Abstract

Background

A substantial number of young women experience pregnancy scares – thinking they might be pregnant, and later discovering that they are not. Although pregnancy scares are distressing events, little is known about who experiences them and whether they are important to our understanding of unintended pregnancy.

Objective

We describe the young women who experience pregnancy scares, and examine the link between pregnancy scares and subsequent unintended pregnancy.

Methods

We used data from the Relationship Dynamics and Social Life Study. T-tests and regression analyses were conducted using baseline and weekly data to estimate relationships between respondent characteristics and subsequent pregnancy scares. Event history methods were used to assess pregnancy scares as a predictor of unintended pregnancy.

Results

Nine percent of the young women experienced a pregnancy scare during the study. African-American race, lack of two-parent family structure, lower GPA, cohabitation, and sex without birth control prior to the study are associated with experiencing a pregnancy scare and with experiencing a greater number of pregnancy scares. Further, experiencing a pregnancy scare is strongly associated with subsequent unintended pregnancy, independent of background factors. Forty percent of the women who experienced a pregnancy scare subsequently had an unintended pregnancy during the study period, relative to only 11% of those who did not experience a pregnancy scare.

Conclusions

Young women from less advantaged backgrounds are more likely to experience a pregnancy scare, and pregnancy scares are often followed by an unintended pregnancy.

1. Introduction

In the United States, the term ‘pregnancy scare’ describes when a woman who wants to avoid pregnancy believes she is pregnant, but later learns that she is not. For example, as one respondent (who did not desire a pregnancy) told us shortly after her pregnancy scare, “I thought there could have been a chance that I was pregnant but it turned out that I wasn't, so I am very thankful for that.” Many respondents reported, “I missed this month's period,” or “My period started seven days late” to explain why they temporarily thought they were pregnant.

Pregnancy scares are common – over half of the young women (54%) who participated in a recent survey conducted by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy (2011) reported that they had had a pregnancy scare. In the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation's National Survey of Adolescents and Young Adults, 3 in 5 respondents reported that they or their female partner had ever experienced a pregnancy scare (Hoff, Greene, and Davis 2003). Relatively little is known about pregnancy scares and their consequences.

Our first objective is to describe the young women who experience pregnancy scares. We hypothesize that disadvantaged sociodemographic background characteristics and early experiences with sex, lack of contraception, and pregnancy will be associated with pregnancy scares, much as they are associated with unintended pregnancy.

Our second objective is to examine the link between pregnancy scares and subsequent unintended pregnancy. A pregnancy scare may be an indicator that a young woman is at high risk of an unintended pregnancy, for several reasons. First, adjustment to the idea of a possible pregnancy might introduce some ambivalence into a young woman's desire to avoid pregnancy. This can occur after a miscarriage of an unintended pregnancy. As one respondent told us, “I found out I was pregnant and I miscarried. I didn't know that I wanted a baby until I lost it. That is why part of me wants to get pregnant now. I'm not trying to but I would be happy if I did.” If pregnancy scares affect pregnancy desire, or ambivalence about pregnancy, in a similar way, then pregnancy scares will have a direct effect on the likelihood of experiencing a later pregnancy. Second, for imperfect contraceptors, a pregnancy scare is likely to precede an actual unintended pregnancy, because the average pregnancy rate for any given month is only about 50% for young women even when sex is perfectly timed to ovulation (Dunson, Colombo, and Baird 2002). Third, personality traits or skills that lead to pregnancy scares may predict unintended pregnancy as well – for example, the ability to consistently adhere to a contraception regimen.

2. Methods

We use data from the Relationship Dynamics and Social Life (RDSL) study, which interviewed a random, population-based sample of 1,003 young women ages 18-19, residing in a Michigan county. Women were selected from the state driver's license and personal identification card databases. Investigators conducted a 60-minute face-to-face baseline survey between March 2008 and July 2009. Women then participated in a 2.5-year follow-up study that required completion of weekly online or telephone surveys about contraceptive use, relationships, and prospective pregnancy intentions. In this paper we refer to the follow-up study as “the journal,” and the weekly surveys as “journals”. The follow-up study concluded in February 2012. The response rate for the baseline interview was 84%, 99% agreed to participate in the journal, and 75% participated in the journal for at least 18 months.

