Abstract

Concurrent damage to the lateral frontal and parietal cortex is common following middle cerebral artery infarction leading to upper extremity paresis, paresthesia and sensory loss. Motor recovery is often poor and the mechanisms that support, or impede this process are unclear. Since the medial wall of the cerebral hemisphere is commonly spared following stroke, we investigated the long-term (6 and 12 month) effects of lateral frontoparietal injury (F2P2 lesion) on the terminal distribution of the corticospinal projection (CSP) from intact, ipsilesional supplementary motor cortex (M2) at spinal levels C5 to T1. Isolated injury to the frontoparietal arm/hand region resulted in a significant loss of contralateral corticospinal boutons from M2 compared to controls. Specifically, reductions occurred in the medial and lateral parts of lamina VII and the dorsal quadrants of lamina IX. There were no statistical differences in the ipsilateral corticospinal projection. Contrary to isolated lateral frontal motor injury (F2 lesion) which results in substantial increases in contralateral M2 labeling in laminae VII and IX (McNeal et al., Journal of Comparative Neurology 518:586-621, 2010), the added effect of adjacent parietal cortex injury to the frontal motor lesion (F2P2 lesion) not only impedes a favorable compensatory neuroplastic response, but results in a substantial loss of M2 CSP terminals. This dramatic reversal of the CSP response suggests a critical trophic role for cortical somatosensory influence on spared ipsilesional frontal corticospinal projections, and that restoration of a favorable compensatory response will require therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Pyramidal Tract, Frontal Lobe, Parietal Lobe, Corticofugal, Neurosurgical Resection, Plasticity, Spinal Cord, Motor Recovery, Hand Movements

INTRODUCTION

The corticospinal projection (CSP) is the longest fiber pathway in the central nervous system. Its circuitry specializations, especially pronounced in some higher-order primates, establish the underlying capacity to produce highly coordinated, fractionated movements of the digits. Although an extensive region of the cerebral cortex is known to harbor corticospinal projection neurons (Biber et al., 1978; Murray and Coulter, 1981; Nudo and Masterton, 1988, 1990; Dum and Strick 1991; Galea and Darian-Smith, 1994; Luppino et al., 1994; Rozzi et al., 2006) the projection from the primary motor cortex (M1) is widely known for its special structural and functional contributions to generating contralateral skilled voluntary hand movements. These coordinated hand movements include opposition of the tips of the fingers to the thumb, grip formation, and object manipulation (e.g., Cheney et al., 1991; Porter and Lemon, 1993; Lemon et al., 2004; Park et al., 2004; Martin, 2005; Lemon and Griffiths, 2005; Schieber, 2007; Lemon, 2008; Griffin et al., 2009; Boudrias et al. 2010a).

Numerous experimental approaches have been instrumental in defining the unique structural and functional characteristics of the M1 corticospinal projection in non-human primates and one of the oldest and enduring methods includes precentral cortical resection (e.g., Ferrier, 1886, Graham Brown and Sherrington, 1913; Leyton and Sherrington, 1917; for review see Vilensky and Gilman, 2002; Darling et al., 2011; Wiesendanger, 2011). After isolated resection of M1, a short period of flaccid paralysis ensues that is followed by remarkable recovery of upper extremity movements. However, a hallmark clinical feature of extensive precentral resection which includes the anterior bank of the central sulcus, is more lasting deficits in fine control of contralesional digit movements for manipulating small objects in macaques (Ogden and Franz 1917, Fulton and Kennard 1934) and humans (Bucy, 1949). In non-human primates, adaptive mechanisms that accompany precentral injury and upper limb recovery include physiological reorganization of adjacent lateral premotor cortex (e.g., Glees and Cole, 1950; Black et al., 1974; Nudo et al., 1996; Rouiller et al., 1998; Liu and Rouiller, 1999; Frost et al., 2003; Dancause et al., 2006) and rewiring of corticocortical connections from the ventrolateral premotor cortex (Dancause et al., 2005). In the supplementary motor cortex (M2, SMC or SMA-proper), increased unit activity (Aizawa et al., 1991), expansion of the distal forelimb region (Esiner-Janowicz et al., 2008) and enhanced terminal labeling of corticospinal projections (McNeal et al., 2010) have been shown to occur after lateral frontal motor injury.

In contrast to the abundant studies examining the effects of isolated lateral frontal motor injury on recovery of upper extremity movements in non-human primates, there have been few experimental studies examining the effects of isolated postcentral injury on upper extremity movement. The available evidence from some highly regarded authorities show that localized parietal lobe lesions may produce serious motor deficits. Notably, in a rarely cited study, Kennard and Kessler (1940) reported that isolated postcentral (primary somatosensory cortex or S1) resection primarily affects fine motor acts of the digits. These deficits were characterized by a lack of precision in both direction and extent of movements, especially during grooming activities. Permanent loss of tactile placing was noted and accuracy of manipulation by the digits improved only when visual attention was used. Remarkably, motor recovery deficits were found to be more enduring following postcentral (somatosensory) injury than after precentral (somatomotor) lesions, with progressive improvements in recovery occurring over longer periods of time following precentral injury. Denny-Brown (1950) described postcentral lesions as having a devastating effect on motor function that is equivalent to area 4 (M1) ablation with additional persistent depression of posture and postural reflexes. Yet adaptive frontomotor mechanisms that accompany motor recovery following isolated postcentral injury have not been studied in the non-human primate model. However, higher than normal current levels are required to elicit movement from M1 following dorsal column lesions that disrupt ascending proprioceptive and tactile input to S1 (Kambi et al., 2011), indicating that frontomotor mechanisms are likely to be altered following somatosensory deprivation. This change in stimulation threshold is also accompanied by reorganization of the M1 thumb area map such that intracortical microstimulation primarily causes abduction-adduction movements instead of primarily flexion-extension movements as in control monkeys.

It is clear that studies applying localized lesions confined to either the precentral (M1) or postcentral (primary somatosensory cortex or S1) region were designed, in part, with the intent to determine each representative contribution to altered patterns of motor performance after injury, as well as the negative or positive effects that each lesion type may have on the motor recovery process. However, it would be of substantial interest to study the effects of combined lateral frontal (M1) and lateral parietal (S1) lobe injury on the recovery process of upper extremity movements in the non-human primate model because this cortical territory is often compromised as a collective unit in a large number of stroke patients as indicated by the high incidence of motor weakness and sensory abnormalities resulting from middle cerebral artery (MCA) embolic disease (Yoo et al., 1998). Indeed, the MCA supplies the lateral part of the frontal and parietal lobes (e.g., Tatu et al., 1998; Duvernoy, 1999) and is the most frequently occluded artery in cerebrovascular pathology (e.g., Bogousslavsky et al., 1990; Carrera et al., 2007). The poor motor recovery often noted in these patients suggests different neuronal response mechanisms, that are perhaps more unfavorable and limiting, may accompany this type of injury versus isolated lesions limited to either the precentral or postcentral regions alone.

One cortical area that would be of significant interest to study compensatory recovery mechanisms following lateral frontoparietal injury is the medial frontal motor region. Indeed, the anterior cerebral artery supplies the medial wall of the cerebral hemisphere and is spared in the majority (>97%) of stroke patients (Bogousslavsky and Regli, 1990; Kazui et al, 1993; Kumral et al., 2002; Carrera et al., 2007). As we have previously noted (McNeal et al., 2010), it is of particular significance that the supplementary motor cortex (M2), resides in the vascular territory of the anterior cerebral artery. Moreover, M2 gives rise to the second strongest (only to M1) corticospinal projection (Dum and Strick 1991; Galea and Darian-Smith, 1994) and is involved in higher-order motor functions including motor planning and movement sequencing (Tanji, 1994; Nachev et al., 2008; Passingham et al., 2010). As such, M2 may represent an important resource in the recovery process of upper extremity movement following common, lateral frontoparietal cortical injury. Furthermore this cortex may contribute to the recovery of fine motor control of the digits since M2 has a relatively prominent projection to alpha motoneuron rich lamina IX (Dum and Strick, 1996; Maier et al., 2002; McNeal et al., 2010) which has recently been characterized as a monosynaptic projection (Maier et al., 2002; Boudrias et al., 2006, 2010b).

Hence, the objective of this study was to examine the effects of lateral frontoparietal injury on the spared corticospinal projection from the supplementary motor cortex (M2) following spontaneous long-term (6 and 12 months) recovery. In this report, we find that in contrast to isolated lateral frontal motor injury (F2 lesion), which gives rise to a substantial increase in the contralateral corticospinal projection from M2 in the form of greater numbers of terminal boutons and enhanced terminal fiber length versus controls (McNeal et al., 2010), the added effect of anterior parietal lobe injury (F2P2 lesion) has devastating consequences on the contralateral corticospinal projection from M2. This has important implications for humans who probably rely extensively, if not exclusively, on the corticospinal projection for performing precisely coordinated hand and finger movements.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

All monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were housed and cared for in a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC) approved and inspected facility. All behavioral, surgical and experimental protocols were approved by the University of South Dakota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and conducted in accordance with USDA, National Institutes of Health, and Society for Neuroscience guidelines for the ethical treatment of animals. Prior to initiating the study, each monkey was evaluated by a veterinarian with primate experience and judged to be healthy and free of any neurological deficit.

