Abstract

This study examined the influences of age and chronic physical activity status on appetite and mood state. Groups of younger inactive (YI); younger active (YA); older inactive (OI); and older active (OA) men and women completed questionnaires each waking hour rating appetite and mood state for one day. Maximal oxygen consumption was 20% lower in O vs. Y (p<0.001) and 32% lower in I vs. A (p<0.001). Mean hunger (O 4±1, Y 5±1 arbitrary units (au), p<0.01) and desire to eat (O 3±1, Y 4±1 au, p<0.01) were lower in O vs. Y. Nadir arousal was higher for the active subjects (A 3±1, I 2±1 au, p<0.05). Nadir arousal, nadir pleasantness, and mean pleasantness were higher for the older subjects (p<0.05). Physical activity status does not influence appetite or the age-associated declines in hunger and desire to eat. The increased nadir arousal of the physically active and older groups of subjects is consistent with these subjects experiencing less extreme sleepiness.

Keywords: Arousal, Elderly, Exercise, Hunger, Fullness, Pleasantness, Aging

Introduction

With advancing age, adults experience a decline in appetite and food intake (Chapman et al. 2002), and in the extreme could lead to severe weight loss and malnutrition (Morley 1997). Undesired weight loss may involve social, psychological, and medical issues (Morley 1997). Free living and institutionalized older persons who experience weight loss often are psychologically depressed (Katz et al. 1993; Thompson and Morris 1991), and treatment for the depression has been shown to help these persons regain weight (Morley 1997). If weight loss goes untreated, it generally has detrimental outcomes (Wilson and Morley 2003) including increased number of falls, injuries from falls, and mortality (Hays and Roberts 2006). The overall phenomenon of declining appetite and food intake in older persons is deemed the ‘anorexia of aging’ (Morley 1997).

In a cross-sectional investigation, physically active older people were reported to have increased levels of vitality (conscious experience of possessing energy and aliveness (Ryan and Frederick 1997)) when compared to inactive older people (Stewart et al. 2003). Furthermore, aerobic fitness was a strong predictor of higher physical functioning, vitality, and lower mood disturbance (Stewart et al. 2003). Longitudinal studies (Vuillemin et al. 2005; Wendel-Vos et al. 2004) have indicated positive correlations between higher physical activity, higher vitality, and quality of life. In a randomized controlled trial, aerobic exercise was shown to increase vitality and general health in older persons (Kerse et al. 2005).

During short and medium term intervention studies, low to moderate-intensity exercise is generally not considered to influence appetite control on the day of exercise in younger persons (Blundell and King 1999; King et al. 1997). Acute high-intensity exercise has been reported in younger persons to transiently decrease hunger for 15–60 min post exercise and is known as ‘exercise-induced anorexia’ (Bellisle 1999). Currently, it is generally accepted that there is a loose coupling of energy expenditure between exercise and dietary intake over the long-term (King 1999). However, the relationships among energy balance, appetite, and chronic physical activity status are poorly understood. Limited data indicate that younger persons who habitually exercise have an increased ability to acutely compensate for energy intake (Long et al. 2002). The ability of older persons to compensate for energy intake is likely important in the maintenance of energy balance and prevention of the ‘anorexia of aging’. To our knowledge, the influence of chronic physical activity on appetitive indices has not been studied in healthy, older persons.

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to determine the influences of age and physical activity status on short-term indices of appetite (hunger, desire to eat and fullness) and mood state (dimensions of pleasure-displeasure and arousal-sleepiness). We hypothesized that older subjects would have lower hunger and desire to eat, and higher fullness than the younger subjects. We further hypothesized that independent of age, physical activity status would have no effect on appetite. Regarding mood state, we hypothesized that physical activity status, but not age, would increase arousal.

Methods

Screening and Subjects

Potential participants responded to advertisements and flyers recruiting physically active and inactive individuals. A phone interview was used to assess physical activity status which was defined as active: moderate physical activity on most ≥ 4 days of the week, inactive: < 20 min/day of physical activity two or fewer days/week. The phone interview was discontinued if the participant did not fit into the active or inactive group based on these definitions. The phone interview was further used to exclude people with diabetes, elevated serum cholesterol, autoimmune diseases, and cardiovascular disease. The volunteers were screened and accepted based on aerobic physical activity; however the active subjects (younger and older) participated in a variety of forms of exercise. Following the phone interview, qualified subjects completed a medical history questionnaire and had to meet the inclusion criteria previously described (McFarlin et al. 2006). Each of the 61 qualified participants who chose to participate received oral and written explanations of the purpose and procedures of the study and signed an informed consent document. The study was approved by the Purdue University Committee on the Use of Human Research Subjects and complied with HIPAA guidelines. Upon completion, each subject received a monetary stipend.

