Abstract

AIM: To determine the effect of discontinuing non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on recurrence in long-term follow-up patients with colonic diverticular bleeding (CDB).

METHODS: A cohort of 132 patients hospitalized for CDB examined by colonoscopy was prospectively enrolled. Comorbidities, lifestyle, and medications (NSAIDs, low-dose aspirin, antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, acetaminophen, and corticosteroids) were assessed. After discharge, patients were requested to visit the hospital on scheduled days during the follow-up period. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate recurrence.

RESULTS: Median follow-up was 15 mo. The probability of recurrence at 1, 6, 12, and 24 mo was 3.1%, 19%, 27%, and 38%, respectively. Of the 41 NSAID users on admission, 26 (63%) discontinued NSAID use at discharge. Many of the patients who could discontinue NSAIDs were intermittent users, and could be switched to alternative therapies, such as acetaminophen or an antiinflammatory analgesic plaster. The probability of recurrence at 12 mo was 9.4% in discontinuing NSAID users compared with 77% in continuing users (P < 0.01, log-rank test). The hazard ratio for recurrence in the discontinuing NSAIDs users was 0.06 after adjusting for age > 70 years, right-sided diverticula, history of hypertension, and hemodialysis. No patients developed cerebrocardiovascular events during follow-up.

CONCLUSION: There is a substantial recurrence rate after discharge among patients hospitalized for diverticular bleeding. Discontinuation of NSAIDs is an effective preventive measure against recurrence. This study provides new information on risk reduction strategies for diverticular bleeding.

Keywords: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, Drug withdrawal, Diverticular hemorrhage, Hemodialysis, Antithrombotic drugs

Core tip: The probability of recurrence of diverticular bleeding at 1, 12, and 24 mo was 3.1%, 27%, and 38%, respectively. Of the 41 non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) users on admission, 26 (63%) discontinued NSAID use at discharge. The probability of recurrence at 12 mo was 9.4% in discontinuing NSAID users compared with 77% in continuing users (P < 0.01, log-rank test). The hazard ratio for recurrence in the discontinuing NSAIDs users was 0.06 after adjusting for age > 70 years, right-sided diverticula, history of hypertension, and hemodialysis. No patients developed cerebrocardiovascular events during follow-up. This study provides new information on risk reduction strategies for diverticular bleeding.

INTRODUCTION

Colonic diverticular bleeding (CDB) is the most common cause of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), representing approximately 40% of cases[1]. A significant proportion of patients with CDB experience severe bleeding and receive emergency treatment with resuscitative measures, possibly because of their advanced age, use of antithrombotic agents, or comorbidities[2-4]. Even though intensive management of CDB is successful during the hospital stay, following discharge, patients are at high risk of recurrent bleeding, which has been reported at a rate of 14%-43%[3,5-7]. As a result, patients often undergo frequent examinations, rehospitalization, and a consequent decrease in quality of life.

Risk reduction is an important clinical issue because no preventive therapy for recurrence is currently available for LGIB, such as proton-pump inhibitors used for the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB)[8]. Withdrawal of aspirin was recently reported to significantly reduce UGIB recurrence[9]. In LGIB, particularly CDB, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is a significant risk factor for recurrence[2,10,11], but the risks and benefits of their discontinuation on CDB have not been examined.

