Abstract

Introduction

Although the molecular genetics possibly underlying the pathogenesis of human thymoma have been extensively studied, its etiology remains poorly understood. Since murine polyomavirus consistently induces thymomas in mice, we assessed the presence of the novel human polyomavirus 7 (HPyV7) in human thymic epithelial tumors.

Methods

HPyV7-DNA Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), DNA-PCR and immuno-histochemistry (IHC) were performed in 37 thymomas. Of these, 26 were previously diagnosed with myasthenia gravis (MG). In addition, 20 thymic hyperplasias and 20 fetal thymic tissues were tested.

Results

HPyV7-FISH revealed specific nuclear hybridization signals within the neoplastic epithelial cells of 23 thymomas (62.2%). With some exceptions, the HPyV7-FISH data correlated with the HPyV7-DNA PCR. By IHC large T antigen (LTAg) expression of HPyV7 was detected, and double staining confirmed its expression in the neoplastic epithelial cells. Eighteen of the 26 MG-positive and 7 of the 11 MG-negative thymomas were HPyV7-positive. 40% of the 20 hyperplastic thymi were HPyV7-positive by PCR as confirmed by FISH and IHC in the follicular lymphocytes. All 20 fetal thymi tested HPyV7-negative.

Conclusions

The presence of HPyV7-DNA and LTAg expression in the majority of thymomas possibly link HPyV7 to human thymomagenesis. Further investigations are needed to elucidate the possible associations of HPyV7 and MG.

Introduction

The autoimmune disease Myasthenia Gravis (MG) has been associated with thymomas and follicular hyperplasia. Moreover the role of viral infections have been implicated in this disease. There have been several studies on the molecular genetics possibly underlying the pathogenesis of thymomas, i.e. epithelial thymic neoplasias admixed with a variable non neoplastic lymphoid component [1,2]. However, the etiology of human thymoma remains poorly understood. Over the last two decades the possible involvement of the oncogenic γ-herpesvirus Epstein-Barr (EBV) has proved debatable [3–7].

Next to EBV, polyomaviral infection has been implicated in the etiology of thymomas, based on the consistent finding that the polyomavirus strain PTA induces thymomas in mouse strains C3H/BiDa and AKR [8,9]. Polyomaviruses are small circular double-stranded DNA viruses which have been extensively used to study cell transformation in vitro and tumorigenesis in animal models. In recent years, a number of new human polyomaviruses have been identified, giving a current total of 12 [10–12]. Yet, only the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV), discovered in 2008, has been identified as a new human tumor virus [13]. MCPyV has been shown to be present in ~80% of Merkel cell carcinomas, which are highly malignant neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin [14,15]. In these, MCPyV is clonally integrated in the tumor genome, and tumor-specific oncogenic mutations within the viral genome have been identified [13,16]. Recently, polyomaviruses 6 and 7 (HPyV6 and 7) have been isolated from skin samples and characterized, but have yet not been associated with any human disease [17]. However, seroprevalence of HPyV 6 and 7 indicate that infection is common in humans, i.e. 69% and 35% [17]. A recent study has shown that the seroprevalence of HPyV7 reveals a regularly age related increase, with less than 10% in the age group below 4 years and approx 45% in the age group 10–14 years, reaching approximately 64% in adults [18]. Based on an initial DNA PCR screening testing for the presence of novel polyomaviruses in diverse human cancers, we assessed the possible role of HPyV7 in human thymic epithelial tumors and other thymic tissues.

