SUMMARY

The two principal movement-suppressing pathways of the basal ganglia, the so-called hyperdirect and indirect pathways interact within the subthalamic nucleus (STN). An appropriate level and pattern of hyperdirect pathway cortical excitation and indirect pathway external globus pallidus (GPe) inhibition of the STN are critical for normal movement and greatly perturbed in Parkinson’s disease. Here, we demonstrate that motor cortical inputs to the STN heterosynaptically regulate through activation of postsynaptic NMDA receptors the number of functional GABAA receptor-mediated GPe-STN inputs. Thus, a homeostatic mechanism, intrinsic to the STN, balances cortical excitation by adjusting the strength of GPe inhibition. However, following loss of dopamine, excessive cortical activation of STN NMDA receptors triggers GPe-STN inputs to strengthen abnormally, contributing to the emergence of pathological, correlated activity.

INTRODUCTION

The basal ganglia are a group of subcortical brain nuclei critical for voluntary movement and the primary site of dysfunction in movement disorders like Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Albin et al., 1989; Galvan and Wichmann, 2008; Hammond et al., 2007; Kravitz et al., 2010). Cortical excitation of the basal ganglia is processed via the direct, hyperdirect and indirect pathways (Nambu et al., 2002; Smith et al., 1998), the relative activities of which are dynamically regulated by dopaminergic transmission (Albin et al., 1989; Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011). Direct pathway activity promotes movement through inhibition of GABAergic basal ganglia output (Chevalier et al., 1990; Hikosaka et al., 2000; Kravitz et al., 2010), whereas the hyperdirect and indirect pathways suppress movement through elevation of basal ganglia output (Baunez et al., 1995; Kravitz et al., 2010; Maurice et al., 1999; Tachibana et al., 2008). The hyperdirect pathway conveys cortical excitation to basal ganglia output nuclei via the glutamatergic subthalamic nucleus (STN) (Maurice et al., 1999; Tachibana et al., 2008) and thus mediates a rapid stop/pause signal prior to direct pathway inhibition (Baunez et al, 1995; Nambu et al., 2002; Mink and Thach, 1993). The indirect pathway, which traverses the striatum, GABAergic external globus pallidus (GPe) and STN, more slowly elevates basal ganglia output and thus terminates movements selected by the direct pathway (Albin et al., 1989; Kravitz et al., 2010; Maurice et al., 1999; Mink and Thach, 1993; Tachibana et al., 2008). In idiopathic and experimental PD, an increase in hyperdirect/indirect pathway activity and abnormally correlated hyperdirect/indirect pathway activity contribute to motor dysfunction (Albin et al., 1989; Galvan and Wichmann, 2008; Hammond et al., 2007; Jenkinson and Brown, 2011; Kravitz et al., 2010).

The intersection of the hyperdirect and indirect pathways argues that the STN is a key locus of interaction. Indeed, GPe inhibition acting at GABAA receptors (GABAARs) potently shunts/limits coincident cortical excitation of the STN (Atherton et al., 2010; Fujimoto and Kita, 1993; Maurice et al., 1998) but promotes cortical patterning if it is offset in phase to cortical excitation (Baufreton et al., 2005; Mallet et al., 2008a, 2012; Paz et al., 2005). This promotion of cortical patterning is due to both disinhibition and increased availability of postsynaptic Nav and Cav channels post-inhibition (Baufreton et al., 2005; Hallworth and Bevan, 2005; Hallworth et al., 2003; Otsuka et al., 2001). Interestingly, GPe-STN inhibition is phase offset to motor cortical excitation in idiopathic and experimental PD, most likely due to abnormal hyperactivity of GABAergic striatopallidal neurons, and may therefore promote excessive cortical patterning of the STN (Baufreton et al., 2005; Galvan and Wichmann, 2008; Hammond et al., 2007; Jenkinson and Brown, 2011; Mallet al., 2006; 2008a, 2012; Shimamoto et al., 2013; Tachibana et al., 2011). In addition, the strength of GPe-STN inputs increases profoundly following loss of dopamine, which may further intensify abnormal, correlated activity (Fan et al., 2012).

The balance of synaptic excitation and inhibition is critical to the operation of brain microcircuits and is often perturbed in disease (Turrigiano, 2011). In complex microcircuits the relative strengths of glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission rise and fall in unison or shift in opposite directions depending on the prevailing pattern and level of cellular and network activity (Turrigiano, 2011). We therefore hypothesized that: 1) the STN likely possesses an intrinsic homeostatic mechanism that regulates the balance of incoming hyperdirect cortical excitation and indirect pathway GPe inhibition; 2) excessive engagement of this regulatory mechanism by parkinsonian indirect and hyperdirect pathway activity triggers abnormal strengthening of GPe-STN transmission. Because plasticity at GABAergic synapses is typically heterosynaptic and driven by glutamatergic transmission (Castillo et al., 2011), we first tested whether motor cortical inputs heterosynaptically regulate GPe-STN transmission and then whether motor cortical inputs drive pathological strengthening of GPe-STN transmission that follows the loss of dopamine.

RESULTS

Optogenetic stimulation of motor cortical inputs and electrical stimulation of GPe-STN inputs ex vivo

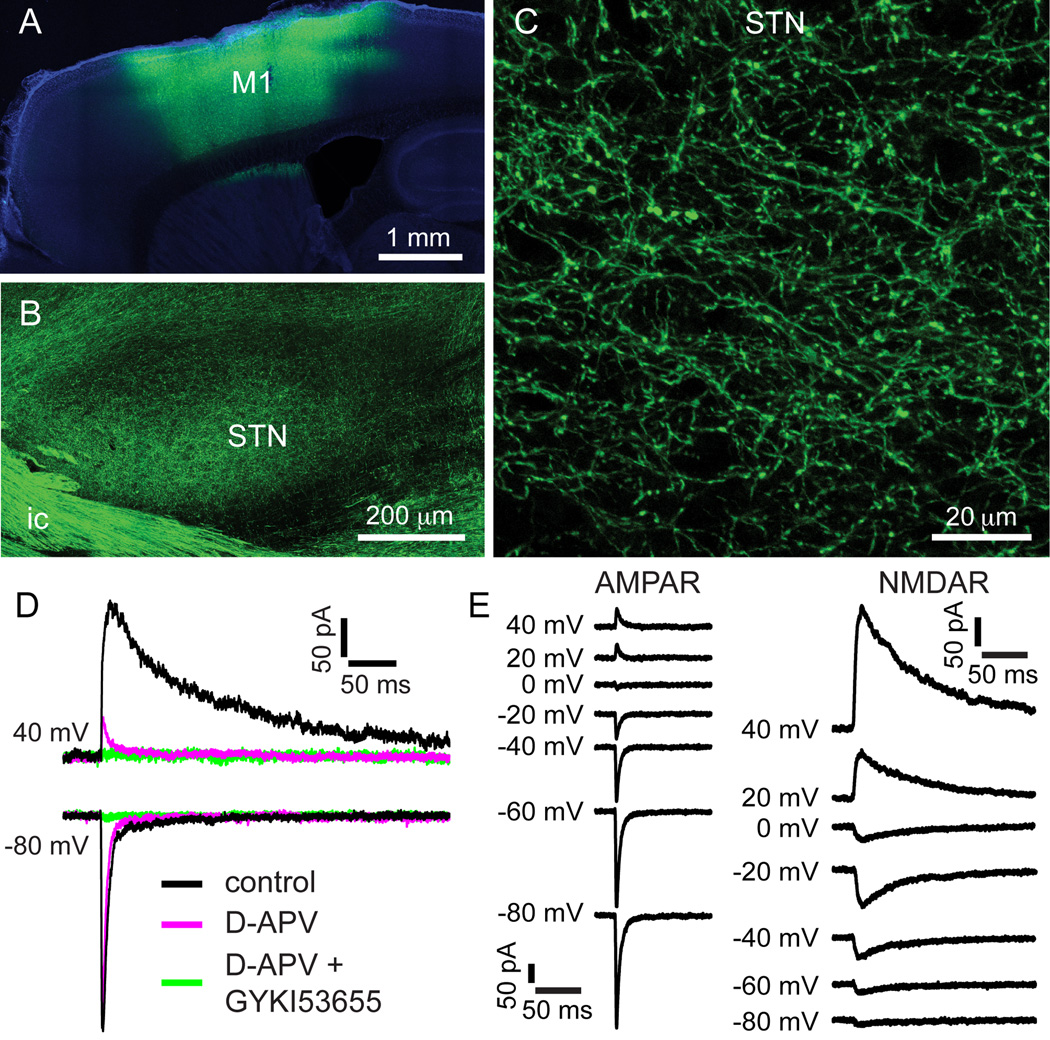

In order to determine how motor cortical inputs regulate the strength of GPe-STN transmission, a combined optogenetic and electrical stimulation approach was employed in adult mice to selectively stimulate motor cortex-STN and GPe-STN transmission, respectively, ex vivo. Stereotaxic injection of an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector was used to express ChR2(H134R)-eYFP in motor cortical neurons and their axon terminals in the STN (Afsharpour, 1985; Kita and Kita, 2012; Monakow et al., 1978) (Figure 1). Injections were centered on the forelimb representation, as defined by a recent microstimulation study (Tennant et al., 2011). Robust optogenetic excitation of motor cortical projections to the STN (Figure 1) was subsequently confirmed with patch clamp recording. Optogenetic stimulation of motor cortex-STN axon terminals generated glutamatergic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in STN neurons (Figure 1). These EPSCs were sensitive to the AMPAR antagonist GYKI53665 (50 µM) and the NMDAR antagonist D-APV (50 µM) (Figure 1D; n = 7). Pharmacologically isolated AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated components of motor cortex-STN EPSCs exhibited typical, distinct voltage dependencies and kinetics (Figure 1E, Figure S1; n = 6) (Jonas, 1993). Focused, bipolar, electrical stimulation of the internal capsule rostral to the STN (in the presence of 1 µM CGP55845 a GABABR antagonist) was used to evoke GABAAR-mediated transmission (Bevan et al., 2002). Given that the GPe provides by far the major GABAergic input to the STN (Baufreton et al., 2009; Bevan and Bolam, 1995; Smith et al., 1990), GABAAR-mediated IPSCs were assumed to arise from GPe-STN transmission. Through this approach IPSCs were typically evoked in isolation. However, smaller, glutamatergic EPSCs were also generated occasionally and therefore routinely eliminated by application of the AMPAR antagonist DNQX (20 µM).

Figure 1. Optogenetic stimulation of motor cortex-STN inputs.

