Abstract

In the present study, we characterized the in vitro modulation of NETs (neutrophil extracellular traps) induced in human neutrophils by the opportunistic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans, evaluating the participation of capsular polysaccharides glucuronoxylomanan (GXM) and glucuronoxylomannogalactan (GXMGal) in this phenomenon. The mutant acapsular strain CAP67 and the capsular polysaccharide GXMGal induced NET production. In contrast, the wild-type strain and the major polysaccharide GXM did not induce NET release. In addition, C. neoformans and the capsular polysaccharide GXM inhibited PMA-induced NET release. Additionally, we observed that the NET-enriched supernatants induced through CAP67 yeasts showed fungicidal activity on the capsular strain, and neutrophil elastase, myeloperoxidase, collagenase and histones were the key components for the induction of NET fungicidal activity. The signaling pathways associated with NET induction through the CAP67 strain were dependent on reactive oxygen species (ROS) and peptidylarginine deiminase-4 (PAD-4). Neither polysaccharide induced ROS production however both molecules blocked the production of ROS through PMA-activated neutrophils. Taken together, the results demonstrate that C. neoformans and the capsular component GXM inhibit the production of NETs in human neutrophils. This mechanism indicates a potentially new and important modulation factor for this fungal pathogen.

C. neoformans is an opportunistic fungal pathogen of global distribution, which grows predominantly in the form of yeast and has a polysaccharide capsule that differentiates this microorganism from other pathogenic fungi. Cryptococcosis is prevalent in individuals with T cell deficiencies, such as those infected with HIV1. The capsular polysaccharide is the most well-studied structure of C. neoformans and is considered a major virulence factor2. In a murine experimental model, acapsular mutants are either incapable of inducing cryptococcosis or exhibit reduced virulence3,4. Biochemical studies have shown that the C. neoformans capsule primarily comprises glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), representing approximately 88% of the capsule. GXM is a polymer that consists mostly of a linear α-(1–3)-mannan substituted with β-(1–2)-glucopyranosyluronic acid and β-(1–4)-xylopyranosyl. O-acetylation occurs on the C-6 of about half of the mannose residues5,6.

Several studies have described GXM interactions with immune cells7. Macrophages accumulate large amounts of GXM over long period of time in vitro, and, in contrast, neutrophils accumulating smaller amounts over a shorter time, indicating potential differences in receptor recognition and GXM digestion7. It has been suggested that GXM induces L-selectin shedding8 and C5aR expression in neutrophils9.

The C. neoformans capsule also comprises 10% glucuronoxylomannogalactan (GXMGal) and 2% mannoproteins. The GXMGal consists of an α-(1→6)-galactan backbone with galactomannan side chains that are further substituted with variable numbers of xylose and glucuronic acid residues10.

GXMGal induces the expression of Fas-L and apoptosis in murine peritoneal macrophages and is a more efficient polysaccharide regarding nitric oxide (NO) induction and TNF-α secretion11.

Neutrophils are critical effector cells of the innate immune system, which are rapidly recruited to sites of inflammation and exert protective or pathogenic effects, depending on the inflammatory milieu. Neutrophils kill C. neoformans primarily via NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS production12,13. Consistently, neutrophils from chronic granulomatous disease (GCD) patients, which exhibit defective ROS production, do not kill these pathogens, although the phagocytosis of the fungus occurs14. In addition, neutrophils combat pathogens through the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), comprising decondensed chromatin associated with granular and cytosolic proteins15. NETs retain and kill microorganisms and restrict tissue damage caused by neutrophil microbicidal molecules associated with these scaffolds. Different microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, protozoa and viruses induce NET release15,16,17,18. Among fungi, Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus nidulans and Cryptococcus gattii induce NET release and are susceptible to its fungicidal effects18,19,20,21,22.

The mechanisms of NET induction are not fully understood. Chromatin decondensation has been associated with the citrullination of histones through peptidylarginine deiminase-4 (PAD4)23,24,25. In addition, both neutrophil elastase (NE) and myeloperoxidase are required for NET formation14. Moreover, another key stimuli for NET production are ROS generation through NADPH oxidase19.

In the present study, we provided the first description of the in vitro modulation of NET formation by C. neoformans, evaluating the participation of its capsular polysaccharides, GXM and GXMGal, in human neutrophils. The acapsular strain CAP67 and the polysaccharide GXMGal induced NET release. In contrast, wild-type C. neoformans and its polysaccharide GXM were unable to induce NET formation and inhibited NET release.

