Abstract

The goal of this study was to evaluate three-dimensional (3-D) poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels as a culture system for studying corneal keratocytes. Bovine keratocytes were subcultured in DMEM/F-12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) through passage 5. Primary keratocytes (P0) and corneal fibroblasts from passages 1 (P1) and 3 (P3) were photoencapsulated at various cell concentrations in PEG hydrogels via brief exposure to light. Additional hydrogels contained adhesive YRGDS and nonadhesive YRDGS peptides. Hydrogel constructs were cultured in DMEM/F-12 with 10% FBS for 2 and 4 weeks. Cell viability was assessed by DNA quantification and vital staining. Biglycan, type I collagen, type III collagen, keratocan and lumican expression were determined by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. Deposition of type I collagen, type III collagen and keratan sulfate (KS)-containing matrix components was visualized using confocal microscopy. Keratocytes in a monolayer lost their stellate morphology and keratocan expression, displayed elongated cell bodies, and up-regulated biglycan, type I collagen and type III collagen characteristic of corneal fibroblasts. Encapsulated keratocytes remained viable for 4 weeks with spherical morphologies. Hydrogels supported production of KS, type I collagen and type III collagen matrix components. PEG-based hydrogels can support keratocyte viability and matrix production. 3-D hydrogel culture can stabilize but not restore the keratocyte phenotype. This novel application of PEG hydrogels has potential use in the study of corneal keratocytes in a 3-D environment.

Keywords: Keratocytes, Cornea, Scaffold, PEG, Tissue engineering

1. Introduction

Tissue engineering has recently emerged as a strategy to recreate corneal tissue. Several groups have successfully reproduced the general morphology and organization of the cornea with a fully stratified epithelium, continuous basement membrane, collagenous cellular stroma, and intact endothelium [1–6]. These in vitro reconstructions are able to support cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation and deposition of extracellular matrices important for use as replacement cornea tissue [4,5,7]. In addition, the constructs have been shown to be functional, maintaining transparency and responding to physical and chemical injuries in a manner similar to the native cornea [3,7]. While the majority of these research efforts have focused on the creation of a replacement cornea for therapeutic purposes, the goal of this study was to create a three-dimensional (3-D) in vitro model for studying corneal keratocyte populations in an environment that substantially mimics their in vivo milieu, which would be applicable for the study of stromal wound healing as well as the evaluation of keratocyte response to therapeutic agents.

Keratocytes are known to readily differentiate into corneal fibroblasts, losing their native morphology and phenotype, when cultured using traditional serum-based monolayer systems. 3-D culture systems have been applied to other cell types and have demonstrated retention of in vivo cell morphologies and phenotypes [8], as well as the restoration of native phenotypes that have been lost or altered in serial monolayer cultures [8,9]. Hydrogel culture systems can provide a 3-D environment, the cellular and spatial arrangement of which more closely resembles the in vivo tissue than do monolayer cultures. In addition, hydrogels have sufficient water content and porosity to allow the adequate diffusion of nutrients, growth factors and cellular by-products [10]. It is hypothesized that a 3-D hydrogel system can promote or restore the normal keratocyte phenotype, thus delaying or avoiding the fibroblastic transition that occurs in traditional monolayer cultures and frustrates the practical study of keratocytes in their native state.

The objective of this study was to assess the suitability of photopolymerizable poly(ethylene glycol)-based (PEG) hydrogels as a model system for supporting keratocyte populations and stabilizing their native phenotype. To that end, bovine keratocytes were photoencapsulated in both adhesive and non-adhesive (PEG) hydrogels and evaluated for cell viability, gene expression and protein deposition. In addition, the spatial features and porosity of the resulting hydrogel constructs were characterized.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell isolation and subculture

Bovine eyes were purchased from Research 87, Inc. (Marlborough, MA) within 36 h of slaughter. Keratocytes were isolated using a modified sequential, collagenase digestion [11]. Central corneas were removed and quartered with a scalpel, rinsed and collected on ice in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F-12 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) containing antibiotics. Physical scraping of superficial layers was avoided due to its potential induction of underlying keratocyte apoptosis [12]; histological analysis confirmed the removal of epithelial and endothelial layers with the first digestion. Cornea quarters were transferred to a 50 ml centrifuge tube containing 3.3 mg ml−1 collagenase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in DMEM/F-12, and incubated on a rotary shaker (150 rpm) at 37 °C for 30 min. After vortexing briefly, undigested tissue was separated using a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and transferred to a fresh collagenase solution for a second 60-min digestion. This process was repeated for a final 180-min digestion. Second and third digestion cells were collected through the 70 μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 1400 rpm for 10 min to pellet the keratocytes before the collagenase solution was removed. The cell number and viability from each digestion was determined using a hemacytometer and trypan blue exclusion. Primary cells were pooled from the second and third digestions, plated for subculture, encapsulated in hydrogels, or pelleted for RNA extraction.

Cells were plated in tissue culture flasks at a density of 5000 cells cm−2. Primary cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 containing 1% platelet-poor horse serum (Sigma) for 2 days, followed by DMEM/F-12 containing 10% FBS (Gibco), 10 U ml−1 penicillin and 10 μg ml−1 streptomycin (Gibco), 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin (Quality Biological, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) and 1.25 μg ml−1 amphotericin B (Gibco) for the remaining culture period. The medium was changed every 2–3 days. Upon confluency, the cells were trypsinized and subcultured, encapsulated or pelleted for RNA extraction. Monolayers were routinely subcultured through passage 5.

