Abstract

Ralstonia pickettii is a rare pathogen and even more rare in healthy individuals. Here we report a case of R. pickettii bacteremia leading to aortic valve abscess and complete heart block. To our knowledge this is the first case report of Ralstonia species causing infective endocarditis with perivalvular abscess.

1. Case Report

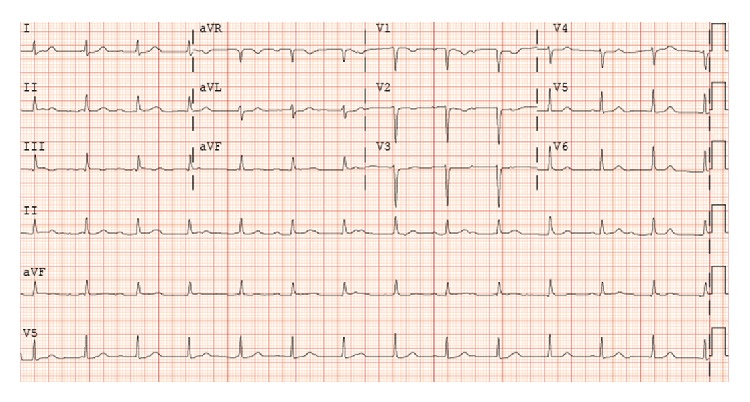

A 51-year-old female with a past medical history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism, and well controlled diabetes mellitus type 2 (hemoglobin A1c 6.1%) presented after several days of worsening chest pain, low-grade fevers, and chills. Several weeks prior to presentation patient had a central venous catheter placed for intravenous iron infusions to treat refractory iron-deficiency anemia. Three weeks prior to presentation, the patient had left tarsal tunnel release with no postoperative complications. Upon presentation, to the hospital for evaluation she was bradycardic with a pulse of 48 beats per minute, hypotensive with a blood pressure of 106/54 mmHg (as compared to her baseline hypertension), and febrile to 101.3°C. Given her history of DVT, a computed tomography (CT) angiogram was ordered that revealed no new pulmonary emboli but showed cavitary lung lesions suggestive of septic emboli. An electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated accelerated junctional escape rhythm with complete atrioventricular block (Figure 1). Blood and urine cultures were obtained, and patient was initiated on empiric coverage for endocarditis with vancomycin, gentamicin, and micafungin.

Figure 1.

ECG demonstrating complete atrioventricular block with accelerated junctional escape.

