Abstract

Background

Post-visit “booster” sessions have been recommended to augment the impact of brief interventions delivered in the Emergency Department (ED). This paper, which focuses on implementation issues, presents descriptive information and interventionists’ qualitative perspectives on providing brief interventions over the phone, challenges, “lessons learned”, and recommendations for others attempting to implement adjunctive booster calls.

Method

Attempts were made to complete two 20-minute telephone “booster” calls within a week following a patient’s ED discharge with 425 patients who screened positive for and had recent problematic substance use other than alcohol or nicotine.

Results

Over half (56.2%) of participants completed the initial call; 66.9% of those who received the initial call also completed the second call. Median number of attempts to successfully contact participants for the first and second calls was 4 and 3, respectively. Each completed call lasted an average of about 22 minutes. Common challenges/barriers identified by booster callers included unstable housing, limited phone access, unavailability due to additional treatment, lack of compensation for booster calls, and booster calls coming from an area code different than the participants’ locale and from someone other than ED staff.

Conclusions

Specific recommendations are presented with respect to implementing a successful centralized adjunctive booster call system. Future use of booster calls might be informed by research on contingency management (e.g., incentivizing call completions), smoking cessation quitlines, and phone-based continuing care for substance abuse patients. Future research needs to evaluate the incremental benefit of adjunctive booster calls on outcomes over and above that of brief motivational interventions delivered in the ED setting.

Keywords: motivational interviewing, brief intervention, booster calls, substance abuse, emergency department

1. Introduction

There were over 4.9 million drug-related Emergency Department (ED) visits in United States in 2010, with nearly half of them (46.8%, or 2.3 million visits) due to drug misuse/abuse (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012). ED patients are more likely than either the general population or primary care patients to report drug use (Cherpitel & Ye, 2008; Cunningham et al., 2009; Rockett, Putnam, Jia, & Smith, 2003). It has been recommended that brief interventions be tested with drug-using ED patients (Cunningham, et al., 2009). In addition to its potential public health impact (Babor et al., 2007), the implementation of brief interventions targeting drug use may also reduce avoidable health care costs (Rockett, Putnam, Jia, Chang, & Smith, 2005).

An Emergency Department visit may present a “teachable moment” during which drug-using patients may be more contemplative about the impact that their alcohol or drug use is having on their lives and, as such, they may be more receptive to an intervention addressing those concerns (Minugh et al., 1997; Williams, Brown, Patton, Crawford, & Touquet, 2005). However, such moments, or windows of opportunity, may be less impactful for those who do not see a temporal relationship between their ED visit and their substance use. In fact, those who view their ED visit primarily or exclusively as a medical issue, even if they have a history of alcohol or drug use, may view a brief intervention targeting their substance use as an unrelated and unwelcome intrusion (Longabaugh et al., 2001). Also, the general level of activity, potential lack of privacy, brevity of available time, and degree of chaos during an ED visit may make it difficult to provide an effective intervention in that setting (E. Bernstein & Bernstein, 2008; Daeppen et al., 2007; Mello, Longabaugh, Baird, Nirenberg, & Woolard, 2008; Mello, Nirenberg, Woolard, Baird, & Longabaugh, 2007; Nilsen et al., 2008). Even if initially successful, the benefits of identifying and intervening with a hazardous drinker or drug user may dissipate somewhat rapidly over time (McCambridge & Strang, 2004, 2005; Williams, et al., 2005). Although possibly a teachable moment, it is not clear the extent to which the “lesson” conveyed by the intervention has been learned or retained once the individual leaves the ED.

Rather than serving as the site for maximal brief intervention effectiveness, the ED setting might more appropriately be seen as one in which patients are motivated to engage in discussions about their substance use at a later point after the immediate medical crisis has been resolved and when they may be more receptive to interventions (Nilsen, et al., 2008). Such considerations have led to the recommendation that multi-contact interventions or “booster sessions” be provided, either in person or via phone (Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative, 2007; E. Bernstein & Bernstein, 2008; E. Bernstein et al., 2009; Longabaugh, et al., 2001). As Bernstein and Bernstein (E. Bernstein & Bernstein, 2008) state, “A booster session or referral for follow-up sessions outside the confines of a busy ED may be needed in addition to a 10-minute intervention in the course of clinical care” (p. 752).

While the initial brief intervention in the ED may get individuals to focus on and contemplate possibly changing risk-related behaviors, it might not be sufficient to motivate them to develop and implement a change plan. However, a booster session after leaving the ED can remind them of the intervention, encourage and reinforce their commitment to change as well as explore barriers that they may have encountered, and reinforce their putting their change plan into action (Lee, et al., 2010; Longabaugh, et al., 2001).

A number of investigators have followed this recommendation and have begun to incorporate booster sessions following the initial ED or trauma center visit as a component of a more extensive intervention. While some of the follow-up boosters have been done through a letter summarizing the session (Gentilello et al., 1999) or as a second face-to-face session (Longabaugh, et al., 2001), a larger number of such follow-up sessions have been delivered over the phone (E. Bernstein, et al., 2009; J. Bernstein et al., 2010; Bogenschutz et al., 2011; D’Onofrio et al., 2012; Soderstrom et al., 2007; Sommers et al., 2006). As is true for the initial brief interventions (Nilsen, et al., 2008), such calls appear to vary along a number of dimensions, such as completion rates and duration; however, there is limited information in the literature about these dimensions as well as their content, implementation, and effectiveness.

Similarly, while attractive as an intervention extender, such booster calls may be difficult to implement within the ED setting (Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative, 2007, 2010). Again, however, details about implementation barriers and successes are scarce.

Because booster calls are an attractive and increasingly frequent addition to interventions to help ED-visiting alcohol and drug users, a more detailed exposition of challenges and successes in implementing and conducting booster calls would guide more effective booster calls in future interventions. The purpose of the present paper is to (1) provide descriptive information concerning post-ED visit booster phone calls and interventionists’ qualitative perspectives on providing brief interventions over the phone; (2) present information about factors that appear to impede or facilitate implementation of booster calls; and (3) make recommendations if booster calls are to be incorporated into and implemented as part of future research studies or clinical practice.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Participants

This study describes the methodology for conducting brief, Motivational Interviewing (MI) interventions via booster telephone follow-up calls to participants in one arm of a multi-site randomized clinical trial on screening and brief intervention with drug users in six EDs across the United States (Bogenschutz, et al., 2011; Donovan et al., 2012). The trial’s primary objective was to compare substance use and related outcomes among substance abusing ED patients randomized to either 1) minimal screening only (MSO); 2) screening, assessment and referral to treatment if indicated (SAR); or 3) screening, assessment, and referral plus a brief intervention with two telephone follow-up booster calls (BI-B). The trial was conducted within the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network, between 2010 and 2012. The current report focuses only on the BI-B arm of the study, and more specifically on the methods employed to organize, implement, and conduct booster follow-up phone calls to 425 adults who had received a brief intervention in the ED.

