Abstract

The ILSXISS (LXS) recombinant inbred (RI) panel of mice is a valuable resource for genetic mapping studies of complex traits, due to its genetic diversity and large number of strains. Male and female mice from this panel were used to investigate genetic influences on alcohol consumption in the “drinking in the dark” (DID) model. Male mice (38 strains) and female mice (36 strains) were given access to 20% ethanol during the early phase of their circadian dark cycle for four consecutive days. The first principal component of alcohol consumption measures on days 2, 3 and 4 was used as a phenotype (DID phenotype) to calculate QTLs, using a SNP marker set for the LXS RI panel. Five QTLs were identified, three of which included a significant genotype by sex interaction, i.e., a significant genotype effect in males and not females. To investigate candidate genes associated with the DID phenotype, data from brain microarray analysis (Affymetrix Mouse Exon 1.0 ST Arrays) of male LXS RI strains were combined with RNA-Seq data (mouse brain transcriptome reconstruction) from the parental ILS and ISS strains in order to identify expressed mouse brain transcripts. Candidate genes were determined based on common eQTL and DID phenotype QTL regions and correlation of transcript expression levels with the DID phenotype. The resulting candidate genes (in particular, Arntl/Bmal1) focused attention on the influence of circadian regulation on the variation in the DID phenotype in this population of mice.

Introduction

Recombinant inbred (RI) panels of mice and rats provide a valuable resource for genetic mapping (Philip et al. 2010; Williams et al. 2004). The ILSXISS (LXS) recombinant inbred mouse panel was created through reciprocal crosses of the Inbred Long-Sleep (ILS) and Inbred Short-Sleep (ISS) mice. The ILS and ISS mice were derived from LS and SS mice, which were selectively bred for differences in sensitivity to the sedative-hypnotic effect of ethanol, starting from an 8-way cross heterogeneous stock (HS/Ibg) (McClearn and Kakihana 1981). Therefore, mice in this RI panel have considerable genetic diversity, compared to other mouse RI panels. As described previously, the LXS RI panel segregates for traits other than sensitivity to alcohol, and, because it consists of a relatively large number of strains, it is a powerful resource for mapping complex traits (Williams et al. 2004).

“Drinking in the dark” (DID) is a method used to produce alcohol drinking to intoxication (Ryabinin et al. 2003). In this model, rodents are given access to alcohol during the first 2–4 hours of their circadian dark period, and “alcohol-preferring” strains of mice, such as C57BL/6, consume an amount of alcohol during this time that produces blood ethanol levels that are comparable to the levels that define “binge” drinking in humans (Rhodes et al. 2005; 2007; Thiele and Navarro 2014).

The DID phenotype is genetically influenced, since studies with inbred mouse strains have indicated similar DID alcohol consumption within strains and different levels of DID alcohol consumption across strains (Rhodes et al. 2007). Furthermore, successful selective breeding for high blood ethanol levels achieved during DID has been accomplished, leading to replicate selected HDID1 and HDID2 mouse lines (Crabbe et al. 2009). In these animals, the blood ethanol concentration correlates with the amount of alcohol consumed in the DID protocol.

Although there is a genetic influence on DID, only a few studies have investigated QTLs or genes associated with this phenotype (Crabbe et al. 2010; Iancu et al. 2013). In the current work, we undertook a QTL analysis of DID in the LXS mouse panel, including a comparison of male and female mice. The results show an interaction of sex with genotype for certain QTLs associated with DID, and provide insight into genetic mechanisms that may contribute to DID alcohol consumption. In particular, the candidate genes identified for a predisposition to variation in DID alcohol consumption in male mice are suggestive of a circadian component to the regulation of this phenotype.

Materials and methods

Animals and Alcohol Consumption (Drinking in the Dark, DID)

Animal breeding and behavioral testing were conducted in the specific pathogen-free facility at the Institute for Behavioral Genetics, Boulder, CO. One week prior to testing, male mice (38 strains, n=2–15 per strain) and female mice (36 strains, n=3–14 per strain) (31 strains in common between males and females) were individually housed in a room set on a reverse light:dark cycle. For detailed information on the number of mice in each specific mouse strain, see Table S1. The mice were between 51 and 153 days old. After one week of acclimatization, mice were weighed one hour prior to lights out (lights out at 0830), on each of four consecutive test days (Rhodes et al. 2005). Four hours after lights out (1230), water bottles were replaced with 10 mL drinking tubes containing 20% ethanol (v/v in tap water). Two hours after introduction of the alcohol-containing drinking tubes (1430), the tubes were removed, the fluid levels were recorded, and, on days 1–3, the tubes were replaced with water bottles. On day 4, alcohol intake was determined for a second time at 1630, and tubes were then replaced with water bottles; however, in order to be consistent, only consumption data from the first two hours on day 4 were used in our analysis.

All procedures followed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the University of Colorado, Boulder, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Procedures for RNA isolation (see below) also followed the NIH Guide, and were approved by the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus IACUC.

Genotypes

A genetic marker set (specifically SNPs) for the LXS RI panel (66 RI strains) was generated by Dr. Gary Churchill and colleagues at The Jackson Laboratory using the Affymetrix Mouse Diversity Genotyping Array. In total, 314,865 probesets were on the array. Of these, 303,988 SNPs/probesets had a unique dbSNP identifier. Markers that did not differ between the parental strains (ILS and ISS), markers containing a heterozygous genotype call in either or both parental strains and markers for which more than 5% of the RI strains had a missing or heterozygous call were deleted, resulting in 43,997 markers. Markers without valid positions in the GRCm38/mm10 assembly of the mouse genome and markers with large genetic distances compared to physical distance (improbable recombination rates) were deleted, resulting in 43,870 markers. This dataset is available on Phenogen (http://phenogen.ucdenver.edu) for QTL calculations.

We further examined genotype calls in individual strains. If a strain had an “unknown” call for a specific marker, a call was assigned to the marker if the marker was within an LXS panel haplotype block and could be unambiguously imputed (4,046 unknown calls changed). Two strains (LXS10 and LXS68) were removed from the marker set due to having more than 5% of markers with unknown calls. SNPs with a genotype call that implied a double recombination event when compared to the two adjacent SNPs were assumed to be genotyping errors and the entire SNP was removed from further analyses (58 SNPs deleted).

Because of the original density of the SNP marker set and our ability to impute some missing genotype information, we were able to limit our association analysis with the DID phenotype to SNPs for which there was no missing genotype information among the RI strains for which we collected DID data (43 RI strains). Many of these adjacent SNPs display the same genotype pattern among all the RI strains (i.e., no recombination events for any strain between SNPs), which would result in the same level of statistical significance (i.e., p-value) for all of these SNPs when performing QTL analysis. Therefore, we reduced the number of association tests, without losing information, by identifying 1,093 unique strain distribution patterns (SDPs; i.e., the genotypes for all strains at a particular SNP) among these 39,045 SNPs. This marker set density provided good coverage of the LXS genome (Tables S2 and S3).

DID Phenotype QTL Analysis

The DID data were initially cleaned to remove outliers (more than 2.5 standard deviations from the within-strain and sex mean) for each of the 3 DID measurements, i.e., alcohol intake (g/kg) on day 2 (when intake had stabilized); day 3; and the first two hours of day 4. All 3 DID alcohol consumption measurements showed heteroscedasticity across strains in both males and females. The DID phenotypes were therefore transformed by taking the natural log of the original DID value plus 1 (to force all values to be non-zero prior to the transformation), resulting in homogeneous variances. Instead of performing separate QTL analyses on 3 similar DID phenotypes, principal component analysis (PCA) was used to summarize the three, log-transformed, DID phenotypes into one quantitative measurement (first principal component).