We previously conducted a study on the recurrence risk of CDB[5], but the retrospective investigation included biases that likely led to exposure variables being missed. Furthermore, it was unknown whether antithrombotic agents were continued, and follow-up was not conducted in a systematic manner. The present study builds upon our previous work by focusing on multiple risk factors for CDB, prospective follow-up of newly diagnosed cases, and detailed assessment of medications. The objectives of this study were to identify the risk factors associated with the recurrence of CDB after discharge, and to evaluate the effect of discontinuing NSAIDs on rebleeding risk over long-term follow-up.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Patients admitted to our hospital for overt LGIB between September 2009 and October 2013 and examined at the endoscopy unit of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM) were enrolled. Patients from a previous study cohort[12], a newly diagnosed cohort (approval No. 750), and a randomized trial cohort (approval No. 765) were prospectively followed after discharge. Inclusion criteria were: (1) > 18 years old; (2) Japanese nationality; (3) overt LGIB examined within 1 wk of onset; and (4) being managed in hospital. Exclusion criteria were: (1) no informed consent provided; (2) not independent in activities of daily living; (3) not undergoing colonoscopy; (4) LGIB due to causes other than CDB; and (5) barium impaction therapy in the randomized controlled trial (approval No. 765). All inclusion and exclusion criteria were fulfilled before patients were enrolled. The NCGM is a large emergency hospital, with 900 beds, located in metropolitan Tokyo, Japan. All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The institutional review board at the NCGM approved this study (approval No. 810), and all clinical procedures conformed to Japanese and International ethical guidelines (Declaration of Helsinki).

Exposure variables

Patients were asked about their lifestyle habits, medications, and comorbidities in a face-to-face interview on the pre-colonoscopy day.

Medication: The questionnaire survey form asked about the use of 9 kinds of NSAIDs, 2 kinds of low-dose aspirin, 10 other antiplatelet agents, 3 anticoagulants, acetaminophen, and oral corticosteroids. The questionnaire included photographs of all of these oral drugs, which are approved in Japan. Use of a medication was defined as oral administration within 1 mo of the interview. During hospitalization, low-dose aspirin, other antiplatelet drugs, and anticoagulants were temporarily stopped or other bridging drugs given whenever possible after consulting a cerebrocardiovascular specialist. Low-dose aspirin and other antiplatelet agents were resumed after hemostasis before discharge. Also, NSAIDs were temporarily stopped on admission and prescribed during hospitalization only on the advice of an orthopedist or rheumatology specialist. We suggested NSAID withdrawal to those who were intermittent users and to those who were suitable for alternative therapy such as acetaminophen, an antiinflammatory analgesic plaster, antigout drugs, antirheumatic drugs, or corticosteroids.

Comorbidities: Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cerebrocardiovascular disease, chronic liver disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) were assessed. A history of cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, myocardial infarction, or angina pectoris was considered cerebrocardiovascular disease. CKD was considered present in patients on hemodialysis. Chronic liver disease included chronic viral hepatitis and alcoholic liver disease.

Diagnostic criteria of colonic diverticular bleeding

An electronic high-resolution video endoscope (model CFH260; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) was used after spontaneous cessation of bleeding. CDB was defined as either definite or presumptive on the basis of colonoscopy with multidetector computed tomography (MDCT)[13,14]. Definitive diagnosis was based on colonoscopic visualization of colonic diverticula with stigmata of recent hemorrhage such as active bleeding, adherent clot, or visible vessel[13,14]. A presumptive diagnosis was based on MDCT visualization of the extravasation of contrast medium in colonic diverticula and colonoscopy showing (1) a potential bleeding site in an area of positive MDCT findings; (2) fresh blood localized to colonic diverticula in the presence of a potential bleeding source on complete colonoscopy; or (3) bright red blood in the rectum confirmed by objective color testing and colonoscopy demonstrating a single potential bleeding source in the colon, complemented by negative upper endoscopy, or negative capsule endoscopy[13,14]. Patients in whom the bleeding source was identified received endoscopic treatment such as clipping or endoscopic ligation.