Body fat percentage was estimated using a handheld bioelectrical impedance unit of the 61 qualified participants (BIA; Omron Healthcare, Bannockburn, IL) (Houtkooper et al. 1996). Fasting weight and height were measured. A Paffenbarger physical activity questionnaire (Pereira et al. 1997) was administered to determine hours of daily activity. Aerobic fitness was assessed by estimating maximum oxygen consumption using the modified Balke protocol (Franklin 2000) to 85% of estimated heart rate maximum. Group assignments were determined by comparing the participant’s VO2max and physical activity questionnaire scores. Inactive participants had a VO2max which was below average for their age group (Franklin 2000) and a sedentary lifestyle which was <1000 kcal/week based on their estimated weekly energy expenditure from the activity questionnaire. Active participants had a VO2max that was at least above average for their age group (Franklin 2000) and an active lifestyle that was defined as >2500 kcal/week based on the activity questionnaire. If the Paffenbarger physical activity questionnaire and estimated VO2max did not indicate the same status for a given participant, that participant was excluded from the study (n=5). In all 5 excluded subjects, their Paffenbarger questionnaire report suggested that they were highly trained, while their estimated VO2max suggested that they were of below average fitness (according to ACSM standards). Fifty-six persons completed the non-randomized, cross-sectional study. At time of the phone interview, subjects were assigned to one of four groups (completed subject numbers shown): younger physically active (YA; 7 male and 4 female), younger physically inactive (YI; 8 male and 5 female), older physically inactive (OI; 8 male and 8 female), older physically active (OA; 8 male and 8 female).

Appetite Questionnaires

Appetite was assessed during one non-exercising 24-hour period. Each subject completed the appetite questionnaire hourly during waking hours. After the subject awoke, they were asked to start completing the questionnaires on the nearest quarter hour. The following questions (Rogers and Blundell 1979) were asked, starting with ‘How strong is your’: feeling of hunger?; feeling of fullness?; desire to eat? On the scale, there were 13 evenly spaced dashes which were scored 1–13 (DiMeglio and Mattes 2000). The 1 represented ‘Not at all’ and the 13 represented ‘Extremely’. The subjects were instructed to circle the vertical dash along the horizontal line corresponding to their feelings at that moment.

Mood State

Concurrent with each appetite questionnaire, all volunteers were requested to fill out a single item affect grid to determine mood state (Russell et al. 1989). The grid consisted of one large square box and within that large box were 81 smaller boxes (9 × 9). At each corner of the box were emotional states (i.e. stress, upper left; depression, lower left; excitement, upper right; relaxation, lower right) with emotional scales in between (high arousal, top center; sleepiness, bottom center; pleasant feelings, right center; unpleasant feelings, left center). The subjects determined their perceived pleasure and arousal at the moment of completion by placing one ‘X’ within the grid.

Food Records

All subjects were counseled on how to maintain a proper food record by a registered dietitian. The subjects were instructed using verbal and written instructions to include the method of preparation, portion size, brand name of the item, whether it was fresh, frozen, or canned, and time of consumption. The food record was to include all food and beverages with a request of a detailed description for each item. The subjects were specifically instructed to measure and record such items as gravy, salad dressings, sauces, and condiments. Furthermore, the subjects were instructed to measure the portion size (quantity) of each item. To help with portion size when food items could not be measured, participants were trained to estimate food intake with NASCO food models. The 24-h food record was completed on the same day as the appetite and mood state questionnaires. Food records were analyzed using Nutritionist Pro software (Nutritionist Pro, First DataBank version 1.3.36, San Bruno, CA) for energy, protein, carbohydrate, fat, and fiber. Post analysis, the age and sex-specific Schofield equations (Schofield 1985) were used to establish each subjects basal metabolic rate. Valid food records were determined using previously established lower and upper 95% confidence limit (CL) intervals (Energy intake: Basal metabolic rate cutoffs; lower 95% CL 0.87, upper 95% CL 2.75) (Black 2000). Data from 48 of the 56 subjects (9 YI, 10 YA, 14 OI, and 15 OA) met this criterion and were used in the analyses. Eight subjects with implausible food records out of 56 subjects (14.3%) represents a low to comparable number of under-reporters which would be expected based on previous studies (Huang et al. 2005). All other data from these 8 subjects were retained and used in non-food record analyses.

Statistical Analyses

All values are reported as mean ± SEM. Data were normally distributed. For the appetite questions and mood state grid, daily peak, mean, and nadir values were analyzed. Nadir and peak represent the range of extremes and demonstrate whether the subject’s appetitive sensations and mood states were consistent or oscillated throughout the day. Another reason peak and nadir values are reported is to evaluate if the group average peak or group average nadir was at the maximum or minimum of the scale possibly biasing the results and conclusions.

