Abstract

Feasibility studies play a crucial role in determining whether complex, community-based interventions should be subject to efficacy testing. Reports of such studies often focus on efficacy potential but less often examine other elements of feasibility, such as acceptance by clients and professionals, practicality, and system integration, which are critical to decisions for proceeding with controlled efficacy testing. Although stakeholder partnership in feasibility studies is widely suggested to facilitate the research process, strengthen relevance, and increase knowledge transfer, little is written about how this occurs or its consequences and outcomes. We began to address these gaps in knowledge in a feasibility study of a health intervention for women survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) conducted in partnership with policy, community and practitioner stakeholders. We employed a mixed-method design, combining a single-group, pre-post intervention study with 52 survivors of IPV, of whom 42 completed data collection, with chart review data and interviews of 18 purposefully sampled participants and all 9 interventionists. We assessed intervention feasibility in terms of acceptability, demand, practicality, implementation, adaptation, integration, and efficacy potential. Our findings demonstrate the scope of knowledge attainable when diverse elements of feasibility are considered, as well as the benefits and challenges of partnership. The implications of diverse perspectives on knowledge transfer are discussed. Our findings show the importance of examining elements of feasibility for complex community-based health interventions as a basis for determining whether controlled intervention efficacy testing is justified and for refining both the intervention and the research design. © 2015 The Authors. Research in Nursing & Health published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, women's, health, intervention, feasibility study, partnership, primary health care, community

Partnerships among researchers, practitioners, community advocates and policy makers in the conduct of feasibility studies facilitate the research process, enhance intervention pertinence to community and practice realities, and boost knowledge transfer (Bowen et al., 2009; Chesla, 2008). Feasibility studies are a critical first step in determining whether an intervention should be subject to efficacy testing, such as in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Bowen et al., 2009). When an intervention is community-based, focuses on health promotion, or involves changes to health service delivery, the standardization required for an RCT is difficult to achieve (Blackwood, 2006; Campbell et al., 2007; Buckwalter et al., 2009; Green & Glasgow, 2006). Yet, little is written about the process, outcomes and challenges of feasibility studies conducted in partnership with community stakeholders.

Feasibility studies explore intervention-specific issues, such as research methods and protocols, context-specific relevance and practicality, and efficacy potential (Bowen et al., 2009; Craig et al., 2008), but undue emphasis is commonly placed on efficacy potential in feasibility reports (Becker, 2008).1 Lessons regarding other aspects of feasibility, such as practicality or implications for research protocols, are rarely shared. Our purpose here is to address these gaps in the literature by showing the usefulness of a feasibility study when a) the study incorporates meaningful partnerships, and b) feasibility is assessed in terms of acceptability, demand, practicality, implementation, adaptation, integration and efficacy potential (Bowen et al., 2009). To achieve our purpose, we discuss the process, outcomes and challenges of a feasibility study conducted in New Brunswick (NB), Canada, to examine the Intervention for Health Enhancement After Leaving (iHEAL), a primary health care intervention for women recently separated from violent/abusive partners (Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, Varcoe, & Wuest, 2011). Partnerships were central to this feasibility study and included a research team partnership among university researchers and government and non-profit policymakers, community partnerships with domestic violence (DV) stakeholders, and interventionist partnerships between DV outreach workers and registered nurses (RN). This study was initiated by the researchers and is not a community-based participatory study. However, partners at policy, practice and community levels made important contributions at all stages of the research, facilitating ongoing knowledge transfer. Based on our work together, we also consider the evolution of differing meanings of what constitutes useful knowledge to researchers and partners (Brown, 2002).

Health Care of Women Survivors of Abusive Relationships

In NB, as worldwide, intimate partner violence (IPV) is a major public health problem negatively affecting physical and mental health in women (Campbell, 2002; Ellsberg, Jansen, Heise, Watts, & Garcia-Moreno, 2008; Plichta, 2004). Leaving an abusive partner may not stop violence (Campbell, Rose, Kub, & Ned, 1998; Wuest, Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, & Berman, 2003) or improve health (Anderson, Saunders, Yoshihama, Bybee, & Sullivan, 2003). In Canada, we found that women in the early years after leaving had poorer physical and mental health and higher rates of health service use than women in general, with higher annual health system costs by approximately $4,970 Canadian per woman (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2009; Varcoe et al., 2011; Wuest et al., 2007 2008, 2009, 2010).

Although women who experience IPV seek health care at least as often as other women, their abuse history is frequently not identified, and even when it is, they often do not receive the services they need (Plichta, 2007). New Brunswick is a predominantly Caucasian, bilingual (English/French) rural province with a population of ∼750,000 and a few small cities. Primary care is the basic service available to IPV survivors; specialty mental health and trauma services are limited, particularly in rural communities. In this context of fiscal constraints and low population density, implementing best-practice guidelines that call for specialty-level practitioners is often not possible.

Internationally, intervention research is in an early stage of development. The current focus is screening for IPV history when women enter the health care system, followed by context-specific, evidence-based strategies to improve their health, safety and well-being (Decker et al., 2012; Ford-Gilboe, Varcoe, Wuest, & Merritt-Gray, 2011). Community services focusing on safety planning, support and system navigation have been found to improve quality of life and reduce violence exposure after leaving (Ramsay, Rivas, & Feder, ; Sullivan & Bybee, 1999). Interventions focusing specifically on health after leaving are scarce.

Background to Research Partnerships

Longstanding reciprocal relationships and commitment among researchers and the NB health policy and DV sectors facilitated the partnerships vital to this intervention research. Merritt-Gray took part in an intersectoral working group, coordinated by Dubé, to develop a strategic provincial framework to address violence against women (MWGVAW, 2001, 2005Minister's Working Group on Violence against Women, 2001, 2005). A key element of the framework was the establishment of community-based outreach programs province-wide, to provide women with safety planning, emotional support, life-skill training and connection to resources. Nonetheless, the health consequences of violence remained a key source of intrusion for women and raised questions regarding how health care professionals, including RNs, might work with DV outreach workers to address women's health.

During the same period, Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, Varcoe and Wuest (2006) began to develop a nurse-led primary health care intervention for women separated from abusive partners, based on evidence from our ongoing program of research. The social determinants view of health, a foundation of our theoretical work, suggested a collaborative interventionist approach with expertise in both health and DV. Evidence that nurse-led theory-based interventions are effective with at-risk families (Browne, Byrne, Roberts, Gafni, & Whittaker, 2001) supported having an RN as the health interventionist. In NB, we envisioned a partnership of two interventionists, an RN and a DV outreach worker.

A Theory-Driven Intervention

A strong theoretical and empirical base is a requirement for hypothesizing relationships between components of the intervention and its outcomes (Kovach, 2009). It also facilitates examination of the interrelationships among components, characteristics of clients and professionals, context, intervention processes, and outcomes (Craig et al., 2008; Kovach, 2009; Sidani et al., 2003Sidani, Epstein, & Moritz, 2003).

