Abstract

The deleterious effects of racism on a wide range of health outcomes, including HIV risk, is well documented among racial/ethnic minority groups in the United States. However, little is known about how men of color who have sex with men (MSM) cope with stress from racism and whether the coping strategies they employ buffer against the impact of racism on sexual risk for HIV transmission. We examined associations of stress and coping with racism with unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) in a sample of African American (n = 403), Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 393), and Latino (n = 400) MSM recruited in Los Angeles County, CA during 2008–2009. Almost two-thirds (65%) of the sample reported being stressed as a consequence of racism experienced within the gay community. Overall, 51% of the sample reported having UAI in the prior six months. After controlling for race/ethnicity, age, nativity, marital status, sexual orientation, education, HIV serostatus, and lifetime history of incarceration, the multivariate analysis found statistically significant main effects of stress from racism and avoidance coping on UAI; no statistically significant main effects of dismissal, education/confrontation, and social-support seeking were observed. None of the interactions of stress with the four coping measures were statistically significant. Although stress from racism within the gay community increased the likelihood of engaging in UAI among MSM of color, we found little evidence that coping responses to racism buffered stress from racism. Instead, avoidance coping appears to suggest an increase in UAI.

Keywords: sexual orientation, men who have sex with men, Stress, Coping, HIV risk

INTRODUCTION

The link between race, racism, and negative health outcomes has been well established in the academic literature (Brondolo, Gallo, & Myers, 2009; Shaver & Shaver, 2006; Sondik et al., 2010; William, 2006; Williams et al., 2010). Although much of the health disparities between Whites and people of color can be explained by differences in socioeconomic status as manifested in differences in life-styles, health-seeking behaviors, and differential access to care, racism continues to exert an independent influence on health outcomes (Williams, 2006). One meta-analysis of 138 quantitative population-based studies demonstrated a strong association between racism and ill health, even after adjusting for a range of confounders (Paradies, 2006). While the strongest correlations were between experiences of racism and mental health, various studies have found a link between experiences of racism and physical health as well (Gee & Ford, 2011; Paradies, 2006; Williams et al., 2010). Given the effects of racism on health, even when controlling for other potential factors, many scholars have argued that racism is a unique source of stress that may lead to negative health outcomes for members of minority groups (Harrell, 2000; Mays et al., 2007; Thompson, 2002; Williams et al., 2003).

Although there are many potential sources of stress, racism has been demonstrated to be a major source of stress for people of color (Dion, 2002; Thompson, 2002). In fact, even minor instances of racial discrimination may lead to heavy psychological costs when they recur often and are persistent over time (Huynh, Devos, & Dunbar, 2012). Recently, a number of scholars have examined how minority stress, the stress associated with being a member of a marginalized group, can negatively impact health outcomes (Balsam et al., 2011; Friedman, Williams, Singer, & Ryff, 2009; Szymanski & Sung, 2010; Zambino & Crawford, 2007). Within the health literature, minority stress is understood as “the excess stress to which individuals from stigmatized categories are exposed as a result of their social, often a minority, position” (Meyer, 2003, p. 675). For MSM of color, minority stress can take a number of forms, including homophobia in communities of color and racism from the mainstream gay community, which may cause them to experience a number of unique stressors and force them to cope with their doubly marginalized status. Minority stress may be even more detrimental given that status-based rejection, particularly those based on race, has been demonstrated to members of rejected groups to “anxiously expect, readily perceive, and intensely react” to rejection based on their minority status as well as negatively influence their personal and interpersonal experiences with others (Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002). In this article, we examined ways that men of color who have sex with men (MSM of color) cope with the stress caused by racism directed toward them from gay White men in the mainstream gay community in order to discern whether coping with racism helps to buffer the impact of racism-related stress on HIV risk among members of this group.

Current research demonstrates that MSM of color experience widespread racism in the mainstream gay community (Ayala et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2013; Giwa & Greensmith, 2012; Han, 2008; Ibanes et al., 2009; Ichard, 1985; Kraft et al., 2000; Raymond & McFarland, 2009; Seal et al., 2000; Woolwine, 2008; Zamboni & Crawford, 2007). In a previous study, we found that 70 percent of 1196 participants reported experiencing racism in the gay community while only 57 percent reported experiencing racism within the general community (Choi et al., 2013). Latino men, especially those with darker features, report high rates of racial discrimination from gay White men (Ibanes et al., 2009). Among gay African American men, many report high rates of discrimination at gay bars, night clubs, and other social settings, as well as report feeling marginalized and unaccepted in the gay community (Ichard, 1985; Kraft et al., 2000). As high as these numbers are, the true percentage of MSM of color who experience racism may be even higher as stigmatized people may avoid attributing negative treatment to discrimination due to high negative costs of making such claims (Kaiser & Miller, 2001, 2003). In fact, Czopp and Monteith (2003) demonstrated that members of dominant groups often do respond negatively to claims of racism or sexism by members of minority groups, adding more credence to Kaiser and Miller’s findings.