Results

Acapsular Cryptococcus neoformans induces NET release

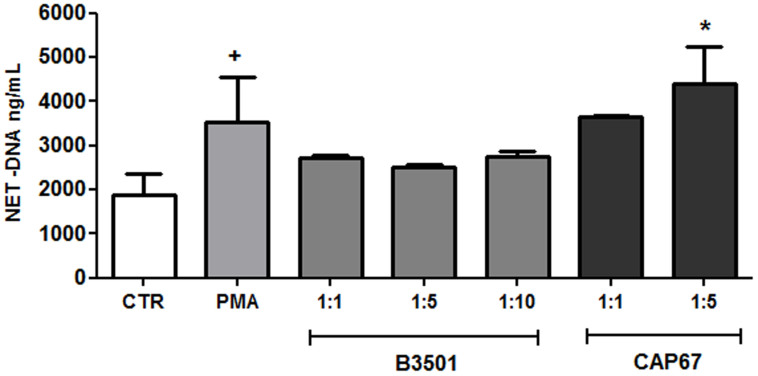

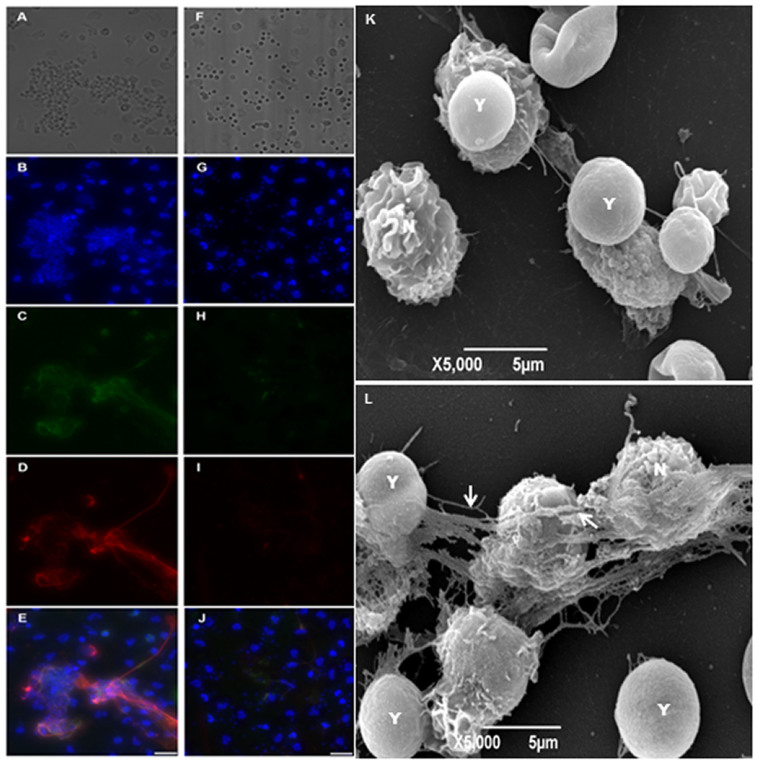

NET induction by C. neoformans was evaluated in both wild-type (B3501 strain) and acapsular (CAP67 mutant strain) fungi. The model was based on the in vitro interaction of neutrophils with the yeasts for 90 min, followed by the evaluation of the NET-DNA concentration in the supernatant. Although wild-type C. neoformans did not induce NET release, the acapsular strain was a potent inducer of this process (Figure 1). PMA, which was used as a control, also induced NET release (Figure 1). Next, we characterized the induction of NET induced by wild-type and mutant C. neoformans strains through the labeling of DNA with DAPI and NET-associated proteins with specific antibodies (Figure 2). We observed that acapsular mutant CAP67 yeasts ensnared by classical NET meshes were labeled with DAPI and anti-elastase and anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies (Figure 2B–E). Consistent with the DNA quantification, NETs were not observed with wild-type C. neoformans (Figure 2F–J). No labeling could be observed with secondary antibodies alone (data not shown). Similarly, NET scaffolds were not observed in the wild-type C. neoformans interaction with neutrophils (Figure 2K), contrary to interactions with acapsular mutant CAP67 yeasts, which were trapped by NETs as depicted through scanning electron microscopy (Figure 2L).

Figure 1. Inhibition of NET release by Cryptococcus neoformans wild-type, and NET induction by acapsular mutant CAP67.

Human neutrophils were incubated for 90 min at 35°C in the absence (Control, CTR) or presence of 100 µM PMA, B3501 or CAP67 yeasts (at the indicated ratios), and the supernatants were evaluated for DNA content. Individual experiments from 12 donors were performed in duplicate. +p<0.05 PMA versus unstimulated control (CTR); *p<0.05 CAP67 unstimulated control (CTR).

Figure 2. NET release induced by acapsular mutant CAP67 and the absence of NET production by wild-type Cryptococcus neoformans.

Human neutrophils were incubated with acapsular mutant CAP67 (left column) or B3501 yeasts (right column) at a 1:5 ratio on poly-L-lysine treated coverslips, for 90 min. at 35°C. (A, F) Differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy; (B, G) Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI; (C, H) anti-elastase staining (secondary antibody-FITC); (D, I) anti-myeloperoxidase (secondary antibody-Texas-Red); (E, J) Overlay of (B-D) and (G, H, I) images, respectively. Bars = 20 μm. Human neutrophils were incubated with C. neoformans at 1:5 ratio for 90 min. at 35°C and processed for SEM. The images show the interaction of neutrophils with C. neoformans (K) B3501 or (L) CAP67, strains. The arrows indicate NETs; N = neutrophil and Y = yeasts.

CAP67-induced NET production is dependent on ROS and PAD-4

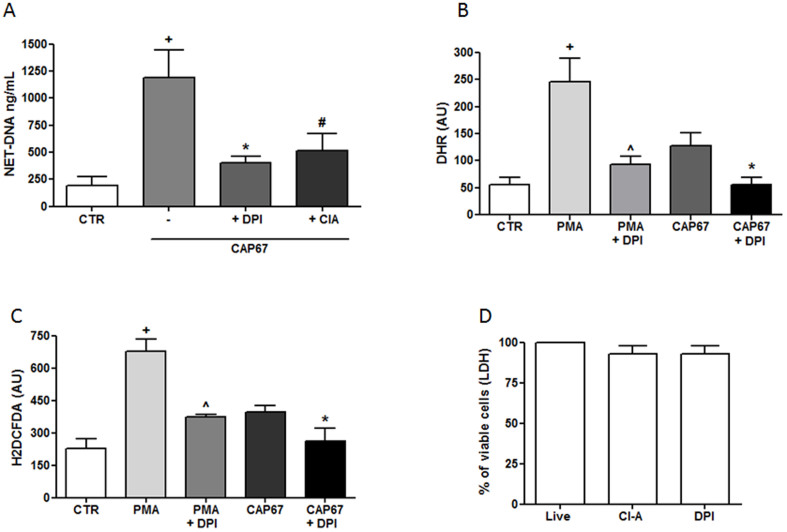

NET release involves the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated through NADPH oxidase. Thus, we investigated the role of ROS on NET release induced through CAP67 yeasts after pretreating the neutrophils with DPI, which is an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase. The results showed that NET induction was inhibited 66% following DPI treatment of neutrophils (Figure 3A). Peptidylarginine deiminase-4 (PAD-4) is another important enzyme associated with NET release. The addition of the PAD-4 inhibitor chloro-amidine (ClA) also inhibited 57% of the NET release induced through acapsular CAP67 yeasts (Figure 3A). Consistently, DHR and H2DCFDA probes revealed that acapsular mutant CAP67 yeasts induced ROS production in neutrophils (Figure 3B and 3C). Regardless of the probe used, ROS production was significantly decreased in the presence of DPI (Figure 3B and 3C). Treatment with either DPI or ClA was not toxic to neutrophils, as measured by LDH release (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Signaling pathways associated with NET extrusion induced by the acapsular CAP67 strain.

(A) Human neutrophils were incubated with acapsular CAP67 and/or DPI or chloro-amidine (ClA). (B, C) Human neutrophils were preincubated with DPI (10 μg/mL), followed by DHR or H2DCFDA, washed and incubated with CAP67 yeast or PMA. The data are presented as arbitrary fluorescence units (AU) of three experiments. (D) Lactate dehydrogenase assay of neutrophils alone (control) or in the presence of DPI or ClA. The results represent the means ± SD of 4 donors performed in duplicate. +p<0.05 unstimulated control (CTR) versus CAP67 or PMA; *p<0.05 comparing CAP67 to CAP67 + DPI; #p<0.05 CAP67 versus CAP67 + ClA and ∧p<0.05 PMA compared to PMA + DPI.