The Intervention for Health Enhancement after Leaving (iHEAL) is based on a grounded theory of health promotion, Strengthening Capacity to Limit Intrusion (SCLI), generated from interviews with survivors of IPV (Ford-Gilboe, Wuest, & Merritt-Gray, 2005; Wuest, Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, & Varcoe, 2013). The SCLI is a theoretical rendering of how survivors of IPV spontaneously promote their health. According to the SCLI, women, after leaving, face pervasive intrusion from ongoing abuse, health problems, restrictive life changes, and “costs” of getting help (Wuest et al., 2003). Over time, women promote their health by strengthening their capacity to limit intrusion, using processes of providing, rebuilding security, regenerating family and renewing self (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2005).

The iHEAL protocol is a practice model in which the SCLI theory is used to draw upon and augment women's knowledge and skills in strengthening capacity to limit intrusion (Wuest et al., 2013). A full discussion of how we drew on the original qualitative data, other salient research, and expert practice philosophies to develop the iHEAL can be found in Wuest et al. (2013). In Table 1, we specify the philosophical orientation of the intervention, guiding principles, and the structure (Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Intervention Protocol for Health Enhancement after Leaving (iHEAL)a

| Goal | To improve women's quality of life and health after leaving an abusive partner by enhancing women's capacity and reducing intrusion. | |

| Type | A theory-based, primary health care intervention provided in partnership by a Registered Nurse (RN) generalist and domestic violence (DV) support worker. | |

| Duration | 12 to 14 individual meetings with the RN (80%) or DV support worker (20%) over 6 months. | |

| Philosophical Orientation | Health is socially-determined, harm reduction, feminism, advocacy, trauma-informed care, social justice, cultural safety. | |

| Guiding Principles | Safety first, health as priority, women-centered, strengths-based, learning from other women, woman in context, calculated risks necessary, limit costs, active system navigation, and advocacy. | |

| Structure | A 3-phase relational process to listen and validate the woman's experience, priorities and strengths, support her in reframing the effects of abuse, and in an active problem-solving partnership, engage her in building her skills, knowledge and resources. Together, women and interventionists engage in: | |

| Phase 1 (2–4 sessions): Getting in Sync | Building mutual trust by discussing a woman's priorities and survival context, nature of the iHEAL and the intrusion theory, and planning their work together. | |

| Phase 2 (8–10 sessions): Working Together | For each component, in order of a woman's priorities (Safeguarding, Managing Basics, Managing Symptoms, Cautious Connecting, Renewing Self, Regenerating Family):

|

|

| Phase 3 (1–3 sessions): Moving On | Reinforcing strengths, reviewing progress, highlighting her resources, and thinking about next steps. | |

| Intervention Manual | A manual is available that includes an overview of the underlying theory, philosophy and principles, and for each component, expected outcomes, empirical and theoretical evidence, required and optional tools, illustrative scripts and potential actions. | |

Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray et al. (2011)

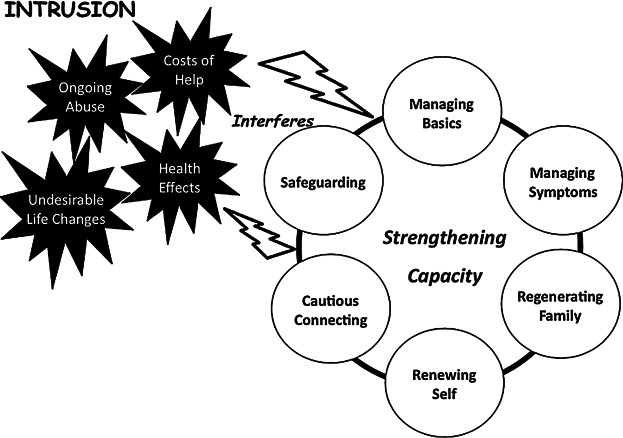

In developing the iHEAL, using constant comparison with quantitative data gathered in our longitudinal study of women's health after leaving (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2009; Varcoe et al., 2011; Wuest et al., 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010), we modified the SCLI theory to include six approaches used by women to strengthen capacity to manage intrusion: managing basics, managing symptoms, safeguarding, cautious connecting, renewing self and regenerating family (see Figure 1; Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, et al., 2011). The six approaches became the core components of the iHEAL. The goal of the iHEAL is to improve women's quality of life (QOL) and health, by strengthening their capacity to limit intrusion by using the six components. A full description of the intervention can be found in Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, et al., 2011.

Figure 1.

A Depiction of the Grounded Theory “Strengthening Capacity to Limit Intrusion.” From: A Theory-Based Primary Health Care Intervention for Women Who Have Left Abusive Partners by M. Ford-Gilboe, M. Merritt-Gray, C. Varcoe, & J. Wuest (2011), Advances in Nursing Science, 34, p. 203, Copyright 2011 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Promotional and commercial use of the material in print, digital or mobile device format is prohibited without the permission from the publisher Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

The protocol is used during 12 to 14 individual sessions with an interventionist over a six-month period (Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, et al., 2011). The six components of the iHEAL are addressed in three phases. In getting in sync, interventionists and women begin to build mutual trust by discussing the woman's priorities, the survival context, and the nature of the iHEAL and the SCLI theory, as well as planning the order of their work on components. In working together, for each component, women are supported to frame their personal experiences of intrusion in light of what is known about other survivors’ intrusion experiences, using paper-based tools or exercises developed for this purpose. Focused discussion as they complete the tools helps women examine the effects of intrusion and the strategies they have tried. This helps them to name what they would like to change. For each component, the next step is sharing options for action, based on her past experiences or experiences of other women and available resources. Women are supported in their consideration of risks and benefits as a basis for deciding next steps, which may include taking calculated risks. Critical to this process is identifying women's strengths and capacities to do what they want to do, while naming what they need in terms of skills, knowledge and resources to reach the identified goal. Interventionists support women in strengthening capacity using approaches such as pacing, informing, coaching, connecting to services and advocating (Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, et al., 2011). Finally in moving on, the emphasis is on reinforcing strengths, reviewing progress, highlighting women's resources, and helping them think about next steps. Women choose the pacing, sequence, and time spent on each component in the iHEAL (Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, et al., 2011).

From Intervention to Partnership in a Feasibility Study

A timely call for proposals from national and provincial health research funding agencies for the Partnerships for Health System Improvement (PHSI) was the catalyst for a proposal to assess the feasibility of RNs providing the iHEAL in partnership with the workers from the DV outreach program. Policy partners supported the language of “feasibility” versus “pilot” because the word “pilot” could set up public expectations of future implementation. A key goal of the PHSI program is more timely knowledge transfer by engaging decision-makers in the research process.

University researchers; the NB government's Women's Equality Branch and Department of Health; and Liberty Lane Inc., a non-profit agency providing DV services, worked together to design, garner funding and conduct this study. Wuest and Merritt-Gray took responsibility for project implementation, data analysis and communication of study progress and findings with stakeholders. Interventionist, partner, and researcher expertise was used to address implementation challenges of the NB iHEAL, ensure safety and intervention fidelity, and facilitate advocacy.