2.2. Hydrogel polymer preparation and characterization

Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) macromer (mol. wt. = 3400) was purchased from Nektar Therapeutics (Huntsville, AL). The adhesive peptide sequences RGD and YRGDS and the non-adhesive control peptides YRDGS (Department of Biological Chemistry, Johns Hopkins University) were covalently attached to PEGDA macromers by reacting raw peptide with an excess of acryl-poly(ethylene glycol)-N-hydroxysuccinimide (PEGNHS) (Nektar) in 50 mM Tris buffer and lyophilizing the reaction product overnight [13].

The following five polymers were used in encapsulations: 10% w/v PEGDA, 15% w/v PEGDA, 15% PEGDA + 2.5 mM RGD, 15% PEGDA + 2.5 mM YRGDS and 15% PEGDA + 2.5 mM YRDGS. Polymer concentrations for peptide-decorated hydrogels were increased to ensure a sufficient number of cross-linking sites and also allowed a comparison of hydrogel porosity. These and plain PEGDA polymer solutions were prepared by dissolving macromers in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing antibiotics.

Additional acellular gel constructs (n = 5) were prepared from 10% PEGDA, 15% PEGDA and 15% PEGDA + 2.5 mM YRGDS in PBS to characterize hydrogel properties. Wet and dry weights of gels were obtained to calculate porosity and average pore size via the Peppas–Merrill equation [14].

2.3. Cell encapsulation in hydrogels

Primary keratocytes were encapsulated in 10% PEGDA at 1.25, 3.75, 6.25, 12.5 and 17.5 million cells ml−1 to determine the optimal cell concentration for encapsulations. A concentration of 12.5 million cells ml−1 was chosen for all further encapsulations.

Pelleted primary keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts from P1 and P3 cultures were mixed with each polymer solution. Irgacure 2959 photoinitiator (Ciba Specialty Chemicals Co., Tarrytown, NY) was prepared in 70% ethanol and added to cell–polymer mixtures at a concentration of 0.05% w/v. The shallow cylindrical insets of glass-bottom culture dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA), served as molds to create thin lenticules 10 mm in diameter with a 1 mm thickness. Eighty microliters of cell–polymer solution were dispensed into the molds and polymerized via exposure to light (λ = 365 nm) at an intensity of 4 mW cm−2 for 6 min. After visual and tactile confirmation of polymerization, 2 ml of DMEM/F-12 with 10% FBS and antibiotics was added to each culture dish. The medium was changed every 2–3 days. Constructs were harvested for analysis after 2, 3 and 4 weeks in culture.

2.4. Optimization of cell concentration within hydrogel constructs

MTT staining was used to detect metabolically active cells within constructs after 2 weeks [15]. Constructs from each cell concentration were rinsed twice with PBS and transferred to clean six-well plates. Constructs were incubated in 2 ml of MTT solution (0.5 mg ml−1 MTT (Sigma) in DMEM with 2% FBS) for 4 h at 37 °C. After rinsing twice in PBS, constructs were observed under a Nikon Eclipse TE200 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) for the formation of purple formazan crystals.

2.5. Cell viability of encapsulated cells

Viability of primary and passaged (P3) keratocytes immediately following and 2 weeks after encapsulation in PEGDA and YRGDS hydrogels was determined using the Hoechst dye method [16]. Harvested constructs were lyophilized for 48 h, then digested in 1 ml papainase solution (Worthington Biomedical, Lakewood, NJ) at 60 °C for 16 h. DNA content was determined using Hoechst 33258 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) spectrafluorometry. Relative cell viability was determined by averaging readings (n = 3) for each group and taking the ratio of time zero and 2 week DNA content values.

2.6. Reverse transcriptase–polymerase gel reaction (RT–PCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted and purified from primary keratocytes and trypsinized corneal fibroblast subcultures using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Constructs were placed in Eppendorf tubes and homogenized with 1 ml TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen) using a tissue grinder and pestle (Kimble-Kontes, Vineland, NJ).

Centrifugation of the homogenized constructs with 200 μl of chloroform-pelleted cell and polymer debris left an RNA-laden supernatant which was further purified using the Mini Kit. Four constructs from each group were pooled to obtain sufficient amounts of RNA to perform RT-PCR. RNA concentrations were determined via absorption at 280 nm.

One microgram of RNA from each monolayer sample and 0.3 μg of RNA from each encapsulation group was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using random hexamers and the SuperScript™ First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). One microliter of cDNA from each sample was amplified over 35 cycles in a 50 μl reaction volume using the Ex-Taq polymerase premix (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Shiga, Japan). Annealing temperatures were adjusted for each of the following primers used: β-actin, 60.1 °C; biglycan, 60.1 °C; type I collagen 60.1 °C; type III collagen, 56.9 °C; keratocan 56.9 °C; and lumican, 55.0 °C. Forward and reverse primers used for each marker as well as PCR product size are summarized in Table 1. PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose (Invitrogen) gels in Tris-acetate–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (TAE) buffer (Roche Diagnostic, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) for 60 min at 100 V. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide (Invitrogen) to visualize product bands.

