Abstract

Atherosclerotic lesions are often hypoxic and exhibit elevated lactate concentrations and local acidification of the extracellular fluids. The acidification may be a consequence of the abundant accumulation of lipid-scavenging macrophages in the lesions. Activated macrophages have a very high energy demand and they preferentially use glycolysis for ATP synthesis even under normoxic conditions, resulting in enhanced local generation and secretion of lactate and protons. In this review, we summarize our current understanding of the effects of acidic extracellular pH on three key players in atherogenesis: macrophages, apoB-containing lipoproteins, and HDL particles. Acidic extracellular pH enhances receptor-mediated phagocytosis and antigen presentation by macrophages and, importantly, triggers the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines from macrophages through activation of the inflammasome pathway. Acidity enhances the proteolytic, lipolytic, and oxidative modifications of LDL and other apoB-containing lipoproteins, and strongly increases their affinity for proteoglycans, and may thus have major effects on their retention and the ensuing cellular responses in the arterial intima. Finally, the decrease in the expression of ABCA1 at acidic pH may compromise cholesterol clearance from atherosclerotic lesions. Taken together, acidic extracellular pH amplifies the proatherogenic and proinflammatory processes involved in atherogenesis.

Keywords: apolipoproteins, high density lipoprotein, inflammation, low density lipoprotein, lipids/efflux, lipoproteins • macrophages/monocytes, phospholipases, proteoglycans, inflammasome

Atherosclerosis is a chronic disease of the inner layer of the arterial wall, the intima. The disease involves slow accumulation of lipoprotein-derived lipids into the intimal layer where they become modified and, as a result, trigger a maladaptive immune response characterized by infiltration of monocyte-derived macrophages into the arterial wall. Mature atherosclerotic lesions are gradually formed via chronic inflammation, tissue remodeling, smooth muscle cell proliferation, fibrosis, and calcification.

Some areas of the arterial tree are more prone to atherosclerosis than others, due to their relatively thick intima (1–3). One major factor explaining the relationship between intimal thickness and susceptibility to atherosclerosis is the absence of capillaries and lymphatics (4), which restricts the supply of oxygen and nutrition of intimal cells (5). Thus, hypoxia develops easily in the deep intima, and is further exacerbated by the additional increase in intimal thickness that occurs during atherogenesis (6, 7). Due to hypoxia, intimal cells become more dependent on glycolysis for energy production. Importantly, activated immune cells, including macrophages, favor energy production by glycolysis even in a normoxic environment (8). Similarly, proliferation of smooth muscle cells has been shown to involve stimulation of glycolysis (9). As cells with a glycolytic phenotype produce and secrete more protons than cells using oxidative phosphorylation, both aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis cause acidification of the extracellular fluid.

Indeed, acidic pH is found in various inflammatory sites (10–13), where local acidosis can affect the ongoing immune response (14, 15). The extrusion of intracellular protons is important for the activity of immune cells, because, by extruding excess intracellular acid, the cells not only protect themselves from intracellular acidification, but also deliver protons to the extracellular milieu to facilitate various cellular functions in a paracrine or autocrine fashion. For example, extrusion of intracellular protons allows sustained activity of NADPH oxidase, an enzyme present on the plasma membrane of phagocytes involved in mounting a key bactericidal response, the oxidative burst (16, 17). Acidosis greatly enhances the receptor-mediated uptake of opsonized bacteria into macrophages thereby promoting efficient clearance of an infection (18), and it also boosts antigen presentation by these cells via enhancing fluid-phase endocytosis and increasing the expression of molecules involved in antigen presentation (19, 20). Extracellular acidity is also needed for the hydrolytic activity of lysosomal enzymes secreted by the phagocytes, and thereby tends to augment the extracellular destruction of bacteria. By allowing the secreted lysosomal cathepsins to retain their activity, extracellular acidity also facilitates the movement of immune cells into the site of action (21).

Similar to other inflammatory sites, acidic extracellular pH is also found in atherosclerotic lesions. In the report by Naghavi et al. (22), pH values as low as 6.8 were measured using a microelectrode in the subendothelial areas of human carotid plaques, and differences as great as 1.0 pH units were noted within most plaques. In addition, visualization of the plaques with two pH-sensitive fluorescent dyes indicated that the pH may reach values even below 6. In this review, we describe results from various experimental settings providing strong supportive evidence that an acidic microenvironment in the arterial intima could have a direct role in atherogenesis. Importantly, in the context of atherosclerosis, many of the acidity-induced physiological cellular functions that have evolved to aid, e.g., in the killing of bacteria, become maladaptive and actually may aggravate atherogenesis, particularly by affecting several key elements of the intimal lipoprotein metabolism involved in the progression of atherosclerosis.

MECHANISMS OF LOCAL ACIDIFICATION IN ATHEROSCLEROTIC PLAQUES

Tissue hypoxia and acidification may be linked via enhancement of glycolytic cellular metabolism at the hypoxic areas. Hypoxic cells have been visualized in human carotid atherosclerotic lesions using the hypoxia marker pimonidazole that becomes reductively activated by intracellular redox enzymes at oxygen tensions ≤10 mmHg and forms adducts with thiol groups of proteins (23, 24). Immunohistochemical staining of the pimonidazole adducts showed strong hypoxia in macrophages near the deep intimal core regions of the lesions and, furthermore, the hypoxic macrophages colocalized with nuclear staining of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1α (HIF-1α), a major regulator of cellular response to hypoxia that induces, e.g., the metabolic switch to glycolysis (25). Consistent with the data from human lesions, hypoxia was detected in macrophages present in the lipid core region of advanced rabbit atherosclerotic plaques, and, moreover, high lactate levels were measured in the same areas indicating induction of glycolysis (26).

As stated above, several types of activated immune cells, including the macrophages abundant in atheromas, favor energy production by glycolysis even in a normoxic environment [reviewed in (8, 27)]. This phenomenon of aerobic glycolysis, known as the Warburg effect, was first described in cancer cells by the world-renowned biochemist Otto Warburg (28). Curiously, it seems that aerobic glycolysis is specifically upregulated by proinflammatory activation of immune cells, not by anti-inflammatory activation of immune cells; classically activated proinflammatory M1 macrophages and T helper cells display a glycolytic phenotype, whereas alternatively activated M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells with anti-inflammatory properties are characterized by enhanced oxidative phosphorylation (27). Basal metabolism in resting mouse peritoneal macrophages is predominantly glycolytic though metabolic flux is slow, and the rate of glycolytic flux is greatly increased by classical M1 type activation (LPS + IFN-γ) and innate activation (LPS or other TLR agonists alone), but not by alternative M2 type activation [interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13; IL-10] (31). The importance of HIF-1α and glycolysis in macrophage energy metabolism under normoxia is further highlighted by the drastic decrease in steady state ATP levels in HIF-1α-deficient macrophages (32) and by the marked increase in the expression of glycolytic enzymes during differentiation of human monocytes into macrophages (33). Similar to macrophages, proinflammatory activation of dendritic cells through toll-like receptors and of T lymphocytes through the T cell receptors triggers a HIF-1α-dependent increase in glycolytic metabolism (34, 35). The rationale behind the strong induction of aerobic glycolysis in activated macrophages and other immune cells most likely lies in the strong induction of various biosynthetic pathways and proliferation in these cells; glycolysis is not only a rapid source of ATP, but a high glycolytic rate also promotes accumulation of glycolytic intermediates that are mainly fed into the pentose phosphate pathway for the production of amino acids, nucleotides, and NADPH (8). Another possible rationale for glycolytic energy production is the compensation of a shift in mitochondrial function from production of ATP toward production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), which was recently shown to have an important role in macrophage bactericidal activity (36).

Taken together, levels of both anaerobic and aerobic glycolysis are likely to increase in the intimal cells during lesion development, resulting in increased production of lactate and H+. The excess H+ and lactate are secreted from the cells through the activity of several pumps, exchangers, and transporters, which locally decrease the extracellular pH (Fig. 1). Indeed, both increased lactate concentrations (26) and extracellular acidification (22) are observed in atherosclerotic lesions.

Fig. 1.

Enhanced glycolysis leads to extracellular acidification. After proinflammatory activation, macrophages produce energy predominantly through glycolysis in both hypoxic and normoxic conditions (the “Warburg effect”), which leads to the formation and secretion of lactate and H+ via the activity of various pumps, exchangers, and transporters located in the plasma membrane.