Methods

Study Design

Our goal was to determine whether the NB iHEAL was appropriate for future efficacy testing by examining the intervention's feasibility in terms of its acceptability, demand, implementation, practicality, adaptation, integration, and efficacy potential. Using a mixed-method design, we conducted a one-group, pre-post-intervention study, measuring quality of life (QOL), health, capacity, and intrusion at baseline, upon completion of the NB iHEAL (6 months), and 6 months later (12 months). We gathered quantitative and/or qualitative data from participants (survivors of IPV), interventionists (RNs and DV outreach workers), partners, and researchers to explore elements of feasibility. Our hypothesis regarding potential efficacy was: QOL, health and capacity will improve and intrusion will decrease from pre- to post-intervention (6 months), and changes will be sustained at follow-up (12 months).

Setting

Women's Equality Branch enabled partnering with DV outreach programs in two urban and two rural communities. At each site, the interventionist team consisted of a DV outreach worker partnered with an RN hired for the project. One outreach worker went on maternity leave during the project and was replaced. Outreach workers committed to three sessions per participant as in-kind services. RNs were expected to meet about 11 times with each participant. For each participant, decisions regarding who would offer each component of the iHEAL were based on interventionist expertise and availability, and the woman's priorities.

The eight interventionists had 60 hours of group training to optimize fidelity to the theory-based iHEAL and to refine the procedures and materials to increase suitability for partnership implementation in the NB context. This facilitated cross-sector relationship development and consistent uptake of the theory-driven iHEAL during engagement with survivors. The interventionists met at least monthly with the researcher/practice supervisor to ensure intervention consistency and problem-solve, drawing on each other's expertise. Forums were held for community stakeholders and survivors in each study community about 18 months after iHEAL completion to discuss outcomes and local implications.

Sample

Ethical approval was obtained from the university research ethics board. A community convenience sample of English-speaking women 19 years of age or older who had been living separately from their abusive partners for 3 months to 3 years was recruited over 12 months from the four sites, using advertisements, service agencies, and word of mouth. As a primary health care intervention, the NB iHEAL was intended for all women who had separated from abusive partners, and women were not excluded on the basis of their substance use or mental health issues, common exclusionary criteria for DV programs.

Fifty-two women were recruited. Ten women (19%) did not complete the study: two declined after baseline data collection, six withdrew during the intervention, and two completed the iHEAL but could not be located for the 12-month data collection. Withdrawal did not differ by site. (See Table 2 for a description of the 42 women who completed the study.) Using purposeful sampling to maximize diversity based on characteristics such as age, location, abuse history and degree of intrusion, we interviewed 43% (n = 18) of the 42 DV survivors and all nine interventionists (4 RNs and 5 DV outreach workers).

Table 2.

Characteristics at Baseline of Women who Completed iHEAL Intervention and Follow-Up (n = 42)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 41.7 (10) | 20–61 |

| Duration of IPV in years | 9.7 (8.3) | 0.5–39 |

| Months separated from partner | 14.5 (10.4) | 3–36 |

| Annual personal income in Canadian dollars | $22,260 (17,992) | $2,000–$78,000 (Median $16,500) |

| % |

n |

|

| Employed | 40.5 | 17 |

| Receiving social assistance in past 6 months | 45.2 | 19 |

| Education | ||

| Elementary | 2.4 | 1 |

| High school | 42.9 | 18 |

| Specialty certificate or college diploma | 33.3 | 14 |

| University degree | 19.1 | 8 |

| Unreported | 2.4 | 1 |

| Dependent children <18 years old at home | 61.9 | 26 |

| Child abuse history | 68.3 | 28 |

| Adult sexual assault other than by ex-partner | 59.5 | 25 |

Note. SD = standard deviation.

Measures

Quantitative data describing the intervention implementation profile (e.g., meeting duration and number) and changes in women's health information (e.g., blood pressure, medications, referrals) were recorded in structured participant files by interventionists. Records of interventionist hours of work, kilometres travelled, and costs were maintained. For each participant, demographic information and history of childhood maltreatment and adult sexual assault were collected using self-report items.

Outcomes consistent with the intervention theory were identified (Craig et al., 2008) and measured using self-report scales that had reliability and validity in previous research with women abuse survivors (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2009). We measured QOL with the 9-item Quality of Life Scale (Sullivan & Bybee, 1999), and health with the physical and mental health summary scores of the 12-item Short Form Health Survey, Version 2 (SF-12v2; Ware, Kosinki, Turner-Bowker & Gandek, 2002).

Capacity was operationalized as mastery and social support. Mastery, a sense of control over forces that affect women's lives, was rated on the 7-item Mastery Scale (Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, & Mullan, 1981). Social support, perceived availability of emotional and tangible aid, was measured with the 13-item subscale from the Interpersonal Relationship Inventory (IPRI) (Tilden, Hirsh, & Nelson, 1994).

Intrusion was operationalized as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptom severity, depressive symptom severity, social conflict, and financial strain. We measured PTSD symptom severity using the total score on the 17-item Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS; Davidson, 1996; Davidson et al., 1997). Scores greater than 40 are consistent with a clinical diagnosis of PTSD. Depressive symptom severity was measured with The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) 20-item scale (Radloff, 1977). Total scores greater than 16 are consistent with symptoms of clinical depression. Social conflict, perceived discord within relationships, was measured using the 13-item subscale from the IPRI (Tilden et al., 1994). The total score of the Financial Strain Index was used to measure level of financial strain (Ali & Avison, 1997). Internal consistency was greater than .80 on all measures at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months, except for the Mastery Scale, for which Cronbach alpha was .78, .69, and .77 respectively.

Data Collection

After obtaining informed consent, data collectors used computer-assisted data entry to collect data at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months, in women's homes or safe locations of their choice. We used safety protocols including suicide risk assessment and routine debriefing that were effective in our other studies of woman abuse. Interventionists recorded the nature of intrusion, the plan for action, and follow-up/outcomes in participant files. Researchers recorded notes about interventionist training/supervision sessions, and researcher-partner meetings.

Qualitative interviews exploring elements of feasibility (Bowen et al., 2009) were conducted with 18 participants and the 9 interventionists after they gave informed consent. All interventionists were interviewed twice, once in the first months and again after the intervention ended. Interviews with survivors took place between their 6- and 12-month surveys.

Each interview began with a broad question about their iHEAL experience to encourage the interviewees tell us about what was most important to them. Then they were asked to talk about the best part of being a participant or interventionist and what had been most challenging or difficult. Depending on the unfolding discussion, the interviewer followed up with probes or questions to glean further information relevant to the elements of feasibility, with probes varying according to the timing of the interview and who was being interviewed. For example, survivors were asked how the iHEAL compared with how they thought it might be; how it was similar or different to other services used; what, if anything, had changed as a result of taking part; or what they might tell other women about the iHEAL. Interventionists were asked how their work with women using the iHEAL compared to previous work with survivors, how the interventionist partnership affected their practice and outcomes for women, what it was like to practice from the theoretical stance of the iHEAL, how preparation and support during the intervention worked for them, and what changes they would suggest.

Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed with SPSS©-Version 22.0. Data met the assumptions for planned statistical tests, including normality and absence of multicollinearity. We used descriptive statistics to identify sample characteristics and the intervention implementation profile (e.g. hours, duration). Repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) was used to examine: a) multivariate change in all outcomes from baseline to 6 months to 12 months, and b) univariate change in each outcome from baseline to 6 months and 12 months. When the assumption of sphericity was violated for an outcome, the Greenhouse-Geisser Epsilon F statistic was interpreted. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Bonferroni test.

Qualitative content analysis is defined as subjective interpretation of text data through a systematic classification process of coding and exploring patterns (Hseih & Shannon, 2005). All interviews, and notes were analyzed using qualitative directed content analysis, which involves using coding categories (Hseih & Shannon) derived and defined from the elements of feasibility specified by Bowen et al. (2009). We coded qualitative data using categories such as acceptability, demand, and practicality. The breadth of some categories led to the identification of subcategories derived from the category definitions or emergent from the data (Hseih & Shannon). For example, acceptability was defined as the extent to which those delivering or receiving the intervention find it appropriate and satisfying (Bowen et al.), and subcategories of acceptability (framework, approach, and structure and process) that explained what made the iHEAL acceptable were identified. Findings were organized by categories and subcategories with descriptive exemplars.

These quantitative and qualitative analyses facilitated exploration of whether and how the intervention worked and the process of change (Chesla, 2008). Each participant file was reviewed in the context of the woman's demographic profile, change in her outcomes, and her qualitative interview, if conducted. This analysis shed light on ways women's characteristics influenced intervention outcomes and process, which was critical information for future modification (Brown, 2002). The cost of the intervention was estimated using data from the clinical files, travel claims, and time sheets. To calculate per-woman costs, we prorated the costs for non-completers (n = 8) as a proportion of the cost of completers (n = 44) in the original sample (N = 52). Training costs were not included.

Feasibility Findings

Acceptability

Acceptability is the extent to which those delivering and receiving the intervention find it appropriate and satisfying (Bowen et al.). The NB iHEAL was acceptable to the diverse participants and the interventionists, despite the dissimilarity among study communities in infrastructure and services. Acceptability stemmed from the iHEAL's framework, approach, and structure and process.

Framework

The framework challenged women to see and act on new possibilities. One survivor spoke of the intrusion theory, “I was always led to believe I was crazy. The language [of the iHEAL] encouraged me that I wasn't.” The capacity-building framework guided RNs to emphasize existing strengths and foster potential, a focus that felt revolutionary for some survivors. As well, learning that health problems could be linked to physiologic changes from the traumatic stress of abuse was liberating (McEwen, 2008; Schnurr & Green, 2004), “It helped me put 2 + 2 together…really eye-opening!” Women also liked the holistic primary health care focus of the nurse-outreach worker partnership: “They were concerned with every aspect of my life. They had the knowledge of how to do it and the connections to make it happen…and to just go to one spot and cover so much.”

Approach

In contrast to other services, women did not feel “forced to fit” the NB iHEAL. They found it more accessible; they could control the pace and interventionists met with them where and when women needed them. Because interventionists validated their experiences of trauma and abuse, women felt less stigmatized. Although women cancelled or periodically did not show up, the iHEAL framework supported interventionists not to give up on survivors, unlike other services that discharge clients who do not show up. Interventionist authenticity paid off: “They made me feel very safe, heard, understood, and comforted, which made re-living it all a little bit less painful.” Although important, this sense of personal connection was not sufficient: “We [interventionists] knew how to deal with anxiety, depression, and hopelessness, and were able to build on her capacity from where she's at.”

Structure and process

The iHEAL structure and process facilitated change: “The structure kept me [survivor] on track, out of that fog. It wasn't just talking, it was doing practical things.” The tools promoted reflection and discovery: “I didn't realize how much I was affected by the abuse until the exercises and the little charts.” Women worked through deep, difficult emotions, finding the work hard, but not intrusive. They gained new capacities for taking action: “Now I have tools to work with.” The interventionists observed that the iHEAL process did not increase system dependency but “sustained survivors so that they could take it from there,” an assertion consistent with the quantitative outcomes and survivors’ comments.

Implementation

Implementation refers to the degree to which the intervention can be put into practice as proposed within existing contexts (Bowen et al., 2009). Implementation of the NB iHEAL was facilitated by partnerships with policy-makers and outreach workers and their affiliated non-profit organizations, providing direction for overcoming contextual implementation challenges that shifted over time. For example, over the 4-year study period, fiscal constraints increased drastically for government and non-profits, influencing their perceptions of what could be reasonably implemented.

Intervention implementation profile

The intervention implementation profile (See Table 3) for the 42 women who completed the study was consistent with our implementation plan. The diversity of survivor needs was evident in the range in the duration and number of sessions. A few women “took a break” for reasons such as hospitalization or travel, resulting in a slightly longer intervention period. Others preferred to complete the components quickly, finishing in a shorter period. For hard-to-reach women, a meeting schedule helped ensure regular contact and completion.

Table 3.

NB iHEAL Implementation Profile for Participants who Completed the Study (n = 42)

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of NB iHEAL in weeks | 27.0 | 2.4 | 22–32 |

| Number of contact hours | 16.8 | 4.1 | 9.9–26.8 |

| Total meetings with interventionists | 13.6 | 2.1 | 9–17 |

| Number of meetings with a nurse | 10.0 | 2.6 | 4–17 |

| Number of meetings with an outreach worker | 2.8 | 1.8 | 0–7 |

| Number of joint meetings (both interventionists) | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0–5 |

Note. M = mean, SD = standard deviation.

Early in the study, RNs and outreach workers realized that an initial session together with each woman improved communication and planning. An asset of their partnership was flexibility in covering staff maternity leaves, vacations and new hires, which minimized disruption for women. This flexibility partially accounted for the variation in number of sessions with RNs versus outreach workers. As expected, most sessions occurred in women's homes (61%) or in the outreach offices (22%). Because outreach offices were generally too small to share, RNs used their homes, with designated cell phones as office space. Therefore, the transfer of participant files and verbal exchange of information was sometimes a challenge.

Health as priority

During implementation, interventionists were challenged to keep health as a priority while respecting women's main concerns. Many survivors accepted symptoms such as fatigue and anxiety as normal: “Yes, I'm tired but I've been tired for 10 years.” RNs used intake information about symptom frequency and routinely took blood pressures and medication histories to help women recognize health problems as a priority. They intentionally used opportunities when working on other iHEAL components to address health: “Maybe we'd start with managing basics and perhaps they weren't able to work. They had no energy, too much back pain and were living on social assistance…so we would get into health that way.”

Still, it was hard for survivors to prioritize health, in light of pressing crises related to custody and access, housing, and income. Interventionists struggled to get beyond “putting out fires” and became skilled at helping women develop more sustainable strategies for dealing with crises. Specifically, they helped women learn to name and draw on their strengths, take time to attend to symptoms aggravated by crises, focus on their hopes for the future, and become more proactive, strategic help seekers.

