Abstract

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a parasomnia associated with dream enactment often involving violent or potentially injurious behaviors during REM sleep that is strongly associated with synucleinopathy neurodegeneration. Clonazepam has long been suggested as the first-line treatment option for RBD. However, evidence supporting melatonin therapy is expanding. Melatonin appears to be beneficial for the management of RBD with reductions in clinical behavioral outcomes and decrease in muscle tonicity during REM sleep. Melatonin also has a favorable safety and tolerability profile over clonazepam with limited potential for drug-drug interactions, an important consideration especially in elderly individuals with RBD receiving polypharmacy. Prospective clinical trials are necessary to establish evidence-basis for melatonin and clonazepam as RBD therapies.

Keywords: melatonin, REM sleep behavior disorder, parasomnia, drug therapy, calmodulin

1.1 Introduction1

Parasomnias are undesirable phenomena that occur during or around sleep. Without appropriate diagnosis patients may undergo extensive medical workup and exposure to unnecessary pharmacotherapy.[1] Parasomnias are characterized according to the stage of sleep in which they occur, (i.e. rapid eye movement (REM) or non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep). NREM parasomnias including night terrors, somnambulism, and confusional arousals are most prevalent in pediatric populations. By contrast, in REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), a REM parasomnia, the usual age of onset is in adults and elderly between 40 to 70 years of age. [2] RBD is believed to be a result of brainstem dysfunction, most likely involving the dorsal pontine sublateral dorsal nucleus and/or magnocellular reticular formation (+/− their afferent and efferent connections), leading to loss of the brain’s normal ability to regulate physiologic REM sleep atonia.[2,3] The absence of appropriate central nervous system regulation of REM sleep atonia then may result in dream-enactment, leading to complex motor behaviors paralleling dream content including talking, arm flailing, punching, kicking, or other potentially violent behaviors.[4] Behaviors exhibited in RBD may place both the patient and bed partner at risk of physical harm, with between 32–64% injuring either themselves or their bed partner, respectively.[5,6] In one case series of 96 patients the incidence of bone fracture during RBD was found to be 7%.[7] More severe cases involving strangulation and subdural hematoma have also been reported.[5,6,8–10] The majority of RBD cases occurring in older adults remain idiopathic, at least initially, although a presumptive underlying cause of synucleinopathy neurodegeneration and eventual emergence of overt parkinsonism, autonomic, or cognitive dysfunction has been recognized in recent years [2,11–16], and RBD may also be seen in younger adults associated with narcolepsy and antidepressant use.[17,18] Several other medications have also been associated with either the emergence or worsening of RBD (see Table 1).[19] Clonazepam, a benzodiazepine, is the pharmacologic agent which has been the most commonly used treatment for RBD.[7, 20, 21] The beneficial effects of melatonin in RBD were first described in 1997 by Kunz and Bes.[22] Subsequently, further literature and guidelines have suggested melatonin to provide clinical benefit in patients who require pharmacologic treatment for RBD.[2, 20, 21, 23] The following is a review of literature evaluating melatonin for the management of RBD.

Table 1.

Medications associated with occurrence or worsening of RBD 19

| Caused by acute administration | Caused by withdrawal |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors | Ethanol |

| Selective serotonin/norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitors | Benzodiazepines |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Barbiturates |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors | Meprobamate |

| Mirtazapine | Pentazocine |

| Cholinesterase inhibitors | |

| Beta blockers | |

| Tramadol | |

| Caffeine | |

1.2 Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone which is secreted in a circadian rhythm from the pineal gland. Secretion is influenced by dark environments with melatonin serum levels beginning to rise shortly after nightfall and peaking during the middle of the night (i.e. approximately 2 to 4 AM). [24] Secretion may be reduced as a result of environmental light, severe illness, pineal calcification or advanced age.[25–28] While low doses of melatonin have been evaluated, doses of 2–6 mg are generally necessary for clinical effect. An exogenous dose of 1 mg and 10 mg melatonin can respectively increase serum melatonin concentrations 10 to 100 times physiologic concentrations after one hour of administration, with concentrations declining to baseline roughly four to eight hours post ingestion.[29]

2.1 Literature Search

A search was performed of MEDLINE and PUBMED databases for studies between 1966 and February 2014, using the search terms ‘melatonin’ and ‘REM sleep behavior disorder’. The search was limited to adult populations written in English language. Studies included prospective randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, prospective open-label trials, prospective comparative studies, and retrospective case series. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and reference lists of included trials were also searched to identify any additional relevant publications. A total of 39 abstracts were identified initially and were reviewed independently by two authors (IM and JL) who judged appropriateness for inclusion. Articles which met inclusion for criteria were read in entirety. A third author (ES) assisted with selection of additional relevant studies. Four prospective and two retrospective reports of melatonin for the treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder were identified and can be found in Table 2. There were no articles found in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, nor were there any additional trials identified from review of included article references.

Table 2.

| Prospective Reports | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | N | Population | Treatment | Results |

| McCarter et al., 2013 | 45 |

|

|

|

| Kunz and Mahlberg, 2010 | 8 |

|

|

|

| Takeuchi et al., 2001 | 15 |

|

|

|

| Kunz and Bes, 1999 | 6 |

|

|

|

| Retrospective Reports | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | N | Population | Treatment | Results |

