Abstract

Age is the major risk factor in the incidence of cancer, a hyperplastic disease associated with aging. Here, we discuss the complex interplay between mechanisms underlying aging and cancer as a reciprocal relationship. This relationship progresses with organismal age, follows the history of cell proliferation and senescence, is driven by common or antagonistic causes underlying aging and cancer in an age-dependent fashion, and is maintained via age-related convergent and divergent mechanisms. We summarize our knowledge of these mechanisms, outline the most important unanswered questions and suggest directions for future research.

Keywords: aging, cancer, cell cycle, cellular senescence, cell death, cellular signaling

The relationship between mechanisms underlying aging and cancer evolves with the chronological age of an organism and, thus, reflects the proliferation history of cells and the chronology of their senescence program [1–8].

In young and adult organisms, cell-autonomous mechanisms that reduce the extent of cellular stress, damage and dysfunction are aimed at eliminating these common aetiologies of aging and cancer; as such, these mechanisms not only delay the aging process but also suppress tumor formation [1, 2, 8–10]. Because of a short proliferative history of cells in young and adult organisms, the biological clocks of cellular senescence operating in stem and progenitor cells do not limit their proliferation [11–16]. This enables an efficient mobilization of stem cells from their supportive niches to proliferate (thereby forming progenitor cells) and differentiate and, ultimately, to repair and regenerate renewable tissues by replacing their stressed, damaged or dysfunctional cells; these cells are still mitotically active and therefore at risk of accumulating potentially oncogenic lesions [13–19]. Such efficient and tightly regulated mobilization, proliferation and differentiation of stem and progenitor cells in young and adult organisms constitute a cell-nonautonomous mechanism that simultaneously delays aging and suppresses tumor formation [15, 16, 20, 21].

Cell-intrinsic stresses that are coupled to cell division, along with lasting cell-extrinsic stresses that are unrelated to replicative cell history, amass with the chronological age of an organism. In old organisms, the excessive accumulation of such stresses commits stem and progenitor somatic cells as well as mitotically active cells within renewable tissues to a senescence program that is initiated by cell cycle arrest [3, 4, 7, 8, 14, 22–26]. The resulting proliferative decline of these cells provides a cell-autonomous mechanism for tumor suppression at a premalignant stage by preventing the proliferation of excessively stressed or damaged cells that harbor potentially oncogenic lesions and are, therefore, at risk for malignant transformation [3, 4, 7, 8, 13, 22, 25, 27]. However, the cell cycle arrest at an early stage of the senescence program in stem/progenitor somatic cells and the resulting decline in their proliferation and mobilization to renewable and differentiated tissues not only suppresses cancer but also operates as a cell-nonautonomous pro-aging mechanism by compromising tissue repair and regeneration, and thereby impairing tissue homeostasis [2, 3, 7, 8, 11, 12, 22].

The complexity of the interplay between mechanisms underlying aging and cancer is further underscored by the findings implying that in old organisms: (1) paracrine activities of the senescent non-cancerous cells in a renewable tissue enable their interactions with mitotically active non-cancerous cells (in the same tissue or in other tissues) as well as with premalignant and tumor cells (in the same tissue or within the tumor microenvironment); and (2) these numerous interactions exhibit pleiotropic effects on aging and cancer, either beneficial or deleterious for the health of the organism [3–5, 7, 26, 28–30]. In fact, the cell cycle arrest at an early stage of the senescence program in stem/progenitor somatic cells and in division-competent cells within renewable tissues is followed by stepwise changes in chromatin organization and gene expression - which in turn alter secretion pattern of interleukins, inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, insoluble protein components of the extracellular matrix, extracellular proteases, as well as such non-protein soluble compounds as reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 [4, 5, 7, 19, 28–33]. Over time, cells at an advanced stage of the senescence program progress through several consecutive steps of developing a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) also called senescence-messaging secretome (SMS) [5, 7, 28, 31, 32]. Paracrine activities of various SASP components affect distant non-cancerous, premalignant and tumor cells through cell-nonautonomous mechanisms that underlie such diverse effects as: (1) tissue repair and regeneration; (2) wound healing; (3) cell senescence-based suppression of tumor growth; (4) disruption of structure and function of normal tissues and the resulting acceleration of age-related degenerative diseases; (5) low-level chronic inflammation; (6) immune clearance of non-cancerous, premalignant and tumor cells; (7) excessive proliferation of division-competent non-cancerous, premalignant and malignant cells; (8) enhanced cell migration and tissue invasion; (9) tissue-specific changes in cell differentiation; and (10) promotion of tumor progression [3–5, 7, 22, 26, 28–30, 34–36].

Recent studies provided another evidence of the complex interplay between mechanisms underlying aging and cancer by demonstrating that in old organisms ROS secreted by epithelial cancer cells activate aerobic glycolysis and autophagic degradation in associated non-cancerous fibroblasts within the tumor microenvironment - thereby causing their “accelerated aging” and resulting conversion to cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [37–43]. By producing and then secreting growth-promoting nutrients, CAFs fuel oxidative mitochondrial metabolism in adjacent cancer cells – thereby promoting their proliferation to and ultimately facilitating tumor progression [37–43].

In sum, it seems that in old organisms aging and cancer may have common or differing causes and coalescent or divergent mechanisms. Such dualistic relationship between aging and cancer in old organisms is due to: (1) the antagonistically pleiotropic effects and complex temporal organization of the cellular senescence program executed in excessively stressed or damaged non-cancerous cells; and (2) the ability of cancer cells to accelerate aging of the senescent non-cancerous cells within the tumor microenvironment, thus extracting from these non-cancerous cells certain growth-promoting nutrients that fuel tumor progression.

In this review, we discuss the intricate interplay between aging and cancer as a balance between coalescent and divergent mechanisms underlying them. We focus on the current knowledge of how this delicate balance is: (1) impacted by organismal age; (2) influenced by the proliferative history of cells; (3) affected by the temporal organization of the cellular senescence process; and (4) impinged on by the antagonistically pleiotropic effects of senescent cells on aging- and cancer-related processes.

In young and adult organisms, cell-autonomous mechanisms that eliminate aetiologies of aging also suppress tumor formation

The emergence and accumulation of stressed, damaged and dysfunctional macromolecules and organelles in mitotically active cells within renewable issues of young and adult organisms are known to have both the pro-aging and pro-cancer potentials [1–8]. Therefore, cell-autonomous mechanisms that in young and adult organisms eliminate these common to aging and cancer aetiologies are expected to decelerate both the aging process and tumor formation [1–3, 5, 6, 8–10, 13, 44–46]. Because in young and adult organisms aging and cancer are likely to have common aetiologies and coalescent cell-autonomous mechanisms, it is conceivable that in these organisms: (1) genetic interventions that accelerate the build-up of stress, damage and dysfunction in mitotically active cells by targeting some of such mechanisms may exhibit both pro-aging and pro-cancer effects; and (2) genetic, pharmacological and/or dietary interventions that decelerate the accumulation of stress, damage and dysfunction in mitotically active cells by affecting some of such mechanisms may elicit both anti-aging and anti-cancer effects [1–3, 6, 10, 13, 44–46].

A body of evidence in support of the common aetiologies and coalescent cell-autonomous mechanisms for aging and cancer in young and adult organisms has been extensively reviewed over the last few years [5–8, 44–53]. In brief, the following three lines of evidence support this commonly accepted concept on the relationship between aging and cancer in mitotically active cells within renewable issues of such organisms.

First, all cellular processes that in young and adult organisms affect the common to aging and cancer aetiologies are orchestrated by an intricate signaling network; the network integrates several signaling pathways and is centered at the mammalian (or mechanistic) target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) [1, 2, 13, 44, 45, 48–55]. These signaling pathways regulate both cellular aging and tumorigenesis. They include: (1) the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/phosphatase and tensin homolog/Akt/mTOR (PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR) pathway; (2) the rat sarcoma/rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma/mitogen-activated protein kinase-extracellular-signal-regulated kinase/extracellular -signal-regulated kinase/mTOR (Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK/mTOR) pathway; and (3) the liver kinase B1/5’ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase/ mTOR (LKB1/AMPK/mTOR) pathway [1, 2, 9, 13, 44–46, 48–52, 54, 55]. By coordinating information flow along these convergent and multiply branched signaling pathways, the network orchestrates such common to aging and cancer cellular processes as ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis in the cytosol, glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway, lipid and nucleotide metabolism, mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle and respiration, mitochondrial ROS formation and decomposition, biogenesis of mitochondria and lysosomes, autophagy, cytoskeletal organization, stress response, and apoptosis [8, 44, 45, 48–52, 56–76].