RNs grappled with tension between the principle of being woman-centered and the requirement to cover all components: “How much do you follow her lead? Some things would be helpful but she doesn't know it yet.” To balance the structure with the best pacing, interventionists “had to be driven by absolute belief in the intervention and in women's capacity to rebuild their lives and gain more strength.”

Availability and usefulness of health services

Another implementation challenge was variation in availability and usefulness of health services. Family doctors had the potential to be helpful, but after-hours clinics were critical for timely care for all women, especially for those without providers. But having a provider was not enough. For example, survivors reported fatigue or difficulty sleeping, depression, anxiety, and chronic pain as the issues most detrimental to their daily functioning. Providers often discounted these problems, especially when unaware of abuse and trauma. RNs helped women to be heard by providers, by writing letters to validate health problems and coaching women about abuse disclosure and ways to frame symptom patterns, severity and consequences. “I was procrastinating about seeing the doctor; the nurse pushed and pushed and when I went, he had the nurse's letter. It was amazing.”

Interventionists’ use of professional and personal connections to ease women's access to services was also vital. Private services were beyond the financial reach of most survivors. Scarcity of specialty trauma resources and accessibility problems due to lack of transportation and/or long waiting lists left interventionists feeling like the “finger in the dyke,” often for months. Collaboration with mental health and addiction services after women accessed their care was challenging for interventionists.

Demand

Demand refers to how much the intervention process, components or activities are used and fit with organizational culture, and the intention of continued use (Bowen et al., 2009). Fit with the target population was evident in that 64% of survivors who took part were former outreach clients. In part, their recruitment was facilitated by meaningful partnerships at both policy and direct service levels.

With one exception, all components and required tools were used with all participants. The outreach workers said the iHEAL enhanced their usual work. Because iHEAL tools “helped women see things differently and sparked discussion about other things,” interventionists used them with their other clients and shared them with colleagues in other communities.

The addition of the health component and the RN to the outreach setting was a change in organizational culture. Past experience of health providers with limited understanding of violence made outreach workers uncertain about the feasibility of partnering with RNs; RNs were uncertain about the feasibility of practicing in this new arena. This uncertainty quickly dissipated. All nine interventionists valued the partnership and noted their complementary growth in understanding and managing violence and health.

Because RNs were hired only for the study, neither health as a priority nor the partnership was sustained beyond the study, but follow-up forums with survivors and stakeholders created bridges with interested local health providers to explore ways to better address the health of outreach clients. RNs’ increased knowledge and skills were potentially transferable to their practice in other settings.

Integration

Integration focuses on the system change needed to implement an intervention into existing infrastructure (Bowen et al., 2009). The NB iHEAL is a novel primary health care intervention that spans health and DV sectors and was positioned within the existing DV outreach program within the partnership model. The guiding framework legitimized and expanded outreach workers’ experiential knowledge of survivors’ journeys.

Outreach workers reported previously receiving many referrals from the health sector that too often resulted in providing solo support services for months before the women were able to access needed health care specialists. The NB iHEAL outreach-health partnership made health care accessible outside of the usual health system structure and integrated health care with a range of DV services. Outreach workers contrasted “usual care” outcomes with those achieved for women under this integrated approach: “Within six months, women were getting to a stage with the NB iHEAL that would have taken a year and a half with the outreach program alone.”

The study RNs’ practice was independent of the DV infrastructure. Nurse researchers provided the clinical supervision, protocols, and training; these activities evolved in response to interventionist experiences. RNs functioned autonomously, intentionally using a social determinants of health perspective within their professional scope of practice. We gradually realized that integrating a health care provider within a community-based DV outreach program would require significant change in infrastructure to bridge existing sectoral silos and provide the level of supervision and practice guidelines that RNs needed.

Adaptation

Adaptation refers to how well the intervention performs in different populations (Bowen et al., 2009). Shortcomings in the NB iHEAL protocol were identified. Some tools and components, such as regenerating family, were poorly suited to older survivors. Spirituality was not well-integrated, yet many women identified spiritual networks and activities as important sources of connection. Lifetime history of abuse or marginalization was poorly addressed; many women were grappling with histories of child maltreatment and adult sexual assault and/or dependence on a previously abusive family of origin. Insufficient interventionist training on problematic behaviors such as drug use, time spent online, or eating, was another limitation. These issues received too little attention, despite the underlying principle of harm reduction.

A review of the characteristics of the six women who withdrew during the intervention revealed some potential barriers to participation (Chesla, 2008). Five of the six withdrew before the fifth meeting, raising questions about the process and importance of early engagement. One interventionist observed a propensity for early in-depth sharing of abuse history among those who withdrew; consequently, she intentionally slowed that disclosure with subsequent survivors. Four of the five women had intrusion from many sources, including mental health symptoms at baseline, such as severe symptoms of PTSD or clinical depression, problematic drinking, and chronic disabling pain. Two reported suicidal ideation at least weekly in the previous month. Seeing this, interventionists strengthened emotional safeguarding and harm reduction strategies for women with high intrusion, extreme distress, and limited access to specialty trauma services, and paid careful attention to pacing, with the consequence of increased participant retention.

Efficacy Potential

Efficacy potential refers to the intervention's promise for effectiveness with the intended population (Bowen et al., 2009). In repeated measures multivariate analysis, change in all outcomes from baseline to 6 and 12 months was positive (Pillai's trace criterion, F[18, 24] = 3.64, p = .002) with a partial effect size η2=.73 and a power of .99, supporting the underlying theory of the NB iHEAL (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Changes in Quality of Life, Health, Capacity, and Intrusion from Baseline to 6 and 12 Months Post-intervention using Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (n = 42)

| Scales (Possible Scores) | Baseline (B) |

6 Months |

12 Months |

F (df) | p | Paired Comparisonsa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | B-6 | B-12 | |||

| Quality of Life | ||||||||||

| Quality of Life Scale (9–63) | 39.2 (9.9) | 19–57 | 46.0 (10.1) | 22–63 | 43.9 (10.8) | 18–61 | 22.3 (2, 82) | <.001 | *** | *** |

| Health | ||||||||||

| SF-12 Mental Summary Score (0–100) | 35.5 (11.2) | 17–61 | 44.0 (11.5) | 23–69 | 42.6 (11.6) | 18–60 | 15.0 (2, 82) | <.001 | *** | *** |

| SF-12 Physical Summary Score (0–100) | 45.0 (13.3) | 17–65 | 46.3 (11.9) | 16–61 | 46.0 (13.1) | 21–65 | 0.4 (2, 82) | .68 | ||

| Capacity | ||||||||||

| Mastery Scale (5–35) | 22.7 (6.3) | 12–34 | 25.7 (5.4) | 14–35 | 26.4 (5.8) | 13–35 | 10.9 (1.6, 66.5) | <.001 | ** | *** |

| IPRI Social Support Subscale (13–65) | 52.5 (9.5) | 25–65 | 54.9 (8.7) | 33–65 | 54.0 (9.2) | 31–65 | 3.5 (2, 82) | .04 | * | |

| Intrusion | ||||||||||

| Davidson Trauma Scale (0–136) | 54.2 (26.7) | 2–110 | 31.5 (26.0) | 0–102 | 32.8 (25.1) | 0–94 | 27.4 (2, 82) | <.001 | *** | *** |

| CES-D (0–60) | 24.8 (12.3) | 7–54 | 16.5 (10.8) | 0–37 | 17.7 (12.5) | 0–49 | 20.2 (2, 82) | <.001 | *** | *** |

| Financial Strain (0–56) | 38.1 (10.4) | 14–55 | 36.9 (12.2) | 14–55 | 35.0 (13.2) | 14–56 | 1.9 (2, 82) | .16 | ||

| IPRI Social Conflict Subscale (13–65) | 37.6 (10.6) | 15–58 | 36.9 (8.8) | 17–57 | 35.6 (9.2) | 20–56 | 1.0 (1.7, 71.0) | .37 | ||

Note. SD = standard deviation. SF-12 = Short Form Health Survey v12, IPRI = Interpersonal Relationship Inventory. CESD = Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale.

