. Among the latter families, both parents received treatment together, but were interviewed separately during clinical screen and research assessments. Analyses presented in this report were conducted only on scores of the parent who reported spending more time with the teen2. Participating parents were predominantly female (85% of sample); on average, the substance-abusing adolescent was 16.51 (1.65) years of age. Additional characteristics of the final sample are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Subject flow and attrition.

Table 1.

Participant Pretreatment Characteristics by Treatment Condition

| Treatment Condition | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Coping Skill Training (n = 28) | 12-Step Facilitation (n =26) | Delayed Treatment Control (n = 31) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Characteristic | % | M | SD | % | M | SD | % | M | SD |

| Age | 44.50 | 5.44 | 46.31 | 6.07 | 44.23 | 5.10 | |||

| Racial/Ethnic Status (% White) | 75 | 73 | 77 | ||||||

| Married (%) | 46 | 50 | 36 | ||||||

| PSI Coping Skill Levela | 3.01 | .31 | 3.18 | .31 | 3.12 | .36 | |||

| Participant Depressionb* | 13.61a | 10.19 | 8.33b | 7.18 | 15.18a | 9.31 | |||

| Participant Parenting Stressc | 131.81 | 19.28 | 131.54 | 23.22 | 135.39 | 22.02 | |||

| Parent Previous Help (%)d | 54 | 69 | 61 | ||||||

| Parent Self-Help Dayse | 11.93 | 33.49 | 11.38 | 30.88 | 4.26 | 6.90 | |||

| Adolescent PESQf | 44.46 | 9.88 | 41.00 | 9.83 | 44.90 | 7.51 | |||

| Adolescent POSIPg | 9.89 | 3.65 | 9.77 | 3.35 | 10.23 | 3.63 | |||

| Adolescent Gender (% Female) h | 18 | 27 | 29 | ||||||

| Parent problem Days (%) i | 22 | 35 | 12 | 24 | 27 | 31 | |||

| Adolescent Previous Lifetime Treatmentj | 39 | 38 | 29 | ||||||

| Adolescent Treatment Days (Past Year)k | 4.21 | 12.84 | 6.58 | 16.53 | .71 | 11.99 | |||

Note: Values with different subscripts are significantly different from one another;

p<.05.

Mean situation skillfulness score (1 = Least Skillful; 6 = Most Skillful) on the Parent Situation Inventory;

Beck Depression Inventory-II;

Stress Index for Parents of Adolescents-Adolescent Stress Domain;

Parent report of ever receiving help (i.e., Al-Anon, Nar-Anon, Toughlove, Parent Anonymous, Private Therapist, Structured Parent Program) for adolescent’s substance use;

Number of days parent attended a help session related to adolescent’s substance abuse in past year;

Personal Experience Screen Questionnaire (applied to adolescent);

Problem-Oriented Screening Instrument for Parents, Substance Abuse Subscale;

Based on Parent Report;

Percentage of days that adolescent’s substance use caused a problem for the parent, over previous 180 days;

Parent report of adolescent ever receiving formal treatment for substance use;

Parent report of number of days adolescent attended a treatment session in the past year.

2.2. Design and Procedure

A 3-group (Coping Skill Training [CST], Twelve Step Facilitation [TSF], or Delayed Treatment Control [DTC]) design was used.3 On consenting to participate, and completing a pretreatment assessment, individuals meeting eligibility criteria were assigned to the next available cohort (i.e., therapy group). Once 3–6 participants were assigned to a cohort, it was deemed full. To avoid lengthy delays waiting for the start of treatment, cohort size varied depending on the availability of eligible participants. Once full, a cohort was randomized to treatment condition, with the provision that each condition occur twice within a consecutive set of 6 cohorts. The cohort then participated in 12 weeks of the assigned condition. Overall, 21 cohorts were randomized (seven cohorts in each treatment condition). Following completion of the initial 12-week period, participants were administered a set of measures similar to that administered at pretreatment. Participants also received telephone assessments 3 and 9 months, and in-person interviews at 6 and 12-month following the initial 12-week period. Staff blind to treatment assignment conducted all 12-week and follow-up assessments.

