Abstract

Objective

Viral infections are often suspected to cause pediatric acute liver failure (PALF) but large-scale studies have not been performed. We analyzed results of viral testing among non-acetaminophen (non APAP) PALF study participants.

Methods

Participants were enrolled in the PALF registry. Diagnostic evaluation and final diagnosis were determined by the site investigator and methods for viral testing by local standard of care. Viruses were classified as either Causative Viruses (CV) or Associated Viruses (AV). Supplemental testing for CV was performed if not done clinically and serum was available. Final diagnoses included “Viral”, “Indeterminate” and “Other”.

Results

Of 860 participants, 820 had at least one test result for a CV or AV. A positive viral test was found in 166/820 (20.2%) participants and distributed among “Viral” [66/80 (82.5%)], “Indeterminate” [52/420 (12.4%)] and “Other” [48/320 (15.0%)] diagnoses. CV accounted for 81/166 (48.8%) positive tests. Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) was positive in 39/335 (11.6%) who were tested: 26/103 (25.2%) and 13/232 (5.6%) among infants 0 - 6 months and over 6 months, respectively. HSV was not tested in 61.0% and 53% of the over-all cohort and those 0 - 6 months, respectively. Supplemental testing yielded 17 positive, including 5 HSV.

Conclusions

Viral testing in PALF occurs frequently but is often incomplete. Evidence for acute viral infection was found in 20.2% of those tested for viruses. HSV is an important viral cause for PALF in all age groups. The etiopathogenic role of CV and AV in PALF requires further investigation.

Keywords: hepatotropic viruses, herpes virus, Epstein Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, HHV-6

Introduction

Pediatric acute liver failure (PALF) is caused by multiple conditions categorized broadly as infectious, metabolic, immune mediated, drug related, and indeterminate.1 Among viral etiologies in the developing world, hepatitis A, B and E, are the most common cause of PALF resulting in mortality rates of 54% to 85%.2, 3 In the United States and Western Europe, hepatitis A, B and C are often suspected but seldom identified as the etiology for PALF.1 Yet, herpes simplex and enterovirus were found to be the cause of PALF in 16% of infants.4 While case reports of hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection among adults in the United States are noted5, HEV was not identified in a cohort of adults with acute liver failure.6 Reasons for these differences can include regional prevalence of the various viruses, immunization practices, age or genetic susceptibility7 as well as incomplete testing for specific viruses.8

The prodrome associated with pediatric acute liver failure (PALF) can include one or more non-specific symptoms such as fever, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, irritability, diarrhea, anorexia and listlessness. If present, these symptoms are often presumed to be “viral” in origin, even if a known viral cause is not identified. Hence, it is not surprising that reports of PALF identified “non-hepatitis A, non-hepatitis B, non-hepatitis C” hepatitis as a frequent cause of PALF.9 However, metabolic liver disease, drug induced liver injury, and immune mediated liver injury may also present with one or more “viral” symptoms. More recently, a diagnosis of “Indeterminate” PALF has been chosen to categorize those PALF participants in whom a specific diagnosis was not or could not be established.1, 8

Identification of a virus using acute serological markers, culture or histology in the setting of acute liver failure may not infer causality. For example, parvovirus B19 has been associated with PALF with or without aplastic anemia10, but parvovirus has been identified in human liver when other etiologies were present11. As the prevalence of parvovirus in liver tissue of individuals in the absence of liver disease is unknown, its presence may be circumstantial and not pathogenic.

The purpose of this study was to analyze and report results of testing for acute viral infection in a large cohort of children with PALF who were enrolled in the Pediatric Acute Liver Failure Study Group (PALFSG) registry.

Materials and Methods

Data included in this analysis were gathered from 22 pediatric sites: 19 centers in the United States, 1 in Canada and 2 in the United Kingdom. Definitions and study methodology have been previously described.1, 12 Participant enrollment began in December 1999 and the results reported here include participants enrolled by December 2012. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all of the institutions and the National Institutes of Health provided a Certificate of Confidentiality. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of the children in the study.

Patients less than 18 years of age were eligible for enrollment into the PALFSG registry if they met the entry criteria previously described.1 Patients from birth through 18 years of age were eligible for enrollment if they met the following entry criteria for the PALF study: (1) no known evidence of chronic liver disease, (2) evidence of acute liver injury, and (3) hepatic-based coagulopathy not corrected by vitamin K with the follow parameters: prothrombin time (PT) ≥ 15 seconds or international normalized ratio (INR) ≥ 1.5 in the presence of clinical hepatic encephalopathy (HE) or a PT ≥20 seconds or INR ≥ 2.0 regardless of the presence or absence of clinical HE. Following enrollment, demographic and clinical data were recorded daily for up to seven days. Diagnostic evaluation and medical management were under the direction of the attending physician at each participating institution, and were consistent with the standard of care at each site. A final diagnosis for the cause of PALF was assigned by the primary physician at each study site.1 For the purpose of this analysis, participants were grouped into three diagnostic classes using the final diagnosis determined by the primary physician at each study site: “Viral”, “Indeterminate” or “Other” (e.g., autoimmune, metabolic, Wilson). Children with liver failure due to acetaminophen (APAP) toxicity were excluded from this analysis.

