Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) exhibits characteristic variability of onset and rate of disease progression, with inherent clinical heterogeneity making disease quantitation difficult. Recent advances in understanding pathogenic mechanisms linked to the development of ALS impose an increasing need to develop strategies to predict and more objectively measure disease progression. This review explores phenotypic and genetic determinants of disease progression in ALS, and examines established and evolving biomarkers that may contribute to robust measurement in longitudinal clinical studies. With targeted neuroprotective strategies on the horizon, developing efficiencies in clinical trial design may facilitate timely entry of novel treatments into the clinic.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is characterized by heterogeneity in the region of onset, rate of progression, patterns of disease spread, and relative burden of upper motor neuron (UMN), lower motor neuron (LMN), and cognitive pathology. This phenotypic variability in ALS complicates measurement of disease progression. However, recent conceptual and technological advances have suggested novel approaches. With the dawning era of targeted therapeutics in ALS, accurate measurement of disease burden remains a critical priority to facilitate efficient clinical trial design and to enable further insights into disease pathogenesis. As such, the present review will discuss the current tools and future biomarker and clinical trial approaches that may be useful in measuring disease progression in ALS.

Clinical and Genetic Determinants of Progression

Recognized ALS Clinical Phenotypes

The clinical hallmark of ALS is the presence of concomitant UMN and LMN disease involving brainstem- and spinal-innervated regions. Disease onset in ALS is typically anatomically localized, with subsequent spread into other, usually contiguous body regions. Patterns of disease involvement and spread have been described,1–4 which may facilitate anticipation of the sequence of regional involvement and prognosis. Predicting patterns of disease spread may be useful when measuring treatment response, and specific staging systems have been devised to account for regional spread in ALS.5,6 In an individual with ALS, disease advances at a relatively constant rate,7 although progression may be influenced by clinical, demographic, and genetic features (Table1).

Table 1.

Factors Influencing the Rate of Progression in ALS

| Factor | Associated with Longer Survival | Associated with Shorter Survival |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | Flail limb variant,9 LMN-predominant disease,8 UMN-predominant disease,82 prolonged interval to diagnosis83 | Bulbar onset ALS,2,84–86 respiratory onset ALS,87 cognitive impairment,88,89 impaired nutritional status,90 neck flexor weakness91 |

| Demographic features | Younger age at diagnosis84,92 | Older age at diagnosis,84,92 lower economic status,93 smoking92,94 |

| Genetic influences | E21G, G37R, D90A G93C, and I113T mutations in SOD1,95 reduced KIFAP3 gene expression,96 reduced EPHA4 gene expression97 | A4V mutation in SOD1,98 FUS mutations with basophilic inclusions99 |

| Treatment | Riluzole,85,93 noninvasive ventilation,100 enteral feeding,101 moderate exercise,102 multidisciplinary clinic care103 | Topiramate104 |

ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; EPHA4 = ephrin type-A receptor 4; FUS = fused in sarcoma; KIFAP3 = kinesin-associated protein 3; LMN = lower motor neuron; SOD1 = superoxide dismutase 1; UMN = upper motor neuron.

A number of distinct clinical phenotypes exist within the ALS disease spectrum, and may be associated with rates of disease progression that differ from those of more typical ALS (see Table1). For example, flail-limb variant ALS presents with progressive LMN weakness of the upper limbs and may remain relatively confined for a prolonged period, resulting in a man-in-the-barrel appearance. Flail-limb variant, along with other LMN-predominant subtypes such as progressive muscular atrophy, may be characterized by slower disease progression.8,9

Patients may also present with UMN-predominant disease. On the extreme of this spectrum is primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), where UMN signs remain isolated, although eventually many patients evolve LMN features over time.10 On average, UMN-predominant and LMN-predominant phenotypes have a better prognosis than classic ALS presentations, although within these groups there may still be marked variability in the rate of disease progression (see Table1).

Some clinicians consider the different phenotypes as fitting within a clinical and pathological continuum (lumpers), whereas others suggest that variation in the clinical presentation may reflect heterogeneity of underlying pathophysiological mechanisms (splitters).11 This issue of accurate disease categorization remains a subject of contention, in need of more complete exploration.

Influence of Genetic and Epidemiological Factors

The contribution of genetic factors to the clinical phenotype and rate of progression in ALS is incompletely understood. Except in a few cases, there is no obvious relationship between underlying genetic cause and phenotype (for a full record, see the ALS Online Genetic Database at http://alsod.iop.kcl.ac.uk; see Table1).12

Several ALS genes exhibit a phenomenon called pleiotropy, where the same gene variation can result in different phenotypes.13 For example, the C9orf72 mutation is a pathological expansion of a repeated DNA sequence. In some individuals this results in ALS, but in others it causes frontotemporal dementia, ALS and frontotemporal dementia, or other less common phenotypes such as psychosis.14 Penetrance has not been definitively established, and not everyone carrying the pathological expansion will develop disease during their lifetime. These observations suggest that environmental factors interact with the mutation to affect outcome. The resulting phenotype does show some correlation with survival, because individuals with cognitive impairment have a faster progression than those without.15

Historically, detection of genetic mutations contributing to ALS pathogenesis has been difficult, as ALS is relatively rare and cohorts of patients with a positive family history are small. Technological advances in genetic analysis, in particular next generation high-throughput sequencing (NGS), may further illuminate the role of genetic influences on ALS disease risk and progression.16 In NGS, multiple sequences are produced in parallel, which improves the efficiency of the process and hence decreases time and cost. Presently, whole exome sequencing with NGS may be a cost-effective way of screening for genetic mutations in coding regions, both in patients with familial ALS without an identified mutation, and to identify clustering of genetic variations in sporadic ALS that may help clarify genetic contributions to disease progression. With increasing cost efficiencies, whole genome sequencing may provide a superior means of genetic screening.17 Collaborative research efforts performing NGS of stored samples from existing cohorts of patients with clinical and progression data (for example via the PRO-ACT database18) may provide a mechanism to predict disease progression prospectively. Reanalysis of completed treatment trials with more detailed genetic information may identify genetic influences on treatment efficacy.

The relationship between genotype, phenotype, environment, and prognosis has implications for clinical trials. Stratification into groups with homogeneous survival would improve statistical power, and might reveal treatments effective in one group that are not so in another. Until recently, stratification was only possible by phenotype, because no environmental factors were known and identified genetic causes were rare. The identification of pathological GGGGCC expansions in C9orf72 in approximately 7% of individuals with sporadic ALS17,19 may provide the opportunity to analyze this group separately, although variability in the phenotype and rate of progression remains an issue in patients with C9orf72 mutation just as in sporadic ALS. As underlying genetic contributions to ALS are identified, such stratification will become easier.