Material and Methods

Patients and tissues

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) resection specimens were included in this study. All thymomas and 2 thymic carcinomas (19 female and 18 male; mean age 58.3 years; range 34 – 82 years), and 20 fetal gestational thymic tissues from fetus autopsies had been obtained for diagnostic and therapeutic reasons. So had 20 thymi with follicular hyperplasia, 19 of them from patients with MG (15 females, 5 males, mean age 27.4 years), of which 17 with anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibodies and 4 receiving immunosuppressive therapy (steroids). Twenty-six thymomas patients were known with a history of myasthenia gravis (MG), of which 23 were anti-AChR antibodies positive and 3 negative. Thirteen of the 26 MG-positive thymoma patients received immunosuppressive (steroids) therapy. Clinico-pathological data of thymoma and hyperplastic thymi patients are summarized in Table 1 and 2. All specimens were obtained from the Maastricht Pathology Tissue Collection (MPTC). All use of tissue and patient data was in agreement with the Dutch Code of Conduct for Observational Research with Personal Data (2004) and Tissue (2001, www.fmwv.nl).

Table 1.

| Lab ID | G | Age | MG | Thym. type | Anti-AChR | IS/Ster. | SCS ladder | sTAg-PCR (181bp) | LTAg-PCR (112bp) | FISH | IHC 2t10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1–1 | F | 73 | + | B1/B2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 2 | 1–2 | F | 75 | + | B1/B2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 3 | 1–3 | F | 57 | + | B2/B3 | + | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | 1–4 | M | 40 | + | B2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 5 | 1–5 | M | 37 | + | B3 | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + |

| 6 | 1–7 | F | 79 | + | A | − | − | + | + | + | ++ | (+) |

| 7 | 1–8 | M | 58 | + | A/B2 | + | − | + | + | + | +++ | (+) |

| 8 | 1–9 | M | 64 | − | B2 | NA | NA | + | + | + | ++ | (+) |

| 9 | 1–10 | F | 73 | + | B3 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | 1–11 | F | 34 | + | B2 | + | − | + | − | − | ++ | − |

| 11 | 1–12 | F | 36 | + | A | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 12 | 1–13 | F | 54 | − | B2 | NA | NA | + | − | + | + | (+) |

| 13 | 1–15 | F | 53 | + | B3 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| 14 | 1–16 | F | 34 | + | A | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 15 | 1–17 | M | 69 | + | AB | + | + | + | − | + | ++ | − |

| 16 | 1–18 | F | 47 | + | AB | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| 17 | 1–19 | M | 68 | − | AB | NA | NA | + | + | + | ++ | + |

| 18 | 1–20 | M | 64 | − | B3 | NA | NA | + | − | − | − | − |

| 19 | 1−21 | F | 38 | + | AB | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 20 | 1–22 | M | 65 | + | AB/B2 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| 21 | 1–23 | M | 37 | + | AB | + | − | + | + | − | + | + |

| 22 | 1−24 | M | 68 | + | B2 | + | − | + | + | + | ++ | + |

| 23 | 1–26 | M | 65 | − | AB | NA | NA | + | − | − | − | − |

| 24 | 1–28 | M | 38 | − | B1 | NA | NA | + | − | − | − | − |

| 25 | 1–30 | M | 37 | + | B2 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 26 | 1–31 | F | 82 | + | A | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 27 | 1−32 | M | 47 | + | B2 | + | – | + | – | – | – | – |

| 28 | 1–33 | F | 43 | + | B2 | + | – | + | – | – | ++ | + |

| 29 | 1–34 | M | 59 | – | AB | NA | NA | + | + | – | ++ | + |

| 30 | 1−35 | M | 45 | + | AB | + | − | + | + | + | ++ | + |

| 31 | 1–36 | F | 82 | – | AB | NA | NA | + | – | (+) | ++ | + |

| 32 | 1–37 | M | 77 | + | AB | + | − | + | − | − | +++ | (+) |

| 33 | 1–38 | F | 80 | + | AB | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 34 | 1–39 | F | 78 | − | B1 | NA | NA | + | − | − | − | − |

| 35 | 1–41 | M | 65 | − | B3 | NA | NA | + | + | (+) | +++ | + |

| 36 | 1–42 | F | 57 | + | AB | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| 37 | 1–43 | F | 78 | − | AB | NA | NA | + | − | − | ++ | (+) |