EFFECT OF LOCAL ACIDOSIS ON IMMUNE FUNCTIONS OF MACROPHAGES

It has been known for decades that macrophages are able to adapt to and survive the local acidosis that develops at acute inflammatory sites (37). Thus, macrophages, the most abundant immune cells in atherosclerotic lesions, will remain viable despite the acidic microenvironment of the atherosclerotic intima and are subject to acidosis-induced modulation of their immune functions. Of note, extracellular acidity also decreases the intracellular pH of macrophages (38), which greatly amplifies the number of pathways potentially modulated by extracellular acidosis. Because macrophages have a central role in triggering and maintaining the inflammatory reaction in the arterial wall throughout all stages of atherogenesis, any modification in their function would profoundly affect several mechanisms at play in lesion progression. Here, we focus on the effects of acidic extracellular pH on cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage (summarized in Fig. 2). For a review of the effects of pH on lymphocytes and neutrophils, we commend the excellent review by Lardner (14).

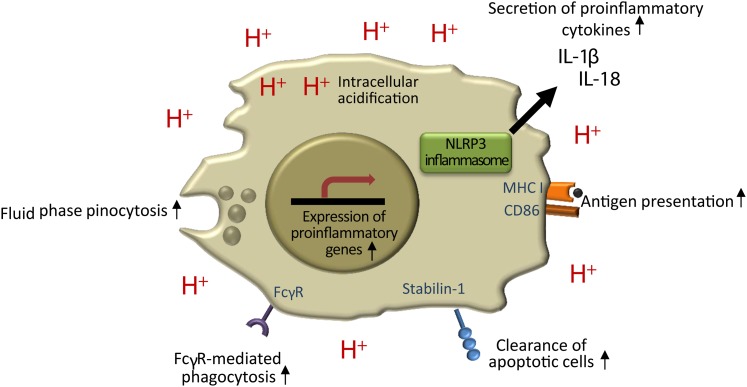

Fig. 2.

The effects of local extracellular acidity on macrophage immune functions. Acidic environment enhances fluid phase endocytosis, Fcγ-receptor-mediated phagocytosis, clearance of apoptotic cells, and antigen presentation. Extracellular acidity also activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, which results in the secretion of two potent proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and IL-18.

One of the central features emerging from studies of macrophages in acidic environments is the modulation of various cellular uptake mechanims by pH. At pH 6.5, the avidity of heat-aggregated human IgG immune complexes to monocyte and macrophage Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) was double that at pH 7.3 (39). Furthermore, preincubation of macrophages at pH 6.0 led to enhanced FcγR-mediated phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized latex beads and bacteria at pH 7.4 without increasing the binding of particles to the cell surface (18). Thus, exposure to an acidic environment enhances FcγR-mediated uptake both via increased binding to FcγR and via increased activity of the internalization machinery. In a recent study, expression of the phosphatidylserine receptor, stabilin-1, on macrophages was shown to be increased at pH 6.8, resulting in enhanced clearance of apoptotic cells (40). Finally, extracellular acidosis enhanced fluid phase endocytosis by macrophages and dendritic cells, accompanied by increased expression of molecules involved in antigen presentation, including major histocompatibility complex I and CD86 (19, 20).

Macrophage-generated ROS are an important component of the bactericidal activity of the cells; however, excessive ROS production may cause oxidative damage to the producing cell and its surroundings. Macrophage superoxide production in response to phorbol myristate acetate was decreased both by extracellular and intracellular acidosis (41, 42). On the other hand, acidic pH increases the rate of superoxide dismutation into hydrogen peroxide, and protonation of superoxide anions at acidic pH generates a species with increased reactivity (43). Regarding atherosclerosis, the net effect of the apparently two-way modulatory influences of extracellular acidosis on ROS production are reflected by increased iron-catalyzed extracellular LDL oxidation by macrophages, which could be explained by enhancement of the hydrogen peroxide-dependent Fenton reaction producing hydroxyl radicals (44). In addition to promoting oxidative modifications, acidic pH may also promote nitrosative damage, because an acidic environment induces the expression of the inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages, resulting in nitrite accumulation in the culture medium (45).

Activated macrophages secrete a plethora of proinflammatory cytokines and mediators that contribute to the inflammatory reaction in the atherosclerotic intima. Bellocq et al. (45) have shown that 2 h culture in medium adjusted to pH 7.0 activates nuclear factor (NF)-κB, the key inducer of proinflammatory cytokine expression in rat and mouse macrophages via a positive feedback loop of TNF-α secretion and autocrine signaling. In contrast, other studies have shown that low pH (pH 7.0–5.5) inhibits LPS-induced TNF-α secretion (mediated by NF-κB) in mouse and rabbit, but not in human macrophages (46–49). Accordingly, an inhibitory effect by low pH on LPS-induced NF-κB signaling was found in mouse, but not in human macrophages (46, 49). Differences in the study setups and the pH range used likely explain the contrasting results obtained in mouse macrophages. Human macrophages, based on Gerry and Leake (49), seem less sensitive to modulation of NF-κB activity by low pH, but more data on NF-κB target binding at a wider range of acidic pH values is required before firm conclusions can be made.

Recently, we and others have shown that acidic pH stimulates the secretion of the key proinflammatory and proatherogenic cytokine IL-1β in primary human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages (38, 50). IL-1β production is tightly regulated; the inactive procytokine, pro-IL-1β, is only expressed following specific stimulation, and cleavage of the procytokine by caspase-1 protease is required for biological activity. Monocytes constitutively express active caspase-1, and thus IL-1β is proteolytically activated and secreted immediately after induction of pro-IL-1β expression (51), as exemplified by acidic pH-induced pro-IL-1β expression and secretion (50). In contrast, caspase-1 in macrophages is in the inactive pro-form and, therefore, pro-IL-1β expression and caspase-1 activation are both required for secretion of mature IL-1β (51). We showed that extracellular acidity has no effect on pro-IL-1β expression in macrophages. However, when macrophages were stimulated with LPS to produce pro-IL-1β, extracellular pH 6.0–7.0 triggered activation of caspase-1 via the NLRP3 inflammasome and high-level secretion of mature IL-1β, as well as that of IL-18, another caspase-1 target cytokine (38). We also found synergy between low pH and cholesterol crystals, another activator of the NLRP3 inflammasome (52, 53), in induction of IL-1β secretion (38). Confirming the strong proinflammatory potential of acidic environment, a very recent microarray study compared macrophage gene expression at pH 7.4 and 6.8 and found 353 differentially expressed genes that showed marked enrichment of pathways related to inflammation and immune responses (54).

How might these changes in macrophage immune function relate to atherogenesis in the arterial wall? As discussed above, extracellular acidosis increases the FcγR-mediated uptake of immune complexes. Immune complexes of modified LDL and corresponding antibodies have been found in atheromas, and their uptake to macrophages via FcγRs triggers secretion of proinflammatory mediators and may enhance foam cell formation (55). Of note, acidosis also increases LDL oxidation by macrophages, potentially contributing to the pool of immunogenic modified LDL species in the lesions. On the other hand, enhancement of apoptotic cell clearance by macrophages at low pH may be a more anti-atherogenic effect. Importantly, low pH triggers the secretion of the potent proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and IL-18, in macrophages. For example, IL-1β increases the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells to attract more inflammatory cells into the lesion and IL-18 contributes to induction of highly proatherogenic IFN-γ in T cells (56). Low pH can also boost antigen presentation in macrophages and thus contribute to induction of adaptive immune responses in the lesions. Thus, acidosis promotes many key immune functions of macrophages with a predominantly proinflammatory effect. Although these effects may be beneficial for efficient clearance of acute inflammation, they seem maladaptive in the context of atherosclerosis. In atherosclerosis, the local inflammatory response develops mainly under sterile conditions and excessive unresolved inflammation promotes lesion development and instability of the plaques.

ACIDIC EXTRACELLULAR pH INCREASES THE RETENTION OF ATHEROGENIC LIPOPROTEINS

Atherosclerosis is characterized by the extra- and intracellular accumulation of lipoprotein-derived lipids. Low extracellular pH affects many of the processes involved in lipid accumulation (Fig. 3). Upon entering the subendothelial arterial intima, LDL particles encounter a dense extracellular matrix network rich in proteoglycans, collagen, and elastin, with which the LDL particles tend to interact. Especially important is the interaction with proteoglycans (57, 58), which initiates LDL retention in the intima (59, 60), particularly at the atherosclerosis-prone sites, where the proteoglycan composition favors the retention of apoB-containing lipoproteins (61, 62). In addition to LDL, other apoB-containing lipoproteins (chylomicron remnants, VLDL, and IDL) also bind to proteoglycans, albeit less tightly (63–65), and can therefore contribute to lipid accumulation in the intima (66). Recently, Mendelian randomization studies have provided strong supportive evidence for the causative roles of both LDL and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in the development of cardiovascular disease (67).