Follow-up and rebleeding

After discharge, all patients were requested to visit the hospital in the case of bloody stools or on a scheduled day within the first month and then every three months during the observation and follow-up periods. Telephone interviews were conducted with patients who did not visit the hospital on scheduled days, and a hospital visit was recommended. Rebleeding was defined as a significant amount of fresh bloody or wine-colored stools (> 200 mL) during the follow-up period and was evaluated by both anoscopy and MDCT within 12 h of onset. Clinically suspected rebleeding should prompt further colonoscopy when possible, but no routine second-look colonoscopy was performed when rebleeding occurred during hospitalization or within 1 mo of discharge. Colonoscopy was performed to confirm rebleeding and determine the need for intervention when frequent or massive bleeding occurred along with unstable vital signs, systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg or pulse ≥ 110 beats/min, and a non-response to ≥ 2 units of transfused blood during a 24-h period. We distinguished between rebleeding and remaining blood from the index bleeding episode.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was rebleeding due to CDB. The secondary outcome was a cerebrocardiovascular or thrombotic event during the follow-up period. Patients lost to follow-up or death were censored at the time of their last visit. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the recurrence of CDB at 1, 6, 12, and 24 mo after discharge. Risk factors and the effect of NSAID withdrawal on rebleeding were analyzed using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to analyze the independent risk factors for rebleeding by considering factors significant (P < 0.1) in the log-rank test and adjusting for factors such as age > 70 years and hypertension, as previously reported[5-7].

A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 10 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States).

RESULTS

Participants

During the study period, 337 patients were admitted to our hospital for acute LGIB. After exclusion, 132 patients with CDB were enrolled in this study. Baseline characteristics at discharge are shown in Table 1. Diverticula were located predominantly in the bilateral colon in 48%, in the right side in 32%, and in the left side in 20% of cases. Of these, 17% (23/132) had colonoscopic evidence of stigmata of recent hemorrhage diverticula and were treated by endoscopic procedures during hospitalization, in which 37 patients (28%) received a mean transfusion of 8 units of packed red blood cells.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort (n = 132) n (%)

| Characteristic | Value |

| Mean age (mean ± SD), yr | 70 ± 12 |

| Age > 70 yr | 70 (53) |

| Sex, male | 87 (66) |

| Anatomical distribution of diverticula | |

| Right-sided type | 42 (32) |

| Left-sided typ | 27 (20) |

| Bilateral type | 63 (48) |

| Definite diagnosis (stigmata of recent hemorrhage) | 23 (17) |

| Presumptive diagnosis | 109 (83) |

| Transfusion requirement during hospitalization | 37 (28) |

| Mean units of transfused blood per patient1 ± SD | 8.0 ± 6.0 |

| Current drinker | 126 (95) |

| Current smoker | 36 (27) |

| NSAID2 users on admission | 41 (27) |

| Discontinuing NSAID users at discharge | 26 (20) |

| Continuing NSAID users at discharge | 15 (11) |

| Low-dose aspirin2 users on admission | 29 (22) |

| Low-dose aspirin users at discharge | 29 (22) |

| Non-aspirin antiplatelet2 users on admission | 27 (21) |

| Non-aspirin antiplatelet users at discharge | 27 (21) |

| Anticoagulant2 users on admission | 9 (6.8) |

| Anticoagulant users at discharge | 9 (6.8) |

| Acetaminophen users on admission | 2 (1.5) |

| Acetaminophen users at discharge | 13 (9.9) |

| Corticosteroid users on admission | 4 (3.0) |

| Corticosteroid users at discharge | 5 (3.3) |

| Hypertension | 83 (63) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 (20) |

| Dyslipidemia | 29 (22) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 33 (25) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2 (1.5) |

| Chronic liver disease | 5 (3.8) |

| Hemodialysis | 7 (5.3) |

Analysis of patients who received transfusion.

Non-selective NSAIDs included loxoprofen, diclofenac, naproxen, etodolac, zaltoprofen, meloxicam, lornoxicam, and celecoxib (n = 3). Distribution type was defined as follows: right-sided, involving the transverse or proximal colon; left-sided, involving the descending or distal colon; or bilateral, involving the entire colon. Low-dose aspirin included enteric-coated aspirin (100 mg) and buffered aspirin (81 mg). Non-aspirin antiplatelet agents included ticlopidine, clopidogrel, cilostazol, dipyridamole, sarpogrelate hydrochloride, ethyl icosapentate, dilazep, limaprost, and beraprost. Anticoagulants included warfarin and dabigatran etexilate. NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Among the patients using NSAIDs on admission (n = 41), 26 (63%) discontinued NSAID use. Many patients who could withdraw NSAIDs were intermittent users (n = 23), and could be switched to alternative therapies included acetaminophen (n = 11), an antiinflammatory analgesic plaster (n = 10), narcotic analgesics (n = 2), antigout drugs (n = 3), anti-rheumatic drugs (n = 1), and corticosteroids (n = 1), while the remaining patients (n = 7) took nothing. Some of these 26 patients took more than one of these drugs. No patients were taking NSAIDs for cardiovascular disease. Fifteen patients (11%) on NSAIDs and 13 patients (8.5%) on acetaminophen continued to take them after discharge. No patients on low-dose aspirin, non-aspirin antiplatelet agents, or corticosteroids discontinued use or started taking them during the follow-up period (Table 1).

