Abstract

Objective

To identify the most commonly-used patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures in clinical vestibular research, and assess their test characteristics and applicability to study age-related vestibular loss (ARVL) in clinical trials.

Data Sources

We performed a systematic review of the PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases from 1950 to August 13, 2013.

Study Selection

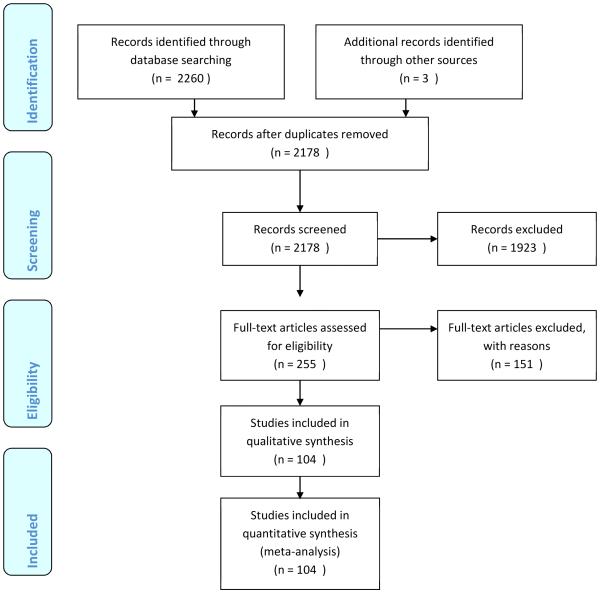

PRO measures were defined as outcomes that capture the subjective experience of the patient, such as symptoms, functional status, health perceptions, and quality of life. Two independent reviewers selected studies that used PRO measures in clinical vestibular research. Disparities were resolved with consensus between the reviewers. Of 2260 articles initially found on literature search, 255 full-text articles were retrieved for assessment. One-hundred and four studies met inclusion criteria for data collection.

Data Extraction

PRO measures were identified by two independent reviewers. The four most commonly used PROs were evaluated for their applicability to the condition of ARVL. Specifically, for these four PROs, data were collected pertaining to instrument test-retest reliability, item domains, and target population of the instrument.

Data Synthesis

A total of 50 PRO instruments were identified. The four most frequently utilized PROs were the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI), the Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale, the Vertigo Symptom Scale (VSS), and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). Of these four PROs, three were validated for use in patients with vestibular disease, and one was validated in community-dwelling older individuals with balance impairments. Items across the four PROs were categorized into three domains based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Activity, Participation, and Body Functions and Structures.

Conclusions

None of the most commonly-used PRO instruments were validated for use in community-dwelling older adults specifically with ARVL. Nevertheless, the three common domains of items identified across these four PRO instruments may be generalizable to older adults and provide a basis for developing a PRO instrument designed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions targeted to ARVL.

Keywords: vertigo, vestibular rehabilitation, outcome research, outcome measures, systematic review

Introduction

Definitions and Prevalence

Age-related vestibular loss (ARVL) is the reduction in vestibular function associated with the aging process. Studies suggest that ARVL is a prevalent condition among community-dwelling older adults, particularly in individuals over age 80.1,2 The 1-year prevalence of vestibular vertigo in 60-69 year olds and in adults 80 years or older was reported at 7.2 % and 8.8 % respectively.2 A study using data that assessed balance function using the modified Romberg test demonstrated 35 % of US adults 40 years or older had balance dysfunction.1 Age was positively associated with balance impairment, with a nearly 85% prevalence of balance dysfunction in adults age 80 years and older.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Features of ARVL

Older adults who are otherwise normal have been shown to have age-related decrease in vestibular response,3 but the pathophysiology of ARVL remains unclear, and ARVL does not appear to be due to a specific or known vestibular pathology.4 The main clinical features of ARVL include disequilibrium and dizziness, and ARVL has also been associated with an increased risk of falling.1,5 Very few studies have evaluated the potential for vestibular interventions to improve ARVL.6 Studies have largely focused on the benefit of vestibular interventions (e.g. vestibular rehabilitation) for specific vestibular diseases (e.g. Menière’s disease, vestibular neuritis, unilateral deafferentation).