2.1.1. Booster Counselors

Booster calls were conducted by one male and two female counselors. One had a master’s degree in social work and had also worked in an Emergency Department; the other two had master’s degrees in counseling. All previously had been certified as MI practitioners and had experience conducting brief MI interventions in both clinical and research settings, with approximately 5–10 years of brief intervention experience. All booster calls were made from the study’s centralized Booster Call Center located at the University of Washington in Seattle.

2.1.1.1. Counselor Training and Supervision

Booster counselors received standardized 2-day training in Motivational Interviewing and study procedures. Two counselors received this training at a national kick-off meeting with lead investigators and ED counselors, while one (hired part-way through the study) received it via webinar. Following the training, each counselor completed four booster sessions with “pilot” participants who had consented to participate in the study for training purposes. Each pilot session was audiotaped and reviewed by lead fidelity monitors at the centralized Certification and Monitoring Center at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, who coded for adherence to the protocol and to MI principles using the centralized Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) system (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson, & Miller, 2005). After four sessions in which criteria were met, booster counselors were considered fully certified for the study.

Booster counselors met bi-weekly with a designated supervisor to review and discuss cases. The booster counselor supervisor reviewed 1 audio recording of a booster session per week for each booster counselor (total of 3 sessions/week). Supervision was conducted in a group format. The supervisor provided feedback based on the reviewed audiotaped sessions, and facilitated discussion and problem solving of common challenges that arose in the booster call process over the course of the trial.

As part of the training and certification of the ED counselors in the first two sites to begin the study, ED and booster counselors had to conduct their respective brief interventions with consenting pilot subjects. A major difference in the procedures between this pilot and the main phase of the trial was that pilot participants received $30 remuneration for completing each booster call whereas main trial participants had no such financial incentive. This procedural difference allowed for subsequent analyses to explore whether there were differences in response rates between calls in which an incentive was or was not provided.

2.1.1.2. Fidelity Monitoring

All sessions were audio recorded for fidelity monitoring purposes. Participants were informed of these procedures during their study informed consent process. All participants provided written informed consent with study research staff at their local EDs. All sites, including the centralized Booster Call Center, obtained approval and were overseen by their local institutional review boards. The centralized Certification and Monitoring Center reviewed approximately 5% of booster counselors’ sessions on an ongoing basis during the trial, using the MITI and a checklist.

2.1.2. Study Participant Recruitment

Male and female adult patients were recruited from six geographically diverse EDs across the US (one each from the Southwest and Midwest, and two each from the Southeast and Northeast). Potential participants were screened by study research staff for study participation upon admission to the ED for medical treatment. Study inclusion criteria were: 1) registration as a patient in the ED during study screening hours; 2) positive screen (≥3) for problematic use of a non-alcohol, non-nicotine drug based on the Drug Abuse Screening Test (Skinner, 1982); 3) at least one day of problematic drug use (excluding alcohol and nicotine) in the past 30 days; 4) age 18+; 5) adequate English proficiency and ability to provide informed consent; and 6) access to a phone (for booster telephone sessions). Reasons for exclusions included, 1) inability to participate due to emergency treatment; 2) significant impairment of cognition or judgment rendering the person incapable of informed consent (e.g. delirium, intoxication, traumatic brain injury); 3) status as a prisoner or in police custody at the time of treatment; 4) current engagement in addiction treatment; 5) residing more than 50 miles from the location of follow-up visits; 6) inability to provide at least two reliable locators as contacts; 7) prior participation in the current study.

2.2. A “warm” hand-off

Participants randomized to the BI-B condition received a 30-minute manual-guided motivational enhancement intervention from study counselors while they were in the ED. The intervention included feedback based on screening information, the Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu of options, Empathy, and Self-efficacy (FRAMES) heuristic, and development of a change plan for their problematic drug use. Counselors informed participants that they would receive up to two booster calls from booster counselors located in Seattle, Washington, approximately 3 and 7 days after ED discharge. In order to maximize the likelihood of participants successfully connecting with a booster counselor, ED counselors made explicit and repeated explanations of what to expect in the coming 3 to 7 days, and prepped them to expect a call from the Seattle area code. ED counselors also collected, but did not necessarily verify, additional contact information for a number of other friends and family who might aid in locating the participant.

2.3. Booster intervention

Information collected as part of the initial screening in the ED, including scores on the 10-item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) (Gavin, Ross, & Skinner, 1989), the 3-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test consumption subscale (AUDIT-C) (Bradley et al., 2007; Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998), the 4-item Heavy Smoking Index (Diaz et al., 2005), and three items to determine the primary substance of abuse, days of use of the primary substance, and the perceived substance-relatedness of the ED visit; the NIDA modified version of the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking, Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) (Humeniuk et al., 2008) collected as part of the more thorough assessment process; and ED counselors’ summaries of issues raised and change plans developed as part of the brief intervention in the ED, were all made available to booster callers through a centralized electronic data management system accessible through the internet. This information helped orient the booster callers to the unique issues of each participant they were contacting, facilitated the introduction of the caller to the participant, and helped frame and guide the initial booster call.

The telephone booster calls were made from a centralized, study-wide intervention booster call center, by the interventionists who had received the previously described standardized training and supervision. The calls were intended to “boost” the effects of the initial brief intervention in the ED. The number of booster sessions (2), in combination with the brief intervention in the ED, was chosen to replicate the structure of the standard Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) (W.R. Miller, Zweben, Diclemente, & Rychtarik, 1992) with the goal of maximizing the magnitude of the therapeutic effect while keeping the intervention short enough to be practical. Each call was targeted to last approximately 20 minutes.

The content of the booster calls was patterned after sessions in MET (Longabaugh, et al., 2001; W.R. Miller, et al., 1992). The phone booster process was similar to those previously used to deal with problem drinkers in EDs, either as part of stepped-care interventions initiated in the ED and continued following discharge (E. Bernstein, et al., 2009; J. Bernstein, et al., 2010; Bischof et al., 2008; D’Onofrio, et al., 2012) or as stand-alone phone-delivered brief interventions conducted without an initial intervention in the ED (Mello, et al., 2008). The goal of the first booster call (B1) was to re-engage the participant, reinforce the change plan originated in the ED, explore potential barriers to change, and support continuing efforts at change. The goal of the second booster call (B2) was to check-in and address barriers to treatment engagement. To provide continuity, the same booster counselor was assigned to make both calls to a given participant.