Significance levels based on Bonferroni tests of baseline to 6-month (B-6) and baseline to 12-month (B-12) paired comparisons. No differences from 6-month to 12-month scores were significant.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Consistent with our hypotheses, improvements between baseline and 6 months were significant for a number of outcomes and were sustained at 12 months, based on univariate RM-ANOVA and post hoc testing. QOL, health as indicated by mental health, capacity as indicated by mastery, and intrusion as indicated by PTSD and depressive symptom severity all improved. Of 42 participants, the number with symptoms of clinical depression dropped from 32 at baseline to 20 at 12 months, and the number with symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD dropped from 22 to 14.

Social support as an indicator of capacity improved significantly from baseline to 6 months but not from baseline to 12 months. Health as indicated by physical health and intrusion as indicated by financial strain and social conflict did not improve significantly from baseline to 6 months or 12 months.

These preliminary efficacy findings imply that QOL and mental health can improve for women who have experienced the trauma of IPV. The absence of significant improvement in physical health may suggest that a) modifications to the iHEAL are needed to increase the focus on physical health, b) physical health takes longer to change than mental health, c) improvements in mental health are necessary before women can make lifestyle changes needed to improve their physical health, and/or d) the SF-12 physical health summary score lacks sensitivity to capture change in this population.

The significant reduction in intrusion from symptoms of depression and PTSD is noteworthy, although the absence of a control group does not allow a causal link to be made to the intervention. However, the 12-month decline in depressive symptom severity (measured on the CES-D) was greater in the NB iHEAL sample (M ≤ 24.8[SD = 12.3] at baseline and M = 17.7[SD = 12.5] at 12 months) than in a cohort of 227 Canadian women who had separated from abusive partners and received usual care (M = 24.2[SD = 13.0] at baseline and M ≤ 21.6[SD = 13.5] at 12 months; Scott-Storey, ). This suggests that the reduction in depressive symptoms is unlikely to be accounted for by the passage of time alone. Better mental health and mastery may be important gains that help women tackle challenges such as job retraining, complex parenting, legal battles, and addictions.

Practicality

Practicality is to the degree to which the intervention can be carried out using existing resources (Bowen et al., 2009). The NB iHEAL was implemented with promising outcomes in existing contexts with the addition of RNs at each site. The intervention implementation profile was consistent with the plan. The average cost in Canadian dollars per woman for the NB iHEAL was $3,020 (see Table 5), almost $2,000 less than the yearly estimated costs of health services for women after leaving attributable violence (Varcoe et al., 2011). Still, given the per-woman cost and number of contact hours, policymakers were sceptical of the intervention's practicality in the existing fiscal climate. Our limited data on use of other health services made it impossible to account for total health services costs or to calculate pre- versus post-intervention change in health care costs. There is a pressing need to collect these data in future studies. The team also questioned whether changes in health care use would be visible 6 months following completion of the iHEAL. The rural nature of NB, and women's preference for meeting at home, resulted in interventionist travel costs that accounted for 14% of intervention cost ($436 per woman). One suggested strategy to lower the costs of the iHEAL was paying for women's travel costs to the interventionist, thereby saving on costs of interventionist travel time.

Table 5.

Costs of NB iHEAL per Participant (N = 52)a

| Cost Source | Costs per Woman in Canadian Dollars |

|---|---|

| Nurses’ salary (intervention preparation, delivery, and follow-up, and travel time), travel expenses, and cell phone costs | $2,345 |

| Outreach costs beyond in-kind contribution | $76 |

| Supplies and clinical supervision | $167 |

| Estimated value of in-kind outreach contribution | $432 |

| Total cost per woman | $3,020 |

Of 52 women who enrolled, 42 completed all intervention and follow-up; costs for those who did not complete the program were pro-rated.

Discussion

Consistent with our purpose, our discussion focuses on the process, outcomes and challenges of conducting feasibility studies in partnership. Feasibility study findings inform decisions about the merits of conducting further testing of an intervention (Bowen et al., 2009). The initial formal analysis that researchers shared with partners was focused on change in outcomes, generating a profile of the NB iHEAL as delivered, and estimating implementation costs.

Statistically significant gains in mental health were compelling because mental health is a provincial priority (Province of New Brunswick, 2011), and higher rates of depression and anxiety in women versus men have been linked to a greater burden of violence (Hegarty, 2011) and greater risk of returning to an abusive relationship (Alhalal, Ford-Gilboe, Kerr & Davies, 2012). Findings related to intrusion, specifically the reduction in the numbers of women with symptoms consistent with clinical depression or diagnoses of PTSD, suggested the intervention may yield clinically significant outcomes, a key concern of decision-makers (Brown, 2002). Further, the implementation process profile was consistent with the research plan and intervention costs were 40% lower than the estimated annual costs of health care use attributable to violence for this population.

Researchers interpreted these initial findings to mean that delivering the iHEAL in an outreach worker-nurse partnership was feasible, rather than as an indication that more efficacy testing was warranted. Policy partners had a different perspective. They reinforced the need for similar evidence in a controlled study before the intervention itself could be judged feasible.

Implications for Modification

In the current context of economic restraint and limited data on pre- and post-intervention service use, partners considered both intervention hours and costs to be high, calling into question the practicality of the NB iHEAL. A particular concern was the potential workload implications for existing outreach workers. Bowen et al. (2009) stressed the importance of discarding or modifying interventions when study outcomes suggest that the intervention does not address relevant feasibility questions.

Our findings with respect to most elements of feasibility suggest that the NB iHEAL shows promise and warrants further efficacy testing. However, modifications to both the NB iHEAL and the research design would be essential. Lessons learned regarding adaptations for some survivors provide direction for modifying the iHEAL content and process. Consideration of ways the iHEAL might better support improvement in women's physical health also is needed. Costs will need to be reduced without compromising iHEAL acceptability or efficacy. To enable more complete cost comparisons, more complete documentation of pre-post intervention health service use is required. A central argument for developing the iHEAL was the cost of health care attributable to violence; hence, realistic cost analysis needs to include not only the delivery costs but also the changes in system costs over time. Additional design changes could include using a different measure of physical health and adding a 12-month post-intervention follow-up (18 months from baseline) to capture delayed gains or losses.