Study Design

To accomplish the aims of this investigation, the organization of the CSP arising from M2 was studied at spinal levels C5 to T1 in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Four control monkeys from our previous work (McNeal et al., 2010 – see Table 1) and one additional monkey (SDM84) served as the control group (Table 1). Four other monkeys received an isolated neurosurgical lesion (F2P2 lesion) using coagulation/subpial aspiration that involved removal of the arm representation of M1 (area 4), lateral premotor cortex (LPMC or area 6), and arm region of the adjacent somatosensory cortex (S1 or areas 3, 1 and 2) including the rostral part of area PE (or area 5) of the superior parietal lobule. Detailed descriptions of the neurosurgical exposure, intracortical microstimulation method, and aspiration method have been reported previously (Morecraft et al., 2001; 2002, 2007a; McNeal et al., 2010). In the control group (Table 1), each monkey was injected with the tract tracer fluorescein dextran (FD) into the central region of the arm representation of M2 and survived for 33 days prior to sacrifice. The 4 F2P2 lesion monkeys were also injected with the same tracer (FD) into the central region of the arm representation of M2 in the ipsilesional hemisphere 33-34 days prior to sacrifice but after 6 or 12 months of recovery from the induced lateral frontoparietal lesion. Following immunohistochemical tissue processing for microscopic visualization of the FD tract tracer in all control and lesion cases, terminal boutons were estimated in Rexed’s lamina at spinal levels C5 to T1 using stereological counting methods, which is widely acknowledged as the most accurate method to quantify these neuronal structures (Glaser et al., 2007; West, 2012). Terminal fiber lengths were also estimated in lamina VII and IX and within the lateral corticospinal tract (LCST) at C5 and C8 using stereology. Definitions of general anatomical terminology adopted for this study have been described previously (McNeal et al., 2010, see Fig. 7). For the present report M1 was further subdivided into gyral, or rostral part (M1r) and a sulcal, or caudal part (M1c) (Rathelot and Strick, 2009) (Table 2). Similarly, the somatosensory cortex was subdivided into a rostral (S1r) component that lined the fundus and posterior bank of the central sulcus (cytoarchitectonic areas 3, and 1) and caudal part (S1c) that resides on the gyral surface of parietal cortex (cytoarchitectonic areas 1 and 2) (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Description of the Experimental Parameters for Each Case

| Case | Sex | Age (yrs.) |

Weight (kg) |

Area Injected |

Tracer/ Injections |

Total Vol. (μL) |

Injection Core vol. (mm3) |

Injection Halo vol. (mm3) |

Post- Injection survival (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | |||||||||

| SDM41 | male | 4.6 | 4.8 | M2 arm | FD/3 | 1.2 | 38.7 | 84.6 | 33 |

| SDM54 | male | 9.0 | 9.2 | M2 arm | FD/3 | 1.2 | 33.0 | 67.7 | 33 |

| SDM62 | female | 3.2 | 3.2 | M2 arm | FD/3 | 1.2 | 31.5 | 60.4 | 33 |

| SDM77 | male | 8.3 | 9.6 | M2 arm | FD/3 | 1.2 | 14.7 | 51.6 | 33 |

| SDM84 | male | 15.3 | 11.7 | M2 arm | FD/3 | 1.2 | 20.9 | 85.9 | 33 |

| 6 Mo. Survival | |||||||||

| SDM87 | female | 17.5 | 10.9 | M2 arm | FD/3 | 0.9 | 15.5 | 47.8 | 33 |

| SDM91 | female | 8.3 | 5.6 | M2 arm | FD/3 | 1.2 | 36.6 | 119.7 | 34 |

| 12 Mo. Survival | |||||||||

| SDM81 | female | 16.0 | 6.0 | M2 arm | FD/3 | 0.9 | 19.0 | 55.5 | 33 |

| SDM83 | female | 4.7 | 7.0 | M2 arm | FD/3 | 0.9 | 19.5 | 89.5 | 33 |

Figure 7.

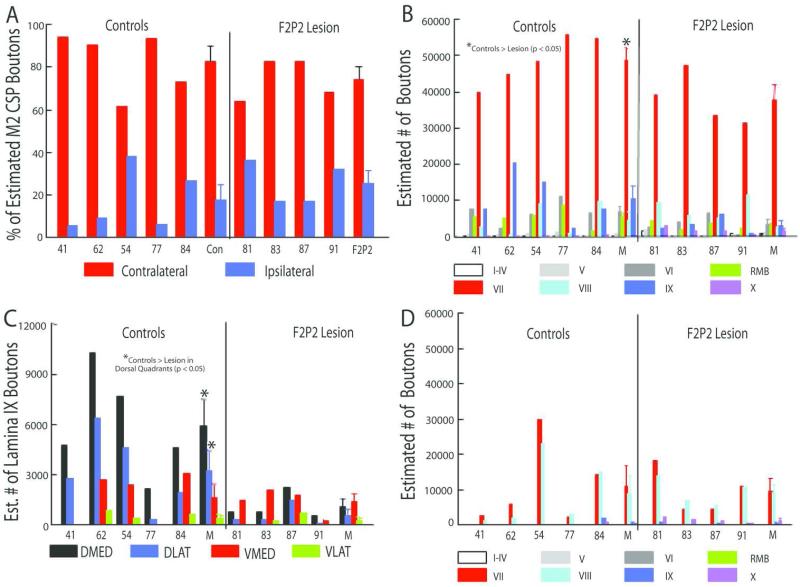

A: Percentages of all boutons in the contralateral and ipsilateral projections from M2 to C5-T1 for each control and F2P2 lesioned monkey. B: Estimated numbers of labelled boutons in the contralateral CSP from M2 to C5-T1 laminae for each control and F2P2 lesioned monkey. C: Estimated numbers of lamina IX boutons in each quadrant in each control and F2P2 lesioned monkey. D: Estimated numbers of labeled boutons in the ipsilateral CSP from M2 to C5-T1 laminae in each control and F2P2 lesioned monkey. Mean (M) values of controls and lesioned monkeys are also provided in each graph. Error bars on the bars of mean values are 1 S.E.M.

TABLE 2.

Lesion/Spared Volume Data for F2P2 Cases (mm3)

| Case | Total lesion (white matter) |

Total lesion (grey matter) |

LPMCd lesion |

LPMCv lesion |

M1 ros lesion |

M1 ros spared |

M1 caudal lesion |

M1 caudal spared |

S1 ros lesion |

S1 ros spared |

S1 caudal lesion |

PE/ area5 lesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDM 81 | 13.55 | 179.54 | 26.26 | 8.01 | 51.65 | 9.12 | 22.88 | 52.61 | 15.29 | 63.05 | 38.35 | 14.50 |

| SDM 83 | 16.11 | 261.18 | 83.59 | -.- | 68.12 | -.- | 29.38 | 29.13 | 24.11 | 46.08 | 41.21 | 11.43 |

| SDM 87 | 56.21 | 329.87 | 41.61 | 42.07 | 107.65 | -.- | 32.70 | 38.24 | 7.30 | 22.64 | 47.31 | 47.68 |

| SDM 91 | 52.94 | 274.30 | 39.44 | -.- | 80.45 | -.- | 72.72 | -.- | 42.80 | 18.40 | 25.61 | 7.80 |

Before the frontoparietal lesion was induced, the preferred hand in all 4 F2P2 lesion group monkeys was determined by deriving a handedness index for each animal (Nudo et al., 1992; Pizzimenti et al., 2007) which served to identify the hemisphere that would be lesioned (contralateral to the preferred hand). In addition, all monkeys in the lesion group were trained on two fine motor behavioral tasks that involved reaching for small food targets using a modified movement assessment panel (mMAP) (Darling et al. , 2006) and a modified dexterity board (mDB) (Pizzimenti et al. , 2007). Specifically, after reaching stable levels of motor performance on each task (approximately 18-28 testing sessions after learning the task), each monkey was lesioned and then tested once every week (on both tasks) for the first 2 months post-injury and once every other week (on both tasks) thereafter. Motor performances on individual trials were quantified from 3-dimensional video recordings of movements to acquire small food pellets in the mDB task (Pizzimenti et al. , 2007) and from recordings of 3-dimensional forces applied to small carrot chips for the mMAP task (Darling et al. , 2006). The animals in the control group were provided with daily distal upper extremity motor enrichment activities (such as a foraging board) to compensate for potential learning/training induced effects of the F2P2 lesioned animals during the brief manual testing sessions (maximum of 40 trials with each hand to acquire the food targets).

Neurosurgical and Neuroanatomical Procedures

Neurosurgical and Tract Tracing Procedures

Frontal lobe exposure was performed following neurosurgical procedures previously described (Morecraft et al., 2001, 2002, 2007a; McNeal et al., 2010). Briefly, with each animal under isofluorane anesthesia, a skin flap was made over the cranium followed by a bone flap over the midline region. In control cases and lesion cases, the medial surface of the frontal lobe was exposed by incising the dura matter and ligating bridging vessels emptying into the superior sagittal sinus with the aid of a surgical microscope. Small pieces of cottonoid pads were then gently packed into the interhemispheric sulcus to slowly increase the interhemispheric space allowing for the cortex lining the medial frontal surface to be clearly visible.

In both the control and lesion cases the location of the arm representation of M2 was determined by intracortical microstimulation (McNeal et al., 2010). Then the anterograde neural tract tracer FD (10% solution in saline comprised of an equal quantity of both 3,000 MW and 10,000 MW volumes) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was injected into the central region of the physiologically localized arm representation of M2. Specifically, graded pressure injections with a Hamilton microsyringe were made into three separate penetration sites spaced 1-1.5mm apart in a triangular pattern, 2.5 - 3.5 mm below the medial cortical surface at approximately a 10-20° angle from the vertical axis. In the control cases, a total of 1.2 μl of neural tracer was injected (i.e., 0.4 μl per penetration site) (Table 1). The tract tracer injections in the F2P2 lesion cases were performed in identical fashion with the exception that slightly less tracer volume (total of 0.9 μl; 0.3 μl per penetration site) was injected in 3 of the lesion cases (Table 1) and a volume that was equal to the controls (1.2 μl) was injected in one lesion case (SDM91) (Table 1). The smaller volume of FD injected into first the 3 F2P2 lesion animals were originally made to match the experimental design for our F2 lesion animals (removal of M1 arm/hand region and adjacent LPMC; n=4; see McNeal et al., 2010). In the F2 lesion experiments, we were able to clearly demonstrate that 0.9 μl of FD injected into the spared M2 arm area provided more than adequate amount of tracer volume to label 2-3 times the number of labeled CSP terminal boutons (and terminal axon fiber length) versus all the control cases that received 1.2 μl of FD (McNeal et al., 2010). To verify that the experimental results of the F2P2 lesion cases receiving 0.9 μl of FD reflected a true loss of corticospinal terminal labeling, we injected 1.2 μl of FD in our final experimental F2P2 lesion case (SDM91). The craniotomy was closed as described previously (Morecraft et al., 2001, 2002, 2007a).