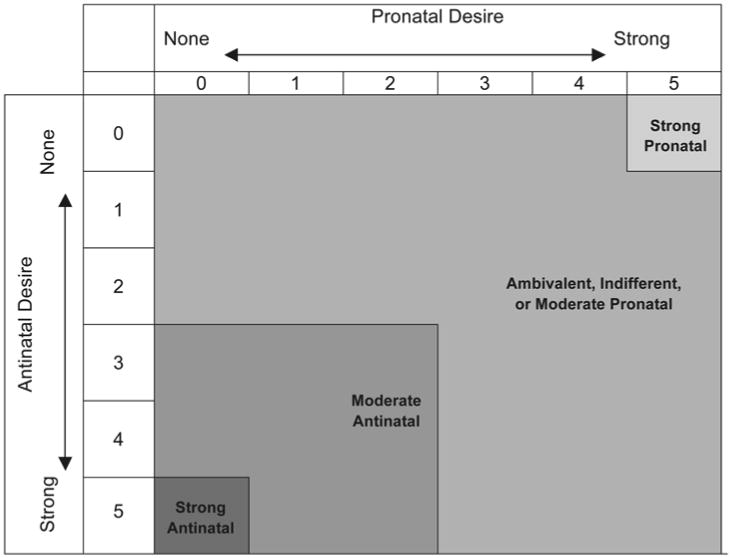

In this study we use only the first 18 months of the journal data to minimize bias from attrition. We analyze the weeks in which the respondent was not pregnant and did not strongly desire a pregnancy. We use two questions from the weekly surveys that measured pregnancy desires to identify those weeks. The first question asked respondents how much they wanted to get pregnant during the next month. The second question asked respondents how much they wanted to avoid getting pregnant during the next month. Both questions used a response scale from 0 to 5. Figure 1 summarizes the combined responses to these two questions, which we describe as strong antinatal, moderate antinatal, ambivalent/indifferent/moderate pronatal, and strong pronatal. The design of these measures and how they relate to subsequent pregnancy have been described elsewhere (Miller, Barber, and Gatny 2013). In this study we omit weeks classified as strong pronatal in Figure 1. The result is an analytic sample of 901 young women and 34,943 observations.

Figure 1. Categories of the combined responses to the questions measuring pregnancy desires.

2.1 Measures

Outcomes

Each week, respondents were asked about their pregnancy status, and are coded as “not pregnant,” “probably pregnant,” or “pregnant.” “Pregnant” is defined as a self-report of a positive pregnancy test. Of the 901 young women in our analytic sample, 114 (13%) reported 126 unintended pregnancies during the 18-month study period. Table 1 summarizes these statistics. Of those women who experienced an unintended pregnancy during the study, 89% reported only one and 11% reported two.

Table 1. Percent of sample experiencing unintended pregnancy and pregnancy scares (n=901).

| Percent | |

|---|---|

| Any unintended pregnancy | 13 |

| Number of unintended pregnancies (among those who experienced any unintended pregnancy, N= 114) | |

| 1 unintended pregnancy | 89 |

| 2 unintended pregnancies | 11 |

| Any pregnancy scare | 9 |

| Number of pregnancy scares (among those who experienced any pregnancy scare, N= 85) | |

| 1 pregnancy scare | 78 |

| 2 pregnancy scares | 13 |

| 3-4 pregnancy scares | 9 |

Because we are analyzing only weeks in which respondents do not desire pregnancy, any “probably pregnant” report that is not subsequently verified by a pregnancy test (or, eventually, a birth, miscarriage, or abortion) is considered a “pregnancy scare”. Descriptive statistics of these measures are also presented in Table 1. Of the 901 women in our analytic sample, 85 women (9%) reported 114 pregnancy scares during the 18-month study period. The majority reported only one pregnancy scare (78%), but a substantial proportion reported two (13%), and even three or four scares (9%). Of the 126 unintended pregnancies, 26 (21%) were preceded by a pregnancy scare within the study period, and among the 85 women who reported a pregnancy scare, 34 (40%) subsequently had an unintended pregnancy during the study (not shown in tables). Among the 816 women in our analytic sample who did not report a pregnancy scare, only 88 (11%) subsequently had an unintended pregnancy during the study (not shown in tables).

