Abstract

Children exposed to extreme stress are at heightened risk for developing mental and physical disorders. However, little is known about mechanisms underlying these associations in humans. An emerging insight is that children's social environments change gene expression, which contributes to biological vulnerabilities for behavioral problems. Epigenetic changes in the glucocorticoid receptor gene, a critical component of stress regulation, were examined in whole blood from 56 children aged 11–14 years. Children exposed to physical maltreatment had greater methylation within exon 1F in the NR3C1 promoter region of the gene compared to nonmaltreated children, including the putative NGFI-A (nerve growth factor) binding site. These results highlight molecular mechanisms linking childhood stress with biological changes that may lead to mental and physical disorders.

Individuals who experience severe early life stress, such as child physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect, are at heightened risk for myriad forms of psychopathology related to emotional and behavioral regulation (Kessler et al., 2010). Nearly a million children in the United States are victims of such forms of child maltreatment each year (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Children exposed to extreme levels of stress are likely to develop mood, anxiety, or aggressive disorders, as well as to experience emotion regulation difficulties that disrupt their interpersonal relationships, and impact learning and school functioning. For these reasons, the impact of stress on young children's biobehavioral development represents a major public health concern. Yet few targeted and effective psychological interventions have been designed for these children because we lack knowledge about specific biological systems amenable to change. Therefore, elucidating how early life stress shapes neural, cognitive, and affective functioning to influence development of psychopathology can ultimately inform and improve both prevention and intervention efforts (Shonkoff, Garner, & Wood, 2011).

Child Maltreatment as a Model of Toxic Stress Exposure

Children who are chronically abused experience repeated exposure to severe stress and lack the stability and security that would be afforded by supportive and sensitive parenting. These individuals not only experience more physical and emotional harm than other children but they may also develop interpretations that the world is dangerous and unpredictable (Gibb, 2002). As a result, these children become more likely to attend to threat in their environments, which may serve as a risk factor for both anxiety (Shackman, Shackman, & Pollak, 2007) and aggression (Shackman & Pollak, 2014) problems.

Emerging research indicates that early social environments, including individuals’ subjective perceptions of their environment, produce changes in gene expression (Slavich & Cole, 2013). In this manner, experiences in daily life can effectively “turn on” and “turn off” genes, leading to cascades of downstream changes in biology and behavior. Thus, environmental influences on gene expression may reveal a critical mechanism linking stressful experiences endured by abused children to the development of a host of health problems. For example, disruption of healthy stress regulatory systems might account for issues frequently observed in populations of maltreated individuals, including behavior regulation problems in early childhood, increased incidence of mental and substance-related disorders in emerging adulthood, and high rates of physical health problems later in life.

There is strong reason to focus on epigenetic changes to the glucocorticoid system as underlying stress-related psychopathology. In mammals, perceived physical and social stress produces changes in physiological stress regulation systems that enhance threat detection, increase available energy for intense physical activity (e.g., fight or flight), and heighten immune responses involved in wound repair (Hostinar & Gunnar, 2013). Glucocorticoids, including cortisol, play a critical role in coordinating these responses. When an individual encounters a stressor, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is excreted from the hypothalamus. This hormone acts on the pituitary gland, causing it to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH in turn acts upon the adrenal gland, resulting in the production of cortisol. Cortisol binds with glucocorticoid (GR) receptors in the hippocampus to regulate the HPA axis and inhibit further release of CRH. Similarly, cortisol released in response to stress binds with GR receptors at the cellular level to regulate the immune system (Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009).

At the same time that this system promotes adaptation in response to normative stressors, toxic or extreme levels of stress exposure may impair this system. Epigenetic regulation of the GR gene may thereby serve as a specific mechanism linking child maltreatment with HPA axis dysregulation, and ultimately, development of psychopathology. Indeed, child maltreatment is consistently associated with dysregulation of the HPA axis (Loman & Gunnar, 2010). This dysregulation has been implicated in the etiology of a range of psychological disorders (Heim & Nemeroff, 2001; Heim, Newport, Mletzko, Miller, & Nemeroff, 2008).

