Abstract

In this study we characterized Amblyomma americanum (Aam) tick calreticulin (CRT) homolog in tick feeding physiology. In nature, different tick species can be found feeding on the same animal host. This suggests that different tick species found feeding on the same host can modulate the same host anti-tick defense pathways to successfully feed. From this perspective it’s plausible that different tick species can utilize universally conserved proteins such as CRT to regulate and facilitate feeding. CRT is a multi-functional protein found in most taxa that is injected into the vertebrate host during tick feeding. Apart from it’s current use as a biomarker for human tick bites, role(s) of this protein in tick feeding physiology have not been elucidated. Here we show that annotated functional CRT amino acid motifs are well conserved in tick CRT. However our data show that despite high amino acid identity levels to functionally characterized CRT homologs in other organisms, AamCRT is apparently functionally different. Pichia pastoris expressed recombinant (r) AamCRT bound C1q, the first component of the classical complement system, but it did not inhibit activation of this pathway. This contrast with reports of other parasite CRT that inhibited activation of the classical complement pathway through sequestration of C1q. Furthermore rAamCRT did not bind factor Xa in contrast to reports of parasite CRT binding factor Xa, an important protease in the blood clotting system. Consistent with this observation, rAamCRT did not affect plasma clotting or platelet aggregation aggregation. We discuss our findings in the context of tick feeding physiology.

Keywords: Amblyomma americanum, tick calreticulin, tick-feeding physiology

Introduction

In nature different tick species can be found feeding on the same animal host simultaneously (Durden et al., 1991, Kollars et al., 1997). This implies that different species of ticks that feed on the same host have to overcome the same host anti-tick defense mechanisms to complete feeding. This may raise questions of whether or not different species of ticks that feed on the same animal host can utilize orthologous tick saliva proteins to mediate the evasion of the host’s anti-tick feeding defense responses. One such highly conserved tick saliva protein is tick calreticulin (CRT) (Xu et al., 2004, 2005, Gao et al., 2008).

CRT was originally identified as a high calcium (Ca2+) binding protein from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of rabbit muscle (Ostwald and MacLennan, 1974, Fliegel et al., 1989). Coding cDNAs have now been identified in multiple organisms including ticks (Jaworski et al., 1995, Ferreira et al., 2002, Xu et al., 2004, 2005, Kaewhom et al., 2008, Gao et al., 2008), fleas (Jaworski et al., 1996), nematodes (Smith, 1992, Huggins et al., 1995, Tsuji et al., 1998, Scott et al., 1999, Mendlovic et al., 2004, Cabezón et al., 2008, Li et al., 2011), protozoan parasites (Aguillón et al., 2000, Marcelain et al., 2000, González et al., 2002), fish (Kales et al., 2004, Bai et al., 2012) and plants (Jia et al., 2008, Jin et al., 2009, An et al., 2011). Many more CRT sequences have been deposited in GenBank unpublished as direct submissions. For example, at the time of this write up, searching the NCBI sequence database with the key word “calreticulin and Ixodidae” retrieved 92 records.

In mammals where the bulk of data has been collected, CRT has been linked to both intracellular and extracellular functions, in health and disease (Holoshitz et al., 2010, Martins et al., 2010, Gold et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2012). The role of CRT in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis associates this protein with multiple functions including heart muscle function, adipocyte differentiation and cellular stress responses (Tarr et al., 2010, Van Duyn Graham et al., 2010 Wang et al., 2012). Likewise at the extracellular level, CRT is linked to multiple functions such as in wound healing, the immune response, cell adhesion and migration, fibrosis, cancer pathogenesis, and anti-thrombotic functions (Gold et al., 2006, Nanney et al., 2008). In plants, CRT proteins have been linked to regulating plant growth and mediating the plant response to biotic and abiotic stress and plant defense mechanisms (Qiu et al., 2012a, 2012b). In hematophagous parasites, CRT proteins are thought to play role(s) in mediation of evasion of host defense mechanisms by invertebrate, protozoan and helminth parasites (Schroeder et al., 2009). In Trypanosoma carassii (Oladiran and Belosevic 2010), T cruzi (Ferreira et al., 2004a, 2004b, Ramírez et al., 2011), Entomoeba histolytica (Vaithilingam et al., 2012) and helminthes, Hemonchus contortus (Naresha et 2009), and Nector anericanus (Kasper et al., 2001) have been shown to interfere with activation of the classical complement pathway by binding and sequestering the C1q protein, the initiator component of this pathway. Additionally H. contortus CRT has also been implicated in mediating the anticoagulant function of this parasite by sequestering blood coagulation factors, factor Xa and the C-reactive protein (Suchitra and Joshi, 2005, Suchitra et al., 2008). Likewise, the rodent intestinal nematode, Heligmosomoides polygyrus, CRT protein is important for Th-2 skewing and it binds to murine scavenger receptor A (Rzepecka et al., 2009). In arthropods, an endoparasitoid wasp, Cortesia rubercula, was demonstrated to inject a CRT-like protein to interfere with the host immune system to enhance survival of their progeny (Zhang et al., 2006). In the T. solium model, recombinant CRT conferred protective immunity in mice (Leon-Cabrera et al., 2012, Fonseca-Coronado et al., 2011). In DNA vaccine development, high CRT immunogenicity has been exploited to investigate the potential of CRT proteins as molecular adjuvants (Park et al., 2008).

In tick biology, functional analysis data on CRT is limited to being a validated tick saliva protein used as the biomarker for human tick bites (Sanders et al., 1998, Malouin et al., 2003, Alarcon-Chaidez et al., 2006). Sanders et al., (1998) observed that repeated Ixodes scapularis infestations in humans conferred an anamnestic antibody response further confirming that tick CRT is injected into the host during tick feeding. A limited number of tick CRT sequences that have been characterized show amino acid identity levels ranging from 77–98% among ticks (Xu et al., 2004, Kaewhom et al., 2008), and ~70% when compared to mammalian CRT sequences (Kaewhom et al., 2008). In the tick Amblyomma americanum (Aam), CRT was previously found in dopamine/theophylline-induced saliva (Jaworski et al., 1995). Given that AamCRT is present in saliva and injected into the host during tick feeding, our goal was to investigate the role(s) of AamCRT protein in tick feeding physiology against host defense mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Bioinformatics and phylogeny analyses

To determine if annotated calreticulin (CRT) functional amino acid motifs are conserved in ticks, we aligned A. americanum (AY395246) CRT sequence with human (NP_004334) and other previously functionally characterized parasite CRT proteins including, T. solium (AF340232, Fonseca-Coronado et al., 2011, Leon-Cabrera et al., 2012), N. americanus (AJ006790, Kasper et al., 2001), H. contortus (AAR99585, Naresha et 2009), T. cruzi (EKG06053, Ferreira et al., 2004a, 2004b, Ramírez et al., 2011), T. carrasi (ACV30040, Oladiran and Belosevic 2010), and H. polygyrus (CAL30086, Rzepecka et al., 2009) using ClustalW multiple sequence alignment provided in MacVector software (MacVector Inc., Cary, NC). The aligned sequences were screened for three CRT characteristic domains: (1) the globular N- domain, (2) the proline rich P-domain containing low capacity, high affinity Ca2+ binding site (Baksh and Michalak, 1991), a nuclear localization signal [NLS] (PPKKIKDPD motif) and three calreticulin P domain repeated motif [CPRM] KPEDWD (Fliegel et. al. 1989), and (3) the C- domain containing the high capacity low affinity Ca2+ binding site (Baksh and Michalak, 1991), glycosylation site, and 17–56 acidic amino acid sequence ending with an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal [ERRS] (K/H)(D/E)EL (Munro and Pelham, 1987, Fliegel et. al. 1989, Smith and Koch, 1989). Additionally, we also inspected tick CRT sequences for C1q (DEEKDKG, KDIRCKDD, GEWKPKQ, WEREYIDD, FNYKGKN, and IESKHKSDF) and Zn2+ (histidine amino acid residues) (Baksh et al., 1995, Stuart et al., 1996, Kovacs et al., 1998, Naresha et al., 2009) binding site amino acid motifs. To predict N- and O- linked glycosylation sites, AamCRT amino acid sequence (GenBank: AY395246) was scanned against the NetOGlyc 4.0 and NetNGlyc 1.0 CBS Servers (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/) to predict only two O-linked glycosylation sites.