The capsular polysaccharide GXM inhibited NET production in neutrophils

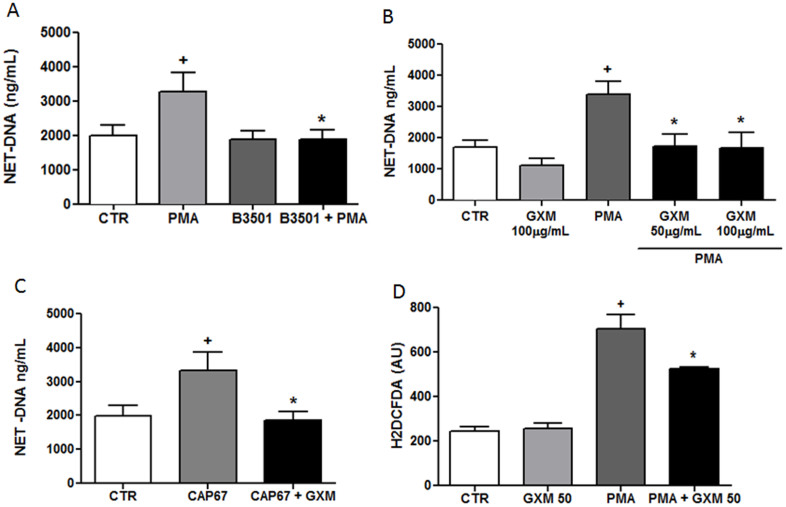

Wild-type yeast failed to induce NET and also inhibited NET formation induced by PMA (Figure 4A). We therefore, evaluated the ability of GXM, the polysaccharide purified from wild-type yeast capsules, to modulate NET release. The results demonstrated that GXM did not induce NET release, even at higher concentrations were used. Moreover, GXM inhibited NET induction through PMA (Figure 4B). The addition of purified GXM inhibited NET formation induced by acapsular CAP67 strain (Figure 4C) and Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes (Supplementary Fig. S1). Inhibition of NET formation by GXM was correlated with the modulation of ROS production (Figure 4D). Therefore, the addition of GXM to neutrophils stimulated with PMA inhibited approximately 25% of ROS production. The ability of GXM to inhibit NET formation by neutrophils was investigated in cultures stimulated with PMA in the presence of Sytox Green, a DNA-specific dye. NET formation induced by PMA (Figure 5A–C) was markedly inhibited after treating neutrophils with GXM for 30 min (Figure 5D–F). Interestingly, although GXM did not induce NET release, this polysaccharide was phagocytosed by neutrophils, as revealed through intracellular staining with an anti-GXM monoclonal antibody (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 4. Cryptococcus neoformans GXM inhibits NET release.

(A) Human neutrophils were incubated in the absence (control, CTR) or presence of 100 µM PMA and capsular B3501 yeasts at a 1:5 ratio. After 90 min, the supernatants were collected and assayed for DNA content. The results are presented as the means ± SD of 4 donors performed in duplicate. +p<0.05 PMA versus unstimulated control (CTR); *p<0.05 PMA versus PMA + B3501 yeasts. (B) Human neutrophils were incubated with PMA and GXM (as indicated), and the supernatants were processed as described above. The results are presented as the means ± SD of 5 donors performed in duplicate. +p<0.05 compared to unstimulated control (CTR); *p<0.05 related to PMA. (C)Human neutrophils were incubated in the absence (control, CTR) or presence of acapsular CAP67 yeasts (1:5) or purified GXM (50 µg/mL), and supernatants were processed as described above. The results are presented as the means ± SD of 4 donors performed in duplicate. +p<0.05 PMA versus unstimulated control (CTR); *p<0.05 PMA versus PMA + indicated yeast.(D)Human neutrophils incubated with H2DCFDA, were washed and stimulated with 100 µM PMA and 50 µg/mL of GXM. The data are presented as the means ± SD of 3 donors performed in duplicate. +p <0.05 PMA versus unstimulated control (CTR); *p <0.05 PMA versus PMA+GXM.

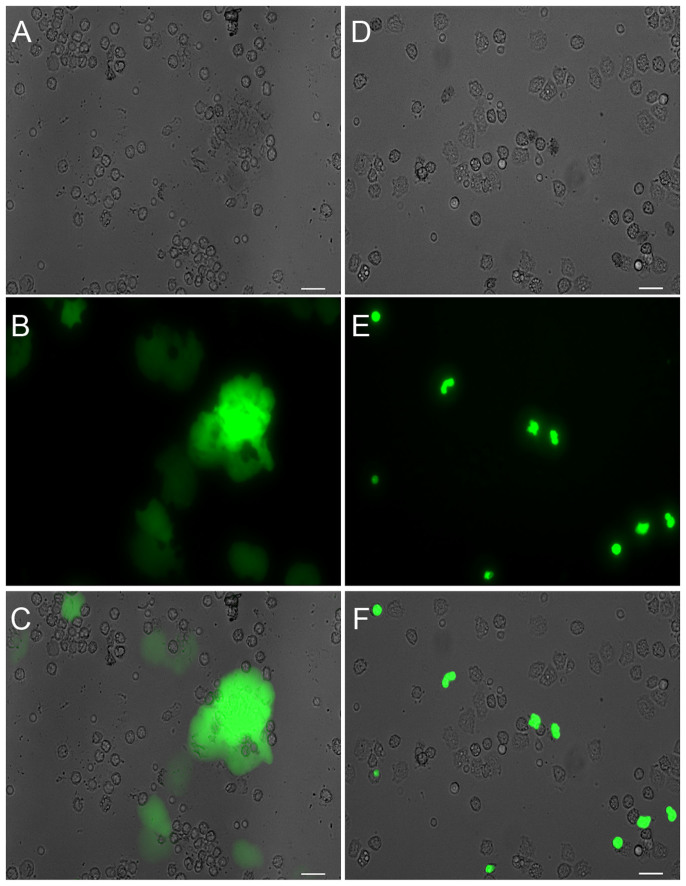

Figure 5. Immunofluorescence detection of NET inhibition by Cryptococcus neoformans GXM.