Table 1.

RT-PCR primer sequences

| Primer | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | PCR product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | ||

| Forward | TGGCACCACACCTTCTACAATGAGC | 396 |

| Reverse | GCACAGCTTCTCCTTAATGTCACGC | |

| Biglycan | ||

| Forward | GGTCGAAGTGGAGAGACAGC | 218 |

| Reverse | AGGTTCACCCACAGATCCAG | |

| Type I collagen | ||

| Forward | TGGGTTGATCCTAACCAAGG | 435 |

| Reverse | CCCAGTGTGTTTTGTGCAAC | |

| Type III collagen | ||

| Forward | TGCTGGACCTGCAGAATAATGAC | 326 |

| Reverse | AGGTCCAAAGCCGCTGTTCTC | |

| Keratocan | ||

| Forward | TTCAGCAATCTGGAGAACCTG | 953 |

| Reverse | GTTAGATTGTTGTGTTGTCATGC | |

| Lumican | ||

| Forward | CATTGACCTCCAGGTAATAG | 508 |

| Reverse | GCAATTGAAGAAGCTGC |

2.7. Confocal imaging of hydrogel constructs

Living cells were tracked throughout the 4 week culture period with CellTracker Orange™ (molecular probes), a fluorescent cytoplasmic stain. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, constructs were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in a 2.5 μM probe solution prepared in phenol red-free DMEM/F-12. Constructs were rinsed with medium for 30 min followed by three additional 5-min washes to remove remaining probe and reduce background fluorescence.

After labeling cells, constructs were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA; EMS, Fort Washington, PA) in serum and phenol red-free DMEM/F-12 for 10 min, followed by 3% PFA in PBS for 20 min. After rinsing with PBS, samples were quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl (Sigma) in PBS and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) in PBS for 30 min. Small sections from each construct were incubated with the following primary antibody solutions: 10 μg ml−1 rabbit anti-collagen type I (RDI, Flanders, NJ), 23 μg ml−1 mouse anti-collagen type III (Sigma) and 50 μg ml−1 mouse anti-keratan sulfate (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, IA) for 2 h. Note that the keratan sulfate (KS) antibody labels KS glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains found on keratocan, lumican and mimecan core proteins. Sections were next rinsed with 0.1% BSA in PBS, then incubated for 45 min with 4 μg ml−1 secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluors 488 and 647 (Molecular Probes) in 0.1% BSA in PBS. All sections were rinsed in 0.1% BSA in PBS and finally in PBS. Samples were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 Scanning Confocal Microscope in multi-track mode.

3. Results

3.1. Monolayer cultures

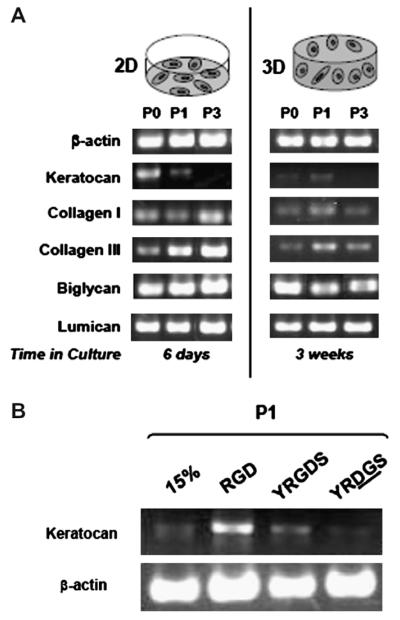

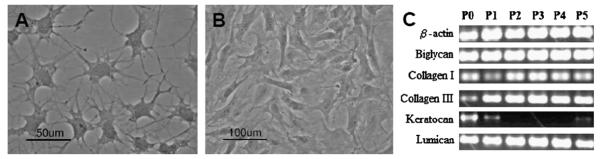

Primary keratocytes initially cultured in 1% platelet-poor horse serum (PPHS) maintained a highly dendritic morphology with numerous interconnecting processes (Fig. 1A) characteristic of cells in vivo [17,18] and in vitro [11,19,20] under serum-free conditions. After replacing low serum medium with DMEM/F-12 containing 10% FBS, cells gradually acquired a more fibroblastic appearance, with larger, elongated cell bodies and loss of intercellular processes (Fig. 1B) [11,19,20].

Fig. 1.

Morphology and gene expression of keratocytes cultured in monolayer. Phase contrast images of cell morphology under different serum conditions (A, B). Primary keratocytes cultured in 1% PPHS medium for 2 days (A) maintained dendritic morphologies with branched, interconnecting processes, similar to in vivo. In contrast, cells cultured in 10% FBS medium for 11 days (B) adopted elongated cell bodies characteristic of fibroblasts. RT-PCR analysis of stromal ECM markers expressed by primary (P0) and passaged (P1–P5) keratocytes cultured in monolayer with 10% FBS medium (C). Expression patterns demonstrated the loss of keratocyte phenotype that occurs under serum culture conditions. Keratocan was detected in primary and early passage (P1) cultures but was downregulated with continued serum-subculture (P2–P5). Concurrently, type I and III collagens and biglycan fibrotic markers were up-regulated with increasing passage number. Lumican transcript was present in all cultures. The housekeeping gene β-actin served as a control.