All factors were compared using a 2 (age: younger and older; physical activity status: physically active and physically inactive) factor ANOVA model on SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Analyses of co-variance (ANCOVA) using estimated VO2max as the covariate was used to further investigate the effects that training status had on appetite and mood state. The correlations were established using the Spearman Rho non-parametric ranked correlation test.

Results

Subject Characteristics

Body mass index and body fat percent were lower and maximal oxygen consumption and hours of activity were higher for YA and OA, compared to YI and OI (Table 1). Independent of activity status, the older persons (OA and OI pooled) had higher body fat and lower maximum oxygen consumption compared to younger persons (YA and YI pooled).

TABLE 1.

Physical Characteristics of Subjects

| Subjects | Age* | Weight† | BMI† | Body Fat*† | VO2 Max*† | Activity† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (years) | (kg) | (kg/m2) | (%) | (mL·kg−1·min−1) | (h/d) | |

| Young Inactive | 13 | 25±1 | 78.1±4.9 | 26.6±1.0 | 23.1±1.4 | 33.7±1.6 | 0.0±0.0 |

| Young Active | 11 | 25±1 | 72.5±3.4 | 23.5±0.6 | 15.7±1.9 | 47.5±1.9 | 2.6±0.2 |

| Old Inactive | 16 | 69±1 | 79.4±3.9 | 27.7±1.0 | 35.2±2.0 | 25.0±1.4 | 0.2±0.1 |

| Old Active | 16 | 72±1 | 68.7±2.5 | 24.2±0.7 | 32.1±1.8 | 39.5±2.0 | 2.8±0.2 |

Values are mean±SEM.

VO2 max, estimated maximal oxygen consumption; Activity, physical activity, h, hours; d, day

Age effect, p<0.05.

Activity effect, p<0.05.

Appetite Questionnaires

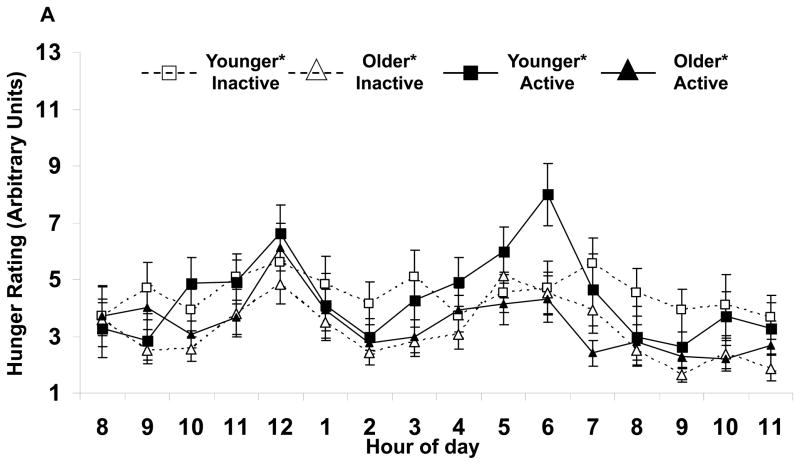

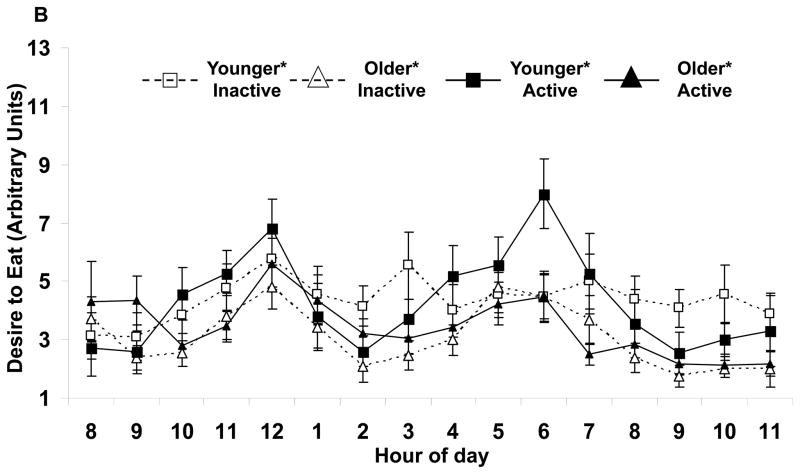

Appetite responses were altered by age, but not activity status (Table 2). Independent of activity, the older subjects had lower mean hunger (Fig. 1A) and desire to eat (Fig. 1B). No differences were found with the perception of fullness. Also, peak hunger and desire to eat, but not fullness responses were lower for the older subjects. No age by activity status interactions were seen.

TABLE 2.