Among MSM of color, experiences of racism in the mainstream gay community have been demonstrated to lead to a variety of negative health outcomes. For example, Chae and Yoshikawa (2008) found that devaluation in the gay community, due to sexual rejection from White men, leads to higher levels of depression and unsafe sex among gay Asian men. Social discrimination due to race led to higher rates of psychological distress among gay and bisexual Latino men (Diaz et al., 2001). Similarly, experiences of racism in the gay community have been linked to various sexual problems and dysfunctions, such as infrequency of sex, finding suitable sex partners, maintaining affection for a sex partner, guilt about sexual behaviors, problems with arousal, premature ejaculation, and lack of orgasm among gay and bisexual African American men (Zamboni & Crawford, 2007). In addition, several scholars have noted the connection between racism and HIV risk behaviors among gay men of color (Diaz, Ayala, & Bein, 2004; Han, 2008; Raymond & McFarland, 2009).

Given the impact of racism on health outcomes, a number of scholars have examined the role that coping with racism can play in buffering against the negative impacts that such experiences might have on health outcomes (Barnes & Lightsey, 2005; Brondolo et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2011; Mellor, 2004; Noh & Kaspar, 2003; Plummer & Slane, 1996; Wei et al., 2010; West, Donovan, & Roemer, 2010). Because racism can manifest in a number of ways, different coping strategies may be utilized to deal with racism-related stress. While external stressors can be readily identified, to understand how individuals cope with such experiences one must view stress as situated within the relationship that individuals have with their environment rather than intrinsic to a specific external event (Lazarus, 1991). Stress is experienced when individuals perceive that they cannot adequately cope with the demands of an external situation and perceive those demands as threatening to their well-being (Lazarus, 1966; Lazarus & Folkman, 1986). When a potential threat is encountered, an individual attempts to appraise the situation in three ways. Primary appraisal involves the individual making a judgment regarding the potential and/or immediate threat posed by a situation. Secondary appraisal involves exploring potential coping options that are available with deal with the threat. Finally, individuals engage in an ongoing process of reappraisal, re-evaluating their primary and secondary appraisals as the situation evolves. These appraisals of potential threats may lead individuals to engage in various coping behaviors or “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing the resources of the person” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 141). Coping can, therefore, be understood as a process whereby individuals attempt to minimize the impact of a stressful situation, to avoid or ignore the source of stress, and/or to change the stressful situation (Lyon, 2012). In addition, when coping with stress based on minority status, how individuals appraise the cost and benefits of confronting discrimination may influence how they cope with the source of stress (Kaiser & Miller, 2004).

Stress and Coping with Racism

Categorizations of strategies employed in coping efforts have emerged in the field. In his original work, Lazarus (1966) identified two broad types of coping, direct-action and palliative, which were later renamed as problem-focused and emotion-focused coping (Lazarus & Folkman 1984). Problem-focused coping strategies can involve any action that involves attempts to eliminate the source of stress, confront the source of stress, or change the source of stress. Emotion-focused coping strategies can involve attempting to manage or alleviate the emotional consequences of the stressful event, such as support seeking. As Folkman and Lazarus (1985) noted, it is likely that people use both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies when dealing with stress. Billings and Moos (1984) suggested a third type, called avoidance coping, which can involve attempts to forget the stressful situation or avoid potential sources of stress. In a subsequent study, Mellor (2004) applied Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) concepts of social support seeking and positive reinterpretation to examine the ways that members of a racial minority group cope with the stress associated with racism.

Efforts to examine the utility of various coping strategies in dealing with racism have found mixed results. West, Donovan, and Roemer (2010) found that high levels of problem-solving coping helped to lessen the impact of racism while avoidant coping strategies may exacerbate the effects of racism among African American women. However, some scholars have found limited benefits to coping when dealing with racism. For example, Barnes and Lightsey (2005) found that both avoidance coping and problem-solving coping did little to moderate the stress caused by racial discrimination.

Research examining coping among MSM of color has been more limited, primarily a few small studies using qualitative in-depth interviews to explore the ways that gay and/or bisexual men of color cope with racism and/or homophobia (Choi et al., 2011; Han, 2009; Poon & Ho, 2008; Wilson & Yoshikawa, 2004). Choi et al. identified four different coping strategies used by MSM of color to deal with racism from gay white men. When confronted with discriminatory behaviors from gay white men, Choi et al. found that MSM of color attempted to disassociate from larger social settings where they may experience racism, dismiss the racism, draw strength from external sources, or directly confront the source of racism. Working with Asian men, Wilson and Yoshikawa (2004) found that gay Asian men use both confrontational and non-confrontational strategies to deal with racism from gay white men. Poon and Ho (2008) found that gay Asian men reframed the stigma associated with being Asian in the gay community on an interpersonal level by attributing racist acts by gay White men as personal failings of some gay White men rather than on their own physical shortcomings.

Given the theorized connection between experiences of racism and HIV risk behaviors among MSM of color, it is surprising that there has been little investigation as to whether such coping strategies help to mitigate HIV risk through buffering the impact of racism-related stress. Currently, we are aware of only one study that examined the moderating effect of coping strategies on the relationship between experienced stress and sexual risk behaviors among self-identified gay and bisexual men in the U.S. (Martin and Alessi, 2010). However, that study sampled mostly White men and examined only one type of coping strategy (avoidance coping). More importantly, Martin and Alessi (2010) examined general stress rather than racism-related stress. The present study attempted to address the gap in the literature by identifying various coping strategies utilized by African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino MSM and examining whether these coping strategies buffered against the impact of stress from racism on the sexual risk for HIV among these men. We also examined whether these relationships varued by race/ethnicity.

