Abstract

Introduction

Individuals with Social Phobia (SP) represent a large group with elevated rates of cigarette smoking and cessation rates lower than that of individuals without psychopathology. For individuals with SP, cigarette smoking may be used to reduce social anxiety in anticipation of and during social situations. However, no study to date has experimentally examined this association. The aim of the current study was to experimentally examine the relationship between cigarette smoking and SP as a function of induced social stress.

Method

We recruited daily smokers ages 18–21 who scored in either a clinical or normative range on the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS). Participants included 54 smokers (42.6% female, 77.8% White, Age M(SD)=19.65(1.18), CPSD M(SD)=7.67(4.36), 46.30% high SP) who attended two sessions: one social stress session and one neutral session.

Results

Results indicated that high SP smokers experienced significant decreases in negative affect following smoking a cigarette when experiencing social stress. This effect was specific to high SP smokers under social stress and was not observed among individuals average in SP or when examining changes in positive affect.

Conclusions

For individuals with SP, cigarette smoking may be maintained due to changes in NA associated with smoking specifically in the context of social stress. These results speak to the importance of targeted cessation interventions that address the nature of smoking for individuals with SP.

Keywords: Social phobia, Tobacco

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Cigarette smoking and Social Phobia

Individuals with psychological disorders are overrepresented among U.S. smokers, experience a disproportionate amount of the smoking-related public health burden, and, as such, are an important target for prevention and intervention efforts (Schroeder & Morris, 2010). Psychological comorbidities for which cigarette smoking may be used to cope with or manage psychological symptoms may be the most problematic for smoking outcomes (Gehricke et al., 2007). A growing body of research suggests that Social Phobia (SP), a highly prevalent disorder for which 12.1% of the population meets diagnostic criteria (Ruscio et al., 2008), exhibits this relationship with tobacco use such that SP symptoms predict the initiation of cigarette smoking (Johnson et al., 2000), nicotine dependence (Sonntag et al., 2000), and poor cessation outcomes (Lasser et al., 2000; Ruscio et al., 2008). Moreover, there are significantly greater rates of smoking among individuals with SP than among individuals without psychological comorbidities; specifically, 54.0% of individuals with SP are lifetime smokers and 35.9% of individuals with SP are current smokers (Lasser et al., 2000; Ruscio et al., 2008).

In teasing apart potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between cigarette smoking and SP, a negative reinforcement model is relevant. From a negative reinforcement framework, individuals with SP would smoke cigarettes in order to reduce or avoid feelings of distress in relation to social situations or in anticipation of social situations. There has been some support for this negative reinforcement link between SP and cigarette smoking in early adolescence prior to the onset of regular smoking such that adolescents high in SP report greater urge to smoke during peer interactions than adolescents without elevated SP symptoms (Henry et al., 2012), suggesting that tobacco use may develop and escalate as a method to regulate social anxiety.

Strong theory and etiological data suggest the temporal ordering of SP, cigarette smoking onset, and nicotine dependence (e.g., Sonntag et al., 2000). However, there are only a few studies that have examined the functional utility of cigarette smoking for individuals with SP symptomatology. The studies that have examined smoking and SP suggest that SP symptoms are positively related to self-reported smoking to cope behaviors during social situations as well as to cigarette craving when deprived of nicotine (Watson et al., 2012). Furthermore, the relationship between SP symptoms and nicotine dependence is mediated by affiliative attachment motives, suggesting that among individuals with elevated SP symptomatology, cigarette smoking may help to cope with the feelings of loneliness or social rejection associated with SP (Buckner & Vinci, 2013). Other studies have not specifically assessed SP symptomatology, but have utilized experimental manipulations to induce social stress among samples of smokers and have found that in response to social stress, urge to smoke is positively associated with self-reported and observer-reported anxiety (Niaura, Shadel, Britt, & Abrams, 2002) and that, in turn, smoking a cigarette is related to lower levels of self-reported anxiety (Gilbert & Spielberger, 1987). Taken together, these studies further support a unique negative reinforcement relationship between SP and tobacco use.

