Abstract

Background

Patients with end-stage renal disease have high mortality and symptom burden. Past studies demonstrated that nephrologists do not feel prepared to care for their patients at the end of life (EOL). We sought to characterize current palliative and EOL care education received during nephrology fellowship and compare this to data from 2003.

Study Design

Cross-sectional online survey of second year nephrology trainees. Responses were compared to a similar survey in 2003.

Setting & Participants

104 US nephrology fellowship programs in 2013.

Measurements

Quality of training in and attitudes toward EOL care, and knowledge and preparedness to provide nephrology-specific EOL care.

Results

Of the 204 fellows included for analysis (response rate, 65%), significantly more thought it was moderately to very important to learn to provide care at EOL in 2013 compared to 2003 (95% vs. 54%; p<0.001). Nearly all (99%) fellows in both surveys believed physicians have a responsibility to help patients at EOL. Ranking of teaching quality during fellowship in all areas (mean, 4.1 ± 0.8 on a scale of 0-5 [0, poor; 5, excellent) and specific to EOL care (mean, 2.4 ± 1.1) was unchanged from 2003, but knowledge of the annual gross mortality rate for dialysis patients was nominally worse in 2013, as only 57% vs. 67% in 2003 answered correctly (p=0.05). To an open-ended question asking what would most improve fellows’ EOL care education, the most common response was a required palliative medicine rotation during fellowship.

Limitations

Assessments were based on fellows’ subjective perceptions.

Conclusions

Nephrology fellows increasingly believe they should learn to provide EOL care during fellowship. However, perceptions about the quality of this teaching have not improved during the past decade. Palliative care training should be integrated into nephrology fellowship curricula.

Keywords: nephrology fellowship, medical training, palliative care, end-of-life, dialysis withdrawal, hospice, dialysis, geriatrics, pain management, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), medical education, competency, survey

Older adults are the fastest growing population with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States. From 2000 to 2010, the adjusted incidence rate of ESRD for patients aged 75 or older rose 12.2% to 1,773 per million population1. The mortality rate of older patients with ESRD exceeds that of aged-matched Medicare patients with heart failure or cancer1. Observational data suggest that in older patients with a high burden of comorbidity, dialysis does not increase survival2, and is associated with functional decline of older nursing home patients3. However, dialysis patients are more likely to receive aggressive medical interventions in the last month of life and to die in a hospital than patients with cancer or heart failure4, despite the fact that most prefer to die at home or in an inpatient hospice5.

These data suggest that patients are unprepared for the end of life experience. One likely contribution is the fact that nephrologists feel unprepared to care for their patients at the end of life6. The quality of education during medical training has been noted to have an effect on reported competencies in practice7. In 2003, US nephrology fellows reported receiving little training in end-of-life (EOL) care issues relevant to nephrology and feeling less prepared to manage dialysis patients at the end of life compared to other nephrology practice skills8. Since 2003, the importance of palliative medicine to dialysis patient care is increasingly recognized9-11. Palliative medicine is now a board-certified internal medicine subspecialty. Incorporating palliative medicine into the care of chronically or seriously ill patients improves quantity and quality of life, and decreases associated healthcare costs12-15.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether advances in palliative medicine over the past decade are reflected in current second-year nephrology fellowship trainees’ knowledge and preparedness in nephrology EOL issues. We surveyed senior nephrology fellows in 2013 to assess for changes in education received in palliative and EOL care, their perceived preparedness to guide their patients at EOL, and their attitudes towards palliative and EOL care. Because dialysis patients continue to experience high rates of hospitalization and use of intensive procedures in the final month of life4,11, we hypothesized that training in palliative and EOL care has not improved since fellows were last surveyed in 2003.

METHODS

Survey Overview

From January through April 2013, an electronic online survey about palliative and EOL care training and experience was sent to second-year nephrology fellows in the United States (Item S1, available as online supplementary material). We chose to specifically survey second-year fellows to be able to compare responses with those in the original survey and to target fellows who had completed most of their clinical training. This study is based on a 2003 survey (Item S2) of nephrology fellows that was rigorously developed to assure content validity8. The present survey tool was modified to shorten the survey and to make it more contemporary (see “Survey Content” below). Changes to the 2003 survey were iteratively piloted on approximately 10 nephrology fellows and faculty to test for understandability and face validity prior to administration.