Fig. 3.

The effects of extracellular acidity on extracellular and intracellular cholesterol accumulation. Extracellular acidity enhances retention, modification, and aggregation of LDL, and so promotes both extra- and intracellular cholesterol accumulation. Extracellular acidity also remodels HDL particles with generation of preβ-HDL. However, in acidic environments, preβ-HDL is prone to degradation by acidic proteases. Moreover, acidity decreases the expression of the ABCA1 transporter and the secretion of apoE by macrophage foam cells, so decreasing cholesterol efflux from these cells.

The affinity of lipoproteins for proteoglycans is quite low at neutral pH, but acidic pH significantly enhances the binding of all three atherogenic apoB-100-containing lipoproteins (VLDL, IDL, and LDL) to human aortic proteoglycans (68, 69). The lipoprotein-proteoglycan interaction is mediated by certain positively charged sequences in apoB which contain lysine and arginine residues and negatively charged sulfate and carboxyl groups in the proteoglycan glycosaminoglycan chains. At acidic pH, additional sequences of apoB are likely to be important for the interaction: because the pKa of histidine side chains is ∼6.0, the positive charge of the histidine residues increases as the pH decreases around this pH, histidine residues of apoB-100 may also be involved in the interaction with proteoglycans. In contrast, the negative charge of the sulfate and carboxyl groups in the proteoglycans are unlikely to be affected by the degree of acidification found in the arterial intima, because they have a pKa of <2.0 and 3.02–4.37, respectively (70). Thus, the intimal acidity, even if reaching a pH value of 6, would not result in protonation of the sulfate and carboxyl groups, and the net negative charge of the proteoglycans will be preserved, thereby allowing interactions with positively charged lipoproteins and other molecules. Interestingly, proteoglycans may contribute to extracellular acidification, mediated by the attraction of H+ to their negatively charged sulfate and carboxyl groups (71). Although the negatively charged groups attract H+ ions and other cations, they do not bind the ions at the slightly acidic pH values present in the arterial intima. This can cause differences in the distribution of the ions and lower the pH in the vicinity of the proteoglycans.

Lipoproteins may be retained in the arterial intima also via bridging molecules, such as LPL (72–74). Thus, LPL binds to proteoglycans via ionic interactions of high affinity and to lipoproteins via hydrophobic interactions. There are no studies in which the effect of acidic pH has been studied on this bridging property of LPL. However, the binding of LPL to heparin is enhanced at mildly acidic pH values (75) and LPL is able to bind to lipid droplets at least at pH values as low as pH 6.5 (76). Together, these pieces of information suggest that acidic pH would most likely also enhance this type of lipoprotein retention in the arterial intima.

ACIDITY ENHANCES MODIFICATION OF apoB-CONTAINING LIPOPROTEINS

LDL particles isolated from atherosclerotic lesions show signs of various modifications, such as oxidation, proteolysis, and lipolysis, which are indicative of oxidative, proteolytic, and lipolytic enzyme activities in the lesions (77). Such modified LDL particles are often aggregated and/or fused into large lipid droplets. Acidic extracellular pH may increase lipoprotein modification (71, 78), which may in turn further decrease the extracellular pH (see below). Acidic proteases, such as cathepsins, are found extracellularly in normal and atherosclerotic intima, and they efficiently proteolyze apoB-100 leading to LDL particle fusion (79–81). Moreover, proteolysis of apoB-100 sensitizes the LDL particles to lipases, thereby promoting their lipolytic modification (82, 83). Interestingly, activated macrophages secrete cathepsins together with H+ ions and so, by acidifying their local microenvironment, provide optimal conditions for activity of these secreted proteases (84). Finally, when macrophages latch onto large aggregates of LDL, they create partially sealed compartments on the surface of these aggregates, drop the pH, and secrete lysosomal acid lipase (LAL). This enzyme then hydrolyzes the cholesteryl esters of the aggregated lipoproteins into unesterified cholesterol and fatty acids. Unesterified cholesterol can enter the cells and the fatty acids can further acidify the microenvironment (85, 86). This process is analogous to the way osteoclasts, macrophage-like cells, normally latch onto bone and degrade it through the formation of sealed compartments at low pH (85).

The free cholesterol generated from lipoproteins or other extracellular lipid deposits by the secreted acidic LAL may contribute to the nucleation and growth of cholesterol monohydrate crystals in the lesions. Large cholesterol crystals are easily visible by microscopic examination of atherosclerotic arteries, and they are a hallmark of advanced atheromas; however, smaller crystals are also found in about one third of intermediate lesions that lack necrotic cores (87, 88). Using a new microscopic technique, cholesterol microcrystals were detected in the aortic wall of apoE-deficient mice after just 2 weeks of high cholesterol diet, coinciding with the first appearance of macrophages (52). As discussed above, cholesterol crystals were recently shown to elicit an inflammatory response via the NLRP3 inflammasome, but the mechanisms of crystal nucleation in atherosclerotic lesions in vivo remain elusive. Electron microscopy of human atherosclerotic lesions has shown that cholesterol crystal growth occurs predominantly in the matrix-embedded extracellular lipid deposits of the deep arterial intima, whereas most macrophage foam cells reside in the more superficial intimal layer (89). Although less frequent, cholesterol crystals were also found inside macrophage foam cells in human lesions (89), and thus, the original site of crystal nucleation could not be defined with certainty. However, more recent in vitro studies have shown that cholesterol crystal nucleation can occur both within macrophage foam cells (87, 90–93) and on the surface of enzyme-modified LDL particles (94), of which the latter mechanism may indeed be amplified by secreted LAL in an acidic environment. Acidity may also directly affect cholesterol crystallization and the interaction of cholesterol crystals with each other, lipoproteins, or cell membranes (95–97).

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzymes hydrolyze sn-2 ester bonds in glycerophospholipids, yielding lysophospholipids and FFAs, which have been shown to have proinflammatory effects (98–102). In addition, as noted above, the FFAs may contribute to extracellular acidification. Several secreted PLA2 enzymes with different substrate specificities and lipolytic activities are present in human atherosclerotic arteries (98, 103, 104). PLA2-V is one of the enzymes that may modify lipoproteins in the intima (105, 106), and at acidic pH it is more active against lipoproteins (69). The activity of the PLA2s is largely determined by their ability to bind to substrate membranes (107, 108) and it is sensitive to changes in the lipid membrane induced, e.g., by acidic pH. The electric charge distribution at the membrane interface of zwitterionic phosphatidylcholine molecules is determined by interaction of the phosphate and amine groups with counterions, such as protons and hydroxide ions (109). At neutral pH, the lipid head groups associated with hydroxide ions are the predominant form, meaning a net negative charge, but the increased proton concentration of acidic pH tends to enhance the association of the protons with the head groups and so enhance their charge-neutral character (109, 110). This may enhance the interaction between LDL and PLA2-V and so explain the observed acidity-increased activity of PLA2 toward LDL (69). Acidity also affects the fate of the products of PLA2 activity. At neutral pH and physiological albumin concentration, most of the FFAs and lysophospholipids generated through PLA2-dependent hydrolysis of LDL particles are readily scavenged by albumin; however, at acidic pH the ability of albumin to bind the lipolytic products is decreased, and more of the lipolytic products remain in the LDL particles (111). This likely results from the property of albumin to preferentially bind the FFAs in their anionic form (112, 113); at acidic pH the FFAs are largely uncharged.

SMase hydrolyzes sphingomyelin on the surface of lipoprotein particles into ceramide and phosphocholine. Secretory SMase, a product of the acid SMase gene, is able, at neutral pH, to hydrolyze PLA2-digested and proteolyzed LDL or apoC-III-enriched LDL, as well as LDL extracted from human atheromata (82, 114). Digestion induced by secretory SMase is promoted at acidic pH (82, 114, 115). In vitro, SMase-modified LDL particles promptly aggregate, the aggregate size increasing by synergy with chondroitin-sulfate-rich proteoglycans and LPL (72). Aggregate size after SMase digestion also increases as the pH drops, and these aggregates at pH 5.5 can ultimately span several micrometers (116). Consistent with these in vitro results, some of the ceramide-containing LDL particles in human atherosclerotic lesions become large micron-sized aggregates (117). Ceramide efficiently displaces cholesterol from lipid bilayers into the crystalline phase, thus promoting cholesterol crystal nucleation (118, 119). Therefore, the combined actions of SMase and cholesterol esterase on LDL may be important for cholesterol crystallization (87, 94), particularly in acidic environments, where these enzymes are most active.