Molecular Mechanisms of Stress Exposure

To date, there have been extremely compelling data from nonhuman animal studies indicating an association between parental care and epigenetic regulation of genes involved in HPA axis functioning. Recent research in rodents highlights that poor maternal care causes dysregulation of the HPA axis through altered transcription of the GR gene (Meaney, 2001). The absence of early nurturing maternal behavior in rodents leads to increased methylation, a covalent modification involved in epigenetic regulation of DNA, of exon 17, a NGFI-A regulated promoter of the GR NR3C1 gene (Meaney & Szyf, 2005; Szyf, Weaver, Champagne, Diorio, & Meaney, 2005). Subsequent decreases in NGFI-A binding then leads to decreased levels of GRs in the hippocampus, which results in impaired regulation of stress response systems and behavior (Weaver et al., 2004; Weaver et al., 2005).

Similar associations between early adversity and GR NR3C1 methylation have recently been demonstrated in humans who likely experienced severe stress or trauma. These samples have included brain tissue of deceased human adults who had committed suicide following a history of child abuse (McGowan et al., 2009), cord blood of infants with depressed mothers (Oberlander et al., 2008), white blood cells of adults with borderline personality disorder or major depressive disorder with a history of child sexual abuse (Perroud et al., 2011), whole blood of adults with bipolar disorder and a history of child abuse (Perroud et al., 2014), and whole blood of adolescents whose mothers were exposed to intimate partner violence during pregnancy (Radtke et al., 2011). The results of these studies consistently demonstrated that stress or trauma was correlated with higher methylation of exon 1F of NR3C1, which is the homolog of exon 17 in the rat (Turner, Pelascini, Macedo, & Muller, 2008). This increased methylation would likely contribute to fewer GRs in the brain and blood, thereby impairing the physiology of stress regulation.

Translation of Animal Research to Understanding Risk for Psychopathology in Children

The rodent models of alterations in GR methylation hold great promise for understanding specific mechanisms linking child maltreatment to development of psychopathology. In addition, there is suggestive evidence that these rodent models may be extended to humans. However, these findings have not been tested in or extended to living human children who have recently and definitively endured abusive parenting.

Although there are many parallels in biological systems between humans and nonhuman animals, especially with regard to the HPA axis and glucocorticoid functioning, translation of findings across species must be undertaken with extreme care. In the present study we examined methylation of exon 1F of NR3C1 from leukocytes in children who experienced severe early life stress in the form of verified child abuse. We focused solely upon the homolog regions of the GR gene that have been demonstrated to be susceptible to perturbations in caregiving among rodents, but that have not been examined in living children. GR methylation is an index of gene activation. We tested whether the methylation patterns among children who have recently endured abusive parenting paralleled the effects observed among rodents who experienced poor parental care. Our reasoning was that if precise epigenetic changes appear across species following poor parental care, this would reveal a relatively specific molecular mechanism whereby social experience confers risk of psychopathology.

Method

Participants

Participants were 56 children (30 males, 26 females) aged 11–14 (Mage = 12.11, SDage = 0.78) years. The children's parents identified them as White and non-Hispanic (n = 37), Black (n = 17), or White and Hispanic (n = 2). Families were recruited through newspaper ads, bus ads, and flyers in the community. Families with substantiated cases of child maltreatment were recruited through letters forwarded by the Dane County (WI) Department of Human Services. Participants were recruited from neighborhoods with similar socioeconomic demographics. If more than one child in a family qualified for and was interested in study participation, a sibling was included; the final sample included five sibling pairs. Written assent and consent were obtained for all children and parents, respectively. All parents gave permission for us to access Child Protective Services (CPS) records on their families. These data indicated that 38 participants had no CPS records and 18 participants had reports of physical maltreatment. The children's parents completed the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of Socioeconomic Status (SES–Child; Hollingshead, 1975). This survey measure assesses parents’ marital status, employment status, educational attainment, and occupational prestige to create a composite score to represent SES. Parents of 2 participants (1 in each maltreatment group) did not complete the survey. All experimental procedures were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board and were carried out in accordance with the provisions of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Bisulfite Pyrosequencing

