The US Preventive Services Task Force, several federal agencies, and others recommend that primary care providers conduct systematic tobacco, alcohol and depression screening and intervention1–8 – henceforth, behavioral screening and intervention, or BSI. Such services are receiving increasing attention, because annual economic loss from tobacco use, alcohol use, and depression exceeds $500 billion,9,10 and because four dollars are saved in one year for every dollar spent on alcohol services,8 $6.50 in four years for depression services,11 and likely more for tobacco services.12

BSI starts with a few screening questions to identify patients who likely have behavioral risks or disorders.1 Positive screens require further assessment, which guides further service delivery as per prior research. Low-risk drinkers or tobacco and alcohol abstainers receive reinforcement. Tobacco users and high-risk drinkers receive on-site interventions and ongoing support. Nicotine-dependent patients are offered pharmacotherapy. Patients with possible alcohol dependence, and patients with desire but inability to modify tobacco or alcohol use, are referred for specialty care or other resources. In addition to usual pharmacotherapy and/or counseling, depressed patients receive collaborative care, in which typically a nurse or mental health professional tracks depression symptom scores, coordinates management, and promotes patient engagement in treatment during and in between visits.13 Collaborative care can also include behavioral activation, in which patients are engaged in behaviors that ameliorate depression symptoms, such as exercising and socializing.14

Two major sets of barriers impede BSI implementation. Financial barriers are waning, as fee-for-service reimbursement for BSI is expanding under the Affordable Care Act, and shared savings models are taking hold. A more stubborn barrier is staff time. A primary care clinician would need 7.4 hours every workday to deliver all recommended preventive services, including BSI, leaving little time to address acute concerns and chronic illness.15 Especially with a growing primary care provider shortage, conventionally configured primary care practices will be unable to systematically deliver BSI.

The Wisconsin Initiative to Promote Healthy Lifestyles (WIPHL) was established to promote the delivery of BSI in healthcare settings throughout Wisconsin. In a demonstration project between 2006 and 2011, WIPHL helped 33 clinical sites deliver BSI for alcohol and drugs by expanding their healthcare teams with trained and supported “health educators.” Three sites delivered depression BSI for a short period of time. This paper reports on patient satisfaction and pre/post-intervention changes in behavioral outcomes at those sites.

Methods

Administration

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services received funding and direction from the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), administered the project, contracted with the University of Wisconsin (UW) School of Medicine and Public Health and the Wisconsin Medical Society to administer a Coordinating Center, and contracted with the UW Population Health Institute to conduct program evaluation.

Sites

The Coordinating Center recruited sites through networking and selected them for their diversity in geographic location, population density (urban, suburban, and rural), payer mix, and their readiness to take advantage of the program. Sites were launched in waves to fill eighteen slots. Additional sites were recruited as vacancies occurred. Initially only primary care clinics were recruited. In later years, an emergency department and a hospital were added.

Site Preparation and Support

Interested sites completed a checklist to assess readiness and guide preparations. Sites instituted annual, universal screening for their entire patient population or for a subpopulation defined by provider or visit purpose. In most sites, receptionists distributed brief screening questionnaires. Sites were encouraged to include questions on multiple behavioral risks, in part to enhance acceptance of alcohol and drug questions.16 Staff members who checked vital signs reviewed questionnaire responses and referred patients with positive alcohol or drug screens to health educators. Consistent with SAMHSA requirements, health educators primarily conducted alcohol and drug assessment, then education, intervention, or referral as appropriate; they provided brief feedback and referral for other behavioral risks. They reported back to providers, who were encouraged to provide additional support and pharmacotherapy.

Sites were encouraged initially to identify champions, establish a quality improvement (QI) team with representatives from various staff segments, and design an initial workflow. The Coordinating Center provided consultation on best practices. Sites were encouraged to engage in monthly plan-do-study-act cycles to optimize two metrics: (1) the proportion of eligible patients who completed screens and (2) the proportion of patients with positive alcohol or drug screens who completed health educator-administered brief assessments.

