Abstract

Ipilimumab improves survival in advanced melanoma and can induce immune-mediated tumor vasculopathy. Besides promoting angiogenesis, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) suppresses dendritic cell maturation and modulates lymphocyte endothelial trafficking. This study investigated the combination of CTLA-4 blockade with ipilimumab and VEGF inhibition with bevacizumab. Patients with metastatic melanoma were treated in four dosing cohorts of ipilimumab (3 or 10 mg/kg) four doses at 3-week intervals and then every 12 weeks, and bevacizumab (7.5 or 15 mg/kg) every 3 weeks. Forty-six patients were treated. Inflammatory events included giant cell arteritis (1), hepatitis (2), and uveitis (2). On-treatment tumor biopsies revealed activated vessel endothelium with extensive CD8+ and macrophage cell infiltration. Peripheral blood analyses demonstrated increases in CCR7+/−/CD45RO+ cells and anti-galectin antibodies. Best overall response included 8 partial responses, 22 stable disease, and a disease-control rate (DCR) of 67.4%. Median survival was 25.1 months. Bevacizumab influences changes in tumor vasculature and immune responses with ipilimumab administration. The combination of bevacizumab and ipilimumab can be safely administered and reveals VEGF-A blockade influences on inflammation, lymphocyte trafficking, and immune regulation. This provides a basis for further investigating the dual roles of angiogenic factors in blood vessel formation and immune regulation as well as future combinations of anti-angiogenesis agents and immune checkpoint blockade.

Introduction

CTLA-4 blockade with ipilimumab improves survival in patients with metastatic melanoma when compared to a gp100 peptide vaccine (1) and in combination with dacarbazine chemotherapy when compared to dacarbazine alone (2). Efforts to further enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade through rational treatment combinations are needed.

In pursuit of predictive markers, pre-treatment levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-A) influence clinical outcomes to ipilimumab therapy (manuscript in preparation). Therefore, determinants that may limit ipilimumab efficacy include immunosuppressive angiogenic factors such as VEGF. VEGF has profound effects on immune regulatory cell function, specifically inhibiting dendritic cell maturation and antigen presentation (3,4). Furthermore, there is increasing evidence for the role angiogenic factors play in influencing lymphocyte trafficking across endothelia into tumor deposits (5). Previous studies have demonstrated the effects of ipilimumab on vessels feeding tumor deposits, resulting in an immune-mediated vasculopathy (6). As a result of CTLA-4 blockade, granulocytes and lymphocytes infiltrate the endothelia resulting in its destruction and tumor necrosis. The clinical efficacy of targeting VEGF-A, and this effect on pathologic angiogenesis has been extensively studied with the use of bevacizumab (7-13), and suggests a role in counteracting the immunosuppressive actions of VEGF. Given the effects on tumor vasculature witnessed in melanoma patients being treated with ipilimumab and the known activity of bevacizumab, we conducted a phase I study to investigate the potential synergies of this combination in patients with metastatic melanoma.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Treatment

The protocol (Appendix A) was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center institutional review board and all patients provided signed informed consent. Patient eligibility included measureable unresectable stage III or stage IV melanoma, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, adequate end-organ function. Exclusion criteria included CNS metastases, prior treatment with ipilimumab or bevacizumab, history of autoimmune disease, melanoma involvement in the gastrointestinal tract, ulcerated skin lesions, or ongoing treatment with full-dose warfarin, heparin equivalent, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin within 10 days of enrollment, or any medication that inhibits platelet function within two weeks prior to enrollment. Four cohorts of patients each received four doses of ipilimumab at three-week intervals and then every three months, plus bevacizumab every three weeks (continuous): Cohort 1: ipilimumab 10 mg/kg + bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg; Cohort 2: ipilimumab 10 mg/kg + bevacizumab 15 mg/kg; Cohort 3: Ipilimumab 3 mg/kg + bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg; Cohort 4: ipilimumab 3 mg/kg + bevacizumab 15 mg/kg) (Supplemental Figure 1). Cohorts that included 3 mg/kg were added following the approval of ipilimumab at this dose to gain safety data and experience.

Patients were first enrolled in cohorts of five with 10 mg/kg ipilimumab. The dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) period was 12 weeks. If ≥3 of 5 patients in cohort 1 did not experience a DLT then the study was permitted to proceed to the next cohort. If ≥3 patients in cohort 3 experienced a DLT, the study was designed to stop. To ensure that toxicity at the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was acceptable and to gain additional experience with this combination, an additional 12 patients were accrued at the MTD. There was a 94% probability of dose escalation if the true rate of DLT was no more than 20%. If the true rate of DLT exceeded 50%, the probability of escalation was less than 50%.