To gain insight into the sequence relationships among tick CRT sequences, functionally annotated amino acid motifs found in AamCRT were compared to 34 other tick CRT sequences. Subsequently a phylogenetic tree of tick, human (NP_004334.1), and other hemoparasites CRT sequences tree out-rooted from Homo sapiens calnexin (GenBank: AAA21013.1) was constructed using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) 5.2.2 online software (http://www.megasoftware.net). CRT amino acid sequences were aligned using T-coffee in MacVector (MacVector Inc., Cary, NC) under default settings. To estimate bootstrap values, replications were set to 1000. Tick CRT sequences included in the analysis included A. americanum_AY395246, A. scutatum_AAR29938.1, A. rotundatum_AAR29937.1, A. geayi_AAR29935.1, A. cooperi_AAR29934.1, A. brasiliense_AAR29933.1, A. variegatum_DAA34570.1, A. triste_JAC35302.1, A. parvum_JAC26090.1, A. cajennense_JAC22751.1, A. maculatum_AEO34580.1, Dermacentor variabilis_AAR29944.1, D. occidentalis_AAR29943.1, D. andersoni_AAR29942.1, D. albipictus_AAR29941.1, Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum_AFQ98396.1, H. dromedarii_AEW43369.1, H. anatolicum excavatum_AAR29945.1, Rhipicephalus microplus_AAR29940, R. sanguineus_AAR29961.1, Haemaphysalis qinghaiensis_AAY42204.1, H. longicornis_AAQ18695.1, H. leporispalustris_AAR29947.1, Ixodes ricinus_AAR29958.1, I. persulcatus_AAR29957.1, I. pararicinus_AAR29956.1, I. pacificus_AAR29955.1, I. pavlovskyi_AAR29954.1, I. ovatus_AAR29953.1, I. nipponensis_AAR29952.1, I. muris_AAR29951.1, I. minor_AAR29950.1, I. jellisoni_AAR29949.1, I. affinis_AAR29948.1, and I. scapularis_XP_002402080.1). Hemoparasite CRT sequences included Heligmosomoides polygyrus_CAL30086.1, Trypanosoma cruzi_EKG06053.1, T. carassii_ACV30040.1, Haemonchus contortus_AAR99585.1, Necator americanus_AJ006790.1, and Taenia solium_AF340232.1.

Expression, affinity purification and characterization of recombinant (r) AamCRT

Expression of rAamCRT was done using pPICZαA yeast expression plasmid and the X-33 Pichia pastoris yeast host cell as previously described (Mulenga et. al., 2013). AamCRT coding domain was amplified from OligodT primed cDNA template of five day fed ticks using PCR primers (For: GAATTCGATCCCACCGTTTACTTCAAAG and Rev: GCGGCCGCCAGTTCCTCGTGCTTGTGGTC) with added enzyme sites (EcoRI/NotI, bold faced) designed based on NCBI sequence, GenBank: AY395246. The amplified AamCRT coding domain was sub-cloned into pPICZαA plasmid (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) using directional approach. After sequence confirmation, recombinant pPICZαA-AamCRT plasmid was used to transform X-33 P. pastoris as previously described (Mulenga et al., 2013). Transformed colonies were selected on Yeast Extract Peptone Dextrose Medium with Sorbitol (YPDS) agar plates with zeocin (100 μg/ml), and then selected for methanol utilization on Minimal Methanol (MM) agar plates, both incubated at 28°C. Positive transformants from PCR check were inoculated in Buffered Glycerol-complex Medium (BMGY) and grown overnight at 28°C with shaking (230–250 rpm). Subsequently the cells were used to inoculate Buffered Methanol-complex Medium (BMMY) to A600 of 1 after which protein expression was induced by adding methanol to 0.5% final concentration every 24 h for five days. Preliminary results showed, cumulative expression of rAamCRT appeared to peak by the third day. Thus, for large-scale expression and affinity purification of rAamCRT, we cultured yeast for up to three days. The pPICZαA plasmid secretes the recombinant protein into media, so the spent media was concentrated using ammonium sulfate precipitation and affinity purified as previously described (Mulenga et al., 2013). The affinity-purified rAamCRT was dialyzed against 10mM HEPES buffer pH 7.4, 1X PBS pH 7.4 or normal saline (0.9% NaCl in sterile molecular grade water) and stored in −80°C until used. Expression and affinity purification of rAamCRT was confirmed using standard SDS-PAGE with Coomassie blue staining or western blotting analysis using antibodies C-terminus hexa-histidine fusion tag (Life Technologies).

Western blotting analysis

In previous studies tick CRT was validated as a secreted tick saliva protein (Jaworski et al., 1995, Sanders et al., 1998, Malouin et al., 2003, Alarcon-Chaidez et al., 2006, Radulovic et. al., 2014). To validate if these data were consistent in this study, affinity purified rAamCRT was subjected to western blotting analysis using antibodies to 48 h A. americanum tick saliva proteins. Production of antibodies to 48h A. americanum tick saliva proteins used in this study was previously described (Chalaire et al., 2011). Preliminary analysis predicted N- and O-linked glycosylation sites in AamCRT. To confirm post-translational modification, affinity purified rAamCRT was treated with the protein deglycosylation mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), which removes O- and N-linked glycosylation sites. The sample treated and non-treated with deglycosylation mix were subjected to western blotting analysis using antibodies to the C-terminus hexa-histidine fusion tag (Life Technologies) on the pPICZAα vector.

Factor Xa and complement C1q protein binding assay

The potential for rAamCRT to bind blood-clotting factor Xa (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or the complement C1q protein (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) was done using ELISA approach as previously described (Suchitra and Joshi, 2005). Different amounts of rAamCRT, 3, 1.5, 0.75, 0.375, and 0 μM of rAamCRT diluted in 200 μL ELISA coating buffer (carbonate buffer, pH 9.5) was bound onto ELISA plates overnight at 4°C. Control wells received buffer only or ligand (C1q or factor Xa). Following coating, non-specific binding sites were blocked with 300 μL 5% blocking buffer (5% skim milk powder dissolved in 1X PBS w/Tween-20 pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequently 0.5 μg of the complement activation pathway C1q protein or factor Xa in 5% blocking buffer in 100 μL was added to each well, with the exception of the ligand (C1q or factor Xa) only control wells and incubated at 4°C overnight. Wells were washed with 300 μL of 1X PBS w/Tween-20 pH 7.4 for three times. Subsequently antibodies to human C1q or factor Xa proteins diluted at 1:1000 were added to the wells and the plates incubated for 2 h at room temperature (RT). Following incubation, wells were washed with three changes of 300 μL of 1X PBS w/Tween-20 pH 7.4. After washing, wells were incubated for 2 h at RT with 100 μL of goat anti-rabbit peroxidase conjugated IgG secondary antibody (EMD Millipore) diluted to a final 1:2000 concentration in 5% blocking buffer. Following incubation, wells were washed as above. Bound peroxidase activity, proxy for bound factor Xa or the C1q protein was detected by adding 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and stopped with 2 M sulfuric acid upon color change. The intensity of color development, which directly represented the amount of bound C1q or factor Xa was quantified at A450 using VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices LLC, Sunnyvale, CA).

Anti-platelet aggregation effects of rAamCRT

The platelet aggregation function assay was done using two methods. In the first method inhibition of platelet aggregation was determined using whole cattle blood (WCB). Cattle blood collected from the TAMU slaughterhouse was mixed with acid citrate dextrose (ACD) solution in 9:1 ratio to prevent clotting. Affinity purified 0.175 and 0.702 μM rAamCRT with adenosine phosphate (ADP) to 20 μM final concentration was pre-incubated for 15 min at 37°C. Following pre-incubation, platelet aggregation was induced by addition of ADP-rAamCRT to pre-warmed citrated WCB (500μL) diluted with normal saline (0.9% NaCl) in a 1:1 ratio. Platelet aggregation as a function of increased appendance in ohms (Ω) was then monitored and recorded using the Whole blood platelet aggregometer (Chrono-Log Corporation, Havertown, PA).

In the second method anti-platelet aggregation function was determined using platelet rich plasma (PRP) isolated from citrated WCB and analyzed on the VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices) as previously described (Horn et. al., 2000). To prepare PRP, fresh citrated WCB was centrifuged at 200 g for 20 min at 18°C. Subsequently the PRP (top layer) was transferred into a new tube and centrifuged at 800 g for 20 min at 18°C. The pellet containing the platelets were washed and diluted with Tyrode Buffer pH 7.4 (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 12 mM NaHCO3, 0.42 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% glucose, 0.25% BSA) until the A650 = 0.15. To determine anti-platelet aggregation function of AamCRT, 2.5 and 1.25 μM of rAamCRT was pre-incubated for 15 min at 37°C with 20 μM ADP in a 50 μl reaction. Adding 100 μl of pre-warmed PRP triggered platelet aggregation. Samples were detected every 20 s for 30 min at A650 using the VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices LLC).