Quantifying Clinical Progression

Measuring Survival

Major treatment trials undertaken in ALS have focused on survival and clinical endpoints for efficacy analysis. As ALS remains a clinical diagnosis, clinical measurement strategies are intuitive as research endpoints. Regulatory approval of new therapies by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products requires evidence of improvement of clinical endpoints such as survival, function, and strength measures. As such, reliable, sensitive, and broadly applicable clinical instruments for the monitoring of disease progression in ALS will remain important in clinical trial design (Table2).

Table 2.

Candidate Biomarkers in ALS

| Measurement | Advantages | Limitations | Recommended Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle strength | |||

| MMTMVICHHD | No equipment barrier; rapid to perform; can measure a broad range of muscle groups Linear; more sensitive to change than MMT for single muscle Minimal equipment requirements; rapid to perform; comparable accuracy to MVIC in weak muscles | Nonlinear; insensitive to change in mild weakness categories Extensive equipment and training barriers to widespread application Clear training effects; underestimates weakness above a force of 20kg | MMT remains useful for clinical monitoring, but more rigorous quantitative techniques are recommended for clinical research. HHD may be an ideal balance between equipment and time costs and accuracy. |

| Functional status | |||

| ALSFRS-R | Clinically meaningful index; minimal training requirements; universal applicability | Statistical manipulation required to handle data after death; clinical heterogeneity distorts the link between total score and disease severity | ALSFRS-R provides useful guidance on patient progression. Composite measures may be better suited to trial design to reduce cost, duration, and patient recruitment burdens. |

| CAFS | Increases statistical power; improves statistical treatment of patient death; simultaneous analysis of 2 important endpoints (survival and function) | Clinically intangible | |

| Respiratory function | |||

| VC | Widely available portable equipment; well-developed normative data | May not be reliable in patients with bulbar or facial weakness; affected by submaximal effort; may not be sensitive to detect mild to moderate respiratory muscle weakness; affected by chest wall and airway factors | SNIP balances ease of recording, reliability, and accuracy and hence may be the optimal approach. |

| MIP | Portable equipment; more sensitive to early respiratory weakness than FVC | May not be reliable in patients with bulbar or facial weakness; | |

| SNIP | Can be performed reliably in most ALS patients, including those with orofacial weakness; predicts respiratory failure more accurately than VC and MIP | ||

| Inspiratory esophageal pressure and trnsdiaphragmatic pressure | Most accurate measurement of respiratory muscle strength | Invasive procedure intolerable to some patients; equipment setup not available in all centers | |

| Surrogate markers of LMN loss | |||

| Nerve conduction studies | Necessary operator experience and equipment widely available | Influenced by reinnervation changes and not a direct reflection of LMN loss; nonlinear | The ideal approach to quantify LMN loss has not been determined. MUNE has been extensively studied and is the most direct measure of LMN loss, but limitations have prevented its universal application. Consensus regarding the optimum MUNE technique, and simplification or automation of data acquisition and analysis will facilitate the widespread incorporation of MUNE into multicenter trials. Novel approaches including EIM and peripheral nerve diffusion tensor imaging may hold promise for future clinical studies. |

| MUNE | Direct measurement of LMN loss | Studies can be time consuming; training requirements are substantial | |

| Nerve excitability studies | Automated data recording; detailed physiological information regarding axonal function | Complex data analysis; necessary equipment and expertise presently limited to selected centers | |

| EIM | Easy to acquire recordings and analyze data; relatively rapid to perform; multiple muscle recordings; relatively linear change with progression | Measurements influenced by age and gender, subcutaneous fat distribution, and muscle changes from immobility; indirect measurement of LMN loss | |

| Muscle ultrasound | Quick and easy to perform; relatively low equipment needs and training requirements; changes detectable in clinically normal muscles | Wide variation in changes with progression; reproducibility of echogenicity measurements may be limited | |

| Surrogate markers of UMN loss | |||

| MRI techniques | Powerful measures of cortical atrophy and neuronal integrity (individual techniques detailed below); may detect and measure asymptomatic UMN involvement | Patients must lie flat in the scanner, which may be difficult if respiratory muscle weakness is present | In the absence of robust clinical UMN scales, a surrogate marker of UMN dysfunction may be considered critical in the design of future clinical trials. Primary motor cortex thickness and DTI of the rostral corticospinal tract may be ideal to provide structural information regarding UMN involvement, and with further development of the technique, TMS may provide important functional data. |

| MRI morphometry (VBM) and SBM | Synchronously evaluates multiple brain territories | Limited sensitivity to gray matter changes on a group level; inconsistent progression data from different longitudinal studies; images are normalized to standard templates, which may smooth out some data signal | |

| DTI | Useful to evaluate corticospinal tract integrity as well as other white matter tracts | Changes may not relate to clinical measures in some studies | |

| MRS | Noninvasive measurement of tissue metabolites | Inconsistent pattern of metabolite changes with disease progression; no standardized approach to analysis; low signal-to-noise ratio and resolution | |

| PET | Provides quantitative functional data; specific ligands may target individual neuronal pools | Exposure to ionizing radiation; requires facilities not available in all centers | |

| TMS | May detect UMN dysfunction in absence of clinical UMN signs; noninvasive; may be performed seated, hence tolerable in patients with respiratory insufficiency | Difficult to perform if severe hand muscle wasting is present; further longitudinal studies are needed |

ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALSFRS-R = revised ALS Functional Rating Scale; CAFS = Combined Assessment of Function and Survival; DTI = diffusion tensor imaging; EIM = electrical impedance myography; FVC = forced vital capacity; HHD = hand held dynamometry; LMN = lower motor neuron; MIP = maximal inspiratory pressure; MMT = manual muscle strength testing; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MRS = magnetic resonance spectroscopy; MUNE = motor unit number estimation; MVIC = maximal voluntary isometric contraction; PET = positron emission tomography; SBM = surface-based morphometry; SNIP = sniff nasal inspiratory pressure; TMS = transcranial magnetic stimulation; UMN = upper motor neuron; VBM = voxel-based morphometry; VC = vital capacity.

Improved survival, typically defined as survival without tracheostomy or permanent assisted ventilation, is clearly an important objective for a proposed treatment in ALS. However, obtaining meaningful change in these indices may prolong trial duration, increase sample size and cost, and be influenced by variation in respiratory intervention and end-of-life care at different institutions. Some ALS treatment trials have reported relatively few survival events, which may partly reflect patient selection bias. That is, end-stage patients, such as those with substantial respiratory involvement or those too unwell to attend to the requirements of trial follow-up, may not be referred to a trial center or may be ineligible for enrollment. Conversely, limiting trial entry to those patients with disease duration less than a specified cutoff, for example 24 months, may eliminate those patients with longer disease duration and slower progression. As such, patient selection factors may skew the phenotypes of included trial participants and thereby influence survival data.