Health Educator Hiring

The Coordinating Center guided each clinical site in hiring a health educator – a term that carries no legal implications in Wisconsin. Of the 44 health educators hired, nine were masters-level counselors or social workers, 33 others had bachelor’s degrees, and two were high school graduates with special language or cross-cultural skills. Seven health educators had a bachelor’s degree in health education, four were Certified Health Education Specialists, and one was a certified chemical dependency counselor.

Health Educator Training and Support

One week of distance training and a subsequent week of face-to-face training emphasized alcohol and drug screening, brief intervention and referral-to-treatment (SBIRT), motivational interviewing, and cultural competence. Learning activities included interactive lectures, discussions, demonstrations, and role-play exercises, sometimes with standardized patients. Health educators had to pass a written examination and skills performance assessment. At their clinical sites, they received ongoing support through weekly conference calls and quarterly retreats. Monthly, with patients’ written consent, health educators submitted audiotapes of sessions and received structured feedback from trainers, who completed a modified skills checklist.17 Custom software guided health educators in real-time in delivering high-fidelity, evidence-based services. As they saw patients, health educators entered data, which allowed tracking of service delivery.

Clinical protocols

As shown in Table 1, the alcohol and drug screen included three validated questions on substance use5,18 and a direct question about illicit drug use or non-medical use of prescription drugs. Questionnaires were available in several languages.

TABLE 1.

Alcohol, Drug and Depression Screening Questions

| 1. Think of the last time you had more than (men: 4 drinks; women: 3 drinks) in a day or night. Was that within the past three months? |

| 2. In the last year, have you ever drunk alcohol or used drugs more than you meant to? |

| 3. In the last year, have you felt you wanted or needed to cut down on your drinking or drug use? |

| 4. In the last 12 months, did you smoke pot, use another street drug, or use a prescription painkiller, stimulant, or sedative for a non-medical reason? |

| 5. Over the past two weeks, have you been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things? |

| 6. Over the past two weeks, have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? |

For patients with positive screens, health educators administered the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST)19 plus three questions on quantity and frequency of alcohol use.20 Based on their responses, patients’ substance use was classified as low risk, risky, harmful or likely dependent. Health educators asked additional questions as required by SAMHSA and the Governmental Performance Results Act.

For low-risk patients, health educators affirmed and reinforced low-risk behaviors. For patients with harmful or risky use, health educators varied brief interventions in response to severity of risk or disorder, patient preference, and time constraints. Interventions ranged from brief feedback, recommendation and negotiation to full-fledged, open-ended motivational interviewing.21 For likely dependent patients, health educators recommended referral for specialized assessment or treatment. Most referred interested patients to a treatment liaison, based at the Coordinating Center, who gathered additional information by phone, provided encouragement and support, and negotiated referrals considering availability, financing, and patients’ needs and preferences. Grant funds were available to fund treatment for patients without other means.

Program Evaluation

Evaluation included follow-up telephone interviews five to eight months after initial service delivery with a randomly selected sample of patients who received interventions or referrals. The chief purpose of the interviews was to assess for changes in behavior. Questions on substance use were identical to those asked by health educators. Of 1,099 patients eligible to participate, 874 (80%) provided consent, and 675 participated (77% of those consenting).

During the third project year, health educators were asked to distribute “patient satisfaction” surveys to all patients in one month. The surveys consisted of the four-item, task subscale of the Likert-type Working Alliance Inventory,22 which assesses the strength of psychotherapeutic relationships and was adapted for alcohol and drug use. Respondents submitted their responses anonymously.

Depression pilot study

Three clinics with bachelor’s-level health educators delivered BSI for depression in up to 4 sessions per patient. They added the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) depression screen23 (see Table 1) to their written questionnaires. For patients with positive screens, health educators administered the PHQ-9.24 They referred patients with possible suicidality or major depressive episode for further assessment. For patients with PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater, they delivered collaborative care and a protocol-guided behavioral activation intervention. At each subsequent visit, patients responded to the PHQ-9 and anonymously completed a brief satisfaction questionnaire. During 3-month follow-up telephone interviews, research assistants readministered the PHQ-9 and the satisfaction questionnaire.