2.3. Treatment Conditions

2.3.1. Coping Skill Training (CST)

Parents in CST were scheduled for 12, 2-hour group sessions. In CST they were taught to view their problems from a family stress and coping model, which posits that parental distress results from cumulative problems brought on by adolescent substance use, and the ineffectiveness of how the parent responds to it. Parents were instructed and trained in the use of more effective coping skills. Each session focused on applying a problem-solving approach (see D’Zurilla & Goldfried, 1971) to situations derived from the PSI (McGillicuddy et al., 2004). The PSI is comprised of 28 problem situation vignettes commonly encountered by parents of substance-abusing adolescents (e.g., situations dealing with school problems, legal problems, etc). For each situation, the therapist led the group in problem solving, and provided empirically-derived, situation-specific skill hints adapted from response components judged as highly effective during PSI development (McGillicuddy et al., 2001). During the initial sessions, the therapist modeled the response, coached group members as they role-played the response, and provided feedback. In later sessions, therapist modeling and coaching ended as participants assumed increased responsibility for developing responses. Participants were neither encouraged nor discouraged from attending 12 step meetings, but were taught to view such meeting attendance as a problem-solving option.

2.3.2. Twelve Step Facilitation (TSF)

Parents in TSF also were scheduled for 12, 2-hour group sessions. In these sessions, participants were taught to view their problem as one of codependence, with the 12 steps of Nar-Anon serving as a blueprint to facilitate their recovery. Codependence was defined as a preoccupation with, and extreme social and emotional dependence on another person (in this case, the substance-abusing adolescent; Wegscheider-Cruse, 1989). Participants learned codependence symptoms (e.g., denial, self-delusion), its consequences (e.g., low self-worth), and the 12 steps. Sessions focused on Steps 1–5, enabling behaviors and detachment, codependence relapse, and an overview of Steps 6–12. To control for PSI exposure, parents were presented with the same problem situations in the same order as parents receiving CST. In TSF, however, the situations were used to discuss codependence and detachment, what was manageable and unmanageable, and the 12 steps. Although the therapist provided information regarding general parenting (e.g., be consistent) and how to live a 12-Step type of life (i.e., cease co-dependent behavior), the therapist avoided instruction of effective and ineffective behaviors, and took the approach advocated in most 12-step programs that it can be harmful to advise another how they should behave in any given situation. Participants were encouraged to become linked with a 12 Step group, provided information regarding 12 step meetings in the area, and assigned between-session, twelve-step reading material.

2.3.3. Delayed Treatment Control (DTC)

Parents in DTC had treatment delayed for 12 weeks, during which time they had no contact with project staff.

2.4. Therapists

Five experienced certified counselors served as therapists; they received 30 hours of training in both CST and TSF, and were randomly assigned to treatment group with the provision that each conduct an approximately equal number of CST and TSF groups. Treatments were fully manualized, sessions were recorded, and therapists received weekly feedback. A supervisor subsequently rated a random 25% sample of each therapist’s tapes for compliance with a checklist of critical session elements; a 25% subsample of these then were independently rated by a second rater. The inter-rater reliability was ICC = .98 for both CST and TSF. Mean therapist compliance was 87% and 92% for CST and TSF, respectively.

2.5. Measures

Four primary measures (i.e., parent skillfulness, parent meeting attendance, parent stress, and the percentage of days the parent had a problem due to the adolescent’s substance abuse were examined. Parent skillfulness was measured using the alternate forms of the Parent Situation Inventory (PSI), a situational role-play measure of parent skill in dealing with substance use-related adolescent problem situations; McGillicuddy et al. (2004) found generalizability coefficients of .80 for each PSI form, alternate form reliability of .76, and negative associations between adolescent alcohol use and PSI score. In the current study, one PSI form was administered at pretreatment; the alternate PSI form was administered at all remaining in-person assessments. As each PSI situation is administered, parents indicate what they would say and/or do if it were occurring right then. The role-played response to each situation was recorded and subsequently scored for effectiveness on a 6-point scale (1 = not effective at all; 6 = extremely effective). The mean PSI situation effectiveness score served as the measure of parent skillfulness. A primary rater blind to treatment condition and assessment period scored 73% of the PSI assessments. A second rater, also blind to treatment condition and assessment period, scored the remainder. Fourteen percent of the assessments scored by the primary rater were selected randomly to be scored by the second rater; the inter-rater ICC was .90.