Functional Assessments

Survival measures may also be insensitive to potentially significant changes in functional status. All of the major trials in ALS have included a functional scale as a primary or secondary endpoint. The revised ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS-R) is most commonly used, and evaluates symptoms related to bulbar, limb, and respiratory function,20 and the rate of change may predict survival.21 However, metric analysis of the ALSFRS-R has suggested that it may not be an ideal measure of global function.22 In addition, statistical handling of functional data after death is difficult.23 Composite primary measures, such as the Combined Assessment of Function and Survival (CAFS), have been proposed.24 The CAFS utilizes a unique approach, by ranking patients' clinical outcomes by combining survival time and change in the ALSFRS-R. Such composite endpoints may provide a more statistically robust measurement of clinical response than survival and functional data alone, and improve the likelihood of identifying a significant effect with treatment.

Muscle Strength Testing

Muscle strength may be quantified using composite manual muscle testing (MMT) scores, which usually involve averaging measures from multiple muscle groups using the Medical Research Council (MRC) muscle strength grading scale.25 Additional quantitative methods have been used to evaluate muscle strength, including hand-held dynamometry (HHD) and custom measurement apparatus (see Table2)26,27; HHD equipment in particular is inexpensive, and measurements may not be much more time-consuming than MMT. MMT, HHD, and other measures of muscle strength such as maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) demonstrate equivalent inter-rater reliability and reproducibility.28,29

Replacing MMT methods with more objective measurements of muscle strength such as HHD or MVIC in future studies may improve measurement for a number of reasons. For example, the MRC scale is nonlinear, and is particularly insensitive at detecting changes in the range of strength measures covered by scores of 4 and 5 out of 5.30 In contrast, both HHD and MVIC provide relatively linear measurements at different muscle strengths. MMT may be more sensitive to detect change than MVIC, likely due to greater numbers of muscles tested,28 but this limitation of MVIC may be overcome by HHD. With appropriate training, objective muscle strength measurement apparatus may provide a more universal means of assessing changes in muscle strength, remaining relatively independent of examiner and patient factors such as baseline muscle strength.

Respiratory Muscle Strength Testing

Measurement of respiratory function has been included in most major ALS clinical trials, and may be easily performed in the clinic setting using portable spirometry units. Forced vital capacity (FVC) obtained at baseline may predict the rate of progression.31 Maximal inspiratory pressure, sniff nasal inspiratory pressure (SNIP), and supine FVC may be more sensitive than routine seated FVC measurement in detecting respiratory insufficiency in ALS.32,33 Reduction in slow vital capacity was found to be reduced in the treatment arm of the recently completed phase 2 trial of tirasemtiv.34 FVC remains a routine measurement in the clinical care of patients with ALS but is flawed as a quantitative measurement of disease progression, particularly as it is often unreliable in patients with bulbar weakness, and may be insensitive to change in patients with mild to moderate respiratory muscle weakness. SNIP is recommended as a noninvasive measure of respiratory muscle weakness, as it can be performed reliably by most ALS patients, and is more sensitive to change in respiratory muscle strength than FVC.35 Invasive techniques such as esophageal pressures are also accurate but impractical for regular use in the clinic.

Quantifying UMN Involvement

Identifying and quantifying UMN dysfunction has become increasingly important in the understanding and monitoring of ALS progression. However, clinical UMN abnormalities may be difficult to detect in limbs with significant LMN involvement, and pathological reflexes such as the Babinski sign may be unexpectedly absent in ALS patients.36 Validated clinical UMN scores remain lacking, and imaging and neurophysiological techniques may hold greater promise as tools to quantify UMN dysfunction.

Candidate Biomarkers of Disease Progression

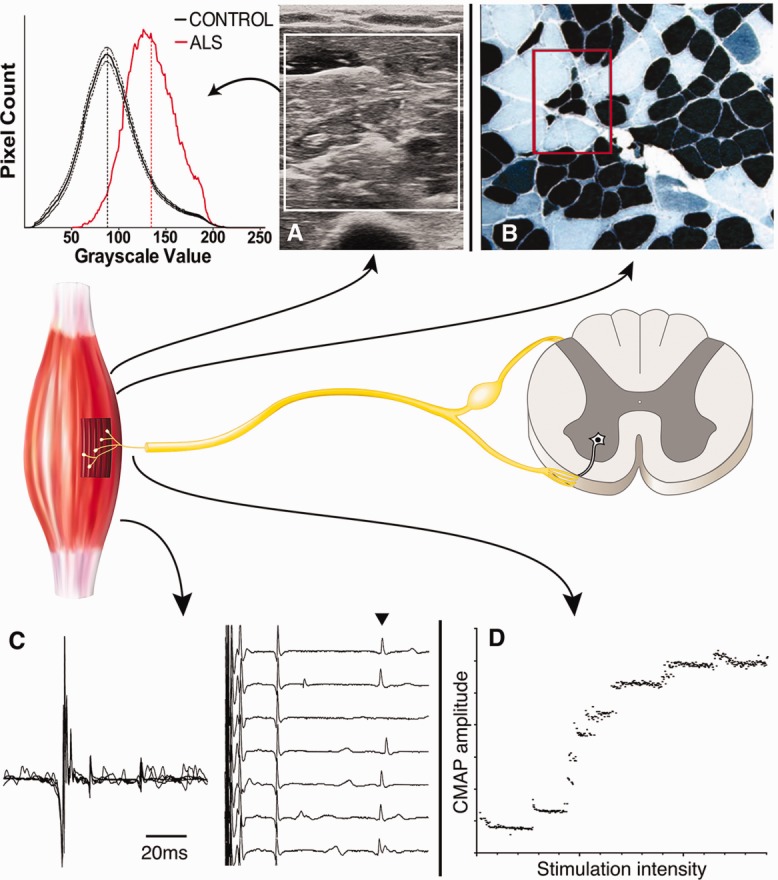

Clinical and functional measures alone may not be adequate indicators of the biological activity of the disease. Muscle reinnervation initially compensates for LMN loss (Fig 1), and substantial motor neuron degeneration may have already occurred prior to the development of clinical weakness,37,38 making change in muscle strength or other clinical indices potentially insensitive to significant changes in the motor neuron pool. In addition, UMN degeneration is not readily quantified by clinical means.

Figure 1.

Markers of lower motor neuron loss. Illustration of the motor unit, comprising the anterior horn cell in the spinal cord projecting to innervate a group of muscle fibers. Methods used to measure loss of anterior horn cells are depicted. (A) Muscle ultrasound may show increased muscle echogenicity and reduced muscle thickness. A grayscale histogram derived from the depicted ultrasound image shows the distribution of grayscale values (red curve), superimposed onto average (± standard deviation) grayscale histograms of 44 normal control subjects (black curves). (B) Ultrasound changes reflect histopathological abnormalities with fiber-type grouping, suggesting reinnervation, and grouped atrophy (red box), suggesting motor neuron loss, typical of motor neuron diseases. (C) These muscle denervation and reinnervation changes may be identified on electromyography, with prolongation of individual motor units, as a result of dyssynchrony of muscle fiber firing secondary to poorly myelinated regenerating branches. Jitter and block of muscle fiber action potentials may be seen as a result (arrowhead). (D) Anterior horn cell loss, independent of muscle reinnervation changes, may be quantified using motor unit number estimation techniques, in this instance using an incremental stimulation technique. ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CMAP = compound muscle action potential.

