Abstract

Inflammation plays a critical role in the development and progression of cancer, evident in multiple patient populations manifesting increased, non-resolving inflammation, such as inflammatory bowel disease, viral hepatitis and obesity. Given the complexity of both the inflammatory response and the process of oncogenesis, we utilize principles from the field of Translational Systems Biology to bridge the gap between basic mechanistic knowledge and clinical/epidemiologic data by integrating inflammation and oncogenesis within an agent-based model, the Inflammation and Cancer Agent-based Model (ICABM). The ICABM utilizes two previously published and clinically/epidemiologically validated mechanistic models to demonstrate the role of an increased inflammatory milieu on oncogenesis. Development of the ICABM required the creation of a generative hierarchy of the basic hallmarks of cancer to provide a foundation to ground the plethora of molecular and pathway components currently being studied. The ordering schema emphasizes the essential role of a fitness/selection frame shift to sub-organismal evolution as a basic property of cancer, where the generation of genetic instability as a negative effect for multicellular eukaryotic organ-isms represents the restoration of genetic plasticity used as an adaptive strategy by colonies of prokaryotic unicellular organisms. Simulations with the ICABM demonstrate that inflammation provides a functional environmental context that drives the shift to sub-organismal evolution, where increasingly inflammatory environments led to increasingly damaged genomes in microtumors (tumors below clinical detection size) and cancers. The flexibility of this platform readily facilitates tailoring the ICABM to specific cancers, their associated mechanisms and available epidemiological data. One clinical example of an epidemiological finding that could be investigated with this platform is the increased incidence of triple negative breast cancers in the premenopausal African–American population, which has been identified as having up-regulated of markers of inflammation. The fundamental nature of the ICABM suggests its usefulness as a base platform upon which additional molecular detail could be added as needed.

Keywords: Inflammation, Cancer, Evolution, Agent-based modeling, Computational biology, Systems biology

1. Introduction

There is an increasing awareness of a fundamental link between inflammation and cancer, with compelling epidemiological and mechanistic information to support this association [1–5]. Infectious diseases that lead to chronic, non-resolving inflammation, such as Hepatitis B and C, and Human Papilloma Virus, are known to promote the development of cancer [1–3]. Conditions associated with a chronic and recurring disordered inflammation, such as ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, are well known to predispose to cancer [1–3]. Obesity, which is increasingly recognized as a metabolically induced persistent inflammatory state, is associated with an overall increase in cancer incidence [1]. More recently, host–microbe interactions have been invoked as being a crucial factor in promoting an individual’s inflammatory state and correspondingly driving cancer risk [2,3]. Furthermore, pharmacological interventions that result in general suppression/reduction of inflammation, such as aspirin, have been demonstrated to reduce overall cancer incidence [6,7].

However, inflammation is such a protean and basic biological process that attempts to identify mechanistic links between inflammation and oncogenesis return a plethora of concurrent, parallel and ambiguous interactions [1–5]. For instance, the role of inflammation in cancer development and progression has been divided into two distinct, contradictory roles: a negative role in promoting the generation of genetic instability that can lead to cancer [8] and a positive role in being able to defend against invasion of the developed tumor [9]. However, this Janus-faced view of inflammation is not limited to its role in cancer development and progression; rather it is a fundamental property of the intersection between inflammation and disease [10,11]. Translational Systems Biology (TSB), which is the use of dynamic computational modeling to bridge the gap between mechanistic knowledge generated at the basic science level and observations and data generated at the clinical and population level, was initially developed to examine the protean and paradoxical nature of inflammation [12]; we now apply the concepts of TSB to the study of the intersection between inflammation and cancer.

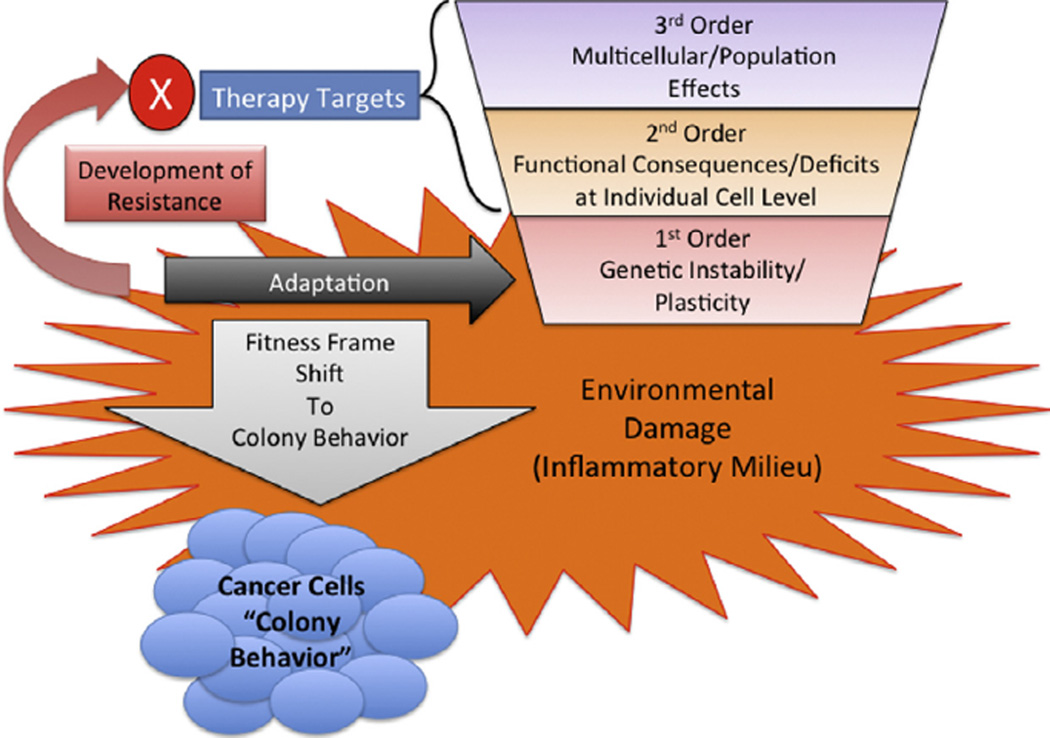

We turn to the issue of oncogenesis and the subsequent behavior of developed cancers. Hanahan and Weinberg have previously listed six hallmarks of cancer: (1) Sustaining proliferative signaling, (2) Evading growth suppression, (3) Resisting cell death, (4) Enabling replicative immortality, (5) Activating invasion and metastases and (6) Inducing angiogenesis [5,13]. These factors can be further grouped into those concerning intrinsic properties of cancer cells, resulting from a fundamental change in their internal programming (Hallmarks 1–4) and those related to a macrophenomenon associated with a population of cancer cells, i.e. the tumor (Hallmarks 5 and 6) [1]. We further refine this categorization by establishing a hierarchy of functional relationships and generative dependencies between these properties to better identify fundamental driving principles in oncogenesis (see Fig. 1):

1st Order Process: Promotion of Genetic instability/plasticity. This process refers to genetic damage, manifest as DNA base pair alterations, that accumulates for each individual cell. When the genetic damage is greater than the cell’s repair/response capabilities, this damage can propagate generationally as the damaged cell divides. Note that this process represents changes in the DNA sequence, and not just the regulation of the gene expression network. Therefore, alterations due to gene instability/plasticity represent a more fundamental disturbance to the function of a gene than epigenetic or signaling/regulatory.