Parent meeting attendance was assessed via self-report. At each assessment, parents were asked to report their attendance at professional treatment and 12 step meetings related to their adolescent’s substance use. Attendance data were highly skewed due to a large percentage of parents who had not attended a meeting, resulting in it being dichotomized into a binary variable (0 = No Meeting Attendance; 1 = Meeting Attendance). Parent stress was measured with the Adolescent Domain subscale of the Stress Index for Parents of Adolescents (SIPA-AD; Sheras, Abidin, & Konold, 1998), which assesses stress that results from the adolescent’s problems (range 63–200). The measure, administered at pretreatment, posttreatment, and 6 and 12 monht follow-ups, has high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and discriminant validity (i.e., between clinical and normative samples). Scores are categorized as clinically severe (132–200), clinically significant (121–131), borderline (112–120), and normal (< 112). The frequency of problems brought on by the adolescent was measured using the timeline-followback interview (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) at each assessment. For each day of the period, the parent reported whether the adolescent’s substance use caused a problem for them. The percentage of days in each 30-day period served as the measure of parent problem days (PPD).4

2.6. Treatment Expectancies and Treatment Received

Participants completed a 6-item “Feelings About Your Scheduled Treatment” scale (coefficient alpha = .89) at the end of the first session. Parents rated their treatment along a 10-point continuum (1 = Not at all; 10 = Extremely) with respect to its reasonableness, anticipated helpfulness, whether they would recommend it to others, its similarity to what was expected, the anticipated ease of participating, and their overall satisfaction with the treatment as scheduled. Overall, expectancies were high, and did not differ between treatments (CST: M = 8.24, SD = 1.02; TSF: M = 7.76, SD = 1.55). On average, participants attended 65% of their scheduled sessions (CST = 67%; TSF = 64%), comparing favorably to participation rates commonly found in parent training programs (e.g., DeGarmo, Patterson, & Forgatch, 2004).

2.7. Data Analysis

To reduce skew, an arcsine transformation was used for PPD. Outlying observations on measures were examined using the outlier labeling rule (Hoaglin & Iglewicz, 1987; g = 2.2); identified outliers then were accommodated using a modified winsorization procedure (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Preliminary analyses found that participants assigned to TSF had lower baseline Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck et al. 1996) scores than those assigned to either DTC or CST F(2,80) = 4.38, p < .05. Hence, all analyses controlled for baseline BDI. Missing data at the 12-week assessment were imputed using two-level multiple imputation (Mistler, 2013). Missing data from Weeks 12–64 were not imputed, and included all subjects with at least one data follow-up point. Treatment effects at the end of the 12-week posttreatment period were examined in a two-level mixed effects model with treatment condition as a fixed effect, cohort as a random effect (nested within treatment condition), and person a random effect (nested within cohort and treatment). Main effects for Treatment, Time, and the Treatment × Time interaction across the three assessment time points for the SIPA-AD, or the twelve, 30-day periods for PPD were examined in a three-level, mixed effects model that assumed random intercepts and random linear time slopes. The pretreatment value of the dependent variable served as a covariate. SAS PROC MIXED was used for analysis of continuous outcomes; SAS PROC GLIMMIX was used for binary outcomes. SAS PROC MIANALYZE was used to pool imputed data set results for the 12-week/posttreatment assessment. Treatment effects at 12-weeks were probed with two-tailed t tests of pairwise differences between adjusted least squares means. Between condition and within condition standardized mean differences, d, for continuous and binary variables were calculated using the framework provided by Feingold (2013) and Chinn (2000), respectively. All analyses used the intent-to-treat sample.

3. Results

3.1. Primary outcomes at 12-week posttreatment/delay point

3.1.1. What were the effects of treatment condition on parent coping skills and parent treatment/self-help meeting attendance?

As shown in Table 2, CST parents were significantly more skillful on the PSI at the end of the 12-weeks than those in either TSF or DTC. Within condition, this difference was reflected a large increase (d = 1.39) in CST, a moderate (d = .58) increase in TSF, and a small (d = −.12) decrease in DTC. Participants in TSF, however, had a greater probability of attending a self-help meeting than they would have if assigned to either CST, or DTC. Despite large-to-medium differences between conditions (see Table 2), however, the differences in predicted probabilities only approached significance, likely owing to the relatively small sample sizes for these less-powerful, binary analyses.

Table 2.

