Abstract

Neuronal dysfunction and degeneration are ultimately responsible for the neurocognitive impairment and dementia manifest in neuroAIDS. Despite overt neuronal pathology, HIV-1 does not directly infect neurons; rather, neuronal dysfunction or death is largely an indirect consequence of disrupted glial function and the cellular and viral toxins released by infected glia. A role for glia in HIV-1 neuropathogenesis is revealed in experimental and clinical studies examining substance abuse-HIV-1 interactions. Current evidence suggests that glia are direct targets of substance abuse and that glia contribute markedly to the accelerated neurodegeneration seen with substance abuse in HIV-1 infected individuals. Moreover, maladaptive neuroplastic responses to chronic drug abuse might create a latent susceptibility to CNS disorders such as HIV-1. In this review, we consider astroglial and microglial interactions and dysfunction in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection and examine how drug actions in glia contribute to neuroAIDS.

Keywords: Opiates, Cocaine, Methamphetamine, Alcohol, HIV encephalopathy, Neuroimmunology, AIDS

Introduction

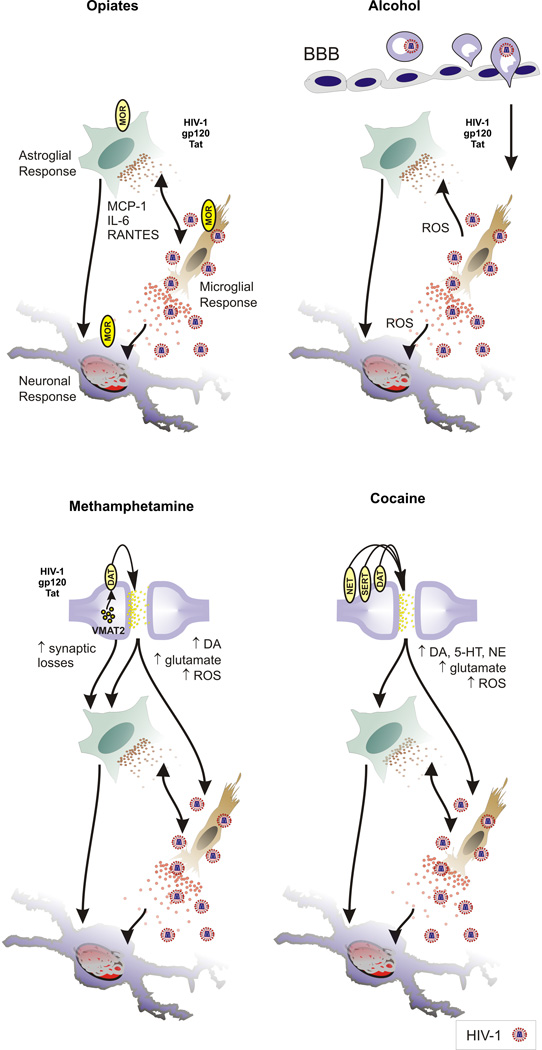

Neuronal dysfunction and degeneration are ultimately responsible for the neurocognitive impairment and dementia manifest in neuroAIDS. Neurodegeneration can accompany HIV-1 encephalopathy and HIV-associated dementia (HAD) (Navia et al. 1986; see Gray et al. 1991; Grimm et al. 1998; Sa et al. 2004; Roy et al. 2006). Despite overt neuronal pathology, HIV-1 does not directly infect neurons; rather, neuronal dysfunction or death is largely an indirect consequence of disrupted glial function and the cellular and viral toxins released by infected glia. The effects of HIV-1 on neurodegeneration have been extensively reviewed (Nath 1999; Mattson et al. 2005), as have the effects of substance abuse on neurons in HIV-1 infected individuals (Shapshak et al. 1996; Tyor and Middaugh 1999; Nath et al. 2000; Nath et al. 2002; Hauser et al. 2006b). The contributions of HIV-1-exposed microglia and astroglia to neurodegeneration in HIVE are well established (Gendelman et al. 1997; Nath 1999; Kaul and Lipton 1999; Kaul et al. 2001; Garden et al. 2002; Persidsky and Gendelman 2003; Hauser et al. 2005; Deshpande et al. 2005). Recently, the role of glia in HIV-1 neuropathogenesis has been revealed in experimental and clinical studies examining substance abuse-HIV-1 interactions. The latest evidence suggests that glia are direct targets of substance abuse and that the accelerated neurodegeneration seen with substance abuse in HIV-1 infection is largely secondary to drug actions in glia (Peterson et al. 1998; Hauser et al. 2005). In this review, we consider glial function in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection and examine how the actions of opiates, psychomotor stimulants (methamphetamine and cocaine), and alcohol on glia contribute to the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection in the CNS (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Summary of substance abuse and HIV-1 interactions in the CNS.

Opiates exacerbate the effects of HIV-1 through direct actions in µ opioid receptor (MOR)-expressing neurons, microglia and astroglia. MCP-1, IL-6, and RANTES production by astroglia are increased by heroin/morphine, which increases preexisting inflammation caused by HIV-1, increases macrophage/microglial activity and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Alcohol abuse compromises the blood brain barrier (BBB), increases viral entry, and ROS through the recruitment/enhanced turnover of macrophages within the CNS. Acute methamphetamine use increases dopamine (DA) and glutamate release and increases ROS production in DA terminals, which further compromises DA terminals damaged by methamphetamine. Cocaine blocks monoamine transporters with approximately equal affinity for the DA, serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) transporters disrupting signaling and contributing to local oxidative damage. Abbreviations: DA transporter (DAT); 5-HT transporter (SERT); NE transporter (NET) vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT2).

With the exception of alcohol, this review focuses on illicit drugs with abuse liability. Other illicit drugs such as marijuana and ecstasy, as well as licit drugs such as nicotine, have or are likely to have interactions with HIV-1 that enhance neuropathogenesis, but are not covered in this review. The effects of cannabinoids in HIVE/immune modulation have been reviewed before (Cabral and Dove Pettit 1998; Croxford 2003; Cabral and Marciano-Cabral 2005; Cabral and Staab 2005; Mackie 2006). Moreover, the consequences of polydrug use, which is prevalent in the United States, are likely to have considerable impact on HIV-1 pathogenesis; however, polydrug interactions are difficult to predict without considerable additional study.

1. Substance abuse and HIV-1 neuropathogenesis

Unique aspects of substance abuse-HIV interactions have been emphasized in an earlier review related to opioid abuse (Hauser et al. 2005); however, key considerations for understanding drug-HIV-1 interactions that can be generalized to all abused substances are listed below:

HIV/AIDS is a global pandemic with severe human and economic consequences.

Substance abuse and HIV are interlinked epidemics— In North America, Western Europe, and Australia, in particular, AIDS spreads through injection drug use or through the exchange of sex for drugs.

A variety of abused substances exacerbates the neuropathogenesis and neurological complications of HIV-1 through direct actions in the CNS. The deleterious effects are complex, and mediated through actions in neurons, astroglia, and microglia.

Abused substances act by mimicking/disrupting specific neurochemical systems. Understanding how endogenous neurochemical systems modulate HIV-1 neuropathogenesis is fundamental toward understanding neuroAIDS and for developing therapeutic strategies to counter HIV-1 disease progression.

Because addictive behaviors are caused by drugs acting on the CNS, drug abuse is primarily a disorder of the central nervous system (Leshner 1997; Leshner and Koob 1999). Besides the direct cytotoxic effects on neural cells themselves, behavioral changes caused by HIVE and/or long-term exposure to drugs of abuse are likely to further influence the progression of both diseases.

Worldwide, about 40 million people are currently infected with HIV (UNAIDS 2006) and injection drug use is a major cause in the spread of the disease. HIV-1 infected injection drug abusers undergo an accelerated rate of progression to AIDS and HIV dementia (Nath et al. 2000; Nath et al. 2002). Not only does injection drug use increase the probability of contracting HIV (Des Jarlais and Friedman 1987; Des Jarlais et al. 1992), but equally important, and as outlined in this review, a wide variety of abused substances intrinsically alter the pathogenesis of HIV. Despite the interrelatedness of substance abuse and HIV-1-infection, the extent to which drugs per se drive the pathogenesis has been disputed; in part, because the findings from epidemiologic studies have not consistently matched experimental findings (Concha et al. 1992; Selnes et al. 1997; Nath et al. 2002; Donahoe 2004; Ansari 2004; Hauser et al. 2005). However, some of these discrepancies are explained by the complexities of drug-HIV-1 interactions and reconciled through careful modeling of lentiviral and drug effects (Donahoe 2004; Hauser et al. 2005; Burdo et al. 2006).