Although age varied among the mice used in this study, age did not vary dramatically within strain. Age is both a potential confounder and a potential modifier of the effects of genetics on DID. To determine if age was a confounder in this study, and therefore needed to be included in our QTL analysis, we statistically evaluated the association between age and strain and the association between age and the DID phenotype. We also evaluated age as a potential modifier of the effect of genetics on DID using a linear regression model that included strain, sex, age, and all possible 2-way interactions.

To examine the effect of individual markers on DID, a full mixed model was performed with each marker, which consisted of the genotype (annotated either “L” from the ILS parent or “S” from the ISS parent), sex, age and all potential 2-way interactions in predicting the DID phenotype. Strain was included as a random effect. To determine the significance of the association of DID with the genotype, regardless of whether the genotype effect was dependent or independent of age and sex, a likelihood ratio test (LRT) was performed comparing the full model to a reduced model that only included sex, age and their interactions with each other in predicting the DID phenotype. Candidate markers are those with a nominal p-value < 0.001.

Given the large number of interaction effects tested in the full model, candidate markers that have a moderate effect that is independent of sex and age could potentially be missed. In addition to the full model, we therefore also ran a “basic” mixed model using the same method described above, but without any interaction effects. Candidate markers are those with nominal p-value < 0.001.

The likelihood ratio test is an omnibus test to determine any association of genotype with DID. To describe the dependence of the genotype effect on age and sex, a backward elimination technique was used (alpha level = 0.1) to obtain the most parsimonious model for each candidate marker, by eliminating non-significant covariates and interaction effects. The effect sizes and significance of the remaining effects are reported.

RNA Expression – High Throughput Sequencing

To gather qualitative brain transcriptome information relevant to the LXS RI panel, mice were sacrificed in the morning (9am-12pm), and total RNA was isolated from whole brains of naïve (non-alcohol-exposed) mice from the two progenitor strains (ILS and ISS; 3 mice per strain) using the RNeasy Midi Kit with additional clean-up using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Quality of extracted total RNA was assessed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Ribosomal RNA was depleted from total RNA using the Ribo-Zero Magnetic Kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Sequencing libraries were constructed using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Library quality was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer. The samples were barcoded and pooled, and all six samples were included in each of three lanes of a flowcell. Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (100 base pair paired-end reads).

Prior to alignment, reads were de-multiplexed and trimmed of adaptors and low quality base calls using trim_galore (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). Entire reads were eliminated if either read fragment was less than 20 bp after trimming. Reads were aligned to the mm10 version of the mouse genome using tophat2 (Kim et al. 2013) with default settings for stranded reads.

The brain transcriptomes for the ILS and ISS strains were reconstructed separately using all aligned reads from each strain. Cufflinks was used to reconstruct the brain transcriptome using both a genome guide and a transcriptome guide (Trapnell et al. 2010). The transcriptome used for guidance was the RefSeq mm10 version (Dec 2011) downloaded from the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Site (http://genome.ucsc.edu). The two strain-specific transcriptomes were manually combined into a single transcriptome of high confidence transcripts. First, each strain-specific transcriptome was reduced to transcripts with an FPKM value greater than 1 (as calculated in the CuffLinks software) and a length greater than 300 bp (not including introns). Novel, i.e., unannotated, transcripts identified in the strain-specific transcriptomes were combined. Novel transcripts “matched” between strain-specific transcriptomes if: 1) all exon start and stop positions matched, 2) all exon junctions matched, or 3) both transcripts contained only one exon and both their transcription start sites were within 100 bp of each other, and their transcription stop sites were within 100 bp of each other. Two transcripts were identified as being from the same gene if: 1) their transcription start sites matched exactly, 2) their transcription stop sites matched exactly, or 3) at least one exon junction matched exactly. This combined transcriptome was pruned further by quantifying the transcript expression levels of the combined transcriptome in either strain using Sailfish (Patro et al. 2014). Transcripts were retained if at least one of the six samples had a TPM (transcripts per million reads) value greater than 1. After elimination of low expressing transcripts, TPM values were calculated again. This iteration between quantification and elimination of transcripts continued until less than 1% of transcripts had a TPM value less than 1.

RNA Expression – Microarray Analysis

The gene expression dataset was derived from whole brain of naïve (non-alcohol-exposed) 10-week-old male mice (n=4–6 per strain) from 60 LXS RI strains (http://phenogen.ucdenver.edu). Expression analysis was performed with Affymetrix mouse whole genome exon arrays (Mouse Exon 1.0 ST, Affymetrix, Santa Clara CA) as previously described (Tabakoff et al. 2008; Vanderlinden et al. 2013) and according to the manufacturer’s protocols. RNA from the brain of each mouse was hybridized to a separate array.

Information gathered from high throughput DNA sequencing of the ILS and ISS strains (Dr. Richard Radcliffe, Skaggs School of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Colorado, personal communication) and the brain transcriptome generated from the ILS and ISS strains was used to guide the use of probes/probesets from the Affymetrix Mouse Exon Array 1.0 ST for quantifying transcript expression in the LXS RI panel. First, individual probes were masked if they did not align uniquely to the mouse genome (mm10) or if they aligned to a region that harbored a SNP between the reference genome (based on the C57BL/6 inbred mouse strain) and either of the ILS or ISS strains. Entire probesets were eliminated if less than 3 probes remained after masking. The generated mask from the Affymetrix Mouse Exon 1.0 ST Array is available at http://phenogen.ucdenver.edu. The remaining probesets were compared to the brain transcriptome derived from the RNA-Seq data. Expression values for probesets that were completely contained within a transcript, not including intronic regions, were estimated using RMA (Shakya et al. 2010). Probesets that were expressed above background (detection above background p-value < 0.0001) in more than 50% of the RI samples were identified and correlations across strains among expressed probesets targeted to the same gene were calculated. Probesets were placed into transcript clusters based on the correlation (hierarchical clustering using 1 minus the correlation coefficient as a distance measure) among probesets targeted to the same gene. Each transcript cluster potentially represents a different splice variant, i.e., transcript, of that gene. When two or more probesets were correlated (correlation coefficient > 0.25), the first principal component was used as a summary measure for that transcript cluster in further analyses. Heritability of each transcript cluster was assessed using the coefficient of determination (r2) from a one-way ANOVA, and clusters with low heritability (r2 < 0.33) were not included in further analyses.

Hierarchical clustering with distances measured as one minus the correlation coefficient was used to identify potential outliers among the array data. Data from individual arrays were removed if they did not cluster with the data from other arrays (distance greater than 0.0025). Of the 341 arrays, 3 were defined as outliers and removed from the analysis.

Expression QTL (eQTL) Analysis

Expression QTLs (eQTLs) were identified using marker regression, the LXS RI SNP marker dataset described earlier, and the transcript expression strain means as the quantitative trait. Only SNPs with no missing genotype data among the RI strains for which expression data were collected were used (36,749 SNPs; 1,414 unique SDPs).