2nd Order Process: Functional Deficits manifest at the individual cell level. These functional properties reflected in the behavior of individual cells fall into the general category of Hallmarks 1–4: promoting proliferation (either stimulating proliferation or loss of proliferation suppression), loss of mortality (dysfunction of telomerase, impairment of apoptosis), impaired damage repair (leading to increased genotypic plasticity), loss of migration inhibition (leading to failure of multicellular tissue ordering/structure and acquisition of invasiveness, as seen resulting from epithelial–mesenchymal transition). These are the functional consequences of the genetic disturbances happening at the 1st Order level, and constitute the loss of evolutionarily generated control structures required to maintain the integrity of multicellular organisms. The loss of these control functions represents a shift of active and relevant evolutionary fitness/selection from the entire organism to a sub-organismal level (see Discussion).

3rd Order Process: Multicellular effects evident in the behavior of the tumors as a population of cells. These properties generally correlate to Hallmarks 5 and 6, and include: promoting angiogenesis, interactions with the stromal microenvironment, immune evasion, and release of potentially metastatic cells Signaling events between tumor cells and surrounding normal tissue primarily drive these processes. Because they represent feedback between the tumor and normal tissue, many of these interactions represent hijacking of “normal” processes present in multicellular organisms, i.e. angiogenesis, tissue healing, prevention of anti-self immune responses.

Fig. 1.

The Generative Hierarchy for Cancer and the Effect of Inflammation. The Generative Hierarchy for cancer is depicted as an inverted trapezoid to reflect its process dependencies, and demonstrates how inflammation fosters a shift in the frame of evolutionary fitness and its impact on development of resistance to therapy. Inflammatory damage most heavily influences the 1st Order processes by fostering DNA-damage. While higher order effects of inflammation may be present (2nd Order signaling to increase proliferation, 3rd Order microenvironmental cues to promote angiogenesis), these processes are ultimately driven by cancer cells subjected to 1st Order disturbance (damage DNA/mutations). The increase in genetic instability/plasticity is manifest as adaptation at the 1st Order level, reflecting a shift to sub-organismal, prokaryote-like colony adaptive behavior. This accelerated adaptive cycle promotes the tumor’s development of resistance to therapeutic interventions, regardless of where in the Generative Hierarchy they are targeting the tumor.

The significance of this categorization structure is that lower order processes drive and generate the higher order processes. For instance, 2nd Order functional abnormalities result from 1st Order disturbances that disrupt genetic control structures; 3rd Order processes result from the intersection between disordered cells manifesting 2nd Order abnormalities. Therefore, focusing initial characterization of the role of inflammation in oncogenesis on the generation of genetic instability provides a fundamental grounding for the subsequent addition of more specific detail.

Given this classification system, we focus on the mechanisms of generating the genetic damage underlying 1st Order oncogenic processes as the foundational step in the behavior of potential cancer cells. The accumulation of genetic damage, manifest as mutations that propagate in successive generations, are a function of an inability of cellular mechanisms responsible for repairing damaged DNA to keep up with the damage that is generated. In short, cancer potential is present when DNA damage > DNA repair/response. Genetic damage leads to genetic instability/plasticity, which affects the subsequent behavior of a developed tumor. We assert that the critical point in this process is a shift in the frame of evolutionary fitness, where the active frame of reference for evolutionary fitness shifts from the aggregate multicellular organism to its component cells. Specifically, evolutionary processes that traditionally manifest primarily at the organismal generational level (i.e. the reproduction of the complete organism) now become highly relevant at the intra-generational sub-organismal level (i.e. the replication of the organism’s constituent cells): the genetic instability in somatic cells that proves detrimental to the maintenance of multicellular organization and function becomes the genetic plasticity used as an adaptive strategy as seen in colonies of prokaryotic unicellular organisms. This shift in the fitness frame of reference means that attempts to control cancer need to account for robust evolutionary processes operating at the individual cellular level.

Inflammation, by driving damage (mutagenicity), can be considered a fundamental mechanism that drives 1st Order oncogenic processes. We posit that being able to tractably understand the myriad effects of inflammation on cancer requires addressing these most fundamental aspects of the intersection between inflammation and cancer, and that computational and mathematical modeling can provide an investigatory framework that allows the contextualization of increased molecular detail in an ordered and logical fashion.

Computational modeling utilized as a pathway to theory (as opposed to the creation of detailed simulacrums of constrained and limited aspects of biology) provides a scientific approach linked to the development of the physical sciences, where the discovery and use of powerful abstractions (i.e. theories) allow for a foundational basis upon which multiple phenomena can arise [12,14]. Applying this approach to the question of cancer leads to a recognition of the benefits of the generative ordering of the hallmarks of cancer as described above. This will create a logical, systematic and progressive investigatory strategy that will allow subsequent layering of detail through iterative refinement. We assert that given the myriad of pathways, genes, components and factors, this methodical strategy is the only way to ground the accumulating mechanistic molecular knowledge concerning inflammation and cancer. Towards this end, we introduce an agent-based model (ABM) that integrates previously developed and validated models of inflammation and oncogenesis, the Inflammation and Cancer Agent-based Model (ICABM), to demonstrate that persistent, non-resolving inflammation contributes to the development of increasingly disordered epithelial cells, leading to malignant transformation. This initial model will provide a basic framework upon which additional mechanistic detail can be added, and link oncogenic and inflammatory mechanisms with population-level, epidemiological data.

2. Model overview/methods

The current model, the Inflammation and Cancer Agent-based Model (ICABM) was developed in Netlogo, a software toolkit used for agent-based modeling [15]. The ICABM was produced by integrating two previously validated ABMs, one concerning oncogenesis [16] and the other inflammation [17–19]. We have previously demonstrated the efficacy of using the modular nature of ABMs to integrate previously validated models to investigate system-level behavior [19]. Each of these modules will be described separately, followed by a description of the combined model. For purposes of clarity, specific components of the ICABM will be noted in Courier font, to distinguish them from their corresponding biological terms. More detailed information about the structure and components of the ICABM can be found in Supplement 1.

