Abstract

AIM: To investigate the frequency and timing of post-partum chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation and identify its pre-partum predictors.

METHODS: Forty-one hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative chronic HBV infected pregnant women were prospectively evaluated between the 28th and the 32nd week of gestation. Subjects were re-evaluated at 3-mo intervals during the first post-partum year and every 6 mo during the following years. HBV DNA was determined using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (Cobas TaqMan HBV Test) with a lower detection limit of 8 IU/mL. Post-partum reactivation (PPR) was defined as abnormal alanine aminotransaminase (ALT) levels and HBV DNA above 2000 IU/mL.

RESULTS: Fourteen out of 41 women (34.1%) had pre-partum HBV DNA levels > 2000 IU/mL, 18 (43.9%) had levels < 2000 IU/mL and 9 (21.9%) had undetectable levels. Fourteen women were lost to follow-up (failure to return). PPR occurred in 8 of the 27 (29.6%) women evaluated, all within the first 6 mo after delivery (5 at month 3; 3 at month 6). Five of the 6 (83.3%) women with pre-partum HBV DNA > 10000 IU/mL exhibited PPR compared with 3 of the 21 (14.3%) women with HBV DNA < 10000 IU/mL (two with HBV DNA > 2000 and the third with HBV DNA of 1850 IU/mL), P = 0.004. An HBV DNA level ≥ 10000 IU/mL independently predicted post-partum HBV infection reactivation (OR = 57.02, P = 0.033). Mean pre-partum ALT levels presented a non-significant increase in PPR cases (47.3 IU/L vs 22.2 IU/L, respectively, P = 0.094).

CONCLUSION: In the present study, PPR occurred in approximately 30% of HBeAg-negative pregnant women; all events were observed during the first semester after delivery. Pre-partum HBV DNA level > 10000 IU/mL predicted PPR.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, Pregnancy, Reactivation, Post-Partum, Hepatitis B virus-DNA

Core tip: According to our prospective study, the post-partum reactivation of chronic hepatitis B occurs in approximately 30% of hepatitis B e antigen-negative women; all cases are observed during the first 6 mo after delivery. Among demographic, hematological, biochemical and viral characteristics, the only pre-partum parameter predictive for post-partum hepatitis B virus reactivation is whether the maternal viral load is greater than 10000 IU/mL between the 28th and the 32nd week of gestation.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in pregnancy is an important global health problem. Over 50% of the 350 million chronic HBV carriers acquire their infection perinatally, and the risk of progression to chronic infection is inversely proportional to the age at infection[1,2]. Women of childbearing age with chronic HBV infection remain a significant source of HBV transmission worldwide. Thus, the management of chronic HBV infection during pregnancy is essential to interrupt perinatal HBV transmission[3].

Several published reports and expert opinions conclude that the major risk factor for immunoprophylaxis failure is maternal HBV DNA levels during the third trimester of pregnancy[4-9]. Serum HBV DNA determination is suggested between weeks 28 and 32 of pregnancy to determine whether treatment with nucleoside or nucleotide analogues is needed in highly viremic women[6-9]. Moreover, the importance of maternal viremia has been clearly documented in the literature because it is positively associated with cord blood viremia, a parameter that seems to also affect pregnancy outcome[10,11].

Data concerning the effect of pregnancy on chronic HBV infection and HBV-related liver disease are limited. In general, there is usually no deterioration of HBV-related liver disease during pregnancy[3]. HBV is a non-cytopathic virus and the associated liver inflammation is mainly mediated by the host’s immune response. Moreover, because of pregnancy-induced immune mediated changes as well as pregnancy-induced plasma volume expansion, serum aminotransferase levels seem to remain within normal values, even in pregnant women with pre-existing chronic liver disease[12,13]. However, there are reports of severe HBV flares resulting in liver failure during the peripartum period, mainly in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive Asian women[14]. Although data from Europe concerning the clinical course of chronic HBV-infected Caucasian pregnant women in late pregnancy and early postpartum period are limited[15], there are no data on post-partum HBV reactivation among HBeAg-negative chronic HBV-infected women during long-term follow-up.