The target window for B1 was within 3 days of discharge from the ED, and for B2 within 7 days of discharge; however, booster counselors had a 30 day window to complete both calls. Booster counselors were instructed to make any reasonable attempt to locate participants and invite them to complete the B1 and B2 sessions. This often involved attempting to contact participants during early morning or evening hours and on weekends, which required booster counselors to be flexible and accommodate different time zones. If unable to contact the participant directly, booster callers contacted the previously identified locators to attempt locating and subsequently contacting the participant. Each counselor had a cell phone to make and receive calls at any time from any location. The cell phone was programmed with a toll-free phone number that participants could use to return calls to the counselor.

2.4. Suicide Plan

Given the increased risk associated with substance users, the University of Washington IRB required that the centralized Booster Call Center have a suicide plan in the event that a participant expressed suicidal ideation during the booster call. Booster counselors were trained to assess the situation for level of risk, and to develop a plan with the participant. Booster counselors were instructed to call 911 if the suicide risk was imminent. Because the booster call center was centralized and not local to participants at any of the study sites, special planning occurred around the use of 911 resources. Specifically, each local ED site provided the Booster Call Center with the phone number to use when accessing a given locale’s 911 service from out of area. When making booster calls, counselors had ready a suicide plan containing these access numbers and other local treatment and emergency resources, along with access to a second phone in the event that they had to call 911 while keeping the participant on the phone.

2.5. Booster Call Assignment

Participants randomized to BI-B were manually assigned to a booster counselor once the enrollment process was completed in the centralized data capture system. The data capture system generated an automatic email to the Booster Call Center notifying the designated Project Director that a participant had been randomized to BI-B. The Project Director or designee then assigned that person to a booster counselor via email notification. Care was taken to assign based on a pre-established rotation that included flexibility for booster counselors’ vacations or other absences.

2.6. Documentation

Because of the nature and scope of this study, considerable preparation was required before each call. Booster counselors prioritized thorough documentation to track their work. Each counselor had three sets of documentation: 1) a notebook which served as the central source document for recording participant assignment, information about call attempts, who answered, when was the best time to call, the participant’s situation, and anything else that was deemed useful for the task; 2) a formal call tracking log for each participant, which served as study documentation of every call attempted to either the participant or his/her locators, including date, time, length of call, and outcome; and 3) booster session clinical notes, which were a summary of the actual B1 or B2 intervention. Booster session notes were entered into the centralized data capture system and were available to research staff at the site where the participant was enrolled, whereas booster callers’ notebooks and tracking logs were source documents for their own use. The tracking log was initially thought to be sufficient for booster callers’ needs, but they found that a notebook offered more space and freedom to record information.

2.7. Variables and Data Analysis

Call-related data were recorded into an electronic data capture system by ED research staff and booster counselors. Quantitative variables used in the present analysis included: number of completed B1 and B2 calls, number of call attempts needed to complete B1 and B2, length of calls (minutes), number of calls made before giving up on B1 and B2, number of calls made beyond the 30-day window, and the study day that B1 and B2 were completed. The number of calls made to locators was also included. Descriptive statistics in SPSS were used to characterize this data.

Formal qualitative data analytic methods were not used in the evaluation of booster callers’ perceptions of possible barriers. To address barriers to booster call completion, the authors, who include the three booster call counselors (Phares, McGarry, Taborsky) and three study investigators (Donovan, Hatch-Maillette, Peavy), met weekly over the course of 2 months post-trial to brainstorm a list of operational challenges that the study team encountered and solved over the life of the study. The booster counselors, with reference to their call logs, notebooks, and clinical session notes, readily recollected barriers to call completion. Co-authors Hatch-Maillette and Peavy then led the team in grouping the barriers into categories until consensus had been obtained.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

In total, 14,972 patients across the six EDs completed a brief screen of alcohol, drug, and tobacco use. Of these 1295 provided written informed consent and 1285 were randomized, with 425 individuals randomized to the BI-B arm. This latter group was the target for the booster calls, and consisted of 70% males, 23% Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 48% Caucasian with an additional 34% Black/African American. The average age was about 36 (SD = 12); 63% had a 12th grade education or less. Only 24% were employed full time in the 30 days prior to their ED visit, while 37% were unemployed during that time period; and 63% had an annual income less than $15,000. The most commonly reported primary drugs of use were cannabis (44%), cocaine (26%), street opiates (18%), and prescription opiates (5%). They reported an average of 15.7 (SD = 11.5) days of use of their primary drug in a 30 day period. They had a mean score of 5.76 (SD = 2.26) on the DAST-10 and 5.54 (SD = 3.72) on the AUDIT-C. The BI-B group did not differ on any of these demographic characteristics from the other two conditions to which participants were randomized.

3.2. Characteristics of 1st and 2nd Booster Calls

Table 1 displays descriptive data regarding the first (B1) and second (B2) booster calls. Of the total sample of 425 BI-B participants, over half (n=239; 56.2%) completed a B1 call. The number of call attempts needed to complete a B1 ranged from one to nineteen, with a mean of 4.9 (SD = 3.8). This number only includes calls to the participant, and not to locators. The target length of the B1 call was 20 minutes, though it ranged from four to forty-six minutes with a mean of 21.8 minutes (SD = 7.0). Booster counselors averaged 11.4 (SD = 5.2) call attempts before giving up on trying to complete a B1 call (range = 1–30).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1st and 2nd booster calls

| Booster Call Variables | 1st Booster Call (B1) | 2nd Booster Call (B2) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants out of total sample (N = 425) who received call | 239/425 (56.2%) | 160/425 (37.7%) (66.9% of the 239 who received B1) |

| Number of calls needed to complete contact | 4.9 (SD = 3.8) (Median = 4) |

3.7 (SD = 3.4) (Median = 3) |

| Number of days from enrollment to completed call | 8.2 (SD = 7.6) (Median = 6) |

16.2 (SD = 9.5) (Median = 15) |

| Length of completed calls in minutes | 21.8 (SD = 7.1) (Median = 22) |

22.1 (SD = 8.5) (Median = 21) |

| Number of calls made before giving up on further attempts | 11.4 (SD = 5.2) (Median = 11) |