Second, some protein components and downstream targets of the signaling network orchestrating cellular processes that in young and adult organisms affect the common to aging and cancer aetiologies have been shown to accelerate cellular aging and function as oncogenes. These protein components and downstream targets include PI3K, Ras, Raf, Akt, Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb), the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), the hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α (HIF1-α), mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase subunits SDHB, SDHC and SDHD, the mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase assembly factor 2 (SDHAF2), and mitochondrial fumarate hydratase FH [46, 48–50, 59, 71, 72]. In contrast, other protein components and downstream targets of this signaling network have been shown to decelerate cellular aging and to act as tumor suppressors; they include PTEN, LKB1, the tuberous sclerosis proteins 1 and 2 (TSC1 and TSC2), the Von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor protein VHL, Ras inhibitors NF1 and NF2, and mitochondrial isocitrate dehydrogenases IDH1 and IDH2 [46, 48–50, 59, 71, 72].

Third, certain pharmacological interventions, a caloric restriction (CR) diet and some dietary restriction (DR) regimens exhibit both anti-aging and anti-cancer effects by specifically altering information flow along the PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR, Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK/mTOR and/or LKB1/AMPK/mTOR signaling pathways as well as by modulating some of the downstream targets of these pathways. As it has been mentioned above in this section, the PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR, Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK/mTOR and LKB1/AMPK/mTOR pathways are integrated into a signaling network orchestrating cellular processes that in young and adult organisms affect the common to aging and cancer aetiologies. The cell-autonomous mechanisms that underlie both anti-aging and anti-cancer effects of such pharmacological interventions, CR and DR have been comprehensively discussed elsewhere [9, 44–46, 48–50, 62–69, 71–85].

In old organisms, multiple mechanisms underlying a multistep cellular senescence program impose antagonistically pleiotropic effects on aging and cancer

In response to excessive intracellular and extracellular stresses, mitotically active stem/progenitor somatic cells and division-competent cells within renewable tissues enter a senescence program that is initiated by an irreversible cell cycle arrest [3, 4, 7, 8, 24, 28, 32, 86]. Some senescence-inducing stresses are coupled to cell division; because these stresses reflect the replicative history of division-competent cells, they function as biological clocks counting the finite number of cell divisions progressing with the chronological age of an organism [4, 7, 12–14, 22, 87–91]. Other stresses triggering cellular senescence do not relate directly to the replicative age of cells, and thus may not operate as “replicometers” or “mitotic clocks” set to count the progression of cell divisions with organismal chronological age [4, 7, 22, 25, 90]. The various stresses triggering cellular senescence generate certain intracellular signals modulating a distinct set of senescence-inducing signaling pathways [1, 3, 5, 7, 12, 22, 86]. These pathways are integrated into circuits that orchestrate a cellular senescence program progressing through several spatially and temporally distinct steps [1, 3, 5, 22, 86, 92–96]. Multiple mechanisms underlying the spatiotemporal organization of this program impose antagonistically pleiotropic effects on aging and cancer, as outlined in this section.

Triggers, sensors, signaling pathways and circuits of the cellular senescence program

A replicative mode of cellular senescence can be triggered by the following two kinds of intrinsic stresses that are coupled to cell division: (1) the gradual loss of telomeric DNA elements at S phases of successive mitotic cell divisions leading to telomeric dysfunction and causing a form of cellular senescence known as telomere-initiated senescence; and (2) the steady rise in the expression of the INK4a/ARF locus leading to a progressing with the proliferative history of cells accumulation of the p16INK4a and p14ARF tumor suppressor proteins [1, 11–13, 22, 86–89, 91]. Some stresses can trigger a mode of cellular senescence known as premature or stress-induced senescence; these stresses include: (1) an accumulation of unrepaired damage to chromosomal DNA and the resulting genomic damage at non-telomeric sites; (2) chromatin remodeling resulting in heterochromatin foci formation and large-scale chromatin condensation; (3) oncogene overexpression/ activation or tumor suppressor gene inactivation, all causing a so-called oncogene-induced form of cellular senescence; (4) an enhanced expression of cell proliferation activators that create robust mitogenic signals; (5) an excessive proliferation of dysfunctional mitochondria, which results in ROS accumulation and oxidative stress; (6) autophagy induction; and (7) changes in expression patterns of numerous microRNAs [3, 4, 7, 12, 22, 23, 86, 97–116]. Because these stresses are not coupled to cell division (and thus do not relate directly to the replicative age of cells, sometimes being called cell-extrinsic stresses), they are unlikely to function as molecular chronometers that count the number of successive mitotic cell divisions progressing with organismal chronological age [4, 12, 22, 86, 90].

When the extent of cellular stress, damage and dysfunction inflicted by a combined action of various triggers of replicative and premature senescence reaches a threshold level, mitotically active cells respond by activating a multistep senescence program that is initiated by an irreversible cell cycle arrest [3, 4, 7, 22, 24, 28, 86]. The cell cycle arrest and the ensuing downstream events of the cellular senescence program are orchestrated by complex circuits integrating several signaling pathways and networks, including: (1) the p14ARF/p53 and p16INK4a/pRB tumor suppressor pathways, two master regulator pathways of senescence that are activated by various cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic stresses in a parallel- (in human fibroblasts) or linear (in mouse fibroblasts) fashion; (2) the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK/mTOR oncogene signaling pathway; (3) the PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR nutrient-sensing signaling pathway; (4) the Wnt/HIRA/ASF1a/UBN1 chromatin remodeling pathway; and (5) the C/EBPβ- and NFκB-governed senescence secretome transcriptional network [3, 4, 5, 12–14, 22, 33, 44, 45, 86, 117–138]. These signaling pathways: (1) transmit signals generated by sensor and effector proteins in response to individual senescence triggers (cell-intrinsic or cell-extrinsic) or to their combinations; (2) are linked via a series of connections; (3) are integrated into circuits by the p14ARF/p53 and p16INK4a/pRB master regulator pathways of senescence; (4) govern the spatiotemporal organization of the multistep cellular senescence program; and (5) elicit various hallmark features of the senescent phenotype [3, 5, 12, 13, 22, 44, 86, 124]. A detailed description of the signaling circuitry characteristic of the cellular senescence program is beyond the scope of this review; the recent significant progress in this area has been comprehensively summarized elsewhere [3, 5, 12, 22, 44, 86, 124].

The complexity and spatiotemporal organization of the cellular senescence program

When mitotically active cells respond to excessive intracellular and extracellular stresses in culture or in vivo by entering a state of senescence, they undergo various morphological and functional changes to acquire a number of features (Tables 1 and 2). Some of these features are often observed not only in different types of cultured cells exposed to various triggers of either replicative or premature (stress-induced) mode of cellular senescence, but also in senescent cells derived from several organismal tissues. These features therefore are likely to serve as hallmarks of a state of cellular senescence and to be used as diagnostic biomarkers of cells entered such a state in different tissues. A body of evidence supports the view that these hallmarks/biomarkers of senescent cells may include: (1) cell enlargement and acquisition of a flat or spindle-like shape [5, 22, 139, 140]; (2) cell cycle arrest (which is an irreversible process in vivo, but in culture can be reversed by certain genetic manipulations) [5, 7, 12, 97–99, 139, 141, 142]; (3) increased size and number of lysosomes, many of which are non-functional due to accumulation of lipofuscin-like indigestible molecular aggregates [140, 143–148]; (4) an elevated activity of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-Gal) detectable at pH 6 [140, 147, 149–151]; (5) an excessive proliferation of mitochondria that are elongated, interconnected to form an extensive network, aggregated, depolarized, dysfunctional, impaired in ATP synthesis, and produce excessive quantities of ROS [140, 147, 152–161]; (6) a permanent establishment of DNA damage nuclear foci that are marked with a set of the DNA damage response (DDR) proteins and known as DNA segments with chromatin alterations reinforcing senescence (DNA-SCARS), DNA double-strands breaks (DSBs), senescence-associated

Table 1.