The aim of the study was to prospectively evaluate the frequency and timing of post-partum HBV reactivation appearance and to identify any pre-partum virological or hematological-biochemical predictive factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between January 2007 and January 2008, a total of 60 chronic HBV-infected pregnant women were evaluated between the 28th and the 32nd week of gestation. Namely, clinical examination, hematological, biochemical and serological tests were performed at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of “Elena Venizelou” Maternal and Perinatal Hospital of Athens, Greece. A total of 2.0 mL of serum was obtained from each woman with chronic hepatitis B and kept at -80 °C until further analyses. Viral load in a 0.5-mL sample was determined by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HBV Test, v2.0, lower detection limit: 8 IU/mL, Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Hepatitis B surface antigen, HBeAg, antibody to HBeAg, antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM/total), antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs), antibody to hepatitis C virus (HCV), antibody to hepatitis D virus (HDV) and antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were detected using commercially available enzyme immunoassays (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, United States). Routine hematological and biochemical tests were performed using automated techniques.

Pregnant women with acute hepatitis B, HBeAg-positive chronic infection, co-infections (HCV, HDV, and HIV), or any known pre-existing liver disease were excluded from the study. Additionally, women with known pregnancy-related complications (intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, HELLP syndrome, preeclampsia, placental hemorrhage, etc.), women taking medications (except for iron, folic acid, calcium and other vitamins or diet supplements), as well as those with known bacterial, fungal, parasitic or viral infections during pregnancy, were also excluded from the final analysis. Treatment and prophylaxis with nucleos(t)ide analogues were also considered as exclusion criteria. Finally, failure to complete at least a 6-mo post-partum follow-up period also resulted in exclusion from the study.

All chronic hepatitis B-infected women were prospectively clinically, virologically and biochemically evaluated after delivery. In particular, all women were evaluated virologically [quantitative serum HBV DNA test, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)] and biochemically [serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels] at the 3rd mo and the 6th mo of the post-partum period and then only biochemically (serum ALT levels) every 3 mo for the first post-partum year and every 6 mo for the following years. HBV DNA testing was repeated annually in those with ALT levels within the normal values proposed by our laboratory (< 35 IU/L). In those with abnormal serum ALT levels, HBV DNA was calculated immediately.

Post-partum HBV reactivation was defined as abnormal serum ALT levels and serum HBV DNA levels above 2000 IU/L, irrespective of the pre-partum levels.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Study protocol was in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the “Elena Venizelou” Hospital Ethics Committee.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD unless stated otherwise. Because of the small number of patients, continuous variable differences between the groups presenting or not with HBV reactivation were evaluated as independent samples using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical variable differences between the HBV reactivation and no-reactivation groups were evaluated using the χ2 Fisher’s exact test. The Kaplan-Meier plot was used to estimate cumulative hazard and event free time for post-partum HBV reactivation for patients according to their pre-partum serum HBV DNA levels (< or ≥ than 10000 IU/mL); data regarding timing of events were interval censored.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis (enter method with forced entry of independent variables) was performed to further evaluate the association of HBV DNA levels ≥ 10000 IU/mL with post-parturm HBV reactivation after adjustment for the percentage of polynuclear cells and lymphocytes within the total white blood cell count.

A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19 for MacOS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, United States).

RESULTS

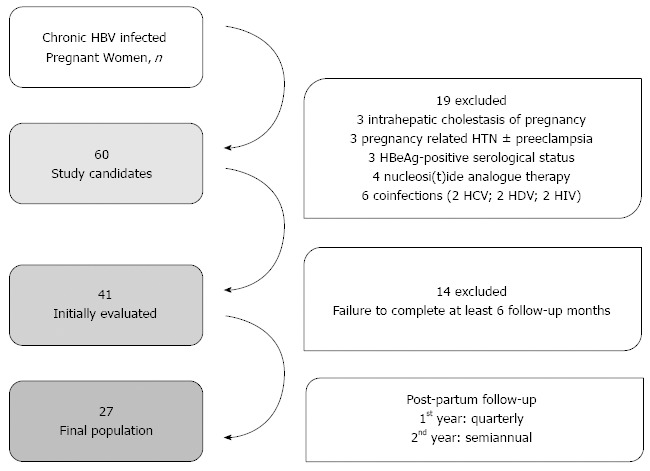

A total of 60 women were initially considered to be candidates for the study. Nineteen women were excluded from the final analysis per the study exclusion criteria. The flow chart diagram of the study population is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart diagram of the study population. HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; HDV: Hepatitis D virus.