Statistical Analysis

Best overall response (BORR) was defined as the proportion of patients with complete or partial response at any time while on study. The disease-control rate (DCR) was the proportion of patients with complete response, partial response, or stable disease. Differences in response rates or DCR by cohort were assessed using Fisher's exact test. Time to progression (TTP), overall survival, and duration of response were assessed using the method of Kaplan-Meier, with point-wise, 95% confidence intervals estimated using log(-log(survival)) methodology. Equality of survival curves by cohort was assessed using the log-rank test. Comparisons of the incidences of adverse events by cohort according to CTCAE 3.0 System Class were conducted using Fisher's exact test. All p-values were two-sided, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05. There were no corrections for multiple comparisons.

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood samples from patients receiving ipilimumab alone on an expanded access study were obtained on Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center review board approved protocols and used for comparison to samples from the current trial. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque (GE Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) density gradient centrifuge. Cells were stained with fluorescent conjugated antibodies, and analyzed on a FC500 FACS analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). 1 × 105 events were collected. FACS results are expressed as percentages. (CD4-PE Cy7, CD8-PE Cy7, CD28-PerCP, and CD45RO-ECD antibodies Beckman Coulter; CCR7-FITC R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN); CD57-PE Abcam (Cambridge, MA)). Percentage increase (cutoff ≥5%) between pre-treatment and post-treatment by 50% was considered a significant increase. Differences in the proportions increased between ipilimumab and ipilimumab plus bevacizumab groups were determined by Fisher's exact test.

Immunohistochemistry

Metastatic melanoma samples from patients that received ipililumab plus bevacizumab (n=10) and ipililumab alone (n=6) on an expanded access study were obtained before and after treatment initiation. Ipilimumab alone samples were obtained from patients being treated on approved clinical trials. Post-treatment samples from both the current ipilimumab-bevacizumab trial and ipilimumab alone were obtained at the same time from the initiation of therapy, immediately following the completion of ipilimumab induction at approximately week 12.

Biopsies of end-organs suspected of inflammatory events related to treatment were obtained whenever possible. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained for biomarkers that included CD3 (Dako A0452, 1:250), CD8 (Dako M7103, 1:100), CD20 (Dako N1502, undiluted), Foxp3 (Biolegend 320102, 1:50) and CD163 (Vector VP-C374, 1:500) to characterize immune infiltrates. To assess vessel morphology and activation, CD31 (Dako N1596, undiluted) and E-selectin (Neuromics MO20039, 1:50) antibodies were employed.

Humoral Immune Responses Detected Following Treatment

Antibodies presented in post-treatment sera were screened using ProtoArray Human Protein Microarray V5 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) according to manufacturer instructions. Antibody targets were identified by a Z factor ≥ 0.4. The presence of galectin antibodies in the sera were confirmed by immunoblot analysis using recombinant human galectins-1, -3 and -9 (R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN)). To compare antibody levels as a function of treatment, galectin-1, -3 and -9 immunoblots (blocking 5% BSA) were incubated with pre-treatment and post-treatment sera (1:2000 dilution in PBS with 2% BSA) overnight, followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibody (Invitrogen), and visualized with ECL. Densities of protein bands and backgrounds were quantified using NIH ImmageJ software. After background subtraction, galectin antibody responses to treatment were determined by the formula: Fold-change = (DensityPost – DensityPre)/DensityPre. Fold-change ≥ 0.5 was considered a significant increase.

Results

Patients and Treatment

A total of 46 patients were treated (Figure 1 CONSORT Diagram). Five patients in cohort 1 were first treated without any dose-limiting toxicities. Five patients were then treated in cohort 2 without toxicities, therefore cohort 2 (ipilimumab 10 mg/kg plus bevacizumab 15 mg/kg) was determined to be the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). An additional 12 patients were treated at the MTD. The study was amended to enroll 12 patients each to Cohorts 3 and 4 following the regulatory approval of ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg. Demographics, disease status, and prior treatment according to cohort are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. Patients were predominantly male (61%) with a median age of 58 years (range: 25 to 80). Eighty-nine percent had an ECOG performance status of 0. Forty-one patients (89%) had stage IV melanoma and five (11%) had unresectable, stage III disease. Thirteen (28%) patients had prior chemotherapy and radiation, 7 (15%) had radiation and no chemotherapy, 16 (35%) had chemotherapy and no radiaiton, and 8 (17%) had neither radiation nor chemotherapy. Median number of sites of disease was 3 (range: 1 to 8): 83% had lymph node disease, 63% lung, and 61% soft tissue. The median follow-up based on patients alive at the time of data retrieval was 11.8 months (range 2.6 to 42.5).

Figure 1.