Features of senescent cells that can serve as hallmarks of a state of cellular senescence and/or can be used as diagnostic biomarkers of senescent cells existing in organismal tissues

| Affected aspect of cell morphology and function | Feature of senescent cells | Observed | Can serve as a hallmark/diagnostic biomarker of senescent cells | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in vitro* | in vivo** | ||||

| Cell size and shape | Cell enlargement and acquisition of a flat or spindle-like shape | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 22, 139, 140 |

| Cell cycle | Cell cycle arrest - which is an essentially irreversible in vivo, but in culture can be reversed by certain genetic manipulations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 12, 97–99, 139,141, 142 |

| Lysosomes | Increased size and number of lysosomes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 140, 143, 145, 146 |

| Many lysosomes become non-functional due to accumulation of lipofuscin-like indigestible molecular aggregates | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 140, 144, 146 | |

| Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-Gal) | Elevated activity of SA β-Gal detectable at pH 6 - likely due to a senescence-associated increase in the level of lysosomal β-Gal protein, which exhibits the highest activity at pH 4, but if becomes abundant can also be detected at suboptimal pH 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 140, 147, 149–151 |

| Mitochondria | Excessive proliferation of mitochondria that are elongated, highly interconnected to form an extensive network, and aggregated | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 140, 152, 154, 157 |

| Depolarization of the mitochondrial inner membrane, mitochondrial dysfunction, reduced ATP synthesis in mitochondria, and accumulation of ROS (that are produced mostly in mitochondria) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 140, 153, 157–161 | |

| DNA damage foci | Permanent establishment of nuclear foci marked with a set of the DNA damage response (DDR) proteins; these stable foci are known as DNA segments with chromatin alterations reinforcing senescence (DNA-SCARS), DNA double-strands breaks (DSBs), senescence-associated DNA-damage foci (SDF) and telomere dysfunction-induced foci (TIF) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4, 12, 22, 25, 111, 140, 162–168 |

| Nuclear bodies | Formation of promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies (PML NBs) also known as PML oncogenic domains (PODs); these sub-nuclear organelles concentrate numerous DNA-binding proteins that initiate heterochromatin establishment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 103, 124, 169–171 |

| Heterochrom atic DNA foci | PML NBs-instigated formation of senescence-associated heterochromatic foci (SAHF); these foci are enriched in methylated Lys 9 of histone H3 (a heterochromatin marker) and concentrate a set of heterochromatin-associated proteins | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4, 12, 172–177 |

| SASP/SMS | Specific changes in pattern of gene expression at transcriptional level - which result in secretion of a distinct set of interleukins, inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, insoluble protein components of the extracellular matrix, extracellular proteases, as well as such non-protein soluble compounds as ROS, nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4, 11, 22, 28, 31, 32, 165 |

Observed in cells entered a state of senescence in culture.

Observed in senescent cells recovered from organismal tissues.

Table 2.

Features of senescent cells that may or may not serve as hallmarks of a state of cellular senescence and may or may not be used as diagnostic biomarkers of senescent cells existing in organismal tissues

| Affected aspect of cell morphology and function | Feature of senescent cells | Observed | Can serve as a hallmark/diagnostic biomarker of senescent cells | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in vitro* | in vivo** | ||||

| Cell morphology | Cell multi-nucleation and extensive vacuolization | ✓ | ? | ? | 22, 263 |

| Cell motility and adhesion | Reduced cell motility; enhanced focal adhesion of cells to the extracellular matrix | ✓ | ? | ? | 140, 264, 265 |

| Cell-cell contact | Reduced efficacy of cell-cell contacts | ✓ | ? | ? | 86, 140 |

| Glycogen | Accumulation of glycogen granules, inactivating phosphorylation of the glycogen synthesis inhibitor GSK3, and activating dephosphorylation of glycogen synthase | ✓ | ✓ | ? | 140, 143, 266, 267 |

| Cytoskeleton | Reduced cellular level of actin; nuclear accumulation of G-actin, jointly with an active phosphorylated form of the actin depolymerizing factor cofilin | ✓ | ✓ | ? | 140, 268–270 |

| Elevated cellular level of the intermediate filament protein vimentin; elongation, condensation and linearization of the intermediate filaments containing vimentin | ✓ | ✓ | ? | 140, 271–273 | |

| Increased number of microtubule organizing center, which nucleates individual microtubules | ✓ | ? | ? | 140, 274 | |

| Lysosomes | Enhanced expression of numerous genes encoding lysosomal enzymes | ✓ | ? | ? | 140, 143, 147, 148 |

| Mitochondria | Reduced efficacy of mitochondrial fission and the resulting shift of the balance between mitochondrial fission and fusion towards fusion | ✓ | ? | ? | 140, 147, 155, 156 |

| Autophagy | Reduced efficacy of chaperone-mediated autophagy and non-selective macroautophagy, including mitophagy | ✓ | ? | ? | 114, 115, 125, 275–279 |

| Nucleus | Aberrant shape of the nucleus; reduced levels of the lamin A-associated protein LAP2 and several other nuclear proteins | ✓ | ✓ | ? | 140, 166, 280, 281 |

| Chromosomes | Chromosomal instability exhibited as polyploidy or aneuploidy | ✓ | ✓ | ? | 263, 282–288 |

| Senescence-associated microRNAs (SA-miRNAs) | Expression of numerous SA-miRNAs is altered (either elevated or reduced) in cultured cells undergoing senescence caused by cell exposure to various triggers of either replicative or premature (stress-induced) mode of cellular senescence; many of these SA-miRNAs play essential roles in regulating senescence of cultured cells by targeting the signaling circuitry characteristic of the cellular senescence program; at least one of these SA-miRNAs, miR-22, can induce cellular senescence in vivo | ✓ | ? | ? | 112, 113, 289–296 |

| Apoptosis | Resistance to apoptotic cell death elicited by certain pro-apoptotic stimuli | ✓ | ? | ? | 12, 196–202 |

Observed in cells entered a state of senescence in culture.

Observed in senescent cells recovered from organismal tissues.

DNA-damage foci (SDF), and telomere dysfunction-induced foci (TIF) [4, 12, 22, 25, 111, 140, 162–168]; (7) a formation of promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies (PML NBs) - also known as PML oncogenic domains (PODs) - that concentrate numerous DNA-binding proteins initiating heterochromatin establishment [103, 124, 169–171]; (8) a PML NBs-instigated formation of senescence-associated heterochromatic foci (SAHF) that concentrate a set of heterochromatin-associated proteins [4, 12, 172–177]; and 9) specific changes in cell transcriptome and the resulting stepwise development of a complex secretion pattern known as SASP and also called SMS [4, 11, 22, 28, 31, 32, 165] (Table 1). Importantly, none of the above features considered as probable hallmarks/biomarkers of senescent cells has been found to be common for all types cells entered a state of senescence in culture or in vivo. Therefore, only the simultaneous assessment of many of these features can identify cells entered such a state. Furthermore, it is conceivable that some of the features outlined in Table 2 can be elicited only in response to a particular trigger of a certain mode of cellular senescence and/or can be seen only in senescent cells confined to a specific tissue.

