Abstract

Prion disease is a unique category of illness, affecting both animals and humans, in which the underlying pathogenesis is related to a conformational change of a normal, self-protein called PrPC (C for cellular) to a pathological and infectious conformer known as PrPSc (Sc for scrapie). Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), a prion disease believed to have arisen from feeding cattle with prion contaminated meat and bone meal products, crossed the species barrier to infect humans. Chronic wasting disease (CWD) infects large numbers of deer and elk, with the potential to infect humans. Currently no prionosis has an effective treatment. Previously, we have demonstrated we could prevent transmission of prions in a proportion of susceptible mice with a mucosal vaccine. In the current study, white-tailed deer were orally inoculated with attenuated Salmonella expressing PrP, while control deer were orally inoculated with vehicle attenuated Salmonella. Once a mucosal response was established, the vaccinated animals were boosted orally and locally by application of polymerized recombinant PrP onto the tonsils and rectal mucosa. The vaccinated and control animals were then challenged orally with CWD-infected brain homogenate. Three years post CWD oral challenge all control deer developed clinical CWD (median survival 602 days), while among the vaccinated there was a significant prolongation of the incubation period (median survival 909 days; p=0.012 by Weibull regression analysis) and one deer has remained CWD free both clinically and by RAMALT and tonsil biopsies. This negative vaccinate has the highest titers of IgA in saliva and systemic IgG against PrP. Western blots showed that immunoglobulins from this vaccinate react to PrPCWD. We document the first partially successful vaccination for a prion disease in a species naturally at risk.

Keywords: Prion protein, Immunization, Salmonella vaccine strain, Bovine spongiform encephalopathy, Chronic wasting disease, White-tailed deer, mucosal vaccination

Introduction

Prion disease is a unique category of illness, affecting both animals and humans, in which the underlying pathogenesis is related to a conformational change of a normal, self-protein called PrPC (C for cellular) to a pathological and infectious conformer known as PrPSc (Sc for scrapie) [1]. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), a prion disease believed to have arisen from feeding cattle with prion contaminated meat and bone meal products, crossed the species barrier to infect humans [2]. In North America an emerging prion infection, chronic wasting disease (CWD), represents a significant threat to human populations. CWD appears to be the most infectious prionoses to date, affecting free-ranging and farmed ungulates (white-tailed deer, mule deer, elk, reindeer and moose) [3–5]. CWD was first described in 1967 and recognized to be a prion disease in 1979 [3;6;7]. The prevalence of CWD has grown very rapidly and it has now been detected in 22 states of the United States, two Canadian provinces and in South Korea [4;8]. It has been reported that prion infection rates can be as high as 100% in captive cervid herds and 50% in some free-range native cervid populations. Transmission of CWD is mainly horizontal via a mucosal/oral route [8–10]. Aerosol transmission of CWD has also been documented in deer [11]. CWD is transmissible to non-human primates (squirrel monkeys)[12;13]. This highlights the need to have a means to prevent the spread of CWD.

A potential means to prevent some prion infections is by mucosal immunization [14], since the alimentary tract is the major route of entry for prion diseases such as CWD, BSE and vCJD [9]. We reported the first successful use of mucosal vaccination in prion infection using a Salmonella delivery system [15]. Live attenuated strains of Salmonella enterica have been used for many years as mucosal vaccines against salmonellosis and as delivery systems for the construction of multivalent vaccines with broad applications in human and veterinary medicine [16]. These bacterial vectors are genetically altered by multiple deletions and therefore unable to revert to a pathological state. In our case, the Salmonella enterica used is a strain corresponding to serovar Typhimurium (strain LVR01) attenuated by deleting part of the aroC gene that encodes for chorismate synthase, an enzyme essential for the synthesis of aromatic amino acids. The deletion produces a strain that can reach lymphoid follicles in the gut of many animals, delivering antigens, without any associated virulence [17].

In the current study, we tested the use of mucosal immunization in white-tailed deer. We document the first partially successful vaccination for a prion disease in a species naturally at risk.

Methods

Construction of a recombinant Salmonella vaccine strain expressing tandem copies of mouse or cervid PrP

The construction and production of the S.Typhimurium LVR01 expressing tandem copies of mouse PrP was as previously described [15;17;18]. Our prior studies have shown that the construct with two tandem copies of PrP produces higher levels of PrP (compared to a single copy) and that the conformation of the PrP with tandem copies is more appropriate [15;18]. Expression of higher copy numbers of PrP is not possible as it makes the Salmonella construct unstable. For construction of S.Typhimurium LVR01 expressing cervid PrP, the cervid PrP gene was PCR-amplified from plasmid p-DNR-1 using primers especially designed, tailored with EcoRI and XhoI recognition sites to allow directional cloning into pGEX-4T-1 to obtain pGEX-elkPrP. In this vector, the cloned gene is expressed as a fusion protein with the 26 kDa glutathione S-transferase (GST) in its N-terminal end. The GST gene is under control of the Ptac promoter and lacI repressor, and expression is induced by isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The GST-elkPrP fusion fragment was then amplified from pGEX-cervid PrP with primers tailored with BglII and HindIII in order to allow directional cloning into pTECH2 by replacing Frag C gene [19]. In this new construct the GST-cervid PrP fusion protein is expressed under the control of the in vivo inducible nirB promoter. The plasmid construct was then introduced into Salmonella LVR01 by electroporation. Expression of the GST-cervid PrP fusion protein by LVR01 strain was assessed by Western blotting using anti-PrP 7D9 and 6D11 monoclonal antibodies. The bacteria were cultured overnight on Luria-agar plates at 37°C. The vaccine strain was harvested from plates by re-suspension in 10ml of Luria broth-25 μg/L ampicillin (LB-amp), grew for 6 hours at 37°C then transferred to bigger batches of LB-amp and cultured overnight at 37°C with continuous shaking. The following day IPTG was added 1.2 ml/L and the induced expressing Salmonella were incubated for 4 more hours at 37°C with agitation. The bacterial suspension was centrifuged at 1,200xg for 20 min at 15°C, washed once with sterile saline, centrifuged again and dilute to 1x1011 colony forming units/ml. The cervid PrP produced by Salmonella LVR01, with a viability of >97%, was tested for sensitivity to proteinase K digestion, using methods previously described [18;20].