Among the remainder of the 41 chronically infected pregnant women, 32/41 (78.1%) were HBV DNA-positive whereas 9/41 (21.9%) had undetectable HBV DNA levels in the pre-partum period. In particular, 18/41 (43.9%) women had detectable HBV DNA levels that were lower than 2000 IU/mL, and 14/41 (34.1%) had HBV DNA levels above 2000 IU/mL. Importantly, in a significant proportion of women with viremia above 2000 IU/mL, the HBV DNA levels were elevated more than >10000 IU/mL during the third trimester.

Fourteen women failed to follow-up after delivery and were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 27 women who were evaluated were followed for a period of 6 to 60 mo.

Eight out of the 27 (29.6%) HBeAg-negative chronic HBV-infected women showed a post-partum ALT flare with concomitant elevation in viremia above 2000 IU/mL. It is also important to note that all HBV reactivation cases were documented during the first 6 mo after delivery (5 cases were observed during the third month; the remaining 3 cases during the sixth month of follow-up). Women in whom HBV reactivation was not observed during this early post-partum period did not present an event during the follow-up period (17.6 ± 3.5 mo).

Age (27 ± 9.4 years vs 28.4 ± 5.8 years, P = 0.147), weight (70.8 ± 16.7 kg vs 69.2 ± 11.7 kg, P = 0.283), height (1.64 ± 0.05 m vs 1.64 ± 0.05 m, P = 1.00), body mass index (26.1 ± 5.3 kg/m2 vs 25.6 ± 3.9 kg/m2, P = 0.849), as well as weight gain during pregnancy (10.8 ± 0.83 kg vs 11.5 ± 3.59 kg, P = 0.594), were comparable among the women who exhibited HBV reactivation and those who did not. Detailed pre-partum hematological, biochemical and virological characteristics of the HBV-reactivation as well as no-reactivation cases are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pre-partum (3rd trimester of pregnancy) hematological, biochemical and virological characteristics of chronic hepatitis B virus-infected patients

| Overall population | No-reactivation | HBV-reactivation | P value | |

| Patients, n | 27 | 19 | 8 | |

| Hct | 35.9% ± 4.0% | 35.1% ± 3.0% | 37.8% ± 5.6% | 0.312 |

| Hb, g/dL | 12.0 ± 1.4 | 11.6 ± 1.1 | 12.7 ± 1.8 | 0.207 |

| WBC, n | 8.677 ± 2.835 | 8.835 ± 3.122 | 8.308 ± 2.231 | 0.444 |

| PNL | 67.3% ± 10.3% | 68.8% ± 11.0% | 62.3% ± 6.2% | 0.008 |

| LYMPHO | 24.3% ± 9.1% | 23.1% ± 9.8% | 28.5% ± 5.2% | 0.035 |

| MONO | 5.9% ± 1.8% | 5.6% ± 1.9% | 6.8% ± 1.0% | 0.192 |

| PLT, /103 | 209 ± 41 | 212 ± 45 | 202 ± 31 | 0.968 |

| AST, IU/L | 27.6 ± 14.7 | 23.8 ± 6.9 | 35.3 ± 22.8 | 0.585 |

| ALT, IU/L | 30.6 ± 28.2 | 22.2 ± 13.0 | 47.3 ± 42.4 | 0.094 |

| GGT, IU/L | 12.8 ± 6.8 | 14.2 ± 7.2 | 9.8 ± 5.4 | 0.210 |

| LDH, IU/L | 203.8 ± 85.6 | 180.6 ± 79.5 | 250.2 ± 88.8 | 0.214 |

| TBIL, mg/dL | 0.51 ± 0.29 | 0.53 ± 0.34 | 0.47 ± 0.19 | 1.000 |

| DBIL, mg/dL | 0.22 ± 0.20 | 0.26 ± 0.24 | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 0.462 |