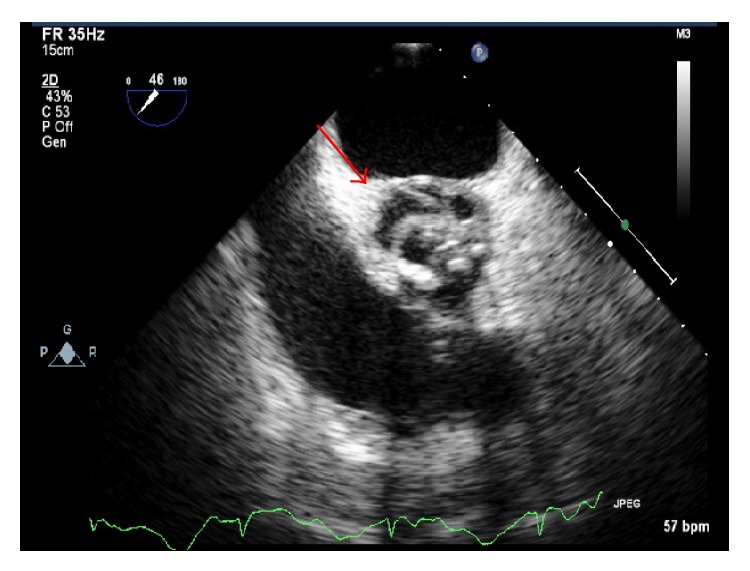

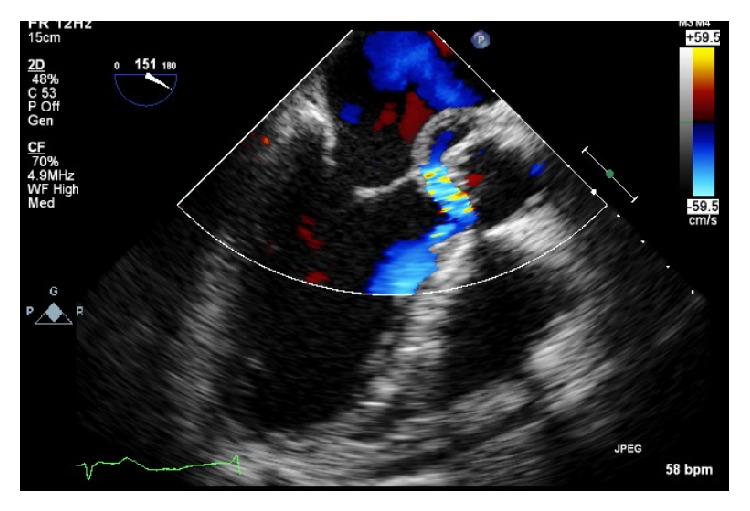

Given CT evidence of septic emboli, fevers, and ECG findings of complete AV block, an initial transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was performed on day two of admission, followed by a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) on day three of admission. TEE confirmed initial TTE findings of aortic valve thickening on the left coronary cusp highly suggestive of vegetation (Figure 2) and associated severe aortic regurgitation. Furthermore, an echo density was noted at the aortic root with color flow transmission highly suggestive of an aortic root abscess with fistula (Figure 3). There was moderate mitral valve regurgitation with normal left ventricular systolic function. A bicuspid aortic valve was also noted on the TEE. Gram-positive cocci were seen on Gram stain from blood cultures drawn on admission; therefore she was continued on vancomycin and gentamicin. The patient was referred for emergent cardiothoracic surgery with replacement of the aortic valve with a 19 mm freestyle tissue valve, incision and drainage and debridement of the subannular abscess, and reconstruction of the proximal anterior leaflet of the mitral valve and aortic annulus with pericardial patch placement which was performed at an outside hospital on day six of hospitalization. No pacemaker was placed at this time of surgery as the cardiothoracic surgeons felt that it would best be placed once her blood cultures were sterile. At the time of valve replacement a transfemoral pacer was placed.

Figure 2.

Transesophageal echocardiogram at midesophageal inflow/outflow tract revealing subannular abscess, in diastole.

Figure 3.

Transesophageal echocardiogram at midesophageal long-axis view with Doppler revealing regurgitation into abscess surrounding the aortic valve suggestive of aortic fistula.

Within 24 hours of hospitalization, blood cultures drawn on admission began growing what was initially identified as Gram-positive cocci. However, on day three of admission the Gram stain was reassessed and changed to Gram-negative rods identified as Ralstonia species. Repeat blood cultures on consecutive days up until the day of surgery grew persistent Ralstonia species, which was ultimately identified as Ralstonia pickettii. Surgical specimens from the aortic valve and annular abscess all had heavy growth of R. pickettii (surgical intervention on day 6). All postsurgical blood cultures remained negative (Table 1). She was initially on aggressive Gram-positive coverage initially with vancomycin and gentamicin; however this was quickly changed to levofloxacin once sensitivities returned. The Ralstonia species, later identified as pickettii, was sensitive to quinolones and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole only with intermediate sensitivity to piperacillin/tazobactam, imipenem, and cefepime and complete resistance to tobramycin amikacin and gentamycin. Her postoperative course was uneventful except for dental extractions done for extensive necrosis and caries. She was initiated on levofloxacin on day four of admission and completed a total of eight weeks of therapy postoperatively. Upon sterilization of blood cultures approximately one week after surgery, a dual-chamber pacemaker was implanted.

Table 1.

Blood culture results as referenced by days after hospital admission with day 1 being the day of admission. Surgical intervention with aortic valve replacement occurred on day 6 of hospitalization. Organism identified in all cultures was Ralstonia pickettii.

| DPA | Culture source | Culture result | TTP hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blood | + | <24 |

| 2 | Blood | + | <24 |

| 3 | Blood | + | <24 |

| 4 | Blood | + | <24 |

| 6 | Aorta | + | <24 |

| 7 | Blood | − | NA |

| 8 | Blood | − | NA |

| 9 | Blood | − | NA |

DPA: days postadmission; TTP: time to positivity in hours.

Unfortunately, shortly after completion of the initial eight weeks of antibiotic therapy, the patient developed recurrent bacteremia with Ralstonia pickettii complicated by a periannular abscess around the new aortic valve prosthesis and a pseudoaneurysm of the ascending aorta. She was again emergently taken for repeat aortic root replacement with a 24 mm homograft and treated with aggressive antibiotic therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and levofloxacin (after repeat sensitivity testing). Unfortunately the patient rapidly succumbed to infection and died due to complications of persistent bacteremia.