|

16/37 43.2% |

18/37 48.6% |

23/37 62.2% |

17/37 46% |

|||||||||

|

20/37 54% |

23/37 62.2% |

17/37 46% |

||||||||||

Lab ID= laboratory identification; G.= gender; MG= myasthenia gravis; Thym. type= thymoma type; anti-AChR= anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies; IS/Ster.= immunosuppression/steroids; SCS ladder= specimen control size ladder; sTAg= small T antigen; LTAg= large T antigen; HPyV7= human polyomavirus 7; FISH= fluorescence in situ hybridization using full length HPyV7 as probe; IHC= immunohistochemistry using 2t10 monoclonal antibody directed against LTAg of HPyV7; += positive; (+)= weak positive; − = negative; NA= not applicable;

Table 2.

HPyV7 detection in human thymic hyperplasias

| Clinicopathological data | HPyV7 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | G | Age | MG | Anti-AChR | IS/Ster | SCS Ladder | sTAg-PCR (181bp) | LTAg-PCR (112bp) | FISH | IHC 2t10 |

| 1 | M | 16 | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| 2 | F | 15 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| 3 | F | 20 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| 4 | F | 25 | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | (+) |

| 5 | F | 24 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | (+) |

| 6 | F | 26 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + |

| 7 | F | 30 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| 8 | F | 32 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| 9 | F | 40 | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | F | 13 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − |

| 11 | M | 40 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | (+) |

| 12 | F | 34 | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| 13 | F | 26 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | (+) |

| 14 | F | 24 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| 15 | F | 31 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| 16 | F | 22 | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 17 | F | 48 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | (+) |

| 18 | M | 39 | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| 19 | M | 31 | − | NA | NA | + | − | + | − | (+) |

| 20 | M | 12 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + |

G.= gender; MG= myasthenia gravis; anti-AChR= anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies; IS/Ster.= immunosuppression/steroids; NA= not applicable; SCS ladder= specimen control size ladder; sTAg= small T antigen; LTAg= large T antigen; HPyV7= human polyomavirus 7; ; FISH= fluorescence in situ hybridization using full length HPyV7 as probe; IHC= immunohistochemistry using 2t10 monoclonal antibody directed against LTAg of HPyV7;+= positive; (+)= weak positive; − = negative;

HPyV7 detection by DNA PCR

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole FFPE tissue sections using a DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA quality and integrity was first assessed by specimen control size (SCS) ladder (Table 1 and 2) as described [19]; we excluded any sample where it was inadequate. HPyV7 DNA PCR was performed as described previously, using oligonucleotides targeting the small T antigen (181bp) and the large T antigen (112 bp) [17,20].