Phenotypic changes were observed by RT-PCR in serum-cultured cells that were consistent with the alterations in cell shape (Fig. 1C). Keratocan expression was lost after the first passage, but was faintly expressed by P5 cells. While keratocan expression diminished, biglycan remained highly expressed through P5, while type I collagen expression initially decreased from P0 to P1, but increased again at P2 and remained consistent through P5. Expression of type III collagen increased from P0 to P1 and was maintained at high levels through P5. Lumican expression remained constant through all passages.

3.2. Hydrogel cultures

3.2.1. Hydrogel properties

Hydrogel porosity and average pore size is summarized in Table 2. All hydrogel groups were highly water-swollen, displaying porosities of 89.9, 87.4 and 89.3% in 10% PEDGA, 15% PEGDA and YRGDS gels, respectively. Calculated pore size values ranged from 34.3 Å in 15% PEGDA gels to 41.6 Å in 10% PEGDA and YRGDS gels. Decreased porosity and pore size were observed in 15% PEGDA gels due to the increased cross-linking density afforded by increased polymer concentration. In YRGDS gels, the effect of increased polymer concentration and cross-linking density was balanced by incorporation of peptide pendants, yielding similar properties to 10% PEGDA gels.

Table 2.

Properties of hydrogels

| Hydrogel composition | Porosity (%) | Pore size (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| 10% PEGDA | 89.9 ± 0.2 | 41.5 ± 0.8 |

| 15% PEGDA | 87.4 ± 0.4 | 34.3 ± 1.7 |

| 15% PEGDA + 2.5 mM YRGDS | 89.3 ± 0.2 | 41.6 ± 0.5 |

3.2.2. Cell concentration

MTT staining was used to determine optimal cell concentration for photoencapsulation (Fig. 2A–E). After a 2-week culture period, keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts were metabolically active at all concentrations. More intense staining was observed at higher cell concentrations (Fig. 2D); therefore a concentration of 12.5 million cells ml−1 was chosen for all further encapsulations. This value falls in the range of reported in vivo keratocyte densities [21].

Fig. 2.

Cell viability, metabolic activity and morphology. MTT staining of metabolically active encapsulated cells (A–E). Keratocytes were encapsulated in 10% PEGDA hydrogels at concentrations of 1.25 (A), 3.75 (B), 6.25 (C), 12.5 (D) and 17.5 (E) million cells ml−1. A larger proportion of cells were stained at higher encapsulation densities, thus 12.5 million cells ml−1 (D) was selected as the optimum cell density. Cell clustering also enhanced MTT staining. Confocal microscopy of encapsulated cell viability and morphology (F–J). CellTracker™ labeling showed a high number of viable P1 keratocytes 24 h (F) after encapsulation in 10% PEGDA hydrogels. Cell number declined after 2 weeks in culture (G) but remained stable after 1 month (H). Encapsulated cells maintained spherical morphologies within the hydrogel construct (F–J). Ratio of 2-week to 0 time cell numbers for 2-week hydrogel culture, comparing cell passage number and hydrogel composition (K). Averaged values are relative to the initial number of cells determined immediately after encapsulation (ie. 100%). Primary keratocyte viability after 2 weeks in culture was 57.5% of the initial value, independent of polymer composition. Passage 3 cell number decreased by 24% in 10% PEGDA hydrogels but increased by 10% in YRGDS-modified constructs. Scale bar (F–J) is 50 μm. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

3.2.3. Cell viability

After qualitative determination of optimal encapsulation density, quantitative DNA analysis was used to determine the effect of cell passage number and polymer composition on cell viability (Fig. 2K). After 2 weeks in hydrogel culture, primary keratocyte numbers decreased to 57.5% of their initial value, independent of polymer composition. In passage three cultures, cell viability decreased by 24% in 10% PEGDA hydrogels but increased by 10% in YRGDS-modified constructs.

3.2.4. RT-PCR analysis

The gene expression profile of encapsulated keratocytes (3-D) is compared to that of similar passage monolayer cultures (2-D) in Fig. 3. Similar levels of the keratan sulphate proteoglyan, lumican were observed in both 2-D and 3-D cultures. In 2-D cultures, expression of biglycan, a dermatan sulphate proteoglycan, was increased slightly from P0 to P1, but remained consistent through P3. In contrast, for 3-D cultures, biglycan levels decreased slightly from P0 to P1, but remained the same through to P3. Collagen III levels steadily increased with each subsequent passage in 2-D cultures, while in 3-D hydrogels, expression increased from P0 to P1 and decreased again in P3 hydrogels. At each passage, collagen III expression was lower in 3-D hyrdogels compared to 2-D cultures. In 2-D cultures, expression of collagen I decreased from P0 to P1 and increased from P1 to P3. In general, 3-D hydrogels expressed lower amounts of collagen I, with an increase observed from P0 to P1 and a decrease noted from P1 to P3. The keratoctye-specific marker keratocan was expressed weakly by encapsulated primary cells and more strongly in P1 cells, but undetected in P3 constructs (Fig. 3A). Hydrogels could not restore keratocan in cells that lost expression of this marker prior to encapsulation, as seen in P3 constructs (Fig. 3A). Hydrogels modified with adhesive peptides enhanced keratocan expression in P1 constructs compared to unmodified and non-adhesive control hydrogels (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