Sociodemographic characteristics and adolescent pregnancy-related experiences

We include characteristics measured in the baseline interview, summarized in Table 2. All of these variables are dichotomous, except high school GPA, which is continuous. Currently receiving public assistance includes WIC (Women, Infants and Children Program), FIP (Family Independence Program), cash welfare, or food stamps.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics and adolescent pregnancy-related experiences.

| Total Sample (n=901) | Subsample who did not experience a pregnancy scare (n=816) | Subsample who experienced a pregnancy scare (n=85) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| % | % | % | ||

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||

| African American | .34 | .32 | .54 | *** |

| Bio mom <20 years old at 1st birth | .36 | .34 | .52 | *** |

| Two-parent childhood family structure | .53 | .56 | .28 | *** |

| High school GPA a | 3.17 b | 3.20 | 2.93 | *** |

| Currently receiving public assistance | .26 | .24 | .40 | *** |

| Living with partner | .17 | .15 | .27 | *** |

| Adolescent Pregnancy-Related Experiences | ||||

| Age at first sex ≤ 16 years | .52 | .50 | .72 | *** |

| Two or more sexual partners | .59 | .57 | .79 | *** |

| Ever had sex without birth control | .47 | .45 | .71 | *** |

| 1 or more prior pregnancies | .25 | .23 | .44 | *** |

Note: + p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001 (one-tailed independent samples t-tests for significant differences between the two subsamples)

mean GPA presented for sample and subsamples;

std. dev.=.59

Other indicators

In regression models we use the total number of journals completed to control for repeated observation and exposure time. And, in hazard models, we include respondents' time in study, time in study squared, and total number of journals completed, to control for the increasing hazard of pregnancy and repeated observations. Time in study is coded in months and ranges from 0.49 to 18 months, with a mean of 8.60 months.

2.2 Data analysis

First we calculate the descriptive statistics for all independent variables for the total sample, as well as two subsamples: those who never experienced a pregnancy scare, and those who experienced a pregnancy scare (Table 2). Independent samples' t-tests indicate whether the independent variables are statistically different in the two subsamples. Next we investigate these characteristics in a multivariate context, using logistic regression for models of experiencing any pregnancy scare, and Poisson regression for models of the number of pregnancy scares (Table 3). Lastly, we estimate hazard models, implemented using logistic regression, to illustrate the relationship between a pregnancy scare and subsequent unintended pregnancy (Table 4). All analyses were conducted in Stata 12.1 using the logit, poisson, and xtlogit commands. The hazard models were estimated with xtlogit to account for the clustering effect of multiple journals per respondent.

Table 3. Regression coefficients for models of any pregnancy scare (logistic) and number of pregnancy scares (poisson) (N=901).

| (1) Any Pregnancy Scare | (2) Number of Pregnancy Scares | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||

| African American | .67*** (.27) | .81*** (.21) |

| Bio mom <20 years old at 1st birth | .30 (.25) | .18 (.20) |

| Two-parent childhood family structure | -.75*** (.28) | -.84*** (.24) |

| High school GPA | -.50*** (.18) | -.36*** (.14) |

| Currently receiving public assistance | -.07 (.30) | -.17 (.24) |

| Living with partner | .58*** (.30) | .49*** (.24) |

| Adolescent Pregnancy-Related Experiences | ||

| Age at first sex ≤ 16 years | .14 (.33) | .16 (.27) |

| Two or more sexual partners | .41 (.35) | .39† (.29) |

| Ever had sex without birth control | .48† (.31) | .67*** (.26) |

| 1 or more prior pregnancies | .36 (.30) | .15 (.24) |

| Other | ||

| Total number of journals completed | .01*** (.00) | .01*** (.00) |

| χ2 | 66.36 | 100.06 |

| Pseudo-R2 | .12 | .14 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001 (one-tailed tests)