Candidate Transcripts

Candidate transcripts associated with a predisposition to the DID phenotype were identified as described previously (Tabakoff et al. 2008; Tabakoff et al. 2009), based on the assumptions that if the expression level of a transcript contributes to the phenotype, then 1) the region of the genome that regulates the phenotype (DID phenotype QTL) should be the same as the region of the genome that regulates the transcript’s expression levels (eQTL) and 2) the expression level of the transcript should be correlated with the quantitative phenotype across the RI strains. To implement this process, significant eQTLs (genome-wide p-value<0.05) were identified, and the overlap of eQTLs with DID phenotype QTL regions (i.e., eQTL lies within a DID phenotype QTL region) was determined. A Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated between the expression level of each transcript cluster which had an eQTL with these characteristics, and the male DID phenotype. Candidate transcripts were derived from transcript clusters that significantly correlated with DID (nominal p-value < 0.001). To control for multiple comparisons, a false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Since the expression data were only available for male mice, the correlation was only performed using male DID phenotype data.

Results

Alcohol Consumption

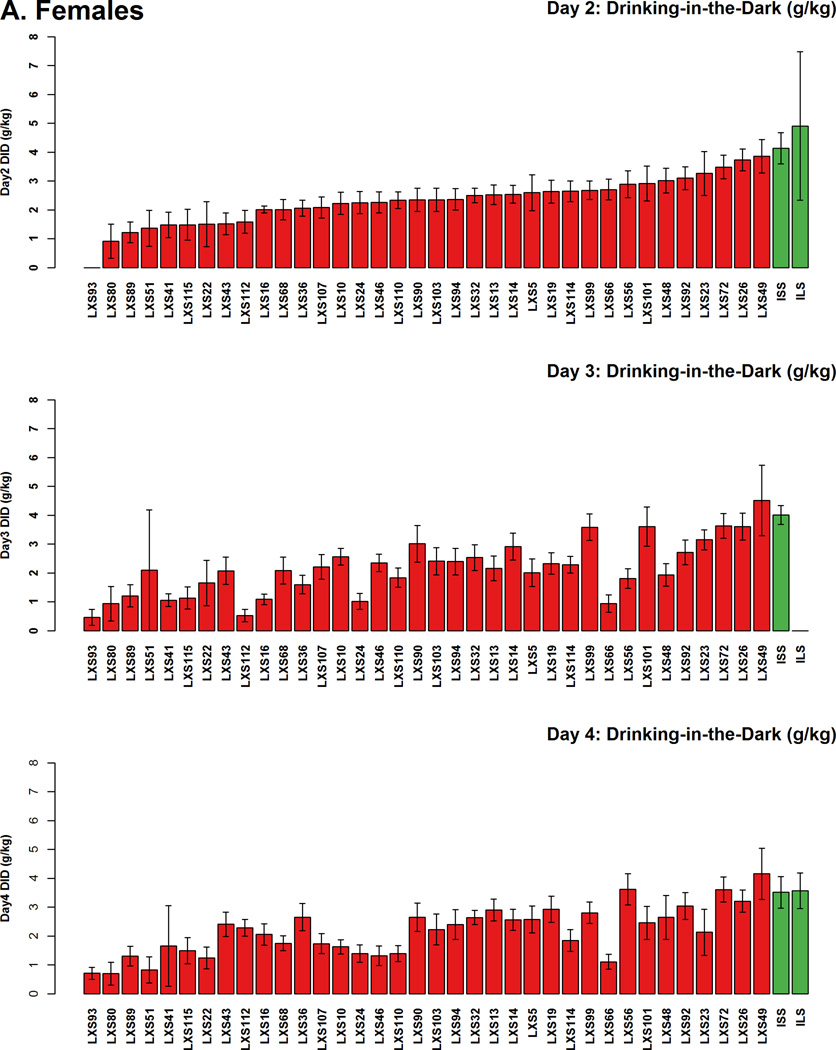

Data for six mice were removed from the analysis of the DID data due to outlying values for one of the 3 time points. DID values for each day (strain mean ± 1 standard error) are plotted in Figure 1, in order of ascending DID from day 2. These results demonstrate a significant amount of transgressive segregation (Rieseberg et al. 1999), i.e., the alcohol consumption by most of the RI strains is less than that by either of the parental strains. Measurements of consumption across the three different days were significantly (p<0.0001) but not perfectly correlated in both males and females (correlation coefficients ranging from 0.67 to 0.88). The first principal component obtained from PCA of log-transformed DID values explained 62.8% and 66.3% of the variance in females and males, respectively. The loadings for the 3 DID measurements were similar in magnitude and direction for the first principal component, i.e., 0.58, 0.59, and 0.56 for females and 0.55, 0.61, and 0.57 for males (corresponding to days 2, 3, and 4 respectively) (Figure S1, Table S4). Broad-sense heritability (H2) of this summary DID phenotype was calculated for each sex separately using a 1-way ANOVA. The heritability for the DID phenotype was 42.6% and 48.2% in females and males, respectively.

Figure 1. Distribution of Drinking in the Dark (DID) Alcohol Consumption Values Across the LXS RI panel.

The DID strain means are plotted individually for (A) females (red with progenitor strains green), and (B) males (blue, with progenitor strains yellow). Error bars represent ±1 SEM. The strains are ordered by ascending DID values from day 2 in all of the plots. Female LXS93 on day 2 and male LXS28 on day 3 did not drink any alcohol. Female ILS data from day 3 were not available.

DID Phenotype QTLs

The investigation of age in the male population indicated that age was a potential confounder of the genetic effect on the DID phenotype because age was associated with both strain (p <0.0001; 1-way ANOVA) and DID (p = 0.026; linear regression). In females, age was associated with strain (p<0.0001) but not with DID (p = 0.20). Age was included in all QTL models to address the problem of confounding in the male population. Also, the age by strain interaction effect in the QTL model was significant (p = 0.019). Therefore, an age by genotype interaction effect was included in the full model QTL analysis.