Identification of Potential Respondents

An accurate list of nephrology fellows enrolled in accredited adult nephrology fellowships in the United States is no longer available from the American Medical Association as it was in 20028; therefore, fellows’ email addresses were obtained through multiple modalities. First, the project was presented to and received approval from the American Society of Nephrology Training Program Directors Executive Subcommittee. Thereafter, nephrology fellowship directors were contacted via email asking for names and email addresses of their current second-year fellows. Those directors who did not respond received a letter from a member of the Executive Subcommittee asking for their assistance in obtaining fellows’ contact information. The authors of this manuscript and some faculty from the institution of one of the authors (S.C.) also directly contacted fellowship directors for their fellows’ contact information. Fellows’ email contact information was supplemented through information available on nephrology division websites. Of the 147 US programs listed on the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) website, we were able to verify 100% of the fellows at 104 of the programs (71%). Only fellows whose names and email addresses were verified through the program directors or their division website were included in the survey (n=326). The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board granted exempt status to this study under category 2 (research involving the use of educational survey procedures).

Survey Content

The survey queried fellows about their attitudes, amount of training received, and knowledge of nephrology-related palliative and EOL issues. We compared training and clinical experience obtained in performing kidney biopsies and conducting family meetings about EOL issues by asking fellows how many times they had conducted and were supervised during these two activities. The survey asked fellows to rate their preparedness in managing three clinical scenarios: a patient on hemodialysis therapy, a patient at the end of life, and a patient with distal renal tubular acidosis (RTA).

Hemodialysis and distal RTA were chosen because they represent very common and uncommon nephrologic clinical problems, respectively. Questions also asked whether fellows had been explicitly taught to manage common palliative nephrology clinical scenarios, such as how to assess and manage pain in dialysis patients, how to determine when it is appropriate to refer patients to palliative care or hospice, and how to respond to a patient’s request to stop dialysis. Demographic data included questions about plans for future practice, previous professional experience with palliative medicine services, and medical training, as well as gender, age, and religion. Survey response scales were varied: many were in the form of “yes”, “no”, or “other”; some were in “fill in the blank” format; others used a 4- to 5-point Likert scale of “poor” to “excellent” or similar; and the remaining were in a 5- or 10-point ordinal scale. Items modified from the 2003 survey included deletion of questions about clinical practices or attitudes of attending physicians, questions asking fellows to reflect on the most recent death occurring in the hospital, and deletion or changes in the specific nephrology palliative medicine scenarios. We chose to omit the questions about clinical practices and attitudes of attending physicians because pilot respondents found it difficult to classify all attendings’ attitudes into one succinct answer.

Survey Administration

We distributed a survey invitation via email using an online survey tool (SurveyMonkey), with a link to the confidential survey. After the initial invitation to join the survey, fellows who had not responded received up to 5 electronic reminders, each 3-6 weeks apart. Those who completed the survey at the fifth or sixth electronic reminder were offered a $5 electronic Starbucks gift card as an incentive. The incentive was only offered to those fellows who failed to respond to earlier requests. The last survey was completed in April 2013. Data were collected anonymously through SurveyMonkey’s website and exported for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL) statistical software. Descriptive statistics (sample means and distributions) were used to summarize the data obtained. Pearson Chi-Square analysis was used to form comparisons between proportions at times 1 (2003) and 2 (2013). Repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare means of ordinal scale answers measured at time 2, and then pairwise comparisons further characterized differences between each mean. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Respondent Demographics

Table 1 depicts characteristics of the study groups in 2003 and 2013 (full results from the 2013 survey are provided as Table S1). In 2013, a total of 326 fellows were identified and surveyed, 211 responded (response rate, 65%), and 204 were included for analysis. The 7 subjects excluded from analysis self-reported themselves as first- or third-year fellows. Twenty-six fellows (12% of respondents) responded after the financial incentive was offered. The original 2003 survey had a 63% response rate. Forty-three percent of fellows in 2013 were women (compared to 32% in 2003; p = 0.04), and 61% were foreign medical graduates (17% in 2003; p <0.001). In 2013 the predominant ethnicity, religion, and average age were Asian (39.5%), Hindu (25.5%), and 33 years, respectively.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents in 2003 and 2013.