(A–C) AAV vector-mediated expression of ChR2(H134R)-eYFP centered on primary motor cortex (A; M1) and its associated projection to the STN (B, C). (B, C) Sagittal slice through the lateral motor territory of the STN. (D–E) Optogenetically stimulated motor cortex-STN EPSCs. (D) At 40 mV the EPSC was largely inhibited by the NMDAR antagonist D-APV (50 µM). At −80 mV the EPSC was largely inhibited by the additional application of the AMPAR antagonist GYKI53655 (50 µM). (E) Distinct kinetics and voltage-dependence of pharmacologically isolated AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated motor cortex-STN EPSC components. ic, internal capsule. See also Figure S1.

Optogenetic stimulation of motor cortex-STN inputs leads to heterosynaptic long-term potentiation (hLTP) of GPe-STN transmission ex vivo

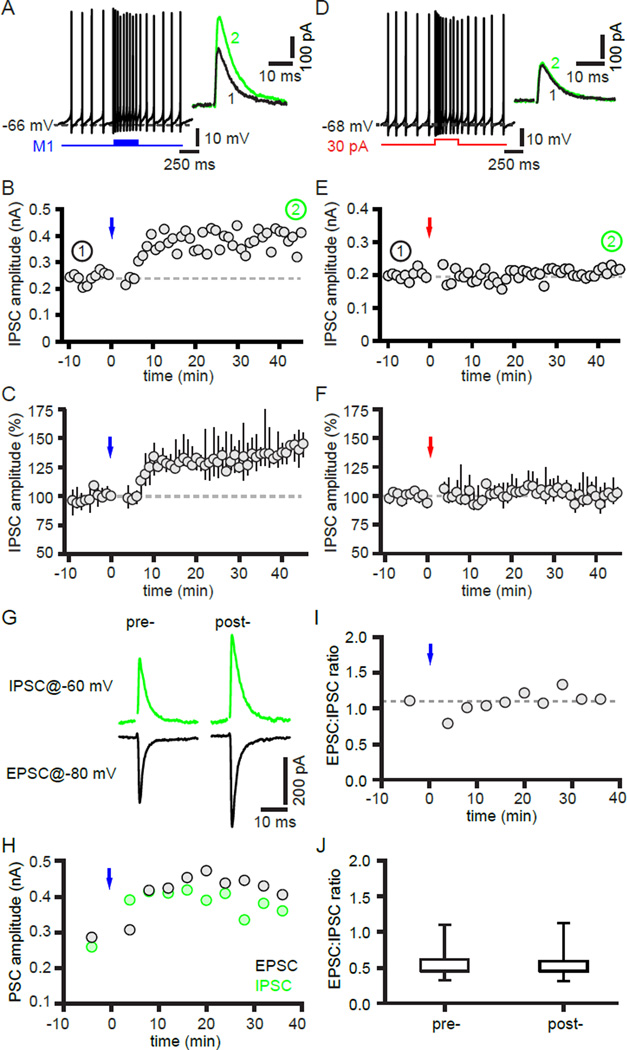

Baseline GPe-STN transmission was first monitored under voltage clamp at −60 mV for 5–10 minutes. Motor cortex-STN inputs were then stimulated optogenetically in a pattern (1 ms light pulses delivered at 50 Hz for 300 ms, with stimulus trains repeated 30 times at 0.2 Hz) that mimicked bursts of activity in motor cortical projection neurons in vivo during voluntary movement (Isomura et al., 2009). During optogenetic stimulation STN neurons were recorded in current clamp mode and were strongly driven by cortical excitation acting at STN NMDARs (as stated above, AMPARs were blocked with DNQX) (Figure 2A). The subsequent impact of cortical excitation on GPe-STN transmission was then monitored under voltage clamp at −60 mV for ~40 minutes further. Within 5 minutes of optogenetic stimulation, GPe-STN IPSCs started to increase in amplitude and after ~40 minutes GPe-STN IPSC amplitudes had increased by 44, 30 to 53% (n = 9; p < 0.05) versus baseline transmission prior to stimulation (Figure 2A–C). In order to determine whether an increase in postsynaptic activity alone (c.f., Kurotani et al., 2008; Peng et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2006) mediated the potentiation of GPe-STN transmission, STN neurons were driven to a similar degree and in a similar pattern through somatic current injection (20 to 40 pA for 300 ms, repeated 30 times at 0.2 Hz) in place of synaptic excitation (Figure 2D). However, in contrast to synaptic excitation, current injection did not lead to an increase in the strength of GPe-STN transmission (0, −7 to 7%; n = 6; p > 0.05; Figure 2D–F). Together these data demonstrate that motor cortex-STN transmission can generate hLTP of GPe-STN transmission ex vivo.

Figure 2. Optogenetic stimulation of motor cortex-STN inputs leads to hLTP of GPe-STN transmission.

(A–C) Optogenetic stimulation of motor cortical inputs (blue) drove firing in the STN (A) and led to a persistent increase in the magnitude of the electrically evoked GABAAR-mediated IPSC (A–C) both in the representative example (A–B) and across the sample population (C). (D–F) In contrast, driving STN activity to a similar degree as synaptic excitation through somatic current injection (red) did not lead to potentiation of the IPSC in the example (D–E) or sample population (F). 1 and 2 refer to time points prior to and following stimulation, respectively, in this and subsequent figures. (G–J) Optogenetically evoked motor cortex-STN EPSCs and electrically evoked GPe-STN IPSCs were monitored at −80 mV and −60 mV, respectively, in the same neuron before and after optogenetic induction. Both the IPSC and EPSC potentiated to a similar extent such that the ratio of excitation to inhibition pre- and post-induction was similar both in the representative example (G–I) and in the sample population (J). See also Figure S2.

To determine whether hLTP can balance LTP of motor cortex-STN transmission, the impact of the same optogenetic induction protocol on motor cortex-STN inputs was first tested. The motor cortex-STN EPSC was recorded at −80 mV and AMPARs were not blocked in these experiments. Optogenetic induction led to LTP of motor cortex-STN transmission in the majority of STN neurons tested (10 of 14 exhibited LTP; 3 of 14 exhibited no plasticity; 1 of 14 exhibited LTD; Figure S2A–C). Overall the induction protocol increased the amplitude of motor cortex-STN transmission by 42, −1.6 to 61% (n = 14; p < 0.05). In neurons that exhibited LTP the amplitude of motor cortex-STN transmission increased by 49, 41 to 99% (n = 10; p < 0.05). Next, optogenetically evoked motor cortex-STN EPSCs and electrically evoked GPe-STN IPSCs were monitored at −80 mV and −60 mV, respectively, in the same neuron before and after optogenetic induction (Figure 2G–J). In 5 neurons tested both the EPSC and IPSC potentiated to a similar extent, confirming that LTP of motor cortex-STN transmission is balanced by hLTP of GPe-STN transmission (Figure 2G–J). As a result, the ratio of excitation to inhibition pre- and post-induction was similar (pre-induction = 0.45, 0.45 to 0.62; post-induction = 0.46, 0.45 to 0.59; n = 5; p > 0.05). We next sought to dissect the mechanisms underlying hLTP.

Activation of postsynaptic NMDARs is required for hLTP

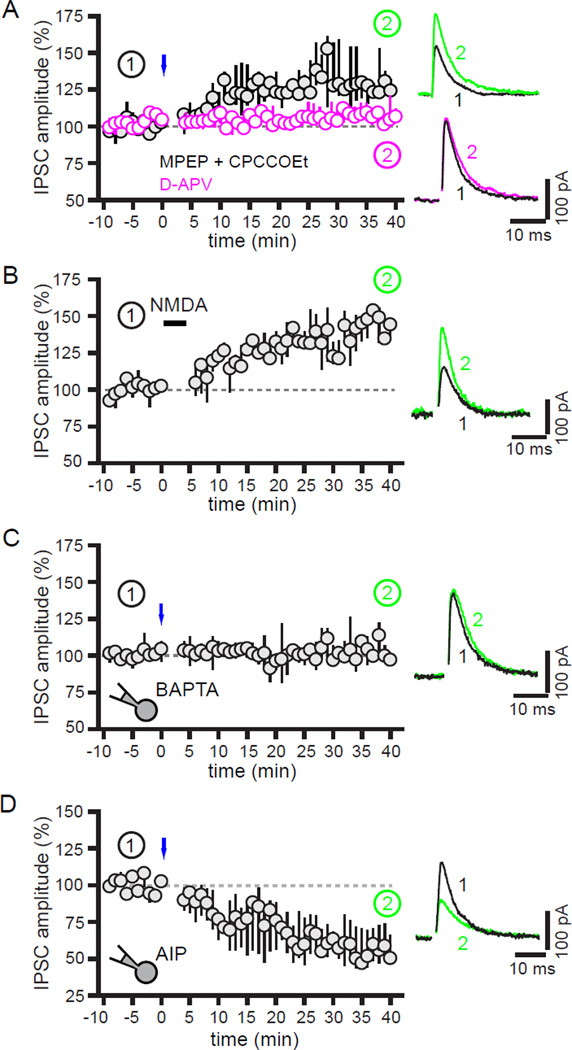

Because AMPA/kainateRs were usually antagonized with DNQX when studying hLTP, activation of these receptors was not required for hLTP of GPe-STN transmission. Although activation of group 1 mGluRs triggers LTP of GABAAR mediated transmission in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Patenaude et al., 2003), additional antagonism of Group 1 mGluRs with 50 µM CPCCOEt and 10 µM MPEP also did not prevent hLTP (32,18 to 36%; n = 6; p < 0.05; Figure 3A). In contrast, blockade of NMDARs, a more common trigger of GABAergic transmission plasticity (Marsden et al., 2007; Nugent et al., 2007; Ouardouz and Sastry, 2000), with D-APV (50 µM) completely eliminated hLTP (2, −2 to 6%; n = 7; p > 0.05; Figure 3A). Furthermore, application of 50 µM NMDA for 5 minutes induced robust LTP of GPe-STN transmission (48, 35 to 53%; n = 6; p < 0.05; Figure 3B). Given that brain slices were prepared from mice that had been anesthetized with ketamine, an NMDAR antagonist, a subset of mice (n = 3) were anesthetized with isoflurane in order to determine whether hLTP was influenced by anesthetic. hLTP was also reliably generated in these mice (51, 30 to 85%; n = 4) suggesting that the observations reported here were not greatly affected by the choice of anesthetic.

Figure 3. Activation of postsynaptic NMDARs is required for hLTP of GPe-STN transmission.