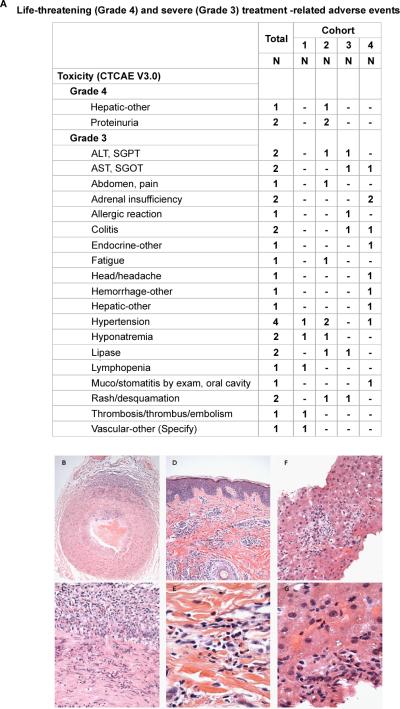

High-grade treatment-related adverse events. A. Grade 4 events. B. Grade 3 Events. Eleven study patients had treatment-related, grade 3 events [23.9%, (95% exact CI: 13% to 39%)]. Hematoxylin and Eosin stained, formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissue sections showing: (C-D) Temporal artery, cut in cross section, with transmural acute and chronic inflammation at 200x (C) and 400x (D) final magnification. (E-F) Skin with chronic inflammation intermixed with eosinophils within the mid-dermis at 400x (E) and 1000x (F) final magnification. (G-H) Core of liver with acute and chronic inflammation including prominent eosinophils, at 400x (G) and 1000x (H) final magnification.

Adverse Events

Toxicities (regardless of attribution) for the first 12 weeks representing the dose-limiting window are presented in Supplemental Table 2. There were two patients who experienced dose-limiting toxicities, one from cohort 3 and one from cohort 4. No dose-limiting toxicities occurred in cohorts 1 or 2. There were no treatment-related deaths. All 46 patients reported adverse events. The most commonly reported adverse events (any grade) were: fatigue (35), rash/desquamation (32), headache (25), and cough (23). Supplemental Table 3 presents the grade 3 and grade 4 events for each dose level for all events and those events possibly, probably, or definitively related.

High-grade (grade 3/4) treatment-related adverse events for any time on study are summarized in Figure 1. Grade 4 events included proteinuria and hepatic toxicities. Thirteen patients experienced high-grade adverse events. High-grade inflammatory events revealed by post-treatment biopsies included giant cell (temporal) arteritis (Figure 1C-D), dermatitis (palpable purpura) (E-F), and eosinophilic hepatitis (G-H). There was one on-treatment death due to disease progression reported for a patient in Cohort 3. The incidence of events per patient is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Worst Grade of Reported Adverse Event/Toxicity per Patient.

| N | Mean | S.D. | Min | Median | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 13 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 |

| Cohort | 1 | 2.0 | - | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 (MTD) | 6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| 3 | 3 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 |

| 4 | 3 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

Thirteen patients had treatment-related, grade 3 or 4 events [28.3%, (95% exact CI: 16% to 43%)]. For patients with treatment-related, grade 3 or 4 events, the table summarizes the number per patient.

Adverse events classified as “Not related” are included. Grades: 1 = Mild, 2 = Moderate, 3 = Severe, 4 = Life-threatening, 5 = Death.

Study Outcomes

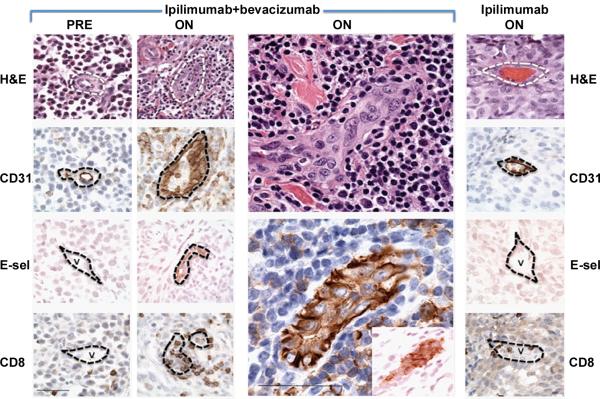

Treatment with ipilimumab plus bevacizumab resulted in morphologic changes in intratumoral endothelia with rounded and columnar CD31+ cells compared to pre-treatment or post-treatment samples from patients receiving ipilimumab alone (Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure 2). To illustrate variations in pathologic responses observed, examples of intermediate and no response is provided in Supplemental Figure 3. Increased expression of E-selectin as a function of therapy was observed with combined treatment relative to ipilimumab alone, revealing further biochemical evidence for endothelial activation by the addition of bevacizumab. Concentrated CD31 staining was observed at the interendothelial junctions (Supplemental Figure 2). Pathology review further revealed that these endothelial changes were associated with extensive immune cell infiltration of tumors. Vessel density was not affected significantly by bevacizumab therapy.

Figure 2.