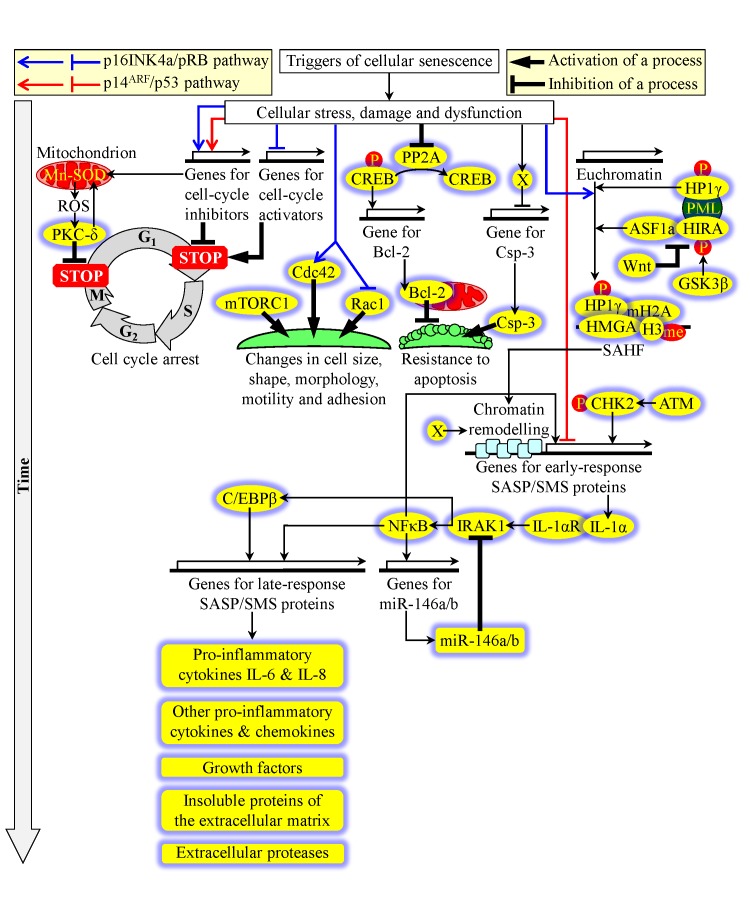

Recent findings strongly suggest that the numerous events characteristic of a state of cellular senescence (Tables 1 and 2) are organized into a multistep cellular senescence program. As outlined below in the section, the advancement of this program through spatially, temporally and mechanistically separable steps is orchestrated by complex circuits integrating several signaling pathways and networks (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The numerous events characteristic of a state of cellular senescence are organized into a multistep cellular senescence program. The advancement of this program through spatially, temporally and mechanistically separable steps is orchestrated by complex circuits integrating several signaling pathways and networks. For additional details, see text. Abbreviations: ASF1a/HIRA, anti-silencing function 1a/Histone Repressor A; ATM/CHK2, the DNA damage response kinases ataxia telangiectasia mutated/checkpoint kinase 2; Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2), an anti-apoptotic protein; Cdc25, a member of the Rho family of small GTPases; C/EBPβ, a transcriptional factor; CREB, cAMP responsive element binding protein; Csp-3, caspase-3; HMGA, High Mobility Group A proteins; HP1γ, Heterochromatin Protein 1 γ; H3, histone H3; IL-1α, an α isoform of the multifunctional cytokine IL-1; IL-1αR, a juxtaposed receptor of IL-1α; IRAK1, a protein kinase; miR, microRNA; Mn-SOD, manganese superoxide dismutase; mTORC1, mammalian (or mechanistic) target of rapamycin complex 1; NFκB, a transcriptional factor; PKC-δ, a δ isozyme of the protein kinase C; PML, promyelocytic leukemia; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; Rac1, a member of the Rho family of small GTPases; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SASP, a senescence-associated secretory phenotype; SAHF, senescence-associated heterochromatic foci; SMS, senescence-messaging secretome.

In response to excessive intracellular and extracellular stresses elicited by various senescence triggers, the p14ARF/p53 and p16INK4a/pRB tumor suppressor pathways alter transcription of genes encoding several key inhibitors and activators of cell cycle progression through the G1/S checkpoint – thereby establishing and maintaining a senescence-associated irreversible cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase (Figure 1) [7, 12, 97–99, 142]. Among the genes whose transcription is activated by these two master regulator pathways of cellular senescence is a gene for mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD). The activation of Mn-SOD expression significantly elevates mitochondrial production of hydrogen peroxide, a form of ROS that elicits a caspase-3 (Csp-3)-dependent activation of the protein kinase C-δ isozyme (PKC-δ). By establishing a positive feedback loop to sustain ROS/PKC-δ signaling, PKC-δ irreversibly blocks cytokinesis (Figure 1) [14, 124, 178–180]. Noteworthy, some genetic manipulations and senescence triggers in culture can cause a senescence-associated irreversible S, G2 or G2/M cell cycle arrest [12, 101, 181–183].

The p16INK4a/pRB tumor suppressor pathway also responds to various senescence triggers by modulating Rac1 and Cdc25. These two members of the Rho family of small GTPases then alter cytoskeleton dynamics and a pattern of gene transcription to orchestrate senescence-associated changes in cell size, shape, morphology, motility and adhesion (Figure 1) [124, 184–190]. Moreover, a significant enlargement of cells entering a state of senescence is caused by the AMPK/TOR signaling pathway, which promotes ribosome biogenesisand protein translation in the cytosol under the conditions of a senescence-associated irreversible cell cycle arrest (Figure 1) [9, 24, 80, 140, 191–195].

Cells that entered a state of senescence in culture are resistant to apoptotic death elicited by certain proapoptotic stimuli [12, 124, 196–202]. The resistance of these cells to apoptosis is due in part to elevated expression of a gene encoding the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein [124, 198, 203–207]. Transcription of this gene is activated by a phosphorylated form of the cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB). Several senescence triggers increase the level of phosphorylated CREB by causing inactivation of the protein phosphatase PP2A (which dephosphorylates it) - thereby promoting transcription of the Bcl-2 gene known to be stimulated by phosphorylated CREB (Figure 1) [124, 196, 207, 208]. Furthermore, the resistance of senescent cells to apoptosis can also be caused by the demonstrated ability of certain senescence triggers to repress transcription of a gene for the executioner caspases-3, perhaps by activating a yet-to-be-identified transcriptional repressor protein (Figure 1) [12, 201]. Of note, the preferential recruitment of p53 to the promoters of certain cell-cycle arrest genes in cultured cells becoming senescent can weaken its ability to activate transcription of such pro-apoptotic genes as TNFRSF10b, TNFRSF6 and PUMA - thus also contributing to the resistance of senescent cells to apoptosis [12, 209].

Formation of SAHF and the resulting global chromatin reorganization in cells entered a state of senescence is a multistep process [3, 174, 175, 177, 211]. It is initiated by chromosome condensation, which is driven by: (1) a pRB-orchestrated alteration of the cell-cycle gene expression profile; (2) a replacement of histone H1 by HMGA (High Mobility Group A) proteins during an early step of chromatin condensation; and (3) a governed by the ASF1a/HIRA (anti-silencing function 1a/Histone Repressor A) protein complex generation of nucleosome-dense heterochromatin (Figure 1) [3, 172–177, 210, 212–214]. The ASF1a/HIRA complex is established after GSK3β (Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 β) phosphorylates HIRA in the PML NBs; the activity of this histone chaperone is under negative control of the Wnt signaling pathway [3, 177, 215]. The associated with the condensed chromatin pool of histone H3 is then methylated to create binding sites for HP1γ (Heterochromatin Protein 1 γ; which is phosphorylated in the PML NBs) and the histone variant macroH2A, thereby finalizing the process of SAHF formation (Figure 1) [3, 173–175, 177, 210].

The cell cycle arrest and stepwise epigenomic changes at early stages of the senescence program are followed by the establishment of a specific pattern of gene expression that results in secretion of numerous proteins and non-protein soluble compounds (Figure 1). Over time, senescent cells progress through a multistep process of developing a complex secretion pattern known as SASP and also called SMS (Table 1) [4, 11, 22, 28, 31, 32, 165]. An initial step in this process involves a transcriptional activation of genes encoding at least two early-response SASP/SMS proteins, specifically α and β isoforms of the multifunctional cytokine IL-1 (Figure 1). A cascade of the DNA damage response kinases ATM/CHK2 (ataxia telangiectasia mutated/checkpoint kinase 2) as well as a governed by yet-to-be-identified proteins chromatin remodeling activate transcription of these genes, whereas the p14ARF/p53 tumor suppressor pathway represses it [3, 26, 28, 31, 112, 165, 172, 175, 210, 216]. A cell surface-bound pool of the IL-1α isoform then binds to its juxtaposed receptor IL-1αR, which in turn activates the downstream protein kinase IRAK1 to stimulate the transcriptional factors NFκB and C/EBPβ [4, 22, 26, 30, 112, 120, 123, 216–218]. These two factors activate transcription of genes encoding numerous late-response SASP/SMS proteins (including the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 and their protein receptors, other pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, growth factors, insoluble protein components of the extracellular matrix, and extracellular proteases) as well as the SA-miRNAs miR-146a and miR-146b (Figure 1) [4, 22, 28, 32, 112, 120, 123]. The spatiotemporal organization of SASP/SMS is modulated by a positive transcriptional feedback loop involving NFκB and by a negative post-transcriptional feedback loop involving miR-146a/b (Figure 1) [4, 30, 112, 219, 220].