A single daily serum sample was collected, generally with the first morning blood draw following enrollment, then daily for up to seven days, or until death, liver transplantation, or hospital discharge. The serum sample was divided into 250 μL or 500 μL aliquots, frozen at -80°C at the enrollment site and later batch-shipped to the research bio-repository for long-term storage. The frequency and volume of serum that could be collected for research purposes was dependent upon participant weight, hemoglobin, and the daily volume of blood required for diagnosis and management. Given these safety restrictions, research samples were not available for all PALF cohort participants every day.

Viral analyses

Prioritization and methods of viral testing for clinical purposes were determined by site specific standard of care. For purposes of analysis, an acute viral infection was defined by positive tests listed in Table 1. Data from 860 non-APAP etiology participants was examined for serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) against specific viruses, viral deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or ribonucleic acid (RNA) by polymerase chain reaction, viral antigen and/or viral culture. Recognizing the challenges associated with affirming an explicit cause and effect between evidence of viral illness and acute liver failure, a consensus of collaborating pediatric hepatologists and infectious disease specialists grouped identifiable viruses as being either a Causative Virus (CV) or Associated Virus (AV). A CV was considered likely to be the primary etiologic agent precipitating a PALF event while AVs were capable of causing PALF but, due to factors such as prevalence and pathogenesis, evidence of a recent or current infection with an AV made inference of causality less certain. Causative viruses (CV) included hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), herpes simplex virus (HSV) type unspecified, parvovirus (PV), adenovirus (AdV), and enterovirus (EV, infants 0 – 6 months only). Associated viruses (AV) included hepatitis C virus (HCV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein Barr virus (EBV), human herpes virus 6 (HHV6), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV). To be noted, HBV was considered to be a CV if HBV core IgM and/or HBV DNA were positive, but if only the HBsAg and/or HBeAg were positive and the HBV core IgM and/or HBV DNA were either negative or not done, then HBV was considered an AV.

Table 1. The corresponding tests used to determine causative viral (CV) causes or associated viral (AV) causes in PALF participants.

| Causative Viral (CV) Causes | Tests to determine viral causes |

|---|---|

| HAV | HAV IgM antibody |

| HBV | HBV core IgM antibody or HBV DNA |

| HSV | HSV IgM antibody, HSV DNA, HSV culture from blood, tracheal or nasopharyngeal aspirate, liver tissue, and/or cerebrospinal fluid |

| EV | EV RNA or EV IgM antibody (age 0 - 6 months old) |

| AdV | AdV DNA |

| PV | PV IgM antibody or PV DNA |

| Associated Viral (AV) Causes | |

| HBV | HBsAg or HBeAg |

| HCV | HCV RNA |

| CMV | CMV DNA, CMV IgM antibody or CMV culture from liver tissue and/or tracheal aspirate |

| EBV | EBV DNA in blood or bone marrow or EBV IgM antibody |

| HHV-6 | HHV-6 DNA from blood or liver |

| HIV | HIV IgM antibody |

Participants with a final diagnosis of “Viral”, “Indeterminate”, or” Other” diagnosis as determined by the site investigator were analyzed with respect to the number of viral tests that were ordered and the percentage of positive tests for each virus. Results were analyzed in groups of participants who were 0 - 6 months of age and >6 months of age since HSV13 and enterovirus14 were known to cause of PALF in very young infants but rarely thought to be so in older subjects.

Participants not previously tested for CV at the local site and with available serum in the PALF research bio-repository underwent supplemental testing for CV. Samples were identified and batch-shipped from the research bio-repository to the Mayo Medical Laboratories (Rochester, MN) and ViraCor Laboratories (Lee's Summit, MO) for supplemental viral testing. The Mayo Laboratories performed testing for hepatitis A IgM antibody, hepatitis B core IgM antibody, herpes IgM antibody, and parvovirus IgM antibody for participants from birth up to 18 years. ViraCor Laboratories performed enterovirus PCR and adenovirus PCR testing on available samples from participants less than 1 year.

Statistical Methods

Percentages are reported for categorical variables and medians and inter-quartile ranges are reported for continuous values. Pearson's chi-square test was used for categorical data to determine whether the association of the distribution of 21-day outcomes with diagnosis groups and viral testing groups was statistically significant and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for testing whether distributions of continuous variables differed across diagnosis groups. Exact tests were used to determine whether distributions of diagnosis and 21 day outcome were significantly different among participants with positive HSV. Results were considered significant if p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