(A) Blockade of NMDARs with D-APV prevented optogenetic (blue) induction of LTP in contrast to the blockade of Group 1 mGluRs with CPCCOEt (50 µM) and MPEP (10 µM), which did not prevent hLTP. (B) Application of 50 µM NMDA for 5 minutes mimicked hLTP. (C–D) Inclusion in the recording pipette of the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA (20 mM) or the specific CaMKII inhibitor AIP (50 µM) prevented hLTP. In the latter case hLTP was replaced by LTD. Left panels, population time-courses. Right panels, representative examples of GPe-STN IPSCs before and after optogenetic or chemical stimulation.

Because NMDARs are permeable to Ca2+ they typically contribute to synaptic plasticity through an elevation of intracellular Ca2+ and activation of Ca2+-dependent signaling pathways (Castillo et al., 2011; Marsden et al., 2007; Nugent et al., 2007; Ouardouz and Sastry, 2000). In order to determine the location of the NMDAR-Ca2+ signaling cascade necessary for hLTP, the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA (20 mM) or the specific CaMKII inhibitor autocamtide-2-related inhibitory peptide (AIP, 50 µM) were infused via the patch pipette into the recorded postsynaptic neuron. Chelation of postsynaptic Ca2+ with BAPTA completely prevented hLTP (0, −6 to 7%; n = 6; p > 0.05; Figure 3C). Inhibition of postsynaptic CaMKII also eliminated hLTP and replaced it with LTD of GPe-STN transmission (−44, −52 to −30%; n = 7; p < 0.05; Figure 3D). Together these data demonstrate that activation of postsynaptic NMDARs, Ca2+ entry and protein kinase activation are required for hLTP. Interestingly, blockade of NMDARs also prevented LTP of motor cortex-STN synapses (−5, −7 to 0%; n = 6; p > 0.05) demonstrating that both hLTP and LTP are dependent on NMDAR activation (Figure S2D–F).

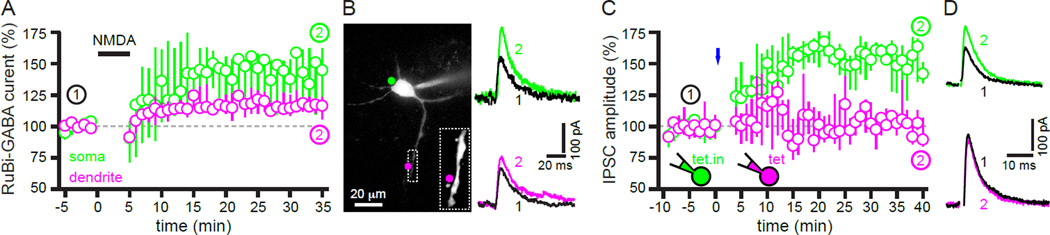

hLTP involves insertion of GABAARs into the postsynaptic membrane

hLTP in other brain circuits is mediated by pre- and/or post-synaptic alterations (Castillo et al., 2011). In order to isolate the contribution of postsynaptic alterations, STN neurons (n = 7) were imaged using 2-photon laser scanning microscopy (2PLSM; Atherton et al., 2010) and RuBi-GABA (10–20 µM) was spot uncaged at their soma or dendrites 33, 30 to 57 µm from the soma (Figure 4, Figure S3). The distance from the somatic (and dendritic) membrane at which negligible GABAAR current was evoked was ~20 µm (Figure S3) implying that uncaging at STN somata, which are approximately 10 to 15 µm in diameter, largely activated somatic and proximal dendritic GABAARs, whereas uncaging at dendrites > 20 µm from the soma largely activated dendritic GABAARs. Bath application of NMDA (50 µM for 5 minutes) enhanced the amplitude of the current evoked by 1 ms uncaging of RuBi-GABA at both somatic (45, 14 to 61%; n = 6; p < 0.05) and dendritic locations (16, 11 to 23%; n = 7; p < 0.05; Figure 4A, B). These observations suggest that NMDAR activation leads to an increase in the expression of GABAARs in the somatodendritic membrane of STN neurons (c.f., Marsden et al., 2007). Rapid SNARE-dependent insertion of synaptic receptors into the plasma membrane may contribute to LTP at both glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses (Lu et al., 2001; Ouardouz and Sastry, 2000). In order to test the contribution of receptor insertion to hLTP, the VAMP inhibitor tetanus toxin (20 nM), or its heat-inactivated form, were infused into the postsynaptic neuron via the recording pipette prior to optogenetic stimulation of motor cortex-STN inputs. Optogenetic induction of hLTP was prevented by intracellular infusion of tetanus toxin (2, −3 to 12 %; n = 7; p > 0.05; Figure 4C, D), whereas infusion of heat-inactivated tetanus toxin (20 nM) had no effect (52, 34 to 64%; n = 5; p < 0.05; Figure 4C, D). Together these data demonstrate that hLTP is mediated, at least in part, by insertion of GABAARs into the somatodendritic membrane of STN neurons.

Figure 4. hLTP of GPe-STN transmission involves the rapid SNAREdependent insertion of GABAARs into the postsynaptic membrane.

(A–B) Bath application of NMDA (50 µM for 5 minutes) enhanced IPSCs generated by RuBi-GABA uncaging both at somatic (green) and dendritic (magenta) locations. (A) Population time-courses. (B) Representative example showing sites of uncaging and RuBi-GABA-evoked IPSCs before and after NMDA application. (C–D) Inclusion of the VAMP inhibitor tetanus toxin (tet.) in the recording pipette prevented hLTP following optogenetic stimulation of motor cortical inputs (blue), whereas inclusion of heat-inactivated tetanus toxin (tet.in.) did not. (C) Population time-courses. (D) Representative examples. See also Figure S3.

hLTP is associated with an increase in the probability of GPe-STN transmission

To determine how the probability of GPe-STN transmission was altered by hLTP the ratio of 2 GPe-STN IPSCs stimulated with a 50 ms interval was measured before and after optogenetic stimulation of motor cortical inputs. hLTP was associated with a small but significant decrease in the ratio of IPSC2:IPSC1 amplitude (pre-induction = 0.86, 0.84 to 0.88; post-induction = 0.79, 0.77 to 0.80; n = 9; p < 0.05; Figure 5A, B). hLTP was also associated with a reduction in the coefficient of variation (CV) of IPSC1 amplitude such that there was a profound increase in 1/CV2 of IPSC1 (pre-induction = 96, 56 to 143; post-induction = 252, 90 to 435; n = 9; p < 0.05; Figure 5C). Together these data suggest that hLTP is associated with an increase in the probability of GPe-STN transmission. An analogous approach was applied to determine how the probability of motor cortex-STN transmission was altered following induction of LTP. In contrast to hLTP, the ratio of EPSC2:EPSC1 was unaltered following LTP suggesting that LTP was largely postsynaptic in nature (pre-induction = 1.02, 1.00 to 1.11; postinduction = 1.00, 0.95 to 1.06; n = 10; p > 0.05; data not shown). Given that the motor cortex-STN EPSC evoked at −80 mV is mediated largely by AMPARs, LTP is therefore likely due to an increase in postsynaptic AMPAR current.

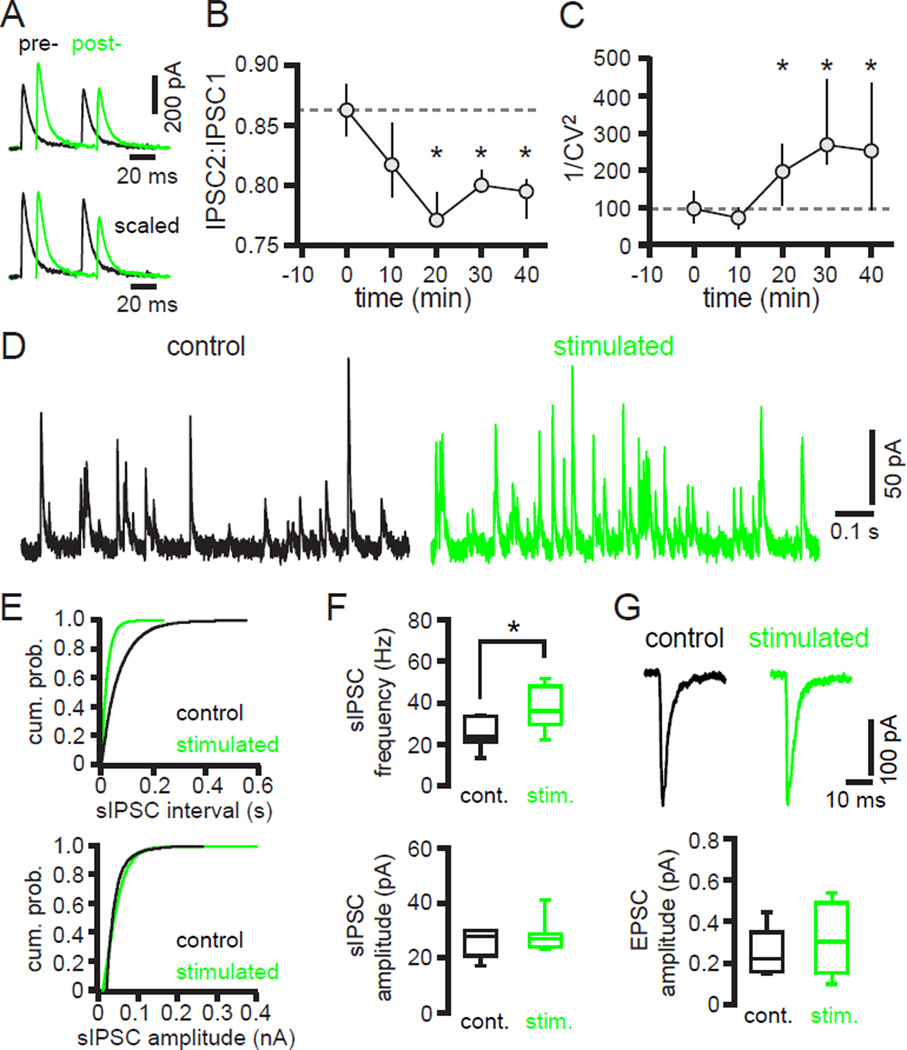

Figure 5. hLTP is associated with an increase in the probability of GPe-STN transmission.