The most common comorbidities were hypertension (63%), cardiovascular disease (25%), dyslipidemia (22%), diabetes mellitus (20%), hemodialysis (5.3%), chronic liver disease (3.8%), and cerebrovascular disease (1.5%) (Table 1).

Rebleeding outcomes

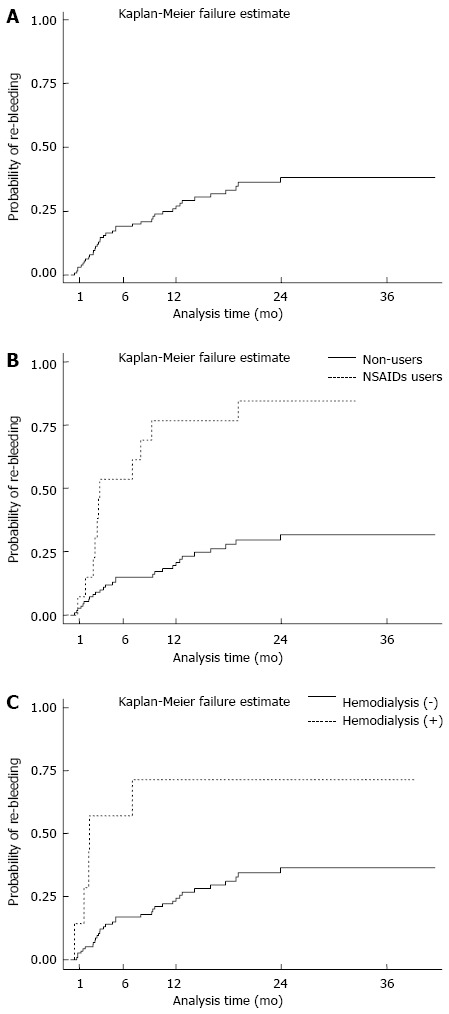

After discharge, 39 patients (30%) experienced rebleeding with a mean follow-up of 15 ± 13 mo. The probability of rebleeding was 3.1% at 1 mo, 19% at 6 mo, 27% at 12 mo, and 38% at 24 mo (Figure 1A). No patients required angiographic embolization or surgical resection within the follow-up period.

Figure 1.

Probability of bleeding recurrence during the follow-up period (n = 132). A: Incidence of rebleeding with a mean follow-up period of 15 mo; B: Probability of rebleeding was significantly higher in the [non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) group than in the non-NSAID group (P < 0.01)]; C: Probability of rebleeding was significantly higher in the hemodialysis group than in the non-hemodialysis group (P < 0.01).

Log-rank tests revealed NSAID use and hemodialysis as significant risk factors for rebleeding, while the other factors were not found to be significant (Table 2). Patients without right-sided diverticula had a risk of rebleeding, but this did not reach statistical significance (Table 2). The probability of rebleeding was 2.6% (95%CI: 0.86%-8.0%) at 1 mo and 21% (95%CI: 14%-30%) at 12 mo in non-NSAID users, and 7.1% (95%CI: 1.0-41) at 1 mo and 77% (95%CI: 52-94) at 12 mo in NSAID users (Figure 1B). The probability of rebleeding was 2.5% (95%CI: 1.0-7.6) at 1 mo and 24% (95%CI: 17-34) at 12 mo in non-hemodialysis patients, and 14% (95%CI: 2.1%-67%) at 1 mo and 71% (95%CI: 39%-96%) at 12 mo in hemodialysis patients (Figure 1C). Multivariate analysis revealed NSAID use and hemodialysis as independent risk factors for rebleeding (Table 3).