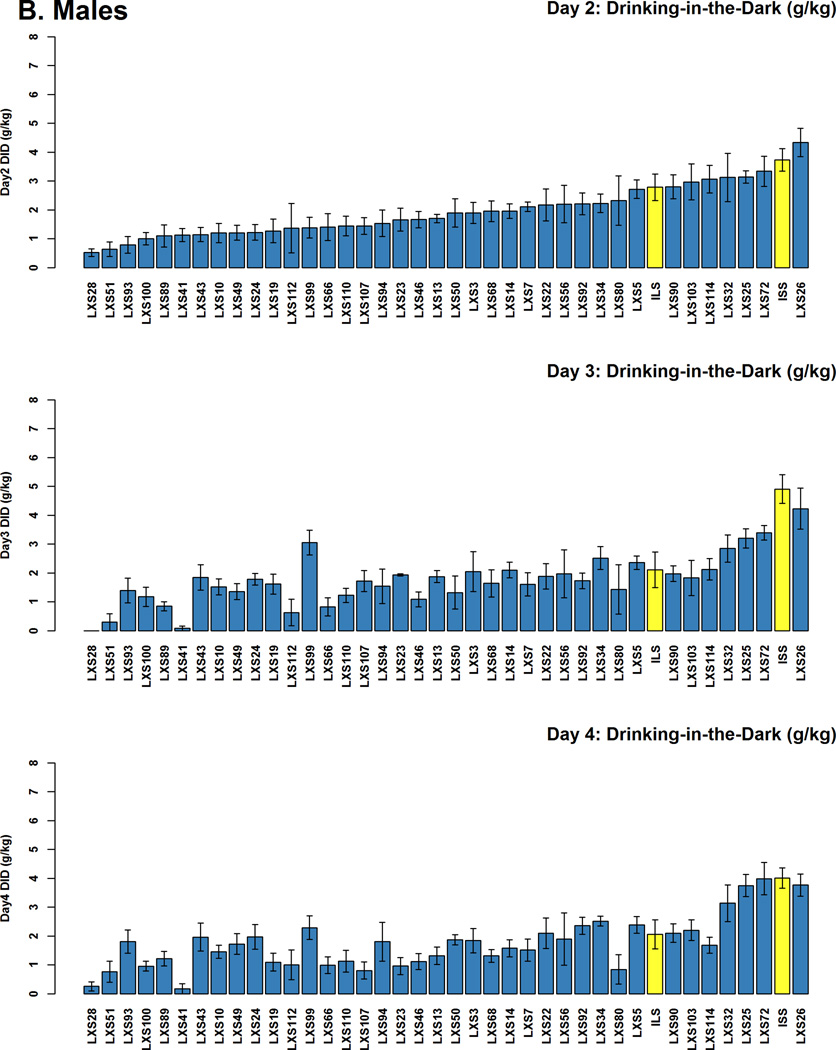

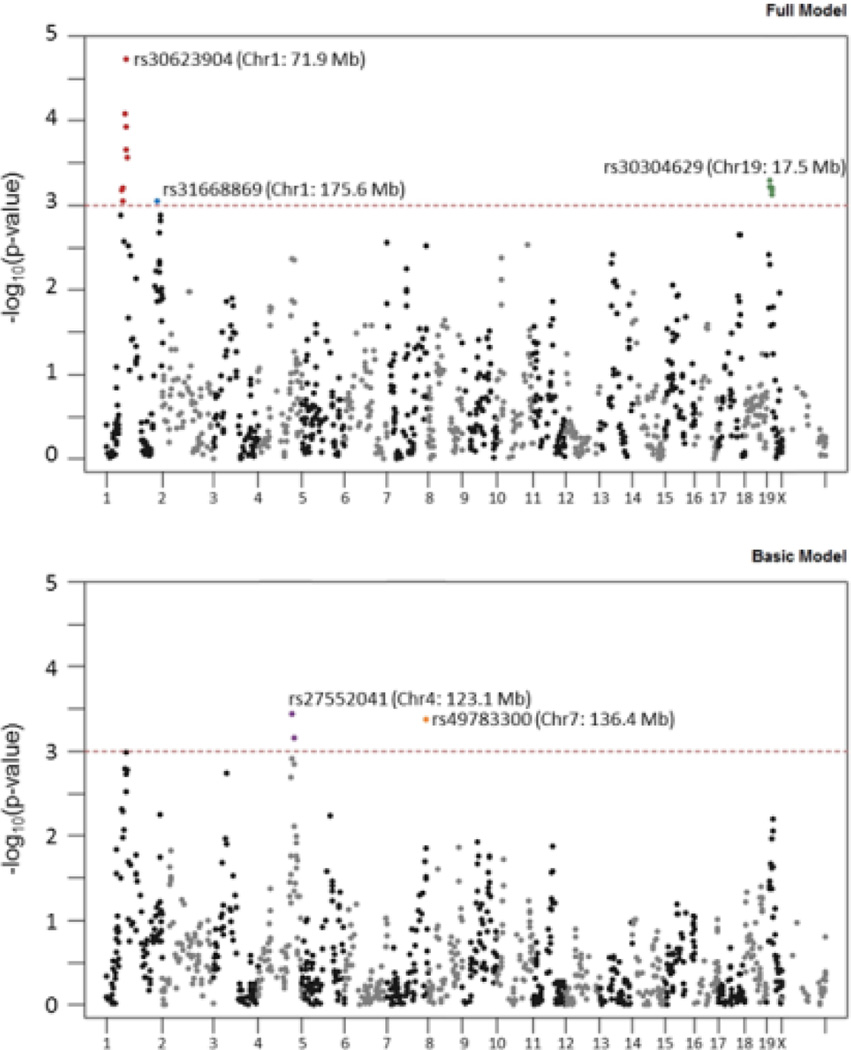

Figure 2 shows Manhattan plots for the likelihood ratio test (LRT) p-values from the full model (Figure 2A) and the basic model (i.e., no interaction effects) (Figure 2B). The full model identified sixteen total candidate markers; nine markers were located on chromosome 1 (two separate positions), and seven markers were located on chromosome 19. The basic model identified three additional candidate markers: one marker located on chromosome 7 and the other two markers located on chromosome 4. Table 1 shows the main effects and interaction effects in the final models. The QTLs from the full model include a significant genotype by sex interaction effect, which is not evident in the QTLs from the basic model. Of all the 2-way interactions, only sex by genotype was significant in any of the QTL models. The sex by genotype interaction effects associated with the three genomic regions on chromosomes 1 and 19 are illustrated in Figure 3. For all three of these QTLs, there is a significant genotype effect on DID in males and no significant effect in females. For the QTLs on chromosomes 4 and 7, the genotype effect is independent of sex. The percent of genetic variance in the phenotype explained by each QTL (determined by ANOVA), and the total proportion of genetic variance explained when all QTLs are included in the model (determined by a multi-factor ANOVA), are shown in Table 2. Because all five QTLs indicate a genetic effect in males and only two of the five indicate a genetic effect in females, the proportion of genetic variance explained by the combination of all QTLs is greater for males than for females.

Figure 2. Manhattan Plot for the QTL Analysis.

The –log10(p-value) from the LRT determining the association between genotype and DID phenotype is plotted. The colored (red, blue, green, purple, orange) dots represent significantly associated SNPs (nominal p-value <0.001). Adjacent associated SNPs that represent a single QTL region are the same color. The dbSNP identifier and physical location are reported for the marker with the minimum p-value in each QTL region. A. Results from the full model. B. Results from the basic model.

Table 1. DID Phenotype QTLs.

QTL results are shown for the full and basic model likelihood ratio tests.

| Method Found to Have Significant LRT |

SNP*: Chr (Mb) |

80% Bayesian Credible Interval for QTL |

LRT p-value |

Genotype p-value |

Sex p-value |

Genotype by Sex Interaction p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Model | rs30623904 Chr1 (71.9 Mb) |

Chr1 (38.2 – 77.0) | <0.0001 | NA | NA | 0.0001 |

| Full Model | rs31668869 Chr1 (175.6 Mb) |

Chr1 (66.6 – 194.7) | 0.0009 | NA | NA | 0.0003 |

| Full Model | rs30304629 Chr19 (17.5 Mb) |

Chr19 (0.0 – 27.5) | 0.0007 | NA | NA | 0.0019 |

| Basic Model | rs27552041 Chr4 (123.1 Mb) |

Chr4 (95.9 – 129.0) | 0.0004 | 0.0001 | --- | --- |

| Basic Model | rs49783300 Chr7 (136.4 Mb) |

Chr7 (67.1 – 139.0) | 0.0004 | 0.0001 | --- | --- |

NA: not applicable due to a higher order interaction effect between genotype and sex. ---: no p-value available because the factor was removed from final model in the backward elimination process.

The dbSNP ID and position of the SNP with the lowest p-value in that region.

Figure 3. Effect Sizes of DID Phenotype.

The mean DID phenotype ± 1 SEM for each sex and genotype combination is plotted. The females are in red and the males in blue. Genotype “L” represents the genotype for the ILS strain and genotype “S” represents the genotype for the ISS strain. * P<0.05 between L and S within a sex (contrast from the mixed model).

Table 2. Proportion of Genetic Variance Explained.

