A 38-year old woman presented with progressive metastatic World Health Organization (WHO) subtype B1 thymoma after previous cisplatin-based chemotherapy, mediastinal radiation and pemetrexed. She enrolled on a phase II trial of cixutumumab, an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor antibody (20 mg/kg, intravenously q 3 weeks).1

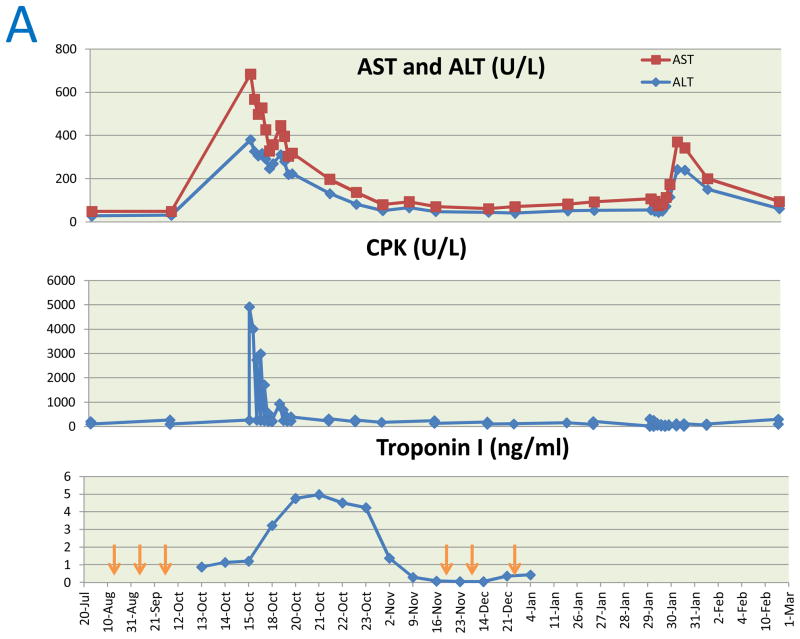

After two doses, a 29% reduction in the sum of target lesions was observed. Three weeks after the third dose, she presented with fatigue, dyspnea, dysphagia and dysphonia. She had grade 4 proximal muscle weakness of extremities and neck with generalized hyporeflexia. Investigations (Table 1) revealed severe multi-organ dysfunction with polymyositis, fascitis, myocarditis, hepatitis, hypogammaglobulinemia and possible bulbar myasthenic involvement. A day later, she developed worsening of bulbar symptoms and respiratory failure necessitating non-invasive ventilation. She was treated with immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone and responded rapidly with marked improvement in respiratory status, muscle strength, pulmonary function and biochemical parameters (Figure 1A). Peripheral blood lymphocytes and anti-interferon (IFN)-α antibodies were elevated, but CD19+ and CD20+ mature B cells were absent. CD4+, CD8+, CD4−/CD8−, mature naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were increased with an inverted CD4/CD8 ratio.

Table 1.

Results of pertinent diagnostic tests at presentation

| Variable | Lab value (normal) |

|---|---|

| White blood cell count | 14.3 (3.9–10K/ul) |

| CD4+ T cells | 3324 (359–1565/uL) |

| CD8+ T cells | 3389 (178–853/uL) |

| CD4−/CD8− T cells | 375 (18–185/uL) |

| Mature naive (CD45RA+/CD3+) CD4+ T cells | 2466 (82–755/uL) |

| Mature naive (CD45RA+/CD3+) CD8+ T cells | 3093 (51–572/uL) |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 0.98 |

| Eosinophils | 15 (0.7–5.8%) |

| CPK | 4927 (38–252 U/L) |

| CPK-MB fraction | 5% (0–3%) |

| Aldolase | 118 (1–6 U/L) |

| AST | 303 (9– 34 U/L) |

| ALT | 381 (6–41 U/L) |

| IgG | 364 (642–1730 mg/dl) |

| IgA | 42 (91–499 mg/dl) |

| IgM | <21 (34–342 mg/dl) |

| C-reactive protein | 13.8 (<3 mg/L) |

| Anti-acetylcholine receptor Ab | 0.19 (<0.02 nmol/L) |

| Cardiac troponin I | 0.880 (<0.045 ng/ml) |

| Electrocardiograph | Non-specific ST segment T wave abnormalities |

| Echocardiogram | Normal left ventricular ejection fraction and no wall motion abnormalities |

| Cardiac MRI | Atypical delayed enhancement of basal inferolateral and mid anterolateral walls, suggestive of myocarditis |

| Repetitive nerve stimulation test | No change in compound muscle action potential amplitude with repetitive nerve stimulation |

| MRI of thighs | Symmetric scattered foci of increased signal intensity in and adjacent to muscles consistent with myositis and deep fascial inflammation |

| Electromyography | No evidence of active denervation or membrane irritability (test done after patient had been on methylprednisone for 2 days) |

| Pulmonary function tests | Very severe restrictive pattern, decreased diffusion capacity and increased ratio of residual volume/total lung capacity, suggestive of air trapping |