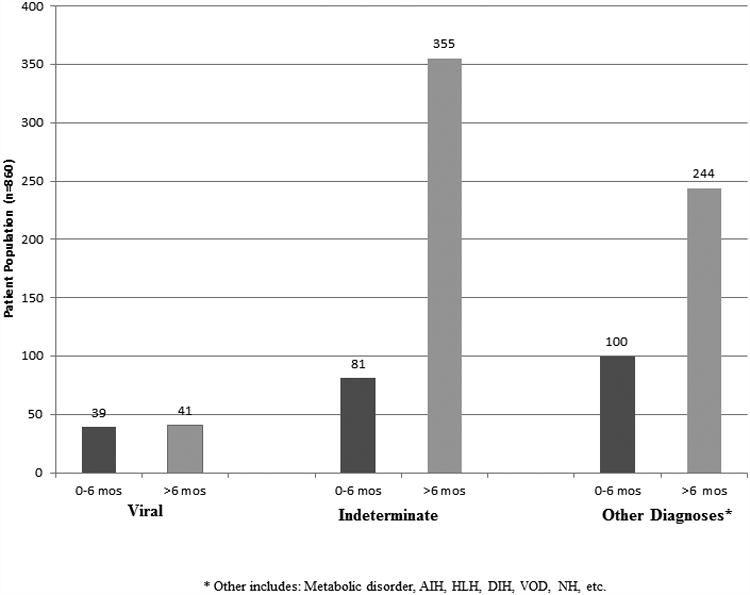

There were 860 participants in the PALF cohort study whose etiology was not APAP. The most frequent diagnostic categories were “Indeterminate” followed by “Other” (Figure 1.) Demographic, clinical and outcome data stratified by diagnosis are presented in Table 2. The 80 participants with a final diagnosis of “Viral” were younger than those with either an “Indeterminate” or “Other” diagnosis and differed with respect to 21 day outcome from those with an “Indeterminate” diagnosis, but did not differ significantly from those with an “Other” diagnosis.

Figure 1. Investigator Determined Final Diagnosis by Age.

Table 2. Demographic, clinical data and outcome by diagnosis group.

| Viral N=80 | Indeterminate N=436 | Other N=344 | p-valuea | p-valueb | p-valuec | p-valued | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Age at enrollment (years) | <0.0001& | <0.0001# | <0.0001# | NS# | |||

| N | 80 | 436 | 344 | ||||

| Median | 0.6 | 3.7 | 4.3 | ||||

| Range | 0.0-17.9 | 0.0-17.9 | 0.0-17.9 | ||||

| 0 – 6 months old | 39 (48.8%) | 81 (18.6%) | 100 (29.1%) | <0.0001$ | <0.0001$ | 0.0007$ | 0.0006$ |

| ➢ 6 months old | 41 (51.3%) | 355 (81.4%) | 244 (70.9%) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Total bilirubin at enrollment (mg/dL) | <0.0001& | 0.0005# | NS# | <0.0001# | |||

| N | 65 | 385 | 288 | ||||

| Median | 9.1 | 14.2 | 8.8 | ||||

| Range | 0.3-39.0 | 0.2-43.1 | 0.4-63.4 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| INR at enrollment | 0.0003& | NS# | 0.016# | 0.0001# | |||

| N | 70 | 381 | 296 | ||||

| Median | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.5 | ||||

| Range | 1.3-13.7 | 1.0-63.9 | 1.0-13.0 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| ALT at enrollment (IU/L) | <0.0001& | NS# | 0.0003# | <0.0001# | |||

| N | 67 | 375 | 289 | ||||

| Median | 909 | 1732 | 582 | ||||

| Range | 103-8681 | 18-18524 | 7-13372 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| 21-day outcome | <0.0001$ | <0.0001$ | NS$ | <0.0001$ | |||

| Death without LT | 22 (27.5%) | 42 (9.6%) | 53 (15.4%) | ||||

| LT | 13 (16.3%) | 194 (44.5%) | 77 (22.4%) | ||||

| Survival without LT | 45 (56.3%) | 200 (45.9%) | 214 (62.2%) | ||||

NS=not significant after Bonferroni correction (p-value >0.0167)

p-value across the three diagnosis groups.

p-value for the comparison between “Viral” and “Indeterminate”

p-value for the comparison between “Viral” and “Other”

p-value for the comparison between “Indeterminate” and “Other”

From Pearson's chi-square test of association

From Kruskal-Wallis test

From Mann-Whitney test

Viral testing patterns for CV are presented in Table 3. HAV was the most frequently tested 610/860 (70.9%) with 15/610 (2.5%) testing positive. Each of the other CVs was tested in no more than 40% of participants. Testing for Enterovirus was positive in 22.6% of those who were tested, but only 14.1% of children 0 - 6 months of age were tested for Enterovirus.

Table 3. Test results for causative viruses (CV).

| Total (N=860) n (%) | 0 - 6 months (N=220) n (%) | >6 months (N=640) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| HAV | |||