| 2003 | 2013 | p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total no. analyzed | 173 | 204 | |

|

| |||

| Male sex | 68 | 57 | 0.04 |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | 0.4 | ||

| White | 46 | 35 | |

| Asian | 35 | 40 | |

| Hispanic | 5 | 6 | |

| Black | 4 | 4 | |

| Native American/Alaskan/Hawaiian | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Other | 12 | 15 | |

|

| |||

| Age | -- | ||

| Mean (y) | NA | 33 | |

| Range (y) | 27-49 | 28-48 | |

|

| |||

| Religion | 0.007 | ||

| Catholic | 24 | 22 | |

| None | 17 | 10 | |

| Hindu | 16 | 26 | |

| Protestant | 14 | 9.2 | |

| Muslim | 10 | 16 | |

| Jewish | 10 | 4.3 | |

| Other | 9 | 13 | |

|

| |||

| Did not attend US Medical School | 17 | 61† | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Plans After Fellowship | 0.003 | ||

| Clinical Academic Medicine | 15 | 19 | |

| Private Practice | 48 | 38 | |

| Basic Research Academic | 8 | 2.7 | |

| Clinical Research Academic | 7 | 11 | |

| Mix of Academic and Private | 17 | 16 | |

| Undecided | 0 | 10 | |

| Other | 5 | 3.8 | |

Note: Unless otherwise indicated, values are given as percentages.

NA, not available.

Slightly more than half of respondents (107 of 190 [56%]) characterized themselves as more inclined toward social and emotional rather than technological and scientific aspects of medical care, vs. 125 of 171 fellows (73%) self-characterizing as more inclined towards the technical aspects in 2003 (p < 0.001). Compared to 2003, significantly more men described themselves as being more inclined towards social and emotional aspects of patient care (49% vs. 20%; p<0.001), and in both surveys, women were more inclined toward social and emotional aspects of care (65% women vs. 49% men in 2013 [p = 0.03] and 43% women vs. 20% men in 2003 [p=0.002]).

Notably, the demographic background of nephrology fellows has dramatically shifted over the past ten years with nearly 61% having undergone medical school training outside the United States. After retrospectively observing this demographic statistic, we were curious to see how responses from international medical graduates differed from those respondents who completed medical education in the United States. Ten of twelve questions inquiring about attitudes, teaching, knowledge, and preparedness demonstrated no significant difference in responses between the two groups, suggesting that location of medical school does not significantly alter fellows’ perceptions of palliative and EOL care.

Attitudes Towards End-of-Life Care

Fellows’ attitudes towards caring for dying patients are summarized in Table 2. In 2013, 95% of respondents felt that it was moderately to very important to learn to provide care to dying patients, an increase compared to 2003 when 54% of fellows expressed this response (p < 0.001). In both 2003 and 2013, 99% of fellows generally or completely agreed with the statement that “physicians have a responsibility to help patients at the end of life prepare for death”.

Table 2. Fellows’ Attitudes Toward Caring for Dying Patients.

| 2003 | 2013 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| It is moderately/very important to learn to provide care to dying patients |

54% | 95% | <0.001 |

| Generally/completely agree that caring for dying patients is depressing. |

47% | 61% | 0.006 |

| Generally/completely agree that it is possible to tell patients the truth about a terminal prognosis and still maintain hope |

78% | 80% | 0.6 |

| Generally/completely agree that depression is treatable among patients with terminal illness |

84% | 84% | 0.9 |

| Generally/completely agree that physicians have a responsibility to help patients at the end of life prepare for death |