Animal and Vaccination Protocols

CWD-naïve, hand-raised, human and indoor-adapted white-tailed deer source were raised to weaning age at the University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry and surface transported to the CWD Research Facility on the Foothills campus of Colorado State University without touching the ground in CO. Five white-tailed deer were randomly allocated to the vaccine group, while 6 deer were allotted to the vehicle control group. The deer were assigned to isolation rooms and extreme protocols and precautions were taken to prevent environmental exposure of deer in the facility to CWD and to exclude transmission of prions from one room of the facility to another. Control animals were housed in the same facility. Two deer with a Prnp polymorphism of G/S at codon 96 were included in each group. This is the only known (~26%) white-tailed deer polymorphism that confers partial resistance to CWD infection (prolongs survival but does not prevent infection) [21;22]. There are 4 other polymorphic sites in the white-tailed deer Prnp gene which may affect CWD incubation, which are codon 95 (Q/H), 2%; codon 116 (G/S), 13%; codon 226 (Q/K), 0.5% and 138N pseudogene, 15%. [21;22]. The vaccinated and control deer were matched for these other polymorphic sites.

The deer were orally immunized via gavage with S.Typhimurium LVR01 expressing single copy of the GST cervid PrP fusion and on some vaccinations also with Salmonella expressing two tandem copies of mouse PrP (mPrPx2). A control group of 6 deer were orally immunized with S.Typhimurium LVR01 expressing GST without the PrP fusion. Immunizations were conducted over a period of 11 months, with a total of 8 immunizations (see graphical abstract). Deer were orally exposed to vaccine Salmonella or vehicle Salmonella consisting of ~1010 viable cells of the vaccine strain in 0.36M NaHCO3, pH 8.3 in a 5 ml volume mixed in a 6:1 ratio with alum ([Al(OH)3], Alhydrogel, Superfos Biosector, Denmark) by gavage delivered via stomach tube into the esophagus under ketamine/meditomidine anesthesia, adapted from the method previously used in mice [15]. Once the animal had swallowed the Salmonella into the rumen, 50mL of saline was delivered via the same stomach tube to prevent contamination of the Salmonella to the pharynx or trachea. Deer were held without access to food for 12 hours prior to vaccination and 2 hours following vaccination. The oral vaccinations were repeated weekly for 3 further inoculations. On the 3rd and 4th vaccination the Salmonella dosage was divided 9:1 between the rumen, and tonsils. The tonsils were “painted” with the inoculum using a small syringe fitted with narrow tubing. Extreme caution was taken to ensure all the inoculum was delivered mucosally, without any contamination by the systemic route. Three months after the original vaccination the deer were further vaccinated with an equal mix of Salmonella (~105 viable cells each) expressing cervid PrP or two tandem copies of mouse PrP (used to reinforce breaking tolerance to PrP). After the mucosal anti-PrP response was established in the PrP immunized group, the Salmonella-expressing PrP or vehicle Salmonella were applied to the rumen, tonsil and rectum. Three additional vaccinations were done 5, 9 and 11 months following the original vaccination. These last 3 vaccinations were supplemented with 100 μg of PK sensitive, polymerized cervid recombinant PrP (provided by DB) also applied to the rumen, tonsil and rectum. The polymerization of the recombinant PrP using glutaraldehyde was done as previously reported [20;23]. Deer were bled prior to the first vaccination (T0), and following the times of vaccination, with T7 being collected prior to oral challenge of all the deer with the CWD agent (on day 323 following the original Salmonella vaccination). In addition to collecting blood, saliva and feces were collected from deer to monitor the saliva and gut IgA levels. The saliva was collected with a 5ml syringe placed on the side of the mouth, while the deer were sedated. The saliva was placed in a tube with 3mL of 0.1M PBS with 0.2% SDS and 1mM PMSF to inhibit proteases. The saliva samples were centrifuged at 5,000xg for 10 minutes and the supernatants stored at −80°C until assay for anti-PrP IgA. The feces was collected directly from the rectum, stored in a pvc/nylon bag, and held at 4°C before being homogenized in PBS pH 7.2, 0.25% SDS/1mM PMSF, centrifuged at 14,000xg for 20 minutes, as described previously [18]. Supernatants were stored at −80°C until tested for anti-PrP IgA.

The CWD oral inoculum used consisted of brain homogenate from a CWD prion infected white-tailed deer, prepared as previously described, which resulted in 100% infection rates in previous trials and contained a mixture of strains CWD1 and CWD2 [24;25].