A biomarker is a laboratory measurement intended as a substitute for survival endpoints or a clinically relevant functional outcome in therapy trials, and will ideally reflect the underlying biology of the disease. The FDA defines 4 categories of clinical biomarkers: diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, and pharmacodynamic.39 A diagnostic biomarker is a disease characteristic that can be used to categorize patients. Prognostic biomarkers are baseline characteristics that inform about the natural history of the disease in the absence of therapy. A predictive biomarker is a disease characteristic that categorizes patients according to their likelihood of treatment response. Finally, pharmacodynamics biomarkers are measures that indicate a treatment effect.

An issue at present is that there are no validated biomarkers in ALS.40,41 In ALS, the use of batteries of biomarkers to measure disease burden may provide more accurate and complete assessments of disease progression than clinical indices alone, and diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, and pharmacodynamics measures may all be relevant. Selected batteries would ideally reflect the complexity of motor system involvement in ALS. Existing and emerging markers of disease progression are discussed below, and strengths and limitations of each method are detailed (see Table2).

Measures of LMN Loss

Electrodiagnostic Studies

Electrodiagnostic studies have an important role to play in the diagnosis of ALS, and may be useful to exclude mimic disorders such as multifocal motor neuropathy.42 Disease progression in ALS is associated with progressive reduction of compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) on motor nerve conduction studies (NCS).43 Motor NCS parameters, specifically distal motor latency, CMAP amplitude, and F-wave frequency, may be used to derive the Neurophysiological Index,44 which is sensitive to disease progression and may be appropriate as an outcome measure particularly in ALS clinical trials conducted over short time periods.45 However, CMAP amplitude is also influenced by compensatory reinnervation, making it a suboptimal estimate of LMN loss.

Motor Unit Number Estimation

Motor unit number estimation (MUNE) is a neurophysiological tool that aims to quantify residual motor axons supplying a muscle, by estimating the contribution of individual motor units to the maximal CMAP response (see Fig 1). A number of MUNE techniques have been developed, but there is as yet no consensus on the optimum methodology. Longitudinal studies of changes in MUNE in ALS have correlated loss of motor neurons with survival.46

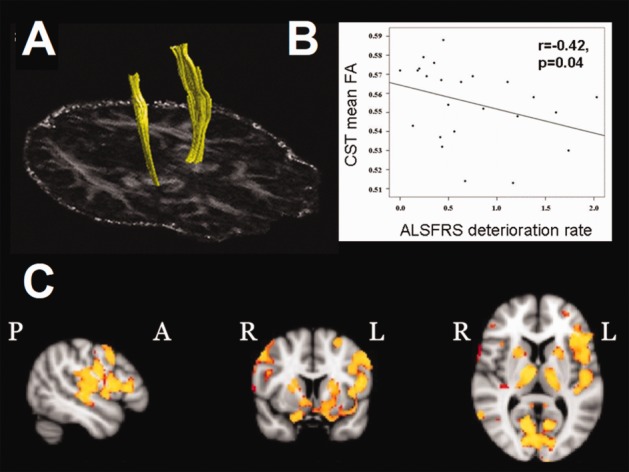

Figure 2.

Brain imaging markers of disease. (A) The corticospinal tracts (CST) can be reconstructed using diffusion tensor tractography. (B) A scatterplot of the extracted mean CST fractional anisotropy (FA) against the rate of decline of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS) score (points per month) shows a negative correlation, with potential to prognostically stratify patients (adapted from Fig 3 in Turner et al64). (C) Longitudinal gray matter changes are extensive in ALS, detected using voxel-based morphometry. They include extramotor frontal lobe regions and basal ganglia (regions of significantly reduced gray matter density common to a large group of ALS patients over time, shown in yellow–red scale overlaid on standard brain image in 3 planes, with anterior [A], posterior [P], right [R], and left [L] marked).

The concept of motor unit number estimation was developed in 1971 by McComas et al,47 who estimated MUNE as the ratio of the maximal CMAP divided by the average single motor unit potential (SMUP). In this early work, incremental stimulation was used to determine the average SMUP; however, this technique may result in alternate or summative activation of units of similar thresholds and as such may overestimate motor unit numbers. To avoid this problem, the multiple point stimulation technique was developed, whereby SMUPs are collected by stimulating different points of the nerve with the resulting average SMUP used to calculate MUNE.48 An alternative technique, the statistical method, does not involve collecting individual SMUPs, but rather statistical handling of steps in amplitude on incremental stimulation.49,50 Additional methods analyze the interference pattern of motor units recorded over the surface of the muscle.51,52

MUNE has shown good inter-rater and test–retest reliability53 but does require substantial operator training. MUNE was incorporated as a secondary endpoint in a clinical trial of creatine in ALS.54 In this trial, an intrarater test–retest variability of up to 20% was accepted, which may be expected to blunt the sensitivity of MUNE to detect smaller treatment effects, and which compares unfavorably with variability in FVC measurements (5%), but is similar to the variability of maximal voluntary isometric contraction muscle strength measurements (up to 17%).26 Newer nerve stimulation and analysis methods, such as multipoint incremental stimulation, motor unit number index, and Bayesian methods of statistical analysis, overcome a specific issue in ALS, which is variability of individual motor units with repeated stimulation, a result of conduction failure in immature regenerating nerve terminals from attempts at reinnervation, which may confound MUNE calculated using early statistical techniques.55

Nerve Excitability

Motor axonal dysfunction has been demonstrated in ALS patients using threshold-tracking nerve excitability studies, with increased persistent Na+ conductance and reduced K+ conductance identified.56 Changes in axonal excitability evolve with disease progression,57 and may be a predictor of survival in ALS patients.58 Axonal excitability parameters may be useful biomarkers of axonal degeneration.

Electrical Impedance Myography

Electrical impedance myography (EIM)59 is an emerging technology that relies on the strong directional dependence of current flows in muscle. EIM demonstrates good test–retest reliability, and changes in EIM measurements in ALS patients may be detected from muscles that are not yet clinically involved. Power calculations suggest that EIM may be superior to MUNE and manual muscle strength testing for the detection of deterioration in ALS,60 and EIM shows promise as a biomarker for future clinical trials.