Mean daily values for appetite and mood state ratings for physically active and physically inactive younger and older persons

| Hunger | Fullness | Desire to Eat | Arousal | Pleasantness | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ave* | Nadir | Peak* | Ave | Nadir | Peak | Ave* | Nadir | Peak* | Ave | Nadir*† | Peak | Ave* | Nadir* | Peak | |

| YI | 5±0 | 2±0 | 10±1 | 7±1 | 3±1 | 12±0 | 4±0 | 2±0 | 10±1 | 5±1 | 2±0 | 7±1 | 6±0 | 3±1 | 8±1 |

| YA | 5±0 | 1±0 | 10±1 | 7±1 | 3±1 | 11±1 | 4±0 | 1±0 | 10±1 | 5±1 | 2±0 | 7±0 | 6±0 | 4±0 | 7±0 |

| OI | 3±0 | 1±0 | 8±1 | 7±1 | 3±1 | 10±1 | 3±0 | 1±0 | 8±1 | 5±1 | 2±0 | 7±0 | 7±0 | 5±0 | 8±0 |

| OA | 4±0 | 2±0 | 9±1 | 7±1 | 3±0 | 11±1 | 4±0 | 2±0 | 9±1 | 5±1 | 3±0 | 7±0 | 7±0 | 5±0 | 8±0 |

Values are mean±SEM in arbitrary units (AU).

Ave, Average; YI, Young Inactive; YA, Young Active; OI, Old Inactive; OA, Old Active

Age effect, p<0.05.

Activity effect, p<0.05.

FIGURE 1.

Hourly average feelings of (A) hunger and (B) desire to eat for each group of subjects. Values are mean±SEM.

*Age effect (active and inactive subjects combined) for average values, p<0.05.

When adjusted for VO2max using ANCOVA analyses, the mean hunger and desire to eat relationships for age remained significant (p<0.05), but the peak hunger and desire to responses were no longer significantly different for age. No other activity status or age by activity status interactions were seen with ANCOVA analyses.