Ralstonia species are aerobic Gram-negative, oxidase-positive, nonfermenting bacilli that have in recent years been identified as emerging opportunistic pathogens in immunocompromised hosts. Both environmental and hospital sources have been identified in human infection. Of the Ralstonia genus, Ralstonia pickettii formerly known as Burkholderia pickettii is regarded as the one with clinical importance [1]. It was first identified as Pseudomonas pickettii in 1973 [2] and then reclassified in 1992 to the Burkholderia [3] genus and finally in 1995 to a new genus Ralstonia [4–6], based upon cellular lipid and fatty acid composition, phenotypic analysis, and both DNA and 16s rRNA sequencing and hybridization. Disease associated with Ralstonia pickettii ranges from asymptomatic to septicemia and death.

2. Discussion

Historically, the first documented case of Ralstonia bacteremia and death was reported in 1968 [7]. At that time, the pathogen was reported as an unclassified, Gram-negative bacterium (Group IV d) which was only later identified as Ralstonia pickettii [8]. The case was a 33-year-old African American male who had persistent positive blood cultures with a Group IV d Gram-negative bacillus resistant to all attempted antibiotics (ampicillin, penicillin G, and chloramphenicol). Autopsy was refused; however the patient was noted to have persistent positive blood cultures, a IV/VI harsh systolic murmur at the apex transmitting to the axilla, and fevers, suggesting endocarditis due to persistent bacteremia as cause of death [7].

More recent outbreaks of Ralstonia pickettii infections are documented as nosocomial outbreaks related to the use of contaminated medical solutions (saline, sterile water, disinfectants, intravenous ranitidine, and narcotics) used in patient care [9–17]. In Table 2 we provide a comprehensive review of literature to date from 2005 onward that reflects possible contamination sources as well as outcomes. Prior to 2006 Ryan et al. provide an excellent comprehensive review [1]. The presumptive ability of Ralstonia to persist in these sterile solutions is thought to be associated with its ability to survive within a wide range of temperatures (15°C–42°C) and pass through both 0.2 and 0.45 μm filters, which are used to filter-sterilize medical solutions [18]. In a review of the literature there have been 55 cases of Ralstonia species infections, ranging from bacteremia to meningitis. The majority of infections reported have been treated with piperacillin, imipenem plus amikacin, and a combination of unnamed cephalosporins and aminoglycoside, as well as meropenem. There is no standardized recommendation for the treatment of Ralstonia infection because of the differences in sensitivities in particular to the carbapenems and aminoglycosides as well as the range of disease which includes asymptomatic to frank sepsis as in our patient. Only eight documented cases have resulted in death. The first case was the index case in 1968 as described above [7]. Two cases were elderly diabetic patients who died from complications of R. pickettii septicemia as a result of contaminated ion-exchange resins used to purify water for hospital use [19]. The ion-exchange resins used for deionization of city water allowed the survival of bacteria normally found in the city water supply while the bacteriological filters downstream only lowered the contamination level. Four premature infants have died from complications of R. pickettii-related infections. Of the four cases, one was pneumonia [20] and the other three were associated with bacteremia and sepsis [21, 22]. Finally, the eighth documented case resulting in death is our 51-year-old female who developed endocarditis due to complications of Ralstonia pickettii bacteremia with perivalvular abscess.

Table 2.

Comprehensive review of the literature from 2005 of cases of Ralstonia pickettii infection, traced source(s), and treatments where available.

| Overview of Ralstonia species infections | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Age (years) | Gender | Potential offending agent | Infection | Antibiotics used | Surgery | Outcome | |

| Our case | 1 | 51 | Female | Iron infusions | Endocarditis | Levofloxacin TMP-SMX |

AVR | Died |

|

| ||||||||

| Graber et al. [7] | 1 | 33 | Male | IV drug abuse | Endocarditis∗ | Penicillin + chloramphenicol | None | Died |

|

| ||||||||

| Poty et al. [19] | 4 | Adults | — | Ion-exchange resin | Bacteremia | — | None | 2 died 2 survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Timm et al. [20] | 10 | Neonates | — | Acetic acid cleaning solution | Pneumonia | — | None | 1 died 9 survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Moreira et al. [21] | 13 | Adults | — | “Sterile” water for injection | Bacteremia | Ciprofloxacin + gentamicin | None | All survived |

| 3 | Neonates | — | Bacteremia Pneumonia |

Ampicillin + gentamicin | None | 2 died 1 survived |

||

|

| ||||||||

| Vitaliti et al. [22] | 1 | 26 weeks gestation | Female | — | Bacteremia | Cephalosporin + meropenem + aminoglycoside | None | Died |

|

| ||||||||

| Stelzmueller et al. [23] | 38 | Adults | — | None identified | Pneumonia Bacteremia |

— | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Forgie et al. [26] | 2 | Neonates | — | ECMO circuits | Bacteremia | Tobramycin + piperacillin-tazobactam | None | 1 died 1 survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Kismet et al. [27] | 2 | Toddlers | Females | Port-A-Cath | Bacteremia | Meropenem + cefepime | Removal of Port-A-Cath | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Kimura et al. [28] | 18 | Neonates | — | Heparin flush | Bacteremia | Piperacillin | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Strateva et al. [29] | 1 | 75 | Female | Hemodialysis system | Bacteremia | Levofloxacin | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Fernández et al. [11] | 46 | — | — | IV Ranitidine | Bacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Kahan et al. [30] | 6 | — | — | 0.05% chlorhexidine | Bacteremia | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Roberts et al. [10] | 19 | — | — | “Sterile” water | Bacteremia | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Raveh et al. [31] | 4 | — | — | IV catheters | Bacteremia | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Fujita et al. [32] | 1 | 53 | Male | IV catheter | Bacteremia | Cefazolin | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Mikulska et al. [33] | 10 | — | — | None identified | Bacteremia | 3rd generation cephalosporins + amikacin or carbapenems | None | 1 died 9 survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Woo et al. [34] | 1 | 7 | Male | Cord blood transplant | Bacteremia | Cefoperazone/sulbactam + ciprofloxacin | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Marroni et al. [35] | 9 | Adults | — | Heparin solution | Bacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Adiloğlu et al. [36] | 1 | Neonate | — | Distilled incubator water | Bacteremia | — | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Candoni et al. [37] | 20 | Adults | — | None identified | Bacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Japp et al. [38] | 1 | — | — | None identified | Bacteremia | — | None | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Hansen et al. [39] | 1 | — | — | IV catheter | Bacteremia | — | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Chomarat et al. [40] | 1 | — | — | None identified | Bacteremia | — | — | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Lazarus et al. [41] | 1 | Adult | — | In vitro handling process | Bacteremia | — | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Marroni et al. [35] | 6 | — | — | Purified saline | Bacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Yoneyama et al. [42] | 17 | Adults | — | 0.05% chlorhexidine aqueous solution | Bacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Lacey and Want [9] | 7 | Children | — | “Sterile” distilled water | Bacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Chetoui et al. [43] | 6 | Adults | — | “Sterile” saline | Bacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Maki et al. [12] | 9 | Adults | — | Pre-drawn fentanyl syringes | Bacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Gardner and Shulman [13] | 9 | Infants | — | Tracheal irrigant solution | Respiratory infection | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Trotter et al. [44] | 1 | 5 | Male | None identified | Pneumonia | TMP-SMX | Decortication | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Hagadorn et al. [45] | 1 | Neonate | — | Home water birth | Pneumonia | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Miñambres et al. [46] | 1 | Adult | — | None identified | Pneumonia | — | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| MMWR [16] | 13 | Children | 9 Female 4 Male |

0.9% sodium chloride solution | Colonization respiratory infection |

— | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| MMWR [14] | 5 | Infants | — | 0.9% sodium chloride solution | Colonization respiratory infection |

— | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Labarca et al. [17] | 34 | — | — | 0.9% sodium Chloride | Pneumonia bacteremia |

— | None | 5 died 29 survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Pan et al. [47] | 1 | 65 | Male | None identified | Pneumonia | Imipenem-cilastatin | Chest tube | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Ahkee et al. [48] | 1 | 41 | Male | Respiratory therapy solution | Pneumonia | Aztreonam piperacillin |

Thoracentesis | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Kendirli et al. [49] | 2 | 2 months | Female | Ventilator circuit | Pneumonia bacteremia |

Piperacillin-tazobactam | None | Survived |

| 14 | Male | Pneumonia bacteremia |

None | Died | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Burns et al. [50] | 2 | Adults | — | Cystic fibrosis | Respiratory infection | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Wertheim and Markovitz [51] | 1 | 71 | Male | None identified | Osteomyelitis | TMP-SMX | Laminectomy | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Degeorges et al. [52] | 1 | 29 | Male | None identified | Osteomyelitis | — | Debridement | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Elsner et al. [53] | 1 | Adult | — | Hemodialysis machine | Spinal osteitis | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Sudo et al. [54] | 1 | 48 | Female | None identified | Spondylitis | Cefepime + minocycline | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Zellweger et al. [55] | 1 | — | Male | IV drug abuse | Septic arthritis | Ceftriaxone | — | Died |

|

| ||||||||

| Makaritsis et al. [56] | 1 | 83 | Female | None identified | Septic arthritis | Ceftazidime | Arthrocentesis | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Heagney [57] | 1 | — | — | None identified | Meningitis | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| T'Sjoen et al. [58] | 1 | 38 | Female | Ventriculoarterial shunt | Meningitis | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Fass and Barnishan [59] | 1 | — | — | None identified | Meningitis | — | None | — |