Following CWD challenge the deer were monitored daily for signs of CWD infection, using established protocols [11;26]. At 3-month intervals, biopsies, under ketamine/meditomidine anesthesia, were performed of the tonsils and recto-anal mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (RAMALT) to assess for the presence of PrPCWD by immunohistochemistry. Deer with clinical signs of CWD were anesthetized with 5–8 mg/kg ketamine and 0.1–0.2 mg/kg medetomidine HCl (IM), and thereafter euthanized with 88 mg/kg Beuthanasia-D Special solution (IV), followed by harvesting of brain and lymphoid tissues.

Antibody Levels

IgG, IgM and IgA serum antibody levels to recombinant cervid PrP were determined by a 1:125 dilution of plasma in duplicate, in which 50 μl/well of 1.5 μg/ml cervid recPrP in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 9.6 was coated at 4°C overnight onto Immulon 2HB 96 well microtiter plates (Thermo Scientific). Bound antibodies were detected by a goat anti-deer IgG, linked to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) and rabbit anti-goat or anti sheep IgM or IgA linked to HRP (Bethyl Lab. Inc., Montgomery, TX ). The color was developed by 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Pierce Biotech. Inc., Rockford, IL) as substrate; the reaction was stopped by 2N sulfuric acid and the plates read at 450nm in an ELISA reader. No commercially available anti-deer IgA or IgM exists; thus, both anti-goat and anti-sheep were used because they gave the best cross-reactivity with cervid Ig. Saliva samples were tested at 1:20 for IgM and IgA using a similar ELISA.

In the feces supernatant extract, IgA levels to recPrP were determined in a 1:30 dilution of the extract in PBST, using the above protocol.

Tissue Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin or paraformaldehyde/lysine/ periodate (PLP) for 5 days or 2 days respectively and stored in 60% ethanol. Immunostaining for PrPCWD was performed as published previously [27].

Western Blotting

Tissue homogenates were prepared from the post-mortem CWD-challenged deer brains at 10% (w/v) in NP-40 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.5, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) in a FastPrep FP120 cell disrupter (Qbiogene) with one 45 second cycle at a speed setting of 6.5, then cooled on ice. Western blots to detect PrPCWD were performed as previously published [28].

Western blots testing deer plasma, saliva and feces extracted IgG, IgM and IgA against S.Typhimurium LVR01 lysates, CWD homogenates and recombinant PrP were conducted using methods as previously published [15;18;20].

Data Analysis

The Kaplan and Meier survival curves of the vaccinated and control animals were plotted. The difference in the incubation period of CWD of two groups was tested using Weibull regression analysis (SAS Analytics Pro, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The anti-PrP IgA, IgM and IgG level results were analyzed by two-tailed student’s t-tests comparing vaccinated to vehicle controls levels at equivalent time points. (GraphPad Prism, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Ethics Statement

All animal use and procedures in this study was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Colorado State University prior to conduct of the research.

Results

Sensitivity of Salmonella cervid PrP to Proteinase K (PK) digestion

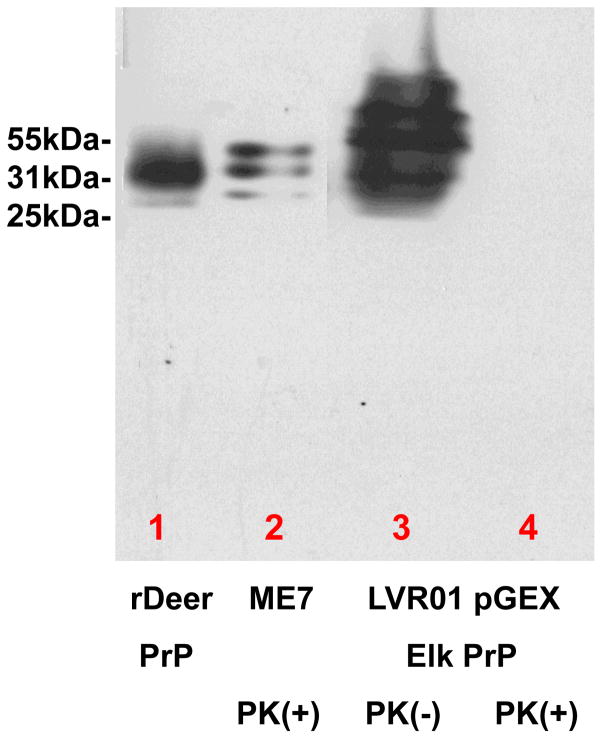

The cervid PrP being produced by the still viable Salmonella constructs, is fully PK sensitive, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the expression of cervid PrP in the Salmonella LVR01 vaccine strain, by Western blot using monoclonal anti-PrP 7D9/6D11 [18]. In lane one cervid rPrP was run. In lane 2 PrP strain ME7 was run following proteinase K treatment. Lane 3 shows the expression of cervid PrP by the Salmonella LVR01 and lane 4 the same preparation with proteinase K treatment. As can be seen in lane 4 the cervid PrP was completely digested, while, as expected, the ME7 PrPSc in lane 2 was PK resistant. This shows that our Salmonella LVR01 can express high levels of cervid PrP and also that this cervid PrP is fully PK sensitive.