Oxidative modification of lipoprotein particles leads to formation of lipid peroxides, which further decompose into aldehydes that react with the protein components of the particle. Acidic pH enhances oxidation of LDL by iron, nitric oxide, and myeloperoxidase [reviewed by Leake (71)]. Interestingly, acidic pH induces the aggregation of oxidized LDL (120), but, unexpectedly, LDL oxidized at acidic pH is less cytotoxic than LDL oxidized at neutral pH (121). In contrast to the proteolytic and lipolytic modifications that enhance LDL-proteoglycan binding, oxidation decreases the binding of LDL to proteoglycans due to the neutralization of positively charged lysine residues in apoB-100 (122). However, oxidized LDL particles can bind to human aortic proteoglycans under acidic conditions despite the oxidation-induced decrease in their affinity for proteoglycans (68).

ACIDITY INCREASES LDL UPTAKE BY MACROPHAGES

The appearance of macrophage-derived foam cells in the intima is the hallmark of developing atherosclerotic lesions. Foam cells are formed when macrophages take up modified apoB-containing lipoproteins via various mechanisms, including scavenger receptor-mediated uptake and phagocytosis (124). Also, aggregated LDL bound to the components of the extracellular matrix produced by smooth muscle cells are readily taken up by macrophages (72). Extracellular acidosis enhances the uptake of native and modified LDL particles by macrophages through increases in the levels of cell surface proteoglycans, and of LDL-proteoglycan binding (69, 125). These proteoglycans are most likely heparan-sulfate-rich proteoglycans of the syndecan family (126, 127). Extracellular acidosis may also accelerate foam cell formation by enhancing lipoprotein modifications that promote lipoprotein uptake by macrophages (69, 79, 116, 120). In addition, Howard Kruth has proposed a model of foam cell formation that does not involve LDL modification or macrophage receptors. Thus, when macrophages are incubated with high LDL concentrations comparable to those found the intimal interstitial fluid (128), foam cells are formed as a result of fluid phase pinocytosis of unmodified LDL particles (129). Fluid phase pinocytosis by macrophages has been reported to be increased at acidic pH (19, 20). Thus, most of the proposed mechanisms involved in the uptake of lipoproteins by macrophages and foam cell formation are augmented at acidic extracellular pH (Fig. 3)

ACIDITY DECREASES CHOLESTEROL EFFLUX FROM MACROPHAGE FOAM CELLS AND INDUCES HDL REMODELING

By promoting cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells and by inducing anti-inflammatory effects in macrophages and endothelial cells, HDL particles are also thought to possess strong atheroprotective functions in vivo (130). Although an inverse relation between plasma HDL-cholesterol levels and the rate of atherosclerosis progression has been documented in experimental animal models and in human population studies by aid of imaging of atherosclerotic lesions, recent clinical and genetic studies have failed to confirm the hypothesis of plasma HDL-cholesterol level being per se a determinant of, at least, the final atherothrombotic events in humans (131). Such failures to therapeutically modify atherogenesis in humans have actually led to a conservative skepticism regarding the benefits of HDL-oriented therapies and may have their root cause in our incomplete comprehension of the high complexity of the HDL particles. Indeed, it currently appears that the capability of HDL to prevent atherosclerosis depends on both quantitative and qualitative features of their proteome and lipidome, which ultimately translates itself into functional differences not detected by simply measuring the plasma levels of HDL-cholesterol (132). HDLs are also capable of mediating intercellular communication among different types of cells by a mechanism that involves the transfer of endogenous miRNAs among the body compartments, which may partly explain the high versatility of HDL function (133).

Cholesterol efflux induced by HDL initiates reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), which transfers peripheral cholesterol to the liver for ultimate excretion in the gut (134). Because reduction of the cholesterol pool in arterial macrophages can prevent progression of atherosclerosis or even induce its regression, the particular path of RCT that initiates in the macrophage foam cells (macrophage-RCT) is the most relevant fraction of the total body RCT regarding atherosclerosis (135). In human macrophage foam cells, enhanced cholesterol efflux in response to LXR activation appears to be entirely dependent upon the lipid transporter ABCA1 (136), which promotes cholesterol efflux to lipid-free apoA-I and to the nascent lipid-poor preβ-migrating HDL subpopulation (preβ-HDL) (137). Importantly, cholesterol loading induces a compensatory response in macrophages by upregulating ABCA1 mRNA and protein expression (138).

Various conditions present in the atherosclerotic intima, such as hypoxia (139), inflammation (140), and oxidative stress (141), reduce the ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells. We found that acidic pH also reduces ABCA1-mediated efflux of cholesterol from cultured human macrophage foam cells to apoA-I (142). Because the α-helical content and secondary structure of lipid-free apoA-I are not affected by low pH (109), our finding strongly suggests that acidity impairs the function of ABCA1 rather than the function of apoA-I. Consistent with this speculation, we found that impaired cholesterol efflux from macrophages cultured in medium with a pH value of pH 5.5 or 6.5 is accompanied by progressive reduction in the levels of the ABCA1 protein. In accord with this in vitro finding, the ABCA1 protein level is significantly reduced in whole extracts of human carotid atheromas (143, 144), and, moreover, ABCA1 mRNA was found not to be expressed in the foam cells within the necrotic core of advanced plaques in human atherosclerotic aortas (145), where the intimal fluid most likely has an acidic pH. It is plausible to assume that acidification of the extracellular fluid has additional effects on the activity of ABCA1 in cholesterol efflux; this may be through alterations in the physical properties of ABCA1 and the spatial geometry of the plasma membrane, which is thought to be the main location of ABCA1-mediated apoA-I lipidation (146), or through effects on the electrostatic interaction between ABCA1 and apoA-I (147). Moreover, secretion of apoE, which also stimulates ABCA1-mediated lipid efflux (148), is reduced in macrophages incubated at acidic pH (142). Taken together, these findings support the notion that the cholesterol efflux-mediating activity of ABCA1 in macrophages is reduced by the low extracellular pH found in advanced atherosclerotic lesions (9). Because the interaction of ABCA1 with apoA-I inhibits the expression of inflammatory cytokines in macrophages (149), the lack or low activity of ABCA1 in acidic microenvironments may also exacerbate atherogenesis by leading to enhanced proinflammatory responses in the lesional macrophages.

A small labile pool of apoA-I constantly recycles on and off HDL particles during metabolic remodeling in vivo (150, 151), thereby exchanging apoA-I molecules with the preβ-HDL pool. In this regard, we have shown that an acidic pH in vitro promotes remodeling of the mature HDL particles resulting in formation of preβ-HDL and fusion of the α-migrating HDL (152). Such remodeling was initiated by unfolding of the apolipoproteins on the surface of HDL particles, which was followed by the release of apoA-I from the particles, resulting in the generation of unstable apoA-I-deficient HDL particles that then fuse. However, it is important to note that because lipid-poor apoA-I is extremely sensitive to proteolysis, the proteases known to be secreted by intimal cells will easily render it nonfunctional (153). Indeed, we have found that various acidic cathepsins found in atherosclerotic lesions (81, 79) also effectively degrade apoA-I both in lipid-free and lipid-poor forms with loss of their cholesterol efflux-inducing activity (155). Thus, the production of HDL-derived lipid-free or lipid-poor apoA-I in atherosclerotic plaques may increase as a result of acidification of the intimal fluid, but such generated apoA-I species may also be degraded when acidic proteases gain in function in the low pH microenvironment (Fig. 3).

