Today’s father is not your father’s father. There are 70.1 million fathers in the United States,1 with 24.7 million part of married couples with children aged <18 years. Although 40% of children are born to unmarried couples, father involvement in all families has never been higher. From 1965 to 2011, fathers have more than doubled their involvement, both in time spent with their children in child care and time spent doing housework.2 Fathers’ expectations for their involvement are also high, with nearly all fathers attending the birth of their child and having positive expectations for their future involvement with their child, regardless of marital status.3,4

The past decade has expanded our understanding of mental health among fathers. We know paternal depression seems to affect 5% to 10% of fathers in the postpartum period,5 that there is an increase in paternal depressive symptom scores in the first 5 years after the birth,6 and 21% of fathers will have experienced depression by the time their child is 12 years of age.7 We know children with depressed fathers are more likely to have adverse emotional and behavioral outcomes8 and less likely to benefit from positive paternal parenting practices such as reading.9 What we still have to learn are the mechanisms through which fathers affect child outcomes.

In this issue of Pediatrics, Gutierrez-Galve et al10 provide insight into 1 of the mechanisms through which fathers contribute to family and child outcomes. Using the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, the authors examined the transmission of risk associated with parents’ depression symptom scores at 8 weeks of their infant’s life and subsequently the child’s total problems scale (emotional problems, hyperactivity, and conduct problems) at 3.5 and 7 years. The major finding in their analysis was that fathers affect child outcomes by way of mothers; that is, depressed fathers influence 2 key family areas—mother’s depression and couple conflict—which in turn adversely affect the child’s emotional and behavioral outcomes.

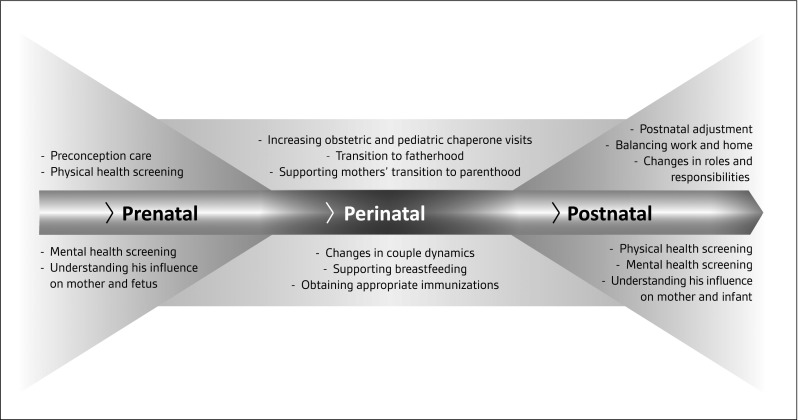

This finding means one thing for clinicians who care for families and children: we need to identify at-risk fathers early and to intervene. Doing so creates true synergy wherein helping fathers then helps mothers in terms of maternal depression and couples conflict, which ultimately benefits the child. Conceptualizing the transition to fatherhood as a timeline beginning prenatally, passing through the perinatal period, and continuing through the postnatal period clarifies potential domains and opportunities for preventive health care and support for fathers and families (Fig 1). In the prenatal period, young men are among the least likely group to be involved in the health care system yet they play a central role in creating the social and environmental milieu for their partner and the fetus. Further along the time line in the perinatal period, fathers increase their exposure to the health care system as obstetric and pediatric chaperones.11,12 Opportunities abound to understand the transition to parenthood for both parents and to identify ways to support key areas such as breastfeeding and mothers’ mental health. The postnatal period finds fathers once again in their communities with their new family but with potentially poorer health care access for themselves and fewer resources, yet a need to maintain their physical and mental health for the psychological, emotional, and economic well-being of their family.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptualization fathers' involvement in health from preconception through to the postnatal period.

We would be remiss to think that as long as we reach fathers by the perinatal period, all will be well. As Gutierrez-Galve et al10 show, it is fathers’ influences on mothers that affect the child, and this influence is as likely to occur in the months before birth as after the birth. Focusing earlier on the time line (ie, engaging with fathers and couples sooner) affords the best opportunities to prevent negative outcomes. Such an approach falls squarely in the realm of preconception care, an idea supported for mothers and fathers by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention13 and for which clinical content has been described.14

The challenge now is in designing effective interventions for fathers. A recent systematic review of parenting interventions for father engagement concluded that fundamental changes in the design and delivery of these interventions is required that acknowledges fathers’ coparenting role.15 Possible timing and content of interventions are noted on the timeline (Fig 1). Specific attention needs to be paid to vulnerable subpopulations (eg, nonresident fathers, adolescent fathers). Thankfully, access to health care, an often-mentioned barrier, seems to be improving, with early analysis of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act showing declines in uninsured rates among the key child-rearing ages of 18 to 34 years and among minorities.16 These findings suggest that the health care system may indeed be a promising locale for interventions.

Fathers of the future, like today’s fathers, are likely to continue to be connected and involved with their partners and children in dynamic and influential ways. Determining how to best support fathers in need of help is a necessary next step for improving child outcomes.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The author has indicated he has no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (K23HD060664) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute For Child Health and Development. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The author has indicated he has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found on page e339, online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2014-2411.

References

- 1.Father's Day. June 15, 2014 [press release]. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau News; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker K, Wang W. Modern Parenthood: Roles of Moms and Dads Converge as They Balance Work and Family. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlson M, McLanahan S, England P. Union formation in fragile families. Demography. 2004;41(2):237–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garfield CF, Chung PJ. A qualitative study of early differences in fathers' expectations of their child care responsibilities. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(4):215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA. Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):659–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garfield CF, Duncan G, Rutsohn J, et al. A longitudinal study of paternal mental health during transition to fatherhood as young adults. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):836–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davé S, Petersen I, Sherr L, Nazareth I. Incidence of maternal and paternal depression in primary care: a cohort study using a primary care database. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(11):1038–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramchandani P, Stein A, Evans J, O’Connor TG; ALSPAC study team. Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: a prospective population study. Lancet. 2005;365(9478):2201–2205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis RN, Davis MM, Freed GL, Clark SJ. Fathers’ depression related to positive and negative parenting behaviors with 1-year-old children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):612–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutierrez-Galve L, Stein A, Hanington L, Heron J, Ramchandani P. Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: mediators and moderators. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/135/2/e339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garfield CF, Isacco A. Fathers and the well-child visit. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/117/4/e637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore T, Kotelchuck M. Predictors of Urban fathers’ involvement in their child’s health care. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 pt 1):574–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, et al. Recommendations to Improve Preconception Health and Health Care—United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frey KA, Navarro SM, Kotelchuck M, Lu MC. The clinical content of preconception care: preconception care for men. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6 suppl 2):S389–S395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panter-Brick C, Burgess A, Eggerman M, McAllister F, Pruett K, Leckman JF. Practitioner Review: engaging fathers—recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(11):1187–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sommers BD, Musco T, Finegold K, Gunja MZ, Burke A, McDowell AM. Health reform and changes in health insurance coverage in 2014. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):867–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]