There are several remaining gaps in the literature on SP and cigarette smoking. Although self-report data from Watson and colleagues (2012) suggests that SP is related to smoking to cope with social situations, this relationship has yet to be experimentally examined and it remains unclear whether cigarette smoking modulates negative affect (NA) associated with social stress for socially phobic smokers. Additionally, no studies to date have assessed smoking behavior (i.e., via smoking topography) among socially phobic smokers in response to social stress. Thus, it remains unknown whether self-reported smoking to cope translates to differential smoking in response to a social stressor as compared to in response to a neutral mood.

1.2 Current study

Towards addressing these gaps in the extant literature, the primary aims of the current study were two-fold: 1) To examine the relationship between level of SP (high SP, healthy control with average SP) and cigarette smoking-related outcomes (smoking topography) as a function of induced social stress (neutral, stress) and 2) To examine the relationship between level of SP (high SP, healthy control with average SP) and NA as a function of induced social stress (neutral, stress). We hypothesized that in response to a social stressor, high SP smokers as compared to average SP smokers, would have: 1) greater smoking outcomes (greater puff number, greater puff volume, shorter interpuff interval (IPI) on measures of smoking topography) and 2) greater NA modulation as a function of smoking evidenced by significant increases in NA in anticipation of a social stressor followed by significant decreases in NA after smoking a cigarette.

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited from the University of Maryland, College Park campus using flyers and postings online. Interested individuals were advised to contact the study by phone or e-mail to complete an online screening to determine eligibility. Inclusion criteria for the study was as follows: 1) ages 18–21, 2) current regular smoking defined as smoking ≥ 5 cigarettes/smoking day (CPSD) for the past 6 months and smoking on ≥ 20 out of the last 30 days, and 3) score of either > 35 or between 9 and 24 on the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998). The SIAS cutoff values were selected in order to remain consistent with previous research (Mattick & Clarke, 1998). In the initial validation study of the SIAS, Mattick and Clarke (1998) found that individuals with SP had a mean of 34.6 with a standard deviation of 16.4 on the SIAS and that undergraduate students had a mean of 19.4 with a standard deviation of 10.1. Thus, in the present study, to categorize between high and average SP groups, the high SP group was at or above the SP sample mean (above 35) and the average SP group was within 1 standard deviation below and 0.5 standard deviations above the undergraduate mean (9–24).

In total, 73 participants attended at least one experimental session. From this sample of 73, three did not attend one of the experimental sessions, seven did not smoke at least one of the cigarettes, eight had missing topography data due to errors with topography equipment, and one had missing affect data, resulting in a final sample of 54 (42.6% female, Age M(SD) = 19.65(1.18), n = 25 High SP; Table 1). Those who were included in the final sample did not significantly differ from those who were excluded on age, gender, race/ethnicity, SP status, or CPSD (all p’s >.05).

Table 1.

Demographics, Smoking Topography, and PANAS

| Full Sample (n=54) |

High SP (n=25) |

Average SP (n=29) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Age M(SD) | 19.65(1.18) | 19.80(1.19) | 19.52(1.18) |

| Gender (% female) | 42.6% | 56.0% | 31.0% |

| Racial/ethnic background | |||

| White | 77.8% | 72.0% | 82.8% |

| Black or African American | 5.6% | 12.0% | 0% |

| Asian or Asian American | 11.1% | 8.0% | 13.8% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3.7% | 4.0% | 3.4% |