Glia are significant cellular targets for drug-HIV-1 interactions. Macrophages/Microglia are the principal sites of viral replication and sources of cellular and viral toxins. Determining the neurochemical basis of drug actions in this class of cells is essential toward understanding the effects of substance abuse in neuroAIDS. The effects of drug abuse span a wide range of functions in phagocytic cells. For example, besides viral replication, drug abuse can modify phagocytosis (Peterson et al. 1995), chemotaxis (Chao et al. 1997), and the production of oxidative products, as well as cytokine production/release (Wetzel et al. 2000; Peng et al. 2000) and the expression and function of cytokine receptors (Rogers and Peterson, 2003). In dendritic cells (DC), cocaine appears to act as cofactor in HIV pathogenesis by increasing the expression of dendritic cell-specific C type ICAM-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN, also known as CD209). DC-SIGN binds intact virions, which promotes the presentation of HIV-1 to T-lymphocytes thereby increasing rates of infection (Nair et al. 2005). This suggests an important possible mechanism of cocaine action in macrophages, which can also express DC-SIGN.

Microglia infected with HIV-1 release both viral and cellular toxins (Nath 1999). Cellular toxins include excitatory amino acids (glutamate and quinolinic acid), cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, platelet activating factor) and nitric oxide (Kaul et al. 2001; Garden 2002; Persidsky and Gendelman 2003; Kadiu et al. 2005). Viral toxins are proteins released from infected cells including gp120 (Dreyer et al. 1990), Tat (Sabatier et al. 1991; Haughey et al. 1999), and perhaps others (Piller et al. 1998; Nath 2002; Avison et al. 2003).

HIV-1 products selectively destabilize astroglial function (Holden et al. 1999; El-Hage et al. 2005), such that they are likely to have a diminished ability to provide metabolic (e.g., decreased buffering of extracellular glutamate and potassium) (Wang et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2004b) or trophic support (e.g., reductions in glial-cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and transforming growth factor-β) (Vivien and Ali 2006) to neurons. Astrocytes also release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-6 and chemokines such as CCL2 that can exacerbate macrophage recruitment and microglial activation (El-Hage et al. 2005; Hauser et al. 2005; Deshpande et al. 2005). Thus, toxic glial-neuron signaling is not limited to a particular glial type. Both HIV-1 infected/exposed microglia (Xiong et al. 2000; Persidsky and Gendelman 2003) and astroglia (discussed below) (Wang et al. 2004b; El-Hage et al. 2005; Deshpande et al. 2005) contribute toxic insults to neurons and/or have a diminished capacity to provide trophic and metabolic support to neurons. Infiltrating monocytes and lymphocytes can drive neuronal dysfunction directly or by modifying the response of bystander glia (Persidsky and Gendelman 2003; Kadiu et al. 2005; Gray et al. 2005; McCrossan et al. 2006).

Virally encoded proteins released from infected cells, which effect glia and neurons directly, cause many of the deleterious consequences of HIV-1. Residual viral proteins including Tat, gp120 and Vpr (Brack-Werner 1999; Nath 1999) are formed because the stoichiometry of virion assembly in infected neural cells is inexact and excess proteins can be actively released (e.g., Tat) or are released when infected cells die. For example, astroglia, which become latently infected, may produce disproportionate amounts of individual proteins (Brack-Werner 1999; Kramer-Hammerle et al. 2005). HIV-1 proteins, such as gp120 (Dreyer et al. 1990), Tat (Sabatier et al. 1991; Haughey et al. 1999), and Vpr (Piller et al. 1998), released from infected cells are directly neurotoxic (Mattson et al. 2005), despite the inability of the virus to infect neurons. Depending on the cell type, Tat can interact with a variety of receptors and molecular targets including a subset of integrins (αvβ3 and α5B1, a VEGF receptor, lipoprotein related protein receptor, and perhaps CXCR4 (Watson and Edwards 1999; King et al. 2006). Because of its highly basic nature and its ability to translocate biological membranes, Tat is likely to have interact in a semi-selective manner with a variety of molecular targets (Prochiantz and Joliot 2003; Fittipaldi and Giacca 2005). As noted below, soluble gp120 interacts with CXCR4 and CCR5 chemokine receptors, as well as other potential targets, to induce CNS toxicity and inflammation (Moore 1997; Kaul and Lipton 1999; Khan et al. 2004; Misse et al. 2005). The mechanisms by which Tat and gp120 cause glial activation and neuronal injury have been extensively reviewed (Nath 1999; Kaul et al. 2001; Mattson et al. 2005; Kaul and Lipton 2005; King et al. 2006).

2. Glial mechanisms of drug-induced exacerbation of HIV-1 neuronal injury

The mechanisms underlying neuronal injury per se in HIVE in the presence or absence of substance abuse have been reviewed elsewhere (Nath et al. 2000; Nath et al. 2002; Mattson et al. 2005; Hauser et al. 2006b). Many of the neurotoxic effects are mediated by HIV-1 exposed microglia with some evidence that astroglia are also involved (Kaul et al. 2001; Hauser et al. 2005; Deshpande et al. 2005; Kaul and Lipton 2005; Kadiu et al. 2005). Briefly, HIV-1 Tat or gp120 both activate caspase-3 and induce death in neurons (Garden et al. 2002; Singh et al. 2004). A wide variety of diverse proapoptotic events and pathways have been implicated in HIV-1-induced neurodegeneration, which likely reflects the actions of multiple cellular and viral toxins, including both caspase-dependent and independent apoptotic pathways. Examples include p38 MAPK (Hu et al. 2005; Singh et al. 2005) and glycogen synthetase kinase-3β (GSK3β) (Maggirwar et al. 1999; Tong et al. 2001; Everall et al. 2002). HIV-1 Tat or gp120 both activate caspase-3 and induce death in neurons (Kruman et al. 1998; Garden et al. 2002) and the caspase-independent apoptotic effector endonuclease G is also activated by HIV-1 Tat (Singh et al. 2004). In HIV-1 infected brain, the activation of multiple proapoptotic pathways in target neural cells likely reflects the actions of several viral toxins. The combination of morphine and Tat also causes modest, but significant increases in astrocyte death after 96 h of continuous exposure (Khurdayan et al. 2004).

Opiates

To the extent that astrocytes provide metabolic support for neurons, their loss or their declining metabolic support would promote neurodegeneration. HIV-1 gp120 and Tat affect ion homeostasis in astroglia, which is predicted to compromise neurons (Pulliam et al. 1993; Benos et al. 1994a; Benos et al. 1994b; Holden et al. 1999). HIV-1 and gp120 also markedly inhibit glutamate uptake by astrocytes and cause reductions in excitatory amino acid trasporter-2 (EAAT2) mRNA and protein levels (Wang et al. 2003). The inability of astrocytes to buffer extracellular glutamate is likely to decrease the excitotoxic threshold of bystander neurons. Claims that a particular signaling event or pathway actually mediates neuronal death should be confirmed experimentally since activation of caspase-3 does not necessarily predict death. For example, significant increases in caspase-3 activation are not accompanied by death of Tat-treated neurons by 44 h later (Singh et al. 2004).

Toxic production of ROS and nitric oxide by HIV-1-expsoed macrophages likely exacerbate metabolic compromises in neurons and astroglia caused by viral infection and the resultant inflammatory response (Koka et al. 1995; Nath 1999; Kaul et al. 2001; Persidsky and Gendelman 2003). Activation of mu opioid receptors through opioid abuse increases ROS production by macrophages (Peterson et al. 1998). By contrast, kappa opioid receptor activation, or opioid receptor blockade with naloxone, can significantly reduce oxyradical production by macrophages/microglia (Hu et al. 1998; Liu et al. 2002). While aspects of macrophage and microglia function are likely to be beneficial, the net effects of microglial activation and increased ROS production caused by drug abuse and HIV-1 exposure are deleterious. Evidence for this includes findings that drugs such as minocycline, which attenuate macrophage/microglial function, are on balance neuroprotective (Sriram et al. 2006). Co-culture studies also indicate that HIV-1 exposed macrophages/microglia release products that are toxic to neurons. Thus, increases in macrophage/microglial numbers in the context of HIVE and drug abuse are thought to be key mediators of the ensuing neurodegenerative changes.

Opiates affect the pool of macrophage/microglial populations in human and experimental models of neuroAIDS, which suggests the trafficking and turnover of macrophages in the CNS is affected. For instance, systemic morphine treatment markedly increases the number of macrophages/microglia at sites of intrastriatal Tat injection (El-Hage et al. 2006b). The increases in macrophages/microglia caused by combined morphine and Tat treatment can be prevented by concurrent administration of naltrexone suggesting the cellular increases are mediated by opioid receptors (El-Hage et al. 2006b). The effects of opiates on SIV progression in non-human primates have yielded disparate results attesting to the complexities of drug abuse-HIV-1 interactions. Variable outcomes of studies examining the effects of opiates on SIV or simian/human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) disease progression have been attributed to differences in the pharmacodynamics of opiate administration (Donahoe et al. 1993) and differences in SIV/SHIV strains and neurovirulence (Suzuki et al. 2002; Kumar et al. 2004; Chuang et al. 2005) (reviewed by Burdo et al. 2006).