5.8 (SD = 4.0) (Median = 5) |

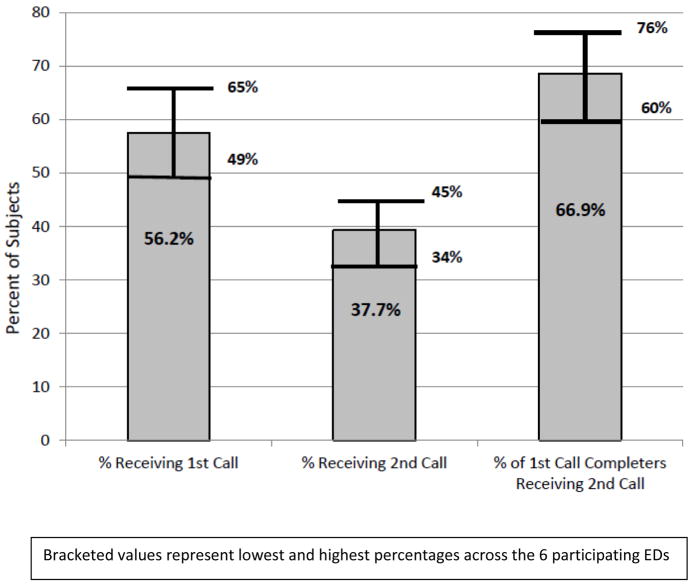

The majority of participants who completed B1 went on to complete B2. Of the 239 participants who completed a B1 and were thus eligible for B2, 160 (66.9%) completed a B2 call. On average, 3.6 call attempts (range = 1–28, SD = 3.4) were needed (not including calls to locators) to complete the B2 call, and they lasted 22.1 minutes (range = 5–54, SD = 8.5). Booster counselors averaged 5.7 call attempts before giving up on trying to complete a B2 call (range = 0–23, SD = 4.0)1. Figure 1 displays the percent of the total sample that completed B1 and B2.

Figure 1.

Percent of Total Sample Completing 1st and 2nd Booster Calls, and Percent of Those Receiving 1st Call who Completed 2nd Call

Bracketed values represent lowest and highest percentages across the 6 participating EDs

3.2.1. Locator Calls

Of a total number of 378 BI-B patients with available call tracking logs (89% of total sample of 425, with 47 missing), 217 patients (57% of 378) had locators called, 161 did not. Of those who had locators called, the average number of calls to the locator(s) was 4.1 (range of calls = 1 to 13). It was noted that the booster counselor who called the most locators, the most times had the highest overall participant call completion rate, while the booster counselor who called the fewest locators, the fewest number of times had the lowest. Although anecdotal, this suggests that there is a relationship between contacting locators and completing the booster calls.

3.2.2. Fidelity of Completed Booster Calls

Completed booster calls to participants were conducted with a high degree of fidelity to the MI approach. A total of 83 booster sessions (20%) were MITI-coded across five dimensions (evocation, collaboration, autonomy, direction, and empathy). On a scale of one to five, mean global scores for the booster sessions ranged from 4.64 (SD = 0.51) to 4.86 (SD = 0.39). A global score of 4.0 represents proficiency, so these scores indicate that the overall quality of the booster call intervention was quite high.

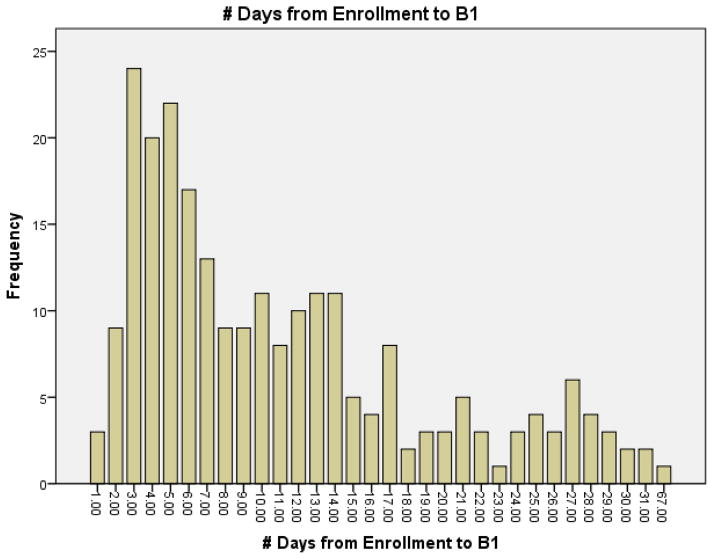

3.2.3. Call Completion Patterns

Figure 2 displays the frequency of B1 calls completed for each day post-study enrollment in the ED. The data illustrate that the approximately 45% of calls were completed within the first 7 days after discharge. The second week after discharge was still productive with an additional 29% of the B1 calls completed, while the success rate dropped substantially again over the third and fourth weeks post-discharge. The mean number of days from enrollment for completing B1 calls was 11.2 (SD = 8.6), with a median of 9.0 and a mode of 3.0.

Figure 2.

Number of Days from Enrollment to Completion of B1

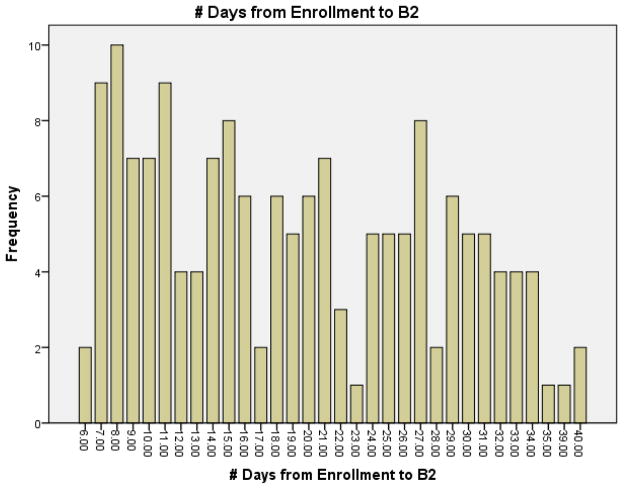

Similarly, Figure 3 shows the frequency of B2 calls completed post-enrollment. Booster counselors were most likely to successfully reach participants for their second booster call toward the end of the week following discharge, with Day 8 representing the modal day. There appeared to be a general trend of decreasing likelihood of completing the B2 as the month wore on, with a sharp drop off after Day 34. However, booster counselors reached the same number of participants on Days 12 and 13 as they did on Days 32, 33, and 34. Overall, the mean number of days from enrollment to completing B2 for those participants receiving the second call was 19.2 days (SD = 8.9), with a range from 6 to 40 days and a median of 18.0 days.

Figure 3.