Anti-cervid PrP Responses to Vaccination

IgA, IgG or IgM levels assessed by ELISA

No differences in the levels of IgA, IgG or IgM were noted at T0 in the feces, saliva or plasma (Figure 2). In the feces an increasing IgA titer is noted from T5 to T7, with p<0.05, p=0.0009 and p<0.0001 for T5, T6 and T7, respectively (figure 2A). In the saliva, markedly increasing IgA titer is noted from T5 to T7, with p<0.0036, not significant and p=0.008 for T5, T6 and T7, respectively (figure 2B). In the plasma the anti-PrP IgG titers were low but were significantly higher compared to controls; p=0.0067, p=0.01 and p<0.016 for T5, T6 and T7, respectively (figure 2C). The anti-cervid PrP IgM titers in the plasma were higher than the IgG titers, with the titers increasing from T5 to T7. p=0.01, p=0.002 and p=0.01 for T5, T6 and T7, respectively (figure 2D). The one deer to have protection from CWD infection (deer 781) had the highest anti-cervid PrP titers of IgA in the feces and saliva, as well as the highest IgG and IgM titers in the plasma.

Figure 2.

2A): Titers of IgA in the cervid feces. The feces IgA were obtained using our published methods [15;18]. The titers illustrate the importance of mucosal application of a boost of oligomerized recombinant cervid PrP after a primary mucosal immune response is established. T0 refers to “time zero” or pre-immunization titers, while T5, T6 and T7 refer to the fifth and subsequent collections of cervid feces. The T5 titer of anti-PrP IgA in vaccinated deer was significantly higher than control T5 anti-PrP IgA (p<0.05), but was low. This titer improved in T6 and 7 following boosts of oligomerized recombinant cervid PrP (T6, p=0.0009 and T7, p<0.0001).

2B): Cross-reactive anti-deer PrP IgA titers (measured with anti-goat IgA) in saliva of vaccinated (red bars) and control deer (blue bars). For T5 titer the p=0.0036. T7 had a much higher titer (compared to T5) with the p=0.008.

2C): Anti-deer PrP IgG titers in plasma of vaccinated (red bars) and control deer (blue bars). The anti-PrP IgG titers in the plasma were low but significantly different from controls. For T5 titer the p=0.0067. For T6 the p=0.01. For T7 the p=0.016.

2D): Cross-reactive anti-deer PrP IgM titers (measured with anti-goat IgM) in plasma of vaccinated (red bars) and control deer (blue bars). The titer from T5 to T7 is increasing. For T5 titer the p=0.01. For T6 the p=0.002. For T7 the p=0.01.

Western Blot Evaluations

The vaccinated deer plasma IgG and saliva IgA were tested for reactivity to polymerized cervid PrP, aged/aggregated cervid PrP, polymerized sheep PrP, aged sheep PrP, PrPCWD, and lysates of LVR01. Both vaccinated and control deer had a strong immune response to lysates of LVR01, as expected (see figure 3 lane 1 of A and B). Pre-immune plasma (T0) from both vaccinated and control deer had no reactivity to LVR01, also as expected (data not shown). Control deer plasma IgG had no reactivity by Western blot to polymerized cervid PrP, aged/aggregated cervid PrP, polymerized sheep PrP, aged sheep PrP, or PrPCWD (See figure 3B). Control deer saliva IgA also had no reactivity by Western blot to polymerized cervid PrP, aged/aggregated cervid PrP, polymerized sheep PrP, aged sheep PrP, or PrPCWD (data not shown). The plasma IgG of deer 781 (which had the highest titers) reacted particularly strongly with polymerized cervid PrP and PrPCWD (figures 3 and 4). The plasma IgG of 781 also reacted with aged/aggregated cervid PrP, polymerized sheep PrP, aged sheep PrP and scrapie brain homogenate (figure 3 and 4). The saliva IgA of 781 also reacted with PrPCWD and scrapie brain homogenate (figure 4).

Figure 3.

In 3A purified deer Ig from plasma of deer 781 (with full protection) was used for Western blots and compared to purified deer Ig from a control deer (deer 786, figure 3B). All lanes were equally loaded with 4μg protein. Anti-deer IgG was used for detection of the Western blots in 3A and 3B. In lane 1 the lysate of vector LVR01 was run and a very strong reaction is seen both in the vaccinated and control deer to the highly immunogenic Salmonella, as expected. The control showed no reaction to any of the PrP antigens loaded in lanes 2–5 of Fig 3B (which was the case for all the control deer, data not shown). Deer 781 plasma IgG reacted strongly to polymerized deer recombinant PrP (lane 5, see red arrow) and faintly to aggregated deer recombinant PrP (lane 4, blue arrow). Deer 781 also detected a distinct band of polymerized sheep PrP (lane 3, black arrow), as well as faintly detecting aged sheep recombinant PrP (lane 2, see green arrow)

Figure 4.