Muscle Ultrasound

Presently, the most established role of ultrasound in the ALS clinic relates to the identification of fasciculations.61 Ultrasound may also detect changes in the thickness and echogenicity in muscles (see Fig 1) with and without clinical weakness,61 which may provide supplementary evidence of muscle denervation. Muscle changes vary considerably with disease progression.62 Muscle ultrasound is a relatively easy skill to acquire,63 but variability of ultrasound measurements between different ultrasound systems, in particular muscle echogenicity, presently limits its applicability in multicenter studies.

Measures of UMN Dysfunction

Imaging of Brain and Spinal Cord

The clinical syndrome of ALS and its continuum partner frontotemporal dementia are, along with other neurodegenerations, emerging as systems-level, network-based cerebral disorders. Neuroimaging, led by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is poised to deliver biomarkers as part of a deeper understanding of brain structure and function. Routine clinical MRI for the exclusion of alternative pathology does not reveal reliable markers for ALS. Corticospinal tract T2-weighted hyperintensities have limited specificity (<70%) but lack sensitivity (<40%). However, advanced applications of MRI, and ligand-based positron emission tomography (PET) have generated several candidates with potential as a quantitative biomarkers of disease activity and progression (Table3).64

Table 3.

Potentially Quantifiable Cerebral Neuroimaging Markers in ALS

| Quantifiable Neuroimaging Marker | Main Locations |

Key References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Sectional | Longitudinal | ||

| MRI | |||

| Gray matter density reduction (VBM) | PMC | PMC, frontotemporal cortex | 105–107 |

| Cortical thinning (SBM) | PMC | PMC, temporal cortex | 108–109 |

| Decreased fractional anisotropy, increased radial/mean diffusivity (DTI) | CST, CC, cervical cord | CST, CC, frontotemporal tracts, cervical cord | 107, 110–114 |

| N-acetylaspartate (MRS) | PMC | PMC | 11a116 |

| PET | |||

| Microglial activation (11C-PK11195; 18F-DPA-714) | PMC, thalamus, pons, DLPFC | — | 117–118 |

| Reduced GABAA receptor binding (11C-flumazenil) | PMC, premotor | — | 119 |

| Reduced 5-HT1A receptor binding (11C-WAY100635) | Frontotemporal cortex | — | 120 |

-HT = 5-hydroxytryptamine; ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CC = corpus callosum; CST = corticospinal tract; DLPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; DTI = diffusion tensor imaging; GABA = γ-aminobutyric acid; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MRS = magnetic resonance spectroscopy; PMC = primary motor cortex; SBM = surface-based morphometry; VBM = voxel-based morphometry.

Although motor symptoms are the hallmark of ALS, macroscopic atrophy of the motor cortex is typically confined to very rare cases of PLS. However, computerized MRI segmentation techniques have proved more sensitive in the whole brain assessment of cortical changes in ALS. Voxel-based morphometry detects regional gray matter density, and surface-based morphometry differences in a range of topographical measures across a reconstructed cortical ribbon. In broad terms, both techniques consistently demonstrate atrophy of the primary motor cortex in ALS, most strongly linked to clinical UMN involvement, and more variably to measures of disability. Evidence of frontotemporal cortical involvement has been less consistent in its location across studies, but temporal lobe cortical thinning has been linked to more rapid disease progression, in keeping with independent observations about cognitive involvement and prognosis.15

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) assesses the directional movement of water within the white matter, which is highly restricted (anisotropic) when confined within intact neuronal pathways, but able to move more freely in multiple directions (isotropic) where there are damaged tracts. DTI measures are quantifiable. The most consistent abnormalities in ALS are reduced fractional anisotropy and the related measures of increased radial and mean diffusivity, typically within the rostral corticospinal tracts and interhemispheric motor fibers of the corpus callosum, with a less consistently observed longitudinal change than cortical measures. Increasingly, there appears to be merit in the extension of DTI to the spinal cord,65 where there may be useful markers of LMN involvement in addition.66

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy allows the detection and quantification of tissue metabolites, typically within a small region of interest, but more recently using whole brain techniques. N-Acetylaspartate, a nonspecific marker of neuronal damage, is among the most easily identifiable metabolite peaks to quantify, and is consistently reduced in the primary motor cortex in ALS.

Finally, PET is a highly quantifiable technique, and specific receptor ligands, including those for microglial activation, and γ-aminobutyric acidergic and serotonergic systems have all demonstrated specific patterns of binding in ALS.

Structural MRI analysis relies on the normalization of the natural variations in brain size and shape to fit a predefined spatial template and allow standardized comparisons to be made at a group level. Such image transformations inevitably smooth away some of the potentially deeper phenotyping markers at the individual patient level. More focused multivariate region of interest analysis, larger control banks (perhaps based on disease mimics rather than healthy individuals), with standardization and harmonization of sequence acquisition and analysis, are all future steps on a roadmap to clinical translation.67

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is able to improve the sensitivity of ALS diagnosis by demonstrating evidence of UMN dysfunction. Changes in cortical excitability may precede the development of muscle weakness in ALS.68,69 TMS may also be a useful tool for monitoring the effect of therapy (eg, riluzole)70 and the progression of UMN abnormalities in ALS, although further longitudinal studies are required to determine the nature of the changes over time. Hand muscles are frequently studied, and TMS becomes technically difficult if CMAP amplitudes fall below approximately 1mV. Hence, hand muscle atrophy with disease progression precludes longitudinal assessment with TMS in some patients. Like other techniques described here, there are equipment and training barriers to overcome.

Fluid Biomarkers

There has been vigorous interest in identifying biomarkers in biofluids of patients with ALS, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood, and urine. Such biomarkers may serve as a means of distinguishing ALS from mimic disorders, for the purposes of prognostication, disease monitoring, and monitoring drug effects in treatment trials.

Protein-based biomarkers identified in ALS typically reflect neuronal loss or changes in inflammatory pathways. Neurofilament proteins may increase following axonal injury, and high levels have been identified in CSF and plasma of ALS patients.71 Patients with more advanced disease show higher levels of antibodies against neurofilament proteins than those with earlier disease.72 Serial neurofilament protein levels with disease progression reflect the speed of neurological decline and survival.73 Conversely, TDP-43 decreases in the CSF with disease progression.74 Concentrations of CSF glial activation markers correlate with survival time.75

Nonprotein biomarkers may also be of value. Serum creatinine represents a simple and inexpensive estimate of whole body muscle mass, although its concentration in the serum may be affected by renal dysfunction. More detailed metabolic signatures may be identified with proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy metabolomics of fluids such as CSF from ALS patients.76

Several small studies have explored panels of plasma and CSF biomarkers as a means to predict disease progression and to distinguish ALS patients from controls.77–79 These studies have identified inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and markers of iron metabolism as possible markers of disease. Although the link between these markers and disease pathogenesis is unclear, further exploration of CSF and plasma biomarker panels in larger ALS studies may provide important prognostic biomarkers and measures to evaluate treatment response.