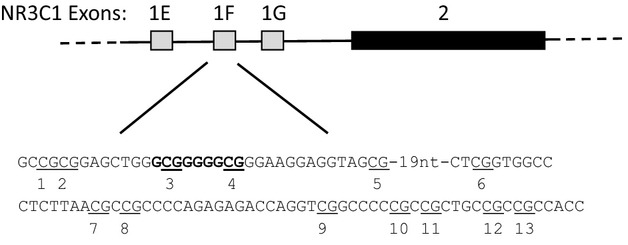

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the Flexigene DNA Blood Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following manufacturer's standard protocol. Samples were stored at −80°C for 1–4 weeks. Samples were converted for methylation sequencing using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). Five hundred nanograms of the bisulfite-converted DNA were amplified by PCR with 2X GoTaq® Hot Start PCR master mix (Promega, Madison, WI) for the target region. The primer (set I forward 5′-GTTTGTAGTTAAGGGGTAGAG-3′, reverse 5′-AAAAACCATACAACCTATTAATAA-3′) was designed for a 150-bp region the NR3C1 gene between −3266 and −3116 relative to the translational start site using PyroMark Assay Design software (Qiagen). See Figure1 for targeted region.

Figure 1.

The diagram depicts three of the alternate first exons of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) adjacent to the major coding exon 2. A 150-bp segment surrounding exon 1F was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing for DNA methylation. Methylation sites are numbered and sites 3 and 4 are within the conserved NGFI-A/EGR1 transcription factor binding site, which is in bold text.

Thermocycler conditions were initial denaturation of 95°C for 10 min, 54 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min, with final extension of 10 min at 72°C. The PCR products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel prior to pyrosequencing analysis. The biotinylated PCR products were immobilized on streptavidin-coated Sepharose® beads (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA), subjected to three different washes, and analyzed with PyroGold® reagents (Qiagen) using sequencing primer 5′-GTTTTAGAGTGGGTTTGGA-3′ on a PSQ 96 MA pyrosequencer (Qiagen). Percent methylation at each CpG site was quantified using Pyro Q-CpG 1.0.9 software (Qiagen). Two technical replicates of bisulfite pyrosequencing provided estimates of the percentage methylation of each CpG island (Dupont, Tost, Jammes, & Gut, 2004).

Analytic Approach

We conducted independent sample t tests and Pearson chi-square tests to determine if maltreatment groups differed in age, sex, race or ethnicity, and SES. Next, we tested our a priori hypothesis by conducting a 2 (maltreatment group; between subjects) × 13 (CpG site; within subjects) mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the relation between child maltreatment and the average percentage methylation across two replications of bisulfite pyrosequencing of each of 13 CpG sites in exon 1F of the NR3C1 promoter. We specifically focused upon the human homologs of the sites that are responsive to maternal behavior and critical for regulation of NR3C1 transcription in rodents (Weaver et al., 2004). The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied to adjust for heterogeneity of covariance. In the presence of a significant interaction between maltreatment group and CpG site, we conducted planned independent samples t tests to examine group differences at each CpG site. When Levene's test for equality of variance indicated unequal variance between groups, we corrected the degrees of freedom using the Welch–Satterthwaite approach. Next, we examined whether socioeconomic differences between the two groups accounted for the observed relation between maltreatment and GR methylation. To do so, we selected a subset of children without maltreatment histories (n = 17) to match the socioeconomic background of the maltreated children (n = 17) and repeated the original mixed ANOVA with this sample subset.

Results

Demographic Differences Between Maltreated and Nonmaltreated Children

Children with a history of maltreatment did not differ in distributions of age, sex, race, or ethnicity than children without a history of maltreatment. However, children with histories of maltreatment had families with lower SES (MSES = 32.65, SDSES = 13.59) compared to children with no maltreatment history (MSES = 47.96, SDSES = 9.74), t(23.86) = 4.18, p < .001, d = 1.71.