Number of Days from Enrollment to Completion of B2

3.3. Impact of Financial Incentive Impact Call Completion Rate

As noted previously, booster calls conducted during the training phase for ED and booster call counselors were incentivized, with participants receiving $30 for each completed call, whereas participants in the main phase of the study were not reimbursed for completed calls. Twenty-nine pilot participants were assigned to the booster counselors for post-ED visit phone calls. Of these, 21, or 72.4%, completed a B1. Of those 21 who received a B1, 19 (90.4%) completed a B2. These call completion rates are much higher than for the main phase study participants (56.2% got a B1, and 66.9% of those got a B2). The difference in the percentages of B1 calls completed were significant (Z = 1.844, p = 0.036, 1-tailed), as were the differences in the completion rates for the B2 calls (Z = 3.237, p = .0006).

3.4. Suicidality

Although booster counselors were prepared with a suicide protocol and suicidal ideation was occasionally discussed, no calls to emergency services were needed over the course of the study.

4. Discussion

This paper reviewed the methods used in successfully implementing a centralized, remote booster call center embedded within a randomized controlled trial testing the SMART-ED protocol. The purpose of the paper was to describe the process of implementing this type of system. To do so, data from the booster callers describing what they did to ensure the highest likelihood of a completed booster call intervention were used. To our knowledge, this is the only work describing this process and outlining associated barriers. As such, we believe that it can instruct others embarking on similar research and clinical endeavors. Here, we discuss our results and conclude by proposing a series of recommendations.

Booster interventionists demonstrated persistence and effort in reaching participants. While other investigators working in ED and trauma center settings have reported higher booster call rates when working with hazardous drinking (D’Onofrio, et al., 2012; Monti et al., 2007), the 56.2% and 66.9% contact rates for the initial and second booster calls achieved in this study targeting primary drug use is noteworthy, particularly in light of the myriad challenges booster callers encountered when attempting to contact research participants. However, despite what a well-organized, committed and persistent team, the absolute call completion rates were still low.

Studies using booster calls in ED settings typically have not reported their completion rates. Studies using booster calls in primary care and non-emergent settings have reported call completion rates, though they are lower than those in the current study. For example, among a group of cocaine and heroin users identified while presenting for routine care of non-acute health problems in walk-in medical clinics of an urban teaching hospital, only 31% of participants in the intervention group could be reached by phone 10 days after their visit (J. Bernstein et al., 2005). In a study of at-risk drinkers seen in primary care clinics of a health maintenance organization (Curry, et al., 2003), participants having received a physician administered brief intervention were scheduled to receive 3 follow-up MI booster calls at 1–2 weeks after their clinic appointment, within 4 weeks after the first call, and within 4 weeks after the second call. While 84% of participants reported having received one call, there was a marked drop-off in completions of the second and third calls. Only 27% of the participants had completed at least two calls, and even fewer (18%) had completed all three calls (Curry, et al., 2003).

4.1. Lessons Learned

Barriers to contacting research participants are well known to researchers engaging in follow up interviews with hard to reach populations (Hansten, Downey, Rosengren, & Donovan, 2000; Patton, Slesnick, Bantchevska, Guo, & Kim, 2011); however, we are unaware of studies in which the barriers to booster calls have been documented.

Five categories of barriers to reaching or completing booster calls with participants emerged from the examination and review of notes from booster counselors throughout the study, supervision sessions, and team meetings. Some of these are fairly typical of those encountered when initiating follow-up contact with research participants, while others were more specific to the nature of booster interventions. The five barriers identified were unstable housing, limited phone access, unavailability due to additional treatment, lack of compensation, and the booster caller being someone other than ED staff. Taken together, these barriers presented a real and daily challenge to completing booster contacts as outlined in the study protocol. Attempting to track people who have no primary place of residence because they are homeless, or living in shelters or with friends or family, was extremely difficult. Such instability made participants’ personal cell phones even more important, yet this population often did not have cell phones or very frequently ran out of minutes or had their phones turned off due to unpaid bills. Yet, a few days or weeks later, more minutes might have been added, a bill might have been paid and they might be reachable again.

Participants might also be unavailable for booster follow-ups due to another hospitalization or admission to inpatient treatment. Such unavailability might last a few days or a few months, which accounted for the one outlier in the distribution whose B1 call was completed at day 67 post-ED visit. Relatedly, participants might be difficult to find because the name under which they were admitted for secondary treatment was different from the name they used for study enrollment. In some cases participants also expressed reluctance to take time for a booster follow-up if no participant reimbursement was available, given that they were being compensated for their time for other research visits. Booster counselors found that participants were sometimes confused and suspicious at receiving phone calls from a booster call center geographically removed from them, with a different area code, and by a study staff member who was not part of their local ED where they had enrolled. Finally, some participants and locators expressed exasperation with “too many calls” coming from multiple study staff (e.g. research staff for follow-up visits and booster counselors for the booster calls).

4.2. Recommendations

All of the barriers reinforced the conclusion that conducting booster contacts is a significant undertaking and requires a resource investment of planning, staffing, and time. Based on our experiences, we summarize here the lessons learned from our experiences in the form of five recommendations for others launching similar efforts.

4.2.1. Preparedness

Safety planning and overall call preparedness are required. As with any telephone intervention, the caller needs to make or receive the call in a quiet and private place, and have all necessary intervention materials close by. Because booster interventionists were located in different states, jurisdictions, and even time zones from the participants they were calling, some special considerations needed to be made to ensure that high risk situations (i.e., suicidal or homicidal ideation) could be managed appropriately. Although it was not necessary for us to employ our suicide protocol, extra, but necessary, steps were needed in anticipation and preparation for such situations. We recommend that booster callers have the following in hand prior to making or receiving an intervention call: emergency numbers specific to the participants’ city, local hospital numbers and other referral contacts, as well as a second phone available (silenced) with which to make an additional emergency call while keeping the participant on the original line. A system of documentation for tracking call attempts and pertinent information for each participant is also recommended. This may be a notebook and/or a standardized call log in which booster call attempts and participant availability notes are recorded. Separate from centralized, formal data collection required for the clinical trial, which included date and time of completed calls and session notes, these booster call logs and notebooks proved invaluable in guiding individual booster caller efforts to reach participants, as well as providing a record of these efforts overall for later inquiry.

Preparedness also relates to maximally streamlining call procedures. Between ED staff attempting to reach participants for follow-up visits, and booster interventionists attempting to complete the booster calls, participants and locators at times reported “too many calls.” To minimize participant burden, we suggest an effort to be mindful of who all may be trying to contact participants.