| Lin et al., 2013 | 28 |

|

|

|

| Boeve et al., 2003 | 14 |

|

|

|

3.1 Prospective Trials Evaluating Melatonin Use in RBD

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over trial evaluated the effects of melatonin on the percentage of REM sleep without atonia and a clinical global improvement scores in subjects with RBD. A total of 8 males, mean age 54 years, with diagnosis of RBD per the International Classification for Sleep Disorder (ICSD) and reported RBD symptoms for 5–20 years were included in this trial. Several subjects had concomitant disorders including: narcolepsy with periodic limb movement disorder (n = 2), Parkinson’s disease (n = 1) and idiopathic insomnia (n = 2). Subjects were excluded if they had performed shift work within the last year, poor sleep hygiene, a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th ed. (DSM-IV) psychiatric diagnosis, pathological brain imaging findings, changes of any medication within the past month or ingestion of any medication which may interfere with melatonin levels or REM sleep. The subject with Parkinson’s disease was noted to only receive one medication (375 mg/d L-dopa) during this trial, whereas all other subjects were noted to be medication free during the study period. Subjects were randomized to receive either placebo or melatonin 3 mg nightly during the 4-week study. This was followed by a three to five day washout period and switching of treatment assignments. A polysomnography (PSG) recording was performed three times in all subjects: baseline and after the end of both treatment assignments. Clinician’s global improvement (CGI) was assessed at baseline and at the end of each treatment period. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate differences in sleep parameters between groups. At the conclusion of the study, authors reported that melatonin decreased the percentage of REM sleep without atonia from 39.2% to 26.8% (p = 0.012) and sleep onset latency by 1.96 minutes (p = 0.05) compared to baseline; however, statistically significant change was not found when compared to placebo. Melatonin produced a decrease in percent of REM-epochs with more than 50 percent of epochs with muscle tone (p = 0.012) compared to baseline, a change which was not found with placebo. Placebo administration after the cross-over period showed decrease in sleep-onset latency from baseline (−2.03 min, p = 0.043), but this change was not found in the melatonin group. No other sleep variables measured (sleep onset latency, REM onset latency, total sleep time, sleep period time, wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency, REM-density, phasic muscle twitches, and percent sleep in N1, N2, N3, and REM sleep) demonstrated statistically significant change. A decrease in CGI score severity averaged 1.5 points (p = 0.024) and 0.5 (p = 0.102) with melatonin and placebo administration respectively compared to baseline. CGI change compared between placebo and melatonin was statistically significant (p = 0.031). Seven of the eight subjects reported improvement in RBD symptoms [complete resolution (n = 4), marked improvement (n = 2), and little improvement (n = 1)]. Symptom improvements were reported within the first week of treatment and continued to improve over the 4-week study period. No subjects reported adverse events from melatonin treatment. The authors concluded that treatment with melatonin effectively improved clinical and neurophysiological aspects of RBD, though the most effective dose and duration are yet to be determined. Authors also note that melatonin had continued effects after administration was stopped due to statistically significant decreased REM sleep without atonia found in the placebo group after assignment cross-over. Although the study was well designed, several limitations should be considered. In this small study, the use of additional medications was minimal, suggesting the study population was relatively healthy which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Secondary outcomes are particularly difficult to interpret as type II errors could be likely given the very small sample size and lack of an a priori known effect size on which to design an appropriately powered study. However, results of this small pilot prospective trial showed melatonin administration at 3 mg nightly produced a statistically significant decrease in REM sleep without atonia as well as subjective improvements in clinical symptoms of RBD.[30]

An open-label trial assessed the effects of exogenous melatonin in six subjects with PSG confirmed RBD over a six week period. Subjects included had concomitant disease of hypertension (n = 2), Parkinson’s disease (n = 1), and sympathetic dysautonomia (n = 1). Brain imaging was reported as normal in all subjects. Subjects were not allowed to take medications which could interfere with REM sleep (benzodiazepines, antidepressants, beta-blockers, or anti-inflammatory drugs). Medications reported to be used during the study period included: L-dopa (n = 1), nifedipine (n = 2), furosemide (n = 1), and fludrocortisone (n = 1). Subjects had a mean age of 54 years and were described to have RBD symptoms for an average of 13 years. RBD symptoms reported included: nightly screaming and yelling (n = 6), jumping/falling out of bed once weekly during frightening dreams (n = 2), jumping/falling out of bed three to five times weekly during frightening dreams (n = 2), chronic exhaustion (n = 2), and early retirement due to impaired functioning (n = 2). Subjects took melatonin 3 mg nightly prior to bedtime. Subjects had PSG recordings at baseline and after six weeks of therapy. All subjects had lack of atonia at baseline per PSG findings. Changes in PSG data were analyzed with the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. Motor activity during sleep was assessed with actigraphy for a two week period at baseline and during treatment weeks five and six. After one week of treatment, five subjects reported improvement in RBD symptoms and were considered to respond to therapy. None of the responding subjects fell or jumped out of bed during treatment and yelling during sleep was reduced from every night to once weekly. Melatonin responders reported a reduction in frightening dreams from baseline, as no frightening dreams were reported during the treatment period. The majority of PSG measurements did not change over the duration of treatment. The percentage of REM sleep without atonia yielded a statistically significant decrease from 32% to 11% (p = 0.028). Movement time in REM (percent per minute) showed a statistically significant decrease from 4.36 to 1.2 (p = 0.043). Actigraphy data showed a slight reduction of movements per minute percent time in bed (30.5 at baseline to 28.6 post treatment), though these findings were not statistically significant (p = 0.17). Additionally, percent wake time after sleep onset trended toward improvement (21.6 at baseline to 11.6 post treatment) but was not statistically significant (p = 0.29). After discontinuation of melatonin, RBD symptoms were reported to return in all responding subjects (range 1–22 months). [31] The one subject who did not report improvement in RBD symptoms was non-adherent to melatonin administration times and had poor sleep hygiene.[32] Authors concluded that treatment with melatonin 3 mg improves clinical symptoms of RBD and restores circadian modulation of REM sleep in subjects with internal desynchrony. The small sample size and lack of placebo comparator are limitations to this study. As the method of evaluating clinical outcomes was not reported (i.e. structured interview, questionnaire, etc) consistency of obtaining reports is unknown, which bring some question to the internal validity of the study. The statistically significant objective reductions in percent REM sleep without atonia and movement time during REM sleep occurred within the first week of treatment with re-emergence of symptoms after melatonin discontinuation suggesting melatonin 3 mg at bedtime provides benefit in the treatment of RBD. [31]