Effects of rAamCRT on blood clotting

The effect of rAamCRT on the blood clotting system was determined using four approaches: (1) recalcification time (RCT), (2) activated partial thromboplastin time (APPT), (3) prothrombin time (PT), and (4) thrombin time (TT). The RCT assay, which measures the effect on the clotting system in its entirety, was done according to previously published methods (Liao et al., 2009, Gao et al., 2011) that were adopted in our lab (Mulenga et al., 2013) using two approaches. In the first approach, 20 μL of universal coagulation reference human plasma [UCRP] (Thermo Scientific) diluted to 90 μL with 10mM HEPES buffer pH 7.4 was pre-incubated with 3, 1.5, 0.75, and 0.375 μM of affinity purified rAamCRT for 10 min at 37°C. Following pre-incubation, adding 10 μl of 25 mM calcium chloride (CaCl2) the pre-warmed to 37°C triggered plasma clotting. The basis of the RCT assay is that resupplying of Ca2+ to citrated plasma triggers plasma clotting (Spillert and Lazaro, 1995). Given that mammalian CRT is a validated Ca2+ binding proteins (Baksh and Michalak, 1991), we wanted to test if pre-incubating rAamCRT with CaCl2 would sequester Ca2+ to affect plasma clotting. Thus in the second approach, similar amounts of rAamCRT that were used in the first approach up to 70 μL with 10mM HEPES buffer pH 7.4 were pre-incubated with 10 μL of 25 mM CaCl2 for 10 min at 37°C before adding to 20 μL plasma pre-warmed to 37°C. Plasma clotting time was monitored at A650nm at 20 s intervals over 20 min using VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices LLC) set to 37°C. The interpretation of data was that formation and firming of the clot was directly proportional increase in OD.

In the APPT assay, which measures the effect on the intrinsic blood clotting activation pathway, various amounts of rAamCRT were pre-incubated for 5 min at 37°C with 30 μL UCRP diluted up to 100 μL with 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4. Subsequently, 100 μL of the APPT reagent (Thermo Scientific) was added to plasma and incubated at 37°C for an additional 5 min to activate the reaction. Addition of 100 μL 25 mM CaCl2 to the reaction triggered clotting. Alternatively we repeated this experiment by pre-incubating rAamCRT with 100 μL 25 mM CaCl2 for 5 min at 37°C before adding to activated plasma to trigger clotting

In the PT assay, which measures the effect on the extrinsic blood clotting activation pathway, various amounts of rAamCRT indicated above were pre-incubated at 37°C for 5 min with 25 μL UCRP diluted up to 100 μL with 10 mM HEPES buffer. Adding 200 μL of the pre-warmed PT reagent (Thermo Scientific) and CaCl2 mixture triggered plasma clotting.

In the TT assay, to measure effects on the common blood clotting activation pathway, various amounts of rAamCRT indicated above used in the two assays above were pre-incubated at 37°C for 5 min with 25 μL of the TT reagent (Thermo Scientific) and CaCl2 mixture diluted up to 100 μL with 10 mM HEPES buffer. Adding 200 μL of pre-warmed UCRP started the clotting reaction. For APTT, PT and TT assays, plasma-clotting time was determined using the KC1 DELTA coagulmeter (Trinity Biotech, NJ, Parsippany). All assays were done in duplicates and results presented as mean (M).

Anti-complement function

To determine the effect of rAamCRT on the complement activation pathway two methods were used. In the first method the MicroVue CH50 ELISA kit (Quidel Corp., San Diego, CA) was used. Various amounts, 5.6, 2.8, 1.4, 0.7, and 0.35 μM of rAamCRT was pre-incubated at 37°C for 10 min with 14 μL serum. The serum-rAamCRT was then incubated with 86 μL of the complement activator solution for 1 h at 37°C. The end point of CH50 ELISA kit is that it quantifies the amount of terminal complement complexes (TCC) that are formed when the complement system is activated. To quantify the amount of formed TCC, the reaction mix was diluted 1:200. One hundred microliter of the diluted sample was applied to wells that were pre-coated with human antibodies to TCC and then incubated for 1 h at RT. Following appropriate washing, wells were incubated with 100 μL HRP-conjugated goat antibodies to TCC and incubated for 1 h at RT. Subsequently after appropriate washes, incubation with 100 μL of the chromogenic HRP substrate provided with the kit continued at RT for 15 min when the reaction was stopped with 100 μL stop solution (2 M sulfuric acid). The intensity of color change, which directly represented the amount of formed TCC was quantified by reading A450 using the VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices LLC).

In the second method we used bacteria to activate the classical complement cascade in serum. The expectation for this assay was that upon inoculation of serum with bacteria, the complement cascade would be triggered and the bacteria would be lysed. On the flip side inoculation of serum depleted of C1q with bacteria, the complement cascade would not be triggered and the bacteria would not be lysed. The idea was supplementing the C1q depleted serum with exogenous C1q would restore the complement cascade and cause bacteria lysis similar to normal serum.

We used two Escherichia coli K-12 strains, DH5α and BL21 (Life Technologies) transformed with green fluorescent protein (GFP) vector pGlo that conferred ampicillin resistance (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Both DH5α and BL21 bacteria cells were grown at 37°C with shaking overnight in 7 ml of S.O.B broth with ampicillin (75 μg/mL). Subsequently, 1 mL of bacteria culture was centrifuged at 5000 g for 10 min and the pellet re-suspended in 1 mL of 1X PBS pH 7.4. A further 10,000 fold dilution of bacteria cells in 1X PBS pH 7.4 was used for the assay. In triplicates various amounts, 4, 2, and 1 μM, of rAamCRT in 47 μL were pre-incubated with 3 μL of C1q (0.2 μM) at 37°C for 10 min. Subsequently for a final reaction volume of 100 μL, 30 μL of diluted bacteria, an empirically determined 20 μL of C1q depleted human serum (Quidel Corp.), and 1X PBS was added to the rAamCRT-C1q reaction mixture. To trigger the complement cascade the reaction mix was incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Following incubation the 100 μL reaction mixture was plated on LB agar plates containing ampicillin (75 μg/mL) and arabinose (6 mg/mL) (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) and incubated at 37°C overnight. Arabinose induced expression of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). GFP expressing bacteria colonies were visualized under UV light source to count colonies. Normal serum (positive control: no bacteria growth = activated complement cascade), C1q depleted serum (negative control: bacteria growth = no complement cascade activation), bacteria only in 1X PBS (bacteria growth expected) were included under same conditions as controls.

Statistical analysis

To determine statistical significance between treatments in C1q or Factor Xa binding, anti-haemostasis, and anti-complement function assays were subjected to non-parametric student t-test set to 95% confidence interval. Statistical software packages in PRISM version 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) were used.

RESULTS

Annotated functional CRT amino acid motifs conserved in ticks

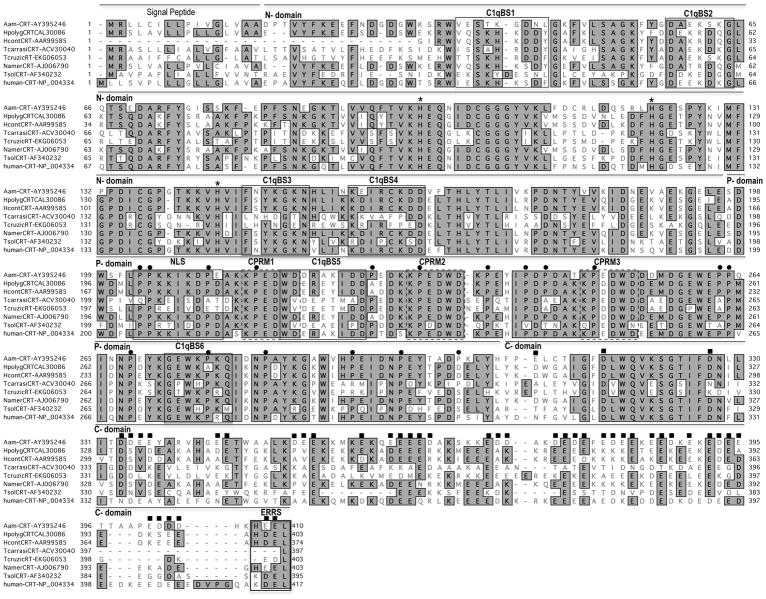

Amino acid identity levels among tick CRT sequences, and between tick and human CRT sequences were reported (Kaewhom et al., 2008). In this study, the analysis focused on the possibility that annotated CRT functional amino acid motifs and/or amino acid residues involved in ligand binding were conserved in ticks. Inspection of the multiple sequence alignment reveal that typical CRT features: the globular N-, the proline rich P- (Baksh and Michalak, 1991), and the C- domains are conserved in AamCRT at positions 20–195, 196–305, and 313–410 respectively (Fig. 1). Within the “N” domain, four of the five-histidine [H, marked with asterisks sign (*)] amino residues that in human CRT were verified as Zn2+ binding sites (Baksh et al., 1995) are conserved in AamCRT. In the P domain 18 proline (P) amino acid residues are noted with filled circles (●) on top, while the nuclear localization signal [NLS] (PPKKIKDPD motif) and three calreticulin P domain repeated motif [CPRM] KPEDWD (Fliegel et. al. 1989) are boxed with broken lines and noted. In the C- domain, AamCRT contains 43 acidic amino acid residues (Aspartic (D)/Glutamic (E) acid, marked with filled square (■) on top, an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal, [ERRS] and two possible O-linked glycosylation sites at positions 396 and 397 consistent with a typical CRT protein (Fig. 1). The presence of the NLS and ERRS motifs supports the presence of AamCRT both in the nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum consistent with mammals (Opas et. al., 1991). The six functionally annotated C1q binding amino acid motifs (boxed with solid lines and marked as C1qBS1-6, (Fig. 1) are conserved to various levels in AamCRT.