| Other | 1.9% | 4.0% | 0% |

| Age of smoking initiation M(SD) | 15.59(2.62) | 15.72(2.79) | 15.48(2.52) |

| Cigarettes per smoking day M(SD)* | 7.67(4.36) | 9.02(4.74) | 6.51(3.69) |

| SMOKING TOPOGRAPHY | |||

| Neutral Session | |||

| Cigarette 1 M(SD) | |||

| Number of puffs | 15.43(5.35) | 15.84(4.75) | 15.07(5.89) |

| Puff volume (ml) | 47.08(23.23) | 44.39(25.13) | 49.40(21.64) |

| Total puff volume (ml) | 669.27(300.60) | 674.30(374.10) | 664.85(225.92) |

| Interpuff Interval (s) | 14.04(5.94) | 13.13(5.83) | 14.82(6.02) |

| Cigarette 2 M(SD) | |||

| Number of puffs | 15.56(6.01) | 15.88(5.45) | 15.28(6.55) |

| Puff volume (ml) | 42.70(20.00) | 42.33(23.35) | 43.02(17.00) |

| Total puff volume (ml) | 630.03(327.38) | 660.93(418.53) | 603.40(226.15) |

| Interpuff Interval (s) | 14.88(8.82) | 14.15(7.00) | 15.52(10.21) |

| Stress Session | |||

| Cigarette 1 M(SD) | |||

| Number of puffs | 15.06(5.45) | 15.00(5.49) | 15.10(5.51) |

| Puff volume (ml) | 43.98(18.40) | 38.88(13.53) | 48.37(21.00) |

| Total puff volume (ml) | 641.64(285.52) | 592.68(310.02) | 683.84(260.66) |

| Interpuff Interval (s) | 14.70(7.18) | 13.66(6.37) | 15.60(7.81) |

| Cigarette 2 M(SD) | |||

| Number of puffs | 15.11(5.28) | 15.88(5.81) | 14.45(4.77) |

| Puff volume (ml) | 46.17(31.00) | 46.46(41.76) | 45.93(18.00) |

| Total puff volume (ml) | 647.81(341.80) | 673.61(423.42) | 625.57(257.60) |

| Interpuff Interval (s) | 14.41(6.85) | 13.31(5.71) | 15.36(7.67) |

| PANAS | |||

| Neutral Session | |||

| Administration 1 M(SD) | |||

| Positive Affect | 25.52(6.62) | 25.60(6.35) | 25.45(6.96) |

| Negative Affect | 13.83(4.86) | 14.64(3.86) | 13.14(5.55) |

| Administration 2 M(SD) | |||

| Positive Affect | 24.22(7.81) | 24.36(7.69) | 24.10(8.05) |

| Negative Affect | 12.07(4.14) | 11.76(2.35) | 12.34(5.25) |

| Administration 3 M(SD) | |||

| Positive Affect | 24.56(8.73) | 24.64(9.58) | 24.48(8.10) |

| Negative Affect | 12.48(3.64) | 12.68(2.19) | 12.31(4.58) |

| Stress Session | |||

| Administration 1 M(SD) | |||

| Positive Affect | 25.21(6.21) | 25.06(6.02) | 25.34(6.48) |

| Negative Affect | 14.61(5.94) | 15.48(5.62) | 13.86(6.20) |

| Administration 2 M(SD) | |||

| Positive Affect | 25.76(7.70) | 23.76(7.68) | 27.48(7.42) |

| Negative Affect | 19.78(7.55) | 23.24(7.96) | 16.79(5.80) |

| Administration 3 M(SD) | |||

| Positive Affect | 26.03(8.42) | 24.08(7.92) | 27.72(8.61) |

| Negative Affect | 16.59(6.04) | 18.16(6.43) | 15.24(5.44) |

p < .05

2.2 Measures

Smoking history and current smoking information

Smoking history was assessed using the smoking history and current status indices agreed upon by a NCI consensus panel (Shumaker & Grunberg, 1986). Nicotine dependence was assessed using the modified version of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire (mFTQ; Prokhorov et al., 2000). Timeline Follow-back (TLFB; Brown et al., 1998) procedures were used to index number of cigarettes smoked.

Social phobia

The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998) was used as a measure of SP symptomatology. The SIAS is a 20-item measure designed to assess level of anxiety associated with the initiation and maintenance of social interactions using a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 to 4 (i.e., not at all characteristic or true of me to extremely characteristic or true of me).

Affect

The 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) was used to measure positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA). The PANAS commonly is used to detect changes in emotional reactions to stimuli in the manner proposed here. The NA score was calculated by taking the sum of ratings for the 10 NA items and the PA score was calculated by taking the sum of ratings for the 10 PA items. The measure was administered three times during each session.

Smoking outcomes

CReSSmicro (Plowshare Technologies, Inc., Baltimore, MD) is a battery-operated portable device that measures smoking topography variables (puff volume, puff number, puff duration, average flow, IPI, time, and date). From the basic topography measurements, we calculated four key variables of interest: 1) Total number of puffs for each cigarette, 2) Mean puff volume, defined as the average volume of all measured puffs, 3) Total puff volume, defined as the sum of all measured puff volumes, and 4) Mean IPI, defined as the average amount of time between measured puffs.

2.3 Procedure

The study consisted of two sessions held at the Center for Addictions, Personality and Emotion Research at the University of Maryland College Park. All procedures were approved by the University of Maryland’s Institutional Review Board.