99% | 99% | 0.9 |

Teaching and Preparedness of Nephrology Fellows in Clinical Practice

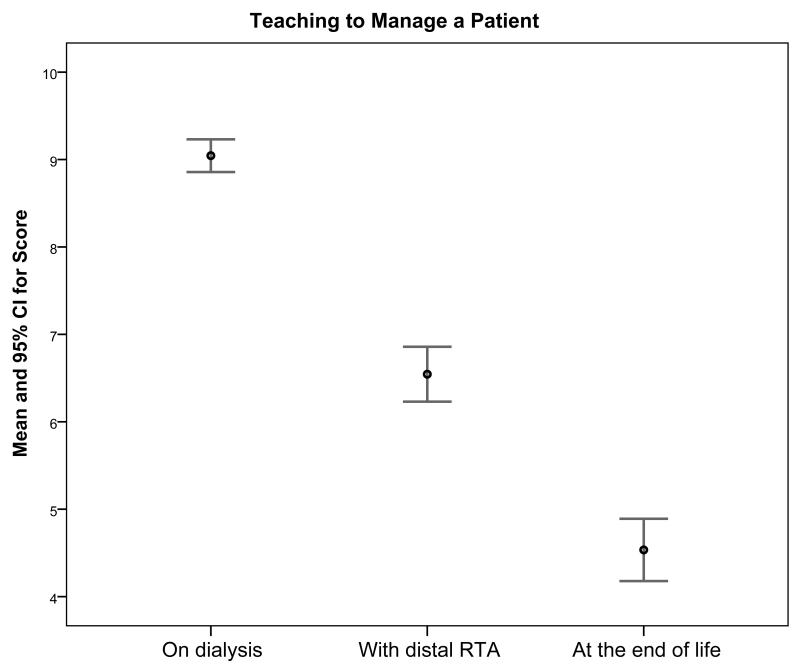

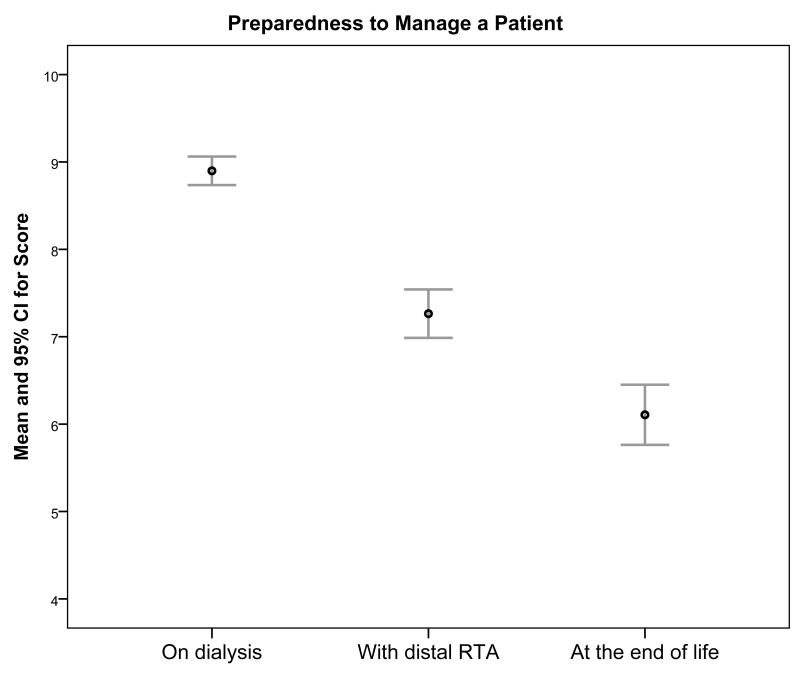

Figure 1 illustrates teaching received during fellowship and preparedness of fellows in 2013 to manage patients in three specific areas of clinical nephrology: on hemodialysis, with distal RTA, and at the end of life. By answering on a scale of 0-10 where 0 is “no teaching” or “completely unprepared” and 10 is “a lot of teaching” or “as prepared as you can be”, fellows reported significantly more teaching in managing a patient on dialysis than at the end of life, or with distal RTA (means of 9.04±1.4 [standard deviation], 4.5±2.5, and 6.5 ± 2.3, respectively; all p <0.001). Fellows’ self-assessment of preparedness to perform these clinical duties matched the ranking of teaching received (means of 8.9 ± 1.2, 6.1 ± 2.5, and 7.3 ± 2.0, respectively; all p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Teaching vs. preparedness to manage a patient in three areas of nephrology Legend: 0 = no teaching or completely unprepared, 10= a lot of teaching or completely prepared. RTA = renal tubular acidosis, CI = confidence interval. P <0.001 in 1a and 1b across means and between means using ANOVA and pairwise comparisons, respectively.