Implications for Clinical Trial Design

More detailed understanding of genetic and pathophysiological mechanisms in ALS has drawn advances in symptomatic and disease-modifying therapy to the horizon. However, with this expansion of opportunity there comes a considerable need to rationalize the process of therapy development.

Accurate phenotypic classification and balancing treatment groups for different phenotypic subtypes may prevent the skewing of disease progression data in clinical trials due to expected variation in the natural history. Clinical trials have separated patients into bulbar and spinal subtypes, defined by the region of onset, in an attempt to balance the phenotypic representation between treatment groups. However, methods of phenotypic classification clearly need revision. For example, 1 study identified 5 phenotypic clusters, 1 of which had no deaths, 1 with a median survival of 14 years, and another with a median survival of 8 years.80 As such, simply dividing patients into bulbar and spinal onset may neglect substantial phenotypic variation within those subgroups.

There is clearly a need to better define ALS populations beyond clinical classification, and this will require a greater effort to identify and validate disease-relevant biomarkers. Such biomarkers must also be applied in the appropriate clinical trial context. For example, whereas repeated neuroimaging for quantification of fractional anisotropy in a large multicenter phase 3 study may be impracticable, such a measurement could be exceedingly important in establishing efficacy in a smaller phase 2 study. This concept of “fit for purpose” is important when considering the optimum approach to clinical trial design.

Comprehensive characterization of patients entered into clinical trials including genetic delineation will be critically important to facilitate widespread clinical application of drug discovery efforts through efficient clinical trial design. International collaborative efforts and the mandatory integration of biomarker components to all future therapeutic trials will inevitably advance these aims.81

Acknowledgments

N.G.S. gratefully acknowledges funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Motor Neurone Disease Research Institute of Australia (grant #1039520). This work was supported by funding to Forefront, a collaborative research group dedicated to the study of motor neuron disease, from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Program Grant (#1037746). Support from the ALS Association and MND Association is gratefully acknowledged.

Authorship

N.G.S.: study design, literature review, drafting and revising the manuscript, preparation of figures. M.R.T.: drafting the neuroimaging section, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, preparation of figures. S.V.: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, preparation of figures. A.A.-C.: drafting the genetics section, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.S.: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. C.L.-H.: drafting the motor unit number estimation section, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. M.C.K.: study supervision, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

S.V.: consultancy, Biogen, Bayer Schering. J.S.: board membership, Biogen advisory board; consultancy, Cytokinetics, GlaxoSmithKline; grants/grants pending, ALS Association, Muscular Dystrophy Association, NIH.

References

- 1.Ravits J, Paul P, Jorg C. Focality of upper and lower motor neuron degeneration at the clinical onset of ALS. Neurology. 2007;68:1571–1575. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260965.20021.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujimura-Kiyono C, Kimura F, Ishida S. Onset and spreading patterns of lower motor neuron involvements predict survival in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:1244–1249. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300141. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekiguchi T, Kanouchi T, Shibuya K. Spreading of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis lesions—multifocal hits and local propagation? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:85–91. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305617. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon NG, Lomen-Hoerth C, Kiernan MC. Patterns of clinical and electrodiagnostic abnormalities in early amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mus.24244. Mar 20. doi: 10.1002/mus.24244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roche JC, Rojas-Garcia R, Scott KM. A proposed staging system for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2012;135:847–852. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr351. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balendra R, Jones A, Jivraj N. Use of clinical staging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis for phase 3 clinical trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306865. et al. Jan 24. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Chalabi A, Hardiman O. The epidemiology of ALS: a conspiracy of genes, environment and time. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:617–628. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talbot K. Motor neuron disease: the bare essentials. Pract Neurol. 2009;9:303–309. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.188151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vucic S, Kiernan MC. Abnormalities in cortical and peripheral excitability in flail arm variant amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:849–852. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.105056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon PH, Cheng B, Katz IB. The natural history of primary lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2006;66:647–653. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000200962.94777.71. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenfeld J, Swash M. What's in a name? Lumping or splitting ALS, PLS, PMA, and the other motor neuron diseases. Neurology. 2006;66:624–625. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000205597.62054.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abel O, Powell JF, Andersen PM, Al-Chalabi A. ALSoD: a user-friendly online bioinformatics tool for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1345–1351. doi: 10.1002/humu.22157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen PM, Al-Chalabi A. Clinical genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what do we really know? Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:603–615. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrne S, Elamin M, Bede P. Cognitive and clinical characteristics of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis carrying a C9orf72 repeat expansion: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:232–240. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70014-5. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elamin M, Bede P, Byrne S. Cognitive changes predict functional decline in ALS: a population-based longitudinal study. Neurology. 2013;80:1590–1597. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828f18ac. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su XW, Broach JR, Connor JR. Genetic heterogeneity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: implications for clinical practice and research. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49:786–803. doi: 10.1002/mus.24198. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renton AE, Chio A, Traynor BJ. State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:17–23. doi: 10.1038/nn.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prize4Life and Neurological Clinical Research Institute MGH. Pooled Resource Open-Access ALS Clinical Trials database. 2014. Available at: 2014. https://nctu.partners.org/ProACT. Accessed July 22,

- 19.Williams KL, Fifita JA, Vucic S. Pathophysiological insights into ALS with C9ORF72 expansions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:931–935. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304529. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (phase III) J Neurol Sci. 1999;169:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00210-5. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura F, Fujimura C, Ishida S. Progression rate of ALSFRS-R at time of diagnosis predicts survival time in ALS. Neurology. 2006;66:265–267. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194316.91908.8a. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franchignoni F, Mora G, Giordano A. Evidence of multidimensionality in the ALSFRS-R scale: a critical appraisal on its measurement properties using Rasch analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:1340–1345. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304701. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry JD, Cudkowicz ME. New considerations in the design of clinical trials for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Invest. 2011;1:1375–1389. doi: 10.4155/cli.11.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry JD, Miller R, Moore DH. The Combined Assessment of Function and Survival (CAFS): a new endpoint for ALS clinical trials. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:162–168. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2012.762930. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medical Research Council. Aid to the examination of the peripheral nervous system. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1976