An open label trial evaluated the effects of exogenous melatonin in fifteen adults with RBD confirmed by PSG and symptomatic history. The average age of all subjects was 63.5 years and all but one subject was male. Subjects were allowed to take melatonin 3, 6, or 9 mg according to degree of clinical RBD symptoms. When symptoms were determined to be improved and/or stable, a repeat PSG and melatonin serum concentration was conducted. PSG findings showed the percentage of tonic REM activity decrease from 16.43% to 5.99% after melatonin treatment (p < 0.01). While a trend towards increased total sleep time, increase in the number of REM periods each evening, and decrease in percentage of phasic REM activity occurred, none of these differences were statistically significant. Subjective improvement in RBD symptoms occurred in thirteen subjects. Potentially injurious symptoms or injuries (vigorous sleep behaviors, ecchymoses, lacerations, and fractures) were reported to be reduced by 25% (n = 1), 50% (n = 9) and 75% (n = 3). Few subjects complained of adverse effects from melatonin such as excess morning sedation or weakness. Authors concluded that melatonin therapy greatly improved clinical symptoms of RBD, and that melatonin may be a useful alternative to clonazepam, especially in elderly patients as adverse events were minimal. Numerous limitations regarding study design lead to challenges with interpretation of data in this small study, including a lack of reporting therapy duration, the time to clinical improvement, concomitant disease states and additional medications allowed. Important details not described include the dosage of melatonin and corresponding degrees of response, methodology of assessing clinical improvements, and the tracking of melatonin adherence. Adverse effects were not reported. While melatonin appeared to improve clinical outcomes in RBD in this study, the inherent limitations and lack of reporting leave clinicians with little insight into effective dosing, duration of therapy needed for clinical improvement, and clinical improvement expectations upon dosage changes.[33]

A naturalistic survey of patient-reported clinical outcomes in patients with RBD offers additional support for the use of melatonin in RBD. One hundred and thirty three adult patients who had been diagnosed with RBD between 2008 and 2010 were sent a survey in order to assess outcomes between common therapies. A total of 45 patients responded and were eligible for inclusion; among these patients, 25 were initially taking melatonin, 18 were initially taking clonazepam and two were taking both. The survey was completed by the patient and their bed partner or a family member who had witnessed their RBD. The survey used an analog scale which assessed baseline and post-treatment RBD behaviors including: frequency, severity, behavior type, falls, and injury. Patients included were 78% male, averaged an age of 66 years old and had mean RBD symptom onset at 54 years old. The majority of patients had a co-morbid neurodegenerative disorder (53%) or received a selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressant (56%). Thirteen patients (29%) were diagnosed with depression and thirty patients (67%) were diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea. Only three patients in each treatment group reported complete remission of RBD symptoms with no statistically significant difference found between groups (p = 0.68). Both treatments decreased frequency and severity of dream enactment behavior (pre- versus post-treatment melatonin, 6.6 versus 4.2 (p = 0.0001); pre- versus post-treatment clonazepam, 6.5 versus 4.1 (p = 0.0005)), but no difference was found between treatment groups. A significant reduction in falls and injury were demonstrated with melatonin (pre- versus post-treatment falls, 60% versus 20% (p = 0.002); (pre- versus post-treatment injury, 64% versus 20% (p = 0.001)). These findings were not replicated with statistical significance (although trends were suggested) for the clonazepam group (pre- versus post-treatment falls, 67% versus 33% (p = 0.07); pre- versus post-treatment injury, 61% versus 33% (p = 0.06)). Reported effective doses of melatonin in patients were 6 mg or less (52%), 9–12 mg (32%) and 15–25 mg (16%). Reported effective doses of clonazepam in patients were 0.5 mg or less (56%), 1 mg (11%), 2 mg (22%) and 3 mg (6%). Patients taking clonazepam reported a higher percentage of all adverse effects versus melatonin, though these were not statistically significant (overall adverse event 61% versus 33% (p = 0.07); unsteadiness 39% versus 8% (p = 0.07); dizziness 22% versus 4% (p = 0.08)). Discontinuation of treatment rates were not statistically significant between groups (28% for melatonin and 22% for clonazepam (p = 0.71)). As this single-center study has several limitations including potential biases in selection, sampling, and outcomes recall, results cannot be generalized to all patients with RBD. However, this study demonstrates similar clinical outcomes between melatonin and clonazepam in a moderate-sized patient population in a naturalistic clinical setting.[21] The high representation of patients with neurodegenerative disorders, major depression, and selective serotonin/norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitor use seen in this study strengthens evidence for melatonin in these particular patient populations which were underrepresented in previous crossover and open-label trials evaluating melatonin in RBD.[30,31,33]