Imputed Least Square Means and Predicted Probabilities, Main Effect Tests, Effect Size of Individual Planned Comparisons on Parent Skillfulness, Treatment/Self-Help Meeting Attendance, Parent Stress, and Percentage of Parent Problem Days at the End of the 12 Week Period (N = 85).

| Treatment Condition | Main Effect Test | d {95% CI} | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CST | TSF | DTC | F (df) | p | CST–TSF | CST-DTC | TSF-DTC | ||||

| n = 28 | n= 26 | n=31 | |||||||||

| Measure | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | |||||

| PSI | 3.56 | .07 | 3.29 | .07 | 3.06 | .06 | 20.19 (2,16.77) | <.0001 | .81a {.17, 1.44} | 1.50b {.92, 2.09} | .70c {.08, 1.31} |

| Treatment/Self-help meeting attendance (probability) | .03 | .04 | .30 | .15 | .14 | .09 | 3.35 (2,14.17) | .06 | −1.36d {−2.86, .14) | −.82e {−2.29, .64) | .54f {−.65, 1.72} |

| SIPA-AD | 122.07 | 3.72 | 123.41 | 3.98 | 130.62 | 3.52 | 2.23 (2,14.40) | .14 | −.06g {−.61, .49} | −.40h {−91, .11) | −.34i {−.89, .20} |

| PPD | 3.32 | .33 | 3.10 | .42 | 19.24 | .67 | 5.89 (2, 15.91) | .01 | .01j {−.51, .54] | −.59k {−1.14, −.07} | −.60l {−1.14, −.07] |

Note: CST= Coping Skill Training; TSF = Twelve-Step Facilitation; DTC = Delayed Treatment Control; d = standardized mean difference (effect size); CI = confidence interval; aPSI = Parent Situation Inventory skillfulness score; Treatment/Self-help meetings = predicted probability of a “typical” subject within a condition attending a self-help meeting related to their adolescent’s substance use; probabilities were derived using the inverse link function applied to the estimated link logit for each condition; SIPA-AD = Stress Index for Parents of Adolescents, Adolescent Domain Subscale score; PPD = Percentage of Parent Problem days arcsine retransformed in the last 30 days of the treatment period. Superscripts refer to individual paired comparison t-test results. Analyses controlled for the pretreatment value of the dependent variable and participant pretreatment depression, and were conducted in a two-level, mixed effects model with treatment cohorts (treatment groups) nested within treatment condition. Means presented are predicted least square means; for analyses, PPD was arcsine transformed; PPD means presented are retransformed least square means with bootstrapped SEs.

t (16.77) = 2.69, p = .02;

t (16.87) = 5.41, p < .0001;

t (17.22) = 2.39, p = .03;

t (14.17) = −1.96, p = .07.

t (14.23) = −1.27, n.s.;

t (15.07) = .97, n.s.;

t (14.40) = −.24, n.s.;

t (14.77) = −1.68, n.s.;

t (14.69) = −1.33, n.s.;

t (15.98) = .06, n.s.;

t (16) = −2.59, p = .02;

t (15.91) = −2.40, p = .03.

3.1.2. What were the effects of treatment condition on parent stress, and percentage of parent problem days (PPD)?

CST, TSF, and DTC did not differ significantly on parental stress at the end of treatment (see Table 2). Nevertheless, within condition, CST and TSF each showed moderate reductions (d = −.51 and −.47, respectively) in stress, while little change was noted in DTC (d = −.09). Due likely to the relatively modest levels of change, and the relatively small sample size, however, no significant differences were observed between conditions. The percentage of PPD was significantly lower in CST and TSF than in DTC, but CST and TSF did not differ from one another (see Table 3). Moderate, and nearly identical reductions in PPD were observed within both CST (d = −.61) and TSF (d = −.61) from the month before treatment to the last month of the treatment period, while only a small reduction in PPD was observed in DTC (d = −.02).

Table 3.

Results of Analyses of Parental Stress and Percentage of Parent Problem Days Across Followup.

| Treatment Condition | Effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| CST | TSF | F | df | p | ||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| n = 28 | n= 26 | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Measure | M | SE | M | SE | ||||

