Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether transfer of a primarily motor nerve (Femoral, F) to the anterior vesicle branch of the pelvic nerve (PN) allows more effective bladder reinnervation than a primarily sensory nerve (genitofemoral, GF).

Methods

Forty-one female mongrel hounds underwent bladder decentralization, decentralization and then bilateral nerve transfer (GFNT and FNT) or were sham/unoperated controls. Decentralization was achieved by bilateral transection of all sacral roots that induce bladder contractions upon electrical stimulation. The retrograde neuronal labeling dye fluorogold was injected into the bladder 3 weeks prior to euthanasia.

Results

Increased detrusor pressure after direct stimulation of the transferred nerve, lumbar spinal cord or spinal roots was observed in 12/17 GFNT dogs (mean detrusor pressure = 7.6±1.4 cmH2O) and in 9/10 FNT-V dogs (mean detrusor pressure = 11.7±3.1 cm H2O). The mean detrusor pressures after direct electrical stimulation of transferred femoral nerves were statistically significantly greater than after stimulation of the transferred genitofemoral nerves. Retrogradely labeled neurons from the bladder observed in upper lumbar cord segments after GFNT and FNT confirmed bladder reinnervation as did labeled axons at the nerve transfer site.

Conclusions

While transfer of either a mixed sensory and motor nerve (GFN) or a primarily motor nerve (FN) can reinnervate the bladder, using a primarily motor nerve provides greater return of nerve-evoked detrusor contraction. This surgical approach may be useful for patients with lower motor spinal cord injury to accomplish bladder emptying.

Keywords: Bladder reinnervation, spinal cord injury, nerve transfer, somatic nerve

Introduction

The lower urinary tract is controlled by a complex neural circuit between the brain, spinal cord, inferior mesenteric ganglia and peripheral pelvic plexus that coordinates urine storage and emptying.1,2 Severe spinal cord, sacral root or pelvic plexus injury can damage neuronal cell bodies or axons innervating the bladder. This can cause a lower motor neuron lesion leading to a neurogenic bladder with detrusor areflexia.3 Long-term consequences can be as severe as renal failure and recurrent urinary infections are common.4,5 Epidemiological studies suggest that regaining bladder continence in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) improves quality of life,3 aids reintegration into the community and helps prevent clinical complications.4 While morbidity from urinary tract related complications has been reduced by self-catheterization, Credé’s maneuver and pharmacological management,6 the quality of life would be markedly improved with restoration of urinary bladder function.3

We have shown in a canine model that bladder reinnervation is possible by nerve transfer to the anterior vesical branch of the PN after spinal root transection.7–10 We demonstrated reinnervation by nerve-evoked detrusor contractions and retrograde labeling techniques after sacral nerve transection and repair, transfer of coccygeal to sacral roots, and transfer of the genitofemoral to the anterior vesical branch of the pelvic nerve (PN). We now seek to test the hypothesis that transferring a nerve with more motor axons to the PN (i.e., branches of the femoral nerve) would more effectively reinnervate the detrusor muscle and restore nerve-evoked detrusor contractile function.

Materials and Methods

Studies were approved by the Temple University IACUC, compliant with NIH, USDA and AAALAC guidelines. Forty-one female mongrel hound dogs, 6 to 8 months old, 16.7 to 20 kg (Marshall BioResources, North Rose, NY) were divided into six groups: genitofemoral nerve transfer with vesicostomy (GFNT-V, n=12); GFNT without vesicostomy (GFNT-NV, n=5); femoral nerve transfer with vesicostomy (FNT-V, n=5); FNT without vesicostomy (FNT-NV, n=5); sham/unoperated controls (n=6 and 3, respectively); and decentralized controls (n=5).