Table 4. Logistic regression coefficients (additive effects on log-odds) for models of the hazard of unintended pregnancy (N=901 individuals, 34,943 observations).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any pregnancy scare | .99*** (.26) | .79*** (.28) | .73*** (.28) | |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||

| African American | .41** (.24) | .36+ (.23) | .36+ (.24) | |

| Bio mom <20 years old at 1st birth | .30+ (.22) | .35+ (.22) | .29+ (.22) | |

| Two-parent childhood family structure | -0.12 (.23) | -.16 (.23) | -.07 (.23) | |

| High school GPA | -0.28** (.17) | -.28* (.16) | -.23+ (.17) | |

| Currently receiving public assistance | .35+ (.26) | .36+ (.26) | .34+ (.26) | |

| Living with partner | .58** (.26) | .67** (.26) | .53** (.26) | |

| Adolescent Pregnancy-Related Experiences | ||||

| Age at first sex 16 years or less | .58** (.30) | .55** (.30) | ||

| Two or more sexual partners | .55** (.31) | .56** (.30) | ||

| Ever had sex without birth control | .30 (.27) | .24 (.27) | ||

| 1 or more prior pregnancies | .52** (.27) | 1.31*** (.21) | .85*** (.25) | .52** (.27) |

| Other | ||||

| Time in study | .25*** (.08) | .21*** (.08) | .23*** (.08) | .24*** (.08) |

| Time in study2 | -0.01** (.00) | -.01** (.00) | -.01** (.00) | -.01** (.00) |

| Total number of journals completed | -0.02*** (.00) | -.02*** (.00) | -.02*** (.00) | -.02*** (.00) |

| χ2 | 127.53 | 141.97 | 133.22 | 128.96 |

| Log-likelihood | -731.27 | -746.23 | -736.33 | -728.00 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001 (one-tailed tests)

3. Results

3.1 Characteristics of respondents who had a pregnancy scare

Table 2 shows that, overall, sociodemographic characteristics associated with disadvantage are overrepresented in the subsample of young women who experienced a pregnancy scare. For example, while only 32% of those who did not experience a pregnancy scare are African American, 54% of those who experienced a pregnancy scare are African American. Also, young women with early pregnancy-related experiences are overrepresented in the pregnancy scares subsample.

3.2 Multivariate models of experiencing a pregnancy scare

The results in Table 3 are similar to the bivariate results presented in Table 2, although some of the associations are not statistically significant in the multivariate models. Further, the results are quite similar across specifications – characteristics associated with the probability of experiencing a pregnancy scare are also associated with the number of pregnancy scares actually reported, with only minor differences.

Column 1 shows that young women who are African-American, did not have a two-parent family structure, had a lower GPA in high school, and/or were living with a partner had higher probability of a pregnancy scare. In addition, young women who had had sex without birth control in the past had marginally higher probability of a pregnancy scare.

Column 2 shows that these same individual characteristics are also associated with a larger number of pregnancy scares. In addition, young women with two or more sexual partners experienced a marginally higher number of pregnancy scares than their peers. This suggests that women who had multiple sexual partners are disproportionately represented in the group that experienced multiple pregnancy scares. In these multivariate regression models, having had sex without birth control is the only adolescent pregnancy-related experience strongly related to pregnancy scares. Recall that in the bivariate models, on the other hand, early sex, multiple partners, prior sex without birth control, and one or more prior pregnancies are strongly related to pregnancy scares. This suggests that early sex, multiple sexual partners, and prior pregnancy are associated with pregnancy scares largely because of the sociodemographic characteristics of those young women who have early sex, multiple partners, and teen pregnancies, or because of their association with having sex without birth control. This is consistent with existing research; for example, finding that early sexual debut is associated with less contraceptive use (Kusunoki and Upchurch 2011; Manning, Longmore, and Giordano 2000; Manlove, Ryan, and Franzetta 2007). Note also that respondents who completed more journals were more likely to report a pregnancy scare, likely in part because it is associated with more time in the study period.