Child Maltreatment and Differences in GR Gene Methylation

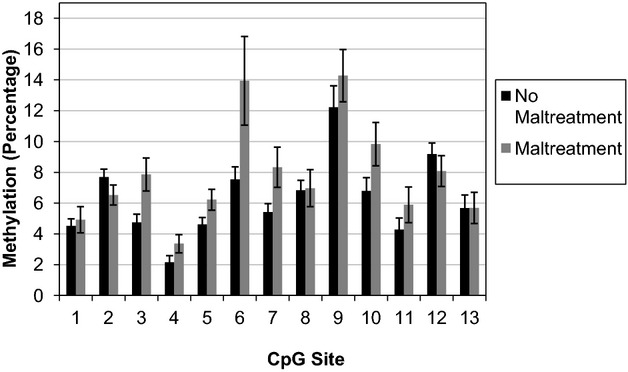

First, we examined whether child maltreatment was associated with differences in methylation of exon 1F in the NR3C1 promoter region of the GR gene. Methylation varied for maltreated children compared to their nonmaltreated peers depending on CpG site, F(6.59, 355.68) = 2.46, p = .02 (see Figure2). Compared to our normative comparison group, children with histories of maltreatment had more methylation at CpG site 3, t(54) = −2.91, p = .01, d = 0.79; CpG site 6, t(19.77) = −2.14, p = .05, d = 0.96; and CpG site 7, t(23.37) = −2.18, p = .05, d = 0.90.

Figure 2.

Mean ± SEM percentage of average methylation of exon 1F the NR3C1 promoter for maltreated (n = 18) and nonmaltreated children (n = 38). Maltreated children had more methylation of CpG sites 3, 6, and 7.

Second, we examined whether the socioeconomic differences between the two groups accounted for the observed relation between maltreatment and GR methylation. In order to address this possible confound, we selected a subset of children without maltreatment histories (n = 17) to match the socioeconomic background of the maltreated children (n = 17). We repeated the original mixed ANOVA and confirmed a similar pattern of results. Methylation varied for maltreated children compared to their nonmaltreated peers depending on CpG site, F(5.33, 170.42) = 2.32, p = .04. Children with histories of maltreatment had more methylation at CpG site 3, t(32) = −3.13, p = .004, d = 1.10; CpG site 5, t(32) = −2.68, p = .01, d = 0.95; and CpG site 6, t(32) = −2.11, p = .04, d = 0.75, compared to children with no maltreatment history. In addition, in this sample subset, children with histories of maltreatment had less methylation at CpG site 2, t(32) = 2.05, p = .048, d = 0.72, compared to children with no maltreatment history.

Discussion

The data from this study revealed that children who experienced physical maltreatment displayed a specific epigenetic change to the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Specifically, these children had more methylation of several sites within exon 1F of the NR3C1 promoter region. Of particular importance, the differences that we observed include a precise part of the gene, CpG site 3, which is part of the putative NGFI-A binding site. NGFI-A (also known as Early Growth Response 1 [EGR1]) is implicated in numerous biological functions, including healthy human brain development (Aloe, Rocco, Bianchi, & Manni, 2012). These findings are consistent with the view that human genes can be “turned on” and “turned off” by life experiences and also opens a window into the molecular mechanisms linking early stress exposure to the emergence of psychopathology. However, the present study cannot directly address causality or the cellular processes occurring within the brains of living children. We address these critical issues next.

A common challenge in studying children at risk is the infeasibility of maintaining tight experimental control or measurement of the possible circumstances that co-occur with stressful lives. In this manner, researchers must be opportunistic, using unfortunate life circumstances to learn as much as possible in the service of prevention and intervention. In this case, it was not possible to include children who had experienced severe early life stress and also control for other possible confounding variables that might co-occur with child abuse. Therefore, our approach was to reap the benefits of a translational approach. We targeted a specific gene (and particular regions within that single gene) that has been shown to be responsive to parental care in tightly controlled nonhuman animal studies. The fact that the data in living human children parallels findings in rodents, and that the rodent experiments directly address potential confounding variables (e.g., predisposing genetic factors, nutrition differences, general environmental stimulation, health) militates against alternative hypotheses. There are also factors relevant only to humans. For these reasons, we analyzed data on a subset of children matched on these features to demonstrate that methylation differences were not due to plausible confounding sociodemographic variables such as parental marital status, employment status, and education. Furthermore, our results are consistent with previous research in adult humans demonstrating an association between child abuse and methylation differences, despite differences in sample characteristics (McGowan et al., 2009; Perroud et al., 2011; Perroud et al., 2014). There is suggestive evidence, therefore, that the current results are not due to the influence of confounding variables. Further research in human children that includes measurement of additional background and environmental factors is needed to strengthen evidence that methylation differences are due to social stress or parental caregiving.