| Not tested | 250 | 111 | 139 |

| Positive | 15 (2.5) | 3 (2.8) | 12 (2.4) |

| Source | 3 IgM | 12 IgM | |

|

| |||

| HBV | |||

| Not tested | 578 | 173 | 405 |

| Positive | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.3) |

| Source | 2 DNA | ||

| 2 unknown source | |||

| 1 IgM alone | |||

|

| |||

| HSV | |||

| Not tested | 525 | 117 | 408 |

| Positive | 39 (11.6) | 26 (25.2) | 13 (5.6) |

| Source | 20 DNA | 1 DNA | |

| 13 blood | 1 blood | ||

| 1 Nasopharyngeal | 10 IgM alone | ||

| 4 Cerebrospinal fluid | 2 Culture aloen | ||

| 2 unknown | |||

| 2 IgM and Culture | |||

| 4 Culture alone | |||

|

| |||

| Adenovirus | |||

| Not tested | 661 | 175 | 485 |

| Positive | 8 (4.0) | 1 (2.2) | 7 (4.6) |

| Source | 1 DNA | 7 DNA | |

| 1 blood | 6 blood | ||

| 1 unknown | |||

|

| |||

| Parvovirus | |||

| Not tested | 600 | 177 | 423 |

| Positive | 12 (4.6) | 1 (2.3) | 11 (5.1) |

| Source | 1 IgM | 8 DNA | |

| 6 blood | |||

| 2 unknown | |||

| 3 IgM alone | |||

|

| |||

| Enterovirus* | |||

| Not tested | 189 | ||

| Positive | 7 (22.6) | ||

| Source | 7 DNA | ||

| 5 blood | |||

| 2 unknown | |||

Note: Enterovirus was only examined among the participants 0 - 6 months

HSV, a potentially treatable condition, was tested in 335/860 (38.9%) with 39/335 (11.6%) testing positive for HSV. Among participants 0 – 6 months of age who were tested for HSV, 25.2% were positive. Interestingly, among children over 6 months of age, 5.6% tested for HSV were positive compared to 2.4% of those tested for HAV. All 26 participants 0 – 6 months old who were HSV positive had a final diagnosis of HSV determined by PALF investigators, while a final diagnoses of HSV was given in only 2/13 older subjects who tested positive for HSV (ages 2 and 14 years.) (p <0.0001 for final diagnosis by age groups from exact chi-square test.) Other diagnoses and ages for the older participants with a positive test for HSV included 6 “Indeterminate” (3,3,4, 14, 14, and 14 years), and one participant each with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (7 years), Wilson disease (17 years), autoimmune hepatitis (9 years), drug induced hepatitis (17 years), or shock/ischemia (13 years.) The 21 day outcomes for infants 0 - 6 months with a positive test for HSV vs those >6 months were: died without LT (61.5% vs 7.7%); LT (3.9 vs 53.9%) and alive without LT (34.6 vs 38.5%) (p = 0.0003 for 21 day outcome diagnosis by age group from exact chi-square test.)

Viral testing patterns for AV are presented in Table 4. The most commonly tested AVs were HBV 663/860 (77.1), CMV 642/860 (74.7 %), EBV 563/860 (65.5 %), and HIV 443/860 (51.5%). The three most frequently identified AVs relative to the diagnostic tests performed were HHV6 24/168 (14.3 %), EBV 44/563 (7.8 %), and CMV 32/642 (5.0%).

Table 4. Distribution of test results for associated viruses.

| Total n=860 | 0 – 6 months n=220 | ➢ 6 months n=640 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

|

| |||

| HCV | |||

| Not tested | 768 | 211 | 557 |

| Positive | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Source | 1 RNA | ||