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

Participants for this study were recruited between May 2008 and October 2009 as part of the Ethnic Minority Men’s Health Study in order to examine the influences of social discrimination, social networks, and sexual partnership on HIV risk behaviors among African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Latino MSM in Los Angeles, California. Our target population was relatively hidden and difficult to reach due to being a stigmatized sexual minority group; thus, participants were recruited using a chain-referral sampling method. This sampling method began with recruiting “seed” participants through referrals from project staff at AIDS Project Los Angeles and through outreach activities at various venues popular with MSM, such as bars, dance clubs, and coffee shops located in gay-identified neighborhoods. Eligibility for participation in the study entailed: (1) self-identification as African American, Asian, Pacific Islander, or Latino; (2) being at least 18 years old; (3) residence in Los Angeles County; (4) sexual intercourse with at least one man in the last six months; and (5) not having participated in the initial phase of the study that involved qualitative interviews and survey instrument pretesting.

Eligible seed participants were provided with written informed consent and then completed a one-hour, standardized questionnaire using audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) technology. Upon completion, each seed participant received $50 as compensation and was provided with three “recruitment coupons” and invited to recruit other MSM friends or acquaintances for the study. Seed participants were informed that they would receive $10 for each participant whom they referred and who presented with a valid coupon.

Potential participants who were recruited by the seed participants contacted study staff by telephone and were screened for eligibility. If eligible, they were scheduled to complete the study protocol at the project site. Once new participants completed the ACASI-based survey, they were also provided with three recruitment coupons and invited to recruit other MSM for the project. This recruitment and enrollment process continued until we reached our target sample size of approximately 400 participants for each racial group.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Participants were asked about their race/ethnicity, age, level of education, nativity, sexual orientation, marital status, any lifetime history of incarceration, and HIV serostatus.

Stress from racism in the gay community

We measured stress from racism in the gay community with a three-category index: (1) “never experienced such racism”; (2) “not stressed when experienced such racism”; and (3) “stressed when experienced such racism.” This stress measure was created based on responses to the following eight questions (see Appendix 1). The first seven questions asked about perceived racism within the mainstream gay community (e.g., I’ve felt white gay men have acted as if they’re better than me because of my race or ethnicity; I’ve felt ignored or invisible where white gay men hang out because of my race or ethnicity; I’ve been turned down for sex because of my race or ethnicity). For each question, the participants were asked to respond using a four-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree”). The last question asked, “Overall, when you have been treated differently based on your race/ethnicity, how stressful have these experiences been for you?” This question had four response options, ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“quite a bit”). The three categories for the “stress from gay community racism” measure were defined as: “never experienced racism” if participants reported either “somewhat” or “strongly” disagreeing with all of the seven statements about perceived racism within the gay community; “not stressed when experienced racism” if participants reported either “somewhat” or “strongly” agreeing with any of the seven statements about perceived racism within the gay community and also reported “not at all” stressed when they had experienced racism within the gay community; and “stressed when experienced racism” if participants reported either “somewhat” or “strongly” agreeing with any of the seven statements about perceived racism within the gay community and also reported being “somewhat,” “a moderate amount,” or “quite a bit” stressed when they experienced racism within the gay community.

Coping with racism

Coping with racism was measured using 9 candidate items that were developed based on qualitative data collected from six focus groups (n = 50) and 35 individual in-depth interviews from the previous phase of this study (see Choi et al., 2011). Responses to these items were made using a four ordered response options (1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree”). We identified four subscales among the 9 coping items via an exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation: avoidance (2 items; i.e., I stay away from places like West Hollywood to avoid others’ negative attitudes and treatment due to my race or ethnicity; A way I deal with others’ prejudice is by hanging out with persons of my race/ethnicity; alpha = 0.57); dismissal (2 items; i.e., When I hear others express racism or negative attitudes about [Asian/Pacific Islanders/African Americans/ Latinos], I just shrug it off; I keep my life private as a way to avoid others’ racism or negative attitudes about [Asians/Pacific Islanders/Blacks/Latinos]; alpha = 0.63); social support seeking (2 items; i.e., I talk with friends to deal with racism and negative attitudes toward [Asian/Pacific Islanders/African Americans/ Latinos] that I encounter; When I feel treated unfairly or discriminated against because of being [Asian/Pacific Islander/Black/Latino], there are family members I can rely on to be there for me; alpha = 0.68); and education/confrontation (3 items; i.e., When others express racist attitudes or prejudices toward others of different ethnicities, I try to educate them; If I’m treated unfairly or disrespectfully due to my race/ethnicity, I speak up and challenge the person’s actions or beliefs; When people get to know me as a person, it changes their prejudices or judgments about my race/ethnicity; alpha = 0.70). Response scores were averaged to create the four coping subscales, each of with a possible range from 1 to 4.

Sexual risk

Sexual risk was defined as having any unprotected anal intercourse with a male partner in the past six months. This variable was created by using partner-by-partner data on participants’ sexual behavior during the prior six months (up to their 10 most recent sexual partners). For each partner, questions included biological sex and counts of anal and vaginal sex episodes and condom use during these episodes.