Compared to other sites, the CNS may be especially vulnerable to drug abuse-HIV-1 interactions (Nath et al. 2002; Hauser et al. 2005). The preferential susceptibility of the CNS is a likely consequence of the unique response of neurons and astroglia to HIV-1 and/or abused substances (Hauser et al. 2005). An example of this provided by studies of macrophages/microglia whose response to opiates is contextual; microglial motility is inhibited when isolated cells are exposed to opiates; however, when microglia are co-cultured with astrocytes, their motility is markedly enhanced by opiates (El-Hage et al. 2006b). Localized responses within the infected CNS may contribute to regional differences in microglial recruitment/activation. In a cohort of substance abusers who preferentially abuse opioids (Bell et al. 1998), there is a trend toward increased microglial numbers in HIV-1 encephalitis-positive opiate abusers (Tomlinson et al. 1999; Arango et al. 2004). When comparing drug abusers with non-abusers, the largest trends toward increased microglia were evident in the gray matter of the thalamus and hippocampus, while increases were not apparent in the frontal lobe (Arango et al. 2004). An assessment of CD14, CD16, major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II), and CD68 immunoreactive macrophages/microglia in HIV-1-seropositive drug abusers finds increased numbers of MHC II and CD68-expressing cells in individuals preferentially abusing opiates compared to non-abusers. This suggests that opiates increase microglial turnover, which may aggravate the effects of HIV-1 (Anthony et al. 2005).

Psychomotor stimulants

Neurons are likely to be the primary targets of cocaine and methamphetamine neurotoxicity, in addition to some direct actions mediated by glia. For example, methamphetamine administration associated with striatal gliosis in rats may be triggered by the degenerating dopamine terminals, or glutamate release and/or the production of free radicals (Pu and Vorhees 1993; Pu et al. 1996). The molecular targets for psychostimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine on astrocytes are incompletely understood but likely act through distinct mechanisms (Riddle et al. 2002).

It is generally accepted that methamphetamine damages a number of brain structures, most notably the basal ganglia (Seiden and Ricaurte 1987). Although the acute effects of methamphetamine include the release of dopamine from presynaptic terminals, repeated administration of methamphetamine causes long lasting decreases of striatal dopamine (and serotonin) and its metabolites (Kogan et al. 1976; Wagner et al. 1980; Cass 1997) that result from the destruction of dopaminergic terminals in the caudate nucleus (Wagner et al. 1980; Brunswick et al. 1992; Nakayama et al. 1993). Methamphetamine is thought to target the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), thereby inhibiting vesicular transport and elevating levels of dopamine within the presynaptic terminal (Hanson et al. 2004a; Hanson et al. 2004b). Dopamine and oxidative byproducts further reduce levels of VMAT2 creating a destructive positive feedback cycle. The dopamine transporter (DAT) and/or transporter function is lost, which causes additional buildup of dopamine and seemingly signals destruction of the presynaptic terminal. In humans, several (but not all) markers of dopamine nerve terminals are reduced in brains of chronic methamphetamine users (Wilson et al. 1996) and these effects may be long lasting (McCann et al. 1998).

The consequences of methamphetamine abuse and disruptions to dopaminergic function are especially deleterious with HIVE (Nath et al. 2000). HIV-1 and SIV cause dopamine depletion and the loss of dopamine terminals (Reyes et al. 1991; Nath et al. 2000; Czub et al. 2001; Maragos et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2004a) and this may be exacerbated by methamphetamine (Nath et al. 2000; Czub et al. 2001; Maragos et al. 2002; Cass et al. 2003; Scheller et al. 2005) or dopamine agonists (Nath et al. 2001; Czub et al. 2001; Czub et al. 2004). When methamphetamine is administered after intrastriatal HIV-1 Tat injection it acts synergistically to reduce levels of dopamine and its metabolites (dopamine D2 receptors— as assessed by raclopride binding) (Maragos et al. 2002). This is accompanied by neurodegeneration that specifically involves the loss of dopamine terminals and/or macrophage/ recruitment and microglial activation in rodent and non-human primate models (Czub et al. 2001; Flora et al. 2003; Theodore et al. 2006a). Minocycline, which preferentially blocks macrophage/microglial activation, attenuates methamphetamine neurotoxicity suggesting that macrophages/microglia cause the synaptic losses (Sriram et al. 2006), suggesting that methamphetamine exacerbates the neurotoxic effects of HIV-1 through enhanced microglial activation. On the other hand, Tat alone mediates much of the glial proliferative and cytokine/chemokine-secreting effects of HIV-1. Moreover, the dopamine losses caused by SIV can be also prevented by inhibiting macrophage/microglial activity (Scheller et al. 2005). These later observations imply that the interactions between methamphetamine and HIV-1 are bidirectional. However, it is still uncertain how the damage of presynaptic dopamine terminals signals these toxins signal the activation of microglia (Thomas et al. 2004b). The neurotoxicity and microglial activation caused by methamphetamine can be blocked by the NMDA receptor antagonists MK-801 or dextromethorphan (Thomas and Kuhn 2005), suggesting that microglial activation and dopamine terminal losses may be intimately linked to an excitotoxic glutamate response. In HIV-positive patients that abused methamphetamine, extensive loss of calbindin-immunoreactive interneurons in the frontal cortex has been reported (Langford et al. 2003), indicating that frank neuronal loss in regions outside of the basal ganglia may also be a consequence of methamphetamine abuse in this patient population.

Methamphetamine increases HIV-1/SIV neurotoxicity. Proximally, this might be a consequence of increased viral replication (Gavrilin et al. 2002) resulting in an increase in viral load (Ellis et al. 2003). Microarray studies show an upregulation of interferon-inducible genes in HIV-1 infected individuals with methamphetamine use (Everall et al. 2005a). Methamphetamine use has been speculated to be contributing to the emergence of distinct neurological variants of HIVE (Everall et al. 2005b). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) spectroscopy suggests similar changes occur clinically and that reductions in N-acetylaspartate signaling associated with declining neuronal function as directly proportional to methamphetamine dose (Chang et al. 2005). Declining N-acetylaspartate signals are preceded temporally by increases in choline and myoinositol signals, which are indicative of increased glial activation (Chang et al. 2005). The increased choline and myoinositol levels coincide with increased levels of MCP-1 in CSF and cognitive impairment and appear to be partially reversible by aggressive HAART strategies (Chang et al. 2004).

Striatal astrocytes treated with methamphetamine reveal gliotic changes including increased morphologic complexity related to increased stellate appearance, increased vacuoles, increased GFAP content, and decreases in intracellular glutamine synthetase. In addition, there was heterogeneity of astrocytes response depending on brain region (Stadlin et al. 1998). Methamphetamine inhibits monoamine oxidase and causes increased dopamine levels in cultured striatal astrocytes (Kita et al. 1998). More recently, astroglia have been reported to be involved in methamphetamine-induced reward and dependence (Miyatake et al. 2005; Narita et al. 2006). Methamphetamine and HIV-1 Tat together increase the activity of proteinases that degrade the extracellular matrix and are important in cytokine signaling (Conant et al. 2004), suggesting that, in addition to microglia, astroglia could play a significant role in methamphetamine-HIV-1 interactions.

Cocaine also increases HIV-1 neuropathogenesis as assessed using the HIV-1-infected, human PBMC SCID mouse model (Tyor and Middaugh 1999). Cocaine causes interactive neurotoxicity with Tat in rodent neurons in vitro and in vivo (Roth et al. 2005; Kendall et al. 2005; Aksenov et al. 2006). The extent that the interactive effects of cocaine and HIV-1 in the CNS are mediated by glia is uncertain; although cocaine does have potent effects on astroglial function that likely modulate their response to HIV-1. For example, cocaine has potent effects on microvascular permeability and the movement of leukocytes across the blood brain barrier (Fiala et al. 2005), which may be secondary to changes in astroglial function. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of in vivo astroglial response to cocaine indicates a doubling of intracellular GFAP within the dentate gyrus immediately after cocaine administration followed by a slow decline to almost normal levels during the following 14 days. In addition, astrocyte numbers were significantly increased, astrocyte size was decreased, and complexity of astrocyte shape was increased over 14 days of cocaine administration (Fattore et al. 2002). Cocaine-induced increases in chemokine production in HIV-1 infected macrophages (Nair et al. 2000), may further hasten inflammation and possibly neurodegenerative changes. Although cocaine acts differently from methamphetamine, increases in dopamine levels are likely to accumulate creating oxidative stress.