Ig: immunoglobulin; CPK: creatinine phosphokinase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

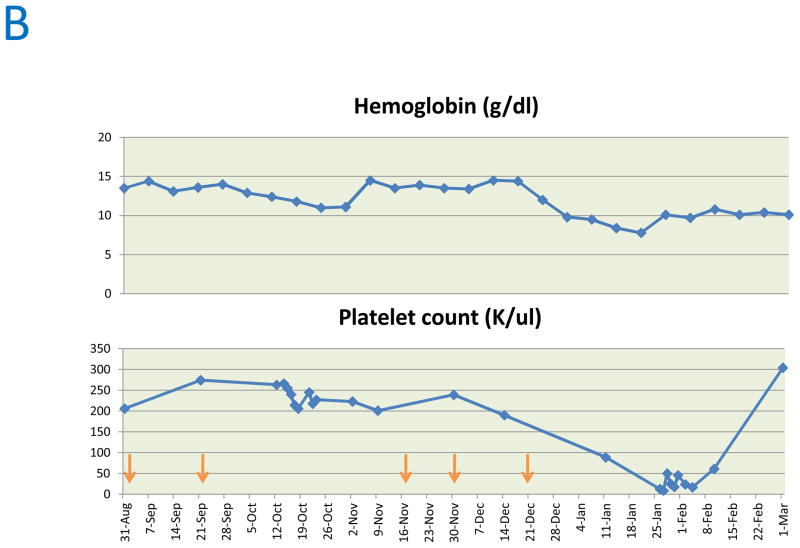

Figure 1.

Trends in aspartate aminotransferase (AST), Alanine transaminase (ALT), Creatine phosphokinase (CPK), troponin I (A), hemoglobin and platelet count (B). Arrows indicate time points at which cixutumumab was administered.

She received three more doses of cixutumumab before disease progression. During steroid taper, she was diagnosed with pure red cell aplasia (PRCA) and amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia based on hypoproliferative anemia (hemoglobin 10 g/dl), thrombocytopenia (platelet count 13,000/ul) and cellular marrow with absent megakaryocytes and severe erythroid hypoplasia. Hematological parameters normalized on cyclosporine A (Figure 1B) and thymoma remained stable.

DISCUSSION

The spectrum of thymoma-associated auto-immune paraneoplastic syndromes include myasthenia gravis (MG) (seen in 30–45% of patients), immune-mediated cytopenias, hypogammaglobulinemia, neurologic syndromes and less commonly polymyositis, hepatitis, and myocarditis. Although MG with auto-immune involvement of another organ system may be found in up to 15% of patients with thymoma, involvement of more than one organ system, as in this case, is rare.

The etiology of thymoma-associated autoimmune phenomena is unclear. Our patient had a complete absence of B cells and markedly abnormal T cell distribution. Lack of thymocyte passage through the medulla, where self-tolerance is induced, may result in thymoma-derived immature T cells and autoreactive T-cell clones. Other potential mechanisms include the increased frequency of mutations in thymoma-derived T cells due to high turnover rate of cortical thymocytes2 and reduced numbers of T regulatory cells, which have inhibitory effects on antigen-specific activation of naive autologous T cells.3 In a subset of patients, defects in autoimmune regulatory (AIRE) gene may play a role. AIRE protein is mainly expressed in medullary thymic epithelial cells where it promotes thymic expression of self-antigens and regulates the negative selection of self-reactive T cells.4 AIRE mutations underlie the APECED syndrome (autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy) which shares autoimmune manifestations and anti-interferon autoantibodies with thymoma associated autoimmune syndromes.5

Nine of 37 (24%) patients with thymoma developed new or worsening autoimmune disorders after receiving cixutumumab in the phase II trial1 including three of five patients who had partial responses. The association between autoimmune manifestations with response is possibly due to modulation of thymic immune mileu by cixutumumab or an egress of dysfunctional T cells to the periphery as a result of tumor shrinkage. While thymoma itself has a strong association with autoimmune phenomena, the potential etiological role of cixutumumab needs further evaluation.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist

References

- 1.Rajan A, Carter CA, Berman A, et al. Cixutumumab for patients with recurrent or refractory advanced thymic epithelial tumours: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:191–200. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70596-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shelly S, Agmon-Levin N, Altman A, Shoenfeld Y. Thymoma and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:199–202. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scarpino S, Di Napoli A, Stoppacciaro A, et al. Expression of autoimmune regulator gene (AIRE) and T regulatory cells in human thymomas. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:504–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson P, Org T, Rebane A. Transcriptional regulation by AIRE: molecular mechanisms of central tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:948–57. doi: 10.1038/nri2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kisand K, Bøe Wolff AS, Podkrajsek KT, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in APECED or thymoma patients correlates with autoimmunity to Th17-associated cytokines. J Exp Med. 2010;207:299–308. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]