Statistical Analysis

We used GEE logistic regression with participants clustered within recruitment seeds. Bivariate and multivariate models of the UAI outcome were fit. The initial multivariate model included all explanatory variables and three-way interactions between stress, ethnicity, and each of the coping measures. The final multivariate model was the result of a backward elimination process that removed main effects with p > .20 and interactions with p >.05. All regression models were fit to 40 imputed data sets. Imputation used a fully conditional specification, also known as chained equations, which is well suited to imputation of non-normal data (van Buuren, 2007). All parameter estimates and significance tests were calculated by combining results across the imputed data sets (Rubin, 1987; Schafer, 1997).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

As Table 1 shows, the demographic profile of the sample differed by race/ethnicity. African Americans tended to be older than Asians/Pacific Islanders and Latinos. Asians/Pacific Islanders were more likely to have a college degree than were African Americans and Latinos. African Americans were more likely to be U.S.-born than were Asians/Pacific Islanders and Latinos. African Americans were more likely to self-identify as bisexual and to have ever been married to a woman than were Asians/Pacific Islanders and Latinos. African Americans and Latinos were more likely to have a lifetime history of incarceration than were Asians/Pacific Islanders. African Americans and Latinos were more likely to be HIV-positive than were Asians/Pacific Islanders. In regard to sexual risk, we found no significant racial/ethnic difference in unprotected anal intercourse in the prior six months.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, by Race/Ethnicity

| Characteristics | African American (N=403) | API (N=393) | Latino (N=400) | Overall (N=1196) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean in years; range: 18–83)*** | 41 | 33 | 35 | (36) |

| Education (%)*** | ||||

| Less than high school diploma | 14 | 4 | 22 | 13 |

| High school diploma or GED | 37 | 13 | 27 | 26 |

| Some college education | 35 | 23 | 29 | 29 |

| College graduate | 14 | 60 | 21 | 32 |

| Nativity (%)*** | ||||

| U.S. born | 94 | 43 | 61 | 66 |

| Foreign born | 6 | 57 | 39 | 34 |

| Sexual orientation (%)*** | ||||

| Gay | 60 | 86 | 77 | 74 |

| Bisexual | 27 | 11 | 17 | 19 |

| Other | 13 | 3 | 6 | 7 |

| Ever married to a woman (%)*** | 26 | 9 | 15 | 17 |

| Lifetime incarceration history*** | 41 | 13 | 35 | 29 |

| Self-reported HIV serotatus (%)*** | ||||

| Positive | 51 | 14 | 44 | 36 |

| Negative | 49 | 86 | 56 | 64 |

| Unprotected anal intercourse in the past six months | 46 | 57 | 51 | 51 |

p < .001

Stress and Coping with Racism

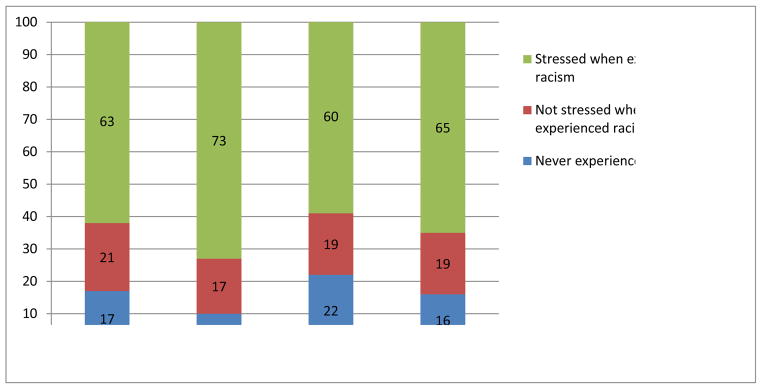

Overall, 16% of the sample reported not experiencing racism within the gay community, 19% reported experiencing racism within the gay community but not being stressed about it, and 65% reported being stressed as a consequence of racism experienced within the gay community. As Fig. 1 shows, the prevalence of stress from racism differed by race/ethnicity. Asian/Pacific Islanders were most likely to report being stressed (73% vs. 63% African Americans and 60% Latinos; p <.001)--apparently linked to a higher prevalence of reporting any such experiences of racism.

Figure 1.

Stress from Racism Experienced in the Gay Community, by Race/Ethnicity (%)

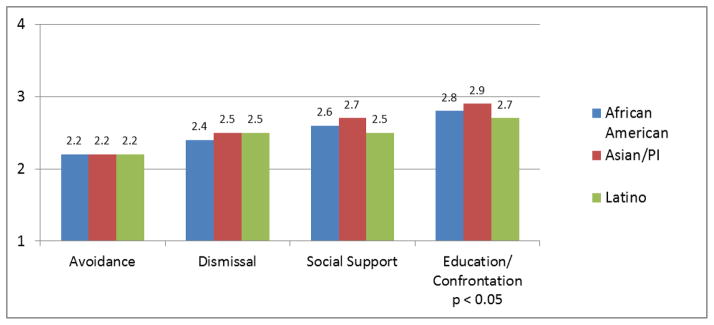

Figure 2 shows the racial/ethnic breakdowns of coping strategies reported by participants. There were no significant racial/ethnic differences in use of active avoidance, dismissal, and social support seeking as strategies to deal with racism. In contrast, there was a significant racial/ethnic difference in use of the education/confrontation coping strategy. Asians/Pacific Islanders were more likely to use this strategy to deal with racism than were African Americans and Latinos (2.9 vs. 2.8 vs. 2.7, respectively; p <.05).