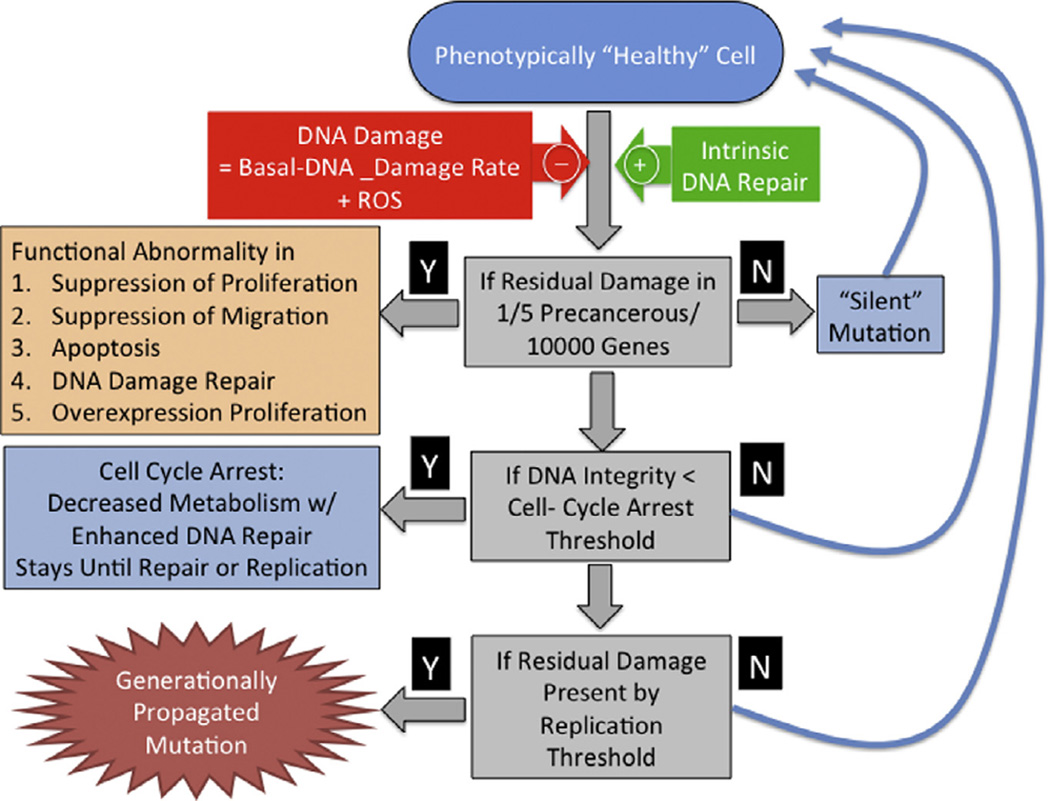

The Oncogenesis Module consists of an epithelial cell population generated by stem cells and maintained in a dynamically stable population. The basic model architecture was developed for the Duct Epithelial Agent-based Model (DEABM) to study the process of oncogenesis in breast tissue [16] and incorporated a core module driven by principles of accumulating tissue damage resulting from: (1) increased DNA damage or decreased DNA repair, (2) transferrable mutations in DNA repair, (3) inappropriate migration, (4) loss of limitation of replications and (5) dysregulated proliferation. The DEABM utilized an abstract genome in which designated gene locations were assigned to these specific functions associated with malignant transformation. DNA-damage, essentially representing DNA base pair alterations, occurred at each time step at a rate determined by the Basal-DNA-damage-rate, and rules concerning cellular repair and response were incorporated into the epithelial cell agents (epi-cells). Repair and response rules represent a range of effects, including activation of p53, induction of senescence and the triggering of apoptosis. If at the end of each time step the repair and response mechanisms were able to correct any damaged DNA, then no mutations were carried forward towards division. Alternatively, any residual damaged DNA present at time of division was passed on to daughter cells. If at any time the damaged DNA involved one of the specified oncogenic functions, then that function became impaired for that epithelial cell agent. It should be noted that the “functional” genes only represented a small subset of the entire abstract genome, therefore the vast majority of mutations were, given the level of abstraction of the DEABM and the ICABM, silent. However, this model architecture readily allows additional functions to be added: any new pathway introduced would be tied to the intact presence of its corresponding genes. This basic structure of the oncogenic portion of the DEABM was generalized in the current ICABM to reflect a generic epithelial tissue. The control logic of the Oncogenesis Module of the ICABM can be seen in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Control logic for the Oncogenesis Module. This figure demonstrates the control logic for the epi-cells in terms of their response to DNA-damage and how residual DNA-damage can manifest as pro-oncogenic functions and be propagated generationally. Note that the actual generation of an oncogenic function is statistically a rare event, and is likely to be associated with significant concurrent DNA-damage to currently “silent” gene functions. Future iterations of the ICABM will assign functions to these currently “silent” genes, producing a more comprehensive depiction of the various behaviors seen in malignant tumors.

Note that the development of a “cancer” requires multiple points of failure. In the case of the ICABM these potential points of failure are represented by the following abstract essential functions: (1) suppression of abnormal migration, (2) suppression of abnormal proliferation and (3) apoptosis. Note that these functions are cast as negative feedback controls, consistent with the identified cellular control architecture generated by evolution [20–22]. The loss of these normal functions leads to, respectively: invasiveness, unregulated growth and immortality. In addition to these criteria for cancer, the epithelial cell agents (epi-cells) also have the essential function of DNA-damage-repair; the loss of this function increases the accumulation of subsequent mutations. While the general structure of the oncogenic module of the ICABM implements rules representing the accumulation of somatic mutations, germline mutations can be simulated by reducing the base level of function of any of the functional genes represented; for instance this was done with the DEABM to simulate the effects of the BRCA1 mutation and Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (germline mutation of p53) in breast cancer populations [16]. Simulation experiments involved a series of simulations across a range of parameter values (parameter sweep) of Basal-DNA-damage-rate to identify the boundaries of plausible behavior for the Oncogenesis Module of the ICABM.

Also, since the goal is to be able to bridge the represented oncogenic mechanisms to a clinically and epidemiologically relevant context, we recognize that the generation of a single malignant cell does not represent the presence of a cancer and that there is a time gap before the malignant cell population reaches a size where it can be detected. Given improvements in surveillance and detection technologies, the detection threshold is continually evolving. We adopt the concept of “microtumors” to address this issue, predicated on the fact that there must be a period between the generation of the first invasive cancer cell and the point of clinical detection. To a great degree, this period of tumor growth prior to clinical detection is “oncological dark matter;” it is known to exist, has significant consequences, but cannot be seen (by definition). Existing population science cancer models generally use an abstracted exponential growth model (the Eden model [23]) as the basis for their tumor growth component [24]. If a point of oncogenesis is to be inferred, this mathematical function is extrapolated backwards in order to provide some general approximation. We adopt a similar approach in terms of the underlying assumption of a contiguous process from the onset of the first malignant cell, but with the capacity to represent more mechanistic detail. Since the detection threshold is highly variable based on the type of tumor and the fact that detection technologies are continually evolving, given the current generic nature of the ICABM we arbitrarily set the current threshold to <10 cancer cells.