Human subjects

The University of Wisconsin Human Subjects Committee exempted the larger project from its purview, because it involved service delivery and required federal program evaluation. Nevertheless, health educators informed patients of the risks and benefits of participating, and patients gave written consent to participate in six-month follow-up interviews. The Committee approved the research protocol for the depression study.

Results

Clinical Site Participation

Of 33 participating sites, nine were located in or near Milwaukee, ten in or near cities with populations of 30,000 to 250,000, and fourteen in rural areas. The sites were seventeen large commercial primary care or multispecialty groups, six federally qualified health centers or look-alikes, five independent commercial primary care sites, two tribal health centers, a health department clinic, a hospital-based emergency department, and a hospital trauma center plus other inpatient units. Over 51 months, average duration of participation was 25 months.

Patient participation

Between March 2007 and June 2011, 113,642 patients completed screens. Those screened were 63% female, 58% white and non-Hispanic, 15% Hispanic, 14% black or African-American, 11% Native American, 1% Pacific Islander, and 2% multiple races. Fifteen percent were of ages 18 to 24 years; 23%, 25 to 35 years; 50%, 36 to 64 years; and 12%, 65 years or older.

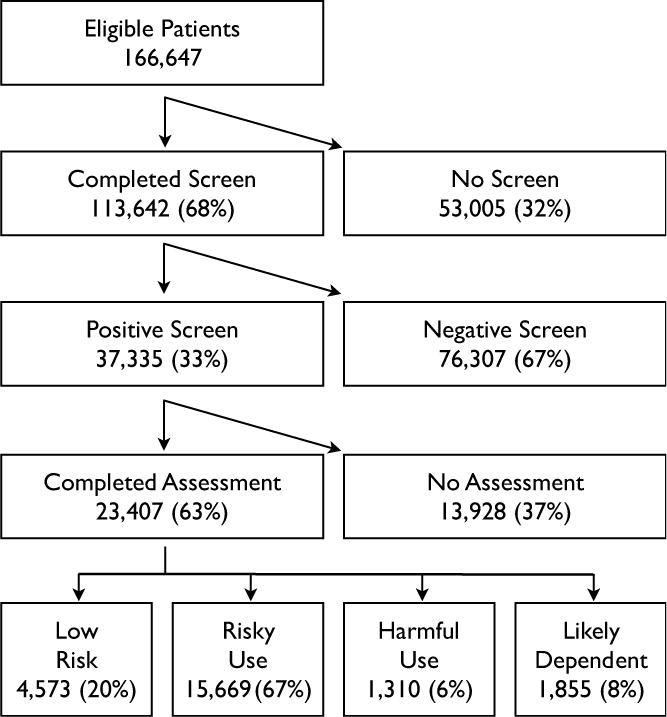

Patient flow

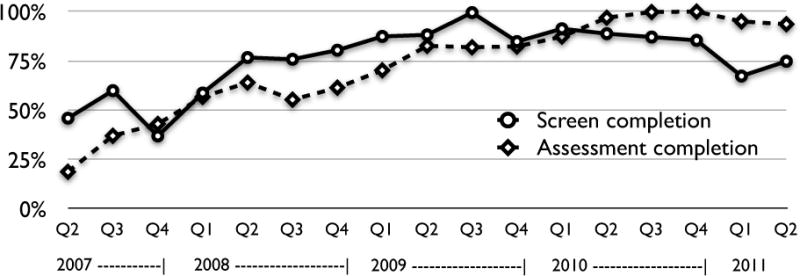

Figure 1 shows the flow of patients through the clinical process, and the final categorization of patients’ substance use. Through the project, 68% of patients who were eligible completed a screen, and 63% of those with positive brief screens saw a health educator and completed a brief assessment. A plot of these metrics over time, as reported by health educators, is shown in Figure 2. A linear regression confirmed significant improvements over time for quarterly completion of screens (p<.001) and assessments (p<.001). Metrics declined toward the end of the project, when new clinics replaced experienced clinics that had become self-sufficient and exited the grant-funded program.