Figure 1. Multiple sequence alignment of Amblyomma americanum (Aam) CRT and amino acid sequences of functionally characterized CRT in human and other parasites.

Downloaded CRT amino acid (AA) sequences of A. americanum (GenBank:AY395246), human (NP_004334) and other parasite CRT, T. cruzi (EKG06053), T. carrasi (ACV30040), T. solium (AF340232), H. contortus (AAR99585), N. americanus (AJ006790) and H. polygyrus (CAL30086) were subjected to multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW in MacVector. The aligned sequences were visually inspected for, globular N- domain, the proline rich P-domain and the C- domain noted in figure 1. The P- domain contains the nuclear localization signal [NLS] (solid box and noted) and three calreticulin P domain repeated motifs [CPRM1-3] (dotted box and noted). The C-domain contains the endoplasmic reticulum retention signal [ERRS, boxed and noted]. The six C1q binding site AA motifs [C1qBS1-6] are noted and boxed with solid lines. CRT conserved histidine (H) AA residues are marked with an asterisks (*) sign above, the proline (P) AA residues are noted with filled circles (●) above, and the characteristic acidic AA residues in AamCRT c-domain are marked with filled squares (■).

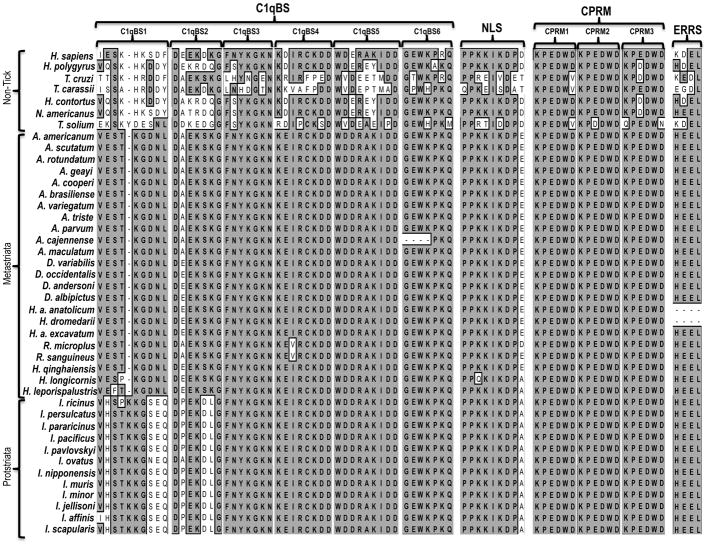

To gain insight on diversity among ticks and relationship to human and other parasites, we extracted CRT motifs in figure 1 and from other tick CRT amino acid sequences deposited in GenBank and then compared them as summarized in figure 2. Based on multiple sequence alignment, the CRT motifs in ticks are closer to humans than to other parasites (Fig. 2). Of the six C1q binding sites, C1qBS1 (human reference motif, DEEKDKG) is the least conserved between ticks and humans or other parasite CRT sequences. Additionally we noticed that C1qBS1 of other parasite CRT sequences in figure 1 show 66–100% amino acid identity to human CRT (Fig. 2). Notably the C1qBS1 and 2 are the least conserved between metastriata and prostriata tick CRT. Tick C1qBS2-6 (human reference motifs, KDIRCKDD, GEWKPKQ, WEREYIDD, FNYKGKN, and IESKHKSDF) sites show high conservation ranging from 71–100% to human and 33–100% to parasite CRT motifs sequences respectively. The other three amino acid motifs, “NLS”, “CPRM” and “ERRS” motifs show high conservation in all organisms overall (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Multiple sequence alignment of functionally annotated amino acid motifs of Amblyomma americanum and other parasite CRT proteins.

Thirty four tick CRT amino acid sequences from NCBI consisting of Metastriata: A. americanum (GenBank:AY395246), A. scutatum_AAR29938.1, A. rotundatum_AAR29937.1, A. geayi_AAR29935.1, A. cooperi_AAR29934.1, A. brasiliense_AAR29933.1, A. variegatum_DAA34570.1, A. triste_JAC35302.1, A. parvum_JAC26090.1, A. cajennense_JAC22751.1, A. maculatum_AEO34580.1), Rhipicephalus (R. microplus_AAR29940, R. sanguineus_AAR29961.1), Hyalomma (H. anatolicum anatolicum_AFQ98396.1, H. dromedarii_AEW43369.1, H. anatolicum excavatum_AAR29945.1), Dermacentor (D. variabilis_AAR29944.1, D. occidentalis_AAR29943.1, D. andersoni_AAR29942.1, D. albipictus_AAR29941.1), Haemaphysalis (H. qinghaiensis_AAY42204.1, H. longicornis_AAQ18695.1, H. leporispalustris_AAR29947.1), and Prostriata ticks: Ixodes (I. ricinus_AAR29958.1, I. persulcatus_AAR29957.1, I. pararicinus_AAR29956.1, I. pacificus_AAR29955.1, I. pavlovskyi_AAR29954.1, I. ovatus_AAR29953.1, I. nipponensis_AAR29952.1, I. muris_AAR29951.1, I. minor_AAR29950.1, I. jellisoni_AAR29949.1, I. affinis_AAR29948.1, I. scapularis_XP_002402080.1), six other parasites: T. cruzi (EKG06053), T. carrasi (ACV30040), T. solium (AF340232), H. contortus (AAR99585), N. americanus (AJ006790) and H. polygyrus (CAL30086) and human: H. sapiens (NP_004334) CRTs, were subjected to multiple sequence alignment using T-coffee in MacVector software. The aligned sequences were visually inspected for presence of the six C1q binding site amino acid motifs (C1qBS1-6), the nuclear localization signal (NLS), three calreticulin P domain repeated motifs (CPRM1-3), and the endoplasmic reticulum retention signal [ERRS].

AamCRT amino acid sequences are highly conserved across tick species

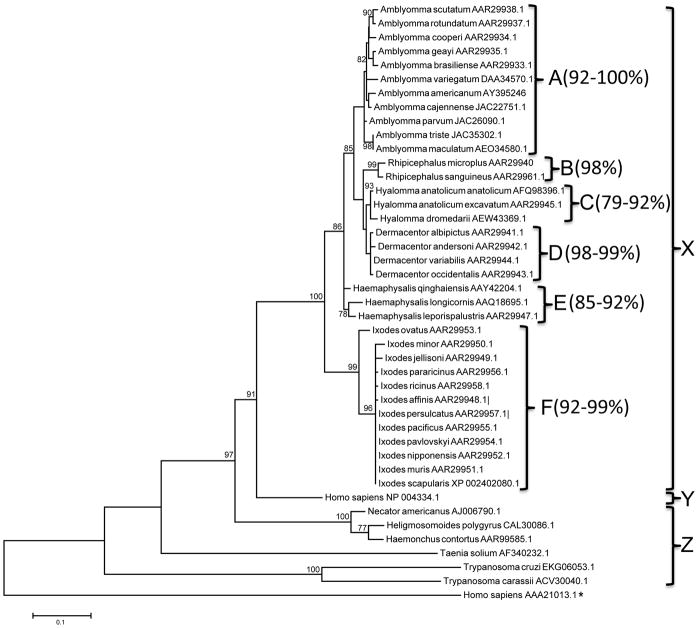

Figure 3 summarizes the phylogeny relationship of AamCRT proteins with other ticks, and functionally characterized human and hemoparasite CRTs retrieved from GenBank. As shown in figure 3, CRTs segregated into three clusters labeled as X, Y, and Z, supported by a respective 100, 91 and 97% bootstrap values. Tick CRTs in cluster X further segregated into clusters A-F showing high amino acid identity levels within genera. Pairwise alignment of tick amino acid sequences reveal that within clusters: A for Amblyomma, B for Rhipicephalus, C for Hyalomma, D for Dermacentor, E for Haemaphysalis, and F for Ixodes show a respective range of 92–100, 98, 79–92, 98–99, 85–92, and 92–99% identities (Fig. 3). Additionally, AamCRT segregated with other Amblyomma tick CRTs showing 92–96% amino acid identity (not shown). Furthermore AamCRT showed 89–90% amino acid identity to cluster B, 75–92% to C, 91–92% to D, 83–91% to E, and 77–78% to F (not shown). However when compared to remaining sequences amino acid identity levels decreased to 68% in cluster Y and 45–62% in cluster Z (not shown). It is interesting to note that AamCRT amino acid sequence is 69% identical to human, and 45–60% to parasite CRT proteins (not shown)

Figure 3. Phylogeny analysis of Amblyomma americanum, other parasites, and human CRT amino acid sequences.