Intratumoral blood vessel changes from treatment with bevacizumab plus ipilimumab in subcutaneous melanoma deposits. A. Characterization of tumor-associated vasculature before and while on therapy. Endothelial cells lining small vessels within melanomas of ipilimumab plus bevacizumab-treated patients were rounded and columnar as assessed by H&E and CD31 staining, in contrast to pre-treatment samples and on-treatment samples from patients receiving ipilimumab alone (column to extreme right; v = vessel). Scale bar = 50 microns. Endothelial cells in tumor deposits of patients receiving ipilimumab plus bevacizumab were also associated with increased expression of E-selectin, and adhesion and diapedesis of CD8+ T cells. Enlarged central panels highlight the focally occlusive appearance of this endothelial activation (top H&E, bottom CD31, [inset, E-selectin]). Base membrane of vessels approximated by dotted lines.

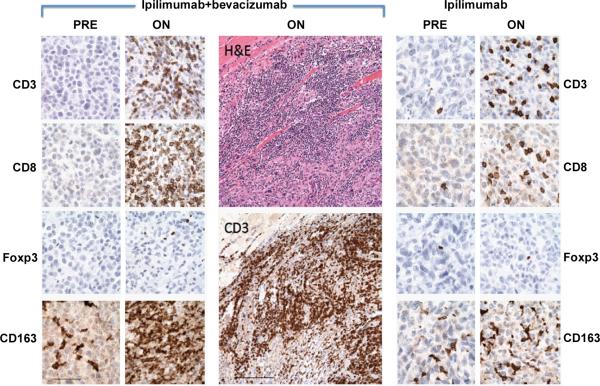

With pathologic examination of immune infiltrates associated with treatment, significant trafficking of CD8+ T cells and CD163+ dendritic macrophages (Figure 3) across the tumor vasculature was witnessed in ipilimumab plus bevacizumab post-treatment biopsies that were qualitatively increased in comparison to that elicited by ipilimumab alone. There was minimal change in FoxP3+ cellular composition.

Figure 3.

Histologic changes in tumor deposits resulting from treatment with bevacizumab plus ipilimumab. A. Phenotypic characterization of immune-cell infiltrates in biopsies from responders before and after initiation of therapy. Tumors after initiation (ON) of ipilimumab-bevacizumab therapy were characterized as compared to pre-treatment samples (PRE). Significant infiltration by CD3+CD8+ T cells and CD163+ macrophages with minimal change in Foxp3+ component were observed. The enlarged panels (center) emphasize the tumor-infiltrating architecture of the immune response (skeletal muscle is seen in the upper left corner). In contrast, patients treated only with ipilimumab demonstrated a lesser degree of immune-cell infiltration while on therapy. The two ipilimumab-bevacizumab specimens are subcutaneous tissues, and the ipilimumab alone specimen was from the oropharyngeal submucosa.