Screening

The online screening included questions about demographics, smoking behavior, and completion of the SIAS. If eligible for the study, participants were contacted via email or phone for scheduling and asked to bring at least two cigarettes of their preferred brand to each of the experimental sessions.

Experimental sessions

Condition order was counterbalanced and, with the exception of video content, the sessions followed identical procedures. Following completion of consent procedures, participants were escorted outside and given the option to smoke a cigarette through the CReSSmicro. The purpose of smoking this cigarette at the beginning of each session was to standardize time since last cigarette smoked and to allow participants to acclimate to the topography mouthpiece. Participants then completed self-report measures (Smoking history or mFTQ, PANAS (administration 1)) in a separate room. During session 1, participants completed the TLFB for cigarettes smoked in the past month while, during session 2, participants completed the TLFB for the time between sessions 1 and 2. Because the mFTQ and NCI smoking history indices are stable over short time periods, they were counterbalanced between sessions 1 and 2.

Following measure completion, participants watched a control video (nature video) or a social stressor video previously used in similar social stress mood induction experimental paradigms (Reynolds et al., 2013). The control video was validated by Rottenberg, Ray, & Gross (2007) to induce a neutral mood and has been used in other experimental studies implementing affect manipulation to study cigarette smoking (e.g., Fucito & Juliano, 2009). The social stressor video was adapted from the Trier Social Stress Test (Kirschbaum, Pirke, & Hellhammer, 1993) and video anxiety induction procedures (Tovilović, Novović, Mihić, & Jovanović, 2009). Briefly, participants were told that they would be giving a speech to a panel of judges who would judge the quality of their speech and that they would then watch an example video of past participants giving their speeches. After watching the video, all participants were told that the speech topic that had been randomly selected for that day was to give a speech about the parts of their body they liked the least and why they liked them the least. After video presentation, participants completed the PANAS (administration 2) and were then given the option to smoke a cigarette through the CReSSmicro. After smoking this second cigarette, participants completed the PANAS (administration 3). At the end of the session, participants were debriefed and compensated for participation.

2.4 Analytic strategy

All data were analyzed using SPSS v22. We first explored the impact of potential covariates (age, race/ethnicity, gender, and CPSD) on the dependent variables of interest (NA, PA, topography variables) using repeated measures ANOVAs. After determining covariates to be included in analyses to address the primary study aims, we used repeated measures ANOVA analyses to examine within and between group (High vs. Average SP) differences in the dependent variables of interest (smoking topography, NA, PA) as a function of condition (Neutral vs. Social Stress). To address the first study aim, we used four (one for each topography dependent variable) 2x2 mixed factorial repeated measures ANOVAs to examine changes in smoking topography outcomes (number of puffs, average volume, total volume, IPI) as a function of SP group and session. To address the second study aim, we used a 3x2x2 mixed factorial repeated measures ANOVA in order to examine changes in affect as a function of SP group, session, and time (PANAS administration within each session). We examined the interactive effect of group, condition, and time on PA as well as NA in order to determine whether effects were unique to NA or consistent across both NA and PA regulation.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Descriptive findings

Cigarette Smoking

Average CPSD for the sample was M(SD)=7.67(4.36). On average, participants first smoked at age 15.59(2.62), began smoking weekly at age 17.46(1.63), and began smoking daily at age 18.19(1.35). mFTQ Levels were relatively low (M(SD) = 4.04(1.27)). High SP individuals reported smoking significantly more CPSD (M(SD)=9.02(4.74)) than average SP (M(SD)= 6.51(3.69)) individuals [F(1,52)=4.76, p=.03].

Puff Topography

Across the two experimental sessions, participants smoked four cigarettes: one in each session prior to video presentation (Cigarette 1) and one following video presentation (Cigarette 2). Topography data is presented in Table 1. There were no significant SP group differences in any of the topography variables.

Affect

Participants completed affect ratings three times during each experimental session. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics for PA and NA at each administration of the PANAS.

3.2 Determining covariates to be included in subsequent analyses

There were no significant effects of any of the potential covariates on any of the dependent variables (all p’s >.05). As such, we did not include demographic variables as covariates in subsequent analyses. However, in order to ensure that group (High vs. Average SP) differences in CPSD were not driving associations between SP, condition, and outcome (PA, NA, topography), we included CPSD as a covariate in all subsequent analyses.