3.2 Retrospective Evidence Evaluating Melatonin Use in RBD

A retrospective case series evaluated efficacy of initial melatonin monotherapy followed by combination clonazepam therapy in 28 Taiwanese patients with RBD. The majority of patients were referred to the sleep clinic for suspected obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), followed by insomnia complaints in patients with neurological disease. Patients underwent a systematic interview which included interview of a bedpartner or caregiver. After evaluation of comorbidities and associated disease states, a PSG evaluation was conducted in addition to electromyogram (EMG) activity scoring. Patients who presented with sleep-disordered breathing were then controlled with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Patients with abnormal EMG activity and sleep behaviors entered into the clinical treatment protocol. A four week observational period occurred in which bedpartners documented the number of nights with the presence of abnormal sleep behaviors. A second PSG with video monitoring was conducted at the end of the observational period. Patient follow-up involving patient and bedpartner interview and review of the previous four weeks sleep log. Additionally, PSG and EMG scoring in REM was conducted the month following the observation period and every other month for a total of seven months. Of the 28 patients included in the clinical protocol, the mean age was 66.5 years, mean Body-Mass-Index was 26.6 kg/m2, 72% were male, abnormal sleep behavior was reported for 2.5 ± 3.2 years, and movement of extremities while sleeping resulted in mild bedpartner trauma in eighty-two percent of patients. Comorbid conditions consisted of OSA (n = 16), Parkinson’s disease (n = 10), poor nocturnal sleep (n = 7) and cognitive decline (n = 4). Albeit comprehensive medication profiles were not available, medications used for treatment of neurological disorders were reported as unchanged during the treatment protocol. The two initial patients included in the protocol were started on melatonin 3 mg nightly prior to bedtime, however, no change in reported behavioral patterns or PSG with EMG scoring was found after the first four weeks of therapy. These two patients began combination therapy with clonazepam which was increased from 0.5 mg to 1 mg nightly after one month. After a two month follow-up after initiation of clonazepam, the reported behavioral patterns were improved. However, improved behaviors did not persist at the four month follow-up, at which melatonin was increased to 6 mg nightly in addition to clonazepam 1 mg nightly. Due to the potentially ineffective 3 mg melatonin dose used in the two initial patients, clinical protocol was changed to prescribe melatonin 6 mg nightly in the subsequent 26 patient cases reported. These 26 patients underwent four months of melatonin therapy, received follow-up, and then were prescribed clonazepam 0.5 to 1 mg nightly in addition to melatonin until the end of the seven month clinical protocol. Statistically significant reductions of nights with dream-acting-out and nights with vocalizations from baseline (9.8 ± 5.13 and 9.18 ± 5.13 respectively) were found with melatonin 6 mg nightly at month four follow-up (1.08 ± 2.81 and 0.61 ± 0.96 respectively) and with melatonin 6 mg nightly plus clonazepam 0.5 to 1 mg nightly at month six follow-up (0.10 ± 0.05 and 0 respectively) (p ≤ 0.001). Percent wake after sleep onset (WASO) was reduced from baseline (11.37 ± 3.25) to month four (8.11 ± 2.48) (p = 0.001) and further at month six (5.53 ± 2.38) (p = n/a). Percent of high EMG during total REM sleep time was reduced from baseline (46.98 ± 16.66) at month four (1.37 ± 2.47) and month six (2.55 ± 9.34) (p = 0.001). No statistically significant difference was found between percent of high EMG during total REM sleep time between month four and six likely due to small sample size and possible type II error. One patient with idiopathic RBD was followed past the seven month follow-up due to treatment failure. This patient was reported to use physical restraints while sleeping in addition to 12 mg melatonin and 3 mg clonazepam nightly after twelve months of follow-up. Authors emphasized the importance of affirming an OSA diagnosis and CPAP treatment in patients believed to have RBD. Additionally, authors state further research is needed to establish PSG cut-off points in which elimination of abnormal sleep behaviors will occur as well as further understanding of underlying processes in patients who do not respond to current therapies used in RBD. Limitations to this report are significant for a small sample size, limited duration of follow-up, and no placebo control or randomization. Despite these limitations, important outcomes were found through sleep journaling, structured patient and bedpartner interviews, and PSG and EMG evaluations.[34]

A second retrospective case series evaluated melatonin in fourteen patients with RBD and various comorbid neurologic disorders. The majority of patients were male (93%), had a mean RBD diagnosis at 56 years of age, and had a mean onset of neurologic disorder at 65 years of age. Patients had diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodies (n = 7), mild cognitive impairment with mild parkinsonism (n = 2), multiple system atrophy (n = 2), narcolepsy (n = 2) and Parkinson’s disease (n = 1). Patients were administered open-label melatonin 3–12 mg (mean 6.75 mg) nightly due to previous incomplete or adverse response to clonazepam, significant dementia, or an OSA diagnosis. Patients were allowed to take psychotropic medications which included: clonazepam (n = 6), donepezil (n = 9), selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants (n = 5), carbidopa/levodopa (n = 4), and psychostimulants (n = 2). PSG recordings were performed in 13 patients, with 12 studies confirming RBD. Duration of patient follow-up was 9–25 months (mean 14 months). Clinical response was reported as controlled in six patients (2 patients used concomitant 0.5–1 mg clonazepam), markedly improved in four patients (3 patients used concomitant 0.5 mg clonazepam), short-term benefit in 2 patients (both taking concomitant 0.5 mg clonazepam) and either no improvement or clinically worsening in 2 patients. Adverse effects of delusion/hallucination (n = 1), headache (n = 2), and morning sleepiness (n = 2) were reported in patients taking greater than or equal to 9 mg of melatonin nightly. Authors additionally note that patients taking donepezil showed less significant changes in frequency or severity of RBD symptoms. This single-center, uncontrolled, open-label, primarily male report has several limitations and results cannot be generalized to all patients with RBD. However, this work demonstrates important clinical outcomes in a small population of patients with various neurological diseases and medication profiles.[23]

4.1 Discussion

Treatment with exogenous melatonin for RBD was found to yield a statistically significant decrease in REM sleep without atonia in one randomized placebo-controlled trial and two open-label trials.[30,31,33] However, polysomnographic REM sleep without atonia (RSWA) may be an incidental finding as polysomnography without clinical symptoms, and RSWA alone cannot be equated with a clinical diagnosis of RBD, so the more important treatment outcomes are behavioral symptom changes in RBD.[2] Kunz and Mahlberg demonstrated melatonin therapy yielded decreased CGI scores to a greater degree than placebo and reduced symptom severity in a large majority of subjects. [30] Additionally, major reductions from baseline in yelling while sleeping, jumping/falling out of bed, lacerations, fractures, ecchymosis, vigorous sleep behaviors, and frightening dreams were reported, as well as moderate to remarkable clinical improvement in 86% of subjects by Takeuchi and colleagues.[33] Unfortunately, the results of these trials are difficult to generalize amongst all patients with RBD. Subjects with DSM-IV diagnoses were excluded in two trials and unclear in the third, thus, results may not be applicable to patients with these diagnoses.[30,31,33] This is an important consideration as comorbid depression with use of antidepressants could potentially negate any benefit of melatonin. As an example, the frequency of major depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease and dementias is estimated to be 17% and 32%, respectively.[35,36] As antidepressants may worsen RBD,[37] further investigation is warranted to assess melatonin for the management of RBD in patients with comorbid depression. It may also be difficult to generalize trial results to patients with neurodegenerative disorders as only two subjects were reported to have Parkinson’s disease by Kunz and Mahlberg [30] and Kunz and Bes [31] and concomitant diagnoses were not reported by Takeuchi and colleagues.[33] Between approximately 50–81% of patients with RBD may develop overt cognitive, motor, or autonomic symptoms of neurodegenerative disease following an initial RBD diagnosis during longitudinal follow-up.[2,11,13,14,16, 20] Results from retrospective studies [13,34] shed insight into expected clinical responses in patients with various neurologic disorders and medication regimens seen in clinical practice.