In the current study, we did not examine whether children exposed to child maltreatment exhibited alterations in gene expression, protein synthesis, or behavior related to alterations in GR gene methylation. However, we examined methylation differences in a specific region within a single gene with well-characterized molecular and behavioral consequences in rodents (Weaver et al., 2004; Weaver et al., 2005). In addition, adversity-related increases in methylation in this region are associated with decreased gene expression in human postmortem brain tissue (McGowan et al., 2009) and increased physiological stress responding in infants (Oberlander et al., 2008). The fact that the current data replicate previously demonstrated associations between child maltreatment and methylation of the GR gene suggests that observed methylation differences are likely to have similar functional consequences. Future research using whole blood from maltreated human children can extend these findings to clarify the associations between methylation differences and gene expression and protein synthesis, and extended samples can address issues of physiological stress responding and relevant behavior.

A related issue is that nonhuman animal studies measure epigenetic changes using brain tissue, which is not ethical, feasible, or desirable in living children. It is critical that the results that we observed from blood leukocytes in children are consistent with methylation patterns reported as a result of poor parental care from rodent and human brain tissue. At the same time, methylation patterns in leukocytes (blood) may not have the same function as central methylation in the brain. Methylation patterns derived from leukocytes may also be influenced by other properties, such as stress-induced changes in the proportion of T cells and macrophages in the blood (Uddin et al., 2010); future studies are needed to better understand immunological effects on these cells. Yet, recent research has demonstrated an association between peripheral and central measures of methylation (Provençal et al., 2012). Furthermore, either central or peripheral interpretations of these data represent significant insights regarding children's health. A more liberal interpretation of the data would be that what is observed in leukocytes is reflecting, in part, central epigenetic changes on the GR gene. This would mean that the abused children have fewer glucocorticoid receptors in their brains, which would impair negative feedback of the HPA system and result in stress regulation problems (Heim & Nemeroff, 2001, 2001; Heim et al., 2008). A more conservative position would hold that the epigenetic changes should be interpreted only with regard to the blood and not the brain. Immune responses are regulated via binding to GR receptors in white blood cells, and high methylation of the promoter of the GR receptor gene in the periphery would indicate that the abused children have fewer of these receptors on their white blood cells. This would lead to less cortisol regulation of the immune system and result in higher inflammatory activity in these children. In fact, individuals with maltreatment histories are reported to have elevated inflammation, elevated production of antibodies, compromised immune functioning, and poorer health compared to nonmaltreated individuals (Danese et al., 2008; Shirtcliff, Coe, & Pollak, 2009).

Such a link between early life stress in the form of child maltreatment and adverse mental and physical health outcomes requires continued research aimed at understanding of how social experiences can get “under the skin” and confer lifelong risk (Gilbert et al., 2009). Alterations in GR-mediated regulation of HPA and immune responses could reflect not only an etiological mechanism contributing to poor health, but also a set of processes that could be targeted for tailored and specific interventions for these children. Furthermore, chronic stress exposure may lead children to perceive their environments as threatening and unpredictable, with such beliefs serving as yet another way in which GR gene expression may be altered well beyond the occurrence of environmental stressors (Slavich & Cole, 2013). These data do suggest that social experience can alter human physiology, but do not suggest that such changes are permanent. While the present study was motivated by nonhuman animal research on the effects of poor caregiving on brain development, these animal studies also indicate that epigenetic changes are reversible with intervention in rodents (Weaver et al., 2005). For these reasons, future translational research should continue to build on ways to uncover which mechanisms to target, and how to design and deliver novel interventions for children who have been subjected to toxic levels of early life stress. It may also be the case that there are individual differences in sensitivity to the socioemotional environment, such that certain alleles are associated with a stronger relation between environment and gene expression. This might call for the development of more individualized or personalized psychological interventions for children who have experienced early stress exposure.