3.3 Multivariate models of the hazard of experiencing an unintended pregnancy

Finally, in Table 4 we estimate hazard models to illustrate the relationship between a pregnancy scare and subsequent unintended pregnancy rates. Model 1 includes only the control variables and shows higher unintended pregnancy rates among young African American women, those whose mothers had their first birth as a teen, those with a lower high school GPA, those receiving public assistance, and those living with a romantic partner. In terms of respondents' prior experiences, unintended pregnancy rates are higher among those who had sexual intercourse at or before age 16, had two or more sexual partners during adolescence, and/or had an adolescent pregnancy. In addition, the time variables are significant – the risk of unintended pregnancy increases throughout most of the study period, but then declines slightly near the end (indicated by the small negative coefficient for the variable indicating squared months in the study). Respondents who completed more journals during the study also had a lower hazard of unintended pregnancy. Note that because total number of journals completed is net of time in the study in these models, the negative coefficient likely represents the type of respondent who completed many journals within a specific period. Thus, the negative association is due to characteristics that lead respondents to complete more journals and also reduce the risk of unintended pregnancy, for example, conscientiousness.

Model 2 shows that young women who experienced a pregnancy scare had higher subsequent unintended pregnancy rates than those respondents who did not. More precisely, the weekly log-odds of experiencing an unintended pregnancy were 99% higher, which translates into nearly double the unintended pregnancy rate for women who had a prior pregnancy scare compared to those who did not.

Model 3 indicates higher unintended pregnancy rates after a pregnancy scare even when measures of sociodemographic characteristics are included as controls. In other words, although women from disadvantaged backgrounds experience more pregnancy scares and higher unintended pregnancy rates, young women who experience a pregnancy scare have higher unintended pregnancy rates than their peers without a pregnancy scare, net of their disadvantaged background. However, the fact that the magnitude of the pregnancy scare effect declines by 20% between models 2 and 3 indicates that pregnancy scares are associated with unintended pregnancy in part because of the sociodemographic characteristics linked to both experiences.

The adolescent pregnancy-related experiences added to Model 4 explain an additional 6% of the relationship between pregnancy scares and unintended pregnancy, but the coefficient remains large and statistically significant. Although adolescent experiences with early sex and multiple partners are strongly related to the rate of unintended pregnancy, for the most part they do not explain the difference in unintended pregnancy rates between young women who experienced pregnancy scares and those who did not.

4. Discussion

We found that a substantial proportion (9%) of young women experienced a pregnancy scare during the 18-month study period. A wide range of sociodemographic characteristics and adolescent experiences were associated with pregnancy scares in our bivariate analyses. However, in our multivariate analyses, only being African-American, growing up with something other than a two-parent family structure, having a lower high school GPA, living with a romantic partner, and having sex without birth control during adolescence were independently associated with a higher probability of a pregnancy scare. We found similar results when we predicted number of pregnancy scares. This suggests that although pregnancy scares occur to all types of young women, those from less advantaged backgrounds are more likely to experience a pregnancy scare than those from more advantaged backgrounds.

We found that 21% of the unintended pregnancies were preceded by a pregnancy scare within the study period, and – even more dramatic – more than 40% of women who reported a pregnancy scare went on to experience an unintended pregnancy, even during the relatively limited period of observation in our study (18 months). In our hazard models, pregnancy scares are a strong predictor of unintended pregnancy, independent of key sociodemographic characteristics and adolescent experiences. In other words, young women who experience a pregnancy scare have higher unintended pregnancy rates than those who do not, regardless of their background. This suggests that pregnancy scares may be a harbinger of a future unintended pregnancy.