4.2.2. Flexibility

The population examined for this study represented a diverse group of substance abusers; the sample spanned six states, participants initially presented to the ED for a wide range of problems not necessarily related to substance use, and they reported the gamut of substance use and other psychosocial problems. In order to respond to such a diverse group, booster interventionists needed to be flexible and possess strong therapeutic skills with an emphasis on MI. For example, it was our experience that booster interventionists greatly increased the likelihood of a connection if they were willing to make calls during off hours (including early mornings to bridge the time zone gap) and on the weekends. Participants who used free government issued cell phones or other limited cell phone plans were restricted to free minutes on nights and weekends, and therefore they were most willing to accept phone calls and complete the intervention during those times. To facilitate this needed flexibility, booster callers used project-dedicated cell phones, each with toll-free return numbers, and laptops with direct access to the internet and the secure, encrypted electronic data system.

In addition to scheduling, booster interventionists also needed to have flexible expectations regarding how the call proceeded. Participants were non-treatment seekers with various levels of openness to speaking on the phone with the interventionist, let alone engaging in the intervention. Telephone counseling also presents challenges often not found in face-to-face interventions (e.g., background noises, interruptions from other people or phone calls, participants attempting to “multi-task” during calls). Booster interventionists were challenged to limit the phone conversation to the target length because of the complexity of participants’ lives. We suggest that intervention staff be chosen based on their clinical skills (i.e., ability to build rapport quickly and “roll with resistance”) and willingness to keep flexible schedules.

4.2.3. Interventionist Staffing, Skill, Training, Supervision

Existing clinical skills are an important attribute for booster interventionists. Relatedly, the availability of clinical supervisors and MI trainers is just as important. Since booster interventionists face multiple barriers in getting participants on the phone and engaged in the intervention, the work itself can feel unrewarding at times. Furthermore, if interventionists work in isolation, making calls from their home offices rather than within a clinic setting, face-to-face supervision becomes even more worthwhile for debriefing and support. Regularly scheduled supervision also helped interventionists adhere to treatment standards, and allowed for trading information to increase the connection rate between interventionists and participants. Logistically, such face-to-face meetings also facilitated planning around issues of coverage - both expected (e.g., vacations) and unexpected (e.g. sudden illness or injury requiring extended absence from work). It was initially thought that for six ED sites, two booster counselors would provide adequate coverage in the event of vacation or illness. However, we found that was insufficient; if one interventionist was absent, the full load of new- and currently-enrolled booster-eligible participants was too burdensome for the remaining interventionist. A third booster counselor was therefore hired. Based on all of these factors, we recommend the presence of an experienced MI practitioner to serve as trainer and supervisor to the interventionist team, as well as sufficient administrative support or oversight to manage coverage issues. Moreover, we emphasize the importance of regular consultation meetings among team members and their supervisors to troubleshoot problems and provide support and validation to one another.

4.2.4. A Warm Hand-Off

Booster interventionists noted the importance of a “warm hand-off” from the ED. That is, the ED interventionists prepared the participants to expect a booster call and warned participants that the call would come from an out of state area code from someone other than ED staff. This kind of preparation helped mitigate some of the resistance and suspiciousness booster callers encountered among participants. ED staff members were also responsible for acquiring locator information from participants and providing a detailed summary of the participant’s ED visit. It was our experience that ED staff played a critical role in facilitating the connection and completion of the booster calls by “prepping” participants about what to expect next (i.e., receiving a booster call). Also, interventionists relied on the ED-provided summary to prepare for their calls. We recommend establishing a strong working relationship with the staff and administrators located at the site of the participant’s last contact before booster calls. Also, it may be useful in future studies to have the ED staff trigger a call from the call center following the initial intervention and prior to the participant leaving the ED, ensuring that the participant would recognize the study phone number when future attempts would be made at completing booster calls.

4.2.5. Allow a Sufficient Window

Our data indicate a bimodal distribution of number of days between expected and actual intervention dates, such that the connection rates were highest towards the beginning and the end of the 30-day window. This indicates that if the intervention was to happen, participants were typically reached either shortly after their ED visit, as planned, or very near 30 days after enrollment. This finding has two implications. In other words, if at first you don’t succeed, keep trying. We recommend a follow-up window of at least 30-days, to allow time for circumstances to change for the participants (e.g. cell phone minutes are reloaded, participants make contact with their locators, seemingly unreachable people re-surface, etc.). We also suggest that future researchers examine whether a longer follow up period may yield even more favorable results.

4.2.6. Consider Incentives

Lack of compensation was stated as a reason for declining booster calls by some participants. The higher rate of completed booster calls among pilot participants, who were compensated for booster calls, suggests that incentives mattered.

4.3. Limitations

While providing the booster callers’ and the research team members’ perspectives on factors that contributed to difficulties in call completion, this was not a formal qualitative study and did not employ qualitative analytic methods. It was based on the observations derived from examination and review of notes from booster counselors throughout the study, supervision sessions, and team meetings. Future efforts might attempt to conduct focus groups with individuals or structured interviews with individuals who accepted the calls to determine the reasons for doing so. While it might be equally or more informative to gain information about reasons for not accepting the booster calls, it is equally unlikely that it would be possible to contact and engage this group.

4.3. Future Directions

In addition to these recommendations, our experience with implementing the booster call center led us to consider emerging issues and future research questions related to this process. First, through participant feedback it became clear that guidelines are needed regarding the use of texting, social media and other potential emerging technologies to communicate with research participants. Second, as noted above, lack of remuneration for completing booster interventions was a barrier to completing intervention calls, while evidence indicates that providing financial incentives can lead to high rates of call completion (Monti, et al., 2007). These findings suggest the possibility of developing and examining the use of vouchers or other incentives in a contingency management (CM) component to the booster intervention. CM has a strong evidence base for treating addictive behaviors (Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger, & Higgins, 2006; Prendergast, Podus, Finney, Greenwell, & Roll, 2006), yet it remains unexamined in the context of brief interventions with or without booster calls. It will be important to find out more information about individuals who did not complete booster interventions and how they compare to those who completed the calls. For example, our team has hypothesized that high utilizers of social services were also those likely to complete the intervention calls. While this prediction is based on anecdotal evidence (interventionists’ interactions with callers), these types of clinical phenomena can be the catalyst for future empirical inquiry. Determining who answers the phone and completes a booster counseling session, versus who does not, will help researchers consider ways to engage the harder to reach people, and better target the intervention.