Western blots analysis of the reactivity of the plasma IgG and saliva IgA of vaccinated deer 781 versus CWD brain and scrapie preparations. In each gel (A–C) each lane was loaded with samples following PK digestion consisting of: lane 1, Elk brain homogenate; lane 2, 20% brain homogenate of a mule deer with CWD; lane 3, 20% brain homogenate of a 22L scrapie brain; lane 4, 1% brain homogenate of a CWD infected white-tailed deer; lane 5, 10% brain homogenate of a cervid PrP expressing Tg mouse infected with CWD; lane 6, 10% brain homogenate of a CWD infected white-tailed deer. In A, the primary antibody was anti-PrP monoclonal antibodies 7D9/6D11 at 1:8000. The secondary antibody was anti-mouse IgG-HRP at 1:2000. In B, ammonium sulphate precipitated Ig from the plasma of deer 781 was used at 1:200 as a primary antibody. The secondary antibody was anti-deer IgG-HRP (1:2000). In C, ammonium sulphate precipitated Ig from the saliva of deer 781 was used at 1:100 as a primary antibody. The secondary antibody was anti-goat IgA-HRP at 1:1250 (which was cross reactive with cervid IgA). As can been seen in B and C, the plasma IgG and saliva IgA from deer 781 is reactive to both CWD and scrapie preparations.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) and Western blot studies

IHC analysis of control and vaccinated deer tonsil and RAMALT biopsies showed all deer to be negative 90 days after CWD oral challenge. 120 days after challenge 5/6 control deer had positive IHC for CWD in the tonsil and RAMALT while 3/5 vaccinated deer were positive (see figure 5A and C). Nine months after challenge an additional vaccinated deer had positive CWD IHC (4/5). One year after challenge all control deer were positive for CWD by IHC (6/6), while one vaccinated deer remained negative (deer 781). Deer 781 has remained free of CWD symptoms and of CWD by IHC of tonsils and RAMALT biopsies (3 years and 7 months after challenge), having shared a room with infected animals for >1yr. The presence of PrPCWD was confirmed in the lymphoid tissue and brains by both immunohistochemistry and Western blots of all control and vaccinated deer showing signs of CWD at the time of necropsy (Figure 5A–E).

Figure 5.

Anti-PrP immunostaining of biopsies in control vector only Salmonella treated deer (Figure 5A and C) compared to vaccinated deer 781 that remained negative for CWD (Figure 5B and D). In A and B tonsil biopsies are shown, while in C and D RAMALT biopsies are shown. The scale bars = 200μm.

5E): Western blot of brain homogenates from a deer negative for CWD in lanes 1 and 2 and a positive control deer with CWD in lanes 3 and 4 (neither deer is from our study). In lanes 5 and 6 brain homogenates were run from one of the LVR01 vector control deer from our study 120 days after challenge. The lanes alternate for proteinase K (PK) non-treated homogenate and treated homogenate. As can be seen, there is no PrPCWD in the assay negative control deer (lane 2), while PrPCWD is evident in the positive control deer (lane 4) and from our study control LVR01 vector exposed and CWD challenged deer.

Survival of Vaccinated and Control Deer

Figure 6 shows the Kaplan and Meier survival curve of the vaccinated versus control deer. The vaccinated deer had a significant prolongation of the incubation period of CWD (p=0.012 by Weibull regression analysis). The one deer in the vaccinated group free from CWD clinically and by both tonsil and RAMALT biopsies, was fully sensitive to CWD (codon 96G/G). The one deer in the control group that had a prolonged incubation of 953 days (other controls incubations were: 477, 477, 538, 666, and 670 days) had codon 96G/S. The typical incubation of codon 96G/G deer is ~600 ±40 days, while for codon 96G/S is ~750 ±100 days [[21;22] and unpublished results]. The one deer (deer 781) with protection had the highest titer to cervid recombinant PrP and PrPCWD.

Figure 6.

Current Kaplan-Meier survival curve of the control LVRO1 vector exposed (n=6) and vaccinated deer (n=5). The vaccinated deer had partial protection from CWD infection (p=0.012 by Weibull regression analysis). Deer 781 in the vaccinated group has remained free from clinical CWD (~1310 days after challenge) with negative tonsil and RAMALT biopsies, in spite of sharing a den with CWD infected deer for > 1yr. In this study two deer in each group were included with a Prnp polymorphism of G/S at codon 96 (other polymorphisms were matched and are associated with sensitivity to CWD). Codon 96 G/S versus G/G is the most common (25%) deer polymorphism (one of 5) that confers partial resistance to CWD infection [21;22]. Significantly deer 781 was fully sensitive to CWD (codon 96G/G). The one deer in the control group that had a prolonged incubation of 953 days (other controls incubations were: 477, 477, 538, 666, and 670 days) had codon 96G/S (which confers some resistance to CWD infection); hence, its longer incubation period was likely related to this polymorphism.

Discussion

In the present study we have tested a prion vaccination in a species naturally at risk for prion infection and found, for the first time, at least a partial therapeutic response. Recently Pilon et al assessed systemic immunization in deer with PrP peptides, but documented only titers to the synthetic peptides and failed to produce any therapeutic effect [29]. Mucosal immunization is potentially an ideal means to prevent prion transmission and infection which typically has an oral route. Importantly, mucosal immunization can be designed to induce primarily a humoral immune response with a secretory IgA response; thereby, avoiding the cell mediated inflammatory response that was the major cause of toxicity in the initial human AD active vaccine trial [30–33]. Moreover, Salmonella is known to target M-cell, antigen sampling cells in the intestines, which have been shown to play a role in PrPSc uptake [34–37]. Live attenuated strains of Salmonella enterica have been used for many years as mucosal vaccines against salmonellosis and as delivery systems for the construction of multivalent vaccines with broad applications in human and veterinary medicine [16;38–40]. We show that our vaccination strategy is able to break mucosal immunological tolerance to PrP in white-tailed deer, with production of gut and saliva IgA, as well as systemic IgM and IgG reactive to aggregated recombinant cervid PrP and also to PrPCWD. This implies, as a proof of concept, that the aroC attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium LVR01 can be internalized in the intestines of deer, most likely in the lymphoid follicles as previously shown [18], be taken by dendritic cells (DCs) and present the incorporated PrP to mesenteric lymph nodes to produce a primarily mucosal immune response. Use of our Salmonella Typhimurium LVR01 could be affected by prior Salmonella infection and pre-existing antibodies to Salmonella. However, previous studies have shown that the prevalence of Salmonella infection and the presence of anti-Salmonella plasma antibodies in free range and semi-domesticated cervid populations is very low (<1%) [41;42]; hence, this is unlikely to be a significant limitation.