In these ways, better understanding of the ways in which social experiences interact with neurobiology will create new perspectives and opportunities for clinicians to lessen the burden of mental illness in at-risk youth and promote positive growth and development in children.

References

- Aloe L, Rocco M, Bianchi P. Manni L. Nerve growth factor: From the early discoveries to the potential clinical use. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2012;10:239. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-239. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Moffitt TE, Pariante CM, Ambler A, Poulton R. Caspi A. Elevated inflammation levels in depressed adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:409–416. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.409. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont JM, Tost J, Jammes H. Gut IG. De novo quantitative bisulfite sequencing using the pyrosequencing technology. Analytical Biochemistry. 2004;333:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.05.007. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE. Childhood maltreatment and negative cognitive styles: A quantitative and qualitative review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:223–246. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00088-5. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E. Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C. Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: Preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01157-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Mletzko T, Miller AH. Nemeroff CB. The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:693–710. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AA. 1975. Four-Factor Index of Social Status. Unpublished manuscript, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

- Hostinar CE. Gunnar MR. The developmental effects of early life stress: An overview of current theoretical frameworks. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22:400–406. doi: 10.1177/0963721413488889. doi: 10.1177/0963721413488889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA. Zaslavsky AM. Williams DR. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197:378–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman MM. Gunnar MR. Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.007. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR. Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behavior and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D'Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonté B, Szyf M. Meaney MJ. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ. Szyf M. Environmental programming of stress responses through DNA methylation: Life at the interface between a dynamic environment and a fixed genome. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2005;7:103–119. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2005.7.2/mmeaney. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S. Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics. 2008;3:97–106. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud N, Dayer A, Piguet C, Nallet A, Favre S, Malafosse A. Aubry J. Childhood maltreatment and methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene NR3C1 in bipolar disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;204:30–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.120055. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.120055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud N, Paoloni-Giacobino A, Prada P, Olié E, Salzmann A, Nicastro R. Malafosse A. Increased methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) in adults with a history of childhood maltreatment: A link with the severity and type of trauma. Translational Psychiatry. 2011;1:e59. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.60. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provençal N, Suderman MJ, Guillemin C, Massart R, Ruggiero A, Wang D. Szyf M. The signature of maternal rearing in the methylome in rhesus macaque prefrontal cortex and T cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:15626–15642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1470-12.2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1470-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke KM, Ruf M, Gunter HM, Dohrmann K, Schauer M, Meyer A. Elbert T. Transgenerational impact of intimate partner violence on methylation in the promoter of the glucocorticoid receptor. Translational Psychiatry. 2011;1:e21. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.21. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman JE. Pollak SD. Impact of physical maltreatment on the regulation of negative affect and aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2014 doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000546. Advance online publication. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman JE, Shackman AJ. Pollak SD. Physical abuse amplifies attention to threat and increases anxiety in children. Emotion. 2007;7:838–852. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.838. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff EA, Coe CL. Pollak SD. Early childhood stress is associated with elevated antibody levels to herpes simplex virus type 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:2963–2967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806660106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806660106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS The Committee on Psychological Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Wood DL. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. The American Academy of Pediatrics. 2011;129:e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavich GM. Cole SW. The emerging field of human social genomics. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1:331–348. doi: 10.1177/2167702613478594. doi: 10.1177/2167702613478594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyf M, Weaver ICG, Champagne FA, Diorio J. Meaney MJ. Maternal programming of steroid receptor expression and phenotype through DNA methylation in the rat. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2005;26:139–162. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.10.002. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JD, Pelascini LPL, Macedo JA. Muller CP. Highly individual methylation patterns of alternative glucocorticoid receptor promoters suggest individualized epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36:7207–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn897. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin M, Aiello AE, Wildman DE, Koenen KC, Pawelec G, de los Santos R. Galea S. Epigenetic and immune function profiles associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:9470–9475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910794107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910794107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Child maltreatment. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver ICG, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D'Alessio AC, Sharma S. Seckl JR. Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver ICG, Champagne FA, Brown SE, Dymov S, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Szyf M. Reversal of maternal programming of stress responses in adult offspring through methyl supplementation: Altering epigenetic marking later in life. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:11045–11054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3652-05.2005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3652-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]