(A–C) hLTP was associated with a significant decrease in the ratio of IPSC2:IPSC1 amplitude and a significant increase in 1/CV2 of IPSC1 amplitude. (A) Representative example pre- and post-induction. (B, C) Population data. (D–F) In neurons that had received optogenetic stimulation the frequency (but not the amplitude) of spontaneous (s) GPe-STN IPSCs was greater. (D, E) Representative examples. (F) Population data. (G) The amplitude of optogenetically stimulated motor cortex-STN EPSCs was similar for neurons that did or did not receive the optogenetic induction protocol. *, p < 0.05. cum. prob., cumulative probability. stim., stimulated.

The amplitude and frequency of spontaneous GABAAR-mediated IPSCs (sIPSCs) were also compared in STN neurons that received optogenetic stimulation and, as a control, in neurons that did not. Recordings commenced at least 40 minutes after the induction protocol was initiated or for control slices at an analogous time point. The frequency of GPe-STN sIPSCs was greater in neurons from stimulated slices (non-stimulated = 23, 21 to 34 Hz; n = 11; stimulated = 36, 30 to 48 Hz; n = 13; p < 0.05; Figure 5D–F). However, the amplitude of sIPSCs was not altered by optogenetic stimulation (non-stimulated = 28, 21 to 30 pA; n = 11; stimulated = 27, 24 to 29 pA; n = 13; p > 0.05; Figure 5D–F). STN neurons from each group received a similar level of motor cortical innervation, as evidenced by the amplitude of optogenetically stimulated EPSCs (non-stimulated = 220, 158 to 349 pA; n = 11; stimulated = 303, 152 to 490 pA; n = 13; p > 0.05; Figure 5G). Together these data demonstrate that the overall level of GPe-STN transmission increases following hLTP but the amplitude of individual sIPSCs is unaltered. Given the postsynaptic component of hLTP, described above, one possibility is that an increase in the number of functional synapses underlies hLTP (Clements and Silver 2000; Malenka and Nicoll, 1999).

Involvement of nitric oxide (NO) signaling in hLTP

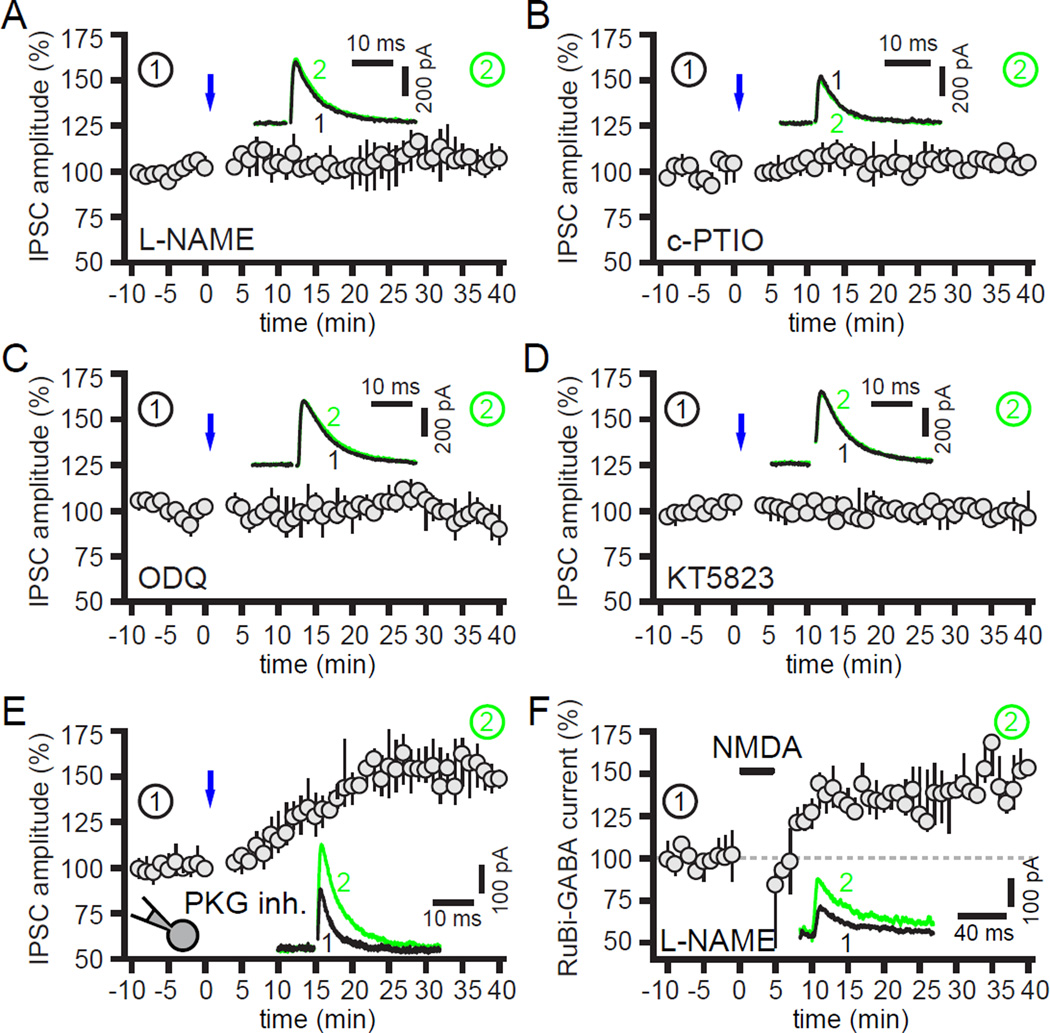

NMDAR-dependent activation of postsynaptic NO-synthase (NOS), release of NO and activation of presynaptic guanylate cyclase (GC)-protein kinase G (PKG) signaling has been shown to mediate an increase in GABAergic transmission probability in several brain circuits (e.g. Nugent et al., 2007; Lange et al., 2012). Because STN neurons express NOS (Nisbet et al., 1994) and GPe neurons express soluble GC (Pifarre et al., 2007) the involvement of NO signaling in hLTP of GPe-STN transmission was tested. Incubation of brain slices with the membrane permeable NOS inhibitor L-NAME (100 µM) for 30 min prevented the optogenetic induction of hLTP (5, 0 to 11 %; n = 8; p > 0.05; Figure 6A). hLTP was also blocked by bath application of the NO scavenger c-PTIO (30 µM) (3, 1 to 7%; n = 6; p > 0.05; Figure 6B), the membrane permeable GC inhibitor ODQ (10 µM) (−3, −7 to 5%; n = 6; p > 0.05; Figure 6C) or the membrane permeable PKG inhibitor KT5823 (1 µM) (−2, −7 to 1%; n = 5; p > 0.05; Figure 6D). However, inhibition of postsynaptic PKG activity alone by inclusion of a membrane impermeable PKG inhibitory peptide (100 µM) in the recording pipette did not prevent hLTP (54, 42 to 59%; n = 6; p < 0.05; Figure 6E). Together with the above data, these results are consistent with the conclusion that NMDAR-dependent activation of postsynaptic NOS leads to the liberation of NO from STN neurons and activation of GC and PKG in GPe-STN axon terminals. Indeed, continuous application of the NOS inhibitor L-NAME (100 µM) did not prevent potentiation of GABAAR current evoked by somatic uncaging of RuBi-GABA following 5 minutes of NMDA (50 µM) administration (46, 23 to 51 %; n = 6; p < 0.05; Figure 6F). Thus, NO signaling is not required for the insertion of GABAARs into the postsynaptic membrane. Finally, application of the NO donor SNAP (100–200 µM) did not lead to potentiation of GPe-STN inputs (−1, −10 to 6%; n = 9; p > 0.05; data not shown) demonstrating that, while NO signaling is necessary, it is not sufficient for hLTP in the absence of NMDAR activation.

Figure 6. Nitric oxide (NO) signaling is necessary for hLTP.

(A–E) Induction of hLTP by optogenetic stimulation of motor cortical inputs (blue) was blocked by bath application of (A) a NOS inhibitor (100 µM L-NAME), (B) a NO scavenger (30 µM c-PTIO), (C) a GC inhibitor (10 µM ODQ) or (D) a PKG inhibitor (1 µM KT5823). (E) However, inhibition of postsynaptic PKG activity by application of PKG inhibitory peptide (100 µM) via the recording pipette did not prevent hLTP. (F) Inhibition of NOS (100 µM L-NAME) also did not prevent potentiation of GABAAR current evoked by somatic uncaging of RuBi-GABA following NMDA (50 µM) administration for 5 minutes. Insets, representative IPSCs before and after optogenetic or chemical stimulation.