Detection of HPyV7 by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

The HPyV7 full-length probe was obtained from Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA, and linearized. FISH was performed on 3 μm thick FFPE sections according to Hopman et al. with modifications [21]. In brief: deparaffinized sections were incubated with 0.2M HCl, for 20 min (and washed in dH2O and 2x SSC), and then with 1 M NaSCN for 30 min at 80°C. After further washing, sections were digested with1 mg/ml pepsin (2500 – 3500 U/mg; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO), pH 2. To test HPyV7-probe specificity, sections were first treated with 0.2 g/100 ml pepsin (Sigma) in 0.01 M HCl at 37°C for 10 min and then with DNase I (Qiagen) for 30 min at 37°C with 5.7 U in RDD buffer (Qiagen), before cooling on ice, washing twice in 2x SSC and post-fixing in 4% formaldehyde. After washing in 2x SSC and rinsing in dH2O, the sections were dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series. The biotin-labeled HPyV7 probe was added under the coverslip at a concentration of 10ng/μl in LCI/WCP buffer (Vysis, Abott, IL) together with 50x excess human COT-1 DNA (Vysis) and 50x tRNA from S. cerevisiae (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). Denaturation of the probe and the target DNA was carried out simultaneously for 5 min at 80°C prior to hybridization overnight at 37°C in a humid chamber (Thermobrite, Abbott, IL). Unhybridized probe was stringently washed away from the preparations in 2x SSC, pH 7.0 at 70°C for 2 min. The biotin (Bio) labelled probe was detected with sequential incubations with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated avidin (1:500; Vector, Brunswig Chemie, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), biotin-conjugated goat anti-avidin (1:100; Vector) and FITC-conjugated avidin 1:500, all for 30 min at 37°C and diluted in Boehringer Blocking reagent (Roche). Finally, the slides were dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series and mounted in 0.2μg/ml DAPI-Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, CA). HPyV7 FISH signals were detected using a DM 5000 B fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with DAPI, TR (Texas red) and FITC filters. Images were recorded with a Leica DC 300 Fx camera (Leica). FISH fluorescence intensity, signal numbers and sizes for strong and weak nuclear FISH signals were evaluated independently by 5 investigators (DR, MK, EJS, AH, AzH) according to the criteria in Hafkamp et al. [22]. After DNAse pretreatment (see above) of the slides of HPyV7 DNA positive cases, as assessed by PCR and sequencing, no specific nuclear HPyV7 hybridization signals were seen. In addition, specificity of the HPyV7 probe was assessed by the omission of the HPyV7 probe revealing no specific FISH hybridization signals in HPyV7 DNA positive skin and thymic tissues. Crosshybridization with MCPyV was excluded by performing HPyV7 FISH on the MCPyV-positive MKL1 cell line, which did not show any specific hybridization signals (Fig. S1) [13].

Immunohistochemistry and double staining

The following antibodies and dilutions were used: anti-Pancytokeratin AE1/3 (DAKO; Glostrup, Denmark; “Ready to use Antibody”); monoclonal antibody 2T10 against LTAg of HPyV7 was provided by C. Buck, NCI, Bethesda, USA, and used at 1:100 with the EnVision FLEX™ visualization Kit K8008 DAKO according to standard protocols. When FISH was followed by IHC, the protocols were adapted slightly.

Results

HPyV7 detection in thymic epithelial tumors by DNA PCR and FISH

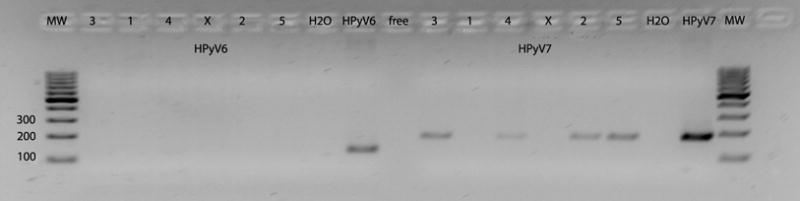

Screening of diverse human cancers for the presence of novel polyomaviruses revealed that HPyV7 was frequently present in human thymomas but not HPyV6. (Fig. 1). Twenty (54%) of the 37 thymomas tested positive for HPyV7-DNA by PCR (Table 1). All PCR products were sequenced and confirmed the presence of HPyV7, with only minor nucleotide differences between them. One of the 2 thymic carcinomas was HPyV7-DNA positive and the other negative.

Figure 1.

PCR-DNA of HPyV6 (left panel) and HPyV7 (right panel) in human epithelial thymic tumors (3,1,4,2,5) and non-neoplastic mediastinal fatty tissue (X) using a plasmid containing human polyomavirus 6 (123 base pair) or 7 (181 base pair). No amplification products were found in HPyV6 PCR whereas specific PCR products were found for HPyV7. H2O = water control; pos = positive control; free= free space, MW= molecular weight marker.