Common Outcomes in Vestibular Research

Objective outcome measures of vestibular function typically include computerized dynamic posturography, electronystagmography, and angular vestibular-ocular reflex testing. However, studies suggest that these objective measures often do not concord with a patient’s subjective experience, and therefore may not fully capture the effect an intervention on the quality of life of the patient with vestibular impairment.7-9 The design of large-scale studies to evaluate the effectiveness of vestibular interventions for ARVL will require the identification of appropriate outcome measures validated for use for this specific condition (ARVL) and in this specific population (the elderly).

Patient-Reported Outcomes for Interventions

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are an increasingly used category of outcome measure in vestibular rehabilitation intervention studies. PROs are outcome measures that capture the subjective experience of the patient, independent of external interpretation by assessors such as a physician or therapist.10 Types of outcomes that are measured by PROs include symptoms, functional status, health perceptions, and quality of life (QOL).11 PROs may be especially valuable in patients with vestibular dysfunction, given that this disorder can manifest differently and have differential impact across individuals. Validated PRO instruments thus can be used to measure how vestibular disease is affecting the patient (i.e. a discriminative instrument that can help to differentiate patient groups, e.g. individuals with, versus without, the symptoms), and assess the effectiveness of vestibular interventions on the patient’s subjective experience (i.e. an evaluative instrument that is sensitive to changes in function following an intervention).12 In this study we focus on evaluative PRO instruments, given our longer-term goal of using such an instrument in an intervention trial.

Methods

To identify PROs that may potentially be used in studies of ARVL, we completed a systematic review of PRO instruments used in vestibular rehabilitation intervention studies. Vestibular rehabilitation (VR), given that it is one of the most-commonly prescribed vestibular interventions, was the intervention of interest. We selected the PROs that were utilized in over 10 clinical trials to assess the effectiveness of VR; there were four PROs that met this criterion. The most frequently applied PROs represent the common measures used to compare vestibular rehabilitation in clinical trials as an intervention. We then evaluated whether these PROs could be applied for clinical effectiveness research for the treatment of ARVL.

A literature search was performed using PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO electronic databases for publications up to August 13, 2013. “Vestibular rehabilitation” under parentheses was used as the search string. Two trained study team members independently reviewed all titles and abstracts, and selected articles for full article review based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were: 1) the authors conducted original research (i.e. not a review study), 2) the study population had vestibular disease, 3) vestibular rehabilitation was used as an intervention, 4) the study contained pre- and post-intervention measurements of outcomes, and 5) the outcome assessed was patient-reported, i.e. based on a patient’s subjective experience, elicited through questionnaires, scales, and/or grading systems. Exclusion criteria were: 1) case studies, 2) small case series (n<10), 3) non-English language citations, and 4) nonhuman studies. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by discussion between the two independent reviewers. Where disagreements could not be resolved through discussion, a third author provided input and the discrepancy was resolved through consensus. A reference check was completed by examination of citations of the articles included, as well as from relevant systematic reviews to ensure a thorough assessment of the literature.

The top four most heavily-cited PRO instruments with a frequency ≥ 10 articles using the outcome were identified. The most frequent PRO measures used in vestibular research likely represent outcomes that are thought to best assess the response of vestibular rehabilitation. Data from each of the four PRO instruments were abstracted, including number of items, methods used to develop the instrument, population in which instrument was validated, and test-retest reliability. Test-retest reliability broadly provides evidence of consistency, and therefore may be useful in determining if the PRO studied measures the true effect of the vestibular intervention. Content, construct, and criterion validity was reviewed independently and was undertaken based on original studies reporting the development and validation of each instrument. The unique items in all four PRO instruments were identified and categorized into underlying domains according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) published by the World Health Organization.13 The ICF provided a guide for organizing the PRO items into standardized categories. Our criteria for determining whether the PRO may be applicable for research in ARVL were: 1) did the process of item generation involve direct surveying of patients through unstructured, qualitative interviews, and 2) did the patients surveyed include older adults without a specific vestibular pathology (i.e. older adults with vestibular loss associated only with the normative aging process).

Results

Study Selection Process

The initial search (Figure 1) yielded 2260 articles, of which 85 were removed as duplicates. Analysis of references, including those from two systematic reviews,14,15 identified three additional articles.6,16,17 Screening of 2178 titles and abstracts led to the selection of 255 full-text articles for further assessment. Of these 255 articles, 104 were selected for final inclusion in the qualitative synthesis.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram.