hLTP is associated with alterations in GABAergic synaptic markers

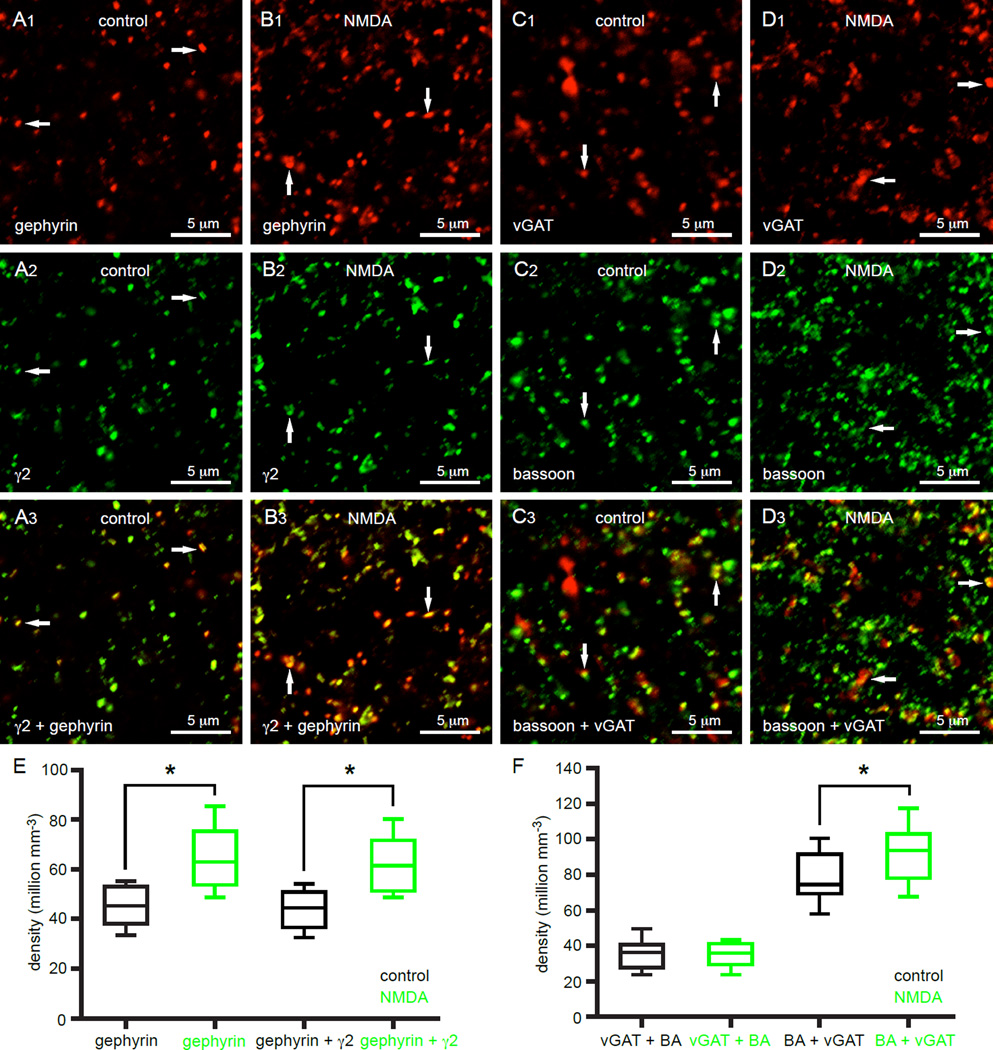

To test whether structural changes are associated with hLTP, brain slices were subjected to optogenetic or chemical (50 µM NMDA for 5 minutes) induction protocols or left untreated. 40 minutes later brain slices were briefly immersionfixed with paraformaldehyde. The densities of structures expressing GABAergic postsynaptic and presynaptic markers were then assessed by immunohistochemistry. The scaffolding protein gephyrin and the GABAAR subunit γ2 were used as postsynaptic markers and the vesicular GABA transporter and the active zone protein bassoon were used as presynaptic markers. In slices that contained high densities of ChR2(H134R)-eYFP-expressing motor cortex-STN axon terminals there was a significantly higher density of gephyrin-immunoreactive structures in optogenetically stimulated slices (non-stimulated = 12, 9 to 21 million/mm3; n = 17; stimulated = 20, 13 to 34 million/mm3; n = 17; p < 0.05; Figure S4A, B, E). In contrast, optogenetic stimulation did not alter the density of gephyrin-immunoreactive structures in slices that contained few ChR2(H134R)-eYFP-expressing motor cortex-STN axon terminals, (non-stimulated = 15, 11 to 16 million/mm3; n = 13; stimulated = 15, 11 to 18 million/mm3; n = 13; p > 0.05; Figure S4C, D, E).

Although optogenetic stimulation produced a clear increase in the density of gephyrin-immunoreactive structures, the resolution of this and other synaptic markers was further optimized for subsequent experiments by increasing the magnification of the objective from 40× to 100× and the digital zoom from 2.5× to 5×. As a result, the apparent density of detectable gephyrin-immunoreactive structures increased. Administration of NMDA to slices increased the density of gephyrin-immunoreactive structures 40 minutes after treatment compared to untreated slices (control = 45, 38 to 53 million/mm3; n = 12; NMDA = 63, 54 to 75 million/mm3; n = 12; p < 0.05; Figure 7A, B, E). The density of gephyrin structures that were co-immunoreactive for the GABAAR subunit γ2 was similarly elevated by NMDA (control = 44, 37 to 51 million/mm3; n = 12; NMDA = 61, 51 to 72 million/mm3; n = 12; p < 0.05; Figure 7A, B, E). However, NMDA treatment did not change the density of GABAergic axon terminals expressing the vesicular GABA transporter (vGAT) (control = 39, 34 to 49 million/mm3; n = 14; NMDA = 40, 35 to 44 million/mm3; n = 14; p > 0.05; Figure 7C, D, F) or the density of vGAT-immunoreactive GABAergic axon terminals that co-expressed the active zone protein bassoon (control = 36, 28 to 41 million/mm3; n = 14; NMDA = 36, 29 to 41 million/mm3; n = 14; p > 0.05; Figure 7C, D, F). The density of bassoon-immunoreactive structures in vGAT-immunoreactive GABAergic axon terminals was also studied to estimate the number of active zones pre- and post-induction. NMDA treatment moderately but significantly increased the number of active zones in vGAT-immunoreactive GABAergic axon terminals (control = 74, 69 to 92 million/mm3; n = 14; NMDA = 94, 78 to 103 million/mm3; n = 14; p < 0.05; Figure 7C, D, F). The mean absolute fluorescence intensity and size of individual, stereologically selected, immunoreactive, pre- and postsynaptic structures were not significantly different in tissue sections that were or were not subjected to optogenetic or chemical induction (data not shown). Taken together these data demonstrate that hLTP is associated with an increase in the density of postsynaptic and (to a lesser extent) presynaptic markers, while the density of GABAergic axon terminals remains constant.

Figure 7. Activation of STN NMDARs increases the density of GABAergic postsynaptic and presynaptic markers.

(A, B, E) Bath application of NMDA (50 µM for 5 minutes) increased the density of gephyrin-immunoreactive structures and the density of gephyrin-immunoreactive structures that were co-immunoreactive for the GABAAR subunit γ2 (white arrows). (C, D, F) NMDA treatment had no effect on the density of vGAT-immunoreactive structures that were co-immunoreactive for bassoon (BA). However NMDA treatment did lead to a small but significant increase in the density of bassoon-immunoreactive structures that were co-immunoreactive for vGAT (white arrows). *, p < 0.05. See also Figure S4.

Knockdown of STN NMDARs reduces GABAergic GPe-STN transmission in control and dopamine-depleted mice

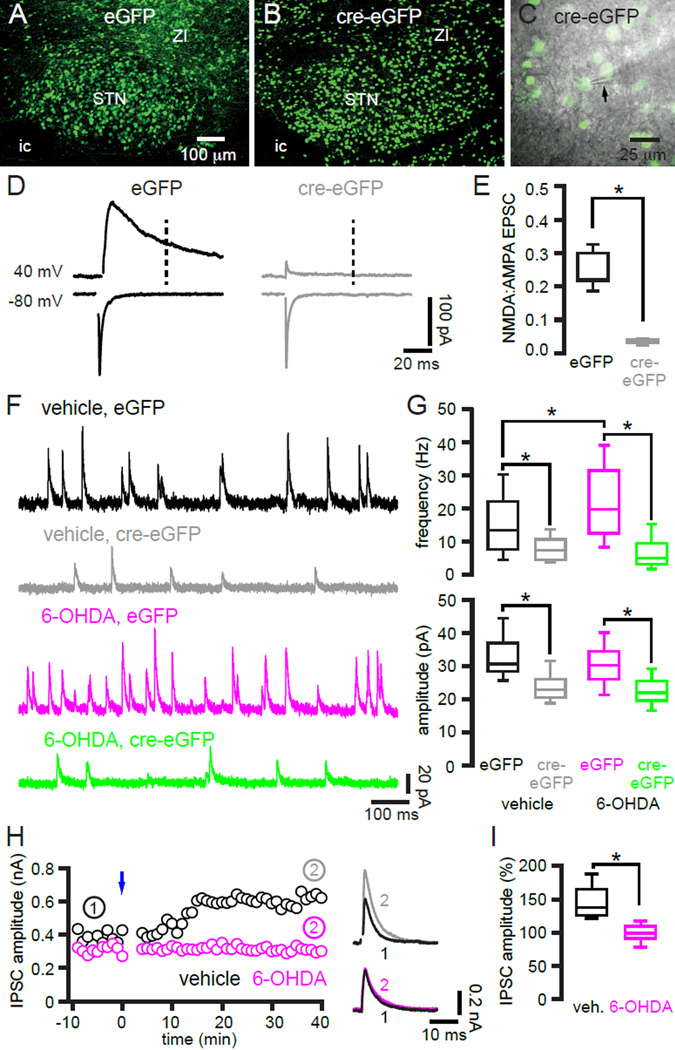

Following chronic depletion of dopamine in the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesion model of PD, GPe-STN transmission is profoundly augmented (~40–100%) through an increase in the number of functional synapses, with no alteration in the number of GPe-STN axon terminals (Fan et al., 2012). The nature of this augmentation and the increased patterning of the disinhibited STN by cortical inputs in PD and its models in light of the present study, imply that cortical-driven hLTP of GPe-STN transmission in vivo is responsible (Hammond et al., 2007; Jenkinson and Brown, 2011; Mallet et al., 2008a, 2012; Shimamoto et al., 2013). If this hypothesis is correct then knockdown of STN NMDARs should prevent strengthening of GPe-STN transmission in experimental PD. In order to determine how NMDAR activation in vivo regulates GPe-STN transmission, AAV vectors expressing cre recombinase (cre)-eGFP or eGFP were injected into the STN of Grin1lox/lox transgenic mice (Tsien et al., 1996) in order to knockdown STN NMDARs and to control for AAV infection, respectively. During the same surgery the neurotoxin 6-OHDA or vehicle was injected into the medial forebrain bundle in order to lesion midbrain dopamine neurons and to control for injection surgery, respectively. Two to three weeks later excitatory and miniature (m) GPe-STN transmission were measured in infected neurons under 2PLSM or epi-fluorescent microscopic guidance ex vivo (Figure 8). Knockdown of the obligatory NMDAR subunit GluN1 was first confirmed by analyzing the NMDA:AMPA ratio of electrically evoked and pharmacologically isolated glutamatergic EPSCs. The NMDA:AMPA ratio was reduced in cre-eGFP expressing STN neurons compared to eGFP expressing STN neurons in dopamine intact mice (eGFP = 0.22, 0.21 to 0.30; n = 7; cre-eGFP: 0.03, 0.03 to 0.04; n = 7; p < 0.05; Figure 8D, E). In 6-OHDA-injected mice chronic dopamine depletion was verified using immunohistochemistry for striatal tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (vehicle, ipsilateral:contralateral striatal TH immunoreactivity = 100, 95 to 105%, n = 6; 6-OHDA, ipsilateral:contralateral striatal TH immunoreactivity = 2, 0 to 6%, n = 7; p < 0.05).

Figure 8. NMDAR-dependent hLTP is responsible for augmented GPe-STN transmission following loss of dopamine.