Knowledge Translation

We were committed to integrated and end-of-study knowledge translation (KT), in which learning generated by the study can be applied both during and after the project. During the course of the study, researchers and partners became aware that their individual interpretations of KT differed and were evolving. Integrated KT was facilitated by engagement of all throughout the study process. For example, discussion of intrusive system challenges encountered by survivors, such as problems with home assessments for child custody, allowed partners to provide timely feedback to appropriate sectors. Outreach workers’ uptake of iHEAL tools exemplifies useful integrated KT that was valued by partners and consistent with funding agency priorities. Yet, researchers, whose KT priority was to inform subsequent efficacy testing, questioned whether “usual care” would differ significantly from care in the intervention group if the iHEAL tools were widely used in usual care. The impact of integrated KT on intervention research programs is rarely considered. For example, can integrated KT lead to premature implementation?

The KT priority of partners was providing key messages to assist those involved with existing policy, programs, and practices, to better address survivor needs. Partner direction guided the broader feasibility analysis of interviews, meeting notes, and charts. Still, some researchers struggled with the extent to which lessons from the NB iHEAL would be applicable to other programs, arguing that findings were an outcome of the NB iHEAL as a whole and could not be assured with implementation only of selected pieces. Ongoing data analysis, continuing dialogue among researchers, interventionists, and partners, and community forums helped to reconcile these tensions and gradually led to identification of broader lessons.

Lessons for Policy, Programs, and Practice

Two important policy lessons relate to integrated care and system navigation. Although integrated care is key to health care reform, ways to bridge silos among health and other systems for better outcomes are poorly understood (Kodner, 2009). Our findings suggest that an integrated social determinants approach for joint health and DV services may improve survivors’ health and build skills for sustaining those gains.

Positioning the NB iHEAL within the current DV outreach structure reinforced capacity-building and lessened the illness focus. Many survivors did not prioritize health issues because intrusive symptoms had persisted for so long that they became unremarkable, and other issues (e.g., custody, housing, safety) demanded their immediate attention. Yet health problems compounded these pressing issues. The social determinants focus of the iHEAL components permitted interventionists to begin with a woman's current priority and intentionally help her to see its link with health, thus assisting her to strengthen her capacity to manage both. The RN/outreach partnership bridged the usual silos; the pair had the knowledge, skills, and connections to provide integrated timely support for a wide range of issues in a woman-centered way.

These findings regarding outcomes of integrated services reinforce Allen et al.'s (2013) suggestion that how services are delivered to women with abuse histories may be as important as what is provided. Our findings also broaden understanding of how system navigation may be most effective for survivors. System navigators seek to overcome survivors’ logistical and individual (literacy, culture, language) barriers to connecting with needed resources and services in a timely way (Dohan & Schrag, 2005). We found that facilitating ways around such barriers was essential but not sufficient. Effective system navigation required repeated and persistent validating, coaching, and skill-building to enable each woman to strengthen her ability to position herself to use available resources to her advantage.

Findings from this feasibility analysis also can inform ways to increase the usefulness of other health programs for survivors. In particular, structured activities that foster personal reflection to reframe the IPV experience and its effects on their health can assist women to counter past abusive messaging and see pathways forward. An action focus that assists women to build skill sets to do things to achieve their goals and dreams is also useful. Findings related to acceptability of the NB iHEAL highlight transferable approaches for providers working with survivors elsewhere: unconditional acceptance of the experience of violence, focus on women's strengths, trust in their capacity, flexible responsiveness to current concerns while not losing sight of the whole picture, predictable trustworthy support, not giving up, willingness to step outside usual boundaries, and establishing genuine relationships.

Conclusion

These findings draw attention to the benefits and challenges of partnerships in feasibility studies when the goal is to determine whether further intervention testing is justified. Partnerships were critical for implementing the iHEAL in a real-world setting and offered system perspectives and expertise that greatly enhanced the research. We learned the importance of attending to both academic and partner needs for knowledge in explicating the implications of study findings. However, even when researchers and partners work closely together from proposal to knowledge transfer and believe they are on the same page, missteps can be taken. Respect and longstanding relationships permitted frank dialogue and mutual support in reaching outcomes useful for all.

Careful collection and analysis of data to address most elements of feasibility and not just efficacy potential was critical for evaluating whether further testing was indicated. The rich findings from both qualitative and quantitative data helped us to identify characteristics of content and process vital for the NB iHEAL's acceptability as well as the modifications needed to increase fit and responsiveness. Insights also were gleaned regarding system changes that would be required for integrated provision of the NB iHEAL across sectors. For future research design, findings provide a basis for effect-size estimation, consideration of alternate measures of physical health, and direction for additional data collection to address cost effectiveness. These outcomes are evidence of the value of considering the full scope of feasibility when designing studies to determine whether an intervention should proceed to more controlled efficacy testing.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the New Brunswick women, communities, and domestic violence outreach programs that supported this research. Partnerships with the Government of New Brunswick, Women's Equality Branch and Department of Health, and Liberty Lane Inc. made this research possible. This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the New Brunswick Health Research Foundation under the Partnerships for Health System Improvement Program, grant 101529. The project was affiliated with the Muriel McQueen Fergusson Centre for Family Violence Research.

Notes

Becker (2008) uses the term pilot study rather than feasibility but indicates that feasibility is the primary goal of pilot studies conducted in natural settings. Thus, her critique applies here.

References

- Alhalal E, Ford-Gilboe M, Kerr M. Davies L. Predictors of maintaining separation from an abusive partner. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2012;33:838–850. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.714054. &. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.714054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali J, Avison WR. Employment transitions and psychological distress: the contrasting experiences of single and married mothers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:345–362. &. doi: 10.2307/2955430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen N, Larsen S, Trotter J, Sullivan C. Exploring the core service delivery processes of an evidence-based community advocacy program for women with abusive partners. Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;41:1–18. &. doi: 10.1002/jcop21502. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D, Saunders D, Yoshihama M, Bybee D, Sullivan C. Long-term trends in depression among women separated from abusive partners. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:807–838. &. doi: 10.1177/1077801203009007004. [Google Scholar]