| TPROT, g/dL | 6.67 ± 0.58 | 6.84 ± 0.48 | 6.23 ± 0.66 | 0.138 |

| ALB, g/dL | 3.59 ± 0.39 | 3.71 ± 0.32 | 3.25 ± 0.39 | 0.078 |

| GLOB, g/dL | 3.07 ± 0.39 | 3.10 ± 0.42 | 2.97 ± 0.34 | 0.661 |

| HBV DNA ≥ 10000 IU/mL, n (%) | 6 (22.2) | 1 (5.2) | 5 (62.5) | 0.004 |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus; Hct: Hematocrit; Hb: Hemoglobin; WBC: White blood cells; PNL: Polynuclear cells; LYMPHO: Lymphocytes; MONO: Monocytes; PLT: Platelets; AST: Aspartate transaminase; ALT: Alanine transaminase; GGT: Gamma-glutamate transpeptidase; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; TBIL: Total bilirubin; DBIL: Direct bilirubin; TPROT: Total protein; ALB: Albumin; GLOB: Globulins.

The pre-partum peripheral white blood cell evaluation of the HBV-reactivation group revealed a lower percentage of neutrophils and higher percentage of lymphocytes (62.3% ± 6.2% vs 68.8% ± 11%, P = 0.008 and 28.5% ± 5.2% vs 23.1% ± 9.8%, P = 0.035, respectively) than in the no-reactivation group.

The women who exhibited post-partum HBV reactivation had comparable absolute lymphocyte counts (2099 ± 230 vs 1862 ± 107, P = 0.382) and exhibited a tendency toward lower absolute neutrophil counts (4582 ± 381 vs 6278 ± 710, P = 0.079) during the third trimester of pregnancy compared to women without HBV reactivation. The pre-partum serum aspartate transaminase, ALT and gamma-glutamate transpeptidase levels were comparable among the HBV-reactivation and no-reactivation cases, as shown in Table 1. It is important to note that the pre-partum serum ALT levels were within the normal range of our laboratory in the vast majority of patients, except for two women with HBV DNA levels of 40000 and 45000 IU/L, who had serum ALT levels of 120 and 95 IU/L, respectively. Both of them continued to have abnormal ALT and high HBV DNA levels during the early post-partum period (at month 3 of follow-up).

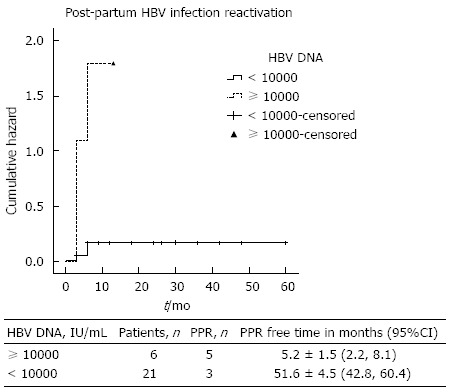

On one hand, none of the chronic HBV-infected pregnant women with undetectable HBV DNA levels during the pre-partum period presented HBV-reactivation. On the other hand, the majority of HBV-reactivation cases (5/8 women, 62.5%) had pre-partum HBV DNA levels above 10000 IU/mL, and the remaining three reactivation cases exhibited serum HBV DNA levels of 8620, 2550 and 1850 IU/mL. In the multivariate analysis, after adjustment for lymphocyte and neutrophil blood count, pre-partum serum HBV DNA levels above 10000 IU/mL continued to significantly predict HBV reactivation. Using the cut-off of 10000 IU/mL for pre-partum HBV DNA levels, it seems feasible to discriminate HBV-reactivation cases from non-reactivation cases (P = 0.004), as shown in Figure 2 and Table 1. Moreover, HBV DNA levels ≥ 10000 IU/mL independently predicted post-partum HBV infection reactivation after adjusting for the percentage (within total white blood cells) of neutrophils and lymphocytes (OR = 57.02, P = 0.033).

Figure 2.

Cumulative Hazard plot for post-partum hepatitis B virus reactivation. HBV DNA: Hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; PPR: Post-partum reactivation.