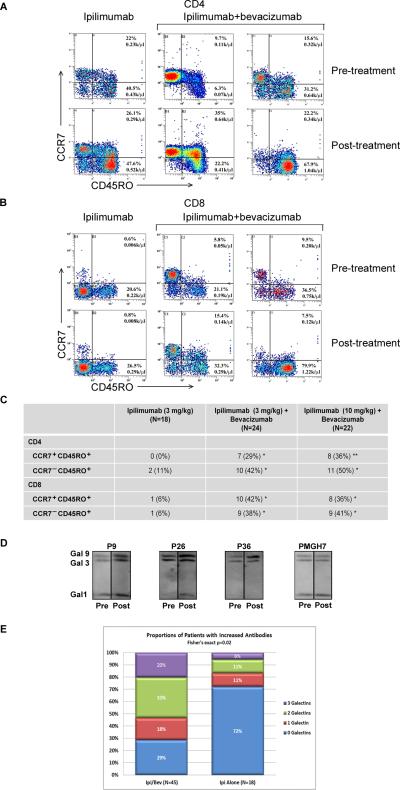

We next sought to identify altered immune responses resulting from bevacizumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy. To pursue functional changes, flow cytometry detecting T-cell phenotypes in the peripheral blood demonstrated enhancement in CCR7+/−CD45RO+ populations for CD4+ (Figure 4A) and CD8+ (Figure 4B) T cells (individual responses Supplemental Figure 4). Bevacizumab plus ipilimumab significantly increased circulating memory cell phenotypes compared to ipilimumab alone (Figure 4C). Furthermore, analyses with post-treatment sera using protein arrays identified galectin-1 and galectin-3 in 2 of 4, and 3 of 4 patients, respectively (Z factor = 0.49 and 0.7 for galectin-1, 0.58, 0.83 and 0.87 for galectin-3). Galectin-9 was not included in the protein array. Given its biologic significance in immune regulation, galectin-9 was included in subsequent analyses. The presence of anti-galectin antibodies in sera was further confirmed by immunoblot using recombinant proteins (Figure 4D). Patients who received ipilimumab plus bevacizumab had a significantly higher number of responses to galectins-1,-3,-9 than patients who received ipilimumab alone (Fisher's exact p=0.02) (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Cellular and humoral immune responses in the peripheral blood are altered by the addition of bevacizumab to ipilimumab. All samples were obtained pre-treatment and at week 12 at the completion of ipilimumab or ipilimumab-bevacizumab induction. A. Example of changes as a function of treatment in CD4+CCR7+CD45RO+ and CD4+CCR7−CD45RO+ T-cell populations to ipilimumab plus bevacizumab treatment, compared to changes with ipilimumab treatment alone. B. Example of changes as a function of treatment in CD8+CCR7+CD45RO+ and CD8+CCR7−CD45RO+ T-cell populations to ipilimumab plus bevacizumab treatment, compared to the responses to ipilimumab treatment alone. C. Numbers of melanoma patients that have at least 50% enhancement in CD4+/CD8+ CCR7+CD45RO+ and CD4+/CD8+ CCR7−CD45RO+ T-cell populations following treatment with ipilimumab (3mg/kg), or ipilimumab (3mg/kg) plus bevacizumab, or ipilimumab (10mg/kg) plus bevacizumab. * indicates P<0.05 between ipilimumab and ipilimumab plus bevacizumab. ** indicates P<0.01. D. Representative immunoblots of antibody responses in four bevacizumab plus ipilimumab-treated patients to a total of zero, one, two, or three galectins. Arrows indicate increased antibody levels in post-treatment sera samples. Galectin-1, -3 and -9 proteins were mixed together and equally loaded and separated by gel electrophoresis. Following transfer onto a membrane, strips were incubated with equally diluted pre-treatment and post-treatment sera. Density analysis using the NIH ImageJ software confirmed the increases in densities of the indicated bands after subtracting background taken from nearby areas of each band. As in most of the cases, density change was seen in only one or two of the 3 galectins, protein(s) without density change serving as loading controls. E. Antibody responses to galectins in patients treated with bevacizumab plus ipilimumab and ipilimumab alone. Anti-galectin-1, -galectin-3, and -galectin-9 antibodies were detected in pre-treatment and post-treatment patient sera by immunoblot analyses. Percentages of patients with increased levels of antibodies to a total of zero, one, two, or three galectins in bevacizumab plus ipilimumab-treated patients (n=45) and ipilimumab alone patients (n=18). Density of each band was measured using the NIH ImmageJ software and the antibody fold-change was calculated using the formula: Fold-change = (DensityPost – DensityPre)/DensityPre. Antibody levels were considered as increased when the fold-change ≥ 0.5.

Efficacy

Median follow-up at the time of this analysis was 17.3 months (95% CI; 11.1 to 30.2 months). Thirty-nine (85%) patients stopped treatment, and seven remain on study. Nine patients (23%) discontinued treatment due to toxicity, 29 (74%) due to progressive disease, and one (3%) due to withdrawal of consent. The median number of cycles patients received was 7 (range: 2 to 37).

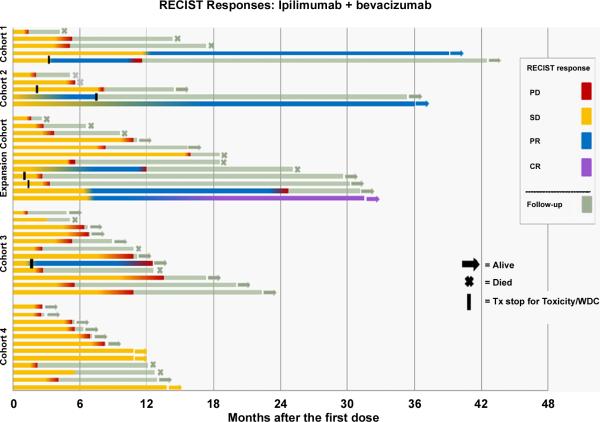

The 12-week response for the entire treated patient population was 10.9% (95% exact CI: 4% to 24%) (highest cohort 2: 17.6%). Clinical activity is shown in Figure 5. BORR was 19.6% (95% exact CI: 9% to 34%) (highest cohort 2: 29.4% (95% exact CI: 10% to 56%)(1CR)) (Supplemental Table 4). In addition to examples of pseudoprogression (Figure 6), delayed best responses (Supplemental Figure 5) were observed. Response kinetics for all patients are presented in Supplemental Figure 6A and for cohort 2 (MTD) in Supplemental Figure 6B. DCR for all patients was 67.4% (95% exact CI: 52% to 81%) (cohort 2 76.5% (95% exact CI: 50% to 93%)). There were no statistical differences in the response or DCR between cohorts. Most durable responses, achieved best response after months of therapy. One patient in cohort 2 (MTD) experienced 7 months of stable disease before a partial response and subsequently had a complete response beginning 17 months following the initiation of therapy. Eleven patients in cohorts 1 and 2 are alive months after discontinuation of therapy. The median TTP was 9.0 months (95% CI 5.5 to 14.5 months) (longest cohort 2: 14.5 months (95% CI 3.8 to ∞) (Supplemental Figure 7). There were no differences in PFS by cohort (log-rank p=0.32).