Human neutrophils were incubated with PMA with or without GXM (50 µg/mL) for 30 min. (A) Differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy of PMA activated neutrophils; (B) Sytox Green staining, (C) Overlay of A and B images; (D)DIC microscopy of PMA-activated neutrophils pretreated with GXM; (E) Sytox Green staining; (F) Overlay of images D and E. Bars = 20 μm.

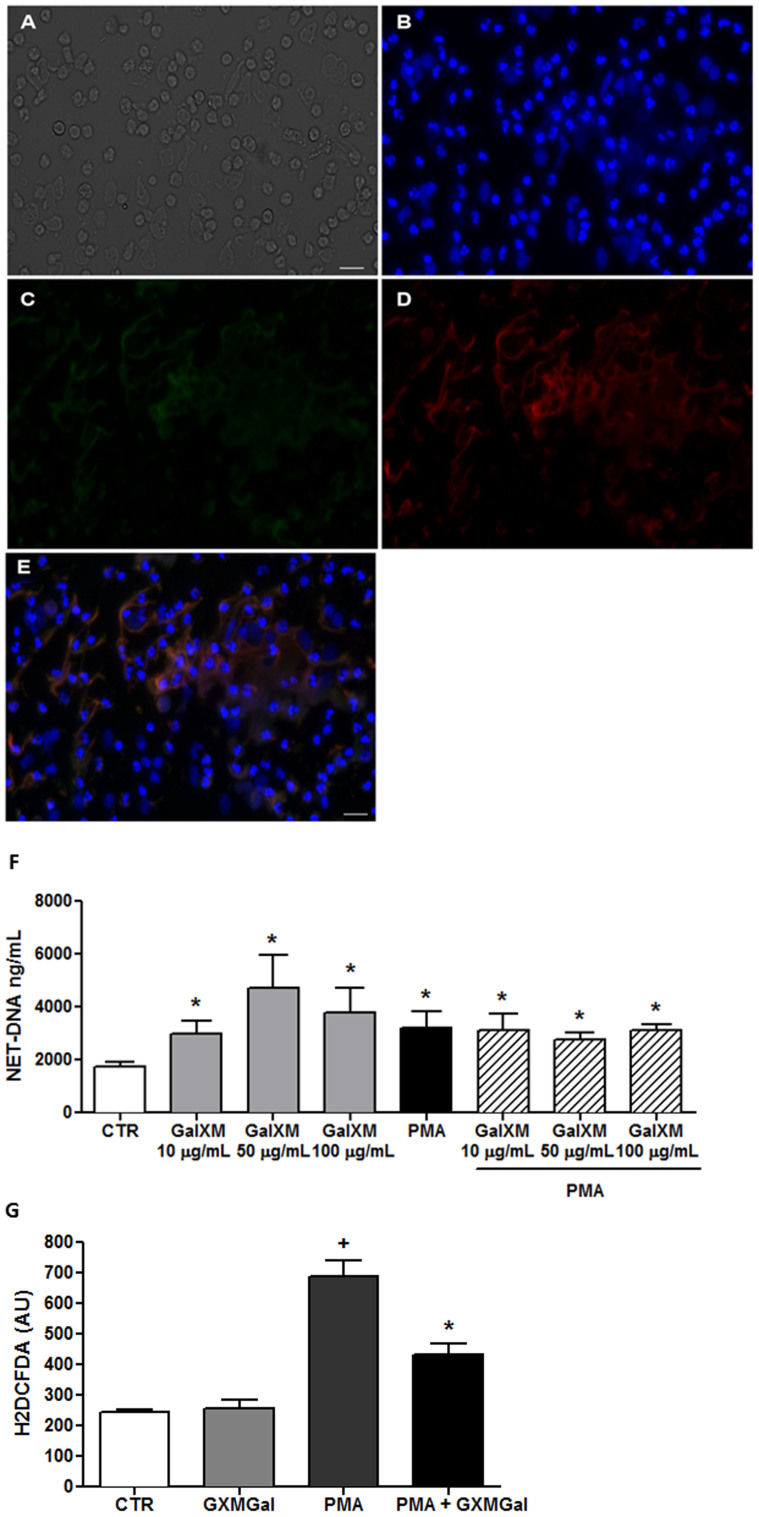

Staining with DAPI, anti-elastase and anti-MPO antibodies revealed that purified polysaccharide GXMGal, triggered NET release (Figure 6A–E). Furthermore, GXMGal induced NET release in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6F). Although unable to affect NET release induced by PMA, GXMGal potentiated NET release induced by L. amazonensis (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 6. Cryptococcus neoformans GXMGal induces NET release.

Human neutrophils were incubated with GXMGal (50 µg/mL). (A) Differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy; (B) Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI; (C) anti-elastase (secondary antibody-FITC); (D) anti-myeloperoxidase (secondary antibody-Texas-Red); (E) Overlay of B, C, and D images. Bars = 20 μm. Neutrophils were obtained from the same donor in both figures. (F) Human neutrophils were incubated in the absence (control, CTR) or presence of PMA and GXMGal at the indicated doses, and the supernatants were collected and evaluated for DNA content. The results are presented as the means ± SD of 5 donors performed in duplicate. *p<0.05 compared with unstimulated control (CTR). (G) Human neutrophils were incubated with H2DCFDA, followed by washing and stimulation with PMA (100 µM) and GXMGal (50 µg/mL). The data from 3 different donors performed in duplicate are shown as the mean arbitrary fluorescence units (AU) ± SD. *p<0.05 compared with unstimulated control (CTR); +p<0.05 compared with PMA.

Surprisingly, GXMGal failed to induce ROS production (Figure 6G), suggesting a ROS-independent mechanism of NET release. Similar to GXM, GXMGal inhibited the production of ROS induced by PMA (Figure 4B). LDH release experiments showed that neither GXM nor GXMGal were toxic to neutrophils at the concentrations used in this study (Supplementary Fig. S3A).