Only 5 fellows in 2013 reported completing a rotation focused on end-of-life care, hospice or palliative care during their fellowship. Sixty-one percent of fellows completed such a rotation during medical school or residency, and 80% reported having contact with clinicians who specialize in palliative care during fellowship. On a scale of 0 to 5, from poor to excellent, fellows ranked the quality of teaching during fellowship in all areas as a mean of 4.1, and teaching specifically about end-of-life care as 2.4. These rankings were nearly identical in 2003, with means of 4.0 and 2.3, respectively.

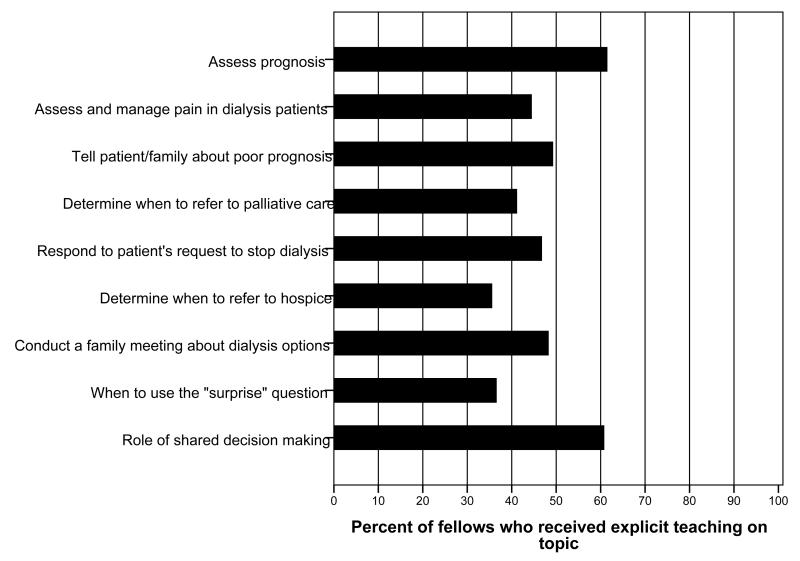

Figure 2 demonstrates teaching in specific palliative care content areas in nephrology. Most fellows in 2013 did not receive teaching in these topics; fewer than half were taught how to respond to a patient’s request to discontinue dialysis, assess and manage pain in dialysis patients, conduct a family meeting about dialysis options, or determine when to refer patients to palliative care or hospice. However, more fellows in 2013 than in 2003 (44% vs. 30%; p = 0.003) were explicitly taught how to treat dialysis patients’ pain.

Figure 2.

Content areas explicitly taught during fellowship

Experience in Caring for Patients

Most fellows (79% in 2003, 80% in 2013) had the opportunity to develop longitudinal relationships (continuous relationships lasting longer than 6 months) with dialysis patients during fellowship. Fellows reported caring for a mean of 16 dialysis patients who were in their last few weeks of life in 2013. Figure 3 compares current fellows’ experience in performing, performing while observed, and receiving feedback during a kidney biopsy (Fig 3a) and conducting a family meeting about goals of care for a terminally ill patient (Fig 3b). Most fellows had conducted a family meeting more than twice (72%); 25% reported never being observed during this task, and greater than half (51%) never received feedback about their performance during the meeting. The corresponding percentages in 2003 were 68%, 26%, and 30%, respectively. A lower percentage of fellows received feedback from any attending nephrologist about their conduct of a family meeting in 2013 (49%) than in 2003 (70%; p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Comparison of fellows’ reports of preceptorship while performing kidney biopsies vs. conducting family meetings Legend: 3a: number of fellows who responded: performed n=201, performed while observed n=201, feedback n=199. 3b: number of fellows who responded: performed n=199, performed while observed n=199, feedback n=201.