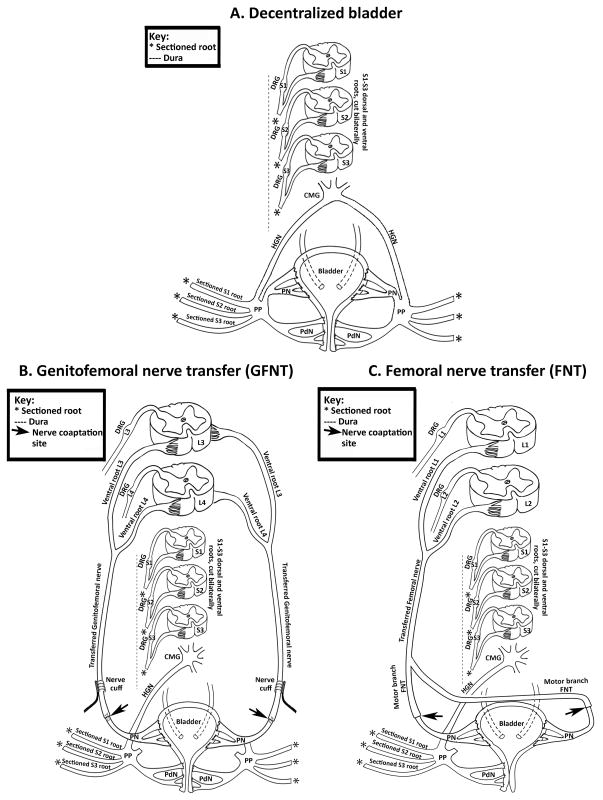

Nerve Transfer Surgeries

Surgical preparation and extradural bladder decentralization were as described (Fig. 1C).8–10 Seventeen dogs underwent GFNT to the vesicle branch of the PN (Fig. 1B),8, 9 of which 12 underwent abdominal vesicostomy (GFNT-V) and 5 did not (GFNT-NV) to determine whether vesicostomy induced bladder defunctionalization affected reinnervation. In animals without vesicostomies, bladder emptying was achieved by continuous catheterization during the first week postsurgery. Animals were checked for a full bladder twice/day for 2 months during which the Credé maneuver was used for bladder emptying, and then checked once/week thereafter. In the 12 GFNT-V dogs, radiofrequency (RF) micro-stimulators (Alfred Mann Foundation, Valencia, CA) interfaced with nerve cuff electrodes were placed bilaterally, around the transferred GFNs. Insufficient numbers of micro-stimulators were available for implantation in all animals. Only 2/5 GFNT-NV dogs received a nerve cuff, unilaterally, on the right. Ten dogs underwent left FNT to the bilateral vesicle branches of the PN (Fig. 1C) as described7, 11 without nerve cuff electrodes; 5 with (FNT-V) and 5 without vesicostomies (FNT-NV).

Figure 1.

Diagrams representing surgical methods used. A) Bilateral bladder decentralization. B) Genitofemoral nerve transfer (GFNT). C) Femoral nerve transfer (FNT). DRG= dorsal root ganglion; CMG= caudal mesenteric ganglia; HGN= hypogastric nerve; PP= pelvic plexus; PdN= pudendal nerve; L= lumbar.

Controls

Sham-operated controls underwent lumbosacral laminectomy, bladder nerve root identification via electrical stimulation and abdominal vesicostomy, but no root transection or nerve transfer. PN nerve cuff electrodes with micro-stimulators were placed bilaterally in one and unilaterally in another. Because no differences were found between sham and unoperated dogs, all were combined into one group (Sham/control). Five dogs were decentralized only and received abdominal vesicostomy (decentralized controls).

Functional Electrical stimulation (FES)

Implanted nerve cuff electrodes were activated as early as 4 to 5 weeks post-surgery. In the FNT animals, the transferred nerve was stimulated transcutaneously where the nerve was tunneled close to the skin. On the day of euthanasia, the implanted electrodes were activated, the FNT transferred nerves were activated transcutaneously and the spinal cord segments and roots activated by direct stimulation using mono- or bipolar electrodes.8, 9 Detrusor pressure was obtained with a Foley catheter passed into the vesicostomy or through the urethra in dogs without vesicostomy. Bladder capacity was determined with 3 successive filling cystometrograms using normal saline at 30 mL/minute (defining bladder capacity as the volume inducing a marked increase in the slope of the volume-pressure curve). The bladder was then emptied and filled to half of this measured bladder capacity (approximately 30 mL). Immediately prior to euthanasia, intraoperative electrical stimulation (15-V, 20-Hz, 1-msec square wave trains) of L1-L7 spinal cord segments, bilateral spinal roots, the PN, the transferred GFN and FN was used to evaluate return of nerve-evoked detrusor contractile function. The maximum detrusor pressure (MDP) is presented for each animal from 3–8 separate stimulations.

In vivo retrograde dye tracing and analysis

Fluorogold (FG) was injected into the urinary bladder of all animals, as described.8–10 Three weeks later bladders were examined post-euthanasia for the nerve coaptation site and diameters of GFN and PN were measured using calipers. The spinal column, roots and spinal nerves from T10 to coccygeal (CG) 1, and bladder were fixed en bloc by immersion in phosphate buffered 4% paraformaldehyde for 4–6 weeks at 4°C. Spinal cord sections were analyzed quantitatively for retrogradely labeled motor neuron cell bodies, as described.8–10

Statistical analysis

MDP per group was compared using one-way ANOVA. Two-way ANOVAs were used to evaluate the mean number of fluorogold-labeled neurons per section and per group. Bonferroni post-hoc method was used and p<0.05 was considered statistically different. Data is presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Nerve diameters

The mean diameters were similar across groups: GFN = 1.3 ± 0.07 mm (n=14), PN = 1.7 ± 0.08 mm (n=26), and transferred FN = 1.49 ± 0.03 mm (n=11).