NET production by human neutrophils exhibits fungicidal activity

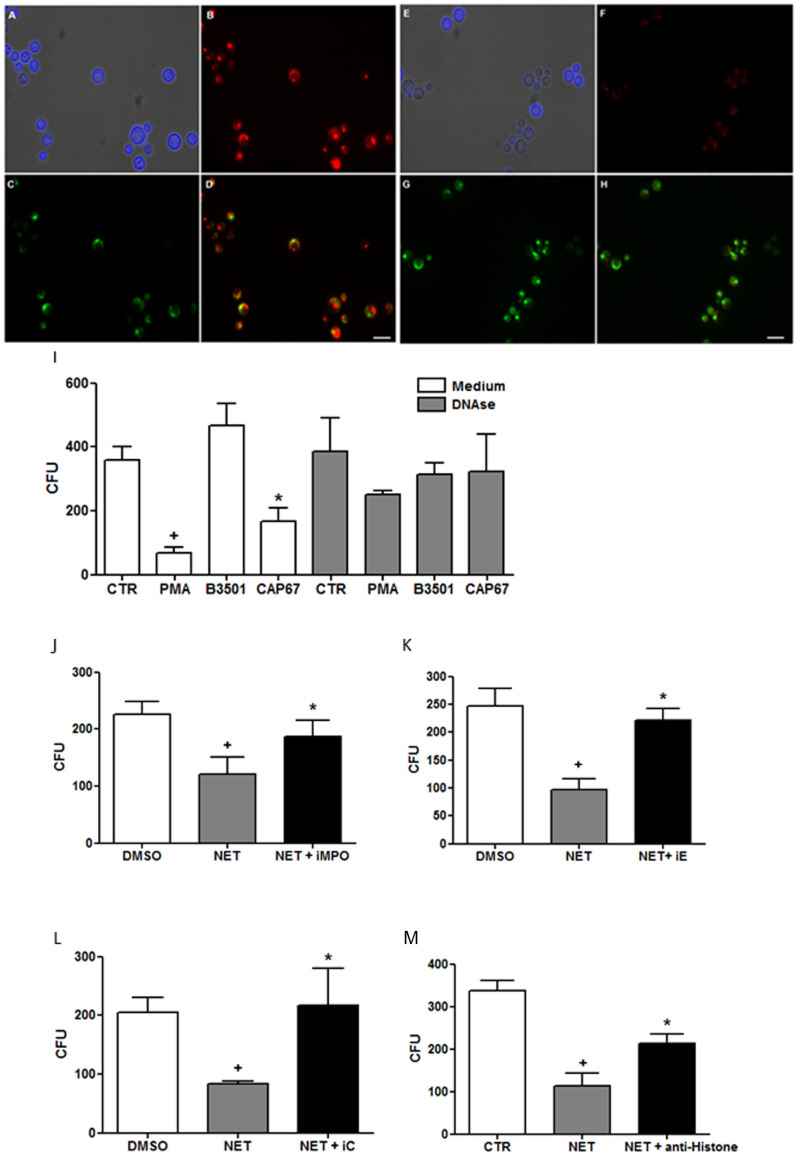

The fungicidal activity of the released NET was evaluated on wild-type yeasts using previously induced NET-enriched supernatants. To determine the fungicidal activity of NETs, the viability of wild-type fungi was evaluated after incubation with NETs for 18 h using live and dead probes specific for yeast. The results demonstrated that only fungi treated with NETs died, as the probe was not metabolized under these conditions (i.e., changing from green to red), indicating cell death (Figure 7A–H).

Figure 7. NET microbicidal activity on Cryptococcus neoformans.

B3501 wild-type yeasts were incubated overnight in the absence or presence NET-enriched supernatants, and stained with calcofluor or the Live/Dead probe FUN®1 (live yeasts metabolize green FUN1 to a red fluorescent dye; dead yeasts remained green). (A)B3501 + control supernatant stained with calcofluor; (B, C) B3501 + control supernatant labeled with FUN1;(D) Overlay of B and C images depicting live yeasts. (E) B3501 + NET-enriched supernatant stained with calcofluor; (F, G) B3501 + NET-enriched supernatant labeled with FUN1; (H) Overlay of F and G images. Bars = 20 µm. Human neutrophils were incubated in the presence or absence of PMA, capsular B3501 or acapsular CAP67 yeasts. Supernatants were added to cultures of wild-type B3501 yeasts in the presence or absence of DNAse (I), myeloperoxidase inhibitor (J), elastase inhibitor III (K), collagenase I inhibitor (L) and anti-histone neutralizing antibody (M) and growth/viability was evaluated as colony-forming units (CFU) relative to the control. The data are presented as the mean CFU ± SD of 4 donors performed in triplicate. +p<0.05 compared with unstimulated control (PBS-CTR or DMSO); *p<0.05 compared with PMA.

These results demonstrated that although wild-type B3501 yeasts did not induce NET release, they suffered the fungicidal effect of NET-rich supernatants previously induced by PMA or acapsular CAP67 yeasts. Thus, NET-enriched supernatants induced by PMA or CAP67 reduced the number of B3501 colony forming units 80% and 54%, respectively (Figure 7I). Supernatants generated by B3501-stimulated neutrophils did not affect the number of CFU, as this yeast did not induce NET release. The disruption of the NET scaffold using DNAse abolished the observed fungicidal effects (Figure 7I). The increased growth of wild-type yeast was observed after DNAse treatment of NET-enriched supernatants induced through PMA and CAP67. However, supernatants from control un-stimulated neutrophils incubated or not with DNAse did not show fungicidal activity (Figure 7I).

To better characterize the fungicidal effect, wild-type yeasts were treated with NET-enriched supernatants in the presence of different neutralizing reagents for 18 h, and the CFU was determined. Inhibition of elastase, myeloperoxidase, collagenase and histone significantly reversed the toxicity of NETs on the growth of wild-type yeast (Figure 7J–M). In addition, the results of the XTT assay showed that no direct cytotoxicity of the inhibitors on the fungus (Supplementary Figure 3B).

Discussion

Neutrophils play an essential role in host defense against fungi, and patients with decreased number or function of these cells are predisposed to fungal infections. The increased survival of C. neoformans-infected mice after treatment with G-CSF has been previously reported26. Conversely, neutrophil depletion (around two days) reduces susceptibility to pulmonary cryptococcosis, indicating that this fungus somehow modulates the response of neutrophils, reducing the microbicide potential of these cells during lung infection27. Among the anti-fungal strategies of neutrophils, NET formation plays an important role, as C. albicans, A. fumigatus, A. nidulans and C. gattii induce the formation of NETs, in which these organisms are subsequently trapped and killed18,19,21,22,28. In addition, aspergillosis is the leading cause of death in patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), in which neutrophils are unable to release NETs28,29. It has also been reported that NET formation was restored through gene therapy in a CGD patient, leading to the remediation of refractory invasive aspergillosis19. Although a role for NETs has been described for some fungi, few species have been analyzed. Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate the role of this mechanism for C. neoformans.