PRO Instruments Employed in Vestibular Interventional Research

Fifty different vestibular-related PRO measures used in clinical trials of VR were identified from these 104 articles (Table 1). The four most commonly-cited PRO instruments were the 1) Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI; including one study that used the Brazilian version of the DHI), 2) the Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale, 3) the Vertigo Symptom Scale (VSS), and 4) the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). In the literature review, we identified a number of specific symptoms that were used as outcome measures, including dizziness, oscillopsia, and disequilibrium. When these single symptoms were grouped together they were the second most commonly-used PRO. However given that these symptoms represented a heterogeneous group of outcomes we did not consider symptoms as one of the four top PRO measures.

Table 1.

Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Measures in Vestibular Rehabilitation Clinical Effectiveness Research in Alphabetical Order

| PRO | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Activities-specific Balance Confidence | 14 |

| Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire | 3 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | 3 |

| Confidence in Everyday Activities Questionnaire | 1 |

| Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | 1 |

| Chambless Mobility Inventory | 1 |

| Composite Score | 1 |

| Dizziness Beliefs Questionnaire | 3 |

| Dizziness Factor Inventory | 1 |

| Dizziness Handicap Inventory | 57 |

| Diary Registration | 1 |

| Disability Rating Scale | 1 |

| Disability Score | 2 |

| European Quality of Life Questionnaire | 2 |

| Falls | 6 |

| Global Improvement Rate | 2 |

| Handicap | 1 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | 5 |

| Human Activity Profile | 1 |

| Hamilton Anxiety Scale | 1 |

| Modified Fatigue Impact Scale | 1 |

| Medical Short-form | 5 |

| Motion Sickness Questionnaire - Short form | 1 |

| Motor sensitivity | 2 |

| Patient Enabler Instrument | 1 |

| Perception of Dizziness Symptom | 3 |

| Perceived Outcome Scale | 1 |

| Patient Specific Functional Scale | 1 |

| Perceived Stress Scale | 1 |

| Questionnaire, customized | 3 |

| Quantification of dizziness | 2 |

| Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status | 1 |

| Rating Scale | 1 |

| Subjective Stability Evaluation | 1 |

| Symptom Severity Score (vertigo; dizziness; nausea; Mann's test; Stepping test; Hallpike manoeuvre |

1 |

| Symptom Outcome Score | 1 |

| Spielberger's Trait Anxiety Inventory | 5 |

| Symptoms | 16 |

| Tinetti Fall Risk | 1 |

| UCLA Dizziness Questionnaire | 2 |

| Vestibular Activities of Daily Living | 6 |

| Visual Analogue Scale | 21 |

| VAS for Anxiety | 2 |

| Vertigo Coping Questionnaire | 3 |

| Vertigo Dizziness Imbalance Questionnaire | 1 |

| Vertigo Handicap Questionnaire | 3 |

| VHT Test Battery | 3 |

| Vestibular Rehab Benefit Questionnaire | 1 |

| Vertigo Symptom Index | 4 |

| Vertigo Symptom Scale, short form | 15 |

Validation of PRO Instruments in Vestibular Rehabilitation

Development and validation of the four most common PRO instruments are detailed in Table 2.18-21 Two of the four PROs generated items for the instruments by directly interviewing and surveying patients (ABC, VSS). Three of the four PROs were developed in patients with specific vestibular disease across the age range (15-85 years) presenting to a neurology and neuro-otology clinic or for vestibular rehabilitation (DHI, VSS, and VAS). Only the ABC instrument was developed in community-dwelling older adults over age 65 with various levels of mobility impairment. None of these instruments were validated for use in community-dwelling older adults specifically with ARVL. None of the top four PROs met our criteria for being applicable as they are not validated in this population. Indeed, a review of the other 46 PROs identified in this systematic review indicated that none of the other PROs were validated in older patients specifically with ARVL either. All of the top four PROs demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability (0.85-1.00), which likely explained their widespread use. Another important psychometric property studied was responsiveness, a measure of clinically important difference. Responsiveness was reported in the DHI in subjects with a vestibular disorder with a minimal important difference score of 1.66, with a number needed to treat of 7.24 patients for detecting score change.12 The ABC in contrast was reported to have a ceiling effect where community-dwelling elderly adults over the age of 80 were less likely to have an improvement of balance confidence despite physical therapy. This ceiling effect likely contributed to the difficulty of establishing the responsiveness of the ABC.22 The other two PROs analyzed did not have responsiveness reported. The target population for each PRO instrument reflects the population in which the instrument was validated.