Figure 5.

Activity in treated patients by cohort according to RECIST criteria. Arrows indicate alive at the time of analysis. Crosses indicate death. Black bars indicate discontinuation of treatment other than due to progressive disease. Five patients came off trial due to toxicity requiring systemic steroids. One patient withdrew consent after week 12 without dose-limiting toxicity. PD= progressive disease. SD = stable disease. PR = partial response. CR = complete response.

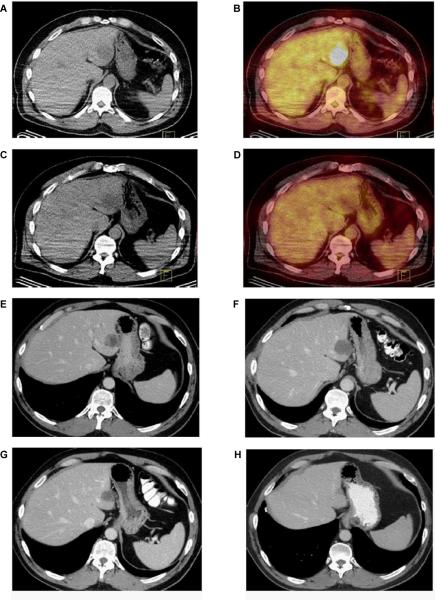

Figure 6.

Example of pre-treatment (A and B) and 8-week post-treatment (C and D) PET CT images. An early metabolic response is noted in a dominant left hepatic metastasis. E. Axial contrast-enhanced CT image obtained at baseline demonstrates a solitary heterogeneous hypodense lesion in segment II of the liver consistent with a metastatic deposit. F. Axial contrast-enhanced CT obtained 4 months after treatment demonstrates slight increase in the lesions with interval decrease in density (from 40 HU to 19 HU, approximately 50%) consistent with treatment effect. The increase in size represents pseudo-progression. G and H. Follow-up CT scans obtained 6 and 36 months after the start of treatment demonstrate gradual decrease in size of the metastatic deposit.

Radiographic evidence for early metabolic antitumor responses without significant anatomic response was exemplified with PET/CT imaging (Figure 6A-D). Transient increases in lesion size with decreased density prior to gradual decrease in size with subsequent imaging (Figure 6E-H) were observed in a number of patients consistent with pseudoprogression

Thirty (65%) patients were alive at the time of data retrieval. Kaplan-Meier estimates for TTP and overall survival are shown in Supplemental Figure 7. Median overall survival was 25.1 months (95% CI: 12.7 to ∞) (cohort 2: 25.1 months (95% CI: 9.6 to ∞). There were no differences in overall survival by cohort (log-rank p=0.98). Kaplan-Meier estimate of 1-year OS was 79% (95% CI 62% to 89%) and 6-month TTP was 63% (95% CI 47% to 75%). The lower bounds of both confidence intervals exceed those of Korn et al (14).

Discussion

The influences on immunologic effects witnessed with the addition of bevacizumab to ipilimumab reveal novel mechanisms of action for bevacizumab in patients. First, morphologic and biochemical alterations in the tumor vasculature resulted in endothelial activation associated with qualitative increases in lymphocyte and myeloid/monocyte cell trafficking into tumor deposits. The monocytes had extensive dendritic processes. These patterns of immune infiltrates for some patients were associated with transient increases in lesion size with decreased density prior to gradual decrease in size with subsequent imaging. Detailed characterization of these infiltrates and cellular functions are areas of future investigation. Vessel changes were similar to those observed in high endothelial venules (HEV) found in secondary lymphoid organs and associated with lymphocyte extravasation (15). Such endothelial appearances correlated with the ability for lymphocytes to migrate into tissues. E-selectin expression induced by bevacizumab facilitates lymphocyte adhesion and rolling (16). In addition, CD31 influences adhesive and signaling functions for vascular cellular extravasation (17,18). Specifically, the concentration of CD31 staining at the interendothelial junctions of bevacizumab plus ipilimumab treated specimens indicates vessels adapted for efficient lymphocyte trafficking (19). These results are consistent with previous observations of anti-VEGF treatment increasing lymphocyte tumor infiltrates in adoptive therapy models (20,21).

Further evidence for immunologic changes by the combination was demonstrated in the peripheral blood through increasing circulating memory T cells resulting from the addition of bevacizumab. This provides a definitive role for bevacizumab in affecting broad changes in the circulating immune composition. Furthermore, the coordinated T- and B-cell responses witnessed previously with checkpoint blockade (22,23) are confirmed by the increased antibody recognition of the galectin family members. This suggests that the concerted effects of combination therapy can result in additional immune recognition that extends implications for both immune regulation as well as angiogenesis. As the galectin family members are involved in tumor-cell invasion, metastases, angiogenesis as well as immune regulation, it will be important to define in future studies the functions of these antibodies and their potential therapeutic roles.