Alcohol abuse

The independent effects of alcohol and HIV-1 in the central nervous system (CNS) are multifaceted and complex. Significant neuro-cognitive impairment is seen in alcoholics and patients with HIV-1-associated dementia (HAD) (Schulte et al. 2005; McArthur et al. 2005). Alcohol abuse/dependence was a significant risk factor for cognitive impairment in HIV-1 infected patients (Becker et al. 2004). Neuropathologic correlates of HAD, HIV-1 encephalitis (HIVE) are characterized by monocyte/macrophage infiltration, diffuse activation of microglia, productive HIV-1 infection of macrophages and neuronal injury (Adamson et al. 1999; Persidsky and Gendelman 2003). Neuropathologic changes detected in the brain tissue of chronic alcoholics indicate that alcohol abuse leads in neuronal degeneration, ranging from minor dendritic structural change and synaptic changes to neuronal cell death in the CNS (Harper 1998). Neuropathologic evaluation of brain tissues from individuals with HIVE and alcohol abusers revealed similar neuropathologic changes in both conditions (Sullivan and Pfefferbaum 2005). Although it has been suggested that the CNS suffers the additive effects of alcohol abuse and HIV-1 infection (Ashida, 2001; (Meyerhoff et al. 1999; Durvasula et al. 2006), mechanistic studies assessing combined CNS injury are very limited. Importantly, macrophage/microglial activation (an important neuropathologic indicator of HAD) was noted in animals chronically exposed to alcohol (Riikonen et al. 2002). In vitro data and results obtained in animal models suggest that alcohol abuse could increase HIV-1 replication through yet unknown pathways (Wang et al. 2002; Bagby et al. 2003; Kumar et al. 2005).

Oxidative stress stemming from alcohol metabolism in macrophages or other neural cells could be the cause heightened neuronal injury, microglial activation and impaired immunity (via suppression of immunoproteasomes in antigen-presenting cells) (Haorah et al. 2004). In addition, blood brain barrier compromise also can contribute to alcohol-mediated neurodegeneration. Alcohol metabolism in brain endothelial cells results in oxidative stress, impairment of tight junctions and augmented migration of monocytes across endothelial cell monolayers (Haorah et al. 2005), changes observed in HIVE in humans (Persidsky et al. 2006).

3. Substance abuse and HIV-1 replication/expression in the CNS

Macrophages/Microglia

The role of microglia in HIV neuropathogenesis is well established (Tyor et al. 1995; Glass et al. 1995; Kaul et al. 2001; Persidsky and Gendelman 2003; Kadiu et al. 2005). HIV-1 can traffic into the CNS through infected monocytes (Hickey and Kimura 1988; Persidsky and Gendelman 2003; Jones and Power 2005; Kadiu et al. 2005) termed the “Trojan horse” phenomenon. Infected monocytes preferentially enter the perivascular compartment (Virchow-Robin space) and macrophages within this compartment display heightened turnover (Kim et al. 2005). Once viral entry occurs, perivascular macrophages and microglia are the principal reservoir for HIV-1 in the CNS (Kramer-Hammerle et al. 2005).

Microglia are the only brain-resident cells to harbor productive HIV-1 infection, and extensive microglial activation is a characteristic feature of HIV-1 dementia (Tyor et al. 1995; Glass et al. 1995; Kaul et al. 2001; Persidsky and Gendelman 2003; Kadiu et al. 2005). Levels of microglial activation correlate positively with HIV-1 dementia (Tyor et al. 1995; Glass et al. 1995). Microglia express a wide variety of neurochemical receptors, transporters, and molecular targets permitting them to be a direct target for abused substances. This includes opioid receptors; glutamate receptors [N-methyl-D-aspartate and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA) receptors] (Hagino et al. 2004); dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine transporters (Mahe et al. 2005; Farber et al. 2005). Determining how substance abuse effects HIV-1 replication, latency, and reactivation is essential toward understanding drug-HIV-1 interactions and will provide insight into the neurochemical basis of HIV-1 neuropathogenesis in non-drug abusing populations.

Opiates increase viral expression or replication in macrophages (Li et al. 2003). Although macrophages/microglia can express mu, delta, and/or kappa opioid receptor types, commonly abused opiate drugs such as heroin, oxycodone, and morphine preferentially activate mu opioid receptors (Hauser et al. 2005; Hauser et al. 2006b). In general, mu opioid receptor activation enhances viral expression and replication in macrophages. However, alternative, kappa and delta opioid receptors can differentially affect macrophage function including their response to HIV-1.

For example, while mu opioid receptor activation increases HIV-1 expression in monocytic cells (Peterson et al, 1999; Peterson et al, 1993), kappa opioid receptor activation can have the opposite, inhibitory effect on HIV-1 expression in monocytic and lymphocytic cells (Chao et al, 1996; Chao et al, 2001; Peterson et al, 2001). Another example of opposing actions of mu and kappa opioid receptor activation relates to the ability of opiate drugs to induce apoptosis in macrophages via mu opioid receptors (Singhal et al. 1998; Singhal et al. 2002). In this instance, the activation of mu opioid receptors may be beneficial by limiting the ability of macrophages to harbor and continue to disseminate virus, while kappa opioid receptor protection may be detrimental in macrophages. Thus, opioids can significantly modulate the pathogenesis of HIVE through multiple cellular mechanisms of action in macrophages. The effects of opioids are highly contextual and as true modulators—are often dependent on other permissive factors (Hauser and Mangoura 1998). For example, morphine generally inhibits macrophage/microglial motility or chemotaxis directly in isolated cultures; however, when astroglia and microglia are cultured in transwells with Tat and morphine, the opposite effect is obtained and microglial motility is increased (El-Hage et al. 2006b).

The effects of drugs besides opioids on HIV-1 replication in macrophages/microglia are less well studied but likely to be significant. There is considerable co-morbidity between psychomotor stimulant use and HIVE (Goodkin et al. 1998; Gekker et al. 2004). Cocaine can enhance mesangial cell proliferation in the presence of macrophages (Mattana et al. 1994), and enhance monocyte migration into the CNS (Fiala et al. 1998). Cocaine also augments apoptosis of brain endothelial cells, which may increase trafficking across the blood-brain-barrier (Zhang et al. 1998). Cocaine can increase HIV-1 replication in macrophages/microglia (Shapshak et al. 1996; Baldwin et al. 1998), and this can be suppressed through KOR activation (Gekker et al. 2004). Blockade of sigma-1 receptors attenuates cocaine-enhanced viral replication in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice inoculated with HIV-1 infected human PBMCs suggesting a mechanism of action (Gardner et al. 2004; Roth et al. 2005).

Evidence suggests that methamphetamine enhances HIV-1 expression through complex actions on the immune system (Ellis et al. 2003). Methamphetamine has complex effects on macrophage function (In et al. 2005) and its direct role in HIV-1 expression in this cell type needs further study. Methamphetamine suppresses tumor cell killing, CD14 expression, nitric oxide production and cytokine release by macrophages in LPS exposed mice (In et al. 2004). Exposure to the methamphetamine analog (±)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) effects macrophage cytokine production and their T-cell regulatory functions (House et al. 1995). Collectively, these findings suggest that psychomotor stimulants directly modify AIDS progression through direct mechanisms involving viral replication and expression.

Peripheral adaptive immune responses [including virus-specific cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTL)] appear to control HIV-1 replication in the CNS (Potula et al. 2006). It is plausible to suggest that alcohol impairs immune responses leading to increased viral replication, enhanced neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration. Indeed, chronic exposure to alcohol affected clearance of virus-infected macrophages from the brain in a murine model of HIVE, augmented viremia, and increased microglial reaction, suggesting that alcohol abuse can exacerbate HIV-1 CNS infection (Potula et al. 2006).

Astroglia

Astroglia are a significant target for HIV and their function is markedly impacted by the disease (Nath et al. 1999; Brack-Werner 1999; Nath 1999; Gorry et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2004b). Astrocytes express opioid receptors, some monoamine and glutamate transporters, and respond directly to abused substances (Hauser et al. 1996; Stiene-Martin et al. 2001; Kubota et al. 2001; Takeda et al. 2002; Inazu et al. 2003). It is generally believed that astrocytes cannot become productively infected with HIV-1 (Nath et al. 1999; Brack-Werner 1999; Nath 1999; Gorry et al. 2003; Managlia et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2004b). The reasons why astroglia do not become productively infected are debated (Lambotte et al. 2003; Kramer-Hammerle et al. 2005). Latency may involve cell-type specific differences in cyclin T1 (Chen et al. 2006). Alternatively, differences in Rev cofactors that are unique to astrocytes, may prevent viral translation (Fang et al. 2005; Kramer-Hammerle et al. 2005). Inefficient viral entry has also been proposed to limit astroglial infectivity (Nitkiewicz et al. 2004). Extracellular factors such as cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) can differentially regulate viral expression by astrocytes (Tornatore et al. 1994), although attempts to use cytokines to reactivate simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in astrocytes have not been successful (Guillemin et al. 2000). The speculative notion that other stressors such abused substances may also influence HIV-1 infection in astrocytes, including mechanisms associated with viral latency/persistence and potentially reactivation warrants further study as a potentially novel mechanism of drug action in astrocytes.