Table 2.

Top Four Most Commonly Used Patient-Related Outcomes for Research in Vestibular Rehabilitation

| Name of Measure |

Items | Development | Psychometric properties | Number of Studies Using Scale |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Development |

Methods used to develop instrument |

Population in which instrument was validated |

Target Population |

Test- retest reliability |

Content validity | Construct validity |

Criterion validity |

|||

| Dizziness Handicap Inventory |

25 | Jacobson and Newman (1990)19 |

Case history reports |

Initial instrument development: 25 males and 38 females (mean age 49 years, range 21- 82) with dizziness prior to vestibular testing; Instrument refinement: 40 males and 66 females (mean age 48 years, range 15- 85) with dizziness occasionally, frequently, or continuously |

Individuals with dizziness referred for vestibular testing |

0.97 | Bilateral peripheral vestibular loss is associated with lower self- perceived handicap in balance compared to individuals with balance problems but normal balance tests28 |

Negative correlation between DHI and ABC in the elderly (r=0.64; age range 26- 88 years)29 |

ABC (r=− 0.64)29 Short-form 36 health survey (SF- 36; r=0.53- 0.72)30 |

57 |

| Activities- specific Balance Confidence |

16 | Powell and Myers (1995)20 |

Interviews with physical and occupational therapists and patients |

17 males and 43 females over 65 years of age with high mobility (mean age 71 years) or low mobility (mean age 78 years) living in the community |

Older individuals with balance impairments |

0.92 | Assessed as part of development; physical and occupational therapists identified most important activities applicable to elderly persons |

Falls efficacy scale (r=−0.33) |

Physical self- efficacy (r=0.49) PANAS (r=0.12) |

14 |

| Vertigo Symptom Scale Short Form |

15 | Yardley et al

(1992)21 |

Patient interviews and literature review |

50 males and 77 females (mean age 46.5 years, range 18-80) with a complaint of vertigo presenting to a neurology neuro- otology clinic |

Individuals with vertigo referred to a neurology neuro- otology clinic |

0.89-0.98 | Not reported | Vestibular Rehabilitation Benefit Questionnaire (r=0.45) Vertigo Handicap Questionnaire (r=0.19-0.41)31 |

VSS and Beck Depression Inventory (r=0.55) Poor in VSS and SF-3632 |

14 |

| Vertigo Visual Analogue Scale |

9 | Kammerlind et al (2005)22 |

Based on pain visual analog scale |

26 males and 24 females (mean age 63 years, range 29- 85) with acute unilateral peripheral vestibular loss or central vestibular dysfunction presenting to a neurology or otolaryngology clinic |

Individuals with peripheral or central vestibular impairment |

0.85-0.96 | Not reported | DHI and VAS: r=0.67 DHI subscale and VAS33

|

Not reported |

26 |

Application of the Domains of the ICF on PRO Items

A total of 65 unique items were identified between the four PROs. We organized the items into three domains based on the ICF framework: 1) Activity, 2) Participation, and 3) Body Functions and Structures (including both physical and mental health functions) (Table 3). Activity items consist of the most basic self-care tasks required for independent living. These items are contained in the DHI and ABC scales. Other activity-related items consist of the tasks required for running a household and for limited travel within the community. These items are again mostly contained in the DHI and ABC scales. Of note, the ABC scale which is specifically designed for older populations contains several items not present in other scales, including “walking up or down a ramp,” “walking on icy sidewalks,” “standing on a chair and reaching for something,” and “getting into or out of a car.”

Table 3.

Comparison of Items in the Four Most Commonly Used Patient-Reported Instruments to Measure the Effectiveness of Vestibular Rehabilitation

| Domain | Measure | DHI | ABC | VSS | VAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item Inventory | 25 | 16 | 15 | 9 | |