The results reported here demonstrated that only acapsular C. neoformans strain induces NET release by human neutrophils. NET structures, were identified as DNA-containing scaffolds associated with elastase and MPO. The ultrastructural features of NET-ensnared acapsular CAP67 yeasts were also observed using scanning electron microscopy. The wild-type C. neoformans strain did not induce NET release, as NET-DNA was not detected in neutrophil-yeast culture supernatants or evidenced through immunofluorescence and scanning electron microscopy.

Most of the stimuli that trigger NET release indicate a dependency of oxidative stress generated by the NADPH oxidase19,30,31,32. Thus, reactive oxygen species induced through this multienzyme complex are also involved in NET induction by CAP67 yeasts, as NET release by these mutant yeasts is inhibited using DPI. Another crucial step in NET extrusion is chromatin decondensation, which depends on peptidylarginine deiminase-4 (PAD-4)-mediated citrullination of histones24,25. Herein, we provided the first demonstration of the involvement of PAD-4 in NET formation triggered by C. neoformans, as NET release induced by the acapsular CAP67 mutant was significantly reduced using the enzyme inhibitor chloro-amidine. Consistent with these observations, previous studies have shown that PMA-stimulated NETosis was also reduced through PAD-4 inhibition33.

Our data undoubtedly demonstrated that the NET produced by human neutrophils kills C. neoformans because we used a system that ensures yeast viability or death, based on mitochondrial activity. Urban and colleagues previously suggested NET toxicity to C. neoformans18. However, in this study, it was unclear whether the fungus was dead or whether growth was paralyzed through a fungistatic effect. Thus, we used a two-color fluorescent probe to assess yeast viability, and the results showed that NETs exert clear fungicidal activity on C. neoformans, suggesting that both the plasma membrane integrity and metabolic function are affected through NETs. Moreover, we showed that colony-forming units of C. neoformans were significantly decreased after treatment with NET-enriched supernatants obtained from different sources.

Other relevant information included the identification of NET-associated molecules responsible for the fungicidal properties of these structures. These data demonstrated that the killing of C. neoformans decreased when NET-enriched supernatants were treated with MPO, collagenase and elastase inhibitors. We also showed that histones participate in NET-mediated killing, as a histone-blocking antibody reverted C. neoformans killing. These findings indicate that the fungicidal process results from the engagement of several molecules acting cooperatively.

Interestingly, we also observed that the mutant acapsular strain CAP67 and the polysaccharide GXMGal induced the production of NET. It is possible that GXMGal is the prominent polysaccharide in the mutant strain capsule, been responsible for NET induction. Moreover, NET induction by GXMGal seems to occur in a ROS independent way, as this capsular polysaccharide does not induce the production of ROS in neutrophils. Stimuli that induce NET production without the participation of ROS have been described24,34,35, although the signaling pathways associated with ROS-independent NET production have yet to be clarified24,34,35. It was also demonstrated that C. albicans β-glucans induce NET formation by a ROS-independent mechanism, utilizing fibronectin and ERK-signaling pathways through complement receptor 3 (CD11b/CD18)36. Thus, further studies regarding the signaling pathways and receptors associated with the production of NET induction through GXMGal are needed. We also observed that GXMGal acts through the inhibition of ROS production by neutrophils activated by PMA. This finding supports the hypothesis that the role of NET induction by GXMGal is independent of ROS production.

In the present study, we evaluated the in vitro interaction between neutrophils and C. neoformans to determine a role for the capsular polysaccharide GXM. In addition to not inducing NET formation, purified GXM inhibited the production of neutrophil extracellular traps stimulated through different inducers. Recently, Springer and colleagues21 demonstrated (assessed only by scanning electron microscopy) that a not virulent mutant (deficient in the gene CAP59, associated with production of polysaccharide capsule) produced more NETs than wild-type fungus in a model of Cryptococcus gattii-neutrophil interaction, which only induced the rudimentary production of NET. These findings are consistent with experiments using C. neoformans, where the acapsular mutant strain CAP67 induced NET and the wild-type yeast did not. Therefore, it is likely that the polysaccharide capsule acts negatively in the modulation of NET production. Indeed, this property adds a new function for virulent wild-type C. neoformans as an inhibitor of NET formation through the GXM capsular polysaccharide. The inhibition of NET through GXM is significant, as this effect constitutes an escape mechanism evolved by C. neoformans. Furthermore, there are few descriptions of microorganism molecules that modulate NETs killing and/or trapping properties, such as the production of DNases37,38,39,40, proteases41 and the protein hydrophobin RodA from A. fumigatus20. Thus, NET-inhibition by C. neoformans could contribute to the dissemination and disease severity of this fungus.

GXM has demonstrated regulatory action on the immune system, specifically for the treatment of other autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In a murine model of RA, induced by type II collagen, the treatment of animals with GXM improved the prognosis of disease42. Currently, NETosis has been associated with different autoimmune conditions, with great emphasis on the pathophysiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)43. Therefore, it is possible that GXM directly acts on neutrophils and modulates the production of NETs in patients with SLE or other pathologies associated with NETs, such as vasculitis and deep vein thrombosis44. In summary, the capsular polysaccharide GXM has a potential role as a therapeutic tool, which deserves further investigation.

Methods

Cryptococcus strains

Cryptococcus neoformans wild-type (B3501) and GXM negative (CAP67)45 strains were cultured in defined medium46, for 48 h at 37°C with continuous shaking (100 rpm). The yeasts were washed twice, resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium and used at neutrophil/fungus ratios of 1:1, 1:5 or 1:10.

Capsular polysaccharide purification

Purification procedures were adapted from protocols established for the isolation and purification of GXMGal from culture supernatant of GXM negative C. neoformans Cap 67 strain6, and GXM from encapsulate strains47. Briefly, cells grown in defined liquid medium48 at 37°C with continuous shaking (100 rpm) for 5 days were removed through centrifugation (12,000 g for 1 h at 4°C), and the capsular polysaccharides in the supernatant were precipitated after adding three volumes of cold ethanol. To separate GXMGal from mannoproteins, the capsular polysaccharides were fractionated using lectin-affinity chromatography on a XK-26 column (Pharmacia) packed with 70 mL Concanavalin A-Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia) at 4°C. The unbound polysaccharide fractions, containing GXMGal, were localized through a phenol-sulfuric reaction49, pooled, dialyzed against distilled water and lyophilized. Pure GXMGal was obtained through anion-exchange chromatography on a MonoQ (HR16/10) column using a 50 mL superloop49.