|

| ||||||||

| Yuen et al. [60] | 1 | 32 | Male | None identified | Peritonitis | Cefuroxime | Paracentesis | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Carrell et al. [61] | 1 | — | Male | — | Seminal infection | — | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Parent and Mitchell [62] | 8 | Adults | — | Crohn's disease | Infection | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Minah et al. [63] | — | — | — | Myelosuppressed cancer | Asymptomatic | — | — | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| McNeil et al. [15] | 5 | Infants | — | Respiratory therapy solution | Asymptomatic | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Costas et al. [64] | 28 | Infants | — | None identified | Pseudooutbreak | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Heard et al. [65] | 15 | Infants | — | Contaminated bottles | Pseudooutbreak | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Dimech et al. [8] | 6 | Adults | — | Detergent disinfectant | Pseudobacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Lacey and Want [9] | 25 | Adults | — | Blood culture technique | Pseudobacteremia | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Boutros et al. [66] | 14 | — | — | Culture bottles | Pseudobacteremia | None | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Maroye et al. [67] | 6 | Children | — | Distilled water | Asymptomatic | — | None | All survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Morar et al. [68] | 1 | Child | — | None identified | Asymptomatic | — | None | Survived |

|

| ||||||||

| Yoneyama et al. [42] | 7 | — | — | Water | Asymptomatic | — | None | Survived |

ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IV: intravenous; AVR: aortic valve replacement; TMP-SMX: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

∗Presumed to have endocarditis but could not confirm diagnosis.

Immunocompromised patients seem to be at the highest risk of infection with pulmonary and blood stream infections being the primary routes [23]. Patients with acquired (i.e., HIV) or pharmaceutical (i.e., steroids, TNF blockers) induced immunosuppression are the most likely to succumb to infection with Ralstonia species. The single most important risk factor for acquiring infection with R. pickettii is cystic fibrosis. Furthermore, while respiratory tract and other nonsystemic infections responded well to parenteral antibiotic therapy, it seems to have little success in cases of R. pickettii bacteremia and sepsis, in particular, if a contaminated central venous line is involved. Removal of any indwelling device such as a central venous catheter is mandatory and critical in source control.

Interestingly, our patient had several predisposing risk factors that placed her at risk for both R. pickettii infection and complications. Approximately two months prior to presentation, our patient had a central venous catheter placed for intravenous iron transfusions. She also underwent tarsal tunnel release three weeks prior to presentation. In each of these settings she was exposed to not only potentially contaminated infusions but also hospital related procedures that may have resulted in infectious complications. Previous outbreaks have implicated hospital water, distilled water, saline, ion exchange resins, IV ranitidine, hemodialysis machines, and intravenous drug use [1]. Fortunately, our patient was an isolated case with no other cases suggesting that this was not a hospital associated outbreak. Finally, she was found to have a bicuspid aortic valve, which, in bacteremia, has been associated with increased incidence of infective endocarditis (IE) when compared to those without bicuspid aortic valves. Cases of IE occurring in patients with bicuspid aortic valves as compared to native valves have increased incidence of complications such as valve perforation, valve destruction, heart failure, and valvular, perivalvular, and/or myocardial abscess [24, 25].