3.3 Smoking outcomes as a function of SP level and condition

To determine whether smoking outcomes differed between conditions based on SP level, we utilized one 2x2 mixed factorial repeated measures ANOVA covarying for CPSD for each topography variable of interest. These analyses revealed no significant between- or within-subjects interactions between SP group and condition on topography variables (all p’s >.05).

3.4 NA and PA as a function of SP level, condition, and time

NA omnibus repeated measures ANOVA

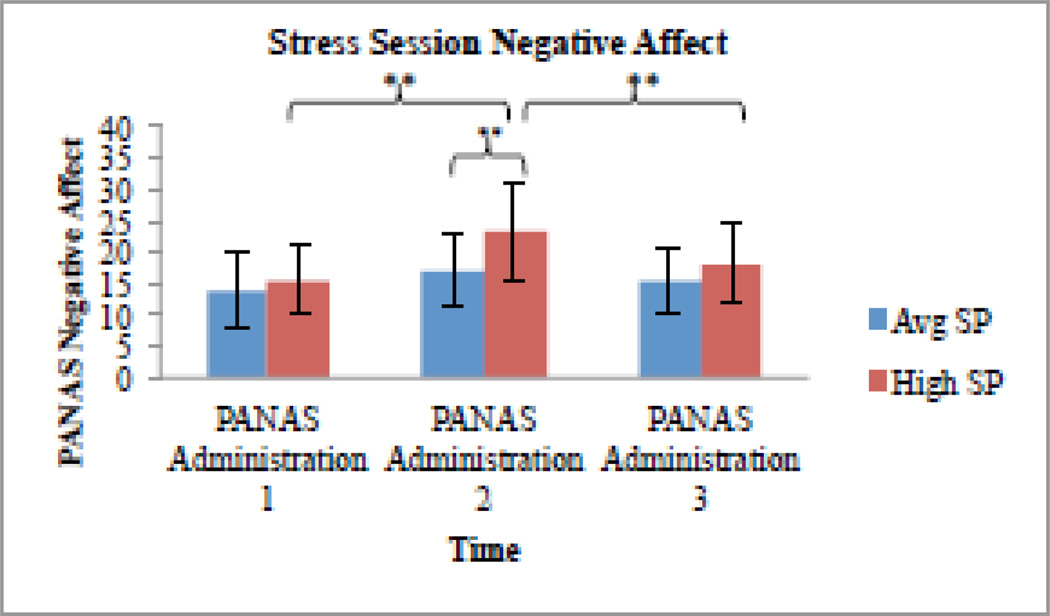

Results indicated a significant three-way interaction of condition, time (PANAS administration), and SP status [(F(2, 50) = 4.18, p = .02] on NA when covarying for CPSD. Main effects of condition, time, and SP status were nonsignificant as well as the two-way interactions between session and SP status, time and SP status, and session and time. We then probed the three-way interaction by session. During the neutral session, the within-subjects two-way interaction between time and SP status was nonsignificant [F(2,102)=2.43, p=.09], suggesting that there were no group differences in change in NA during the neutral session. During the stress session, there was a significant between-subjects effect of SP status on NA [F(1,51)=5.16, p=.03] as well as a significant within-subjects two-way interaction between time and SP status [F(2,102)=3.17, p=.05]. We then probed this two-way interaction by SP group. For the average SP group, there was not a significant within-subjects effect of time on NA during the stress session [F(2,54)=0.25, p=.78], suggesting that NA did not significantly change during the course of the stress session. For the high SP group, the within-subjects effect of time on NA during the stress session was significant [F(2,46)=3.26, p=.05]. Specifically, a paired-samples t-test revealed that for the high SP group during the stress session, NA significantly increased following administration of the social stressor (t(24)=−5.41, p<.001) and then significantly decreased after smoking the second cigarette (t(24)=4.88, p<.001; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relationship between SP group and NA during the social stress session. PANAS administration 1 occurred prior to the social stressor, PANAS administration 2 occurred immediately following the social stressor, before smoking the second cigarette, and PANAS administration 3 occurred following smoking the second cigarette. There was a significant between-subjects effect of SP group on NA PANAS Administration 2 such that High SP individuals were significantly higher in NA. There were also significant within-subjects effects such that High SP significantly increased in NA from PANAS administration 1 to PANAS administration 2 and significantly decreased in NA from PANAS administration 2 to PANAS administration 3. Note: ** p<.01