GXM was purified by differential precipitation with CTAB47. Briefly, capsular polysaccharides isolated from the culture supernatant by precipitation with ethanol were dissolved in 0.2 M NaCl (10 mg ml-1) and CTAB (3 mg mg-1 of polysaccharides) was added slowly. Then, a solution of 0.05% CTAB was added and the GXM was selectively precipitated. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation and washed with 2% acetic acid in ethanol then in 90% ethanol. The precipitate was dissolved in 1 MNaCl and three volumes of ethanol were added to precipitate the GXM. The precipitate was centrifuged, washed with 2% acetic acid in ethanol and then with ethanol, dissolved in water and lyophilized.

To eliminate potential LPS contamination, 10 mg of GXMGal or GXM preparations were dissolved in LPS-free water and further purified through chromatography on a column of Polimixin B-Agarose (Sigma) equilibrated with LPS free-water. Purified GXMGal or GXM were eluted with 12 mL of LPS free-water, recovered and lyophilized.

Neutrophil isolation

Human neutrophils from healthy donors were isolated through density gradient centrifugation (Histopaque; Sigma), followed by the hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes. Purified neutrophils (≥ 95% purity) were maintained on ice until further use. Blood samples were collected from subjects after obtaining informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approval was obtained from the ethical review board.

Quantification of NET Release

Neutrophils (106) were incubated with or without 100 nM PMA (Calbiochem), C. neoformans (B3501 and CAP67) and capsular polysaccharides (GXM or GXMGal) at different neutrophil/fungus ratios and polysaccharide concentrations. After 1 h, restriction enzymes (ECOR1 and HINDIII, 20 µnits/mL each, BioLabs) were added to the cultures, followed by incubation for 30 min at 35°C. NET-DNA was quantified in the culture supernatant using the Picogreen dsDNA Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescence

Neutrophils were incubated with or without C. neoformans (B3501 and CAP67), PMA, GXM or GXMGal for 1 h and 30 min, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. The slides were stained with DAPI (Sigma), anti-GXM (10 μg/mL; mAb 18B7), anti-elastase (Genetex), or anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies (Genetex), followed by anti-rabbit-FITC (Vector Labs) or anti-mouse-Texas red (Molecular Probes). In some experiments, live neutrophils (treated or not with GXMor PMA) were stained with Sytox Green (Invitrogen), a DNA-specific vital dye. The epifluorescence was evaluated using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope.

Scanning electron microscopy

Adhered neutrophils on coverslips treated with 0.01% poly-L-lysine were incubated with C. neoformans (B3501or CAP67) at a 5:1 ratio for 90 min at 35°C, 5% CO2. The cultures were fixed using 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, followed by postfixation with 1% osmium tetroxide and 0.8% potassium ferricyanide and dehydration with an ascending ethanol series. After dehydration and critical point drying, the specimens were coated with gold and analyzed using a JEOL 1530 scanning electron microscope.

Fungicidal activity of NET-enriched supernatants

NET-enriched supernatants were produced after treating neutrophils (106/100 μL) with 100 nM PMA for 3 h at 35°C, 5% CO2, accordingly to Guimarães-Costa et al (2014)50. The neutrophils were subsequently centrifuged, and the NET-DNA was quantified in the supernatants and used at 2500 ng/mL throughout this study. To examine fungicidal activity, the yeasts (106) were incubated for 20 h at 37°C with NET-enriched supernatants with or without the following reagents: elastase inhibitor III (10 μg/mL), myeloperoxidase inhibitor (1 μg/mL), collagenase inhibitor I (1 μg/ml), mAb anti-histone (5 μg/μL) or DNAse (2U). Subsequently, the cells were 1:1000 diluted and plated on Sabouraud agar for CFU quantification after 48 h of growth at 30°C. NET-enriched supernatants were also added to 106 wild-type fungus for 24 h, and fungicidal activity was evaluated using a Live/Dead assay specific for yeasts according to the manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Probes).

ROS detection

Neutrophils (106) were preincubated with diphenylene iodonium (DPI, 10 µg/mL, Sigma) for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. Subsequently, 2 µM DHR 123 (Sigma) or 10 µM H2DCFDA (Sigma) were added for 15 min, followed by washing. Subsequently, the neutrophils were stimulated with PMA (100 nM), B3501or CAP67 (both at a 1:5 neutrophil/yeast ratio), GXM (50 µg/mL) or GXMGal (50 µg/mL) for 15 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. The fluorescence intensity of the cells was analyzed using a spectramax reader at 485/538 nm (Molecular Devices).

Cytotoxicity assay

The neutrophils were incubated with various inhibitors in 96-well plates. Cell viability was tested using the CytoTox® Kit (Promega), which assesses the activity of lactate dehydrogenase released from damaged cells.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed using Graphpad 5.0 software. Paired comparisons between different groups were performed using Student's t test. Each experiment was performed at least 3 times on independent occasions. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Author Contributions

E.M.S., C.G.F.L., M.T.C.N. and J.D.B.R. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all figures; J.D.B.R., M.T.C.N., S.C.R., N.H., A.M. and D.D.R. conducted the experiments; C.G.F.L., G.A.D.R., E.M.S., A.M., D.D.R., L.M.P., J.O.P. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; C.G.F.L., G.A.D.R., E.M.S.; D.D.R. and M.P.N. analyzed the data and revised the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq), Rio de Janeiro State Science Foundation (FAPERJ), and Programa Institutos Nacionais de Ciência e Tecnologia (INCT), CNPq, Brazil. We thank Jorgete Logullo, Lindomar Miranda and Orlando Augusto Agrellos Filho (in memoriam) for helpful technical assistance. CGFD EMS AM NH JOP LMP SCR GADR are senior investigators from CNPq.