Fellows’ Knowledge of Dialysis Patients’ Mortality and Clinical Practice Guidelines

Fellows answered the multiple-choice question, “What is the annual gross mortality of patients on dialysis?” The correct answer is 20%-29%1. Nominally fewer fellows in 2013 than in 2003 answered the question correctly (57% vs. 67%; p = 0.05). Thirty-three percent of fellows in 2013 overestimated the mortality. Fellows also answered the question, “Are you aware of or have you ever reviewed the clinical practice guideline, ‘Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis?’” Nearly half answered “no” (90 of 194 [46%]), 16% said they had heard of it and had reviewed the guidelines, and 37% answered that they had heard of it but not reviewed the guidelines.

Suggestions for Improving End-of-Life Care Education During Fellowship

Fellows were asked an optional open-ended question: “In your opinion what one change would most improve end-of-life care education for fellows in Nephrology?” Of the 146 answers (response rate, 72%), the most common suggestion was to incorporate a palliative medicine rotation into fellowship curricula (29%), followed by formal didactics given by specialists in geriatric nephrology or palliative medicine specific to EOL issues (14%).

DISCUSSION

The results of this survey are consistent with our hypothesis that training specific to palliative and EOL care during nephrology fellowship has not increased in quantity or quality over the past decade. Despite this, nephrology trainees increasingly believe that learning how to provide this care to their patients is important. The data presented suggest that fellows’ preparedness to perform these clinical duties is associated with the amount of teaching received specifically in palliative and EOL care.

With advances in the treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, patients with chronic kidney disease and ESRD are living longer and often have multiple concurrent chronic illnesses. Many are likely to benefit from palliative and EOL care to help with decision-making regarding starting or stopping dialysis, with deciding on dialysis modality, in the treatment of pain or other symptoms, or in advance care planning. As described by Quill and Abernethy16, the number of chronically or seriously ill patients needing palliative care services is too numerous to be cared for by palliative medicine specialists. Quill and Abernethy urged all medical providers to learn skills in basic, or primary, palliative care specific to their field and refer to specialist palliative care for more complex issues. Competence in these clinical skills, even at the primary palliative care level, requires formal education. Unfortunately, our study suggests that many nephrology fellowships are failing in the task of preparing their trainees to provide this care.

The ACGME currently requires that nephrology fellows receive supervised “clinical experience in EOL care and pain management in the care of patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis”17. The fellows surveyed reported that they would prefer to learn this material in two ways: rotating or working with providers skilled in providing palliative and EOL care, and increased didactics and/or grand rounds dedicated to topics in palliative and EOL care in nephrology. Fortunately, there are multiple didactic resources for trainees. Oncotalk18 and Nephrotalk19 have demonstrated success in improving fellows’ communication skills by teaching and practicing basic palliative care skills under direct supervision. Additionally, the American Society of Nephrology has a free online curricula dedicated to geriatric nephrology with subtopics pertinent to EOL and palliative care20. Likewise, the Renal Physicians Association published an updated clinical practice guideline in 2010 on shared-decision-making in dialysis initiation and withdrawal that provides explicit, evidence-based suggestions on how to improve palliative care for dialysis patients and approach these difficult scenarios9.

The major limitation of this study is that the results rely on participants’ self-reports of attitudes, beliefs, and perceived preparedness, therefore introducing susceptibility to self-report bias. Quantity and quality of teaching are not directly assessed but depend on fellows’ retrospective grading of their experiences. Likewise, fellows self-evaluated their preparedness to perform clinical tasks and they may over or underestimate their abilities21. However, studies suggest that physicians’ clinical competency may be correctly evaluated via indirect assessments22. Another limitation is that we did not have all of the raw data from the original survey in 2003 and were limited to survey results included in the results section and the figures. Therefore, we were unable to perform some comparisons between 2003 and 2013 data. Moreover, as the 2013 survey is a modified version of the rigorously validated 2003 survey, the 2013 survey was validated according to face validity alone, which is another potential study limitation.