Neural precursors/stem cells

Immature neural progenitors or progenitor-derived astrocytes can be infected with HIV-1 (Lawrence et al. 2004). Those progenitor cells that differentiate toward a glial fate display increased viral production (Lawrence et al. 2004) and express increased levels of proinflammatory chemokines (Lawrence et al. 2006). In addition, macroglial precursors may be more vulnerable to HIV-1 or viral proteins than mature astroglia (Khurdayan et al. 2004). HIV-1 Tat exposure increases active caspase-3 immunoreactivity and cell death in oligodendrocyte-type 2 astrocyte (O-2A) progenitors when coadministered with opiates, while more mature astroglia or oligodendroglia appear to be less vulnerable. The reasons for the enhanced cytotoxicity may include enhanced CXCR4/CCR5 cofactor expression by immature neural precursors (Ni et al. 2004), although neural progenitors may be generally more susceptible to toxic environmental insults (Khurdayan et al. 2004). Fetal and adult neural precursors are sensitive to a variety of abused substances including opioids, methamphetamine, cocaine and alcohol (Lidow and Song 2001; Duman et al. 2001; Hauser et al. 2003; Crews and Nixon 2003; Harvey 2004; Yamaguchi et al. 2004; Abrous et al. 2005). Moreover, neural precursors express HIV-1 chemokine receptor cofactors (Tran et al. 2004; Tran and Miller 2005), are responsive to HIV-1 (Krathwohl and Kaiser 2004; van Marle et al. 2005), and are potential cellular targets for drug-HIV-1 interactions (see also Kao and Price 2004).

In support the concept that neural stem cells are direct targets for substance abuse-HIV-1 interactions, stem cells can express a variety of drug and chemokine receptors. Opioid receptors are expressed by neural precursor cells in the ventricular and subventricular zones of the developing and adult CNS (Zhu et al. 1998; Reznikov et al. 1999; Stiene-Martin et al. 2001; Persson et al. 2003a; Persson et al. 2003b). Exposure to endogenous opioids or opiate drugs with abuse liability can effect the proliferation, differentiation and survival of neuronal and glial precursors and their progeny (Zagon and McLaughlin 1983; Hauser et al. 1989; Eisch et al. 2000; Stiene-Martin et al. 2001) (reviewed by Hauser and Mangoura 1998; Hauser et al. 2003). O-2A progenitors are preferentially vulnerable to combined morphine and HIV-1 Tat exposure (Khurdayan et al. 2004). Similarly, dopamine receptors are expressed by mouse embryonic stem cells (Hoglinger et al. 2004; Kippin et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2006). Because neurogenesis is affected by ethanol exposure (Ma et al. 2001; Nixon and Crews 2002; Nixon and Crews 2004), and because key receptor targets modified by ethanol, including GABA, L-type Ca2+ channels, and NMDA receptors are also developmentally regulated in immature neural cells/precursors (Ben-Ari et al. 1997; Lee et al. 2006; D'Ascenzo et al. 2006) and modulated by HIV-1 (Zocchi et al. 1998; Holden et al. 1999; Haughey et al. 2001; Kolson 2002; Kaul and Lipton 2004), ethanol-HIV-1 interactions are likely to effect neural stem cells.

4. Substance abuse, HIV-1, and cytokine/chemokine production in the CNS

Cytokine production is an inherent part of the innate response of the CNS to HIV-1 and viral products and is an integral component neuroimmune modulation of the disease. TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β, for example, are greatly increased in HIVE and contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease (Mayne et al. 1998; Kadiu et al. 2005). HIV-1 exposed astroglia, microglia, and endothelial cells can release cytokines, and there is emerging evidence that compromised neurons may also be important sources of proinflammatory chemokines such as interferon-α, fractalkine (Streit et al. 2005), and CXCL10/IP-10 (Sui et al. 2004; Sui et al. 2006).

Macrophages/microglia

The effects of opioids on immune function have been extensively reviewed (Adler et al, 1993; Peterson et al, 2001; Sharp et al, 1998) (Roy et al. 2006). Peripheral leukocytes including lymphocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are important cellular targets of opiate drug abuse (Tomassini et al. 2004; Roy et al. 2004). Proopiomelanocortin-derived (POMC) peptides share properties with IFN-α and vice versa (Blalock 2005) and intracerebroventricular administration of IFN-α causes catatonia similar to that seen with β-endorphin, which is antagonized by naloxone (Blalock and Smith 1981). Interestingly, the similarities between POMC derivative and IFN-α may relate to peptide homologies rather than heterologous receptor-effector pathway interactions discussed in the next paragraph.

The activation of mu opioid receptors can modulate the function of chemokine receptors, including those that serve as co-receptors for HIV-1 (e.g., CCR3, CCR5, CCR2, and CXCR4) (Grimm et al. 1998) (Rogers and Peterson, 2003). Conversely, chemokine receptors can also modulate opioid receptor function, and bi-directional heterologous interactions between opioid and chemokine receptors have been noted (Rogers et al, 2000) (Rogers and Peterson, 2003). Thus, opioids are intimately involved in immune function and can provoke diverse immune responses depending on the particular opioid receptor and cell type that are affected. However, on balance and despite a few exceptions, the typical/net consequence of drug abuse and preferential mu opioid receptor activation is to suppress peripheral immune function thereby promoting disease progression.

Intrastriatal Tat injection increases the proportion of F4/80-immunoreactive macrophages/microglia and GFAP-immunoreactive astroglia (El-Hage et al. 2006b). The reactive glial changes correlate positively with proximity to the injection epicenter. Moreover, if systemic morphine is coadministered via time-release, subcutaneous implants, the reactive glial changes worsen significantly and these effects can be reversed by concurrent naltrexone administration. Interestingly, both mu and non-mu opioid receptor immunoreactive subpopulations of macrophages/microglia display similar reactive increases and appear to respond similarly following morphine exposure (El-Hage et al. 2006b). This suggests that morphine does not act directly to increase macrophage/microglial numbers, but instead acts through another cellular intermediate, which we propose to be mu opioid receptor-expressing astrocytes (El-Hage et al. 2006b). In contrast, when methamphetamine is administered 24 hrs following intrastriatal injections of Tat, there is no augmentation in the proliferation of reactive glia (Theodore et al. 2006c), suggesting methamphetamine does not have an overt effect on the number of activated glia, per se. Whether this is true in the brains of methamphetamine abusing, HIV-positive patients remains to be determined.

As noted, sigma-1 receptors appear to mediate cocaine-enhanced viral replication and cytokine release in SCID mice inoculated with HIV-1 infected human PBMCs (Gardner et al. 2004; Roth et al. 2005). Cocaine also appears to alter the secretory function of macrophages. Both cytokine production and antimicrobial activity are suppressed in human alveolar macrophages by inhaled, alkaloidal cocaine or marijuana (Shapshak et al. 1996; Baldwin et al. 1998). Changes in chemokine or cytokine output are contextual, and possibly gender-related (Xu et al. 1997). Secretion may be downregulated, as is the case with MIP1α from normal or LPS-stimulated peripheral monocytes from HIV infected individuals (Nair et al. 2000) or IL-1 from LPS stimulated macrophages (Xu et al. 1997), or upregulated as is the case with interferon α/β, IL-8, MIP1α, MCP-1/CCL2, interferon-inducible protein-10/CXCL10, TNF-α and IL-6 in normal or LPS-activated human monocyte cultures (Zhang et al. 1998; Gan et al. 1999; Grattendick et al. 2000). The overall consequence of cocaine exposure is thus to enhance HIV-1 entry across the blood- brain barrier, through both direct effects on brain microvascular endothelial cells and through the effects of cocaine-induced proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Gene array studies show that methamphetamine increases MCP-1 transcript levels in the striatum several fold at 3 h following exposure (Thomas et al. 2004a), and methamphetamine elevates mRNA levels of proinflammatory mediators in macrophages/microglia, including IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1/CCL2 and TNF-α (Flora et al. 2002; Sriram et al. 2006).

Many of the effects of alcohol on HIV-1-induced inflammation have been measured outside the nervous system. Ethanol significantly influences chemokine release with HIV-1 infection (Wang et al. 1997; Bautista 2001), which includes increases in TNF-α and oxyradical production and alterations in chemokines including CCL5/RANTES, MIP-1, and CCL2/MCP-1 release by macrophages as related to liver disease (Bautista and Wang 2001; Bautista and Wang 2002). Additional studies of the effects of alcohol on cytokine changes in the CNS with HIVE are warranted.

Astroglia

Astrogliosis accompanies HIVE and HAD indicating the involvement of this cell type in the CNS response to HIV-1. Although aspects of the astroglial reaction are assumed secondary to neuronal injury and inflammatory products from macrophages/microglia, evidence also suggests that compromised astroglia can contribute directly to neuronal injury (Brack-Werner 1999; Nath 1999; Deshpande et al. 2005). In addition, a certain degree of the astroglial response is likely to be due to direct actions of HIV-1 virions themselves or viral proteins. Irrespective of the mechanisms involved, affected astrocytes fail to provide neurons with metabolic and trophic support, and also release neurotoxic molecules and promote inflammation.