The proportion of genetic variance explained by each DID phenotype QTL, as well as the combination of all QTLs listed in the table, is shown.

|

Max LOD SNP: Chr (Mb) |

Females: % Genetic Variance Explained |

Males: % Genetic Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|

|

rs30623904 Chr1 (71.9 Mb) |

3.50% | 34.6%*† |

|

rs31668869 Chr1 (175.6 Mb) |

0.20% | 21.0%* |

|

rs30304629 Chr19 (17.5 Mb) |

0.10% | 22.8%*† |

|

rs27552041 Chr4 (123.1 Mb) |

18.6%* | 19.7%* |

|

rs49783300 Chr7 (136.4 Mb) |

26.6%*† | 16.1%*† |

| ALL QTLs | 31.3%* | 60.5%* |

P<0.05, compared to no variance explained (ANOVA).

QTLs which were significant in the multi-factor model (p-value > 0.05).

Although age was identified as a potential modifier of the genetic effect on DID, none of the QTLs identified had a significant genotype by age or sex by age interaction in their final model.

RNA Sequencing and Identification of Transcript Clusters

The process used to annotate the brain transcriptome of the progenitor strains of the LXS panel (ILS and ISS) began with nearly 450 million paired-end reads (900 million read fragments) from six samples (3 from each strain). Approximately 700 million (78%) read fragments aligned to the mm10 version of the mouse genome, including 19 autosomal chromosomes and 2 sex chromosomes. 76,899 transcripts (68,227 genes) were identified as high confidence (FPKM>1 in at least one strain, >300 nt in length, and TPM >1 in at least one sample) and thus were included in the reconstructed ILS/ISS brain transcriptome.

Of the 4.8 million probes on the Affymetrix Mouse Exon 1.0 ST Array, 3.9 million (81%) aligned uniquely to the mm10 version of the mouse genome and aligned to a region of the genome that did not harbor a SNP or small indel identified in the genome of the ILS or ISS strains when compared to the reference strain (C57BL/6), on which sequences for the Affymetrix probes are based. These “high integrity” probes were summarized into 1 million probesets (3–4 probes/probeset), based on Affymetrix annotation, and 160,903 of these probesets targeted an exon that was identified in the brain transcriptome reconstruction. Probesets were removed from further analysis if they were not expressed above background (DABG p-value<0.0001) in at least 50% of samples (112,279 probe sets remaining). When multiple probesets targeted the same gene, the probesets were placed into transcript clusters based on their correlations with each other across strains, and summarized into a single quantitative measurement for each cluster and each brain sample. Each cluster represents a transcript, and expression values for 39,819 clusters (derived from 14,438 genes) were used to identify candidate transcripts.

Candidate Transcripts for DID

Of the initial 39,819 transcript clusters considered for analysis, 7,491 passed the heritability criterion (r2≥0.33). Of those, 919 had a significant eQTL that occurred in the same genomic region as a DID phenotype QTL, and five of these transcript clusters were significantly correlated with the DID phenotype levels across the LXS RI strains. These 5 “candidate transcripts”, along with a brief description of the functions of the transcript products, are listed in Table 3. Each of these transcripts is referred to by the name of the gene from which it is derived (“candidate gene”).

Table 3.

Candidate Genes Predisposing Variation in DID Alcohol Consumption.

| Transcript Information |

Male DID Phenotype Correlation |

eQTL information | Gene Product Function | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name |

Physical Location: Chr (Mb) |

Coefficient |

Nominal p-value (FDR) |

eQTL Location Chr (Mb) |

LOD Score (p-value) |

|

| Trim62 | tripartite motif-containing 62 | 4 (128.9) | −0.62 | 0.0001 (0.037) |

4 (128.6) | 7.5 (<0.0001) | RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase (Huang et al. 2013) |

| Wrn | Werner syndrome homolog (human) |

8 (33.3) | −0.59 | 0.0002 (0.037) |

4 (124.9) | 8.8 (<0.0001) | RecQ-type DNA helicase involved in DNA repair, replication, transcription; deficiency leads to premature age-associated pathologies (Werner Syndrome) (Turaga et al. 2009). |

|

Gtf3c1 (TFIIIC) |

general transcription factor III C 1 |

7 (125.6) | 0.58 | 0.0003 (0.037) |

7 (125.2) | 7.1 (<0.0001) | Transcription factor that interacts with tDNAs (tRNA genes) that act as chromatin insulators. Plays a key role in genome organization allowing for changes in gene transcription (Van Bortle and Corces 2012). |

| Pld5 | phospholipase D family, member 5 |

1 (176.0) | 0.58 | 0.0004 (0.037) |

1 (175.6) | 20.7 (<0.0001) | Converts phosphatidylinositol 3, 4, 5- trisphosphate to inositol 3, 4, 5 trisphosphate and phosphatidic acid (Ching et al. 1999). |

|

Arntl (Bmal1) |

aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like |

7 (113.2) | −0.55 | 0.0007 (0.060) |

7 (124.6) | 3.8 (0.0260) |

Transcription factor, core component of mammalian circadian rhythm system; regulates behavioral, physiological and chromatin modification rhythms (Hatanaka et al. 2010; Menet et al. 2014; Mieda and Sakurai 2011). |

Candidate genes were identified based on significant correlation of transcript clusters with the male DID phenotype and eQTL overlap with DID phenotype QTL.

The correlation structure among the probesets for each candidate transcript was compared with the expected structure based on the transcriptome reconstruction by examining the positions of the probeset(s) included in the expression values for the candidate transcripts (see Supplemental Gene Report). For Trim62, only one isoform was expressed in brain and all four probesets that aligned to its exons were correlated and placed into the cluster that was associated with the DID phenotype. For Arntl, 11 out of the 13 probesets, that aligned to the only isoform of Arntl detected in the reconstruction, were correlated and formed the cluster that was associated with the DID phenotype. The two probesets that did not correlate were located in the 3’ and 5’ regions of the gene, where the accuracy of the reconstruction is reduced. For Pld5, 8 out of 9 probesets were correlated and formed the cluster associated with the DID phenotype. This gene has 4 isoforms expressed in brain and the one probeset that was not correlated with the other eight targeted an exon that was specific to a single isoform of Pld5. For Wrn and Gtf3c1, the correlation structure among the probesets did not match expectations based on the transcriptome reconstruction. Although several probesets targeted exons in each gene, the probesets were not tightly correlated. In both cases, the expression value that was associated with the DID phenotype was calculated from a single probeset. These expression values met all of our filtering criteria (detection above background, heritability, a significant eQTL that overlaps a phenotype QTL, and significant correlation with the DID phenotype).

Discussion

The results obtained in this study identify several genomic regions associated with the level of alcohol consumed by strains of the LXS panel of recombinant inbred (RI) mice in the “drinking in the dark” (DID) model. Most previous studies, including our own (Saba et al. 2011), have used data from a single day of the DID paradigm to characterize alcohol consumption (Rhodes et al. 2005; 2007). For the current analysis, we chose to use all of the data, but to reduce the dimensionality by using principal component analysis of drinking measures over three days of the DID paradigm. When the data are highly correlated, as we found for the DID data across days, the first principal component accounts for the majority of variation between samples, and is often similar to the average of the original data. In this case, since loadings for the first principal component were similar across the three time points, the first principal component can be interpreted as a robust measure of DID in this population. By taking a summary measure within a mouse, we reduced the environmental/technical variance in the DID phenotype, further isolating the genetic variance of interest. For example, the heritability of the drinking measures, when calculated separately for each day, never exceeded 33.3% in females or 39.5% in males, but the heritability of the first principal component was 43% in females and 48% in males.