PA omnibus repeated measures ANOVA

The three-way interaction between condition, time (PANAS administration), and SP status was nonsignificant [(F(2, 50)=1.59, p=.22] as well as the main effects of SP status, condition, and time, and the two-way interactions between SP status and condition, SP status and time, and condition and time.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1 Summary of main findings

The present study provides an experimental examination of the relationship between SP, social stress, cigarette smoking, and affect in order to understand the functional role of cigarette smoking for individuals with SP symptomatology. Regarding the first study aim, we did not find significant SP group by condition effects on smoking topography outcomes. There are two plausible explanations for this finding. First, we were interested in individuals between the ages of 18 and 21 and recruited a sample consisting of relatively light smokers with low levels of nicotine dependence. Thus, variability in topography across sessions was possibly limited. Second, it is possible that the function of cigarette smoking among high SP individuals under social stress is to regulate NA, which may operate independently from the pharmacological effects of nicotine.

Regarding the second study aim, High SP individuals reported significant increases in NA when told they would have to give a speech. After smoking a cigarette, while still anticipating having to give a speech, the high SP group reported significantly decreased NA from the prior time point. This effect was specific to the High SP group and was specific to NA regulation. Taken together with results from the first study aim, this suggests that while high SP individuals do not change their smoking behavior when experiencing social stress, cigarette smoking significantly reduces NA under social stress. Thus, NA regulation when experiencing social stress may be one factor that maintains cigarette smoking in individuals with SP or with elevated SP symptoms.

This study builds upon previous literature which suggests that SP symptoms are a risk factor for cigarette smoking (Morissette et al., 2007) and points to one possible mechanism, relief of NA in the face of social stress, that may maintain tobacco use over time among individuals with elevated SP symptomatology. Whereas previous studies have found that SP symptoms are positively related to self-reported smoking to cope in social situations (Watson et al., 2012), the present study further supports this notion that cigarette smoking facilitates alleviation of NA in the context of social stress for socially phobic smokers. Additionally, this study extends previous literature suggesting that relief from NA following cigarette smoking may operate independently from nicotine consumption (e.g., Perkins et al., 2010). As suggested by Perkins and colleagues (2010), the effects of smoking, especially in regards to NA, may not be due to the pharmacological effects of nicotine, but rather due to conditioned responses and the reinforcement of these conditioned responses over time. With the results of the present study in mind, this conditioned response pattern may be critical for smokers with elevated SP symptoms in the context of social stress and may be key to the development of efficacious smoking prevention and smoking cessation interventions for this group.

4.2 Limitations

Results from the present study should be interpreted with limitations in mind. First, although they smoked regularly, participants in the study were relatively low quantity smokers with low levels of nicotine dependence. As such, generalizability may be limited. Second, our sample size was relatively small and it is possible that our null topography results were due to lack of power to detect an effect. Third, we did not standardize nicotine content across participants and group differences by condition in amount of nicotine self-administered are possible. Fourth, we did not include an additional control condition in which participants were exposed to the stressor, but did not have the option to smoke. We made this decision in order to minimize participant burden and attrition, as including this additional control would have required participants to attend three experimental sessions. However, in the absence of such a control condition, we are unable to determine whether the observed effects of SP and social stress on NA are only due to smoking a cigarette. Finally, because this study is explorative in nature, we made the decision not to constrain the alpha level for multiple probes, which may have led to an increase in Type I error. In light of this, findings bordering on traditional significance levels, specifically the significant two-way interaction between time and SP status during the stress session and the significant within-subjects effect of time on NA during the stress session, should be interpreted with caution and warrant replication.

4.3 Conclusions and future directions

The present study is the first to our knowledge to experimentally examine the functional relationship between SP, cigarette smoking, and social stress and implicates the role of NA regulation in the context of social stress as a factor that maintains cigarette smoking for individuals with SP. Although high SP individuals did not smoke differently in the context of social stress as compared to a neutral condition or when compared to average SP individuals, following smoking a cigarette when experiencing social stress, high SP individuals experienced significantly reduced NA. This NA reduction fits within existing negative reinforcement frameworks for the maintenance of cigarette smoking and extends this framework to a specific high risk group in the context of a high risk situation. Incorporating NA regulatory strategies for socially stressful situations may help to both prevent smoking initiation and improve cessation rates among individuals with SP or elevated SP symptoms.