RT-PCR analysis of keratocyte gene expression in monolayer and hydrogel cultures. RT-PCR comparison of transcripts expressed by cells cultured in monolayer or 15% PEGDA hydrogels with 10% FBS (A). Keratocan expression by P1 cells was maintained for 6 days in monolayer cultures compared to 3 weeks in hydrogel constructs. Hydrogel culture prolonged keratocan expression in P1 cells, but could not restore expression inP3 cultures that did not express the marker prior to encapsulation. Fibroblast markers biglycan, collagen I and collagen III were up-regulated with passage in monolayer cultures, but down-regulated with passage for keratocytes encapsulated in hydrogels. β-Actin served as a control. RT-PCR analysis of keratocan transcript expressed by encapsulated cells in non-adhesive vs. adhesive scaffolds (B). After 2 weeks in culture in 10% FBS, P1 keratocytes encapsulated in adhesive hydrogels (RGD and YRGDS) expressed higher levels of keratocan (normalized to β-actin control) than cells encapsulated in unmodified (15%) or non-adhesive-peptide (YRDGS) hydrogels.

3.2.5. Confocal imaging

CellTracker™ labeling showed a large number of viable P1 cells residing in 10% gels 24 h after encapsulation (Fig. 2F). Consistent with viability data, cell number had declined by 2 weeks, after which it remained stable for 1 month (Fig. 2G and H). Cells in all groups displayed spherical morphologies within constructs, lacking cell processes and intercellular connections.

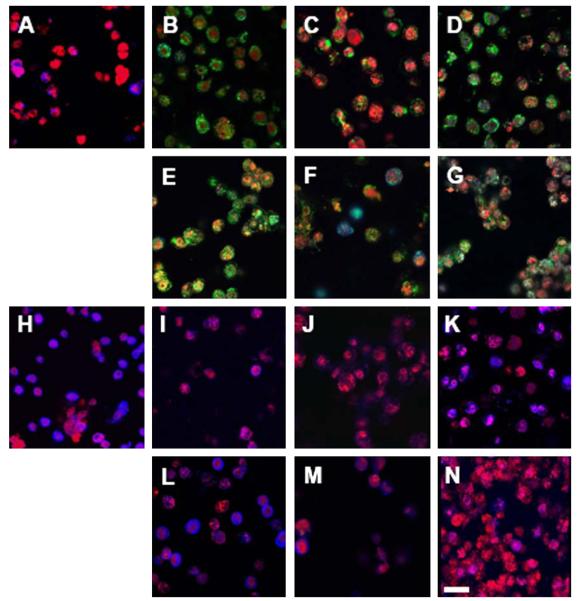

Encapsulated cells secreted type I collagen, type III collagen and keratan sulfate matrix components in the pericellular region, with deposition varying between cell populations (Fig. 4). After 2 weeks, primary keratocytes secreted more KS (Fig. 4H) but less collagen (Fig. 4A) than passaged cells. P1 and P3 cells produced little keratan sulfate after 2 weeks of culture; however, greater amounts of KS were accumulated after 1 month in culture (Fig. 4K). Adhesive hydrogels also enhanced KS production in P1 and P3 cells (Fig. 4L and M) at 2 weeks compared to unmodified hydrogels (Fig. 4I and J). P1 cells were surrounded by significant quantities of type I collagen (Fig. 4B and E), which was maintained over the one month evaluated (Fig. 4D and G). Higher levels of type III collagen production were observed in P3 samples (Fig. 4C and F), compared to P1 (Fig. 4B and E). In addition, for P1 cultures, more collagen III secretion was noted at 4 weeks (Fig. 4D and G) than at 2 weeks (Fig. 4B and E).

Fig. 4.

Confocal imaging of extracellular matrix components secreted by encapsulated keratocytes (red). Images A–G illustrate type I collagen (green) and type III collagen (blue) secreted by P0 (A), P1 (B, D, E, G) and P3 (C, F) cells encapsulated in 10% PEGDA for 2 (A–C) and 4 weeks (D), and in YRGDS hydrogels for 2 (E, F) and 4 weeks (G). Type I collagen was secreted in large amounts by encapsulated P1 cells (B) and to a lesser extent by P3 cells (C), but was absent from primary cultures (A). Small amounts of type III collagen were deposited in the pericellular region of P0 (A) and P3 (C) but not P1 (B) cells. Type III collagen showed accumulation with prolonged culture (D, G). Adhesive hydrogels enhanced total collagen production at all time points (E–G). Images H–N illustrate keratan sulfate (blue) secreted by P0 (H), P1 (I, K, L, N) and P3 (J, M) cells encapsulated in 10% PEGDA hydrogels for two (H–J) and 4 weeks (K), and in YRGDS hydrogels for two (L, M) and 4 weeks (N). Primary cells (H) encapsulated in 10% gels secreted high amounts of KS compared to trace amounts produced by passaged cells (I, J) after 2 weeks, although KS accumulated in P1 cultures after 1 month in culture. Cells encapsulated in adhesive constructs showed increased KS sulfate secretion compared to their counterparts in unmodified gels (L, M). Scale bar is 50 μm.