| 1 unknown | |||

|

| |||

| CMV | |||

| Not tested | 218 | 73 | 145 |

| Positive | 32 (5.0) | 9 (6.1) | 23 (4.7) |

| Source | 6 DNA | 11 DNA alone | |

| 3 blood | 4 blood | ||

| 3 unknown | 1 tracheal aspirate | ||

| 3 IgM alone | 6 unknown | ||

| 12 IgM alone | |||

|

| |||

| EBV | |||

| Not tested | 297 | 120 | 177 |

| Positive | 44 (7.8) | 4 (4.0) | 40 (8.6) |

| Source | 1 DNA | 25 DNA | |

| 1 unknown | 11 blood | ||

| 3 IgM | 1 bone marrow | ||

| 13 unknown | |||

| 15 IgM | |||

|

| |||

| HHV-6 | |||

| Not tested | 692 | 193 | 499 |

| Positive | 24 (14.3) | 1 (3.7) | 23 (16.3) |

| Source | 1 DNA | 23 DNA | |

| 1 unknown | 13 blood | ||

| 3 liver tissue | |||

| 7 unknown | |||

|

| |||

| HIV | |||

| Not tested | 417 | 143 | 274 |

| Positive | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.8) |

| Source | 3 IgM | ||

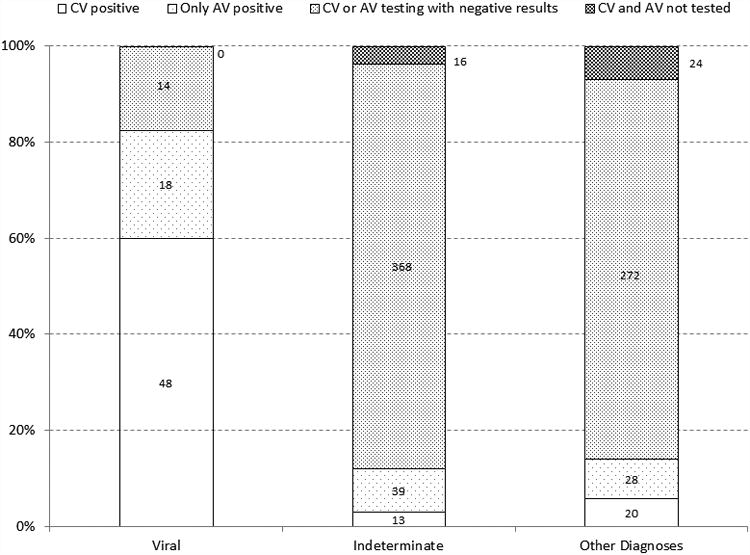

Figure 2 provides summary results of positive tests for CV and AV within diagnostic categories. Among participants with at least one CV or AV tested, a positive test was identified in 166/820 (20.2%). A CV was identified in 81/762 (10.6%) of those for whom at least one test for a CV was performed while an AV was identified in 99/795 (12.5%) of participants for whom at least one test for an AV was performed. There were 737 participants with test results for at least one CV and at least one AV of whom 14 (1.9%) tested positive for both CV and AV. Only 40 of the 860 participants had no viral testing for CV or AV performed. Among 80 participants with a final PALF diagnosis of “Viral”, 66 (82.5%) had a positive viral test, while 14 had a final diagnosis of “Viral” without a supportive diagnostic test in the PALF data set. Of 166 positive viral tests for CV and AV, 100 (60.4%) were distributed among participants with a final PALF diagnosis of either “Indeterminate” or “Other”. A positive viral test was identified in 52/420 (12.4%) with an “Indeterminate” diagnosis and 48/320 (15.0%) with “Other” known diagnoses.

Figure 2. Positive Results for CV and AV within Diagnostic Categories.

Among the 81 participants with a positive CV result, 13 were “Indeterminate” and 20 had an etiology “Other” than “Viral” (Table S1). Among the 20 “Other” were 11 who had conditions known to be associated with, or triggered by, severe viral infection such as hemophagocytic syndrome (n=3), shock/ischemia (n=3), viral sepsis (n=1), autoimmune hepatitis (n=3), or intra-ventricular hemorrhage (n=1). Of the 85 with only an AV positive test result were 39 “Indeterminate” participants and 28 “Other” (Table S2).

A large percentage of children were not fully tested for CV's. The percentages of those not tested in the 0 – 6 months age category and > 6 months were as follows for each of the following: (HAV - 50.0% and 21.7%); HBV (78.6% and 63.3%); HSV (53.2% and 63.8%), adenovirus (79.5% and 75.8%), parvovirus (80.4% and 66.1%); and enterovirus (85.9%in the 0 – 6 months category. No testing for enterovirus was done in participants more than 6 months old. Supplemental testing for CVs (HAV, HBV, parvovirus, HSV, adenovirus and Enterovirus) was performed for subjects who were not tested for these viruses at the clinical center and for whom stored research biospecimens were available. A positive test result was noted in 17/881 (1.9%) supplemental tests performed for 359 participants. Positive tests included parvovirus (6/219, 2.7%), HSV (5/214, 2.4%), enterovirus (3/92, 3.3%), adenovirus (2/76, 2.6%) and HAV (1/45, 2.2%). There were no cases of HBV identified in 235 samples tested. Information on the testing done and the samples available is shown in Table S3.

Outcomes at 21 days following entry into the PALF study differed between those with a positive CV test, regardless of AV results, and those with only an AV positive result (Table 5). Of 22 who died and tested positive for CV, 17 (77.3%) were HSV positive. Eight of the 14 participants who died without testing for either AV or CV died within 3 days of entry into the PALF cohort so that the opportunity for testing was limited.

Table 5. 21 day outcome.

| CV positive (N=81) n (%) |

Only AV positive (N=85) n (%) |

CV or AV positive (N=166) n (%) |

Neither CV nor AV positive (N=654) n (%) |

Neither CV nor AV tested N=40 n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death without LT | 22 (27.2) | 10 (11.8) | 32 (19.3) | 71 (10.9) | 14 (35.0) |

| LT | 15 (18.5) | 36 (42.3) | 51 (30.7) | 232 (35.5) | 1 (2.5) |

| Survival without LT | 44 (54.3) | 39 (45.9) | 83 (50.0) | 351 (53.7) | 25 (62.5) |

P-value=0.005 for 21-day outcome of “CV positive” vs. “Only AV positive”

P-value <0.0001 for 21-day outcome of “CV or AV positive” vs. “Neither CV nor AV positive” vs. “Neither CV nor AV tested”

Discussion

We observed that diagnostic testing for CV and AV was incomplete in this extensive cohort of PALF patients. HSV was common in children 0 - 6 months of age with 25.2% of those tested for HSV being positive, but can occur in all age groups. A specific virus was identified in 20.2% of our cohort of non-APAP PALF participants, but the site investigator determined the final diagnosis to be “Viral” in only 9.3% of PALF cases. Positive tests for CVs and AVs were identified in patients with a final diagnosis of “Indeterminate” or “Other”. Despite the extent of incomplete testing for CV among PALF participants, less than 2% of samples sent to a core laboratory for supplemental viral testing were positive. These findings raise many critical issues related to establishing a viral cause for PALF, the role of CVs or AVs in the etiopathogenesis of PALF and the importance of identifying a potentially treatable virus.