Pleiotropic effects of the multistep cellular senescence program on aging and cancer

Multiple mechanisms underlying the advancement of the cellular senescence program through temporally and spatially separable steps impose antagonistically pleiotropic effects on aging and cancer.

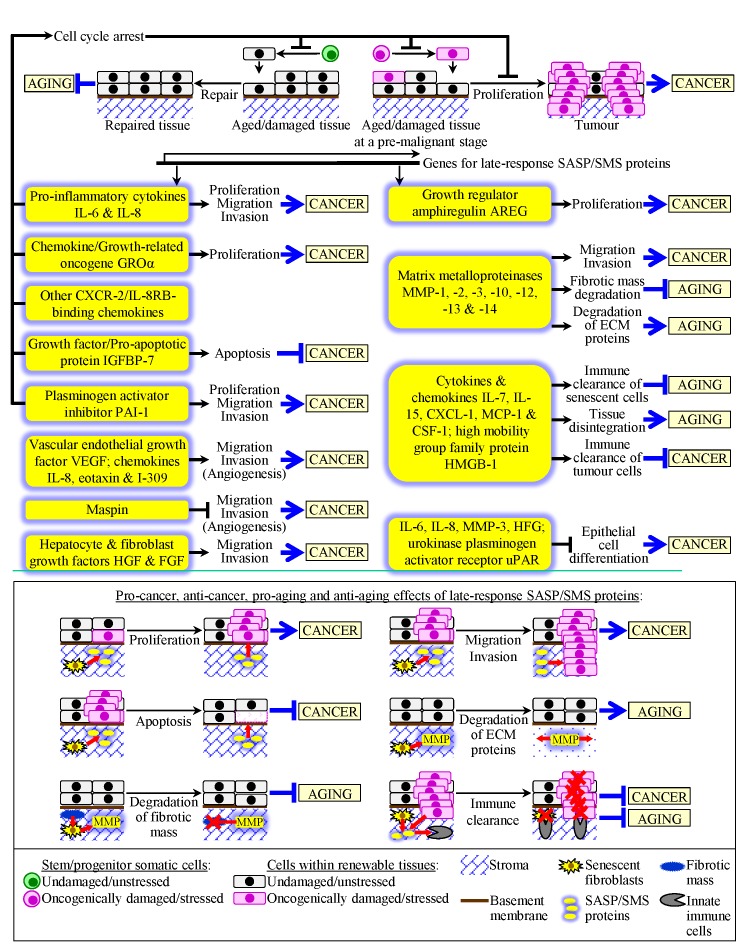

Both stem/progenitor somatic cells and mitotically active cells within renewable tissues respond to an accumulation of excessive cellular stress or damage by undergoing an irreversible cell cycle arrest and entering the cellular senescence program [1, 2, 4, 13, 14, 17, 18, 20–22, 25, 26]. The resulting proliferative decline of these somatic, progenitor and committed cells harboring potentially oncogenic lesions prevents their malignant transformation [1–4, 13, 22, 23, 25–27]. Thus, the irreversible cell cycle arrest at an early stage of the cellular senescence program provides a cell-autonomous mechanism for tumor suppression (Figure 2) [91]. The cell cycle arrest in stem/progenitor cells entering the senescence program also operates as a cell-nonautonomous pro-aging mechanism. Indeed, by declining the proliferation of these somatic cells and reducing their mobilization to renewable differentiated tissues, the senescence-associated irreversible cell cycle arrest compromises tissue repair and regeneration and ultimately impairs tissue homeostasis (Figure 2) [1, 2, 4, 12–14, 18, 20–22, 25–27, 91, 221, 222].

Figure 2.

Pleiotropic effects of a multistep cellular senescence program on aging and cancer. Multiple mechanisms underlying the advancement of the cellular senescence program through temporally and spatially separable steps impose antagonistically pleiotropic effects on aging and cancer. For additional details, see text. Abbreviations: CXCR-2/IL-8RB, a receptor of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-8; IGFBP-7, an insulin-like growth factor binding protein type 7; IGFBP-7, PAI-1, a plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1; SASP, a senescence-associated secretory phenotype; SMS, senescence-messaging secretome.

The senescence-associated irreversible cell cycle arrest and the ensuing stepwise changes in chromatin organization are followed by the ATM/CHK2- and p14ARF/p53-tuned transcriptional activation of genes encoding the early-response SASP/SMS proteins IL-1α and IL-1β (Figure 1) [4, 26, 28, 31, 112, 165, 172, 175, 210, 216]. The resulting activation of the autocrine IL-1α/IL-1αR signaling cascade in senescence-committed cells orchestrates a late-response SASP/SMS transcriptional program, which is driven by the transcriptional factors NFκB and C/EBPβ and which is fine-tuned by the NFκB- and miR-146a/b-dependent feedback loops (Figure 1) [4, 22, 26, 28, 30, 32, 112, 120, 123, 216–220]. The relative levels of various late-response SASP/SMS protein components are developed in a senescence trigger- and tissue context-dependent manner; the established extracellular molecular signature exhibits pleiotropic effects on aging and cancer, either beneficial or harmful for the health of the organism (Figure 2) [4, 22, 25, 26, 28–30, 32]. As outlined below in this section, many of the individual late-response SASP/SMS protein components impose several antagonistically pleiotropic pro-aging, anti-aging, pro-cancer and/or anti-cancer effects.

Such late-response SASP/SMS protein components as the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8, chemokine/growth-related oncogene GROα, chemokine ligands (other than IL-8 and GROα) of the CXCR-2/IL-8RB receptor, insulin-like growth factor binding protein IGFBP-7, and plasminogen activator inhibitor PAI-1 reinforce the senescence-associated cell cycle arrest – thereby sustaining both its cell-autonomous anti-cancer effect and its cell-nonautonomous pro-aging impact (Figure 2) [4, 25, 28, 32, 120, 123, 223–225]. However, by stimulating the proliferation of premalignant and malignant cells (IL-6, IL-8, GROα and PAI-1) as well as by promoting their migration and tissue invasion (IL-6, IL-8 and PAI-1), some of these protein components also exhibit a pro-cancer effect [4, 22, 26, 28, 31, 32, 226, 227]. Furthermore, one of them (namely, IGFBP-7) operates cell-nonautonomously as an anti-cancer protein not only by reinforcing the senescence-associated cell cycle arrest but also by triggering mitochondria-controlled death of melanoma cancer cells (Figure 2) [4, 25, 28, 225, 228].

The growth regulator amphiregulin AREG is a pro-cancer late-response SASP/SMS protein component that stimulates proliferation of premalignant epithelial cells, whereas the pro-cancer impacts of hepatocyte and fibroblast growth factors HGF and FGF are due to their stimulatory effects on pancreatic cancer cells migration and tissue invasion (Figure 2) [4, 25, 28, 29, 226, 229, 230]. Such late-response SASP/SMS protein components as the vascular endothelial growth factor VEGF as well as chemokines IL-8, eotaxin and I-309 stimulate the migration and tissue invasion of endothelial cells - thereby promoting tumor-associated angiogenesis and facilitating cancer cell invasion and metastasis to distant sites [4, 25, 28, 29, 227, 231–234]. In contrast, the produced by senescent keratinocytes late-response SASP/SMS protein component maspin is a tumor suppressor that slows down angiogenesis by inhibiting the migration of endothelial cells (Figure 2) [4, 28, 235, 236].