A guide phylogeny tree of AamCRT protein sequence with other tick, parasite, and human CRT sequences was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method with bootstrap replicates set to 1000. Number at each node represents bootstrap values that signify the level of confidence in the branch. Three main clusters: X (tick CRTs), Y (Homo sapien [GenBank:NP004334.1]), and Z other parasite and an outgroup of human calnexin (GenBank:AAA2103.1) noted with asterisk (*). The overall amino acid identity percentage levels are noted for cluster A–F.

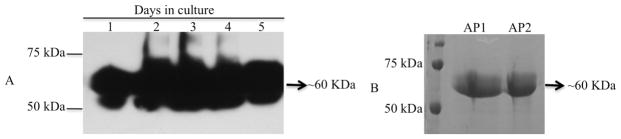

Expression of recombinant (r) AamCRT in Pichia pastoris

In order to characterize the role(s) of tick CRT at tick-feeding site, we thought to express recombinant (r) A. americanum tick CRT in Pichia pastoris (Fig. 4). In figure 4A, we show that rAamCRT was robustly expressed through out the all five days of culture. In figure 4B, we verified the purity of the affinity-purified rAamCRT using Coommassie blue staining. The pPICZα vector adds either ~3.5 kDa if the vector’s α-factor signal peptide (SP) is cleaved off from the recombinant protein, or ~11.8 kDa if the SP is not cleaved off. On this basis the expected molecular weight of rAamCRT was ~50 kDa (46 kDa mature tick CRT plus 3.5 kDa vector fusion) if SP is processed out, or ~58/60 kDa (expected ~46 kDa mature AamCRT plus 11.8 kDa fusion tag from vector) if the SP is not cleaved off as observed in figure 4. The increased MW of rAamCRT can also result from post-translational modifications. However, when subjected to N- or O-linked deglycosylation treatment, no molecular weight shift was observed (not shown).

Figure 4. Expression and affinity purification of recombinant Amblyomma americanum CRT in Pichia pastoris.

The coding domain for mature AamCRT amplified as described in materials and methods was sub-cloned into pPICZαA yeast expression plasmid using routine directional approach. Following confirmation of sequence, recombinant pPICZαA-AamCRT was expressed and affinity purified as described in materials and methods. Expression and affinity purification of rAamCRT was respectively confirmed using routine western blotting analysis using antibodies C-terminus hexa-histidine tag and detected with chemiluminescent substrates (A) and SDS-PAGE with Coommassie blue staining (B). Lanes 1–5 in “4A” = daily expression levels of rAamCRT. In “4B”, AP1 and AP2 = affinity purified fractions 1 and 2.

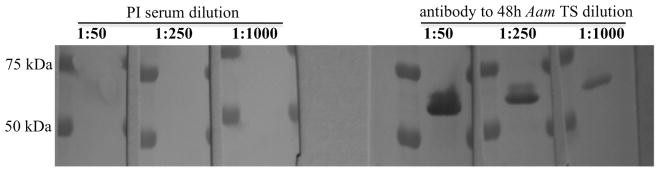

In previous studies tick CRT was demonstrated to be among tick saliva proteins that are injected into the host during tick feeding (Jaworski et al., 1995, Sanders et al., 1998, Malouin et al., 2003, Alarcon-Chaidez et al., 2006, Radulovic et. al., 2014). In this study experiments summarized in figure 5 validate these reports in that rAamCRT specifically reacted with antibodies to 48 h fed A. americanum tick saliva proteins.

Figure 5. Western blotting analysis of rAamCRT using antibodies to 48h Amblyomma americanum tick saliva proteins.

Affinity purified rAamCRT loaded into triplicate lanes was electrophoresed on a 10% Tris-glycine acrylamide gel and electroblotted onto PVDF membranes using routine methods. The three lanes were cut into individual strips, which were exposed to three different concentrations (noted in Fig. 5) of pre-immune and antibodies to 48h A. americanum tick saliva proteins as indicated.

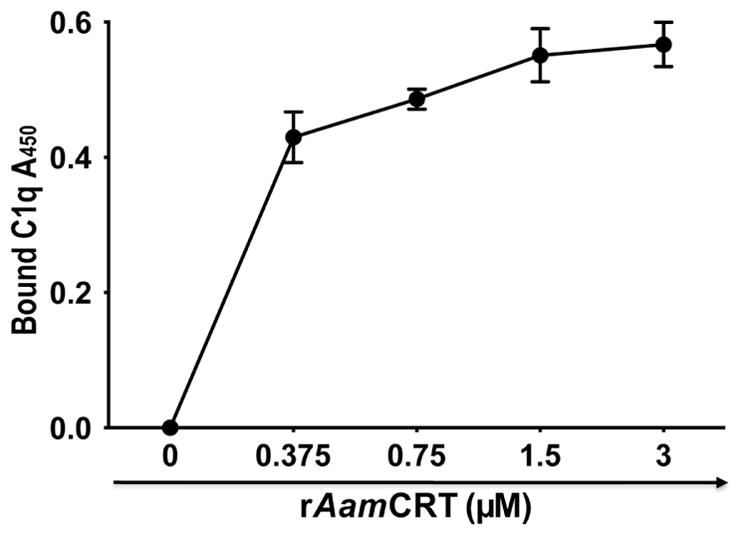

rAamCRT binds C1q protein, not factor Xa and does not inhibit classical complement cascade

Published studies demonstrated that parasite CRT proteins could bind both C1q and factor Xa (Suchitra and Joshi, 2005). To investigate if this function was conserved in ticks, we subjected rAamCRT to C1q (Fig. 6) and factor Xa (not shown) binding assays. While rAamCRT bound the C1q protein in dose response manner (Fig. 6), it did not bind to factor Xa (not shown). Given the observed rAamCRT binding of C1q, we thought to investigate if this translated to inhibition of the classical complement cascade. Data from two approaches showed that rAamCRT binding of C1q, an important component of the classical complement cascade, did not inhibit this cascade (data not shown). In the first analysis using the MicroVue CH50 ELISA kit we expected that higher concentrations of rAamCRT would lead to reduced production of terminal complement complexes (TCC). To our surprise we observed that increased amounts rAamCRT enhanced production of TCC instead (not shown). In the second approach, we used C1q depleted serum in which exogenous C1q restored the complement cascade and bacteria was lysed. Our expectation was that pre-incubating C1q with rAamCRT prior to adding to C1q depleted serum would sequester C1q, the complement cascade was not activated, and bacteria were not lysed. However, we observed no difference with or without rAamCRT (not shown).

Figure 6. Recombinant AamCRT binding of the C1q protein.

Different amounts of rAamCRT (indicated) were diluted in 200μL ELISA coating buffer (carbonate buffer, pH 9.5) and bound onto ELISA plates overnight at 4°C. Control wells received buffer only or ligand (C1q or factor Xa). Following coating, wells were blocked as described in materials and methods and subsequently incubated with 100μL (0.5μg) of C1q protein with the exception of the ligand (C1q) only control wells, overnight at 4°C. Following appropriate washing, wells were incubated with antibodies to human C1q for 2h at room temperature (RT). Following incubation and appropriate washing, plates were incubated for 2h at RT with 100μL of anti-rabbit peroxidase conjugated IgG. Following appropriate washing bound peroxidase activity, proxy for bound C1q protein was detected by adding OPD substrate as described and level of bound C1q quantified at A450 using the VersaMax mircoplate reader. Shown in the figure is bound C1q OD with background removed.

rAamCRT has no apparent anti-hemostatic function

To investigate if tick CRT plays a role(s) in tick modulation of host hemostasis, we subjected rAamCRT to platelet aggregation and blood clotting function assays. Consistent with observations that rAamCRT did not bind factor Xa, pre-incubating rAamCRT with plasma did not affect clotting time (not shown). Likewise pre-incubating rAamCRT with CaCl2 did not affect plasma clotting. In blood clotting assays we used citrated whole blood or UCRP in which sodium citrate sequestered Ca2+ ions, the fourth co-factor of the blood clotting system. Thus resupplying Ca2+ ions to citrated blood triggers plasma clotting. Our expectation was that since CRT was a validated Ca2+ ion binding protein, pre-incubating rAamCRT with CaCl2 would sequester Ca2+ ions and prevent plasma clotting. However this was not the case in this study (not shown). Additionally in the platelet aggregation function assay, we did not see any inhibitory effects using two sources: (1) citrated whole blood or (2) platelet rich plasma (not shown).