Tissue Processing and Immunohistochemical Procedures

Following the survival period after tract tracer injection, each monkey was deeply anesthetized with an overdose of pentobarbital (50 mg/kg or more) and perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde and sucrose as previously described (Morecraft et al., 2013). Following an appropriate period for cryoprotection, the cerebral cortex was frozen and cut in the coronal plane at a thickness of 50 μm in cycles of 10 and the spinal cord was cut horizontally at a thickness of 50 μm in cycles of 6. One series of cortical and spinal cord tissue sections was stained for Nissl substance for cytoarchitectural analysis using thionin (Morecraft et al., 1992, 2004, 2012, 2013). Subsequent series of tissue sections through the cortex and spinal cord were then processed using single and double label immunohistochemical procedures for visualization of the injected neural tracers as previously described (Morecraft et al., 2007a, 2013). To verify that the FD antibody and subsequent tissue labeling process resulted in staining only the injected and transported tract tracer, sections from the prefrontal cortex and occipital lobe were immunohistochemically processed and parts of these cortices that are not connected to M2 (Luppino et al., 1993; Morecraft etal., 2012) were examined for false FD labeling. Neuronal immunohistochemical labeling was not found in these control tissue sections demonstrating that false labeling was not present in the final tissue specimens used for analysis.

Stereological Analysis

The methods used to calculate unbiased estimated bouton numbers at specific spinal levels and within specific spinal cord laminae have been provided in detail in our previous papers (McNeal et al., 2010; Morecraft et al., 2007b, 2013). Immunoreactive terminal-like varicosities (i.e., putative boutons or terminal-like profiles) were defined as small swellings along the terminal fibers that were 0.5 – 3.5 um in diameter (Lawrence et al., 1985; Wouterlood and Groenewegen, 1985: Freese and Amaral, 2006; Morecraft et al., 2007b) (Fig. 2). Unbiased estimates of the total number of terminal boutons within Rexed’s laminae (and subdivisions) were determined using the Optical Fractionator (Microbrightfield, Colchester, VT, USA). Briefly, we calculated the average section thickness, overall fraction of tissue thickness that would be analyzed, the overall fraction of sectional area, and the overall number of tissue sections under analysis that contain the region of interest (ROI) (i.e., spinal cord laminae and respective subdivisions). Using the sectional area and the average tissue thickness we then constructed counting bricks and counted axon terminal boutons using unbiased counting rules (Larsen et al., 1998, West et al., 1991; West, 2012). The stereological parameters included the counting brick dimensions, tissue thickness, counting brick placement, guard zone and disector height. The same X/Y counting frame (109.2/71.4 μm) and X/Y grid placement (125.3/241.9 μm) was applied to all case material when performing stereology. To obtain an accurate estimate of the total number of labeled particles of interest (i.e., terminal boutons) in each individual monkey spinal cord, every other tissue section in a complete series of processed sections was used for microscopic stereological analysis and the total number of boutons within each ROI were expressed as total number counted per ROI per animal as previously described (Courtine et al., 2008; McNeal et al., 2010).

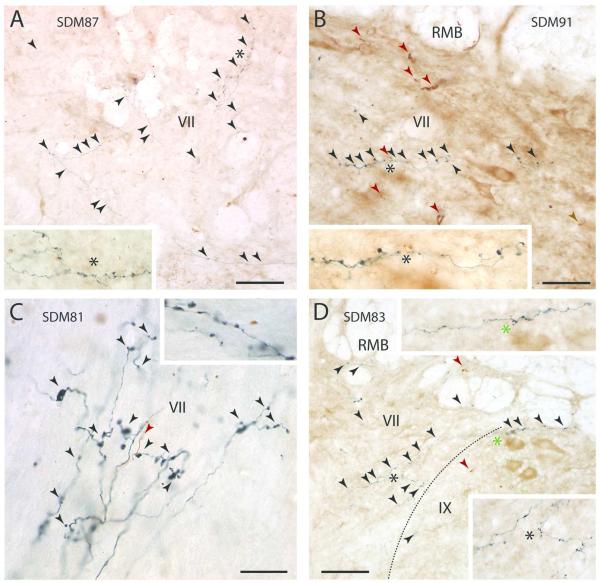

Figure 2.

Plate of high-power digital photomicrographs of immunohistochemically processed tissue sections through the spinal cord illustrating fluorescein dextran (FD) labeled terminal axon fibers and boutons (black arrowheads) in the gray matter contralateral to the FD injection site of F2P2 lesion cases SDM87 (A, spinal level C8), SDM91 (B, spinal level T1), SDM81 (C, spinal level T1) and SDM83 (D, spinal level C8). In panels A, B and D each inset is a higher power view of the field marked by the color matched asterisk. In panel C, the inset is an enlarged image of labeled terminals at superior levels of T1 whereas the main panel shows a field of labeled terminals at inferior levels of T1. In panels B, C and D, the red arrowheads indicate the locations of brown labeled fibers resulting from an injection of the tract tracer biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) that was placed into another spared cortical region of interest. The dotted line on paned D indicates the boundary between laminae VII and IX. Roman numerals represent Rexed’s laminae. Abbreviations: RMB, reticulated marginal border. Scale bar = 100 μm in A; 50 μm in B (also applies to D); 20 μm in C. Scale bars apply only to main panels in A-D.

To estimate terminal fiber length within these ROIs, we employed the Spaceballs probe. This probe was uniquely designed to satisfy isotropic requirements for tissue processing that may not be feasible. Specifically, because the probe is a virtual sphere, by definition all orientations on the surface of the sphere have an equal probability of being used (Mouton et al., 2002; West, 2012). To implement the probe, a computer software package (StereoInvestigator, Microbrightfield, Colchester VT, USA), allowed us to set the radius of the sphere and to maintain the same stereological parameters (i.e., area section fraction, series section fraction, section thickness) as the ones employed for the Optical Fractionator. The sphere was also designed to be less than the thickness of the tissue. The designed virtual sphere was then superimposed on the microscope image. At successive focal planes with a 100x oil immersion objective, labeled fibers that intersected the edge of the virtual sphere were counted for every sight within a given ROI. Estimates of terminal fiber length and associated coefficient of errors were then calculated according to previously derived formulas (Mouton et al, 2002; West, 2012)

The cortical ROIs to which stereology was applied included the FD tract tracer injection site and the extirpated lesion site (Tables 1, 2). Unbiased estimates of the total injection site volume (which included the core volume) and core injection site volume were determined using the Cavalieri probe in the same StereoInvestigator software. To accomplish this, every cortical tissue section spaced 500 μm apart through the injection site in the FD immunostained series of tissue sections was used for analysis. The same probe and method was used to determine the lesion site volume (gray and white matter) as reported in our previous papers (Pizzimenti et al., 2007, Darling et al., 2009). Briefly, after carefully evaluating the gray matter and white matter extent of the lesion site from Nissl stained sections through the lesioned hemisphere, the lesion site boundaries were superimposed onto gray and white matter regions on matching Nissl stained sections through the non-lesioned hemisphere (see Fig. 4 of Pizzimenti et al. , 2007, right column). The sections were spaced 500 μm apart then the Cavalieri probe was used to determine the respective volumes (Table 2).

Figure 4.

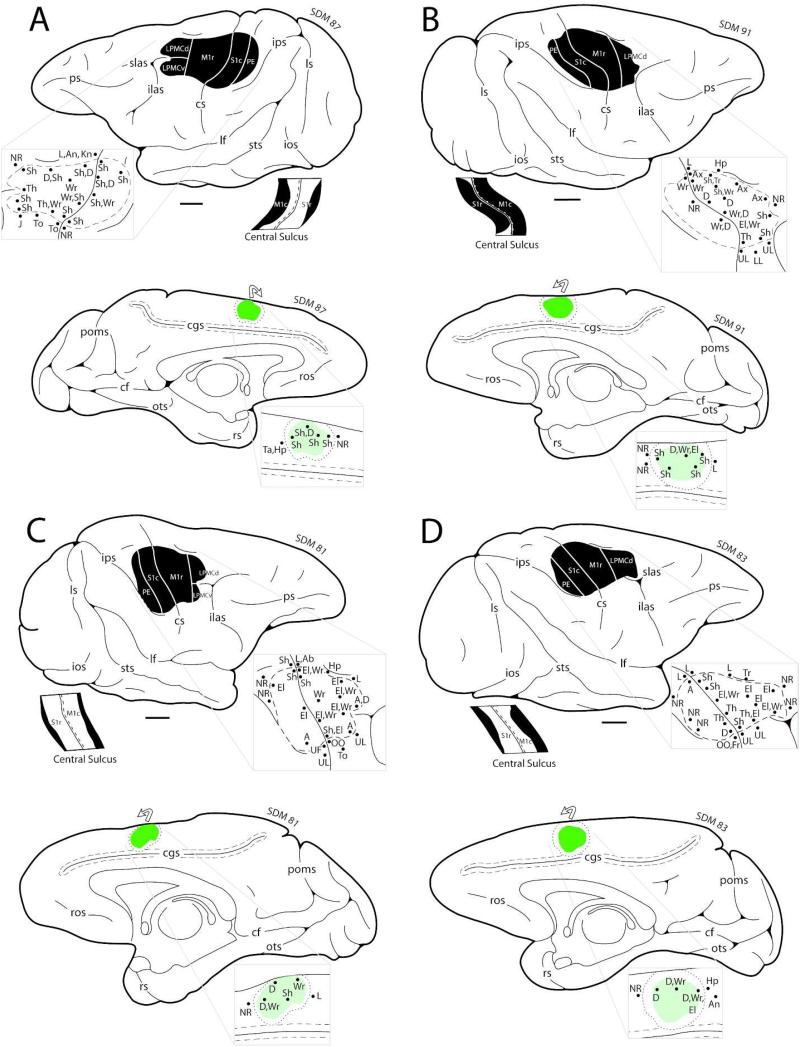

Line drawings of the lateral (top) and medial (bottom) surfaces of the cerebral cortex in F2P2 lesion cases SDM87 (A), SDM91 (B), SDM81 (C) and SDM83 (D) depicting the locations of the lesion site (blackened area on lateral surface) and core of the fluorescein dextran (FD) injection site (green irregular shape on the medial surface). On the medial wall the dotted line around the injection site core represents the external boundary of the injection site halo. The curved arrow above the injection site indicates that some of the injection site halo was present on the dorsal convexity. On the lateral surface, the pullout depicts the physiological map of movement representation obtained with intracortical microstimulation used to localize the arm representations of the primary motor cortex (M1), lateral premotor cortex (LPMC), and primary somatosensory cortex (S1) prior to neurosurgical resection of the gray matter forming these cortical regions. Below the occipital lobe on the lateral surface drawing, is a flattened map showing cortex lining the rostral and caudal banks of the central sulcus. The black region represents the lesion site that extended into the sulcal cortex. The pullout on the medial surface is the physiological map of movement representation obtained with intracortical microstimulation to localize the arm representation of M2 prior to injection of the tract tracer FD. Scale bar = 5 mm and applies to the lateral surface, medial surface and flattened map of the cortex lining the central sulcus. For abbreviations see list.