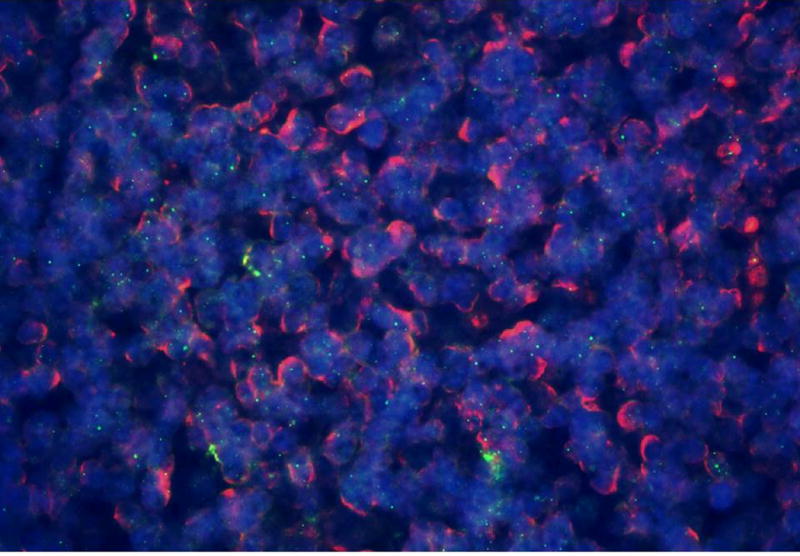

By FISH, HPyV7-specific nuclear hybridization signals were found in 23 thymomas (62.2%) (Fig. 2; summarized in Table 1). In the 15 thymomas with strong to very strong specific nuclear hybridization signals and 8 revealed weak positivity. In the thymomas with strong nuclear hybridization signals almost all neoplastic cells were HPyV7-positive. They were more heterogeneous in the 8 with weaker signals. HPyV7-FISH and anti-pancytokeratine immunofluorescence double labeling confirmed that the specific nuclear hybridization were mostly restricted to epithelial cells (Fig. 2); only in a few tumors was it also found in rare lymphocytes. HPyV7 did not correlate with any WHO thymoma subtype (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Overlay of HPyV7 FISH (green dots) and pancytokeratine AE1/AE3 immunofluorescence (red membrane staining) and DAPI staining of the nuclei (blue) of thymoma 1–22 (Table 1). Specific detection of nuclear HPyV7 DNA by FISH (green dots) in epithelial cells of a thymoma as indicated by the red membrane staining.