FES during recovery

4/12 GFNT-V dogs with bilateral nerve cuffs showed increased detrusor pressure prior to euthanasia (Table 1, Dogs 5, 10, 11, 12 on days 44,168, 170 and 119 respectively). Unfortunately, a bacterial infection developed at 120 days in dog 10 and no increased detrusor pressure was obtained thereafter. GFNT-V animals 16 and 17 with a nerve cuffs only on the right side did not show any increase in detrusor pressure. All RF micro-stimulators explanted following euthanasia were electrically functional. All 10 FNT dogs showed minimal changes in gait or movement following recovery from surgery. Two FNT-V dogs (Dogs 19 and 21) showed increased detrusor pressure by transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the transferred nerve (Table 2, Dog 19 at day 215 and dog 21 at day 100). The two sham animals with PN implanted nerve cuffs showed increased detrusor pressure during RF micro-stimulation at 94 and 154 days with MDP=37.8 and 10.8 for dogs 34 and 35 respectively (data not shown).

Table 1.

Maximum detrusor pressure at euthanasia in dogs receiving bilateral genitofemoral nerve transfer to pelvic nerves, with and without abdominal vesicostomy (GFNT-V and GFNT-NV).

| Dog | Group | Return of function | Post-operative day | Maximum detrusor pressure (cmH2O)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulation of transferred nerve using implanted electrode | Direct stimulation of transferred nerve or cord | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Left | Right | Bilateral stim | Transferred nerve

|

Lumbar cord | ||||||||

| Left | Right | |||||||||||

| 1 | GFNT-V | Yes | 246 | -- | -- | -- | 3.7 | -- | NT | |||

| 2 | GFNT-V | No | 198 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | NT | |||

| 3 | GFNT-V | Yes | 195 | -- | -- | -- | 5.5 | 4.5 | NT | |||

| 4 | GFNT-V | Yes | 189 | -- | -- | -- | 3.6 | -- | NT | |||

| 5 | GFNT-V | Yes | 184 | 2.6 | 2.8 | -- | -- | -- | NT | |||

| 6 | GFNT-V | Yes | 324 | -- | 3 | 4 | -- | -- | -- | |||

| 7 | GFNT-V | No | 251 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | NT | |||

| 8 | GFNT-V | Yes | 251 | -- | 3 | 4 | -- | -- | NT | |||

| 9 | GFNT-V | No | 248 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | NT | |||

| 10 | GFNT-V | No | 265 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | NT | |||

| 11 | GFNT-V | Yes | 301 | 4 | 2 | 10 | -- | -- | 17 L3 | |||

| 12 | GFNT-V | Yes | 293 | -- | -- | 12 | -- | -- | 12 L3 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 13 | GFNT-NV | Yes | 237 | NA | NA | NA | 3.2 | -- | 3.6 L4 | |||

| 14 | GFNT-NV | Yes | 228 | NA | NA | NA | -- | -- | 16.8 L3 | |||

| 15 | GFNT-NV | Yes | 229 | NA | NA | NA | NT | NT | 14.3 L3 | |||

| 16 | GFNT-NV | No | 223 | NA | -- | NA | -- | -- | -- | |||

| 17 | GFNT-NV | Yes | 224 | NA | -- | NA | 3.9 | 2.2 | 10.6 L2 | |||

-- = no response during stimulation; NT= not tested NA= not applicable.

Table 2.

Maximum detrusor pressure at euthanasia in left femoral nerve branches transferred bilaterally to pelvic nerves, with and without abdominal vesicostomy (FNT-V and FNT-NV).

| Dog | Group | Return of function | Post-Operative Day | Maximum detrusor pressure (cm H2O)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transferred nerve (Bilateral stim) | Lumbar roots or spinal cord

|

||||||

| Spinal root

|

Lumbar Cord | ||||||

| Left | Right | ||||||

| 18 | FNT-V | Yes | 224 | -- | -- | 27.2 | 26.9 L6 |

| 19 | FNT-V | Yes | 224 | 11.3 | 29.1 | 14.3 | 33.8 L2 |

| 20 | FNT-V | Yes | 224 | -- | 7.1 | -- | 10.1 L3 |

| 21 | FNT-V | Yes | 224 | 7.1 | 9.7 | -- | 9 L3 |

| 22 | FNT-V | Yes | 224 | -- | 2.2 | 4 | 2.6 L2 |

|

| |||||||

| 23 | FNT-NV | Yes | 232 | -- | -- | 6 | 5.4 L4 |

| 24 | FNT-NV | Yes | 226 | -- | 8.3 | 6.8 | 9.7 L1 |

| 25 | FNT-NV | No | 225 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 26 | FNT-NV | Yes | 224 | -- | 6 | 4.7 | 20.9 L3 |

| 27 | FNT-NV | Yes | 224 | -- | 7.9 | 5.2 | 18.9 L1 |

-- = no response during stimulation.