Statistical Analysis of Neuroanatomical Data

Statistical analyses were performed to determine if significant differences occurred in bouton numbers and terminal fiber lengths between the control and lesion animals. Specifically, separate mixed 2-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to compare these dependent variables in control versus lesioned animals across the spinal laminae (I-IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X and RMB for spinal segments C5-T1). We also used a mixed 3-way repeated measures ANOVA to compare bouton numbers within quadrants of lamina IX for segments C5-T1. In this case the repeated measures factors were: dorsal/ventral regions each subdivided into medial and lateral quadrants. Mauchley’s test was used to determine whether the assumption of sphericity was met when there were three or more levels in a repeated-measures factor (i.e., laminae). Adjustments in degrees of freedom for F-tests were made on the basis of the Huynh-Feldt epsilon values resulting in adjusted P-values, which are reported in the Results section. Statistical tests were accomplished using the GraphPad InStat 3 statistical software package (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) or Statistica software (Tulsa, OK).

Neuroanatomical Data Reconstruction and Presentation

Publication quality images of injection sites and labeled fibers were captured using a Spotflex 64 mega pixel camera, (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI, USA, version 4.6), mounted on an Olympus BX51 microscope. Photographic montages of the injection sites and labeled fibers were created using Adobe PhotoShop 7.0 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Only brightness and contrast were adjusted to maximize discrimination and normalize images for comparative purposes. Cortical reconstructions and reconstruction of the physiological stimulation maps were developed as previously described using metrically calibrated digital images of the cortical surface (Morecraft and Van Hoesen 1992, Morecraft et al., 2002, 2013). Publication quality line illustrations were created using Adobe Illustrator 10.0 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Movement Analysis Procedures

Two apparati were used to test fine hand/digit motor function: the modified movement assessment panel (mMAP) (Darling et al., 2006) and the modified dexterity board (mDB) (Pizzimenti et al., 2007) as previously described (McNeal et al., 2010). Forces applied during manipulation of the carrot chip in the mMAP task were recorded at 200 samples/s using Datapac 2k2 (Run Technologies). Movements of the hand during the mMAP task were recorded using a single digital video camera (Sony, model DCR-DVD301) to provide qualitative assessments of movement strategy and success/failure on each trial. Quantitative video recordings of hand movements during the mDB task from 4 cameras were used to assess spatial and temporal variables (e.g., accuracy and duration of the initial reach, grip aperture at touchdown).

Behavioral Procedures

Prior to an experimental session the monkey was food restricted for 12-24 hours. The initial training sessions used a “standard” rectangular dexterity board to assess the preferred hand of each monkey as described previously (Nudo et al., 1992). Hand preference was measured over 150 trials over a 3 day period (with 50 trials conducted each day). We recorded: 1) the hand used on the initial reach for that trial; 2) the hand used on subsequent reaches and; 3) the hand used to retrieve the pellet. A reach was defined when the animals hand passed through the plane of the square portal window located directly above the Kluver board. A subsequent reach was defined if the hand was withdrawn into the cage then extended back through the portal plane and over the Kluver board. The handedness index (HI) was computed as: (P-50)*2 where P is the average percentage of initial reaches and retrievals with the preferred hand (hand with the higher percentage of initial reaches and retrievals). HI ranges from 0 (50% of initial reaches and retrievals with each hand) to 100 (all initial reaches and retrievals with the preferred hand).

Training with the mMAP (Darling et al., 2006) and mDB (Pizzimenti et al., 2007) devices commenced after hand preference was determined. Full testing sessions with the mDB included 5 retrieval attempts for each of the wells (A-E) for both limbs proceeding from the easiest well (E) to the most difficult (A), for a total of 25 trials with each hand. During post-lesion tests, the more impaired hand (contralateral to the surgically induced lesion) was always tested first to ensure high motivation. Full testing sessions with the mMAP included blocks of 5 trials at each difficulty level with each hand, thereby giving the monkey 30 opportunities to retrieve carrot chips, 15 with each hand. During the first few post-lesion tests, the more impaired hand was tested first on the flat surface task (easiest task) to ensure high motivation. Thus, when considering both tests, a single testing session consisted of only 40 reaches for each hand.

Pre-lesion data were collected every 1-3 weeks for a total of 18-28 sessions according to each monkey’s ability to learn the task and perform consistently. The final five pre-lesion experiments demonstrated relatively stable levels of performance before lesions were made to cortical motor areas. Post-lesion data were collected from both limbs during weekly experimental sessions for the first two months after the surgery (i.e., one testing session per week). Thereafter, tests were conducted biweekly (i.e., one testing session every 2 weeks). After initial training, it was only during the pre- and post-lesion experimental sessions that the monkeys had exposure to the mMAP and mDB devices.

mMAP Data Analysis

Force data from the mMAP task were analyzed by visually identifying the first touch of the carrot chip or plate/rod supporting the carrot chip to the end of force application (i.e., when the carrot chip was removed from the plate supported by the load cell or the rod) on each trial using force recordings displayed in Datapac 2k2. The accompanying video data was also analyzed to verify these times and to identify trial outcome. The duration and total applied 3-dimensional absolute impulse were computed for each trial and, along with trial outcome used to compute a performance score. After pre-lesion data collection was completed, performance scores were computed and normalized to individual monkey’s abilities (i.e., maximum and minimum applied impulse and duration) for each trial at each difficulty level (McNeal et al. 2010).

mDB Data Analysis

Temporal characteristics of reaching, manipulation, and 3D locations of the tips of the index finger and thumb were determined from the digital video files as described previously and used to compute performance scores for reaching, manipulation and an overall score on each pre- and post-lesion trial (Pizzimenti et al., 2007). Measurements taken from video were used to compute reach duration, accuracy, grip aperture, manipulation duration and manipulation attempts (# of times contact between the pellet and a digit was lost and then re-established) on each trial. These measurements were each normalized to the performance ranges for each monkey prior to the lesion (i.e., to maximum/minimum reach and manipulation duration, least/most accurate reach, largest/smallest grip aperture, maximum/minimum number of manipulation attempts) and used to compute the performance scores (McNeal et al., 2010).

Analysis of Hand Motor Skill

We quantitatively assessed overall motor skill by computing mean divided by the standard deviation of manipulation performance scores over 5 consecutive testing sessions (i.e., 25 trials over an approximately 5 week period) (Pizzimenti et al. 2007; McNeal et al. 2010). These were computed for the performance scores on the mMAP curved rod task (which are computed from manipulation duration and forces exerted during manipulation) and for the manipulation scores on the mDB task (well with highest pre-lesion skill for each monkey). Note that higher mean performance scores (lower duration, impulse on mMAP; lower duration and fewer lost contacts with the food pellet in the mDB tasks) and lower variability of performances will result in higher skill values. Skill was computed for the best 5 consecutive and last 5 pre-lesion test sessions and for the 5 consecutive test sessions with the highest skill during post-lesion recovery. We also qualitatively analyzed each lesioned monkey’s contralesional hand/digit motions in the mDB and mMAP tasks to determine whether the monkey’s strategy changed post-lesion to use additional digits or different digits to perform the task.

Statistical Analysis of Motor Performance

We evaluated lesion effects on hand motor function from the duration (in weeks) from the time of the lesion until the first testing session with an attempt, successful acquisition and 5 successful acquisitions on the mMAP (flat surface task) and mDB (any well) tasks in each monkey. Recovery of fine motor skill was defined as the ratio of post-lesion skill (highest skill for 5 consecutive test sessions) to pre-lesion skill measured over the last 5 testing sessions before the lesion on the best well (well with highest pre-lesion skill) and 2nd smaller well (with pre-lesion skill of about 50% of that on the best well) of the mDB task and on the curved rod task of the mMAP. These measures of recovery were entered into single linear regression analyses to test whether recovery was correlated with the ratio of bouton numbers in individual lesioned monkeys to average number of boutons in control monkeys. Specifically, we considered the number of boutons in laminae VII and IX in lesioned monkeys, which we previously showed were highly correlated with recovery of skill in monkeys with lesions of M1 and lateral premotor cortex (LPMC) but without damage to parietal lobe (McNeal et al. 2010).

RESULTS

Microscopic analysis of the new control case (SDM84 – Fig. 3) and all F2P2 lesion cases (Figs. 1, 4) revealed that all FD injections were confined to the physiologically defined arm representation of M2 (cytoarchitectonic area 6m) and did not extend into the fundus and lower bank of the cingulate sulcus to involve the cingulate motor field. The core region of all injection sites was largely confined to the medial wall of the frontal cortex (Fig. 1) with the addition to the lip of the dorsal convexity which collectively is considered to be part of the supplementary motor cortex (Woolsey et al., 1952; Tanji and Kurata 1982, 1985). Importantly, all injection sites were found to involve cortical layer V which harbors the cells of origin of the CSP (Kuypers, 1981). The M2 corticospinal projection of the new control case (SDM84) was added to our previous control group of 4 control animals (Tables 1, 3-5). In SDM84, the general distribution of the contralateral terminal projection was similar to all other control cases with the highest number of labeled boutons being located in lamina VII and IX (Fig. 5; Table 3). The strongest projection to lamina IX in case SDM84 was localized to the dorsal lateral quadrant followed by the ventromedial quadrant (Table 5). The total number of estimated contralateral labeled boutons in case SDM84 was strikingly similar to case SDM54 (Table 3). Like the 4 previous control cases, the ipsilateral M2 corticospinal projection in case SDM84 terminated primarily in lamina VIII and the medial part of lamina VII (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Composite illustration showing the FD injection site (panels A and B) and terminal labeling in the spinal cord (panel C) in control case SDM84. A: Line drawing of the medial wall of the cerebral hemisphere depicting the location of the FD injection site core (green irregular shape) in the arm/hand representation of M2. The dotted line around the injection site represents the external boundary of the injection site halo. The curved arrow above the injection site indicates that some of the injection site halo was present on the dorsal convexity. The pullout depicts the physiological map of movement representation obtained with intracortical microstimulation used to localize the arm representation of M2 prior to injection of the tract tracer FD. B: A low-power digital photomicrograph of an immunohistochemically processed coronal tissue section through the fluorescein dextran (FD) injection site in the arm/hand region of M2. The dashed line on the injection site represents the external boundary of the injection site core and the dotted line the external boundary of the injection site halo. The blue arrow identifies a coalesced descending labeled fiber bundle emerging from the FD injection site. C: High-power digital photomicrographs of an immunohistochemically processed tissue section through spinal C7 illustrating FD labeled terminal axon fibers and boutons (black arrowheads) in contralateral laminae VII and IX. The blue arrows show fibers in passage. The inset is from the same tissue section but a different microscopic focal plane showing labeled boutons (black arrowheads) in lamina IX. Abbreviations: as, arcuate spur; cgs, cingulate sulcus. For other abbreviations see list. Scale bar = 2 mm in B, 50 μm in C.