Although the oral vaccination was able to break mucosal immunological tolerance to self-PrP, the titers obtained were only a small fraction of the immune response generated against the whole Salmonella, as can be inferred from figure 3. Nevertheless, as proven previously and stated above, these relatively low titers were sufficient to interfere with the cycle of transmission and infection [14;15;18]. One deer out of 5 in our vaccination group had the highest titers of IgA, IgM and IgG in all biological fluids tested, remained without CWD symptoms, with negative RAMALT and tonsil biopsies, in spite of sharing a room (with resultant frequent grooming and CWD infected saliva contact) for > 1yr. with CWD infected deer. Importantly this deer has a Prnp genotype with full sensitivity to CWD (codon 96G/G). The one deer in the control group that had a prolonged incubation of 953 days had codon 96G/S; hence, its longer incubation period was likely related to this polymorphism. In this study we did not have the animals or opportunity to first determine the minimal infectious dosage of the CWD agent by the oral route in white-tailed deer. The CWD inoculum used was a dosage that we knew from previous studies to result in 100% infection rates in deer; however, it was likely a much higher dose than deer are likely to be exposed in nature. Hence, it is possible to speculate that our current vaccination procedure could have a greater degree of protection against a CWD inoculum that reflects a dose more likely to occur in the wild.

In our prior studies of mucosal vaccination for prion infection in mice we used the attenuated Salmonella vector expressing two tandem copies of murine PrP and showed that in wild-type CD1 mice, it was possible to break immunological tolerance to PrP and that the immune response could partially protect against oral challenge from scrapie (22L) prion infection [15;18]. A number of subsequent studies have shown that tolerance to PrP can be broken in non-genetically modified mice resulting in modest anti-PrP titers [43–45]. These titers could be greatly increased by using stronger immunogenic formulations, such as multiple antigen peptides using PrP peptide fragments [46] and viral delivery systems [47]. However, these immunization approaches had not been tested for effectiveness against prion infection challenge. Three groups have shown that PrP fragments applied as immunogens in multiple booster protocols in wild-type mice can lead to slight prolongations of the incubation period of prion infection with all vaccinated mice developing prion infection [45;46;48]. In our second study, also using attenuated Salmonella vector expressing two copies of murine PrP, we showed that in the subset of mice which developed a high mucosal anti-PrP IgA response and a high systemic anti-PrP titer, all animals had complete protection from prion infection [18]. Similarly in our current cervid study the one deer, out of five, that had the highest mucosal and systemic immune response to PrP, had protection from prion infection. In our mouse immunization studies we performed 6 oral vaccinations prior to scrapie challenge in order to produce a protective immune response. In the present study 8 vaccinations were needed to produce an adequate response. In addition, in the later immunizations we also applied boosts using polymerized recombinant cervid PrP applied to the tonsils and rectum to augment the subset of antibodies directed to conformationally diverse PrP. This was done not only to enhance the mucosal immune response, but also because it has been shown that the tonsils are early sites of CWD replication [26;49]. In future studies, we hope to improve the delivery of the inoculum to obtain higher specific antibody titers, with fewer oral immunizations and without the use of tonsil/rectal boosts, by increasing the level of cervid PrP production by our Salmonella vector and/or inducing expression of shorter repetitive PrP sequences that produce a more conformational and protective humoral response. We introduced the Salmonella vector by stomach tube to obtain a true primary mucosal immune response; however, subsequently we found that the vaccine could be administered mixed with food, so deer can be dosed repeatedly without anesthesia. Thus, it would be possible to dose individual deer in a free-range herd repeatedly, using food pellets containing vaccine Salmonella left in the environment at appropriate times, given the known tendency of herds to return to the same foraging grounds at regular intervals. The delivery of vaccines in bait or feed has been widely used as a wildlife management option [50]. It has also been documented that Salmonella can be stable for months when dried under certain conditions and mixed with food [51]. In addition we have previously shown that kept at 4°C vaccine Salmonella are viable >48hrs [15;18] and the actual Salmonella used in this deer experiment were >90% viable after 24hrs at room temperature (data not shown). The use of slow release pellet preparations for cervids in the wild or farmed animals could ensure adequate stimulation of the entire GI tract (including the tonsils), though the constant rumination of cervids, and the polymerized recombinant PrP could be added in subsequent boosts. The safety of such a strategy is documented by our data that the PrP produced by our Salmonella vector and the polymerized recombinant PrP are fully PK sensitive. Furthermore, the Salmonella carrier cannot survive in the environment for more than four days; therefore, there is no infection risk. Hence, we believe that a more optimally designed Salmonella vector vaccine would have the potential to be scaled up, in order to be tested in the wild. Even if such a vaccine gave only partial protection from CWD, increasing the herd immunity would inhibit the current rapid spread of CWD, thus reducing the zoonotic potential.