- Becker P. Publishing pilot intervention studies. Research in Nursing & Health. 2008;31:1–3. doi: 10.1002/nur.20268. . doi: 10.1002/nur.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood B. Methodological issues in evaluating complex healthcare interventions. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;54:612–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03869.x. . doi: 10.1111/j.1365–2648.2006.03869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen D, Kreuter M, Spring B, Cofta-Woerpel L, Linnan L, Weiner D, Fernandez M. How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2009;36:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002. &. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SJ. Nursing intervention studies: A descriptive analysis of issues important to clinicians. Research in Nursing & Health. 2002;25:317–327. doi: 10.1002/nur.10039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne G, Byrne C, Roberts J, Gafni A, Whittaker S. When the bough breaks: Provider-initiated comprehensive care is more effective and less expensive for sole-support parents on Social Assistance. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53:1697–1710. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00455-x. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter K, Grey M, Bowers B, McCarthy A, Gross D, Funk M, Beck C. Intervention research in highly unstable environments. Research in Nursing & Health. 2009;32:110–121. doi: 10.1002/nur.20309. &. doi: 10.1002/nur.20309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Rose L, Kub J, Nedd D. Voices of strength and resistance: A contextual and longitudinal analysis of women's responses to battering. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1998;13:743–762. &. doi: 10.1177/088626098013006005. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell N, Murray E, Darbyshire J, Emery J, Farmer A, Griffiths F, Kinmouth A. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. British Medical Journal. 2007;334:455–459. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE. &. doi: 10.1136/bmj.oi39108.379965.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesla C. Translational research: Essential contributions from interpretive nursing science. Research in Nursing & Health. 2008;31:381–390. doi: 10.1002/nur.20267. . doi: 10.1002/nur.202672005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Mitchie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. British Medical Journal. 2008;337:979–983. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. & http://www.jstor.org/stable/20511140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J. Pavidson Trauma Scale. Toronto, ON: MultiHealth Systems; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J, Book S, Colket J, Tupler L, Roth S, David D, Feldman M. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:153–160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004229. &. doi: 10.1017/S003329179600422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker M, Frattaroli S, McCaw B, Coker A, Miller E, Sharps P, Gielen A. Transforming the healthcare response to intimate partner violence and taking best practices to scale. Journal of Women's Health. 2012;21:1222–1229. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4058. &. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients. Cancer. 2005;104:848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. &. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg M, Jansen H, Heise L, Watts C, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: An observational study. The Lancet. 2008;371:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. & on behalf of the WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence Against Women Study Team. ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M, Wuest J, Varcoe C, Davies L, Merritt-Gray M, Hammerton J, Campbell J. Modelling the effects of intimate partner violence and access to resources on women's health in the early years after leaving an abusive partner. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.003. &. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M, Merritt-Gray M, Varcoe C, Wuest J. A theory-based primary health care intervention for women who have left abusive partners. Advances in Nursing Science. 2011;34:198–214. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182228cdc. &. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e318228cdc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M, Varcoe C, Wuest J, Merritt-Gray M. Intimate partner violence and nursing practice. In: Cambell J, editor; Humphreys J, editor. Family violence and nursing practice. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 115–154. &, Eds., &. In: ( [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M, Wuest J, Merritt-Gray M. Strengthening capacity to limit intrusion: Theorizing family health promotion in the aftermath of woman abuse. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:477–501. doi: 10.1177/1049732305274590. &. doi: 10.1177/1049732305274590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M, Wuest J, Varcoe C, Merritt-Gray M. Developing an evidence-based health advocacy intervention to support women who have left abusive partners. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2006;38(1):147–168. &. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Glasgow R. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: Issues in external validation and translation methodology. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2006;29:126–153. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284445. &. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K. The relationship between abuse and depression. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2011;46:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.08.001. . doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hseih H, Shannon S. Three approaches to content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. &. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodner D. All together now: A conceptual exploration of integrated care. Health Care Quarterly. 2009;13:6–15. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.21091. . doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach C. Some thoughts on the hazards of sloppy science when designing and testing multicomponent interventions, including the kitchen sink phenomena. Research in Nursing & Health. 2009;32:1–3. doi: 10.1002/nur.20307. . doi: 10.1002/nur.20307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;583:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.071. . doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minister's Working Group on Violence Against Women A better world for women. 2001. New Brunswick Province of New Brunswick.

- Minister's Working Group on Violence Against Women A better world for women: Moving forward 2005–2010. 2005. New Brunswick Province of New Brunswick.

- Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:37–356. &. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plichta S. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: Policy and practice implications. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:1296–1323. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269685. . doi: 10.1177/0886260504269685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plichta S. Interactions between victims of intimate partner violence against women and the health care system: Policy and practice implications. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8:226–239. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301220. . doi: 10.1177/1524838007301220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Province of New Brunswick 2011. The Action Plan for Mental Health in New Brunswick 2011–18 http://www.gnb.ca/0055/pdf/2011/7379%20english.pdf.

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. . doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, J., Rivas, C., & Feder, G., (2005). Interventions to reduce violence and promote the physical and social well-being of women who experience partner violence: A systematic review of controlled evaluations. Barts and the London: Queen Mary's School of Medicine and Dentistry. Retrieved from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4127426.pdf.

- Schnurr P, Green B. Trauma and health: Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. &. [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Storey, K. (2013). Lifetime abuse as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease among women. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada.

- Sidani S, Epstein D, Moritz P. An alternative paradigm for clinical nursing research: An exemplar. Research in Nursing & Health. 2003;26:244–255. doi: 10.1002/nur.10086. &. doi: 10.1002/nur.10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan C, Bybee D. Reducing violence using community-based advocacy for women with abusive partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:43–53. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.43. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilden VP, Hirsch AM, Nelson CA. The interpersonal relationship inventory: Continued psychometric evaluation. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 1994;2:63–78. &. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varcoe C, Hankivsky O, Ford-Gilboe M, Wuest J, Wilk P, Hammerton J, Campbell J. Attributing selected costs to intimate partner violence in a sample of women who have left abusive partners: A social determinants of health approach. Canadian Public Policy. 2011;37:359–380. doi: 10.3138/cpp.37.3.359. &. doi: 10.1353/cpp.2011.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinki M, Turner-Bowker DM. Gandek B. How to score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated and Health Assessment Lab; 2002. &. [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J, Ford-Gilboe M, Merritt-Gray M, Berman H. Intrusion: The central problem for family health promotion among children and single mothers after leaving an abusive partner. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:597–622. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013005002. &. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J, Ford-Gilboe M, Merritt-Gray M. Varcoe C. Building on “grab”, attending to “fit”, and being prepared to “modify”: How grounded theory “works” to guide a health intervention for abused women. In: Beck C, editor; Routledge handbook of qualitative research in nursing. London: Routledge; 2013. pp. 32–46. . In (Ed.),, & ( [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J, Ford-Gilboe M, Merritt-Gray M, Varcoe C, Lent B, Wilks P, Campbell JC. Abuse-related injury and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder as mechanisms of chronic pain in survivors of intimate partner violence. Pain Medicine. 2009;10:739–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00624.x. &. doi: 10.1111/j.1526–4637.2009.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J, Ford-Gilboe M, Merritt-Gray M, Wilks P, Campbell JC, Lent B, Smye V. Pathways of chronic pain in survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Women's Health. 2010;19:1665–1674. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1856. &. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J, Merritt-Gray M, Ford-Gilboe M, Lent B, Varcoe C, Campbell JC. Chronic pain in women survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Pain. 2008;9:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.009. &. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J, Merritt-Gray M, Lent B, Varcoe C, Connors A, Ford-Gilboe M. Patterns of medication use among women survivors of intimate partner violence. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2007;98:460–464. doi: 10.1007/BF03405439. &. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]