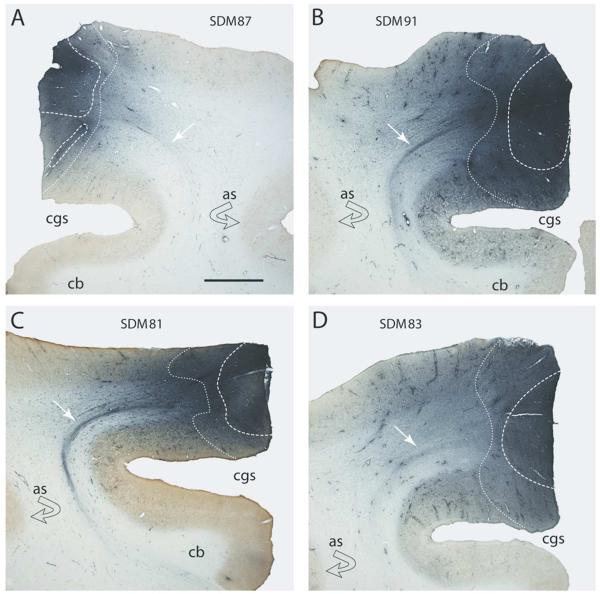

Figure 1.

Plate of low-power digital photomicrographs of immunohistochemically processed coronal tissue sections illustrating the fluorescein dextran (FD) injection site in the arm/hand region of M2 in F2P2 lesion cases SDM87 (A), SDM91 (B), SDM81 (C) and SDM83 (D). The dashed line represents the external boundary of the injection site core and the dotted line the external boundary of the injection site halo. The white arrows identify a coalesced descending labeled fiber bundle emerging from the FD injection site. The curved black arrow indicates the location of gray matter lining the depths of the arcuate spur. Abbreviations: as, spur of arcuate sulcus; cb, cingulum bundle; cgs, cingulate sulcus. The scale bar in A = 2mm and applies to all panels.

TABLE 3.

Contralateral Bouton Counts in Each Control Case by Spinal Lamina1

| Bouton | I-III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | # | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | RMB | Med | Lat | |||

| SDM41 | 64,075 | 0 | 21 (0.03) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 627 (1) |

2,006 (3) |

5,766 (9) |

5,515 (9) |

18,050 (28) |

21,811 (34) |

2,507 (4) |

7,521 (12) |

251 (0.4) |

| SDM62 | 73,706 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 612 (1) |

122 (0.2) |

2,326 (3) |

5,265 (7) |

12,856 (17) |

31,833 (43) |

490 (0.7) |

20,202 (27) |

0 0 |

| SDM54 | 85,130 | 0 | 12 (0.01) |

0 | 294 (0.3) |

0 | 784 (1) |

588 (1) |

5,485 (6) |

5,779 (7) |

21,255 (25) |

26,936 (32) |

9,011 (11) |

14,986 (18) |

0 0 |

| SDM77 | 80,504 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 375 (0.005) |

900 (1) |

7,428 (9) |

3,826 (5) |

8,703 (11) |

32,862 (41) |

22,884 (28) |

975 (1) |

2,401 (3) |

150 (0) |

| SDM84 | 86,829 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 88 (0.1) |

352 (0.4) |

1,676 (2) |

1,852 (2) |

32,566 (38) |

25,503 (29) |

13,415 (15) |

10,231 (12) |

1,146 (1) |

| MEAN | 78,048.8 | 0.0 | 6.6 | 0.0 | 58.8 | 75.0 | 602.2 | 2,099.2 | 3,815.8 | 5,422.8 | 23,517.8 | 25,793.4 | 5,279.6 | 11,068.2 | 309.4 |

Percentages of total label in parentheses. Values are rounded to the nearest whole number, except when the value is 0.7 or less. Lat, lateral; Med, medial; RMB, reticulated marginal border.

TABLE 5.

Contralateral Bouton Counts in Each Control Case Within Each Quadrant of Lamina IX 1

| Bouton | IX | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | # | DMED | DLAT | VMED | VLAT |

| SDM41 | 7,521 | 4,763 (63) |

2,758 (37) |

0 | 0 |

| SDM62 | 20,202 | 10,285 (51) |

6,367 (32) |

2,693 (13) |

857 (4) |

| SDM54 | 14,986 | 7,640 (51) |

4,604 (31) |

2,351 (16) |

391 (3) |

| SDM77 | 2,401 | 2,101 (88) |

300 (12) |

0 | 0 |

| SDM84 | 10,231 | 4,588 (45) |

1,940 (19) |

3,086 (30) |

617 (6) |

| MEAN | 11,068.2 | 5,875.4 | 3,193.8 | 2,032.5 | 466.3 |

Percentages of total label in parentheses. Values are rounded to the nearest whole number, except when the value is 0.7 or less. Lat, lateral; Med, medial; RMB, reticulated marginal border.

Figure 5.

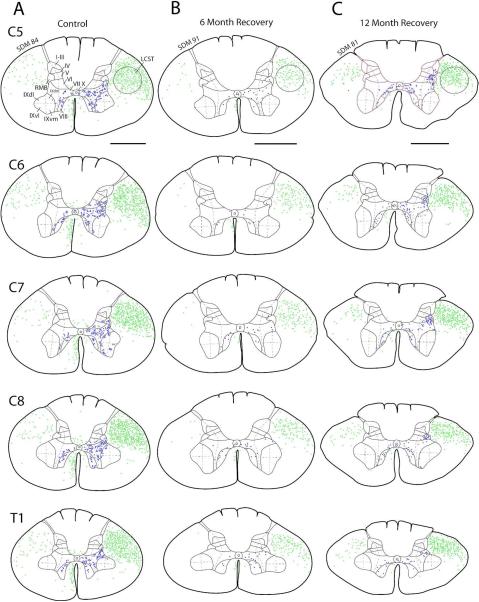

Line drawings depicting a representative transverse section through spinal levels C5 to T1 in case SDM84 (control) (A), SDM91 (6 month recovery) (B) and SDM81 (12 month recovery) (C) showing regions in the lateral corticospinal tract, posterior funiculus and anterior funiculus containing labeled axons (green dots) and regions of Rexed’s laminae containing labeled boutons and bouton clusters (blue dots). Roman numerals in section C5 designate Rexed’s laminae and apply to all spinal sections. Laminae I-VII were subdivided into medial and lateral halves (see dashed line) and lamina IX into quadrants (see dashed lines) for stereological analysis. Note the sparse terminal labeling in cases SDM91 and SDM81 denoted by the presence of significantly fewer blue dots located in the spinal gray matter compared to the robust terminal labeling in control case SDM84. For orientation dorsal is located on the top of each section and ventral at the bottom. Abbreviations: dm, dorsomedial; dl, dorsal lateral; LCST, lateral corticospinal tract; RMB, reticulated marginal border; vm, ventromedial; vl, ventrolateral). Scale bar = 2 mm.

TABLE 4.

Ipsilateral Bouton Counts in Each Control Case by Spinal Lamina1

| Bouton | I-III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | # | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | RMB | Med | Lat | |||

| SDM41 | 4,012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,257 (56) |

501 (12) |

1,254 (31) |

0 | 0 |

| SDM62 | 7,836 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,265 (67) |

734 (9) |

1,837 (23) |

0 | 0 |

| SDM54 | 53,187 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27,524 (52) |

2,547 (5) |

23,116 (43) |

0 | 0 |

| SDM77 | 5,552 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,101 (38) |

225 (4) |

3,076 (55) |

0 | 150 (3) |

| SDM84 | 31,942 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12,794 (15) |

1,411 (2) |

15,180 (17) |

1,764 (2) |

793 (1) |

| MEAN | 20,505.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9,988.2 | 1,083.6 | 8,892.6 | 352.8 | 188.6 |

Percentages of total label in parentheses. Values are rounded to the nearest whole number, except when the value is 0.7 or less. Lat, lateral; Med, medial; RMB, reticulated marginal border.

General Experimental Observations of the F2P2 Lesion Cases

Immediately after the F2P2 lesion, all animals showed clear impairment with flaccid paresis of the contralesional hand. Opposite the lesioned hemisphere, a pendulous hand hung limply at the side and was not used for postural support or grasping of objects. This paresis lasted for 7-10 days after the lesion when hand function began to be reinstated to assist the unimpaired hand during feeding and typical cage behaviors such as grasping of the cage bars and climbing. There was a clear tactile sensory impairment in all cases immediately after the lesion as the animals apparently did not notice when the affected hand and finger tips came into contact with the cage floor or cage walls. The sensory deficit was also evident when the animals attempted to pick up objects in the cage with the affected hand as they often groped at an object and did not successfully grasp the object until the animal visually attended to it. This behavior was also observed during the mDB and mMAP tasks when the animals had to pick up very small food items. The lesion volumes for each extirpated area are provided in Table 2. A detailed description of the lesion site in each experimental case is provided below.

Lesion Site Analysis

Lesion Site Analysis of SDM 87 (6 month recovery)

In the frontal lobe, the LPMC lesion involved the inferior part of LPMCd (area 6DC) and dorsal part of LPMCv (area 6Vd) of which all gray matter was removed with the exception of the rostral-most portion of the lesion site (1-2mm) which involved removal of only layers I-III. In this vicinity, the gray matter lining the depths of the arcuate spur was spared. The lesion spread caudally to involve all gray matter corresponding to the arm/hand region of M1r (or the gryal, or “old” part of area 4 – Rathelot and Strick, 2009) (Figs. 4, 6A; Table 2). In the anterior bank of the central sulcus extensive removal of M1c was noted, involving nearly one-half of the anterior bank (or “new” part of area 4-Rathelot and Strick, 2009) (Figs. 4, 6A; Table 2). In the posterior bank of the central sulcus the upper one-quarter of S1r was removed (Fig. 4). On the lateral parietal surface, all of the arm/hand region of S1c was ablated which extended posteriorly to involve the rostral part of area PE of the superior parietal lobule (Fig. 4).