FIGURE 1.

Patient Flow through Screening and Assessment

FIGURE 2. Screen and Assessment Completion Over Time.

“Screen completion” was calculated as (patients who completed alcohol/drug screens)/(patients who were eligible for screening as determined by clinical sites). “Assessment completion” was calculated as (patients who completed health educator-administered brief alcohol/drug assessments)/(patients with positive alcohol/drug screens). Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 refer to 3-month time periods of each year.

Alcohol/drug assessment results

Figure 1 also shows the results of the brief assessments for patients who completed them. Assuming similarity between screened and unscreened patients, and between patients with positive screens who did and did not undergo brief assessment, the estimated population prevalence of abstinence or low-risk use was 73%; risky use, 22%; harmful use 2%; and likely dependence, 3%.

Alcohol/drug intervention and referral services

All patients in the risky and harmful use categories received a brief intervention. All likely dependent patients were encouraged to accept a referral for specialized assessment or treatment. Of the 1,855 likely dependent patients, 452 (24%) expressed initial interest in referral. Health educators’ and the treatment liaison’s records showed that 183 (10%) entered treatment, though data capture might have been incomplete.

Substance Use Outcomes

We compared 675 patients’ initial, face-to-face self-reports to health educators with telephone self-reports provided six months later to evaluation staff. Results are shown in Table 2. Reductions in risky drinking, mean number of drinks per drinking day, and maximal number of drinks over the prior three months exceeded 20% and were consistent across most subgroups. Patients over age 65 years and patients with Medicare had lower base rates and manifested small reductions. Bachelor’s-level health educators elicited greater reductions than those with master’s degrees (p<.05 for all three alcohol measures).

TABLE 2.

Baseline and Six-Month Follow-Up Data on Alcohol Use in the Prior Three Months

| Patients | N | Proportion exceeding low-risk limits | Mean number of drinks on a typical day | Mean maximum number of drinks in a day | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | Relative change | Baseline | 6 months | Relative change | Baseline | 6 months | Relative change | ||

| All | 662 | 86% | 67% | −22%# | 4.06 | 3.27 | −19%# | 7.52 | 5.67 | −25%# |

| By age group | ||||||||||

| 18–24 years old | 122 | 84% | 62% | −25%# | 3.71 | 2.89 | −22%* | 7.25 | 5.48 | −24%† |

| 25–35 years old | 201 | 84% | 68% | −20%# | 4.66 | 3.64 | −22%† | 8.26 | 6.31 | −24%# |

| 36–64 years old | 294 | 86% | 66% | −23%# | 4.09 | 3.33 | −19%# | 7.70 | 5.66 | −26%# |

| ≥65 years old | 45 | 98% | 87% | −11%* | 2.18 | 2.29 | +5% | 3.73 | 3.36 | −10% |

| By gender | ||||||||||

| Females | 388 | 84% | 64% | −24%# | 3.52 | 2.76 | −22%# | 6.33 | 4.61 | −27%# |

| Males | 274 | 88% | 72% | −18%# | 4.82 | 4.00 | −17%† | 9.20 | 7.16 | −22%# |

| By insurance | ||||||||||

| Commercial | 219 | 96% | 77% | −20%# | 3.62 | 3.34 | −8% | 7.84 | 6.16 | −21%# |

| Medicaid | 161 | 71% | 55% | −23%# | 4.10 | 3.01 | −27%# | 6.84 | 4.78 | −30%# |

| Medicare | 51 | 84% | 67% | −21%# | 2.49 | 2.35 | −6% | 4.43 | 3.55 | −20%* |

| None | 142 | 85% | 63% | −26%# | 5.11 | 3.68 | −28%# | 8.85 | 6.32 | −29%# |

| Other/Unknown | 89 | 88% | 73% | −17%† | 4.30 | 3.46 | −20% | 7.60 | 6.22 | −18% |