There are a number of important future directions from this line of research. To further explore the relationship between the pharmacologic effects of nicotine on NA and reinforcement-based learning on NA as it relates to SP, future experimental studies could experimentally manipulate the nicotine content of cigarettes to further disentangle this relationship. Additionally, as the onset of SP tends to precede the onset of cigarette smoking, preventative interventions incorporating NA regulation skills may be especially important for children and adolescents with SP or with elevated symptoms of SP in order to decrease the likelihood of smoking initiation. Further, NA regulation strategies specifically addressing social situations may be especially important for improving cessation rates among smokers with SP or with elevated SP symptoms.

Highlights.

We recruited smokers either high or average in Social Phobia (SP) symptoms.

Participants attended two experimental sessions: one neutral and one social stress.

There were no significant SP group by condition effects on smoking topography.

Smoking decreased negative affect for high SP smokers under social stress.

This effect was specific to high SP smokers under social stress.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by NIDA grant 1F31DA034999 to Jennifer Dahne. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Jennifer Dahne conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the statistical analyses, and was the lead in manuscript preparation. Leanne Hise and Misha Brenner assisted in running the study and in manuscript revisions. Carl Lejuez and Laura MacPherson supervised all aspects of the study and extensively edited and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

The authors acknowledge Dr. Thomas Eissenberg for generously lending smoking topography devices.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12(2):101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Vinci C. Smoking and social anxiety: The roles of gender and smoking motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(8):2388–2391. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucito LM, Juliano LM. Depression moderates smoking behavior in response to a sad mood induction. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(3):546. doi: 10.1037/a0016529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehricke J-G, Loughlin SE, Whalen CK, Potkin SG, Fallon JH, Jamner LD, Leslie FM. Smoking to self-medicate attentional and emotional dysfunctions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(Suppl 4):S523–S536. doi: 10.1080/14622200701685039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, Spielberger CD. Effects of smoking on heart rate, anxiety, and feelings of success during social interaction. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1987;10(6):629–638. doi: 10.1007/BF00846659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry SL, Jamner LD, Whalen CK. I (should) Need a Cigarette: Adolescent Social Anxiety and Cigarette Smoking. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;43(3):383–393. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS. Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(18):2348–2351. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke K-M, Hellhammer DH. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28(1–2):76–81. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd J, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Clarke JC. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36(4):455–470. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette SB, Tull MT, Gulliver SB, Kamholz BW, Zimering RT. Anxiety, anxiety disorders, tobacco use, nicotine: A critical review of interrelationships. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(2):245–272. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura R, Shadel WG, Britt DM, Abrams DB. Response to social stress, urge to smoke, and smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(2):241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Conklin CA, Sayette MA, Giedgowd GE. Acute negative affect relief from smoking depends on the affect situation and measure but not on nicotine. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(8):707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, De Moor C, Pallonen UE, Suchanek Hudmon K, Koehly L, Hu S. Validation of the modified Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire with salivary cotinine among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(3):429–433. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds EK, Schreiber WM, Geisel K, MacPherson L, Ernst M, Lejuez C. Influence of social stress on risk-taking behavior in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(3):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Ray RD, Gross JJ. Handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. Seires in affective science. New York, NY: Oxford University press; 2007. Emotion elicitation using films; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Brown TA, Chiu WT, Sareen J, Stein MB, Kessler RC. Social fears and social phobia in the USA: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(01):15–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder SA, Morris CD. Confronting a neglected epidemic: tobacco cessation for persons with mental illnesses and substance abuse problems. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:297–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker S, Grunberg N. Proceedings of the national working conference on smoking relapse. Health Psychology. 1986;5(supplement 1):99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag H, Wittchen H, Höfler M, Kessler R, Stein M. Are social fears and DSM-IV social anxiety disorder associ7ated with smoking and nicotine dependence in adolescents and young adults? European Psychiatry. 2000;15(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovilović S, Novović Z, Mihić L, Jovanović V. The role of trait anxiety in induction of state anxiety. Psihologija. 2009;42(4):491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson NL, VanderVeen JW, Cohen LM, DeMarree KG, Morrell HE. Examining the interrelationships between social anxiety, smoking to cope, and cigarette craving. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(8):986–989. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]