Table 2.

Risk factors for rebleeding after discharge on univariate analysis (n = 132)

| Factor | Non-rebleeding/rebleeding | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P |

| Age > 70 yr | 45 (48)/25 (64) | 1.6 (0.83-3.1) | 0.15 |

| Sex, male | 59 (63)/28 (72) | 1.1 (0.57-2.3) | 0.70 |

| Anatomical distribution of diverticula | |||

| Right-sided diverticula | 34 (37)/8 (21) | 0.49 (0.22-1.1) | 0.06 |

| Left-sided diverticula | 19 (20)/8 (21) | 1.3 (0.60-2.8) | 0.51 |

| Bilateral diverticula | 40 (43)/23 (59) | 1.5 (0.79-2.8) | 0.21 |

| Endoscopic procedure | 20 (22)/3 (7.7) | 0.43 (0.13-1.4) | 0.16 |

| Transfusion requirement | 25 (27)/12 (31) | 1.2 (0.63-2.5) | 0.53 |

| Current drinker | 90 (97)/36 (92) | 0.78 (0.24-2.5) | 0.68 |

| Current smoker | 26 (28)/10 (26) | 0.80 (0.39-1.7) | 0.55 |

| NSAID users | 4 (4.3)/11 (28) | 5.1 (2.5-10) | < 0.01 |

| Low-dose aspirin1 users | 20 (22)/9 (23) | 0.88 (0.42-1.9) | 0.74 |

| Non-aspirin antiplatelet1 users | 16 (17)/11 (28) | 1.6 (0.78-3.1) | 0.21 |

| Anticoagulant1 users | 7 (7.5)/2 (5.1) | 0.54 (0.13-2.2) | 0.38 |

| Acetaminophen users | 10 (11)/3 (7.7) | 0.72 (0.22-2.3) | 0.58 |

| Corticosteroid users | 3 (3.2)/2 (5.1) | 1.4 (0.35-6.0) | 0.61 |

| Hypertension | 55 (60)/28 (72) | 1.4 (0.69-2.8) | 0.35 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (24)/5 (13) | 0.52 (0.20-1.3) | 0.16 |

| Dyslipidemia | 20 (22)/9 (23) | 0.88 (0.42-1.8) | 0.73 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 25 (27)/8 (21) | 0.55 (0.25-1.2) | 0.13 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (1.1)/1 (2.6) | 1.4 (0.19-10) | 0.76 |

| Chronic liver disease | 3 (3.2)/2 (5.1) | 1.4 (0.34-5.9) | 0.62 |

| Hemodialysis | 2 (2.2)/5 (13) | 4.0 (1.5-10) | < 0.01 |

Non-selective NSAIDs included loxoprofen, diclofenac, naproxen, etodolac, zaltoprofen, meloxicam, lornoxicam, and celecoxib (n = 3). Distribution type was defined as follows: right-sided, involving the transverse or proximal colon; left-sided, involving the descending or distal colon; or bilateral, involving the entire colon. Low-dose aspirin included enteric-coated aspirin (100 mg) and buffered aspirin (81 mg). Non-aspirin antiplatelets included ticlopidine, clopidogrel, cilostazol, dipyridamole, sarpogrelate hydrochloride, ethyl icosapentate, dilazep, limaprost, and beraprost. Anticoagulants included warfarin and dabigatran etexilate. CI: Confidence interval; NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Table 3.