Herpes simplex virus is an important cause of PALF. Among children 0 - 6 months of age who tested positive for HSV, over 60% died within 21 days of entering the PALF study. Our findings affirm that HSV-induced acute liver failure in neonates is frequently fatal.13, 15 Thus, all neonates presenting with ALF should be tested for HSV. Treatment with acyclovir should be initiated, even before results of diagnostic studies are known, and continued until HSV has been excluded as a diagnosis.15, 16 HSV should also be considered as a cause of PALF beyond the neonatal period as 13 children between 2 and 17 years of age tested positive for HSV in our cohort. HSV hepatitis commonly occurs in immunocompromised patients such as organ transplant recipients; however, approximately 25% of patients who develop HSV hepatitis are immune-competent.16 Due to its low incidence and variable clinical presentation in older patients, HSV is rarely considered as an etiologic agent in acute liver failure.8 Our findings confirm this observation as 63.8% of children > 6 months of age were never tested for HSV. HSV should be considered as an important, potentially treatable cause for PALF in older children and adolescents, as well as adults.17

AVs with the highest percentage of positive tests in our cohort were HHV-6 (14.3%), EBV (7.8%) and CMV (5.0%). However, positive tests may simply reflect a high prevalence of these viral infections, particularly given the rarity of PALF among children with these infections. As examples, EBV, HHV-6, and CMV are ubiquitous infections; expected seropositive rates in adults are: EBV 80-90%, CMV 50-60%, and HHV6 100%.18-20 These are generally acquired early in life with EBV infection usual before 3 years, CMV a common childhood infection during the pre-school years, and HHV6 peak acquisition at 6-9 months of age, so evidence of these viruses could be present at the time of presentation with ALF, but not necessarily the cause of the PALF episode. Among immune-competent children, only EBV has been consistently reported to be associated with severe liver disease, but the frequency of ALF secondary to EBV remains uncommon.21, 22 However we do recognize that our terminology of “Causative Viruses” and “Associated Viruses” is only our best effort to combine the expert opinions of our infectious disease consultants and our own clinical experience, may well be controversial and difficult to justify with certainty.

Immune dysregulation leading to inappropriate immune activation and systemic inflammatory response can be associated with at least some cases of acute liver failure.23-26 Thus, it is possible, that each of these herpes-type viruses is “uncovering” or initiating immune events among susceptible individuals that result in an overwhelming immune response with subsequent liver cell death and liver failure. Each of these viruses has been associated with severe disease in immunosuppressed patients and, PALF may reflect an overwhelming viral infection resulting from immune dysfunction.27 An alternative hypothesis would be that the cause of PALF is due an insult other than the identified virus which serves only a chance association.

As many PALF participants did not have viral testing, we utilized stored serum samples to maximize the diagnostic evaluation for CV in PALF participants. Surprisingly, we found only an additional 17 positive viral tests leading us to believe that undiagnosed CV disease does not account for the majority of indeterminate cases. A search for novel or unexpected viruses was carried out in the Adult ALF study, but it was unrevealing.28

Diagnostic tests for CV and AV were incomplete for many children. One explanation may be that diagnostic testing may have been performed at an outside institution prior to study entry and not included in the data set. However, diagnostic evaluation associated with PALF is challenging.8 Diagnostic studies may not be obtained due to death, liver transplantation, or clinical improvement prior to a complete evaluation. Diagnostic tests may be improperly prioritized, or postponed due to daily blood volume restrictions, particularly in small children. Even if ordered properly, problems with insufficient serum or plasma to perform the test, tube breakage, or errors in shipping and handling of the specimen can impact the diagnostic yield. Diagnostic viral studies may be required for liver transplant evaluation. However, while both HIV and HCV are required for liver transplant evaluation, 52% of participants were tested for HIV while only 10.7% (92/86) of participants had HCV testing documented. This discrepancy illustrates the fact that it is not clear what motivated investigators to perform or not perform testing for the viruses we analyzed.

Our study has a number of limitations. Age-specific diagnostic testing for viruses was not mandated by the study, but was prioritized by the management team at each site which leaves testing decisions subject to inter- and intra-site variability. Methodologies used for diagnostic viral tests varied among sites which may impact positive and negative test results. The decision by the site principal investigator to assign a final diagnosis as either “Indeterminate” or “Other” when a CV or AV test was positive may have been based upon the combination of clinical history, presenting symptoms, other laboratory parameters, and/or histologic findings that precluded a final diagnosis of “Viral” or the results of the viral testing were either unknown or not recognized. The study was performed in a region of the world where CVs are not endemic, thus limiting the generalizability of this study to all regions of the world.

Additional limitations include the methods used and interpretation of test results to establish a viral diagnosis. There are no published series comparing viral serology with nucleic acid testing in children with PALF. Use of anti-viral IgM as one of the methods to diagnose infection with HSV or other CV may be impacted by blood transfusion or plasmapheresis. In extra-hepatic infections, reports suggest that anti-viral IgM has a low sensitivity but higher specificity for the presence of a confirmed infection. For example, Mahfoud et al examined the utility of viral serology compared to PCR for enterovirus, adenovirus, parvovirus B19, CMV, HHV-6, and EBV from endo-myocardial biopsies in patients suspected of infectious myocarditis.29 The investigators found that only in 5/124 patients (4%) had serological evidence of infection with the same virus detected by biopsy. Bendig et al found that many patients with anti-HAV IgM were also found to have a false positive test for enterovirus IgM.30 False positive IgM antibodies for HSV and EBV are frequently found in patients with acute parvo B19 virus infection.31 And although a positive IgM anti-HBc is often used to diagnose acute HBV as a cause of ALF32, positive IgM anti-HBc can be positive in about 30% of patients with acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B33. Lewensohn-Fuchs et al have demonstrated the utility of PCR on dried blood spots for neonatal HSV suggesting that this approach might be more useful for the diagnosis of HSV in patients with PALF.34