Finally, the effectiveness and benefit of booster sessions needs to be determined. While a number of studies have employed booster calls following trauma center or ED visits, few have evaluated their effectiveness or relative contributions to substance use outcomes. Longabaugh and colleagues (Crawford et al., 2004; Longabaugh, et al., 2001; Mello et al., 2005) randomized hazardous and harmful drinkers seen in the ED, including a subset of these patients who were involved in motor vehicle accidents, to a brief motivational intervention either with or without a subsequent face-to-face booster appointment 7–10 days following the ED visit. Patients receiving the intervention that included the booster session had significantly greater reductions in alcohol-related negative consequences and injuries compared to those randomized to the brief motivational intervention without a booster. In contrast to this positive finding and contrary to their own hypothesis, D’Onofrio and colleagues (D’Onofrio, et al., 2012) found no incremental benefit of a brief negotiated interview with a follow-up telephone booster session one month post-ED visit over and above that found for the same intervention without a booster in reducing hazardous drinking patterns and impaired driving. Future studies need to evaluate the incremental contributions of booster calls. The most rigorous test would involve using designs that include randomization to receive or not receive a follow-up booster call in conjunction with the same brief motivational interventions delivered in the ED, similar to the studies by Longabaugh (Longabaugh, et al., 2001) and D’Onofrio (D’Onofrio, et al., 2012). If randomization is not possible, then secondary analyses of the alcohol or drug use outcomes of those having completed versus not having completed a booster call(s) would be informative.

5 Conclusions

The results of our inquiry demonstrate that a team of booster interventionists and supporting staff can overcome the challenges in implementing a remotely located, centralized booster call center. This paper was, in part, born out of a need for guidelines during our own implementation process. There is a decidedly small body of literature covering booster interventions, and nothing that specifically describes the process. The only other areas of research from which one might be able to glean information is that of Quitlines in smoking cessation research (Cummins, Bailey, Campbell, Koon-Kirby, & Zhu, 2007; Lichtenstein, Zhu, & Tedeschi, 2010) and telephone therapy as continuing care for substance abuse (J.R. McKay & Hiller-Sturmhöfel, 2011; J.R. McKay, Lynch, Shepard, & Pettinati, 2005; J.R. McKay et al., 2004). While helpful, these areas do not address the specific problem areas faced by telephone-based booster interventions. For example, “continuing care” by its very nature is an extension of a treatment episode in which, theoretically, the client was already engaged. Most smoking cessation Quitline sessions are initiated by the individual smoker who desires to quit. Both of these models are much different from the one represented by booster interventions in which the individual may not be motivated to talk on the phone or engage in an intervention. While booster calls are gaining traction in terms of their use as an adjunct to SBIRT and appear potentially promising, both the incremental contribution of such adjunctive calls to overall treatment outcome and their relative cost effectiveness merit continued research.

Table 2.

Barriers to Booster Call Completion: Lessons Learned and Recommendations

| Barriers to Booster Call Completion | |

|---|---|

| Lessons Learned | Recommendations |

| Unstable housing | Preparedness |

| Limited phone access | Flexibility |

| Unavailability due to additional treatment | Interventionist skill, training, supervision |

| Lack of compensation for call completion | Warm hand-Off |

| Booster caller unknown to the participant | Allow a sufficient window |

| Consider incentivizing all completions | |

Highlights.

Booster calls are being used adjunctively to support brief interventions

Call completion rates are relatively low but may be increased by use of locators

Five prominent barriers to call completion were identified

Once completed, brief motivational sessions can be delivered with high fidelity

Skilled staff, preparedness, flexibility, and a warm hand off are important

Future research need to determine boosted call contribution to outcomes

Future research needed to determine cost benefit of booster calls in SBIRT programs

Acknowledgments

The present paper is based on a component of a multisite clinical trial, Screening, Motivational Assessment, Referral, and Treatment in Emergency Departments (SMART-ED; NIDA CTN Protocol 0047), conducted within the National Institute on Drug Abuse National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN). Its preparation was supported by Grant # 5U10DA013714, Clinical Trials Network: Pacific Northwest Node, Dennis Donovan, PI.

Footnotes

The range for this variable includes zero because a few participants were inadvertently dropped due to one booster counselor going on unplanned medical leave for part of the study, which necessitated hiring a third counselor and re-assigning participants.