Our reported results show for the first time that protection from exogenous prion infection is possible in a species naturally at risk for infection. Further refinements to increase the degree of mucosal humoral immunity induced and to target the response more specifically against the PrPSc conformation are underway.

Highlights.

We have developed a Salmonella vaccine strain that expresses cervid PrP

The Salmonella vaccine has been tested in white tailed deer

The vaccine induced a mucosal and systemic response to cervid PrP and PrPCWD

Vaccinated deer had partial protection for chronic wasting disease.

This is the first partially effective vaccine for a prion disease

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants: NIH NS047433, ARRA NS047433-06S1, NS073502, NIH contract HHS-N272201000009I-TO-D05, and the Seix Dow Foundation. We appreciate the essential contribution of Ms. Sallie Dahmes in Monroe, Georgia who hand raised the white-tailed deer used in this study, and Ms. Kelly Anderson for her excellent help with deer care and procedures in this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Colby DW, Prusiner SB. Prions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011 Jan;3(1):a006833. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harman JL, Silva CJ. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009 Jan 1;234(1):59–72. doi: 10.2460/javma.234.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams ES. Chronic wasting disease. Vet Pathol. 2005 Sep;42(5):530–49. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-5-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saunders SE, Bartelt-Hunt SL, Bartz JC. Occurrence, transmission, and zoonotic potential of chronic wasting disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012 Mar;18(3):369–76. doi: 10.3201/eid1803.110685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell GB, Sigurdson CJ, O’Rourke KI, et al. Experimental oral transmission of chronic wasting disease to reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams ES, Young S. Chronic wasting disease of captive mule deer: a spongiform encephalopathy. J Wildl Dis. 1980 Jan;16(1):89–98. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-16.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams ES, Young S. Spongiform encephalopathy of Rocky Mountain elk. J Wildl Dis. 1982 Oct;18(4):465–71. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-18.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilch S, Chitoor N, Taguchi Y, Stuart M, Jewell JE, Schatzl HM. Chronic wasting disease. Top Curr Chem. 2011;305:51–77. doi: 10.1007/128_2011_159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beekes M, McBride PA. The spread of prions through the body in naturally acquired transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. FEBS J. 2007 Feb;274(3):588–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safar JG, Lessard P, Tamguney G, et al. Transmission and detection of prions in feces. J Infect Dis. 2008 Jul 1;198(1):81–9. doi: 10.1086/588193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denkers ND, Hayes-Klug J, Anderson KR, et al. Aerosol transmission of chronic wasting disease in white-tailed deer. J Virol. 2013 Feb;87(3):1890–2. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02852-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsh RF, Kincaid AE, Bessen RA, Bartz JC. Interspecies transmission of chronic wasting disease prions to squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) J Virol. 2005 Nov;79(21):13794–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13794-13796.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Race B, Meade-White KD, Miller MW, et al. Susceptibilities of nonhuman primates to chronic wasting disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009 Sep;15(9):1366–76. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wisniewski T, Goni F. Could immunomodulation be used to prevent prion diseases? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012 Mar;10(3):307–17. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goni F, Knudsen EL, Schreiber F, et al. Mucosal vaccination delays or prevents prion infection via an oral route. Neurosci. 2005;133:413–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hegazy WA, Hensel M. Salmonella enterica as a vaccine carrier. Future Microbiol. 2012 Jan;7(1):111–27. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chabalgoity JA, Moreno M, Carol H, Dougan G, Hormaeche CE. A dog-adapted Salmonella Typhimurium strain as a basis for a live oral Echinococcus granulosus vaccine. Vaccine. 2000;19:460–9. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goni F, Prelli F, Schreiber F, et al. High titers of mucosal and systemic anti-PrP antibodies abrogates oral prion infection in mucosal vaccinated mice. Neurosci. 2008;153:679–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chabalgoity JA, Khan CM, Nash AA, Hormaeche CE. A Salmonella typhimurium htrA live vaccine expressing multiple copies of a peptide comprising amino acids 8–23 of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D as a genetic fusion to tetanus toxin fragment C protects mice from herpes simplex virus infection. Molecular Microbiology. 1996 Feb;19(4):791–801. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.426965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goni F, Herline K, Peyser D, et al. Immunomodulation targeting both Aβ and tau pathological conformers ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease pathology in TgSwDI and 3xTg mouse models. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2013;10(1):150. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson CJ, Herbst A, Duque-Velasquez C, et al. Prion protein polymorphisms affect chronic wasting disease progression. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e17450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson SJ, Samuel MD, O’Rourke KI, Johnson CJ. The role of genetics in chronic wasting disease of North American cervids. Prion. 2012 Apr;6(2):153–62. doi: 10.4161/pri.19640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goni F, Prelli F, Ji Y, et al. Immunomodulation targeting abnormal protein conformation reduces pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(10):e13391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denkers ND, Telling GC, Hoover EA. Minor oral lesions facilitate transmission of chronic wasting disease. J Virol. 2011 Feb;85(3):1396–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01655-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angers RC, Kang HE, Napier D, et al. Prion strain mutation determined by prion protein conformational compatibility and primary structure. Science. 