Three of the five DID phenotype QTL regions identified in the current work (Chr 1: 66.6–194.7 Mb; Chr 4: 95.9- 129 Mb; Chr 19: 0–27.5 Mb) overlap with QTLs that we found in a prior analysis of DID alcohol consumption on day 3 by male LXS mice (Saba et al. 2011). It is likely that the identification of two other DID phenotype QTLs in the present work was possible because of the greater power gained by the addition of data from the female mice. However, the newly identified QTLs could also reflect the difference in phenotype measure (first principal component vs. drinking on day 3) used in the two studies. DID QTLs have also been determined using animals that have been selected for high levels of DID alcohol consumption (HDID-1 and HDID-2) and the stock from which these mice were selected (HS/NPT) (Iancu et al. 2013). In that analysis, data from male and female animals were combined, and one of the three identified QTL regions was close to the QTL that we identified on chromosome 4, which, in our study, did not show a sex by genotype interaction. It may not be surprising that other unique QTLs were identified in the analysis of HDID mice compared to the present work, given that some of the inbred strains used to generate the HS/NPT stock (Iancu et al. 2013) were different from the strains used to generate the HS/Ibg stock that was the founder for the LXS mice (McClearn and Kakihana 1981). In addition, the phenotype used for selection of the HDID lines is based on the blood ethanol concentration (BEC) obtained during DID on day 4 (Crabbe et al. 2009), which is related to the alcohol consumption levels, but may also include other factors.

The literature regarding the genetic relationship of DID to alcohol preference, measured in a 2-bottle choice paradigm, has previously been investigated. The DID model was originally described for alcohol-preferring C57BL/6 mice, which were found to achieve relatively high blood ethanol concentrations when given ethanol for 4 hours on day 4 of the DID procedure (Rhodes et al. 2005), and to consume amounts of alcohol that led to intoxication (Rhodes et al. 2007). A comparison of several inbred mouse strains showed differences in alcohol intake in the DID paradigm, indicating a genetic influence on DID alcohol consumption levels (Rhodes et al. 2007). In addition, correlations across strains for alcohol intake in the DID procedure and in two-bottle choice alcohol preference paradigms suggested that some of the same genes may influence DID and 2-bottle choice alcohol consumption levels (Rhodes et al. 2007). A study of alcohol preference by mice that had been selectively bred for high DID (HDID-1 mice), compared to the founder HS/NPT mice, also concluded that some of the same genetic factors affect both DID and alcohol preference measures (Crabbe et al. 2011). The QTL analyses performed in the current study support the suggestion that there are some common genetic influences on DID and 24-hour 2-bottle choice alcohol consumption. The DID phenotype QTLs that we identified on mouse chromosomes 4 and 7 (no sex by genotype interactions) overlap with QTLs previously reported for two-bottle choice alcohol consumption by: 1) BXD RI mouse strains (Phillips et al. 1994, female mice; Rodriguez et al. 1995, male mice); 2) mapping populations derived from C57BL/6 and DBA/2 strains (Belknap and Atkins 2001); and 3) an F2 population from a C57BL/6By x 129P3 intercross (Bachmanov et al. 2002). In addition to these overlapping QTL regions for the DID and 2-bottle choice phenotypes, however, unique QTLs have been identified for each phenotype, which may reflect differences in genetic influences on the phenotypes, as well as differences in the alleles represented in the different mouse strains.

Our analysis also indicated a significant sex by genotype interaction for some of the DID phenotype QTLs. The QTLs on Chr 1 and Chr 19 were specific to males. Sex-specific QTLs have previously been reported for alcohol preference drinking by mice. In a study using AXB/BXA RI mouse strains, both male- and female-specific QTLs were identified for 2-bottle choice alcohol consumption; the female-specific QTL was close to a female-specific QTL that had previously been mapped in C57BL/6 x DBA/2 backcrosses (Gill et al. 1998; Melo et al. 1996). In a study of selected lines of high and low alcohol-preferring mice (HAP and LAP mice), a chromosome 9 QTL was found to have a greater effect in female than in male mice (Bice et al. 2006). Female-specific QTLs for alcohol drinking have also been found in rats by Vendruscolo et al. (2006) and Izidio et al. (2011). In general, the finding of female-specific QTLs has been attributed to the effects of sex hormones on behavior (Izidio et al. 2011; Vendruscolo et al. 2006), which can interact with genetic factors that influence those behaviors. The influence of hormone levels on alcohol consumption in the DID paradigm has not been assessed, but our findings of differential effects of several QTLs on alcohol consumption by males and females suggests that such studies are needed.

Our results indicate that the overall genetic variance explained by the identified QTLs in females is less than the genetic variance explained by the QTLs in males, since three of the QTLs have no effect on the DID phenotype in females. On the other hand, the heritability for the DID phenotype was very similar in males and females (48.2 and 42.6 %, respectively). Given that heritability is defined as the proportion of phenotypic variation that is due to genetic variation, one can speculate that there may be more QTLs with small effect sizes in the females that contribute to the DID phenotype, but that were not detectable in the current analysis. Such QTLs are likely to be affected by environmental factors, including the hormonal status of the females, which may affect drinking behavior via alterations in gene expression levels or other biochemical mechanisms.

It is important to emphasize that our analysis identified QTLs from brains of alcohol-naïve LXS mice, and thus, the QTLs are associated with a predisposition to consume varying amounts of alcohol in the DID paradigm. The candidate genes that are regulated from within the identified QTL regions suggest an important genetic influence on circadian rhythms, which in turn generate differences in DID alcohol consumption. It is particularly noteworthy that the product of Arntl (Bmal1) is a transcription factor that is a core component of the mammalian circadian rhythm system (Buhr and Takahashi 2013). Studies with knockout mice indicate that Bmal1 plays an important role in the entrainment of locomotor activity that occurs when animals are put on a restricted feeding schedule (Mieda and Sakurai 2011; Zhang et al. 2012). The DID paradigm is reminiscent of the restricted feeding protocol, in that alcohol is available only during a restricted period. There have been numerous studies that suggest a link between alcohol consumption and circadian rhythms, e.g., lines of mice and rats selected for high and low alcohol preference also display differences in circadian phenotypes (Hofstetter et al. 2003; McCulley et al. 2013; Rosenwasser et al. 2005). Such results were interpreted as providing evidence that some similar genes may influence alcohol consumption and circadian control of activity, but the genes were not identified. Our data suggest that Bmal1 may be one of these genes. A study of mice selected for high DID (HDID mice) found that the HDID mice displayed lower running wheel (locomotor) activity than their HS/NPT controls during the early period of the dark cycle, when alcohol was accessible (McCulley et al. 2013). It was suggested that the lower activity could contribute to their drinking patterns. This would seem counter to the role of Bmal1 in the entrainment of activity associated with the restricted food access paradigm, i.e., in this paradigm, animals show increased locomotor activity prior to and during food accessibility (Verwey and Amir 2009). However, Bmal1 expression was lower in brains of the LXS mice that showed higher alcohol consumption in the DID model (Table 3). The lower Bmal1 expression would be expected to result in lower locomotor activity in these mice during the period of restricted access to alcohol (Mieda and Sakurai 2011). Since our candidate gene results are based on whole brain transcriptional analyses, it is important to note that Bmal1 expression in regions of the brain outside of the suprachiasmatic nucleus were implicated in the adaptation to food restriction (Mieda and Sakurai 2011).