References

- Buchanan K. L. & Murphy J. W. What makes Cryptococcus neoformans a pathogen? Emerg Infect Dis 4, 71–83 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland E. E., Bernhardt P. & Casadevall A. Estimating the relative contributions of virulence factors for pathogenic microbes. Infect Immun 74, 1500–1504 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. C. & Kwon-Chung K. J. Complementation of a capsule-deficient mutation of Cryptococcus neoformans restores its virulence. Mol Cell Biol 14, 4912–4919 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromtling R. A., Shadomy H. J. & Jacobson E. S. Decreased virulence in stable, acapsular mutants of cryptococcus neoformans. Mycopathologia 79, 23–29 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherniak R., Jones R. G. & Reiss E. Structure determination of Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A-variant glucuronoxylomannan by 13C-n.m.r. spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res 172, 113–138 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherniak R., Valafar H., Morris L. C. & Valafar F. Cryptococcus neoformans chemotyping by quantitative analysis of 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of glucuronoxylomannans with a computer-simulated artificial neural network. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 5, 146–159 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monari C. et al. Differences in outcome of the interaction between Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan and human monocytes and neutrophils. Eur J Immunol 33, 1041–1051 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z. M. & Murphy J. W. Cryptococcal polysaccharides induce L-selectin shedding and tumor necrosis factor receptor loss from the surface of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest 97, 689–698 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monari C., Kozel T. R., Bistoni F. & Vecchiarelli A. Modulation of C5aR expression on human neutrophils by encapsulated and acapsular Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun 70, 3363–3370 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss C., Klutts J. S., Wang Z., Doering T. L. & Azadi P. The structure of Cryptococcus neoformans galactoxylomannan contains beta-D-glucuronic acid. Carbohydr Res 344, 915–920 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villena S. N. et al. Capsular polysaccharides galactoxylomannan and glucuronoxylomannan from Cryptococcus neoformans induce macrophage apoptosis mediated by Fas ligand. Cell Microbiol 10, 1274–1285 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi V., Wong B. & Newman S. L. Oxidative killing of Cryptococcus neoformans by human neutrophils. Evidence that fungal mannitol protects by scavenging reactive oxygen intermediates. J Immunol 156, 3836–3840 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond R. D., Root R. K. & Bennett J. E. Factors influencing killing of Cryptococcus neoformans by human leukocytes in vitro. J Infect Dis 125, 367–376 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papayannopoulos V., Metzler K. D., Hakkim A. & Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol 191, 677–691 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303, 1532–1535 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes-Costa A. B. et al. Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes induce and are killed by neutrophil extracellular traps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 6748–6753 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh T. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate a host defense response to human immunodeficiency virus-1. Cell Host Microbe 12, 109–116 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban C. F. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M. et al. Restoration of NET formation by gene therapy in CGD controls aspergillosis. Blood 114, 2619–2622 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns S. et al. Production of extracellular traps against Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro and in infected lung tissue is dependent on invading neutrophils and influenced by hydrophobin RodA. PLoS Pathog 6 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer D. J. et al. Extracellular fibrils of pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus gattii are important for ecological niche, murine virulence and human neutrophil interactions. PLoS One 5, e10978 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban C. F., Reichard U., Brinkmann V. & Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps capture and kill Candida albicans yeast and hyphal forms. Cell Microbiol 8, 668–676 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Human PAD4 regulates histone arginine methylation levels via demethylimination. Science 306, 279–283 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilsczek F. H. et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol 185, 7413–7425 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmers S., Teijaro J. R., Arandjelovic S. & Mowen K. A. PAD4-mediated neutrophil extracellular trap formation is not required for immunity against influenza infection. PLoS One 6, e22043 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybill J. R., Bocanegra R., Lambros C. & Luther M. F. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor therapy of experimental cryptococcal meningitis. J Med Vet Mycol 35, 243–247 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mednick A. J., Feldmesser M., Rivera J. & Casadevall A. Neutropenia alters lung cytokine production in mice and reduces their susceptibility to pulmonary cryptococcosis. Eur J Immunol 33, 1744–1753 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal B. H. et al. Aspergillus nidulans infection in chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 77, 345–354 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal B. H. & Romani L. R. Invasive aspergillosis in chronic granulomatous disease. Med Mycol 47 Suppl 1, S282–290 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzk N. & Papayannopoulos V. Molecular mechanisms regulating NETosis in infection and disease. Semin Immunopathol 35, 513–530 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner T. et al. The impact of various reactive oxygen species on the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Mediators Inflamm 2012, 849136 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartha F. & Henriques-Normark B. ETosis: a novel cell death pathway. Sci Signal 1, pe25 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P. et al. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. The Journal of experimental medicine 207, 1853–1862 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel C., McMaster W. R., Girard D. & Descoteaux A. Leishmania donovani promastigotes evade the antimicrobial activity of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Immunol 185, 4319–4327 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K. et al. Endocytosis of soluble immune complexes leads to their clearance by FcgammaRIIIB but induces neutrophil extracellular traps via FcgammaRIIA in vivo. Blood 120, 4421–4431 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd A. S., O'Brien X. M., Johnson C. M., Lavigne L. M. & Reichner J. S. An extracellular matrix-based mechanism of rapid neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Candida albicans. J Immunol 190, 4136–4148 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumby P. et al. Extracellular deoxyribonuclease made by group A Streptococcus assists pathogenesis by enhancing evasion of the innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 1679–1684 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M. J. et al. DNase Sda1 provides selection pressure for a switch to invasive group A streptococcal infection. Nat Med 13, 981–985 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiter K. et al. An endonuclease allows Streptococcus pneumoniae to escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr Biol 16, 401–407 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan J. T. et al. DNase expression allows the pathogen group A Streptococcus to escape killing in neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr Biol 16, 396–400 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinkernagel A. S. et al. The IL-8 protease SpyCEP/ScpC of group A Streptococcus promotes resistance to neutrophil killing. Cell Host Microbe 4, 170–178 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monari C. et al. A microbial polysaccharide reduces the severity of rheumatoid arthritis by influencing Th17 differentiation and proinflammatory cytokines production. J Immunol 183, 191–200 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M. J. Neutrophils in the pathogenesis and manifestations of SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7, 691–699 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessenbrock K. et al. Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat Med 15, 623–625 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnav V. V., Bacon B. E., O'Neill M. & Cherniak R. Structural characterization of the galactoxylomannan of Cryptococcus neoformans Cap67. Carbohydr. Res 306, 315–330 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimrichter L. et al. Self-aggregation of Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan is dependent on divalent cations. Eukaryot Cell 6, 1400–1410 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherniak R., Morris L. C., Anderson B. C. & Meyer S. A. Facilitated isolation, purification, and analysis of glucuronoxylomannan of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun 59, 59–64 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherniak R., Reiss E., Slodki M. E., Plattner R. D. & Blumer S. O. Structure and antigenic activity of the capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A. Mol Immunol. 17, 1025–1032 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M., Gilles K., Hamilton J. K., Rebers P. A. & Smith F. A colorimetric method for the determination of sugars. Nature 168, 167 (1951). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes-Costa A. B. et al. 3'-nucleotidase/nuclease activity allows Leishmania parasites to escape killing by neutrophil extracellular traps. Infect Immun 82, 1732–1740 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information