|

|

||||||||

| SIPA-AD | 121.93 | 3.11 | 121.60 | 3.15 | ||||

| Treatment | .01 | 1, 40.7 | .94 | |||||

| Time | .31 | 1. 42.1 | .58 | |||||

| Treatment × Time | .10 | 1, 40.7 | .75 | |||||

| PPD | 4.78 | .37 | 3.39 | .42 | ||||

| Treatment | .56 | 1, 8.44 | .47 | |||||

| Time | .82 | 1, 77.3 | .37 | |||||

| Time2 | 10.05 | 1, 455 | .002 | |||||

| Time × Time | .07 | 1, 12.1 | .80 | |||||

| Treatment × Time2 | 1.25 | 1, 454 | .26 | |||||

Note: CST = Coping Skills Training; TSF = Twelve-Step Facilitation; SIPA-AD = Stress Index for Parents of Adolescents, Adolescent Domain Subscale score; PPD = Percentage of Parent Problem days per 30-day followup interval. Analyses are the results of three-level mixed effects models controlling for pretreatment depression and the pretreatment value of the dependent variable. SIPA-AD analysis is based on three time points: posttreatment (week12 of treatment), 6 months, and 12 months posttreatment; PPD analysis is based on twelve, arcsine transformed values across the twelve, 30-day intervals; means for SIPA-AD are predicted least square means at the mid-point (6 months) of the follow-up period; PPD means are the retransformed least square 30-day means, with bootstrapped SEs, at the midpoint of the follow-up period.

3.2. 12-month followup outcomes

3.2.1. What were the effects of CST and TSF on parental stress and PPD?

CST and TSF did not differ significantly in parental stress over the follow-up period (see Table 3). Posttreatment reductions in parental stress were maintained across follow-up, with no significant difference between treatments, and no significant effect of Time, or a Treatment × Time interaction. Overall, by Month 12, parents, on average, showed a near moderate decrease in stress, d = −.48 and −.48 in CST, and TSF, respectively.

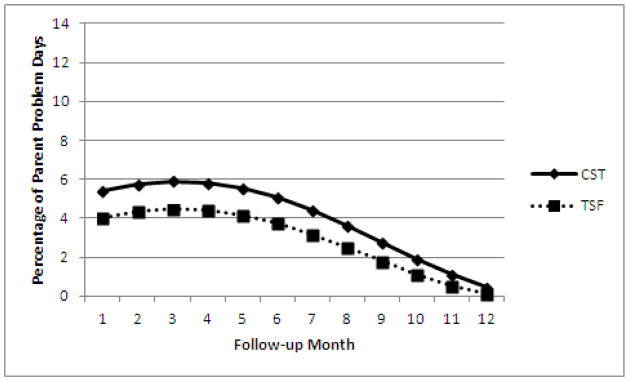

CST and TSF did not differ significantly in PPD across follow-up (see Table 3). However, a significant quadratic time effect emerged. As shown in Figure 2, treatments showed a very small, nonsignificant increase in PPD from Month 1 to Month 3 (d = .03). At Month 4, however, this trend reversed, and PPD began to decline at an increasingly high rate. By the end of the follow-up period, PPD had reduced to near zero in both conditions (Month 3 to Month 12 d = −.62). This effect did not vary by treatment group, or PPD pretreatment level. The results also do not appear attributable to an increase in the adolescent’s involvement in treatment by the end of and during followup. Treatment involvement was low, with estimated predicted probabilities of the adolescent attending treatment of .02 and .06 in CST and TSF, respectively. These did not differ between treatments, F(1,12) = .85, n.s., nor was there any effect of linear Time, F(1,8)= .03, n.s., or quadratic, F (1,128) = 1.01, n.s., time.

Figure 2.

Quadratic Time effect on percentage of parent problem days. Data points are arcsine retransformed.

4. Discussion

CST and TSF each resulted in moderate improvements in parent functioning, and reduced days of adolescent substance abuse-related problems for the parent. Further, these reductions appeared to be clinically relevant. Parent stress reduced from the clinically severe to the lower portion of the clinically-significant range—a change that remained stable through the 12-month follow-up. Moreover, by the end of follow-up, PPD was very near zero in both CST and TSF conditions. The reduction in problems is noteworthy given that few of the adolescents were involved in treatment. The finding highlights the fact that involvement of the adolescent in treatment may not be a necessary condition for change in some individuals. It also is noteworthy, however, that while PPD reduced to near zero, parent stress levels, while reduced, remained in the clinically significant range. PPD was specific to the adolescent’s substance use, while the SIPA-AD applied to general adolescent-derived parent stress. So, while problems related to the adolescent’s substance use appear to have been markedly reduced, parents still could have been experiencing notable stress from other adolescent-related problems. Incorporating these interventions into more general parent skill training programs may be a promising area of study. Each intervention, compared to the delayed treatment control, resulted in improved parenting skills, with parents receiving CST also being more skillful than parents in TSF. These findings suggest that CST and TSF were both effective, as parents improved their skillfulness after treatment. Anticipated differences between conditions in professional/self-help meeting attendance also emerged, but were not significant. Larger samples are needed to assess the extent to which outcomes in CST and TSF are attributable to their putative mechanisms of change (i.e., skill acquisition and self-help meeting attendance, respectively).