Another candidate gene, Pld5 (phospholipase D, family member 5) converts phosphatidylinositol 3, 4, 5-trisphosphate to inositol 3, 4, 5 triphosphate (Ching et al. 1999), which can increase intracellular Ca2+ levels through an action at IP3 receptors (Nerou et al. 2001). There is substantial evidence for a role of inositol trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release in regulation of mammalian circadian rhythms (Baez-Ruiz and Diaz-Munoz 2011; Hamada et al. 1999; Mason and Biello 1992; Takimoto et al. 1985). Therefore, Pld5 and Bmal1 may both contribute to aspects of circadian control that influence DID alcohol consumption levels.

Most of the other candidate genes that we identified can be related to the activity and regulation of Bmal1, lending credence to the important role of circadian regulation in predisposing mice to differences in DID alcohol consumption. In particular, chromatin dynamics have been reported to play a crucial role in the transcriptional programs that control circadian rhythms in animal behavior, physiology and metabolism, as well as in the light response in plants (Barneche et al. 2014; Hardin and Panda 2013). Bmal1 promotes rhythmic chromatin modification (Menet et al. 2014), which allows for genome-wide circadian changes in regulation of chromatin accessibility and transcriptional activity. Another of the candidate genes, Gtf3c1, also known as TFIIIC, is a transcription factor that is thought to play a key role in genome organization (Van Bortle and Corces 2012), and can control the relocation of inducible, activity-dependent genes to “transcription factories” (Crepaldi et al. 2013). Cooperative interactions between TFIIIC and Bmal1, both of which are located in, and regulated from, the chromosome 7 QTL, have not been investigated, but could influence the complex transcriptional modifications related to circadian activity. Post-translational modifications, such as ubiquitination, of the proteins that regulate circadian rhythm, are crucial for maintenance of that rhythm. Bmal1 has been shown to be regulated by an E3 ubiquitin ligase (UBE3A) (Gossan et al. 2014), and notably, one of the other candidate genes from our analysis is Trim62, a RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase (Huang et al. 2013). Given the pleiotropic effects of many of the TRIM family proteins (Napolitano and Meroni 2012), one can speculate that Trim62 could be involved in the control of degradation of clock proteins. Bmal1 also regulates metabolic activity (Hatanaka et al. 2010), and its deficiency is associated with metabolic changes associated with a premature aging phenotype (Hemmeryckx et al. 2011). A deficiency of the candidate gene Wrn also leads to premature onset of age-related pathologies (Turaga et al. 2009).

In the present study, gene expression data were only available for male LXS mice, and the candidate genes were identified based on correlation with the DID phenotype in males. The lack of availability of brain gene expression data from female LXS mice did not allow a determination of candidate genes in females. The DID phenotype was not perfectly correlated across LXS strains for males and females (correlation coefficients across all three days, 0.49–0.59), and sex-specific eQTLs (particularly trans-eQTLs) have been reported in mice (van Nas et al. 2010). Therefore, it will be necessary to characterize the brain transcriptome in the female LXS mice in order to determine whether similar candidate genes and/or a similar molecular mechanism may be involved in the predisposition for DID alcohol consumption by females. Overall, however, our results provide an intriguing insight into the genetic mechanisms that influence alcohol consumption in the DID paradigm, and which may lead to the intake of large amounts of alcohol by certain individuals under these conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIAAA/NIH (R24AA013162, U01AA16649) and the Banbury Fund. We thank Dr. Tom Johnson, Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO and Dr. Gary Churchill, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, for providing SNP information on the LXS panel. We thank Yinni Yu and Adam Chapman for expert technical assistance with the microarray experiments.

References

- Bachmanov AA, Reed DR, Li X, Li S, Beauchamp GK, Tordoff MG. Voluntary ethanol consumption by mice: genome-wide analysis of quantitative trait loci and their interactions in a C57BL/6ByJ x 129P3/J F2 intercross. Genome research. 2002;12:1257–1268. doi: 10.1101/gr.129702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baez-Ruiz A, Diaz-Munoz M. Chronic inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum calcium-release channels and calcium-ATPase lengthens the period of hepatic clock gene Per1. Journal of circadian rhythms. 2011;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barneche F, Malapeira J, Mas P. The impact of chromatin dynamics on plant light responses and circadian clock function. Journal of experimental botany. 2014;65:2895–2913. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap JK, Atkins AL. The replicability of QTLs for murine alcohol preference drinking behavior across eight independent studies. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 2001;12:893–899. doi: 10.1007/s00335-001-2074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bice PJ, Foroud T, Carr LG, Zhang L, Liu L, Grahame NJ, Lumeng L, Li TK, Belknap JK. Identification of QTLs influencing alcohol preference in the High Alcohol Preferring (HAP) and Low Alcohol Preferring (LAP) mouse lines. Behavior genetics. 2006;36:248–260. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-9019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr ED, Takahashi JS. Molecular components of the Mammalian circadian clock. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2013:3–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-25950-0_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching TT, Wang DS, Hsu AL, Lu PJ, Chen CS. Identification of multiple phosphoinositide-specific phospholipases D as new regulatory enzymes for phosphatidylinositol 3,4, 5-trisphosphate. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:8611–8617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Metten P, Rhodes JS, Yu CH, Brown LL, Phillips TJ, Finn DA. A line of mice selected for high blood ethanol concentrations shows drinking in the dark to intoxication. Biological psychiatry. 2009;65:662–670. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Phillips TJ, Belknap JK. The complexity of alcohol drinking: studies in rodent genetic models. Behavior genetics. 2010;40:737–750. doi: 10.1007/s10519-010-9371-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Spence SE, Brown LL, Metten P. Alcohol preference drinking in a mouse line selectively bred for high drinking in the dark. Alcohol. 2011;45:427–440. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaldi L, Policarpi C, Coatti A, Sherlock WT, Jongbloets BC, Down TA, Riccio A. Binding of TFIIIC to sine elements controls the relocation of activity-dependent neuronal genes to transcription factories. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill K, Desaulniers N, Desjardins P, Lake K. Alcohol preference in AXB/BXA recombinant inbred mice: gender differences and gender-specific quantitative trait loci. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 1998;9:929–935. doi: 10.1007/s003359900902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossan NC, Zhang F, Guo B, Jin D, Yoshitane H, Yao A, Glossop N, Zhang YQ, Fukada Y, Meng QJ. The E3 ubiquitin ligase UBE3A is an integral component of the molecular circadian clock through regulating the BMAL1 transcription factor. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:5765–5775. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T, Liou SY, Fukushima T, Maruyama T, Watanabe S, Mikoshiba K, Ishida N. The role of inositol trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release from IP3-receptor in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus on circadian entrainment mechanism. Neuroscience letters. 1999;263:125–128. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin PE, Panda S. Circadian timekeeping and output mechanisms in animals. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2013;23:724–731. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatanaka F, Matsubara C, Myung J, Yoritaka T, Kamimura N, Tsutsumi S, Kanai A, Suzuki Y, Sassone-Corsi P, Aburatani H, Sugano S, Takumi T. Genome-wide profiling of the core clock protein BMAL1 targets reveals a strict relationship with metabolism. Molecular and cellular biology. 2010;30:5636–5648. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00781-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmeryckx B, Himmelreich U, Hoylaerts MF, Lijnen HR. Impact of clock gene Bmal1 deficiency on nutritionally induced obesity in mice. Obesity. 2011;19:659–661. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstetter JR, Grahame NJ, Mayeda AR. Circadian activity rhythms in high-alcohol-preferring and low-alcohol-preferring mice. Alcohol. 2003;30:81–85. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Xiao H, Sun BL, Yang RG. Characterization of TRIM62 as a RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase and its subcellular localization. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;432:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iancu OD, Oberbeck D, Darakjian P, Metten P, McWeeney S, Crabbe JC, Hitzemann R. Selection for drinking in the dark alters brain gene coexpression networks. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2013;37:1295–1303. doi: 10.1111/acer.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izidio GS, Oliveira LC, Oliveira LF, Pereira E, Wehrmeister TD, Ramos A. The influence of sex and estrous cycle on QTL for emotionality and ethanol consumption. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 2011;22:329–340. doi: 10.1007/s00335-011-9327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome biology. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason R, Biello SM. A neurophysiological study of a lithium-sensitive phosphoinositide system in the hamster suprachiasmatic (SCN) biological clock in vitro. Neuroscience letters. 1992;144:135–138. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90734-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClearn GE, Kakihana R. Selective breeding for ethanol sensitivity: Short-sleep and long-sleep mice. In: McClearn GE, Deitrich RA, Erwin VG, editors. Development of Animal Models of Pharmacogenetic Tools. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1981. pp. 81–113. [Google Scholar]