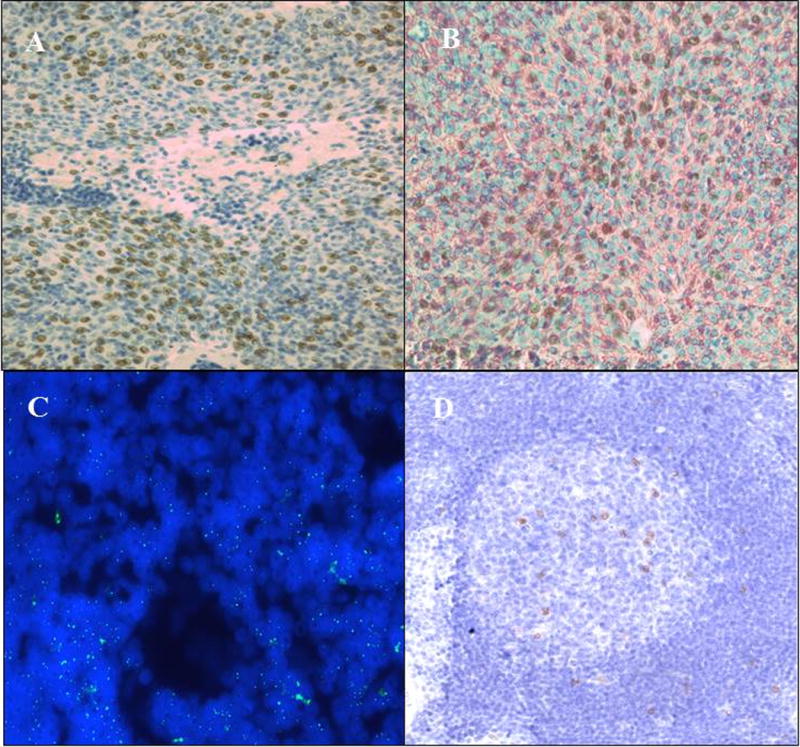

Large T antigen of HpyV7 is highly expressed in human thymomas

Marked LTAg expression was found by IHC in 17 (46%) of the thymomas within the epithelial cells (Fig. 3a,b), but not always in every cell in the positive cases, unlike FISH. Overall, LTAg labeling was in good agreement with the HPyV7-DNA PCR and/or the HPyV7-FISH.

Figure 3.

3A Specific nuclear expression of the HPyV7 LTAg (dark brown) in thymoma 1–3 (Table 1) as assessed by immunohistochemistry. Epithelial cells are positive whereas the lymphoid cells do not show HPyV7-LTAg expression.

3B Immunohistochemical double staining technique confirms the expression of the HPyV7 LTAg in the nuclei (dark brown) of thymic epithelial cells as identified by the red membrane staining with the pancytokeratine antibody AE1/AE3 in thymoma 1–3 (Table 1).

3C Representative result of the HPyV7 FISH in a follicular center of a hyperplastic thymus. The green nuclear dots represent the HPyV7 signals obtained by the hybridization with HPyV7 probe.

3D Specific nuclear expression of the HPyV7 LTAg (dark brown) in a hyperplastic thymus. Expression of HPyV7 LTAg is mostly restricted to follicular lymphocytes.

Detection of HPyV7 in thymic follicular hyperplasia DNA PCR and FISH

HPyV7- DNA was detected in 40% (n= 8) of the hyperplastic thymi. By HPyV7-FISH, the proportion of HPyV7-positive cases reached 65% (n=13). Importantly, specific nuclear HPyV7-hybridization signals were mostly restricted to scattered follicular B-cells, which possibly explain the different results of PCR and FISH. In 6 of these 20 hyperplastic thymi, IHC revealed mostly weak nuclear expression of the LTAg in some lymphoid cells in the follicles (Fig. 3c,d)

Association of HPyV7 and myasthenia gravis

Of the 26 patients with HPyV7-positive thymomas, 19 were known to have MG. Of the 11 non-MG thymomas 7 were HPyV7-positive and 4 were HPyV7-negative (Table 1).

The only non-MG-hyperplastic thymus was HPyV7-positive.

HPyV 7 is not detected in fetal thymus

Using HPyV7 DNA PCR, none of the fetal thymi, which were also tested for sufficient DNA quality and integrity – tested positive for HPyV7.

Discussion

With sophisticated new detection techniques, the number of novel human polyomaviruses has increased in the past 6 years [23]. However, of the 12 known human polyomaviruses, currently, only the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) has been shown to be associated with a human cancer, i.e. the Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). Viral integration, tumor-specific viral mutations within the LTAg of MCPyV, and consistent epidemiology of MCPyV with MCC have led to the classification of MCPyV as a class 2A carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [13–16, 24].

Here we systematically assessed the presence of HPyV7 in human thymic epithelial tumors by diverse molecular techniques [17]. Focusing on different parts of the HPyV7 genome, we found HPyV7- DNA in 54% of the 37 thymomas. At the single cell level, use of HPyV7-FISH demonstrated specific nuclear hybridization signals within the epithelial cells in 62.2% of the thymomas and only occasionally in lymphocytes. The discrepancies between the PCR and FISH results most likely reflect the varying proportions of positive cells in different tumors. Interestingly, however, thymomas 1–37 and 1–43 (Table 1) gave strong hybridization signals in HPyV7 FISH plus weak IHC labeling for its LTAg despite negativity by HPyV7 PCR. Since we excluded technical reasons as far as possible, and also the presence of other known human polyomaviruses, these findings might hint at the presence of an as yet unidentified but closely related polyomavirus.