Matrix metalloproteinases MMP-1, -2, -3, -10, -12, -13 and -14 are late-response SASP/SMS protein components that exhibit several antagonistically pleiotropic effects on aging and cancer (either beneficial or detrimental for the health of the organism) in a senescence trigger- and tissue context-dependent manner. By proteolytically degrading the extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins that are secreted by hepatic stellate cells or fibroblasts to form a fibrotic scar after acute liver injury or during skin wound healing (respectively), several MMPs impose an anti-aging effect by resolving the fibrotic mass - thus maintaining tissue integrity by promoting its repair and regeneration (Figure 2) [4, 25, 28, 122, 131, 237]. However, by proteolytically degrading the ECM proteins in other tissue contexts, the MMPs have a detrimental impact on organismal health as they impose: (1) a pro-aging effect by compromising the unique physical, biochemical and biomechanical properties of the tissue surrounding senescent cells and ultimately impairing tissue architecture and function; and (2) a pro-cancer effect by facilitating the migration of tumor cells through the ECM, promoting the invasiveness of tumor cells and ultimately enabling their metastasis to distant sites (Figure 2) [4, 25, 28, 29, 238–246].

Some of the cytokines and chemokines constituting the late-response SASP/SMS (including IL-7, IL-15, CXCL-1, MCP-1 and CSF-1), as well as its HMGB-1 protein component, are able to attract innate immune cells to the tissue surrounding senescent cells and then to activate these immune cells [4, 28–30, 122, 247–254]. By killing and clearing senescent non-cancerous cells, the attracted cells of the innate immune system maintain tissue integrity – and thus impose an anti-aging effect (Figure 2) [4, 26, 29, 30, 122, 251, 252]. However, in some tissue contexts the innate immune cells attracted by cytokines and chemokines can have a pro-aging effect by releasing strong oxidants and tissue-remodelling molecules that disrupt tissue architecture, impair tissue function and deplete stem cell niches [4, 30, 245, 250, 255–257]. Furthermore, by facilitating the phagocytic and cytotoxic elimination of senescent tumor cells, innate immune cells exhibit a potent anti-cancer effect (Figure 2) [4, 29, 30, 247, 249, 251–254].

Some of the late-response SASP/SMS protein components impose a pro-cancer effect because they affect the differentiation status of epithelial cells. MMP-3 can promote tumor growth by disrupting the morphological and functional differentiation of breast epithelial cells (Figure 2) [4, 28, 29, 242–244]. Furthermore, by disrupting clusters of pancreatic breast epithelial cells and causing morphological changes reminiscent of an epithelial-to-mesenchymal cell transition, such late-response SASP/SMS protein components as IL-6, IL-8, MMP-3, HFG and uPAR (a receptor of urokinase plasminogen activator) can stimulate epithelial cell migration and tissue invasion (Figure 2) [28, 29, 31, 242, 258–260].

Conclusions and perspectives

A growing body of evidence supports the view that the complex relationship between mechanisms underlying aging and cancer evolves with organismal chronological age. Significant progress has been made in defining cell-autonomous and cell-nonautonomous mechanisms that in young and adult organisms simultaneously delays aging and suppress tumor formation. Furthermore, it is now well established that the intricate interplay between mechanisms underlying aging and cancer reflects the proliferative history of cells and is impacted by the progression of a cellular senescence program through temporally and spatially separable steps. Recent findings imply that the advancement of the multistep cellular senescence program imposes antagonistically pleiotropic effects on aging and cancer. Mechanisms underlying some of these effects have emerged.

Despite an important conceptual advance in our understanding of the complex interplay between mechanisms underlying aging and cancer, we are still lacking answers to the following fundamentally important questions.

Which of the numerous morphological and functional changes observed in various types of senescent cells in culture and in vivo (Tables 1 and 2) are universal hallmarks of a state of cellular senescence – and, thus, which of these changes can be used as diagnostic biomarkers of cells entered such a state in any tissue? Which of these features of senescent cells are, in contrast, characteristic only of a certain senescence trigger, mode of cellular senescence or tissue? The use of genome-wide expression analyses and/or antibody arrays designed to detect various SASP/SMS protein components could facilitate the identification of both universal and tissue-specific senescence biomarkers.

Given that the progression of the cellular senescence program through temporally and spatially separable steps imposes antagonistically pleiotropic effects on aging and cancer (Figures 1 and 2), what therapeutic interventions have a potential to be used not only for enhancing those effects that are anti-aging and/or anti-cancer but also for attenuating those effects that are pro-aging and/or pro-cancer? Recent findings in mice engineered for a reversal of the cellular senescence state by a drug-inducible telomerase reactivation [261] or for a late-life immune clearance of senescent cells by their drug-inducible elimination [262] suggest that small chemicals can be used for: (1) a protein target-specific pharmacological enhancement of the beneficial for organismal healthspan effects imposed by the cellular senescence program; and/or (2) a protein target-specific pharmacological attenuation of the deleterious for organismal healthspan effects inflicted by this program [5, 7, 8, 22–24].

Another attractive direction for future research is a temporal separation of the exogenously accelerated progression of the cellular senescence program from the pharmacologically triggered attenuation of its SASP/SMS at an advanced stage of SASP/SMS development – thereby limiting chronic inflammation, enabling tissue repair and stimulating a targeted immune clearance of those senescent cells that have developed a harmful for organismal health version of this extracellular molecular signature [5, 7, 8, 22–24, 167].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to current and former members of the Titorenko laboratory for discussions. This study was supported by grants from the NSERC of Canada and Concordia University Chair Fund. V.I.T. is a Concordia University Research Chair in Genomics, Cell Biology and Aging.