FES at euthanasia (Tables 1–3; Fig. 2)

Table 3.

Maximum detrusor pressure at euthanasia in bladder decentralization only control dogs, sham control dogs, and un-operated control dogs.

| Dog | Group | Return of function | Post-Operative Day | Maximum detrusor pressure (cm H2O)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP/PN

|

Sacral cord | |||||

| Left | Right | |||||

| 28 | Decentralization | Yes | 203 | 5.7 | 2.9 | -- |

| 29 | Decentralization | Yes | 203 | 10.1 | 30.1 | -- |

| 30 | Decentralization | Yes | 95 | 3 | 7.1 | -- |

| 31 | Decentralization | Yes | 95 | 14.5 | 10 | 7.3 |

| 32 | Decentralization | Yes | 95 | 12.7 | 10.5 | -- |

|

| ||||||

| 33 | Sham | NA | 224 | 26.1 | 16.1 | NT |

| 34 | Sham | NA | 224 | 6.4 | 7.3 | NT |

| 35 | Sham | NA | 224 | 5.1 | -- | NT |

| 36 | Sham | NA | 126 | NT | NT | 41.9 |

| 37 | Sham | NA | 394 | NT | NT | 4.9 |

| 38 | Sham | NA | 394 | NT | NT | 10.3 |

| 39 | Un-operated | NA | NA | 21.1 | -- | NT |

| 40 | Un-operated | NA | NA | 1.0 | -- | NT |

| 41 | Un-operated | NA | NA | 14.8 | -- | NT |

-- = no response during stimulation, NA= = not applicable; NT= not tested.

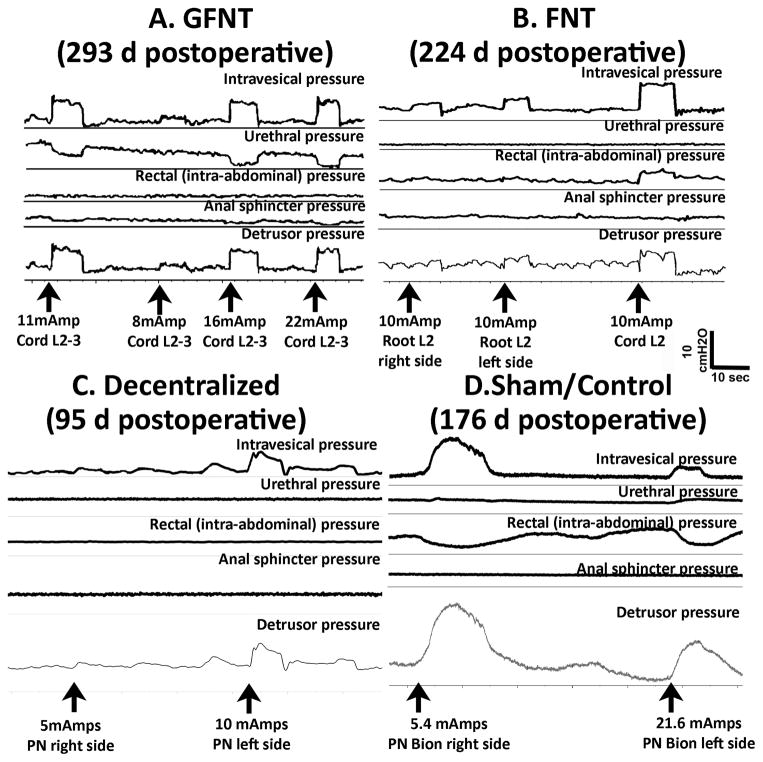

Figure 2.

Representative in vivo bladder and detrusor pressure recordings during electrical stimulation. A) GFNT Dog 12 during direct electrical stimulation of L2-3 cord segments, prior to euthanasia at 293 days post-surgery. B) FNT Dog 18 during direct electrical stimulation of L2 cord segment, prior to euthanasia at 224 days. C) Decentralized Dog 30 during direct electrical stimulation of PN, prior to euthanasia at 95 days. D) Sham/control Dog 34 during direct electrical stimulation of PN with implanted nerve cuff electrode interfaced with RF micro-stimulator prior to euthanasia at 251 days.