Melatonin is generally well tolerated with minimal adverse events. In a toxicological assessment of 10 mg melatonin nightly for a 28 day period, adverse effects were similar to placebo and included: somnolence, headache, fatigue, and cognitive alteration.[38] Additionally, dysgeusia and decrease of 0.2°C body temperature two to three hours post ingestion have been reported.[38,39] The most common adverse effect associated with melatonin treatment in McCarter et al’s patient-reported outcomes study was sleepiness in 29% of 25 treated RBD patients, followed by trouble thinking (12%), unsteadiness (8%), nausea (8%), dizziness (4%), and sexual dysfunction (8%), and each of these was most frequently rated to be mild in severity. [21] The most commonly used dose in RBD trials was 3 mg nightly before bedtime, with no adverse events reported at this dose.[30,31] Headache and morning sedation were reported in a small number of patients receiving doses of 9 mg or greater, but diminished upon dosage reduction.[23] Given the favorable side effect profile, melatonin can be an alternative when clonazepam is not tolerated or less ideal for use.

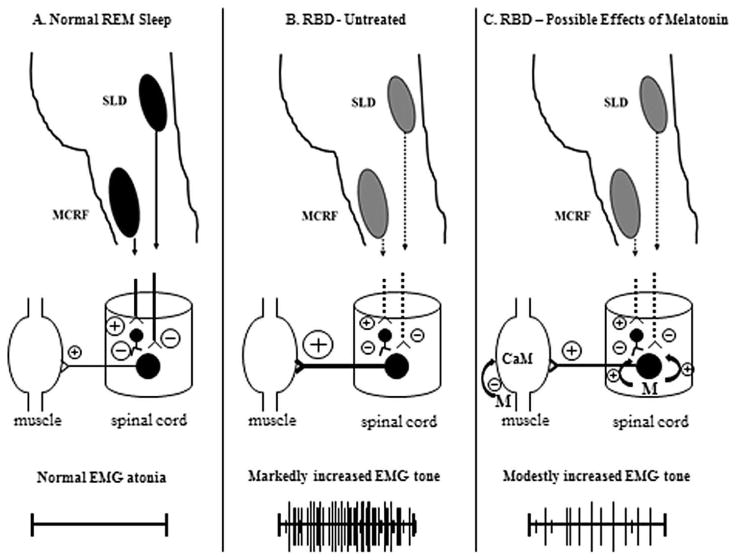

Melatonin’s mechanism of action against RBD (see Figure 1) remains unclear, but could be mediated by a combination of influences including a direct impact on REM sleep atonia, modulation of GABAergic inhibition, stabilizing circadian clock variability and desynchronization, and increasing sleep efficiency.[31–33,40,41] In a glycine/GABA-A receptor knock-out transgenic mouse model of RBD, melatonin was more efficacious than clonazepam in decreasing REM motor behaviors and restoring REM muscle atonia.[42] The transgenic mouse model could aid development and future application of more specific RBD treatments. A neurotransmitter mechanism could also play a role in the pathophysiology of RBD as it has been proposed the ratio of cholinergic to aminergic activity facilitates REM sleep,[43] in which acetylcholine has multiple roles.[44] Though report of nightmares and enhanced dreaming with acetylcholinesterase inhibitor poisoning are available,[45] patients with RBD taking acetylcholinesterase inhibitors have been reported to have both lessened response in RBD outcomes [23] as well as improvement.[46] Melatonin inhibits calmodulin which then may modulate skeletal muscle acetylcholine receptors.[47] Through this mechanism as well as antioxidant properties, it is believed melatonin may be important for receptor maintenance in aging persons.[48] It is also presumed that melatonin modulates cytoskeletal structure through its antagonism of calmodulin.[49] As serotonergic medications could be responsible for causing secondary RBD [37], it is important to also consider this mechanism. Serotonin agonism has shown to induce muscle tonicity in animal gastric intestinal tract [50,51] and human skeletal muscle.[52] Attenuation of serotonin induced contraction was demonstrated with pretreatment of nifedipine, cromakalim, dizoxide, caffeine and sodium nitroprusside; but acetylcholine induced contractions were refractory to these agents, suggesting two distinct contraction pathways.[50] Due to these data, the pathophysiology of RBD could be multifactorial, in which more research is necessary.

Figure 1. Speculative Mechanism of Action of Melatonin in RBD.

A. Normal REM sleep physiology. The sublaterodorsal nucleus (SLD) and magnocellular reticular formation (MCRF) nucleus send projections to the anterior horn cell (AHC) neurons in the spinal cord, with the GABAergic +/− glycinergic effects on the AHC exerting inhibitory influences (thereby suppressing AHC activity) and resulting in normal EMG atonia.

B. REM sleep behavior disorder. In RBD associated with neurodegenerative disease, the SLD and/or MCRF are presumed to undergo neuronal loss such that their projections on the AHC ultimately have decreased effects. Other projections from brainstem, diencephalic and telencephalic structures maintain their excitatory influences on the AHC (for simplicity, these projections are not shown here), resulting in increased EMG tone +/− the behavioral aspects of RBD.