| Activity | Difficult to walk around house/alone | X | X | ||

| Standing on chair and reaching for something or reaching overhead |

X | ||||

| Reaching at eye level or below | X | ||||

| Using an escalator holding the rail | X | ||||

| Using an escalator holding a parcel | X | ||||

| Using an elevator | X | ||||

| Walking up or down a ramp | X | ||||

| Walking on icy sidewalks | X | ||||

| Bending over | X | X | |||

| Getting into or out of a car | X | ||||

| Walking in open spaces | X | ||||

| Walking on uneven surfaces | X | ||||

| Walking on even surfaces or sidewalks | X | X | |||

| Restricts travel | X | ||||

| Being a passenger in a car | X | ||||

| Walking in crowds | X | X | |||

| Difficulty looking up | X | ||||

| Walking down grocery aisle | X | X | |||

| Difficult to walk in the dark at home | X | ||||

| Avoids heights | X | ||||

| Difficulty with quick movements | X | ||||

| Difficulty with turning over in bed | X | ||||

| Difficulty being under fluorescent lights | X | ||||

| Watching traffic at a busy intersection | X | ||||

| Walking over patterned floor | X | ||||

| Watching action TV | X | ||||

| Bumped by people while walking in crowd | X | ||||

| Walking up or down steps | X | ||||

| Difficulty getting into/out of bed | X | ||||

| Difficulty with homework/yard work/ heavy household chores |

X | X | |||

| Participation | Stress on relationships | X | |||

| Interferes with work | X | ||||

| Difficulty with sports, dancing, chores | X | ||||

| Difficulty reading | X | ||||

| Watching a movie at the theatre | X | ||||

| Restricts social activity | X | ||||

| Afraid to leave home independently | X | ||||

| Embarrassed in front of others | X | ||||

| Afraid of seeming intoxicated | X | ||||

| Afraid to stay home alone | X | ||||

| Body Functions and Structures |

Depressed | X | |||

| Frustration | X | ||||

| Difficulty concentrating | X | ||||

| Feels handicapped | X | ||||

| Vertigo < 20 min | X | ||||

| Vertigo > 20 min | X | ||||

| Nausea/vomiting | X | ||||

| Feeling dizzy, disoriented, “swimmy” lasting all day | X | ||||

| Unable to stand/walk without support or sway | X | ||||

| Feeling unsteady, about to lose balance, lasting < 20 min |

X | ||||

| Feeling unsteady, about to lose balance, lasting > 20 min |

X | ||||

| Feeling dizzy, disoriented, “swimmy” lasting < 20 min | X | ||||

| Chest pain | X | ||||

| Palpitations | X | ||||

| Headache/pressure in head | X | ||||

| Dyspnea | X | ||||

| Vomiting | X | ||||

| Diaphoresis | X | ||||

| Pre-syncopal symptoms | X |

Participation items represent those situations that individuals no longer participate in due to their vestibular impairment. These items include “restricts social activity,” and “afraid to leave home independently.” Many of these items are contained in the DHI and VAS. The final domain is Body Functions and Structures, and includes symptomatic features such as “nausea/vomiting,” “palpitations,” and “headache/pressure in head,” as well as mental health items, including “depressed,” “frustrated,” and “difficulty concentrating.” The physical items are largely drawn from the VSS, while the DHI additionally provides assessment on the mental health items.

Discussion

We reviewed the literature in order to identify PRO instruments that could be applied to research in older individuals with ARVL. Studies are increasingly suggesting that ARVL is a common condition in the elderly, akin to presbyopia (age-related vision loss) or presbycusis (age-related hearing loss). As interventions are being developed and tested to treat ARVL, there is a need for outcome measures that are validated for this condition and in this population. ARVL appears to differ from other vestibulopathies, in that it is not characterized by complete unilateral vestibular loss (as with acoustic neuromas or vestibular neuritis) but rather by a progressive partial bilateral vestibulopathy.23 As such, outcome measures will need to be sensitive to changes in partial levels of vestibular function. The four PROs studied in this review may not be appropriate in the ARVL population given the lack of validation in partial bilateral vestibulopathy subjects.

None of the top four PROs met our criteria for applicability to clinical trials research in ARVL, specifically instrument development from qualitative data collection in individuals with ARVL. The ABC was validated in the elderly, although it was not specifically validated for individuals with ARVL. The DHI, VSS and VADL were developed using patients with vestibular disease, but none of these three instruments focused on an elderly population. The body functions, activities and participation opportunities in older individuals differ from those of younger adults. Outcome measures that heavily weight the ability to carry out work-related activities or certain higher intensity leisure activities may not be appropriate for older populations. Moreover, responsiveness to change is a key criterion for evaluative instruments that can detect changes over time following interventions. Estimates of instrument responsiveness were only available for the DHI and ABC. However, responsiveness of the ABC was poor among individuals over age 80, and it is unclear whether the minimal important difference score reported for the DHI also holds for older individuals. Given the aging population, it is predicted the number of cases of ARVL will proportionally increase. To meet this demand, an outcome measure which is adapted for an older population is recommended to better capture the functional ability of the older individual with ARVL.24

The DHI has been studied in patients older than 65 years, and it has been found that the elderly reportedly have poorer balance-related disturbances from vestibular problems and lower self-perceived handicap compared to the younger population.25 Other psychometric properties including ceiling level, responsiveness, and sensitivity to aging of the PROs identified in this review were considered, but data on these characteristics are lacking (Table 2).