Based on the above-described fragmentary and apparently two-way processes regarding the effects of acidity on HDL-dependent mechanisms which regulate cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells, the envisioned scenario of such acidity-dependent effects on atherogenesis remains undefined. Thus, while acidity induces remodeling of HDL and ensuing generation of lipid-poor apoA-I species, the lipid-poor species of apoA-I may easily be lost due to extracellular degradation by acidic proteases. Moreover, the expression of ABCA1 in macrophage foam cells at acidic pH is low or absent, and so may compromise cholesterol clearance from foam cells in an arterial segment with an acidic extracellular pH (142). Because the first of the three acidity-induced processes tends to increase, and the two latter ones tend to decrease cholesterol efflux, it is impossible even to predict the net effect of acidity on cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells in an acidic environment in vivo.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

By virtue of its ability to enhance extracellular and intracellular lipid accumulation and to promote proinflammatory processes in macrophages, extracellular acidity has emerged as a novel and potentially crucial element of atherogenesis. Extracellular acidity modifies various proinflammatory functions of macrophages, e.g., by triggering the secretion of potent proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages via activation of the inflammasome pathway (38). Acidity also aggravates extra- and intracellular accumulation of cholesterol in the atherosclerosis-prone regions of the arterial tree. In contrast to the rather straightforward scenario of a proatherogenic role of acidity on intimal accumulation of cholesterol derived from apoB- 100-containing lipoproteins, HDL metabolism in the acidic intimal fluid appears to be complex and unpredictable in its potential outcomes. Such entanglement of HDL metabolism in advanced human atherosclerotic lesions, if present, could be one of the root causes of the failure in designing a clinically relevant HDL-based strategy for anti-atherogenic therapies.

Atherosclerotic lesions contain a heterogeneous mixture of macrophage phenotypes, and some of them may confer more resistance to acidity and hypoxia than others. Recent findings indicate that macrophage proliferation within the plaque plays an important role in the regulation of the size of the macrophage population in atherosclerotic lesions (156). This raises the intriguing possibility that the macrophage population in the plaque evolves over time through selection of acid-resistant macrophages, analogous to the evolution of an acid-resistant cell population in solid tumors (157). There may be an additional level of selection if smooth muscle cells in the atherosclerotic lesion are sensitive to acid-induced cellular toxicity. Indeed, extracellular acidosis inhibits proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells, and also increases their susceptibility to apoptosis (158). Thus, in response to the selection pressure from the microenvironmental pH, the lesion could gradually become enriched with acid-resistant macrophages and depleted of smooth muscle cells, a population imbalance that is found in the rupture-prone subset of atherosclerotic lesions (159). Such a scenario invites us to envision that acidic pH in atherosclerotic lesions not only promotes atherogenesis, but may also contribute to the often lethal atherothrombotic complications of the disease.

After having defined the acidic intimal environment as a perfect soil for atherogenesis, we need to ask: how can it be changed back to neutral? Obviously, we do not know the answer, but are compelled to find it. It is of great interest to note that recent developments in nanoparticle-based therapy of cancer are exploiting the acidic extracellular environment of a tumor for targeted drug delivery to cancer cells (160). Importantly, recent understanding of the similarities between cancer cells and inflammatory cells has unraveled the role of AMP-activated protein kinase as an inhibitor of glycolysis that boosts oxidative phosphorylation (8, 27, 161). The AMP-activated protein kinase is activated by certain drugs and xenobiotics, most notably by the type 2 diabetes drug, metformin, and by the classic anti-inflammatory drug, salicylate (8, 27, 161). This new information, coupled with the developing technologies for acid-dependent drug delivery, might guide us when searching for new therapeutics and anti-atherogenic strategies. The prospects of a successful novel proton-lowering strategy are increased when considering that attenuation of the rate of glycolysis in macrophages may be associated with a phenotypic shift from a proinflammatory into an anti-inflammatory macrophage (8).

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- FcγR

- Fcγ receptor

- HIF-1α

- hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1α IL, interleukin

- LAL

- lysosomal acid lipase

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- NF

- nuclear factor

- PLA2

- phospholipase A2

- RCT

- reverse cholesterol transport

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

This study was supported by grants from the Academy of Finland, Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, the Magnus Ehrnrooth Foundation, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, the Finnish Cultural Foundation, the Oskar Öflund Foundation, the Finnish-Norwegian Medical Foundation, and Biomedicum Helsinki Foundation. Wihuri Research Institute is maintained by the Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.French J. E. 1966. Atherosclerosis in relation to the structure and function of the arterial intima, with special reference to the endothelium. Int. Rev. Exp. Pathol. 5: 253–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz S. M., Majesky M. W., Murry C. E. 1995. The intima: development and monoclonal responses to injury. Atherosclerosis. 118(Suppl): S125–S140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz S. M., deBlois D., O’Brien E. R. 1995. The intima. Soil for atherosclerosis and restenosis. Circ. Res. 77: 445–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eliska O., Eliskova M., Miller A. J. 2006. The absence of lymphatics in normal and atherosclerotic coronary arteries in man: a morphologic study. Lymphology. 39: 76–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres Filho I. P., Leunig M., Yuan F., Intaglietta M., Jain R. K. 1994. Noninvasive measurement of microvascular and interstitial oxygen profiles in a human tumor in SCID mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91: 2081–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsch E., Sluimer J. C., Daemen M. J. 2013. Hypoxia in atherosclerosis and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 24: 393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hultén L. M., Levin M. 2009. The role of hypoxia in atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20: 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palsson-McDermott E. M., O’Neill L. A. 2013. The Warburg effect then and now: from cancer to inflammatory diseases. BioEssays. 35: 965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez J., Hill B. G., Benavides G. A., Dranka B. P., Darley-Usmar V. M. 2010. Role of cellular bioenergetics in smooth muscle cell proliferation induced by platelet-derived growth factor. Biochem. J. 428: 255–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricciardolo F. L., Gaston B., Hunt J. 2004. Acid stress in the pathology of asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 113: 610–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treuhaft P. S., McCarty D. J. 1971. Synovial fluid pH, lactate, oxygen and carbon dioxide partial pressure in various joint diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 14: 475–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings N. A., Nordby G. L. 1966. Measurement of synovial fluid pH in normal and arthritic knees. Arthritis Rheum. 9: 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farr M., Garvey K., Bold A. M., Kendall M. J., Bacon P. A. 1985. Significance of the hydrogen ion concentration in synovial fluid in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 3: 99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lardner A. 2001. The effects of extracellular pH on immune function. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69: 522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okajima F. 2013. Regulation of inflammation by extracellular acidification and proton-sensing GPCRs. Cell. Signal. 25: 2263–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demaurex N., El Chemaly A. 2010. Physiological roles of voltage-gated proton channels in leukocytes. J. Physiol. 588: 4659–4665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Decoursey T. E. 2012. Voltage-gated proton channels. Compr. Physiol. 2: 1355–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grabowski J. E., Vega V. L., Talamini M. A., De Maio A. 2008. Acidification enhances peritoneal macrophage phagocytic activity. J. Surg. Res. 147: 206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong X., Tang X., Du W., Tong J., Yan Y., Zheng F., Fang M., Gong F., Tan Z. 2013. Extracellular acidosis modulates the endocytosis and maturation of macrophages. Cell. Immunol. 281: 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vermeulen M., Giordano M., Trevani A. S., Sedlik C., Gamberale R., Fernandez-Calotti P., Salamone G., Raiden S., Sanjurjo J., Geffner J. R. 2004. Acidosis improves uptake of antigens and MHC class I-restricted presentation by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 172: 3196–3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fonović M., Turk B. 2014. Cysteine cathepsins and extracellular matrix degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1840: 2560–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naghavi M., John R., Naguib S., Siadaty M. S., Grasu R., Kurian K. C., van Winkle W. B., Soller B., Litovsky S., Madjid M., et al. 2002. pH Heterogeneity of human and rabbit atherosclerotic plaques; a new insight into detection of vulnerable plaque. Atherosclerosis. 164: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varghese A. J., Gulyas S., Mohindra J. K. 1976. Hypoxia-dependent reduction of 1-(2-nitro-1-imidazolyl)-3-methoxy-2-propanol by Chinese hamster ovary cells and KHT tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 36: 3761–3765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross M. W., Karbach U., Groebe K., Franko A. J., Mueller-Klieser W. 1995. Calibration of misonidazole labeling by simultaneous measurement of oxygen tension and labeling density in multicellular spheroids. Int. J. Cancer. 61: 567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sluimer J. C., Gasc J. M., van Wanroij J. L., Kisters N., Groeneweg M., Sollewijn Gelpke M. D., Cleutjens J. P., van den Akker L. H., Corvol P., Wouters B. G., et al. 2008. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible transcription factor, and macrophages in human atherosclerotic plaques are correlated with intraplaque angiogenesis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51: 1258–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leppänen O., Björnheden T., Evaldsson M., Boren J., Wiklund O., Levin M. 2006. ATP depletion in macrophages in the core of advanced rabbit atherosclerotic plaques in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 188: 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Neill L. A., Hardie D. G. 2013. Metabolism of inflammation limited by AMPK and pseudo-starvation. Nature. 493: 346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warburg O. 1956. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 124: 269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.. Deleted in proof. [Google Scholar]