Figure 2. Coping Strategies Employed to Deal with Racism, by Race/Ethnicity: Mean Scale Scores1.

1. Range: 1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree”

Associations of Stress and Coping with Racism with UAI

We found no moderating effect of race/ethnicity for the associations between stress from racism in the gay community, coping with racism, and UAI. None of the two- and three-way interactions among these variables were statistically significant at p < .05. The three main effects and all of the interaction effects that were not statistically significant were removed in the final multivariate model.

Table 2 shows the results of bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses conducted to examine the associations of stress from racism within the gay community and coping with racism with UAI. Multivariate results showed that the main effect for stress from racism within the gay community was statistically significant. Those who were stressed when they experienced racism within the gay community were more likely to engage in UAI in the past six months than those who were not stressed (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR], 1.71; 95% Confidence Interval [CI], 1.15, 2.53; p = .0075). The main effect for avoidance coping was positive and statistically significant; a one-unit increase on the avoidant coping scale (e.g., from “somewhat agree” to “strongly agree”) corresponded to an increased AOR of UAI equal to 1.30 (95% CI, 1.06, 1.58; p = .0101). The main effects for dismissal coping, education/confrontation, and social support seeking coping were not statistically significant. We found no significant moderating effects of coping strategies on the association between stress and UAI.

Table 2.

Associations of Stress from Racism and Coping with Racism with Unprotected Anal Intercourse: Results of Bivariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses Using a Backward Elimination Process

| Bivariate | Multivariate1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio | (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted Odds Ratio | (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Stress from racism experienced in the gay community | ||||

| Never experienced racism | 1.50 | (0.92, 2.44) | 1.70 | (0.98, 2.94) |

| Stressed when experienced racism | 1.76 | (1.22, 2.54)** | 1.71 | (1.15, 2.53)** |

| Not stressed when experienced racism | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Avoidance coping | 1.22 | (1.04, 1.41)* | 1.30 | (1.06, 1.58)* |

| Dismissal coping | 0.98 | (0.84, 1.14) | 0.88 | (0.73, 1.05) |

| Education/confrontation coping | 1.03 | (0.87, 1.21) | --- | --- |

| Social support coping | 1.13 | (0.96, 1.32) | --- | --- |

. Final model retained race/ethnicity, age, nativity, sexual orientation, marital status, and lifetime history of incarceration (p <.20; data not shown; “---,“ removed main effects for education-confrontation and social-support coping (p>0.20); removed two- and three-way interactions among stress, the four coping measures, and race/ethnicity (p > .05).

p < .05;

p < .01

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicated that a large majority (84%) of MSM of color reported racism in the gay community and that racism in the gay community was a significant source of stress for these men. Specifically, more than two-thirds of our study participants reported feeling stress specifically as a result of their experiences with racism in the gay community. This stress from racism experienced in the gay community was more pronounced for Asian and Pacific Islander men than for African American and Latino men. Prior research has suggested that Asian/Pacific Islander men may be more likely to desire White partners than African American or Latino men and that they may be the least desirable sexual partners among White MSM (Paul, Ayala, & Choi, 2010; Phua & Kaufman, 2003). Given these earlier findings, it is possible that gay Asian men experience more sexual rejection based on race than other MSM of color. Previous research has shown that sexual rejection may be felt more intimately than other types of rejection (de Graaf & Sandfort, 2004; Metts, Cupach, & Imahori, 1992), which may explain why Asian/Pacific Islander MSM in this study were more likely to report being stressed by the racism they experienced in the gay community than African American and Latino men.

Stress caused by perceived racism in the gay community increased the likelihood of engaging in unprotected anal intercourse among African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino men in our study. The association between stress due to perceived racism and unsafe sexual behavior did not significantly differ across these racial groups. These findings were not surprising given that stress from a multitude of sources has been linked to increased unprotected sex among MSM in general (Calzavara et al., 2011) and perceived racial discrimination has been well demonstrated to be associated with increased stress among people of color (Barnes & Lightsey, 2005; Clark et al., 1999; Smith, 1985). As Plummer and Slane (1996) noted, racial stress can be understood as a specific form of general stress because it arises when individuals appraise a situation or event as being troubling due to racial discrimination or isolation, which leads to psychological discomfort and emotional distress.

Although utilized by men of all racial groups in our sample, there was little evidence that the various coping strategies played a protective role in buffering the influence of stress due to perceived racism experienced in the gay community on sexual risk behaviors. Rather, our data suggest that avoidance strategies exerted an independent effect on unsafe sex, potentially leading to an increase in UAI.