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to develop a 3-D in vitro stromal model to aid in the study of keratocytes in an environment similar to their native milieu. Such a model could be used to inform tissue engineering strategies and may be applied to the assessment of cell behavior during stromal wound healing and upon delivery of agents that may affect keratocytes in 3-D.

Cells have been shown to behave more similarly to their in vivo counterparts when cultured in 3-D environments rather than 2-D substrates of equivalent composition, indicating a spatial contribution to cell behavior. Williams and colleagues [10] found that goat mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in PEG hydrogels expressed increased amounts of extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules aggrecan and type II collagen compared to the same cells cultured in monolayer. Similarly, Benya et al. [9] observed that, while rabbit articular chondrocytes cultured in serial monolayer lose their differentiated phenotype, these dedifferentiated cells regain their differentiated phenotype when cultured in 3-D agarose gels. Other studies [22,23] have shown that differences in cell morphology, adhesion formation and subsequent adhesion-mediated signaling can govern cell survival, growth and gene regulation.

Hydrogels have been explored as materials for ophthalmic devices based on their optical properties and permeability [24,25]. PEG hydrogels demonstrate proven biocompatibility, transparency, and physiological water contents that allow adequate nutrient and waste transport [26,27]. Characterization of PEG-based hydrogels in this study demonstrated such properties, with high water content enabling diffusion of dissolved oxygen and sufficient pore sizes allowing the diffusion of high molecular weight serum components as well as smaller growth factors and metabolites. PEG macromers are nontoxic and can be photopolymerized to rapidly and mildly encapsulate cells [15]. In addition, PEG can be functionally modified to introduce desirable properties, such as degradability and adhesivity [13,28,29], and to direct cell behavior and tissue development. The above-mentioned properties make PEG hydrogels attractive candidates for modeling the corneal stroma.

This study demonstrates the ability of PEG-based hydrogels to support viable keratocyte populations, stabilize their phenotype and encourage the secretion of stromal extracellular matrix. The loss of keratocyte phenotype and fibroblastic transition that occurs during serum culture and in vivo wound healing has been well documented [11,19,20] and is supported by the monolayer data presented here. The keratocyte hallmarks, dendritic morphology, keratocan expression and KS production, are rapidly lost, reduced or altered in serum culture. Fibroblastic cells, in contrast, adopt elongated cell bodies and secrete biglycan and type III collagen, matrix components that are absent from healthy stroma but present in opaque scar tissues [20,30,31]. In hydrogel constructs, RT-PCR and confocal imaging indicated the production of normal stromal matrix components, particularly when primary and P1 cells are encapsulated. Keratocan expression and KS production are both present in early passage cultures, whereas type III collagen is more pronounced at the protein level when serum-subcultured P3 cells are encapsulated. Hydrogels, therefore, help to maintain, but cannot restore, keratocyte phenotype. This is in agreement with the recent findings of Espana [32], who noted that amniotic membrane could preserve keratocyte morphology and phenotype but could not reverse the phenotype in fibroblastic cells.

Confocal imaging of the hydrogel constructs provides a 3-D perspective on cell shape and distribution of ECM components. The spherical morphology of encapsulated cells and pericellular deposition of ECM seen in hydrogel constructs differs from what is found in vivo. In the natural stroma, collagen is highly aligned and regularly spaced in stacked lamellae to permit light transmission. Charged KS chains on keratocan, lumican and mimecan core proteins regulate fibril spacing and stromal hydration, helping to maintain stromal shape and refractive power. Keratocytes lie flattened between lamellae with small cell bodies and branched interconnecting processes, features that reduce light reflection and allow intercellular communication, respectively. The morphological and organization discrepancies between natural stroma and our stromal constructs may be due to the limited pore size and structure of the hydrogel. Degradable linkages can be incorporated into PEG hydrogels. Such degradable scaffolds may support extension of cellular processes between cells and the diffusion of matrix components throughout the construct [33]. Additionally, the introduction of spatial patterns or cues into the hydrogel may direct cell behavior and more appropriate ECM deposition. Cintron et al. demonstrated the ability of fibroblasts injected into the vitreous humor to align their cell bodies and secrete matrix along the needle injection track [34]. Stromal fibroblasts have also been reported to orient themselves parallel to aligned collagen fiber substrates and secrete aligned collagen matrices perpendicular to their orientation, similar to what is seen in vivo [35].

PEG can also be modified to promote desired biological activity and cell–matrix interactions. In this study, adhesive RGD peptides were used to encourage cell spreading and interconnections throughout the non-adhesive PEG scaffold. RGD-mediated events can also influence cell survival, proliferation and matrix production [13,17,29,36,37]. In encapsulated P3 cultures, adhesive constructs supported cell viability while a 24% decline in cell number was observed in unmodified hydrogels after 2 weeks, emphasizing the influence of adhesion on cell survival. It should be noted that while the DNA quantification assay used in this study enables calculation of total DNA, this method does not allow for an estimate of live vs. dead cells within the encapsulated matrix. It is therefore our assumption that changes in DNA concentration are as a result of cells losing or retaining viability. While similar trends were not observed for primary cultures, the enzymatic isolation process may render these cells more sensitive to survival conditions. In adhesive hydrogel constructs, enhanced keratocan expression and KS production were observed. The exact downstream consequences of RGD-associated binding are complex and difficult to predict, as this sequence is found on numerous matrix proteins and interacts with half of all integrin receptors [29]. It is known, however, that myofibroblasts present during wound healing require RGD-associated binding to fibronectin for the cytoskeletal reorganization that occurs when keratocyte phenotype is lost [11,38]. Randomly distributed RGD peptides on adhesive constructs may compete with fibronectin binding sites or interrupt integrin clustering, thereby reducing the phenotypic transition to fibroblasts or myofibroblasts in these constructs. Other peptides that may be incorporated into hydrogels to enhance adhesivity include fibronectin adhesion promoting peptide (FAP), which has the sequence WQPPRARI, which, when tethered to hydrogels, has been found to enhance adhesion, spreading and migration of corneal epithelial cells. FAP binds the carboxy-terminal heparin binding domain of fibronectin, and as such may activate alternative signaling pathways to RGD [39,40].