- McCulley WD, 3rd, Ascheid S, Crabbe JC, Rosenwasser AM. Selective breeding for ethanol-related traits alters circadian phenotype. Alcohol. 2013;47:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo JA, Shendure J, Pociask K, Silver LM. Identification of sex-specific quantitative trait loci controlling alcohol preference in C57BL/ 6 mice. Nature genetics. 1996;13:147–153. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menet JS, Pescatore S, Rosbash M. CLOCK:BMAL1 is a pioneer-like transcription factor. Genes & development. 2014;28:8–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.228536.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieda M, Sakurai T. Bmal1 in the nervous system is essential for normal adaptation of circadian locomotor activity and food intake to periodic feeding. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31:15391–15396. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2801-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano LM, Meroni G. TRIM family: Pleiotropy and diversification through homomultimer and heteromultimer formation. IUBMB life. 2012;64:64–71. doi: 10.1002/iub.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerou EP, Riley AM, Potter BV, Taylor CW. Selective recognition of inositol phosphates by subtypes of the inositol trisphosphate receptor. The Biochemical journal. 2001;355:59–69. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patro R, Mount SM, Kingsford C. Sailfish enables alignment-free isoform quantification from RNA-seq reads using lightweight algorithms. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32:462–464. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip VM, Duvvuru S, Gomero B, Ansah TA, Blaha CD, Cook MN, Hamre KM, Lariviere WR, Matthews DB, Mittleman G, Goldowitz D, Chesler EJ. High-throughput behavioral phenotyping in the expanded panel of BXD recombinant inbred strains. Genes, brain, and behavior. 2010;9:129–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Crabbe JC, Metten P, Belknap JK. Localization of genes affecting alcohol drinking in mice. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1994;18:931–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Best K, Belknap JK, Finn DA, Crabbe JC. Evaluation of a simple model of ethanol drinking to intoxication in C57BL/6J mice. Physiology & behavior. 2005;84:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Ford MM, Yu CH, Brown LL, Finn DA, Garland T, Jr., Crabbe JC. Mouse inbred strain differences in ethanol drinking to intoxication. Genes, brain, and behavior. 2007;6:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Archer MA, Wayne RK. Transgressive segregation, adaptation and speciation. Heredity. 1999;83(Pt 4):363–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6886170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LA, Plomin R, Blizard DA, Jones BC, McClearn GE. Alcohol acceptance, preference, and sensitivity in mice. II. Quantitative trait loci mapping analysis using BXD recombinant inbred strains. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1995;19:367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwasser AM, Fecteau ME, Logan RW, Reed JD, Cotter SJ, Seggio JA. Circadian activity rhythms in selectively bred ethanol-preferring and nonpreferring rats. Alcohol. 2005;36:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabinin AE, Galvan-Rosas A, Bachtell RK, Risinger FO. High alcohol/sucrose consumption during dark circadian phase in C57BL/6J mice: involvement of hippocampus, lateral septum and urocortin-positive cells of the Edinger-Westphal nucleus. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:296–305. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1284-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba LM, Bennett B, Hoffman PL, Barcomb K, Ishii T, Kechris K, Tabakoff B. A systems genetic analysis of alcohol drinking by mice, rats and men: influence of brain GABAergic transmission. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:1269–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya K, Ruskin HJ, Kerr G, Crane M, Becker J. Comparison of microarray preprocessing methods. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2010;680:139–147. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5913-3_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabakoff B, Saba L, Kechris K, Hu W, Bhave SV, Finn DA, Grahame NJ, Hoffman PL. The genomic determinants of alcohol preference in mice. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 2008;19:352–365. doi: 10.1007/s00335-008-9115-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabakoff B, Saba L, Printz M, Flodman P, Hodgkinson C, Goldman D, Koob G, Richardson HN, Kechris K, Bell RL, Hubner N, Heinig M, Pravenec M, Mangion J, Legault L, Dongier M, Conigrave KM, Whitfield JB, Saunders J, Grant B, Hoffman PL State WISo, Trait Markers of A. Genetical genomic determinants of alcohol consumption in rats and humans. BMC biology. 2009;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto K, Okada M, Matsuda Y, Nakagawa H. Purification and properties of myo-inositol-1-phosphatase from rat brain. Journal of biochemistry. 1985;98:363–370. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele TE, Navarro M. "Drinking in the dark" (DID) procedures: a model of binge-like ethanol drinking in non-dependent mice. Alcohol. 2014;48:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turaga RV, Paquet ER, Sild M, Vignard J, Garand C, Johnson FB, Masson JY, Lebel M. The Werner syndrome protein affects the expression of genes involved in adipogenesis and inflammation in addition to cell cycle and DNA damage responses. Cell cycle. 2009;8:2080–2092. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bortle K, Corces VG. tDNA insulators and the emerging role of TFIIIC in genome organization. Transcription. 2012;3:277–284. doi: 10.4161/trns.21579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nas A, Ingram-Drake L, Sinsheimer JS, Wang SS, Schadt EE, Drake T, Lusis AJ. Expression quantitative trait loci: replication, tissue- and sex-specificity in mice. Genetics. 2010;185:1059–1068. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.116087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlinden LA, Saba LM, Kechris K, Miles MF, Hoffman PL, Tabakoff B. Whole brain and brain regional coexpression network interactions associated with predisposition to alcohol consumption. PloS one. 2013;8:e68878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendruscolo LF, Terenina-Rigaldie E, Raba F, Ramos A, Takahashi RN, Mormede P. Evidence for a female-specific effect of a chromosome 4 locus on anxiety-related behaviors and ethanol drinking in rats. Genes, brain, and behavior. 2006;5:441–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwey M, Amir S. Food-entrainable circadian oscillators in the brain. The European journal of neuroscience. 2009;30:1650–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RW, Bennett B, Lu L, Gu J, DeFries JC, Carosone-Link PJ, Rikke BA, Belknap JK, Johnson TE. Genetic structure of the LXS panel of recombinant inbred mouse strains: a powerful resource for complex trait analysis. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 2004;15:637–647. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Abraham D, Lin ST, Oster H, Eichele G, Fu YH, Ptacek LJ. PKCgamma participates in food entrainment by regulating BMAL1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:20679–20684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218699110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.