Prior research on diverse health issues has found that coping strategies which actively attempt to avoid sources of stress can result in greater distress (Herman-Stahl, Stemmler, & Peterson, 1994; Moghaddam et al., 2002; Noh & Kaspar, 2003; Suls & Fletcher, 1985; Utsey et al., 2000; West, Donovan, & Roemer, 2013). Barnes and Lightsey (2005) found that avoidance coping had detrimental effects for African American students in stressful racism-related situations. A possible explanation offered was been that avoidance strategies may lead to more long-term distress because they fail to adequately address the cause of stress. Avoidance strategies may also lead to more racial isolation among men who utilize this strategy and racial isolation may potentially lead to higher levels of stress that can negatively impact health (Plumber & Slane, 1996; Subramania, Acevedo, & Osypuk, 2005; Williams & Collins, 2001).

Researchers attempting to explore the benefits of social support seeking strategies in alleviating stress have found mixed results (Barnes & Lightsey, 2005; Elligan & Utsey, 1999; Utsey et al., 2000; Wang & Patten, 2002). For example, in a study of perceived racial discrimination and depression among Korean immigrants in Toronto, Noh and Kaspar (2003) found that social support seeking was associated with lower levels of depression while Barnes and Lightsey (2005), in their study of perceived racial discrimination and life satisfaction among African American college students, found no significant relationship between social support seeking and life satisfaction. Specifically in terms of HIV risk, Yoshikawa et al. (2004) found that talking about discrimination with gay friends and with family members was associated with lower levels of primary-partner UAI while low levels of conversation with family about racial discrimination was associated with higher rates of UAI among gay Asian men. In our study, utilization of the social support seeking strategy among men appeared to have no effect on the sexual risk for HIV. A possible explanation for our findings may be that we measured social support seeking rather than the type of support that they received. As Barnes and Lightsey (2005) noted, using social support seeking as a coping strategy does not imply that helpful social support was actually received. Thus, it is possible that men in our study sought support but did not receive the support needed to adequately cope with the racism-related stress they experienced within the gay community.

Problem-focused coping strategies, such as education/confrontation, have been demonstrated to be useful when dealing with perceived racism (Barnes & Lightsey, 2005; Noh & Kaspar, 2003; Wei et al., 2008; West, Donovan, & Roemer, 2013). However, we did not find a relationship between education/confrontation and UAI among men in our study. The discrepancy may be due to the way we measured problem-focused coping. Also, previous studies did not necessarily define dealing with perceived racism as not engaging in UAI (Barnes & Lightsey, 2005). Previous studies have shown that planful problem solving is an effective coping strategy (Chang et al., 2006). However, we only asked men about their immediate responses to perceived racist events rather than more planful actions such as gathering more information, attempting to change the environment, or remove the source of stress. Speaking up or educating others when they encounter instances of racism does not necessarily change the environment nor require planful action, provide a long-term goal for changing the environment, or remove the source of stress. Therefore, immediate responses to perceived racist events similar to those we measured may have less benefit for long-term relief from racism-related stress than more conscious and thoughtful actions. In addition, planful actions like educating or confronting may themselves be stressful given how socially difficult these acts or interpersonal interventions may be. This may further explain the finding discussed earlier regarding Asian/Pacific Islander men being more likely to report stress from racism they experienced since they were also more likely to report using education/confrontation as a coping strategy.

We should note three limitations in our study. First, we relied on self-reported information. Given the sensitive nature of racism, and the expected social responses to them, subjects may either over-report or under-report their personal experiences with racism as well as their use of certain coping strategies. Also, events and personal experiences that are perceived to be “racist” may be not perceived the same way by different individuals. Second, we used only nine candidate items to measure how men in our study coped with perceived racism in the gay community. It is possible that more detailed questions about coping strategies may help to better define various coping strategies used by members of this group. Also, some of the coping scales had low Cronbach alpha estimates, which can attenuate estimated associations between those scales and other study measures. Finally, our findings may have limited generalizability given that our sample was not selected randomly and came from Los Angeles County. Because Los Angeles County is both racially and sexually diverse, the dynamics of race relations in the larger society may influence race relations in the gay community. Whether this diversity leads to more racism among gay white men or less is a question that needs further examination. More studies with MSM of color, especially in places where all three groups may not be so heavily represented in the general population, will be needed in order to test the generalizability of our findings.

Despite these limitations, our findings have several implications for future research on MSM of color. Given the impact that perceived racial discrimination has on the stress MSM of color experience and on their overall sexual health, including their elevated risk for HIV, there is a critical need to identify coping strategies that buffer the impact that racism in the gay community is having on MSM of color in the United States. As Aldwin and Park (2004) noted, effects of coping are complex and highly contextual. To better understand the relationship between racism induced stress and unsafe sexual behaviors, future research should explore these questions using a more elaborate coping scale that can better identify specific strategies as well as identify various factors that lead men to utilize some strategies but not others. Also, our study focused specifically on the relationship between unsafe sex and perceived racial discrimination from gay White men. However, it should be noted that gay men of color also experience stressful situations based on racial discrimination due to both personal experiences based on individual and institutional discrimination outside of the gay community and their interactions with gay White men. These experiences with racial discrimination are likely to also influence how gay men of color cope with stress caused by racism and may potentially also lead to risky sexual behaviors through a number of mediating and/or moderating factors. In addition, as several scholars have noted, not all racism is the same (Collins, 1990). Rather, experiences of racism are felt differently based on how individuals are socially positioned and come from a number of different sources. Future research will need to explore how MSM of color experience racism from the gay community and the larger society to examine if their experiences may be different from those of heterosexual people of color in order to provide a more detailed account of how racism influences unsafe sexual behaviors.