Representative traces show increased detrusor contraction in a GFNT and FNT following electrical stimulation of lumbar cord segment (GFNT, Fig. 2A) or lumbar roots (FNT, Fig. 2B). In decentralized dogs, sacral or lumbar cord segment or root stimulation did not increase detrusor pressure, although direct stimulation of the PNs did (Fig. 2C), similar to sham/unoperated controls (Fig. 2D).

Return of nerve-evoked detrusor contractile function was observed in 8/12 dogs with GFNT-V (see Table 1 for MDP). This was observed unilaterally in 4 dogs, bilaterally with stimulation of either the left or the right transferred nerves in 3 dogs, and with only with simultaneous bilateral activation of both implanted nerve cuffs in one dog. In Dogs 6 and 8, increased detrusor pressure was observed during activation of only the right micro-stimulator and with bilateral activation of both micro-stimulators. Although implanted electrodes at euthanasia failed to produce increased detrusor pressure in 7 dogs, this was observed with direct electrical stimulation of the transferred GFN in 3 of these, validating bladder reinnervation and electrode or lead failure. Due to concerns about possible damage to transferred nerves during stimulation, FES of lumbar spinal cord and roots was used for the remaining groups.

Nerve-evoked detrusor contractile function was observed in 4/5 GFNT-NV dogs (Table 1). This occurred unilaterally in one and bilaterally in another during FES of the L3-L4 spinal roots, and after FES of lumbar spinal cord segments in four. No increase in detrusor pressure was observed in Dog 16 that was found to have gauze sponges accidentally left in during surgery at the GFN coaptation site, with tissue fibrosis apparently interfering with bladder reinnervation.

Although only 2/5 FNT-V dogs showed increased detrusor pressure using transcutaneous stimulation, direct FES of lumbar roots or cord segments showed return of nerve-evoked detrusor contractile function in all 5. The FNT-NV surgery resulted in return of nerve-evoked detrusor contractile function in 4/5 dogs at euthanasia (Table 2). One FNT-NV animal (Dog 27) also had a gauze sponge left in during the nerve transfer, with apparently no effect on bladder reinnervation.

Complete bladder decentralization was confirmed at euthanasia after direct stimulation of sacral segments in 4/5 bladder decentralized dogs (Table 3). Dog 31 showed an MDP of 7.3 cmH2O after direct stimulation of sacral spinal cord segments, suggestive of regrowth of some sacral axons. Interestingly, bladder contractions were observed via direct stimulation of the pelvic plexus or PN in all five bladder decentralized dogs.

All nine sham/un-operated controls showed increased detrusor pressure, either after activation of the implanted nerve cuff or direct FES of the PN or sacral cord segments (Table 3). There was no statistical difference between shams and unoperated dogs so these are merged. There were no significant statistical differences between the GFNT-V and GFNT-NV subgroups (p=0.78), or FNT-V and FNT-NV subgroups (p=0.36) so these were also merged. One way ANOVA showed that the MDP after direct spinal cord stimulation was lowest in the decentralized bladder dogs (Fig. 4A). The MDP after direct FES stimulation transferred nerves in GFNT dogs was lower than in FNT dogs or after direct FES stimulation of the PP or PN in sham/unoperated or decentralized dogs (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Maximum detrusor pressure (MDP) after FES. A) MDP after spinal cord FES. *p<0.05, compared to sham/unoperated dogs. B) MDP after FES of pelvic nerve (PN) or pelvic plexus (PP) in the sham/unoperated and decentralized groups and FES of the transferred GFN or FN in the GFNT and FNT groups. ##: p<0.01, compared to FNT group; *&:p<0.05 compared to Sham/unoperated or decentralized groups.