Five out of the 8 women with HBV reactivation initiated treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues (three with tenofovir, one with entecavir and one with telbivudine), achieving long-term biochemical (normal ALT values) and virological (undetectable HBV DNA levels) responses. It is important to note that the remaining three women with HBV reactivation who declined treatment because of continuing lactation were followed up and had spontaneous disease remission. In 2 of these 3 women, HBV DNA decreased < 2000 IU/mL and ALT to normal levels in the following months of follow-up (36 and 24 mo, respectively), and only one had normal ALT levels and HBV DNA levels between 2000-10000 IU/mL during 24 mo of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

During pregnancy, several alterations in immune status allow women to tolerate the genetically different fetal tissues. Recently, there has been an increasing interest in the aspects and the possible mechanisms of a specific immunoregulation during pregnancy[15,16]. In general, a shift in the Th1-Th2 balance toward a Th2 response with increased amounts of regulatory T-cells is observed. This could also explain the tolerance against infectious agents, such as HBV. Pregnancy-induced endocrine and immune changes result in elevation of HBV DNA levels and normalization of liver tests between the first, second and third trimester of pregnancy in chronic HBV-infected women[17]. Moreover, the well-documented pregnancy-related plasma volume expansion and serum dilution[12,13], especially during the third trimester of pregnancy, might significantly affect serum HBV DNA levels as well as serum aminotransferase levels. Therefore, both parameters may be underestimated during late pregnancy. All these changes in immune status recover after delivery and the mother’s immune system fully restores its function, a phenomenon that could be responsible for the observed post-partum exacerbation of chronic infections and autoimmune diseases[15,16].

Severe HBV reactivation cases causing fulminant liver failure during pregnancy have been reported in the literature. These cases mainly occurred in Asian HBeAg-positive or negative chronic HBV-infected pregnant women during the 2nd or the 3rd trimester of pregnancy[14], as well as in HBeAg-positive Caucasian women with high HBV DNA levels[18]. There is only one retrospective cohort study concerning the exacerbation of chronic HBV infection after delivery in a mixed population of 38 HBeAg-positive and negative chronic HBV-infected women[19]. In that study, a significant increase of liver disease activity was observed in 45% of cases after delivery, irrespective of pre-partum serum ALT or HBV DNA levels or the HBeAg status. It is important to note that 63% of the patients of the study of ter Borg et al[19] were HBeAg-positive and 45% were categorized in the immunotolerant phase of chronic HBV infection. Our study is the only study that specifically addresses the post-partum clinical outcome of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B pregnant women. This population, characterized by lower serum HBV-DNA levels compared to their HBeAg-positive counterparts, represent the majority of chronic patients of reproductive age in Greece[20], as well as in other Mediterranean and Balkan countries. We found that approximately one-fifth of the study population (21.9%) presented undetectable serum HBV DNA levels during the third trimester of pregnancy using a sensitive PCR assay and that about one-third (34.1%) of the HBeAg-negative chronic HBV-infected pregnant women exhibited HBV DNA levels above 2000 IU/mL. These findings are consistent with previous studies in HBeAg-negative chronic HBV-infected pregnant women[11,20], among whom a considerable number of inactive carriers may exist. Distinguishing inactive carriers from chronic hepatitis B patients among the total HBeAg-negative chronic HBV-infected population is very difficult using only biochemical and virological parameters. In general, the differential diagnosis of HBeAg-negative chronic HBV-infected patients should be initially based on the combination of ALT activity and serum HBV-DNA levels. Patients who present with HBV-DNA levels above 2000 IU/mL almost always have elevated ALT values, as opposed to patients with lower HBV DNA levels who can be either inactive carriers or chronic hepatitis B cases[21]. Pregnancy-induced immune changes, pregnancy-related plasma volume expansion and serum dilution during the third trimester seem to further impair the differential diagnosis, based on virological and biochemical values. Only 2 out of 8 women with post-partum HBV reactivation had abnormal pre-partum ALT levels, whereas the majority of reactivation cases exhibited pre-partum HBV-DNA levels above 10000 IU/mL. Only one woman with HBV DNA < 2000 IU/mL and no women with undetectable pre-partum HBV DNA levels exhibited post-partum HBV reactivation.