The Inflammation Module of the ICABM is based on a previously published and validated ABM, the Innate Immune Response model (IIR) [18,19]. The basic structure of the IIR consists of an endothelial surface interacting with circulating inflammatory cells: polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), monocytes/macrophages, TH0, TH1 and TH2 subtypes, as well as both pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators. Injury to the endothelial surface leads to endothelial activation, activation of inflammatory cells in proximity, adhesion and migration of inflammatory cells, respiratory burst and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), recruitment of additional inflammatory cells and the phenotype shift from pro-inflammation to anti-inflammation with concurrent initiation of healing. The IIR was validated by reproducing the four possible general outcomes to injury (healing, forward feedback hyperinflammatory death, negative feedback immunoparalysis, and overwhelming injury), as well as replicating a series of anti-cytokine clinical trials and predicting previously unidentified cytokine trajectories in septic patients [18]. Additionally, the IIR was previously integrated with an ABM of epithelial tight junction metabolism and used to simulate multiple organ failure, its response to ventilator therapy and to predict the lung-injury properties of ischemic mesenteric lymph [19]. A reduced version of the IIR was used as the Inflammation Module for the ICABM, specifically to generate conditions of the non-resolving inflammation proposed as being critical in the development of cancers [2,4,11]. Additional information about agent rules can be found in Supplement 1.

As noted above, there are multiple possible intersection points between inflammation and oncogenesis. We utilize the concept of progressively developing a model from foundational principles (a process termed iterative refinement [14,25–28]), and focus on how non-resolving inflammation generates genetic instability as the 1st order process underlying the recognized hallmarks of cancer. The generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been invoked as the source of DNA damage arising from inflammation [1,2,4]. As such the ICABM uses the generation and effect of ROS integrate the Inflammation Module with the Oncogenesis Module and the Inflammation Module. Specifically, the ROS generated by the Inflammation Module provides an additional source of damage to the Basal-DNA-damage-rate within the Oncogenesis Module, where the Basal-DNA-damage-rate represents the background environmental carcinogenic risk (i.e. increased in terms of radiation and/or carcinogen exposure).

3. Simulation experiments

3.1. Oncogenesis Module

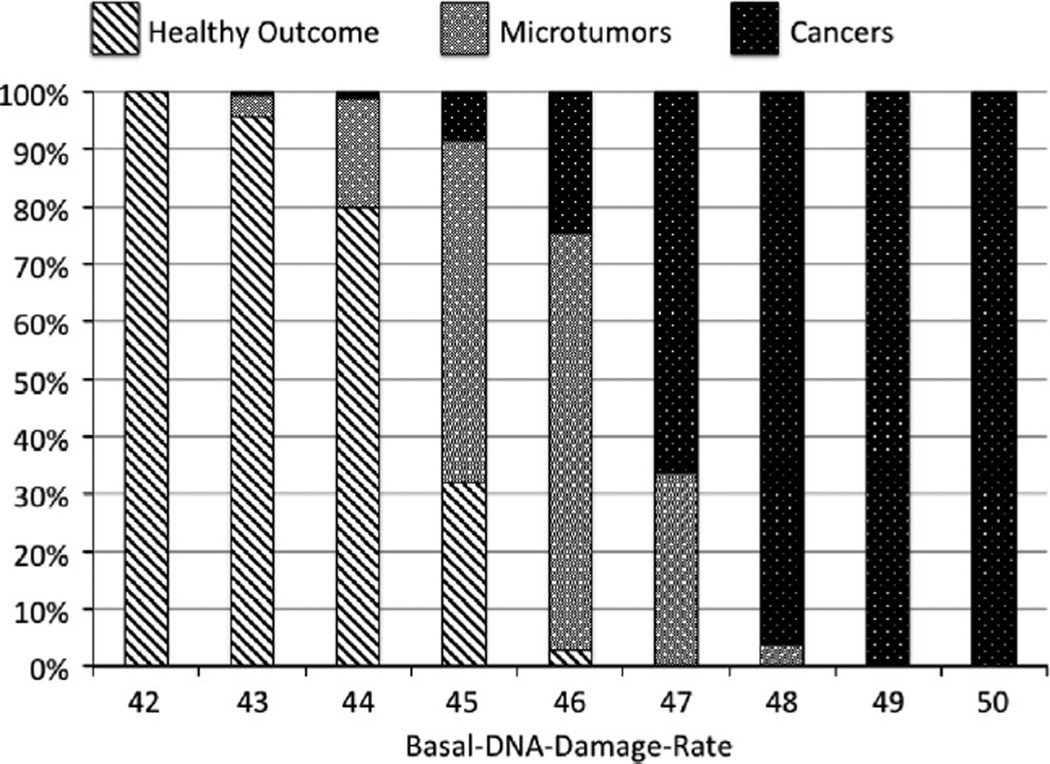

A parameter sweep of Basal-DNA-damage-rate identified the cancer incidence behavior space of the Oncogenesis Module. This was done in order to subsequently constrain parameter values for the module when it was integrated into the ICABM. Simulations were carried out simulating 60 years (the approximate number of years as an adult, i.e. age 15–75) with a parameter sweep of Basal-DNA-damage-rate values from 40 to 55 in increments of 1 (unit-less values). N = 500 runs were performed at each parameter value. ABM output was the number of cancers and microtumors (defined as <10 cancer cells at the end of the simulations run). Cancer cells were defined as epithelial cells that had mutations leading to: (1) Loss of suppression of migration, (2) Loss of suppression of proliferation or enhanced proliferation, and (3) Loss of apoptotic capacity. All 3 criteria needed to be met for a cell to be considered a cancer cell. As noted above the threshold defining a microtumor was arbitrarily set at <10 cancer cells. Additionally, if the cancer cell population exceeded 20 cells, then the simulation run was terminated. This was done for both computational efficiency and, given that the current ICABM does not incorporate 3rd order cancer processes, it is unable to depict cancer progression involving processes like angiogenesis and metastatic behavior.