We conclude that diagnostic viral testing in PALF is often incomplete. HSV should be incorporated into the initial diagnostic testing of all children without a known cause for PALF at presentation. As AVs may serve as the primary etiology of PALF or initiate an inflammatory cascade in PALF, testing for AVs should be considered in the diagnostic evaluation of PALF, but interpretation of positive results requires a broader clinical context. A positive test for a CV or AV does not preclude other diagnostic considerations. Methods and interpretation of diagnostic viral testing remain problematic and requires further analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Key individuals who have actively participated in the PALF studies include (by site): Current Sites, Principal Investigators and Coordinators – Robert H. Squires, MD, Benjamin L. Shneider, MD, Kathryn Bukauskas, RN, CCRC (Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania); Michael R. Narkewicz, MD, Michelle Hite, MA, CCRC (Children's Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado); Kathleen M. Loomes, MD, Elizabeth B. Rand, MD, David Piccoli, MD, Deborah Kawchak, MS, RD, Timothy Crisci, Clinical Research Coordinator (Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); Rene Romero, MD, Saul Karpen, MD, PhD, Liezl de la Cruz-Tracy, CCRC (Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia); Vicky Ng, MD, Kelsey Hunt, Clinical Research Coordinator (Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada); Girish C. Subbarao, MD, Ann Klipsch, RN (Indiana University Riley Hospital, Indianapolis, Indiana); Estella M. Alonso, MD, Lisa Sorenson, PhD, Susan Kelly, RN, BSN, Dhey Delute, RN, CCRC, Katie Neighbors, MPH, CCRC (Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois); Philip J. Rosenthal, MD, Shannon Fleck, Clinical Research Coordinator (University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California); Mike A. Leonis, MD, PhD, John Bucuvalas, MD, Tracie Horning, Clinical Research Coordinator (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio); Norberto Rodriguez Baez, MD, Shirley Montanye, RN, Clinical Research Coordinator, Margaret Cowie, Clinical Research Coordinator (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, Texas); Simon P. Horslen, MD, Karen Murray, MD, Melissa Young, Clinical Research Coordinator, Heather Vendettuoli, Clinical Research Coordinator (University of Washington, Seattle, Washington); David A. Rudnick, MD, PhD, Ross W. Shepherd, MD, Kathy Harris, Clinical Research Coordinator (Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri).

Previous Sites, Principal Investigators and Coordinators – Saul J. Karpen, MD, PhD, Alejandro De La Torre, Clinical Research Coordinator (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas); Dominic Dell Olio, MD, Deirdre Kelly, MD, Carla Lloyd, Clinical Research Coordinator (Birmingham Children's Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom); Steven J. Lobritto, MD, Sumerah Bakhsh, MPH, Clinical Research Coordinator (Columbia University, New York, New York); Maureen Jonas, MD, Scott A. Elifoson, MD, Roshan Raza, MBBS (Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts); Kathleen B. Schwarz, MD, Wikrom W. Karnsakul, MD, Mary Kay Alford, RN, MSN, CPNP (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland); Anil Dhawan, MD, Emer Fitzpatrick, MD (King's College Hospital, London, United Kingdom); Nanda N. Kerkar, MD, Brandy Haydel, CCRC, Sreevidya Narayanappa, Clinical Research Coordinator (Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York); M. James Lopez, MD, PhD, Victoria Shieck, RN, BSN (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan).

The authors are also grateful for support from the National Institutes of Health (Edward Doo, MD, Director Liver Disease Research Program, and Averell H. Sherker, MD, Scientific Advisor, Viral Hepatitis and Liver Diseases, DDDN-NIDDK) and for assistance from members of the Data Coordinating Center at the University of Pittsburgh (directed by Steven H. Belle, PhD, MScHyg).

Financial support: PALF Study group supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease U01 DK072146