Figure 6.

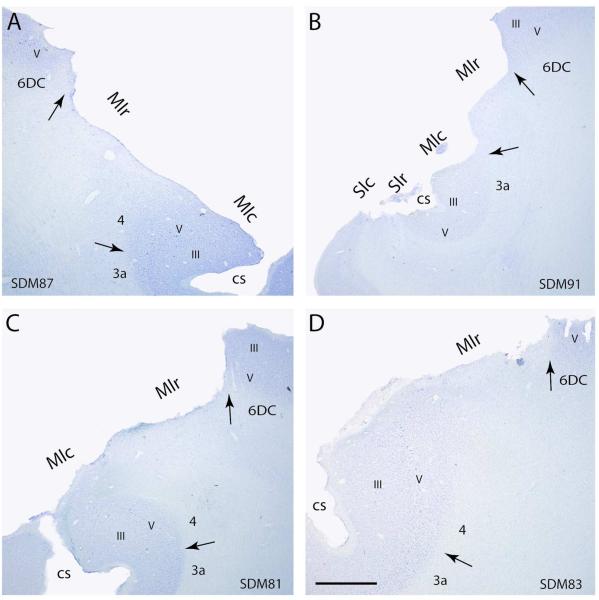

Panel of photomicrographs of representative Nissl stained sections through the lesioned hemisphere of F2P2 lesion cases SDM87 (A), SDM91 (B), SDM81 (C) and SDM83 (D). In all sections the black arrow marks the location of the cytoarchitectonic border between either area 4 (M1) and area 3a (S1) or area 4 and lateral premotor area 6DC. Cortical layers are identified using Roman numerals. The regions of extirpated cortex are identified by M1c, M1r, S1r and S1c. Note the extensive removal of M1c, M1r, S1c and Sr in case SDM91. Abbreviation: cs, central sulcus; M1c, caudal primary motor cortex; M1r, rostral primary motor cortex; S1c, caudal primary somatosensory cortex; S1r, rostral primary somatosensory cortex. Scale bar in D = 2 mm and applies to all other panels.

Overall, the subcortical white matter lesion was limited to the region immediately below the gray matter extirpation (Figs. 6A; Table 2). However, on the lateral surface in the central region of the frontal lobe resection, a small part of the lesion spread inferiorly forming a vacated v-shape that appeared to part the uppermost portions of the frontal occipital fasciculus (FOF) and superior longitudinal fasciculus II (SLFII) (nomenclature according to Schmahmann and Pandya 2006). Much of this subcortical lesion may have been a consequence of lost subcortical fiber pathway that originally emerged with the resected gray matter cortex. At its deepest level, the vacated cortex corresponded to the horizontal level containing the fundus of the cingulate sulcus.

Lesion site analysis of SDM 91 (6 month recovery)

On the lateral frontal surface the lesion involved the very caudal and inferior part of LPMCd (area 6DC). Posteriorly all cortex forming M1r was completely removed (Figs. 4, 6B; Table 2). In the anterior bank of the central sulcus all of M1c was extirpated (Figs. 4, 6B; Table 2). On the posterior bank of the central sulcus most of the gray matter forming S1r was removed except a very small part of S1r in the very depth of the fundus (Figs. 4, 6B). In the Nissl stained preparations this cortex was found to be disorganized, possibly by aspiration tip trauma during the extirpation process. The lesion extended posteriorly onto the gyral surface of the parietal lobe fully removing S1c and extending into the rostral part of area PE of the superior parietal lobule (Fig. 4).

Like case SDM87, white matter damage was found in the central region of the frontal lobe lesion on the lateral surface that spread inferiorly. This formed a vacated V-shape that appeared between the uppermost portions of the frontal occipital fasciculus (FOF) and superior longitudinal fasciculus II (SLFII) (Table 2). At its deepest level, the vacated cortex corresponded to the horizontal level containing the fundus of the cingulate sulcus.

Lesion site analysis of SDM 81 (12 month recovery)

On the lateral surface of the frontal lobe the lesion effectively removed nearly all of the rostral part of M1 (Figs. 4, 6C). For example, throughout the lesion site, there was no evidence of cellular layers I-VI with the exception of a very small region near the shoulder/leg border that only had layers I-III resected. The lateral frontal lesion extended rostrally to involve a small portion of the inferior-posterior part of dorsolateral premotor cortex (LPMCd) removing layers I-III. This part of the lesion corresponded to architectonic area 6DC. A small part of the posterior region of architectonic area 6V of the ventrolateral premotor cortex (LPMCv) was fully resected. The M1 lesion extended into the anterior bank of the central sulcus, involving only the dorsal most part of M1c (Table 2). Thus, a large portion of M1c was spared (Figs. 4, 6C). Likewise, in the caudal bank of the central sulcus, most of the cortex forming the rostral part of the arm/hand part of the primary somatosensory cortex (S1r, or areas 3 and 1) was spared with the exclusion of layers I-VI forming the dorsal part of area 1 which was fully resected (Fig. 4). From this location, the lesion extended posteriorly, effectively removing all layers (I-VI) of cortex forming the arm/hand part of caudal somatosensory cortex (S1c, or the gyral part of S1 corresponding to areas 1 and 2). The parietal lobe lesion extended into the superior parietal lobule removing layers I-VI of the rostral part of area PE (or area 5) (Fig. 4) and only layers I-III in the posterior tip (1.5mm) of the excised cortical region.

In both the frontal and parietal regions there was minimal white matter lesion damage that was confined to the location immediately below the extirpated gray matter (Fig. 6C; Table 2). There was no vacated region of white matter located below the gray matter resection as found in monkeys SDM87 and SDM91.

Lesion site analysis of SDM 83 (12 month recovery)

The rostral part of M1 (M1r), on the gyral surface, was completely removed (Figs. 4, 6D) and anterior to this cortex a small portion of LPMCd was ablated (i.e., layers I-VI were not found) (Fig. 4) with the exception of the anterior-most region (1 mm) of the extirpation where only layers I-III were removed. The M1r lesion extended into the anterior bank of the central sulcus, involving slightly more cortex on the anterior bank of the central sulcus (i.e., M1c) than case SDM81 (Fig. 4; Table 2). Like SDM81, much of the cortex lining the fundus of the sulcus was spared which extended onto the caudal bank of the central sulcus (Fig. 6D). However, slightly more cortex in the dorsal half of S1r was removed including all gray matter layers. From this location, the lesion extended posteriorly, effectively removing all layers (I-VI) of cortex forming the arm/hand part of S1c on the gyral convexity. The parietal lobe lesion extended very slightly into the superior parietal lobule removing layers I-VI of the rostral-most part of area PE (Fig. 4).

Like SDM 81, there was minimal white matter lesion damage that was confined to the location immediately below the excised gray matter (Fig. 6D; Table 2). There was also no evidence of a vacated region of white matter located below the gray matter resection as found in monkeys SDM87 and SDM91.

Summary of Lesion Site Analyses

In all monkeys our histological analysis showed that the cortical lesion was confined to the intended lateral frontal motor cortex, adjacent primary somatosensory cortex and rostral-most part of the superior parietal lobule. A significant component of gray matter on the cortical surface was removed in the ablation cases with differing amounts of cortex being extirpated along the banks lining the depths of the central sulcus. The amount of extirpated cortex lining the anterior part of the central sulcus gradually increased with SDM81 having the smallest percentage of extirpated M1c cortex (30%), cases SDM83 and SDM87 having approximately 50% of M1c removed, and SDM91 having all of M1c ablated (100%) (Table 2). Likewise, the smallest percentage of extirpated S1r cortex was in case SDM81 (20%) and the greatest amount in case SDM91 (80%) with intermediate levels of S1r removal occurring in cases SDM83 (34%) and SDM87 (24%) (Table 2). In all cases M1r and S1c were effectively removed with the exception of a small part of M1r near the shoulder/leg transition region dorsally in case SDM81. In all cases, there was minimal subcortical white matter involvement limited to the region immediately below the cortical extirpation and without subcortical gray matter involvement (i.e., basal ganglia and thalamus).

Neuroanatomical Observations of the F2P2 Lesion Cases versus the Controls

The corticospinal projection from the arm representation of M2 was examined in 4 F2P2 animals and the estimated numbers of labeled boutons for each case within each lamina are provided in Table 6 (contralateral projection) and Table 7 (ipsilateral projection). In the F2P2 lesion cases, the terminal bouton estimate for the M2 contralateral corticospinal projection to the 4 quadrants of lamina IX is provided in Table 8.

TABLE 6.

Contralateral Bouton Counts in Each F2P2 Lesion Case by Spinal Lamina1

| Bouton | I-III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | # | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | RMB | Med | Lat | |||

| SDM 81 | 62,240 | 0 | 1,097 (2) |

0 | 411 (1) |

0 | 1,851 (3) |

137 (0.2) |

2,606 (4) |

4,254 (7) |

21,758 (35) |

15,102 (24) |

9,404 (15) |

2,465 (4) |

3,155 (5) |

| SDM 83 | 64,157 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 394 (1) |

3,545 (6) |

1,902 (3) |

25,681 (40) |

21,739 (34) |

5,976 (9) |

3,279 (5) |

1,641 (3) |

| SDM 87 | 56,630 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 125 (0.2) |

2,641 (5) |

3,838 (7) |

3,901 (7) |

18,822 (33) |

14,602 (26) |

5,098 (9) |

6,096 (11) |

1,507 (3) |

| SDM 91 | 47,951 | 0 | 176 (0.4) |

0 | 620 (1) |

0 | 354 (1) |

88 (0.002) |

619 (1) |

2,126 (4) |

22,875 (48) |

8,330 (17) |

11,349 (24) |

795 (2) |

619 (1) |

| MEAN | 57,744.5 | 0 | 318.3 | 0.0 | 257.8 | 0 | 582.5 | 815.0 | 2,652.0 | 3,045.8 | 22,284.0 | 14,943.3 | 7,956.8 | 3,158.8 | 1,730.5 |

Percentages of total label in parentheses. Values are rounded to the nearest whole number, except when the value is 0.7 or less. Lat, lateral; Med, medial; RMB, reticulated marginal border.