Patients with health care-associated infections or who have had recent hospitalization or medical intervention (as in our case) are a new risk group that requires careful diagnostic attention in the presence of fever and bacteremia to evaluate infective endocarditis. Ralstonia pickettii should be considered an important potential etiology of nosocomial infections among patients who are immunocompromised, have cystic fibrosis, have central venous catheters, or have had recent surgical or medical hospitalizations. It is important to quickly recognize and treat R. pickettii as it has been identified as causing many potentially harmful infections resulting in increased morbidity and mortality. Ralstonia species are thought to be a rare infectious organism; however, our review of the literature suggests that the organism may be a more widespread and invasive pathogen than previously thought.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Ryan M. P., Pembroke J. T., Adley C. C. Ralstonia pickettii: a persistent Gram-negative nosocomial infectious organism. The Journal of Hospital Infection. 2006;62(3):278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ralston E., Palleroni N. J., Doudoroff M. Pseudomonas pickettii, a new species of clinical origin related to Pseudomonas solanacearum . International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1973;23(1):15–19. doi: 10.1099/00207713-23-1-15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilligan P. H., Gary L., Vandamme P. A. R., Whittier S. Burkholderia, Stenotrophomonas, Ralstonia, Brevundimonas, Comamonas, Delftia, Pandoraea, and Acidovorax. In: Murray R. P., Baron E. J., Pfaller M. A., Tenover F. C., Yolken R. H., editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. Washington, DC, USA: American Society for Microbiology; 2003. pp. 729–748. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yabuuchi E., Kosako Y., Yano I., Hotta H., Nishiuchi Y. Transfer of two Burkholderia and an Alcaligenes species to Ralstonia gen. nov.: proposal of Ralstonia pickettii (Ralston, Palleroni and Doudoroff 1973) comb. nov., Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith 1896) comb. nov. and Ralstonia eutropha (Davis 1969) comb. nov. Microbiology and Immunology. 1995;39(11):897–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb03275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruckner D. A., Colonna P. Nomenclature for aerobic and facultative bacteria. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1997;25(1):1–10. doi: 10.1086/514506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellegrino F. L. P. C., Schirmer M., Velasco E., de Faria L. M., Santos K. R. N., Moreira B. M. Ralstonia pickettii bloodstream infections at a Brazilian cancer institution. Current Microbiology. 2008;56(3):219–223. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-9060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graber C. D., Jervey L. P., Ostrander W. E., Salley L. H., Weaver R. E. Endocarditis due to a lanthanic, unclassified Gram-negative bacterium (group IV d) American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1968;49(2):220–223. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/49.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimech W. J., Hellyar A. G., Kotiw M., Marcon D., Ellis S., Carson M. Typing of strains from a single-source outbreak of Pseudomonas pickettii . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1993;31(11):3001–3006. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.3001-3006.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacey S., Want S. V. Pseudomonas pickettii infections in a paediatric oncology unit. The Journal of Hospital Infection. 1991;17(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(91)90076-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts L. A., Collignon P. J., Cramp V. B., et al. An Australia-wide epidemic of Pseudomonas pickettii bacteraemia due to contaminated “sterile” water for injection. Medical Journal of Australia. 1990;152(12):652–655. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb125422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernández C., Wilhelmi I., Andradas E., et al. Nosocomial outbreak of Burkholderia pickettii infection due to a manufactured intravenous product used in three hospitals. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1996;22(6):1092–1095. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maki D. G., Klein B. S., McCormick R. D., et al. Nosocomial Pseudomonas pickettii bacteremias traced to narcotic tampering. A case for selective drug screening of health care personnel. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;265(8):981–986. doi: 10.1001/jama.265.8.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner S., Shulman S. T. A nosocomial common source outbreak caused by Pseudomonas pickettii . Pediatric Infectious Disease. 1984;3(5):420–422. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198409000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control. Pseudomonas pickettii colonization associated with a contaminated respiratory therapy solution—Illinois. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 1983;32(38):495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNeil M. M., Solomon S. L., Anderson R. L., et al. Nosocomial Pseudomonas pickettii colonization associated with a contaminated respiratory therapy solution in a special care nursery. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1985;22(6):903–907. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.6.903-907.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Labarca J., Peterson C., Bendaña N., et al. Nosocomial Ralstonia pickettiicolonization associated with intrinsically contaminated saline solution—Los Angelas, California, 1998. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1998;47(14):285–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labarca J. A., Trick W. E., Peterson C. L., et al. A multistate nosocomial outbreak of Ralstonia pickettii colonization associated with an intrinsically contaminated respiratory care solution. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1999;29(5):1281–1286. doi: 10.1086/313458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson R. L., Bland L. A., Favero M. S., et al. Factors associated with Pseudomonas pickettii intrinsic contamination of commercial respiratory therapy solutions marketed as sterile. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1985;50(6):1343–1348. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.6.1343-1348.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poty F., Denis C., Baufine-Ducrocq H. Nosocomial Pseudomonas pickettii infection: hazards of ion-exchange resins. Presse Medicale. 