We focused our search specifically on PRO instruments, as these are increasingly being used in clinical research as a measure of the effectiveness of interventions in real-world settings. PRO measures provide direct assessment of the patient’s experience, which is what clinical interventions ultimately seek to improve. PRO measures have been shown to better reflect underlying health status than objective measures, and correlate well with important clinical outcomes including survival and patient satisfaction.26

Study Limitations

Limitations of this literature review are that outcome measures used to assess the effectiveness of vestibular rehabilitation only were evaluated. A search using a broader range of vestibular interventions yielded 804 full-text articles and was beyond the scope of this study. We also only evaluated the English published literature, and may have missed PRO instruments primarily developed and used in other languages, and in unpublished studies.

Conclusions

We provide a literature synthesis of the most commonly-used PRO instruments in clinical vestibular research. We found that the four most commonly-used PRO instruments that assess the effectiveness of VR were the DHI, ABC, VSS, and VAS, scales. None of these instruments were validated for use in community-dwelling older adults specifically with ARVL. The DHI, VSS, and VAS were all specifically validated in adult patients with suspected or confirmed vestibular impairment, and therefore should be applied to this population. Only the ABC focused on community-dwelling older individuals living in the community with different levels of mobility, although not specifically with ARVL. Nevertheless, the three common domains of items identified across the four PRO instruments may be instructive. These domains included Activity, Participation, and Body Functions and Structures.13,27 These domains may be generalizable to older adults and provide a basis for developing a PRO instrument designed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions targeted to ARVL. Future work is being directed to developing a PRO instrument that is applicable to older individuals with ARVL, starting with qualitative interviews with older individuals with ARVL. The goal will be to modify currently available PROs, or develop a new PRO instrument as needed. The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of this new PRO in individuals with ARVL will need to be established.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the American Otological Society Clinician-Scientist Award (Y.A.), and the NIA P30 Johns Hopkins Older Americans Independence Center Research Career Development Core (Y.A.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This material has not been presented elsewhere. This project was investigator-driven. We declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Eric Fong, Dr, Intern, Flinders Medical Centre, Bedford Park, South Australia 5042.

Carol Li, Division of Otology, Neurotology and Skull Base Surgery, Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Rebecca Aslakson, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 600 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21287.