In pre-clinical animal models and in humans, VEGF has been associated with altered antitumor immune responses including the suppression of dendritic-cell maturation (3,4), proliferation of regulatory T cells, inhibition of T-cell responses (24), and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) (25-27). In colorectal cancer patients, bevacizumab improved the antigen-presenting capacity of circulating dendritic cells (28). The increase in dendritic-cell infiltrates associated with the current study suggests a role for VEGF blockade in influencing the association of antigen presenting cell with tumor cells and their maturation. This reveals an additional mechanism for bevacizumab on immune function in the context of checkpoint blockade.

Inflammatory toxicities were generally higher than expected with ipilimumab alone, but remained manageable. These included rare vasculitic events suggesting immune recognition of unique sets of antigens (29) and eosinophilic driven processes. Importantly, there did not appear to be an increased incidence of dermatologic or gastrointestinal side effects such as colitis which are most concerning for ipilimumab. As such, the combination of blocking CTLA-4 and VEGF-A may broaden the recognized antigen repertoire.

Recent clinical trials reporting survival outcomes for patients with metastatic melanoma have led to regulatory approval for ipilimumab and vemurafenib. Phase II trials of ipilimumab revealed two-year survival rates of 24.2-32.8% (30,31). In patients who had received at least one prior therapy, ipilimumab when compared to a gp100 peptide vaccine improved the median overall survival from 6.4 to 10.1 months (1). Overall survival in previously treated melanoma patients receiving vemurafenib was 15.9 months (32). In the current phase I trial combining bevacizumab and ipilimumab, the clinical activity was favorable compared to ipilimumab alone. As all but one partial response occurred in cohorts 1 and 2 (10 mg/kg ipilimumab), the ipilimumab dose may influence the efficacy when combined with bevacizumab. The median survival of the entire 46-patient cohort was greater than two years with significant antitumor activity witnessed at the MTD. With the lower bounds of both confidence intervals exceeding that of Korn et al (14), this combination is worthy of further pursuit. Importantly, these results establish a mechanistic foundation for combining anti-angiogenesis with immune checkpoint blockade for cancer treatment.

Antiangiogenic therapy for cancer has traditionally provided a means to limit the blood supply and improve delivery of anti-neoplastic agents to tumor sites. When combined with chemotherapy or interferon, bevacizumab has proven efficacious at improving the outcomes of patients with colorectal cancer, renal cell carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and glioblastoma multiforme (7-11,33,34).

For many tumors, hypoxia creates a microenvironment of inhibitory inflammatory cells (26,35). The role of angiogenic factors in suppressing inflammation in order to promote vessel growth has increasingly been recognized in the context of tumor immunology (35). The ability to counteract the dual function of angiogenic factors in promoting vessel growth and suppressing immune responses is provided in the current study by the parallel effects on host immunity and tumor vasculature. Mechanisms defining the roles for bevacizumab in the context of immune checkpoint blockade were uncovered. The combination provoked inflammatory events in patients, promoted memory cells circulating in the peripheral blood, enhanced intratumoral trafficking of effector cells, and improved endogenous humoral immune responses to galectins. Further investigation is needed to evaluate the mechanistic basis of bevacizumab activity and the full impact of clinical activity. Continued development of immune checkpoint and anti-angiogenic combination therapies are warranted for the treatment of melanoma and other cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding provided by NIH CA143832 (F.S.H.), the Melanoma Research Alliance (F.S.H.), the Sharon Crowley Martin Memorial Fund for Melanoma Research (F.S.H.) and the Malcolm and Emily Mac Naught Fund for Melanoma Research (F.S.H.) at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Genentech/Roche, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Hodi has served as a non-paid consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb and Genentech/Roche. Dr. Hodi reports research support to his institution from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Genentech/Roche. Dr. Atkins reports serving as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, and Prometheus and scientific advisory board to Costim and CCam. Dr. Flaherty reports serving as a consultant to Roche/Genentech. Dr. McDermott reports serving as a paid advisory board participant to Bristol-Myers Squibb and Genentech.