Described early on by Rudolf Virchow, the physiologic leucocytosis of the third trimester of a normal, uncomplicated pregnancy that normalized readily after delivery represents a well-known phenomenon[22-24]. Additionally, it has been reported that pregnant women present lower lymphocyte counts than non-pregnant women[25]. Lymphocyte proliferation and activation is a well-known phenomenon in patients with viral infections[26]. In our study, women who exhibited post-partum HBV reactivation had a significant difference in the percentage of neutrophils (62.3% ± 6.2% vs 68.8% ± 11%; P = 0.008) and lymphocytes (28.5% ± 5.2% vs 23.1% ± 9.8%; P = 0.035) among total white blood cells of the peripheral blood observed during the pre-partum period compared to non-reactivation cases. Moreover, the absolute lymphocyte count was comparable and the absolute neutrophil count was lower in the reactivation cases than in the non-reactivation cases. Although non-significant, this finding is most likely because of the major effect of pregnancy per se on the absolute neutrophil count. It may be that the level of maternal viremia affects the well-known pregnancy-induced leucocytosis, as well as the left shift in myeloid-neutrophilic lineage; a finding that needs further investigation in large scale studies.

Nevertheless, our present study has some limitations, such as the relatively small number of study subjects, of which a significant percentage were excluded from the final analysis because of either the exclusion criteria of the study or being lost to follow-up. It is well-known that being lost to follow-up frequently occurs even in large, randomized controlled trials of chronic HBV-infected pregnant women. Despite these limitations, we believe that the study population is able to represent the total HBeAg-negative chronic HBV-infected Caucasian population, prospectively examined in respect to post-partum viral reactivation, taking into account pre-partum virological, biochemical and hematological data.

In conclusion, post-partum HBV reactivation occurs in approximately 30% of HBeAg-negative chronic HBV-infected women and all events are recorded in the first semester after delivery. Pre-partum HBV DNA levels above 10000 IU/mL appear to be a significant predictor of post-partum HBV reactivation.

COMMENTS

Background

Perinatal transmission of chronic hepatitis B remains an important source of hepatitis B virus (HBV) worldwide, but the data concerning the effect of pregnancy on chronic HBV infection and HBV-related liver disease are limited. Additionally, the frequency and the timing of post-partum hepatitis B reactivation among hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative women are not fully elucidated.

Research frontiers

During pregnancy, there is usually no deterioration of HBV-related liver disease. On the contrary, there are reports of severe HBV flares resulting in liver failure during the peripartum period, mainly in Asian women with the HBeAg-positive form of chronic HBV infection. In this study, the authors evaluate the frequency and timing of post-partum HBV reactivation, as well as its predictive factors.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Recent reports have highlighted the importance of maternal HBV DNA levels during the third trimester of pregnancy as the major risk factor for immunoprophylaxis failure. This is the first study demonstrating that post-partum HBV reactivation is observed in approximately 30% of HBeAg-negative women, all during 6 mo after delivery and mainly in women with serum HBV DNA > 10000 IU/mL during the third trimester of gestation.

Applications

The knowledge of timing and risk factors of chronic hepatitis B reactivation helps clinicians optimize the measurements of HBV DNA during pregnancy, modify the immunoprophylaxis of infants, and monitor women after delivery.

Terminology

Chronic hepatitis B may present either in HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative form. Without immunoprophylaxis, perinatal transmission occurs in 5% to 20% of infants born to HBeAg-negative mothers and in 70% to 90% of infants born to HBeAg-positive mothers. Maternal viral load in the third trimester is correlated with perinatal transmission.

Peer review

Data concerning post-partum reactivation of chronic HBV infection among HBeAg-negative women are rare. This study evaluated the frequency and timing of the appearance of post-partum HBV reactivation and identified its pre post-partum virological and biochemical predictors. The results will help clinicians optimize HBV management during pregnancy and identify women at risk for HBV reactivation after delivery.