C. REM sleep behavior disorder treated with exogenous melatonin. Melatonin may decrease the electrophysiologic and behavioral manifestations of RBD by potentiating the action of GABA on GABAA receptors on the AHC. Melatonin also may decrease calmodulin, which subsequently may modulate cytoskeletal structure and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression in skeletal muscle cells.

The encircled plus symbols represent excitatory influences; the encircled minus symbols represent inhibitory influences, and their relative size represents the degree of the influences. The symbol M represents melatonin, with the encircled plus symbols representing the potentiation of GABA on the GABAA receptors on the AHC. The symbol CaM represents calmodulin.

Given the proposed novel mechanism of action for melatonin in RBD, it could be likely other melatonin receptor agonists offer utility in RBD. Agomelatine is a melatonin 1 and 2 receptor agonist with 5-hydroxytrypamine 2 agonist activity.[53] In a case series of three patients, agomelatine at doses of 25–50 mg prior to bedtime reduced frequency and severity of RBD episodes over a period of 6 month follow-up. Reduction of dream production was also noted, which was believed to be due to normalization of REM sleep in addition to enhanced dopamine and noradrenaline activity in the frontal cortex, leading to subsequent decrease in excitatory glutamate release. Patients tolerated agomelatine and no adverse events were reported.[54] The melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon has documented evidence in two patients with RBD secondary to multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease. Patients took ramelteon 8 mg prior to bedtime and demonstrated clinical RBD improvement as well as decrease in REM sleep without atonia. Both patients were withdrawn from ramelteon therapy, suffered from enhanced RBD symptoms, and then were continued on the medication for at least two years.[55] As few data are available regarding melatonin receptor agonists in RBD, more research is necessary to determine their potential role in therapy.

Clonazepam is still recommended by many clinicians as the first-line therapy for RBD. The efficacy of this medication has been reported in over 300 patients in low level evidence exclusively retrospective case series reports.[20] In contrast to the seemingly benign adverse event profile of melatonin, clonazepam is associated with considerable side effects and has the potential for drug interactions. The 2012 Beers Criteria states that benzodiazepines may be appropriate for REM sleep disorders but warns of an increased risk of cognitive impairment, delirium, falls, fracture, and motor vehicle accidents.[56] In a retrospective study of 36 patients being treated with clonazepam for RBD, 58% of patients were noted to have moderate to severe adverse effects, and 36% of patients discontinued therapy due to adverse effects.[57] In McCarter et al’s report of 18 RBD patients receiving clonazepam, the most common adverse effects were sleepiness (56%), unsteadiness (39%), trouble thinking (39%), dizziness, (22%), sexual dysfunction (17%), and nausea (6%).[21] In one large review and clinical guide, the most commonly cited adverse effects of clonazepam were sedation, impotence, motor incoordination, and confusion/memory dysfunction.[20] Additionally, clonazepam is a cytochrome P450 substrate, with potentially inducible metabolism by certain antiepileptic drugs such as carbamazepine which increases the metabolism of clonazepam and reduces its serum concentration, whereas certain other medications such as clarithromycin may instead raise clonazepam serum levels, and increase the risk for toxicity. [58] These risks must especially be considered in RBD treatment given that most RBD patients are elderly and may have motor or cognitive impairments making adverse effects more likely, and many receive polytherapy with other medications.[59,60] C lonazepam also is a potential upper airway suppressant that must be used with caution when treating RBD patients with co-morbid obstructive sleep apnea. Clonazepam is also rated as pregnancy category D, making it a poor choice for use in women of child bearing potential.[61] Finally, clonazepam is an FDA scheduled substance with abuse potential and may not be a treatment of choice in those with either an active or previous history of substance use disorders.[62]

5.1 Conclusion

Melatonin appears to be an effective medication in RBD [13,21,30,31,33,34] and may have a more direct effect on the pathophysiology of RBD than clonazepam.[30–32] The pathophysiology of RBD is unknown as is melatonin’s mechanism of action. We hypothesize that melatonin’s activity as a calmodulin antagonist may impact RBD pathophysiology. Currently there is no clinical trial which has compared melatonin and clonazepam, however, a consensus statement from the International Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder Study Group seeks to devise a high level of evidence study.[63] Until new evidence is made available, the small body of supportive literature and favorable adverse effect profile make melatonin an attractive treatment option for patients with RBD, especially elderly individuals with underlying neurodegenerative disorders, co-morbid sleep apnea, and those receiving polypharmacy with other medications.

Highlights.

Melatonin can reduce REM sleep without atonia in RBD

Melatonin doses of 3–12 mg appear efficacious in reducing clinical RBD symptoms

Minimal side effects may favor melatonin over clonazepam as initial therapy in RBD

More placebo-controlled and active comparator trials are needed to confirm benefit

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number 1 UL1 RR024150-01.

EK St. Louis: EK St. Louis reports that he receives research support from the Mayo Clinic Center for Translational Science Activities (CTSA), supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number 1 UL1 RR024150-01.

BF Boeve: BF Boeve reports that he is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Cephalon, Inc., Allon Pharmaceuticals, and GE Healthcare. He receives royalties from the publication of a book entitled Behavioral Neurology of Dementia (Cambridge Medicine, 2009). He has received honoraria from the American Academy of Neurology. He serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Tau Consortium. He receives research support from the National Institute on Aging (P50 AG016574, U01 AG006786, RO1 AG032306, RO1 AG041797 and the Mangurian Foundation.