Similarly, our findings have implications for future intervention development. First, our findings underscore the need to develop interventions which address stress from racism in the gay community and maladaptive coping strategies to reduce sexual risk for HIV among these three racial/ethnic minority groups. More importantly, as Noh and Kaspar (2003) stated, interventions targeting racial minorities must be designed keeping in mind both the client’s cultural orientation but also the client’s situation in the major social structure. It is important to acknowledge that MSM of color are positioned within a larger social structure of the gay community that has been demonstrated to value White men over men of color, not only by White men but other men of color as well (Paul, Ayala, & Choi, 2010). Interventions targeting MSM of color aimed at helping them cope with racism in the gay community must keep that larger social structure in mind when developing intervention programs and how those structures influence how MSM of color may experience racism differently than heterosexuals. It is also critical that we evaluate various strategies that members of these groups may be able to use to lessen the negative health impacts of racism.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant R01 MH069119.

Appendix 1: Eight Survey Questions Used to Create a Stress-from-Racism Measure

“Sexual partners have wanted me only because of my race or ethnicity; they pay no attention to other personal characteristics.”

“I’ve been turned down for sex because of my race or ethnicity.”

“I’ve been made to feel unwanted online because of my race or ethnicity.”

“I’ve felt white gay men have acted as if they’re better than me because of my race or ethnicity.”

“I’ve felt ignored or invisible where white gay men hang out because of my race or ethnicity.”

“I’ve felt unwelcome or that I didn’t fit into West Hollywood because of my race or ethnicity.”

“I’ve felt that white gay men are uncomfortable around me because of my race or ethnicity.”

“Overall, when you have been treated differently based on your race/ethnicity, how stressful have these experiences been for you?

Contributor Information

Chong-suk Han, Middlebury College.

George Ayala, Global Forum on MSM and HIV.

Jay Paul, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco.

Ross Boylan, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco.

Steven E. Gregorich, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco

Kyung-Hee Choi, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco.

References

- Aldwin CM, Park CL. Coping and physical health outcomes: An overview. Psychology and Health. 2004;19:277–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala G, Bingham T, Kim J, Wheeler DP, Millett GA. Modeling the impact of social discrimination and financial hardship on the sexual risk of HIV among Latino and black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:S242–S249. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, Walters K. Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT people of color microaggressions scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:163–174. doi: 10.1037/a0023244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PW, Lightsey OR. Perceived racist discrimination, coping, stress, and life satisfaction. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2005;33:48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Brandolo E, Gallo LC, Myers HF. Race, racism and health: Disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings AG, Moos RH. The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1984;4:139–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00844267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings AG, Moos RH. Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:877–891. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandolo E, ver Halen NB, Pencille M, Beatty D, Contrada RJ. Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:64–88. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzavara LM, Burchell AN, Lebovic G, Myers T, Remis RS, Raboud J, et al. The impact of stressful life events on unprotected anal intercourse among gay and bisexual men. AIDS & Behavior. 2012;16:633–643. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9879-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Mayo A, Ventimiglia M. Coping, pain severity, interference, and disability: The potential mediating and moderating roles of race and education. Journal of Pain. 2006;7:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.01.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Yoshikawa H. Perceived group devaluation, depression, and HIV-risk behavior among Asian gay men. Health Psychology. 2008;27:140–148. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EM, Daly J, Hancock KM, Bidewell JW, Johnson A, Lambert VA, Lambert CE. The relationship among workplace stressors, coping methods, demographic characteristics, and health in Australian nurses. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2006;22:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Han C, Paul J, Ayala G. Strategies for managing racism and homophobia among U.S. ethnic minority men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23:145–158. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Paul J, Ayala G, Boylan R, Gregorich SE. Experiences of discrimination and their impact on mental health among African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:868–74. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson N, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Czopp AM, Monteith MJ. Confronting prejudice (literally): Reactions to confrontations of racial and gender bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;29:532–544. doi: 10.1177/0146167202250923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf H, Sandfort TG. Gender differences in affective responses to sexual rejection. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33:395–403. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000028892.63150.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion KL. The social psychology of perceived prejudice and discrimination. Canadian Psychology. 2002;43:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Elligan D, Utsey S. Utility of an African-centered support group for African American men confronting societal racism and oppression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 1999;5:156–165. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.5.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new directions. Du Bois Review. 2011;8:115–132. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giwa S, Greensmith C. Race relations and racism in the LGBTQ community in Toronto: Perceptions of gay and queer social service providers of color. Journal of Homosexuality. 2012;59:149–185. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.648877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C. They don’t want to cruise your type: Gay men of color and the racial politics of exclusion. Social Identities. 2007;13:51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Han C. A qualitative study of the relationship between racism and unsafe sex among Asian and Pacific Islander gay men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:827–837. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C. Asian girls are prettier: Gendered presentations as stigma management among gay Asian men. Symbolic Interaction. 2009;32:106–122. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Stahl MA, Stemmler M, Peterson AC. Approach and avoidant coping: Implications for adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:649–665. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q, Devos T, Dunbar CM. The psychological costs of painless but recurring experiences of racial discrimination. Culture Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18:26–34. doi: 10.1037/a0026601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanes GE, Van Oss Marin B, Flores SA, Millett G, Diaz RM. General and gay-realted racism experienced by Latino gay men. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15:215–222. doi: 10.1037/a0014613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icard L. Black gay men and conflicting social identities. Journal of Social Work & Human Sexuality. 1986;4:180–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CR, Miller CT. Stop complaining! The social costs of making attributions to discrimination. Group Process & Intergroup Relations. 2001;6:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CR, Miller CT. Derogating the victim: The interpersonal consequences of blaming events on discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;27:254–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser CR, Miller CT. A stress and coping perspective on confronting sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:168–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft JM, Beeker C, Stokes JP, Peterson JL. Finding the “community” in community-level HIV/AIDS interventions: Formative research with young African American men who have sex with men. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27:430–441. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon BL. Stress, coping, and health. In: Rice VH, editor. Handbook of stress, coping, and health: Implications for nursing research, theory, and procedures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. pp. 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JI, Alessi EJ. Stressful events, avoidance coping, and unprotected anal sex among gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:293–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor D. Responses to racism: A taxonomy of coping styles used by aboriginal Australians. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:56–71. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, Downey G, Purdie VJ, Davis A, Pietrzak J. Sensitivity to status-based rejection: Implications for African American students’ college experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:896–918. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.4.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metts S, Cupach WR, Imahori TT. Perceptions of sexual compliance: resisting messages in three types of cross-sex relationships. Western Journal of Communication. 1992;56:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: Moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:232–238. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Ethnicity and Health. 2006;35:888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JP, Ayala G, Choi K. Internet sex ads for MSM and partner selection criteria: The potency of race/ethnicity online. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47:528–538. doi: 10.1080/00224490903244575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phua VC, Kaufman G. The crossroads of race and sexuality: Date selection among men in internet “personal” ads. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:981–994. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer DL, Slane S. Patterns of coping in racially stressful situations. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:302–315. [Google Scholar]