Mood State

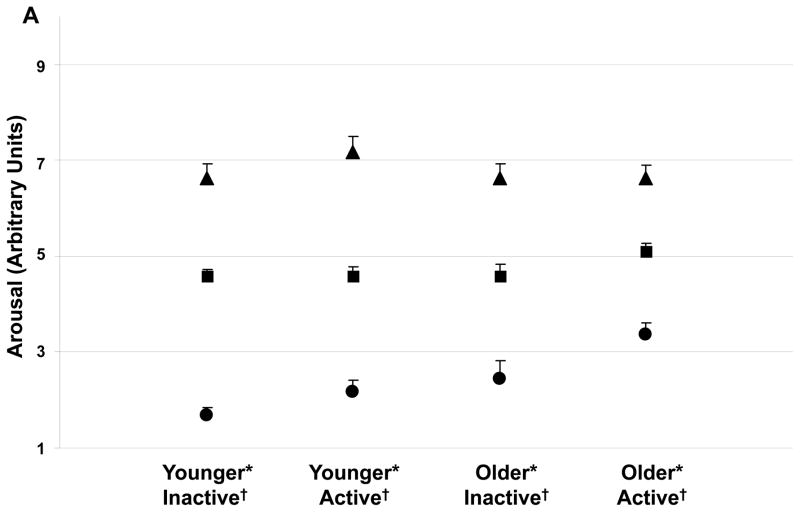

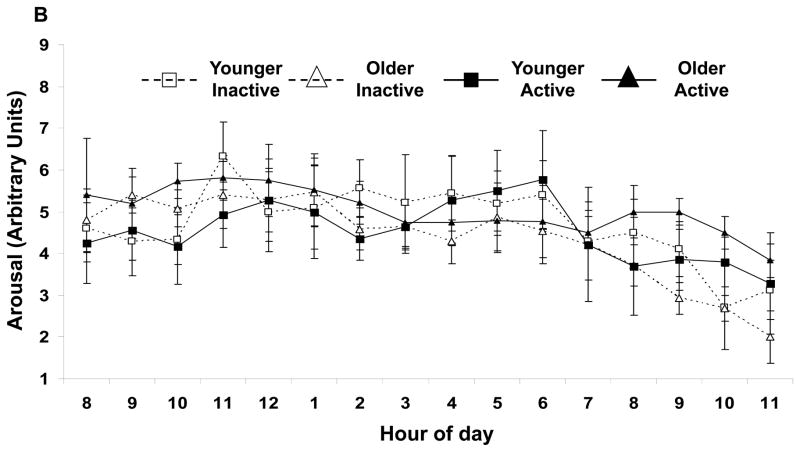

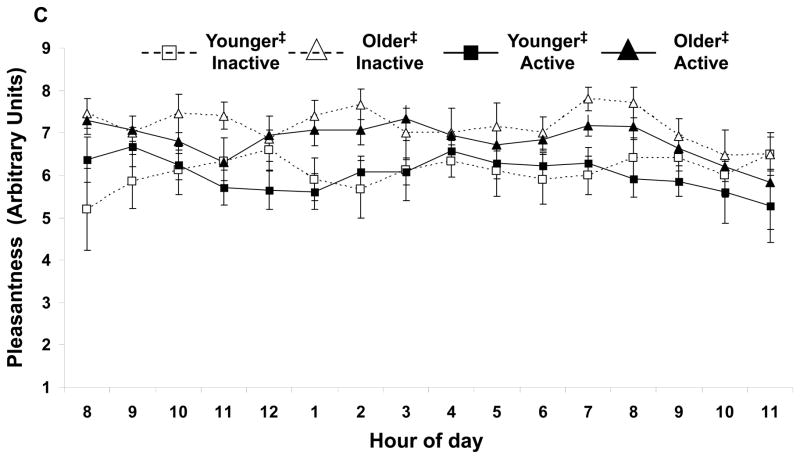

Independent of age, physically active subjects had a higher nadir arousal (Figure 2A). No other activity effects were shown with arousal (Figure 2B) or pleasantness. Independent of activity status, nadir arousal was higher in the older subjects. Daily mean and nadir pleasantness were higher in the older subjects (Fig. 2C) respectively. No age by activity status interactions were observed.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Daily (▲) peak, (■) average, and (●) nadir arousal for each group of subjects. Activity status and age affect nadir arousal. The minimum arousal state was higher for the physically active subjects (independent of age, p<0.05) and for the older subjects (independent of physical activity status, p<0.01). For each group of subjects, hourly average feelings of (B) arousal and (C) pleasantness are shown. Average arousal was not affected by age or activity, but average pleasure was higher in the older subjects (independent of physical activity status, p<0.05). Values are mean±SEM.

*Age effect (active and inactive subjects combined) for nadir value, p<0.01.

†Activity effect (younger and older subjects combined) for nadir value, p<0.05.

‡Age effect (active and inactive subjects combined) for average values, p<0.05.

When adjusted for VO2max using ANCOVA analyses, the physical activity nadir arousal response remained significant (p<0.05). The age related nadir arousal response as well as the daily mean pleasantness remained significant (p<0.05). However, age related nadir pleasantness was no longer significant between the younger and older subjects. No age by activity interactions were observed.

Appetite and Mood State Correlations

Average desire to eat and peak arousal (r=−0.32), nadir hunger and nadir pleasantness (r=0.23), and nadir desire to eat and nadir pleasantness (r=0.24) were all correlated (p<0.05). No other statistically significant correlations were seen.

Food Records

Independent of activity status, the older subjects consumed less total protein and carbohydrate than the younger persons (Table 3). No difference was seen with total energy, fat, alcohol, or fiber. No physical activity status differences were observed for energy or macronutrient composition. As a percentage of energy, no differences in macronutrient intakes were observed for protein or carbohydrate (p>0.05). Active vs. inactive individuals consumed less of fat (% energy, p<0.05). As a percentage of energy, younger inactive subjects consumed less alcohol than the younger active, older inactive, and older active subjects (p<0.05).

TABLE 3.

Dietary Energy and Macronutrient Intake Data

| Subjects | Energy | Protein | Carbohydrate | Fat | Alcohol | Fiber | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (MJ/d) | (MJ/kg·d) | (g/d)* | (%) | (g/d)* | (%) | (g/d) | (%)† | (g/d) | (%)‡ | (g/d) | |

| YI | 9 | 9.17±1.04 | 0.13±0.01 | 103±14 | 16.4±1.0 | 320±34 | 52.3±3.1 | 83±9 | 31.3±3.0 | 0±0 | 0.0±0.0 | 23±3 |

| YA | 10 | 9.56±0.95 | 0.14±0.01 | 102±16 | 16.9±2.1 | 340±33 | 57.2±3.9 | 71±12 | 25.0±2.8 | 3±2 | 1.0±0.7 | 22±3 |

| OI | 14 | 8.71±0.49 | 0.11±0.01 | 82±6 | 15.4±0.7 | 285±18 | 53.6±1.8 | 70±6 | 29.5±1.6 | 5±2 | 1.6±0.6 | 25±2 |

| OA | 15 | 7.88±0.41 | 0.12±0.01 | 84±5 | 17.0±0.8 | 274±11 | 55.5±1.3 | 59±4 | 26.5±1.4 | 3±2 | 1.1±0.7 | 25±1 |

Values are mean±SEM.

YI, Young Inactive; YA, Young Active; OI, Old Inactive; OA, Old Active

Age effect, p<0.05.

Activity effect, p<0.05.

Age by activity status interaction with young inactive different than young active, old inactive, old active (p<0.05).

The conversion factor from MJ/d and MJ/kg·d to kcal/d and kcal/kg·d is to multiply by 238.85.

When adjusted for VO2max using ANCOVA analyses, no significant relationships were seen.