- 26.Goonetilleke A, Modarres-Sadeghi H, Guiloff RJ. Accuracy, reproducibility, and variability of hand-held dynamometry in motor neuron disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:326–332. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.3.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andres PL, Hedlund W, Finison L. Quantitative motor assessment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1986;36:937–941. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.937. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Great Lakes ALS Study Group. A comparison of muscle strength testing techniques in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2003;61:1503–1507. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000095961.66830.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andres PL, Skerry LM, Thornell B. A comparison of three measures of disease progression in ALS. J Neurol Sci. 1996;139(suppl):64–70. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(96)00108-6. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whittaker RG, Ferenczi E, Hilton-Jones D. Myotonic dystrophy: practical issues relating to assessment of strength. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:1282–1283. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.099051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Czaplinski A, Yen AA, Appel SH. Forced vital capacity (FVC) as an indicator of survival and disease progression in an ALS clinic population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:390–392. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumann F, Henderson RD, Morrison SC. Use of respiratory function tests to predict survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;11:194–202. doi: 10.3109/17482960902991773. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fitting J-W, Paillex R, Hirt L. Sniff nasal pressure: a sensitive respiratory test to assess progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:887–893. et al. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Library of Medicine. 2014. . Cytokinetics. Study of safety, tolerability & efficacy of CK-2017357 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). 2000. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01709149. Accessed March 20, [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Lyall RA, Donaldson N, Polkey MI. Respiratory muscle strength and ventilatory failure in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2001;124:2000–2013. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.10.2000. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swash M. Why are upper motor neuron signs difficult to elicit in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:659–662. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wohlfart G. Collateral regeneration in partially denervated muscles. Neurology. 1958;8:175–180. doi: 10.1212/wnl.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krarup C. Lower motor neuron involvement examined by quantitative electromyography in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry and FDA staff: qualification process for drug development tools. 2014. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM230597.pdf. Accessed July 29 2014.