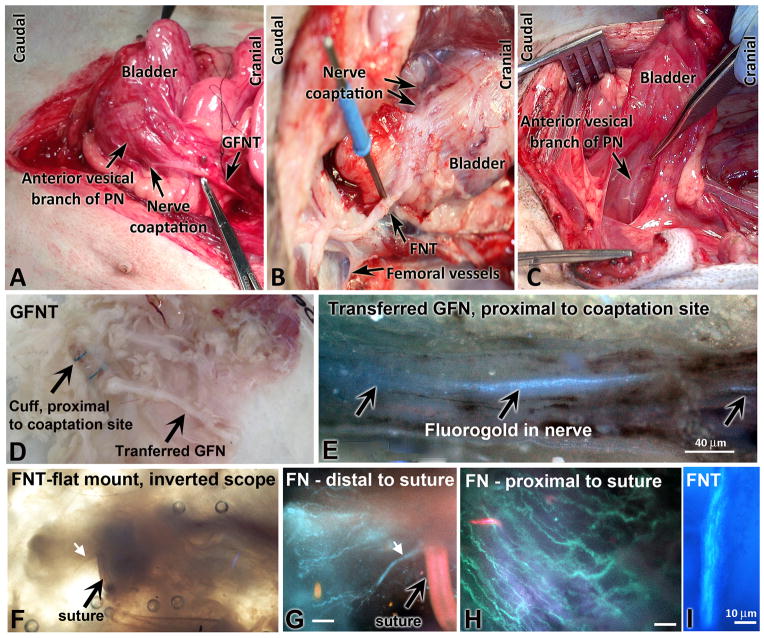

Axonal growth across coaptation site

Fluorogold labeled axonal processes from the detrusor muscle wall could be observed in the transferred GFN and FN proximal to the nerve cuff and coaptation suture sites (examples in Fig. 3 E,H–I). Figures 3F and G show axonal processes, fluorogold labeled in G, immediately distal to the coaptation suture site. Figure 3 E,H and I show labeled axons proximal to the suture site.

Figure 3.

Dissection and microscope images of transferred GFNs and FNs, after coaptation to PN. A) GFNT at euthanasia. B) FNT at euthanasia. C) Normal bladder innervation. D) Serosa-nerve preparation from a GFNT dog, in a petri dish. E) Fluorogold labeled axons in GFNT, proximal to coaptation site (spinal cord side). Combined bright field and fluorescence on an inverted scope. F) Inverted scope view of FNT specimen, and G) fluorogold labeled axons of same specimen, distal to suture site. White arrow indicates same axonal process. H) Fluorogold labeled axons in same FNT sample, proximal to suture site. I) Fluorogold labeled axons in another FNT, 2 cm proximal to coaptation. Scale bars in G–H = 10 micrometers.

Axonal growth from lumbar cord to bladder

The majority of labeled cord neurons in the sham/unoperated control group were located in the lateral zona intermedia and lamina VII of S1–3 ventral horns (Fig. 5E,J), primarily in S2 and S3 (Fig. 6A). Unexpectedly, a few labeled neurons were observed in L1–2 and L5–7 ventral horns, but very few to no labeled neurons in L3–4 ventral horns (Fig. 5A; 6A). In the decentralized control group, no labeled neurons were observed in S2-3 or L3-L4 ventral horns (Fig. 5B,F; 6B), although a few were present in L1-2, L5-7, and S1 segments (Fig. 6B). There was a significant loss of labeled neurons in S1-S3 ventral horns in decentralized controls (Fig. 6A, B). In GFNT+/−V groups, increased numbers of FG labeled neurons were observed in laminae VIII and IX of L3-4 ventral horns, compared to controls (Fig. 5C,I; 6C). The number of labeled cells was significantly decreased in S2-S3 ventral horns, compared to controls (Fig. 6C).

Figure 5.

Location of fluorogold (FG) labeled neurons in lamina VII–IX of lumbar (L) and sacral (S) ventral horns (VH) after dye injection into bladder. A,E) Sham control dog. B,F) Decentralized control dog. C,G) GFNT dog. D,H) FNT dog. I) Location of motor neurons innervating bladder in lumbar cord of GFN and FN dogs. J) Location of motor neurons innervating bladder of sham/unoperated control dogs.

Figure 6.

Mean number of retrogradely labeled cells (fluorogold) per mm2 in ventral horn spinal cord segments. A) Sham/unoperated controls. B) Decentralized controls. C) GFNT. D) FNT. CG = coccygeal, L= lumbar, S = sacral. * and **:p<0.05 and p<0.01, compared to decentralized dogs; # and ##:p<0.05 and p<0.01, compared to sham/unoperated dogs; &&: p<0.01, compared to FNT dogs.

In FNT+/−V groups, increased labeled neurons were observed in laminae VIII and IX of L1-4 ventral horns, compared to controls (Fig. 5D; 6D). Labeled cells were significantly decreased in S3 ventral horns, compared to controls (Fig. 5H; 6D), although a few labeled neurons were observed in S1-2 ventral horns. The FNT+/−V dogs contained higher numbers of fluorogold labeled cells in L1-2 ventral horns, than in the GFNT+/−V (Fig. 6D, C), in concordance with the femoral nerve arising primarily from upper lumbar segments, and the genitofemoral nerve from mid-lumbar segments.