Discussion

This study describes an update on bioinformatics analysis and characterization of role(s) of tick CRT in tick feeding physiology. Previous studies have reported high amino acid identity levels of more than 85% among ticks, and ~60–70% between tick and vertebrate CRT sequences (Kaewhom et al., 2008). Data in this study builds on previous reports and show that tick CRT proteins show high amino acid identity to human than to parasite CRT proteins. Consistent with reported studies (Jaworski et al., 1995, Sanders et al., 1998, Malouin et al., 2003, Alarcon-Chaidez et al., 2006, Radulovic et al., 2014), Pichia pastoris-expressed rAamCRT used in this study specifically reacted with antibodies to A. americanum tick saliva proteins confirming that AamCRT is injected into the host during tick feeding. Additionally in an ongoing study, we have found a calreticulin in I. scapularis tick saliva that shows 78% amino acid identity to AamCRT (unpublished) and have also verified the presence of AamCRT in A. americanum tick saliva proteomes (unpublished). Likewise a recent study by Tirloni et al., (2014) found a calreticulin that shows 89% amino acid identity to AamCRT in saliva of R. microplus.

The observed high conservation of annotated functional motifs between ticks and functionally characterized CRT proteins in human and other parasites are suggestive of conservation of function. However data in this study show that this is not the case. Although rAamCRT bound C1q, the first protein in the classical complement activation pathway (Nayak et al., 2010), the progression of the pathway was not affected. This is in contrast to other parasite CRT (Ferreira et al., 2004a, 2004b, Naresha et 2009, Schroeder et al., 2009, Ramírez et al., 2011, Kasper et al., 2001), which bound C1q and stopped the classical complement pathway. Data in this study is not unique. In a personal communication with C.A. Ferreira (Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil), R. microplus CRT that shows 89% amino acid identity to AamCRT characterized in this study also bound C1q but did not inhibit activation of the classical complement pathway. The lack of effect on the classical complement system despite rAamCRT binding of the C1q protein is intriguing and may be explained by three plausible explanations. The first is that one of the six functionally validated C1q binding amino acid motifs (Stuart et al., 1996, Kovacs et al., 1998, Naresha et al., 2009) is poorly conserved in AamCRT as revealed by sequence analysis in this study. However, whether or not this amino acid motif is critical for sequestering C1q and thus interfering with the classical complement activation pathway has not been determined. The classical complement system is initiated by binding of C1q, C1r and C1s on pathogen surfaces (Nayak et al., 2010). Thus, the second explanation could be that while rAamCRT bound to C1q it did not sequester it from the interaction with C1r and C1s, and complement system was activated. It is also interesting to note that in the terminal complement complex (TCC) production assay, we observed more TCC formed with increased amount or rAamCRT. From this perspective, there is a possibility that tick CRT may enhance the classical complement pathway and contribute to tick feeding success by keeping the tick-feeding site sterile. It is most likely that in addition to preventing blood from clotting, the tick has to keep the feeding-site free of infection from contaminating microbial organisms that may arise from the skin. Alternatively, a remotely possible explanation could be that in vivo tick CRT acts in concert with other proteins to inhibit the complement activation system. In this way, tick CRT acts as scaffold for binding C1q, which is subsequently degraded by yet identified protein inhibitors of the complement activation system. Given that tick CRT is at the tick-feeding site, it is conceivable that tick CRT is involved in other functions that contribute to the outcome of tick and host interactions. The nematode H. polygyrus CRT protein that show 64% amino acid identity to AamCRT was linked to skewing of Th-2 response in infested rodents (Rzepecka et al., 2009). Several studies have shown that yet to be identified tick saliva protein factor(s) skews a Th-2 host response to tick feeding (Schoeler et al., 1999, Castagnolli et al., 2008, Menten-Dedoyart et al., 2008). It would be interesting to determine if tick AamCRT is responsible for the observed skewing of a Th-2 response in tick infestations of animals.

Another observation in this study is that rAamCRT neither bound factor Xa nor affected plasma-clotting time. This was particularly interesting given that recombinant H. contortus CRT, which in this study showed 64% amino acid identity to AamCRT bound both factor Xa and delayed plasma clotting (Suchitra and Joshi, 2005, Suchitra et al., 2008). There is also a possibility that A. americanum ticks may not need CRT to bind factor Xa because they have alternatives. Previous studies have reported tick salivary gland anticoagulants that target multiple hemostatic factors including factor Xa (Wang et al., 1996, Mans et al., 2002, Kovář, 2004, Waxman et al., 1990, Limo et al., 1991, Ibrahim et al., 2001, Francischetti et al., 2002). In both of the plasma clotting assays (APPT and RCT) used in this study plasma clotting was triggered by addition of CaCl2. Given that CRT is a validated Ca2+ binding protein (Ostwald and MacLennan, 1974, Gelebart et al., 2005), we expected a delay in plasma clotting time when rAamCRT was pre-incubated with CaCl2 before adding to plasma. However we did not observe any effects in plasma clotting time. This finding may be explained by two possibilities: (1) either AamCRT is not a functional Ca2+ binding protein or (2) that it does bind but it does not necessary sequester Ca2+ ions from the reaction. To resolve this question, further experiments are needed to determine if rAamCRT can bind to radio-labeled Ca2+ using blot overlay assays (Naik et al., 1997, Naaby-Hansen et al., 2010).

Given the high amino acid sequence identity between ticks and vertebrate CRT as reported in this study and others (Kaewhom et al., 2008), it is interesting that in these studies a strong host antibody response to tick and other parasite CRTs was observed. The expectation would be that an antigen that is highly homologous to the vertebrate protein might be a poor antigen in that it might be recognized as self and thus not stimulate a robust antibody response as is observed with tick and other parasite CRT proteins.. It is also notable that human CRT acts as an auto-antigen in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, complete congenital heart block, and coeliac disease (Holoshitz et al., 2010, Ling et al., 2010). In mice, cross-reactivity of antibodies to T. cruzi CRT with the mouse CRT protein was advanced as a possible explanation for the observed chagasic autoimmunity (Teixeira et al., 2011, 2012, Machado et al., 2012). The possibility of antibodies to tick CRT cross-reacting with host CRT has the potential to provide ticks with means to evade host defense mechanisms to tick feeding activity. Human CRT was demonstrated to enhance healing of difficult diabetic wounds (Nanney et al., 2008). To successfully feed, ticks have to stop the wound healing response by the host, which would otherwise lead to blood clotting and thereby denying ticks a full blood meal. Thus, the potential for antibodies to tick CRT cross-reacting with host CRT raises the possibility for tick antibodies to bind host CRT and delay wound healing, and other yet unknown anti-tick feeding functions of host CRT.

In conclusion, data in this study demonstrates that AamCRT is not apparently involved in mediating tick anti-hemostasis and anti-complement functions. The high amino acid conservation among tick CRT proteins suggests the yet to be fully resolved functions of this protein in ticks are conserved in all tick species. Given that AamCRT is injected into the host, it is most likely that this protein is associated with regulating important tick functions, and thus follow up experiments are warranted to understand role(s) of tick CRT in tick feeding physiology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases National Institutes of Health (NIAID/NIH) grant (AI081093) to AM. AI was a visiting Ph.D student from Brazil supported by a scholarship from CNPq – Brazil.