Risk factors for rebleeding after discharge on multivariate analysis (n = 132)

| Factor | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P |

| Age > 70 yr | 1.2 (0.6-2.3) | 0.68 |

| Right-sided diverticula | 0.6 (0.3-1.5) | 0.29 |

| Continued NSAID use | 4.6 (2.2-9.4) | < 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 1.3 (0.6-2.8) | 0.43 |

| Hemodialysis | 3.0 (1.1-7.8) | 0.03 |

CI: Confidence interval; NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

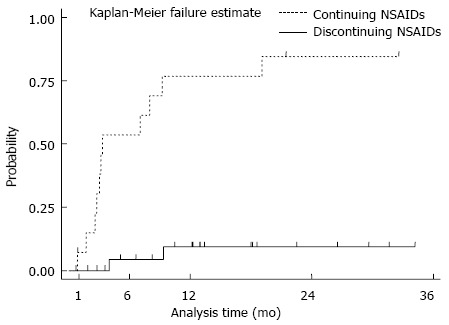

Discontinuation of NSAIDs and rebleeding

Of the NSAID users (n = 41), 15 continued and 26 discontinued NSAID use after discharge. During the follow-up period, no patient developed a thrombotic event, such as pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, or a cerebrocardiovascular event. No patient who discontinued NSAID use on discharge resumed NSAID use during the follow-up period. The probability of rebleeding was 0% at 1 mo and only 9.4% (95%CI: 2.4%-33%) at 12 mo in discontinuing NSAID users compared with 7.1% (95%CI 1.0%-41%) at 1 mo and 77% (95%CI: 52%-94%) at 12 mo in the continuing users (P < 0.01 by the log-rank test; Figure 2). The hazard ratio (HR) for rebleeding in the discontinuing NSAIDs group was 0.06 (95%CI: 0.01%-0.31%) after adjusting for age > 70 years, right-sided diverticula, history of hypertension, and hemodialysis in the Cox proportional hazards model.

Figure 2.

Probability of recurrent bleeding in patients with non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs on admission (n = 41). The probability of rebleeding was higher in subjects continuing non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) than in those discontinuing NSAIDs (P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report showing that discontinuation of NSAIDs at discharge significantly reduced rebleeding compared with continuous NSAID use. Although, the number of NSAIDs users was small, this finding is useful in the long-term management of CDB. Moreover, no patients developed a worsening condition of underlying disease, thrombotic events, or cerebrocardiovascular events after cessation of NSAIDs.

In agreement with previous studies, this study showed that patients using NSAIDs had a risk of rebleeding during follow-up (often within the first year) approximately 5-fold greater than those without. A previous large cohort study found that NSAID users had a 1.7-fold higher risk of CDB[10], and other case-control studies have reported increased bleeding risks of 4-15-fold[6,11,15] and re-bleeding risks of 3-6-fold[5,6]. Tsuruoka et al[16] conducted CDB case-control (patients hospitalized for other diseases during the same period) investigations and showed that only NSAID use was an independent risk factor for bleeding (OR = 9.9) and rebleeding (OR = 5.4). Another report by Wilcox et al[17] compared 105 patients with LGIB and 1895 non-bleeding controls, and found that NSAID users had a 3.4-fold higher risk of CDB. Although a wide range of risk ratios have been reported, likely due to differences in study design or sample size, it is clear that NSAID use is an unequivocal risk factor for CDB.

In contrast to this greater risk of rebleeding, withdrawal of NSAIDs significantly reduced the risk of rebleeding during follow-up compared with continued use (HR = 0.06). In UGIB, protonpump inhibitors reduce recurrence[8], but there is no preventive therapy for LGIB. It is thus all the more critical to validate factors associated with risk reduction in LGIB. A few studies have examined the risk reduction of GI bleeding associated with drug withdrawal, but not non-aspirin NSAIDs. Witt et al[18] found that patients with GI bleeding who resumed warfarin use had a higher GI re-bleeding risk and fewer thrombotic events than those who discontinued use. Sung et al[9] conducted a randomized controlled trial in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding and found that continuous low-dose aspirin increased the risk of re-bleeding, but potentially reduced mortality, while prolonged discontinuation of aspirin led to a lower risk of rebleeding, but higher mortality. One of the reasons we could withdraw NSAIDs in many of our patients (26/41) was that most were not regular users and could be switched to other drugs, such as acetaminophen, an antiinflammatory analgesic plaster, antigout drugs, antirheumatic drugs, or corticosteroids. Furthermore, we could closely monitor these patients and confirm no exacerbation of pain. However, one randomized controlled trial on the treatment of painful knee osteoarthritis found that discontinuation of non-aspirin NSAIDs exacerbated pain and negatively impacted patient quality of life[19]. Thus, the decision to terminate NSAIDs should be carefully considered.