Footnotes

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: July 5, 2014

First decision: July 21, 2014

Article in press: October 15, 2014

P- Reviewer: Malnick S, Puoti C, Parvez MK, Ye XG S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Alter MJ. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:39–46. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavanchy D. Worldwide epidemiology of HBV infection, disease burden, and vaccine prevention. J Clin Virol. 2005;34 Suppl 1:S1–S3. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(05)00384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piratvisuth T. Optimal management of HBV infection during pregnancy. Liver Int. 2013;33 Suppl 1:188–194. doi: 10.1111/liv.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinha S, Kumar M. Pregnancy and chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:31–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bzowej NH. Hepatitis B Therapy in Pregnancy. Curr Hepat Rep. 2010;9:197–204. doi: 10.1007/s11901-010-0059-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchanan C, Tran TT. Management of chronic hepatitis B in pregnancy. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin JI, Namgung R, Park MS, Park KI, Lee C. Immunoprophylaxis failure against vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus: what is the mechanism and do other factors also play a role? Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:489–490. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0499-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonas MM. Hepatitis B and pregnancy: an underestimated issue. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiseman E, Fraser MA, Holden S, Glass A, Kidson BL, Heron LG, Maley MW, Ayres A, Locarnini SA, Levy MT. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus: an Australian experience. Med J Aust. 2009;190:489–492. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elefsiniotis IS, Papadakis M, Vlachos G, Vezali E, Tsoumakas K, Saroglou G, Antsaklis A. Presence of HBV-DNA in cord blood is associated with spontaneous preterm birth in pregnant women with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Intervirology. 2011;54:300–304. doi: 10.1159/000321356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elefsiniotis IS, Tsoumakas K, Papadakis M, Vlachos G, Saroglou G, Antsaklis A. Importance of maternal and cord blood viremia in pregnant women with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:182–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacq Y, Zarka O, Bréchot JF, Mariotte N, Vol S, Tichet J, Weill J. Liver function tests in normal pregnancy: a prospective study of 103 pregnant women and 103 matched controls. Hepatology. 1996;23:1030–1034. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakim-Fleming J, Zein NN. The liver in pregnancy: disease vs benign changes. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72:713–721. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.72.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen G, Garcia RT, Nguyen N, Trinh H, Keeffe EB, Nguyen MH. Clinical course of hepatitis B virus infection during pregnancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:755–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scherjon S, Lashley L, van der Hoorn ML, Claas F. Fetus specific T cell modulation during fertilization, implantation and pregnancy. Placenta. 2011;32 Suppl 4:S291–S297. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burlingham WJ. A lesson in tolerance--maternal instruction to fetal cells. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1355–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr0810752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Söderström A, Norkrans G, Lindh M. Hepatitis B virus DNA during pregnancy and post partum: aspects on vertical transmission. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:814–819. doi: 10.1080/00365540310016547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singhal A, Kanagala R, Jalil S, Wright HI, Kohli V. Chronic HBV with pregnancy: reactivation flare causing fulminant hepatic failure. Ann Hepatol. 2011;10:233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ter Borg MJ, Leemans WF, de Man RA, Janssen HL. Exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B infection after delivery. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elefsiniotis IS, Glynou I, Brokalaki H, Magaziotou I, Pantazis KD, Fotiou A, Liosis G, Kada H, Saroglou G. Serological and virological profile of chronic HBV infected women at reproductive age in Greece. A two-year single center study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;132:200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papatheodoridis GV, Manesis EK, Manolakopoulos S, Elefsiniotis IS, Goulis J, Giannousis J, Bilalis A, Kafiri G, Tzourmakliotis D, Archimandritis AJ. Is there a meaningful serum hepatitis B virus DNA cutoff level for therapeutic decisions in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection? Hepatology. 2008;48:1451–1459. doi: 10.1002/hep.22518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lurie S, Rahamim E, Piper I, Golan A, Sadan O. Total and differential leukocyte counts percentiles in normal pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;136:16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roehrl MH, Wang JY. Immature granulocytes in pregnancy: a story of Virchow, anxious fathers, and expectant mothers. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:307–308. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman JE, Yuan M, Anderson L, Howie F, Harold G, Young A, Jordan F, McInnes I, Harnett MM. Effect of prolonged in vivo administration of progesterone in pregnancy on myometrial gene expression, peripheral blood leukocyte activation, and circulating steroid hormone levels. Reprod Sci. 2011;18:435–446. doi: 10.1177/1933719110395404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller EM. Changes in serum immunity during pregnancy. Am J Hum Biol. 2009;21:401–403. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehermann B. Chronic infections with hepatotropic viruses: mechanisms of impairment of cellular immune responses. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:152–160. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]