Characterization of hydrogel properties demonstrated pore structures sufficient for the diffusion of high-molecular-weight serum components. Thus the ability of hydrogels to stabilize the keratocyte phenotype is not due to isolation from serum components. Previous studies in the chondrocyte system have demonstrated cell proliferation and response to growth factors by cells encapsulated in PEG hydrogels, thus reiterating the sufficient porosity and diffusion properties of hydrogels [10]. Comparable hydrogel properties in 10% and peptide-modified gels constructs indicate that the overall improvement in matrix deposition in YRGDS groups was attributable to the incorporation of the peptide and not merely to changes in physical properties of the hydrogel.

This initial study demonstrates the potential applicability of hydrogels to in vitro stromal modeling. Our results have shown that 3-D culture in non-adhesive hydrogels has some benefits over 2-D culture, including diminished gene expression of collagen III and somewhat diminished gene expression of biglycan in higher passages. While it is difficult to make a definitive conclusion based on the gene expression of keratocan in 2-D vs. 3-D non-adhesive hydrogels, a convincing up-regulation of keratocan expression was observed for adhesive hydrogels compared to 2-D cultures and non-adhesive hydrogels. Enhanced secretion of collagen type 1 was noted for P1 cells cultured for 2 weeks in adhesive gels vs. their non-adhesive counterparts; however, this effect was lost by 4 weeks. Also, this enhanced collagen type 1 expression did not extend to P3 cultures, where, instead, an increase in the secretion of collagen type III (normally associated with scar tissue) was noted in adhesive vs. non-adhesive constructs. The notion that RGD-modified hydrogels may help maintain keratocyte character of the encapsulated cells is further supported by the observation of enhanced secretion of keratan sulphate by P1 cells at 2 weeks in these modified gels compared to non-adhesive gels. This correlates well with the observed increase in keratocan gene expression of P1 cells in RGD-modified gels vs. plain hydrogels. As noted for collagen type 1 staining, the effect of enhanced keratan sulphate secretion with RGD-modified gels did not extend to 4 weeks or P3 encapsulated cells. This study shows that RGD modified hydrogels may be useful as a tool for in vitro stromal modeling and as such warrant further study. Furthermore, increased understanding of cell–matrix interactions will allow improved design of hydrogels to better promote normal keratocyte behavior and accurate reconstruction of stromal architecture.

Acknowledgements

Supported by an Alcon Research Institute Award (Dr. Schein); the Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; and the Department of Education, Universities, and Investigation, the Basque Government, Spain.