Astrocytes express class II MHC, B7, and CD40, and co-stimulatory immune effectors (reviewed by Dong and Benveniste 2001) allowing them to play critical roles in immune function related to CNS diseases with an immune component, including HIV. Further, astrocytes can release cytokines exerting a variety of diverse effects including directing T-lymphocytes toward Th1 or Th2 response, or the recruitment of monocytes. Astroglial responses are contextual and dependent on the particular disease, traumatic or neurochemical insult, inputs from other affected cells, and the existing neurochemical and immune tone within the surrounding milieu. Additionally, responses may differ markedly among heterogeneous subpopulations of astroglia.

Extracellular exposure to intact virions or viral proteins can induce significant changes in astroglial function. Recent evidence indicates that this involves an increase in a specific HIV-1 and TNF-α-inducible gene termed astrocyte elevated gene (AEG)-1 (Kang et al. 2005; Emdad et al. 2006). HIV-1 or HIV-1 proteins can cause increased expression and/or release of chemokines and cytokines (Dong and Benveniste 2001), including TNF-α (El-Hage et al. 2005; Theodore et al. 2006b), FasL (Deshpande et al. 2005), MCP-1 (Conant et al. 1998; El-Hage et al. 2005; Theodore et al. 2006a), MIP1β (Mahajan et al. 2005) and TIMP (Theodore et al. 2006a), which are likely to induce neurodegeneration through the recruitment of inflammatory cells. However, alternative effects of HIV in astrocytes including disruptions to glutamate transport (Wang et al. 2003) and a loss of calcium homeostasis (Holden et al. 1999; El-Hage et al. 2005) (discussed below) and an impairment in mitochondrial function (Langford et al. 2004) may be equally critical in producing neuronal dysfunction.

Deleterious effects of methamphetamine appear to be mediated through increases in TNF-α and MCP-1 (Theodore et al. 2006a; Theodore et al. 2006b), while effects of alcohol are likely to involve IL-1β (Flora et al. 2005). By contrast, opiates do not increase the release of TNF-α, IL-1β, or IFN-α by astroglia (El-Hage et al. 2005). Although cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β are inherently released in response to HIV-1 products, they may be necessary to trigger subsequent chemokine release by astroglia (Luo et al. 2003).

Substance abuse exacerbates chemokine release by HIV-1-exposed astrocytes

Chemokines are important mediators of HIV-1 neuropathogenesis (Miller and Meucci 1999). HIV-1 gp120 and Tat exposure increases chemokine expression and/or release by astrocytes (Conant et al. 1998; Nath et al. 1999; Mahajan et al. 2005), and several abused substances appear to leverage their effects markedly by increasing chemokine release (El-Hage et al. 2005; Flora et al. 2005; Theodore et al. 2006a). HIV-1 Tat selectively interacts with C/EBPβ to affect MCP-1 expression in astrocytes (Abraham et al. 2005). We have found that morphine, acting through mu opioid receptors, synergistically increases the release of MCP-1 and other chemokines (RANTES and MCP-5) by HIV-1 Tat-exposed astrocytes, which increases macrophage recruitment and microglial activation in vivo (El-Hage et al. 2005). The studies on opiate modulation of MCP-1 release by astrocytes have been reviewed (Hauser et al. 2006b). We have recently found that the increases in macrophage/microglial chemotaxis toward sites of intrastriatal Tat injection in morphine-exposed mice are significantly reduced in CCR2 null mice compared to wild-type controls (El-Hage et al. 2006a). Thus, MCP-1 produced by HIV-1 Tat and opiate-exposed astroglia contributes markedly to microglial chemotaxis.

Unlike the effects seen with mu opioid receptors, kappa opioid receptor stimulation inhibits (or has no apparent effect on) Tat-induced MCP-1 expression in astrocytes (Sheng et al. 2003; El-Hage et al. 2005). Important differences in mu and kappa receptor signaling by astrocytes likely underlie the unique actions at each opioid receptor type (Bohn et al, 2000) (Belcheva et al. 2005). The differential response of astrocytes to mu- and kappa-opioid receptor activation is likely to be important for HIV-1 neuropathogenesis. This is likely to be important when considering agents used to treat addictive disorders such as buprenorphine with mixed mu agonist and kappa opioid receptor antagonist properties.

Abused substances other than opioids can trigger chemokine production by HIV-1 exposed astroglia (Toborek et al. 2003; El-Hage et al. 2005; Flora et al. 2005; Mahajan et al. 2005). Acute exposure to opiates, methamphetamine, cocaine, or ethanol can potentiate the effects of viral proteins, although by themselves the drugs minimally affect chemokine release (El-Hage et al. 2005; Flora et al. 2005; Mahajan et al. 2005; Theodore et al. 2006a). In the case of methamphetamine, it was recently shown that dopamine losses seen in mice exposed to both Tat and methamphetamine were partially abrogated when receptors for MCP-1 were lacking (Theodore et al. 2006a). Findings that all these drugs increase cytokine production by astrocytes in the presence of HIV were at first glance perplexing because each class of drug acts through distinct mechanisms. One potential explanation involves the ability of astroglia to sense imbalances in neuronal function and respond to a broad class of neuronal stresses (Fields and Stevens-Graham 2002). We propose that the release of chemokines by astroglia is a generalized response to drug-induced neuronal stress/injury (as well as other stressors), which signal the need for heightened immune surveillance and action. Once macrophages and microglia are recruited, the situation is likely to be reassessed further and their specific response tailored to the particular CNS insult(s). Once the “uniqueness” of the situation is determined, subtle differences in the “signature” of the released cytokines and inflammatory response may evolve and likely vary for different drugs and viral insults.

Ethanol also increases MCP-1 release by HIV-1 Tat-exposed astrocytes (Flora et al. 2005), although by itself it can inhibit the production of some chemokines such as CXCL-10 (Davis and Syapin 2004). Ethanol induces increased death of astrocytes through a mechanism that involves Toll-like receptors and IL-1β signaling (Valles et al. 2004; Blanco et al. 2005). In the presence of HIV, cocaine increases chemokine production by brain microvascular endothelial cells (Zhang et al. 1998; Fiala et al. 2005), which may in part be mediated by astrocytes. Thus, chemokine release by astrocytes may be a generalized response of the CNS to substance abuse and HIV-1.

5. Clinical considerations

Species differences

It is important to consider species-specificity when considering how HIV-1 damages the CNS. Not only are species differences important because HIV-1 almost exclusively infects human cells, but also because of potential differences in inflammatory signaling and in free radical production. Moreover, disparities in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drug actions are also likely to be significant when consider substance abuse-HIV-1 interactions. For example, there are species differences in the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). While iNOS is important in host microbial defense, a downside is that iNOS can be toxic or cause death in bystander cells. Interestingly, unlike murine or rat microglia, which upregulate iNOS in response to inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, human microglia do not express iNOS (Lee et al. 1993; Peterson et al. 1994). Alternatively, iNOS is expressed by human astrocytes, which upregulate its activity in response to IL-1β. The relegation of iNOS expression to astrocytes suggests the importance of cooperative microglial-astrocyte interactions in iNOS induction and indicate important species differences (Lee et al. 1993). On the other hand, there can be remarkable similarities between the response of human and rodent neural cells to HIV-1 and viral proteins. For example, opiates exacerbate Tat and/or gp120 toxicity in murine and human neurons in culture (Gurwell et al. 2001; Hu et al. 2005; Turchan-Cholewo et al. 2006), and gp120 neurotoxicity is mediated by p38 MAPK in both species (Hu et al. 2005; Singh et al. 2005). There are parallels in the ability of opiates to increase microglial turnover in individuals with HIVE (Arango et al. 2004; Anthony et al. 2005) and increase microglial chemotaxis in mice in response to HIV-1 Tat protein (El-Hage et al. 2006b). The production of inflammatory chemokines such as MCP-1 by astrocytes is similar in both human and murine cells (Abraham et al. 2003; El-Hage et al. 2005). Species-specific pharmacological, immunological, and pathological differences need to be considered when exploring drug abuse-HIV-1 interactions in the CNS.