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative. The impact of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment on Emergency Department patients’ alcohol use. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007;50(6):699–710. e696. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative. The impact of screening, brief intervention and referral for treatment in emergency department patients’ alcohol use: A 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2010;45(6):514–519. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, McRee BG, PAK, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, Bray J. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT): Toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Substance Abuse. 2007;28(3):7–30. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Apodaca TR, Magill M, Colby SM, Gwaltney C, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM. Moderators and mediators of two brief interventions for alcohol in the emergency department. Addiction. 2010;105(3):452–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Bernstein J. Effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief motivational intervention in the Emergency Department setting. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2008;51(6):751–754. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Edwards E, Dorfman D, Heeren T, Bliss C, Bernstein J. Screening and brief intervention to reduce marijuana use among youth and young adults in a pediatric emergency department. Academy of Emergency Medicine. 2009;16(11):1174–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, Heeren T, Levenson S, Hingson R. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J, Heeren T, Edward E, Dorfman D, Bliss C, Winter M, Bernstein E. A brief motivational interview in a pediatric emergency department, plus 10-day telephone follow-up, increases attempts to quit drinking among youth and young adults who screen positive for problematic drinking. Academy of Emergency Medicine. 2010;17(8):890–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G, Grothues JM, Reinhardt S, Meyer C, John U, Rumpf HJ. Evaluation of a telephone-based stepped care intervention for alcohol-related disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93(3):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschutz MP, Donovan DM, Adinoff B, Crandall C, Forcehimes AA, Lindblad R, Walker R. Design of NIDA CTN Protocol 0047: Screening, motivational assessment, referral, and treatment in emergency departments (SMART-ED) The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(5):417–425. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(7):1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y. Drug use and problem drinking associated with primary care and emergency room utilization in the US general population: Data from the 2005 national alcohol survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97(3):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MJ, Patton R, Touquet R, Drummond C, Byford S, Barrett B, Henry JA. Screening and referral for brief intervention of alcohol-misusing patients in an emergency department: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2004;364(9442):1334–1339. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins SE, Bailey L, Campbell S, Koon-Kirby C, Zhu SH. Tobacco cessation quitlines in North America: A descriptive study. Tobacco Control. 2007;16(Suppl 1):i9–i15. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham RM, Bernstein SL, Walton M, Broderick K, Vaca FE, Woolard R, D’Onofrio G. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs: Future directions for screening and intervention in the emergency department. Academy of Emergency Medicine. 2009;16(11):1078–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ, Ludman EJ, Grothaus LC, Donovan D, Kim E. A randomized trial of a brief primary-care-based intervention for reducing at-risk drinking practices. Health Psychology. 2003;22(2):156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, Degutis LC, O’Connor PG. A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2012;60(2):181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeppen JB, Gaume J, Bady P, Yersin B, Calmes JM, Givel JC, Gmel G. Brief alcohol intervention and alcohol assessment do not influence alcohol use in injured patients treated in the emergency department: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Addiction. 2007;102(8):1224–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz FJ, Jané M, Saltó E, Pardell H, Salleras L, Pinet C, de Leon J. A brief measure of high nicotine dependence for busy clinicians and large epidemiological surveys. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39(3):161–168. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Bogenschutz MP, Perl H, Forcehimes A, Adinoff B, Mandler R, Walker R. Study design to examine the potential role of assessment reactivity in the Screening, Motivational Assessment, Referral, and Treatment in Emergency Departments (SMART-ED) protocol. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2012;7(16) doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-16. Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Rosengren DB, Downey L, Cox GB, Sloan KL. Attrition prevention with individuals awaiting publicly funded drug treatment. Addiction. 2001;96(8):1149–1160. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96811498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin D, Ross H, Skinner H. The diagnostic validity of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in the assessment of DSM-III drug disorders. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84:301–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, Jurkovich GJ, Daranciang E, Dunn CW, Ries R. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Annals of Surgery. 1999;230(4):473–480. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansten ML, Downey L, Rosengren DB, Donovan DM. Relationship between follow-up rates and treatment outcomes in substance abuse research: More is better but when is “enough” enough? Addiction. 2000;95(9):1403–1416. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.959140310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, Farrell M, Formigoni ML, Jittiwutikarn J, Simon S. Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103(6):1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korcha RA, Cherpitel CJ, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G, Bond J, Ye Y. Readiness to change, drinking, and negative consequences among Polish SBIRT patients. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(3):287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Baird J, Longabaugh R, Nirenberg TD, Mello MJ, Woolard R. Change plan as an active ingredient of brief motivational interventions for reducing negative consequences of drinking in hazardous drinking emergency-department patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71(5):726–733. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leontieva L, Horn K, Haque A, Helmkamp J, Ehrlich P, Williams J. Readiness to change problematic drinking assessed in the emergency department as a predictor of change. Journal of Critical Care. 2005;20(3):251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein E, Zhu SH, Tedeschi GJAP. Smoking cessation quit lines: An underrecognized intervention success story. 2010;65(4):252–261. doi: 10.1037/a0018598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Minugh PA, Nirenberg TD, Clifford PR, Becker B, Woolard R. Injury as a motivator to reduce drinking. Acadamy of Emergency Medicine. 1995;2(9):817–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Woolard RE, Nirenberg TD, Minugh AP, Becker B, Clifford PR, Gogineni A. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(6):806–816. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Strang J. The efficacy of single-session motivational interviewing in reducing drug consumption and perceptions of drug-related risk and harm among young people: results from a multi-site cluster randomized trial. Addiction. 2004;99(1):39–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Strang J. Deterioration over time in effect of Motivational Interviewing in reducing drug consumption and related risk among young people. Addiction. 2005;100(4):470–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. Telephone-based conmtinuing care -- A novel approach to adaptive continuing care. Alcohol Research and Health. 2011;33(4):366–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Pettinati HM. The effectiveness of telephone-based continuing care for alcohol and cocaine dependence: 24-month outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(2):199–207. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Ratichek S, Morrison R, Koppenhaver J, Pettinati HM. The effectiveness of telephone-based continuing care in the clinical management of alcohol and cocaine use disorders: 12-month outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):967–279. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello MJ, Longabaugh R, Baird J, Nirenberg T, Woolard R. DIAL: A telephone brief intervention for high-risk alcohol use with injured emergency department patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2008;51(6):755–764. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello MJ, Nirenberg T, Woolard R, Baird J, Longabaugh R. 316: DIAL: A Telephone Intervention for High-Risk Alcohol Use With Injured ED Patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007;50(3, Supplement 1):S99–S99. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello MJ, Nirenberg TD, Longabaugh R, Woolard R, Minugh A, Becker B, Stein L. Emergency department brief motivational interventions for alcohol with motor vehicle crash patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2005;45(6):620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Tonigan JS. Motivational interviewing in drug abuse services: a randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(4):754–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, Diclemente CC, Rychtarik RG. Motivational enhancement therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Vol. 2. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Minugh PA, Nirenberg TD, Clifford PR, Longabaugh R, Becker BM, Woolard R. Analysis of alcohol use clusters among subcritically injured emergency department patients. Acadamy of Emergency Medicine. 1997;4(11):1059–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Woolard R. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007;102(8):1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P, Baird J, Mello MJ, Nirenberg T, Woolard R, Bendtsen P, Longabaugh R. A systematic review of emergency care brief alcohol interventions for injury patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35(2):184–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton R, Slesnick N, Bantchevska D, Guo XM, Kim YCMHJ. Predictors of follow-up completion among runaway substance-abusing adolescents and their primary caretakers. 2011;47(2):220–226. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9281-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101(11):1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett IRH, Putnam SL, Jia H, Chang CF, Smith GS. Unmet substance abuse treatment need, health services utilization, and cost: A population-based emergency department study. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2005;45(2):118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett IRH, Putnam SL, Jia H, Smith GS. Assessing substance abuse treatment need: A statewide hospital emergency department study. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2003;41(6):802–813. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7(4):363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom CA, DiClemente CC, Dischinger PC, Hebel JR, McDuff DR, Auman KM, Kufera JA. A controlled trial of brief intervention versus brief advice for at-risk drinking trauma center patients. Journal of Trauma Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2007;62(5):1102–1112. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31804bdb26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers MS, Dyehouse JM, Howe SR, Fleming M, Fargo JD, Schafer JC. Effectiveness of brief interventions after alcohol-related vehicular injury: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Trauma Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2006;61(3):523–531. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000221756.67126.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LA, Minugh PA, Longabaugh R, Wirtz P, Baird J, Nirenberg TD, Gogineni A. Readiness to change as a mediator of the effect of a brief motivational intervention on posttreatment alcohol-related consequences of injured emergency department hazardous drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(2):185–195. doi: 10.1037/a0015648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2010 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) findings on drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k12/DAWN096/SR096EDHighlights2010.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn DHA, Drapkin M, Ivey M, Thomas T, Domis SW, Abdalla O, McKay JR. Voucher incentives increase treatment participation in telephone-based continuing care for cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114(2–3):225–228. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MA, Goldstein AL, Chermack ST, McCammon RJ, Cunningham RM, Barry KL, Blow FC. Brief alcohol intervention in the emergency department: Moderators of effectiveness. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(4):550–560. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S, Brown A, Patton R, Crawford MJ, Touquet R. The half-life of the “teachable moment” for alcohol misusing patients in the emergency department. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77(2):205–208. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]