Discussion

Although, the level of morbidity from urinary tract related complications has been significantly reduced in patients with urinary incontinence due to lower motor neuron lesion by self-catheterization, Credé’s maneuver and pharmacological management,6 embarrassment, depression and social isolation still decrease their quality of life.3 Improvement in neurogenic bladder management and restoration of function is very important for improving the quality of life of these patients, including conus medullaris and cauda equina injuries, pelvic trauma and children with spina bifida. During the last century, diverse studies have focused on the development of surgical techniques to reestablish and/or create new pathways between the bladder and the spinal cord. Restoring bladder contractile function by creating a new reflex pathway via transferring thoracic (T12), lumbar (L5), ventral or coccygeal roots and end-to-end coaptation with sacral (S2-3) VR has been performed in different species (rat, cat, dog, and human) with different degrees of successful return of nerve-evoked detrusor contractile function.10, 12–17 Similar techniques have mobilized intra-abdominal nerves such as hypogastric, obturator and genitofemoral nerves for end-to-end coaptation with PN,8, 9, 18, 19 indicating that rewiring of peripheral connections after lower motor neuron lesions may improve and even restore lower urinary tract contractile function. However, in most of the cases (e.g. L5 VR to S2-3 VR, and obturator to PN), the donor nerve function is destroyed. In the case of the obturator nerve (if the entire nerve was coapted), this would result in posture and gait problems due to the loss of adduction and medial rotation of the thigh since it is the main nerve to the adductor compartment of the thigh.

Our aim is to develop surgical techniques for functional reinnervation of the neurogenic bladder resulting from lower motor neuron lesions. We demonstrated that bladder reinnervation is possible either by sacral root repair, coccygeal root transfer to the sacral roots or GFNT to the anterior vesical branch of the PN,8–10 and now via transfer of left femoral nerve branches (FNT) to the anterior vesical branch of the PN. The evidence presented for this includes the following: 1) increased detrusor pressure as result of FES of the transferred nerves via electrical stimulation of an implanted nerve cuff on the transferred GFN, transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the transferred FN, direct electrical stimulation of transferred nerves, lumbar spinal roots or cord segments. 2) Anatomical continuity and nerve regeneration of the transferred nerves at the site of end-to-end coaptation with PN; and 3) increased lumbar cord cell bodies retrogradely labeled after injection of fluorogold into the bladder.

The unexpected lack of increased detrusor pressure with FES of the right PN in the unoperated control animals (dogs 39–41, table 3) is suggestive of unilaterality in detrusor muscle innervation in these normal dogs. Our findings in the decentralized dogs, that bladder pressure can be induced by pelvic nerve or pelvic plexus stimulation but not spinal cord or spinal root stimulation indicates that bladder ganglion cells persist in the pelvic plexus after spinal cord decentralization. This finding does not affect our results for transferred nerve stimulation because the transferred nerves were stimulated at a site proximal to the site of coaptation with the vesical branch of the pelvic nerve.

Originally, selection of the GF as the donor nerve in the dog model was based on ease of harvest, available length for transfer, and minimizing the complications associated with loss of the donor nerve function because this nerve innervates the cremaster muscle and skin covering the inguinal region and proximal medial thigh.20 Our inability to induce detrusor pressure with implanted nerve cuff electrodes in 7 of the 12 GFNT-V animals may be due to: 1) nerve cuff displacement (Table 1, dog 1: right side GFNT); 2) nerve compression injury due to the nerve cuff (dog 2); 3) aberrant formation of scar tissue inside and around of the nerve cuff (dogs 4, 7, 8, and 9); and 4) abscess formation (dog 10).

Detrusor pressures are higher during stimulation of the transferred FN branches than the transferred GF nerve (Fig 4B). Thus, using a primarily motor nerve as a donor produces greater functional response. For this dog model, we choose the branch of the femoral nerve that innervates the gracilis muscle because in dogs, this muscle is co-innervated by both femoral and obturator nerve branchs,20 minimizing the post-operative symptoms of loss of donor nerve functionality. Indeed these dogs showed minimal changes in gait or movement following recovery from surgery. Also, this branch matches the physical attributes of the recipient nerve including diameter, number and pattern of fascicles,21 attributes that can contribute to the success of reinnervation. In addition, our cadaver studies showed feasibility of the use of motor branches of the femoral nerve as a donor nerves for bladder and urethra reinnervation in humans.11, 22

The results from these studies, support the conclusion that bladder can be reinnervated either by GFNT or FNT. We also tested the hypothesis that bladder defunctionalization by creation of an abdominal vesicostomy might affect the degree of reinnervation and found no significant effect of vesicostomy on degree of bladder reinnervation. We did not evaluate histomorphological parameters of the transferred GFN and FN; however, our electrophysiological assays demonstrated that motor nerves (FN) functionally reinnervate the bladder better compared to the mixed nerve with primarily sensory axons (GFN) to a statistically significant extent (Fig. 4B). Limitations on this study include nerve cuff displacement and scar tissue formation around the site of nerve cuff placement. This scar formation may be a result of the nerve cuffs being placed on nerves near the bladder that can be expected to move with bladder filling and emptying.