Glossary of terms

- Atonia

lack of tone or energy

- Phasic muscle twitches

percentage of 20sec mini-epochs REM with at least one muscle twitch

- REM-density

percentage of 3-sec mini-epochs REM with at least one REM

- REM onset latency

interval between lights off and first epoch sleep other than stage REM

- Sleep efficiency

percentage of total sleep time on sleep period time

- Sleep onset latency

interval between lights off and first epoch sleep other than stage NREM

- Sleep period time

interval between first and last epoch stage NREM 2, 3, 4 or REM

- Total sleep time

sum of all epochs in NREM 1, 2, 3, 4, and REM

- Wake after sleep onset

time spent awake after sleep initiation before final awakening

Footnotes

Abbreviations: clinician’s global improvement (CGI), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders 4th edition (DSM-IV), electromyogram (EMG), international classification for sleep disorders (ICSD), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), non-rapid eye movement (NREM), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), polysomnography (PSG), rapid eye movement (REM), REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI), wake after sleep onset (WASO)

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors IR McGrane and JG Leung have no conflicts of interest to disclose, regarding, but not limited to: place of employment, consultancies, stock ownership, honoraria, paid expert testimony, patent applications, grants, or other funding.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ian R. McGrane, Email: imcgrane@shodair.org.

Jonathan G. Leung, Email: Leung.Jonathan@mayo.edu.

Erik K. St Louis, Email: StLouis.Erik@mayo.edu.