Our double labeling clearly showed that the great majority of the cells positive for viral DNA or protein antigens were epithelial rather than lymphoid. Thus, the expression of the HPyV7-LTAg in thymomas may hint at a role for HPyV7 in thymomagenesis. Although many other polyoma viral LTAg can act as oncogenes, no information is yet available about the oncogenic capacity of HPyV7. Notably, its LTAg was expressed quite strongly in some of the epithelial thymic tumors, especially compared to the variable numbers of HPyV7 LTAg lymphoid cells in thymic follicles (Fig. 2D).

In the hyperplastic thymi HPyV7 DNA was detected by PCR in 40% and by FISH in 65%. The discrepancy can readily be explained by the number of cells detected by HPyV7-FISH, which varied over a wide range. By using HPyV7 FISH and an anti-HPyV7 LTAg monoclonal antibody, HPyV7-positivity was found to be largely restricted to follicular lymphoid rather than epithelial cells. That is in line with the known B lymphotropism of some human polyomaviruses [12,25,26]. This finding is interesting, because if HPyV7 remains latently present in follicular B-cells it could mean that it might be interesting to test also B-cell non Hodgkin lymphomas for the presence of HPyV7. In addition, it may contribute to immunological alterations which might initiate or perpetuate immunological diseases such as MG as has recently been speculated for the oncogenic γ-herpesvirus Epstein-Barr (EBV) [27]. However, data on the finding of EBV in myasthenia gravis thymus are quite controversial, ranging between very high prevalence to almost not present [28,29]. Although surprising that a highly reproducible standard routine testing for the presence of EBV (e.g. EBV-encoded RNAs- RNA in situ hybridization) in a histopathological lymphoma diagnostic setting fails the extent of reproducibility in the setting of MG thymus, it seems that further conclusive studies are needed in order to assess the role of EBV in MG thymi. The interesting recent finding of poliovirus in a subset of MG thymi needs to be independently confirmed [30].

The fact that we did not find any HPyV7-positivity in gestational fetal thymic tissues reveals that HPyV7 infection occurs in the postnatal period and also indirectly leans support to a possible role for HPyV7 in human thymomagenesis in the context of the quite frequent finding within the epithelial cells of human thymic epithelial tumors.

In conclusion, the present study is the first to demonstrate the presence and association of HPyV7 in thymic epithelial tumors by diverse molecular techniques. Our failure to detect any signs of HPyV7 in fetal thymic tissues suggests that HPyV7 reaches the thymus post-natal or later in life, which is in good agreement with the recent study on HPyV7 age related seroprevalence [18]. Its contrasting 40 – 60% prevalence in thymomas also hints at a possible role for HPyV7 in their initiation, but requires independent confirmation in larger series.

Further studies would also be needed to assess the oncogenic potential of HPyV7, e.g. viral integration, mutational analyses of the LTAg and in vitro transformation. Although HPyV7 is present in the majority of MG-associated thymomas the numbers of cases investigated in this study do not allow a conclusion on a possible role of HPyV7 in MG.

Keypoints.