- 30.. Deleted in proof. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodríguez-Prados J. C., Traves P. G., Cuenca J., Rico D., Aragones J., Martin-Sanz P., Cascante M., Bosca L. 2010. Substrate fate in activated macrophages: a comparison between innate, classic, and alternative activation. J. Immunol. 185: 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cramer T., Yamanishi Y., Clausen B. E., Forster I., Pawlinski R., Mackman N., Haase V. H., Jaenisch R., Corr M., Nizet V., et al. 2003. HIF-1alpha is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell. 112: 645–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roiniotis J., Dinh H., Masendycz P., Turner A., Elsegood C. L., Scholz G. M., Hamilton J. A. 2009. Hypoxia prolongs monocyte/macrophage survival and enhanced glycolysis is associated with their maturation under aerobic conditions. J. Immunol. 182: 7974–7981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krawczyk C. M., Holowka T., Sun J., Blagih J., Amiel E., DeBerardinis R. J., Cross J. R., Jung E., Thompson C. B., Jones R. G., et al. 2010. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood. 115: 4742–4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lukashev D., Caldwell C., Ohta A., Chen P., Sitkovsky M. 2001. Differential regulation of two alternatively spliced isoforms of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha in activated T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 48754–48763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West A. P., Brodsky I. E., Rahner C., Woo D. K., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Walsh M. C., Choi Y., Shadel G. S., Ghosh S. 2011. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 472: 476–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menkin V. 1956. Biology of inflammation; chemical mediators and cellular injury. Science. 123: 527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajamäki K., Nordström T., Nurmi K., Åkerman K. E., Kovanen P. T., Öörni K., Eklund K. K. 2013. Extracellular acidosis is a novel danger signal alerting innate immunity via the NLRP3 inflammasome. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 13410–13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.López D. H., Trevani A. S., Salamone G., Andonegui G., Raiden S., Giordano M., Geffner J. R. 1999. Acidic pH increases the avidity of FcgammaR for immune complexes. Immunology. 98: 450–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park S. Y., Bae D. J., Kim M. J., Piao M. L., Kim I. S. 2012. Extracellular low pH modulates phosphatidylserine-dependent phagocytosis in macrophages by increasing stabilin-1 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 11261–11271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swallow C. J., Grinstein S., Sudsbury R. A., Rotstein O. D. 1990. Modulation of the macrophage respiratory burst by an acidic environment: the critical role of cytoplasmic pH regulation by proton extrusion pumps. Surgery. 108: 363–368; discussion 368–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bidani A., Reisner B. S., Haque A. K., Wen J., Helmer R. E., Tuazon D. M., Heming T. A. 2000. Bactericidal activity of alveolar macrophages is suppressed by V-ATPase inhibition. Lung. 178: 91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. 1984. Oxygen toxicity, oxygen radicals, transition metals and disease. Biochem. J. 219: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morgan J., Leake D. S. 1993. Acidic pH increases the oxidation of LDL by macrophages. FEBS Lett. 333: 275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bellocq A., Suberville S., Philippe C., Bertrand F., Perez J., Fouqueray B., Cherqui G., Baud L. 1998. Low environmental pH is responsible for the induction of nitric-oxide synthase in macrophages. Evidence for involvement of nuclear factor-kappaB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 5086–5092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grabowski J., Vazquez D. E., Costantini T., Cauvi D. M., Charles W., Bickler S., Talamini M. A., Vega V. L., Coimbra R., De Maio A. 2012. Tumor necrosis factor expression is ameliorated after exposure to an acidic environment. J. Surg. Res. 173: 127–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heming T. A., Dave S. K., Tuazon D. M., Chopra A. K., Peterson J. W., Bidani A. 2001. Effects of extracellular pH on tumour necrosis factor-alpha production by resident alveolar macrophages. Clin. Sci. (Lond.). 101: 267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mogi C., Tobo M., Tomura H., Murata N., He X. D., Sato K., Kimura T., Ishizuka T., Sasaki T., Sato T., et al. 2009. Involvement of proton-sensing TDAG8 in extracellular acidification-induced inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production in peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 182: 3243–3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerry A. B., Leake D. S. 2014. Effect of low extracellular pH on NF-kappaB activation in macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 233: 537–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jancic C. C., Cabrini M., Gabelloni M. L., Rodriguez Rodrigues C., Salamone G., Trevani A. S., Geffner J. 2012. Low extracellular pH stimulates the production of IL-1beta by human monocytes. Cytokine. 57: 258–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Netea M. G., Nold-Petry C. A., Nold M. F., Joosten L. A., Opitz B., van der Meer J. H., van de Veerdonk F. L., Ferwerda G., Heinhuis B., Devesa I., et al. 2009. Differential requirement for the activation of the inflammasome for processing and release of IL-1beta in monocytes and macrophages. Blood. 113: 2324–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duewell P., Kono H., Rayner K. J., Sirois C. M., Vladimer G., Bauernfeind F. G., Abela G. S., Franchi L., Nunez G., Schnurr M., et al. 2010. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 464: 1357–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajamäki K., Lappalainen J., Öörni K., Valimaki E., Matikainen S., Kovanen P. T., Eklund K. K. 2010. Cholesterol crystals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages: a novel link between cholesterol metabolism and inflammation. PLoS ONE. 5: e11765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park S. Y., Kim I. S. 2013. Identification of macrophage genes responsive to extracellular acidification. Inflamm. Res. 62: 399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lopes-Virella M. F., Virella G. 2013. Pathogenic role of modified LDL antibodies and immune complexes in atherosclerosis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 20: 743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dinarello C. A. 2009. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27: 519–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Camejo G., Hurt-Camejo E., Wiklund O., Bondjers G. 1998. Association of apo B lipoproteins with arterial proteoglycans: pathological significance and molecular basis. Atherosclerosis. 139: 205–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skålén K., Gustafsson M., Rydberg E. K., Hulten L. M., Wiklund O., Innerarity T. L., Boren J. 2002. Subendothelial retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in early atherosclerosis. Nature. 417: 750–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams K. J., Tabas I. 1995. The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15: 551–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tabas I., Williams K. J., Boren J. 2007. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation. 116: 1832–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vijayagopal P., Figueroa J. E., Fontenot J. D., Glancy D. L. 1996. Isolation and characterization of a proteoglycan variant from human aorta exhibiting a marked affinity for low density lipoprotein and demonstration of its enhanced expression in atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis. 127: 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Camejo G., Fager G., Rosengren B., Hurt-Camejo E., Bondjers G. 1993. Binding of low density lipoproteins by proteoglycans synthesized by proliferating and quiescent human arterial smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 14131–14137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anber V., Millar J. S., McConnell M., Shepherd J., Packard C. J. 1997. Interaction of very-low-density, intermediate-density, and low-density lipoproteins with human arterial wall proteoglycans. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 17: 2507–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flood C., Gustafsson M., Richardson P. E., Harvey S. C., Segrest J. P., Boren J. 2002. Identification of the proteoglycan binding site in apolipoprotein B48. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 32228–32233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Proctor S. D., Vine D. F., Mamo J. C. 2002. Arterial retention of apolipoprotein B(48)- and B(100)-containing lipoproteins in atherogenesis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 13: 461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rapp J. H., Lespine A., Hamilton R. L., Colyvas N., Chaumeton A. H., Tweedie-Hardman J., Kotite L., Kunitake S. T., Havel R. J., Kane J. P. 1994. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins isolated by selected-affinity anti-apolipoprotein B immunosorption from human atherosclerotic plaque. Arterioscler. Thromb. 14: 1767–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nordestgaard B. G., Tybjaerg-Hansen A. 2011. Genetic determinants of LDL, lipoprotein(a), triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and HDL: concordance and discordance with cardiovascular disease risk. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 22: 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sneck M., Kovanen P. T., Öörni K. 2005. Decrease in pH strongly enhances binding of native, proteolyzed, lipolyzed, and oxidized low density lipoprotein particles to human aortic proteoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 37449–37454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lähdesmäki K., Öörni K., Alanne-Kinnunen M., Jauhiainen M., Hurt-Camejo E., Kovanen P. T. 2012. Acidity and lipolysis by group V secreted phospholipase A(2) strongly increase the binding of apoB-100-containing lipoproteins to human aortic proteoglycans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1821: 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chakrabarti B., Park J. W. 1980. Glycosaminoglycans: structure and interaction. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 8: 225–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leake D. S. 1997. Does an acidic pH explain why low density lipoprotein is oxidised in atherosclerotic lesions? Atherosclerosis. 129: 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tabas I., Li Y., Brocia R. W., Xu S. W., Swenson T. L., Williams K. J. 1993. Lipoprotein lipase and sphingomyelinase synergistically enhance the association of atherogenic lipoproteins with smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix. A possible mechanism for low density lipoprotein and lipoprotein(a) retention and macrophage foam cell formation. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 20419–20432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pentikäinen M. O., Öörni K., Kovanen P. T. 2000. Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) strongly links native and oxidized low density lipoprotein particles to decorin-coated collagen. Roles for both dimeric and monomeric forms of LPL. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 5694–5701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gustafsson M., Levin M., Skalen K., Perman J., Friden V., Jirholt P., Olofsson S. O., Fazio S., Linton M. F., Semenkovich C. F., et al. 2007. Retention of low-density lipoprotein in atherosclerotic lesions of the mouse: evidence for a role of lipoprotein lipase. Circ. Res. 101: 777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bengtsson-Olivecrona G., Olivecrona T. 1985. Binding of active and inactive forms of lipoprotein lipase to heparin. Effects of pH. Biochem. J. 226: 409–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bengtsson G., Olivecrona T. 1983. The effects of pH and salt on the lipid binding and enzyme activity of lipoprotein lipase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 751: 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Öörni K., Pentikäinen M. O., Ala-Korpela M., Kovanen P. T. 2000. Aggregation, fusion, and vesicle formation of modified low density lipoprotein particles: molecular mechanisms and effects on matrix interactions. J. Lipid Res. 41: 1703–1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oörni K., Kovanen P. T. 2006. Enhanced extracellular lipid accumulation in acidic environments. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 17: 534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oörni K., Sneck M., Bromme D., Pentikäinen M. O., Lindstedt K. A., Mäyranpää M., Aitio H., Kovanen P. T. 2004. Cysteine protease cathepsin F is expressed in human atherosclerotic lesions, is secreted by cultured macrophages, and modifies low density lipoprotein particles in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 34776–34784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leake D. S., Rankin S. M., Collard J. 1990. Macrophage proteases can modify low density lipoproteins to increase their uptake by macrophages. FEBS Lett. 269: 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sukhova G. K., Shi G. P., Simon D. I., Chapman H. A., Libby P. 1998. Expression of the elastolytic cathepsins S and K in human atheroma and regulation of their production in smooth muscle cells. J. Clin. Invest. 102: 576–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Plihtari R., Hurt-Camejo E., Öörni K., Kovanen P. T. 2010. Proteolysis sensitizes LDL particles to phospholipolysis by secretory phospholipase A2 group V and secretory sphingomyelinase. J. Lipid Res. 51: 1801–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hakala J. K., Oksjoki R., Laine P., Du H., Grabowski G. A., Kovanen P. T., Pentikainen M. O. 2003. Lysosomal enzymes are released from cultured human macrophages, hydrolyze LDL in vitro, and are present extracellularly in human atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23: 1430–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Punturieri A., Filippov S., Allen E., Caras I., Murray R., Reddy V., Weiss S. J. 2000. Regulation of elastinolytic cysteine proteinase activity in normal and cathepsin K-deficient human macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 192: 789–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haka A. S., Grosheva I., Chiang E., Buxbaum A. R., Baird B. A., Pierini L. M., Maxfield F. R. 2009. Macrophages create an acidic extracellular hydrolytic compartment to digest aggregated lipoproteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20: 4932–4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Haka A. S., Grosheva I., Singh R. K., Maxfield F. R. 2013. Plasmin promotes foam cell formation by increasing macrophage catabolism of aggregated low-density lipoprotein. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33: 1768–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Small D. M. 1988. George Lyman Duff memorial lecture. Progression and regression of atherosclerotic lesions. Insights from lipid physical biochemistry. Arteriosclerosis. 8: 103–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Katz S. S., Shipley G. G., Small D. M. 1976. Physical chemistry of the lipids of human atherosclerotic lesions. Demonstration of a lesion intermediate between fatty streaks and advanced plaques. J. Clin. Invest. 58: 200–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Guyton J. R., Klemp K. F. 1993. Transitional features in human atherosclerosis. Intimal thickening, cholesterol clefts, and cell loss in human aortic fatty streaks. Am. J. Pathol. 143: 1444–1457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tangirala R. K., Jerome W. G., Jones N. L., Small D. M., Johnson W. J., Glick J. M., Mahlberg F. H., Rothblat G. H. 1994. Formation of cholesterol monohydrate crystals in macrophage-derived foam cells. J. Lipid Res. 35: 93–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kellner-Weibel G., Jerome W. G., Small D. M., Warner G. J., Stoltenborg J. K., Kearney M. A., Corjay M. H., Phillips M. C., Rothblat G. H. 1998. Effects of intracellular free cholesterol accumulation on macrophage viability: a model for foam cell death. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 18: 423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kellner-Weibel G., Yancey P. G., Jerome W. G., Walser T., Mason R. P., Phillips M. C., Rothblat G. H. 1999. Crystallization of free cholesterol in model macrophage foam cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19: 1891–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sheedy F. J., Grebe A., Rayner K. J., Kalantari P., Ramkhelawon B., Carpenter S. B., Becker C. E., Ediriweera H. N., Mullick A. E., Golenbock D. T., et al. 2013. CD36 coordinates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by facilitating intracellular nucleation of soluble ligands into particulate ligands in sterile inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 14: 812–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guarino A. J., Tulenko T. N., Wrenn S. P. 2004. Cholesterol crystal nucleation from enzymatically modified low-density lipoproteins: combined effect of sphingomyelinase and cholesterol esterase. Biochemistry. 43: 1685–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jandacek R. J., Webb M. R., Mattson F. H. 1977. Effect of an aqueous phase on the solubility of cholesterol in an oil phase. J. Lipid Res. 18: 203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vedre A., Pathak D. R., Crimp M., Lum C., Koochesfahani M., Abela G. S. 2009. Physical factors that trigger cholesterol crystallization leading to plaque rupture. Atherosclerosis. 203: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Uskoković V., Matijevic E. 2007. Uniform particles of pure and silica-coated cholesterol. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 315: 500–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Oörni K., Kovanen P. T. 2009. Lipoprotein modification by secretory phospholipase A(2) enzymes contributes to the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20: 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Eguchi K., Manabe I. 2014. Toll-like receptor, lipotoxicity and chronic inflammation: The pathological link between obesity and cardiometabolic disease. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 21: 629–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Benítez S., Camacho M., Arcelus R., Vila L., Bancells C., Ordonez-Llanos J., Sanchez-Quesada J. L. 2004. Increased lysophosphatidylcholine and non-esterified fatty acid content in LDL induces chemokine release in endothelial cells. Relationship with electronegative LDL. Atherosclerosis. 177: 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huang Y. H., Schafer-Elinder L., Wu R., Claesson H. E., Frostegard J. 1999. Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) induces proinflammatory cytokines by a platelet-activating factor (PAF) receptor-dependent mechanism. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 116: 326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Håversen L., Danielsson K. N., Fogelstrand L., Wiklund O. 2009. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines by long-chain saturated fatty acids in human macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 202: 382–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Boyanovsky B. B., Webb N. R. 2009. Biology of secretory phospholipase A2. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 23: 61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jönsson-Rylander A. C., Lundin S., Rosengren B., Pettersson C., Hurt-Camejo E. 2008. Role of secretory phospholipases in atherogenesis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 10: 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rosengren B., Peilot H., Umaerus M., Jonsson-Rylander A. C., Mattsson-Hulten L., Hallberg C., Cronet P., Rodriguez-Lee M., Hurt-Camejo E. 2006. Secretory phospholipase A2 group V: lesion distribution, activation by arterial proteoglycans, and induction in aorta by a Western diet. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26: 1579–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bostrom M. A., Boyanovsky B. B., Jordan C. T., Wadsworth M. P., Taatjes D. J., de Beer F. C., Webb N. R. 2007. Group v secretory phospholipase A2 promotes atherosclerosis: evidence from genetically altered mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 600–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lambeau G., Gelb M. H. 2008. Biochemistry and physiology of mammalian secreted phospholipases A2. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77: 495–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Winget J. M., Pan Y. H., Bahnson B. J. 2006. The interfacial binding surface of phospholipase A 2 s. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1761: 1260–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhou Y., Raphael R. M. 2007. Solution pH alters mechanical and electrical properties of phosphatidylcholine membranes: relation between interfacial electrostatics, intramembrane potential, and bending elasticity. Biophys. J. 92: 2451–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lähdesmäki K., Ollila O. H., Koivuniemi A., Kovanen P. T., Hyvönen M. T. 2010. Membrane simulations mimicking acidic pH reveal increased thickness and negative curvature in a bilayer consisting of lysophosphatidylcholines and free fatty acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1798: 938–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lähdesmäki K., Plihtari R., Soininen P., Hurt-Camejo E., Ala-Korpela M., Öörni K., Kovanen P. T. 2009. Phospholipase A(2)-modified LDL particles retain the generated hydrolytic products and are more atherogenic at acidic pH. Atherosclerosis. 207: 352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Spector A. A. 1975. Fatty acid binding to plasma albumin. J. Lipid Res. 16: 165–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hamilton J. A. 2002. How fatty acids bind to proteins: the inside story from protein structures. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 67: 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schissel S. L., Jiang X., Tweedie-Hardman J., Jeong T., Camejo E. H., Najib J., Rapp J. H., Williams K. J., Tabas I. 1998. Secretory sphingomyelinase, a product of the acid sphingomyelinase gene, can hydrolyze atherogenic lipoproteins at neutral pH. Implications for atherosclerotic lesion development. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 2738–2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schissel S. L., Schuchman E. H., Williams K. J., Tabas I. 1996. Zn2+-stimulated sphingomyelinase is secreted by many cell types and is a product of the acid sphingomyelinase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 18431–18436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sneck M., Nguyen S. D., Pihlajamaa T., Yohannes G., Riekkola M. L., Milne R., Kovanen P. T., Öörni K. 2012. Conformational changes of apoB-100 in SMase-modified LDL mediate formation of large aggregates at acidic pH. J. Lipid Res. 53: 1832–1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schissel S. L., Tweedie-Hardman J., Rapp J. H., Graham G., Williams K. J., Tabas I. 1996. Rabbit aorta and human atherosclerotic lesions hydrolyze the sphingomyelin of retained low-density lipoprotein. Proposed role for arterial-wall sphingomyelinase in subendothelial retention and aggregation of atherogenic lipoproteins. J. Clin. Invest. 98: 1455–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ali M. R., Cheng K. H., Huang J. 2006. Ceramide drives cholesterol out of the ordered lipid bilayer phase into the crystal phase in 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine/cholesterol/ceramide ternary mixtures. Biochemistry. 45: 12629–12638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ramstedt B., Slotte J. P. 2006. Sphingolipids and the formation of sterol-enriched ordered membrane domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1758: 1945–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Satchell L., Leake D. S. 2012. Oxidation of low-density lipoprotein by iron at lysosomal pH: implications for atherosclerosis. Biochemistry. 51: 3767–3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pfanzagl B. 2006. LDL oxidized with iron in the presence of homocysteine/cystine at acidic pH has low cytotoxicity despite high lipid peroxidation. Atherosclerosis. 187: 292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Oörni K., Pentikäinen M. O., Annila A., Kovanen P. T. 1997. Oxidation of low density lipoprotein particles decreases their ability to bind to human aortic proteoglycans. Dependence on oxidative modification of the lysine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 21303–21311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.. Deleted in proof. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Witztum J. L. 2005. You are right too! J. Clin. Invest. 115: 2072–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Plihtari R., Kovanen P. T., Öörni K. 2011. Acidity increases the uptake of native LDL by human monocyte-derived macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 217: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fuki I. V., Kuhn K. M., Lomazov I. R., Rothman V. L., Tuszynski G. P., Iozzo R. V., Swenson T. L., Fisher E. A., Williams K. J. 1997. The syndecan family of proteoglycans. Novel receptors mediating internalization of atherogenic lipoproteins in vitro. J. Clin. Invest. 100: 1611–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Boyanovsky B. B., Shridas P., Simons M., van der Westhuyzen D. R., Webb N. R. 2009. Syndecan-4 mediates macrophage uptake of group V secretory phospholipase A2-modified LDL. J. Lipid Res. 50: 641–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Smith E. B. 1990. Transport, interactions and retention of plasma proteins in the intima: the barrier function of the internal elastic lamina. Eur. Heart J. 11(Suppl E): 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhao B., Li Y., Buono C., Waldo S. W., Jones N. L., Mori M., Kruth H. S. 2006. Constitutive receptor-independent low density lipoprotein uptake and cholesterol accumulation by macrophages differentiated from human monocytes with macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF). J. Biol. Chem. 281: 15757–15762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Navab M., Reddy S. T., Van Lenten B. J., Fogelman A. M. 2011. HDL and cardiovascular disease: atherogenic and atheroprotective mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 8: 222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rubenfire M., Brook R. D. 2013. HDL cholesterol and cardiovascular outcomes: what is the evidence? Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 15: 349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Feig J. E., Hewing B., Smith J. D., Hazen S. L., Fisher E. A. 2014. High-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis regression: evidence from preclinical and clinical studies. Circ. Res. 114: 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Aryal B., Rotllan N., Fernandez-Hernando C. 2014. Noncoding RNAs and atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 16: 407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lee-Rueckert M., Blanco-Vaca F., Kovanen P. T., Escola-Gil J. C. 2013. The role of the gut in reverse cholesterol transport–focus on the enterocyte. Prog. Lipid Res. 52: 317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cuchel M., Rader D. J. 2006. Macrophage reverse cholesterol transport: key to the regression of atherosclerosis? Circulation. 113: 2548–2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Larrede S., Quinn C. M., Jessup W., Frisdal E., Olivier M., Hsieh V., Kim M. J., Van Eck M., Couvert P., Carrie A., et al. 2009. Stimulation of cholesterol efflux by LXR agonists in cholesterol-loaded human macrophages is ABCA1-dependent but ABCG1-independent. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29: 1930–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Asztalos B. F., Tani M., Schaefer E. J. 2011. Metabolic and functional relevance of HDL subspecies. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 22: 176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Langmann T., Klucken J., Reil M., Liebisch G., Luciani M. F., Chimini G., Kaminski W. E., Schmitz G. 1999. Molecular cloning of the human ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (hABC1): evidence for sterol-dependent regulation in macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 257: 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Parathath S., Yang Y., Mick S., Fisher E. A. 2013. Hypoxia in murine atherosclerotic plaques and its adverse effects on macrophages. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 23: 80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Maitra U., Li L. 2013. Molecular mechanisms responsible for the reduced expression of cholesterol transporters from macrophages by low-dose endotoxin. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33: 24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Marcil V., Delvin E., Sane A. T., Tremblay A., Levy E. 2006. Oxidative stress influences cholesterol efflux in THP-1 macrophages: role of ATP-binding cassette A1 and nuclear factors. Cardiovasc. Res. 72: 473–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Lee-Rueckert M., Lappalainen J., Leinonen H., Pihlajamaa T., Jauhiainen M., Kovanen P. T. 2010. Acidic extracellular environments strongly impair ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux from human macrophage foam cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30: 1766–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Albrecht C., Soumian S., Amey J. S., Sardini A., Higgins C. F., Davies A. H., Gibbs R. G. 2004. ABCA1 expression in carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Stroke. 35: 2801–2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Forcheron F., Legedz L., Chinetti G., Feugier P., Letexier D., Bricca G., Beylot M. 2005. Genes of cholesterol metabolism in human atheroma: overexpression of perilipin and genes promoting cholesterol storage and repression of ABCA1 expression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25: 1711–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Lawn R. M., Wade D. P., Couse T. L., Wilcox J. N. 2001. Localization of human ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (ABC1) in normal and atherosclerotic tissues. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21: 378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Denis M., Landry Y. D., Zha X. 2008. ATP-binding cassette A1-mediated lipidation of apolipoprotein A-I occurs at the plasma membrane and not in the endocytic compartments. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 16178–16186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]