References

- [1].Finkel T, Serrano M, Blasco MA. The common biology of cancer and ageing. Nature. 2007;448:767–74. doi: 10.1038/nature05985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Serrano M, Blasco MA. Cancer and ageing: convergent and divergent mechanisms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:715–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Adams PD. Healing and hurting: molecular mechanisms, functions, and pathologies of cellular senescence. Mol Cell. 2009;36:2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rodier F, Campisi J. Four faces of cellular senescence. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:547–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Niccoli T, Partridge L. Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R741–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Campisi J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:685–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Blagosklonny MV. Aging and immortality: quasi-programmed senescence and its pharmacologic inhibition. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2087–102. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.18.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Blagosklonny MV, Hall MN. Growth and aging: a common molecular mechanism. Aging. 2009;1:357–62. doi: 10.18632/aging.100040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Campisi J, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:729–40. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Collado M, Blasco MA, Serrano M. Cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Cell. 2007;130:223–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ohtani N, Mann DJ, Hara E. Cellular senescence: its role in tumor suppression and aging. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:792–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hsu YC, Fuchs E. A family business: stem cell progeny join the niche to regulate homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:103–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cheung TH, Rando TA. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:329–40. doi: 10.1038/nrm3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sharpless NE, DePinho RA. How stem cells age and why this makes us grow old. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:703–13. doi: 10.1038/nrm2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Conboy IM, Yousef H, Conboy MJ. Embryonic anti-aging niche. Aging. 2011;3:555–63. doi: 10.18632/aging.100333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Henry CJ, Marusyk A, DeGregori J. Aging-associated changes in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis: what’s the connection? Aging. 2011;3:643–56. doi: 10.18632/aging.100351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jones DL, Rando TA. Emerging models and paradigms for stem cell ageing. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:506–12. doi: 10.1038/ncb0511-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu L, Rando TA. Manifestations and mechanisms of stem cell aging. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:257–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. The essence of senescence. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2463–79. doi: 10.1101/gad.1971610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Seviour EG, Lin SY. The DNA damage response: Balancing the scale between cancer and ageing. Aging. 2010;2:900–7. doi: 10.18632/aging.100248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Blagosklonny MV. Cell cycle arrest is not senescence. Aging. 2011;3:94–101. doi: 10.18632/aging.100281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Campisi J. Cellular senescence: putting the paradoxes in perspective. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Campisi J, Andersen JK, Kapahi P, Melov S. Cellular senescence: A link between cancer and age-related degenerative disease? Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21:354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Collado M, Serrano M. Senescence in tumours: evidence from mice and humans. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:51–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Coppé JP, Desprez PY, Krtolica A, Campisi J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:99–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Davalos AR, Coppé JP, Campisi J, Desprez PY. Senescent cells as a source of inflammatory factors for tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:273–83. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9220-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Freund A, Orjalo AV, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:238–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Muñoz DP, Goldstein J, Nelson PS, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kuilman T, Peeper DS. Senescence-messaging secretome: SMS-ing cellular stress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Vaughan S, Jat PS. Deciphering the role of Nuclear Factor-κB in cellular senescence. Aging. 2011;3:913–9. doi: 10.18632/aging.100390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zender L, Rudolph KL. Keeping your senescent cells under control. Aging. 2009;1:438–41. doi: 10.18632/aging.100046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Jun JI, Lau LF. Cellular senescence controls fibrosis in wound healing. Aging. 2010;2:627–31. doi: 10.18632/aging.100201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lewis DA, Travers JB, Machado C, Somani AK, Spandau DF. Reversing the aging stromal phenotype prevents carcinoma initiation. Aging. 2011;3:407–16. doi: 10.18632/aging.100318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lisanti MP, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Pestell RG, Howell A, Sotgia F. Hydrogen peroxide fuels aging, inflammation, cancer metabolism and metastasis: the seed and soil also needs “fertilizer”. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2440–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.15.16870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lisanti MP, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Pestell RG, Howell A, Sotgia F. Accelerated aging in the tumor microenvironment: connecting aging, inflammation and cancer metabolism with personalized medicine. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2059–63. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.13.16233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ertel A, Tsirigos A, Whitaker-Menezes D, Birbe RC, Pavlides S, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pestell RG, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Is cancer a metabolic rebellion against host aging? In the quest for immortality, tumor cells try to save themselves by boosting mitochondrial metabolism. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:253–63. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.2.19006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pavlides S, Vera I, Gandara R, Sneddon S, Pestell RG, Mercier I, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Whitaker-Menezes D, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Warburg meets autophagy: cancer-associated fibroblasts accelerate tumor growth and metastasis via oxidative stress, mitophagy, and aerobic glycolysis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:1264–84. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Salem AF, Whitaker-Menezes D, Lin Z, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Tanowitz HB, Al-Zoubi MS, Howell A, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Two-compartment tumor metabolism: autophagy in the tumor microenvironment and oxidative mitochondrial metabolism (OXPHOS) in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2545–56. doi: 10.4161/cc.20920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sotgia F, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Howell A, Pestell RG, Pavlides S, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 and Cancer Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment: Markers, Models, and Mechanisms. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:423–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-120856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Madar S, Goldstein I, Rotter V. ‘Cancer associated fibroblasts’ - more than meets the eye. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:447–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chappell WH, Steelman LS, Long JM, Kempf RC, Abrams SL, Franklin RA, Bäsecke J, Stivala F, Donia M, Fagone P, Malaponte G, Mazzarino MC, Nicoletti F, Libra M, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Mijatovic S, Montalto G, Cervello M, Laidler P, Milella M, Tafuri A, Bonati A, Evangelisti C, Cocco L, Martelli AM, McCubrey JA. Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR inhibitors: rationale and importance to inhibiting these pathways in human health. Oncotarget. 2011;2:135–64. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Kempf RC, Long J, Laidler P, Mijatovic S, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Stivala F, Mazzarino MC, Donia M, Fagone P, Malaponte G, Nicoletti F, Libra M, Milella M, Tafuri A, Bonati A, Bäsecke J, Cocco L, Evangelisti C, Martelli AM, Montalto G, Cervello M, McCubrey JA. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathways in controlling growth and sensitivity to therapy-implications for cancer and aging. Aging. 2011;3:192–222. doi: 10.18632/aging.100296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Blagosklonny MV. Selective anti-cancer agents as anti-aging drugs. Cancer Biol Ther. 2013;14:12–17. doi: 10.4161/cbt.27350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lee JH, Bodmer R, Bier E, Karin M. Sestrins at the crossroad between stress and aging. Aging. 2010;2:369–74. doi: 10.18632/aging.100157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Efeyan A, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Amino acids and mTORC1: from lysosomes to disease. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:524–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:283–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cornu M, Albert V, Hall MN. mTOR in aging, metabolism, and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lee JH, Budanov AV, Karin M. Sestrins orchestrate cellular metabolism to attenuate aging. Cell Metab. 2013;18:792–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Shaw RJ. LKB1 and AMP-activated protein kinase control of mTOR signalling and growth. Acta Physiol. 2009;196:65–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Anisimov VN, Zabezhinski MA, Popovich IG, Piskunova TS, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML, Yurova MN, Antoch MP, Blagosklonny MV. Rapamycin extends maximal lifespan in cancer-prone mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2092–7. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008;7:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Bayley JP, Devilee P. Warburg tumours and the mechanisms of mitochondrial tumour suppressor genes. Barking up the right tree? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:324–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kroemer G, Mariño G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell. 2010;40:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Turcotte S, Giaccia AJ. Targeting cancer cells through autophagy for anticancer therapy. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Chen N, Karantza V. Autophagy as a therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:157–68. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.2.14622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Fleming A, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Rubinsztein DC. Chemical modulators of autophagy as biological probes and potential therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Vander Heiden MG. Targeting cancer metabolism: a therapeutic window opens. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:671–84. doi: 10.1038/nrd3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Yang ZJ, Chee CE, Huang S, Sinicrope FA. The role of autophagy in cancer: therapeutic implications. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1533–41. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Cheong H, Lu C, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. Therapeutic targets in cancer cell metabolism and autophagy. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:671–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Johnson RF, Perkins ND. Nuclear factor-κB, p53, and mitochondria: regulation of cellular metabolism and the Warburg effect. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:317–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Liu EY, Ryan KM. Autophagy and cancer - issues we need to digest. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:2349–58. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Muñoz-Pinedo C, El Mjiyad N, Ricci JE. Cancer metabolism: current perspectives and future directions. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e248. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Santos CR, Schulze A. Lipid metabolism in cancer. FEBS J. 2012;279:2610–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Schulze A, Harris AL. How cancer metabolism is tuned for proliferation and vulnerable to disruption. Nature. 