References

- 1.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved Survival with Ipilimumab in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O'Day S, Weber JW, Garbe C, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohm JE, Carbone DP. VEGF as a mediator of tumor-associated immunodeficiency. Immunol Res. 2001;23:263–72. doi: 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oyama T, Ran S, Ishida T, Nadaf S, Kerr L, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Vascular endothelial growth factor affects dendritic cell maturation through the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B activation in hemopoietic progenitor cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1224–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandalaft LE, Motz GT, Busch J, Coukos G. Angiogenesis and the tumor vasculature as antitumor immune modulators: the role of vascular endothelial growth factor and endothelin. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;344:129–48. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodi FS, Mihm MC, Soiffer RJ, Haluska FG, Butler M, Seiden MV, et al. Biologic activity of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody blockade in previously vaccinated metastatic melanoma and ovarian carcinoma patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4712–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830997100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braghiroli MI, Sabbaga J, Hoff PM. Bevacizumab: overview of the literature. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:567–80. doi: 10.1586/era.12.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Husein B, Abdalla M, Trepte M, Deremer DL, Somanath PR. Antiangiogenic therapy for cancer: an update. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:1095–111. doi: 10.1002/phar.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amit L, Ben-Aharon I, Vidal L, Leibovici L, Stemmer S. The impact of Bevacizumab (Avastin) on survival in metastatic solid tumors--a meta-analysis and systematic review. PloS One. 2013;8:e51780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyake TM, Sood AK, Coleman RL. Contemporary use of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13:283–94. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.745508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeung Y, Tebbutt NC. Bevacizumab in colorectal cancer: current and future directions. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:1263–73. doi: 10.1586/era.12.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khasraw M, Simeonovic M, Grommes C. Bevacizumab for the treatment of high-grade glioma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:1101–11. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.694422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Small AC, Oh WK. Bevacizumab treatment of prostate cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:1241–9. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.704015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korn EL, Liu PY, Lee SJ, Chapman JA, Niedzwiecki D, Suman Vj, et al. Meta-analysis of phase II cooperative group trials in metastatic stage IV melanoma to determine progression-free and overall survival benchmarks for future phase II trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:527–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson-Leger C, Aurrand-Lions M, Imhof BA. The parting of the endothelium: miracle, or simply a junctional affair? J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 6):921–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.6.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borgstrom P, Hughes GK, Hansell P, Wolitsky BA, Sriramarao P. Leukocyte adhesion in angiogenic blood vessels. Role of E-selectin, P-selectin, and beta2 integrin in lymphotoxin-mediated leukocyte recruitment in tumor microvessels. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2246–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI119399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marelli-Berg FM, Clement M, Mauro C, Caligiuri G. An immunologist's guide to CD31 function in T-cells. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:2343–52. doi: 10.1242/jcs.124099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma L, Cheung KC, Kishore M, Nourshargh S, Mauro C, Marelli-Berg FM. CD31 exhibits multiple roles in regulating T lymphocyte trafficking in vivo. J Immunol. 2012;189:4104–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller WA. The role of PECAM-1 (CD31) in leukocyte emigration: studies in vitro and in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:523–8. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shrimali RK, Yu Z, Theoret MR, Chinnasamy D, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA. Antiangiogenic agents can increase lymphocyte infiltration into tumor and enhance the effectiveness of adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6171–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kandalaft LE, Motz GT, Duraiswamy J, Coukos G. Tumor immune surveillance and ovarian cancer: lessons on immune mediated tumor rejection or tolerance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30:141–51. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodi FS, Butler M, Oble DA, Seiden MV, Haluska FG, Kture A, et al. Immunologic and clinical effects of antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 in previously vaccinated cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3005–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712237105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan J, Gnjatic S, Li H, Powel S, Gallardo HF, Ritter E, et al. CTLA-4 blockade enhances polyfunctional NY-ESO-1 specific T cell responses in metastatic melanoma patients with clinical benefit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20410–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810114105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terme M, Pernot S, Marcheteau E, Sandoval F, Benhamouda N, Colussi O, et al. VEGFA-VEGFR pathway blockade inhibits tumor-induced regulatory T-cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:539–49. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:253–68. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Goel S, Duda DG, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Vascular normalization as an emerging strategy to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2943–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terme M, Colussi O, Marcheteau E, Tanchot C, Tartour E, Taieb J. Modulation of immunity by antiangiogenic molecules in cancer. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:492920. doi: 10.1155/2012/492920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osada T, Chong G, Tansik R, Hong T, Spector N, Kumar R, et al. The effect of anti-VEGF therapy on immature myeloid cell and dendritic cells in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1115–24. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0441-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Giant cell arteritis as an antigen-driven disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1995;21:1027–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolchok JD, Neyns B, Linette G, Negrier S, Lutzky J, Thomas L, et al. Ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2, dose-ranging study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:155–64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Day SJ, Maio M, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gajweski TF, Pehamberger H, Bondarenko IN, et al. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a multicenter single-arm phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1712–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, Pavlick AC, Weber JS, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:707–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber HP, Novotny W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heitz F, Harter P, Barinoff J, Beutel B, Kannisto P, Grabowski JP, et al. Bevacizumab in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Adv Ther. 2012;29:723–35. doi: 10.1007/s12325-012-0041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tartour E, Pere H, Maillere B, Terme M, Merillon N, Taieb J, et al. Angiogenesis and immunity: a bidirectional link potentially relevant for the monitoring of antiangiogenic therapy and the development of novel therapeutic combination with immunotherapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30:83–95. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.