3.2. Inflammation Module

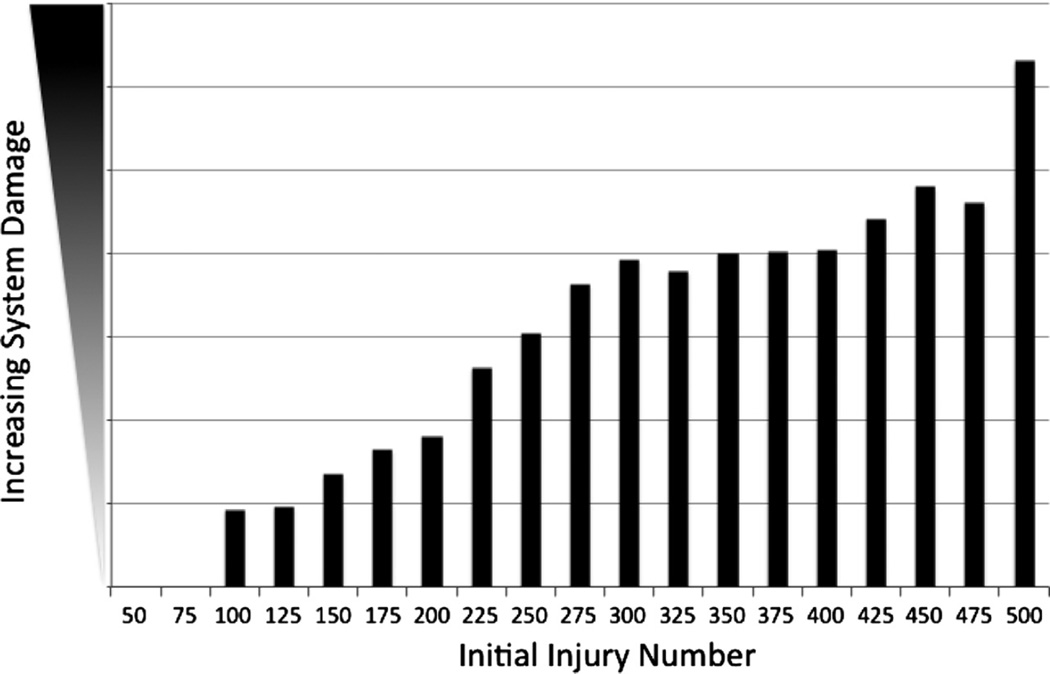

The primary role of the Inflammation Module of the ICABM is to generate a state of non-resolving inflammation to provide a potentially oncogenic milieu for the integrated ICABM. The original IIR ABM accomplished this in its replication of the immunoparalyzed multiple organ failure phenotype [18]. Calibrating simulations of the Inflammation Module of the ICABM focused on establishing a dose–response behavior space of persistent, non-resolving inflammation that could correspond to different basal levels of inflammation experienced by epithelial cells. A parameter sweep of an initiating level of system damage (initial injury number (IIN)) was performed to identify a range of behavior bounded by a lack of residual inflammation (defined as a resolution of all system damage) versus system “death” (defined as loss of >80% of total system health) [18]. The duration of each simulation was 3 months simulated time, a point identified where model behavior converged to a dynamically steady state, with n = 100 simulations per IIN value.

3.3. Integrated ICABM

Following integration of the Oncogenesis and Inflammation Modules of the ICABM, simulation experiments were performed to evaluate the contribution of persistent inflammation to oncogenesis and characterize the degree of disorder found in those generated tumors. For these simulations the Basal-DNA-damage-rate was selected at a level just below that associated with the generation of cancers, providing a baseline above which varying degrees of inflammation would increase the incidence of oncogenesis. Simulations were carried out across a range of IIN that generated persistent-non-resolving inflammation identified from the Inflammation Module simulations: 150–450 in increments of 50. Simulations were carried out for 60 years simulated time, n = 500 for each condition. Therefore, the data generated by this simulation corresponds to a population study of 7 conditions × 500 runs/condition = 3500 individuals. Output metrics were the incidence of cancers and microtumors, and the amount of accumulated DNA-damage seen in both microtumors and cancers. These latter two metrics are used as measures for the degree of genetic disruption/disorder seen in the simulated tumors.

4. Results

4.1. Simulation results from Oncogenesis Module

The parameter sweep of Basal-DNA-damage-rate demonstrated a lower bound of 42, below which no microtumors or cancers were generated, and an upper bound of 50, above which every simulation resulted in a cancer. The distribution of healthy, microtumors and cancers can be seen in Fig. 3. These simulations demonstrate a dose-dependent relationship between the degree of ongoing DNA damage and the generation of microtumors and cancer. There is an expected transition zone between healthy outcomes and cancer consisting of microtumors; as previously noted the threshold for defining a microtumor was arbitrarily set to be tumors with <10 cancer cells by the end of 60 years simulated time. In the future when the ICABM is applied to specific types of cancers different thresholds will be set based on the epidemiological behavior of those types of cancer, whether a microtumor-precancerous phenotype is known to exist, how such a tumor would be defined, and its prevalence/incidence in the population under study.

Fig. 3.

Generation of microtumors and cancers in the Oncogenesis Module. Results from a parameter sweep of Basal-DNA-damage-rate in the Oncogenesis Module alone (individual run = 60 years simulated time, n = 500). These results demonstrate a progression from healthy outcomes through microtumors to cancers that corresponded to increasing levels of baseline DNA damage. The lower bound of was determined at Basal-DNA-damage-rate of 42, at which and below no cancers or microtumors developed. The upper bound was seen to occur at Basal-DNA-damage-rate = 50, at which at and above all runs resulted in cancer (an implausible result). Note that since the definition of a microtumor was arbitrarily set at <10 cancer cells the width of this band is variable and tunable based on available clinical detection thresholds.

4.2. Simulations of Inflammation Module

The parameter sweep of IIN identified a range of persistent, non-resolving inflammation/system damage with a lower bound of 75, below which the system completely healed without residual system damage, and an upper bound of 500, at which level the system progressed to death (damage >80% total system health). These results are depicted in Fig. 4. The levels of sustained ROS across this same range of IIN are seen in Fig. 5, displaying progression in the level of ROS sustained by residual levels of damage, with a sharp inflection upward as the system progresses towards death (seen at IIN = 500). These behaviors reflect an intrinsic maintenance of ongoing inflammation due to the dynamic interactions of the system’s components, and would be consistent with clinical conditions manifesting with prolonged/persistent inflammation.

Fig. 4.

Demonstration of persistent and non-resolving inflammation in the Inflammation Module. Results from parameter sweep of Initial Injury Number (IIN) in the Inflammation Module in terms of total system damage remaining at the end of 3 months simulated time (n = 100). The lower bound of IIN was 75, at which and below which all simulation runs completely healed, and the upper bound of IIN was 500, where the system “died” by reaching total damage above 80% of total system health.

Fig. 5.

Demonstration of increased ROS in the Inflammation Module. Results from parameter sweep of Initial injury Number (IIN) in the Inflammation Module in terms of produced reactive oxygen species (ROS). The levels of persistent ROS qualitatively mirror the amount of total system damage seen in Fig. 6, though with a more pronounced upwards inflection at the point of system “death” IIN = 500.