Discussion

One primary finding from this study is that a younger and older person’s physical activity status does not appear to influence daily perceptions of appetite. Previous research on physical activity and appetitive response has focused on young to middle-aged individuals (Durrant et al. 1982; Hubert et al. 1998; Thompson et al. 1988) or frail, elderly individuals (de Jong et al. 2000; Fiatarone et al. 1994), but not a healthy older population or a comparison between younger and older adults. The current findings coincide with the previous original research (Durrant et al. 1982; Hubert et al. 1998; Thompson et al. 1988) and with interpretive review articles (Blundell and King 1999; Blundell et al. 2003; King et al. 1997) that support that exercise does not affect appetitive responses.

The volunteers used in this study were not competitive athletes. However, the approximate 14 mL/kg•min difference in estimated maximal aerobic capacity between the inactive and active groups supports the differential activity status. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) has developed a chart, separated by age, which explains the percentile values for maximal aerobic capacity (Franklin 2000). Our study population was similar to the population assembled to generate the chart and the same estimated treadmill test was performed. Our data support that it is appropriate to use across a wide range of clinical statuses. The following are the descriptors used: 90, well above average; 70, above average; 50, average; 30, below average; 10, well below average. In the current study, based on ACSM guidelines, average percentile values for maximal aerobic capacity in the groups were YA 80–90%, YI 10–20%, OA 80–90%, and OI 20–30%. On average, among groups there was a separation of well above average to below average maximal aerobic capacity between the groups supports that the activity questionnaire and verbal screening were effective tools to help recruit two distinct activity status groupings.

Several of the design features of this experiment could be viewed as strengths or weaknesses. The appetite and mood state analyses were obtained as a secondary objective from a study evaluating the effects of physical activity and age on inflammatory biomarkers. Power calculations to determine sample size were not performed specifically for appetite and mood state assessments and these results should be confirmed with future studies with larger samples sizes. Subjects were recruited with body mass indices including normal weight, overweight, and obese class I. However, on average subjects were within normal and overweight categories, and only 4.2 kg/m2 separated the highest group (OI) from the lowest group (YA). Furthermore, a previous comparison of appetite response between lean and obese individuals resulted in no differences (Mourao et al. 2007). Also, males and females were evaluated to broaden the application of the findings; however sex may alter appetitive response (Carels et al. 2007; Gayle et al. 2006). A study examining the effects of sex on appetitive response found differences in energy intake but no difference to hunger and fullness rating (Davy et al. 2007). Sex differences were not statistically assessed because the study was designed to examine the effects of physical activity status and age on appetite. Appetitive sensations cannot be directly correlated to energy intake; although it has been documented as hunger increases to peak levels a meal is requested (Cummings et al. 2004; Parker et al. 2004) and is a useful tool to determine overall energy intake (Drapeau et al. 2005). Each subject’s natural patterns of hunger and fullness were allowed to develop, without supervision, since their sleep schedule, diet, and energy consumption were not restricted and occurred outside the laboratory setting. The decision to assess appetite and mood state on a day when none of the subjects performed exercise eliminated ‘exercise induced anorexia’ (Blundell et al. 2003), duration of physical activity (Stubbs et al. 2002), and the hour of day (Maraki et al. 2005) which physical activity occurs as potential confounding effectors. The conclusions of this study are limited to appetitive and mood state responses on a non-physically active day.

In humans, the age related declines in appetite and food intake that characterize aging are generally considered to include increased fullness and (or) decreased hunger in elderly persons (Apolzan et al. 2007; Morley 1997). However, increased feelings of fullness were not observed in the current study. Lower levels of hunger and desire to eat were found in the older subjects which could be due to the non-physiologic reasons of the ‘anorexia of aging’ including social, psychological, and medical factors (MacIntosh et al. 2000). The food records showed age-related declines in food intake although not significant, a finding documented by others (Vellas et al. 1997).

Physical activity can positively affect mood state (Doyne et al. 1987; Martinsen et al. 1989; Stewart et al. 2003) by improving psychological well-being (Doyne et al. 1987; Martinsen et al. 1989) and alleviating depression in elderly persons (McNeil et al. 1991). However, psychological well-being was not directly assessed in the current study by the mood state grid, but based on previous research (Doyne et al. 1987; Martinsen et al. 1989), it is likely the physically active groups had a higher well-being. Higher vitality in active individuals was documented previously (Kerse et al. 2005; Stewart et al. 2003) and the higher nadir arousal (less maximal sleepiness) observed in the current study is consistent with those findings. Older persons have greater mood stability (Lawton et al. 1992) which may have prevented a decrease in mean and nadir pleasantness. In the current study, nadir arousal had significant responses to age and activity status. Figure 2A illustrates nadir arousal for the older active group was nearly double the younger inactive group, and a stepwise progression was observed. The nadir arousal response was age and activity independent and additive i.e. there were no interactions but there was a pronounced synergism when combined. In the current study, weak correlations existed between appetite and mood state. Forty-one percent of individuals had nadir hunger and nadir pleasantness concurrently, while 45% had nadir desire to eat and nadir pleasantness at the same time. Seventy-three percent and 79% of participants’ nadir pleasantness is accounted for when the hours before and after nadir hunger and desire to eat were included, respectively. It may be possible that an unpleasant attitude lowers all subsequent appetite and mood ratings. However, of greater likelihood, the lowest levels of hunger and desire to eat during the day may contribute to individuals becoming the most unpleasant. Thus, avoidance of extreme hunger and desire to eat may help a person not be as unpleasant at any point during the course of the day.