References

- Aguillón JC, Ferreira L, Pérez C, Colombo A, Molina MC, Wallace A, Solari A, Carvallo P, Galindo M, Galanti N, Orn A, Billetta R, Ferreira A. Tc45, a dimorphic Trypanosoma cruzi immunogen with variable chromosomal localization, is calreticulin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:306–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon-Chaidez F, Ryan R, Wikel S, Dardick K, Lawler C, Foppa IM, Tomas P, Cushman A, Hsieh A, Spielman A, Bouchard KR, Dias F, Aslanzadeh J, Krause PJ. Confirmation of tick bite by detection of antibody to Ixodes calreticulin salivary protein. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:1217–1222. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00201-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An YQ, Lin RM, Wang FT, Feng J, Xu YF, Xu SC. Molecular cloning of a new wheat calreticulin gene TaCRT1 and expression analysis in plant defense responses and abiotic stress resistance. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10:3576–3585. doi: 10.4238/2011.November.10.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai ZY, Zhu ZY, Wang CM, Xia JH, He XP, Yue GH. Cloning and characterization of the calreticulin gene in Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) Animal. 2012;6:887–893. doi: 10.1017/S1751731111002199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baksh S, Michalak M. Expression of calreticulin in Escherichia coli and identification of its Ca2+ binding domains. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21458–21465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baksh S, Spamer C, Heilmann C, Michalak M. Identification of the Zn2+ binding region in calreticulin. FEBS Lett. 1995;376:53–57. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezón C, Cabrera G, Paredes R, Ferreira A, Galanti N. Echinococcus granulosus calreticulin: molecular characterization and hydatid cyst localization. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:1431–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnolli KC, Ferreira BR, Franzin AM, de Castro MB, Szabó MP. Effect of Amblyomma cajennense ticks on the immune response of BALB/c mice and horses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1149:230–234. doi: 10.1196/annals.1428.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalaire KC, Kim TK, Garcia-Rodriguez H, Mulenga A. Amblyomma americanum (L.) (Acari: Ixodidae) tick salivary gland serine protease inhibitor (serpin) 6 is secreted into tick saliva during tick feeding. J Exp Biol. 2011;214(Pt 4):665–673. doi: 10.1242/jeb.052076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durden LA, Luckhart S, Mullen GR, Smith S. Tick infestations of white-tailed deer in Alabama. J Wildl Dis. 1991;27:606–614. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-27.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira CA, Da Silva Vaz I, da Silva SS, Haag KL, Valenzuela JG, Masuda A. Cloning and partial characterization of a Boophilus microplus (Acari: Ixodidae) calreticulin. Exp Parasitol. 2002;101:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4894(02)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira V, Molina MC, Valck C, Rojas A, Aguilar L, Ramírez G, Schwaeble W, Ferreira A. Role of calreticulin from parasites in its interaction with vertebrate hosts. Mol Immunol. 2004a;40:1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira V, Valck C, Sánchez G, Gingras A, Tzima S, Molina MC, Sim R, Schwaeble W, Ferreira A. The classical activation pathway of the human complement system is specifically inhibited by calreticulin from Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 2004b;172:3042–3050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegel L, Burns K, MacLennan DH, Reithmeier RA, Michalak M. Molecular cloning of the high affinity calcium-binding protein (calreticulin) of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:21522–21528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Coronado S, Ruiz-Tovar K, Pérez-Tapia M, Mendlovic F, Flisser A. Taenia solium: immune response against oral or systemic immunization with purified recombinant calreticulin in mice. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti IM, Valenzuela JG, Andersen JF, Mather TN, Ribeiro JM. Ixolaris, a novel recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) from the salivary gland of the tick, Ixodes scapularis: identification of factor X and factor Xa as scaffolds for the inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor complex. Blood. 2002;99:3602–3612. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Luo J, Fan R, Fingerle V, Guan G, Liu Z, Li Y, Zhao H, Ma M, Liu J, Liu A, Ren Q, Dang Z, Sugimoto C, Yin H. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA clone encoding calreticulin from Haemaphysalis qinghaiensis (Acari: Ixodidae) Parasitol Res. 2008;102:737–746. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0826-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Shi L, Zhou Y, Cao J, Zhang H, Zhou J. Characterization of the anticoagulant protein Rhipilin-1 from the Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides tick. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelebart P, Opas M, Michalak M. Calreticulin, a Ca2+-binding chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LI, Eggleton P, Sweetwyne MT, Van Duyn LB, Greives MR, Naylor SM, Michalak M, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Calreticulin: non-endoplasmic reticulum functions in physiology and disease. FASEB J. 2010;24:665–683. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-145482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LI, Rahman M, Blechman KM, Greives MR, Churgin S, Michaels J, Callaghan MJ, Cardwell NL, Pollins AC, Michalak M, Siebert JW, Levine JP, Gurtner GC, Nanney LB, Galiano RD, Cadacio CL. Overview of the role for calreticulin in the enhancement of wound healing through multiple biological effects. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2006;11:57–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsymp.5650011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González E, Rico G, Mendoza G, Ramos F, García G, Morán P, Valadez A, Melendro EI, Ximénez C. Calreticulin-like molecule in trophozoites of Entamoeba histolytica HM1:IMSS (Swissprot: accession P83003) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:636–639. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holoshitz J, De Almeida DE, Ling S. A role for calreticulin in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1209:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn F, dos Santos PC, Termignoni C. Boophilus microplus anticoagulant protein: an antithrombin inhibitor isolated from the cattle tick saliva. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;384:68–73. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins MC, Gibbs J, Moloney NA. Cloning of a Schistosoma japonicum gene encoding an antigen with homology to calreticulin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;71:81–87. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MA, Ghazy AH, Maharem TM, Khalil MI. Factor Xa (FXa) inhibitor from the nymphs of the camel tick Hyalomma dromedarii. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;130:501–512. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski DC, Simmen FA, Lamoreaux W, Coons LB, Muller MT, Needham GR. A secreted calreticulin protein in ixodid tick (Amblyomma americanum) saliva. J Insect Physiol. 1995;41:369–375. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski DC, Higgins JA, Radulovic S, Vaughan JA, Azad AF. Presence of calreticulin in vector fleas (Siphonaptera) J Med Entomol. 1996;33:482–489. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/33.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia XY, Xu CY, Jing RL, Li RZ, Mao XG, Wang JP, Chang XP. Molecular cloning and characterization of wheat calreticulin (CRT) gene involved in drought-stressed responses. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:739–751. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Hong Z, Su W, Li J. A plant-specific calreticulin is a key retention factor for a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(32):13612–13617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906144106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaewhom P, Stich RW, Needham GR, Jittapalapong S. Molecular analysis of calreticulin expressed in salivary glands of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus indigenous to Thailand. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1149:1153–1157. doi: 10.1196/annals.1428.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kales S, Fujiki K, Dixon B. Molecular cloning and characterization of calreticulin from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Immunogenetics. 2004;55:717–723. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper G, Brown A, Eberl M, Vallar L, Kieffer N, Berry C, Girdwood K, Eggleton P, Quinnell R, Pritchard DI. A calreticulin-like molecule from the human hookworm Necator americanus interacts with C1q and the cytoplasmic signalling domains of some integrins. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:141–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollars TM, Jr, Durden LA, Masters EJ, Oliver JH., Jr Some factors affecting infestation of white-tailed deer by blacklegged ticks and winter ticks (Acari:Ixodidae) in southeastern Missouri. J Med Entomol. 1997;34:372–375. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs H, Campbell ID, Strong P, Johnson S, Ward FJ, Reid KB, Eggleton P. Evidence that C1q binds specifically to CH2-like immunoglobulin gamma motifs present in the autoantigen calreticulin and interferes with complement activation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17865–17874. doi: 10.1021/bi973197p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar L. Tick saliva in anti-tick immunity and pathogen transmission. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2004;49:327–336. doi: 10.1007/BF02931051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon-Cabrera S, Cruz-Rivera M, Mendlovic F, Romero-Valdovinos M, Vaughan G, Salazar AM, Avila G, Flisser A. Immunological mechanisms involved in the protection against intestinal taeniosis elicited by oral immunization with Taenia solium calreticulin. Exp Parasitol. 2012;132:334–430. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhuo K, Luo M, Sun L, Liao J. Molecular cloning and characterization of a calreticulin cDNA from the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Exp Parasitol. 2011;128:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao M, Zhou J, Gong H, Boldbaatar D, Shirafuji R, Battur B, Nishikawa Y, Fujisaki K. Hemalin, a thrombin inhibitor isolated from a midgut cDNA library from the hard tick Haemaphysalis longicornis. J Insect Physiol. 2009;55:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limo MK, Voigt WP, Tumbo-Oeri AG, Njogu RM, ole-MoiYoi OK. Purification and characterization of an anticoagulant from the salivary glands of the ixodid tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. Exp Parasitol. 1991;72:418–429. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(91)90088-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling S, Cheng A, Pumpens P, Michalak M, Holoshitz J. Identification of the rheumatoid arthritis shared epitope binding site on calreticulin. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado FS, Tyler KM, Brant F, Esper L, Teixeira MM, Tanowitz HB. Pathogenesis of Chagas disease: time to move on. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:1743–1758. doi: 10.2741/495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouin R, Winch P, Leontsini E, Glass G, Simon D, Hayes EB, Schwartz BS. Longitudinal evaluation of an educational intervention for preventing tick bites in an area with endemic Lyme disease in Baltimore County, Maryland. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:1039–1051. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Louw AI, Neitz AW. Evolution of hematophagy in ticks: common origins for blood coagulation and platelet aggregation inhibitors from soft ticks of the genus Ornithodoros. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:1695–1705. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelain K, Colombo A, Molina MC, Ferreira L, Lorca M, Aguillón JC, Ferreira A. Development of an immunoenzymatic assay for the detection of human antibodies against Trypanosoma cruzi calreticulin, an immunodominant antigen. Acta Trop. 2000;75:291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins I, Kepp O, Galluzzi L, Senovilla L, Schlemmer F, Adjemian S, Menger L, Michaud M, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Surface-exposed calreticulin in the interaction between dying cells and phagocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1209:77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendlovic F, Ostoa-Saloma P, Solís CF, Martínez-Ocaña J, Flisser A, Laclette JP. Cloning, characterization, and functional expression of Taenia solium calreticulin. J Parasitol. 2004;90:891–893. doi: 10.1645/GE-3325RN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menten-Dedoyart C, Couvreur B, Thellin O, Drion PV, Herry M, Jolois O, Heinen E. Influence of the Ixodes ricinus tick blood-feeding on the antigen-specific antibody response in vivo. Vaccine. 2008;26:6956–6964. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulenga A, Kim TK, Ibelli AM. Deorphanization and target validation of cross-tick species conserved novel Amblyomma americanum tick saliva protein. Int J Parasitol. 2013;43:439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Pelham HR. A C-terminal signal prevents secretion of luminal ER proteins. Cell. 1987;48:899–907. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naaby-Hansen S, Diekman A, Shetty J, Flickinger CJ, Westbrook A, Herr JC. Identification of calcium-binding proteins associated with the human sperm plasma membrane. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik UP, Patel PM, Parise LV. Identification of a novel calcium-binding protein that interats with the integrin alphaIIb cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4651–4654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanney LB, Woodrell CD, Greives MR, Cardwell NL, Pollins AC, Bancroft TA, Chesser A, Michalak M, Rahman M, Siebert JW, Gold LI. Calreticulin enhances porcine wound repair by diverse biological effects. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:610–630. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naresha S, Suryawanshi A, Agarwal M, Singh BP, Joshi P. Mapping the complement C1q binding site in Haemonchus contortus calreticulin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;166:42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak A, Ferluga J, Tsolaki AG, Kishore U. The non-classical functions of the classical complement pathway recognition subcomponent C1q. Immunol Lett. 2010;131:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oladiran A, Belosevic M. Trypanosoma carassii calreticulin binds host complement component C1q and inhibits classical complement pathway-mediated lysis. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opas M, Dziak E, Fliegel L, Michalak M. Regulation of expression and intracellular distribution of calreticulin, a major calcium binding protein of nonmuscle cells. J Cell Physiol. 1991;149:160–171. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041490120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald TJ, MacLennan DH. Isolation of a high affinity calcium-binding protein from sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:974–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YS, Lee JH, Hung CF, Wu TC, Kim TW. Enhancement of antibody responses to Bacillus anthracis protective antigen domain IV by use of calreticulin as a chimeric molecular adjuvant. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1952–1959. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01722-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Xi J, Du L, Poovaiah BW. The function of calreticulin in plant immunity: new discoveries for an old protein. Plant Signal Behav. 2012a;7:907–910. doi: 10.4161/psb.20721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Xi J, Du L, Roje S, Poovaiah BW. A dual regulatory role of Arabidopsis calreticulin-2 in plant innate immunity. Plant J. 2012b;69:489–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez G, Valck C, Molina MC, Ribeiro CH, López N, Sánchez G, Ferreira VP, Billetta R, Aguilar L, Maldonado I, Cattán P, Schwaeble W, Ferreira A. Trypanosoma cruzi calreticulin: a novel virulence factor that binds complement C1 on the parasite surface and promotes infectivity. Immunobiology. 2011;216:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic Z, Kim TK, Porter LM, Sze SH, Lewis L, Mulenga A. A 24–48h fed Amblyomma americanum tick saliva immuno-proteome. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:518. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzepecka J, Rausch S, Klotz C, Schnöller C, Kornprobst T, Hagen J, Ignatius R, Lucius R, Hartmann S. Calreticulin from the intestinal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus is a Th2-skewing protein and interacts with murine scavengerreceptor-A. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:1109–11019. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders ML, Jaworski DC, Sanchez JL, DeFraites RF, Glass GE, Scott AL, Raha S, Ritchie BC, Needham GR, Schwartz BS. Antibody to a cDNA-derived calreticulin protein from Amblyomma americanum as a biomarker of tick exposure in humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:279–285. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeler GB, Manweiler SA, Wikel SK. Ixodes scapularis: effects of repeated infestations with pathogen-free nymphs on macrophage and T lymphocyte cytokine responses of BALB/c and C3H/HeN mice. Exp Parasitol. 1999;92:239–248. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder H, Skelly PJ, Zipfel PF, Losson B, Vanderplasschen A. Subversion of complement by hematophagous parasites. Dev Comp Immunol. 2009;33:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, McManus DP. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a cDNA encoding the major endoplasmic reticulum-associated calcium-binding protein, calreticulin, from Philippine strain Schistosoma japonicum. Parasitol Int. 1999;48:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(98)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJAC. C. elegans gene encodes a protein homologous to mammalian calreticulin. DNA Seq. 1992;2:235–240. doi: 10.3109/10425179209020808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Koch GL. Multiple zones in the sequence of calreticulin (CRP55, calregulin, HACBP), a major calcium binding ER/SR protein. EMBO J. 1989;8:3581–3586. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillert CR, Lazaro EJ. Modified recalcification time (MRT): a sensitive cancer test? Review of the evidence. J Natl Med Assoc. 1995;87:687–692. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GR, Lynch NJ, Lu J, Geick A, Moffatt BE, Sim RB, Schwaeble WJ. Localisation of the C1q binding site within C1q receptor/calreticulin. FEBS Lett. 1996;397(2–3):245–249. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchitra S, Anbu KA, Rathore DK, Mahawar M, Singh BP, Joshi P. Haemonchus contortus calreticulin binds to C-reactive protein of its host, a novel survival strategy of the parasite. Parasite Immunol. 2008;30:371–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2008.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchitra S, Joshi P. Characterization of Haemonchus contortus calreticulin suggests its role in feeding and immune evasion by the parasite. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1722:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr JM, Young PJ, Morse R, Shaw DJ, Haigh R, Petrov PG, Johnson SJ, Winyard PG, Eggleton P. A mechanism of release of calreticulin from cells during apoptosis. J Mol Biol. 2010;401:799–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira AR, Hecht MM, Guimaro MC, Sousa AO, Nitz N. Pathogenesis of chagas disease: parasite persistence and autoimmunity. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:592–630. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00063-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira AR, Nitz N, Bernal FM, Hecht MM. Parasite induced genetically driven autoimmune Chagas heart disease in the chicken model. J Vis Exp. 2012;29:3716. doi: 10.3791/3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirloni L, Reck J, Terra RM, Martins JR, Mulenga A, Sherman NE, Fox JW, Yates JR, 3rd, Termignoni C, Pinto AF, da Silva Vaz I., Jr Proteomic Analysis of Cattle Tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus Saliva: A Comparison between Partially and Fully Engorged Females. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji N, Morales TH, Ozols VV, Carmody AB, Chandrashekar R. Molecular characterization of a calcium-binding protein from the filarial parasite Dirofilaria immitis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;97:69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaithilingam A, Teixeira JE, Miller PJ, Heron BT, Huston CD. Entamoeba histolytica cell surface calreticulin binds human c1q and functions in amebic phagocytosis of host cells. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2008–2018. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06287-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Duyn Graham L, Sweetwyne MT, Pallero MA, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Intracellular calreticulin regulates multiple steps in fibrillar collagen expression, trafficking, and processing into the extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7067–7078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WA, Groenendyk J, Michalak M. Calreticulin signaling in health and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:842–846. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Coons LB, Taylor DB, Stevens SE, Jr, Gartner TK. Variabilin, a novel RGD-containing antagonist of glycoprotein IIb–IIIa and platelet aggregation inhibitor from the hard tick Dermacentor variabilis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17785–17790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman L, Smith DE, Arcuri KE, Vlasuk GP. Tick anticoagulant peptide (TAP) is a novel inhibitor of blood coagulation factor Xa. Science. 1990;248:593–596. doi: 10.1126/science.2333510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Fang QQ, Keirans JE, Durden LA. Cloning and sequencing of putative calreticulin complementary DNAs from four hard tick species. J Parasitol. 2004;90:73–78. doi: 10.1645/GE-157R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Fang QQ, Sun Y, Keirans JE, Durden LA. Hard tick calreticulin (CRT) gene coding regions have only one intron with conserved positions and variable sizes. J Parasitol. 2005;91:1326–1331. doi: 10.1645/GE-344R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Schmidt O, Asgari S. A calreticulin-like protein from endoparasitoid venom fluid is involved in host hemocyte inactivation. Dev Comp Immunol. 2006;30:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]