1987;16(24):1185–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timm W. D., Pfaff S. J., Land G. L., Warshauer D. L., Dorff G. L. An outbreak of multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas pickettii pneumonia in a neonatal intensive care unit. Proceedings of the 35th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC '95); 1995; San Francisco, Calif, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreira B. M., Leobons M. B. G. P., Pellegrino F. L. P. C., et al. Ralstonia pickettii and Burkholderia cepacia complex bloodstream infections related to infusion of contaminated water for injection. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2005;60(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitaliti S. M., Maggio M. C., Cipolla D., Corsello G., Mammina C. Neonatal sepsis caused by Ralstonia pickettii . The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2008;27(3):p. 283. doi: 10.1097/inf.0b013e31816454b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stelzmueller I., Biebl M., Wiesmayr S., et al. Ralstonia pickettii—innocent by bystander or a potential threat? Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2006;12(2):99–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yener N., Oktar G. L., Erer D., Yardimci M. M., Yener A. Bicuspid aortic valve. Annals of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2002;8:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamas C. C., Eykyn S. J. Bicuspid aortic valve—a silent danger: analysis of 50 cases of infective endocarditis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2000;30(2):336–341. doi: 10.1086/313646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forgie S., Kirkland T., Rennie R., Chui L., Taylor G. Ralstonia pickettii bacteremia associated with pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy in a Canadian Hospital. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2007;28(8):1016–1018. doi: 10.1086/519205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kismet E., Atay A. A., Demirkaya E., et al. Two cases of Ralstonia pickettii bacteremias in a pediatric oncology unit requiring removal of the Port-A-Caths. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2005;27(1):37–38. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000149960.89192.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura A. C., Calvet H., Higa J. I., et al. Outbreak of Ralstonia pickettii bacteremia in a neonatal intensive care unit. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2005;24(12):1099–1103. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000190059.54356.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strateva T., Kostyanev T., Setchanova L. Ralstonia pickettii sepsis in a hemodialysis patient from Bulgaria. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2012;16(4):400–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahan A., Philippon A., Paul G., et al. Nosocomial infections by chlorhexidine solution contaminated with Pseudomonas pickettii (Biovar VA-1) Journal of Infection. 1983;7(3):256–263. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(83)97196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raveh D., Simhon A., Gimmon Z., Sacks T., Shapiro M. Infections caused by Pseudomonas pickettii in association with permanent indwelling intravenous devices: four cases and a review. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1993;17(5):877–880. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.5.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujita S., Yoshida T., Matsubara F. Pseudomonas pickettii bacteremia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1981;13(4):781–782. doi: 10.1128/jcm.13.4.781-782.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mikulska M., Durando P., Pia Molinari M., et al. Outbreak of Ralstonia pickettii bacteraemia in patients with haematological malignancies and haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2009;72(2):187–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woo P. C. Y., Wong S. S. Y., Yuen K. Y. Ralstonia pickettii bacteraemia in a cord blood transplant recipient. New Microbiologica. 2002;25(1):97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marroni M., Pasticci M. B., Pantosti A., Colozza M. A., Stagni G., Tonato M. Outbreak of infusion-related septicemia by Ralstonia pickettii in the Oncology Department. Tumori. 2003;89(5):575–576. doi: 10.1177/030089160308900528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adiloğlu A. K., Ayata A., Şirin C., Yöndem C., Okutan H. Case report: nosocomial Ralstonia pickettii infection in neonatal intensive care unit. Mikrobiyoloji Bulteni. 2004;38(3):257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Candoni A., Trevisan R., Patriarca F., Silvestri F., Fanin R. Pseudomonas pickettii (Biovar VA-II): a rare cause of bacteremias in haematologic patients. European Journal of Haematology. 2001;66(5):355–356. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2001.066005355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Japp H., von Graevenitz A., Wüst J., Gilardi G. L. Septicemia caused by Pseudomonas VA-1. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 1981;3(18):p. 124. doi: 10.1016/s0196-4399(81)80130-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen W., Glupczynski G., Yourassowsky E. Infections à Pseudomonas pickettii . Medecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 1982;12(9):507–511. doi: 10.1016/s0399-077x(82)80075-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chomarat M., Lepape A., Riou J. Y., Flandrois J. P. Pseudomonas pickettii septicemia. Pathologie Biologie. 1985;33(1):55–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lazarus H. M., Magalhaes-Silverman M., Fox R. M., Creger R. J., Jacobs M. Contamination during in vitro processing of bone marrow for transplantation: clinical significance. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1991;7(3):241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoneyama A., Yano H., Hitomi S., Okuzumi K., Suzuki R., Kimura S. Ralstonia pickettii colonization of patients in an obstetric ward caused by a contaminated irrigation system. The Journal of Hospital Infection. 2000;46(1):79–80. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chetoui H., Melin P., Struelens M. J., et al. Comparison of biotyping, ribotyping, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for investigation of a common-source outbreak of Burkholderia pickettii bacteremia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1997;35(6):1398–1403. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1398-1403.