| By race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Black | 159 | 65% | 48% | −26%# | 3.47 | 2.72 | −22%* | 5.79 | 4.24 | −27%† |

| Native American | 28 | 75% | 54% | −29%† | 6.18 | 4.29 | −31%* | 8.71 | 6.36 | −27%* |

| Other/Unknown | 16 | 100% | 81% | −19% | 5.68 | 3.69 | −35% | 8.75 | 5.63 | −36%* |

| White, Hispanic | 44 | 93% | 55% | −41% | 5.61 | 3.32 | −41%† | 8.84 | 5.43 | −39%# |

| White, non-Hisp. | 415 | 93% | 76% | −18%# | 3.92 | 3.40 | −13%† | 7.91 | 6.20 | −22%# |

| By HE degree | ||||||||||

| Bachelor’s | 456 | 87% | 66% | −24%# | 4.23 | 3.30 | −22%# | 7.64 | 5.58 | −27%# |

| Master’s | 206 | 83% | 70% | −16%# | 3.70 | 3.21 | −13%* | 7.26 | 5.85 | −19%# |

HE = health educator

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Among those who screened positive for substance use, reports of past three-month marijuana use declined from 28% at baseline to 23% at follow-up (p<.001). Reports of past 30-day marijuana use declined from 23% to 19% (p<.001). The low rates of other drug use precluded assessments of intervention effectiveness.

Accuracy of self-report

To assess for possible differences in the accuracy of self-reports of substance use to health educators at baseline and to evaluators at six-month follow-up, we compared self-reports of lifetime substance use. Seven (1%) of 673 patients who provided complete information gave disparate reports of lifetime alcohol use. Four reported use only to the evaluator only and three only to the health educator. Of the 128 with disparate reports of marijuana use, 85 (66%) reported use only to the evaluator, and 43 (34%) only to the health educator (p<.0001). Of the 79 with disparate reports of cocaine use, 64 (68%) reported use only to the evaluator, and 25 (32%) only to the health educator (p<.001).

Patient Satisfaction

In year 3 of the project, 346 patients rated each of the four adapted Working Alliance Inventory task subscale items on a one-to-five integer scale.22 Higher scores indicated stronger therapeutic relationships between patients and health educators. Mean scores for each item ranged from 4.24 to 4.45.

Depression Pilot Study

At three clinics, 1,356 patients underwent screening; 300 (22%) had a positive PHQ-2 screen, 158 (53% of those with positive screens) completed a PHQ-9, 68 (43% of respondents) had PHQ-9 scores of 10 or greater, and 29 patients (43% of those eligible) consented to participate. Participant age ranged from 20 to 68 years, with a median of 41 years. About three-fourths (76%) of participants were female, and 97% were white. Five (17%) of the participants were newly diagnosed with depression.

Twenty-two (76%) of the 29 subjects participated in the three-month follow-up phone interview. Over 8 to 12 weeks, those patients had 2 to 4 sessions with their health educators. At patients’ last visits, mean satisfaction scores were 4.9; at three-month follow-up, 4.4. Patients reported to health educators they especially appreciated learning how to help themselves with their depression. Mean PHQ-9 scores declined by 55%, from 17.1 to 7.7 (p<.0001). Those patients already being treated for depression had no change in medication regimens through the study period. Thirteen (59%) of 22 patients met successful treatment outcome criteria – PHQ-9 score reductions of 5 points, and final scores of less than 10.25

DISCUSSION

This paper reports on patient satisfaction and behavioral outcomes for a large demonstration project aiming to expand delivery of evidence-based, cost-saving alcohol and drug screening and intervention services in healthcare settings throughout Wisconsin, chiefly in primary care settings. A pilot study also assessed the feasibility of integrating screening and collaborative care for depression into alcohol and drug services. Key features of the project were involvement of diverse healthcare sites; evidence-based screening and assessment instruments and protocols; service delivery by full-time, dedicated, rigorously trained, supported, and computer-guided service delivery, and a quality improvement framework to optimize workflow.