In contrast, the cessation of NSAIDs may cause cardiovascular events. Fischer et al[20] conducted a large case-control study and suggested that the risk of developing acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is increased for a period of several weeks after discontinuing NSAID use, particularly in patients using NSAIDs on a long-term basis. Their study indicated that the risk of AMI was not increased in patients currently using NSAIDs or in users who stopped using NSAIDs more than 3 mo before. In this study, no patients had a high risk of AMI such as long-term internal users or regular users. Therefore, caution should be exercised in such patients when discontinuing NSAIDs.

Hemodialysis was associated with rebleeding in the present study. Intermittent use of heparin for dialysis treatment and the presence of uremia-induced platelet dysfunction are associated with GI bleeding[21,22]. In addition, patients with chronic kidney disease demonstrate abnormalities in blood coagulation and bleeding predisposition, resulting in consistent anemia in UGIB cases[22,23]. Thus, hemodialysis patients with CDB should be carefully managed after discharge.

In this study, we were able to prospectively collect detailed information on comorbidities and medication, and to conduct long-term follow-up of patients hospitalized for CDB. Nonetheless, there are several limitations to this study. First, the number of patients who discontinued NSAIDs was relatively small. Second, no data on hemodynamic instability, hematocrit, and abnormal white blood cell count were collected. Third, the study had a non-randomized controlled design.

In conclusion, discontinuation of NSAIDs is an effective preventive measure against rebleeding in CDB. Patient education about the reduction in the risk of bleeding is important, but medication withdrawal should be considered in view of its risks and benefits, particularly in patients of advanced age or with comorbidities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Hisae Kawashiro, Clinical Research Coordinator, for assistance with data collection.

COMMENTS

Background

Even though intensive management for diverticular bleeding is successful during the hospital stay, patients are at high risk of recurrent bleeding following discharge. Unlike upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, there are no preventive therapies for lower GI bleeding. Thus, preventing recurrence requires risk factors to be identified.

Research frontiers

The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is a significant risk factor for recurrence, but the risks and benefits of their discontinuation on diverticular bleeding have not been examined.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In total, 39 patients (30%) had rebleeding during a median follow-up of 15 mo. Of the 41 NSAID users on admission, 26 (63%) discontinued NSAID use at discharge. Multivariate analysis revealed continued NSAID use (HR = 4.6, P < 0.01) and hemodialysis (HR = 3.0, P < 0.01) as independent risk factors for rebleeding. Discontinuation of NSAIDs significantly reduced rebleeding risk compared with continued use (log-rank test, P < 0.01).

Applications

Discontinuation of NSAIDs is an effective preventive measure against rebleeding in diverticular bleeding. However, medication withdrawal should be considered in view of its risks and benefits, particularly in patients of advanced age or with comorbidities.

Terminology

The precise mechanisms of NSAID-induced diverticular bleeding has been suggested to be due to the inhibition of platelets, cyclooxygenase-1, and prostaglandin synthesis in the lower GI tract. Mucosal injury due to the inhibition of intestinal prostaglandin synthesis might lead to the development of intestinal erosion and ulcers. When mucosal ulceration induced by NSAIDs occurs at the neck or dome of the diverticula, nutrient-providing arteries rupture into the colonic lumen with the potential to cause sudden bleeding.

Peer review

The manuscript investigates the impact of discontinuing NSAIDs and the long-term recurrence in colonic diverticular bleeding. The authors tried to bring new ideas about preventive measure against colonic diverticular re-bleeding.