2010 May 28;328(5982):1154–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sigurdson CJ, Williams ES, Miller MW, Spraker TR, O’Rourke KI, Hoover EA. Oral transmission and early lymphoid tropism of chronic wasting disease PrPres in mule deer fawns (Odocoileus hemionus) J Gen Virol. 1999 Oct;80( Pt 10):2757–64. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-10-2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seelig DM, Mason GL, Telling GC, Hoover EA. Chronic wasting disease prion trafficking via the autonomic nervous system. Am J Pathol. 2011 Sep;179(3):1319–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denkers ND, Seelig DM, Telling GC, Hoover EA. Aerosol and nasal transmission of chronic wasting disease in cervidized mice. J Gen Virol. 2010 Jun;91(Pt 6):1651–8. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.017335-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilon JL, Rhyan JC, Wolfe LL, et al. Immunization with a synthetic peptide vaccine fails to protect mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) from chronic wasting disease. J Wildl Dis. 2013 Jul;49(3):694–8. doi: 10.7589/2012-07-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delrieu J, Ousset PJ, Caillaud C, Vellas B. ‘Clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease’: immunotherapy approaches. J Neurochem. 2012 Jan;120(Suppl 1):186–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wisniewski T. Active immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012 Jun 1;11(7):571–2. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70136-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wisniewski T, Goni F. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boutajangout A, Wisniewski T. Tau-based therapeutic approaches for Alzheimer’s Disease - a mini-review. Gerontology. 2014;60:381–5. doi: 10.1159/000358875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heppner FL, Christ AD, Klein MA, et al. Transepithelial prion transport by M cells. Nat Med. 2001 Sep;7(9):976–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mabbott NA, MacPherson GG. Prions and their lethal journey to the brain. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006 Mar;4(3):201–11. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sigurdsson EM, Wisniewski T. Promising developments in prion immunotherapy. Exp Review Vaccines. 2005;4:607–10. doi: 10.1586/14760584.4.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donaldson DS, Kobayashi A, Ohno H, Yagita H, Williams IR, Mabbott NA. M cell-depletion blocks oral prion disease pathogenesis. Mucosal Immunol. 2012 Mar;5(2):216–25. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mastroeni P, Chabalgoity JA, Dunstan SJ, Maskell DJ, Dougan G. Salmonella: immune responses and vaccines. Veterinary Journal. 2001 Mar;161(2):132–64. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.2000.0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tacket CO, Sztein MB, Wasserman SS, et al. Phase 2 clinical trial of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar typhi oral live vector vaccine CVD 908-htrA in U.S. volunteers. Infect Immun. 2000 Mar;68(3):1196–201. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1196-1201.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirkpatrick BD, McKenzie R, O’Neill JP, et al. Evaluation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (Ty2 aroC-ssaV-) M01ZH09, with a defined mutation in the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2, as a live, oral typhoid vaccine in human volunteers. Vaccine. 2006 Jan 12;24(2):116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aschfalk A, Muller W. Differences in the seroprevalence of Salmonella spp. in free-ranging and corralled semi-domesticated reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) in Finland. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2003 Dec;110(12):498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lillehaug A, Bergsjo B, Schau J, Bruheim T, Vikoren T, Handeland K. Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp. verocytotoxic Escherichia coli, and antibiotic resistance in indicator organisms in wild cervids. Acta Vet Scand. 2005;46(1–2):23–32. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-46-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilch S, Wopfner F, Renner-Muller I, et al. Polyclonal anti-PrP auto-antibodies induced with dimeric PrP interfere efficiently with PrPSc propagation in prion-infected cells. J Biol Chem. 2003 May 16;278(20):18524–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nikles D, Bach P, Boller K, et al. Circumventing tolerance to the prion protein (PrP): vaccination with PrP-displaying retrovirus particles induces humoral immune responses against the native form of cellular PrP. J Virol. 2005 Apr;79(7):4033–42. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4033-4042.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pilon J, Loiacono C, Okeson D, et al. Anti-prion activity generated by a novel vaccine formulation. Neurosci Lett. 2007 Dec 18;429(2–3):161–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arbel M, Lavie V, Solomon B. Generation of antibodies against prion protein in wild-type mice via helix 1 peptide immunization. J Neuroimmunol. 2003 Nov;144(1–2):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Handisurya A, Gilch S, Winter D, et al. Vaccination with prion peptide-displaying papillomavirus-like particles induces autoantibodies to normal prion protein that interfere with pathologic prion protein production in infected cells. FEBS J. 2007 Apr;274(7):1747–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishibashi D, Yamanaka H, Yamaguchi N, et al. Immunization with recombinant bovine but not mouse prion protein delays the onset of disease in mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted prion. Vaccine. 2007 Jan 22;25(6):985–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathiason CK, Powers JG, Dahmes SJ, et al. Infectious prions in the saliva and blood of deer with chronic wasting disease. Science. 2006 Oct 6;314(5796):133–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1132661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorensen A, van Beest FM, Brook RK. Impacts of wildlife baiting and supplemental feeding on infectious disease transmission risk: a synthesis of knowledge. Prev Vet Med. 2014 Mar 1;113(4):356–63. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muller K, Aabo S, Birk T, Mordhorst H, Bjarnadottir B, Agerso Y. Survival and growth of epidemically successful and nonsuccessful Salmonella enterica clones after freezing and dehydration. J Food Prot. 2012 Mar;75(3):456–64. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]