TABLE 7.

Ipsilateral Bouton Counts in Each F2P2 Lesion Case by Spinal Lamina1

| Bouton | I-III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | # | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | Med | Lat | RMB | Med | Lat | |||

| SDM81 | 35,066 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16,196 (46) |

1,920 (5) |

13,796 (39) |

890 (3) |

2,264 (6) |

| SDM83 | 13,456 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,199 (31) |

393 (3) |

7,159 (53) |

197 (1) |

1,508 (11) |

| SDM87 | 11,693 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,834 (33) |

689 (6) |

5,539 (47) |

439 (4) |

1,192 (10) |

| SDM91 | 22,517 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9,662 (43) |

1,506 (7) |

10,552 (47) |

443 (2) |

354 (2) |

| MEAN | 20,683.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8,472.8 | 1,127.0 | 9,261.5 | 492.3 | 1,329.5 |

Percentages of total label in parentheses. Values are rounded to the nearest whole number, except when the value is 0.7 or less. Lat, lateral; Med, medial; RMB, reticulated marginal border.

TABLE 8.

Contralateral Bouton Counts in Each F2P2 Lesion Case within Each Quadrant of Lamina IX1

| Bouton | IX | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | # | DMED | DLAT | VMED | VLAT |

| SDM81 | 2,465 | 753 (31) |

273 (11) |

1,439 (58) |

0 |

| SDM83 | 3,279 | 721 (22) |

327 (10) |

2,034 (62) |

197 (6) |

| SDM87 | 6,096 | 2,200 (36) |

1,446 (24) |

1,760 (29) |

690 (11) |

| SDM91 | 795 | 531 (67) |

88 (11) |

176 (22) |

0 |

| MEAN | 3,158.8 | 1,051.3 | 533.5 | 1,352.3 | 221.8 |

Percentages of total label in parentheses. Values are rounded to the nearest whole number, except when the value is 0.7 or less. Lat, lateral; Med, medial; RMB, reticulated marginal border.

The F2P2 lesion cases averaged about 75% of the mean estimated number of boutons of control cases for the M2 CSP projection in the contralateral spinal gray matter of C5-T1. Two-way [group – lesion/control; region – dorsal horn (laminae I-IV), intermediate zone (laminae V-VII and RMB), ventral horn (laminae VIII-IX), lamina X] repeated measures ANOVA showed that the number of boutons was lower in F2P2 lesion subjects than in controls (Fig. 7, group main effect: F1,7 = 5.45, p = 0.052) and that the distribution of boutons among spinal regions was altered by the lesion (Fig. 7, group x region interaction effect: F3,21 = 5.03, p = 0.009). Specifically, there were fewer boutons in the intermediate zone in subjects with F2P2 lesions than in controls (Fig. 7B, p = 0.009 on post-hoc tests), but not in other regions (Fig. 7B, p > 0.05). Further statistical analysis of boutons within the intermediate zone laminae and RMB showed that only lamina VII had fewer boutons in F2P2 lesion monkeys than controls (Fig. 7 – F3,21 = 3.75, p = 0.063; p = 0.009 on post-hoc test for lamina VII, p > 0.98 for lamina V, VI and RMB). Analysis of lamina IX boutons by quadrants showed that the F2P2 lesion subjects had significantly fewer boutons only in the dorsal quadrants (Fig. 7C, group x quadrant interaction: F3,21 = 8.74, p = 0.005, p < 0.05 on post-hoc tests comparing specific quadrants of controls and lesion subjects). The neuroplastic response was limited to the contralateral pathway as the estimated numbers of labelled boutons in the ipsilateral M2 CSP was similar for lesion and control cases (Fig. 7D, F1,7 = 0.007, p = 0.937).

On average M2 fiber lengths in the contralateral lateral corticospinal tract at C5 and C8 were longer in controls than subjects with F2P2 lesions but there were no significant differences between the two groups (F1,7 = 1.25, p = 0.3) and no group by segmental level (C5, C8) interaction effect (F1,7 = 0.16, p = 0.7). In contrast, the lesion cases had shorter M2 terminal fiber lengths than controls in contralateral spinal gray matter. Specifically, within the spinal gray matter at segmental levels C5 and C8, the distribution of M2 terminal fiber lengths within the medial and lateral regions of lamina VII and the dorsal regions of lamina IX differed between F2P2 lesioned monkeys and controls (group x segment x lamina region effects: F3,21 = 7.61, p = 0.001). Post-hoc tests showed that these differences were confined to the lateral and medial regions of lamina VII at C5 in which F2P2 lesioned monkeys had shorter fiber lengths than controls (p < 0.05). Fiber lengths were similar for lamina VII medial and lateral regions at C8 and for lamina IX dorsolateral and dorsomedial regions at C5 and C8 (p > 0.93).

Correlation of Neuroanatomical and Behavioral Observations

There were varying levels of recovery of reaching and grasp/manipulation of the food targets on the mDB and mMAP tasks among the four lesion cases. Three cases (SDM81, 83, 87) showed good recovery of performance scores (Fig. 8A,B) and post-lesion/pre-lesion manipulation skill ratios (Fig. 9A,B – manipulation skill ratios between about 0.4 and 1.2) in the mDB and mMAP tasks (e.g., Figs. 8,9), comparable to recovery of manipulation skill we have reported previously for most monkeys with M1 + LPMC lesions (Darling et al. 2009). However, one case (SDM91) showed very poor recovery. Specifically, SDM91 had 5 successful acquisitions in a single post-lesion test for only well E of the mDB task (actually a shallow dimple in the Plexiglas plate to hold the pellet) and never on the easiest mMAP task (grasping a carrot chip from a flat surface). There were also some successful post-lesion acquisitions of the small food pellet used in the mDB task wells from wells B, C, D and of the carrot chip in the mMAP flat surface task, but not in the mMAP straight rod or curved rod tasks. Thus, some recovery clearly occurred, but learned nonuse developed in SDM91 beginning after the 8th post-lesion week as there were no further attempts to retrieve the food targets with the contralesional hand on the mDB or mMAP tasks (e.g., Fig. 8B).

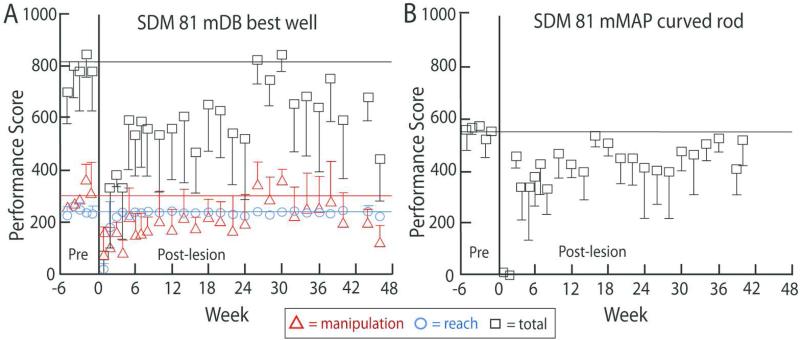

Figure 8.

A shows mean pre- and post-lesion total (black), reach (blue) and manipulation (red) performance scores (+/− 1 SD) for the mDB best well task by Case SDM81. Note that reach performance scores recovered rapidly to mean pre-lesion levels (indicated by the blue horizontal line) whereas total (black) and manipulation (red) performance scores remained lower than mean pre-lesion levels on most tests and were also more variable. B shows mean pre- and post-lesion performance scores in the mMAP curved rod task by SDM81.

Figure 9.

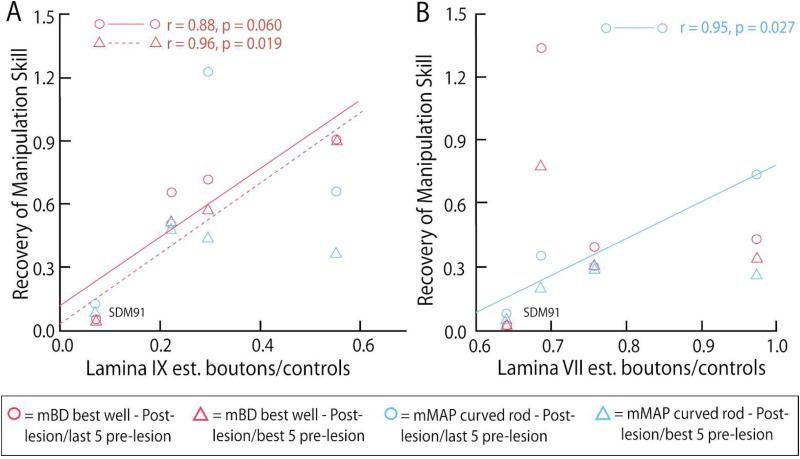

A and B show relationships between recovery of manipulation skill (ratio of best post-lesion skill ratio to skill of last 5 pre-lesion tests and to best 5 consecutive pre-lesion tests) in the mDB best well and mMAP (curved rod) tasks and the ratio of lamina IX and lamina VII boutons of C5-T1 for each lesion monkey to the mean of controls. Note that recovery of skill data for SDM91 are indicated as the plotted points on the bottom left (i.e., poorest recovery) in A and B. Linear correlation coefficients for statistically significant relationships between recovery of skill and numbers of laminae VII and IX boutons are also shown.

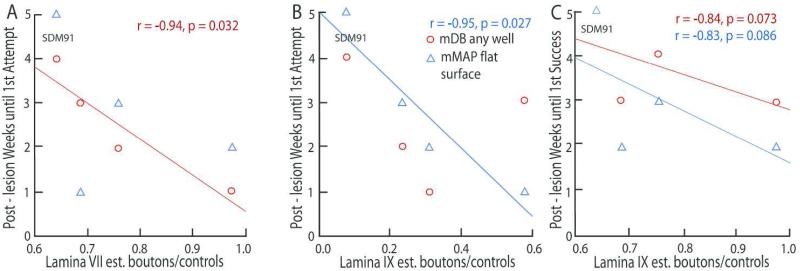

There was evidence that the post-lesion duration until behavioral attempts and successes were made, correlated with the remaining numbers of boutons from M2 in laminae containing interneurons and motor neurons. Specifically there were significant negative correlations of the ratios of lamina VII and IX boutons in lesion cases to average numbers of boutons in controls with post-lesion duration to first attempt and first success in the mDB and/or the easiest mMAP (flat surface) tasks. In the mDB task the post-lesion duration until the 1st attempt on any well was strongly negatively correlated with the lamina VII bouton ratio (Fig. 10A, r = −0.94, p = 0.032). In the easiest (flat surface) mMAP task there was a significant negative correlation of the lamina IX bouton ratio with post-lesion duration until first attempt (Fig. 10B, r = −0.95, p = 0.027) and also evidence of a correlation with post-lesion duration until the 1st success on this task (Fig. 10C, r = −0.83, p = 0.086).