Footnotes

Supported by A Grant-in-Aid for Research from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine No. 26A-201.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 3, 2014

First decision: July 21, 2014

Article in press: September 19, 2014

P- Reviewer: Guo YM S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Longstreth GF. Epidemiology and outcome of patients hospitalized with acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:419–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foutch PG. Diverticular bleeding: are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs risk factors for hemorrhage and can colonoscopy predict outcome for patients? Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1779–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuire HH. Bleeding colonic diverticula. A reappraisal of natural history and management. Ann Surg. 1994;220:653–656. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199411000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strate LL, Orav EJ, Syngal S. Early predictors of severity in acute lower intestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:838–843. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niikura R, Nagata N, Yamada A, Akiyama J, Shimbo T, Uemura N. Recurrence of colonic diverticular bleeding and associated risk factors. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:302–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okamoto T, Watabe H, Yamada A, Hirata Y, Yoshida H, Koike K. The association between arteriosclerosis related diseases and diverticular bleeding. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1161–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1491-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishikawa H, Maruo T, Tsumura T, Sekikawa A, Kanesaka T, Osaki Y. Risk factors associated with recurrent hemorrhage after the initial improvement of colonic diverticular bleeding. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2013;76:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Arroyo MT, Bujanda L, Gomollón F, Forné M, Aleman S, Nicolas D, Feu F, González-Pérez A, et al. Effect of antisecretory drugs and nitrates on the risk of ulcer bleeding associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulants. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:507–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, Wu JC, Lee YT, Chiu PW, Leung VK, Wong VW, Chan FK. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:1–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strate LL, Liu YL, Huang ES, Giovannucci EL, Chan AT. Use of aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increases risk for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1427–1433. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada A, Sugimoto T, Kondo S, Ohta M, Watabe H, Maeda S, Togo G, Yamaji Y, Ogura K, Okamoto M, et al. Assessment of the risk factors for colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:116–120. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niikura R, Nagata N, Akiyama J, Shimbo T, Uemura N. Hypertension and concomitant arteriosclerotic diseases are risk factors for colonic diverticular bleeding: a case-control study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1137–1143. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1422-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen DM, Machicado GA, Jutabha R, Kovacs TO. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:78–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuckerman GR, Prakash C. Acute lower intestinal bleeding. Part II: etiology, therapy, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:228–238. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagata N, Niikura R, Aoki T, Shimbo T, Kishida Y, Sekine K, Tanaka S, Watanabe K, Sakurai T, Yokoi C, et al. Colonic diverticular hemorrhage associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, low-dose aspirin, antiplatelet drugs, and dual therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1786–1793. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuruoka N, Iwakiri R, Hara M, Shirahama N, Sakata Y, Miyahara K, Eguchi Y, Shimoda R, Ogata S, Tsunada S, et al. NSAIDs are a significant risk factor for colonic diverticular hemorrhage in elder patients: evaluation by a case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1047–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilcox CM, Alexander LN, Cotsonis GA, Clark WS. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs are associated with both upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:990–997. doi: 10.1023/a:1018832902287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witt DM, Delate T, Garcia DA, Clark NP, Hylek EM, Ageno W, Dentali F, Crowther MA. Risk of thromboembolism, recurrent hemorrhage, and death after warfarin therapy interruption for gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1484–1491. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Louthrenoo W, Nilganuwong S, Aksaranugraha S, Asavatanabodee P, Saengnipanthkul S. The efficacy, safety and carry-over effect of diacerein in the treatment of painful knee osteoarthritis: a randomised, double-blind, NSAID-controlled study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:605–614. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer LM, Schlienger RG, Matter CM, Jick H, Meier CR. Discontinuation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy and risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2472–2476. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.22.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Minno G, Martinez J, McKean ML, De La Rosa J, Burke JF, Murphy S. Platelet dysfunction in uremia. Multifaceted defect partially corrected by dialysis. Am J Med. 1985;79:552–559. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerson LB. Causes of gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients with chronic renal failure. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:895–87; discussion 897. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wasse H, Gillen DL, Ball AM, Kestenbaum BR, Seliger SL, Sherrard D, Stehman-Breen CO. Risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding among end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1455–1461. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]