The results of this study are tempered by the small sample size. Reaching this nontreatment population is a challenge. Anecdotally, the investigators found that parents in this group often were reluctant to participate, either due to time constraints, or concerns that doing so could blemish their adolescent’s future, or cast a poor light on their parenting. This reluctance is evident in the subject flow, in which nearly three years were required to recruit 85 eligible parents, despite relatively heavy media advertising and outreach efforts. Alternate, less intrusive administration formats, such as web-based parent programs, may be able to reach more parents. Other study limitations also should be noted. First, although parents may have responded differently to their adolescent’s substance use dependent on the child’s age (which was 12–21 in this study), our small sample prevented us from examining age-related differences. Second, PPD may have limitations, if viewed as a proxy for adolescent substance abuse. For example, it is not clear that the reduction in PPD reflects an actual reduction in problems caused by the adolescent’s substance use, a reduction in the adolescent’s actual substance use, or possibly a change in the parents’ perception of what a problem is. With respect to the latter, however, the interventions did aim to reduce, to a manageable level, the emotional valence of some problems, but did not teach parents to deny problems existed. Regardless, the relationship of PPD to adolescent substance use needs further clarification, and the ethical and methodological challenges of obtaining direct adolescent reports in this line of research need to be explored. Third, due to the nontreatment nature of the population, the percentage of pretreatment problem days reported by participants was relatively low—perhaps creating a floor effect that might have prevented detection of treatment differences. Though this lower-severity group of adolescents and their parents are a larger, often undetected and underserved group, study of these interventions with parents of more severely impaired adolescents is needed.

To summarize, this study is one of the first attempts to examine the relative impact of two distinct interventions for parents of substance-abusing adolescents not receiving treatment. Findings suggest that parent interventions can markedly reduce parent problems experienced as a result of the adolescent’s substance use, and reduce adolescent-related parent stress. Future research needs to examine alternate administration formats, obtain larger sample sizes so as to examine each treatment’s putative mediating mechanisms, study moderators of treatment effects, and extend the work to parents whose substance-abusing adolescent is receiving treatment.

Highlights.

Parents of substance abusing adolescents who received 12 weeks of coping skills training (CST) showed more skillfulness in dealing with the adolescent’s substance use than did parents receiving Twelve Step Facilitation (TSF).

Parents in both CST and TSF were more skillful than parents who were in a wait list control condition.

The percentage of parent problem days (PPD)—days when the adolescent’s substance use caused a problem—also was reduced in CST and TSF, relative to wait list control.

Acknowledgments

Neil B. McGillicuddy, and Robert G. Rychtarik, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. George D. Papandonatos, Brown University.

This research was funded by grant DA09581 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). We thank Joan Duquette for her assistance in drafting the TSF treatment manual, and for supervising the talented team of project therapists. We also thank Kate Kavanagh from the Child and Family Center, University of Oregon-Portland, and Patricia Owen from the Hazelden Foundtation, who reviewed and provided useful feedback on the CST and TSF manuals, respectively. We also thank Bethanne Bossler-Kogut and Michelle Burke-Storer for their day-to-day handling of the project.

Footnotes

100% of the participants reported the adolescent used substances on at least 10 occasions over the past year, 91% achieved a PESQ score ≥ 30, and 77% achieved a POSIP score ≥ 7. PESQ scores and POSIP scores were highly correlated (Pearson r = .72). Only one parent failed to meet study eligibility based on either PESQ or POSIP score. Analyses conducted without the data of this one parent did not change any of the study’s findings.

The mother’s data was used for 13 families; the father’s data was used for six families.

A second factor, Parent Situation Inventory (PSI) form (McGillicuddy et al., 2004), to which cohorts were randomized and on which they were initially assessed and exposed during treatment, also was included in the design. However, preliminary analyses found no significant PSI form or PSI form × Treatment interaction on any variables. Thus, to simplify analyses and reporting, we collapse across PSI form.