4.3. Simulations of Integrated ICABM

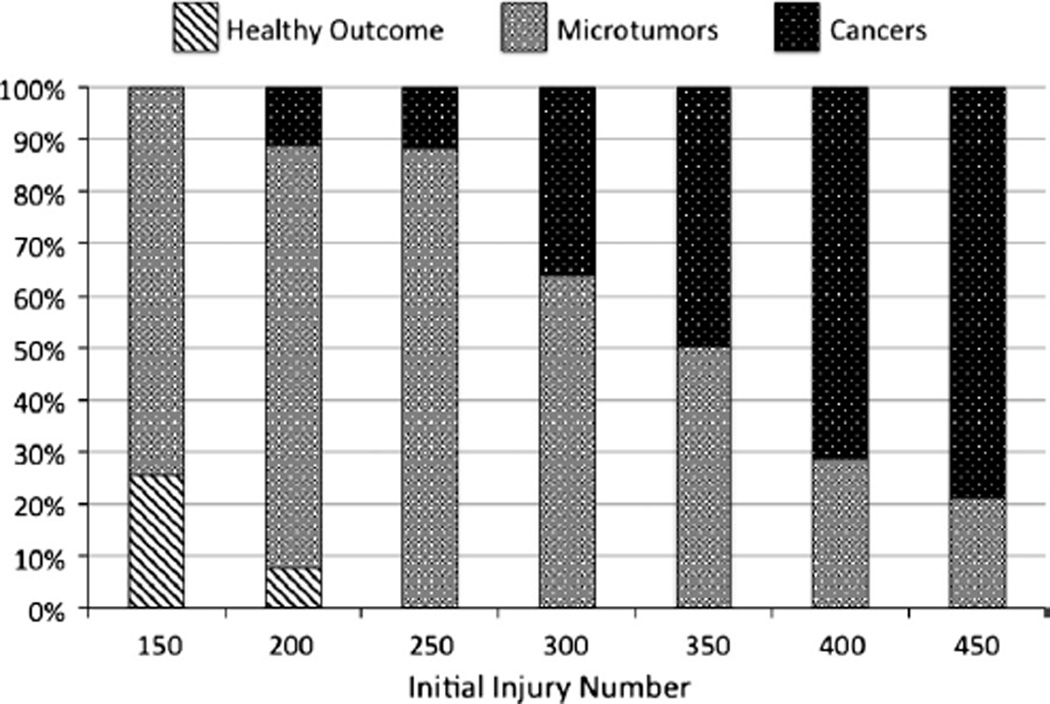

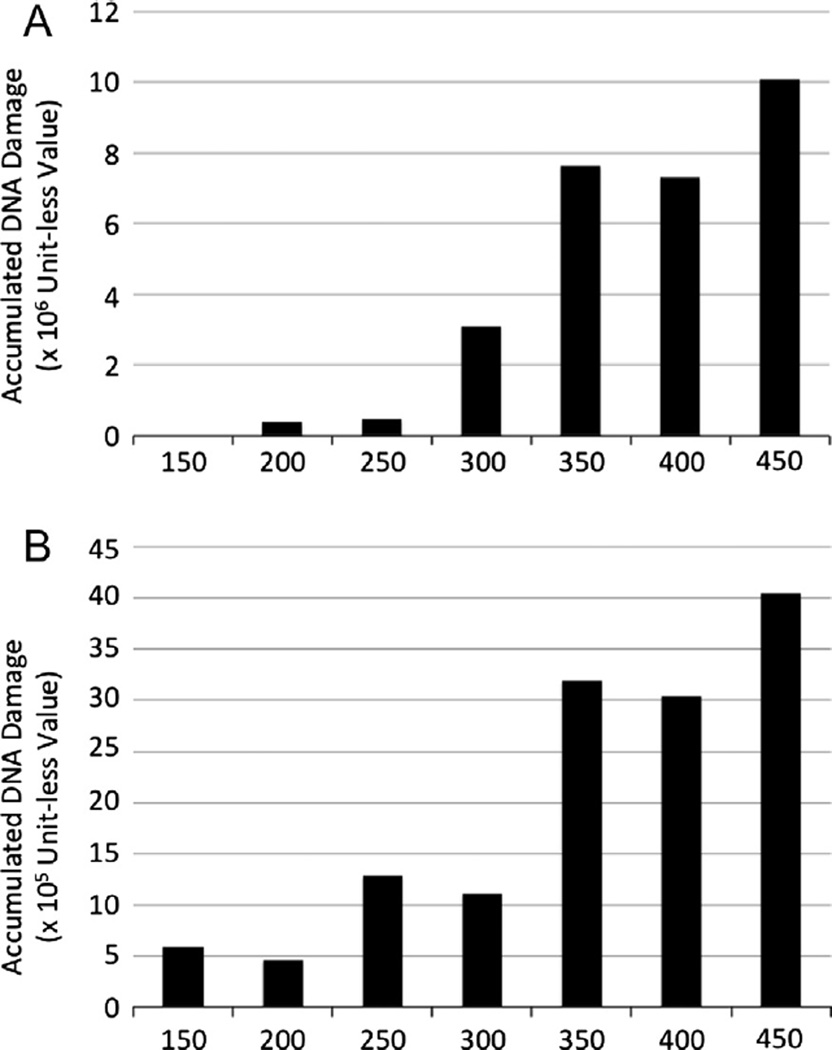

As noted in the description of the Simulation Experiments, the Basal-DNA-damage-rate for simulations with the integrated ICABM was chosen based on the inflection point at which tumors began to be generated. The rationale for this is to identify the contribution of inflammation on a minimal threshold basal state that represents a functionally benign background environment. This design feature of the ICABM allows a more carcinogenic environment to be simulated by increasing the background DNA damage level. Simulation experiments were performed at progressive IINs = 150–450 in increments of 50, a range identified as producing non-resolving persistent inflammation without that inflammation leading to system death (Fig. 4). The generation of microtumors and cancers in these simulations can be seen in Fig. 6. These data show an expected progression of increased tumor generation as IIN is increased. The transition zone of microtumors is also present, slightly more pronounced than in the simulations varying the Basal-DNA-damage-rate in the Oncogenesis Module alone. This is not surprising since the increased DNA-damage from the ROS is spatially limited to areas of unresolved damage and therefore would affect a more limited distribution of the epi-cell population in a fluctuating manner. Fig. 7A and B demonstrate the average amount of accumulated DNA-damage per generated cancer (Letter A) and microtumor (Letter B) across a range of background inflammation. Note that the scale of DNA-damage for the cancers is an order of magnitude greater for the cancers (×106) than the microtumors (×105), and that these values are per simulated tumor. There is a clear increase in the amount of DNA-damage present in tumors generated with higher levels of non-resolving inflammation. This confirms our hypothesis that increased ongoing DNA damage due to higher levels of persistent inflammation produces greater genetic instability among exposed epi-cells and results in more genetically damaged and disordered (as reflected by increased DNA-damage, representing base pair alterations) tumors.

Fig. 6.

Generation of microtumors and cancers in the combined ICABM. Results from a parameter sweep of IIN from 150 to 400 in the combined ICABM (individual run = 60 years simulated time, n = 500). These results demonstrate a progression from healthy outcomes through microtumors to cancers with increasing amounts of ROS generated with increasing IIN.

Fig. 7.

Degree of accumulated DNA-damage per tumor is greater in runs with greater inflammation. Letter A demonstrates the average amount of accumulated DNA-damage per aggregate cancer cell population for generated cancers and Letter B demonstrates the average amount of accumulated DNA-damage for generated microtumors. Note that the scale of DNA-damage for the cancers is an order of magnitude greater for the cancers (×106) than the microtumors (×105), and that these values are per simulated tumor. Even given the same mutation threshold to generate a malignant cell, by the time such cells are produced there is a clear increase in the amount of DNA-damage present in the tumors generated with higher levels of non-resolving inflammation.