Yuri Agrawal, Division of Otology, Neurotology and Skull Base Surgery, Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Della Santina CC, Schubert MC, Minor LB. Disorders of balance and vestibular function in US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001-2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009 May 25;169(10):938–44. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuhauser HK, von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, Feldmann M, Ziese T, et al. Epidemiology of vestibular vertigo: a neurotologic survey of the general population. Neurology. 2005 Sep 27;65(6):898–904. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000175987.59991.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baloh RW, Enrietto J, Jacobson KM, Lin A. Age-related changes in vestibular function: a longitudinal study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001 Oct;942:210–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baloh RW. Disequilibrium and gait disorders in older people. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2002;12(01):21–30. [cited 2002]; [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekvall Hansson E, Magnusson M. Vestibular asymmetry predicts falls among elderly patients with multi-sensory dizziness. BMC Geriatr. 2013 Jul 22;13(1):77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yardley L, Donovan-Hall M, Smith HE, Walsh BM, Mullee M, Bronstein AM. Effectiveness of primary care-based vestibular rehabilitation for chronic dizziness. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Oct 19;141(8):598–605. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris AE, Lutman ME, Yardley L. Measuring outcome from Vestibular Rehabilitation, Part I: Qualitative development of a new self-report measure. Int J Audiol. 2008 Apr;47(4):169–77. doi: 10.1080/14992020701843129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris AE, Lutman ME, Yardley L. Measuring outcome from vestibular rehabilitation, part II: refinement and validation of a new self-report measure. Int J Audiol. 2009 Jan;48(1):24–37. doi: 10.1080/14992020802314905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipp M, Longridge NS. Computerised dynamic posturography: its place in the evaluation of patients with dizziness and imbalance. J Otolaryngol. 1994 Jun;23(3):177–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valderas JM, Alonso J, Guyatt GH. Measuring patient-reported outcomes: moving from clinical trials into clinical practice. Med J Aust. 2008 Jul 21;189(2):93–4. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed S, Berzon RA, Revicki DA, Lenderking WR, Moinpour CM, Basch E, et al. The use of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) within comparative effectiveness research: implications for clinical practice and health care policy. Med Care. 2012 Dec;50(12):1060–70. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318268aaff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enloe LJ, Shields RK. Evaluation of Health-Related Quality of Life in Individuals With Vestibular Disease Using Disease-Specific and General Outcome Measures. Physical Therapy. 1997 Sep 1;77(9):890–903. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.9.890. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health O . ICF : International classification of functioning, disability and health / World Health Organization. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillier Susan L, McDonnell M. Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [serial on the Internet] 2011;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005397.pub3. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005397.pub3/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Porciuncula F, Johnson CC, Glickman LB. The effect of vestibular rehabilitation on adults with bilateral vestibular hypofunction: a systematic review. J Vestib Res. 2012;22(5-6):283–98. doi: 10.3233/VES-120464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen HS, Kimball KT, Jenkins HA. Factors affecting recovery after acoustic neuroma resection. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002 Dec;122(8):841–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Topuz O, Topuz B, Ardic FN, Sarhus M, Ogmen G, Ardic F. Efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation on chronic unilateral vestibular dysfunction. Clin Rehabil. 2004 Feb;18(1):76–83. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr704oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson GP, Newman CW. The development of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990 Apr;116(4):424–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1990.01870040046011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell LE, Myers AM. The Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995 Jan;50A(1):M28–34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.1.m28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yardley L, Masson E, Verschuur C, Haacke N, Luxon L. Symptoms, anxiety and handicap in dizzy patients: development of the vertigo symptom scale. J Psychosom Res. 1992 Dec;36(8):731–41. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90131-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kammerlind A-S, Larsson PB, Ledin T, Skargren E. Reliability of clinical balance tests and subjective ratings in dizziness and disequilibrium. Advances in Physiotherapy. 2005;7(3):96–107. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang TT, Wang WS. Comparison of three established measures of fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults: psychometric testing. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009 Oct;46(10):1313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paige GD. Senescence of human visual-vestibular interactions. 1. Vestibulo-ocular reflex and adaptive plasticity with aging. J Vestib Res. 1992;2(2):133–51. Summer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N. Otologic diagnoses in the elderly: current utilization and predicted workload increase. Laryngoscope. 2011 Jul;121(7):1504–7. doi: 10.1002/lary.21827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansson EE, Mansson NO, Hakansson A. Balance performance and self-perceived handicap among dizzy patients in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2005 Dec;23(4):215–20. doi: 10.1080/02813430500287299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basch E, Abernethy AP, Mullins CD, Reeve BB, Smith ML, Coons SJ, et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Dec 1;30(34):4249–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson GP, Calder JH. Self-perceived balance disability/handicap in the presence of bilateral peripheral vestibular system impairment. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000 Feb;11(2):76–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitney SL, Hudak MT, Marchetti GF. The activities-specific balance confidence scale and the dizziness handicap inventory: a comparison. J Vestib Res. 1999;9(4):253–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fielder H, Denholm SW, Lyons RA, Fielder CP. Measurement of health status in patients with vertigo. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1996 Apr;21(2):124–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1996.tb01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gloor-Juzi T, Kurre A, Straumann D, de Bruin ED. Translation and validation of the vertigo symptom scale into German: A cultural adaption to a wider German-speaking population. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2012;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanik B, Kulcu DG, Kurtais Y, Boynukalin S, Kurtarah H, Gokmen D. The reliability and validity of the Vertigo Symptom Scale and the Vertigo Dizziness Imbalance Questionnaires in a Turkish patient population with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Vestib Res. 2008;18(2-3):159–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dannenbaum E, Chilingaryan G, Fung J. Visual vertigo analogue scale: an assessment questionnaire for visual vertigo. J Vestib Res. 2011;21(3):153–9. doi: 10.3233/VES-2011-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]