In conclusion, return of nerve-evoked detrusor contractile function after spinal root injury is possible by bladder reinnervation via somatic nerve transfer with either motor or mixed nerves, but providing a greater number of motor axons provides a greater return of detrusor contraction. Additionally, the risk of post-operative symptoms of loss of function associated with the donor nerves and its functional distribution was minimal using GFNT or FNT in the dog. For future directions, regaining continence following spinal cord injury will also require reinnervation of external urethral sphincter while preventing detrusor sphincter dyssynergia.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the excellent histochemical assistance provided by Mamta Amin and Shreya Amin and the expertise of Professor Susan B. Fecho at Barton College for her assistance with the drawing in figure 1.

Source of Funding: This work was made possible by a grant (no. 1R01NS070267) from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NIH, to Drs. Barbe and Ruggieri.

References

- 1.De Groat W. Nervous control of the urinary bladder of the cat. Brain research. 1975;87:201. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshimura N, Groat WC. Neural control of the lower urinary tract. International journal of urology. 2007;4:111. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1997.tb00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorsher PT, McIntosh PM. Neurogenic bladder. Advances in urology. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/816274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samson G, Cardenas DD. Neurogenic bladder in spinal cord injury. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 2007;18:255. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manack A, Motsko SP, Haag-Molkenteller C, et al. Epidemiology and healthcare utilization of neurogenic bladder patients in a us claims database. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2011;30:395. doi: 10.1002/nau.21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns AS, Rivas DA, Ditunno JF. The management of neurogenic bladder and sexual dysfunction after spinal cord injury. Spine. 2001;26:S129. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112151-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruggieri MR, Braverman AS, Bernal RM, et al. Reinnervation of urethral and anal sphincters with femoral motor nerve to pudendal nerve transfer. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2011;30:1695. doi: 10.1002/nau.21171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruggieri MR, Braverman AS, D’Andrea L, et al. Functional reinnervation of the canine bladder after spinal root transection and genitofemoral nerve transfer at one and three months after denervation. Journal of neurotrauma. 2008;25:401. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruggieri MR, Braverman AS, D’Andrea L, et al. Functional reinnervation of the canine bladder after spinal root transection and immediate somatic nerve transfer. Journal of neurotrauma. 2008;25:214. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruggieri MR, Braverman AS, D’Andrea L, et al. Functional reinnervation of the canine bladder after spinal root transection and immediate end-on-end repair. Journal of neurotrauma. 2006;23:1125. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbe MF, Brown JM, Pontari MA, et al. Feasibility of a femoral nerve motor branch for transfer to the pudendal nerve for restoring continence: a cadaveric study: Laboratory investigation. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2011;15:526. doi: 10.3171/2011.6.SPINE11163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters KM, Girdler B, Turzewski C, et al. Outcomes of lumbar to sacral nerve rerouting for spina bifida. The Journal of urology. 2010;184:702. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao C, de Groat W, Godec C, et al. “ Skin-CNS-bladder” reflex pathway for micturition after spinal cord injury and its underlying mechanisms. The Journal of urology. 1999;162:936. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199909010-00094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao C, Godec C. A possible new reflex pathway for micturition after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1994;32:300. doi: 10.1038/sc.1994.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao CG. Reinnervation for neurogenic bladder: historic review and introduction of a somatic-autonomic reflex pathway procedure for patients with spinal cord injury or spina bifida. European urology. 2006;49:22. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao CG, Du MX, Dai C, et al. An artificial somatic-central nervous system-autonomic reflex pathway for controllable micturition after spinal cord injury: preliminary results in 15 patients.[see comment] Journal of Urology. 2003;170:1237. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000080710.32964.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao CG, Du MX, Li B, et al. An artificial somatic-autonomic reflex pathway procedure for bladder control in children with spina bifida. The Journal of urology. 2005;173:2112. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158072.31086.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimmel D. Urinary bladder function in rats following regeneration of direct and crossed nerve anastomoses. The Chicago Medical School quarterly. 1966;26:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trumble H. Experimental reinnervation of the paralyzed bladder. Med J Aust. 1935;1:118. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans HE, DeLahunta A. Guide to the dissection of the dog. 7. Saunders/Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolford LM, Stevao EL. Considerations in nerve repair. Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center) 2003;16:152. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2003.11927897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown JM, Barbe MF, Albo ME, et al. Anatomical feasibility of performing a nerve transfer from the femoral branch to bilateral pelvic nerves in a cadaver: a potential method to restore bladder function following proximal spinal cord injury: Laboratory investigation. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2013;18:598. doi: 10.3171/2013.2.SPINE12793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]