5. Discussion

Inflammation, particularly non-resolving chronic inflammation, has been identified as influencing and affecting defined hallmarks of cancer [1–5,11]. However, inflammation is such basic fundamental process that it has multiple downstream effects, many of which provide further feedback and influence the resulting overall inflammatory/immunological state [10]. Each end product of inflammation has become a focus of intensive research, leading to highly detailed characterization of a specific process, but at the expense of contextualization. As a result the tendency is to treat each molecular/pathway intersection between inflammation and cancer as a distinct entity [1–5]. This research goal of identifying the “next gene or pathway” falls into the trap of infinite regress, where it is inevitable that there will be more components to be discovered. Furthermore, focusing on individual molecular components without understanding the foundational relationship between cancer and inflammation leads to temporizing solutions that are susceptible to subsequent failure (via evolution driven adaptation on the part of the cancer cells). We assert that the key to solving this persistent clinical and therapeutic dilemma requires a characterization of oncogenesis linked to biology’s primary theory, evolution.

Oncogenesis and evolution both require genetic instability/plasticity and selection based on fitness, and the development of tumors and their subsequent behavior (manifesting as aggressiveness, metastatic potential and development of drug resistance) can be considered as evolutionary processes. However, whereas evolution determines the characteristics of species is defined at the organismal level, oncogenesis can be seen as the manifestation of pro-evolutionary processes acting on component cells (overwhelmingly somatic) within a multi-cellular organism, where the increased inheritance of mutations within somatic tissue leads to an accumulating loss of evolutionarily developed control structures (loss of negative feedback mechanisms); note that this includes circumstances where there is a seemingly apparent increase in aggregate cellular function resulting from loss of inhibition (as is often the case of mutations in tumor suppressor genes). This behavior is consistent with the recognition that evolution has resulted, historically and phylogenetically, in the progressive acquisition of more and more control structures by the cells that make up multicellular organisms [20–22]. The loss of these control structures represents a shift in the frame of evolutionary selection from the traditional level of species-centric evolution (i.e. reproductive fitness of the entire organism), to a sub-organismal level defined by the replication of individual cells. The loss of cellular control structures that provide for multicellular organization represents a transition from cellular behavior constrained by the need to maintain multicellular organization to colony-based, single cell behavior characteristic of prokaryotic organisms. This fact is readily apparent by noting the primary defining characteristics of cancers, i.e. less regulated growth and increased mutability, are consistent with the behavior of prokaryotes, which contain gene-modification strategies such as high-mutation regions of their genome and horizontal-gene transfer with plasmids. As such “cancer” is only a feature of multi-cellular organisms, representing a shift in the frame of evolutionary fitness from the aggregated eukaryotic multi-cellular organism to unicellular actors with a prokaryote-like colony-oriented survival strategy utilizing genotypic plasticity. This plasticity can generate colony (tumor) members with increased aggressiveness (due to loss of motility inhibition) and enhanced adaptation against environmental forcing functions (i.e. eradicative chemotherapy). Inflammation, by fundamentally promoting the dual aspects of damage and proliferation, drives this shift in the frame of evolutionary fitness from the multicellular organism to its component cells. This conceptual framework reconciles the dual aspects of the intersection between inflammation and cancer: (1) the generation of genetic instability at the point of oncogenesis [8] and (2) the avoidance of immune surveillance accomplished by developing tumors [9]. Initially, developing tumors bear resemblance to their tissue of origin, therefore they are not readily identified as non-self. However, with increasing disorder of the tumor cells, they eventually reach a point where they become recognized as a non-self invader [1]. The inflammatory milieu that leads to the genetic instability of the initial tumor will similarly affect the subsequent mutability (i.e. genetic plasticity as an adaptive strategy) of that tumor. The ICABM demonstrates this effect through the increased number of accumulated mutations in generated tumors and microtumors under greater inflammatory conditions (Fig. 7). This cycle is further reinforced by the increasingly intensive inflammatory/immune responses against tumor cells that progressively become more disordered and move further and further away from “self,” paradoxically accelerated by therapeutic strategies intended to produce tumor necrosis (which is inherently inflammogenic). The implication of this mechanistic relationship between inflammation and cancer is that any potentially effective anti-tumor therapy that does not address reducing the inflammatory milieu is only a temporizing intervention, and highly dependent upon the degree of disorder present with the primary tumor arises (consistent with experience of biological determinism in cancer prognosis). Addressing this dilemma requires an investigatory platform that represents the appropriate evolutionary context for these oncogenic processes.

The analysis of such multi-layered dynamic interactions is critically enhanced through the use of computational and mathematical modeling. While there has been considerable prior work using mathematical models to investigate the interactions between the immune response and cancers, these prior investigations have focused on downstream effects between developed and established tumors and the immune system [29–37]. These studies include work on the immune response to tumor cells [33,37], processes of immune evasion [29,30,36], the facilitation of self-metastases by the immune system [31], the effect of the immune system on cancer stem cells in tumor growth [32], and investigations concerning the optimization and development of immunotherapy [34,35]. To our knowledge the ICABM is the first ABM that explicitly examines the role of inflammation in establishing an oncogenic environment and its effect on the development of cancer. The current ICABM is intended as an initial version of a scalable platform that can be expanded in the future to further investigate the interplay between inflammation and cancer. As such it is expectedly incomplete, and a non-comprehensive list of current imitations includes: (1) only ROS-as-damage as crosstalk between inflammation and oncogenesis, (2) no feedback from tumor growth on inflammatory signaling, (3) no pro-growth aspects of late inflammation, (4) no immune response to tumors, either in terms of immune killing of cancer cells or induction of additional inflammation by cancer cells, and (5) no 3rd Order characteristics of tumors such as angiogenesis and metastases. Greater detail about the feedback between the increasingly disordered tumor cells and their surrounding microenvironment will be necessary to capture the transition from the negative oncogenic aspects of inflammation to the protective immune response [10]. Furthermore, the simulation experiments demonstrate that the oncogenic environment is promoted by non-resolving inflammation, itself a dynamically stable state generated by the layered feedback architecture characterizing inflammation. We assert that only by representing the mutagenic environment (1st Order) in which a developed cancer will subsequently inhabit, can the higher order processes of functional cellular response (2nd Order) and macro-population tumor effects (3rd Order) be appropriately contextualized, evaluated and potentially targeted for intervention. This is particularly critical in the transition from the study of specific cellular and molecular mechanisms governing the behavior of cancer with the clinical and epidemiological data that defines cancer’s personal and public impact. Given the breadth of data and knowledge available at all these different levels, dynamic knowledge representation of the type provided by the ICABM can serve as a unifying platform in which the instantiation of mechanistic knowledge can be matched to, and evaluated against, population level data.