Detection of HPyV7 DNA in the neoplastic cells of the majority of thymomas

HPyV7 is potentially involved in human thymomagenesis

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, et al., editors. Pathology and and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Thymus and Heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004. Introduction in World Health Organization Classification of Tumours; pp. 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ströbel P, Hohenberger P, Marx A. Thymoma and thymic carcinoma: molecular pathology and targeted therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:S286–90. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f209a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuire LJ, Huang DP, Teoh R, et al. Epstein-Barr virus genome in thymoma and thymic lymphoid hyperplasia. Am J Pathol. 1988;131:385–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borisch B, Kirchner T, Marx A, et al. Absence of the Epstein-Barr virus genome in the normal thymus, thymic epithelial tumors, thymic lymphoid hyperplasia in a European population. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1990;59:359–365. doi: 10.1007/BF02899425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inghirami G, Chilosi M, Knowles DM. Western thymomas lack Epstein-Barr virus by Southern blotting analysis and by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:1429–1436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel PJ. Absence of latent Epstein-Barr virus in thymic epithelial tumors as demonstrated by Epstein-Barr-encoded RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization. APMIS. 2000;108:393–397. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-74.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen PC, Pan CC, Yang AH, et al. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus genome within thymic epithelial tumours in Taiwanese patients by nested PCR, PCR in situ hybridization, and RNA in situ hybridization. J Pathol. 2002;197:684–688. doi: 10.1002/path.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wirth JJ, Fluck MM. Immunological elimination of infected cells as the candidate mechanism for tumor protection in polyomavirus-infected mice. J Virol. 1991;65:6985–6988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6985-6988.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanjuan N, Porras A, Otero J, et al. Expression of major capsid protein VP-1 in the absence of viral particles in thymomas induced by murine polyomavirus. J Virol. 2001;75:2891–2899. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2891-2899.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Ghelue M, Khan MT, Ehlers B, et al. Genome analysis of the new human polyomaviruses. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22:354–377. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siebrasse EA, Reyes A, Lim ES, et al. Identification of MW polyomavirus, a novel polyomavirus in human stool. J Virol. 2012;86:10321–10326. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01210-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeCaprio JA, Garcea RL. A cornucopia of human polyomaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:264–276. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassem A, Schöpflin A, Diaz C, et al. Frequent detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinomas and identification of a unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5009–5013. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker JC, Houben R, Ugurel S, et al. MC polyomavirus is frequently present in Merkel cell carcinoma of European patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:248–250. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shuda M, Feng H, Kwun HJ, et al. T antigen mutations are a human tumor-specific signature for Merkel cell polyomavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16272–16277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806526105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schowalter RM, Pastrana DV, Pumphrey KA, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicol JT, Robinot R, Carpentier A, et al. Age-specific seroprevalences of merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomaviruses 6, 7, and 9, and trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:363–368. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00438-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Dongen JJ, Langerak AW, Brüggemann M, et al. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immune-globulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia. 2003;17:2257–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncavage EJ, Pfeifer JD. Human polyomaviruses 6 and 7 are not detectable in Merkel cell polyomavirus-negative Merkel cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:790–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopman AH, Kamps MA, Smedts F, et al. HPV in situ hybridization: impact of different protocols on the detection of integrated HPV. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:419–428. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hafkamp HC, Manni JJ, Haesevoets A, et al. Marked differences in survival rate between smokers and nonsmokers with HPV 16-associated tonsillar carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2656–2664. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalianis T. Immunotherapy for polyomaviruses: opportunities and challenges. Immunotherapy. 2012;4:617–628. doi: 10.2217/imt.12.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouvard V, Baan RA, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of malaria and of some polyomaviruses. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:339–340. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toracchio S, Foyle A, Schroller V, et al. Lymphotropism of Merkel cell polyomavirus infection, Nova Scotia, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1702–1709. doi: 10.3201/eid1611.100628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pantulu ND, Pallasch CP, Kurz AK, et al. Detection of a novel truncating Merkel cell polyomavirus large T antigen deletion in chronic lympho-cytic leukemia cells. Blood. 2010;116:5280–5284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-269829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavalcante P, Serafini B, Rosicarelli B, et al. Epstein-Barr virus persistence and reactivation in myasthenia gravis thymus. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:726–738. doi: 10.1002/ana.21902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer M, Höls AK, Liersch B, et al. Lack of evidence for Epstein-Barr virus infection in myasthenia gravis thymus. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:515–518. doi: 10.1002/ana.22522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kakalacheva K, Maurer MA, Tackenberg B, et al. Intrathymic Epstein-Barr virus infection is not a prominent feature of myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:508–514. doi: 10.1002/ana.22488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavalcante P, Barberis M, Cannone M, et al. Detection of poliovirus-infected macrophages in thymus of patients with myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2010;74:1118–11126. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d7d884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]