Conclusion

The results suggest chronic physical activity status does not influence appetite in younger and older humans. On a non-exercising day, physical activity did not influence the age-associated declines in appetitive response but increased nadir arousal on a non-exercising day. Thus, aerobic physical activity alone may not prevent the onset of the ‘anorexia of aging’ in older adults but may help physical well-being by heightening nadir arousal. Further research should be performed analyzing the possible beneficial effects of resistance training on appetitive response and exercise and nutritional supplementation in healthy, older individuals. These investigations with their potential mechanisms need to be explored to help combat the age related declines in appetite and food intake that lead to weight loss and frailty.

Acknowledgments

Funding was from a NIH R03AG2285 and Phyllis Izant gift funds. JWA was supported by a Purdue University Lynn Fellowship and unrestricted funds from Experimental and Applied Sciences, Inc.

Footnotes

The authors had no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

John W. Apolzan, Email: apolzan@purdue.edu.

Michael G. Flynn, Email: mickflyn@purdue.edu.

Brian K. McFarlin, Email: bmcfarlin@mail.coe.uh.edu.

Wayne W. Campbell, Email: campbellw@purdue.edu.

References

- Apolzan JW, Carnell NS, Mattes RD, Campbell WW. Inadequate dietary protein increases hunger and desire to eat in younger and older men. J Nutr. 2007;137(6):1478–1482. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.6.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellisle F. Food choice, appetite and physical activity. Public Health Nutr. 1999;2(3A):357–361. doi: 10.1017/s1368980099000488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black AE. Critical evaluation of energy intake using the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake:basal metabolic rate. A practical guide to its calculation, use and limitations. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(9):1119–1130. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell JE, King NA. Physical activity and regulation of food intake: current evidence. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(11 Suppl):S573–583. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell JE, Stubbs RJ, Hughes DA, Whybrow S, King NA. Cross talk between physical activity and appetite control: does physical activity stimulate appetite? Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62(3):651–661. doi: 10.1079/PNS2003286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carels RA, Konrad K, Harper J. Individual differences in food perceptions and calorie estimation: an examination of dieting status, weight, and gender. Appetite. 2007;49(2):450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman IM, MacIntosh CG, Morley JE, Horowitz M. The anorexia of ageing. Biogerontology. 2002;3(1–2):67–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1015211530695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DE, Frayo RS, Marmonier C, Aubert R, Chapelot D. Plasma ghrelin levels and hunger scores in humans initiating meals voluntarily without time- and food-related cues. American journal of physiology. 2004;287(2):E297–304. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00582.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davy BM, Van Walleghen EL, Orr JS. Sex differences in acute energy intake regulation. Appetite. 2007;49(1):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong N, Chin A, Paw MJ, de Graaf C, van Staveren WA. Effect of dietary supplements and physical exercise on sensory perception, appetite, dietary intake and body weight in frail elderly subjects. Br J Nutr. 2000;83(6):605–613. doi: 10.1017/s0007114500000775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMeglio DP, Mattes RD. Liquid versus solid carbohydrate: effects on food intake and body weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(6):794–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyne EJ, Ossip-Klein DJ, Bowman ED, Osborn KM, McDougall-Wilson IB, Neimeyer RA. Running versus weight lifting in the treatment of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55(5):748–754. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau V, Blundell J, Therrien F, Lawton C, Richard D, Tremblay A. Appetite sensations as a marker of overall intake. Br J Nutr. 2005;93(2):273–280. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant ML, Royston JP, Wloch RT. Effect of exercise on energy intake and eating patterns in lean and obese humans. Physiol Behav. 1982;29(3):449–454. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(82)90265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiatarone MA, O’Neill EF, Ryan ND, Clements KM, Solares GR, Nelson ME, et al. Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. N Engl J Med. 330(25):1769–1775. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406233302501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin B, editor. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 6. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gayle DA, Desai M, Casillas E, Beloosesky R, Ross MG. Gender-specific orexigenic and anorexigenic mechanisms in rats. Life sciences. 2006;79(16):1531–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays NP, Roberts SB. The anorexia of aging in humans. Physiol Behav. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtkooper LB, Lohman TG, Going SB, Howell WH. Why bioelectrical impedance analysis should be used for estimating adiposity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(3 Suppl):436S–448S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.3.436S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TT, Roberts SB, Howarth NC, McCrory MA. Effect of screening out implausible energy intake reports on relationships between diet and BMI. Obes Res. 2005;13(7):1205–1217. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert P, King NA, Blundell JE. Uncoupling the effects of energy expenditure and energy intake: appetite response to short-term energy deficit induced by meal omission and physical activity. Appetite. 1998;31(1):9–19. doi: 10.1006/appe.1997.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz IR, Beaston-Wimmer P, Parmelee P, Friedman E, Lawton MP. Failure to thrive in the elderly: exploration of the concept and delineation of psychiatric components. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology. 1993;6(3):161–169. doi: 10.1177/089198879300600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerse N, Elley CR, Robinson E, Arroll B. Is physical activity counseling effective for older people? A cluster randomized, controlled trial in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):1951–1956. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NA. What processes are involved in the appetite response to moderate increases in exercise-induced energy expenditure? Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58(1):107–113. doi: 10.1079/pns19990015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NA, Tremblay A, Blundell JE. Effects of exercise on appetite control: implications for energy balance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(8):1076–1089. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199708000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Kleban MH, Rajagopal D, Dean J. Dimensions of affective experience in three age groups. Psychol Aging. 1992;7(2):171–184. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SJ, Hart K, Morgan LM. The ability of habitual exercise to influence appetite and food intake in response to high- and low-energy preloads in man. Br J Nutr. 2002;87(5):517–523. doi: 10.1079/BJNBJN2002560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntosh C, Morley JE, Chapman IM. The anorexia of aging. Nutrition. 2000;16(10):983–995. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraki M, Tsofliou F, Pitsiladis YP, Malkova D, Mutrie N, Higgins S. Acute effects of a single exercise class on appetite, energy intake and mood. Is there a time of day effect? Appetite. 2005;45(3):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen EW, Hoffart A, Solberg O. Comparing aerobic with nonaerobic forms of exercise in the treatment of clinical depression: a randomized trial. Compr Psychiatry. 1989;30(4):324–331. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(89)90057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlin BK, Flynn MG, Campbell WW, Craig BA, Robinson JP, Stewart LK, et al. Physical activity status, but not age, influences inflammatory biomarkers and toll-like receptor 4. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(4):388–393. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil JK, LeBlanc EM, Joyner M. The effect of exercise on depressive symptoms in the moderately depressed elderly. Psychol Aging. 1991;6(3):487–488. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE. Anorexia of aging: physiologic and pathologic. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(4):760–773. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.4.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourao DM, Bressan J, Campbell WW, Mattes RD. Effects of food form on appetite and energy intake in lean and obese young adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(11):1688–1695. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker BA, Ludher AK, Loon TK, Horowitz M, Chapman IM. Relationships of ratings of appetite to food intake in healthy older men and women. Appetite. 2004;43(3):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira MA, FitzerGerald SJ, Gregg EW, Joswiak ML, Ryan WJ, Suminski RR, et al. A collection of Physical Activity Questionnaires for health-related research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(6 Suppl):S1–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers PJ, Blundell JE. Effect of anorexic drugs on food intake and the microstructure of eating in human subjects. Psychopharmacology. 1979;66(2):159–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00427624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J, Weiss A, Mendelsohn G. Affect Grid: A Single-Item Scale of Pleasure and Arousal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(3):493–502. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Frederick C. On energy, personality, and health: subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of personality. 1997;65(3):529–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield WN. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Human nutrition. 1985;39(Suppl 1):5–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart KJ, Turner KL, Bacher AC, DeRegis JR, Sung J, Tayback M, et al. Are fitness, activity, and fatness associated with health-related quality of life and mood in older persons? J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23(2):115–121. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs RJ, Sepp A, Hughes DA, Johnstone AM, Horgan GW, King N, et al. The effect of graded levels of exercise on energy intake and balance in free-living men, consuming their normal diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(2):129–140. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DA, Wolfe LA, Eikelboom R. Acute effects of exercise intensity on appetite in young men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20(3):222–227. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198806000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Morris LK. Unexplained weight loss in the ambulatory elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(5):497–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellas BJ, Hunt WC, Romero LJ, Koehler KM, Baumgartner RN, Garry PJ. Changes in nutritional status and patterns of morbidity among free-living elderly persons: a 10-year longitudinal study. Nutrition. 1997;13(6):515–519. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuillemin A, Boini S, Bertrais S, Tessier S, Oppert JM, Hercberg S, et al. Leisure time physical activity and health-related quality of life. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel-Vos GC, Schuit AJ, Tijhuis MA, Kromhout D. Leisure time physical activity and health-related quality of life: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(3):667–677. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021313.51397.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MM, Morley JE. Invited review: Aging and energy balance. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95(4):1728–1736. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00313.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]