- 40.Katz R. Biomarkers and surrogate markers: an FDA perspective. NeuroRx. 2004;1:189–195. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turner MR, Kiernan MC, Leigh PN, Talbot K. Biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:94–109. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70293-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon NG, Ayer G, Lomen-Hoerth C. Is IVIg therapy warranted in progressive lower motor neuron syndromes without conduction block? Neurology. 2013;81:2116–2120. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000437301.28441.7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cornblath DR, Kuncl RW, Mellits ED. Nerve conduction studies in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:1111–1115. doi: 10.1002/mus.880151009. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Carvalho M, Swash M. Nerve conduction studies in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:344–352. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200003)23:3<344::aid-mus5>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheah BC, Vucic S, Krishnan AV. Neurophysiological index as a biomarker for ALS progression: validity of mixed effects models. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12:33–38. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2010.531742. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Felice KJ. A longitudinal study comparing thenar motor unit number estimates to other quantitative tests in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:179–185. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199702)20:2<179::aid-mus7>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McComas AJ, Fawcett PR, Campbell MJ, Sica RE. Electrophysiological estimation of the number of motor units within a human muscle. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1971;34:121–131. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.34.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kadrie HA, Yates SK, Milner-Brown HS, Brown WF. Multiple point electrical stimulation of ulnar and median nerves. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:973–985. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.39.10.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winhammar JMC, Rowe DB, Henderson RD, Kiernan MC. Assessment of disease progression in motor neuron disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:229–238. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ridall PG, Pettitt AN, Henderson RD, McCombe PA. Motor unit number estimation—a Bayesian approach. Biometrics. 2006;62:1235–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nandedkar SD, Nandedkar DS, Barkhaus PE, Stalberg EV. Motor unit number index (MUNIX) IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2004;51:2209–2211. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.834281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boe SG, Stashuk DW, Doherty TJ. Motor unit number estimation by decomposition-enhanced spike-triggered averaging: control data, test-retest reliability, and contractile level effects. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29:693–699. doi: 10.1002/mus.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shefner JM, Watson ML, Simionescu L. Multipoint incremental motor unit number estimation as an outcome measure in ALS. Neurology. 2011;77:235–241. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225aabf. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shefner JM, Cudkowicz ME, Schoenfeld D. A clinical trial of creatine in ALS. Neurology. 2004;63:1656–1661. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142992.81995.f0. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jillapalli D, Shefner JM. Single motor unit variability with threshold stimulation in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and normal subjects. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:578–584. doi: 10.1002/mus.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vucic S, Kiernan MC. Axonal excitability properties in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:1458–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheah BC, Lin CS, Park SB. Progressive axonal dysfunction and clinical impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123:2460–2467. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2012.06.020. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kanai K, Shibuya K, Sato Y. Motor axonal excitability properties are strong predictors for survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:734–738. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301782. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rutkove SB, Aaron R, Shiffman CA. Localized bioimpedance analysis in the evaluation of neuromuscular disease. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:390–397. doi: 10.1002/mus.10048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rutkove SB, Zhang H, Schoenfeld DA. Electrical impedance myography to assess outcome in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinical trials. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:2413–2418. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.08.004. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arts IM, Overeem S, Pillen S. Muscle ultrasonography: a diagnostic tool for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123:1662–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.11.262. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arts IM, Overeem S, Pillen S. Muscle changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a longitudinal ultrasonography study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.07.023. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zaidman CM, Wu JS, Wilder S. Minimal training is required to reliably perform quantitative ultrasound of muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2014;50:124–128. doi: 10.1002/mus.24117. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turner MR, Agosta F, Bede P. Neuroimaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biomark Med. 2012;6:319–337. doi: 10.2217/bmm.12.26. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bede P, Bokde AL, Byrne S. Spinal cord markers in ALS: diagnostic and biomarker considerations. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13:407–415. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2011.649760. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cohen-Adad J, El Mendili MM, Morizot-Koutlidis R. Involvement of spinal sensory pathway in ALS and specificity of cord atrophy to lower motor neuron degeneration. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:30–38. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2012.701308. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turner MR, Grosskreutz J, Kassubek J. Towards a neuroimaging biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:400–403. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70049-7. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vucic S, Nicholson GA, Kiernan MC. Cortical hyperexcitability may precede the onset of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2008;131:1540–1550. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vucic S, Kiernan MC. Novel threshold tracking techniques suggest that cortical hyperexcitability is an early feature of motor neuron disease. Brain. 2006;129:2436–2446. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vucic S, Lin CS, Cheah BC. Riluzole exerts central and peripheral modulating effects in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2013;136:1361–1370. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt085. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brettschneider J, Petzold A, Sussmuth SD. Axonal damage markers in cerebrospinal fluid are increased in ALS. Neurology. 2006;66:852–856. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000203120.85850.54. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Puentes F, Topping J, Kuhle J. Immune reactivity to neurofilament proteins in the clinical staging of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:274–278. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305494. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu C-H, Petzold A, Topping J. Plasma neurofilament heavy chain levels and disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from a longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307672. et al. Jul 9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steinacker P, Hendrich C, Sperfeld AD. TDP-43 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1481–1487. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1481. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sussmuth SD, Sperfeld AD, Hinz A. CSF glial markers correlate with survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;74:982–987. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d5dc3b. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blasco H, Corcia P, Moreau C. 1H-NMR-based metabolomic profiling of CSF in early amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PloS One. 2010;5:e13223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013223. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mitchell RM, Simmons Z, Beard JL. Plasma biomarkers associated with ALS and their relationship to iron homeostasis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42:95–103. doi: 10.1002/mus.21625. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mitchell RM, Freeman WM, Randazzo WT. A CSF biomarker panel for identification of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2009;72:14–19. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000333251.36681.a5. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Su XW, Simmons Z, Mitchell RM. Biomarker-based predictive models for prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1505–1511. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4646. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ganesalingam J, Stahl D, Wijesekera L. Latent cluster analysis of ALS phenotypes identifies prognostically differing groups. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007107. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bruijn L, Cudkowicz M The ALSCTWG. Opportunities for improving therapy development in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15:169–173. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2013.872662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sabatelli M, Zollino M, Luigetti M. Uncovering amyotrophic lateral sclerosis phenotypes: clinical features and long-term follow-up of upper motor neuron-dominant ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12:278–282. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2011.580849. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haverkamp LJ, Appel V, Appel SH. Natural history of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a database population. Validation of a scoring system and a model for survival prediction. Brain. 1995;118:707–719. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Georgoulopoulou E, Fini N, Vinceti M. The impact of clinical factors, riluzole and therapeutic interventions on ALS survival: a population based study in Modena, Italy. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:338–345. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2013.763281. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scotton WJ, Scott KM, Moore DH. Prognostic categories for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13:502–508. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2012.679281. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chio A, Mora G, Leone M. Early symptom progression rate is related to ALS outcome: a prospective population-based study. Neurology. 2002;59:99–103. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.1.99. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bourke SC, Tomlinson M, Williams TL. Effects of non-invasive ventilation on survival and quality of life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:140–147. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70326-4. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hu WT, Shelnutt M, Wilson A. Behavior matters—cognitive predictors of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PloS One. 2013;8:e57584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057584. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Elamin M, Phukan J, Bede P. Executive dysfunction is a negative prognostic indicator in patients with ALS without dementia. Neurology. 2011;76:1263–1269. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318214359f. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Desport JC, Preux PM, Truong TC. Nutritional status is a prognostic factor for survival in ALS patients. Neurology. 1999;53:1059–1063. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.1059. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nakamura R, Atsuta N, Watanabe H. Neck weakness is a potent prognostic factor in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:1365–1371. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306020. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Traxinger K, Kelly C, Johnson BA. Prognosis and epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: analysis of a clinic population, 1997-2011. Neurol Clin Pract. 2013;3:313–320. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0b013e3182a1b8ab. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee CT, Chiu YW, Wang KC. Riluzole and prognostic factors in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis long-term and short-term survival: a population-based study of 1149 cases in Taiwan. J Epidemiol. 2013;23:35–40. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20120119. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de Jong SW, Huisman MH, Sutedja NA. Smoking, alcohol consumption, and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:233–239. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws015. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cudkowicz ME, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp PE. Epidemiology of mutations in superoxide dismutase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:210–221. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410212. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Landers JE, Melki J, Meininger V. Reduced expression of the kinesin-associated protein 3 (KIFAP3) gene increases survival in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9004–9009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812937106. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Van Hoecke A, Schoonaert L, Lemmens R. EPHA4 is a disease modifier of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in animal models and in humans. Nat Med. 2012;18:1418–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.2901. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Juneja T, Pericak-Vance MA, Laing NG. Prognosis in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: progression and survival in patients with glu100gly and ala4val mutations in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Neurology. 1997;48:55–57. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.1.55. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Baumer D, Hilton D, Paine SM. Juvenile ALS with basophilic inclusions is a FUS proteinopathy with FUS mutations. Neurology. 2010;75:611–618. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ed9cde. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pinto A, de Carvalho M, Evangelista T. Nocturnal pulse oximetry: a new approach to establish the appropriate time for non-invasive ventilation in ALS patients. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2003;4:31–35. doi: 10.1080/14660820310006706. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Spataro R, Ficano L, Piccoli F, La Bella V. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: effect on survival. J Neurol Sci. 2011;304:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dal Bello-Haas V, Florence JM. Therapeutic exercise for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD005229. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005229.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Traynor BJ, Alexander M, Corr B. Effect of a multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study, 1996–2000. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1258–1261. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1258. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cudkowicz ME, Shefner JM, Schoenfeld DA. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2003;61:456–464. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.4.456. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chang JL, Lomen-Hoerth C, Murphy J. A voxel-based morphometry study of patterns of brain atrophy in ALS and ALS/FTLD. Neurology. 2005;65:75–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167602.38643.29. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kassubek J, Unrath A, Huppertz HJ. Global brain atrophy and corticospinal tract alterations in ALS, as investigated by voxel-based morphometry of 3-D MRI. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2005;6:213–220. doi: 10.1080/14660820510038538. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Senda J, Kato S, Kaga T. Progressive and widespread brain damage in ALS: MRI voxel-based morphometry and diffusion tensor imaging study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12:59–69. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2010.517850. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Verstraete E, Veldink JH, Hendrikse J. Structural MRI reveals cortical thinning in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:383–388. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300909. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kwan JY, Meoded A, Danielian LE. Structural imaging differences and longitudinal changes in primary lateral sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin. 2012;2:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2012.12.003. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Filippini N, MacIntosh BJ, Hough MG. Distinct patterns of brain activity in young carriers of the APOE-epsilon4 allele. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7209–7214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811879106. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Agosta F, Pagani E, Petrolini M. Assessment of white matter tract damage in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a diffusion tensor MR imaging tractography study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1457–1461. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2105. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.van der Graaff MM, Sage CA, Caan MW. Upper and extra-motoneuron involvement in early motoneuron disease: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain. 2011;134:1211–1228. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr016. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Agosta F, Rocca MA, Valsasina P. A longitudinal diffusion tensor MRI study of the cervical cord and brain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:53–55. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.154252. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Valsasina P, Agosta F, Benedetti B. Diffusion anisotropy of the cervical cord is strictly associated with disability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:480–484. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100032. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stagg CJ, Knight S, Talbot K. Whole-brain magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging measures are related to disability in ALS. Neurology. 2013;80:610–615. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318281ccec. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pohl C, Block W, Karitzky J. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the motor cortex in 70 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:729–735. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.5.729. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Turner MR, Cagnin A, Turkheimer FE. Evidence of widespread cerebral microglial activation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an [(11)C](R)-PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.12.012. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Corcia P, Tauber C, Vercoullie J. Molecular imaging of microglial activation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052941. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Turner MR, Hammers A, Al-Chalabi A. Distinct cerebral lesions in sporadic and 'D90A' SOD1 ALS: studies with [11C]flumazenil PET. Brain. 2005;128:1323–1329. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh509. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Turner MR, Rabiner EA, Hammers A. [11C]-WAY100635 PET demonstrates marked 5-HT1A receptor changes in sporadic ALS. Brain. 2005;128:896–905. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh428. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]