2012;491:364–73. doi: 10.1038/nature11706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even Warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Vander Heiden MG, Kroemer G. Metabolic targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:829–46. doi: 10.1038/nrd4145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:931–47. doi: 10.1038/nrd4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Maes H, Rubio N, Garg AD, Agostinis P. Autophagy: shaping the tumor microenvironment and therapeutic response. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:428–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Sui X, Chen R, Wang Z, Huang Z, Kong N, Zhang M, Han W, Lou F, Yang J, Zhang Q, Wang X, He C, Pan H. Autophagy and chemotherapy resistance: a promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e838. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Hursting SD, Lavigne JA, Berrigan D, Perkins SN, Barrett JC. Calorie restriction, aging, and cancer prevention: mechanisms of action and applicability to humans. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:131–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Mai V, Colbert LH, Berrigan D, Perkins SN, Pfeiffer R, Lavigne JA, Lanza E, Haines DC, Schatzkin A, Hursting SD. Calorie restriction and diet composition modulate spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis in Apc(Min) mice through different mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1752–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Raffaghello L, Lee C, Safdie FM, Wei M, Madia F, Bianchi G, Longo VD. Starvation-dependent differential stress resistance protects normal but not cancer cells against high-dose chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8215–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708100105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Blagosklonny MV. TOR-driven aging: speeding car without brakes. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:4055–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.24.10310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, Kastman EK, Kosmatka KJ, Beasley TM, Allison DB, Cruzen C, Simmons HA, Kemnitz JW, Weindruch R. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science. 2009;325:201–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1173635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Anisimov VN. Metformin for aging and cancer prevention. Aging. 2010;2:760–74. doi: 10.18632/aging.100230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span - from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Hursting SD, Smith SM, Lashinger LM, Harvey AE, Perkins SN. Calories and carcinogenesis: lessons learned from 30 years of calorie restriction research. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:83–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Longo VD, Fontana L. Calorie restriction and cancer prevention: metabolic and molecular mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Ben-Porath I, Weinberg RA. The signals and pathways activating cellular senescence. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:961–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Serrano M, Lee H, Chin L, Cordon-Cardo C, Beach D, DePinho RA. Role of the INK4a locus in tumor suppression and cell mortality. Cell. 1996;85:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Krishnamurthy J, Torrice C, Ramsey MR, Kovalev GI, Al-Regaiey K, Su L, Sharpless NE. Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1299–307. doi: 10.1172/JCI22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Sharpless NE. Ink4a/Arf links senescence and aging. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1751–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Passos JF, Simillion C, Hallinan J, Wipat A, von Zglinicki T. Cellular senescence: unravelling complexity. Age. 2009;31:353–363. doi: 10.1007/s11357-009-9108-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Donate LE, Blasco MA. Telomeres in cancer and ageing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366:76–84. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Ditch S, Paull TT. The ATM protein kinase and cellular redox signaling: beyond the DNA damage response. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Reinhardt HC, Schumacher B. The p53 network: cellular and systemic DNA damage responses in aging and cancer. Trends Genet. 2012;28:128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Sahin E, DePinho RA. Axis of ageing: telomeres, p53 and mitochondria. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:397–404. doi: 10.1038/nrm3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Hardie DG, Alessi DR. LKB1 and AMPK and the cancer-metabolism link - ten years after. BMC Biol. 2013;11:36. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Shiloh Y, Ziv Y. The ATM protein kinase: regulating the cellular response to genotoxic stress, and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:197–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Di Leonardo A, Linke SP, Clarkin K, Wahl GM. DNA damage triggers a prolonged p53-dependent G1 arrest and long-term induction of Cip1 in normal human fibroblasts. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2540–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Ogryzko VV, Hirai TH, Russanova VR, Barbie DA, Howard BH. Human fibroblast commitment to a senescence-like state in response to histone deacetylase inhibitors is cell cycle dependent. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5210–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Lin AW, Barradas M, Stone JC, van Aelst L, Serrano M, Lowe SW. Premature senescence involving p53 and p16 is activated in response to constitutive MEK/MAPK mitogenic signaling. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3008–19. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Zhu J, Woods D, McMahon M, Bishop JM. Senescence of human fibroblasts induced by oncogenic Raf. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2997–3007. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Dimri GP, Itahana K, Acosta M, Campisi J. Regulation of a senescence checkpoint response by the E2F1 transcription factor and p14(ARF) tumor suppressor. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:273–85. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.273-285.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Pearson M, Carbone R, Sebastiani C, Cioce M, Fagioli M, Saito S, Higashimoto Y, Appella E, Minucci S, Pandolfi PP, Pelicci PG. PML regulates p53 acetylation and premature senescence induced by oncogenic Ras. Nature. 2000;406:207–10. doi: 10.1038/35018127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Blander G, de Oliveira RM, Conboy CM, Haigis M, Guarente L. Superoxide dismutase 1 knock-down induces senescence in human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38966–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Parrinello S, Samper E, Krtolica A, Goldstein J, Melov S, Campisi J. Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:741–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Munro J, Barr NI, Ireland H, Morrison V, Parkinson EK. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce a senescence-like state in human cells by a p16-dependent mechanism that is independent of a mitotic clock. Exp Cell Res. 2004;295:525–38. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:483–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Lombard DB, Chua KF, Mostoslavsky R, Franco S, Gostissa M, Alt FW. DNA repair, genome stability, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:497–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Soengas MS, Denoyelle C, Kuilman T, van der Horst CM, Majoor DM, Shay JW, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436:720–4. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Braig M, Schmitt CA. Oncogene-induced senescence: putting the brakes on tumor development. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2881–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].d’Adda di Fagagna F. Living on a break: cellular senescence as a DNA-damage response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:512–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Bhaumik D, Scott GK, Schokrpur S, Patil CK, Orjalo AV, Rodier F, Lithgow GJ, Campisi J. MicroRNAs miR-146a/b negatively modulate the senescence-associated inflammatory mediators IL-6 and IL-8. Aging. 2009;1:402–11. doi: 10.18632/aging.100042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Marasa BS, Srikantan S, Martindale JL, Kim MM, Lee EK, Gorospe M, Abdelmohsen K. MicroRNA profiling in human diploid fibroblasts uncovers miR-519 role in replicative senescence. Aging. 2010;2:333–43. doi: 10.18632/aging.100159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Narita M. Quality and quantity control of proteins in senescence. Aging. 2010;2:311–4. doi: 10.18632/aging.100145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Young AR, Narita M. Connecting autophagy to senescence in pathophysiology. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Hoare M, Young AR, Narita M. Autophagy in cancer: Having your cake and eating it. Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Parsons DW, Wang TL, Samuels Y, Bardelli A, Cummins JM, DeLong L, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, Willson JK, Markowitz S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C, Velculescu VE. Colorectal cancer: mutations in a signalling pathway. Nature. 2005;436:792. doi: 10.1038/436792a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Sebastian T, Malik R, Thomas S, Sage J, Johnson PF. C/EBPbeta cooperates with RB:E2F to implement Ras(V12)-induced cellular senescence. EMBO J. 2005;24:3301–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:961–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Acosta JC, O’Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, Fumagalli M, Da Costa M, Brown C, Popov N, Takatsu Y, Melamed J, d’Adda di Fagagna F, Bernard D, Hernando E, Gil J. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell. 2008;133:1006–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Fridman AL, Tainsky MA. Critical pathways in cellular senescence and immortalization revealed by gene expression profiling. Oncogene. 2008;27:5975–87. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Krizhanovsky V, Xue W, Zender L, Yon M, Hernando E, Lowe SW. Implications of cellular senescence in tissue damage response, tumor suppression, and stem cell biology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:513–22. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Douma S, van Doorn R, Desmet CJ, Aarden LA, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell. 2008;133:1019–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Caino MC, Meshki J, Kazanietz MG. Hallmarks for senescence in carcinogenesis: novel signaling players. Apoptosis. 2009;14:392–408. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0316-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Gamerdinger M, Hajieva P, Kaya AM, Wolfrum U, Hartl FU, Behl C. Protein quality control during aging involves recruitment of the macroautophagy pathway by BAG3. EMBO J. 2009;28:889–901. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Haferkamp S, Tran SL, Becker TM, Scurr LL, Kefford RF, Rizos H. The relative contributions of the p53 and pRb pathways in oncogene-induced melanocyte senescence. Aging. 2009;1:542–56. doi: 10.18632/aging.100051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Maclaine NJ, Hupp TR. The regulation of p53 by phosphorylation: a model for how distinct signals integrate into the p53 pathway. Aging. 2009;1:490–502. doi: 10.18632/aging.100047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Muller M. Cellular senescence: molecular mechanisms, in vivo significance, and redox considerations. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:59–98. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].de Keizer PL, Laberge RM, Campisi J. p53: Pro-aging or pro-longevity? Aging. 2010;2:377–95. doi: 10.18632/aging.100178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. TP53 and mTOR crosstalk to regulate cellular senescence. Aging. 2010;2:535–7. doi: 10.18632/aging.100202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Jun JI, Lau LF. The matricellular protein CCN1 induces fibroblast senescence and restricts fibrosis in cutaneous wound healing. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:676–85. doi: 10.1038/ncb2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Korotchkina LG, Leontieva OV, Bukreeva EI, Demidenko ZN, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. The choice between p53-induced senescence and quiescence is determined in part by the mTOR pathway. Aging. 2010;2:344–52. doi: 10.18632/aging.100160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Leontieva OV, Blagosklonny MV. DNA damaging agents and p53 do not cause senescence in quiescent cells, while consecutive re-activation of mTOR is associated with conversion to senescence. Aging. 2010;2:924–35. doi: 10.18632/aging.100265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Mallette FA, Calabrese V, Ilangumaran S, Ferbeyre G. SOCS1, a novel interaction partner of p53 controlling oncogene-induced senescence. Aging. 2010;2:445–52. doi: 10.18632/aging.100163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Odell A, Askham J, Whibley C, Hollstein M. How to become immortal: let MEFs count the ways. Aging. 2010;2:160–5. doi: 10.18632/aging.100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Poyurovsky MV, Prives C. P53 and aging: A fresh look at an old paradigm. Aging. 2010;2:380–2. doi: 10.18632/aging.100179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Vergel M, Carnero A. Bypassing cellular senescence by genetic screening tools. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010;12:410–7. doi: 10.1007/s12094-010-0528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]