Figure 10.

Scattergraphs showing post-lesion duration in weeks until 1st attempt (A,B) and 1 success (C) in the mDB (any well) and mMAP (flat surface) tasks versus estimated number of labeled boutons in individual cases with F2P2 lesions relative to mean number of labeled boutons in control cases in lamina VII (A) or lamina IX (B,C) of C5-T1. Each plotted point is data from a single case with a F2P2 lesion. Note the data for SDM91 (longest duration until first attempt and success) are indicated in the top left of each graph. Linear correlation coefficients for statistically significant relationships between post-lesion duration until first attempt and success in the mDB and mMAP tasks and numbers of laminae VII and IX boutons are also shown.

Recovery of fine motor function varied substantially among the 4 lesion cases and was also closely related to the number of M2 CSP boutons remaining in laminae VII and IX in individual lesion cases. The ratio of the number of labeled lamina IX boutons in lesion cases to the average number of labeled lamina IX boutons in controls was highly positively correlated with post-lesion recovery of manipulation skill (measured as the ratio of post-lesion skill to skill of the last 5 pre-lesion tests and skill of the best 5 consecutive pre-lesion tests (Fig. 9A, r = 0.88, 0.99 respectively, p < 0.003). Similarly, recovery of manipulation skill in the mMAP curved rod task was positively correlated with the ratio of labeled boutons in lamina VII of lesion cases to the average number of labeled lamina VII boutons in controls (Fig. 9B, r = 0.95, p = 0.027).

DISCUSSION

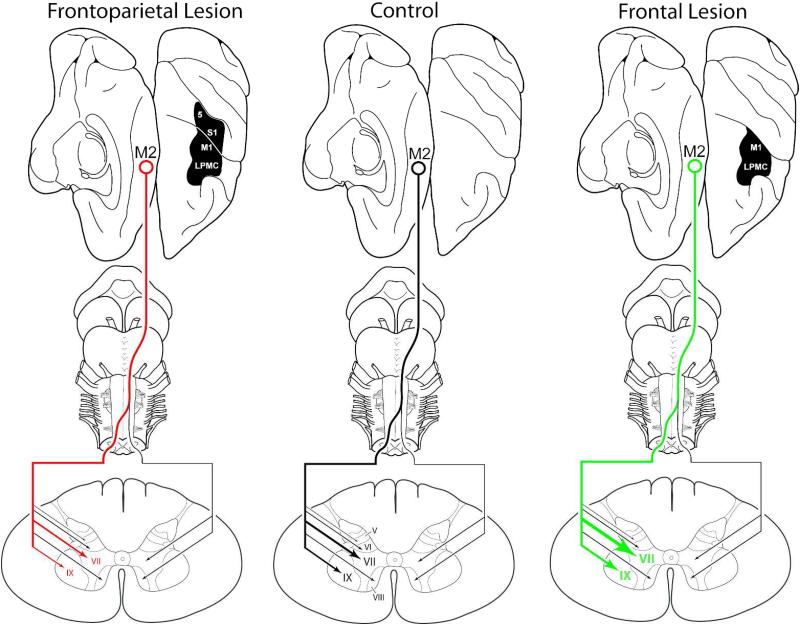

Lateral frontoparietal damage is common following stroke due to the fact that the middle cerebral artery (MCA) supplies this part of the cortical mantle (Tatu et al., 1998) and is the most commonly affected vessel in stroke (e.g., Ameriso and Sahai, 1997; Castillo and Bogousslavsky, 1997; Pessin, 1997; Carrera et al., 2007; González Delgado and Bogousslavsky, 2012). Our findings reveal that the collective loss of the lateral frontal somatomotor cortex and lateral parietal somatosensory cortex (F2P2 lesion) not only impedes a favorable compensatory neuroplastic response from the spared M2 corticospinal projection, but results in a substantial loss of M2 corticospinal terminal boutons and terminal fibers when compared to controls (Fig. 11). This response is in striking contrast to our previous findings following isolated lateral frontal somatomotor cortex injury (F2 lesion) showing that the corticospinal projection from M2 substantially increases in terms of the number of terminal boutons and terminal fiber lengths in laminae VII and IX at spinal levels C5 to T1 compared to controls (Fig. 11) (McNeal et al., 2010). We did not find any statistical differences between corticospinal fiber lengths in the lateral corticospinal tract (LCST) in the F2P2 lesion cases versus the controls. This suggests that the breakdown of the intact M2 corticospinal pathway occurred at the putative synaptic level within the confines of the spinal gray matter, at least with respect to the parameters investigated in our study, and this condition persists 6 to 12 months after lateral frontoparietal injury. What our data does not reveal is whether this long-term loss of corticospinal input represents a gradual decline, or conversly, a gradual recovery of input following a potentially massive loss of M2 corticospinal input in the acute and subacute phases following lateral frontoparietal injury. Indeed, application of the current experimental design on cases terminated at earlier post-injury time intervals (1 and 3 months after injury) will be required to address these important issues.

Figure 11.

Model of the effects of lateral cortical lesions on M2 CSP to spinal cord laminae of C5-T1 in controls and monkeys with F2P2 lesions and F2 lesions. In the present study we found substantial reductions in the total number of terminal labeled boutons of the supplementary motor cortex (M2) corticospinal projection (CSP) in lamina VII and IX at spinal levels C5 to T1 following removal of the arm/hand region of the lateral frontal somatomotor cortex (M1 + LPMC) and removal of the arm/hand region of the lateral parietal somatosensory cortex (S1 + rostral part of area 5/PE) (far left – F2P2 lesion) compared to controls (middle of figure). In our previous study, we found that isolated removal of the arm/hand region of the lateral frontal somatomotor cortex (M1 + LPMC) alone (far right - F2 lesion) results in substantial increases in contralateral terminal labeling of the M2 CSP in laminae VII and IX compared to controls (McNeal et al., Journal of Comparative Neurology 518:586-621, 2010). Thus, we demonstrate in the present study that the added effect of adjacent parietal cortex injury to the frontal motor lesion not only impedes a favorable compensatory neuroplastic response, but results in a substantial loss of M2 CSP terminal boutons. Clinically, our findings suggest that localized lateral peri-Rolandic cortical injury in stroke patients, which is very common, may undermine the structural and functional integrity of intact corticospinal projections located at remote sites from the lesion site. (Note: The relative intensity of the projection to spinal cord laminae is indicated by line thickness and arrow size. Denser terminal projections are represented by increased line thickness and arrow head size. Progressively lighter terminal projections are indicated by progressively thinner lines and arrowheads).

Effects of Sensory Denervation/Deprivation on Motor System Output

It is well beyond the scope of this research article to summarize the literature concerning the effects of sensory denervation on movement. However, some discussion is appropriate in the context of our experimental findings following partial destruction of S1. It has long been noted in non-human primates that section of the dorsal roots which subserve upper limb sensory impulses has devastating effects on motor function of the upper limb. Mott and Sherrington (1895) found that sectioning the dorsal roots in monkeys produced more severe and lasting paralysis than motor cortex resection. Similarly, more recent studies in monkeys have shown cervical dorsal rhizotomy that completely abolishes afferents to a subset of the digits is associated with poor recovery of grasping such that only digits that were incompletely deafferented were used to grasp objects (Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005; Darian-Smith, 2009). Interestingly, after sectioning of dorsal roots with receptive fields on the first three digits, recovery on a grasp retrieval task was accompanied by M1 corticospinal sprouting in the dorsal horn indicating an adaptive and possibly supportive role for spared M1 corticospinal projections in the recovery process (Darian-Smith, et al., 2013). However, the S1 corticospinal projection retracted which is similar to the reduction of spared M2 corticospinal projections observed in the present study following lateral frontoparietal injury. Taken together, the findings of Darian-Smith and colleagues indicate the loss of peripheral sensory afferent input to S1 as a result of dorsal rhizotomy results in a retraction of the S1 CSP in the affected dorsal horn and increase in the M1 CSP in the affected dorsal horn. However, it is unclear whether this sensory deprivation results in a decrease in the M1 CSP in the intermediate and anterior spinal gray matter regions as would be predicted by our findings.

Dorsal column injury, which disrupts the delivery of tactile and proprioceptive sensation information to S1 has devastating effects on fractionated finger movements (i.e., Beck, 1976; Eidelberg et al., 1976; Vierck, 1978; Cooper et al., 1993). Most of the investigative work examining the CNS adaptations that accompany dorsal column lesions have focused on adaptive reorganization at the level of the cuneate nucleus, sensory thalamus and primary somatosensory cortex (for review see Qi et al., 2014). Much like dorsal root lesions, reactivation and reorganization of S1 that correlates with behavioral motor recovery appears to depend on preserved subcomponents of the ascending sensory pathways. Some recovery may occur following complete dorsal column lesions through preserved ascending second order neuron axons arising from the dorsal horn neurons, and spared ascending sensory fibers that travel in the anterior and lateral funiculi (see Qi et al., 2014 for review). Notably, recovery of manual dexterity has been correlated with reactivation of lost components of the ascending somatosensory relay nuclei through local sprouting mechanisms from intact sensory fiber systems, including at the level of S1. It seems logical to assume that the immediate deficits in manual dexterity may be primarily due to the loss of somatosensory input to guide appropriate motor output, but it remains unclear if this condition has an acute or long-term detrimental effect on what appears to be an otherwise intact frontal motor neural network. Indeed, since the literature indicates that fractionated movements appear to be highly susceptible to impairments after dorsal column lesions, it is possible that this sensory loss may have a negative impact on intact corticospinal projections from the frontal cortex to lamina IX which contains motoneurons innervating the distal upper extremity musculature. Supporting this possibility is recent work showing that increased current levels are required to evoke movements from M1 following long-term dorsal column lesions (Kambi et al., 2011).