More research is necessary to determine how best to incorporate these topics into nephrology and fellowship curricula. Until then, fellowship programs have many established tools to utilize for their own individual programs. The results of this survey clearly emphasize that nephrology fellows simultaneously lack training in palliative and end-of-life care and greatly desire to become more proficient in this area of clinical nephrology. The increasingly elderly and ill dialysis population along with an emerging recognition of the importance of palliative care led the nephrology community to include a shared decision-making process about initiatinging dialysis as a focus of the Choosing Wisely campaign23. The onus is on nephrology fellowships to train future nephrologists to be competent in nephrology-related palliative and EOL care. This study’s findings may also motivate other medicine subspecialties to heed the call to integrate palliative care into the standard of care for their patients, much the way oncology has done24.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Robert M. Arnold, MD, and co-investigators from the 2003 survey of nephrology fellows for permission to use questions in this study. We also express our sincerest gratitude to Tomas Berl, MD, for his invaluable contributions and to Stu Linas, MD, and Richard Johnson, MD, for their support of this project. Dr Combs thanks J. Pedro Teixeira, MD, for his assistance in manuscript preparation.

Support: Education support provided by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Institute (grant UL1 TR001082).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: SAC, JH, AM; data acquisition: SAC, JH, AM; data analysis and interpretation: SAC, JH, SC, AM; statistical analysis: SC; supervision or mentorship: JH, DM, JK, AM. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. SAC takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: 2013 survey results.

Item S1: 2013 survey.

Item S2: 2003 survey.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_______) is available at www.ajkd.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Chavers B, et al. US Renal Data System 2013 annual data report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63((1)(suppl 1)):e1–e420. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE. Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2007 Jul;22(7):1955–1962. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Oct 15;361(16):1539–1547. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM. Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Archives of internal medicine. 2012 Apr 23;172(8):661–663. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.268. discussion 663-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2010 Feb;5(2):195–204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Holley JL, Moss AH. Nephrologists’ reported preparedness for end-of-life decision-making. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2006 Nov;1(6):1256–1262. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02040606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamesh L, Clapham M, Foggensteiner L. Developing a higher specialist training programme in renal medicine in the era of competence-based training. Clin Med. 2012 Aug;12(4):338–341. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-4-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holley JL, Carmody SS, Moss AH, et al. The need for end-of-life care training in nephrology: national survey results of nephrology fellows. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2003 Oct;42(4):813–820. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis. 2 nd ed Renal Physicians Association; Rockville, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers E, Brown EA, Germain MJ. Supportive Care for the Renal Patient. 2nd ed Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davison SN. The ethics of end-of-life care for patients with ESRD. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2012 Dec;7(12):2049–2057. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03900412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011 Mar;30(3):454–463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Aug 19;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. Journal of palliative medicine. 2008 Mar;11(2):180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penrod JD, Deb P, Dellenbaugh C, et al. Hospital-based palliative care consultation: effects on hospital cost. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010 Aug;13(8):973–979. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Mar 28;368(13):1173–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [on 24 March 2014];ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Nephrology (Internal Medicine) :21. Accessed at http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/2013-PR-FAQ-PIF/148_nephrology_int_med_07132013.pdf.

- 18.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Faculty development to change the paradigm of communication skills teaching in oncology. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009 Mar 1;27(7):1137–1141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schell JO, Green JA, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. Communication skills training for dialysis decision-making and end-of-life care in nephrology. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013 Apr;8(4):675–680. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05220512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Society of Nephrology Online Curricula [on 24 March 2014];Geriatric Nephrology. Accessed at http://www.asn-online.org/education/distancelearning/curricula/geriatrics/

- 21.Hodges B, Regehr G, Martin D. Difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence: novice physicians who are unskilled and unaware of it. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2001 Oct;76(10 Suppl):S87–89. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200110001-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, et al. Measuring the quality of physician practice by using clinical vignettes: a prospective validation study. Annals of internal medicine. 2004 Nov 16;141(10):771–780. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. [on 24 March 2014];American Society of Nephrology. Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. Accessed at http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-society-of-nephrology/

- 24.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Mar 10;30(8):880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.