Parents also were asked to report on the adolescent’s level of substance use, but many (slightly less than 50%), particularly at follow-up, reported being unable to provide any estimate. This resulted in a fairly large amount of missing. Because of the unreliability caused by high amounts of missing data, we chose to not report it.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1989. (WHO Publication No. 89.4) [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G, Reifman AS, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. The effects of parenting on the development of alcohol misuse: A six-wave latent growth model. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory--II (BDI-II) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Monti PM, Myers MG, Waldron HB, Wagner EF. More resources, treatment needed for adolescent substance abuse. The Brown University Digest of Addiction Theory and Application. 1999;18(11):6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bry BH. Family-based approaches to reducing adolescent substance use: Theories, techniques, and findings. In: Rahdert ER, Grabowski J, editors. Adolescent drug abuse: Analyses of treatment research. Washington, D.C: Supt. Of Docs., U.S. Government Printing Office; 1988. pp. 39–68. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph 77. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM) 88–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2000;19:3127–3131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. How do outcomes in a specified parent training intervention maintain or wane over time. Prevention Science. 2004;5:73–89. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000023078.30191.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Reid JR. Parent and peer factors associated with drug sampling in early adolescence: Implications for treatment. In: Rahdert ER, Grabowski J, editors. Adolescent drug abuse: Analyses of treatment research. Washington, D.C: Supt. Of Docs., U.S. Government Printing Office; 1988. pp. 69–93. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph 77. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM) 88–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ, Goldfried MR. Problem solving and behavior modification. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1971;78:107–126. doi: 10.1037/h0031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoaglin DC, Iglewicz B. Fine tuning some resistant rules for outlier labeling. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1987;82:1147–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Spielberger CD. Family stress: Integrating theory and measurement. Journal of Family Psychology. 1992;6:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children’s Influence on Family Dynamics: The Neglected Side of Family Relationships. Mahweh, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy NB, Rychtarik RG, Duquette JA, Morsheimer ET. Development of a skill training program for parents of substance-abusing adolescents. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;20:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy NB, Rychtarik RG, Morsheimer ET. The Parent Situation Inventory (PSI): A role-play measure of coping in parents of substance-using adolescents. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:386–390. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistler SA. A SAS® macro for applying multiple imputation to mulitlevel data. proceedings of the SAS Global Forum; 2013; San Francisco, CA. 2013. pp. 440–2013. Contributed paper (Statistics and data analysis) [Google Scholar]

- Rahdert ER. The adolescent assessment/referral system manual. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1991. (DHHS Publication No. ADM91-1735) [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt SE, Liddle HA, Dakof GA. Changes in parenting practices and adolescent drug abuse during multidimensional family therapy. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sheras PL, Abidin RR, Konold TR. Stress Index for Parents of Adolescents: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Sells SP, Rodman J, Reynolds LR. Reducing adolescent substance abuse and delinquency: Pilot research of a family-oriented psychoeducation curriculum. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2006;15:105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MD, Shadish WR. Outcome, attrition, and family-couples treatment for drug abuse: A meta-analysis and review of the controlled, comparative studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:170–191. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass P, Bennett L, Wolin S, Reiss D. The Alcoholic Family. New York: Basic Books; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stice EM, Barrera M., Jr A longitudinal examination of the reciprocal effects between perceived parenting and adolescents’ substance use and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2012 National survey on drug use and health: National findings (Office of Applied Studies H-46, DHHS Publication No. SMA 13–4795) Rockville, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick GG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler AL, Komro KA. Trajectories of parental monitoring and communication and effects on drug use among urban young adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:560–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toumbourou JW. Family involvement in illicit drug treatment? Drug and Alcohol Review. 1994;13:385–392. doi: 10.1080/09595239400185511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toumbourou JW, Blyth A, Bamberg J, Forer D. Early impact of the BEST intervention for parents stressed by adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology. 2001;11:291–304. [Google Scholar]

- van der Vorst H, Engels CME, Meeus W, Dekovic M, Vermulst A. Parental attachment, parental control, and early development of alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:107–116. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden B, McGue M, Iocano WG, Burt SA, Elkins I. Identifying shared environmental contributions to early substance use: The respective roles of peers and parents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:440–450. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegscheider-Cruse S. Another Chance: Hope and Health for the Coalcoholic Family. 2. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books, Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Williams RJ, Chang SY. A comprehensive and comparative review of adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7:138–166. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC. Development of an adolescent and other drug abuse screening scale: Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17:479–490. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90008-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]