(A–C) AAV vector-mediated expression of (A) eGFP or (B, C) cre-eGFP in the STN of Grin1lox/lox transgenic mice. (C) eGFP was used to target patch clamp recording using 2PLSM (or epifluorescent) microscopy ex vivo. Arrow denotes electrode. (D, E) The NMDA:AMPA ratio was significantly reduced in cre-eGFP expressing STN neurons (n = 7) compared to eGFP expressing STN neurons (n = 7). Vertical dotted line denotes point at which NMDAR current was measured at 40 mV. AMPAR current was defined as peak current amplitude at −80 mV. (D) Representative examples. (E) Population data. (F, G) The frequency but not the amplitude of mIPSCs in eGFP expressing STN neurons was elevated in neurons from 6-OHDA-injected mice compared to vehicle-injected mice. Knockdown of STN NMDARs reduced the frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs in cre-eGFP expressing STN neurons relative to their respective eGFP expressing counterparts. (F) Representative examples. (G) Population data. (H–I) hLTP ex vivo was reduced, presumably due to occlusion, in neurons from 6-OHDA-injected mice compared to neurons from vehicle-injected mice both in the representative examples (H) and across the sample population (I). (I) The amplitude of the evoked IPSC post-induction (normalized to the amplitude preinduction) was significantly reduced. ic, internal capsule; ZI, zona incerta. *, p < 0.05.

Consistent with earlier findings (Fan et al., 2012) chronic dopamine depletion led to an increase in the frequency (vehicle eGFP = 13.5, 7.7 to 22.1 Hz; n = 45; 6-OHDA eGFP = 19.8, 12.6 to 31.5 Hz; n = 45; p < 0.05) but not the amplitude (vehicle eGFP = 31, 28 to 37 pA; n = 45; 6-OHDA eGFP = 30, 26 to 34 pA; n = 45; p > 0.05) of mIPSCs in eGFP expressing STN neurons (Figure 8F, G). Furthermore, knockdown of STN NMDARs in cre-eGFP expressing STN neurons reduced both the frequency and the amplitude of miniature GPe-STN transmission in both vehicle-injected (vehicle cre-eGFP = 7.4, 4.4 to 10.7 Hz; n = 33; p < 0.05; vehicle cre-eGFP = 23, 21 to 25 pA; n = 33; p < 0.05) and dopamine-depleted mice (6-OHDA cre-eGFP = 5.0, 3.3 to 9.5 Hz; n = 23; p < 0.05; 6-OHDA cre-eGFP = 22, 20 to 26 pA; n = 23; p < 0.05) relative to their eGFP expressing counterparts from vehicle- and dopamine-depleted mice, respectively (Figure 8F, G). The frequency and amplitude of miniature GPe-STN transmission in cre-eGFP expressing neurons from vehicle- and 6-OHDA treated mice were reduced to a similar level by NMDAR knockdown (p > 0.05). Together these data demonstrate that NMDAR activation not only triggers the increase in GPe-STN transmission that follows the loss of dopamine but also positively regulates GPe-STN transmission in control mice.

A corollary prediction is that following dopamine depletion motor cortex-STN driven hLTP reaches a ceiling in vivo that then occludes subsequent induction of hLTP ex vivo. In order to test this hypothesis, hLTP in slices taken from mice that had received injections of 6-OHDA (n = 6) or vehicle (n = 6) in the medial forebrain bundle 2–3 weeks earlier were compared. Profound dopamine depletion in 6-OHDA-treated mice was confirmed, as described above (ipsilateral:contralateral striatal TH immunoreactivity = 3, 0 to 13%, n = 6). Motor cortical inputs to STN neurons were then stimulated optogenetically in order to induce hLTP of GPe-STN inputs ex vivo, as described above. As predicted, hLTP ex vivo was significantly reduced in neurons from dopamine-depleted mice compared to those from vehicle-injected mice (vehicle = 38, 26 to 65%; n = 6; 6-OHDA = −1, −8 to 9%; n = 8; p < 0.05; Figure 8H, I). Together with previous studies, the data suggest that following dopamine depletion increased motor cortical patterning of STN neurons drives hLTP of GPe-STN transmission in vivo through increased activation of STN NMDARs.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here demonstrate that motor cortical inputs to the STN drive hLTP of GPe-STN transmission. hLTP was dependent on activation of postsynaptic NMDARs, CaMKII and NOS. NO acted presynaptically via a GC-cGMP-PKG signaling cascade. hLTP involved rapid SNARE-dependent insertion of GABAAR subunits into the postsynaptic membrane and an increase in the density of synaptic markers with no alteration in the number of GPe-STN axon terminals. Thus, hLTP was mediated by an increase in functional synapses, consistent with an increase in the frequency but not amplitude of sIPSCs. Motor cortical inputs also exhibited NMDAR-dependent LTP. In individual neurons optogenetically induced LTP and hLTP were similar in magnitude, arguing that hLTP helps to balance motor cortical excitation and GPe-STN inhibition. Knockdown of STN NMDARs in vivo reduced the frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs in control mice and prevented abnormal strengthening of GPe-STN transmission that follows loss of dopamine (Fan et al., 2012). Following dopamine depletion hLTP was occluded ex vivo, implying that excessive motor cortical patterning of the STN had maximally augmented GPe-STN transmission in vivo (Jenkinson and Brown, 2011; Hammond et al., 2007; Mallet et al., 2008a, 2012; Shimamoto et al., 2013).

Although the signaling cascades described here have previously been shown to be involved in hLTP of GABAergic transmission in other brain nuclei, the locus of hLTP in those studies was either postsynaptic or presynaptic (Castillo et al., 2011; Lange et al., 2012; Marsden et al., 2007; Nugent et al., 2007; Ouardouz and Sastry, 2000). In contrast, hLTP has both pre- and post-synaptic components in the STN. Thus, activation of postsynaptic NMDARs, Ca2+ entry and activation of CaMKII led to SNARE-dependent insertion of GABAAR subunits into the postsynaptic membrane. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry revealed an associated increase in the density of postsynaptic GABAAR γ2 subunit- and gephyrin-immunoreactive structures. The relatively high density of structures immunoreactive for the active zone protein bassoon in GABAergic axon terminals compared to the density of postsynaptic markers prior to hLTP suggests that hLTP is mediated in part by insertion of GABAA receptors and scaffolding proteins like gephyrin into receptor deficient or silent synapses, analogous to the mechanism first described at glutamatergic synapses (Malenka and Nicoll, 1999). Certainly, γ2 GABAAR subunits and gephyrin are key substrates for the assembly of synaptic GABAAR complexes (Luscher et al., 2011; Smith and Kittler, 2010; Tyagarajan and Fritschy, 2010; Vithlani et al., 2011). Additional molecular partners such as GABARAP, which is phosphorylated by CaMKII following NMDAR activation, may also be important for trafficking GABAAR subunits and associated molecules to the postsynaptic membrane prior to insertion (Marsden et al., 2007).

On the presynaptic side, we infer that NO is generated postsynaptically but acts retrogradely on GPe-STN axon terminals because postsynaptic Ca2+ chelation prevented hLTP, in contrast to postsynaptic PKG inhibition, which had no effect. Furthermore, insertion of GABAARs into the postsynaptic membrane, as assessed by RuBi-GABA uncaging, was not altered by inhibition of NOS. The expression of NOS in STN neurons (Nisbet et al., 1994) and sGC in GPe neurons (Pifarre et al., 2007) is consistent with this thesis. The precise action of presynaptic GC-cGMP-PKG signaling in hLTP is unclear. One possibility is that this cascade mobilizes vesicles at synapses that prior to induction were deficient in postsynaptic receptors. Indeed, in structures where hLTP is presynaptic, NO-GC-cGMP-PKG signaling mediates an increase in transmission probability (Lange et al., 2012; Nugent et al., 2007). Interestingly, the predicted but subtle increase in transmission probability due to hLTP in vivo was not detected following chronic dopamine depletion (Fan et al., 2012). The wide variability in transmission probability is the likely cause for this detection failure. Here, the influence of this variability was reduced because transmission probabilities of the same connections were compared before and following optogenetic induction ex vivo. A small but significant increase in the density of bassoon-immunoreactive active zones in GPe-STN axon terminals was also noted 40 minutes after induction, implying that synaptic proliferation, perhaps on a longer time scale than initial events, also contributes to hLTP. LTP of motor cortex-STN synapses was also NMDAR-dependent and associated with an increase in AMPAR EPSC amplitude with no alteration in PPR, implying that it is similar in form to classical LTP (Malenka and Nicoll, 1999).

It has been assumed that the balance of movement suppressing and promoting pathway activity in the basal ganglia is under the control of dopamine and determined within the striatum (Albin et al., 1989; Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011). Here, we reveal that hyperdirect and indirect pathway interactions are additionally subject to NMDAR-dependent regulation within the STN. Activation of STN NMDARs at motor cortex-STN synapses in vivo is presumably a function of the frequency and pattern of presynaptic activity, synaptic strength and the integrative state of the postsynaptic neuron. Under normal conditions GPe-STN inhibition and cortical excitation are poorly correlated and often coincident (Galvan and Wichmann, 2008; Hammond et al., 2007; Jenkinson and Brown, 2011; Magill et al., 2001; Mallet et al., 2008a, 2012; Tachibana et al., 2011). Thus, GPe-STN inhibition is likely to limit, through hyperpolarization and shunting of synaptic excitation, cortical activation of STN NMDARs and the extent of hLTP (and LTP) (Atherton et al., 2010; Fujimoto and Kita, 1993; Maurice et al., 1998).

Following dopamine depletion, GPe-STN transmission strength increases profoundly (Fan et al., 2012) and hLTP ex vivo is occluded, implying that strengthening resulted from motor cortical-driven hLTP in vivo. Furthermore, knockdown of STN NMDARs prevented strengthening. But how does loss of dopamine trigger strengthening of GPe-STN inputs? The most likely explanation is that the frequency and pattern of GPe-STN transmission are altered by hyperactive striatopallidal neurons (Albin et al., 1989; Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011; Mallet et al., 2006) and downregulation of GPe HCN channels (Chan et al., 2011). As a result, GPe-STN activity is reduced in frequency and offset in phase to motor cortex-STN excitation (Magill et al., 2001; Mallet et al., 2008a, 2012), leading to increased activation of STN NMDARs, which in turn trigger excessive strengthening of GPe-STN inputs. Although the frequency of motor cortical neuron activity is not altered by loss of dopamine, their firing becomes more synchronous (Goldberg et al., 2002), which may further promote activation of STN NMDARs. Another, as yet untested possibility, suggested by this study, is that motor cortical synapses strengthen through NMDAR-dependent LTP. Indeed, the ratio of whole-cell AMPAR to NMDAR current increases following dopamine depletion (Shen and Johnson, 2005). However, the STN also receives glutamatergic inputs from the thalamus, pedunculopontine nucleus and superior colliculus (Bevan and Bolam, 1995; Coizet et al., 2009; Smith et al., 1998) and the plasticity processes these inputs engage under normal conditions and following loss of dopamine remain to be determined.