Bradley F. Boeve, Email: bboeve@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Tinuper P, Bisulli F, Provini F. The parasomnias: mechanisms and treatment. Epilepsia. 2012;53(Suppl 7):12–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03710.x. Epub 2012/11/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder: Updated review of the core features, the REM sleep behavior disorder-neurodegenerative disease association, evolving concepts, controversies, and future directions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:15–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05115.x. Epub 2010/02/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luppi PH, Clément O, Valencia Garcia S, Brischoux F, Fort P. New aspects in the pathophysiology of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder:the potential role of glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and glycine. Sleep Med. 2013 Aug;14(8):714–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fantini ML, Puligheddu M, Cicolin A. Sleep and violence. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2012;14(5):438–50. doi: 10.1007/s11940-012-0187-4. Epub 2012/08/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson EJ, Boeve BF, Silber MH. Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder: demographic, clinical and laboratory findings in 93 cases. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 2):331–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.2.331. Epub 2000/01/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarter SJ, StLouis EK, Boswell CL, et al. Injury in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.06.002. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schenck C, Hurwitz T, Mahowald M. REM sleep behavior disorder: an update on a series of 96 patients and a review of the world literature. J Sleep Res. 1993;2:224–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1993.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenck CH, Milner DM, Hurwitz TD, Bundlie SR, Mahowald MW. A polysomnographic and clinical report on sleep-related injury in 100 adult patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(9):1166–73. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.9.1166. Epub 1989/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross PT. REM behavior disorder causing bilateral subdural hematomas [abstract] Sleep Res. 1992;21:204. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyken ME, Lin-Dyken DC, Seaba P, Yamada T. Violent sleep-related behavior leading to subdural hemorrhage. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(3):318–21. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540270114028. Epub 1995/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarter SJ, St Louis EK, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia as an early manifestation of degenerative neurological disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12:182–192. doi: 10.1007/s11910-012-0253-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Vendette M, et al. Quantifying the risk of neurodegenerative disease in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2009;72:1296–1301. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000340980.19702.6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ, et al. Clinicopathologic correlations in 172 cases of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder with or without a coexisting neurologic disorder. Sleep Med. 2013;14:754–762. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenck CH, Boeve BF, Mahowald MW. Delayed emergence of a parkinsonian disorder or dementia in 81% of older men initially diagnosed with idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a 16-year update on a previously reported series. Sleep Med. 2013;14:744–748. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boot BP, Boeve BF, Roberts RO, et al. Probable REM sleep behavior disorder increases risk for mild cognitive impairment and Parkinson’s disease: a population-based study. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:49–56. doi: 10.1002/ana.22655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claassen DO, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Silber MH, Tippmann-Peikert M, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder preceding other aspects of synucleinopathies by up to half a century. Neurology. 2010;75:494–499. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7fac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell MJ. Parasomnias: an updated review. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(4):753–75. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0143-8. Epub 2012/09/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Tuineaig M, Bertrand JA, Latreille V, Desjardins C, Montplaisir JY. Antidepressants and REM sleep behavior disorder: isolated side effect or neurodegenerative signal? Sleep. 2013;36(11):1579–85. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gugger JJ, Wagner ML. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1833–41. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aurora RN, Zak RS, Maganti RK, et al. Best practice guide for the treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(1):85–95. Epub 2010/03/03. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarter SJ, Boswell CL, St Louis EK, et al. Treatment outcomes in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2013;14(3):237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunz D, Bes F. Melatonin effects in a patient with severe REM sleep behavior disorder: case report and theoretical considerations. Neuropsychobiology. 1997;36:211–214. doi: 10.1159/000119383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ. Melatonin for treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder in neurologic disorders: results in 14 patients. Sleep Med. 2003;4(4):281–4. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brzezinski A. Melatonin in humans. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:186–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701163360306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lack L, Wright H. The effect of evening bright light in delaying the circadian rhythms and lengthening the sleep of early morning awakening insomniacs. Sleep. 1993;16(5):436–43. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.5.436. Epub 1993/08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunz D, Schmitz S, Mahlberg R, Mohr A, Stöter C, Wolf KJ, Herrmann WM. A new concept for melatonin deficit: on pineal calcification and melatonin excretion. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:756–72. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00069-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeitzer JM, Duffy JF, Lockley SW, Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA. Plasma melatonin rhythms in young and older humans during sleep, sleep deprivation, and wake. Sleep. 2007;30(11):1437–43. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1437. Epub 2007/11/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iguichi H, Kato KI, Ibayashi H. Age-dependent reduction in serum melatonin concentrations in healthy human subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;55(1):27–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-55-1-27. Epub 1982/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dollins AB, Zhdanova IV, Wurtman RJ, Lynch HJ, Deng MH. Effect of inducing nocturnal serum melatonin concentrations in daytime on sleep, mood, body temperature, and performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(5):1824–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1824. Epub 1994/03/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunz D, Mahlberg R. A two-part, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of exogenous melatonin in REM sleep behaviour disorder. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(4):591–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00848.x. Epub 2010/06/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunz D, Bes F. Melatonin as a therapy in REM sleep behavior disorder patients: an open-labeled pilot study on the possible influence of melatonin on REM-sleep regulation. Mov Disord. 1999;14(3):507–11. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199905)14:3<507::aid-mds1021>3.0.co;2-8. Epub 1999/05/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kunz D. Melatonin in rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: why does it work? Sleep Med. 2013;14(8):705–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.05.004. Epub 2013/07/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeuchi N, Uchimura N, Hashizume Y, et al. Melatonin therapy for REM sleep behavior disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;55(3):267–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00854.x. Epub 2001/06/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CM, Chiu RNMSHY, Guilleminault C. Melatonin and REM behavior disorder. J Sleep Disorders Ther. 2013;2:118. doi: 10.4172/2167-0277.1000118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reijnders JS, Ehrt U, Weber WE, Aarsland D, Leentjens AF. A systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(2):183–9. doi: 10.1002/mds.21803. quiz 313. Epub 2007/11/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. Jama. 2002;288(12):1475–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. Epub 2002/09/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winkelman JW, James L. Serotonergic antidepressants are associated with REM sleep without atonia. Sleep. 2004;27(2):317–321. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seabra ML, Bignotto M, Pinto LR, Jr, Tufik S. Randomized, double-blind clinical trial, controlled with placebo, of the toxicology of chronic melatonin treatment. J Pineal Res. 2000;29(4):193–200. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0633.2002.290401.x. Epub 2000/11/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellis CM, Lemmens G, Parkes JD. Melatonin and insomnia. J Sleep Res. 1996;5(1):61–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1996.00003.x. Epub 1996/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kunz D, Mahlberg R, Muller C, Tilmann A, Bes F, et al. Melatonin in patients with reduced REM sleep duration: two randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(1):128–134. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Attenburrow MEJ, Cowen PH, Sharpley AJ. Low dose melatonin improves sleep in healthy middle-aged subjects. Psychopharmacology. 1996;126:179–181. doi: 10.1007/BF02246354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brooks PL, Peever JH. Impaired GABA and glycine transmission triggers cardinal features of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31(19):7111–7121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0347-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karczmar AG, Longo VG, Scotti de Carolis A. A pharmacological model of paradoxical sleep: the role of cholinergic and monoamine systems. Physiol Behav. 1970;5:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(70)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillin CJ, Sitaram N. Editorial: Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep: cholinergic mechanisms. Psycholocial Medicine. 1984;14:501–506. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700015099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowers MB, Goodman E, Sim VM. Some behavioral changes in man following anticholinesterase administration. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1964;138:383–389. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ringman J, Simmons J. Treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder with donepezil: a report of three cases. Neurology. 2000;55:870–871. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.6.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Almeida-Paula LD, Costa-Lotufo LV, Ferreira ZS, Monteiro AEG, Isoldi MC, Godinho RO, Markus RP. Melatonin modulates rat myotube-acetylcholine receptors by inhibiting calmodulin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;525:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markus RP, Silva CLM, Franco DG, Barbosa EM, Ferreira ZS. Is modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by melatonin relavent for therapy with cholinergic drugs? Pharmacol Therapeut. 2010;126:251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benitez-King G. Melatonin as a cytoskeletal modulator: implications for cell physiology and disease. J Pineal Res. 2006;40:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buharalioglu CK, Akar F. The reactivivity of serotonin, acetylcholine and KCL-induced contractions to relaxant agents in the rat gastric fundus. Pharmacol Res. 2002;45:325–331. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2002.0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Velarde E, Delgado MJ, Alonso-Gomez AL. Serotonin induced contraction in isolated intestine from a teleost fish (Carassius auratus): characterization and interactions with melatonin. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:364–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wappler F, Scholz J, von Richthofen V, Fiege M, Kochling A, Lambrecht W, Schulte Am Esch J. Attenuation of serotonin-induced contractures in skeletal muscle from malignant hyperthermia-susceptible patients with dantrolene. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:1312–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.San L, Arranz B. Agomelatine: a novel mechanism of antidepressant action involving the melatonergic and the serotonergic system. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;6:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bonakis A, Economou N, Papageorgiou S, Vaviakis E, Nanas S, Paparrigopoulos T. Agomelatine may improve REM sleep behavior disorder symptoms. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:732–735. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31826866f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nomura T, Kawase S, Watanabe Y, Nakashima K. Use of ramelteon for the treatment of secondary REM sleep behavior disorder. Intern Med. 2013;52:2123–2126. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.9179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fick D, Semla T, Beizer J, et al. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson KN, Shneerson JM. Drug Treatment of REM Sleep Behavior Disorder: the Use of Drug Therapies Other Than Clonazepam. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2009;5(3):235–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.St Louis EK. Truly “rational” polytherapy: maximizing efficacy and minimizing drug interactions, drug load, and adverse effects. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7(2):96–105. doi: 10.2174/157015909788848929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salzman B. Gait and Balance Disorders in Older Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(1):61–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morris ME, Iansek R, Matyas TA, Summers JJ. The Pathogenesis of Gait Hypokinesia in Parkinsons-Disease. Brain. 1994;117:1169–81. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.5.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klonapin® [package insert] San Fransisco, CA: Genentech USA, INC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Code of Federal Regulation, title 21, volume 9 [Internet]. FDA website. [cited 2013 Feb 3]. Available from: www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=1308.14

- 63.Schenck CH, Montplaisir JY, Frauscher B, et al. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: devising controlled active treatment studies for symptomatic and neuroprotective therapy-a consensus statement from the International Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder Study Group. Sleep Med. 2013;14(8):795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]