Abbreviations

- AdV

adenovirus

- APAP

acetaminophen

- AV

associated viruses

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CV

causative viruses

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EBV

Epstein Barr Virus

- EV

enterovirus

- HAV

hepatitis A Virus

- HBc

hepatitis B core antibody

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- HEV

hepatitis E virus

- HHV-6

human herpes virus-6

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HSV

herpes simplex virus

- IgM

Immunoglobulin M

- INR

International Normalized Ratio

- PALF

pediatric acute liver failure

- PALFSG

PALF Study Group

- PT

prothrombin time

- PV

parvovirus

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

References

- 1.Squires RH, Jr, Shneider BL, Bucuvalas J, et al. Acute liver failure in children: the first 348 patients in the pediatric acute liver failure study group. J Pediatr. 2006;148:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arora NK, Nanda SK, Gulati S, et al. Acute viral hepatitis types E, A, and B singly and in combination in acute liver failure in children in north India. J Med Virol. 1996;48:215–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199603)48:3<215::AID-JMV1>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santos DC, Martinho JM, Pacheco-Moreira LF, et al. Fulminant hepatitis failure in adults and children from a Public Hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2009;13:323–9. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702009000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundaram SS, Alonso EM, Narkewicz MR, et al. Characterization and outcomes of young infants with acute liver failure. J Pediatr. 2011;159:813–818 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davern TJ, Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, et al. Acute hepatitis E infection accounts for some cases of suspected drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1665–72 e1. 9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee WM, Brown KE, Young NS, et al. Brief report: no evidence for parvovirus B19 or hepatitis E virus as a cause of acute liver failure. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1712–5. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-9061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HY, Eyheramonho MB, Pichavant M, et al. A polymorphism in TIM1 is associated with susceptibility to severe hepatitis A virus infection in humans. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1111–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI44182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narkewicz MR, Dell Olio D, Karpen SJ, et al. Pattern of diagnostic evaluation for the causes of pediatric acute liver failure: an opportunity for quality improvement. J Pediatr. 2009;155:801–806 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devictor D, Desplanques L, Debray D, Ozier Y, Dubousset AM, Valayer J, Houssin D, Bernard O, Huault Emergency liver transplantation for fulminant liver failure in infants and children. Hepatology. 1992;16:1156–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langnas AN, Markin RS, Cattral MS, et al. Parvovirus B19 as a possible causative agent of fulminant liver failure and associated aplastic anemia. Hepatology. 1995;22:1661–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong S, Young NS, Brown KE. Prevalence of parvovirus B19 in liver tissue: no association with fulminant hepatitis or hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1581–6. doi: 10.1086/374781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Squires RH, Dhawan A, Alonso E, et al. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine in pediatric patients with non-acetaminophen acute liver failure: A placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hepatology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hep.26001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verma A, Dhawan A, Zuckerman M, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection presenting as acute liver failure: prevalent role of herpes simplex virus type I. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:282–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000214156.58659.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Atchison RW, Walpusk J, et al. Echovirus hepatic failure in infancy: report of four cases with speculation on the pathogenesis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2001;4:454–60. doi: 10.1007/s10024001-0043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riediger C, Sauer P, Matevossian E, et al. Herpes simplex virus sepsis and acute liver failure. Clin Transplant. 2009;23(Suppl 21):37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navaneethan U, Lancaster E, Venkatesh PG, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis - it's high time we consider empiric treatment. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:93–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norvell JP, Blei AT, Jovanovic BD, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis: an analysis of the published literature and institutional cases. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1428–34. doi: 10.1002/lt.21250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demmler-Harrison GJ. Cytomegalovirus. In: Feigin RD, Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, editors. Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. pp. 2022–2043. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gleeson M, Pyne DB, Austin JP, et al. Epstein-Barr virus reactivation and upper-respiratory illness in elite swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:411–7. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grose C. Human Herpesviruses 6,7, and 8. In: Feigin RD, Cherry J, Kaplan SL, demmler-Harrison GJ, editors. Feigan and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 6th. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. pp. 2071–2076. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feranchak AP, Tyson RW, Narkewicz MR, et al. Fulminant Epstein-Barr viral hepatitis: orthotopic liver transplantation and review of the literature. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:469–76. doi: 10.1002/lt.500040612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordenstrom A, Hellerud C, Lindstedt S, et al. Acute liver failure in a child with Epstein-Barr virus infection and undiagnosed glycerol kinase deficiency, mimicking hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:98–101. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181615cf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azhar N, Ziraldo C, Barclay D, et al. Analysis of serum inflammatory mediators identifies unique dynamic networks associated with death and spontaneous survival in pediatric acute liver failure. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bucuvalas J, Filipovich L, Yazigi N, et al. Immunophenotype predicts outcome in pediatric acute liver failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:311–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31827a78b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rolando N, Wade J, Davalos M, et al. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2000;32:734–9. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yazigi N, Tial G, Filipovich A, et al. Natural Killer Dysfunction in Pediatric Acute Liver Failure. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:327A. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nourse JP, Jones K, Dua U, et al. Fulminant infectious mononucleosis and recurrent Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in an adolescent. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:e34–7. doi: 10.1086/650007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umemura T, Tanaka E, Ostapowicz G, et al. Investigation of SEN virus infection in patients with cryptogenic acute liver failure, hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia, or acute and chronic non-A-E hepatitis. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1545–52. doi: 10.1086/379216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahfoud F, Gartner B, Kindermann M, et al. Virus serology in patients with suspected myocarditis: utility or futility? Eur Heart J. 2011;32:897–903. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bendig JW, Molyneaux P. Sensitivity and specificity of mu-capture ELISA for detection of enterovirus IgM. J Virol Methods. 1996;59:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)01997-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berth M, Bosmans E. Acute parvovirus B19 infection frequently causes false-positive results in Epstein-Barr virus- and herpes simplex virus-specific immunoglobulin M determinations done on the Liaison platform. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:372–5. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00380-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wai CT, Fontana RJ, Polson J, et al. Clinical outcome and virological characteristics of hepatitis B-related acute liver failure in the United States. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:192–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodella A, Galli C, Terlenghi L, et al. Quantitative analysis of HBsAg, IgM anti-HBc and anti-HBc avidity in acute and chronic hepatitis B. J Clin Virol. 2006;37:206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewensohn-Fuchs I, Osterwall P, Forsgren M, et al. Detection of herpes simplex virus DNA in dried blood spots making a retrospective diagnosis possible. J Clin Virol. 2003;26:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.