The large proportion of positive alcohol and drug screens and assessments demonstrated need for the services. Responses to four items of the Working Alliance Inventory indicated patient satisfaction with BSI as delivered by the health educators.

Sites delivering BSI must attend to workflow issues, because failure to deliver appropriate services to patients with positive screens or assessments could engender poor outcomes and medicolegal risk. Across all sites over time, there was substantial gain in the proportion of eligible patients who completed screens and assessments. Improvements came as some sites learned through quality improvement cycles, as successful sites could serve as models for other sites, as less effective sites were replaced with more effective ones, and as the Coordinating Center more effectively promoted best practices, recruited suitable sites, and better prepared them to participate.

The 20% decline in risky drinking found at 6-month follow-up is typical of prior controlled studies and has been associated with reductions of 20% in emergency department visits, 37% in hospitalizations, 46% in arrests, and 50% in vehicular crashes.8 Since WIPHL attained greater than 20% declines in risky drinking in most subgroups, WIPHL likely had substantial favorable impacts on health outcomes, costs, and public safety. Analysis of impacts on healthcare costs is in progress.

A potential limitation of our findings is the sole use of self-report to measure changes in substance use. The limitation is mitigated by ample prior literature showing the validity of self-report and this project’s finding that self-report of substance use was greater during confidential follow-up interviews with evaluators than during initial assessment face-to-face interviews with health educators. Thus patients’ decreases in substance use may have been underestimated.

A retrospective analysis suggested that bachelor’s-level health educators elicited greater reductions in risky drinking than their master’s-level counterparts, though confounding factors cannot be ruled out. If the finding is valid, possible reasons, observed informally, are that individuals without prior clinical experience can more easily learn motivational interviewing and deliver it with greater fidelity, and that master’s-level individuals were dissatisfied to follow protocols intended to elicit behavior change rather than deliver broader counseling services.

A concerning finding was that alcohol interventions were less effective for elderly patients than younger patients. One reason that few risky drinkers became low-risk drinkers might have been the use of a stringent definition of risky drinking for elders – no more than one drink per day.26 Nonetheless, the potency of alcohol interventions for the elderly might be improved with specialized intervention protocols that address common, alcohol-related health risks.27

Another concerning finding was the low proportion of substance-dependent patients that were documented to have started treatment. Barriers to effective alcohol and drug treatment referrals are well-known.28 Perhaps offering a non-abstinence based treatment approach and/or pharmacotherapy in primary care settings would better serve many dependent patients who do not obtain specialized treatment.

In a small pilot study, three clinics and their bachelor’s-level health educators without prior mental health experience delivered collaborative care and behavioral activation services to depressed patients. Services were effective for patients whose depression was under treatment or newly recognized. Patients indicated satisfaction with the services, and there was a 55% reduction in depression symptom scores over eight to twelve weeks. In most prior studies, behavioral activation and collaborative care were delivered by nurses or mental health professionals.13 This study suggests that primary care settings can deliver effective alcohol, drug, and depression screening services by expanding their teams with trained and protocol-guided, bachelors-level paraprofessionals.

Prior studies suggest that initial written behavioral screens, subsequent brief counseling, and referral to known resources are best practices for delivering behavioral screening and intervention in primary care settings.29 This study’s findings are consistent with that prior research and suggest further that expanding primary care teams with dedicated, protocol-guided bachelor’s-level paraprofessionals could allow delivery of universal BSI for a variety of behavioral risks and conditions, improve health outcomes, and reduce net healthcare costs.30

Takeaway points.

This article describes a program that successfully delivers evidence-based, cost-saving alcohol, drug, and depression screening and intervention services in primary care settings.

Ample research has documented the effectiveness of these services and their return on investment, yet they are seldom delivered, largely because of provider and staff time pressures.

Trained and supported, cost-efficient paraprofessionals can deliver these services, elicit high patient satisfaction, and attain substantial declines in risky drinking, illicit drug use, and depressive symptoms.