Because GPe-STN inhibition is offset in phase relative to cortical excitation in experimental PD, strengthening of GPe-STN synapses may promote pathological activity through de-inactivation of postsynaptic Nav and Cav channels, which underlie rebound burst firing and enhance excitatory synaptic integration at the offset of inhibition (Baufreton et al., 2005; Hallworth et al., 2003; Otsuka et al., 2001). Indeed, electrophysiological (Baufreton et al., 2005, 2009; Mallet et al., 2008a, 2012; Tachibana al., 2011) and computational (Holgado et al., 2010; Moran et al., 2011; Terman et al., 2002) studies argue that strengthening GPe– STN inputs actually enhances the capability of the GPe (and cortex) to generate abnormal, correlated STN activity. In the 6-OHDA model it takes days to weeks for the emergence of abnormal activity, implying that circuit plasticity triggered by the loss of dopamine is a key contributor (Mallet al., 2008b). Furthermore, in experimental PD silencing GPe activity abolishes abnormal activity in the STN, suggesting a causative role (Tachibana et al., 2011). Thus, together with striatopallidal neurons (Day et al., 2006; Gittis et al., 2011), STN neurons exhibit maladaptive synaptic plasticity that is driven by the engagement of intrinsic, homeostatic, regulatory mechanisms following loss of dopamine.

In summary, this study demonstrates that hyperdirect pathway motor cortical inputs to the STN regulate the strength of indirect pathway GPe-STN inhibition. Under normal conditions this heterosynaptic regulation is homeostatic and balances cortical excitation with an appropriate level of GPe inhibition. However in the absence of dopamine, GPe-STN inhibition is phase offset to motor cortex-STN excitation leading to increased activation of STN NMDARs and profound strengthening of GPe-STN transmission, which may in turn promote pathological activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

See Supplemental Information for further details.

Animals

Experiments were performed in accordance with institutional, NIH, and Society for Neuroscience guidelines using adult male C57BL/6 mice or Grin1lox/lox (B6.129S4-Grin1tm2Stl/J) mice.

Stereotaxic injection of viral vectors and 6-OHDA

AAV vectors were injected stereotaxically under isoflurane anesthesia. AAV expressing hChR2(H134R)-eYFP was injected bilaterally into the primary motor cortex of C57BL/6 mice. AAV expressing eGFP or cre-eGFP was injected unilaterally in the STN of Grin1lox/lox mice. In order to lesion midbrain dopamine neurons or control for surgical injection 6-OHDA (3–5 mg/ml) or vehicle were injected into the medial forebrain bundle. The selectivity and toxicity of 6-OHDA were enhanced through IP injection of desipramine and pargyline, respectively. Brain slices were prepared from AAV-, 6-OHDA- and vehicle-injected mice 2–3 weeks after injection.

Slice preparation

AAV-injected and naive mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine or isoflurane and perfused transcardially with sucrose-based artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at 1–4°C. Parasagittal brain slices (electrophysiology, 250 µm; immunohistochemistry, 200 µm) containing the motor cortex and/or STN were prepared in the same solution using a vibratome. Slices were held in ACSF at 35 °C for 30 min and then at room temperature until re cording.

Electrophysiology, optogenetic and chemical stimulation

For electrophysiological recording and optogenetic or chemical stimulation slices were transferred to a recording chamber, perfused at a rate of ~ 5 ml/min with synthetic interstitial fluid (SIF) at 35–37 °C. 2 µM CGP55845 was added to inhibit GABABRs. Somatic patch clamp recordings were obtained using glass micropipettes filled with either: 1) a K+-gluconate-based solution or 2) a Cs+-methansulfonate-based solution. Signals were low-pass filtered at 10 kHz and sampled at 20–50 kHz. Electrode capacitance was compensated and data were not included if series resistance changed >20%. For sIPSC and mIPSC recordings series resistance and whole-cell capacitance were compensated. Liquid junction potentials were corrected online.

IPSCs were evoked by electrical stimulation of the internal capsule rostral to the STN and recorded in the additional presence of DNQX (20 µM) in voltage-clamp mode at −60 mV using pipette solution 1. sIPSCs and mIPSCs were recorded at 0 mV using pipette solution 2. sIPSCs were recorded in the presence of D-APV (50 µM). mIPSCs were recorded in the presence of D-APV (50 µM), DNQX (20 µM), and TTX (0.5 µM). Optogenetic excitation was delivered via a 63× objective lens using a 470 nm LED. Chemical excitation was mediated through application of NMDA (50 µM) in SIF at 35–37°C for 5 minutes.

2-photon imaging and RuBi-GABA uncaging

eGFP/cre-eGFP expressing- and Alexa Fluor 594-filled STN neurons were imaged using 2PLSM at 820 nm with 76 MHz pulse repetition and ~250 fs pulse duration at the sample plane. Alexa Fluor 594 (20 µM) was applied via pipette solution 1 in order to visualize individual STN neurons for uncaging experiments. RuBi-GABA (10–20 µM) was applied via SIF and uncaged using 473 nm light targeted to the soma or dendrite of the recorded neuron (power: 20–30 mW, duration: 1 ms). DNQX (20 µM) and CGP55845 (2 µM) were applied throughout.

Immunohistochemistry

eYFP, eGFP and immunofluorescent labeling were visualized using confocal laser scanning microscopy. To visualize expression of AAV vectors in the motor cortex and STN brain slices were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4 °C following recording. Slices were then washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and mounted on glass slides and coverslipped. Dopaminergic innervation in 6-OHDA- and vehicle-injected mice was assessed through immunohistochemistry for TH, as described previously (Fan et al., 2012).

Following incubation in ACSF for 1 hour, a subset of slices was subjected to optogenetic or chemical excitation, as stated above, in order to induce hLTP. 40 min after excitation slices were immersion fixed in 4% PFA at room temperature for 15 min. After washing in PBS, slices were incubated in primary antibodies: mouse anti-gephyrin and/or rabbit anti-γ2 GABAAR subunit, or mouse anti-vGAT and guinea pig anti-bassoon in PBS plus 0.3% Triton X-100 and 2% normal donkey serum for 48 h at 4°C. After washing, slices were incubated in fluorescent secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-mouse IgG (to detect gephyrin), Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti rabbit IgG (to detect γ2 GABAAR subunits), Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-mouse IgG (to detect vGAT) and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti guinea pig IgG (to detect bassoon) for 2 h at room temperature. Slices were then mounted on glass slides and coverslipped and images of immunoreactivity were acquired using confocal microscopy. The densities of immunoreactive structures were assessed using ImageJ (NIH) and quantified using the optical dissector method (West, 1999), while blinded to the experimental manipulation.

Data analysis and statistics

Data are presented as the median and interquartile range. Box plots (central line, median; box, 25–75%; whiskers, 10–90%) are used to illustrate sample distributions. For statistical comparisons, the nonparametric Wilcoxon Signed- Rank test and Mann-Whitney U test were used for paired and non-paired comparisons, respectively. For datasets subjected to more than one comparison, p values were multiplied by the number of comparisons. Final p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Motor cortex-STN inputs heterosynaptically regulate GPe-STN transmission

Heterosynaptic plasticity regulates the number of functional GPe-STN connections

Under normal conditions heterosynaptic plasticity is homeostatic

Following dopamine loss heterosynaptic plasticity strengthens GPe-STN transmission

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by NIH NINDS grants 2R37 NS041280 (M.D.B), P50 NS047085 (D.J.S. and M.D.B) and P30 NS054850 (D.J.S. and D.W.). Finally, the authors thank J. Baufreton, C.S. Chan, H. Kita, P.J. Magill and C.J. Wilson for comments on the manuscript and S. Ulrich, D.R. Schowalter and M. Alicea for management of mouse colonies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.Y.C., J.F.A and M.D.B. conducted experiments. Each author contributed to experimental design and writing of the paper. M.D.B directed the project.