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trotter J. A., Kuhls T. L., Pickett D. A., de La Rocha S. R., Welch D. F. Pneumonia caused by a newly recognized pseudomonad in a child with chronic granulomatous disease. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1990;28(6):1120–1124. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1120-1124.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hagadorn J. I., Guthrie E., Atkins V. A., Devine C. W., Hamilton L. Neonatal aspiration pneumonitis and endotracheal colonization with Burkholderia pickettii following home water birth. Pediatrics. 1997;100:p. 506. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miñambres E., Cano M. E., Zabalo M., García C. Ralstonia pickettii pneumonia in an immunocompetent adult. Medicina Clínica. 2001;117:p. 558. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(01)72177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan W., Zhao Z., Dong M. Lobar pneumonia caused by Ralstonia pickettii in a sixty-five-year-old Han Chinese man: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2011;5, article 377 doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahkee S., Srinath L., Tolentino A., Scortino C., Ramirez J. Pseudomonas pickettii pneumonia in a diabetic patient. The Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association. 1995;93(11):511–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kendirli T., Çiftçi E., İnce E., et al. Ralstonia pickettii outbreak associated with contaminated distilled water used for respiratory care in a paediatric intensive care unit. Jounral of Hospital Infection. 2004;56(1):77–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burns J. L., Emerson J., Stapp J. R., et al. Microbiology of sputum from patients at cystic fibrosis centers in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1998;27(1):158–163. doi: 10.1086/514631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wertheim W. A., Markovitz D. M. Osteomyelitis and intervertebral discitis caused by Pseudomonas pickettii . Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1992;30(9):2506–2508. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2506-2508.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Degeorges R., Teboul F., Belkheyar Z., Oberlin C. Ralstonia pickettii osteomyelitis of the trapezium. Chirurgie de la Main. 2005;24(3-4):174–176. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elsner H.-A., Dahmen G. P., Laufs R., Mack D. Ralstonia pickettii involved in spinal osteitis in an immunocompetent adult. The Journal of Infection. 1998;36(3):p. 352. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(98)94999-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sudo H., Hisada Y., Ito M., Kotaki H., Minami A. Burkholderia pickettii spondylitis. Spinal Cord. 2005;43(8):499–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zellweger C., Bodmer T., Täuber M. G., Mühlemann K. Failure of ceftriaxone in an intravenous drug user with invasive infection due to Ralstonia pickettii . Infection. 2004;32(4):246–248. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-3033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makaritsis K. P., Neocleous C., Gatselis N., Petinaki E., Dalekos G. N. An immunocompetent patient presenting with severe septic arthritis due to Ralstonia pickettii identified by molecular-based assays: a case report. Cases Journal. 2009;2(7, article 8125) doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-8125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heagney M. A. An unusual case of bacterial meningitis caused by Burkholderia pickettii . Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 1998;20(12):102–103. doi: 10.1016/s0196-4399(00)88635-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.T'Sjoen G., Verschraegen G., Steyaert S., et al. Avoidable ‘fever of unknown origin’ due to Ralstonia pickettii bacteremia. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2001;56(1):51–53. doi: 10.1179/acb.2001.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fass R. J., Barnishan J. Acute meningitis due to a Pseudomonas-like group Va-1 Bacillus . Annals of Internal Medicine. 1976;84(1):51–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-84-1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yuen K.-H., Ng F.-H., Mok K.-Y., Ng W.-F. Monomicrobial nonneutrocytic bacterascites due to Burkholderia pickettii . The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1998;93(11):2308–2309. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.2308a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carrell D. T., Emery B. R., Hamilton B. Seminal infection with Ralstonia pickettii and cytolysosomal spermophagy in a previously fertile man. Fertility and Sterility. 2003;79(3):1665–1667. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parent K., Mitchell P. Cell wall-defective variants of Pseudomonas-like (group Va) bacteria in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:368–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Minah G. E., Rednor J. L., Peterson D. E., Overholser C. D., Depaola L. G., Suzuki J. B. Oral succession of gram-negative bacilli in myelosuppressed cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1986;24(2):210–213. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.2.210-213.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Costas M., Holmes B., Sloss L. L., Heard S. Investigation of a pseudo-outbreak of “Pseudomonas thomasii” in a special-care baby unit by numerical analysis of SDS-PAGE protein patterns. Epidemiology and Infection. 1990;105(1):127–137. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800047725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heard S., Lawrence S., Holmes B., Costas M. A pseudo-outbreak of Pseudomonas on a special care baby unit. Journal of Hospital Infection. 1990;16(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(90)90049-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boutros N., Gonullu N., Casetta A., Guibert M., Ingrand D., Lebrun L. Ralstonia pickettii traced in blood culture bottles. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2002;40(7):2666–2667. doi: 10.1128/jcm.40.7.2666-2667.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maroye P., Doermann H. P., Rogues A. M., Gachie J. P., Mégraud F. Investigation of an outbreak of Ralstonia pickettii in a paediatric hospital by RAPD. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2000;44(4):267–272. doi: 10.1053/jhin.1999.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morar P., Makura Z., Jones A., et al. Topical antibiotics on tracheostoma prevents exogenous colonization and infection of lower airways in children. Chest. 2000;117(2):513–518. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]