Over time, clinical settings were able to modify workflow so that most patients received recommended services.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This project was funded by US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration grant TI-18309, and by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Brown owns Wellsys, LLC, which offers healthcare settings assistance in implementing behavioral screening and intervention. Ms. Croyle and Ms. Saunders are Wellsys employees.

References

- 1.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendations. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm.

- 2.Fiore M, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Bethesda, MD: Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sebelius K. US Department of Health and Human Services Strategic Plan; Fiscal Years 2010 – 2015. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Accessed at http://www.hhs.gov/secretary/about/priorities/strategicplan2010–2015.pdf on February 16, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin R. The national prevention and health promotion strategy, draft framework. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General; 2010. Accessed at http://www.healthcare.gov/prevention/nphpphc/strategy/report.pdf on February 16, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much; A Clinician’s Guide, updated 2005 edition. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2007. (NIH Publication No. 07-3769). Accessed at http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf on February 16, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office of National Drug Control Strategy. National Drug Control Strategy; 2011. Washington, DC: Office of National Drug Control Strategy; 2011. Accessed at http://www.whitehouse.gov/ondcp/national-drug-control-strategy on February 26, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Screening works: update from the field. SAMHSA News 2008. 2008;16(2) Accessed at http://www.samhsa.gov/samhsa_news/volumexvi_2/article2.htm on February 16, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Business Group on Health. Moving Science Into Coverage: An Employer’s Guide to Preventive Services. Alcohol misuse (screening and counseling), updated 1/31/11. Accessed at http://www.businessgrouphealth.org/preventive/topics/alcohol_misuse.cfm on February 16, 2012.

- 9.National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Shoveling Up II: The Impact of Substance Abuse on Federal, State and Local Budgets. New York: National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse; 2009. Accessed at http://www.casacolumbia.org/articlefiles/380-ShovelingUpII.pdf on February 12, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States; how did it change between 1990 and 2000? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64:1465–75. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unutzer J, Schoenbaum M, Harbin H. Collaborative Care for Primary/Co-Morbid Mental Disorders; Brief for CMS Meeting; updated August 4, 2011. Accessed at http://uwaims.org/integrationroadmap/docs/CMS_Brief_on_Collaborative_Care_4Aug11.pdf on February 12, 2012.

- 12.Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, et al. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders; a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yarnall KSH, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: Is there enough time for prevention? American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:635–641. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming MF, Barry KL. A three-sample test of a masked alcohol screening questionnaire. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1991;26:81–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierson HM, Hayes SC, Gifford EV, et al. An examination of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown RL, Leonard T, Saunders LA, Papasouliotis O. A two-item conjoint screen for alcohol and other drug problems. Criterion validity for a split sample. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2001;14:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humeniuk RE, Ali RA, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103:1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedmann PD, Saitz R, Gogineni A, Zhang JX, Stein MD. Validation of the screening strategy in the NIAAA “Physicians’ Guide to Helping Patients with Alcohol Problems”. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:234–238. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change, second edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatcher RL, Gillaspy J. Development and validation of a revised short version of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychotherapy Research. 2006;16:12–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression: Two questions are as good as many. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12:439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Medical Care. 2004;42:1194–1201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMillan D, Gilbody S, Richard D. Defining successful treatment outcome in depression using the PHQ-9: a comparison of methods. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;127:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients with alcohol problems; a health practitioner’s guide. Rockville, Maryland: NIAAA; 2004. (NIH Publication 04-3769). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore AA, Blow FC, Hoffing M, et al. Primary care-based intervention to reduce at-risk drinking in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2010;106:111–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2010 Accessed at http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k10NSDUH/2k10Results.htm#7.3 on February 16, 2012. [PubMed]

- 29.Cohen DJ, Balasubramanian BA, Isaacson NF, Clark EC, Etz RS, Crabtree BF. Coordination of health behavior counseling in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine. 2011;9:406–415. doi: 10.1370/afm.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown RL. Configuring health care for systematic behavioral screening and intervention. Population Health Management. 2011;14:299–305. doi: 10.1089/pop.2010.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]