This ability to translate mechanistic knowledge into a clinical/epidemiological context is a fundamental aspect of Translational Systems Biology [12]. Towards this end, the goal of the ICABM is not to produce a comprehensive, detailed mechanistic simulacrum of a particular cancer type (as is the case in many detailed computational models of cancer [29–37]), rather it is to present a scalable foundational platform where varying levels of mechanistic detail can be added, but in a fashion that integrates with the techniques of population based modeling and analysis. For example, the natural history component of many epidemiological/population science models of cancer rely on a highly abstract exponential growth tumor growth model based on the Eden model [23]. This model is generally recognized as not reflecting the kinetics of tumor growth (reviewed in [38]) but nonetheless is sufficiently accurate to be used to model tumor growth in many population science models [24]. The ICABM represents an evolutionary step in attempting to add the capability to add mechanistic detail to the component of such population disease/treatment models. This is particularly notable in the future study of what we have defined as “microtumors:” populations of invasive cancer cells smaller than the clinical detection threshold. These tumors represent “oncological dark matter,” as by definition while they must exist they cannot be seen, and therefore cannot be studied clinically. The very early biology and natural history of cancers is highly clinically significant, with numerous implications related to balancing the benefits of surveillance and early detection with the risks and consequences of over-treatment. This phase of cancer biology can only be studied at the preclinical, basic science level, where mechanisms of spontaneous regression, immune suppression, and microenvironmental factors affecting 3rd Order processes can be examined at a detailed cellular-molecular level. We assert that models with the capacity to represent dynamically represent these mechanisms while being able to generate contextualizing epidemiological data, such as the ICABM, are necessary in order to translate preclinical knowledge into actionable clinical practice.

One concrete example of future use of the ICABM to bridge cancer mechanism with epidemiological data is in the study of breast cancer in premenopausal African American women [39]. These women have an increased incidence of triple negative breast cancers (Estrogen receptor (ER)-, Progesterone receptor (PR)- and HER-2 (−)), which are characteristically more disordered or poorly differentiated tumors, have a high proliferative rate, and have a high incidence of local and distant recurrence compared to those expressing intact receptors [40]. African Americans have also been identified as having up-regulation of markers of ongoing inflammation, specifically C-reactive protein [40,41]. Current simulations of the ICABM provide a fundamental mechanism by which this population-level observation can be explained: inflammation driving genetic instability/plasticity as a 1st Order oncogenic effect. The fact that a model as basic and abstract as the current ICABM provides a mechanistic explanation for such epidemiological data reinforces the fundamental nature of the proposed mechanism, and thus provides a mechanistic foundation upon which more molecular detail could be layered as needed. We hope that the introduction of the ICABM as a knowledge integration and representation platform will aid cancer researchers in contextualizing their focused research efforts, and aid in the identification of basic and fundamental insights that will advance the search for robust solutions to cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health, Grants NIGMS P50GM53789 and NIDDK P30DK42086.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mbs.2014.07.009.

References

- 1.Trinchieri G. Cancer and inflammation: an old intuition with rapidly evolving new concepts. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:677–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elinav E, et al. Inflammation-induced cancer: crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13(11):759–771. doi: 10.1038/nrc3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Inflammation and oncogenesis: a vicious connection. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2010;20(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Algra AM, Rothwell PM. Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):518–527. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothwell PM, et al. Short-term effects of daily aspirin on cancer incidence, mortality, and non-vascular death: analysis of the time course of risks and bene.ts in 51 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1602–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61720-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colotta F, et al. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(7):1073–1081. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zitvogel L, et al. The anticancer immune response: indispensable for therapeutic success? J Clin. Invest. 2008;118(6):1991–2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI35180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420(6917):846–852. doi: 10.1038/nature01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathan C, Ding A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vodovotz Y, et al. Translational systems biology of inflammation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4(4):e1000014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt CA, et al. At the biological modeling and simulation frontier. Pharm. Res. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9958-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilensky U. NetLogo, Center for Connected Learning. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University; 1999. < http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/>. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapa J, et al. Examining the pathogenesis of breast cancer using a novel agent-based model of mammary ductal epithelium dynamics. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An G. Agent-based computer simulation and sirs: building a bridge between basic science and clinical trials. Shock. 2001;16(4):266–273. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.An G. In silico experiments of existing and hypothetical cytokine-directed clinical trials using agent-based modeling. Crit. Care Med. 2004;32(10):2050–2060. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000139707.13729.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An G. Introduction of an agent-based multi-scale modular architecture for dynamic knowledge representation of acute inflammation. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2008;5(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Csete ME, Doyle JC. Reverse engineering of biological complexity. Science. 2002;295(5560):1664–1669. doi: 10.1126/science.1069981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doyle J, Csete M. Motifs, control, and stability. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(11):e392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle JC, Csete M. Architecture, constraints, and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(Suppl 3):15624–15630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103557108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eden M. 4th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematics and Probability. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1961. Proceedings of the 4th Berkely Symposium on Mathematics and Probability. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute, N.C. [cited 30.04.14];Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network: Breast Cancer Modeling. < http://cisnet.cancer.gov/breast/pro.les.html>.

- 25.Hunt CA, et al. Physiologically based synthetic models of hepatic disposition. J. Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2006;33(6):737–772. doi: 10.1007/s10928-006-9031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SH, et al. A computational approach to resolve cell level contributions to early glandular epithelial cancer progression. BMC Syst. Biol. 2009;3:122. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engelberg JA, et al. MDCK cystogenesis driven by cell stabilization within computational analogues. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7(4):e1002030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engelberg JA, Ropella GE, Hunt CA. Essential operating principles for tumor spheroid growth. BMC Syst. Biol. 2008;2:110. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-2-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkie KP, Hahnfeldt P. Tumor-immune dynamics regulated in the microenvironment inform the transient nature of immune-induced tumor dormancy. Cancer Res. 2013;73(12):3534–3544. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkie KP, Hahnfeldt P. Mathematical models of immune-induced cancer dormancy and the emergence of immune evasion. Interface Focus. 2013;3(4):20130010. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2013.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enderling H, Hlatky L, Hahnfeldt P. Immunoediting: evidence of the multifaceted role of the immune system in self-metastatic tumor growth. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2012;9:31. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hillen T, Enderling H, Hahnfeldt P. The tumor growth paradox and immune system-mediated selection for cancer stem cells. Bull. Math. Biol. 2013;75(1):161–184. doi: 10.1007/s11538-012-9798-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherratt JA, Nowak MA. Oncogenes, anti-oncogenes and the immune response to cancer: a mathematical model. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1992;248(1323):261–271. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ledzewicz U, Olumoye O, Schattler H. On optimal chemotherapy with a strongly targeted agent for a model of tumor-immune system interactions with generalized logistic growth. Math Biosci. Eng. 2013;10(3):787–802. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2013.10.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castiglione F, Piccoli B. Cancer immunotherapy, mathematical modeling and optimal control. J. Theor. Biol. 2007;247(4):723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Tameemi M, Chaplain M, d’Onofrio A. Evasion of tumours from the control of the immune system: consequences of brief encounters. Biol. Direct. 2012;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson-Tessi M, El-Kareh A, Goriely A. A mathematical model of tumor-immune interactions. J. Theor. Biol. 2012;294:56–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bru A, et al. The universal dynamics of tumor growth. Biophys. J. 2003;85(5):2948–2961. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74715-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carey LA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stead LA, et al. Triple-negative breast cancers are increased in black women regardless of age or body mass index. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(2):R18. doi: 10.1186/bcr2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reiner AP, et al. Genome-wide association and population genetic analysis of C-reactive protein in African American and Hispanic American women. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91(3):502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.