Interactions between drugs of abuse and HIV-1 therapeutic agents

Pharmacological differences among drug abuse therapies, including pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic disparities, are likely to have a profound effect on the pathogenesis of HIV-1 in the CNS. Moreover, when considered with adjunctive therapies for HIV itself or for prevalent co-infections such as hepatitis C infection, the complexities are greatly compounded. The individual agents comprising highly active-antiretroviral therapy (HAART) can interact with opiates (McCance-Katz 2005) or methamphetamine (Ellis et al. 2003) at multiple levels pharmacologically. Nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-NRTIs (NNRTIs), and protease inhibitors can effect opiate metabolism and vice versa. The illicit and licit opiates used to treat addiction uniquely differ in their interactions with individual HAART medications. Methadone and levo-α-acetyl-methadol, in particular, can adversely interact with some HAART components, while buprenorphine appears to have fewer deleterious interactions (McCance-Katz 2005). For example, the extent to which concurrent methadone therapy diminishes the zidovudine degradation and clearance of will likely limit its therapeutic effectiveness as a treatment for opiate addiction (Villafranca et al. 2005). By contrast, methadone reduces levels of the NRTIs, didanosine and stavudine, while some protease inhibitors can reduce methadone levels through common actions involving specific cytochrome P450 enzymes in hepatocytes (McCance-Katz 2005). The interactions are not limited to opiates since methamphetamine can also negate the therapeutic effects of HAART (Ellis et al. 2003). These are extremely important adverse interactions. Diminished HAART efficacy would likely have devastating consequences for AIDS progression. Conversely, reductions in the efficacy of treatments for substance abuse would discourage compliance and encourage relapse. The pharmacological properties of a drug such as buprenorphine are likely to make it advantageous in the treatment of opiate abusers with HIV-1 infection, although this needs to be tested directly (Hauser et al. 2005). Not only might buprenorphine’s inherent actions as a partial mu opioid receptor agonist may be protective in neuroAIDS (Hauser et al. 2006b), but the constant “steady state” levels seen with drug therapy in general are less likely to disrupt CNS function compared to “on-off” exposure accompanying substance abuse (Kreek 1987; Kreek 2001).

Chronic substance abuse and latent susceptibility to disease

Assuming chronic substance abuse modulates CNS organization and plasticity; might the drug-induced alterations to CNS organization be revealed or exaggerated by aging, disease, or environmental stressors? Restated, maladaptive, organizational changes might predispose the CNS to failure when confronted with non-drug related insults (Hauser et al. 2006a). This important question has been difficult to address because of challenges modeling chronic diseases such as drug abuse and neurological disorders in the laboratory and in non-human animal models. Based on evidence outlined herein, we propose that prior exposure to some abused substances might be particularly disruptive for individuals who become infected with HIV-1 (Hauser et al. 2006a). For example, methamphetamine and HIV-1 Tat, both of which can deplete dopamine systems, show synergistic damage to the striatum when rodents are acutely exposed to both agents (Maragos et al. 2002). It is reasonable to assume that, to the extent to which the effects of methamphetamine on dopamine terminals is lasting, this would increase the vulnerably of dopaminergic neurons to subsequent HIV-1 exposure. Alternatively, injury or HIV-1 Tat increases mu opioid receptor expression by macrophages/microglia and astroglia near the site of injury, which coincides with increase responsiveness to morphine.

Reversibility of neurocognitive defects

Current evidence indicates that the ravages of HIVE and neurocognitive losses may be reversible (Gendelman et al. 1998; Gray et al. 2001; Kolson 2002). As noted, cognitive declines are highly correlated with increases in MCP-1 in the CSF and this may be reversible (Avison et al. 2004; Chang et al. 2004). Neuroimaging deficits correlate with dendritic losses as assessed by microtubule associated protein (MAP2) immunoreactivity (Archibald et al. 2004). Dendritic losses and reductions in synapses, especially that seen with mild cognitive dementia (Everall et al. 1999), are believed to be recoverable (Bellizzi et al. 2006). The notion of reversibility is highly significant suggesting that there is considerable therapeutic promise for individuals with neuroAIDS. Moreover, actual cases of end-stage dementia are less common that previously reported, while neurocognitive losses may have been historically underestimated (Everall et al. 2005b), suggesting that the number of individuals that can helped is great. The potential for improved neurobehavioral outcome should be equally promising when extrapolated to drug abuse and neuroAIDS. Thus, strategies that reduce viral loads, inflammation, or limit exposure to abuse substances (addiction treatments or abstinence) may reverse the neurocognitive decline seen with substance abuse and neuroAIDS.

In summary, we propose that astroglia and microglia act in concert to mediate much of the pathologic response of the CNS to HIV-1 infection alone, and to HIV-1 infection combined with multiple drugs of abuse. Astroglia are sentinels whose surveillance of neuronal function and signaling may be directly affected by the abused substances themselves (e.g., opiates) or activated by drug-damaged neurons (e.g., methamphetamine exposed dopaminergic neurons). Through a variety of triggering events, astrocytes respond to viral and chemical insults by releasing immune mediators, which communicate and coordinate their response with that of microglia. Evidence suggesting that many of the neurocognitive defects seen with HIVE and substance abuse may be preventable and are potentially reversible indicates there is great promise for the future therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of The National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA19398 and DA13144) for supporting these studies.

References

- Abraham S, Sawaya BE, Safak M, Batuman O, Khalili K, Amini S. Regulation of MCP-1 gene transcription by Smads and HIV-1 Tat in human glial cells. Virology. 2003;309:196–202. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham S, Sweet T, Sawaya BE, Rappaport J, Khalili K, Amini S. Cooperative interaction of C/EBP beta and Tat modulates MCP-1 gene transcription in astrocytes. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005;160:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrous DN, Koehl M, Le MM. Adult neurogenesis: from precursors to network and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:523–569. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00055.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson DC, Kopnisky KL, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Mechanisms and structural determinants of HIV-1 coat protein, gp41- induced neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1999;19:64–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00064.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksenov MY, Aksenova MV, Nath A, Ray PD, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Cocaine-mediated enhancement of Tat toxicity in rat hippocampal cell cultures: the role of oxidative stress and D1 dopamine receptor. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari AA. Drugs of abuse and HIV--a perspective. J. Neuroimmunol. 2004;147:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony IC, Ramage SN, Carnie FW, Simmonds P, Bell JE. Does drug abuse alter microglial phenotype and cell turnover in the context of advancing HIV infection? Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2005;31:325–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2005.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango JC, Simmonds P, Brettle RP, Bell JE. Does drug abuse influence the microglial response in AIDS and HIV encephalitis? AIDS. 2004;(18 Suppl 1):S69–S74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald SL, Masliah E, Fennema-Notestine C, Marcotte TD, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Heaton RK, Grant I, Mallory M, Miller A, Jernigan TL. Correlation of in vivo neuroimaging abnormalities with postmortem human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis and dendritic loss. Arch. Neurol. 2004;61:369–376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avison M, Berger JR, McArthur JC, Nath A. HIV meningitis and dementia. In: Nath A, Berger JR, editors. Clinical Neurovirology. Marcel Dekker, Inc: New York; 2003. pp. 251–276. [Google Scholar]