REFERENCES

- Afsharpour S. Topographical projections of the cerebral cortex to the subthalamic nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1985;236:14–28. doi: 10.1002/cne.902360103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:366–375. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton JF, Kitano K, Baufreton J, Fan K, Wokosin D, Tkatch T, Shigemoto R, Surmeier DJ, Bevan MD. Selective participation of somatodendritic HCN channels in inhibitory but not excitatory synaptic integration in neurons of the subthalamic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:16025–16040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3898-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baufreton J, Atherton JF, Surmeier DJ, Bevan MD. Enhancement of excitatory synaptic integration by GABAergic inhibition in the subthalamic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:8505–8517. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1163-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baufreton J, Kirkham E, Atherton JF, Menard A, Magill PJ, Bolam JP, Bevan MD. Sparse but selective and potent synaptic transmission from the globus pallidus to the subthalamic nucleus. J. Neurophysiol. 2009;102:532–545. doi: 10.1152/jn.00305.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baunez C, Nieoullon A, Amalric M. In a rat model of parkinsonism, lesions of the subthalamic nucleus reverse increases of reaction time but induce a dramatic premature responding deficit. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:6531–6541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06531.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan MD, Bolam JP. Cholinergic, GABAergic, and glutamate-enriched inputs from the mesopontine tegmentum to the subthalamic nucleus in the rat. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:7105–7120. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07105.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan MD, Magill PJ, Hallworth NE, Bolam JP, Wilson CJ. Regulation of the timing and pattern of action potential generation in rat subthalamic neurons in vitro by GABA-A IPSPs. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1348–1362. doi: 10.1152/jn.00582.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo PE, Chiu CQ, Carroll RC. Long-term plasticity at inhibitory synapses. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2011;21:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Glajch KE, Gertler TS, Guzman JN, Mercer JN, Lewis AS, Goldberg AB, Tkatch T, Shigemoto R, Fleming SM, Chetkovich DM, Osten P, Kita H, Surmeier DJ. HCN channelopathy in external globus pallidus neurons in models of Parkinson's disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:85–92. doi: 10.1038/nn.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier G, Deniau JM. Disinhibition as a basic process in the expression of striatal functions. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:277–280. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90109-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements JD, Silver RA. Unveiling synaptic plasticity: a new graphical and analytical approach. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coizet V, Graham JH, Moss J, Bolam JP, Savasta M, McHaffie JG, Redgrave P, Overton PG. Short-latency visual input to the subthalamic nucleus is provided by the midbrain superior colliculus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5701–5709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0247-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M, Wang Z, Ding J, An X, Ingham CA, Shering AF, Wokosin D, Ilijic E, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Mugnaini E, Deutch AY, Sesack SR, Arbuthnott GW, Surmeier DJ. Selective elimination of glutamatergic synapses on striatopallidal neurons in Parkinson disease models. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:251–259. doi: 10.1038/nn1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan KY, Baufreton J, Surmeier DJ, Chan CS, Bevan MD. Proliferation of external globus pallidus-subthalamic nucleus synapses following degeneration of midbrain dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:13718–13728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5750-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Kita H. Response characteristics of subthalamic neurons to the stimulation of the sensorimotor cortex in the rat. Brain Res. 1993;609:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90872-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, Wichmann T. Pathophysiology of parkinsonism. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008;119:1459–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Surmeier DJ. Modulation of striatal projection systems by dopamine. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;34:441–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittis AH, Hang GB, LaDow ES, Shoenfeld LR, Atallah BV, Finkbeiner S, Kreitzer AC. Rapid target-specific remodeling of fast-spiking inhibitory circuits after loss of dopamine. Neuron. 2011;71:858–868. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JA, Boraud T, Maraton S, Haber SN, Vaadia E, Bergman H. Enhanced synchrony among primary motor cortex neurons in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine primate model of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:4639–4653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04639.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallworth NE, Bevan MD. Globus pallidus neurons dynamically regulate the activity pattern of subthalamic nucleus neurons through the frequency-dependent activation of postsynaptic GABAA and GABAB receptors. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6304–6315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0450-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallworth NE, Wilson CJ, Bevan MD. Apamin-sensitive small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels, through their selective coupling to voltage-gated calcium channels, are critical determinants of the precision, pace, and pattern of action potential generation in rat subthalamic nucleus neurons in vitro. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:7525–7542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07525.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond C, Bergman H, Brown P. Pathological synchronization in Parkinson's disease: networks, models and treatments. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O, Takikawa Y, Kawagoe R. Role of the basal ganglia in the control of purposive saccadic eye movements. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:953–978. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holgado AJ, Terry JR, Bogacz R. Conditions for the generation of beta oscillations in the subthalamic nucleus-globus pallidus network. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:12340–12352. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0817-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomura Y, Harukuni R, Takekawa T, Aizawa H, Fukai T. Microcircuitry coordination of cortical motor information in self-initiation of voluntary movements. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:1586–1593. doi: 10.1038/nn.2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson N, Brown P. New insights into the relationship between dopamine, beta oscillations and motor function. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:611–618. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas P. Glutamate receptors in the central nervous system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993;707:126–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb38048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita T, Kita H. The subthalamic nucleus is one of multiple innervation sites for long-range corticofugal axons: a single-axon tracing study in the rat. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5990–5999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5717-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz AV, Freeze BS, Parker PR, Kay K, Thwin MT, Deisseroth K, Kreitzer AC. Regulation of parkinsonian motor behaviours by optogenetic control of basal ganglia circuitry. Nature. 2010;466:622–626. doi: 10.1038/nature09159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurotani T, Yamada K, Yoshimura Y, Crair MC, Komatsu Y. State-dependent bidirectional modification of somatic inhibition in neocortical pyramidal cells. Neuron. 2008;57:905–916. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange MD, Doengi M, Lesting J, Pape HC, Jüngling K. Heterosynaptic long-term potentiation at interneuron-principal neuron synapses in the amygdala requires nitric oxide signalling. J. Physiol. 2012;590:131–143. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.221317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Man H, Ju W, Trimble WS, MacDonald JF, Wang YT. Activation of synaptic NMDA receptors induces membrane insertion of new AMPA receptors and LTP in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2001;29:243–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher B, Fuchs T, Kilpatrick CL. GABAA receptor trafficking-mediated plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Neuron. 2011;70:385–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill PJ, Bolam JP, Bevan MD. Dopamine regulates the impact of the cerebral cortex on the subthalamic nucleus-globus pallidus network. Neuroscience. 2001;106:313–330. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation-a decade of progress? Science. 1999;285:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet N, Ballion B, Le Moine C, Gonon F. Cortical inputs and GABA interneurons imbalance projection neurons in the striatum of parkinsonian rats. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:3875–3884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4439-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet N, Pogosyan A, Márton LF, Bolam JP, Brown P, Magill PJ. Parkinsonian beta oscillations in the external globus pallidus and their relationship with subthalamic nucleus activity. J. Neurosci. 2008a;28:14245–14258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4199-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet N, Pogosyan A, Sharott A, Csicsvari J, Bolam JP, Brown P, Magill PJ. Disrupted dopamine transmission and the emergence of exaggerated beta oscillations in subthalamic nucleus and cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2008b;28:4795–4806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0123-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet N, Micklem BR, Henny P, Brown MT, Williams C, Bolam JP, Nakamura KC, Magill PJ. Dichotomous organization of the external globus pallidus. Neuron. 2012;74:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden KC, Beattie JB, Friedenthal J, Carroll RC. NMDA receptor activation potentiates inhibitory transmission through GABA receptor-associated protein-dependent exocytosis of GABA(A) receptors. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:14326–14337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4433-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice N, Deniau JM, Glowinski J, Thierry AM. Relationships between the prefrontal cortex and the basal ganglia in the rat: physiology of the corticosubthalamic circuits. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9539–9546. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09539.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice N, Deniau JM, Glowinski J, Thierry AM. Relationships between the prefrontal cortex and the basal ganglia in the rat: physiology of the cortico-nigral circuits. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:4674–4681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04674.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink JW, Thach WT. Basal ganglia intrinsic circuits and their role in behavior. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1993;3:950–957. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90167-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monakow KH, Akert K, Künzle H. Projections of the precentral motor cortex and other cortical areas of the frontal lobe to the subthalamic nucleus in the monkey. Exp. Brain. Res. 1978;33:395–403. doi: 10.1007/BF00235561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran RJ, Mallet N, Litvak V, Dolan RJ, Magill PJ, Friston KJ, Brown P. Alterations in brain connectivity underlying beta oscillations in Parkinsonism. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1002124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu A, Tokuno H, Takada M. Functional significance of the cortico-subthalamo-pallidal 'hyperdirect' pathway. Neurosci. Res. 2002;43:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet AP, Foster OJ, Kingsbury A, Lees AJ, Marsden CD. Nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression in human subthalamic nucleus, striatum and globus pallidus: implications for basal ganglia function. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1994;22:329–332. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent FS, Penick EC, Kauer JA. Opioids block long-term potentiation of inhibitory synapses. Nature. 2007;446:1086–1090. doi: 10.1038/nature05726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka T, Murakami F, Song WJ. Excitatory postsynaptic potentials trigger a plateau potential in rat subthalamic neurons at hyperpolarized states. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1816–1825. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouardouz M, Sastry BR. Mechanisms underlying LTP of inhibitory synaptic transmission in the deep cerebellar nuclei. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1414–1421. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patenaude C, Chapman CA, Bertrand S, Congar P, Lacaille JC. GABAB receptor- and metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent cooperative long-term potentiation of rat hippocampal GABAA synaptic transmission. J Physiol. 2003;553:155–167. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz JT, Deniau JM, Charpier S. Rhythmic bursting in the cortico-subthalamo-pallidal network during spontaneous genetically determined spike and wave discharges. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2092–2101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4689-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YR, Zeng SY, Song HY, Li MY, Yamada MK, Yu X. Postsynaptic spiking homeostatically induces cell-autonomous regulation of inhibitory inputs via retrograde signaling. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:16220–16231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3085-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pifarre P, Garcia A, Mengod G. Species differences in the localization of soluble guanylyl cyclase subunits in monkey and rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;500:942–957. doi: 10.1002/cne.21241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen KZ, Johnson SW. Dopamine depletion alters responses to glutamate and GABA in the rat subthalamic nucleus. Neuroreport. 2005;16:171–174. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200502080-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen KZ, Zhu ZT, Munhall A, Johnson SW. Synaptic plasticity in rat subthalamic nucleus induced by high-frequency stimulation. Synapse. 2003;50:314–319. doi: 10.1002/syn.10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamoto SA, Ryapolova-Webb ES, Ostrem JL, Galifianakis NB, Miller KJ, Starr PA. Subthalamic nucleus neurons are synchronized to primary motor cortex local field potentials in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:7220–7233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4676-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Bevan MD, Shink E, Bolam JP. Microcircuitry of the direct and indirect pathways of the basal ganglia. Neuroscience. 1998;86:353–387. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Bolam JP, Von Krosigk M. Topographical and synaptic organization of the GABA-containing pallidosubthalamic projection in the rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1990;2:500–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1990.tb00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Kittler JT. The cell biology of synaptic inhibition in health and disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010;20:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana Y, Iwamuro H, Kita H, Takada M, Nambu A. Subthalamo-pallidal interactions underlying parkinsonian neuronal oscillations in the primate basal ganglia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011;34:1470–1484. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana Y, Kita H, Chiken S, Takada M, Nambu A. Motor cortical control of internal pallidal activity through glutamatergic and GABAergic inputs in awake monkeys. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008;27:238–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant KA, Adkins DL, Donlan NA, Asay AL, Thomas N, Kleim JA, Jones TA. The organization of the forelimb representation of the C57BL/6 mouse motor cortex as defined by intracortical microstimulation and cytoarchitecture. Cereb. Cortex. 2011;21:865–876. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman D, Rubin JE, Yew AC, Wilson CJ. Activity patterns in a model for the subthalamopallidal network of the basal ganglia. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:2963–2976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02963.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien JZ, Chen DF, Gerber D, Tom C, Mercer EH, Anderson DJ, Mayford M, Kandel ER, Tonegawa S. Subregion- and cell type-restricted gene knockout in mouse brain. Cell. 1996;87:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G. Too many cooks? Intrinsic and synaptic homeostatic mechanisms in cortical circuit refinement. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;34:89–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagarajan SK, Fritschy JM. GABAA receptors, gephyrin and homeostatic synaptic plasticity. J. Physiol. 2010;588:101–106. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vithlani M, Terunuma M, Moss SJ. The dynamic modulation of GABA(A) receptor trafficking and its role in regulating the plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Physiol. Rev. 2011;91:1009–1022. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Kitai ST, Xiang Z. Activity-dependent bidirectional modification of inhibitory synaptic transmission in rat subthalamic neurons. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:7321–7327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4656-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ. Stereological methods for estimating the total number of neurons and synapses: issues of precision and bias. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.