- Poon MK, Ho PT. Negotiating social stigma among gay Asian men. Sexualities. 2008;11:245–268. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond HF, McFarland W. Racial mixing and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS & Behavior. 2009;13:630–637. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth RS, Geisser ME. Educational achievement and chronic pain disability: Mediating role of pain-related cognitions. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2002;18:286–292. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin D. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Seal DW, Kelly JA, Bloom FR, Stevenson LY, Coley BI, Broyles LA the Medical College of Wisconsin City Project Research Team. HIV prevention with young men who have sex with men: What young men themselves say is needed. AIDS Care. 2000;12:5–26. doi: 10.1080/09540120047431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Shavers BS. Racism and health inequity among Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98:386–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EMJ. Ethnic minorities: Life stress, social support and mental health issues. The Counseling Psychologist. 1985;13:537–579. [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Fletcher B. The relative efficacy of avoidant and nonavoidant coping strategies: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 1985;4:249–288. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Sung MR. Minority stress and psychological distress among Asian American sexual minority persons. The Counseling Psychologist. 2010;38:848–872. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Acevedo-Garcia D, Osypuk TL. Racial residential segregation and geographic heterogeneity in black/white disparity in poor self-rated health in the US: A multilevel statistical analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:1667–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson VLS. Racism: Perceptions of distress among African Americans. Community Mental Health Journal. 2002;38:111–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1014539003562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Ponterotto JG, Reynolds AL, Cancelli AA. Racial discrimination, coping, life satisfaction, and self-esteem among African Americans. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2000;78:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2007;16:219–242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Patten SB. The moderating effects of coping strategies on major depression in the general population. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;47:167–173. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Ku T, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, Liao K. Moderating effects of three coping strategies and self-esteem on perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms: A minority stress model of Asian international students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:541–462. doi: 10.1037/a0012511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Heppner PP, Ku T, Liao KY. Racial discrimination stress, coping, and depressive symptoms among Asian Americans: A moderation analysis. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2010;1:136–150. [Google Scholar]

- West LM, Donovan RA, Roemer L. Coping with racism: What works and doesn’t work for black women. Journal of Black Psychology. 2010;36:331–349. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: The added effects of racism and discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;896:173–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Report. 2001;116:404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ER, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Yoshikawa H. Experiences of and responses to social discrimination among Asian and Pacific Islander gay men: Their relationship to HIV risk. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:68–83. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.1.68.27724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonghongkul T, Moore SM, Musil C, Schneider S, Deimling G. The influence of uncertainty in illness: Stress, appraisal, and hope on coping in survivors of breasts cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2000;23:422–429. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200012000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolwine D. Community in gay male experience and moral discourse. Journal of Homosexuality. 2000;38:5–37. doi: 10.1300/J082v38n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Wilson PA, Chae DH, Cheng J. Do family and friendship networks protect against the influence of discrimination on mental health and HIV risk among Asian and Pacific Islander gay men? AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:84–100. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.1.84.27719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni B, Crawford I. Minority stress and sexual problems among African-American gay and bisexual men. Achieves of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36:569–578. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]