- Avison MJ, Nath A, Greene-Avison R, Schmitt FA, Bales RA, Ethisham A, Greenberg RN, Berger JR. Inflammatory changes and breakdown of microvascular integrity in early human immunodeficiency virus dementia. J. Neurovirol. 2004;10:223–232. doi: 10.1080/13550280490463532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby GJ, Stoltz DA, Zhang P, Kolls JK, Brown J, Bohm RP, Jr, Rockar R, Purcell J, Murphey-Corb M, Nelson S. The effect of chronic binge ethanol consumption on the primary stage of SIV infection in rhesus macaques. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2003;27:495–502. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057947.57330.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin GC, Roth MD, Tashkin DP. Acute and chronic effects of cocaine on the immune system and the possible link to AIDS. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;83:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista AP. Free radicals, chemokines, and cell injury in HIV-1 and SIV infections and alcoholic hepatitis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;31:1527–1532. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista AP, Wang E. Chronic ethanol intoxication enhances the production of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 by hepatocytes after human immunodeficiency virus-1 glycoprotein 120 vaccination. Alcohol. 2001;24:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista AP, Wang E. Acute ethanol administration downregulates human immunodeficiency virus-1 glycoprotein 120-induced KC and RANTES production by murine Kupffer cells and splenocytes. Life Sci. 2002;71:371–382. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01687-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JT, Lopez OL, Dew MA, Aizenstein HJ. Prevalence of cognitive disorders differs as a function of age in HIV virus infection. AIDS. 2004;1(18 Suppl.):S11–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcheva MM, Clark AL, Haas PD, Serna JS, Hahn JW, Kiss A, Coscia CJ. Mu and kappa opioid receptors activate ERK/MAPK via different protein kinase C isoforms and secondary messengers in astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27662–27669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502593200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell JE, Brettle RP, Chiswick A, Simmonds P. HIV encephalitis, proviral load and dementia in drug users and homosexuals with AIDS. Effect of neocortical involvement. Brain. 1998;121:2043–2052. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.11.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi MJ, Lu S-M, Gelbard HA. Protecting the synaapse: evidence for a rational strategy to treat HIV-1 associated neurologic disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:20–31. doi: 10.1007/s11481-005-9006-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R, Leinekugel X, Caillard O, Gaiarsa JL. GABAA, NMDA and AMPA receptors: a developmentally regulated 'menage a trois'. Trends. Neurosci. 1997;20:523–529. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benos DJ, Hahn BH, Bubien JK, Ghosh SK, Mashburn NA, Chaikin MA, Shaw GM, Benveniste EN. Envelope glycoprotein gp120 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 alters ion transport in astrocytes: implications for AIDS dementia complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994a;91:494–498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benos DJ, McPherson S, Hahn BH, Chaikin MA, Benveniste EN. Cytokines and HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120 stimulate Na+/H+ exchange in astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994b;269:13811–13816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock JE. The immune system as the sixth sense. J. Intern. Med. 2005;257:126–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock JE, Smith EM. Human leukocyte interferon (HuIFN-alpha): potent endorphin-like opioid activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1981;101:472–478. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco AM, Valles SL, Pascual M, Guerri C. Involvement of TLR4/type I IL-1 receptor signaling in the induction of inflammatory mediators and cell death induced by ethanol in cultured astrocytes. J. Immunol. 2005;175:6893–6899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brack-Werner R. Astrocytes: HIV cellular reservoirs and important participants in neuropathogenesis. AIDS. 1999;13:1–22. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunswick DJ, Benmansour S, Tejani-Butt SM, Hauptmann M. Effects of high-dose methamphetamine on monoamine uptake sites in rat brain measured by quantitative autoradiography. Synapse. 1992;11:287–293. doi: 10.1002/syn.890110404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdo TH, Katner SN, Taffe MA, Fox HS. Neuroimmunity, drugs of abuse, and neuroAIDS. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s11481-005-9001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral GA, Dove Pettit DA. Drugs and immunity: cannabinoids and their role in decreased resistance to infectious disease. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;83:116–123. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral GA, Marciano-Cabral F. Cannabinoid receptors in microglia of the central nervous system: immune functional relevance. J Leukoc. Biol. 2005;78:1192–1197. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral GA, Staab A. Effects on the immune system. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2005:385–423. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26573-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass WA. Decreases in evoked overflow of dopamine in rat striatum after neurotoxic doses of methamphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp. Ther. 1997;280:105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass WA, Harned ME, Peters LE, Nath A, Maragos WF. HIV-1 protein Tat potentiation of methamphetamine-induced decreases in evoked overflow of dopamine in the striatum of the rat. Brain Res. 2003;984:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Ernst T, Speck O, Grob CS. Additive effects of HIV and chronic methamphetamine use on brain metabolite abnormalities. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:361–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Ernst T, St HC, Conant K. Antiretroviral treatment alters relationship between MCP-1 and neurometabolites in HIV patients. Antivir. Ther. 2004;9:431–440. doi: 10.1177/135965350400900302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CC, Hu S, Shark KB, Sheng WS, Gekker G, Peterson PK. Activation of mu opioid receptors inhibits microglial cell chemotaxis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;281:998–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Hubner W, Riviere K, Liu YX, Chen BK. Chimeric HIV-1 containing SIV matrix exhibit enhanced assembly in murine cells and replicate in a cell-type-dependent manner in human T cells. Virology. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang RY, Suzuki S, Chuang TK, Miyagi T, Chuang LF, Doi RH. Opioids and the progression of simian AIDS. Front Biosci. 2005;10:1666–1677. doi: 10.2741/1651. 1666–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant K, Garzino-Demo A, Nath A, McArthur JC, Halliday W, Power C, Gallo RC, Major EO. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in HIV-1 Tat-stimulated astrocytes and elevation in AIDS dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:3117–3121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant K, St HC, Anderson C, Galey D, Wang J, Nath A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat and methamphetamine affect the release and activation of matrix-degrading proteinases. J. Neurovirol. 2004;10:21–28. doi: 10.1080/13550280490261699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha M, Graham NM, Munoz A, Vlahov D, Royal W, III, Updike M, Nance-Sproson T, Selnes OA, McArthur JC. Effect of chronic substance abuse on the neuropsychological performance of intravenous drug users with a high prevalence of HIV-1 seropositivity. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992;136:1338–1348. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Nixon K. Alcohol, neural stem cells, and adult neurogenesis. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxford JL. Therapeutic potential of cannabinoids in CNS disease. CNS. Drugs. 2003;17:179–202. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czub S, Czub M, Koutsilieri E, Sopper S, Villinger F, Muller JG, Stahl-Hennig C, Riederer P, ter MV, Gosztonyi G. Modulation of simian immunodeficiency virus neuropathology by dopaminergic drugs. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl) 2004;107:216–226. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0801-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czub S, Koutsilieri E, Sopper S, Czub M, Stahl-Hennig C, Muller JG, Pedersen V, Gsell W, Heeney JL, Gerlach M, Gosztonyi G, Riederer P, ter MV. Enhancement of central nervous system pathology in early simian immunodeficiency virus infection by dopaminergic drugs. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2001;101:85–91. doi: 10.1007/s004010000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ascenzo M, Piacentini R, Casalbore P, Budoni M, Pallini R, Azzena GB, Grassi C. Role of L-type Ca2+ channels in neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation. Eur. J Neurosci. 2006;23:935–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL, Syapin PJ. Chronic ethanol inhibits CXC chemokine ligand 10 production in human A172 astroglia and astroglial-mediated leukocyte chemotaxis. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;362:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR. HIV infection among intravenous drug users: epidemiology and risk reduction. AIDS. 1987;1:67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Choopanya K, Vanichseni S, Ward TP. International epidemiology of HIV and AIDS among injecting drug users. AIDS. 1992;6:1053–1068. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199210000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande M, Zheng J, Borgmann K, Persidsky R, Wu L, Schellpeper C, Ghorpade A. Role of activated astrocytes in neuronal damage: potential links to HIV-1-associated dementia. Neurotox. Res. 2005;7:183–192. doi: 10.1007/BF03036448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe RM. Multiple ways that drug abuse might influence AIDS progression: clues from a monkey model. J. Neuroimmunol. 2004;147:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe RM, Byrd LD, McClure HM, Fultz P, Brantley M, Marsteller F, Ansari AA, Wenzel D, Aceto M. Consequences of opiate-dependency in a monkey model of AIDS. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1993;335:21–28. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2980-4_4. 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Benveniste EN. Immune function of astrocytes. Glia. 2001;36:180–190. doi: 10.1002/glia.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer EB, Kaiser PK, Offermann JT, Lipton SA. HIV-1 coat protein neurotoxicity prevented by calcium channel antagonists. Science. 1990;248:364–367. doi: 10.1126/science.2326646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Malberg J, Nakagawa S. Regulation of adult neurogenesis by psychotropic drugs and stress. J Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;299:401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durvasula RS, Myers HF, Mason K, Hinkin C. Relationship between alcohol use/abuse, HIV infection and neuropsychological performance in African American men. J Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2006;28:383–404. doi: 10.1080/13803390590935408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisch AJ, Barrot M, Schad CA, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Opiates inhibit neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:7579–7584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120552597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage N, Gurwell JA, Singh IN, Knapp PE, Nath A, Hauser KF. Synergistic increases in intracellular Ca2+, and the release of MCP-1, RANTES, and IL-6 by astrocytes treated with opiates and HIV-1 Tat. Glia. 2005;50:91–106. doi: 10.1002/glia.20148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage N, Wu G, Ambati J, Bruce-Keller AJ, Knapp PE, Hauser KF. CCR2 mediates increases in glial activation caused by exposure to HIV-1 Tat and opiates. J Neuroimmunol. 2006a doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.05.027. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage N, Wu G, Wang J, Ambati J, Knapp PE, Reed JL, Bruce-Keller AJ, Hauser KF. HIV Tat1–72 and Opiate-induced changes in astrocytes promote chemotaxis of microglia through the expression of MCP-1 and alternative chemokines. Glia. 2006b;53:132–146. doi: 10.1002/glia.20262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Childers ME, Cherner M, Lazzaretto D, Letendre S, Grant I. Increased human immunodeficiency virus loads in active methamphetamine users are explained by reduced effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy. J Infect. Dis. 2003;188:1820–1826. doi: 10.1086/379894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emdad L, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Randolph A, Boukerche H, Valerie K, Fisher PB. Activation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway by astrocyte elevated gene-1: implications for tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1509–1516. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everall I, Salaria S, Roberts E, Corbeil J, Sasik R, Fox H, Grant I, Masliah E. Methamphetamine stimulates interferon inducible genes in HIV infected brain. J Neuroimmunol. 2005a;170:158–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everall IP, Bell C, Mallory M, Langford D, Adame A, Rockestein E, Masliah E. Lithium ameliorates HIV-gp120-mediated neurotoxicity. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2002;21:493–501. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everall IP, Hansen LA, Masliah E. The shifting patterns of HIV encephalitis neuropathology. Neurotox. Res. 2005b;8:51–62. doi: 10.1007/BF03033819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everall IP, Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Atkinson JH, Grant I, Mallory M, Masliah E. Cortical synaptic density is reduced in mild to moderate human immunodeficiency virus neurocognitive disorder. HNRC Group. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Acheampong E, Dave R, Wang F, Mukhtar M, Pomerantz RJ. The RNA helicase DDX1 is involved in restricted HIV-1 Rev function in human astrocytes. Virology. 2005;336:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber K, Pannasch U, Kettenmann H. Dopamine and noradrenaline control distinct functions in rodent microglial cells. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2005;29:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]