References

- [1].Aquavella JV, Qian Y, McCormick GJ, Palakuru JR. Keratopros-thesis: current techniques. Cornea. 2006;25:656–62. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000214226.36485.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Germain L, Auger FA, Grandbois E, et al. Reconstructed human cornea produced in vitro by tissue engineering. Pathobiology. 1999;67:140–7. doi: 10.1159/000028064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Griffith M, Osborne R, Munger R, et al. Functional human corneal equivalents constructed from cell lines. Science. 1999;286:2169–72. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Orwin EJ, Hubel A. In vitro culture characteristics of corneal epithelial, endothelial, and keratocyte cells in a native collagen matrix. Tissue Eng. 2000;6:307–19. doi: 10.1089/107632700418038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kruse FE, Rohrschneider K, Volcker HE. Multilayer amniotic membrane transplantation for reconstruction of deep corneal ulcers. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1504–10. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90444-X. [discussion 1511] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zieske JD. Extracellular matrix and wound healing. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12:237–41. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Doillon CJ, Watsky MA, Hakim M, et al. A collagen-based scaffold for a tissue engineered human cornea: physical and physiological properties. Int J Artif Organs. 2003;26:764–73. doi: 10.1177/039139880302600810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hauselmann HJ, Aydelotte MB, Schumacher BL, Kuettner KE, Gitelis SH, Thonar EJ. Synthesis and turnover of proteoglycans by human and bovine adult articular chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads. Matrix. 1992;12:116–29. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Benya PD, Shaffer JD. Dedifferentiated chondrocytes reexpress the differentiated collagen phenotype when cultured in agarose gels. Cell. 1982;30:215–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim TK, Sharma B, Williams CG, et al. Experimental model for cartilage tissue engineering to regenerate the zonal organization of articular cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:653–64. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(03)00120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Beales MP, Funderburgh JL, Jester JV, Hassell JR. Proteoglycan synthesis by bovine keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts: maintenance of the keratocyte phenotype in culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1658–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wilson SE, He YG, Weng J, et al. Epithelial injury induces keratocyte apoptosis: hypothesized role for the interleukin-1 system in the modulation of corneal tissue organization and wound healing. Exp Eye Res. 1996;62:325–7. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Aiken-O’Neill P, Mannis MJ. Summary of corneal transplant activity Eye Bank Association of America. Cornea. 2002;21:1–3. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Peppas NA, Merrill EW. Development of semicrystalline poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels for biomedical applications. J Biomed Mater Res. 1977;11:423–34. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820110309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Elisseeff J, McIntosh W, Anseth K, Riley S, Ragan P, Langer R. Photoencapsulation of chondrocytes in poly(ethylene oxide)-based semi-interpenetrating networks. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;51:164–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200008)51:2<164::aid-jbm4>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim YJ, Sah RL, Doong JY, Grodzinsky AJ. Fluorometric assay of DNA in cartilage explants using Hoechst 33258. Anal Biochem. 1988;174:168–76. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Poole CA, Brookes NH, Clover GM. Confocal imaging of the human keratocyte network using the vital dye 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;31:147–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2003.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hahnel C, Somodi S, Weiss DG, Guthoff RF. The keratocyte network of human cornea: a three-dimensional study using confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Cornea. 2000;19:185–93. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Berryhill BL, Kader R, Kane B, Birk DE, Feng J, Hassell JR. Partial restoration of the keratocyte phenotype to bovine keratocytes made fibroblastic by serum. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3416–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Du Y, Chen J, Funderburgh JL, Zhu X, Li L. Functional reconstruction of rabbit corneal epithelium by human limbal cells cultured on amniotic membrane. Mol Vis. 2003;9:635–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Berlau J, Becker HH, Stave J, Oriwol C, Guthoff RF. Depth and age-dependent distribution of keratocytes in healthy human corneas: a study using scanning-slit confocal microscopy in vivo. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:611–6. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(01)01227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell–matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yamada KM, Pankov R, Cukierman E. Dimensions and dynamics in integrin function. Brazilian J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:959–66. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000800001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chirila TV. An overview of the development of artificial corneas with porous skirts and the use of PHEMA for such an application. Biomaterials. 2001;22:3311–7. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hicks CR, Fitton JH, Chirila TV, Crawford GJ, Constable IJ. Keratoprostheses: advancing toward a true artificial cornea. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;42:175–89. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Carnahan MA, Middleton C, Kim J, Kim T, Grinstaff MW. Hybrid dendritic–linear polyester–ethers for in situ photopolymerization. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:5291–3. doi: 10.1021/ja025576y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Burdick JA, Anseth KS. Photoencapsulation of osteoblasts in injectable RGD-modified PEG hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4315–23. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hern DL, Hubbell JA. Incorporation of adhesion peptides into nonadhesive hydrogels useful for tissue resurfacing. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;39:266–76. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199802)39:2<266::aid-jbm14>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hersel U, Dahmen C, Kessler H. RGD modified polymers: biomaterials for stimulated cell adhesion and beyond. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4385–415. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Funderburgh JL, Funderburgh ML, Mann MM, Corpuz L, Roth MR. Proteoglycan expression during transforming growth factor beta-induced keratocyte–myofibroblast transdifferentiation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44173–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107596200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tanihara H, Inatani M, Koga T, Yano T, Kimura A. Proteoglycans in the eye. Cornea. 2002;21:S62–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000263121.45898.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Espana EM, Grueterich M, Ti SE, Tseng SC. Phenotypic study of a case receiving a keratolimbal allograft and amniotic membrane for total limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:481–6. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bryant SJ, Anseth KS. Controlling the spatial distribution of ECM components in degradable PEG hydrogels for tissue engineering cartilage. J Biomed Mater Res. 2003;64A:70–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Komai-Hori Y, Kublin CL, Zhan Q, Cintron C. Transplanted corneal stromal cells in vitreous reproduce extracellular matrix of healing corneal stroma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:637–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vrana E, Builles N, Hindie M, Damour O, Aydinli A, Hasirci V. Contact guidance enhances the quality of a tissue engineered corneal stroma. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007 doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shu X, Ghosh K, Liu Y, et al. Attachment and spreading of fibroblasts on an RGD peptide-modified injectable hyaluronan hydrogel. J Biomed Mater Res. 2004;68A:365–75. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mann BK, Tsai AT, Scott-Burden T, West JL. Modification of surfaces with cell adhesion peptides alters extracellular matrix deposition. Biomaterials. 1999;20:2281–6. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Jester JV, Ho-Chang J. Modulation of cultured corneal keratocyte phenotype by growth factors/cytokines control in vitro contractility and extracellular matrix contraction. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:581–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jacob JT, Rochefort JR, Bi J, Gebhardt BM. Corneal epithelial cell growth over tethered-protein/peptide surface-modified hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;72:198–205. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mooradian DL, McCarthy JB, Skubitz AP, Cameron JD, Furcht LT. Characterization of FN-C/H-V, a novel synthetic peptide from fibronectin that promotes rabbit corneal epithelial cell adhesion, spreading, and motility. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:153–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]