It is beyond the scope of the current study to discern the mechanisms that explain why pregnancy scares are followed by unintended pregnancies, but future research should examine whether young women's attitudes or behaviors change after this experience. Of course, we cannot rule out that other unknown or unmeasured factors associated with unintended pregnancy are captured by pregnancy scares. But even if this is the case, a pregnancy scare could mark an important point for intervention.

The study has several limitations. The single county sample design may decrease the generalizability of the results. The sample does, however, hold constant the geographic differences in pregnancy scares and/or unintended pregnancy rates, as well as the geographic factors (e.g., media, policy, etc.) that are not a focus in this study. The very few Latinas in the county, and in our sample, precludes assessing them as a separate category. Research has estimated that other surveys capture only about one-half of abortions (Jones and Kost 2007). Thus, unintended pregnancies that end in abortion are likely underrepresented in our analyses.

Finally, although we measure pregnancy desires prospectively with two unipolar scales, this measurement does not fully capture the range of emotions surrounding pregnancy. We also use a broad definition of “unintended” in this analysis – we consider all pregnancies that were not fully intended (i.e., strong desire to get pregnant and no desire to avoid pregnancy) to be unintended. Our goal in this analysis was not to develop a complex measure of the intention status of pregnancies or pregnancy scares, but rather to limit our analyses to time periods when young women were not specifically trying to become pregnant.

5. Conclusions

Our research describes the young women who have pregnancy scares – information we must have for reducing the incidence of these distressing events. In addition, we find that pregnancy scares often precede unintended pregnancies. Asking young women whether they have ever had a pregnancy scare is a simple and straightforward way to assess pregnancy risk, and may help clinicians gauge how effectively young women are using their chosen contraceptive method.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by two grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD050329, R01 HD050329-S1, PI Barber), a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21 DA024186, PI Axinn), and a population center grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to the University of Michigan's Population Studies Center (R24 HD041028). We thank N.E. Barr for valuable editing assistance, and John Casterline and Ann Biddlecom for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the paper. We gratefully acknowledge the Survey Research Operations (SRO) unit at the Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research for their help with the data collection, particularly Vivienne Outlaw, Sharon Parker, and Meg Stephenson. We also gratefully acknowledge the intellectual contributions of the other members of the original RDSL project team, including William Axinn, Mick Couper, and Steven Heeringa, as well as the Advisory Committee for the project: Larry Bumpass, Elizabeth Cooksey, Kathie Harris, and Linda Waite.

Footnotes

Paper presented at Session #74, “Contraception: The Determinants of Choice,” at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, March 31‒April 2, 2011, Washington, DC, U.S.A.

References

- Dunson D, Colombo B, Baird DD. Changes with age in the level and duration of fertility in the menstrual cycle. Human Reproduction. 2002;17(5):1399–1403. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.5.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff T, Greene L, Davis J. National survey of adolescents and young adults: Sexual health knowledge, attitudes and experiences. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Family Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RK, Kost K. Underreporting of induced and spontaneous abortion in the united states: An analysis of the 2002 national survey of family growth. Studies in Family Planning. 2007;38(3):187–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusunoki Y, Upchurch DM. Contraceptive method choice among young women in the united states: The importance of relationship context. Demography. 2011;48(4):1451–1472. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0061-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J, Ryan S, Franzetta K. Contraceptive use patterns across teens' sexual relationships: The role of relationships, partners, and sexual histories. Demography. 2007;44(3):603–621. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Longmore MA, Giordano PC. The relationship context of contraceptive use at first intercourse. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32(3):104–110. doi: 10.2307/2648158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WB, Barber JS, Gatny HH. The effects of ambivalent fertility desires on pregnancy risk in young women in the USA. Population studies. 2013;67(1):25–38. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2012.738823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Fast facts: How is the 3 in 10 statistic calculated? 2011 [electronic resource]. https://grist.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/fastfacts_3in10.pdf.